Abstract

Obesity is influenced by genetic predisposition and lifestyle. The associations among genetic susceptibility to obesity, lifestyle, and all-cause mortality remain unexplored. Our goal is to develop and validate a machine learning model to assess the genetic risk of obesity and examine its association with lifestyle and all-cause mortality. We integrated genetic data from 482,700 UK Biobank participants and 8,607 Nanfang Hospital participants to create and validate a stacked machine learning model, which generates an obesity-related polygenic risk score (OPRS), to evaluate the relationships among genetic risk of obesity, lifestyle, and all-cause mortality. The model achieved area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values of 0.621, 0.616, and 0.565 for the training, internal, and external test cohorts, respectively. A high OPRS is associated with increased all-cause mortality, with a linear relationship observed among individuals with normal weight or overweight. Among individuals with a high genetic risk of obesity, adhering to four healthy lifestyle factors reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 59% compared to those who did not. Thus, high genetic risk of obesity is associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality, but a healthy lifestyle mitigates this risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The obesity epidemic is a major public health problem. In 2015, 107.7 million children and 603.7 million adults worldwide were affected by obesity; these numbers continue to increase in most countries1. The association of obesity with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in the general population is well-established2,3,4. Given that obesity is partially determined by genetics, genetic factors that increase susceptibility to obesity may also increase the risk of death through obesity or its associated complications. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified many genetic variants associated with the body mass index (BMI)5,6. Although genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of obesity, there are few reliable tools to accurately estimate the genetic risk of obesity and assess the mortality risk related to it. Building risk-assessment models using multiple genetic variants may help assess the susceptibility of an individual to obesity and predict the mortality risk associated with the genetic risk of obesity.

The obesity epidemic is the result of an interaction between genes and the environment7,8,9, with societies that promote unhealthy foods and encourage sedentary lifestyles (i.e., obesogenic environments) becoming major contributing factors to excessive fat accumulation in predisposed individuals10. As lifestyle factors are related to obesity and mortality11,12,13,14,15, these modifiable lifestyle factors may partially explain the relationship between obesity and mortality. Genetic factors are known from birth, are unchangeable, and may affect the entire life process of individuals. Modifiable lifestyle factors can serve as environmental exposures that may amplify or mitigate these genetic effects16,17,18,19,20. However, whether a healthy lifestyle can offset the mortality risk associated with the genetic risk of obesity remains to be clarified.

This study aimed to establish a reliable genetic risk assessment tool for obesity and to evaluate the impact of healthy lifestyle factors (such as physical activity, never having smoked, moderate or no alcohol consumption, and a healthy diet) on the mortality risk associated with the genetic risk of obesity.

Results

Characteristics of patients in different populations

Among the 499,294 participants from the UK Biobank with available BMI data, 2626 had a BMI < 18.5, and 13,968 had missing genetic data. Among the 9489 participants from the Nanfang Hospital, 702 had a BMI < 18.5, and 180 participants had missing genetic data. Ultimately, 482,700 participants from the UK Biobank and 8607 from the Nanfang Hospital were included in the model (Supplementary Fig. 1). At baseline, the mean age (SD) in the UK Biobank was 56.5 (8.1) years, and the mean BMI was 27.5 (4.7) kg/m², with 221,490 participants being men (45.9%) and 261,210 being women (54.1%). At baseline, the mean age (SD) of the participants from the Nanfang Hospital was 38.4 (10.3) years, and their mean BMI was 23.4 (3.1) kg/m², with 4,160 participants being men (48.3%) and 4,447 being women (51.7%) (Table 1).

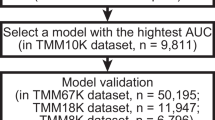

Polygenic risk score model for obesity

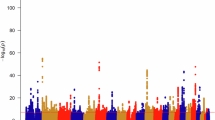

We conducted feature selection on 43,570 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from a training cohort of 337,892 individuals. We built random forest and XGBoost models, using each SNP as a genetic feature to predict participants with obesity. Based on the feature importance rankings, we selected the top 4000 most important SNPs in each model and identified 1661 SNPs at the intersection between models (Supplementary Fig. 2). Finally, we applied the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) algorithm to further refine feature selection and reduce collinearity among the SNPs and selected the most predictive SNPs for the obesity phenotype using lambda.min (λ values are shown in Fig. 1a). A total of 1048 SNPs were selected (Fig. 1b), annotated21,22, and mapped to 508 non-redundant genes, including FTO, MC4R, and GIPR. These genes are closely related to food intake, energy expenditure, and obesity risk. The effects and P-values of the SNPs are provided in Supplementary data.

