Abstract

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are essential for long-term infusion in vulnerable pediatric patients. Optimal tip placement in the lower third of the superior vena cava or at the cavoatrial junction is critical to prevent serious complications. Verifying correct tip position in infants and toddlers is challenging because of very small anatomic target zones, non-standard radiograph acquisition, interference from other devices, low contrast, and high risk of catheter migration. Existing automated segmentation methods, mostly developed for adults, perform poorly on pediatric images. We retrospectively collected 1184 PICC patients from three medical centers, including 280 pediatric cases (210 neonates, 46 infants, 24 toddlers), with appropriate ethical approval. We introduce TopNet, a topology-preserving embedded network designed for automated PICC segmentation in pediatric patients. TopNet maintains catheter continuity and enables precise tip localization under difficult conditions. Quantitative and qualitative evaluations show superior segmentation and tip localization on both internal and external validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous clinical scenarios necessitate long-term catheterization for therapeutic infusion or parenteral nutrition support1,2,3, including multi-cycle chemotherapy in oncology patients, nutritional supplement for those with impaired enteral intake, and sustained pharmacotherapy for pediatric congenital heart disease. The drugs injected into these patients usually have high concentrations and are highly irritating. Therefore, a catheter that can be left in place for a long time and reduce venous irritation is particularly important for them4,5. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), a flexible, small-bore conduit advanced through peripheral veins into central vasculature, offers an optimal solution6,7. Its procedural simplicity, reduced vascular trauma, and avoidance of repeated venipuncture render it particularly suitable for sustained access. PICCs, as the preferred clinical choice for establishing a durable venous access in non-dialysis patients, facilitate rapid drug dilution within high-flow central circulation, thereby significantly attenuating vascular irritation and mitigating complication risks such as phlebitis8,9.

Nonetheless, PICC placement in infants and toddlers presents distinct physiological and behavioral challenges compared to adults10. Anatomical constraints in the pediatric population, including reduced vessel calibers, thin and collapsible venous walls, and diminished vascular compliance, significantly increase puncture difficulty and catheter dislodgement risk. Moreover, procedural distress frequently induces agitation and involuntary movement in these patients, often leading to insertion failure. Extensive research confirms that PICC tip position is a critical determinant of both therapeutic efficacy and complication rates11. Malpositioned tips can lead to severe adverse events, including catheter dysfunction, arrhythmias, cardiac tamponade, thrombotic events, and bloodstream infections12,13. The optimal tip position for an upper extremity PICC is within the lower third of superior vena cava or at the cavoatrial junction14. Notably, the target zone for pediatric tip placement is considerably smaller (only 2.77 cm) compared to that for adults (5.71 cm) (Fig. 1a, b), underscoring the inherent difficulty in achieving correct catheter positioning. Even following successful initial placement, tip migration may occur due to suboptimal venous selection, limb movement, post-flush catheter displacement, hemodynamic changes, or external tissue compression15. Infants and toddlers are at heightened risk of migration owing to movement during crying, which further compromises catheter retention and long-term usability.

Yellow arrows and squares denote the PICC tip position and target zone. Red indicates the length of the target zone. a Standard adult PICC radiograph. b–d Pediatric PICC radiographs demonstrating non-standard positioning, medical device interference, and low-contrast. e–h Corresponding ground-truth PICC labels.

Radiographic monitoring of PICC lines is a standard clinical practice, yet it demands specialized radiological expertise for accurate interpretation16. In practice, delays in image interpretation can lead to delays in therapeutic intervention. Although nurses are primarily responsible for post-insertion catheter care, most lack sufficient training to assess PICC position accurately17. This competency gap complicates routine clinical decision-making, potentially delaying management of complications, increasing patient discomfort, and raising healthcare costs. As a result, there is a clinical need for accessible PICC segmentation tools that enable precise catheter localization and tip verification, particularly in infant and toddler populations.

Deep learning has emerged as a widely used approach for medical image segmentation. Current approaches to PICC segmentation consist of coarse-to-fine frameworks18, multi-stage networks19, and multi-task models20. However, these methods are primarily developed for adult populations and fail to accommodate the unique challenges presented by infants and toddlers. These challenges include: (1) Performance degradation in non-routine views: Existing methods perform reliably on standard anteroposterior radiographs that capture dominant thoracic regions (Fig. 1a), but suffer significant performance decline when applied to non-standard projections. Pediatric PICC radiographs are frequently acquired in unconventional views, which often include reduced regions of interest and increased non-thoracic content (Fig. 1b–d), significantly complicating catheter identification. (2) Constrained target zones: The acceptable range for optimal tip placement is exceptionally narrow in infants and toddlers. For example, this target zone spans only 2.77 cm in a typical 2-year-old (Fig. 1b) and becomes even more restricted in children under 2 years old. (3) Interference from medical devices: The presence of life-support and monitoring equipment (Fig. 1c) introduces complex imaging artifacts that often obscure the catheter. (4) Low contrast and resolution limitations: PICCs inherently exhibit low radiopacity against surrounding tissues (Fig. 1d). While modern vascular segmentation methods achieve high accuracy in angiographic studies (e.g., 97.11% accuracy in ref.21), accurate delineation of low-contrast PICC lines remains a technical challenge.

