Abstract

Urban vegetation, the core component of green infrastructure and critical for sustainable cities, is profoundly affected by the process of urbanization. Urbanization not only leads to substantial vegetation loss (direct impact) but also fosters urban vegetation growth (indirect impact). However, the extent to which these direct and indirect impacts affect vegetation dynamics across cities worldwide and how urban greening will change in the future remain unclear. Using satellite-based greenness and impervious surface datasets, we show that positive indirect impacts mitigated 56.85% of the negative direct impacts across 4,718 cities worldwide from 2000 to 2019. Notably, the offsetting coefficient is much greater in Global North cities (79.13%) than in Global South cities (38.01%) partly due to their socioeconomic differences. This disparity in urban greening dynamics will continue in the future. Approximately 60% of Global North cities and 30% of Global South cities will become greener by 2040. Our results reveal the divergent trade-offs between vegetation loss and enhanced vegetation growth in cities of different socioeconomic levels and stages of urbanization. Such insights are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of urban greening dynamics and for devising strategies to attain sustainable development goals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets in this study are publicly available as follows or can be obtained from Google Earth Engine. MODIS vegetation greenness data (MOD13A1) and landcover data (MCD13Q1) are available at https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov. GTOPO30 digital elevation model data are available at https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov. The GUB dataset is available at https://data-starcloud.pcl.ac.cn/resource/14. The GISA v.2.0 dataset can be obtained from http://irsip.whu.edu.cn/resources/resources_en_v2.php. The dataset of global future urban expansion can be obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://doi.org/10.11888/HumanNat.tpdc.272853). The TerraClimate dataset is available from https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html. The GDP and HDI data were obtained from https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.dk1j0. The WorldPop gridded population density dataset is available at https://hub.worldpop.org/project/categories?id=18. The gridded datasets for population and economy under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways are available from the Science Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.01683). The nine CMIP6 model outputs can be obtained from the Institute Pierre-Simon Laplace server (https://esgf-node.ipsl.upmc.fr/search/cmip6-ipsl/). The administration area data used for mapping were obtained from https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/50m-cultural-vectors/.

Code availability

The scripts for performing the analysis in Google Earth Engine (https://earthengine.google.com/), drafting the figures in MATLAB R2021b and estimating the projected urban vegetation changes in R v.4.2.2 are available from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14630847 (ref. 61). The scripts for performing the main analysis in Google Earth Engine can also be obtained from https://code.earthengine.google.com/?accept_repo=users/171830520nju/Urbanization_global.

References

World City Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities (UN-Habitat, 2022).

2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018).

Sun, L., Chen, J., Li, Q. & Huang, D. Dramatic uneven urbanization of large cities throughout the world in recent decades. Nat. Commun. 11, 5366 (2020).

Jedwab, R. & Vollrath, D. Urbanization without growth in historical perspective. Explor. Econ. Hist. 58, 1–21 (2015).

Grimm, N. B. et al. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 319, 756–760 (2008).

Aronson, M. F. J. et al. A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20133330 (2014).

Hao, L. et al. Urbanization alters atmospheric dryness through land evapotranspiration. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 149 (2023).

Qian, Y. et al. Urbanization impact on regional climate and extreme weather: current understanding, uncertainties, and future research directions. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 819–860 (2022).

Gregg, J. W., Jones, C. G. & Dawson, T. E. Urbanization effects on tree growth in the vicinity of New York City. Nature 424, 183–187 (2003).

Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J. & Melillo, J. M. Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499 (1997).

Zhang, Z., Zhao, W., Liu, Y. & Pereira, P. Impacts of urbanisation on vegetation dynamics in Chinese cities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 103, 107227 (2023).

Paschalis, A., Chakraborty, T., Fatichi, S., Meili, N. & Manoli, G. Urban forests as main regulator of the evaporative cooling effect in cities. AGU Adv. 2, e2020AV000303 (2021).

Ziter, C. D., Pedersen, E. J., Kucharik, C. J. & Turner, M. G. Scale-dependent interactions between tree canopy cover and impervious surfaces reduce daytime urban heat during summer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7575–7580 (2019).

Du, H. et al. Exacerbated heat stress induced by urban browning in the Global South. Nat. Cities https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00184-9 (2025).

Venter, Z. S., Hassani, A., Stange, E., Schneider, P. & Castell, N. Reassessing the role of urban green space in air pollution control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2306200121 (2024).

Veerkamp, C. J. et al. A review of studies assessing ecosystem services provided by urban green and blue infrastructure. Ecosyst. Serv. 52, 101367 (2021).

McDonald, R. I. et al. Current inequality and future potential of US urban tree cover for reducing heat-related health impacts. npj Urban Sustain. 4, 18 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Competition between biogeochemical drivers and land-cover changes determines urban greening or browning. Remote Sens. Environ. 287, 113481 (2023).

