Abstract

Predicting multiple postoperative complications remains challenging in perioperative care. Current approaches often address complications individually, limiting the potential for integrated risk assessment. We developed and externally validated a scalable, interpretable, tree-based multitask learning model to predict three critical postoperative outcomes—acute kidney injury (AKI), postoperative respiratory failure (PRF), and in-hospital mortality—using 16 preoperative features generally available in electronic health records. Our model achieved AUROCs of 0.805, 0.789, and 0.863 for AKI; 0.886, 0.925, and 0.911 for PRF; and 0.907, 0.913, and 0.849 for mortality in the derivation cohort and external validation cohorts A and B, respectively (all p < 0.001, except for AKI in derivation and PRF in cohort B). We also elucidated the contribution of each input variable to predictions among different outcomes. Our findings highlight the potential of multitask learning to streamline preoperative risk assessment and present a scalable, interpretable, and generalizable framework for improving perioperative care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Post-surgical complications occur in approximately 40% of cases, with the types of complications varying based on patient characteristics1. These complications can profoundly affect patient recovery, quality of life, and hospital costs2,3. Therefore, identifying patients at high risk of postoperative complications during the preoperative period and providing individualized care is crucial for improving patient outcomes.

Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have revolutionized medical applications, enabling algorithms to address complex challenges across various fields4. Numerous AI-based prediction models have demonstrated strong performance in predicting perioperative clinical outcomes5. However, their clinical implementation remains limited, primarily due to issues with generalizability6,7. Rigorous evaluation on datasets independent of the initial training datasets is essential to ensure robust performance before these models can be integrated into clinical practice8. Although some AI models to predict postoperative outcomes, such as acute kidney injury (AKI), postoperative respiratory failure (PRF), and in-hospital mortality, have undergone external validation, many have struggled to maintain their performance in these validations9,10,11.

Current approaches to predicting surgical outcomes typically involve developing separate models for individual complications. While effective in specific contexts, this single-outcome approach has limited clinical utility because it fails to capture the interdependencies among different outcomes12. This single-outcome approach significantly limits the model’s utility in real-world clinical settings, where multiple complications must be considered concurrently. Simultaneous prediction of multiple complications is critical, as complications may arise during different phases of postoperative recovery and require distinct intervention strategies13. Furthermore, a comprehensive risk profile equips surgeons with the information needed to prepare for various scenarios, optimize resource allocation for postoperative care, and implement targeted preventive measures tailored to each patient’s risk factors14.

In this context, multitask learning algorithms offer a promising solution to these challenges by leveraging the relationships among related tasks, potentially leading to more robust and generalizable models15,16. This approach is particularly advantageous in the medical domain, where different complications often share common risk factors and physiological pathways. Although previous studies have highlighted the potential of multitask learning in medical prediction17,18, most relied on deep neural networks, which present challenges in interpreting how individual features contribute to predictions. Recently, a tree-based multitask learning algorithm, the multitask gradient boosting machine (MT-GBM), was introduced19. However, its application in real-world medical prediction tasks remains largely unexplored. Additionally, many existing prediction models in perioperative medicine rely on extensive input variables, which limits their practical implementation across different healthcare settings20,21. A prediction model using a minimal set of readily available preoperative variables would be more feasible for widespread clinical adoption. Furthermore, recent studies using multimodal multitask learning have shown promising results but were limited to internal validation using single-center data, highlighting the need for external validation using multicenter data22,23.

To address these challenges, we aimed to develop and externally validate a tree-based generalizable multitask learning model to simultaneously predict three major postoperative complications—AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality in non-cardiac surgery patients. We focused on minimal preoperative variables to enhance feasibility across institutions. We hypothesized that leveraging the shared representation of these outcomes would improve predictive performance over single-outcome models while maintaining generalizability and interpretability.

Results

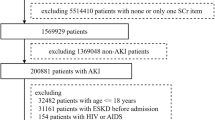

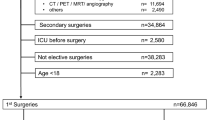

During the study period, a total of 72,686 cases met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the derivation cohort. After excluding 6534 cases, data from the remaining 66,152 cases were used for the final analysis (Fig. 1). Validation Cohort A included 13,285 cases from Nowon Eulji Medical Center, collected between January 2018 and August 2023, a secondary-level general hospital. Validation Cohort B consisted of 2813 cases collected between August 2021 and December 2021 from Korea University Guro Hospital, a tertiary-level academic referral hospital.

Baseline characteristics, such as demographic and perioperative variables, are presented in Table 1. The proportion of patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class ≥3 was highest in Validation Cohort B, followed by the derivation cohort and Validation Cohort A (45.1% vs. 26.8% vs. 23.3%, respectively). Validation Cohort B also had the highest proportion of emergency surgeries (7.5%), followed by the derivation cohort (5.1%) and Validation Cohort A (0.9%). General surgery was the most common procedure in the derivation cohort (34.6%), followed by orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. In contrast, orthopedic surgery was the most frequent procedure in both validation cohorts, followed by general surgery. Information regarding the proportion of missing data for demographic and preoperative laboratory variables across the derivation and validation cohorts is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The incidence of postoperative complications varied across cohorts. In the derivation cohort, the incidence rates were 3.00% for AKI, 0.94% for PRF, and 0.55% for in-hospital mortality. Corresponding rates in Validation Cohort A were 3.96%, 1.75%, and 1.40%, respectively, while Validation Cohort B reported rates of 3.50%, 1.34%, and 2.97%, respectively.

