Abstract

Evidence that clinical decision support systems (CDSS) reduce unwarranted variation in care and improve patient outcomes remains limited, particularly for acute, high-risk conditions where deviations from clinical guidelines are costly. We evaluated utilisation of a CDSS-embedded care plan within an electronic medical record designed to support timely, protocol-driven management of a complex metabolic emergency. Among 345 episodes, the CDSS was used in just over half of cases; yet a 1% increase in utilisation was associated with a reduction in hospital length of stay by approximately 1.3%, and any use was linked to a 3.3% reduction in in-hospital mortality. Fourteen clinician interviews supported these findings but highlighted barriers such as limited awareness and lack of training that constrain meaningful use. Quantitative and qualitative evidence together suggest that well-designed CDSS care plans can reduce variation and improve outcomes, while emphasising the need for awareness, education, and workflow alignment to unlock greater value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last two decades, hospitals globally have been digitally transforming to deliver more effective, efficient, and accessible care. A core component of this transformation has been the implementation of electronic medical records (EMRs). Unfortunately, it has been harder than expected to generate value from these systems1. A key finding from recent studies is that the value generated from EMRs depends greatly on how effectively they are used2,3. This supports the intuition behind early government policies, such as the USA’s ‘meaningful use’ regulation4, but such studies are still at an early stage, and further investigations are needed of specific aspects of such meaningful use.

One critical yet understudied aspect of meaningful use is the potential to use EMRs to reduce unwarranted clinical variation, because such variation impedes multiple outcomes5. To address this important gap in the literature, this study focuses on the use of Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs) to reduce unwarranted variation in care through the use of standardised order sets and care plans. Our research question is whether such use of CDSS to reduce unwarranted variation in care leads to improved healthcare outcomes. Recent studies stress that while such tools should offer benefits, detailed quantitative testing is lacking6,7. Specifically, “patterns of standard order set use in hospitals with integrated EMRs, both over time and across speciality areas, remain a relatively unexplored area of research7.”

Unwarranted clinical variation (UCV) refers to differences in healthcare practices that cannot be explained or justified by patient needs, preferences or innovations – and it remains a significant issue8. UCV can lead to disparities in patient outcomes, increased costs, and inefficiencies in healthcare delivery. Common examples include inconsistent imaging and diagnostic testing, variation in treatment approaches for patients with similar clinical presentations, mismanagement of clinical care, and differences in surgical practices8,9,10.

One of the root causes of unwarranted clinical variation is the differences in training, knowledge, practices, experience, and adoption of technology among healthcare providers8,11. These differences can result in inconsistent application of clinical guidelines and best practices, leading to variability in patient care. The diffusion of knowledge is therefore essential to minimise these variations. Effective dissemination of clinical knowledge ensures that all healthcare providers have access to the latest evidence-based practices and guidelines, promoting consistency in care delivery12.

CDSS can be instrumental in addressing this issue. By integrating clinical guidelines into the EMR, the CDSS can prompt clinicians to follow standardised diagnostic and treatment protocols and improve adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines. It can also provide alerts and reminders, helping clinicians make informed decisions at the point of care13.

While detailed studies on the use of order sets and plans of care are lacking, early studies suggest that CDSS have the potential to improve standardisation of care. However, the link to patient outcomes remains mixed14,15. Such mixed results likely reflect, in part, the various sociotechnical challenges related to integration into workflows, clinician buy-in, and training16,17,18. In the face of this complexity, high-quality study designs with quantitative assessment of outcomes, along with qualitative assessment of context, are needed, but rare5. This study addresses that aim. To enable a focused test, we examine one specific type of care plan implemented into an EMR CDSS to reduce UCV (the Cerner PowerPlan7), and we examine its use and effectiveness in reducing clinical variation and improving outcomes in the acute setting using diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) management as a use case.

Results

Study setting

This observational study uses routinely collected clinical and administrative data from a large quaternary-care hospital. The hospital facility provides care across all major adult specialities except maternity services. Since 2017, the hospital has used Cerner’s integrated electronic medical record (ieMR) system, allowing healthcare professionals to access and update patient information. Vital signs are automatically uploaded into the system, enabling early warning alerts if a patient’s condition deteriorates. Among other modules, the ieMR in this hospital contained a large number of standardised care plans within its CDSSs.

