Abstract

Preoperative T staging of gastric cancer is critical for therapeutic stratification, yet conventional contrast-enhanced CT interpretation shows subjectivity and inconsistent reliability. We developed GTRNet, an interpretable end-to-end deep-learning framework that classifies T1–T4 from routine CT without manual segmentation or annotation. In a retrospective multicenter study of 1792 patients, CT images underwent standardized preprocessing and the largest axial tumor slice was used for training; performance was then tested in two independent external cohorts. GTRNet achieved high discrimination (AUC 0.86–0.95) and accuracy (81–85%) in internal and external tests, surpassing radiologists. Grad-CAM heatmaps localized attention to the gastric wall and serosa. Combining a deep-learning rad-score with tumor size, differentiation and Lauren subtype, we constructed a nomogram with good calibration and higher net clinical benefit than conventional approaches. This automated and interpretable pipeline may standardize CT-based staging and support preoperative decision-making and neoadjuvant-therapy selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is a major global health burden and remains among the top causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Despite advances, many patients still present with advanced disease due to limited early detection, complicating treatment2. Accurate preoperative T staging guides decisions from endoscopic resection for T1 to multimodal therapy for T3/T4 disease3,4,5. Accurate T staging thus enables more tailored interventions, potentially improving survival and reducing unnecessary morbidity.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the standard for preoperative evaluation, but conventional interpretation has known limitations. The overall accuracy of CT-based gastric T staging is often reported around 65–75%, with particular difficulty in discriminating T2 from T3 tumors and in recognizing subtle serosal invasion6. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can visualize distinct layers of the gastric wall, thereby helping to distinguish T1 disease from deeper invasion; however, its accuracy declines in advanced tumors and proximal lesions, and the technique is highly operator-dependent7,8. Other adjunct imaging methods, including double contrast-enhanced ultrasound, may improve diagnostic performance in experienced hands but are not universally available. Consequently, there is a clear clinical need for new tools to enhance the objectivity and accuracy of T staging.

Artificial intelligence (AI), especially deep learning using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has emerged as a powerful approach to analyzing medical images9. CNNs can learn multi-scale textural and morphological features from large volumes of data, surpassing traditional machine learning or radiologist interpretation in tasks such as tumor segmentation, disease classification, and prognostic modeling. Notably, deep learning models have achieved high diagnostic performance in areas like breast lesion classification on MRI, prediction of EGFR mutations in lung cancer using CT, and detection of peritoneal carcinomatosis9,10,11. In gastric cancer imaging research, many published efforts have either focused on binary distinctions (e.g., early vs. advanced stages) or relied on radiomics approaches requiring manual tumor segmentation12,13. Manual segmentation can be time-consuming and subject to significant inter-observer variability, which hampers clinical implementation at scale.

To address these gaps, we developed an end-to-end deep learning system—termed Gastric Cancer T-stage ResNet Network (GTRNet)—that provides a fully automated, four-class T stage classification (T1, T2, T3, T4) from standard portal venous phase CT scans. Unlike many prior methods requiring manual segmentation, our model processes a single axial slice of the largest tumor cross-section, using a modified ResNet-152 backbone to extract relevant features. We hypothesize that GTRNet will improve staging accuracy, reduce reliance on operator skill, and demonstrate generalizability across multiple institutions.

In this study, we collected data from three tertiary centers, resulting in a total of 1792 patients with pathologically confirmed gastric adenocarcinoma. We trained and tested GTRNet using internal datasets and performed external testing in two independent cohorts. We additionally designed a comparative reader study in one external cohort to compare the model’s performance against expert gastrointestinal radiologists. To promote transparency, we incorporated Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) to highlight image regions that drive the network’s predictions, providing clinicians with intuitive saliency maps that localize tumor invasion. Finally, we integrated the network output into a combined nomogram, incorporating clinical and pathologic factors known to correlate with disease aggressiveness, thus creating a more holistic preoperative risk stratification tool.

Below, we detail our methodology, results, and clinical implications, focusing on three goals: (1) evaluating GTRNet’s staging accuracy, (2) demonstrating interpretability, and (3) assessing its impact on neoadjuvant therapy decisions.

