Abstract

Early detection of cognitive impairment is limited by traditional screening tools and resource constraints. We developed two large language model workflows for identifying cognitive concerns from clinical notes: (1) an expert-driven workflow with iterative prompt refinement across three LLMs (LLaMA 3.1 8B, LLaMA 3.2 3B, Med42 v2 8B), and (2) an autonomous agentic workflow coordinating five specialized agents for prompt optimization. Using Llama3.1, we optimized on a balanced refinement dataset and validated on an independent dataset reflecting real-world prevalence. The agentic workflow achieved comparable validation performance (F1 = 0.74 vs. 0.81) and superior refinement results (0.93 vs. 0.87) relative to the expert-driven workflow. Sensitivity decreased from 0.91 to 0.62 between datasets, demonstrating the impact of prevalence shift on generalizability. Expert re-adjudication revealed 44% of apparent false negatives reflected clinically appropriate reasoning. These findings demonstrate that autonomous agentic systems can approach expert-level performance while maintaining interpretability, offering scalable clinical decision supports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) have fundamentally transformed our capacity to parse the subtle linguistic patterns that herald cognitive decline, offering unprecedented precision in language generation and contextual understanding.1,2,3,4 These computational breakthroughs promise to revolutionize clinical workflows by systematically processing and interpreting the complex narrative threads woven throughout medical documentation.5,6

Clinical notes contain an undercurrent of linguistic shifts, hesitations in word retrieval, narrative disorganization, and family concerns, often noted in passing. When harnessed thoughtfully, LLMs offer the potential for scalable, systematic screening of cognitive impairment embedded in this everyday clinical text.7,8 Early identification opens therapeutic windows for FDA-approved interventions like lecanemab and aducanumab, whose efficacy depends critically on timely administration.7,9,10

Despite the need for timely screening, traditional instruments like the Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment remain constrained by in-person delivery, educational bias, and time-intensive administration.11,12,13 LLMs offer an algorithmic solution by analyzing the linguistic architecture of clinical documentation, parsing syntax, semantics, and lexical diversity to detect early computational signatures of cognitive impairment.14,15 Their seamless integration with telehealth platforms extends access to underserved populations.16,17

The technical challenge lies in optimization. Prompt engineering, the careful crafting of LLM instructions, emerges as the critical determinant of clinical accuracy. In high-stakes medical applications, subtle phrasing variations can yield inconsistent classifications.18 Manual refinement demands extensive clinical expertise and iterative testing, difficult to scale across healthcare settings.

Existing automated approaches, such as reinforcement learning, gradient-based tuning,19,20 and black-box search (e.g., AutoPrompt,21 RLHF22), suffer from computational opacity and clinical inflexibility, often producing statistically effective but clinically impractical solutions.

An emerging solution lies in agentic AI systems, autonomous agents that can replicate specialized reasoning within defined domains.23,24 Rather than relying on opaque algorithms, agentic workflows create transparent processes that can complement clinical reasoning patterns.

Here, we introduce the first fully autonomous agentic LLM workflow for cognitive concern detection, an end-to-end system requiring zero human input after deployment. It coordinates five dedicated agents focused on sensitivity enhancement, specificity refinement and clinical reasoning synthesis. The system iteratively refines itself through transparent agent interactions while maintaining auditability and clinical relevance.

We compare this fully autonomous workflow to expert-guided optimization strategies, demonstrating that agentic AI can match, and in some dimensions exceed, human-crafted prompts. Through expert re-adjudication of disagreement cases, we suggest that the system may outperform initial human annotations in certain instances, proposing a future where AI not only supports clinical work but also facilitates transparent, data-driven self-improvement.

Results

Cohort characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the two datasets. The refinement dataset, comprising 2228 clinical notes from 100 patients, established our developmental foundation with patients averaging 77.9 years and 60% female representation. The independent validation cohort (1110 notes, 100 patients) maintained demographic consistency with a mean age of 76.1 years and a 59% female composition.

Statistical comparison revealed no significant differences between datasets in age (p = 0.072), sex distribution (p = 1.000), racial composition (p = 0.340), or ethnic group representation (p = 1.000), confirming demographic balance. By design, cognitive concerns were present in 50% of refinement dataset patients versus 33% of validation dataset patients (p = 0.022 < 0.05), which indicates a statistically significant difference. This intentional oversampling in the refinement dataset provided balanced class exposure during model development, while the validation dataset preserved real-world prevalence for assessing generalizability under natural clinical conditions.

Performance before expert re-adjudication

The iterative expert-driven workflow generated three prompts, XP1–XP3 (detailed in Supplementary Table 1), and demonstrated the power of human clinical expertise in guiding computational behavior. Llama3.1 exhibited the most dramatic transformation, evolving from a initially poor specificity (0.08) to achieving a high specificity of 0.91 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.86–0.96), an F1 score of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.87–0.95) and a sensitivity of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.86–0.96), on the refinement dataset by XP3 (detailed in Supplementary Table 2).

