Abstract

We address a critical clinical gap in real-world kidney transplantation (KT), the long-standing disconnect between structured longitudinal follow-up and text-defined clinical rules, which often leads to inconsistent reporting, poor policy compliance, and non-reproducible outcomes across centers. To resolve this, we introduce KT-LLM, a verifiable orchestration layer that bridges sequence modeling with policy and terminology-aware reasoning, tailoring explicitly to KT clinical workflows. KT-LLM ensures clinical decision-making is grounded in authority by constraining knowledge access to Banff kidney allograft pathology references, OPTN, and SRTR policy documents via retrieval-augmented generation. This design anchors answers and computable checklists to versioned sources, enabling full auditability and reducing subjective interpretation errors. The system coordinates three clinically focused, auditable agents: (i) Agent-A (SRTR-MambaSurv): Optimizes discrete-time survival and competing risk prediction from TRF-aligned trajectories via a linear-time inference backbone to personalize follow-up scheduling; (ii) Agent-B (OPTN-BlackClust): identifies clinically distinct population subtypes using stable deep embedded clustering, supporting individualized treatment stratification; (iii) Agent-C (Policy-Ops): encodes OPTN and UNOS submission timelines, SRTR reporting cadence, and Banff terminology into executable rules, returning pass, warn and fail outcomes with versioned evidence to ensure policy compliance. On de-identified OPTN and UNOS cohorts, KT-LLM outperformed strong baselines in evidence attribution and predictive calibration. Critically, it retained the ability to surface clinically distinct subgroups among Black recipients, which aligns with prior reports of outcome heterogeneity, while avoiding overgeneralization of claims beyond the analyzed window. This supports equitable subgroup analysis while avoiding clinical overreach. By anchoring reasoning and outputs to versioned policies and terminology, KT-LLM transforms the model to govern KT workflows into an auditable, clock-synchronized process. This offers a practical solution to enhance reproducibility, monitor fairness across centers and eras, and standardize clinical practice, addressing unmet needs for scalable, reliable KT care in real-world settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In real-world management and research of kidney transplantation(KT), critical evidence has long evolved along two parallel tracks: structured longitudinal follow-up and text-defined rules. On the one hand, OPTN and SRTR collect Transplant Recipient Follow-up (TRF) at 6 months post transplant, at 1 year, and annually thereafter, and release standardized analytic files1,2, thereby providing a clear and comparable time axis for time to event analyses and competing risks evaluation3. On the other hand, the Banff classification is continuously updated via a centralized online repository that standardizes terminology, lesion scoring, and diagnostic categories4,5,6, while SRTR’s Program Specific Reports (PSR) are issued on a semiannual cadence to support program-level quality oversight and public transparency7,8,9. Together, these components establish a shared evidentiary frame of high-value endpoints, authoritative rules, and governance cadence.

Despite concurrent advances, the three strands of follow-up data, pathology rules, and quality monitoring have lacked a mechanism for alignment. First, the OPTN and SRTR Standard Analysis Files (SAF) and STAR1,2 specify that each transplant should have TRF recorded at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter until re-transplant, death, or loss to follow up10,11. Recent OPTN monitoring of data submission has further specified deadlines for TRF at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years, forming a time axis and deadline structure that can and should be propagated into model development and audit. In parallel, SRTR releases PSR semiannually7,12 and publishes center-facing technical notes and key dates8, functioning as an external clock. These institutional arrangements determine data freshness, definitional scope, and reconciliation cadence and constitute prerequisites that any deployment-oriented modeling framework must explicitly align with and audit.

Second, as the internationally adopted framework for kidney allograft pathology, the Banff classification4,13,14 provides a current, searchable online version through its Central Repository, explicitly designating it as the single authoritative source supplanting prior conference reports. This affords authoritative anchors for terminology, scoring, and diagnostic categories within information systems and research workflows5,6, and creates the conditions for retrieval augmentation and computable implementation15,16.

Third, system-level concerns about equity and access are driving synchronous upgrades in rules and model evaluation17,18. Studies based on the 2015–2019 OPTN and UNOS cohort have identified clinically distinguishable and stable clusters among Black recipients using unsupervised methods and compared outcomes across groups19. Concurrently, since 2023, OPTN has implemented and iteratively refined the requirement for race-neutral Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) corrections to wait time credit20,21,22, specifying concrete operational thresholds for audit, eligibility, and documentation23. These developments reshape both the data definitions and the operative timeline, imposing explainability and traceability as front-loaded compliance conditions for any risk model or quality control tool that claims deployability.

Methodologically, medical follow-up data exhibit discrete, long-horizon, and sparse characteristics. Deep survival families provide reusable baselines for time to event and competing risks tasks, while model comparison and reporting are expected to follow standardized metrics such as time-dependent area under Curve (AUC) and Brier, enabling robust multi-center and multi-era evaluation and recalibration3,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

Recent progress in long sequence modeling offers a natural pathway for TRF-like sequences. Transformer variants have performed strongly on several tasks, but their quadratic attention cost inflates training and inference demands for multi-year follow-up32,33,34,35. Selective state space models achieve linear time, high throughput inference via input-dependent state updates and have demonstrated competitive representation quality on very long sequences, making them an apt backbone when balancing long horizon follow-up with deployment efficiency36,37. In KT, the central gap is not single metric accuracy per se, but the lack of a system that explicitly couples such linear long sequence representations with the governance clock of PSR submission deadlines and with Banff and OPTN textual rules in one auditable framework.

In parallel, text knowledge alignment has converged on a clear paradigm. Retrieval augmented generation (RAG) injects non-parametric, externally retrievable memory prior to decoding, grounding outputs in citable sources and enabling hot updates. This is well-suited to scenarios that constrain knowledge to authoritative primary sources38,39,40,41,42. Large language models for medicine that use RAG, including Med-PaLM 2, LLaVA-Med, and domain-tuned PubMedBERT pipelines, have shown strong performance on general question answering benchmarks, yet they do not combine versioned policy corpora, registry-aligned survival and clustering modules, calculator-backed checklists, and governance clocks in one auditable workflow.

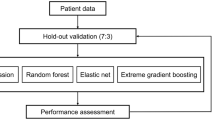

To address these needs, we propose a unified sequence text engine: a domain-constrained, retrieval-augmented language model orchestrates three auditable agents within a shared data and rules context38,39,41,42. Agent-A (SRTR-MambaSurv) builds discrete-time and competing risks models on TRF follow-up, using Mamba to encode OPTN and SRTR longitudinal registries efficiently and calibrate outputs, with comparisons against strong deep survival baselines1,2,25,26,27,36,37. The pipeline of KT-LLM is illustrated in the Fig. 1. Agent-B (OPTN-BlackClust) reproduces and extends unsupervised subtype evidence for Black recipients within the 2015–2019 OPTN and UNOS window19. Agent-C (Policy-Ops) formalizes OPTN and SRTR indicator definitions, TRF generation and submission deadlines, and the semiannual PSR cadence into executable rules callable by the LLM with full provenance8,9. The entire system restricts knowledge to the Banff Central Repository and OPTN and SRTR official documents to ensure terminological consistency, computable thresholds, and auditable evidence1,2. Figure 1 summarizes our end-to-end pipeline: a scoped RAG layer constrains evidence to official sources and standardizes definitions, while the LLM orchestrator plans and executes agent calls with parameter injection; outputs are aligned and aggregated into a structured answer.

Step 1 parses the user query into a structured intent. Step 2 performs a scoped RAG over versioned official corpora to fetch evidence with anchors and standardized definitions and thresholds. Step 3 plans tool usage and injects parameters, calling three agents: Agent-A (SRTR-MambaSurv) for long-sequence survival, Agent-B (OPTN-BlackClust) for unsupervised cohort stratification, and Agent-C (Policy-Ops) for policy and checklist computation. Step 4 aligns units and definitions and aggregates results into a structured answer.

In summary, KT-LLM is built on three pillars that define its novelty and scope. A versioned and time-aligned corpus with effective dates, and PSR-aligned freezes keeps retrieval, attribution, and calculator outputs on the same clock and on the same source scope. Coverage-aware decoding with a pointer distribution and a confidence gate enforces multi-clause grounding and returns evidence summaries when confidence is low. An executable structured checklist carries out numeric thresholds and date arithmetic with sentence-level provenance and audited tool calls. These choices enable mandatory multi-source grounding, calculator-backed answers, version-stamped citations, and hot index refresh without retraining, which extends beyond the abilities of medical LVLMs and domain LMs used as baselines.