Feature selection was performed independently for each outcome using the BorutaSHAP algorithm. For AKI prediction, ten variables were identified, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), duration of anesthesia, type of surgery (orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery), ASA class, and three preoperative laboratory test results (hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and serum albumin). For postoperative respiratory failure, seven variables were selected: age, ASA class, duration of anesthesia, orthopedic surgery, obstetric-urologic surgery, and two preoperative test results (WBC counts and serum albumin). Similarly, seven variables were identified for in-hospital mortality prediction, including ASA class, aspartate aminotransferase, and five preoperative test results (WBC counts, glucose, platelet, prothrombin time, and serum albumin). A union set of 16 variables, encompassing all features selected for each outcome, was used to train the MT-GBM model.

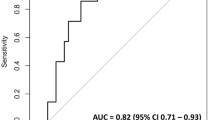

The AUROCs of the MT-GBM model were generally higher or showed no significant difference compared with those of the single-task model across most outcomes and cohorts (Table 2 and Fig. 2). For postoperative AKI, while there was no significant difference in AUROCs between the MT-GBM and single-task AKI prediction models in the derivation cohort (0.805 [95% CI: 0.798–0.812] vs. 0.801 [0.794–0.807], p = 0.061), MT-GBM model demonstrated significantly higher AUROCs on the validation datasets (0.789 [95% CI: 0.782–0.796] vs. 0.783 [0.776–0.790], p = 0.031 in Validation Cohort A, and 0.863 [95% CI: 0.850–0.876] vs. 0.826 [0.812–0.840], p < 0.001 in Validation Cohort B).

This figure presents AUROC curves for the multitask gradient boosting machine (MT-GBM) model, single-task prediction models, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification in the derivation and validation cohorts. The left, middle, and right columns represent the derivation cohort, Validation Cohort A, and Validation Cohort B, respectively. A Predictions for acute kidney injury, B Predictions for postoperative respiratory failure, and C Predictions for in-hospital mortality. In each plot, the blue, yellow, and green lines indicate the MT-GBM model, single-task prediction model (LightGBM), and ASA classification, respectively. ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification, AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

For PRF, the MT-GBM model also had significantly higher AUROCs than the single-task PRF prediction models (0.886 [95% CI: 0.880–0.891] vs. 0.874 [0.869–0.880], p = 0.001 in the derivation cohort; and 0.925 [0.920–0.929] vs. 0.917 [0.912–0.922], p < 0.001 in Validation Cohort A). However, there was no significant difference in Validation Cohort B (p = 0.491). For in-hospital mortality, the MT-GBM model showed significantly higher AUROCs than the single-task models (0.907 [95% CI: 0.902–0.912] vs. 0.852 [0.846–0.858], p < 0.001 in the derivation cohort; and 0.913 [0.909–0.918] vs. 0.902 [0.897–0.907], p < 0.001 in Validation Cohort A; and 0.849 [0.835–0.862] vs. 0.805 [0.790–0.820], p < 0.001 in Validation Cohort B).

The MT-GBM model yielded higher area under the precision–recall curve (AUPRC) values compared to the single-task model in all cohorts (AKI: derivation cohort 0.160 [95% CI: 0.154–0.166], Validation Cohort A 0.143 [95% CI: 0.137–0.149], Validation Cohort B 0.252 [95% CI: 0.236–0.268]; PRF: derivation cohort 0.126 [95% CI: 0.121–0.132], Validation Cohort A 0.293 [95% CI: 0.285–0.300], Validation Cohort B 0.236 [95% CI: 0.221–0.253]; in-hospital mortality: derivation cohort 0.080 [95% CI: 0.075–0.085], Validation Cohort A 0.179 [95% CI: 0.172–0.185], Validation Cohort B 0.180 [95% CI: 0.166–0.194), with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) except for AKI (Validation Cohort A), PRF (Validation Cohort B) and in-hospital mortality (derivation and Validation Cohort B). However, single-task models showed higher F1-scores in most cohorts and outcomes. (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

The MT-GBM model consistently outperformed the ASA physical status classification across all outcomes and cohorts. Additionally, it demonstrated superior performance compared to other tree-based models (Random Forest and XGBoost), with detailed results presented in Supplementary Table S2. Calibration curves and metrics of these models on the different postoperative outcomes are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S4. Decision curve analysis demonstrated that the MT-GBM model provided comparable net benefit to single-task models, while showing modest superiority over ASA physical status classification, particularly for AKI prediction at low threshold probabilities, highlighting its clinical utility for early identification and intervention in at-risk patients (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3 presents the SHAP summary plots for each outcome using the 16-variable union feature set. Despite slight differences in how variables influenced predictions for each outcome, older age, higher ASA class, male sex, longer anesthesia duration, and lower levels of albumin and hemoglobin, as well as higher levels of serum creatinine, glucose, and WBC counts, were consistently associated with postoperative complications. SHAP dependence plots further illustrate the relationship between each feature’s value and its SHAP value, providing a detailed view of how each variable contributes to the model’s predictions (Fig. 4).