a The MSE of different numbers of SNPs revealed by the LASSO model in the training cohort. A dotted vertical line is drawn at the optimal lambda values by minimum criteria, which is 1048. The lambda.min means the lambda at which the minimal MSE is achieved through 5-fold cross-validation. b LASSO coefficient profiles of SNPs. c The ROC analyses for predicting obesity in the training cohort with the stacked ML models. d The ROC analyses for predicting obesity in the internal test cohort with the stacked ML models. e The ROC analyses for predicting obesity in the external test cohort with the stacked ML models. MSE mean square error, SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, ROC receiver-operator characteristic. This graph was generated by R and Python.

First, we used four algorithms based on genetic variables and constructed a clinical characteristic model. The area under the curve (AUC) and exact values for each model in the training cohort are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Based on these four individual prediction models, we trained the stacked model and observed that it had better performance than the individual models. In the training cohort, the AUC was 0.621 (95% CI: 0.619–0.623). In the internal test cohort, when using SNP variables to predict the fusion model of obesity, the AUC was 0.615 (95% CI: 0.611–0.618). In the external test cohort, the AUC obtained when using SNPs to predict obesity was 0.565 (95% CI: 0.542–0.587) (Fig. 1c, d, e). Performance metrics for the stacked machine-learning models are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

We used a model to generate the obesity-related polygenic risk score (OPRS) for the eligible participants in the training (n = 223,722) and internal test (n = 95,757) cohorts (Supplementary Table 4). Subsequently, we categorized the OPRS into quartiles, with the lowest quartile being designated as low genetic risk of obesity, the second and third quartiles as medium genetic risk of obesity, and the highest quartile as high genetic risk of obesity. We also performed a logistic regression analysis to investigate the association between OPRS and obesity. After adjusting for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet, participants with a high genetic risk of obesity had an odds ratio (OR) of 3.06 (95% CI: 2.97–3.15; P < 0.001) in the training cohort and 2.82 (95% CI: 2.69–2.95; P < 0.001) in the internal test cohort, compared to participants with a low genetic risk of obesity (Supplementary Table 5). After adjusting for age and sex, participants with a high genetic risk of obesity had an OR of 1.83 (95% CI: 1.45–2.32; P < 0.001) in the external test cohort, compared to those with a low genetic risk of obesity (Supplementary Table 6). After using continuous OPRS as the independent variable and further adjusting for the first 20 genetic principal components, the results remained consistent (Supplementary Table 7). We constructed a generalized linear model to analyze the relationship between continuous OPRS and BMI and found that OPRS explained 4.5, 4.1, and 1.2% of the BMI variance in the training, internal test, and external test cohorts, respectively (Supplementary Table 8).

Association of obesity-related polygenic risk score with all-cause mortality and metabolism-related diseases

The training cohort had a median follow-up of 13.61 years, during which 15,108 (6.8%) participants died. The internal test cohort had a median follow-up of 13.61 years, with 6588 (6.9%) deaths recorded (Supplementary Table 4). The associations between each group and all-cause mortality were assessed. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that the patients with a high genetic risk of obesity based on the OPRS had the highest risk of all-cause mortality (Fig. 2). Subgroup results did not change for age and sex (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). After adjusting for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet, the restricted cubic spline curve showed that high OPRS was positively correlated with all-cause mortality (Fig. 3). In the BMI category, OPRS was linearly related to all-cause mortality in individuals with normal weight and those with overweight. However, a non-linear relationship was observed among individuals with obesity in the internal test cohort (Fig. 3). Subgroup results did not change for age and sex (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). After further adjustments of the measured BMI, high OPRS was still associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Compared to participants with a low genetic risk of obesity, those with a high genetic risk of obesity had an HR of 1.11 (95% CI: 1.06–1.16; P < 0.001) in the training cohort and an HR of 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03–1.18; P = 0.005) in the internal test cohort. Participants in the high genetic risk group had an 11% increased risk of mortality compared to those in the low genetic risk group (Supplementary Table 9). After using continuous OPRS as the independent variable and further adjusting for the first 20 genetic principal components, the results remained consistent (Supplementary Table 10). Additionally, we assessed the cumulative incidence of five common metabolism-related diseases across the three OPRS risk groups. In the training cohort, the cumulative incidence analysis showed a significant stratification of metabolic risk, with the high-risk group exhibiting the highest probability of developing metabolism-related clinical outcomes, while the low-risk group showed the most favorable prognosis (Supplementary Fig. 9). And similar results were observed for the internal test cohort (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Association of obesity-related polygenic risk scores and lifestyle with all-cause mortality