Our goal is verifiable integration geared for operation: within one framework, textual rules become computable checklists; follow-up sequences become calibratable representations; and the governance clock becomes a set of actionable constraints. The system directly supports three classes of tasks: (1) individual-level risk stratification with uncertainty quantification; (2) population-level subtype analysis and equity monitoring; and (3) policy and operations consistency checks with traceable answers. Accordingly, evaluation is organized under public, reproducible metrics: for survival and competing risks tasks, we report C-index, time-dependent AUC, and integrated Brier; for clustering, we report stability and agreement measures; for governance tasks, we report rule trigger timeliness, concordance, and citation hit rate8,28,29,30,31,43,44. By aligning data via rules and constraining models via the governance clock, the proposed design aims to shift KT evidence model governance from manual assembly to auditable operation, supporting reproducibility and fairness across centers and eras. Unlike existing medical language or vision language models that simply attach retrieval to a large backbone, KT-LLM couples a time-aligned and versioned policy and pathology corpus, coverage-constrained decoding with an evidence pointer and confidence gate, and an executable checklist that performs numeric and temporal checks with provenance and exposed audit logs.

Results

Datasets

This study integrates three data axes under a unified, auditable framework: (i) longitudinal registry files for numerical modeling SRTR SAF and OPTN STAR1,2; (ii) authoritative policy and operations timelines SRTR PSR cadence and OPTN Policies used as executable constraints12; and (iii) controlled textual knowledge the Banff Central Repository, OPTN and UNOS policy manuals, and SRTR methodological notes consumed by KT-LLM via retrieval augmentation9. All registry data were accessed under data use agreements (DUA), and textual sources served as the single authoritative knowledge base with versioning and provenance9.

SAF provides recipient and graft level longitudinal follow-up structured around the TRF schedule at 6 months post-transplant, 1 year, and annually thereafter until re-transplant, death, or loss to follow-up10. For Agent-A (SRTR-MambaSurv), per-recipient sequences are aligned to the TRF grid and include dynamic laboratories, immunosuppression, adverse events, encounter metadata, and baseline donor covariates1. Center and calendar year identifiers are retained for stratified reporting9,12.

For Agent-B (OPTN-BlackClust), recipient-level OPTN STAR files aggregate candidate, donor, transplant, and post-transplant follow-up records to form end-to-end sequences spanning listing, transplant, and TRF-aligned follow-up. Analyses reproduce reported subgroup structure among Black recipients and support unsupervised subtype discovery with survival and competing risks endpoints.

Agent-C (Policy-Ops) operationalizes governance constraints with versioned provenance. SRTR PSRs are released semiannually with a conventional data freeze approximately six months prior; these dates guide center-level reconciliation12. OPTN Policies provide executable constraints, including TRF form due windows of 60 or 90 days and race-neutral eGFR rules for wait time credit. These anchors define admissible timelines, submission windows, and audit checks rather than labels.

The textual knowledge base is limited to the Banff Central Repository, OPTN and UNOS policy manuals, and SRTR methodological materials and PSR public pages9,12. Entries are compiled into versioned vocabularies and range tables for terminology normalization, retrieval, and rule-based validation by KT-LLM; documents are segmented and indexed with version, effective date, and section lineage to preserve provenance. No image data are used. Together, SAF and STAR sequences, PSR and OPTN timelines, and Banff, OPTN, and SRTR texts provide a consistent substrate for Agent-A survival and competing risks modeling, Agent-B unsupervised subtype discovery in the 2015–2019 STAR cohort, and Agent-C executable rule checks with sentence-level provenance. We analyze kidney transplants recorded between 2015 and 2019. Eligibility requires a transplant baseline and at least one follow-up on the TRF grid. Recipient timelines are administratively censored at the last known contact or at the study cutoff and are additionally truncated at the applicable program-specific report (PSR) freeze date for the evaluation period. Center and calendar year tags are retained as factors for partitioning and stability checks.

Evaluation metrics

Evaluation is performed on the TRF-aligned discrete time grid using cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) for graft loss and death. Discrimination is summarized with Harrell’s C-index using inverse probability of censoring weighting (IPCW) for right censoring, and calibration accuracy with the Brier score and its horizon average, the integrated Brier score (IBS). Groupwise comparisons across strata or discovered subtypes use Gray’s test for CIFs; when a single number effect is needed, we report Fine Gray subdistribution hazard ratios. All survival metrics are reported on prespecified horizons.

All metrics are computed on histories that are truncated at the evaluation window’s PSR freeze date so that estimation and reporting share the same clock. Left truncation and right censoring are handled under the stated IPCW constructions with the time axis aligned to the TRF grid.

Recipient level embeddings are clustered and assessed with (i) silhouette for cohesion/separation; (ii) Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and normalized mutual information (NMI) for agreement with alternative partitions; and (iii) bootstrap Jaccard for label stability across resamples. The number of clusters K is chosen via consensus clustering by inspecting the consensus CDF and the Delta area curve, favoring the smallest K beyond which gains plateau. All summaries include resampling uncertainty.

Adherence to policy timelines is summarized by the center level on time rate and median lateness; executable rules are evaluated with rule concordance against an independently verified audit subset. For retrieval augmented answers, we report evidence coverage and citation hit rate on structured checklist items. Governance and RAG metrics are aggregated by center and period with stratified summaries where appropriate.

For retrieval augmented answers, cite at one credits an answer when its top cited passage resolves to the governing clause for that item within the effective date window, and the rule F one metric is computed on structured checklist entries rather than rendered text templates.

Training details

All experiments used de-identified registry extracts under DUA, and image channels were not used. Splits were time-stratified and aligned to SRTR PSR freeze points; hyperparameters were chosen on a development split and then frozen; seeds, data vintages, policy and lexicon versions, and code hashes were logged. The knowledge base covered the Banff Central Repository, OPTN, and UNOS policies, including Policies 18 and 3.7, and SRTR methodological materials and PSR public pages. Documents were segmented with Lc from 256 to 384 and Sc from 64 to 128 while retaining version, effective date, and lineage. Dense retrieval used a domain-aligned encoder with candidate set k0 from 32 to 64 and a cross-encoder re-ranker to a final set k from 6 to 10. The orchestration model used a MedLLaVA language backbone with the vision branch disabled. Stage one froze the language backbone and trained the dense retriever and the cross encoder with contrastive objectives and hard negatives while all other parameters were frozen. Stage two kept the language backbone, the retriever, and the cross encoder frozen and unfroze only the language head and the checklist head for joint optimization. Closed-book dropout masked evidence for a subset of steps, and each answer required at least one citation. Decoding used beam search with length and coverage penalties. Optimization used AdamW with cosine decay and gradient clipping with early stopping on answer accuracy, citation hit rate, and structured field consistency. Decoding uses beam size b = 5, length penalty 0.8, coverage penalty weights γ = 0.60 and ω = 0.70, a sentence-level citation coverage threshold ρ = 0.70, and a confidence gate threshold τ = 0.25. Retrieval and re-ranking use segment length Lc = 384 and stride Sc = 96, a first stage candidate count k0 = 64, a re-ranked evidence count k = 8, and a terminology reweighting coefficient λ = 0.40. Optimization for the retriever and the cross encoder uses AdamW with initial learning rate 2 × 10−4, weight decay 0.01, and batch sizes 128 and 64; the language head and the structured checklist use AdamW with initial learning rate 1 × 10−4 and batch size 8; cosine decay scheduling and gradient clipping at 5.0 are applied, and early stopping monitors answer accuracy, citation hit rate, and structured field consistency. Agent A's survival training uses AdamW with an initial learning rate of 3 × 10−4, weight decay of 0.01, batch size 256, and gradient clipping at 5.0, with early stopping on validation negative log likelihood and IBS. All experiments run with random seeds 17, 29, and 41, and indexing, as well as batch sampling, follow the same seed order across runs.

