Abstract

Flexible ureteroscopy (FURS) is a minimally invasive, standard treatment for kidney stones. This study presents the development and clinical validation of an artificial intelligence system during FURS (AiFURS) for real-time detection, classification, and measurement of stones. Using 6170 annotated ureteroscopy video frames representing 11,870 labeled stones, the AiFURS was trained to identify stone type, size, and number. Ex vivo validation across 191 groups predicted stone counts precisely (r > 0.9) in 300 samples. Size predictions for stones >2 mm (n = 100, r = 0.81) correlated with gold-standard caliper measurements. In vivo and external validation of 100 and 80 cases, respectively, demonstrated diagnostic accuracy (92.2–95.3% and 86.8–92.2%, respectively) for patient-level stone type prediction, outperforming expert surgeons. Logistic regression further identified the proportion of residual fragments (RFs) > 2 mm, measured during the final minutes of FURS, as an independent predictor of reoperation. AiFURS offers a novel solution to enhance surgical accuracy, reduce complications, and improve outcomes in endourology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kidney stone disease is a major global health issue, affecting millions of individuals and often requiring surgical intervention1. Kidney stones are solid deposits formed when minerals and salts, such as calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid, crystallize within the kidneys2,3. These stones can cause severe pain and urinary tract infections (UTIs) and, if left untreated, lead to significant complications, including kidney damage and increased morbidity4. The rising prevalence of kidney stones, coupled with risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, has highlighted the need for effective surgical treatments5,6. Flexible ureteroscopy (FURS) has become a key treatment modality for kidney stones, offering benefits such as minimal invasiveness, reduced patient morbidity, faster recovery times, and lower complication rates7. However, successful FURS depends on the surgeon’s ability to accurately identify, classify, and remove stone fragments, a process complicated by anatomical variations and stone characteristics8. Traditional methods of stone detection during FURS rely heavily on surgeons’ visual assessments, which are subjective and prone to variability9. This dependence can lead to inconsistent outcomes, with residual fragments (RFs) contributing to recurrent stones, UTIs, and the need for additional surgeries10. The stone-free rate (SFR) and prevalence of post-operative complications are vital metrics for evaluating the success of ureteroscopic lithotripsy. According to the standard definition of SFR, the goal of FURS is to pulverize stones to ≤2 mm in size11. However, achieving a high SFR primarily depends on the surgeon’s skill and the accuracy of stone detection12,13. This variability underscores the need for a more objective and reliable tool to help surgeons achieve complete stone removal14.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision (CV) offer promising solutions to these surgical challenges15,16,17,18,19,20,21. AI-assisted systems using deep learning algorithms improve medical image segmentation and provide real-time support for detecting and analyzing kidney stones22,23,24, enhancing surgical precision while reducing operator variability. In recent years, several convolutional neural network (CNN)-based methods have achieved excellent performance when identifying stone composition from endoscopic images25,26,27,28,29,30. However, existing approaches cannot provide real-time information on the composition, size, or number of stones to help surgeons assess surgical progress and outcomes. Thus, development of an integrated, real-time system capable of multi-dimensional stone analysis during FURS is essential.

To this end, the present study developed and validated an artificial intelligence flexible ureteroscopy system (AiFURS) using object detection and multi-object tracking algorithm for real-time detection, classification, and measurement of stones during FURS, to assist intra-operative decision-making and reduce post-operative complications.

Results

Study design

An overview of this study is provided in Fig. 1. Our aim was to develop a real-time AiFURS for detecting kidney stones during FURS. In this system, we employed the YOLOv11-N31 and BoT-SORT tracking32 deep learning algorithms on a total of 6,170 annotated frames from 30 surgical videos. The performance of AiFURS was evaluated systematically via: (1) ex vivo validation included 300 stone samples, comparing stone-size predictions with gold-standard caliper measurements, and 191 groups of stones, assessing predicted stone numbers against actual counts; (2) in vivo clinical validation on 100 cases assessing stone classification, size, and count; (3) external validation on 80 cases; and (4) comparison with expert urologists to assess accuracy in stone classification.

a Ureteroscopic lithotripsy procedure: perform a pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan to evaluate stone characteristics, proceed with FURS using a holmium laser, conduct post-operative imaging to assess RF size and perform spectrophotometric analysis of stone composition, and assess prognosis and treatment. b Develop AiFURS; the model development dataset consisted of data from 30 patients who underwent ureteroscopic lithotripsy. From their surgical videos, 6170 ureteroscopy video frames were extracted, annotated, and reviewed by expert urologists. The dataset was divided into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) subsets. The AiFURS employed the YOLOv11-N and BoT-SORT models, achieving real-time detection. c System evaluation: the performance of the AiFURS was evaluated via ex vivo clinical validation, in vivo clinical validation (100 cases), external validation (80 cases), AI-urologist comparisons, and real-time inference. Created using BioRender. Liang, H. (2025) (https://BioRender.com/3qbaz66) and the written permission given to use and adapt it. Abbreviations: AiFURS artificial intelligence flexible ureteroscopy system, YOLO You Only Look Once.