Compared with participants who had a low genetic risk of obesity and met four healthy lifestyle factors, participants with a high genetic risk of obesity and no healthy lifestyle factors had the highest risk of all-cause mortality. After adjusting for age and sex, the HR was 2.84 (95% CI: 2.43–3.31; P < 0.001) in the training cohort and 2.81 (95% CI: 2.23–3.56; P < 0.001) in the internal test cohort, indicating that the high-risk population had a 2.8-fold increased risk of mortality compared to the reference group (Fig. 4). In the participants with a high genetic risk of obesity, compared to those who did not meet any healthy lifestyle factor, those who met all four healthy lifestyle factors had an HR of 0.41 (95% CI: 0.35–0.48; P < 0.001) in the training cohort and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.33–0.52; P < 0.001) in the internal test cohort, indicating that adhering to all four healthy lifestyle factors could reduce the risk of death by 59% in this high-risk population (Fig. 5). After further adjusting the first 20 genetic principal components, the results remained unchanged (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12).

The models were adjusted for age, sex. a Training cohort. b Internal test cohort. OPRS, Obesity-related polygenic risk score. Lifestyle included 4 lifestyle factors (never smoking, no or moderate alcohol consumption, physical activity, and healthy diet). Participants scored 1 if they met the criterion for a healthy lifestyle and 0 otherwise. This graph was generated by R.

The models were adjusted for age, sex. a Training cohort. b Internal test cohort. Lifestyle included 4 lifestyle factors (never smoking, no or moderate alcohol consumption, physical activity, and healthy diet). Participants scored 1 if they met the criterion for a healthy lifestyle and 0 otherwise. This graph was generated by R.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between the genetic risk of obesity, lifestyle factors, and all-cause mortality. The results of this population-based cohort study show that meeting four healthy lifestyle factors is associated with a reduced risk of death from a genetic risk of obesity.

We developed a model to quantitatively assess the genetic risk of obesity by generating OPRS using data from a large population, the UK Biobank cohort, and validated it using the physical examination data from the Nanfang Hospital external test cohort. This model was based on a machine learning (ML) algorithm. Stacked ML models have higher prediction performance and universality than single models and can reduce model overfitting. In the external test cohort, a moderate decline in model performance was observed, which may be partially attributable to differences in genetic background between the European population and the current test cohort—including potential heterogeneity in allele frequency distributions and SNP effect sizes. Furthermore, systematic disparities in lifestyle, cultural context, socioeconomic environment, and healthcare systems may contribute to a lower tendency toward obesity in Chinese populations compared to European populations at similar genetic risk levels, thereby affecting the model’s generalizability. Despite this, our model maintained a significant positive correlation between the OPRS and obesity phenotypes in the external test cohort. This finding suggests that genetic risk retains a certain degree of transferability across populations.