For longitudinal outcome modeling, inputs followed the TRF grid at six months, one year, and then annually. Visits concatenated dynamic clinical variables with baseline donor and recipient covariates, explicit missingness indicators, and time delta features; numerical features used median and interquartile range scaling with Winsorization, and categorical fields were embedded. Sequences used a stacked Mamba state space backbone with residual connections and dropout, and center and year offsets were grouped as bias terms. The output layer produced a per-interval softmax over no event, graft loss, and death, and training used the discrete time negative log likelihood with label smoothing and focal weighting; calibration and stability regularizers acted on binned empirical rates and grouped logits. The Mamba backbone and the output layer were trained end-to-end with no frozen layers. Optimization used AdamW with cosine decay and clipping at five, with validation aligned to PSR freeze points and early stopping on negative log likelihood and IBS. Time out of sample evaluation held out the latest transplant year, and sensitivity analyses used center-stratified folds. Recipient level sequences were pooled with phase-specific attention and clustered by deep embedded clustering that pretrained a shallow autoencoder, initialized centers by k-means, and then fine tuned encoder and centers jointly under a DEC objective with IDEC-style reconstruction and an entropy balance term with a periodically refreshed target distribution. During clustering, the Mamba backbone was frozen, and only the autoencoder encoder and the cluster centers were updated. The number of clusters K was chosen by consensus clustering and the delta area criterion, and stability was assessed using bootstrap Jaccard indices and ARI or NMI with center and year stratified resampling.

The primary partition follows a calendar holdout: training uses transplants from 2015 to 2017, validation uses 2018, and test uses 2019. No recipient contributes observations across these temporal splits. For the test period, any record with timestamps later than the corresponding PSR freeze date is excluded from computation. Sensitivity analyses use center-stratified folds to assess transfer across sites while keeping each center’s records within a single fold per run. The retrieval index for KT-LLM is limited to sources whose effective dates precede the test freeze, and tool outputs that require dates or thresholds are computed only from data that satisfy the same cut.

KT-LLM comparison results

Table 1 reports a head-to-head comparison between KT-LLM Full and thirteen baselines, including BM2545, dense retrievers DPR, Contriever, and E539,46,47,48, the late interaction ranker ColBERTv249, RAG pipelines FiD and FiDO40, and domain LMs PubMedBERT, BioGPT, LLaVA-Med, and Med-PaLM 250,51,52. KT-LLM attains the top exact match and macro F1 on Banff-QA and Policy-QA, and also yields the highest evidence coverage and the best structured checklist consistency. Gains are largest on items that require clause-level grounding in OPTN and SRTR sources and on threshold checks that can be verified symbolically, which aligns with the joint text and structure objective and coverage-aware decoding. Replacing BM25 with learned dense retrieval improves answer accuracy and grounding. Contriever style and E5-style encoders raise first-stage recall over DPR on policy, and Banff clauses with heterogeneous wording, and a ColBERTv2 re-ranker further improves Hit@1 through fine-grained late interaction46,47,49. Closed-book biomedical LMs trail retrieval augmented systems on policy questions tied to current definitions or deadlines, and medical LVLMs narrow the gap on terminology yet lag on multi-clause reconciliation and numeric checks unless paired with explicit retrieval and a calculator.

Evidence attribution improves through a pointer distribution and a coverage penalty that raises the fraction of sentences with valid citations and reduces single-source reliance. Disabling the cross-encoder re-ranker lowers exact match and citation precision by making similarly worded clauses harder to disambiguate40,53. Ablations show three effects: disabling retrieval hurts most on numeric Policy-QA and on Banff items that depend on the latest wording, disabling the coverage penalty increases fluency while lowering citation rate, and re-enabling it restores multi-source coverage at a modest decoding time cost, and LoRA only tuning preserves stability across updates with small drops on paraphrastic items54. With dense retrieval and ColBERTv2 re-ranking, median end-to-end latency remains within interactive bounds, and the ranker reduces backtracking. Residual errors are boundary drift from closely versioned clauses, denotation ambiguity from rare synonyms or legacy acronyms, and arithmetic slips when upstream dates are incomplete. Under the stated protocol, KT-LLM couples higher answer quality with stronger grounding and more consistent structured outputs by aligning retrieval, attribution, and calculator tooling within a single audited stack.

Observed gains on Banff-QA and Policy-QA arise mainly from coverage targets that encourage aggregation across clauses, from the confidence gate that suppresses low confidence generations, and from the structured checklist that verifies thresholds and deadlines. We provide a brief qualitative error summary with one sentence illustration per pattern drawn from validation logs. Clause drift across close versions appears when answers cite a prior policy clause that still matches the query but uses the older due window of 60 days, and version stamps with coverage targets reduce this by preferring the clause with the latest effective date. Denotation ambiguity in threshold language appears when rare synonyms, such as induction level and induction intensity, are treated as distinct, and terminology-aware reweighting, together with checklist fields, aligns them to a single controlled term. Arithmetic slips appear when an upstream date is missing, and the calculator uses an implicit anchor. The checklist now requires an explicit anchor and returns a limited evidence message when the anchor is absent. We report all metrics with ninety-five percent confidence intervals, and we include paired permutation tests across seeds and folds for each comparison.

SRTR MambaSurv comparison results

Table 2 summarizes the head-to-head comparison on OPTN and SRTR discrete time survival with competing risks3,55,56,57, evaluated on held out centers and calendar windows. As shown in Table 2, across all metrics and both endpoints, SRTR–MambaSurv achieves the best overall performance. Concretely, it attains a C-index of 0.82 for Death and 0.80 for Graft Loss, surpassing the strongest deep survival baselines (Dynamic-DeepHit58: 0.79 and 0.77) by absolute margins of +0.03 on both endpoints. Discrimination at fixed horizons shows the same trend: time-dependent AUC28 at 1 year for Death is 0.84 (vs 0.82 for Dynamic DeepHit; for Graft Loss at 3 years it is 0.82 (vs 0.81). Calibration, measured by IBS30,31 over 0–5 years and macro averaged across endpoints, improves from 0.148 to 0.136 with SRTR–MambaSurv, and the visualized results are shown in Fig. 2.

Lines connect each model’s C-index across endpoints; line length encodes imbalance. a Per-model endpoint gap. b Joint threshold compliance on the calibration discrimination plane.Clinical isolines. IBS (0–5 years) = 0.16 and C-index (Death) = 0.78; shaded upper-left region meets both criteria. c Relative improvement waterfall (baseline = RSF-CR). Each bar shows the incremental change in a composite score mean of normalized C-index (Death), C-index (Graft), and inverted IBS (0–5 years) relative to RSF-CR. Red bars indicate models worse than baseline; blue bars indicate improvements; the thin gray line traces the running total, and the rightmost “Net” bar reports the aggregate change. d Fairness profile relative to RSF-CR. Radar axes denote subgroup gap categories. Radius encodes the ratio (r = gRSFCR/gmodel) of absolute gaps; the dashed ring at marks parity with RSF-CR. Values indicate smaller gaps than RSF-CR; values indicate larger gaps.

The confidence intervals for SRTR–MambaSurv generally do not overlap with those of classical semiparametric baselines, such as Fine-Gray3, CoxBoost59 on C-index and IBS, and show non-trivial separation from tree methods on at least one primary endpoint. Against the strongest deep baselines, the absolute C-index gains of +0.03 occur on both Death and Graft Loss, with tighter variability (std. ≤ 0.01) across three seeds. Together with the horizon-specific td-AUC gains and the consistent IBS reduction, these findings support that (i) encoding the TRF grid as a discrete time competing risks process, and (ii) employing a selective state space backbone36 to handle multi-year, irregular, and sparse observations, yield measurable advantages on held out centers and time windows. Finally, we note that absolute numbers vary across families in predictable ways: models optimized for proportional hazards tend to underperform at later horizons where non-proportional effects accumulate; tree models close some of the gap in td-AUC but remain less calibrated; and end to end deep discrete time methods are competitive yet still trail SRTR–MambaSurv, suggesting that long range sequence encoding and a multinomial interval hazard head jointly contribute to robustness in this registered, center-shifted setting.

To aggregate performance across discrimination and calibration and to make model level trade offs visually explicit, we summarize net improvements over the classical RSF-CR baseline with a composite waterfall as shown in Fig. 2. The plot shows that SRTR-MambaSurv delivers the largest positive shift, while classical proportional hazards families remain negative on the composite due to weaker later horizon discrimination and higher IBS, and strong deep survival baselines are competitive yet still trail MambaSurv.