This figure shows SHAP summary plots presenting the contributions of the 16 features used in the final model to the predictions across all outcomes. A Predictions for postoperative acute kidney injury, B Predictions for postoperative respiratory failure, C Predictions for in-hospital mortality. ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification, AST aspartate transaminase, BMI body mass index, Hb hemoglobin, INR international normalized ratio, PT prothrombin time, WBC white blood cell.

This figure shows SHAP dependence plots for the 11 selected continuous features in the final model, illustrating the relationship between each feature’s value and its SHAP value in the test dataset of the derivation cohort: A Predictions for postoperative acute kidney injury, B Predictions for postoperative respiratory failure, C Predictions for in-hospital mortality. From left to right: (1) age, (2) duration of anesthesia (DoA), (3) body mass index (BMI), (4) preoperative albumin, (5) preoperative creatinine (sCr), (6) preoperative glucose, (7) aspartate transaminase (AST), (8) preoperative hemoglobin (Hb), (9) preoperative platelet (Plt), (10) preoperative prothrombin time (PTINR), and (11) preoperative white blood cell counts (WBC).

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we developed and externally validated an interpretable, tree-based multitask learning model to simultaneously predict three critical postoperative outcomes—AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality—in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. The MT-GBM model demonstrated superior predictive performance using a single, easily extractable feature set from electronic health records (EHR), outperforming single-task prediction models across all clinical outcomes and maintaining predictive performance on external validation datasets. Additionally, SHAP analysis provided transparent insights into the model’s decision-making process by identifying key features contributing to predictions across different outcomes.

One of the strengths of our model lies in its predictive performance during external validation while using only a minimal set of readily extractable EHR variables. This addresses a major limitation of prior studies, which frequently reported significant performance declines during external validation10,24,25,26,27. Although previous efforts have proposed solutions such as model updating26 or additional training on local datasets10 to overcome generalizability, our model maintained its performance without requiring such modifications. The MT-GBM model consistently demonstrated superior predictive performance across most outcomes in derivation and validation cohorts. However, no statistically significant differences were observed for certain outcomes in Validation Cohort B. This finding suggests that while the MT-GBM model generally outperformed single-task models, its advantages may be less pronounced in smaller validation datasets. These findings demonstrate the need to explore multitask learning approaches further to ensure consistent performance across diverse datasets and clinical settings.

While AUROC measures overall discrimination, the AUPRC integrates precision and recall across thresholds, offering a more meaningful assessment when predicting rare complications28. We observed that the MT-GBM model generally achieved higher AUPRC values, indicating stronger precision–recall performance in class-imbalanced settings than single-task models, which was consistent with other multitask learning models29. This advantage implies that, across varying thresholds, the MT-GBM can more consistently identify at-risk patients without disproportionately increasing false positives. Consequently, it may be suitable for real-world clinical settings requiring simultaneous prediction of multiple complications, particularly when the incidence of these complications is generally low. This characteristic may support the reliable identification of at-risk patients in diverse clinical settings, but further validation across heterogeneous cohorts is needed.

In clinical practice, surgeons and anesthesiologists generally assess multiple potential postoperative complications simultaneously rather than focusing on a single complication. Thus, even modest improvements in predictive performance may be clinically meaningful when using a multitask learning model aligned with real-world decision-making. From a systems integration standpoint, relying on a single streamlined data pipeline with minimal, commonly available features also simplifies model deployment and operational efficiency compared to managing separate single-outcome models30. These practical advantages highlight the potential benefits and applicability of multitask learning models in perioperative care.

Multitask learning algorithms train on interrelated tasks simultaneously, enhancing the predictive performance of each task by sharing complementary information through mutual regularization31. Although previous applications have shown promise, they faced limitations. For example, a deep neural network-based multitask learning model accurately predicted postoperative outcomes such as mortality, AKI, and reintubation17. However, this model suffered from limited interpretability and lacked external validation. Other studies using deep learning-based multitask learning models to predict ICU outcomes, including shock, acute renal failure, mortality, diagnosis, length of hospital stays, and physiologic decline, also relied heavily on open datasets and lacked both interpretability and external validation18,32. Our tree-based approach addresses these limitations while preserving the core advantages of multitask learning.

Recent studies have highlighted the potential of tree-based multitask learning for clinical predictions. One study developed a hybrid tree-based multitask learning framework that dynamically adapts split strategies at each node, enhancing accuracy while mitigating overfitting33. Another study employed an interpretable multitask learning method using explainable boosting machines to simultaneously predict maternal complications, such as severe maternal morbidity and preeclampsia34. Similarly, a separate investigation utilized multitask learning with tree-based models, leveraging XGBoost to predict multiple illnesses across 41 diseases with superior performance35. These studies demonstrated that tree-based multitask learning improves predictive accuracy and preserves clinical interpretability, making it an effective approach for addressing multiple clinical outcomes.