A key feature of our ML-derived OPRS is its methodological difference from classical polygenic risk score (PRS). While both aim to aggregate genetic susceptibility, our stacked ML model integrates multiple algorithms and is specifically designed to capture non-linear and complex interactions among SNPs, thereby potentially improving predictive performance. In terms of predictive ability, the OPRS achieved AUCs of 0.621, 0.616, and 0.565 in the training, internal, and external test sets, respectively, which are comparable to recently reported obesity PRS models with AUCs ranging between 0.55 and 0.6223,24,25. This indicates that, despite its more complex architecture, the OPRS performs similarly to conventional PRS in terms of discriminative accuracy. However, a distinctive advantage of our model is its demonstrated generalizability across ethnicities, as evidenced by the external validation in a Chinese cohort—a feature often lacking in classical PRS derived from single-ancestry populations. We acknowledge that our model requires greater computational resources during the training phase compared to classical weighted-sum polygenic risk scores; however, its individual-level prediction process is fast and automatable. Once generated, the OPRS can serve as a static, long-term risk indicator, facilitating its translation and application in clinical settings. The OPRS, as an artificial intelligence-derived marker quantifying the genetic risk of obesity, retains significant value for precision prevention despite its moderate discriminative power at the individual level in external validation. Its primary utility lies in enabling population risk stratification, serving as a proactive screening tool to identify individuals—including those not currently diagnosed with obesity—with high genetic susceptibility and elevated mortality risk, thereby allowing early and targeted risk assessment. Importantly, it supports personalized intervention by providing individuals with actionable risk information and, crucially, motivational evidence from this study that adherence to a healthy lifestyle can substantially mitigate this inherited risk. Thus, the OPRS functions as an effective tool for motivating behavioral change and can guide clinicians in offering tailored recommendations for obesity risk management. Moreover, to minimize the burden on clinicians, we envision creating a user-friendly, web-based OPRS calculator or integrating the model into Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems to streamline its application. Future prospective studies should validate these pathways in diverse populations to facilitate broader implementation in clinical guidelines. However, deployment and application of the OPRS requires stringent data protection measures to safeguard participant privacy, including compliance with international standards such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Additionally, to minimize psychological harm, risk communication should be framed within the context of modifiable lifestyle factors, empowering individuals rather than inducing fatalism. And ongoing efforts to validate the model in different ethnic groups will help mitigate biases and promote equitable access to genetic risk assessment.

This study found that the 508 genes constituting the OPRS were significantly enriched across multiple biological layers. In terms of biological processes, they converge on three core axes: transcriptional regulation, central nervous system function, and metabolic signaling. At the cellular component level, they localize to key structures such as neuronal synapses and chromatin. Regarding molecular function, they are primarily concentrated in transcription factor and kinase activities (Supplementary Fig. 13). This indicates that the genetic risk captured by the OPRS may drive obesity pathogenesis through alterations in central nervous system signaling, aligning with previous findings that obesity-associated genetic variants are predominantly expressed in the central nervous system26,27.

Several studies have evaluated the risk of obesity and its complications by constructing polygenic risk scores (PRS). A study on the BMI-related PRS in a Korean population showed that a higher PRS was associated with a higher incidence of obesity and related diseases28. Another study on the BMI-related PRS constructed using data from the US population showed that the participants with a high PRS had a higher mortality risk than those with a low PRS29. Neither study further discussed the impact of lifestyle. One study used the UK Biobank to assess the association of genetic risk, lifestyle, and their interaction with obesity and obesity-related morbidities (ORMs)30. This study found that after adjusting for the measured BMI, the association of PRS with ORMs was null. However, our research discovered that OPRS can independently predict the risk of mortality, irrespective of the measured BMI. Compared to previous studies, our study is the first to use ML methods to construct OPRS to assess all-cause mortality risk and to discuss the impact of lifestyle.

Among individuals with normal weight and those with overweight, our research revealed a linear relationship between OPRS and all-cause mortality. This finding is particularly useful for clinicians who can quantitatively assess the mortality risk of individuals caused by a genetic predisposition to obesity. In the internal test cohort, individuals with obesity showed a non-linear relationship between OPRS and all-cause mortality. One possible explanation is that when OPRS values are low, there are fewer genetic variants for cumulative risk and less of an effect on mortality risk, requiring a larger sample size to observe this difference. Another possible explanation is that at low OPRS values, potential nongenetic factors are the primary drivers of obesity, and obesity driven by these potential non-genetic factors also contributes to an elevated risk of all-cause mortality29. Additionally, when the study population is restricted to individuals with obesity, collision bias may arise between OPRS and other obesity-related risk factors, leading to a spurious negative association. If these risk factors are also linked to mortality, then this could result in an increased risk of death at lower OPRS levels. High OPRS were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, which helps identify high-risk individuals. As the prevalence of obesity continues to increase, it is becoming increasingly difficult to contain this trend. Therefore, prioritizing high-risk individuals with limited medical resources is crucial to achieving maximum health benefits.