Model validation

We evaluated the performance of our proposed AiFURS and compared it to state-of-the-art lightweight (N-scale and S-scale) real-time detectors, including You Only Look Once (YOLO)-based detectors (YOLOv8–v12), transformer-based detectors (RT-DETR and D-FINE). The performance results are shown in Table 1. When compared to N-scale and T-scale models, the AiFURS achieved a mean average precision at 50% intersection-over-union (IOU; mAP@50) of 0.933, surpassing D-FINE-N (0.910), YOLOv8-N (0.926), YOLOv9-T (0.924), YOLOv10-N (0.913), and YOLOv12-N (0.927) by 2.3%, 0.7%, 0.9%, 2.0%, and 0.6%, respectively, while requiring less or similar computational cost (6.5 giga floating-point operations [FLOPs]), evaluating fewer or a similar number of parameters (2.6 million), and having a fast latency speed of 1.5 ms per image. When compared to S-scale models, the AiFURS outperformed RT-DETRv2-S (0.925), RT-DETR-S (0.919), D-FINE-S (0.931), YOLOv8-S (0.929), YOLOv9-S (0.927), YOLOv10-S (0.928), and YOLOv12-S (0.932) by 0.8%, 1.4%, 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.5%, and 0.1%, respectively. Although YOLOv11-S matched the AiFURS with respect to mAP@50 and slightly exceeded it with respect to mean average precision at 50–95% IOU (mAP@50–95) and mean average precision at 75% IOU (mAP@75), the AiFURS’s lower latency and computations made it the optimal choice for satisfying the stringent real-time performance and accuracy requirements of stone recognition.

As shown in Fig. 2, the predicted boxes were compared to ground-truth labels and overlaid with gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) heatmaps to highlight the regions driving each detection event. The AiFURS successfully detected and classified kidney stones, including calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid stones, with high consistency between labeled and predicted bounding boxes. Grad-CAM heatmaps provided transparent and interpretable visual explanations of the model’s decision-making process.

Ex vivo clinical validation

After FURS, extracted kidney stones were collected using a stone retrieval basket. Stones of varying types and counts were then randomly placed at a fixed visual distance (one fiber distance from the lens) under the ureteroscope to simulate the surgical procedure and enable video recording (Fig. 3a, b).

a Examples of the AiFURS’s stone count detection performance. b Examples of the AiFURS’s stone size detection performance. c–j Correlation (top row) and Bland–Altman (bottom row) plots depict the concordance between the AiFURS’s predicted outcomes and manual reference measurements for the quantification and size evaluation of kidney stones under controlled ex vivo conditions. In the Bland–Altman plots, the black dashed lines at both ends represent the limits of agreement (LoAs), while the red dashed line represents the bias. Stone number c Spearman’s r = 0.9698, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.9597–0.9774, p < 0.0001 and g bias = −0.1623, 95% LoA: -0.8869–0.5623. Stones with a maximum diameter >2 mm d Spearman’s r = 0.8134, 95% CI: 0.7316–0.8721, p < 0.0001 and h bias = −0.0011, 95% LoA: −0.7814–0.7792. Stones with a maximum diameter of 1–2 mm e Spearman’s r = 0.3764, 95% CI: 0.1887–0.5376, p = 0.0001 and i bias = 0.0272, 95% LoA: −0.5108–0.5652. Stones with a maximum diameter <1 mm f Spearman’s r = 0.4728, 95% CI: 0.2994–0.6160, p < 0.0001 and j bias = 0.0817, 95% LoA: −0.3474–0.5108. Abbreviations: AiFURS artificial intelligence flexible ureteroscopy system.

When the actual and AiFURS-generated counts across 191 groups with different stone numbers were compared, Spearman’s correlation analysis showed a strong association (r > 0.9, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3c). Bland–Altman analysis indicated an average difference of −0.1623 (95% limit of agreement [LoA]: −0.8869–0.5623; Fig. 3g).

Furthermore, the AiFURS was used to estimate the sizes of 300 stone samples (100 each with maximum diameters >2 mm, 1–2 mm, and <1 mm); these measurements were then compared to gold-standard caliper measurements. The resulting correlations were fair for stones with a maximum diameter >2 mm (r = 0.8134, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3d) yet weak for stones with a maximum diameter of 1–2 mm (r = 0.3764, p = 0.0001; Fig. 3e) and <1 mm (r = 0.4728, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3f). For stones with a maximum diameter >2 mm, the mean difference was -0.0011 mm (95% LoA: −0.7814–0.7792; Fig. 3h). For stones with a maximum diameter of 1–2 mm, the average difference was 0.0272 mm (95% LoA: −0.5108–0.5652; Fig. 3i), and for stones with a maximum diameter <1 mm, the average difference was 0.0817 mm (95% LoA: −0.3474–0.5108; Fig. 3j). These results demonstrated excellent agreement in the Bland–Altman plots.