We chose DKA as a use case because UCV in DKA-related care had been a concern at this hospital, and the hospital was motivated to learn if the use of standardised care plans in the EMR could assist. DKA is a potentially life-threatening hyperglycaemic crisis with an increasing incidence and economic burden, and it requires timely interventions, particularly in emergency department (ED) settings where many patients first present19,20. DKA management is clinically complex, and once diagnosed, standardised care plans can support clinicians by coordinating treatments such as fluid resuscitation, insulin therapy, and electrolyte replacement, and ensuring adherence to evidence-based protocols and guidelines. In principle, standardised care plans can guide clinicians in the Emergency Department and wards to reduce UCV in DKA-care management, thereby improving consistency across clinicians as well as health outcomes, but to our knowledge, this has not yet been tested.

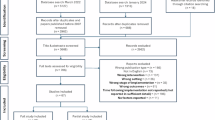

We obtained data on all DKA episodes of care from January 2018 to June 2021, totalling 345 episodes among 235 unique patients. We used two measures of the use of standardised care plans for DKA. The first measure is a binary measure of whether the care plan application (the PowerPlan) is used or not during the care episode. The second measure is a proportional measure of the number of orders ordered through the care plan out of the total number of DKA-related orders for the care episode. Having both measures allows us to look for the general pattern of findings rather than being constrained to just one measure. The dataset included a collection of 48,757 order records linked to these episodes of care, along with associated outcomes. We supplemented this data with qualitative data from interviews across the hospital.

Exploratory analysis of quantitative findings

Of 345 episodes, 151 episodes involved at least one order placed via CDSS (hereafter referred to as “CDSS episodes”), while the remaining 194 episodes did not involve CDSS orders (“non-CDSS episodes”). As shown in Table 1, patients with CDSS episodes were more likely to be female, younger, and have slightly lower comorbidity scores than those in the non-CDSS group. Regarding outcomes, patients with CDSS episodes had, on average, a 7-h longer hospital stay and a higher likelihood of 30-day readmission. However, they were less likely to die in the hospital than patients with non-CDSS episodes.

As noted above, in addition to whether an episode involved any CDSS orders, we investigated the extent of CDSS utilisation throughout the course of an episode. As shown in Table 1, a CDSS episode, on average, had around 6 orders placed via CDSS. Moreover, a CDSS episode, on average, involved more DKA-related orders in total compared to a non-CDSS episode. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the percentage of orders placed via CDSS among CDSS episodes, indicating significant variation in usage. On average, CDSS were used for approximately 8% of orders during an episode, suggesting room for further exploration of how the degree of utilisation affects patient outcomes.

Regression analyses

Table 2 shows regression results with length of stay (in logarithmic form) as the outcome variable. The results indicate that the binary measure of CDSS utilisation has a statistically significant effect on the length of stay. As shown in column (1), the use of CDSS is significantly associated with approximately a 14.8% reduction in length of stay, on average. Similarly, when we use the percentage of CDSS orders as a measure of utilisation, we find a significant and positive association with a reduction in length of stay. Specifically, as shown in column (2), a 1% increase in CDSS utilisation is associated with an average reduction of nearly 1.3% in length of stay, holding other factors constant.

Regarding mortality, the results in Table 3 (column (1)) indicate that the use of CDSS is significantly associated with a 3.3% reduction in mortality rate, on average, when controlling for the total number of DKA-related orders, patient characteristics, primary diagnosis, and treatment environment. However, when using the percentage of CDSS orders as the measure of utilisation, we do not observe a statistically significant association with mortality after controlling for these factors.

As shown in Table 4, there is no statistically significant relationship between CDSS utilisation (using either the binary or percentage measure) and the 30-day readmission rate. This lack of significance might be attributed to our data limitations, as readmission is tracked only within the treated hospital, potentially missing readmissions that occur at other hospitals in the system.

Qualitative results

We conducted 14 semi-structured interviews with 10 participants to provide context for our quantitative results and to learn additional insights from clinicians. Most interviews (n = 9) were conducted in 2021. In 2024, we followed up with 7 of these participants to update our qualitative data and explore change over time. Of these, 4 participated, 1 declined, and 2 did not respond. We also invited 4 new participants in 2024, of whom 1 participated, 1 declined, and 2 did not respond. Most participants were male (n = 7) and were involved in using or overseeing the use of the CDSS (n = 9). Interviews lasted on average 37 min (18–112 min). Overarching themes identified were: (i) User perceptions; (ii) Usage patterns; (iii) Training needs; (iv) Design and adaptability. Supplementary Table 1 provides additional evidence of the themes.

