Abstract

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB) is a potentially lethal complication in cirrhosis. In this prospective international multi-center study, the performance of CAGIB score for predicting the risk of in-hospital death in 2467 cirrhotic patients with AGIB was validated. Machine learning (ML) models were established based on CAGIB components, and their area under curves (AUCs) were calculated and compared. Gray zone approach was employed to further stratify the risk of death. In training cohort, the AUC of CAGIB score was 0.789. Among the ML models, the least square support vector machine regression (LS-SVMR) model had the best predictive performance (AUC = 0.986). Patients were further divided into low- (LS-SVMR score <0.084), moderate- (LS-SVMR score 0.084–0.160), and high-risk (LS-SVMR score >0.160) groups with in-hospital mortality of 0.38%, 2.22%, and 64.37%, respectively. Statistical results were retained in validation cohort. LS-SVMR model has an excellent predictive performance for in-hospital death in cirrhotic patients with AGIB (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT04662918).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB) is a life-threatening medical emergency with a high morbidity1. Currently, the management of AGIB in liver cirrhosis mainly includes resuscitation, blood transfusion, vasoactive drugs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), endoscopy, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and surgery2,3. In spite of recent advances in the treatment, the in-hospital and 6-week mortality of AGIB is approximately 0–10% and 15–20% in patients with liver cirrhosis4,5, and even 30% in those with Child-Pugh class C6. In this setting, accurate assessment of the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with AGIB in a timely fashion should be critical to inform their family members about disease severity and risk of death and further guide the treatment selection.

Based on the data of 1682 cirrhotic patients with AGIB from 13 Chinese medical centers, CAGIB score was developed and internally validated to predict the risk of in-hospital death in patients with liver cirrhosis and AGIB7. It includes two clinical variables (i.e., diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC]) and four laboratory variables (i.e., total bilirubin [TBIL], albumin [ALB], serum creatinine [Scr], and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), all of which are readily available in everyday clinical practice. Recently, a retrospective cohort study, including 379 patients with liver cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding from a single center, has validated the superiority of CAGIB in assessing the in-hospital outcome8. Another retrospective cohort study, which included 142 patients with liver cirrhosis and variceal bleeding from a single center, has also suggested the predictive performance of CAGIB for the risk of rebleeding within 180 days9. However, its advantage has not been supported by other studies10. Thus, it should be necessary to validate the predictive performance of CAGIB score in such a group of population and further improve its accuracy using novel approaches.

Machine learning (ML) can translate complex relationships into clear and logistic reasoning without any restriction from data distribution and has been increasingly employed in the field of clinical practice and academic research in recent years11,12,13. ML methods have been widely employed for predicting the progression of various liver diseases, such as viral hepatitis, fatty liver disease, and cirrhosis, and ML-based models have also shown excellent performance14,15,16,17.

This prospective international multicenter study aims to validate the performance of CAGIB score for the prediction of in-hospital death in patients with liver cirrhosis and AGIB and further improve its predictive performance by using ML in such patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 2467 patients with liver cirrhosis and AGIB were included (Table 1). The most common etiology of liver cirrhosis was hepatitis B virus infection (n = 1255), followed by alcohol abuse (n = 365), and hepatitis C virus infection (n = 229). The mean Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, and MELD 3.0 scores were 7.76, 14.09, and 14.39, respectively. Among them, 1602 patients presented with hematemesis at their admissions, 1492 were diagnosed with variceal bleeding on endoscopy, 1414 underwent endoscopic treatment, 1498 received blood transfusion, and 139 died during hospitalizations. Causes of death included hemorrhagic shock (n = 71), multiple organ failure (n = 45), infection (n = 9), HCC (n = 7), HE (n = 6), and volume overload (n = 1).

One thousand two hundred and thirty-three and 1234 patients were assigned to the training and validation cohorts, respectively. The training cohort had significantly higher proportions of male (70.00% vs. 65.70%, P = 0.023) and ICU admission (15.70% vs. 12.60%, P = 0.028), TBIL level (44.59 ± 71.18 vs. 40.74 ± 61.90, P = 0.012), and MELD-Na score (14.29 ± 5.95 vs. 13.89 ± 5.83, P = 0.034) than the validation cohort. However, other variables were not significantly different between the two cohorts (Table 1).

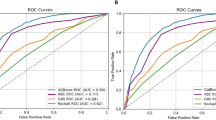

Validation of CAGIB score in training cohort

In the overall analysis of 1233 patients from the training cohort, the performance of CAGIB score (AUC = 0.789) for predicting in-hospital death was statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh (AUC = 0.804, P = 0.569), MELD-Na (AUC = 0.817, P = 0.234), MELD 3.0 (AUC = 0.822, P = 0.132), D’Amico (AUC = 0.797, P = 0.774), and Augustin (AUC = 0.814, P = 0.170) scores (Fig. 1a).

a All patients; b Patients with variceal bleeding; c Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment; d Patients who received pharmacological treatment alone without endoscopic treatment. The performance of CAGIB score for predicting in-hospital death was statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, D’Amico, and Augustin scores both in overall and subgroup analyses.