Results

Study design and patient selection

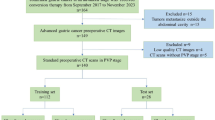

This retrospective, multicentre study analyzed patients who underwent curative‑intent resection for gastric adenocarcinoma between January 2015 and December 2021 at three tertiary hospitals. Eligible cases met four criteria: (i) histologically confirmed T1–T4 gastric cancer (AJCC 8th edition)14; (ii) pre‑operative contrast‑enhanced abdominal CT available; (iii) no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy; and (iv) diagnostic image quality without severe artefacts. We excluded patients with incomplete records, non‑diagnostic CT, or distant metastasis precluding curative surgery. The screening process is summarized in Fig. 1. Ultimately, 1792 patients were allocated to a training cohort (n = 953) and an internal test cohort (n = 239) from Hospital A, plus two external test cohorts (n = 360, Hospital B; n = 240, Hospital C).

Study population

In the training set, cases meeting the inclusion criteria were distributed in a relatively balanced manner across T1–T4 stages to minimize potential data bias. The mean age across all cohorts was approximately 62 years, with approximately 70–73% of patients being female. Variations in the distribution of tumor locations and histologic subtypes were observed across centers (e.g., proximal tumors accounted for 9.6% in the internal test set and 25.4% in external test set 2). However, no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics were identified. Baseline demographic and clinicopathologic variables—including age, sex, tumor location, size, Lauren classification, differentiation status, serum tumor marker levels, and PD-L1 expression—were extracted from electronic health records and are presented in Table 1.

In the internal test and external cohorts, GTRNet achieved high discriminatory performance for T staging. The internal test accuracy was 89.9%, and external test accuracies were around 87–94%. AUCs ranged from 0.97 internally to 0.91–0.95 in the external sets. Stage-specific sensitivities were robust (e.g., 75–95% across T1–T4 in internal testing) and specificities were 83–98%. The model’s ROC curves and confusion matrices for each cohort are shown in Fig. 2, and detailed performance metrics are provided in Table 2.

Evaluation metrics and statistical analysis

All reporting complies with the CLAIM 2024 checklist for AI studies in medical imaging. Model performance was evaluated in the internal test set and two external validation cohorts using standard metrics. For multi-class classification, we calculated one-vs-rest ROC curves and macro-average AUCs, and we derived confusion matrices along with class-specific sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). These results are presented in Fig. 2. All evaluation metrics were statistically analyzed based on the patients’ final classification decisions. During the external validation phase, the prediction results of the three key slices were integrated using the majority-voting method. This approach was adopted to ensure a high degree of consistency between the evaluation results and clinical practice.

The performance of GTRNet and radiologists in the prediction of clinical T-staging of gastric cancer

We conducted a comparison of the performance between the GTRNet model and radiologists from multiple centers in predicting the clinical T-stage of gastric cancer. As presented in Supplementary Table 1, the GTRNet model demonstrated a marked superiority over the independent diagnoses of radiologists in terms of both overall accuracy (92.8% in Hospital A, 93.6% in Hospital B, and 86.7% in Hospital C) and consistency with pathological findings. The accuracies of radiologists’ independent diagnoses were 58.4%, 59.7%, and 55.3%, respectively, all of which showed a highly significant difference (p < 0.001). With the aid of the GTRNet model, the overall staging capabilities of radiologists were substantially enhanced. The diagnostic accuracy of radiologists increased to 85.4–91.5%, approaching the level of the model’s independent diagnosis. In the evaluation of pathological consistency, the weighted Kappa value between the GTRNet model and the pathological T-stage ranged from 0.87 to 0.91, which was significantly higher than that of radiologists’ sole interpretation, which ranged from 0.41 to 0.45. When assisted by artificial intelligence (AI), the Kappa value of radiologists’ interpretation rose to 0.83–0.88. This indicates that AI-assisted interpretation can significantly reduce staging discrepancies (p < 0.001). During the evaluation of early-stage gastric cancer (T1/T2), the GTRNet model exhibited an extremely high level of sensitivity, registering 98.5–99.0% for T1 and 93.0–97.8% for T2. These values were significantly higher than those of radiologists, which were 65.0–71.0% for T1 and 55.3–60.2% for T2. Such results hold significant implications for clinicians in formulating individualized treatment strategies for patients with early-stage gastric cancer. Regarding advanced-stage gastric cancer (T3/T4), the GTRNet model also demonstrated favorable sensitivity, with values of 83.3% for T3 and 81.7–93.3% for T4. These findings suggest that the model has the potential to optimize treatment decisions and minimize unnecessary interventions in practical clinical settings.