In vivo clinical and external validation

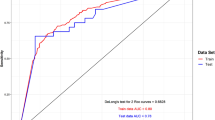

Following successful ex vivo validation, the AiFURS was further evaluated using an in vivo patient-level dataset (100 cases). Specifically, we sought to assess its real-time performance in detecting and classifying kidney stones during surgery. During the final minutes of FURS, the intra-operative video shows both systematic calyceal inspection and ureteroscope withdrawal (Supplementary Fig. 1); validation was conducted only during the inspection phase. The AiFURS accurately identified stone types, including calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid stones, achieving high values for accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV), as shown in Fig. 4a.

a, b Clinical (internal) validation. a Performance evaluation metrics for kidney stone composition. b Confusion matrix of predicted vs. actual kidney stone composition. c, d External validation. c Performance metrics. d Confusion matrix. Abbreviations: PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value.

Diagnostic metrics revealed accuracy rates of 95.3%, 92.2%, and 93.2% for calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid stones, respectively. Sensitivity and specificity were high across all stone types, confirming the model’s reliability. PPVs and NPVs further demonstrated the capacity of the AiFURS to consistently provide accurate positive and negative identifications. The confusion matrix in Fig. 4b compares the model’s predictions with spectrophotometric analysis, highlighting correct and misclassified predictions. Moreover, the AiFURS achieved an average real-time inference speed of ~20 frames per second (fps), which is well-aligned with the original video frame rate of 22.7 fps.

Furthermore, we selected an additional 80 cases for external validation of the AiFURS, achieving high accuracy rates of 86.8%, 92.2%, and 87.7% for calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid stones, respectively (Fig. 4c, d).

Peri-operative predictors of reoperation risk

The AiFURS was employed to detect residual stones in each renal calyx at the end of surgery and classify them into three size categories: <1 mm, 1–2 mm, and >2 mm. A total of 100 patients were included in this analysis, divided into a stone-free group (71 patients) and a reoperation group (29 patients). At initial presentation, all enrolled patients had unilateral kidney stones and underwent FURS. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on both groups (Supplementary Table 1). In the univariate analysis, the proportion of RFs >2 mm showed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.099 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.059–1.142, p < 0.001), 1–2 mm showed an OR of 0.977 (95% CI: 0.956–0.990, p = 0.038), and <1 mm showed an OR of 0.934 (95% CI: 0.903–0.967, p = 0.036). Analysis of stone location resulted in an OR of 7.69 (95% CI: 2.133–27.700, p = 0.002) for distal stones and 2.56 (95% CI: 0.918–7.157, p = 0.072) for multiple stones.

In the multivariate analysis, the proportion of RFs >2 mm showed an OR of 1.154 (95% CI: 1.080–1.233, p < 0.001), RFs (computed tomography [CT]) showed an OR of 70.249 (95% CI: 7.168–688.433, p < 0.001), distal stones had an OR of 40.197 (95% CI: 2.743–589.124, p = 0.007), and multiple stones had an OR of 6.252 (95% CI: 0.706–55.366, p = 0.100). Since post-operative CT is not a pre-operative indicator, the multivariate analysis without post-operative CT is presented in Table 2. We observed that the total number of kidney stones on post-operative CT images and the percentage of intra-operative RFs > 2 mm significantly predicted the need for reoperation, providing an immediate assessment of risk stratification at the end of surgery.

In addition, external validation of our approach using 80 additional cases yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 2).

Comparison of stone composition assessment between the AiFURS and urologists

To evaluate stone composition, 20 urologists reviewed surgical videos and provided visual assessments via a questionnaire. Our results show that the accuracy of the AiFURS in evaluating stone composition is much higher than that of manual evaluation by urologists (Table 3).

Discussion

Integrating AI into surgical image analysis, particularly in urology, marks a significant shift in surgical practice15. Deep learning approaches have primarily been used to identify stone composition from endoscopic images25,26,27,28,29,30 and assess stone volume using CT scans33,34,35. However, there is a notable gap in research concerning intra-operative decision-making, particularly in the real-time estimation of stone size during surgical procedures. A key innovation of this study is the real-time intra-operative detection and classification of kidney stones, which reduces reliance on post-operative imaging modalities such as ultrasound and CT scans and enables intra-operative prognostic assessment. Specifically, we used an AiFURS to identify stone types, sizes, and counts during surgery31, leveraging over 6,000 annotated images. A YOLOv11-N-based AiFURS outperformed various popular state-of-the-art lightweight real-time models, including RT-DETR-S/v2-S36,37, D-FINE-N/S38, YOLOv8-N/S39, YOLOv9-T/S40, YOLOv10-N/S41, and YOLOv12-N/S42 in mAP@50 with the lowest latency and the fewest FLOPs while obtaining state-of-the-art latency-accuracy and FLOPs-accuracy trade-offs. It is applicable to and suitable for real-time intra-operative deployment.