In the subgroup analysis of 736 patients with variceal bleeding, 708 patients who underwent endoscopic treatment, and 463 patients who received pharmacological treatment alone (Supplementary Table 1), the performance of CAGIB score for predicting in-hospital death was also statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, D’Amico, and Augustin scores (P > 0.05 for all tests) (Fig. 1b–d).

Validation of CAGIB score in validation cohort

In the overall analysis of 1234 patients from the validation cohort, the performance of CAGIB score (AUC = 0.801) for predicting in-hospital death was statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh (AUC = 0.809, P = 0.801), MELD-Na (AUC = 0.803, P = 0.960), MELD 3.0 (AUC = 0.813, P = 0.667), D’Amico (AUC = 0.851, P = 0.05), and Augustin (AUC = 0.830, P = 0.213) scores (Fig. 2a).

a All patients; b Patients with variceal bleeding; c Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment; d Patients who received pharmacological treatment alone without endoscopic treatment. The performance of CAGIB score for predicting in-hospital death was statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, D’Amico, and Augustin scores both in overall and subgroup analyses.

In the subgroup analysis of 756 patients with variceal bleeding, 706 patients who underwent endoscopic treatment, and 456 patients who received pharmacological treatment alone (Supplementary Table 2), the performance of CAGIB score for predicting in-hospital death was statistically similar to that of Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, D’Amico, and Augustin scores (P > 0.05 for all tests) (Fig. 2b–d).

ML models based on the components of the CAGIB score in training cohort

LS-SVMR model (AUC = 0.986) had significantly higher AUCs than ANN (AUC = 0.894, P < 0.001), KNN (AUC = 0.895, P < 0.001), and decision tree (AUC = 0.632, P < 0.001) models (Fig. 3a), and statistically similar AUC to XGBoost model (AUC = 0.984, P = 0.7751), but significantly lower AUC than RF model (AUC = 1, P = 0.0138) (Fig. 3a). LS-SVMR model had a Youden’s index of 0.842. By the gray zone approach, two cut-off values were 0.084 and 0.160 (Fig. 4a). There were 90 (7.30%) patients involved in the gray zone. The in-hospital mortality was 0.38%, 2.22%, and 64.37% in patients with an LS-SVMR score of <0.084, 0.084–0.160, and >0.160, respectively (Table 2).

a All patients; b Patients with variceal bleeding; c Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment; d Patients who received pharmacological treatment alone without endoscopic treatment. The performance of LS-SVMR model was significantly higher than ANN, KNN, and decision tree, and statistically similar to XGBoost model, but significantly lower than RF both in overall and subgroup analyses. ANN artificial neural network, KNN K-nearest neighbors, RF random forest, LS-SVMR least square support vector machine regression.

a All patients; b Patients with variceal bleeding; c Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment; d Patients who received pharmacological treatment without endoscopic treatment. Patients were divided into low-, moderate-, and high-risk group of in-hospital death based on LS-SVMR score in overall and subgroup analyses.

In the subgroup analysis of patients with variceal bleeding, LS-SVMR model had a high AUC of 0.986 (Fig. 3b). It had a Youden’s index of 0.887. By the gray zone approach, two cut-off values were 0.080 and 0.082. There were 4 (0.54%) patients involved in the gray zone (Fig. 4b). The in-hospital mortality was 0.16%, 25%, and 19.10% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.080, 0.080–0.082, and >0.082, respectively (Table 2).

In the subgroup analysis of patients who underwent endoscopic treatment, LS-SVMR model had a high AUC of 0.983 (Fig. 3c). It had a Youden’s index of 0.858. By the gray zone approach, two cut-off values were 0.080 and 0.081 (Fig. 4c). There were 2 (0.28%) patients involved in the gray zone. The in-hospital mortality was 0.33%, 50%, and 24.18% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.080, 0.080–0.081, and >0.081, respectively (Table 2).

In the subgroup analysis of patients who received pharmacological treatment without endoscopic treatment, LS-SVMR model still had a high AUC of 0.987 (Fig. 3d). It had a Youden’s index of 0.921. By the gray zone approach, two cut-off values were 0.092 and 0.157 (Fig. 4d). There were 31 (6.70%) patients involved in the gray zone. The in-hospital mortality was 0.26%, 6.45%, and 72.34% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.092, 0.092–0.157, and >0.157, respectively (Table 2).

Regardless of overall or subgroup analysis in the training cohort, the DCA for the LS-SVMR model demonstrated a consistent net benefit over a range of threshold probabilities, and the LS-SVMR model outperformed the ‘treat none’ strategy, indicating its practical utility in decision-making (Supplementary Fig. 1). Regardless of overall or subgroup analysis, the calibration curve also showed that the LS-SVMR model achieved a good predictive performance (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The importance of each component of LS-SVMR model was calculated and ranked (Supplementary Fig. 3).