Grad-CAM heatmap visualization

To enhance the clinical interpretability of the GTRNet attention mechanism, we employed Grad-CAM heatmaps to visualize the regions of interest (ROIs) that the model prioritizes. As illustrated in Fig. 3, warm colors such as red and yellow indicate higher model attention, with increasing color intensity corresponding to greater focus; conversely, cooler colors such as blue and green represent lower attention, with darker shades indicating reduced focus. When compared with the ROIs (red-filled areas) manually annotated by radiologists, the attention distribution generated by GTRNet demonstrated a high degree of spatial overlap with expert annotations. For example, in T1-stage lesions, the heatmap predominantly highlighted the inner layers of the gastric wall, indicating that the model effectively captured imaging features associated with superficial submucosal infiltration. In contrast, for T4-stage lesions, the model’s attention extended beyond the thickened gastric wall to include the interface between the tumor and adjacent organs, suggesting its ability to detect radiological signs of tumor invasion into surrounding structures. These findings further confirm that GTRNet possesses strong interpretability and clinical relevance in the T staging of gastric cancer.

To further quantify the spatial alignment between the model’s attention regions and the actual tumor locations, we binarized the Grad-CAM heatmaps and computed the Dice similarity coefficient by comparing them with the gold-standard masks manually segmented by radiologists. The Dice coefficients across different T stages were as follows: 0.56 for T1, 0.59 for T2, 0.60 for T3, and 0.63 for T4, indicating moderate to substantial spatial overlap between the model’s attention maps and the ground truth lesion areas. These findings suggest that the attention mechanism of GTRNet does not erroneously focus on image artifacts or non-pathological regions, but rather accurately identifies key anatomical structures that are critical for T staging. Furthermore, in Supplementary Fig. 1, we illustrate several representative misclassified cases to investigate potential error patterns under conditions of ambiguous staging boundaries or complex anatomical configurations. This analysis provides insights that may guide future improvements in model performance.

Nomogram integration and clinical utility

While GTRNet alone performed well, we sought to incorporate clinical and histologic factors to further refine T-stage prediction. After extracting deep features from the penultimate network layer, we computed a continuous Rad-score for each patient. We then built an ordinal logistic-regression model that combined the Rad-score with tumor size (≥ 5 cm), poor differentiation, and diffuse Lauren type. All four predictors contributed significantly to the model (each P < 0.001 in multivariable analysis). The corresponding regression coefficients are listed in Table 3, and inclusion of the Rad-score significantly improved model fit.

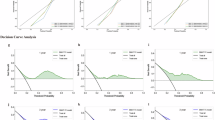

The resulting nomogram (Fig. 4) provides an intuitive tool for clinicians: each predictor is allocated points, and the total score maps to estimated probabilities of T1, T2, T3, or T4 disease. Calibration was good across all cohorts, with Hosmer–Lemeshow tests showing no significant lack of fit (P > 0.05). In order to evaluate the potential applied value of the model in clinical decision-making, we employed decision curve analysis (DCA) to compare the net benefits of the AI model and EUS staging in facilitating the identification of high-risk patients. Taking the test set as a case in point, within most of the clinically justifiable threshold probability ranges, the AI model exhibited a higher net benefit (as shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2). More specifically, the over-treatment rate of the AI model was 2.09%, which was significantly lower than the 12.97% of EUS. The under-treatment rate was 2.51%, also markedly lower than the 17.57% of EUS. Furthermore, the number needed to treat (NNT) for the AI model was 2.19, which was notably superior to the 5.09 of EUS. This indicates that while enhancing clinical benefits, the AI model can effectively minimize unnecessary interventions, thereby demonstrating a higher level of clinical utility.

a–d Calibration curves compare predicted and observed probabilities (dashed 45 line = perfect fit). e–h Decision curve analysis (DCA) comparing the net clinical benefit of the AI prediction model versus EUS staging across different datasets. The curves illustrate the net benefit of intervention across a threshold probability range of 0 to 0.8.