In terms of user perceptions, the CDSS was viewed positively overall, with all participants reporting its implementation as worthwhile. Participants reported many benefits of the care plan, with the most frequently mentioned being its role in standardising clinical care, saving time, serving as a reminder of clinical guidelines, preventing missed orders, and reducing errors: “I actually think they’re one of the best functionalities in (the EMR) just to standardise what we do and make the workflow easier for busy clinicians” (P07 Clinical Informatician).

All clinicians stated the initial order within the CDSS was easier and more efficient than writing individual orders for clinical management of DKA. One junior physician commented, “(I use it) because it’s quicker… It would take me far longer to chart everything” (P10). Senior physicians (n = 5) viewed the CDSS as helpful to junior physicians in particular, who may lack the clinical knowledge, confidence or skills to treat the condition.

Although participants described the design of the CDSS positively, stating it is ‘well laid out’ (n = 4) and easy to use (n = 8), the main drawback was reported to be its overwhelming appearance and complexity. Participants (n = 3) noted that while decision support within the care plan was useful, it also contributed to its daunting appearance. The links to clinical guidelines available in the care plan were reported as helpful but difficult to locate.

Regarding usage patterns, participants perceived high utilisation of the CDSS and described the care plan being used in most DKA cases. Some participants (n = 4) reported using the first component of the care plan, which outlines the initial insulin dosage, and electrolyte and fluid recommendations, finding it efficient as an initial step to their clinical management. However, a few participants (n = 2) acknowledged being unfamiliar with the later components of the care plan which focused on medication and fluid adjustments and monitoring, and reported charting further orders outside the care plan: “What often happens is the first phase is started and then anything that happens after that, it’s just added as another order somewhere in the chart” (P02 Senior Physician).

Reasons for non-use were reported as cases where DKA was mild and ordering the full care plan was not necessary, cases where DKA was severe and the patient was transferred to intensive care (which uses a different EMR system), and instances where the clinician was unaware of the CDSS. Two senior physicians reflected on the challenge of providing ongoing education to support awareness and use of the CDSS, particularly due to frequent rotations of junior physicians. Hence, there was recognition of the key role that senior clinical leadership played in driving its use, ensuring knowledge of the care plan became embedded into the practice and culture of the service: “We’d be encouraging them (junior physicians) to do it…. you know, did you use the DKA (care plan) here? That’s something that’s part of our role to ensure that it’s being utilised” (P08 Senior Physician).

With respect to training needs, all participants stated there was no formal training for the use of the CDSS. While basic hospital EMR training for junior physicians covered guidance on use of care plans in general, participants stated that specific training occurred ‘on-the-job.’ While some participants (n = 3) reported that the CDSS was intuitive and ‘easy to follow’, one junior physician (P10) stated that “a lot of (junior physicians) would only learn if someone took the time to sit down with them or they had a specialist’s time”.

Senior emergency department or endocrine physicians were reported to provide on-the-job training to junior staff when they rotated into the respective clinical area. There was a general culture that leadership needed to pass down the training and use of the CDSS to junior staff: “I guess it just comes down to word of mouth in reality amongst the junior physicians…. And then you’re relying on the corporate knowledge of the consultants, passing it down to the next crop of registrars” (P05 Senior Physician).

Finally, regarding the theme of design and adaptability, clinicians acknowledged various approaches to treating DKA but agreed that the CDSS represented the gold standard of clinical care. However, participants also stated it was important to tailor the care plan to support warranted clinical variation, highlighting the need for flexibility within its framework (n = 4). As one senior physician (P01) noted, “it’s a really good guide that does sometimes need adjusting…not everyone fits the perfect box.” Although participants (n = 7) agreed that flexibility of the care plan was a necessary feature, customising it to suit individual cases was only deemed straightforward if clinicians were well-versed in the use of the EMR system. The drawback to adaptability within the care plan arose when UCV was introduced: “We do see a lot of favorited (care plans), which can be good and bad, because (clinicians) can share them. And so you can perpetuate obviously good care and good practice, but you can also perpetuate bad practice” (P07 Clinical Informatician).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the use of the standardised care plan for DKA can be associated with improvements in clinical outcomes, particularly reductions in LOS and mortality.