To address these critical challenges, we develop a novel deep learning framework (TopNet) for automated PICC segmentation in infant and toddler radiographs. Compared to competitive methods, TopNet demonstrates superior performance on pediatric radiographs, particularly excelling in challenging scenarios involving non-standard views, medical device interference, and low contrast. The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Unlike previous adult-focused study, TopNet specifically targets segmentation challenges unique to infants and toddlers - a population characterized by limited data availability and inherently poor image quality (see Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first dedicated deep learning framework developed for pediatric PICC segmentation.

-

2.

This work retrospectively assembled a multi-center dataset of 1184 PICC patients, which includes 280 pediatric cases, comprising 210 neonates (≤28 days), 46 infants (29 days–1 year), and 24 toddlers (1–3 years), all collected with appropriate ethical approval.

-

3.

A novel topology-preserving embedded network is designed to maintain essential catheter structural continuity. Through deep supervision, TopNet attains topology-aware segmentation, significantly improving the accuracy of PICC tip identification. Quantitative and qualitative evaluations demonstrate that TopNet outperforms existing competitive approaches.

Results

This section first introduces baseline methods and evaluation metrics used for comparison, followed by a demonstrates the effectiveness of proposed PICC segmentation strategy.

Baseline methods and metrics

To demonstrate superiorities of TopNet, six state-of-the-art deep learning-based segmentation approaches were selected for comparison: DFANet22, FSNet18, MDANet23, MISSFormer24, RSF-Conv25, and UNet++26. Baseline models were re-trained to ensure optimal performance for comparison. Among these, FSNet represents the fine-stage component of MAGNet18, a coarse-to-fine framework for PICC segmentation. Due to the absence of chest contour labels in our dataset, only FSNet’s fine-stage model was re-trained.

Building on prior research, four metrics were applied for quantitative evaluation: intersection over union (IoU), Dice coefficient (Dice), Recall, and tip distance error (TDE). IoU measures region overlap between predicted and ground-truth segmentations. Similarly, Dice quantifies segmentation overlap while effectively balancing precision and recall. TDE describes spatial error associated with localizing PICC tip. Superior model performance is indicated by higher values of IoU, Dice, and Recall, along with a lower TDE score.

Internal validation

Upper extremity PICC segmentation: Fig. 2 shows an original image and corresponding segmentation results for a representative pediatric upper extremity PICC radiograph from Center I, as yielded by DFANet, FSNet, MDANet, MISSFormer, RSF-Conv, UNet++, and TopNet. Within these segmentation overlays, green indicates correctly identified PICC regions (true positives), red corresponds to false detections, and blue highlights missed target areas (false negatives). Compared to standard adult chest X-rays, the pediatric radiograph in Fig. 2a is slightly tilted and exhibits substantial occlusions, particularly along the right and inferior regions, which significantly complicate PICC detection. The thin structure of the PICC and its frequent overlap with bony structures make complete segmentation challenging. For example, discontinuous segmentation manifests as gaps within green areas, as seen in (b). Incomplete segmentation is evident in (c), (d), and (g), with model (g) failing entirely to identify the PICC. False positives (red regions) are present in (c), (f), and (h). Notably, these erroneous detections in (c) and (f) occur near the PICC tip, while those in (h) are mainly localized to the right side of the catheter. These observations underscore the superiority of TopNet over baseline models.

a Original upper extremity PICC radiograph from an infant / toddler from Center I. b–h Segmentation results obtained using different methods: DFANet, FSNet, MDANet, MISSFormer, RSF-Conv, UNet++, and TopNet (proposed). Green suggests correctly identified areas (correct detections), red denotes false detections, and blue marks undetected target regions (missed detections).

For the upper extremity testing data (n = 16), Table 1 presents quantitative metrics comparing baseline methods and the proposed approach across IoU, Dice, Recall, and TDE. The proposed method consistently outperforms all baselines, achieving the highest mean values for IoU (0.5675), Dice (0.7094), and Recall (0.6840). RSF-Conv ranks second in segmentation metrics (IoU, Dice, Recall). Among other baselines, MISSFormer delivers the strongest overall performance with a moderate TDE (7.2209 mm). Conversely, Unet++ yields the poorest results, demonstrating the lowest IoU, Dice, and Recall. FSNet and MDANet exhibit intermediate performance. These comprehensive improvements confirm the superiority of the proposed method, representing a substantial advancement over existing solutions.