Discussion

Compared with traditional CT interpretation and earlier AI or radiomics work, our end‑to‑end network offers three incremental advantages. Historically, CT has achieved only moderate accuracy (≈65–75%) for gastric-cancer T staging, particularly when differentiating borderline invasions and across readers6. Endoscopic ultrasound can visualize individual gastric wall layers and improves detection of early (T1) tumors, yet performance drops in proximal or bulky lesions and remains operator-dependent7,8. Dual-energy CT and MRI have recently shown incremental value, but require specialized scanners and are not universally available15. Several radiomics or AI studies have focused on binary “early vs advanced” tasks or have relied on labor-intensive manual segmentation15,16,17.

Secondly, in recent years, multiple studies have explored the application of deep learning techniques to the T staging of gastric cancer (see Supplementary Table 3 for details). For example, Tao et al. (2024) developed a vision Transformer model based on CT imaging, which achieved an accuracy of 75.7% on an external test set. The model’s performance was further enhanced through the integration of radiomics features. However, this study was limited to a binary classification task distinguishing between T1 and T4 stages and required manual tumor segmentation, which constrained its clinical scalability. Similarly, Chen et al., Guan et al., and Zeng et al. proposed various deep learning models based on CT or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) images. While these models demonstrated high AUC values in early gastric cancer detection, most failed to perform a complete four-category classification across T1–T4 stages. Moreover, they generally lacked integration with clinical workflows and multi-center validation18,19,20. Therefore, there is a pressing need for an AI model that is independent of manual annotation, capable of multi-class T staging, and seamlessly integrable into clinical pipelines to enhance its real-world translational potential. In contrast, GTRNet was developed using over 1700 retrospective cases from three tertiary hospitals and incorporated 270 prospective samples to simulate real-world clinical procedures. This approach demonstrates superior generalization and potential for clinical deployment. The proposed model eliminates the need for laborious manual segmentation and supports a full four-class T staging (T1–T4), effectively addressing the clinical demand for precise differentiation between borderline T2 and T3 stages. Furthermore, successful multi-center AI implementations in other medical domains—such as breast MRI9, lung cancer EGFR status prediction10, and peritoneal metastasis detection in colorectal cancer11—demonstrate that models combining large-scale heterogeneous data with modern convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures consistently outperform traditional radiomics approaches in multi-task settings. These precedents further validate the feasibility and clinical relevance of applying the GTRNet framework to gastric cancer T staging.

These performance gains translate into several clinically relevant implications for neoadjuvant decision‑making and surgical planning. Current Western and Asian guidelines emphasize accurate discrimination between T2 and ≥T3 disease because perioperative chemotherapy improves survival in locally advanced cases. Understaging may deprive patients of effective therapy, whereas overstaging exposes early tumors to unnecessary toxicity. GTRNet’s high sensitivity for T4 and its integration into a nomogram with tumor size and histology provide an intuitive, probability-based aid to select candidates for neoadjuvant treatment or direct surgery. In practice, the model could flag CT-occult serosal invasion that radiologists frequently miss, or reassure surgeons when a lesion is very likely limited to T1/T2.

Interpretable heat‑maps further strengthen clinician trust by showing that the model attends to the same perigastric margins that experts scrutinize. Adoption of AI hinges on transparent reasoning. GradCAM visualizations localized attention to the gastric wall and perigastric fat—areas radiologists inspect for transmural spread—thereby bridging the “black box” gap14. Such heatmaps can also serve as training feedback for junior readers, fostering human–machine synergy.

Ethical considerations. The algorithm may propagate scanner‑ or cohort‑specific bias; therefore, continuous audit, domain‑shift monitoring, and patient informed‑consent procedures will accompany any prospective deployment.