On the validation dataset (detailed in Supplementary Table 3), the expert-driven workflow reached an F1 score of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.80–0.83), with sensitivity of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.72–0.75) and specificity of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.95–0.97), performance that reflected expert clinicians’ emphasis on minimizing false positives while maintaining reasonable detection rates.

In contrast, Llama3.2 and Med42 demonstrated the fragility of smaller or specialized models under iterative refinement. Despite its clinical training, Med42 maintained high specificity but suffered progressive sensitivity degradation, ultimately failing to detect cognitive concerns that expert reviewers deemed clinically significant.

The autonomous agentic LLM workflow revealed a different optimization trajectory (AP1–AP3, detailed in Supplementary Table 1), achieving clinical-grade performance through pure computational optimization. Across its refinement steps, specificity improved from 0.08 (95% CI: 0.02–0.14) to 0.94 (95% CI: 0.90–0.98), while the F1 score increased from 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.70) to 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85–0.92) on the refinement dataset, as shown in Supplementary Table 4. However, sensitivity decreased from perfect, 1.00 (95% CI: 1.00–1.00), to 0.84 (95% CI: 0.79–0.89).

On the validation dataset (Supplementary Table 5), the final autonomous prompt (AP3) achieved an F1 score of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.62–0.68), with specificity of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–1.00) but reduced sensitivity of 0.50 (95% CI: 0.48–0.52). The profile showed that autonomous computational optimization can match expert specificity, even with much less information than human reviewers.

To benchmark LLM performance, we also developed and evaluated a Lexicon-natural language processing (NLP) approach. As shown in Supplementary Table 6, its performance was modest, achieving on the refinement dataset a sensitivity of 0.90, a specificity of 0.78, an F1 score of 0.85, and an accuracy of 0.84. On the validation dataset, performance declined to a sensitivity of 0.73, specificity of 0.75, F1 score of 0.65, and accuracy of 0.74. These results underscore the benefit of our iterative refinement workflows over static NLP approaches.

We measured token usage and execution time across all agents and iterations within the agentic workflow on the prompt refinement dataset. As shown in Supplementary Table 7, token consumption and runtime varied substantially by agent role and iteration stage. The Specialist agent maintained consistent efficiency across iterations, with a mean token cost of approximately 3000 tokens and runtime of 4–5 s per iteration. The Specificity improver and Sensitivity improver agents required moderately higher computational resources (range: 2911–9603 tokens; 4.38–15.81 s). The Summarizer agents exhibited the highest token consumption and processing time (range: 5928-31,680 tokens;14.55–31.74 s), reflecting their larger language-generation tasks. Overall, these measurements illustrate how resource demands scale with agent function and iteration complexity within the workflow.

McNemar’s test on the initial refinement dataset revealed no significant differences in classification patterns between the fully autonomous agentic (AP3) and expert-driven (XP3) workflows (χ² = 0.00, p = 1.000).

Computational-human disagreement

The validation dataset revealed patterns of computational-human disagreement that challenged traditional assumptions about AI accuracy. Perfect concordance emerged for all positive cases (100% specificity agreement), yet 16 cases (16%) appeared as false negatives, instances where the autonomous agentic LLM workflow classified patients as negative while human annotators had identified cognitive concerns.

The refinement dataset showed similar disagreement patterns in 12 cases (12% of patients): 2 cases where autonomous agents identified cognitive concerns missed by expert chart reviewers, and 10 cases where computational analysis failed to detect human-identified cognitive concerns.

The systematic expert re-adjudication process unveiled that our autonomous agentic LLM workflow frequently demonstrated superior clinical reasoning compared to initial human annotations. Expert re-adjudication confirmed that human annotations were correct in two cases where the agents incorrectly identified cognitive concerns as present. However, in seven of the ten cases where the agentic LLM workflow had appeared to miss cognitive concerns, re-adjudication sided with the autonomous computational assessment. This finding suggests that autonomous agents demonstrated screening advantages over initial human annotation in 58% (7 out of 12) of disagreement cases. Among the 16 false negatives, expert re-adjudication revealed that the autonomous agentic LLM workflow was clinically correct in 7 cases (44%), demonstrating the system’s strength in systematically ruling out cognitive concerns based on available evidence.

Among nine cases from the validation dataset where the autonomous agentic LLM workflow was truly incorrect, expert analysis revealed systematic patterns. Four cases reflected documentation structure limitations where cognitive concerns appeared only in problem list entries without supporting clinical narrative, and information architecture that challenged computational parsing. Two cases involved domain knowledge gaps in which the autonomous system’s clinical knowledge base failed to recognize aphasia and limited health insight as cognitive concern indicators. The remaining three cases stemmed from ambiguous autonomous agent outputs containing contradictory classification signals, highlighting the need for more precise computational decision protocols.

Together, the autonomous agentic LLM workflow excelled at analyzing comprehensive clinical narratives, history of present illness, examination findings, and clinical reasoning, but struggled with isolated data points lacking clinical context.

Post re-adjudication performance

Across the refinement dataset (Supplementary Table 8), the post-re-adjudication expert-driven workflow achieved steady performance improvements. Llama3.1 emerged as the best performer (perfect sensitivity 1.00, poor specificity 0.07) through progressive refinement cycles to achieve balanced performance by XP3: F1 score 0.87, accuracy 0.88, sensitivity 0.84, specificity 0.91. Other models showed less favorable trajectories, with Llama3.2 and Med42 ultimately overfitting to specificity at the expense of clinical sensitivity.