Lower extremity PICC segmentation: Fig. 3 displays a representative pediatric lower extremity PICC radiograph from Center I, comparing the original image with segmentation results from several methods. The original image (a) contains severe streak artifacts that considerably impair the segmentation performance of baseline approaches. As shown by the blue regions in (b–e) and (g), DFANet, FSNet, MDANet, MISSFormer, and UNet++ completely fail to detect the PICC line. Although RSF-Conv achieves accurate delineation of the catheter, it results in discontinuous segmentation and misidentification (f). In contrast, TopNet eliminates these discontinuities and false positives, while also detecting clinically relevant catheter segments that were omitted in the manual annotations. In (h), blue represents expert-annotated regions, while the yellow dashed circle highlights the actual PICC region that was absent in the manual reference. This demonstrates the ability of our approach to identify genuine PICC line features that were initially overlooked during annotation.

Quantitative comparisons for the lower extremity testing dataset (n = 6) are detailed in Table 2. The proposed method demonstrates consistent superiority across all baselines, achieving the highest IoU, Dice, and Recall scores, alongside the lowest TDE (3.1230 mm), indicating exceptional spatial precision. Among the comparative methods, RSF-Conv ranks as the closest competitor. Other non-RSF-Conv baselines exhibit notable limitations: MDANet attains moderate IoU and Recall but suffers from considerable localization inaccuracy, as indicated by its high TDE (21.5908 mm). MISSFormer shows highly inconsistent performance, with low IoU and large standard deviations (SD = ±0.17 to 0.27). Both DFANet and UNet++ demonstrate critically low Recall scores (0.0775 and 0.1398, respectively), suggesting severe under-segmentation, and are associated with the highest TDE values (e.g., 31.08 mm for UNet++), indicating profound localization failure. Importantly, only TopNet achieves a TDE below 3.125 mm, whereas all baseline methods exhibit significant tip localization errors exceeding 21 mm.

Table 3 lists quantitative comparisons across the combined testing dataset (n = 22, comprising 16 upper extremity and 6 lower extremity PICC placements). Consistent with Tables 1 and 2, TopNet validates performed best, achieving optimal segmentation accuracy (highest IoU, Dice, and Recall) alongside superior spatial precision (lowest TDE). RSF-Conv performs competitively as a secondary alternative. Conversely, other baseline methods exhibit significant under-segmentation and poor localization accuracy. These results confirm clinically significant advantage in segmentation fidelity and catheter localization accuracy for the proposed method.

Tip localization: Although the proposed method achieves continuous and complete PICC line segmentation (see Figs. 2 and 3, and Tables 1–3), clinical practice prioritizes accurate tip localization over full-line segmentation due to the risk of severe complications from malpositioned tips. In this work, PICC tip position is defined by tracing the terminal endpoint of skeletonized segmented result. Figure 4 shows a representative pediatric PICC radiograph with segmented results and tip detections across different methods. White rings indicate ground-truth tip positions, while black rings mark predicted tip positions. While all methods generate tip predictions, their accuracy varies significantly. For instance, the predicted tip position in (b) lies farther from ground truth than other methods. (e) and (f) achieve closer proximity to ground truth than (c), (d), and (g), while (h) presents near-perfect alignment between predicted and actual tip positions. The comparative results validate the superior tip localization accuracy of proposed method.

Red squares denote the zone of the PICC tip. a Representative pediatric PICC radiograph from Center I. b–h Segmentation and tip localization results from comparative methods. White rings denote ground-truth tip positions, and black rings indicate predicted tip positions. Yellow arrows highlight the position of the black rings.

Similarly, TDE is employed to evaluate tip localization performance, calculated as Euclidean distance between predicted and ground-truth tip coordinates. As displayed in Tables 1–3, the proposed method achieves minimal TDE scores, demonstrating its capability for precise tip position prediction, a critical factor in preventing clinical complications.

External validation

Center II: To evaluate the model’s robustness and generalizability, external validation is conducted using an dataset from Center II. Figure 5 illustrates the segmentation results of a representative pediatric PICC radiograph from this center. Figure 5a–g displays the segmentation and tip localization results produced by DFANet, FSNet, MDANet, MISSFormer, RSF-Conv, UNet++, and TopNet, respectively, while (h) provides the manual ground-truth annotation. In terms of segmentation completeness, several models (a–d) exhibit significant under-segmentation, whereas others (e, f) achieve better coverage at the risk of introducing false positives. Regarding continuity, gaps or discontinuities are commonly observed in outputs (a–f). In contrast, TopNet (g) effectively addresses both completeness and continuity issues. For tip localization accuracy, models such as UNet++ (f) show substantial placement errors, while RSF-Conv (e) and TopNet (g) demonstrate superior performance, with only minimal deviation from the actual tip location. This comparative visualization underscores the distinct strengths and limitations of each method. Accurate tip localization is critical, and models exhibiting high TDE or fragmented segmentations are considered clinically unreliable due to the potential for misinterpretation. TopNet exhibits promising performance, closely approximating the expert-annotated ground truth.