Notwithstanding these findings, this study is not without certain limitations. First and foremost, for the sake of streamlining the clinical workflow, we grouped the T4a and T4b stages together for analysis. Future research that further refines this categorization could potentially offer more accurate clinical guidance for surgical margin assessment and strategies regarding combined organ resection. It is important to note that among the T4 cases incorporated in this study, some were T4b patients (such as those with tumors invading adjacent organs), yet advanced T4b cases with peritoneal metastasis or other conditions precluding radical surgery were not included. Consequently, this model was predominantly developed using a cohort of surgically treatable patients. As a result, it may face certain limitations in generalizing to some inoperable advanced cases. Future investigations should incorporate a greater number of real-world inoperable T4b samples to enhance the model’s applicability and practical utility within complex clinical settings. Secondly, all external validation cohorts were sourced from the Chinese population. Thus, there is a pressing need to conduct cross-regional validation among international populations with diverse body characteristics and scanning protocols15 to assess the model’s broad applicability. Thirdly, this study did not encompass the N and M staging aspects. Existing research has demonstrated that multimodal models integrating imaging, pathological, and multi-omics data have exhibited promising potential in predicting lymph node status21, tumor mutational burden22,23, and EB virus subtypes24. In the future, GTRNet could be extended into a unified analytical framework covering the entire TNM staging system, thereby enabling more comprehensive auxiliary diagnosis for gastric cancer staging. Finally, despite implementing a variety of data augmentation strategies12 and an adaptive early-stopping mechanism13 to mitigate the risk of overfitting, it is essential to conduct prospective deployment research within multi-center, real-world clinical environments to comprehensively evaluate the model’s stability and clinical viability16.

Looking forward, several technical and translational extensions could broaden the model’s utility. Research directions include: (i) transformer or 3D CNN architectures to leverage contextual slices; (ii) spiking deep residual networks that emulate neuromorphic efficiency and may reduce inference latency on edge devices25; (iii) panomic integration—combining imaging, genomics, and histopathology—to build comprehensive, patient-specific digital twins. Multicentre benchmark challenges would accelerate reproducibility and standardize evaluation metrics.

In summary, an end‑to‑end deep‑learning pipeline accurately discriminates T1–T4 disease and outperforms radiologists across centres. An interpretable deep learning framework (GTRNet) achieved robust, external validated performance for four-class gastric cancer T staging on routine CT, outperforming expert radiologists and preserving transparency via heatmap visualization. Coupled with key clinicopathologic variables, the model underpins a nomogram that can refine preoperative decision-making and optimize allocation of neoadjuvant therapy. Prospective trials and broader geographic validation are warranted to translate these findings into global clinical practice.

Methods

CT imaging protocol and image preprocessing

Patients from three hospitals underwent standardized abdominal contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) scans during the portal venous phase, with the administration of 1.5 mL/kg contrast agent following a protocol of fasting and water intake to achieve gastric distension. Although the institutional scanners and acquisition parameters differed (Table 4), all CT images were subjected to rigorous preprocessing to reduce heterogeneity. Preprocessing steps included resampling to isotropic 1 × 1 × 1 mm³ voxel spacing, intensity normalization within a standardized Hounsfield Unit (HU) range (−1024 to 1024), and application of an abdominal window setting (WL 50, WW 350). Further corrections included N4 bias-field correction and Z-score normalization. For the purposes of model training and internal testing, a single representative axial tumor slice per patient was selected by an expert radiologist. This slice was resampled to a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels and standardized using z-score normalization (mean subtraction and division by standard deviation), without requiring manual region-of-interest segmentation, thereby enabling an end-to-end workflow. To enhance model robustness and generalizability, data augmentation—including random rotations, flips, and intensity adjustments—was implemented during the training phase.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute (KY20240503, 15 Jan 2024), Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (2024PS184K, 22 Jan 2024), and Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (2024‑ZJ‑GC‑009, 3 Feb 2024). All procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant national regulations. Written informed consent was waived because only de‑identified, routinely acquired imaging and clinical data were analyzed.

In the external test set, we included the slices immediately above and below the key slice of each case’s images, along with the key slice itself, resulting in a total of three images for predictive analysis. The final case-level prediction outcomes were obtained by aggregating the model outputs of these three slices through a majority-voting strategy. This approach aimed to mitigate the randomness that could be associated with single-slice predictions. During the training process, standard data augmentation techniques, such as random flipping, rotation, scaling, and intensity perturbation, were implemented to enhance the model’s generalization capabilities12. Additionally, an adaptive early-stopping strategy was adopted. This strategy involved monitoring the loss of the validation set to dynamically adjust the training progress, thereby reducing the risk of overfitting13.