ML models based on the components of the CAGIB score in validation cohort

The performance of LS-SVMR model (AUC = 0.983) for predicting in-hospital death was also significantly better than ANN (AUC = 0.849, P < 0.001), KNN (AUC = 0.699, P < 0.001), decision tree (AUC = 0.599, P < 0.001), XGBoost (AUC = 0.823, P < 0.0001), and RF (AUC = 0.805, P < 0.0001) models in the validation cohort (Fig. 5a). The in-hospital mortality was 0.48%, 6.82%, and 64.71% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.084, 0.084–0.160, and >0.160, respectively (Table 2).

a All patients; b Patients with variceal bleeding; c Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment; d Patients who received pharmacological treatment alone without endoscopic treatment. The performance of LS-SVMR model was significantly higher than ANN, KNN, decision tree, XGBoost, and RF models both in overall and subgroup analyses. ANN artificial neural network, KNN K-nearest neighbors, RF random forest, LS-SVMR least square support vector machine regression.

In the subgroup analysis of patients with variceal bleeding, LS-SVMR model still had the highest AUC (AUC = 0.984) (Fig. 5b). The in-hospital mortality was 0.15%, 0%, and 20.95% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.080, 0.080–0.082, and >0.082, respectively (Table 2).

In the subgroup analysis of patients who underwent endoscopic treatment, LS-SVMR model still had the highest AUC (AUC = 0.980) (Fig. 5c). The in-hospital mortality was 0.16%, 0%, and 19.15% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.080, 0.080–0.081, and >0.081, respectively (Table 2).

In the subgroup analysis of patients who received pharmacological treatment without endoscopic treatment, LS-SVMR model still had the highest AUC (AUC = 0.984) (Fig. 5d). The in-hospital mortality was 1.06%, 19.23%, and 80.77% in patients with an LS-SVMR score <0.092, 0.092–0.157, and >0.157, respectively (Table 2).

Regardless of overall or subgroup analysis in the validation cohort, the DCA for the LS-SVMR model demonstrated a consistent net benefit over a range of threshold probabilities, and the LS-SVMR model outperformed the ‘treat none’ strategy, indicating its practical utility in decision-making (Supplementary Fig. 4). Regardless of overall or subgroup analysis, the calibration curve also showed that the LS-SVMR model achieved a good predictive performance (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Discussion

This is a large-scale study of real-world data prospectively collected from 23 centers. First of all, the performance of CAGIB score, which our group previously developed and internally validated, was further validated for predicting the risk of in-hospital death in patients with liver cirrhosis and AGIB, which should be equivalent to Child-Pugh, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, D’Amico, and Augustin scores. More importantly, based on the components of CAGIB score, LS-SVMR model was developed and internally validated for predicting in-hospital death in such patients, and substantially improved the predictive performance of its original score, CAGIB score, which was established by logistic regression model. Furthermore, cirrhotic patients with AGIB were stratified into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk of death groups according to the cut-off values from the LS-SVMR model.

In-hospital death was selected as the sole outcome of interest in our study. This was primarily because in-hospital death, a hard clinical endpoint, can be more accurately and unbiasedly observed during hospitalization, but not readily influenced by the difference in the selection of treatment modalities and assessment approaches among the centers. More notably, AGIB is a clinical emergency, where in-hospital survival can directly determine the patients’ discharge and really reflect the treatment efficacy. In comparison, other outcomes of interests, such as failure to control bleeding, 6-week mortality, re-admission, and hospitalization duration and cost, are sometimes dependent upon the treatment plan and discharge policy of each center. Besides, as observed during our follow-up visits, some patients died of unexpected causes other than bleeding at home after their hospital discharge, and thus, their causes of death could not be clearly recorded, even they would be lost to follow-up18,19.

To the best of our knowledge, ML approaches have rarely been employed for evaluating the outcomes of patients with AGIB. Shung et al. developed a ML-based model and showed that its AUC was higher than those of Glasgow-Blatchford, Rockall, and AIMS65 scores20. However, this ML-based model was dependent upon the data from general patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but not cirrhotic patients with AGIB. As known, cirrhotic patients with AGIB develop more severe bleeding with a higher risk of death21,22,23,24. In this setting, our study constructed an ML-based model, LS-SVMR model, based on the components of CAGIB score, which had a superior predictive performance. Furthermore, the risk stratification by the LS-SVMR model can be used for identifying the patients at a high risk of death during hospitalizations. Specifically, approximately one quarter of cirrhotic patients with AGIB assigned to the high-risk group will die, but nearly none of cirrhotic patients with AGIB assigned to the low-risk group will die.

Gastroesophageal varices and variceal bleeding, which are closely related to the severity of portal hypertension, are critical endpoints for the natural history of liver cirrhosis6. The annual incidence of the first variceal bleeding is 5-15% in general patients with cirrhosis, and even higher in patients with large varices or any varices with red signs on endoscopy and those with Child-Pugh class B/C25. If other decompensated events were concomitant in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, the 5-year mortality would be up to 80%26. Therefore, it should be necessary to identify which group of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding are at a high risk of death. Existing evidence suggests the controversy in the superiority of CAGIB score for the outcome prediction8,10. Our current study suggested the equivalence of CAGIB score with MELD 3.0, MELD-Na, and Child-Pugh scores for predicting the risk of in-hospital death in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, and its predictive performance was further improved by using LS-SVMR model.