Zhang, W., Randall, M., Jensen, M. B., Brandt, M. & Wang, Q. Socio-economic and climatic changes lead to contrasting global urban vegetation trends. Glob. Environ. Change 71, 102385 (2021).

Bille, R. A., Jensen, K. E. & Buitenwerf, R. Global patterns in urban green space are strongly linked to human development and population density. Urban For. Urban Green. 86, 127980 (2023).

Czekajlo, A. et al. The urban greenness score: a satellite-based metric for multi-decadal characterization of urban land dynamics. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 93, 102210 (2020).

Zhao, S., Liu, S. & Zhou, D. Prevalent vegetation growth enhancement in urban environment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6313–6318 (2016).

Guan, X., Shen, H., Li, X., Gan, W. & Zhang, L. A long-term and comprehensive assessment of the urbanization-induced impacts on vegetation net primary productivity. Sci. Total Environ. 669, 342–352 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Direct and indirect impacts of urbanizationon vegetation growth across the world’s cities. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo0095 (2022).

Yang, L., Zhao, S. & Liu, S. Urban environments provide new perspectives for forecasting vegetation phenology responses under climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4383–4396 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Urban−rural gradients reveal joint control of elevated CO2 and temperature on extended photosynthetic seasons. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1076–1085 (2019).

Wachsmuth, D. & Angelo, H. Green and gray: new ideologies of nature in urban sustainability policy. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 108, 1038–1056 (2018).

Chang, Y. et al. Effects of climate, socioeconomic development, and greening governance on enhanced greenness under urban densification. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 206, 107624 (2024).

Winbourne, J. B. et al. Tree transpiration and urban temperatures: current understanding, implications, and future research directions. Bioscience 70, 576–588 (2020).

Justice, C. O. et al. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS): land remote sensing for global change research. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 36, 1228–1249 (1998).

Huang, X. et al. Toward accurate mapping of 30-m time-series global impervious surface area (GISA). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 109, 102787 (2022).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 802–813 (2008).

He, W. et al. Global urban fractional changes at a 1 km resolution throughout 2100 under eight scenarios of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) and Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 3623–3639 (2023).

Jiang, T. et al. National and provincial population and economy projection databases under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways(SSP1-5)_v2[DS/OL]. V4. Science Data Bank https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.01683 (2022).

Chakraborty, T. et al. Large disagreements in estimates of urban land across scales and their implications. Nat. Commun. 15, 9165 (2024).

Smith, D. A. Overurbanization reconceptualized: a political economy of the world-system approach. Urban Aff. Q. 23, 270–294 (1987).

Wolch, J. R., Byrne, J. & Newell, J. P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 125, 234–244 (2014).

Pandey, B., Brelsford, C. & Seto, K. C. Infrastructure inequality is a characteristic of urbanization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, 4–11 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Satellite mapping of urban built-up heights reveals extreme infrastructure gaps and inequalities in the Global South. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2214813119 (2022).

Chen, B. et al. Contrasting inequality in human exposure to greenspace between cities of Global North and Global South. Nat. Commun. 13, 4636 (2022).

Johnston, R. B. Arsenic and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. In Proc. 6th International Congress on Arsenic in the Environment, AS 2016 (eds Bhattacharya, P. et al.) http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3923923 (CRC Press, 2016).

Shi, Q., Liu, M., Marinoni, A. & Liu, X. UGS-1m: fine-grained urban green space mapping of 31 major cities in China based on the deep learning framework. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 555–577 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Urban core greening balances browning in urban expansion areas in China during recent decades. J. Remote Sens. 4, 0112 (2024).

Chen, Y., Yue, W. & La Rosa, D. Which communities have better accessibility to green space? An investigation into environmental inequality using big data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 204, 103919 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Mapping global urban boundaries from the global artificial impervious area (GAIA) data. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094044 (2020).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MOD15A2H - MODIS/Terra Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061 (NASA LP DAAC, 2021).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

Kummu, M., Taka, M. & Guillaume, J. H. A. Gridded global datasets for Gross Domestic Product and Human Development Index over 1990–2015. Sci. Data 5, 180004 (2018).

Sorichetta, A. et al. High-resolution gridded population datasets for Latin America and the Caribbean in 2010, 2015, and 2020. Sci. Data 2, 150045 (2015).

Jing, C. et al. Population, urbanization and economic scenarios over the Belt and Road region under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. J. Geogr. Sci. 30, 68–84 (2020).

Copernicus DEM - Global and European Digital Elevation Model (COP-DEM) (Copernicus DSE, 2020); https://doi.org/10.5270/ESA-c5d3d65

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. MCD12Q1 MODIS/Terra Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid V006 (NASA LP DAAC, 2019).