People with high genetic risk of obesity tend to have an increased risk of all-cause mortality even if they meet four healthy lifestyle factors. Although this is not statistically significant, it may not completely counterbalance the increased mortality risk associated with a high genetic risk of obesity. A study based on the UK Biobank showed that adhering to four healthy lifestyle factors cannot completely offset the health risks of obesity31. However, even if it cannot completely offset the effects of genetic risk for obesity, adopting a healthy lifestyle should still be encouraged to mitigate the associated risk of mortality. Many studies have emphasized the benefits of maintaining a normal weight to prevent premature death32,33,34,35,36. Therefore, to reduce the risk of mortality in individuals with a high genetic risk of obesity, it is important to promote healthy lifestyle habits and maintain a normal weight.

This study had a few limitations. First, causal inferences cannot be drawn because of the observational nature of the study. Second, the model was developed using data collected in Europe and externally validated using a cohort comprising the Chinese population, which may have resulted in dataset transfer issues. Third, the use of self-reported data for exposure factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet, may have led to an underestimation of their true relevance and residual confounding factors. Further prospective studies in different populations are needed to validate the health effects of OPRS, considering factors such as cost-effectiveness, resource allocation, and acceptance in clinical settings, which are critical for the clinical application of OPRS. Furthermore, even after adjusting for a range of covariates, the possibility of residual confounding factors such as socioeconomic status, mental health status, and dietary patterns cannot be ruled out. Fourth, our analyses of the interactions between genetic risk and lifestyle factors, and of the protective effects of a healthy lifestyle, were conducted entirely within the UK Biobank cohort. The lifestyle definitions used are based on a Western context. Our external Chinese validation cohort lacked comparable lifestyle data; therefore, we could not examine whether the observed lifestyle benefits generalize across different cultural and environmental settings. Future studies that incorporate culturally adapted lifestyle assessments for diverse populations are needed to confirm the universality of these interactions.

In summary, we established and validated a reliable and practical ML model based on genetics and constructed an OPRS. High OPRS were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Individuals with a high genetic risk of obesity can reduce their all-cause mortality risk by adopting a healthy lifestyle. These efforts can help identify individuals with a high genetic risk of obesity and provide them with appropriate management advice, ultimately reducing their mortality risk. To further advance the clinical application of OPRS, future studies should include trans-ethnic validation across diverse populations to establish generalizability, as well as prospective interventional trials to evaluate the efficacy of targeted interventions in OPRS-identified high-risk individuals.

Methods

Study design

In this cohort study, we selected people with a BMI ≥ 18.5 as our target population because this study focused on the genetic risk of obesity. We used genetic features extracted from the UK Biobank and Nanfang Hospital cohorts to train, validate, and externally test a stacked machine learning (ML) model, with the probability scores of the model being evaluated as an obesity-related polygenic risk score (OPRS).

First, we utilized data from 482,700 participants from the UK Biobank to train and validate a stacked ML model. Next, we externally tested the model on 8607 participants from the health examinee dataset at Nanfang Hospital (Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China). We assessed the association between the OPRS and all-cause mortality among participants in the UK Biobank. Two subsets of the training and internal test cohorts, including lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity, and diet, were extracted to explore whether a healthy lifestyle could mitigate the risk of all-cause mortality from the genetic risk of obesity.

Study population

This study included participants from two cohorts from the UK and China. The UK Biobank contains the clinical and genotype data collected from a population-based cohort, over 500,000 individuals aged 40–69 years, between 2006 and 2010 in the United Kingdom. Participants with missing covariate or genotype data were excluded. We randomly sampled participants from the UK Biobank from among a total of 482,700 individuals and divided them into a training cohort of 337,892 and an internal testing cohort of 144,808 people at a 7:3 ratio. The health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital contains information on individuals who underwent health checkups. We extracted data from individuals aged ≥18 years who visited the hospital between 2015 and 2020. Data collection and pre-processing were performed using the same criteria as those used for the UK Biobank data (Supplementary Fig. 1). Ethical approval was granted for the UK Biobank by the North West-Haydock Research Ethics Committee (REC reference16:/NW/0274) and the health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (NFEC-2019-161). All participants provided informed consent at the baseline assessment in the UK Biobank and the health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital.