A comparative analysis of the performance of GTRNet and radiologists in predicting gastric cancer T staging

To delineate the performance of the GTRNet model in predicting the T-staging of gastric cancer, we recruited radiologists from Liaoning Cancer Hospital, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, and Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. Their predictive outcomes were then juxtaposed with those of the GTRNet model. Three radiologists specializing in digestive system radiology, each with 8–15 years of experience, were invited from each hospital. Under single-blind conditions, they independently determined the clinical T-staging (cT1–cT4) of gastric cancer solely based on enhanced CT images. The study was structured into two distinct phases, with the pathological T-staging (pT) established as the gold standard. In the initial phase, the radiologists completed the staging assessment independently. In the subsequent phase, one month later, the radiologists repeated the staging prediction with the aid of the GTRNet model. Metrics such as the accuracy rate, weighted Kappa value, and sensitivity for each stage were meticulously calculated and analyzed. Additionally, the number of cases with over-staging and under-staging were tallied to assess the potential clinical implications. Regarding the sample selection, at Hospital A (Liaoning Cancer Hospital), radiologists selected 270 cases from the 1192 samples within the center. For each of the two predictions, 50% of non-overlapping samples were utilized for evaluation. At the other two hospitals (Hospital B and C), 50% of the total samples from each respective center, with no overlap between the two sets of samples used in the two predictions, were employed. Detailed metrics are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Deep learning model: GTRNet

We constructed the GTRNet architecture by modifying the ResNet-152 backbone, a deep residual network known for strong feature extraction (Fig. 6). Our modifications aimed to enhance the model’s ability to capture multi-scale features relevant to T staging. Specifically, we introduced parallel max-pooling and center-cropping streams in the early network layers, allowing the network to focus on both local tumor detail and wider contextual information around the gastric wall. Transfer learning was applied by initializing ResNet-152 weights from ImageNet pretraining, followed by replacing the final dense layer with four softmax outputs corresponding to T1, T2, T3, T4. We trained with Adam (learning rate ~1 × 10−4), a mini-batch of 32, and categorical cross-entropy, stopping early if validation performance plateaued for 10 epochs. All training was performed on an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, allowing relatively fast convergence.

A Portal-venous CT slice showing the largest tumor cross-section. B GTRNet architecture: modified ResNet-152 with parallel max-pool and center-crop branches. C End-to-end workflow linking the deep-learning Radscore to a clinical–radiomic nomogram. D Summary of model evaluation metrics, including ROC curve, confusion matrix, calibration curve, and decision curve analysis (DCA). In the DCA plot, the y-axis represents the net benefit and the x-axis represents the threshold probability, with comparisons among the treat-all, treat-none, and EUS-prediction strategies.

Analyses were performed in Python 3.10.13 (PyTorch 2.2.0, Torchvision 0.17, NumPy 1.26, SciPy 1.11, scikit‑learn 1.3; Grad‑CAM via pytorch‑grad‑cam 1.4.8); R 4.3.1 and IBM SPSS 26.0 were used for statistical analyses; ROI overlays were created in ITK‑SNAP 4.0.1. Full code and environment files are provided in the “Code availability” statement.

Data availability

Most of the de-identified data supporting this study’s findings are included within the article and its supplementary information. The original CT imaging datasets are not publicly available to protect patient confidentiality and comply with institutional policies. Additional de-identified data may be requested from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request, subject to ethics approval and data-sharing agreements.

Code availability

The complete source code, trained model weights and a representative sample dataset are openly available on GitHub (https://github.com/18846068128/AI_CT_GastricCancer_TStaging2025) under an MIT license. A permanent snapshot of version v2.0 has been archived on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15543822).

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Smyth, E. C. et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 1005–1020 (2022).

Ajani, J. A. et al. Gastric cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 14, 1286–1312 (2016).

Cunningham, D. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 355, 11–20 (2006).

Al-Batran, S. E. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FLOT versus ECF/ECX in patients with resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): a multicentre, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet 393, 1948–1957 (2019).

Ahn, H. S. et al. Evaluation of the seventh AJCC/UICC TNM staging system for gastric cancer: results from a single high-volume institution in Korea. Dig. Surg. 30, 142–149 (2013).

Nan, M., Ye, W., Liu, Y. & Zhang, Z. Diagnostic accuracy of gastric filling ultrasonography in preoperative invasion depth (T stage) of gastric cancer: meta-analysis. Medicine 101, e31066 (2022).

Kouzu, K. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of T stage of gastric cancer from the viewpoint of application of laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 8, 773–778 (2018).