According to the European Association of Urology urolithiasis guidelines, information on stone composition can help patients set realistic expectations and guide follow-up planning and medical management strategies43. Traditionally, stone composition is determined post-operatively through microscopic analysis, chemical testing, or infrared spectroscopic techniques; this process often necessitates wait times for external reports, leading to delayed decisions. In contrast, the AiFURS enables real-time intra-operative analysis, providing surgeons with immediate feedback on stone composition with high sensitivity (recall) rates for calcium oxalate (95.2%), calcium phosphate (94.7%), and uric acid (88.9%). This instant information facilitates optimization of laser power and frequency settings44, improving fragmentation efficiency, reducing the “popcorn effect” (uncontrolled fragmentation that obscures the visual field), and minimizing the risk of secondary damage caused by prolonged laser activation. These technical advancements are crucial for significantly improving the outcomes of laser lithotripsy and enhancing the surgeon’s ability to achieve a stone-free outcome.

Reliable evaluation of AI performance requires comparison with clinical expertise. In this context, we designed a questionnaire to compare the AiFURS’s predictions to those of experienced surgeons. Specifically, 20 urologists independently reviewed surgical videos and provided visual assessments of stone composition. Our results corroborate previous studies indicating that visual assessments of urolithiasis during endoscopy do not reliably predict stone composition, with diagnostic accuracy often limited45. In contrast, the AiFURS demonstrated the potential to support surgeons by accelerating judgment and decision-making, with its visual outputs planned for display on an auxiliary screen next to the primary endoscopy screen.

Accurately assessing the maximum diameter of RFs after laser lithotripsy is critical for evaluating stone expulsion efficiency and predicting surgical prognosis. Traditional evaluations of this parameter rely on the surgeon’s experience and the scale of the ureteroscope lens. However, this approach is limited by image clarity and depth of field and increases the risk of damaging the ureteroscope. To overcome these limitations, herein, we proposed a novel method that uses the laser fiber as a reference object (occupying one-quarter of the endoscopic screen width), in conjunction with the YOLO algorithm, to enable the reliable identification of the size of moving stones.

The presence of residual stone fragments after FURS is a significant risk factor for the need for secondary procedures. Traditionally, post-operative CT scans are used to assess stone clearance and determine the necessity of reoperation. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the standard FURS post-operative follow-up evaluation method and highlights the significant predictive factors for reoperation risk, including the size and location of residual stone fragments and post-operative CT findings46. The AiFURS developed in the present study allows for real-time RF size and count tracking, helping to determine whether the surgical endpoint has been reached. Logistic regression analysis indicated that the proportion of RFs of varying sizes within each renal calyx during the final 5 min of FURS was significantly associated with post-operative outcomes, whereas the absolute fragment count was not. This finding suggests that the proportion of RFs is a more reliable predictor of prognosis. We hypothesize that the proportion-based method can mitigate the impact of repeated detection errors inherent to AiFURS, such as those arising from tracking limitations in algorithms such as BoT-SORT where RFs may sporadically appear and disappear from the visual field.

Importantly, while AiFURS demonstrates strong intra-operative performance, several contextual factors highlighted in recent literature may influence its real-world generalizability. First, image quality—critical for AI model input—varies significantly across ureteroscope platforms. A comparative analysis of three single-use flexible ureteroscopes found notable differences in image resolution, tip deflection, and ergonomic handling, all of which may affect the clarity and consistency of video inputs used by AI systems47. Second, pre-operative double J stenting, commonly performed to facilitate ureteroscopic access, may alter renal pelvic anatomy and visibility. A multi-center study showed that stent indwelling time >20 days was associated with increased post-operative infection rates and longer operative times, possibly due to mucosal edema and inflammatory changes that could impair AI-based visual interpretation48. Therefore, future validations of AiFURS should consider stratifying outcomes by scope type and stent duration to enhance model robustness. Lastly, while AiFURS provides precise intra-operative metrics, the translation of these outputs into patient-understandable information remains underexplored. A recent evaluation of AI-generated patient education materials revealed that most chatbot responses, including those powered by large language models, failed to meet recommended readability levels and lacked actionable guidance49. This underscores the need to develop patient-facing interfaces that accompany AI systems like AiFURS, ensuring that surgical outcomes are communicated in a comprehensible and clinically meaningful manner.