Beyond point estimates, we examine equity-relevant behavior across clinically salient subgroups. A fairness profile radar, as shown in Fig. 2 summarizes absolute subgroup gaps relative to RSF-CR (baseline ring = 1.0), indicating consistently smaller gaps for SRTR-MambaSurv than for deep survival and classical baselines. This aligns with our study’s goal of coupling accuracy with monitoring of subgroup disparities under standardized, reproducible metrics.

OPTN BlackClust population clustering

We compare OPTN–BlackClust (Mamba + IDEC + Consensus) against classical partitioning, density, deep clustering without sequence backbones, and sequence-aware variants on OPTN STAR (2015–2019) Black recipients (Table 3). Unless otherwise noted, metrics are reported as mean ± std across repeated runs and bootstraps with the number of clusters selected by the consensus CDF criterion.

OPTN BlackClust attains the highest agreement and separation among all contenders, with NMI 0.58 and ARI 0.45, improving over the best non–sequence deep baselines (IDEC: 0.49 NMI, 0.37 ARI) by +0.09 NMI and +0.08 ARI, and over joint sequence aware Mamba + DEC (0.54 NMI, 0.41 ARI) by +0.04 and +0.04, respectively. Relative to classical tabular clustering (Agglomerative/Ward: 0.36 NMI, 0.27 ARI), the gains are larger (+0.22 NMI, +0.18 ARI). Silhouette follows the same trend, reaching 0.25 for OPTN BlackClust vs 0.23 (Mamba + DEC) and 0.21 (IDEC), indicating tighter, better separated partitions in the embedding space.

Consensus-based training markedly improves robustness. OPTN BlackClust yields the highest bootstrap Jaccard stability (0.79), exceeding Consensus–DEC (0.73) and Consensus–PAM (0.70). The margin over non-consensus DEC/IDEC (0.64–0.68) indicates that resampling and consensus aggregation effectively mitigate initialization sensitivity and feature subsample noise. Classical and density methods show substantially lower stability, consistent with their sensitivity to hyperparameters on heterogeneous registry data.

Between cluster outcome separation, assessed by the Gray test on graft loss CIFs with death as a competing event, is strongest for OPTN BlackClust (\(-{\log }_{10}p=4.6\)). This improves upon Mamba + DEC (3.9) and Consensus–DEC (3.6), and roughly doubles the signal relative to graph models. The pattern aligns with embedding quality, stronger sequence-aware representations, and consensus refinement translate into clearer prognostic stratification at the population level.

Using the same Mamba encoder but replacing the clustering stage with K-means reduces performance (NMI 0.42, ARI 0.31, Jaccard 0.62), underscoring the benefit of a joint deep clustering objective. Introducing the IDEC reconstruction term and consensus selection recovers both cluster compactness and stability, indicating that preserving local manifold structure and attenuating sampling variance are complementary to the long horizon sequence embedding.

As shown in Table 3, across agreement, separation, stability, and prognostic discrimination, OPTN BlackClust consistently ranks first. Gains are most pronounced when contrasted with classical tabular clustering and remain significant over strong deep baselines, including joint sequence-aware variants. These results support the design choice of combining a linear time Mamba backbone for longitudinal representation with an IDEC objective and consensus selection to deliver reproducible, clinically meaningful subtypes within the OPTN STAR Black recipient cohort.

Ablation results

Table 4 summarizes the incremental contribution of each component of the proposed system. Starting from the ablated baseline, KT-LLM attains a QA accuracy of 0.76, Cite@1 of 0.41, a rule-validation F1 of 0.68, and a survival C-index of 0.77. Enabling RAG yields a marked improvement in answerability and grounding, reflecting the benefit of evidence access for policy-heavy queries. Adding terminology-aware reweighting further lifts QA Acc to 0.83 and Cite@1 to 0.70, indicating that controlled vocabularies sharpen retrieval and re-ranking around domain terms.

Introducing the evidence pointer head with coverage constraint (CIT) primarily strengthens grounding: Cite@1 increases from 0.70 to 0.81 with a modest QA Acc gain to 0.84. As shown in Table 4, coupling the rule engine translates evidence into executable checks, substantially improving Rule F1 from 0.73 to 0.88 while maintaining strong QA Acc and Cite@1 (0.85 and 0.83, respectively). Finally, adding the discrete time competing risk head aligned to the TRF grid (CRH) improves survival discrimination from 0.77 to 0.81 without compromising QA or rule performance.

Overall, the full configuration achieves QA Acc 0.85, Cite@1 0.83, Rule F1 0.89, and C-index 0.81. The largest relative gains arise from adding RAG and Evidence pointer head with CIT, while OPS delivers the dominant improvement on rule-level consistency. Reported improvements are consistent across three seeds and typically exceed the corresponding standard deviations, supporting the robustness of each design choice.

Discussion

This work addresses the long-standing gap between structured follow-up sequences and text-defined rules in real-world KT by proposing and implementing an auditable, integrated solution. Dialog examples see Fig. 3, KT-LLM serves as the orchestration layer, connecting the Banff Central Repository, OPTN, and UNOS policies, and SRTR methodological materials through domain-constrained RAG within a unified knowledge source. On the sequence side, selective state-space models from the Mamba family encode multi-year, sparse, and non-equidistant TRF longitudinal data. On the operations side, Policy-Ops compiles into executable rules the form deadlines and unlock procedures in Policy 18, the Kidney Allocation System wait time provisions, and the recent race-neutral eGFR corrections, as well as the semiannual cadence of SRTR PSR and its data freeze points. In this way, question answering, risk prediction, clustering evidence, and compliance checks are quantified, recorded, and traced within a single system. As constraints from governance and authoritative sources, PSR public releases typically occur in January and July each year, with data cutoffs approximately six months prior; since 2023, Policy 18 has provided operational guidance for 60 and 90-day submission deadlines and post hoc unlock procedures; and the Banff Central Repository is designated as the current and complete online source superseding prior conference reports. Our system is designed around these verifiable boundary conditions and, methodologically, imposes an evidence-first, computable checklist generation discipline to mitigate hallucinations and definitional drift.

a Individual prognosis with discrete-time competing risks aligned to TRF. b Policy-Ops checks for PSR freeze and TRF deadlines with evidence anchored what-ifs. c Banff controlled terminology validation prior to diagnosis. d population subtyping with stability, outcome differences, and fairness profiles.

Unlike prior efforts centered on single-point model accuracy, we emphasize operational compliance and auditability. To balance representational power with deployability over multi-year follow-up, we adopt a linear time selective state space backbone for survival and competing risks tasks rather than a quadratic cost attention backbone; this choice is directly motivated by the time span and multi-center scale of TRF and by the input dependent state updates in Mamba. Further, at the output layer, we use a discrete time multinomial interval hazard parameterization so that the probabilities for no event, graft loss, and death are conserved within each interval, aggregating to an individual time axis via standard constructions of the CIFs and survival function. Evaluation follows the established toolkit of time-dependent AUC and IPCW-Brier to avoid biases that arise from metrics not designed for censored data. These design decisions are grounded in mature theory and practice: linear time sequence modeling in Mamba; discrete time and competing risks learning exemplified by Dynamic DeepHit; Heagerty’s ROC(t) framework; and IBS consistency analyses.

To study equity and population heterogeneity, we apply an end-to-end path of sequence embeddings, deep embedded clustering, and resampling-based agreement to unsupervised profiling of Black recipients within the OPTN STAR 2015–2019 window, and compare clusters under a competing risks framework using CIFs and survival contrasts. This aligns with prior findings of stable, clinically distinguishable phenotypes and outcome differences among Black recipients, while our implementation constrains the pipeline with a unified sequence backbone and a rule-governed audit chain so that subtype evidence, indicators, and timelines are presented coherently. To avoid subjective choices of the number of clusters, we select K by consensus clustering using CDF area criteria, and quantify stability with NMI and ARI; we also reference the SRTR PSR cadence to monitor cluster proportions across time windows, reducing the risk that freeze window and submission deadline effects are misread as structural drift. The underlying methods provide reproducible optimization steps and selection rules, ensuring statistical validity and engineering repeatability.