In relation to standardised care plans and other CDSS interventions in DKA management, our findings align with prior research showing that standardised order sets and CDSS tools can improve clinical outcomes. Specifically, studies targeting hyperglycaemia and DKA management have reported reductions in LOS, improved glycaemic control, and more consistent adherence to clinical protocols21. For example, integrating a CDSS tool into the EMR reduced the LOS for patients with diabetes and hyperglycaemia by 6.4 h22. Similarly, another study demonstrated that introducing intensive educational interventions alongside order set implementation improved both the timeliness of DKA resolution and LOS23. Furthermore, the implementation of a DKA order set at a tertiary facility led to improved intravenous fluid replacement rates, earlier administration of required therapy, and more guideline-concordant dosing24. Beyond LOS improvements, our findings also indicate that use of the CDSS was associated with a 3% reduction in mortality. This effect is consistent with prior evidence linking poor adherence to DKA management guidelines, particularly delays in fluid resuscitation and insulin initiation, with increased mortality risk25,26,27. Embedding these guidelines directly into clinicians’ workflows via CDSS can support more timely and consistent care, potentially translating process improvements into measurable survival benefits. This aligns with findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis showing that the implementation of CPOE and CDSS tools is associated with significant reductions in ICU mortality, particularly in settings where timely intervention is critical to patient outcomes28.

These studies underscore that the success of DKA order sets often depends on forming multidisciplinary teams, targeted training, promotional strategies, and iterative updates to ensure that systems remain aligned with evolving evidence and clinician workflows. Therefore, while the CDSS was designed to reduce UCV and improve clinical outcomes, its effectiveness may be limited by its incomplete use and contingent on meaningful uptake.

With respect to adherence, uptake, and potential barriers to utilisation, our quantitative data indicate that only about half of DKA episodes utilised the CDSS, suggesting suboptimal uptake. However, qualitative feedback suggested high utilisation in clinical practice, with participants reporting positive experiences and perceived benefits of the CDSS. Several factors may explain this discrepancy. First, a sampling bias may be present, with overrepresentation of engaged users in the qualitative sample. This is a possibility given that there was only one junior physician in the sample; however, perspectives from both junior and senior physicians generally aligned. Second, the mismatch between actual and reported use may stem from a lack of awareness of the CDSS. Despite suboptimal uptake, the high satisfaction and perceived benefits of the care plan suggest a need to improve education, promotion and awareness of this CDSS tool.

Another limitation is that we were unable to examine the training level, seniority, or experience of the ordering clinicians in the quantitative data. Human resources data were not accessible, and individual ordering clinicians could not be uniquely identified beyond the specialist treating team. This constraint limited our ability to assess whether CDSS use varied systematically according to clinician experience or team composition. While our qualitative interviews suggested generally favourable views of the PowerPlan, future studies would benefit from linking EMR order data with workforce characteristics to better understand how clinician training and experience shape uptake and utilisation.

Our study also identified incomplete use of the CDSS, where the initial phase was commonly used but subsequent phases were reported to be used less frequently. While the care plan was described as adaptable to aid in warranted clinical variation, physicians often found it easier to order outside of the care plan due to limited knowledge and reported complexity of the subsequent phases of the plan. Although guidelines and decision support within the care plan were considered helpful, they did not translate into greater overall use. These findings are consistent with the well-documented challenges of embedding clinical guidelines and decision support tools into routine practice. The literature has long established that simply integrating clinical guidelines into an EMR does not guarantee their widespread adoption. Barriers – such as lack of awareness, perceived limited usefulness, or resistance to changing established workflows – can prevent effective CDSS use29. Moreover, the complexity and user-friendliness of CDSS interfaces influence clinician acceptance, and insufficient training of end-users may further reduce adherence30. Collectively, these factors imply that our regression results with binary ‘any CDSS use’ might be too crude a measure; the continuous utilisation metric might capture better the clinically relevant variation in adherence intensity.

In considering how EMR data could be better leveraged for patient journey analyses and CDSS evaluations, one limitation of our study was the inability to conduct a detailed examination of patient journeys from admission through to discharge, largely due to data quality and completeness constraints. More robust EMR data, including the sequence and timing of orders, interventions, laboratory results, and clinical assessments, could enable more in-depth analyses. Such data would clarify how and when CDSS are used and allow for causal investigation of their impact on clinical processes and outcomes.