The post-re-adjudication results from the validation dataset (Table 2) confirmed Llama3.1’s superiority under expert guidance, achieving the highest F1 score (0.81; 95% CI: 0.79–0.83) and accuracy (0.90; 95% CI: 0.89–0.91) among all evaluated models.

The autonomous agentic LLM workflow demonstrated a distinct optimization pattern that revealed the power of pure computational collaboration. Table 3 presents the autonomous system’s post-re-adjudication performance on the validation dataset: F1 score 0.74 (95% CI: 0.68–0.80), sensitivity 0.62 (95% CI: 0.58–0.66), specificity 0.98 (95% CI: 0.95–1.00), and accuracy 0.88 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91). This performance demonstrates that autonomous AI agents can reach near-expert-level clinical decision-making through pure algorithmic collaboration.

As shown in Supplementary Table 10, on the refinement dataset, the Lexicon NLP approach achieved a sensitivity of 0.91, a specificity of 0.84, an F1 score of 0.86, and an accuracy of 0.87. On the validation dataset, performance declined to a sensitivity of 0.58, a specificity of 0.95, an F1 score of 0.67, and an accuracy of 0.85.

Performance improvement through re-adjudication

Both computational approaches benefited substantially from corrected ground truth labels. On the validation dataset, comparing the results in Supplementary Table 3 with Table 2, the expert-driven workflow maintained its F1 score of 0.81 while achieving improved sensitivity (from 0.73 to 0.82) and accuracy (from 0.89 to 0.90), with a slight decrease in specificity (from 0.96 to 0.93). The autonomous agentic LLM workflow showed even more dramatic improvement, with F1 score increasing from 0.65 to 0.74 and accuracy rising from 0.82 to 0.88 (comparing the results in Supplementary Table 5 with Table 3).

These improvements underscore that autonomous computational reasoning was more clinically sound than initially apparent, having been unfairly penalized by annotation limitations rather than true clinical errors.

Table 4 compares the performance of the agentic workflow and the expert-driven workflow across two datasets, using post-re-adjudication labels as the clinical reference standard (see details in Supplementary Tables 8, 9 and Tables 2, 3).

In the balanced refinement dataset, the AP3 outperformed the XP3 across all metrics. It achieved a sensitivity of 0.91 and specificity of 0.95, resulting in a high F1 score (0.93) and overall accuracy (0.93). These results demonstrate the agentic system’s capacity to optimize for both true positive and true negative detection when class prevalence is equal. In the validation dataset, which reflects real-world conditions, performance patterns shifted notably. The agentic workflow’s sensitivity declined substantially to 0.62, while its specificity increased to 0.98. Despite this drop in sensitivity, the agentic workflow maintained a strong F1 score (0.74) and high accuracy (0.88), though the latter is inflated by the correct classification of the majority class. By contrast, the expert-guided prompt optimization (XP3) maintained more balanced performance in the validation set, with slightly lower sensitivity (0.82) and slightly higher specificity (0.93). Its F1 score (0.81) and accuracy (0.90) suggest it is better generalized to the imbalanced dataset, capturing a higher proportion of true positive cases.

To account for the label imbalance observed in the validation dataset, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using balanced bootstrap samples (50% positive and 50% negative cases; n = 20, repeated 15 times) to evaluate the robustness of model performance under equal class prevalence (Table 5).

When prevalence was balanced, the agentic workflow (AP3) showed modest improvement in sensitivity relative to its performance on the unbalanced validation set (0.64 vs. 0.62) while maintaining near-perfect specificity (0.98 [95% CI: 0.96–1.00]). The resulting F1 score (0.76 [95% CI: 0.69–0.83]) and accuracy (0.81 [95% CI: 0.77–0.86]) indicate that the agentic system continued to prioritize precision and conservative classification, even when prevalence was artificially equalized.

The expert-driven workflow (XP3) demonstrated higher sensitivity (0.78 [95% CI: 0.72–0.85]) and slightly lower specificity (0.95 [95% CI:0.92–0.99]) compared with AP3, leading to a higher overall F1 score (0.85 [95% CI: 0.81–0.98]) and accuracy (0.87 [95% CI: 0.83–0.91]).

McNemar’s test on post-adjudication labels revealed no statistically significant differences in classification patterns between workflows on either the refinement dataset (χ² = 1.23, p = 0.267) or validation dataset (χ² = 0.00, p = 1.000), indicating that annotation quality explained initial divergences. Nonetheless, the workflows exhibited notably different sensitivity-specificity trade-offs, the agentic system prioritized specificity (0.98), while the expert-guided workflow maintained higher sensitivity (0.82) in the validation dataset.

Discussion

We developed and evaluated an autonomous agentic LLM workflow for detecting cognitive concerns through computational collaboration, without human intervention. This methodological advance supports scalable, interpretable clinical AI systems that maintain accountability while operating autonomously. Built on the efficient Llama3.1 architecture, the workflow orchestrates five specialized agents, each representing a clinical reasoning domain. This modular setup extends prompt engineering into a collaborative, transparent decision system that complements human thought at machine scale.