The superior performance of our multitask learning model can be attributed to two principal mechanisms. First, by learning a shared representation learning across all outcomes, the model both captures the underlying physiological relationships among different postoperative complications32 and facilitates efficient transfer of knowledge between tasks. Second, the simultaneous prediction of multiple outcomes acts as an implicit regularization mechanism that reduces the risk of overfitting to any single outcome36. Third, the model’s architecture facilitates efficient knowledge transfer across tasks, enabling insights from one outcome to enhance the prediction of related outcomes37. It is important to note that our multitask learning did not exhibit performance degradation (negative transfer) in any of the tasks compared to single-task models, which is often a concern in multitask learning settings38. This absence of negative transfer is likely due to the presence of shared risk factors among postoperative outcomes, where common physiological mechanisms enabled effective knowledge sharing across tasks39. Furthermore, the performance gains of our MT-GBM model are not merely due to having access to a larger feature set. Even if single-task models were given all 16 features, they did not achieve the same combined performance due to the lack of shared representation learning. The multitask learning enables the model to discover common patterns and interdependencies between complications that separate models cannot capture. By learning these shared representations, MT-GBM develops a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms linking preoperative variables to multiple postoperative outcomes.

While most prediction models target a single outcome, clinicians often consider various postoperative complications that may affect postoperative recovery during the patient’s hospital stays. Multitask learning aligns closely with the clinician’s decision-making processes, which typically involve the simultaneous consideration of multiple adverse events40. This approach leverages the interconnectedness of different body systems and their susceptibility to disease41,42. A previous study emphasized that prediction models for multiple outcomes should account for correlations among these outcomes43. Our analysis revealed strong correlations between AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality, suggesting shared underlying risk factors and physiological pathways that our multitask learning model effectively captures. Further research is needed to explore how the strength of these correlations affects the performance benefits of multitask learning.

Prediction models that rely on numerous input variables often face challenges related to generalizability and reproducibility20,21. Some models have used as many as 3599 variables to predict AKI9 and 285 variables to predict eight postoperative complications44. In another study, a deep neural network-based multitask learning model used 46 features, including intraoperative hemodynamics and medication records, to predict clinical outcomes; however, these features are difficult to consistently obtain across different hospital17. By contrast, our model maintains predictive performance for all three outcomes using only 16 readily available preoperative variables routinely collected during preoperative evaluations. By selecting a minimal set of commonly available variables, we enhanced the model’s clinical utility, making it more feasible for implementation across diverse hospital settings without compromising predictive performance.

The interpretability of the model through SHAP analysis provides valuable clinical insights by quantifying each feature’s impact across various prediction scenarios, offering mathematically rigorous interpretations45,46. Many tree-based machine learning algorithms use SHAP-based explainability to develop prediction models for clinical outcomes such as mortality, ventilator weaning, angina, and delirium47,48,49,50,51. In this study, SHAP analysis identified the duration of anesthesia and serum albumin level as common key features consistently influencing predictions across all three outcomes. Longer duration of anesthesia likely reflects increased surgical complexity and greater physiological stress, both known to increase postoperative complication risks52,53,54, while low serum albumin indicates poor nutritional status and reduced physiological reserve, directly influences susceptibility to postoperative complications55,56,57. However, feature importance differed slightly by outcome. Serum albumin had the strongest association with in-hospital mortality, whereas serum creatinine was more predictive of AKI, and WBC count ranked relatively higher for PRF. These subtle variations likely reflect distinct underlying pathophysiological mechanisms specific to each complication. In our multitask learning model, this interpretability enables clinicians to understand how a single feature can have varying impacts on different postoperative outcomes. Such explainable models may facilitate the adoption of machine learning in clinical practice; however, the necessity of interpretability may vary depending on the clinical context58. Explainability is often essential for critical decisions, whereas it may be less critical for preliminary screening purposes. Prospective studies are required to ensure the accuracy of individual decisions when using machine learning for clinical decision-making59.

To integrate machine learning models effectively into clinical workflows, clear evidence is required that model-based decisions lead to meaningful improvements in patient outcomes60. Several recent studies have demonstrated that predictive models can enhance perioperative risk stratification and resource allocation. A previous study showed that machine learning predictions of postanesthesia hypotension improved anesthesiologist performance and facilitated more informed handoff discussions61. Similarly, incorporating perioperative factors helped identify patients at risk for unanticipated intensive care unit (ICU) admission, who had significantly higher mortality rates62. By estimating postoperative risks in an outpatient setting, our model can facilitate enhanced patient counseling and shared decision-making, enabling patients to make more informed choices about their care. Additionally, real-time risk prediction before surgery can assist clinical decision-making; for instance, patients classified as high-risk could be scheduled for direct admission to the ICU rather than the postanesthesia care unit, optimizing ICU capacity and ensuring that specialized clinicians are readily available63. However, prospective validation studies remain necessary to establish robust evidence for these benefits.