Table 4 summarizes the quantitative results of IoU, Dice, Recall, and TDE evaluated on the external testing set from Center II. The findings clearly indicate that TopNet delivers performed best across all metrics, achieving the highest scores in IoU, Dice, and Recall, along with the lowest TDE. Its relatively low standard deviations further confirm the method’s robustness and reliability. MISSFormer ranks as the second-best performer in segmentation metrics such as IoU and Dice, but displays higher TDE and greater variability compared to TopNet. The remaining baseline methods (DFANet, MDANet, FSNet, RSF-Conv, and UNet++) exhibit considerably inferior accuracy and elevated errors. Certain models, e.g., DFANet, demonstrate pronounced predictive inconsistency, as evidenced by high standard deviations, thereby limiting their clinical applicability. Overall, Table 4 provides a comprehensive quantitative assessment using independent validation, underscoring that TopNet model exceeds current competitive techniques in both segmentation quality and tip localization precision.

Center III: To further assess the TopNet’s robustness and generalizability, another external validation is performed using data from Center III. Figure 6 depicts the segmentation results of a representative pediatric PICC radiograph obtained from this center. The manual annotation in (h) provides the ground-truth reference for evaluating the automated results presented in (a–g). Notable variations in performance are observed across the automated methods in terms of both segmentation accuracy and tip localization. TopNet (g) clearly demonstrates superior performance, with segmentation contours that align most closely with the ground truth in both morphology and continuity. Its tip localization is precise and reliable, showing only minimal divergence from the reference (h), which indicates strong feature extraction capabilities and generalizability. UNet++ also delivers competitive results, although some minor discrepancies are observable. In contrast, the remaining methods, particularly DFANet and FSNet, exhibit substantial limitations in segmentation quality and tip positioning, underscoring their constrained clinical applicability for reliable PICC assessment.

Table 5 provides a quantitative comparison of multiple segmentation methods evaluated on the testing dataset from Center III, comprising 76 pediatric PICC radiographs. Consistent with the results shown in Tables 1–4, TopNet outperforms all other approaches across every metric, demonstrating strong superiority in both segmentation accuracy and tip localization precision. It achieves the highest scores in IoU (0.5442), Dice (0.6838), and Recall (0.6809), as well as the lowest TDE (3.2014 mm). The relatively low standard deviations further attest to its stable and reliable performance. Among the comparative methods, FSNet proves to be the strongest competitor, particularly in terms of Dice and Recall. UNet++ performs relatively well in tip localization, as reflected by its low TDE, but lags behind in segmentation metrics. MDANet and MISSFormer generally underperform across most measures, while DFANet, exhibiting the highest TDE and among the lowest IoU, proves unsuitable for this clinical application. Together, Tables 1–5 and Figs. 2–6 affirm the effectiveness and generalizability of TopNet, which delivers consistently superior performance across both internal and external validation datasets. These results indicate that TopNet is not only highly accurate but also robust, positioning it as a promising tool for pediatric PICC line segmentation and tip localization.

Statistical analysis

Figure 7 provides a comparative boxplot analysis of various segmentation models evaluated across three medical centers (Center I, II, and III) using three performance metrics: IoU, Dice, and Recall. TopNet consistently outperforms all other models at every center and across all metrics, demonstrating strong generalization capability. Models like MDANet and MISSFormer exhibit moderate yet relatively consistent performance. In contrast, DFANet and FSNet show greater variability, performing competitively in certain centers but less effectively in others. RFS-Conv displays a notable trend, achieving strong results in Center I but underperforming in the other two centers. Center III consistently achieves high performance metrics across nearly all models, whereas Center II appears to be the most challenging, with markedly lower scores for the majority of models. This inter-center discrepancy is likely attributable to variations in image quality. The observed performance gap underscores the challenge of achieving model generalization in clinical environments. TopNet’s robust and superior performance suggests it is a promising candidate for cross-center deployment. The substantial variability among models emphasizes the importance of context-aware model selection tailored to specific clinical settings. Overall, this analysis highlights both the advancements in medical image segmentation and the persistent challenges in developing models that perform reliably across diverse clinical datasets.