Endoscopy is generally recommended within 24 h after admission in cirrhotic patients with AGIB2,3. Endoscopic epinephrine or thrombin injection, thermal therapy, and clipping are used for the treatment of non-variceal bleeding, of which peptic ulcer is the predominant cause. In comparison, EVL and EIS are the primary choices of endoscopic treatment for esophageal variceal bleeding27. Endoscopic tissue glue injection is employed for the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding, which is less common than esophageal variceal bleeding, but carries a higher mortality28,29,30. The popularization and improvement of endoscopic techniques and equipment have remarkably increased the rate of control bleeding31,32, but AGIB is still uncontrollable or refractory in some cases. Thus, it is also necessary to predict the risk of death among the AGIB patients who underwent endoscopic treatment. But the prediction model is lacking in such patients. It is worth noting that the LS-SVMR model outperformed CAGIB, MELD 3.0, MELD-Na, and Child-Pugh scores, enhancing its applicability in the clinical scenario of endoscopic procedures.

In some specific cases, such as very frail patients and those with mild diseases, and resource-limited settings where the access to experienced endoscopists and endoscopic treatment is difficult, AGIB can be managed by drugs alone. Similarly, in real-world studies, approximately 20% of patients with AGIB did not undergo endoscopy33,34. Of course, except for resuscitation and blood transfusion, pharmacological treatment should be the most important part of management strategy of AGIB3,35. Specifically, vasoactive drugs can reduce portal pressures via splanchnic vasoconstriction, thereby controlling bleeding and reducing mortality36,37; and antibiotics are also effective for decreasing the risk of rebleeding and death38,39. Despite pharmacological treatment can be often effective, some cases are still at a very high risk of failure to control bleeding and death, who should require immediate referral for endoscopic treatment and even TIPS. The LS-SVMR model should be more accurate than CAGIB, MELD 3.0, MELD-Na, and Child-Pugh scores in distinguishing the disease condition where pharmacological treatment alone may be inadequate.

Our study has several limitations. First, LS-SVMR model was not compared with Rockall40, Glasgow-Blatchford41, and AIMS6542 scores. Notably, these scores were designed for general patients with AGIB, rather than for cirrhotic patients with AGIB. The disease course and patients’ outcome are very different between them. Second, the management strategy of patients with liver cirrhosis and AGIB could not be homogenous among the participating centers, despite they were treated by experienced physicians at the department of gastroenterology and/or hepatology. Third, the external validation of LS-SVMR model is lacking, although our data are selected from multiple centers and more generalized. Finally, our current study only focused on in-hospital mortality, but did not explore other endpoints, such as post-discharge rebleeding, long-term complications, or quality of life.

In conclusion, on the basis of components of the CAGIB score, LS-SVMR model has been developed and showed excellent performance for predicting the in-hospital death in patients with cirrhosis and AGIB. Besides, it can be used for stratifying the risk of death, where the in-hospital mortality reaches up to two-thirds in patients at a high risk of death. Certainly, in the future, this ML-based model should be more comprehensively validated and considered to guide the treatment selection and patients’ referral.