This study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design of the study introduces specific risks, including potential selection bias in the cohort construction process, the inability to account for unmeasured confounders beyond our selected preoperative features, and limitations in establishing causal relationships between our predictors and postoperative outcomes. Second, to enhance the model’s clinical utility in pre-anesthesia clinics, we intentionally did not include intraoperative variables, such as detailed surgical procedures and intraoperative data; however, this may have led to some degree of performance deterioration. Nevertheless, we chose this approach to preserve cross-institutional generalizability since intraoperative data are not uniformly available across different hospitals. However, given evidence from recent studies demonstrating that the addition of intraoperative variables improves predictive performance14,47,64, future work should investigate strategies to incorporate routinely available intraoperative variables to further enhance model accuracy and clinical applicability. Third, while the model maintained predictive performance across multiple institutions, it was developed and validated exclusively within the Korean population. Additional validation in diverse geographical regions, clinical environments, and patient demographics is needed to confirm its generalizability. Fourth, our model excluded patients with extreme BMI values (<15 or >50 kg/m²), limiting its applicability to these subgroups. Finally, although we conducted external validation on two datasets, the sample size of validation cohort B is relatively small and may have limited the statistical power of some comparisons.

Future steps include integrating the MT-GBM model into EHR systems with an intuitive risk prediction interface, followed by prospective validation across diverse clinical settings to confirm generalizability. Impact assessment on clinical workflows will occur through time-motion studies and provider feedback, ensuring the tool enhances rather than disrupts care delivery65,66. A multidisciplinary implementation strategy will include educational resources for surgical teams and a continuous feedback mechanism for model refinement based on real-world outcomes. This comprehensive approach aims to translate our research findings into a practical clinical decision support tool that meaningfully improves perioperative risk assessment and patient outcomes.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that a tree-based multitask learning model can effectively predict multiple postoperative outcomes using minimal EHR variables. The MT-GBM model maintained predictive performance across external validation datasets and provided interpretable insights, highlighting the potential of multitask learning approaches for developing generalizable clinical prediction models. Further validation in diverse geographical and clinical settings is warranted to confirm our findings, and future work includes prospective deployment and evaluation of our multitask learning model in real-time clinical workflows to assess its impact on perioperative decision-making and patient outcomes.

Methods

This multicenter retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (approval number: 2012-069-1180), Nowon Eulji Medical Center (approval number: EMCS 2023-10-002), and Korea University Guro Hospital (approval number: 2023GR0511). The requirement for written informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the TRIPOD + AI guidelines67.

Study population

Adults undergoing non-cardiac surgery at three tertiary teaching hospitals in South Korea were eligible for inclusion. Only the first surgery was included in the analysis for patients undergoing multiple surgeries during the same admission period. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) transplantation or donor surgery, (2) nephrectomy, (3) ambulatory surgery, (4) preoperative kidney dysfunction, (5) BMI > 50 or < 15 kg/m2, (6) outliers regarding laboratory results, and (7) missing in ASA physical status classification. Definitions of outliers for laboratory variables are provided in Supplementary Table S5.

Data collection and preprocessing

We collected the easily extractable variables from the EHR across all datasets. Demographic data, including age, sex, and BMI, were obtained. The ASA physical status classification was collected from preoperative anesthesia summary notes, which were recorded by anesthesiologists. Preoperative laboratory test results were also collected, including hemoglobin, WBC counts, platelets, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, albumin, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, sodium, potassium, glucose, and prothrombin time. The most recent values within 3 months before surgery were included for laboratory test results. Surgery-related variables, such as the surgical department (general surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, obstetric-urologic surgery, thoracic surgery, and other surgeries), emergency surgery status, and anesthesia duration, were also collected.

Missing values were handled using iterative imputation with 50 iterations, and the imputation model was fitted on the training dataset and subsequently applied to the test and external validation datasets. Continuous variables were standardized using min-max scaling. The primary outcomes of this study were postoperative AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality. Postoperative AKI was defined using serum creatinine levels based on the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria68 within seven postoperative days. PRF was defined as mechanical ventilation lasting longer than 48 h after surgery or reintubation within seven postoperative days11. The duration of mechanical ventilation after surgery was calculated from operating room exit until extubation. Reintubation included all instances within seven postoperative days, regardless of cause. In-hospital mortality was defined as any patient death recorded in the EHR during the same hospital admission in which the surgery occurred.

Model development

For robust model development, we implemented a stratified sampling approach based on all three outcomes simultaneously. The training-test split was performed at the patient level while maintaining the distribution of outcome combinations, ensuring a balanced representation of different risk profiles.

The derivation cohort was randomly divided into a training dataset (80%) and an internal validation dataset (20%). The internal evaluation was conducted using the separate held-out internal validation dataset (20%), which was not used during model training or hyperparameter tuning. A five-fold cross-validation approach, ensuring patient-level stratification, was applied to the training dataset during model development. The training dataset was divided into five folds, with data from the same patient consistently assigned to the same fold. Stratified sampling was performed based on the combination of three outcome variables (AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality). The size of each fold was iteratively adjusted to maintain the distribution of all outcome variables (AKI, PRF, and in-hospital mortality) across the folds.

Before model development, feature selection was conducted using the BorutaShap algorithm, which integrates the principles of the Boruta algorithm with SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values69. For each clinical outcome, we employed LightGBM as the base model with balanced class weights. The feature selection process evaluated 24 candidate features, including demographic characteristics, preoperative laboratory values, and surgery-related variables, through 2000 iterations using a 100th percentile importance threshold, which compares features against the maximum shadow feature importance to identify statistically significant predictors. The selection process was performed separately for each outcome using the entire training dataset. Based on the selection results, we created a union set comprising variables selected in at least one primary outcome, which was subsequently used as input variables for the MT-GBM model.