This study has several limitations. First, as a pilot study, only single-component stones were included. Thus, class imbalance was present in the dataset. Future studies should include mixed-composition stones, expand the sample size, and ensure a balanced distribution of different stone types to provide a more comprehensive understanding. Second, the width and height of a bounding box capture only an object’s extent along the image axes and do not necessarily reflect its actual maximum caliper diameter. For non-rectangular or curved shapes, the maximum distance between any two points often lies in a direction that is not parallel to the box edges50. Third, this study is a single-center, retrospective report. Therefore, comprehensive multi-center validation is required to enhance the generalizability and robustness of AiFURS. To address these limitations, we have initiated AI-assisted Kidney Stones Randomized Controlled Trial (AI-STONE-RCT), a multi-center, prospective, randomized, superiority trial. That will enroll 500 patients across five institutions. This protocol will provide evidence requisite for technology certification of AiFURS. Fourth, the absence of randomization constrains causal inference. Although multivariable logistic regression adjusted for recognized confounders, unmeasured factors (irrigation flow, cumulative laser energy) may still inflate the reported OR for reoperation. Fifth, the 6-month follow-up horizon captures only early reinterventions, whereas repeat procedures occur beyond 12 months, particularly in metabolically active patients3. The paucity of long-term data, therefore, underestimates the true number-needed-to-treat and biases cost-effectiveness estimates in favor of the intervention. Sixth, the single-center design inevitably introduces institutional specificity, all procedures were performed by a small cohort of high-volume surgeons using a uniform ureteroscope platform. Such homogeneity enhances internal validity yet simultaneously restricts external generalizability. Furthermore, the following exceptional cases in surgical videos can influence the AiFURS’s size estimation: (1) operator-related variability: differences in surgical technique, especially among novice surgeons, may lead to intra-operative ureter or renal pelvis injury with bleeding or excessive RFs due to suboptimal laser power settings; (2) pre-existing conditions: patients with severe pre-operative UTIs often exhibit pronounced inflammatory hyperplasia and abundant purulent secretions, causing stones to be enveloped by a purulent inflammatory coating that renders their margins indistinct; and (3) in patients with medullary sponge kidney and stone recurrence, stones are often not fully exposed, making detection challenging. Recognizing this limitation, our consortium has already initiated AI-STONE-RCT-II, a prospective, multi-center trial designed specifically to stress-test AiFURS under visually challenging conditions. The protocol will deliberately enroll patients with active bleeding and severe pyonephrosis and will prospectively label these “difficult” frames using a consensus panel of 3 expert urologists. We will then fine-tune the YOLOv11-N backbone by incorporating an additional module designed to improve detection in visually challenging frames.

In conclusion, the AiFURS described herein uses YOLOv11-N for real-time kidney stone detection and classification during surgery. It estimates stone type, size, and number with a pixel-to-millimeter conversion factor for precise measurements. BoT-SORT tracking ensures consistent stone identification. For the first time, we show that the number and maximum diameter of RFs observed during the final 5 min of FURS surgery, as detected by AiFURS, are prognostic indicators for the need for secondary procedures, enabling more informed decision-making, optimized laser settings, and reduced complications from incomplete stone fragmentation. Above all, this AiFURS represents a significant step forward in endourology precision medicine.

Methods

Dataset

To develop and validate an AiFURS for detecting and classifying kidney stones during FURS surgery, intra-operative ureteroscopy videos were acquired at the Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China, from 2022–2024. Videos with marked hemorrhage, purulent secretions or densely clustered RFs were excluded to ensure high-quality ground-truth annotation. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (internal registration no. S2022-387-01). All patients provided written informed consent. The internal dataset consisted of three components (model development, ex vivo, and in vivo datasets) as described in Supplementary Notes 1 and 2. An external test set was used to ensure the robustness of the AiFURS. The internal and external datasets are illustrated in Fig. 5.

The internal dataset was divided into three branches: model development (6170 frames with 11,870 annotated objects, derived from 30 surgical videos), ex vivo validation (191 videos with 1–10 stones arranged at random and 300 single-stone videos), and in vivo validation (100 videos captured during the final 5 min of each procedure). An independent external test set contained 80 surgical videos recorded during the final 5 min of surgery.

AI-assisted FURS

The AiFURS was developed for real-time kidney stone detection and classification. We used the YOLOv11-N algorithm31 for training, followed by detection and clinical validation.

YOLOv11-N is a deep CNN designed for real-time object-detection tasks. The strengths of the YOLO series, including its rapid detection capacity, have been further improved, introducing new structures and training techniques to improve detection accuracy51,52. In the present work, the model was trained to detect kidney stones in surgical videos acquired using retrograde intrarenal surgery53. The main tasks were identifying kidney stones and their composition, size, and number during surgery. The YOLOv11-N architecture was structured into three main components: the Backbone, Neck, and Head, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The Backbone component extracted features from the input image using convolutional layers (3 × 3 Conv), cross-stage partial with 2 convolution blocks (C3k2), spatial pyramid pooling fast (SPPF), and cross-stage partial with pyramid squeeze attention (C2PSA), enhancing feature reuse and computational efficiency. The Neck aggregated these features through convolution (3 × 3 Conv), upsampling, C3k2 blocks, and concatenation to facilitate multi-scale detection. The Head generated the final output, including bounding boxes, confidence scores, and class probabilities for detected kidney stones, ensuring accurate identification. The YOLOv11-N-guided kidney stone detection process is illustrated in Supplementary Note 3. Additionally, to evaluate the most appropriate real-time object detectors for kidney stone detection, various state-of-the-art lightweight detectors, including YOLO-based detectors (YOLOv8-N/S, YOLOv9-T/S, YOLOv10-N/S, YOLOv11-S, and YOLOv12-N/S) and DETR-based detectors (RT-DETR-S/v2-S and D-FINE-N/S), were tested31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42.

Ureteroscopy video frames are analyzed by the YOLOv11-N Backbone, Neck, and Head to predict stone locations and generate bounding boxes. BoT-SORT then tracks each stone across frames by assigning it a unique ID. Pixel dimensions are converted to millimeters using a fixed ratio, after which RFs are binned into categories of <1 mm, 1–2 mm, and >2 mm for counting and statistical analysis. Grad-CAM heatmaps overlay model attention, offering visual interpretability. Abbreviations: AiFURS artificial intelligence flexible ureteroscopy system, Grad-CAM gradient-weighted class activation mapping, RFs residual fragments, 3 × 3 Conv convolutional layers, C3k2 cross-stage partial with 2 convolution blocks, SPPF spatial pyramid pooling fast, C2PSA cross-stage partial with pyramid squeeze attention.