The system performed well on a balanced training dataset but showed reduced sensitivity in a more realistic, imbalanced validation set. This illustrates a key challenge: models trained in ideal conditions may falter under real-world class distributions. High specificity was preserved, but the sensitivity drop emphasizes the need for prevalence-aware calibration and stress-testing before deployment.

Our study reveals a fundamental challenge in medical AI: the impact of prevalence shifts between development and deployment on generalizability. The balanced 50% prevalence in our refinement dataset facilitated optimization but resulted in sensitivity dropping from 0.91 to 0.62 at a clinically realistic 33% prevalence. This reflects how systems implicitly optimize decision boundaries for development prevalence. When deployed with different prevalence, these boundaries may not maintain an optimal sensitivity–specificity balance.

To assess whether the observed decline in sensitivity was primarily due to class imbalance, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using balanced bootstrap samples (50% positive, 50% negative). Under these conditions, both workflows maintained a consistent ranking of performance, with XP3 preserving a higher sensitivity and F1 score while AP3 maintained superior specificity. This indicates that the observed trade-offs stem from intrinsic optimization strategies rather than sampling bias.

The maintained high specificity (0.98) and expert re-adjudication findings (44% of apparent false negatives showed sound clinical reasoning) suggest the system learned meaningful patterns. The sensitivity reduction reflects decision threshold optimization under balanced training rather than failure to learn generalizable features. This underscores that apparent performance drops may stem from calibration challenges, not overfitting. By transparently reporting across prevalence scenarios, including balanced resampling, our study contributes a realistic understanding of autonomous AI behavior under clinical deployment.

Notably, prevalence challenges manifested differently across approaches. Compared to expert-guided optimization, which preserved sensitivity, the agentic system favored specificity and stability. Even under balanced resampling, XP3 maintained a higher recall–precision balance, whereas AP3 consistently minimized false positives—confirming that these behavioral differences were intrinsic rather than distribution-driven. Despite missing subtle positives, it achieved over 90% of an expert-level F1 score without human tuning, a crucial step for low-resource deployment.

The workflow used only clinical notes, while human reviewers accessed complete electronic health records. Yet, in 44% of false negatives and 58% of disagreement cases on re-adjudication, the agentic system demonstrated sound reasoning. This highlights the value of structured computational analysis in extracting reliable insights from unstructured data and the need to reevaluate the reliability of human-annotated ground truths.

Our evaluation of three model variants (Llama3.2, Llama3.1, and Med42) showed that moderate-scale general-purpose models outperformed both ultra-light and domain-specific alternatives. Despite Med42’s medical fine-tuning, its performance declined under autonomous iteration. The Llama3.1 model ultimately struck a practical balance between sophistication and deployability. Its efficiency allows local deployment, reducing dependence on cloud infrastructure and enhancing privacy, key features for scalable adoption in settings with limited technical resources.

Comparison with a lexicon NLP baseline underscores the advantage of iterative, reasoning-driven optimization. While the baseline achieved a reasonable balance on the refinement dataset, its performance dropped sharply on the validation set. Both the agentic and expert-driven workflows outperformed this static approach, with the agentic workflow favoring conservative, high-specificity decisions and the expert-driven workflow achieving a more balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. These results suggest that lexicon-based methods can serve as useful benchmarks, but adaptive refinement strategies are better suited to capturing the clinical nuances required for robust, generalizable performance.

Our study has several important limitations. The sample was predominantly White and non-Hispanic, which limited its generalizability across diverse groups with differing linguistic or cultural backgrounds. External and multi-institutional validation will be essential to confirm the robustness and transferability of the model across different care settings and geographic regions. Future work will therefore prioritize the acquisition and integration of larger, more diverse datasets that encompass a broader range of racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds. These efforts are crucial to ensure the model’s fairness, generalizability, and reliability across varied patient populations and presentations of cognitive concerns.

The prevalence mismatch between refinement (50%) and validation (33%) datasets is a significant limitation. While balanced refinement facilitated optimization, this resulted in suboptimal sensitivity at realistic prevalence. The sensitivity drop from 0.91 to 0.62 indicates that decision boundaries optimized for a balanced distribution did not automatically generalize without recalibration of the threshold. Clinical deployment would require prevalence-aware recalibration, including threshold optimization on target samples, retraining on prevalence-matched data, cost-sensitive learning, or dynamic calibration. Without these steps, sensitivity may not meet clinical requirements for screening applications. Expert re-adjudication provides important context: the system demonstrated sound reasoning in 44% of apparent false negatives, suggesting some sensitivity degradation reflects conservative but defensible judgment. Nevertheless, the performance gap underscores that balanced optimization does not automatically produce systems calibrated for real-world prevalence.