Empirically, within this study’s data and configuration, domain-constrained RAG in KT-LLM yields high evidence hit and coverage for answers, with strong agreement on time-sensitive items between source anchors and retrieved passages. Agent-A exhibits discriminative metrics and calibration with only modest out-of-time fluctuation, consistent with expectations for multi-year, multi-center deployment. Agent-B’s optimal K is supported by resampling consistency and silhouette style criteria and yields distinguishable CIFs contrasts under competing risks testing. Policy-Ops produces executable audit logs for wait time corrections, TRF submission timeliness, and Banff terminology conformance. These are study-specific observations subject to external validation; we therefore report training splits, metric definitions, implementation details, and versioned audit logs to facilitate independent checks. To avoid overstating estimates or in-sample effects, we describe findings explicitly as observations within this study rather than as general domain claims; factual background is restricted to official primary sources.

Several practical constraints merit discussion. First, although Mamba reduces inference and training cost relative to attention backbones of comparable capacity, pretraining, long-horizon tuning, and calibration remain computationally intensive at the recipient's year scale. Second, while RAG updates are parameter-free, their quality depends on source structure and fine-grained retriever re-ranker weighting. Third, the Policy-Ops rulebase must track OPTN policy updates, SRTR timelines, and the Banff repository; otherwise, stale rules risk text system mismatches. We mitigate these risks via versioned metadata and alignment to freeze points: the January to July PSR cadence with 6 month data freezes provides an external clock for training, evaluation and reconciliation; Policy 18’s 60 to 90 day limits and unlock procedures are directly parameterized as operators; and the Banff repository, as the authoritative source, is mapped unambiguously to value domains and controlled terminology. Continued advances in Mamba-style temporal modeling should further improve the computational accuracy trade-off under the joint challenges of very long follow-up, sparse observations, and cross-center heterogeneity.

This study has limitations. Data access and definitions are jointly constrained by DUA terms, submission cadence, and policy change; cross-source integration inevitably introduces selective missingness and center effects. Clinical interpretation of unsupervised subtypes requires additional external evidence across centers, particularly where historical granularity differs for Banff terms or immunologic markers. Competing risks testing and time-dependent AUC must honor censoring and left truncation assumptions; otherwise, differences may be overstated or errors understated. In our experiments, degradation is most visible for recipients with extremely sparse follow-up, centers with inconsistent Banff documentation, and policy clauses that rely on fields with chronic missingness, and KT-LLM often responds with cautious summaries or checklist items instead of confident scalar predictions in these settings. Finally, while Policy-Ops quantifies wait time, TRF timeliness, and terminology conformance, definitive clinical diagnoses or center-level interventions remain within the remit of clinical and quality teams, avoiding overreach in automation. Future work includes: rolling recalibration and out-of-time evaluation aligned to PSR freezes; coupling IDEC objectives with fairness constraints to bound errors for key subpopulations while preserving local structure; and enhancing RAG through evidence diversification and finer re-ranking, combined with structured operators and normalized terminology, to improve robustness across policy versions and page layout changes. Methodologically, integrating CIFs consistency calibration and uncertainty quantification into the training objective may shift the evidence prediction governance loop from ex post correction to endogenous constraints. The necessary technical and institutional ingredients are documented in SRTR and OPTN materials and the Banff repository, providing objective milestones for implementation. Furthermore, we explicitly scope claims about population subtypes to the STAR cohort of Black recipients under the current DUA, and extending the profiling pipeline to additional racial and ethnic groups and centers will be treated as follow-up work once comparable registries become accessible.

In sum, the unified framework of KT-LLM and the three agents demonstrates a feasible pathway to mechanistically couple follow-up sequences, textual rules, and governance cadence under registry data and authoritative texts. By front-loading evidence in generation, using a linear time backbone for sequences, and compiling policies and terminology into executable rules, we produce traceable question answering, calibratable survival prediction, and reproducible population clustering without moving beyond factual boundaries. Anchored to SRTR’s semiannual cadence and operational specifications in OPTN Policies, this “rules align data, governance clocks constrain models” paradigm offers a practical basis for multi-center, multi-era reproducibility assessments and equity monitoring with potential future applications including personalized follow up scheduling tailored to individual risk trajectories, real time cross center policy alignment to reduce practice variability, and proactive identification of subgroup specific care gaps to guide targeted interventions. It also underscores the need for sustained investment in external validation, rolling recalibration, and rulebase governance so that outputs remain consistent with evolving authoritative sources. Factual statements herein are limited to official SRTR and OPTN materials and the Banff repository; methodological references are to primary research, and directional effects or system behavior are reported strictly as observations under this study’s setting rather than general assertions.

Methods

System architecture overview

The system adopts a modular design with one primary model and three task-specific agents, each aligned to a distinct objective. The primary model is KT-LLM, built on the MedLLaVA medical language and vision framework. KT-LLM retrieves policy evidence through retrieval-augmented generation, abbreviated RAG, and returns evidence-anchored answers together with computable checklists. KT-LLM includes a terminology-aware reweighting module, abbreviated Terminology, to sharpen retrieval around controlled vocabularies, and an evidence pointer with a coverage constraint, abbreviated CIT, to strengthen grounding.

As shown in Fig. 4, the three agents operate in parallel. Agent-A, named SRTR-MambaSurv, performs long-term survival and graft outcome prediction for kidney transplant recipients and uses a discrete-time competing risk head aligned to the transplant recipient follow-up grid; this head is abbreviated CRH, and TRF denotes the follow-up grid. Agent-B, named OPTN-BlackClust, discovers unsupervised population subtypes among Black recipients in the OPTN STAR dataset. Agent-C, named Policy-Ops, conducts rule-based validation against OPTN policy requirements and Banff terminology; the rule engine is abbreviated OPS. These modules interoperate through structured interfaces. KT-LLM invokes the appropriate agent for computation or rules verification when needed, and the system synthesizes all outputs into a consolidated decision support and quality control report.

a Agent-A (SRTR-MambaSurv) encodes the recipient timeline with a linear time Mamba and predicts outcomes via two interchangeable heads: a discrete time cause-specific hazard head for competing risks and a DeepHit-style joint head. b Agent-B (OPTN-BlackClust) reproduces evidence on Black recipients: OPTN cohort selection, unsupervised clustering, and cluster profiling with covariate distributions and SHAP-like prototypes. c Agent-C (Policy-Ops) resolves Banff, OPTN, and SRTR terminology and executes a rule engine to produce a structured checklist that enforces definitions and reporting cadence across the system.

To align reasoning with governance cadence, the document index includes only Banff, OPTN, UNOS, and SRTR materials whose version stamps and effective dates are not later than the evaluation freeze for the period under study. During decoding, if an evidence candidate falls outside this window, it is discarded, and the system returns an evidence summary instead of a definitive conclusion.

Primary model: KT-LLM

KT-LLM serves as the orchestration and question answering core of the system. It adopts the language backbone of MedLLaVA with the text channel only. The knowledge sources are restricted to three authoritative corpora: the Banff online repository, OPTN and UNOS policy documents, and SRTR methodological materials. Using a RAG framework, answers and the associated computable checklists are explicitly bound to cited evidence segments, producing auditable outputs.

Knowledge access is restricted to Banff, OPTN, and SRTR materials. Retrieval uses a dense encoder followed by a cross-encoder re-ranker. Terminology-aware reweighting lifts passages that contain controlled terms from curated vocabularies so that domain wording is prioritized during re-ranking. Each sentence in the answer carries an explicit citation tag that points to a governing passage. A confidence gate returns an evidence summary when the best re-ranking score is below a set threshold. A coverage target encourages the use of multiple sources and reduces reliance on a single passage. For queries that involve thresholds or computable criteria, the system emits a structured checklist with item name, definition, formula, threshold, and source identifier. Training aligns retrieval and generation with a contrastive objective for retrieval, likelihood for text, and a light attribution regularizer that matches sentence-level citations to re-ranking scores.

For queries that involve thresholds or definitional criteria, KT-LLM produces a structured checklist with J items. Each item records five fields: name, definition, formula, threshold, and source_id. The field source_id points to an evidence passage mr. The field formula is executable. An operator h evaluates a formula on inputs v and returns a real value h(v). Textual and structured outputs are trained jointly as specified below.

The training objective is the sum of three components,

The retrieval contrastive loss (InfoNCE) is

where \(sim\) is inner product or cosine similarity, τT is a temperature, and \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{i}\) denotes hard negatives. The generation term combines text likelihood and structured penalties:

The loss for the structured checklist, denoted by \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{struct}\), aggregates three penalties over J items. For each item j, the model predicts a name and a threshold; both are supervised with cross-entropy against the gold labels. The executable field formula is compared by first evaluating the predicted and the reference expressions through the operator h on inputs v, then taking the ℓ1 distance between the two real values and weighting it by μ. The final objective is the sum of these three terms over all items.