To ensure precise estimation of kidney stone size during surgery, the YOLOv11-N model incorporates a target size conversion mechanism. To this end, the pixel dimensions of the detected stones’ bounding boxes are converted into real-world measurements using the predefined conversion ratio in Eq. (1):

where \({S}_{{\rm{real}}\,}\) is the size of the kidney stone (mm), \({S}_{{\rm{pixel}}\,}\) is the size of the bounding box in pixels, and \(R\) is the pixel-to-millimeter conversion ratio calibrated based on the ureteroscope’s field of view and magnification. Figure 7 shows the external and endoscopic views of a reusable flexible ureteroscope (FLEX-XC 11278VS, STORZ, Germany) with a 200-μm holmium laser fiber. The fiber occupies one-quarter of the endoscopic screen width when it is extended 3–4 mm from the scope54,55. The AiFURS’s Measurement Mode was used to calculate the conversion ratio (\(R\)) by comparing the pixel distance to the fiber’s actual diameter for accurate stone size estimation.

The AiFURS features a Measurement Mode that utilizes the diameter of a 200-μm holmium laser fiber tip as a reference by which to establish a pixel-to-millimeter conversion factor. The default setting assumes that the fiber occupies approximately one-quarter of the screen width. The AiFURS permits manual adjustments to accommodate variations in fiber size or positioning, ensuring accurate real-time measurement of stone size during procedures. Abbreviations: AiFURS artificial intelligence flexible ureteroscopy system.

To maintain consistent tracking of kidney stones during surgery, the BoT-SORT multi-object tracking algorithm was integrated into the YOLOv11-N model32. The system assigned unique IDs to all detected stones and tracked their motion across video frames. The bounding boxes and IDs were updated dynamically in Eq. (2):

where \({B}_{t}\) denotes the updated bounding box of the stone in the current frame t, \({B}_{t-1}\) is the bounding box of the stone in the previous frame, and \({\Delta }_{t}\) represents motion offset (i.e., position change) between consecutive frames estimated by the BoT-SORT algorithm. This integration ensures accurate stone tracking, preventing duplicate or missed measurements, and provides real-time feedback on stone size, type, and number. The AiFURS’s graphical user interface was developed using PyQT5 and is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Clinical validation

Clinical validation of the AiFURS involved data from 100 patients, including cases with calcium oxalate (61 cases), calcium phosphate (22 cases), and uric acid (17 cases) stones. All cases were single-component stones. Renal pelvic calculi were defined as proximal stones, whereas upper, middle, and lower calyceal calculi were categorized as distal stones. Potential selection bias was mitigated by consecutive patient enrollment and the inclusion of all eligible cases meeting predefined criteria during the study period. To reduce operator-related bias, all procedures were performed by a small group of experienced surgeons using a standardized protocol. Detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 3. The stone composition prediction performance of the AiFURS was evaluated using several standard metrics, described extensively in Supplementary Note 4. The AiFURS was employed at the laser lithotripsy endpoint to identify residual stone fragments. These fragments were categorized by size into three groups: >2 mm, 1–2 mm, and <1 mm. The analysis of these residual stone fragments was directly linked to patient outcomes, assessing the model’s effectiveness in improving surgical decision-making and ensuring optimal stone removal. The AI-generated stone number and size estimations were compared to measurements obtained using digital calipers to further evaluate the performance of the AiFURS (Supplementary Fig. 4). Spearman correlation and Bland–Altman analyses assessed the consistency between the AI predictions and actual measurements56.

Moreover, we recruited 20 urologists to review surgical videos and evaluate stone composition, with the dual aim of assessing diagnostic accuracy45. The videos were integrated into a questionnaire, played in a continuous loop, and could be viewed an unlimited number of times. The questionnaire interface is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The raters’ median working experience was 18.50 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 11.75–20.75), median endourology experience was 15.50 years (IQR: 9.25–17.75), and the median number of ureteroscopic lithotripsy cases per year was 384 (IQR: 276–384).

External validation

The external validation cohort included 80 cases, with detailed information supplied in Supplementary Table 4.