We developed both single-task and MT-GBM models for predicting the specified outcomes. For single-task predictions, we employed LightGBM with a binary logistic objective function for classification tasks. These models utilized gradient-boosting decision trees configured with a maximum depth of 16, a learning rate of 0.01, and 600 boosting rounds. To prevent overfitting, we applied regularization using L1 and L2 penalties (both set to 0.7) and controlled model complexity through a bagging fraction of 0.7, a feature fraction of 0.7, and a minimum of 40 data points per leaf node.

We implemented a custom MT-GBM model using a modified version of LightGBM for the multitask learning approach19, because of its ability to find optimal decision boundaries across multiple related clinical outcomes simultaneously. The MT-GBM model excels at capturing complex non-linear relationships in input variables through recursive partitioning while maintaining interpretability—a critical requirement for clinical implementation. The inherent interpretability of tree-based methods allows clinicians to understand prediction pathways through feature importance rankings, split points, and decision paths, making model predictions more transparent and trustworthy in clinical settings70. Unlike regression models that often struggle with complex interactions, our approach efficiently learns shared knowledge representation across tasks while adapting to task-specific patterns. The shared tree structures enable knowledge transfer between related outcomes, improving generalization while reducing computation overhead compared to training separate models for each outcome.

The model architecture employed a custom objective function with shared tree structures across tasks while maintaining task-specific leaf values. The model was configured with three parallel output nodes corresponding to each clinical outcome, allowing simultaneous prediction of all outcomes while preserving task-specific performance. This model was designed to leverage inter-task correlations while preserving the importance of individual tasks. We implemented binary cross-entropy loss with sigmoid activation and incorporated an adaptive weighting scheme for gradient updates. Initial weights were set as (1.0, 0.3, 0.4) for each outcome and were dynamically adjusted during training based on inter-task gradient correlations. To ensure optimization stability, weight adjustments were constrained between 0.1 and 1.0. We conducted hyperparameter optimization using random search with five-fold cross-validation to achieve optimal model performance. For each outcome, 20 iterations of random search were performed, focusing on key parameters such as maximum tree depth (range: 10–20) and number of leaves (range: 40–80). Based on these optimization experiments, the final MT-GBM model was configured with a maximum tree depth of 16, 50 leaves per tree, and a minimum of 40 samples per leaf with a custom metric frequency of 9. Other hyperparameters were fixed based on preliminary experiments: bagging and feature fractions were set at 0.7, L1 and L2 regularization at 0.7, learning rate at 0.01, and minimum child samples at 20. The training process incorporated stratification by outcome, ensuring balanced representation across all tasks, and multi-threading capabilities were utilized to enhance computation efficiency. Optimal classification thresholds for each outcome were determined using the Youden index. The best-performing hyperparameter combination identified through random search was subsequently used for final model training.

Model validation

We evaluated model performance using multiple metrics, with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) as the primary measure. Secondary metrics included the AUPRC, precision, recall, and F1 score. Performance comparisons among the MT-GBM model, single-task LightGBM, and ASA physical status classification were conducted using DeLong’s test and t-test. We employed the Spline Calibration method to assess model calibration and generated calibration plots for each outcome71. Calibration metrics, including calibration slope, intercept, and Brier score, were computed after spline recalibration. Additionally, we benchmarked the MT-GBM model against other widely used tree-based models (Random Forest and XGBoost). Model interpretability was enhanced using SHAP analysis, which provided insights into feature importance and their contributions to predictions72. Finally, we conducted decision curve analysis to evaluate the clinical utility and net benefit of the MT-GBM model compared to single-task models across various clinical decision thresholds.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed in their raw values without scaling. Depending on the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test, continuous variables are presented as means (standard deviation) or medians (inter-quartile range), while categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). Group comparisons for continuous variables were performed using the Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was employed for categorical variables.

A custom-developed program written in Python 3.10.12 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) with the scikit-learn (version: 1.5.2), LightGBM (version: 4.5.0), and SHAP (version: 0.46.0) was used to develop and validate the model.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study is not publicly available. However, the data of this study can be provided if there is a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code used in this study is not publicly available. However, the code of this study can be provided if there is a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Healey, M. A. Complications in Surgical Patients. Arch. Surg. 137, 611–618 (2002).

Downey, C. L., Bainbridge, J., Jayne, D. G. & Meads, D. M. Impact of in-hospital postoperative complications on quality of life up to 12 months after major abdominal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 110, 1206–1212 (2023).

Khan, N. A. et al. Association of postoperative complications with hospital costs and length of stay in a tertiary care center. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 21, 177–180 (2006).

Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 25, 44–56 (2019).

Yoon, H.-K., Yang, H.-L., Jung, C.-W. & Lee, H.-C. Artificial intelligence in perioperative medicine: a narrative review. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 75, 202–215 (2022).

Keane, P. A. & Topol, E. J. With an eye to AI and autonomous diagnosis. NPJ Digital Med. 1, 40 (2018).

Ramspek, C. L., Jager, K. J., Dekker, F. W., Zoccali, C. & van Diepen, M. External validation of prognostic models: what, why, how, when and where?. Clin. Kidney J. 14, 49–58 (2021).