Methods

Ethics and registration

This prospective observational study is being performed at 23 centers from Brazil, China, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey. The study protocol was first approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (ethical approval number: Y [2020] 038), followed by each center who agreed to participate in this multicenter study. Ethical committees and ethical approval number of each center were listed as follows: the First Affiliated Hospital of the Fujian Medical University (Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Fujian Medical University, ethical approval number: MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2020]423), Shuguang Hospital (IRB of the Shuguang Hospital of the Shanghai University of TCM, ethical approval number: 2022-1200-137-01), Xi’an Central Hospital (Ethics Committee of the Xi’an Central Hospital, ethical approval number: LSA-L-2021-004-01), São Paulo State University (UNESP) (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa FMB/UNESP, ethical approval number: 4.462.045), the Sixth People’s Hospital of Dalian (Ethics Committee of the Sixth People’s Hospital of Dalian, ethical approval number: 2020-028-001), Shandong Provincial Hospital (Ethics Committee of the Shandong Provincial Hospital, ethical approval number: SWYX:NO.2020-214), the First Hospital of China Medical University (Ethics Committee of the China Medical University, ethical approval number: 2020-375-2), the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Biomedical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, ethical approval number: XJTU1AF2021LSK-005), Rajagiri Hospital (Hospital Research Review Board and The Trials Oversight Committee, ethical approval number: COEGIS/TLI/RJH-04/2021 (EXT)), the 960th Hospital of Chinese PLA (Medical Ethical Committee of the 960th Hospital of Chinese PLA, ethical approval number: [2021]154), Chiang Mai University (Research Ethics Committee Panel 5 Faculty of Medicine, ethical approval number: MED-2566-0937), Air Force Hospital of Northern Theater Command (Medical Ethical Committee of the Air Force Hospital of Northern Theater Command, ethical approval number: 2020-001), National Autonomous University of Mexico (Comité de Ética en Investigación de Médica Sur, S.A.B. de C.V., ethical approval number: 12-2020CEI-87), Bezmialem Vakif University Hospital (Bezmialem Vakif Üniversitesi Girisimsel Olmayan Arastirmalar Etik Kurulu, ethical approval number: 20/387 01.12.2020), the Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang (Ethics Committee of the Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang, ethical approval number: 2020-10-004-01), Beijing Youan Hospital (Ethics Committee of the Beijing Youan Hospital, ethical approval number: [2021]021), Union Hospital of the Tongji Medical College of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Ethics Committee of the Tongji Medical College of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ethical approval number: [2021]0058-01), Azienda di Rilievo Nazionale ad Alta Specializzazione Civico-Di Cristina-Benfratelli (Il Comitato Etico Palermo 2, ethical approval number: 296CIVICO2020), Charité University Medical Center (Ethikausschuss am Campus Virchow-Klinikum, ethical approval number: EA2/056/21), the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, ethical approval number: IIT[2021]006), Tangdu Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University (IEC of Institution for National Drug Clinical Trials, ethical approval number: K202012-01), and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, ethical approval number: 2020059). Patients’ informed consents were waived by the ethical committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Fujian Medical University, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Tangdu Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University, the Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang, Union Hospital of the Tongji Medical College of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and Shandong Provincial Hospital due to the observational nature of this study that only the data was obtained from electronic medical records without any additional harms to patients. But they were obtained at the remaining centers. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki43 and registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04662918) on Dec 9, 2020, as previously reported44,45.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All eligible patients were consecutively enrolled from these participating centers since September 30, 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with liver cirrhosis; (2) patients with AGIB who presented with hematemesis, melena, and/or hematochezia; and (3) adults (age >18 years). Patients would be excluded, if any component of Child-Pugh, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), or CAGIB scores was missing.

Study implementation

Once the ethical approval document was obtained from any participating center, the investigators were invited to collect the data in the Wen Juan Xing website (https://www.wjx.cn/), as previously employed46, where an electronic case report form was designed including 78 questions described in both Chinese and English language. All collected data were de-identified and kept confidential. A group of investigators who worked at the Department of Gastroenterology of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command was responsible for checking the accuracy of data collected from all participating centers, and sending a newsletter regarding the total number of patients enrolled at the first two days of every month. The data collection for the current analysis was stopped on June 30, 2023. Subsequently, all data collected from each participating center was further self-checked and repeatedly validated. During the period from August 2023 to January 2024, the investigators at each participating center were asked to check the data accuracy by reviewing the medical records of included patients, and then this group of investigators who worked at the Department of Gastroenterology of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command repeated this work until the accuracy of all data collected was validated and all potentially ineligible or inaccurate data were excluded.

Case report form

The case report form was divided into four sections. Baseline data includes age, sex, etiology of liver cirrhosis (hepatitis B virus [HBV], hepatitis C virus [HCV], alcohol, and autoimmune), history of GIB, diabetes, AGIB manifestations, HCC, ascites, acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and laboratory tests at admission, which mainly includes hemoglobin (Hb), white blood cell (WBC), platelet (PLT), TBIL, ALB, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, alkaline phosphatase (AKP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), Scr, cystatin (Cys)-C, potassium (K), sodium (Na), and international normalized ratio (INR). Endoscopy-related data includes endoscopic examinations, diagnosis of esophageal or gastric varices by endoscopy at admission, diagnosis of variceal bleeding by endoscopy at admission, diagnosis of peptic ulcer bleeding by endoscopy at admission, endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL), endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS), and endoscopic tissue glue injection. Pharmacology-related data includes transfusion, terlipressin, octreotide, somatostatin, and antibiotics during hospitalization, and other treatment-related data includes liver transplantation (LT) and TIPS. Outcome data includes failure to control bleeding and death.