Future research could explore whether the introduction of the automated care plan and similar CDSS interventions reduces delays in initiating evidence-based treatment protocols, minimises variations in care and outcomes, and ultimately improves patient trajectories by examining patient-level transitions within care pathways and studying the impact of CDSS engagement. We acknowledge, however, that improved data recording practices could facilitate more accurate studies of patient journeys, offering valuable perspectives on CDSS utilisation patterns and their impacts.

A strength of this study is its mixed methods design, allowing for a deeper understanding of CDSS use and effectiveness. However, due to the purposive and convenience sampling of participants who were aware of the care plan, possible selection bias in the qualitative data should be considered when interpreting the findings. Despite this, the care plan demonstrated effectiveness in improving the length of hospital stay and was experienced positively by clinicians. The qualitative data add nuance to the quantitative findings, suggesting that suboptimal uptake was not due to dissatisfaction with the tool but rather a lack of awareness and education on its optimal use.

Overall, our findings highlight the potential of CDSS-based care plans to reduce unwarranted variation and improve mortality and LOS for complex conditions such as DKA. Future research can benefit from taking an even more nuanced view of meaningful EMR use – tracing clinician interactions across each phase of the order set, linking these behaviours to patient trajectories, and capturing both clinical and economic outcomes across multiple sites and settings. While the observed reductions in mortality and length of stay are encouraging, they suggest that the benefits of such tools are most likely to be realised when seamlessly integrated into system design, clinician training, and routine clinical practice.

Methods

The quantitative component of this study examined the use of the automated care plan (the Cerner PowerPlan) and its impact on mortality, length of stay, and hospital readmission within 30 days. Given observed differences in patient characteristics between episodes involving the automated care plan and those that do not, we use multiple regression analysis to assess the impact of care plan utilisation on patient outcomes while controlling for potential confounders. Additionally, the decision to use the automated care plan may be influenced by factors such as whether DKA is the primary diagnosis and the treatment environment (e.g., the expertise and knowledge of the clinical team managing the episode). Thus, we also attempt to control for these factors in our regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed in the Stata software package31.

Specifically, we estimate the following multiple regression equation

where \({y}_{i}\) is an outcome measure for episode \(i\). In this study, we utilise three outcome measures, which are (i) a continuous variable representing length of stay of episode \({i}\) (in logarithmic form), (ii) a binary variable indicating whether episode \(i\) is associated with a readmission within 30 days of discharge, and (iii) a binary variable indicating whether episode \(i\) is associated with an in-hospital death.

\({CDS}{S}_{i}\) is a measure of the use of the automated care plan (via the Cerner PowerPlan). We consider two measures of CDSS utilisation, which are (i) a binary variable indicating whether any CDSS orders were placed during episode \(i\), and (ii) a continuous variable representing the percentage of total orders that were placed via CDSS during episode \({i}\).

To control for patient characteristics, we include variables for gender (\({Mal}{e}_{i}\)), age at the time of admission (\({Ag}{e}_{i}\)), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (\({Comorbidit}{y}_{i}\)). We also include a binary indicator (\({Endocrinolog}{y}_{i}\)) to account for whether the patient was admitted under an endocrinology service. The endocrinology service often manages patients admitted primarily for DKA, with clinical teams specialised in endocrine conditions compared to other admitting or emergency department services. These teams are more likely to use the PowerPlan systematically, given their familiarity with its protocolised, guideline-based approach to DKA management. We therefore include an indicator for endocrinology admission to account for differences in both patient case-mix and clinician practice, thereby reducing potential confounding in the estimated effect of PowerPlan utilisation.

We also control for the total number of DKA-related orders in an episode as a proxy for case complexity. Specifically, we include the logarithm of the total number of DKA-related orders in the regression model (\({TotalOrder}{s}_{i}\)). To capture variations in the treatment environment, particularly the expertise and knowledge of the clinician team, we include a set of indicator variables representing the ward to which each patient was admitted (\({War}{d}_{i}\)). This helps control for differences in care practices and resource availability across different wards.

Lastly, \({\epsilon }_{i}\) is the error term in the model. The error term is allowed to include unobserved factors that might impact patient outcomes. However, it is assumed that after controlling for observed factors, the error term is uncorrelated with the utilisation of CDSS. Since the model includes a constant term, this assumption can be formalised without loss of generality as

It is important to note that our sample also includes episodes corresponding to repeat patients. By making this assumption, we effectively assume that, conditional on the observed factors discussed above, repeated visits do not systematically bias the estimated effect of CDSS utilisation. Nevertheless, repeated episodes may introduce within-patient correlation in the error term. While our identifying assumption ensures consistency of the estimates, methods such as clustering standard errors at the patient level or including patient fixed effects (where longitudinal data are available) can further improve inference.