Debray, T. P. A. et al. A new framework to enhance the interpretation of external validation studies of clinical prediction models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 279–289 (2015).

Tomašev, N. et al. A clinically applicable approach to continuous prediction of future acute kidney injury. Nature 572, 116–119 (2019).

Cao, J. et al. Generalizability of an acute kidney injury prediction model across health systems. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 1121–1129 (2022).

Yoon, H.-K. et al. Multicentre validation of a machine learning model for predicting respiratory failure after noncardiac surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 132, 1304–1314 (2024).

Lin, W.-C. et al. Prediction of multiclass surgical outcomes in glaucoma using multimodal deep learning based on free-text operative notes and structured EHR data. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 456–464 (2024).

Shickel, B. et al. Dynamic predictions of postoperative complications from explainable, uncertainty-aware, and multi-task deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 1224 (2023).

Xue, B. et al. Use of machine learning to develop and evaluate models using preoperative and intraoperative data to identify risks of postoperative complications. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e212240 (2021).

Ndirango, A. & Lee, T. Generalization in multitask deep neural classifiers: a statistical physics approach. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Sys. 32, 15862–15871 (2019).

Si, Y. & Roberts, K. Deep patient representation of clinical notes via multi-task learning for mortality prediction. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2019, 779 (2019).

Hofer, I. S., Lee, C., Gabel, E., Baldi, P. & Cannesson, M. Development and validation of a deep neural network model to predict postoperative mortality, acute kidney injury, and reintubation using a single feature set. NPJ Digital Med. 3, 58 (2020).

Zhao, X., Wang, X., Yu, F., Shang, J. & Peng, S. UniMed: multimodal multitask learning for medical predictions. In IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). 1399–1404 (IEEE, 2022).

Ying, Z., Xu, Z., Wang, W. & Meng, C. MT-GBM: a multi-task gradient boosting machine with shared decision trees. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.06239 (2022).

Wilson, F. P. Machine learning to predict acute kidney injury. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75, 965–967 (2020).

Gordon, L., Austin, P., Rudzicz, F. & Grantcharov, T. MySurgeryRisk and machine learning: a promising start to real-time clinical decision support. Ann. Surg. 269, e14–e15 (2019).

Zhu, S., Yang, R., Pan, Z., Tian, X. & Ji, H. MISDP: multi-task fusion visit interval for sequential diagnosis prediction. BMC Bioinforma. 25, 387 (2024).

Bertsimas, D. & Ma, Y. M3H: multimodal multitask machine learning for healthcare. In 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024) Workshop (2024).

Nishimoto, M. et al. External validation of a prediction model for acute kidney injury following noncardiac surgery. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2127362 (2021).

Park, S. et al. Simple postoperative AKI risk (SPARK) classification before noncardiac surgery: a prediction index development study with external validation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 30, 170–181 (2019).

Song, X. et al. Cross-site transportability of an explainable artificial intelligence model for acute kidney injury prediction. Nat. Commun. 11, 5668 (2020).

Zech, J. R. et al. Variable generalization performance of a deep learning model to detect pneumonia in chest radiographs: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 15, e1002683 (2018).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 10, e0118432 (2015).

Huang, D., Cogill, S., Hsia, R. Y., Yang, S. & Kim, D. Development and external validation of a pretrained deep learning model for the prediction of non-accidental trauma. NPJ Digital Med. 6, 131 (2023).

Martí, M. & Maki, A. A multitask deep learning model for real-time deployment in embedded systems. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1711.00146 (2017).

Vandenhende, S. et al. Multi-task learning for dense prediction tasks: a survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 3614–3633 (2022).

Harutyunyan, H., Khachatrian, H., Kale, D. C., Ver Steeg, G. & Galstyan, A. Multitask learning and benchmarking with clinical time series data. Sci. Data 6, 96 (2019).

Nissenbaum, Y. & Painsky, A. Cross-validated tree-based models for multi-target learning. Front. Artif. Intell. 7, 1302860 (2024).

Bosschieter, T. M. et al. Interpretable predictive models to understand risk factors for maternal and fetal outcomes. J. Health. Inf. Res. 8, 65–87 (2023).

Roseline, S. A. & Pearline, S. A. Exploring tree-based machine learning for multi-illness prediction. In Proc. 2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems. 1481–1486 (ICKECS 2024).

Ruder, S. An overview of multi-task learning in deep neural networks. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.05098 (2017).

Weng, W.-H., Cai, Y., Lin, A., Tan, F. & Chen, P.-H. C. Multimodal multitask representation learning for pathology biobank metadata prediction. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.07846 (2019).

Da Silva, R. P., Suphavilai, C. & Nagarajan, N. Task uncertainty loss reduce negative transfer in asymmetric multi-task feature learning (student abstract). Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35, 15867–15868 (2021).

Tsai, H. et al. Multitask learning multimodal network for chronic disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 15, 15468 (2025).

Laxmisan, A. et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int. J. Med. Inf. 76, 801–811 (2007).

Zador, Z., Landry, A., Cusimano, M. D. & Geifman, N. Multimorbidity states associated with higher mortality rates in organ dysfunction and sepsis: a data-driven analysis in critical care. Crit. Care 23, 1–11 (2019).