To further strengthen the rigor and reproducibility of the re-adjudication process, future work should incorporate multiple independent expert reviewers and quantitative inter-rater agreement analyses. Future work should prioritize the development of datasets that match deployment prevalence, or prevalence-aware training techniques such as cost-sensitive learning or multi-prevalence ensembles. Validation should systematically evaluate performance across prevalence ranges to characterize generalizability transparently.

The system’s reliance on clinical notes likely contributed to moderate sensitivity, given the underreporting of early symptoms and the absence of caregiver observations in routine documentation. While note-based screening shows promise, future iterations should incorporate diagnostic codes, medications, and imaging to improve performance. Such multi-modal data integration will also help overcome limitations arising from the underreporting of early symptoms in routine clinical documentation.

External validation could not be performed because replication would require datasets with equivalent chart-reviewed reference standards and identical variable definitions, which are not currently available across institutions. Future work should adapt this workflow to comparable datasets or support the curation of new, multi-institutional chart-reviewed resources to enable systematic external validation.

Advances in model architecture and training strategies, including lightweight fine-tuning approaches such as low-rank adaptation and parameter-efficient fine-tuning, as well as retrieval-augmented generation and end-to-end fine-tuned models, may further improve sensitivity without proportional increases in computational cost. Such innovations could enable more effective and efficient autonomous systems that remain practical for real-world clinical deployment.

In conclusion, we present an autonomous agentic LLM workflow that performs clinically meaningful screening for cognitive concerns using only unstructured clinical notes. By orchestrating five modular agents through self-directed optimization, the system achieves interpretability and autonomy, two long-sought goals in clinical AI. Through comparative evaluation and expert re-adjudication, we show that autonomous systems, even under constrained information and moderate model size, can approximate expert performance and occasionally identify overlooked clinical signals. More importantly, we highlight a critical transition in medical AI evaluation: from optimizing under balanced, idealized conditions to validating under real-world prevalence. The observed sensitivity drop is not merely a limitation but a pedagogical finding that quantifies the calibration challenge all medical AI systems face. Prevalence-aware calibration—through threshold optimization, cost-sensitive learning, or dynamic recalibration—will be essential to bridge the gap between algorithmic optimization and clinical deployment. Elegant systems are not those that only compute but those that reveal structure, including their own limitations. Medicine needs systems that can be both understood and calibrated for safe deployment. Agentic workflows, built for clarity and transparent evaluation of generalizability, move us closer to these ideals.

Methods

Clinical setting and data sources

The use of patient data in this study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board (protocol 2020P001063). We extracted clinical notes from Mass General Brigham’s Research Patient Data Registry, spanning January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2018. Notes included history and physical exams, clinic visits, discharge summaries, and progress notes. Full-text notes were preserved without segmentation to retain contextual richness. Data analysis occurred between February 1, 2024, and June 13, 2025.

Dataset Curation

The cohort comprised 3338 notes from 200 patients, cognitive concern status was derived from a prior validated chart review study,25 in which expert clinicians achieved substantial inter-rater agreement (κ ≥ 0.80) through systematic review using standardized diagnostic criteria. This binary classification served as the study’s reference standard.

Two datasets were created to support a rigorous two-stage evaluation approach that would both optimize system performance and stress-test clinical generalizability.

Refinement dataset (Dataset 1) was deliberately balanced (50% with cognitive concerns, 50% without) by oversampling positive cases. This design served two methodological purposes: (1) it provided the autonomous agentic system with ample examples of both classes during iterative prompt optimization, preventing class imbalance from confounding the assessment of agent reasoning and prompt refinement strategies; and (2) it allowed for fair exposure to cognitive concern signals during development under idealized conditions, enabling the system to learn discriminative patterns without the statistical bias introduced by severe class imbalance. This approach follows established machine learning practices for development-phase optimization.

Validation dataset (Dataset 2) was constructed via random sampling, which retained the real-world distribution of cognitive concerns. Crucially, this dataset was not seen during model refinement and was used solely to assess how well the strategies learned under balanced conditions would generalize to the challenges of real-world deployment with natural class distribution. This two-stage structure, optimizing in a controlled environment, then testing under realistic conditions, was designed to provide a transparent assessment of both achievable performance and generalizability limitations.

We applied no class weighting, threshold adjustment, or score calibration to the validation data. The explicit goal was to observe the performance characteristics, including any sensitivity degradation, that emerge when a system optimized under balanced conditions encounters natural clinical prevalence. This design choice prioritizes transparent evaluation of generalizability challenges over presenting artificially optimized validation performance.

Baseline characteristics were compared between datasets using independent samples t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Lexicon-based natural language processing system

To establish a baseline for comparison and support the development of LLM-based approaches, we implemented a lexicon-based NLP (Lexicon NLP) system for automated detection of cognitive concerns from clinical notes. The lexicon comprised seven semantic categories derived from the same validated study used to establish the reference standard:25 (1) cognitive medications, (2) diagnoses, (3) memory issues, (4) cognitive assessments, (5) mental status changes, (6) antipsychotic medications, and (7) behavioral symptoms.

Lexicon terms were identified using case-insensitive pattern matching. Negated mentions (e.g., “no memory loss”) and family history contexts were excluded. For patients with multiple notes, mention counts were aggregated using the maximum value across all notes. This Lexicon NLP approach served as a rule-based baseline system against which the performance of LLM-based workflows could be evaluated.