Genotype data

The UK Biobank has conducted genome-wide genotyping sequencing for participants37. Genotyping was performed using the Affymetrix UK BiLEVE Array and the UK Biobank Axiom Array. Genotypes were imputed into the dataset using computationally efficient methods and combined with the Haplotype Reference Consortium and UK10K haplotype resources. For the health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital, genotyping was performed using the Infinium Chinese Genotyping Array v1.0. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. A total of 51,787 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genome-wide significantly (5 × 10−8) associated with the BMI in the GWAS analysis (http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank). Of these, we selected 43,570 SNPs that were present in both the UK Biobank and the health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital and included them in the genetic feature selection.

BMI categories and outcomes

For participants in the UK Biobank, weight and standing height were measured using a Tanita BC418MA body composition analyzer and a Seca 240-cm height measure. For participants at Nanfang Hospital, height and weight were measured using an OMRON HNH-318. According to the World Health Organization, British participants were categorized into three groups: participants with normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m²), participants with overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m²), and participants with obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m²). Based on the Chinese guidelines, Chinese participants were similarly classified as participants with normal weight (BMI 18.5–23.9 kg/m²), participants with overweight (BMI 24.0–27.9 kg/m²), and participants with obesity (BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m²)38. This population-specific approach ensures consistency within each cohort by aligning with ethnic-appropriate thresholds that account for differences in body composition and obesity-related risks, thereby improving the accuracy of risk stratification in our model. All-cause mortality was defined as death due to any cause during the observation period. The secondary outcomes were five metabolism-related diseases (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, and type 2 diabetes). Cases of metabolism-related diseases were identified based on the presence of International Classification of Diseases and self-reported codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Assessment of lifestyle factors

Information on alcohol consumption, smoking status, and physical activity was obtained using a touchscreen questionnaire, while dietary habits were obtained based on a food frequency questionnaire. Alcohol consumption was calculated based on the self-reported intake of red wine, white wine, beer, spirits, and fortified wine. In the UK, chronic heavy alcohol consumption is defined as the consumption of three or more drinks per day for women and four or more drinks per day for men (with one drink containing 8 g of ethanol)39. The smoking status was assessed, and the participants were divided into smoking and nonsmoking groups. Physical activity was measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); specifically, the number of minutes spent walking or engaging in moderate or vigorous activity per week was monitored. Regular physical activity was defined as engaging in moderate activity ≥150 min/week, vigorous activity ≥75 min/week, or moderate and vigorous activity ≥150 min/week40. A healthy diet score was attributed based on a recent definition of the ideal dietary component intake for optimal cardiometabolic health, which involves the consumption of at least four of seven commonly consumed food groups (Supplementary Table 2)41.

Genetic feature selection and enrichment analysis

We utilized the random forest and XGBoost models to rank the importance of 43,570 SNPs, subsequently selecting the top 4000 from each. Candidate SNPs were then identified through the intersection of these two datasets. We then screened candidate SNPs for internal validation by applying the LASSO regression with five-fold cross-validation to the training set. The most predictive SNPs for the obesity phenotypes were selected using the minimum criterion (lambda.min) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Finally, we extracted the genotype data associated with the selected SNPs as genetic features to develop the model. The identified SNPs were annotated to corresponding genes, and these genes were then subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) gene set enrichment analysis42,43.

Development of the ML model

In model development, we employed the stacked ML approach, which is an ensemble learning technique consisting of a multi-classifier combination and a multi-layer model framework. This study utilizes a two-layer stacked model for development44. The first layer comprises multiple base learners, with the input being the original dataset. This layer includes four base classifiers: random forest, classical XGBoost, adaptive boosting, and logistic regression. All these classifiers operate in parallel, independently predicting obesity based on genetic features, and then the aggregated results are fed into a new feature set for the second layer. The second layer contains a meta-classifier (XGBoost), which further processes the aggregated results from the base learners to derive the final genetic prediction score for obesity probability, known as the OPRS (Supplementary Fig. 3). The OPRS ranged from 0 (lowest probability of obesity predicted by genetics) to 1 (highest probability of obesity predicted by genetics). All modeling analyses were performed using the R software and Python.