We report the regression results (estimated by OLS) of the model for the length of stay, mortality, and readmission within 30 days of discharge as outcome variables in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4, respectively. By using OLS, we assume a linear probability model for mortality and readmission. As a robustness check, we also estimate the models for these two binary outcome variables using Logistic regression; the results are qualitatively the same and quantitatively similar.

In each table, the first column reports the results where a binary \({CDS}{S}_{i}\) variable represents whether an episode involves any automated care plan orders. Meanwhile, the last column reports the results for the percentage of automated care plan orders to capture the extent of CDSS utilisation during the episode. As a sensitivity check, we also report in Supplementary Tables 2–4 the results for different specifications of the model, where we exclude some selected control variables from the regression model.

To complement the quantitative analysis, semi-structured interviews were conducted with multidisciplinary staff to explore perceptions, values, and experiences of the CDSS (Table 5). Convenience and snowball sampling were used to invite participants who used, or had knowledge of the use of the CDSS. Participants include senior physicians or medical directors (n = 7), a junior physician (n = 1), a senior nurse (n = 1) and a clinical informatician (n = 1), each with varying roles related to use, design or governance of the care plan (Supplementary Table 5). The interviews aimed to ascertain participant perspectives on use, workflows, training, design, governance, and sentiment towards the CDSS.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams. Researchers TH and ABJ conducted 9 interviews in 2021; TH conducted 6 independently, ABJ conducted 1 independently, and 2 were conducted collaboratively. In 2024, SR and ABJ conducted 5 interviews, 3 collaboratively and two independently by SR. TH is an academic researcher who developed the interview guide and is experienced in conducting qualitative research. ABJ is an information systems academic highly experienced in interview data collection and analysis. SR is a clinician-researcher with experience in qualitative data collection and analysis. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using Pacific Transcription or via Microsoft Teams' built-in transcription. SR reviewed transcripts for accuracy, and thematic analysis32,33 was conducted within NVivo Version 1434. SR conducted data familiarisation to gain a comprehensive understanding of the content prior to assigning initial codes. These codes were then modified to aid in developing overall themes. Researcher ABJ reviewed these themes for accuracy and consensus.

Data availability

The data used in this study were drawn from integrated electronic medical records, the Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC), and Death Registrations from the Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages. These de-identified datasets were linked by the Queensland Statistical Services Branch. Due to the sensitive nature of the data and restrictions specified in the ethics approvals and governance agreements under which access was granted, the datasets cannot be shared publicly. Access to the data may be possible for qualified researchers who obtain the necessary approvals from the relevant Human Research Ethics Committees and data custodians, in compliance with applicable privacy, confidentiality, and data governance requirements.

Code availability

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/MP version 19 (StataCorp LLC). The custom code and scripts used to generate and analyse the datasets are not publicly available due to governance restrictions but can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Colicchio, T. K., Cimino, J. J. & Del Fiol, G. Unintended consequences of nationwide electronic health record adoption: challenges and opportunities in the post-meaningful use era. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e13313 (2019).

Lin, Y.-K., Lin, M. & Chen, H. Do electronic health records affect quality of care? Evidence from the HITECH Act. Inf. Syst. Res. 30, 306–318 (2019).

Wani, D. & Malhotra, M. Does the meaningful use of electronic health records improve patient outcomes?. J. Oper. Manag. 60, 1–18 (2018).

Brailer, D. J. Guiding the health information technology agenda. Health Aff. 29, 586–595 (2010).

Hodgson, T., Burton-Jones, A., Donovan, R. & Sullivan, C. The role of electronic medical records in reducing unwarranted clinical variation in acute health care: systematic review. JMIR Med. Inform. 9, e30432 (2021).

Hodgson, T., Burton-Jones, A. & Sullivan, C. Addressing unwarranted clinical variation in healthcare as a quality improvement process. In Proc. 55th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 3885–3891 (IEEE, 2022).

Naicker, S. et al. Patterns and perceptions of standard order set use among physicians working within a multihospital system: mixed methods study. JMIR Form. Res. 8, e54022 (2024).

Sutherland, K. & Levesque, J. F. Unwarranted clinical variation in health care: definitions and proposal of an analytic framework. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 26, 687–696 (2020).