The normalized re-ranking distribution is denoted by α, and the model sentence-level attention over passages by \(\widehat{\alpha }\). The attribution consistency regularizer matches them by

To strengthen reliance on retrieval and suppress hallucinations, a “closed-book dropout” schedule withholds evidence on a subset of training steps while enforcing at least one citation per answer template. At inference, a confidence gate and a coverage constraint are used: if sentence-level citation coverage falls below ρ or \({\max }_{m}{\widetilde{r}}_{m} < \tau\), the system returns an evidence summary and a checklist rather than a definitive conclusion.

For Banff terminology adjudication and OPTN metric computation, KT-LLM invokes domain tools via function calls. In discrete-time survival, if survival at time t and the interval hazard are required. For diagnostic queries that request a single-endpoint interval hazard, the tool computes a survival value by multiplying one minus the per-interval hazard over the grid and obtains the hazard from a linear score through a sigmoid. This head is used for tool-side evaluations and does not change the training objective of Agent-A, defined below.

Instruction tuning covers definitions, diagnostic criteria, policy specifications, and worked examples. Decoding uses beam search with length and coverage penalties; the latter is

where cov(m) is the fraction of output sentences citing passage m, ω is a minimum coverage threshold, and γ is a penalty weight. This encourages the use of multiple evidence sources rather than over-reliance on a single passage.

Implementation details are as follows: segment length Lc ∈ [256, 384] subword tokens; stride Sc ∈ [64, 128]; initial recall k0 ∈ [32, 64]; re-ranked evidence k ∈ [6, 10]. The retriever and cross-encoder share a vocabulary and are aligned with domain instructions. Training proceeds in two stages: first, freeze the language backbone to tune retrieval and re-ranking; second, unfreeze the language head for joint training of generation and structured outputs. AdamW with cosine-decay scheduling is used, and early stopping monitors answer accuracy, citation hit rate, and consistency of structured fields. The knowledge base supports hot updates: adding or revising documents requires only incremental encoding and index refresh, without retraining the primary model.

KT-LLM returns (i) a natural-language answer with sentence-level citation identifiers and version metadata, and (ii) a structured checklist ystruct containing item names, definitions, formulas, thresholds, and their evidence sources. Retrieval scores, re-ranking scores, citation distributions, and tool call logs are retained to form an auditable record suitable for quality control and independent replication.

Agent-A: SRTR-MambaSurv (survival prediction)

To align with the registry follow-up cadence and enable computable evaluation, we model two mutually exclusive endpoints, graft loss and patient death, in a discrete time and competing risks framework. For recipient i, let the observation grid be \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{i}=\{{t}_{i1},\ldots ,{t}_{i{J}_{i}}\}\) with ti1 = 0 at transplantation and subsequent nodes covering 6 months, 1 year, and yearly follow-ups thereafter. Time varying features at node j are denoted \({{\bf{x}}}_{ij}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{p}\), and baseline features \({{\bf{b}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{q}\). To encode irregular sampling, we include the interval length Δtij = tij − ti,j−1 and a set of Fourier time features ϕ(Δtij).

Let the event type set be \({\mathcal{K}}=\{1,2\}\), where k = 1 indicates graft loss and k = 2 indicates death; no event is treated as class 0. On each interval [tij, ti,j+1) we predict a multinomial risk vector

where πij,k is the discrete hazard of event type k within interval j, and πij,0 is the no-event probability. The survival and CIFs follow:

with Si(0) = 1. This multinomial head construction guarantees \({\sum }_{k\in {\mathcal{K}}}{\pi }_{ij,k} < 1\), and probability conservation in discrete time, avoiding overflow that can arise from independent sigmoids.

To accommodate long horizon, sparse, multi-center data, we construct at each node a composite input

where Ex, Eb are linear embeddings and mij is a missingness indicator aligned to xij. After linear projection, indicators are concatenated with numerical features to expose missing data patterns and mitigate imputation as certainty bias. Numerical variables are robustly scaled with Winsorization for heavy tails; categorical variables are one-hot or embedded and concatenated channel-wise.

Given the many years spent with long, sparse, and irregular sequences, we adopt a selective state space backbone to encode long dependencies in linear time. Let \({\widetilde{{\bf{X}}}}_{i}=[{\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}}_{i1},\ldots ,{\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}}_{i{J}_{i}}]\). After L stacked selective SSM blocks, we obtain time-point representations

To further inject temporal information, we add a gate-controlled additive bias g(Δtij) at each layer, and apply residual normalization and dropout for stability. Compared with self-attention, Mamba’s input-dependent state updates avoid quadratic complexity and make training feasible at the “recipients × years” scale.

On top of the encoder, a shared base with type-specific linear projections yields unnormalized scores and probabilities:

To absorb systematic drift, we include group biases for center and calendar year, Δij = δcenter(i) + δyear(ij), and update

Here, πij,0 is the no-event probability for interval j, ensuring that survival is the product of no-event probabilities across intervals. For tail interval discrimination, we use label smoothing and focal type reweighting

where wc reflects event rarity and γ ∈ [1, 2] downweights easy cases.

Let \(({\widetilde{T}}_{i},{\widetilde{\Delta }}_{i})\) denote the discretized terminal observation with \({\widetilde{T}}_{i}\in \{1,\ldots ,{J}_{i}\}\) and \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{i}\in \{0,1,2\}\) (0 for censoring). The individual likelihood under the discrete-time multinomial model is

Maximizing the log likelihood is equivalent to minimizing

To improve probability calibration and internal consistency under competing risks, we regularize \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{NLL}\) with two terms. First, for each time j, we align the model’s average output \({\overline{\pi }}_{j,c}\) with the empirical rate \({\widehat{p}}_{j,c}\) from equal frequency bins. Interval calibration aligns the batch-average predicted rate with the empirical rate on each interval and event by adding the squared difference and summing over all intervals and event types. Its overall influence is controlled by the global weight in the final objective.

Second, center year stability: group lasso style penalty on center year logits to attenuate overfit shifts:

The overall objective is

where Θ collects all trainable parameters. We optimize with AdamW, gradient clipping at 5.0, cosine learning-rate decay, and early stopping on validation NLL and integrated Brier (defined below).

Censoring is handled explicitly by \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{NLL}\) during training. For evaluation, the following quantities are computed from πij. Individual CIFs and survival follow the discrete-time constructions already defined above and are computed on the same TRF-aligned grid. Then, IBS for target event k at time j:

where Yk(j) = 1{event k occurredbyj} and ωj are IPCW weights constructed from an independent censoring estimator \(\widehat{G}(j)\) via

The IBS is

At last, C-index and time-dependent AUC are computed under Heagerty’s discrete-time framework using IPCW-adjusted comparable pairs; dynamic and cumulative definitions are reported accordingly.

Agent-B: OPTN-BlackClust (population clustering)

To identify stable recipient subtypes among Black kidney transplant recipients and to quantify phenotypic heterogeneity, we perform unsupervised profiling on OPTN STAR (2015–2019) recipient-level records. STAR is a restricted-access, quarterly updated dataset containing candidate, donor, and recipient follow-up information obtainable via a DUA. This access pathway permits methodological implementation and independent replication. To unify the heterogeneous longitudinal process “waitlist → transplant → post-transplant follow-up,” we construct for each recipient the event sequence

Here, xij aggregates clinical, immunologic, and process variables at time tij. To handle irregular sampling and cross-center heterogeneity, we include the interval length Δtij = tij − ti,j−1 and source metadata as explicit covariates.

For robustness on long, sparse, non-equidistant registries, we adopt a selective state space model (Mamba) as the encoder backbone. After linear embeddings for numeric, categorical, missingness, and time features, each node yields a vector \({\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}}_{ij}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{in}}\). Stacking L selective SSM blocks produces time point representations

To expose heterogeneous dynamics between the waitlist and post-transplant phases, the sequence is partitioned by a scheduling variable into a waitlist segment \({{\mathcal{W}}}_{i}\) and a post-transplant segment \({{\mathcal{P}}}_{i}\). We apply phase wise attention pooling:

The recipient level embedding concatenates both phases:

Mamba’s input-dependent state updates provide linear time inference and preserve representation quality over long horizons, enabling training and deployment at STAR scale.