To mitigate overfitting and enhance model stability, each base learner in the first layer underwent a five-fold cross-validation process. This involved randomly dividing the dataset of the training cohort into five distinct subsets of equal size, iterating through these subsets for model training (a total of five iterations). In each iteration, four of the five subsets were used simultaneously to train four base learners, while the remaining subset was utilized for internal validation to output prediction values. After completing the five iterations, each base learner trained five models and obtained five sets of prediction values. These five sets of predictions were combined and served as the new training set for that base learner to be fed into the second-layer XGBoost model. XGBoost then used the new training sets from the four base learners as feature sets for its own model training, resulting in a fully-trained stacked model after two layers of training. For internal and external test cohorts, the datasets of the internal and external test cohorts needed to be input into each of the five models of each base learner. Five sets of prediction values were obtained, and their average was taken as the new internal or external test set for that base learner. These new test sets were then fed into the trained second-layer XGBoost model, which outputs the final prediction results (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages). In the association analysis between the OPRS and all-cause mortality, Kaplan–Meier curves for all-cause mortality were generated by dividing the population into low (lowest, first quartile), medium (middle, 2nd–3rd quartiles), and high (highest 4th quartile) obesity risk groups based on the quartiles of the OPRS. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to test the association between the OPRS and outcomes. The regression models were adjusted for sex, age, and lifestyle factors. In the sensitivity analysis, further adjustments were made for the top 20 genetic principal components to correct for population stratification. The effect size of the OPRS association was reported as a hazard ratio (HR) and precision measure [95% confidence interval (CI)]. To illustrate the dose-response relationship between the OPRS and all-cause mortality, we performed restricted cubic spline function analysis with three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles. The reference point was set as the median of the variables in the corresponding population. To analyze the combined effects of the OPRS and lifestyle, the subjects were divided into 15 groups based on the combination of OPRS and the number of healthy lifestyle factors. Using the group with low genetic risk OPRS and four healthy lifestyle factors as the reference, the Cox model was employed to explore the association between genetically predicted obesity, lifestyle, and mortality. Furthermore, the association between lifestyle and all-cause mortality was investigated specifically in the population with high genetic risk for obesity. All analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

Data availability

All UK Biobank information is available online (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). This research was conducted using application number 92668. The data of the health examinee dataset of Nanfang Hospital are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

Aune, D. et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ 353, i2156 (2016).

Bhaskaran, K., Dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., Douglas, I. J. & Smeeth, L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 6, 944–953 (2018).

Global, B. M. I. M. C. et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 388, 776–786 (2016).

Loos, R. J. F. & Yeo, G. S. H. The genetics of obesity: from discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 120–133 (2022).

Novelli, G., Cassadonte, C., Sbraccia, P. & Biancolella, M. Genetics: a starting point for the prevention and the treatment of obesity. Nutrients 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122782(2023).

Hruby, A. et al. Determinants and consequences of obesity. Am. J. Public health 106, 1656–1662 (2016).

Ogden, C. L., Yanovski, S. Z., Carroll, M. D. & Flegal, K. M. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology 132, 2087–2102 (2007).

McAllister, E. J. et al. Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 49, 868–913 (2009).

Richard, D. Cognitive and autonomic determinants of energy homeostasis in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 489–501 (2015).

Michaëlsson, K. et al. Combined associations of body mass index and adherence to a Mediterranean-like diet with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003331 (2020).

Mok, A., Khaw, K. T., Luben, R., Wareham, N. & Brage, S. Physical activity trajectories and mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ 365, l2323 (2019).

Veronese, N. et al. Combined associations of body weight and lifestyle factors with all cause and cause specific mortality in men and women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 355, i5855 (2016).

Loef, M. & Walach, H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 55, 163–170 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancies in the US population. Circulation 138,345–355 (2018).

Goodarzi, M. O. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 6, 223–236 (2018).

Qi, Q. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and genetic risk of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1387–1396 (2012).

Tyrrell, J. et al. Gene-obesogenic environment interactions in the UK Biobank study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 559–575 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Physical activity attenuates the genetic predisposition to obesity in 20,000 men and women from EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000332 (2010).

Qi, Q. et al. Fried food consumption, genetic risk, and body mass index: gene-diet interaction analysis in three US cohort studies. BMJ 348, g1610 (2014).