Ayabakan, S., Bardhan, I., Zheng, Z. & Kirksey, K. The impact of health information sharing on duplicate testing. MIS Q. 41, 1083–1104 (2017).

Harrison, R. et al. Addressing unwarranted clinical variation: a rapid review of current evidence. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 25, 53–65 (2019).

Wennberg, J. E. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ 325, 961–964 (2002).

Runnacles, J., Roueché, A. & Lachman, P. The right care, every time: improving adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. 103, 27–33 (2018).

Park, Y., Bang, Y. & Kwon, J. Clinical decision support system and hospital readmission reduction: evidence from US panel data. Decis. Support Syst. 159, 113816 (2022).

Eden, R., Burton-Jones, A., Scott, I., Staib, A. & Sullivan, C. Effects of eHealth on hospital practice: synthesis of the current literature. Aust. Health Rev. 42, 568–578 (2018).

Sahota, N. et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for acute care management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement. Sci. 6, 1–14 (2011).

Eden, R. et al. Unpacking the complexity of consistency: insights from a grounded theory study of the effective use of electronic medical records. In Proc. 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (IEEE, 2018).

Liberati, E. G. et al. What hinders the uptake of computerized decision support systems in hospitals? A qualitative study and framework for implementation. Implement. Sci. 12, 1–13 (2017).

Sutton, R. T. et al. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 17 (2020).

Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B. & Garg, R. Management of hyperglycemia and diabetes in the emergency department. Curr. Diab. Rep. 17, 1–8 (2017).

Nyenwe, E. A. & Kitabchi, A. E. Evidence-based management of hyperglycemic emergencies in diabetes mellitus. Diab. Res. Clin. Pract. 94, 340–351 (2011).

Sly, B., Russell, A. W. & Sullivan, C. Digital interventions to improve safety and quality of inpatient diabetes management: a systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 157, 104596 (2022).

Pichardo-Lowden, A. R. et al. Clinical decision support for glycemic management reduces hospital length of stay. Diab. Care 45, 2526–2534 (2022).

Blair, A. M. J., Hamilton, B. K. & Spurlock, A. Evaluating an order set for improvement of quality outcomes in diabetic ketoacidosis. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 40, 59–72 (2018).

Flood, K. et al. Implementation and evaluation of a diabetic ketoacidosis order set in pediatric type 1 diabetes at a tertiary care hospital: a quality-improvement initiative. Can. J. Diab. 43, 297–303 (2019).

Singh, R., Perros, P. & Frier, B. Hospital management of diabetic ketoacidosis: are clinical guidelines implemented effectively?. Diabet. Med. 14, 482–486 (1997).

Sola, E. et al. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis in a teaching hospital. Acta Diabetol. 43, 127–130 (2006).

Umpierrez, G. & Korytkowski, M. Diabetic emergencies - ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 12, 222–232 (2016).

Prgomet, M., Li, L., Niazkhani, Z., Georgiou, A. & Westbrook, J. I. Impact of commercial computerized provider order entry (CPOE) and clinical decision support systems (CDSSs) on medication errors, length of stay, and mortality in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24, 413–422 (2017).

Devaraj, S., Sharma, S. K., Fausto, D. J., Viernes, S. & Kharrazi, H. Barriers and facilitators to clinical decision support systems adoption: a systematic review. J. Bus. Adm. Res. 3, 36 (2014).

Westerbeek, L. et al. Barriers and facilitators influencing medication-related CDSS acceptance according to clinicians: a systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 152, 104506 (2021).

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, 2023).

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N. & Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (ed. Liamputtong, P.) 843–860 (Springer Nature, 2019).

Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412 (2022).

NVivo (Lumivero, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP170101154). The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Jodie Austin for her valuable clinical informatics support and thank the team of clinicians who generously contributed their time and insights through the interviews. We also extend our thanks to Dr. Raelene Donovan for her guidance throughout the project, and to Professor Brenda Gannon for her advice at several stages of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P., S.R. and A.B.J. drafted the main manuscript. B.H.N. contributed to the quantitative analysis and supported related sections of the manuscript. T.H. assisted with ethics approval, literature review, and data analysis. C.S. facilitated data access, contributed to the interpretation of results, and provided clinical guidance. A.B.J. secured the funding for the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pak, A., Robertson, S.T., Nguyen, B.H. et al. Mixed methods evaluation of a clinical decision support system to reduce variation in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 8, 781 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02141-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02141-9