Figure 8 presents the statistical significance of performance comparisons between TopNet and six benchmark methods across three independent medical centers: Center I (n = 22), Center II (n = 28), and Center III (n = 76). The results, evaluated using four key metrics, IoU, Dice, Recall, and TDE, were statistically compared using two-tailed non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. TopNet demonstrates consistent superiority over the baseline models, with nearly all p-values ≤ 0.002 and the majority being below 0.001. Notably, the most significant improvements are observed in Center III, which has the largest sample size (n = 76), indicating strong generalizability of TopNet to larger and more diverse datasets. Clinically critical metrics such as TDE, which reflects accuracy in catheter tip localization, show particularly low p-values (e.g., <0.001), underscoring the model’s potential to enhance patient safety. Minor exceptions, such as p-values of 0.054 or 0.104, occur primarily in smaller datasets (e.g., Center I) or less critical metrics, suggesting that TopNet’s advantage remains robust though slightly influenced by data size and task specificity. Overall, these results provide evidence that TopNet outperforms existing competitive methods across diverse clinical settings and evaluation criteria. Its high accuracy, especially in tip localization, positions it as a reliable tool for improving PICC assessment workflows.

Discussion

This section discusses some issues related to TopNet, including its application to adult PICC segmentation, its failure cases on pediatric PICC segmentation, and its limitations.

This study represents the first investigation into the feasibility and accuracy of PICC segmentation in infant and toddler radiographs, providing foundational evidence for image-based catheter assessment in this vulnerable population. Due to the challenges associated with obtaining large volumes of infant and toddler PICC radiographs, we augmented the dataset with 47 radiographs from children (ages 3–14 years), 13 from adolescents (ages 14–18 years), and 859 from adults for model development (training, validation, and testing) at Center I. This supplementation helps mitigate the scarcity of infant and toddler data while improving model generalizability. Notably, the proposed method demonstrates competitive performance in adult PICC segmentation, even though it was primarily designed for pediatric applications.

Figure 9 displays representative left- and right-insertion PICC radiographs along with their corresponding segmentation results. Green indicates correctly identified PICC segments, blue suggests missed regions, and red denotes erroneous detections. Both adult cases display predominantly green trajectories, indicating accurate catheter tracing along the entire PICC course with minimal discontinuities.

Quantitative comparisons on 183 older patients (≥3 years) are presented in Table 6, evaluating various segmentation methods regarding IoU and Dice metrics. Consistent with Tables 1–5 (pediatric results), the metrics are substantially higher for adult radiographs. This performance disparity is likely attributable to the larger volume of pediatric and adult data (919 vs. 280 images), enabling more robust feature learning. The cross-domain generalization capability demonstrated in Fig. 9 and Table 6 confirms the robustness and transferability of the proposed methodology beyond its primary pediatric application scope.

Despite its strengths, the proposed method exhibits certain limitations. The model remains susceptible to misidentification and under-segmentation when processing PICC radiographs with significant artifacts, particularly those containing other catheters or exhibiting suboptimal image quality. For example, Fig. 10a, b display original pediatric PICC radiographs, while (c) and (d) present their corresponding segmentation results from TopNet. In (c), a non-PICC catheter located in the upper-right region is erroneously identified due to its similar intensity profile. (d) illustrates a case of under-segmentation. Typically, catheters segmented by TopNet are correctly located within the right atrium adjacent to the thoracic vertebrae. However, in this instance, the greater distance between the right atrium and vertebrae caused the model to fail in segmenting the intrathoracic portion of the catheter, leading to suboptimal performance. Future work will focus on mitigating these issues by increasing the diversity of pediatric cases in the training dataset.

Although the proposed segmentation approach accurately delineates both PICC shafts and tip positions, facilitating clinical assessment of PICC placement accuracy and tip migration risks, it still exhibits three key limitations. First, the model’s generalizability is constrained by the limited availability of annotated PICC datasets, since robust learning architectures inherently require large-scale and diverse training samples. Multi-center collaborations to expand dataset diversity and scale are thus essential. Second, although the method serves as a valuable auxiliary tool for radiograph interpretation by improving clinical efficiency through precise PICC localization during image review and nursing prognosis, its computational complexity requires further optimization. Developing lightweight variants would be necessary to enable real-time deployment in clinical settings. Third, future research will focus on exploring 3D reconstruction and dynamic tracking technologies to enhance catheter insertion path planning.