Computational setup

Model development was performed by fine-tuning a YOLOv11-N algorithm (100 layers, 2.6 million parameters) pre-trained on the COCO dataset57, using annotated images extracted from ureteroscopy surgery videos, for 200 epochs with a batch size of 16 on NVIDIA A100 (40GB) GPUs. The process was implemented using Python, PyTorch, and OpenCV, with stochastic gradient descent as the optimizer (Supplementary Table 5). The detailed hyperparameters used to fine-tune the DETR-based models are presented in Supplementary Table 6. Input images were resized from their original resolution of 1920 × 1080 to 512 × 512 pixels. To simulate the constrained computational environment of the AI-assisted module during FURS surgery, clinical and external validation assessments were conducted on a personal computer equipped with a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 Laptop GPU (4 GB) and an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-11800H CPU.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as quartiles and medians or as standard deviations and means. Categorical variables are presented as absolute counts and percentages. Quantitative variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, while categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable logistic regression models identified prognostic indicators for reoperation risk, including stone count and maximum diameter during the final minutes of the procedure. Two-sided p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Spearman correlation and Bland–Altman plots were generated using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). We adhered to the Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM)58 as detailed in Supplementary Table 7.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This study developed an AI-FURS using the YOLO series, RT-DETR, D-FINE, and BoT-SORT. The source code for these models can be accessed at the following links: YOLO series: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics; RT-DETR: https://github.com/lyuwenyu/RT-DETR; D-FINE: https://github.com/Peterande/D-FINE; BoT-SORT: https://github.com/NirAharon/BoT-SORT. The code of the proposed AiFURS is available at https://github.com/Jamie-HM/AiFURS.

References

Thongprayoon, C., Krambeck, A. E. & Rule, A. D. Determining the true burden of kidney stone disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 736–746 (2020).

Khan, S. R. et al. Kidney stones. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 1–23 (2016).

Skolarikos, A. et al. Metabolic evaluation and recurrence prevention for urinary stone patients: an EAU guidelines update. Eur. Urol. 86, 343–363 (2024).

Alelign, T. & Petros, B. Kidney stone disease: an update on current concepts. Adv. Urol. 2018, 3068365 (2018).

Singh, P., Harris, P. C., Sas, D. J. & Lieske, J. C. The genetics of kidney stone disease and nephrocalcinosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 224–240 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Risk factors for nephrolithiasis formation: an umbrella review. Int. J. Surg. 10, 1097 (2024).

Lavan, L., Herrmann, T., Netsch, C., Becker, B. & Somani, B. K. Outcomes of ureteroscopy for stone disease in anomalous kidneys: a systematic review. World J. Urol. 38, 1135–1146 (2020).

Panthier, F. et al. What is the definition of stone dust and how does it compare with clinically insignificant residual fragments? A comprehensive review. World J. Urol. 42, 292 (2024).

Subiela, J. D. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing fluoroless ureteroscopy and conventional ureteroscopy in the management of ureteral and renal stones. J. Endourol. 35, 417–428 (2021).

Prezioso, D., Barone, B., Di Domenico, D. & Vitale, R. Stone residual fragments: a thorny problem. Urol. J. 86, 169–176 (2019).

Ghani, K. R. & Wolf, J. S. Jr What is the stone-free rate following flexible ureteroscopy for kidney stones? Nat. Rev. Urol. 12, 281–288 (2015).

Alzahrani, M. A. et al. Comparative efficacy of different surgical techniques for pediatric urolithiasis—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Androl. Urol. 13, 1127 (2024).

Danilovic, A. et al. Assessment of residual stone fragments after retrograde intrarenal surgery. J. Endourol. 32, 1108–1113 (2018).

Gumbs, A. A. et al. The advances in computer vision that are enabling more autonomous actions in surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Sensors 22, 4918 (2022).

Nedbal, C. et al. Artificial Intelligence for Endoscopic Stone Surgery: What’s Next? An Overview from the European Association of Urology Section of Endourology. Eur. Urol. Focus https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2025.02.013 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. Artificial intelligence assisted real-time recognition of intra-abdominal metastasis during laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery. npj Digit. Med. 8, 9 (2025).

Mascagni, P. et al. Computer vision in surgery: from potential to clinical value. npj Digit. Med. 5, 163 (2022).

Bernal, J. et al. Comparative validation of polyp detection methods in video colonoscopy: results from the MICCAI 2015 endoscopic vision challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36, 1231–1249 (2017).

Jin, Y. et al. SV-RCNet: workflow recognition from surgical videos using recurrent convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 1114–1126 (2017).

Twinanda, A. P. et al. Endonet: a deep architecture for recognition tasks on laparoscopic videos. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36, 86–97 (2016).

Ali, S. Where do we stand in AI for endoscopic image analysis? Deciphering gaps and future directions. npj Digit. Med. 5, 184 (2022).

Khan, R. et al. Transformative deep neural network approaches in kidney ultrasound segmentation: empirical validation with an annotated dataset. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 16, 439–454 (2024).

Setia, S. A. et al. Computer vision enabled segmentation of kidney stones during ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy. J. Endourol. 37, 495–501 (2023).

Leng, J. et al. Development of UroSAM: a machine learning model to automatically identify kidney stone composition from endoscopic video. J. Endourol. 38, 748–754 (2024).

Oh, K. T., Jun, D. Y., Choi, J. Y., Jung, D. C. & Lee, J. Y. Predicting urinary stone composition in single-use flexible ureteroscopic images with a convolutional neural network. Medicina 59, 1400 (2023).

Lopez, F. et al. Assessing deep learning methods for the identification of kidney stones in endoscopic images. In Proc. 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 2778-2781 (IEEE, 2021).

Lopez-Tiro, F. et al. On the in vivo recognition of kidney stones using machine learning. IEEE Access 12, 10736–10759 (2024).