Study design

Figure 1 outlines the experimental design, comparing two workflows: an expert-driven workflow and an agentic LLM workflow. Both began with an identical baseline prompt (P0): “Is this note indicative of any cognitive concern, yes or no?”

The study cohort is split into a prompt refinement and a validation dataset (for evaluating generalizability). The process begins with prompt 0 (P0: Is this note indicative of any cognitive concern, yes or no? \n {note}). AI-generated labels are evaluated against chart-reviewed labels (i.e., ground truth). An expert-driven approach is developed as a benchmark and tested on three different LLMs to find the best-performing LLM that is used for the agentic workflow. The agentic workflow suggests new prompts by evaluating cases of misclassification and summarizing suggestions from specialist agents. P0 initial prompt, XP1, XP2 expert prompt 1, expert prompt 2, AP1, AP2 agent prompt 1, agent prompt 2.

To reflect clinical logic, we classified patients as positive if any note in their record indicated cognitive concerns. This approach acknowledges that symptoms may appear sporadically across encounters.

The expert-driven workflow combined LLMs with clinical expertise through iterative prompt tuning, which served as a benchmark for LLM selection and performance comparison. In contrast, the agentic workflow self-optimizes via specialized computational agents, operating without human input.

Large language models

We evaluated three LLMs from Meta AI: LLaMA 3.1 8B Instruct26 (Llama 3.1), LLaMA 3.2 3B Instruct27 (Llama 3.2), and Med42 v2 8B28 (Med42).

Llama 3.1 is a moderately sized, instruction-tuned general-purpose model with 8 billion parameters. It supports strong reasoning and multilingual capabilities, and features a large 128,000-token context window. Pre-trained on approximately 15 trillion tokens from publicly available sources, it has a knowledge cutoff of December 2023.

Llama 3.2 is a newer, lightweight alternative with only 3 billion parameters, optimized for computational efficiency and multimodal input handling (including image understanding). It shares the same 128,000-token context window and was trained on 9 trillion tokens, with a knowledge cutoff of December 2023.

Med42 is a domain-specific model fine-tuned on a curated medical dataset of about 1 billion tokens. Based on the LLaMA 3 architecture with 8 billion parameters, it is designed for strong zero-shot performance on open-ended medical questions. It has a smaller context window of around 8000 tokens.

All LLMs’ weights were accessed via the Hugging Face LLMs repository. All experiments were deployed on a NVIDIA A100 GPU with 80GB VRAM. Based on benchmark results from the expert-driven workflow (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3), Llama 3.1 was selected for its superior balance of performance and deployability.

Expert-driven workflow

As shown in Fig. 2, the expert-driven workflow implemented a systematic, iterative prompt refinement protocol parallel in structure to the agentic system. The process began with baseline evaluation, where clinical experts applied the initial zero-shot prompt (P0) to both datasets and assessed performance against reference labels. Next, experts conducted systematic error analysis by reviewing misclassified cases, focusing on both false positives and false negatives, and documenting error patterns such as documentation ambiguity, subtle cognitive indicators, and family concern mentions. Based on these findings, prompts were modified to address observed performance gaps: when sensitivity was low, instructions were expanded to capture subtle indicators like family concerns, word-finding difficulties, and care partner observations; when specificity was low, constraints were added to require stronger evidence and exclude non-cognitive conditions. In cases affecting both sensitivity and specificity, clinical reasoning components were refined to align more closely with diagnostic criteria. Each refined prompt was then evaluated on both datasets under deterministic settings (temperature = 0, max tokens = 256), and performance metrics guided subsequent iterations. This cycle continued until improvements plateaued, resulting in a set of optimized prompts for comparison across three different models.

This figure illustrates the structure and process of the expert-driven workflow used to optimize LLM performance through human-guided prompt refinement, including baseline evaluation, systematic error analysis and application across Llama3.1, Llama3.2, and Med42 to assess performance differences. P0 initial prompt, XPn expert prompt number n, FPs false positive cases, FNs false negative cases.

Autonomous agentic LLM workflow

The autonomous agentic LLM workflow represents the core innovation of this study, a completely self-optimizing system that achieves clinical-grade performance without any human intervention. This computational framework orchestrates five specialized agents, each embodying distinct expertise domains within the cognitive assessment process.

Specialist Agent functions as the primary clinical decision-maker, equivalent to an expert neurologist specializing in cognitive assessment. This agent processes clinical notes and prompts instructions to generate binary classifications (“yes” or “no”) accompanied by detailed clinical reasoning, providing both decision and justification in a format that clinicians can readily interpret and validate.

Specificity improver agent operates as an expert in both clinical knowledge and advanced prompt engineering methodologies. Guided by established standard operating procedures (SOP) from previous clinical studies,25 this agent systematically analyzes false-positive cases to identify patterns of LLM misclassification. This analysis generates targeted prompt modifications designed to enhance diagnostic specificity while preserving clinical sensitivity.