To advance PICC segmentation in pediatric radiographs, this work introduces an innovative integration of topological consistency through three contributions: (1) First pediatric-focused investigation: Unlike previous adult-centered research, this work represents the first dedicated effort on PICC segmentation specifically designed for infants and toddlers. (2) Curated pediatric dataset: To address the challenge of limited data availability and inherently lower image quality in pediatric imaging, we retrospectively assembled a multi-center dataset comprising 1184 PICC patients, including 280 pediatric cases (210 neonates, 46 infants, and 24 toddlers). (3) Topology-aware architecture: We provide a novel topology-preserving network that maintains critical PICC structural continuity, combined with a deep supervision strategy to promote anatomically coherent segmentation and significantly improve tip localization accuracy. Experimental results demonstrate robust generalization across different pediatric age groups and strong adaptability to non-standard radiographic views, thereby substantially expanding clinical applicability beyond conventional positioning requirements. The proposed approach outperforms competitive methods, achieving optimal performance across IoU, Dice, Recall, and TDE metrics. Collectively, this technique enhances critical post-insertion radiographic assessment of PICC tip position, facilitating early intervention against serious catheter-related complications.

Methods

This section provides a detailed illustration of data acquisition and preprocessing, and the proposed segmentation model.

Data acquisition

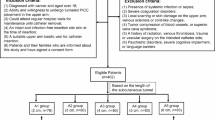

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University (No. KJ2025-348-01), Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and Yili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Friendship Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all guardians prior to PICC insertion. Between June 2012 and July 2025, a total of 1200 participants were enrolled across three medical centers, including 280 children aged 1 day to 3 years. Figure 11 presents the participant enrollment, allocation, and follow-up flowchart for this multicenter study. Among them, 1184 participants (98.7%) met all inclusion and exclusion criteria, provided completed and valid X-ray radiographs accompanied by radiologist-verified manual annotations, and were included in the final analysis. With this evaluable cohort, 55.0% were female. The catheter was annotated as a continuous pixel-wise mask along its visible trajectory, with the tip marked as the terminal endpoint of this mask. Non-PICC structures—such as monitoring leads, other tubes, and bony margins—were explicitly excluded. Window level and width settings were manually adjusted during annotation to improve visualization. Primary annotations were generated by a resident physician (Z Cheng, with 3 years of experience in medical data analysis) and subsequently reviewed by an attending radiologist (P Zhang, with 10 years of experience in medical data analysis). Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

This study aims to achieve precise PICC segmentation in radiographs of infants and toddlers using a deep learning method. In accordance with standard clinical definitions, participants were categorized as neonates (first 28 days after birth), infants (29 days to 1 year), or toddlers (1 to 3 years). This retrospective analysis included participants aged 0–3 years from three centers: 108 subjects (71 male, 37 female) from Center I, 48 subjects (29 male, 19 female) from Center II, and 124 subjects (65 male, 59 female) from Center III. Demographic characteristics of the cohort, including age, gender, image resolution, and pixel dimensions, are summarized in Table 7.

However, training a robust deep learning model typically requires substantial data, and the number of available infant and toddler radiographs alone was insufficient. To address this data scarcity, we expanded the training set by incorporating additional cases. Specifically, we added PICC radiographs from 47 children (aged 3–14 years; 30 male, 17 female), 13 adolescents (aged 14–18 years; 9 male, 5 female), and 844 adults (330 male, 514 female) from Center I. As some patients contributed multiple radiographs, the augmented dataset comprised a total of 1027 images for analysis. These were randomly divided into training, validation, and testing sets in an approximate ratio of 13:3:4. Notably, to preserve clinical relevance to the target population, model testing was conducted exclusively on pediatric radiographs (neonates, infants, and toddlers). This pediatric test set consisted of 22 images, with 16 depicting upper extremity PICC placements and 6 showing lower extremity placements. This strategy enabled the development of a model with precise segmentation capability while maintaining a pediatric focus. The inclusion of adult training data enhanced the generalizability of the model without compromising its performance on pediatric-specific evaluations. After initial training on data from Center I, the model was fine-tuned using ~40% of the data from Center II and evaluated on the remaining 60%. The same partitioning strategy (~40% for fine-tuning and 60% for testing) was applied to data from Center III.

Data preprocessing

Pediatric PICC radiograph shows significant variation in image resolution, voxel size, and inherently low contrast (see Fig. 1). Original image resolution ranged from 705 × 616 to 4400 × 3610 pixels, with pixel spacing spanning from 0.0970 × 0.0970 to 0.1968 × 0.1968 mm2 (see Table 7). Given limited computing resources and to ensure training stability, we resampled all DICOM and NIfTI files to a uniform pixel spacing of 0.5 × 0.5 mm2. This resulted in resampled resolutions ranging from 304 × 304 to 860 × 707 pixels.