To obtain stable partitions in the embedding space, we adopt Deep Embedded Clustering (DEC) as the primary loss and include an IDEC-style reconstruction constraint to preserve local structure. Let \({\{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}_{k}\}}_{k=1}^{K}\) be learnable cluster centers. The soft assignment for the recipient i uses a Student-t kernel:

Let fk = ∑i qik denote cluster frequencies. The sharpened target distribution is

The DEC clustering loss is

To discourage representation drift, we add a shallow autoencoder with encoder Encϕ( ⋅ ) and decoder Decψ( ⋅ ) sharing the bottleneck with clustering. We reconstruct a unified patient feature vector with an encoder and a decoder parameterized by ϕ and ψ. The input vector ui combines robust numerical summaries, categorical embeddings, and temporal descriptors. The reconstruction is denoted by \({\widehat{{\bf{u}}}}_{i}\). This autoencoder is used to preserve local structure and to provide a stable representation for downstream modules. and minimize the reconstruction error

The joint objective is

where λrec controls local-structure preservation, and λcent regularizes center norms. Training proceeds in three stages: (i) freeze Mamba and pretrain the autoencoder; (ii) initialize {μk} with K-means on {ri}; (iii) jointly fine-tune DEC and IDEC, periodically recomputing P from Q every T steps and updating centers and encoder parameters. To prevent cluster collapse, we introduce a balance regularizer on cluster usage:

and optimize \({\mathcal{J}}+{{\mathcal{R}}}_{bal}\).

Given recipient embeddings \({\{{r}_{i}\}}_{i=1}^{N}\) and centers \({\{{\mu }_{k}\}}_{k=1}^{K}\), soft assignments use qik and the sharpened target pik with refresh period Tref. The joint objective is

where \(H(\overline{q})\) is the entropy of the average assignment to encourage non-collapsed usage. Freeze the sequence encoder. Pretrain the shallow autoencoder. Initialize {μk} by k-means over {ri}. For t = 1, … update the encoder and centers by AdamW on J with mini-batches. Every Tref step recompute P = {pik} from the current Q = {qik}. Compute \(\overline{q}\) per batch and add \(\beta \,H(\overline{q})\) to the loss. This term is zero when usage is uniform and penalizes collapse. Stop when the relative change of J averaged over the last M steps falls below ϵJ or when the Jaccard index between consecutive hard partitions exceeds τJac for M checks. Tref = 200 update steps, λrec = 0.1, λcent = 10−4, β = 0.1, M = 5, ϵJ = 10−3, τJac = 0.99.

Run the inner loop on S resamples of recipients and variables for each candidate K in a grid. For each run s obtain a partition z(s). Build a consensus matrix C with entries

collect its off-diagonal values, and compute the CDF. Let A(K) be the AUC of this CDF. Choose the smallest K⋆ such that ΔA(K) = A(K) − A(K − 1) is below a preset margin δ. We set S = 50 and δ = 0.01 by default. Stability is reported with bootstrap Jaccard together with NMI and ARI under center- and year-stratified resampling.

Compared with Improved DEC with reconstruction, OPTN-BlackClust adds a sequence backbone for long, irregular timelines, an explicit entropy balance on average usage, and an external consensus selection with resampling and CDF-area control. HiCL families rely on contrastive separation in latent space with instance-pair design and often exploit hierarchical relations. Our method does not introduce negative pairs or hierarchical contrast and instead couples IDEC with consensus-based model selection. The loss is KL on P∥Q plus reconstruction and entropy balance, optimized with a periodic target refresh. Convergence is declared by objective stabilization and partition stability rather than a contrastive temperature schedule.

To select the number of clusters and assess stability, we employ a consensus framework. For each candidate \(K\in {{\mathcal{K}}}_{grid}\), we subsample recipients and features, train DEC and IDEC, and obtain partitions. The consensus matrix C and its CDF curve are computed across runs; K⋆ is chosen by the CDF gain and Δ-area criterion. Under bootstrap resampling, we report the cluster-level Jaccard index

together with NMI and ARI means and confidence intervals, providing quantitative evidence of reproducibility.

With K⋆ fixed, we compute robust within-cluster summaries for each feature and identify a prototype recipient (closest to μk by ℓ2 distance) per cluster \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{k}\). To mitigate year confounding during profiling, we use stratified weights

For patient survival and graft survival, we draw Kaplan–Meier curves by cluster and conduct log-rank tests. For competing risk endpoints, we compute cluster-level CIFs and apply Gray’s test for multi-cluster comparisons; where appropriate, Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard ratios are reported as effect sizes. All comparisons are repeated under stratified resampling over centers and years to assess robustness.

Agent-C: policy-Ops (rule checking)

Agent-C converts the policy terminology timeline axis from static text into executable constraints. It encodes (i) OPTN and UNOS data submission and wait time rules, (ii) the semiannual cadence of SRTR PSR, and (iii) Banff terminology and lesion-score dictionaries as a set of computable rules. Inputs come from registry data and pathology records; outputs are auditable per-rule results, numeric indicators, and evidence anchors. Policy clauses and submission timelines follow the current OPTN Policies, including Policy 18 for TRF deadlines; the PSR cadence follows SRTR official timelines and technical notes; Banff terminology follows the Central Repository as the authoritative source.

Each rule is represented by a trigger that activates it, a collection of decidable predicates, and an action that defines the disposition. Execution logs include the policy identifier, version tag, effective date, and a source link.

We define common time operators to reduce ambiguity. Absolute time t is aligned to a unified day boundary; time difference is

The follow-up grid uses six months, one year, and then yearly intervals. For a transplant at time t0, expected TRF generation times add grid offsets to t0. Each form has a due date defined by adding a fixed window of sixty or ninety days to the corresponding generation time. Next, a submission is on time when the recorded submission date does not exceed the due date for that follow-up. Late cases record the delay magnitude as the difference between the due date and the submission date.

To detect deviations from the intended cadence, define the grid offset for follow-up j

and the successive interval deviation

Alerts are raised when

with default thresholds τϵ = 30 days and τη = 60 days. All computations cross-checked against the current Policies and Policy 18 tables are versioned in the audit log.

A candidate’s credited wait time Wi is anchored to the earliest qualifying date \({t}_{i}^{\star }\):

Dialysis-based time accrues from dialysis start; eGFR/CrCl ≤ 20 does not retro credit before listing and accrues from the date the threshold is met, and registration is complete. The credited time at t is

From 2024 onward, programs must evaluate whether historical race-inclusive eGFR delayed eligibility. The eligibility predicate is

If satisfied, a modification request can be filed using race-neutral eGFR as evidence and including required attestations. When the predicate is detected, Agent-C emits a task with the clause identifier and timestamp.

PSR are publicly released semiannually (January and July) and typically reflects data frozen approximately six months prior. Given a publication date tPSR, define

Let [topen, tdeadline] denote the correction window. Readiness is asserted if and only if a case is marked ready for PSR, with all forms requiring correction submitted by their respective deadlines. For each such form f, the submission time satisfies tsub(f) ≤ tdeadline. If ¬ psr_ready, Agent-C reports potentially impactful missing updates by form and lateness, aligning training/evaluation cutoffs with SRTR reporting scope.

Banff lesion items are compiled into a machine-readable vocabulary and range tables. Let \({\mathcal{L}}\) denote items such as {i, t, v, g, ptc, cg, ci, ct, cv, mm, ah, …}. For each \(\ell \in {\mathcal{L}}\), define an admissible domain Ωℓ and a format map Πℓ. The validation predicate is

Free text terminology is normalized via

Key adjuncts are standardized as

A diagnostic summary is produced only when every required lesion entry passes the validity check, and the C4d status is known. Concretely, each ℓ in the required set must satisfy valid_lesion(ℓ, xℓ), and C4d status must not be unknown. Since Banff diagnostic categories integrate multiple clinical and immunologic elements, Agent-C does not provide a final diagnosis. Instead, it ensures compliance with value and format requirements, anchors terms and scores to the versioned repository, and preserves consistency and traceability.

Each execution returns a structured record that contains an identifier, the target entity, the rule name, the status, numeric values and margins to thresholds, and the audit metadata with evidence anchors.

With KT-LLM, rules are invoked via policy_ops.compute(query, payload), where payload includes candidate IDs, form timestamps, pathology vectors, and context.