Scores and definitions

As previously reported, Child-Pugh47,48, MELD-Na49, MELD 3.050, D’Amico model51, Augustin model52, and CAGIB7 scores were calculated. AGIB53 was defined as cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding presenting with hematemesis, melena, and/or hematochezia within five days before this admission. Failure to control bleeding54 was defined as one of the following criteria developed at a time frame of five days: (1) death; (2) fresh hematemesis or nasogastric aspiration of ≥100 ml of fresh blood ≥2 h after starting a specific drug treatment or therapeutic endoscopy; (3) development of hypovolemic shock; and (4) 30 g/L drop in Hb concentration (9% drop of HCT) within 24 h, if no transfusion is administered.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), MedCalc software version 11.4.2.0 (MedCale, Mariakerke, Belgium), and R software version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Random sampling was used to divide the patients into training and validation cohorts with an approximate percentage of 50%. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and median (range), and categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). Differences between training and validation cohorts were evaluated by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test55 or the chi square test56, if appropriate. The area under curve (AUC)57 of CAGIB score was calculated and compared with those of Child-Pugh score, MELD-Na score, MELD 3.0 score, D’Amico model, and Augustin model by the Delong’s test58. Furthermore, in the training cohort, six ML-based models, including artificial neural network [ANN]59, k-nearest neighbors [KNN]60, decision tree61, random forest (RF)62, XGBoost63, and least square support vector machine regression [LS-SVMR]64, were established based on the components of CAGIB score. Specifically, the ANN model has 12 nodes and 1 hidden layer; the k value for the KNN model is 5; the complexity parameter of the decision tree model is 0.000001; the number of trees for RF is 500; in the XGBoost model, the eta is 0.1, the max_depth is 6, gama parameter is 0, the min child weight is 1, and the number of rounds is 200; and the sigma parameter and gama parameter of LS-SVMR model are 1 and 10, respectively. Cross-validation was conducted in the training cohort for each ML-based model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC)65 curve analyses were performed to evaluate their predictive performance. AUCs of these ML-based models were calculated and compared by the Delong’s test. The best ML-based model was further identified with its Youden’s index66. Gray zone was defined as inconclusive prediction for values with a sensitivity or specificity lower than 90% (i.e., a diagnosis tolerance of 10%)67,68. According to the gray zone approach, two cut-off values were proposed, which constitute the borders of the gray zone. The first and second cut-off values exclude and include a high risk of death with near certainty, respectively69. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were performed in patients with a definite diagnosis of variceal bleeding on endoscopy, those who underwent endoscopic treatment, and those who received pharmacological treatment alone. Decision curve analysis (DCA)70,71 and calibration curve72 were used to assess the predictive performance of the best model. The predictive performance of CAGIB score and ML-based models were further evaluated in the validation cohort. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

To protect patient privacy, other patient related data are not publicly accessible. However, all data are available upon reasonable request emailed to the corresponding author (X.Q.).

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable requests from the corresponding author (X.Q.).

Abbreviations

- ACLF:

-

acute-on-chronic liver failure

- AGIB:

-

acute gastrointestinal bleeding

- AI:

-

artificial intelligence

- AKP:

-

alkaline phosphatase

- ALB:

-

albumin

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- ANN:

-

artificial neural network

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUC:

-

area under curve

- Cys:

-

cystatin

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis

- DT:

-

decision tree

- EIS:

-

endoscopic injection sclerotherapy

- EVL:

-

endoscopic variceal ligation

- GGT:

-

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

- HBV:

-

hepatitis B virus

- Hb:

-

hemoglobin

- HCV:

-

hepatitis C virus

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HE:

-

hepatic encephalopathy

- INR:

-

international normalized ratio

- K:

-

potassium

- KNN:

-

K-nearest neighbors

- LS-SVMR:

-

least square support vector machine regression

- LT:

-

liver transplantation

- ML:

-

machine learning

- MELD:

-

model for end-stage liver disease

- Na:

-

sodium

- PPIs:

-

proton pump inhibitors

- PLT:

-

platelet

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- Scr:

-

serum creatinine

- TBIL:

-

total bilirubin

- TIPS:

-

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

- WBC:

-

white blood cell.

References

Tokar, J. L. & Higa, J. T. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann. Intern Med. 175, ITC17–ITC32 (2022).

de Franchis, R. et al. Baveno VII - Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 76, 959–974 (2022).

Stanley, A. J. & Laine, L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 364, l536 (2019).

Diaz-Soto, M. P. & Garcia-Tsao, G. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in liver cirrhosis: a recent update. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 15, 17562848221101712 (2022).

Tapper, E. B. & Parikh, N. D. Diagnosis and Management of Cirrhosis and Its Complications: A Review. JAMA 329, 1589–1602 (2023).

Garcia-Tsao, G. & Bosch, J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med 362, 823–832 (2010).

Bai, Z. et al. Development and Validation of CAGIB Score for Evaluating the Prognosis of Cirrhosis with Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Adv. Ther. 36, 3211–3220 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. The Prognosis Analysis of Liver Cirrhosis with Acute Variceal Bleeding and Validation of Current Prognostic Models: A Large Scale Retrospective Cohort Study. Biomed. Res Int 2020, 7372868 (2020).

He, Q., Yu, B. & Xiao, Y. Risk factors of rebleeding in cirrhotic patients with esophageal gastric variceal bleeding after endoscopic treatment. Chin. Hepatolgy 28, 55–60 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Development and validation of a practical prognostic nomogram for evaluating inpatient mortality of cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Ann. Hepatol. 28, 101086 (2023).

Haug, C. J. & Drazen, J. M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1201–1208 (2023).

Lu, F. et al. Artificial intelligence in liver diseases: Recent advances. Adv. Ther. 41, 967–990 (2024).

Ahn, J. C., Connell, A., Simonetto, D. A., Hughes, C. & Shah, V. H. Application of artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and treatment of liver diseases. Hepatology 73, 2546–2563 (2021).

Huang, H. et al. A 7 gene signature identifies the risk of developing cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 46, 297–306 (2007).