For public dissemination, all DICOM and NIfTI files were converted to PNG format. To preserve fine details in these PNG files, we used the resampled data for PNG generation. For DICOM files, we applied appropriate window level and width adjustments to optimize contrast in the generated PNGs. For NIfTI files, we extracted slices along relevant cross-sections and performed intensity normalization by scaling each slice's values to its minimum and maximum.

Segmentation model

The TopNet architecture is illustrated in Fig. 12. During training, the model utilizes radiographs from infants, toddlers, pediatrics, and adults. For testing, only images from infant and toddler are used. The backbone of TopNet is based on nn-UNet27, as shown in Fig. 12a. Given an input image I∈ℝC×H×W, where C, H and W represent channel, height, and width, the image first undergoes data preprocessing. It is then processed through an eight-layer encoder. Each layer contains downsampling, a double-convolution (conv) module, and skip-connections. Downsampling at the ith layer (Ii) is implemented using a conv operation with a kernel size 3 and a stride of 2, i.e.,

The double-conv module comprises two identical conv operations, each including Leaky ReLU activation (LReLU) and instance normalization (IN), viz.,

The feature Iio has twice the channel dimensionality of Iid, while its spatial resolution (i.e., width and height) are halved. To optimize computational efficiency, channel expansion ceases once reaching 512 channels, and subsequent layers maintain this channel depth unchanged.

Skip-connections are typically employed to address the problem of vanishing gradient and facilitate the training of deeper networks, which is implemented as:

where avg indicates average pooling.

Similar to the encoder, the decoder has seven layers. Each layer incorporates an upsampling followed by double-conv. Within this module, features from the connection are concatenated with those from the preceding decoder layer, as formalized by,

where cat denotes the channel-wise concatenation. Besides, deep supervision is applied to boost performance, producing an intermediate binary mask at every decoder output Iib, i=1,…,7, viz.,

where softmax (·,dim=1) normalizes the output logits into a probability map across the channel dimension.

Loss function

Given the binary segmentation task for PICC localization, a hybrid loss function addresses class imbalance and geometric consistency. TopNet is optimized through jointly minimization of three components: binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss (\({\mathcal{L}}\)Bce), Dice loss (\({\mathcal{L}}\)Dice) and topology-preserving loss (\({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{TP}}\)). The composite loss is defined as,

where λ1, λ2 and λ3 are balance factors. In this work, λ1 and λ3 are set to1, and λ2 is set to 0.5.

BCE loss penalizes misclassification errors while differentiating false positives and negatives. Dice loss explicitly mitigates foreground-background imbalance - particularly critical for PICC segmentation where catheters (foreground) occupy minimal pixels compared to background - by weighting pixel-wise overlap between predictions and ground truth. \({\mathcal{L}}\)TP enforces geometric consistency for elongated tubular structures by preserving catheter connectivity. These losses are defined as,

where y denotes the ground-truth mask (label), ŷ is the prediction mask, and ys / ŷs are their respective skeletonized versions. TP quantifies alignment accuracy between the skeletonized prediction (ŷs) and ground-truth mask (y), while TS measures correspondence between the prediction mask (ŷ) and ground-truth skeleton (ys). Breaks in the predicted catheter path reduce TS, whereas spurious side branches reduce TP.

Implementation details

Despite variations in the original input image sizes, all images were resized to 512 × 512 pixels to ensure consistent input dimensions for TopNet. The model was trained for 1000 epochs with a batch size of 4, using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01 and a weight decay of 3 × 10⁻⁵. All experiments were conducted using PyTorch 2.5.1 on a Linux system equipped with a GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. For a 512 × 512 input image, the model holds 92.46 M parameters and needs 463.14 G floating point operations of computation, achieving a processing speed of 1.85 frames per second.

Data availability

A de-identified minimal dataset (images and annotations) sufficient to reproduce the main results will be made publicly available upon acceptance at https://github.com/30410B/TopNet. The full clinical dataset is available to qualified researchers via the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code for this study is available on GitHub: https://github.com/30410B/TopNet.

References

Krein, S. L. et al. Comparing peripherally inserted central catheter-related practices across hospitals with different insertion models: a multisite qualitative study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 30, 628–638 (2021).

Moss, J. G. et al. Central venous access devices for the delivery of systemic anticancer therapy (CAVA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 398, 403–415 (2021).

Teja, B. et al. Complication rates of central venous catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 184, 474–482 (2024).

Thomsen, S. L., Boa, R., Vinter-Jensen, L. & Rasmussen, B. S. Safety and efficacy of midline vs peripherally inserted central catheters among adults receiving IV therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2355716 (2024).

Wilson, P. & Rhodes, A. Peripherally inserted central catheters: spreading the MAGIC beyond Michigan. BMJ Qual. Saf. 31, 5–7 (2022).