With Agent-A: when a user requests individual survival or CIFs at time t, KT-LLM aggregates Agent-A’s discrete hazards {πj,⋅} and jointly displays results with TRF grid compliance.

With Agent-B: when reporting cluster prototypes, Policy-Ops verifies that prototype records comply with terminology and timeline constraints, avoiding contaminated exemplars.

The rulebase is versioned by source. When OPTN updates Policy 18 or allocation policies, SRTR revises PSR timelines, or Banff updates repository entries, only the corresponding rules and metadata are incrementally updated. KT-LLM’s RAG index hot updates immediately; retraining of the primary model is not required.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. All data used are de-identified and publicly released by their providers under the respective data-use policies; no new human subjects data were collected.

Data availability

Registry files for numerical modeling: (1) SRTR Standard Analysis Files (SAFs): https://www.srtr.org/requesting-srtr-data/about-srtr-standard-analysis-files/; SAF Data Dictionary: https://www.srtr.org/requesting-srtr-data/saf-data-dictionary/; Data request/DUA:https://www.srtr.org/requesting-srtr-data/data-requests/. (2) OPTN STAR files: overview/request page https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/request-data/; STAR File Data Dictionary (xlsx):https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1swp2gge/star-file-data-dictionary.xlsx. Authoritative policy and operations timelines (executable constraints): (1) SRTR PSRs public page: https://www.srtr.org/reports/program-specific-reports/. (2) PSR reporting timeline (cadence): https://www.srtr.org/reports/psr-reporting-timeline/. Controlled textual knowledge for retrieval augmentation: (1) Banff Central Repository (renal allograft pathology): https://banfffoundation.org/central-repository-for-banff-classification-resources-3/. (2) OPTN Policies main page: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/policies-bylaws/policies/; Current OPTN Policies (PDF): https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/eavh5bf3/optnpolicies.pdf. (3) Race-neutral eGFR (policy background & FAQs): https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/policies-bylaws/a-closer-look/waiting-time-modifications-for-candidates-affected-by-race-inclusive-egfr-calculations/for-professionals-faqs-about-egfr-waiting-time-modifications/. (4) SRTR methodological notes (PSR technical methods): https://www.srtr.org/about-the-data/technical-methods-for-the-program-specific-reports/. This study's experiments were conducted in a Python 3.10 environment using the PyTorch framework (v2.2, CUDA 12.0, cuDNN 8.9) running on 4 NVIDIA A100 GPUs (80 GB) within a Linux system. The Mamba backbone for vertical modeling relies on mamba-ssm (v1.1.1), while retrieval and reordering modules are based on Sentence-Transformers (v2.7.0). Clustering-related workflows are built using scikit-learn (v1.3.2) and custom PyTorch modules. Evaluation metrics employ custom implementations compliant with transplant registry standards. Gradient clipping, cosine decay scheduling, and AdamW optimization utilize PyTorch's native tools. The complete training and inference scripts for KT-LLM have been open-sourced on GitHub https://anonymous.4open.science/r/KT-LLM_v1-7F53/README.md.

Code availability

This study’s experiments were conducted in a Python 3.10 environment using the PyTorch framework (v2.2, CUDA 12.0, cuDNN 8.9) running on 4 NVIDIA A100 GPUs (80 GB) within a Linux system. The Mamba backbone for vertical modeling relies on mamba-ssm (v1.1.1), while retrieval and reordering modules are based on Sentence-Transformers (v2.7.0). Clustering-related workflows are built using scikit-learn (v1.3.2) and custom PyTorch modules; Evaluation metrics employ custom implementations compliant with transplant registry standards. Gradient clipping, cosine decay scheduling, and AdamW optimization utilize PyTorch’s native tools. The complete training and inference scripts for KT-LLM have been open-sourced on GitHub https://anonymous.4open.science/r/KT-LLM_v1-7F53/README.md.

References

Leppke, S. et al. Scientific registry of transplant recipients: collecting, analyzing, and reporting data on transplantation in the United States. Transplant. Rev. 27, 50–56 (2013).

Spadaccini, N., Hall, S. R. & Castleden, I. R. Relational expressions in star file dictionaries. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 40, 1289–1301 (2000).

Fine, J. P. & Gray, R. J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 496–509 (1999).

Roufosse, C. et al. A 2018 reference guide to the Banff classification of renal allograft pathology. Transplantation 102, 1795–1814 (2018).

Loupy, A. et al. The Banff 2019 kidney meeting report (i): updates on and clarification of criteria for T cell–and antibody-mediated rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 20, 2318–2331 (2020).

Naesens, M. et al. The Banff 2022 kidney meeting report: reappraisal of microvascular inflammation and the role of biopsy-based transcript diagnostics. Am. J. Transplant. 24, 338–349 (2024).

Israni, A. Optn/srtr 2020 annual data report: introduction. Am. J. Transplant. 22, 11–20 (2022).

Gupta, A. et al. Program-specific reports: a guide to the debate. Transplantation 99, 1109–1112 (2015).

Scientific Registry Of Transplant Recipients. Technical Methods for the Program-Specific Reports (SRTR, 2022).

Myaskovsky, L. et al. Kidney transplant fast track and likelihood of waitlisting and transplant: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 185, 499–509 (2025).

Singh, T. P. et al. Graft survival in primary thoracic organ transplant recipients: A special report from the International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 42, 1321–1333 (2023).

VanWagner, L. B. & Skaro, A. I. Program-specific reports: implications and impact on program behavior. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 18, 210–215 (2013).

Loupy, A., Mengel, M. & Haas, M. Thirty years of the international banff classification for allograft pathology: the past, present, and future of kidney transplant diagnostics. Kidney Int. 101, 678–691 (2022).

Haas, M. et al. The Banff 2017 kidney meeting report: Revised diagnostic criteria for chronic active T cell-mediated rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, and prospects for integrative endpoints for next-generation clinical trials. Am. J. Transplant. 18, 293–307 (2018).

Farris, A. B. et al. Banff digital pathology working group: going digital in transplant pathology. Am. J. Transplant. 20, 2392–2399 (2020).

Farris, A. B. et al. Banff digital pathology working group: image bank, artificial intelligence algorithm, and challenge trial developments. Transpl. Int. 36, 11783 (2023).

Delgado, C. et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 2994–3015 (2021).

Inker, L. A. et al. New creatinine-and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1737–1749 (2021).

Thongprayoon, C. et al. Use of machine learning consensus clustering to identify distinct subtypes of black kidney transplant recipients and associated outcomes. JAMA Surg. 157, e221286–e221286 (2022).

For Organ Sharing (UNOS), U. N. et al. Implementation Notice: Requirement for Race-Neutral eGFR Formulas in Effect (UNOS, 2023).

Fallahzadeh, M. A. et al. Performance of race-neutral eGFR equations in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 31, 170–180 (2025).

Procurement, O. & Network, T. Modify Waiting Time for Candidates Affected by Race-Inclusive Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) Calculations (HRSA, 2023).

Procurement, O. & Network, T. Waiting Time Modifications for Candidates Affected by Race-Inclusive eGFR Calculations (HRSA, 2024).

Cox, D. R. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 34, 187–202 (1972).

Ishwaran, H., Kogalur, U. B., Blackstone, E. H. & Lauer, M. S. Random survival forests (2008).

Lee, C., Zame, W., Yoon, J. & Van Der Schaar, M. Deephit: a deep learning approach to survival analysis with competing risks. In Proc. the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 32 (PKP Publishing Services Network, 2018).

Katzman, J. L. et al. Deepsurv: personalized treatment recommender system using a Cox proportional hazards deep neural network. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18, 24 (2018).

Heagerty, P. J., Lumley, T. & Pepe, M. S. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 56, 337–344 (2000).

Heagerty, P. J. & Zheng, Y. Survival model predictive accuracy and ROC curves. Biometrics 61, 92–105 (2005).

Graf, E., Schmoor, C., Sauerbrei, W. & Schumacher, M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat. Med. 18, 2529–2545 (1999).

Gerds, T. A. & Schumacher, M. Consistent estimation of the expected Brier score in general survival models with right-censored event times. Biometrical J. 48, 1029–1040 (2006).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS, 2017).

Dai, Z. et al. Transformer-xl: attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL, 2019).

Zaheer, M. et al. Big Bird: transformers for longer sequences. Comput. Sci. 33, 17283–17297 (2020).