Gonzalez-Zapata, J. et al. A metric learning approach for endoscopic kidney stone identification. Expert Syst. Appl. 255, 124711 (2024).

Zhu, W. et al. Segprompt: using segmentation map as a better prompt to finetune deep models for kidney stone classification. Medical Imaging with Deep Learning 1680–1690 (PMLR, 2024).

Estrade, V. et al. Towards automatic recognition of pure and mixed stones using intra-operative endoscopic digital images. BJU Int. 129, 234–242 (2022).

Qiu, G. J. a. J. Ultralytics YOLO11, <https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics> (2024).

Aharon, N., Orfaig, R. & Bobrovsky, B.-Z. Bot-sort: Robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.14651 (2022).

Babajide, R. et al. Automated machine learning segmentation and measurement of urinary stones on CT scan. Urology 169, 41–46 (2022).

Yildirim, K. et al. Deep learning model for automated kidney stone detection using coronal CT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 135, 104569 (2021).

Cumpanas, A. D. et al. Efficient and accurate CT-based stone volume determination: development of an automated artificial intelligence algorithm. J. Urol. 10, 1097 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Detrs beat Yolos on real-time object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 16965-16974 (IEEE, 2024).

Lv, W. et al. Rt-detrv2: Improved baseline with bag-of-freebies for real-time detection transformer. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.17140 (2024).

Peng, Y. et al. D-FINE: redefine regression Task in DETRs as Fine-grained distribution refinement. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.13842 (2024).

Qiu, G. J. a. A. C. a. J. Ultralytics YOLOv8, <https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics> (2023).

Wang, C.-Y., Yeh, I.-H. & Mark Liao, H.-Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. European conference on computer vision, 1-21 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.13616 (2024).

Wang, A. et al. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 107984–108011 (2024).

Tian, Y., Ye, Q. & Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12524 (2025).

Bonkat, G. et al. EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6 (2023).

Johnson, J. et al. Comparative analyses and ablation efficiency of thulium fiber laser by stone composition. J. Urol. 10, 1097 (2024).

Henderickx, M. M. et al. How reliable is endoscopic stone recognition? A comparison between visual stone identification and formal stone analysis. J. Endourol. 36, 1362–1370 (2022).

Montes, A., Roca, G., Cantillo, J., Sabate, S. & Group, G. S. Presurgical risk model for chronic postsurgical pain based on 6 clinical predictors: a prospective external validation. Pain 161, 2611–2618 (2020).

Şahin, M. F., Topkaç, E. C., Şeramet, S., Doğan, Ç & Yazıcı, C. M. The efficacy and safety of three different single-use ureteroscopes in retrograde intrarenal surgery: a comparative analysis of a single Surgeon’s experience in a single center. World J. Urol. 42, 583 (2024).

Şahin, M. F. et al. The impact of pre-operative ureteral stent duration on retrograde intrarenal surgery results: a rirsearch group study. Urolithiasis 52, 123 (2024).

Şahin, M. F. et al. Still using only ChatGPT? The comparison of five different artificial intelligence chatbots’ answers to the most common questions about kidney stones. J. Endourol. 38, 1172–1177 (2024).

Preim, B. & Botha, C. P. Visual Computing for Medicine: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications (Newnes, 2013).

Redmon, J. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767 (2018).

Zou, Z., Chen, K., Shi, Z., Guo, Y. & Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: a survey. Proc. IEEE 111, 257–276 (2023).

Inoue, T., Okada, S., Hamamoto, S. & Fujisawa, M. Retrograde intrarenal surgery: past, present, and future. Investig. Clin. Urol. 62, 121 (2021).

Giusti, G. et al. Current standard technique for modern flexible ureteroscopy: tips and tricks. Eur. Urol. 70, 188–194 (2016).

Talso, M. et al. Laser fiber and flexible ureterorenoscopy: the safety distance concept. J. Endourol. 30, 1269–1274 (2016).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Agreement between methods of measurement with multiple observations per individual. J. Biopharm. Stat. 17, 571–582 (2007).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft Coco: common objects in context. Computer vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, Proceedings, Part v 13, 740–755 (Springer Nature, 2014).

Mongan, J., Moy, L. & Kahn Jr, C. E. Checklist for artificial intelligence in medical imaging (CLAIM): a guide for authors and reviewers. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2, e200029 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Research and Translational Application of Clinical Characteristic Diagnostic and Treatment Techniques in Capital City (Z221100007422123), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KJZD20240903095605007), and the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (D250402003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W., B.H., and H.M. conceived and designed the study. C.W., H.L., H.C., and R.K. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. H.L, R.K., and M.Z. implemented the algorithm and performed validation. D.S., H. Liu, D. Shen, W.W., and J.L. collected clinical samples and data. F.P. provided clinical guidance. M.Z. performed data checking and analysis. X.Z., B.H. and H.M. provided funding support and overall supervision of the project. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Liang, H., Chen, H. et al. Clinical validation of an AI-assisted system for real-time kidney stone detection during flexible ureteroscopic surgery. npj Digit. Med. 8, 728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02109-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02109-9