Lee, H., Mansouri, M., Tajmir, S., Lev, M. H. & Do, S. A deep-learning system for fully-automated peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) tip detection. J. Digit. Imaging 31, 393–402 (2018).

Pitiriga, V. et al. Lower risk of bloodstream infections for peripherally inserted central catheters compared to central venous catheters in critically ill patients. Antimicrob. Resist Infect. Control 11, 137 (2022).

Duwadi, S., Zhao, Q. & Budal, B. S. Peripherally inserted central catheters in critically ill patients - complications and its prevention: a review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 6, 99–105 (2019).

Bentridi, A. et al. Midline venous catheter vs peripherally inserted central catheter for intravenous therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 8, e251258 (2025).

Diewo, D., Mawson, J. & Shivananda, S. Reducing peripherally inserted central catheter tip migration in neonates: a proactive approach to detection and repositioning. J. Clin. Med. 14, 1875 (2025).

Jung, K. T., Kelly, L., Kuznetsov, A., Sabouri, A. S. & Lee, K. Determination of optimal tip position of peripherally inserted central catheters using electrocardiography: a retrospective study. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 76, 242–251 (2023).

Wang, L., Liu, Z. S. & Wang, C. A. Malposition of central venous catheter: presentation and management. Chin. Med. J 129, 227–234 (2016).

Jaffray, J. et al. Peripherally inserted central catheters lead to a high risk of venous thromboembolism in children. Blood 135, 220–226 (2020).

Yu, C., Shulan, L., Juan, W., Ling, L. & Chun-Mei, L. The accuracy and safety of using the electrocardiogram positioning technique in localizing the peripherally inserted central catheter tip position: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Open 9, 1556–1563 (2022).

Shah, M., Dufendach, K., Schapiro, A., Ni, Y. & Prasath, S. Comparison of various machine learning models to identify peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) tip position from radiology reports. Pediatrics 147, 6–7 (2021).

Erskine, B., Bradley, P., Joseph, T., Yeh, S. & Clements, W. Comparing the accuracy and complications of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement using fluoroscopic and the blind pushing technique. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 68, 349–355 (2021).

Vilão, A., Castro, C. & Fernandes, J. B. Nursing interventions to prevent complications in patients with peripherally inserted central catheters: a scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 14, 89 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Automatic and accurate segmentation of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) from chest X-rays using multi-stage attention-guided learning. Neurocomputing 482, 82–97 (2022).

Yu, D. et al. Detection of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in chest X-ray images: a multi-task deep learning model. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 197, 105674 (2020).

Park, S., Cha, Y. K., Park, S., Chung, M. J. & Kim, K. Automated precision localization of peripherally inserted central catheter tip through model-agnostic multi-stage networks. Artif. Intell. Med. 144, 102643 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. ERNet: edge regularization network for cerebral vessel segmentation in digital subtraction angiography images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28, 1472–1483 (2024).

Deng, H., Liu, X., Fang, T., Li, Y. & Min, X. DFA-Net: Dual multi-scale feature aggregation network for vessel segmentation in X-ray digital subtraction angiography. J. Big Data 11, 57 (2024).

Deng, H. et al. Multi-scale dual attention embedded U-shaped network for accurate segmentation of coronary vessels in digital subtraction angiography. Med. Phys. 52, 3135–3150 (2025).

Huang, X., Deng, Z., Li, D., Yuan, X. & Fu, Y. MISSFormer: an effective transformer for 2D medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1484–1494 (2023).

Sun, Z., Wang, H., Xie, Q., Zheng, Y. & Meng, D. RSF-conv: rotation-and-scale equivariant fourier parameterized convolution for retinal vessel segmentation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn Syst. 36, 16549–16563 (2025).

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. UNet++: redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1856–1867 (2020).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 203–211 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sci-Tech Plan Program of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) (2023ZD012), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102028, 82560342), Tianshan Talent Program for High-level Medical Professionals (TSYC202401B077), Financial Science & Technology Plan Program of the Eighth Division, Shihezi City, XPCC (2023NY04-3), Doctoral Fund Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University (BS2023005), Beijing Medical Award Foundation “Ruiying Scientific Research Fund Phase VII” Program (YXJL-2025-0483-0292), Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2024AFB656), and Interdiciplinary Research Program of HUST (2025JCYJ062).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y., K.C., H.D., and X.M. conceived and designed the study, and were in data interpretation. Z.C., Z.Z., K.D., X.M. participated in data acquisition and analysis. K.C., Z.C., and K.D. drafted the initial manuscript. X.Y., H.D., and X.M. jointly supervised the project and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, X., Cheng, K., Chen, Z. et al. Topology preserving embedded network for PICC segmentation in pediatric X ray images. npj Digit. Med. 9, 68 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02248-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02248-z