Truhn, D. et al. Radiomic versus convolutional neural networks analysis for classification of contrast-enhancing lesions at multiparametric breast MRI. Radiology 290, 290–297 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Mining whole-lung information by artificial intelligence for predicting EGFR genotype and targeted therapy response in lung cancer: a multicohort study. Lancet Digit Health 4, e309–e319 (2022).

Yuan, Z. et al. Development and validation of an image-based deep learning algorithm for detection of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis in colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 275, e645–e651 (2022).

Garcea, F., Serra, A., Lamberti, F. & Morra, L. Data augmentation for medical imaging: a systematic literature review. Comput Biol. Med 152, 106391 (2023).

Al-Rimy, B. A. S. et al. An adaptive early stopping technique for DenseNet169-based knee osteoarthritis detection model. Diagnostics 13, 1903 (2023).

Dovletov, G. et al. Grad-CAM guided U-Net for MRI-based pseudo-CT synthesis. In Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc (EMBC) (2022).

Li, Q. et al. MRI versus dual-energy CT in local-regional staging of gastric cancer. Radiology 312, e232387 (2024).

Tao, J. et al. Development and validation of a computed tomography-based model for noninvasive prediction of the T stage in gastric cancer: multicenter retrospective study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e56851 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. CT-based radiomics nomogram for differentiating gastric hepatoid adenocarcinoma from gastric adenocarcinoma: a multicentre study. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 205–214 (2023).

Chen, T. H. et al. Artificial intelligence model for a distinction between early-stage gastric cancer invasive depth T1a and T1b. J. Cancer 15, 3085–3094 (2024).

Guan, X., Lu, N. & Zhang, J. Accurate preoperative staging and HER2 status prediction of gastric cancer by the deep learning system based on enhanced computed tomography. Front. Oncol. 12, 950185 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Development and validation of an AI-based multimodal model for pathological staging of gastric cancer using CT and endoscopic images. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e56851 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. A radio-pathologic integrated model for prediction of lymph node metastasis stage in patients with gastric cancer. Abdom. Radio. 48, 3332–3342 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Predicting gastric cancer tumor mutational burden from histopathological images using multimodal deep learning. Brief. Funct. Genomics 23, 228–238 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Predicting gastric cancer outcome from resected lymph node histopathology images using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 1637 (2021).

Zheng, X. et al. A deep learning model and human–machine fusion for prediction of EBV-associated gastric cancer from histopathology. Nat. Commun. 13, 2790 (2022).

Hu, Y., Tang, H. & Pan, G. Spiking deep residual networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn Syst. 34, 5200–5205 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Departments of Radiology and Pathology at Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, and Zhejiang Cancer Hospital for providing de-identified imaging and clinical data. We thank OneKey AI Co., Ltd. for its technical assistance with DICOM image processing and standardization. This research was supported by the Liaoning Province Science and Technology Joint Plan (2023JH2/101700195)., the Liaoning Province Medical-Engineering Interdisciplinary Research Fund (No. LD202232), the Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2024-MS-269), and the Shenyang Youth Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Program (No. RC210462).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. and H.W. contributed equally and share first authorship. G.Z. conceived and designed the study, coordinated multicentre data collection, and curated the final dataset. H.W. implemented the deep-learning model, performed training and statistical analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript. X.C. and Z.Y. optimized the ResNet-152 backbone, built the multi-class classification pipeline, and generated Grad-CAM visualizations. J.Z. supervised methodology, verified analytical accuracy, and critically revised the manuscript. X.X. and F.G. provided intellectual review and validated the manuscript’s logical coherence. Z.X.J. assisted with statistical analysis and manuscript editing. F.L., H.L., Y.B., and J.W. harmonized imaging protocols across centres and integrated clinicopathological data. X.Q. and Y.L. standardized CT acquisition parameters and performed image preprocessing. D.Z. and Y.Q.Z. coordinated external data transfer, ensured data integrity, and managed ethics approvals. X.Z. and Z.Z. offered critical clinicopathologic insights and guided external validation experiments. Y.Z. secured funding, provided computational infrastructure, supervised all phases of the study, and serves as guarantor of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, G., Wang, H., Chai, X. et al. Interpretable deep learning for multicenter gastric cancer T staging from CT images. npj Digit. Med. 9, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02002-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02002-5