Sarvestany, S. S. et al. Development and validation of an ensemble machine learning framework for detection of all-cause advanced hepatic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health 4, e188–e199 (2022).

Rui, F. et al. Development of a machine learning-based model to predict hepatic inflammation in chronic hepatitis B patients with concurrent hepatic steatosis: a cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 68, 102419 (2024).

Rui, F. et al. Machine learning-based models for advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis diagnosis in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatic steatosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 22, 2250-2260 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Impact of asymptomatic superior mesenteric vein thrombosis on the outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis. Thromb. Haemost. 122, 2019–2029 (2022).

Bai, Z. et al. Effects of short-term human albumin infusion for the prevention and treatment of hyponatremia in patients with liver cirrhosis. J. Clin. Med. 12, 107 (2022).

Shung, D. L. et al. Validation of a machine learning model that outperforms clinical risk scoring systems for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 158, 160–167 (2020).

Nahon, S. et al. Epidemiological and prognostic factors involved in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Results of a French prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 44, 998–1008 (2012).

Hearnshaw, S. A. et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut 60, 1327–1335 (2011).

Reverter, E. et al. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 146, 412–419.e413 (2014).

Abougergi, M. S., Travis, A. C. & Saltzman, J. R. The in-hospital mortality rate for upper GI hemorrhage has decreased over 2 decades in the United States: a nationwide analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81, 882–888.e881 (2015).

Jakab, S. S. & Garcia-Tsao, G. Screening and Surveillance of Varices in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 26–29 (2019).

D’Amico, G. et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 39, 1180–1193 (2014).

Laine, L. & Cook, D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann. Intern Med 123, 280–287 (1995).

Sarin, S. K., Lahoti, D., Saxena, S. P., Murthy, N. S. & Makwana, U. K. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology 16, 1343–1349 (1992).

Tripathi, D. et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut 64, 1680–1704 (2015).

Lo, G. H., Lai, K. H., Cheng, J. S., Chen, M. H. & Chiang, H. T. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology 33, 1060–1064 (2001).

Mullady, D. K., Wang, A. Y. & Waschke, K. A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Therapies for Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 159, 1120–1128 (2020).

Lau, L. H. S. & Sung, J. J. Y. Treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in 2020: New techniques and outcomes. Dig. Endosc. 33, 83–94 (2021).

Laine, L. et al. Severity and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with bloody vs. coffee-grounds hematemesis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 113, 358–366 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding manifestations at admission on the in-hospital outcomes of liver cirrhosis: Hematemesis versus melena without hematemesis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 31, 1334–1341 (2019).

Orpen-Palmer, J. & Stanley, A. J. Update on the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Med 1, e000202 (2022).

Avgerinos, A., Nevens, F., Raptis, S. & Fevery, J. Early administration of somatostatin and efficacy of sclerotherapy in acute oesophageal variceal bleeds: the European Acute Bleeding Oesophageal Variceal Episodes (ABOVE) randomised trial. Lancet 350, 1495–1499 (1997).

Levacher, S. et al. Early administration of terlipressin plus glyceryl trinitrate to control active upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Lancet 346, 865–868 (1995).

Bernard, B. et al. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 108, 1828–1834 (1995).

Chavez-Tapia, N. C., Barrientos-Gutierrez, T., Tellez-Avila, F. I., Soares-Weiser, K. & Uribe, M. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD002907 (2010).

Rockall, T. A., Logan, R. F., Devlin, H. B. & Northfield, T. C. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 38, 316–321 (1996).

Blatchford, O., Davidson, L. A., Murray, W. R., Blatchford, M. & Pell, J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: Case ascertainment study. BMJ 315, 510–514 (1997).

Saltzman, J. R. et al. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. 74, 1215–1224 (2011).

Goodyear, M. D., Krleza-Jeric, K. & Lemmens, T. The Declaration of Helsinki. BMJ 335, 624–625 (2007).

Yin, Y. et al. Impact of peptic ulcer bleeding on the in-hospital outcomes of cirrhotic patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding: An international multicenter study. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, 473-483 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Impact of thrombocytopenia on failure of endoscopic variceal treatment in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 18, 17562848241306934 (2025).

Bai, Z. et al. Use of albumin infusion for cirrhosis-related complications: An international position statement. JHEP Rep. 5, 100785 (2023).

Child, C. G. & Turcotte, J. G. Surgery and portal hypertension. Major Probl. Clin. Surg. 1, 1–85 (1964).

Pugh, R. N., Murray-Lyon, I. M., Dawson, J. L., Pietroni, M. C. & Williams, R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br. J. Surg. 60, 646–649 (1973).

Kim, W. R. et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N. Engl. J. Med 359, 1018–1026 (2008).

Kim, W. R. et al. MELD 3.0: The model for end-stage liver disease updated for the modern era. Gastroenterology 161, 1887–1895.e1884 (2021).

D’Amico, G., De Franchis, R. & Cooperative Study, G. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology 38, 599–612 (2003).