Sensitivity improver agent mirrors the specificity improver’s architecture but focuses exclusively on false-negative cases. This agent identifies subtle clinical evidence that the LLM may have overlooked, generating prompt refinements that enhance the system’s ability to detect cognitive concerns that might otherwise escape computational analysis.

Specificity summarizer agent functions as a synthesis specialist, consolidating improvements suggested by the specificity improver across multiple cases into a single, coherent prompt enhancement. This agent ensures that specificity improvements maintain internal consistency and clinical coherence when integrated into the overall prompt structure.

Sensitivity summarizer agent operates as both synthesis specialist and clinical integration expert. This agent first consolidates findings from the Sensitivity Improver, then integrates these insights with established clinical SOPs to create prompt refinements that enhance sensitivity while maintaining clinical validity and diagnostic accuracy.

All agents operate on the Llama3.1, selected based on superior performance in our expert-driven evaluations. The autonomous agentic LLM workflow employs deterministic parameters (temperature = 0) with differentiated token limits: 256 tokens for the Specialist agent (ensuring focused clinical decisions) and 512 tokens for optimization agents (enabling comprehensive analysis). Agent communication followed a sequential execution pattern implemented through string-based prompt passing. Each agent received its input as a structured text string containing two components: a context payload, which included relevant case examples, prior agent outputs, previous prompts, or additional guidance; and a task specification, providing explicit instructions that defined the agent’s assigned objective.

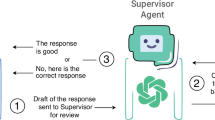

As depicted in Fig. 3, the agentic LLM workflow implements intelligent performance monitoring with automated decision pathways using if-else conditional logic. When sensitivity falls below 0.9, the system automatically engages the Sensitivity Improver and Sensitivity Summarizer agents. When specificity falls below 0.9 (and sensitivity is ≥0.9), the system engages the Specificity Improver and Specificity Summarizer agents. This prioritization ensures that sensitivity is always optimized first when both metrics fall below the 0.9 threshold. Only when sensitivity reaches ≥0.9 does the system shift focus to specificity optimization. This sequential approach eliminates the possibility of conflicting modifications, as only one optimization pathway is active per iteration.

This figure illustrates the structure and process of the autonomous agentic workflow for optimizing LLM performance without human input, using five specialized agents (specialist, sensitivity improver, specificity improver, sensitivity summarizer, specificity summarizer). P0 initial prompt, APn agent prompt number n, FPs false positives, FNs false negatives, SOP standard operating procedure.

Through this iterative process, the autonomous agentic LLM workflow continuously refines its clinical decision-making capabilities without human intervention. The system operates with a maximum of five optimization iterations and concludes when either both sensitivity and specificity achieve ≥0.9 performance, or when sensitivity improvements fall below 0.01, indicating convergence to optimal performance.

Re-adjudication of disagreement cases

Recognizing that ground truth labels in clinical AI often reflect the constraints of original annotation processes rather than absolute clinical accuracy, we implemented a systematic expert review of all disagreement cases between LLM predictions and original annotations. One clinical expert, blinded to both original annotations and AI-generated predictions, manually reviewed these cases to determine whether the clinical notes provided sufficient evidence of cognitive concerns based solely on the documentation available to the AI systems. This expert adjudication served as an independent reference standard to evaluate the clinical appropriateness of LLM predictions and identify potential limitations in the original annotation process.

Statistical analysis

Classification performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1 score, computed against reference (gold standard) labels for both the agentic and expert-driven workflows.

Because temperature was set to 0 during the refinement phase, the LLM outputs were deterministic, producing no stochastic variation across runs. To quantify uncertainty in the refinement set, we generated 15 bootstrap samples of 20 patients selected at random for each workflow and model. For each bootstrap replicate, mean performance metrics were computed, and 95% CIs were derived from the empirical distribution of bootstrap estimates. For the validation set, where temperature was set to 0.1 to introduce minimal stochasticity, 95% CIs were estimated across the five independent iterations.

Comparisons between workflows were performed using McNemar’s test for paired binary outcomes to evaluate differences in classification accuracy between the agentic and expert workflows. McNemar’s test is specifically suited for assessing differences in paired proportions derived from the same subjects, accounting for within-patient dependency and focusing on discordant classifications rather than overall accuracy.29,30 This approach provides a robust, non-parametric test of whether the two workflows differ significantly in their probability of correct classification.

Given the observed label shift between the refinement and validation datasets, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the stability of performance estimates under balanced outcome prevalence. We generated 15 bootstrap samples of 20 patients each from the validation set, constraining each sample to include approximately 50% positive and 50% negative labels. Mean performance metrics and corresponding 95% CIs were then recalculated to assess the robustness of findings to label imbalance.

All analyses were performed in Python (version 3.11) using the statsmodels and scikit-learn packages. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Protected Health Information (PHI) restrictions limit the availability of the clinical data, which were used under IRB approval for the current study only. As a result, this dataset is not publicly available. Qualified researchers affiliated with the Mass General Brigham (MGB) may apply for access to these data through the MGB Institutional Review Board.

Code availability

The code for the autonomous agentic workflow is publicly available at https://github.com/clai-group/Pythia.