Lu, Y., Quan, C., Chen, H., Bo, X. & Zhang, C. 3DSNP: a database for linking human noncoding SNPs to their three-dimensional interacting genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D643–d649 (2017).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Tanigawa, Y. et al. Significant sparse polygenic risk scores across 813 traits in UK Biobank. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010105 (2022).

Privé, F. et al. Portability of 245 polygenic scores when derived from the UK Biobank and applied to 9 ancestry groups from the same cohort. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 12–23 (2022).

Sutoh, Y. et al. Healthy lifestyle practice correlates with decreased obesity prevalence in individuals with high polygenic risk: TMM CommCohort study. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 9–15 (2025).

Brüning, J. C. & Fenselau, H. Integrative neurocircuits that control metabolism and food intake. Science 381, eabl7398 (2023).

Speliotes, E. K. et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 42, 937–948 (2010).

Yoon, N. & Cho, Y. S. Development of a polygenic risk score for BMI to assess the genetic susceptibility to obesity and related diseases in the Korean population. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411560 (2023).

Vinneau, J. M., Huibregtse, B. M., Laidley, T. M., Goode, J. A. & Boardman, J. D. Mortality and obesity among U.S. older adults: the role of polygenic risk. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 76, 343–347 (2021).

Kim, M. S. et al. Association of genetic risk, lifestyle, and their interaction with obesity and obesity-related morbidities. Cell Metab. 36, 1494–1503.e1493 (2024).

Rassy, N. et al. Association of healthy lifestyle factors and obesity-related diseases in adults in the UK. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2314741 (2023).

Chen, C., Ye, Y., Zhang, Y., Pan, X. F. & Pan, A. Weight change across adulthood in relation to all cause and cause specific mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ 367, l5584 (2019).

Tarp, J. et al. Fitness, fatness, and mortality in men and women from the UK Biobank: prospective cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e019605 (2021).

Yuan, Y. et al. Analysis of changes in weight, waist circumference, or both, and all-cause mortality in Chinese adults. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2225876 (2022).

Jee, S. H. et al. Body-mass index and mortality in Korean men and women. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 779–787 (2006).

Flegal, K. M., Graubard, B. I., Williamson, D. F. & Gail, M. H. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 293, 1861–1867 (2005).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Chen, C. & Lu, F. C. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 17, 1–36 (2004).

Daviet, R. et al. Associations between alcohol consumption and gray and white matter volumes in the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 13, 1175 (2022).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121, 586–613 (2010).

Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation 133, 187–225 (2016).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

Watanabe, K., Umićević Mirkov, M., de Leeuw, C. A., van den Heuvel, M. P. & Posthuma, D. Genetic mapping of cell type specificity for complex traits. Nat. Commun. 10, 3222 (2019).

Zeng, L. et al. Multimodal machine learning-based marker enables early detection and prognosis prediction for hyperuricemia. Adv. Sci. 11, e2404047 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource under Application Number 92668. We thank all the genetics consortiums for making the GWAS summary data publicly available. We thank all the participants for their selfless contributions to the study. We also thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English-language refinement. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFF1201304, 2023YFC2308500), National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82172751, 82373301, 82404077, 82400664), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022A1515110656), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZC20240663) and Guangdong Province College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Progarm (No. S202412121153).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Lushan Xiao, Shengxing Liang and Lin Zeng; Resources: Lushan Xiao and Li Liu; Investigation and methodology: Shengxing Liang, Lin Zeng, and Shumin Cai; Data curation: Lin Zeng, Jiaren Wang and Chang Hong; Formal analysis and visualization: Lin Zeng, Jiaren Wang and Chang Hong; Validation: Lin Zeng, Jiaren Wang and Chang Hong; Writing-original draft: Shengxing Liang and Lin Zeng; Writing-review and editing: Lushan Xiao, Shengxing Liang, Jiaren Wang, Pu Jiang, Shanshan Wu, Zebin Xie, Ting Li Gongfa Wu, and Weinan Lai; Funding acquisition: Lushan Xiao and Li Liu; Supervision: Lushan Xiao, Li Liu, Gongfa Wu and Weinan Lai. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, L., Liang, S., Zeng, L. et al. A machine learning-derived polygenic risk score reveals that healthy lifestyle counteracts obesity-related mortality. npj Digit. Med. 9, 72 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02314-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02314-6