Augustin, S. et al. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 106, 1787–1795 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of admission time on the outcomes of liver cirrhosis with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Regular hours versus off-hours admission. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3541365 (2018).

de Franchis, R. & Baveno, V. F. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 53, 762–768 (2010).

Perme, M. P. & Manevski, D. Confidence intervals for the Mann-Whitney test. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 28, 3755–3768 (2019).

McHugh, M. L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med. (Zagreb) 23, 143–149 (2013).

de Hond, A. A. H., Steyerberg, E. W. & van Calster, B. Interpreting area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. Lancet Digit Health 4, e853–e855 (2022).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Rogers, S. K., Ruck, D. W. & Kabrisky, M. Artificial neural networks for early detection and diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Lett. 77, 79–83 (1994).

Zhang, Z. Introduction to machine learning: k-nearest neighbors. Ann. Transl. Med 4, 218 (2016).

Hammann, F. & Drewe, J. Decision tree models for data mining in hit discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 7, 341–352 (2012).

Hu, J. & Szymczak, S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief Bioinform 24, bbad002 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Predicting mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in the ICU using XGBoost model. PLoS One 16, e0246306 (2021).

Liu, X., Dong, X., Zhang, L., Chen, J. & Wang, C. Least squares support vector regression for complex censored data. Artif. Intell. Med. 136, 102497 (2023).

Tripepi, G., Jager, K. J., Dekker, F. W. & Zoccali, C. Diagnostic methods 2: receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Kidney Int. 76, 252–256 (2009).

Hughes, G. Youden’s index and the weight of evidence. Methods Inf. Med. 54, 198–199 (2015).

Biais, M. et al. Clinical relevance of pulse pressure variations for predicting fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients: the grey zone approach. Crit. Care 18, 587 (2014).

Cannesson, M. et al. Assessing the diagnostic accuracy of pulse pressure variations for the prediction of fluid responsiveness: a “gray zone” approach. Anesthesiology 115, 231–241 (2011).

Ray, P., Le Manach, Y., Riou, B. & Houle, T. T. Statistical evaluation of a biomarker. Anesthesiology 112, 1023–1040 (2010).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis. Mak. 26, 565–574 (2006).

Kerr, K. F., Brown, M. D., Zhu, K. & Janes, H. Assessing the clinical impact of risk prediction models with decision curves: Guidance for correct interpretation and appropriate use. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2534–2540 (2016).

Steyerberg, E. W. et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 21, 128–138 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the colleagues from 23 participating centers of the V-CAGIB study, who are not listed as the authors of this paper, for their great contributions to establish and verify this prospective international multicenter database, including Yuhang Yin, Sijia Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Yan He, Guo Lin, Di Sun, Yao Xiao, Xu Gao, Shoujie Zhao, Zhenhua Liu, Qinghe Cheng, Yunxin Wang, Hao Jiang, Yan Feng, Yaning Zhang, Botao Ning, Na Sun, Jinling Dong, Wenming Wu, Jian Zhang, Emine Mutlu, Stephany Castillo-Castañeda, Giuseppe Butera, Alberto Maringhini, and Fernando Gomes Romeiro. The abstract was partly accepted as an oral presentation at the Asian Pacific Digestive Week (APDW) 2024 Conference. This study received the funding from the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Liaoning Province (2022-YQ-07), The National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2507500), Science and Technology Plan Project of Liaoning Province (2022JH2/101500032), and Independent Research Funding of General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (ZZKY2024018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: X.Q.; Methodology: Z.B. and X.Q.; Validation: Z.B., L.L., B.L., S.L., F.J., M.B.M., M.S., Q.Z., D.M., S.Y., Y.H., X.L., C.A.P., N.M.S., M.B., K.P., Y.L., Y.W., Y.C., L.Y., L.S., A.M., F.T., and X.Q.; Formal analysis: Z.B. and X.Q.; Investigation: Z.B., L.L., B.L., S.L., F.J., M.B.M., M.S., Q.Z., D.M., S.Y., Y.H., X.L., C.A.P., N.M.S., M.B., K.P., Y.L., Y.W., Y.C., L.Y., L.S., A.M., F.T., and X.Q.; Data curation: Z.B., L.L., B.L., S.L., F.J., M.B.M., M.S., Q.Z., D.M., S.Y., Y.H., X.L., C.A.P., N.M.S., M.B., K.P., Y.L., Y.W., Y.C., L.Y., L.S., A.M., F.T., and X.Q.; Writing–original draft: Z.B. and X.Q.; Writing–review and editing: Z.B., L.L., B.L., S.L., F.J., M.B.M., M.S., Q.Z., D.M., S.Y., Y.H., X.L., C.A.P., N.M.S., M.B., K.P., Y.L., Y.W., Y.C., L.Y., L.S., A.M., F.T., and X.Q.; Supervision: X.Q.; Project administration: X.Q. All authors have made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript and approved the submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, Z., Lin, S., Sun, M. et al. Machine learning based CAGIB score predicts in-hospital mortality of cirrhotic patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. npj Digit. Med. 8, 489 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01883-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01883-w