References

Liu, A. et al. A survey of text watermarking in the era of large language models. ACM Comput. Surv. https://doi.org/10.1145/3691626 (2024).

Zhao, W. X. et al. A survey of large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.18223 (2023).

Xie, K. et al. Extracting seizure frequency from epilepsy clinic notes: a machine reading approach to natural language processing. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 29, 873–881 (2022).

Xie, K. et al. Long-term epilepsy outcome dynamics revealed by natural language processing of clinic notes. Epilepsia 64, 1900–1909 (2023).

Kim, H.-W., Shin, D.-H., Kim, J., Lee, G.-H. & Cho, J. W. Assessing the performance of ChatGPT’s responses to questions related to epilepsy: a cross-sectional study on natural language processing and medical information retrieval. Seizure 114, 1–8 (2024).

Busch, F. et al. Current applications and challenges in large language models for patient care: a systematic review. Commun. Med. 5, 26 (2025).

Morley, J. E. et al. Brain health: the importance of recognizing cognitive impairment: an IAGG consensus conference. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 731–739 (2015).

Hao, J. et al. Early detection of dementia through retinal imaging and trustworthy AI. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 294 (2024).

Tseng, L.-Y., Huang, S.-T., Peng, L.-N., Chen, L.-K. & Hsiao, F.-Y. Benzodiazepines, z-hypnotics, and risk of dementia: special considerations of half-lives and concomitant use. Neurotherapeutics 17, 156–164 (2020).

Branigan, K. S. & Dotta, B. T. Cognitive decline: current intervention strategies and integrative therapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci. 14, 298 (2024).

Tang-Wai, D. F. et al. CCCDTD5 recommendations on early and timely assessment of neurocognitive disorders using cognitive, behavioral, and functional scales. Alzheimers Dement. 6, e12057 (2020).

Uttner, I., Wittig, S., von Arnim, C. A. F. & Jäger, M. Short and simple is not always better: limitations of cognitive screening tests. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 81, 188–194 (2013).

Hoops, S. et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 73, 1738–1745 (2009).

de Arriba-Pérez, F., García-Méndez, S., Otero-Mosquera, J. & González-Castaño F. J. Explainable cognitive decline detection in free dialogues with a Machine Learning approach based on pre-trained Large Language Models. Applied Intelligence 54, 12613-12628 (2024).

Shinkawa, K. & Yamada, Y. Word repetition in separate conversations for detecting dementia: a preliminary evaluation on data of regular monitoring service. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2017, 206–215 (2018).

Pool, J., Indulska, M. & Sadiq, S. Large language models and generative AI in telehealth: a responsible use lens. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 2125–2136 (2024).

Snoswell, C. L., Snoswell, A. J., Kelly, J. T., Caffery, L. J. & Smith, A. C. Artificial intelligence: augmenting telehealth with large language models. J. Telemed. Telecare 31, 150–154 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Prompt engineering for healthcare: methodologies and applications. Meta-Radiology 100190 (2025).

Christiano, P. et al. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Lester, B., Al-Rfou, R. & Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.08691 (2021).

Shin, T., Razeghi, Y., Logan, R. L., IV, Wallace, E. & Singh, S. AutoPrompt: eliciting knowledge from language models with automatically generated prompts. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.08691 (2020).

Ouyang, L. et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 35, 27730-27744 (2022).

Park, J. S. et al. Generative agents: interactive simulacra of human behavior. In Proceedings of the 36th annual acm symposium on user interface software and technology, pp. 1-22 (2023).

Zhuge, M. et al. Mindstorms in natural language-based societies of mind. Computational Visual Media, 11, 29-81 (2025).

Moura, L. M. V. R. et al. Identifying medicare beneficiaries with dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 2240–2251 (2021).

meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct.

meta-llama/Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct.

m42-health/Llama3-Med42-8B. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/m42-health/Llama3-Med42-8B.

Fagerland, M. W., Lydersen, S. & Laake, P. The McNemar test for binary matched-pairs data: mid-p and asymptotic are better than exact conditional. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 91 (2013).

McNemar, Q. Review of distribution-free statistical tests. Contemp. Psychol. 14, 399–399 (1969).

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: the National Institute on Aging (RF1AG074372, R01AG074372, R01AG082693), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI165535).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.E., L.M.V.R.M., and J.T. conceived, designed, and planned this study. H.E. and L.M.V.R.M. collected and acquired the data. J.T. and C.C. developed the workflow. H.E., L.M.V.R.M., and J.T. analyzed the data. H.E., L.M.V.R.M., J.T., P.F., C.C., N.R., R.R., and L.W. interpreted the data. H.E., L.M.V.R.M., J.T., P.F., C.C., and L.W. drafted the paper. All authors critically reviewed the paper. H.E., L.M.V.R.M., J.T., P.F., C.C., and L.W. revised the final paper. H.E., L.M.V.R.M., and J.T. had access to all the data in the study. All authors approved the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, J., Fard, P., Cagan, C. et al. An autonomous agentic workflow for clinical detection of cognitive concerns using large language models. npj Digit. Med. 9, 51 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02324-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02324-4