Xue, Y. et al. Deep state-space generative model for correlated time-to-event predictions. In Proc. 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 1552–1562 (2020).

Martin, G. P., Sperrin, M., Snell, K. I. E., Buchan, I. & Riley, R. D. Clinical prediction models to predict the risk of multiple binary outcomes: a comparison of approaches. Stat. Med. 40, 498–517 (2021).

Bihorac, A. et al. MySurgeryRisk: development and validation of a machine-learning risk algorithm for major complications and death after surgery. Ann. Surg. 269, 652–662 (2019).

Adadi, A. & Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black-box: a survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 6, 52138–52160 (2018).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 749–760 (2018).

Castela Forte, J. et al. Comparison of machine learning models including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data and mortality after cardiac surgery. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2237970 (2022).

Lin, M.-Y. et al. Explainable machine learning to predict successful weaning among patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: a retrospective cohort study in central Taiwan. Front. Med. 8, 663739 (2021).

Lee, S. W. et al. Multi-center validation of machine learning model for preoperative prediction of postoperative mortality. NPJ Digital Med. 5, 91 (2022).

Guldogan, E. et al. A proposed tree-based explainable artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of angina pectoris. Sci. Rep. 13, 22189 (2023).

Lee, D. Y. et al. Machine learning-based prediction model for postoperative delirium in non-cardiac surgery. BMC Psychiatry 23, 317 (2023).

Licker, M. et al. Risk factors of acute kidney injury according to RIFLE criteria after lung cancer surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 91, 844–850 (2011).

Attaallah, A. F., Vallejo, M. C., Elzamzamy, O. M., Mueller, M. G. & Eller, W. S. Perioperative risk factors for postoperative respiratory failure. J. Perioper. Pr. 29, 49–53 (2019).

Cheng, H. et al. Prolonged operative duration is associated with complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Surg. Res. 229, 134–144 (2018).

Gibbs, J. Preoperative serum albumin level as a predictor of operative mortality and morbidity. Arch. Surg. 134, 36 (1999).

Wiedermann, C. J., Wiedermann, W. & Joannidis, M. Hypoalbuminemia and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of observational clinical studies. Intensive Care Med. 36, 1657–1665 (2010).

Smetana, G. W., Lawrence, V. A., Cornell, J. E. & American College of, P. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 144, 581–595 (2006).

Amann, J. et al. To explain or not to explain?-Artificial intelligence explainability in clinical decision support systems. PLoS Digit. Health 1, e0000016 (2022).

Ghassemi, M., Oakden-Rayner, L. & Beam, A. L. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e745–e750 (2021).

Cabitza, F., Rasoini, R. & Gensini, G. F. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine. JAMA 318, 517–518 (2017).

Palla, K. et al. Intraoperative prediction of postanaesthesia care unit hypotension. Br. J. Anaesth. 128, 623–635 (2022).

Mestrom, E. H. et al. Prediction of postoperative patient deterioration and unanticipated intensive care unit admission using perioperative factors. PLoS ONE 18, e0286818 (2023).

Wang, L., Wu, Y., Deng, L., Tian, X. & Ma, J. Construction and validation of a risk prediction model for postoperative ICU admission in patients with colorectal cancer: clinical prediction model study. BMC Anesthesiol. 24, 222 (2024).

Rank, N. et al. Deep-learning-based real-time prediction of acute kidney injury outperforms human predictive performance. NPJ Digital Med. 3, 139 (2020).

Lopetegui, M. et al. Time motion studies in healthcare: what are we talking about?. J. Biomed. Inf. 49, 292–299 (2014).

Roos, J. et al. Time requirements for perioperative glucose management using fully closed-loop versus standard insulin therapy: a proof-of-concept time–motion study. Diabet. Med. 40, e15116 (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, q902 (2024).

Kellum, J. A. & Lameire, N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit. Care 17, 204 (2013).

Keany, E. BorutaShap: a wrapper feature selection method which combines the Boruta feature selection algorithm with Shapley values. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/record/4247618 (2020).

Banerjee, M., Reynolds, E., Andersson, H. B. & Nallamothu, B. K. Tree-based analysis: a practical approach to create clinical decision-making tools. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 12, e004879 (2019).

Van Hoorde, K., Van Huffel, S., Timmerman, D., Bourne, T. & Van Calster, B. A spline-based tool to assess and visualize the calibration of multiclass risk predictions. J. Biomed. Inf. 54, 283–293 (2015).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4765–4774 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea (No. 2022R1C1C101275313) and supported by Grant (No. 0320212080) from the SNUH Research Fund. This work was also supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00439677).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-K.Y. and H.L. contributed to the conception and design of the study. H.-K.Y., B.R.K., H.Y.K., D.K.P., H.S.K., H.-C.L., and H.L. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. H.-K.Y., B.R.K., H.Y.K. and H.L. contributed to drafting or revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to revising the paper critically for important intellectual content. H.-K.Y. and H.L. contributed to the final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.L. is an associate editor of npj Digital Medicine. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, HK., Kim, B.R., Kim, H.Y. et al. Multicenter validation of a scalable, interpretable, multitask prediction model for multiple clinical outcomes. npj Digit. Med. 8, 583 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01949-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01949-9