Wu, T. et al. The Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model (BCC-CSM): the main progress from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1573–1600 (2019).

Swart, N. C. et al. The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4823–4873 (2019).

Wyser, K. et al. On the increased climate sensitivity in the EC-Earth model from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3465–3474 (2020).

Dunne, J. P. et al. The GFDL Earth System Model Version 4.1 (GFDL-ESM 4.1): overall coupled model description and simulation characteristics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002015 (2020).

Lurton, T. et al. Implementation of the CMIP6 forcing data in the IPSL-CM6A-LR model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001940 (2020).

Volodin, E. M. et al. Simulation of the modern climate using the INM-CM48 climate model. Russ. J. Numer. Anal. Math. Model. 33, 367–374 (2018).

Mauritsen, T. et al. Developments in the MPI-M Earth System Model version 1.2 (MPI-ESM1.2) and its response to increasing CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 998–1038 (2019).

Zhao, J., Zhao, X., Wu, D., Meili, N. & Fatichi, S. Satellite-based evidence highlights a considerable increase of urban tree cooling benefits from 2000 to 2015. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3085–3097 (2023).

Chen, J. Contrasting effects of urbanization on vegetation between Global South and Global North. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14630847 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42175136, 42130602), and the Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Climate Change. T.C.’s contribution was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research programme through an Early Career award. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. We also thank the dataset providers for sharing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. developed the conceptual framework of this research, performed the analysis and drafted the figures. J.C. and B.Q. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. B.Q. and W.G. provided conceptualization and supervision, and carried out funding acquisition. T.C., Y.Q., X.M., Y.C., L.L., S.Z., Y.N., X.T. and W.G. contributed to writing the final paper and the interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Amanda Cooper and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

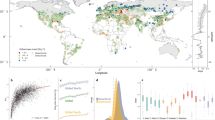

Extended Data Fig. 1 Changes in the fractions of impervious surfaces area (Δβ) and EVI in urban areas during 2000–2019 for global cities.

a, c, The spatial pattern of Δβ (a) and ΔEVI (c) for global 4718 cities. b, d, Histogram of the probability density of cities with different Δβ (b) and ΔEVI (d). The red line represents the medium Δβ and ΔEVI of the cities.

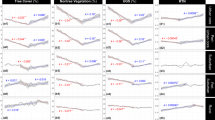

Extended Data Fig. 2 Temporal trends of the fraction of impervious surfaces (β) and EVI in urban areas for global cities.

a,b, The average fraction of impervious surfaces (β) for (a) all 4718 cities and (b) seven parts of the world during 2000–2020. c, d, Same as a,b but for EVI. EAS: East Asia and the Pacific, 963 cities; ECS, Europe and Central Asia, 1512 cities; LCN: Latin America and Caribbean, 553 cities; MEA: Middle East and North Africa, 142 cities; NAC: North America, 1202 cities; SAS: South Asia, 80 cities; SSF: Sub-Saharan Africa, 266 cities. The shaded ranges in a and c denote the range of 5–95% β or EVI for global 4718 cities.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Effects of macroclimate changes on vegetation growth across cities worldwide.

a, EVI in 2000 for cities worldwide. b, Probability density of cities with different EVIs in 2000. c, The extent of vegetation growth enhancement driven by macroclimate change (γ) for global cities during 2000–2019. d, Probability density of cities with different γ. e, Hypothetical EVI changes (VI') only driven by macroclimate changes (without considering the increased urbanization) for global cities during 2000–2019. f, Probability density of cities with different VI'. The red lines are the average values of each variable of the cities weighted by the urban area.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Direct and indirect impacts of urbanization on vegetation greenness from 2000 to 2019.

a, Changes of average EVI in urban areas (ΔEVI) from 2000 to 2019 for global cities. b, Probability density of cities with different ΔEVIs. c,e, Same as a but for the EVI changes induced by the (c) direct and (e) indirect impacts of urbanization. d, f, Same as b but for the direct impact (d) and indirect (f) impacts on the EVI from 2000 to 2019. The red lines are the average values of EVI and the direct and indirect impacts of cities weighted by urban areas.

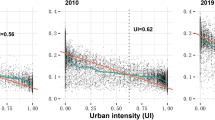

Extended Data Fig. 5 The effect of socioeconomic development levels on the direct and indirect impacts of urbanization on vegetation greenness.

a, The relationship between the rate of urban expansion (Δβ) and Human Development Index (HDI). The solid lines indicate significant trends, and the shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. The small dots denote global 4718 cities and the big dots denote the average Δβ for cities in each 0.025 HDI bin. Significance was determined by two-side Student’s t-test (P = 3.1 × 10−223, n = 4718). b, Same as a but for the direct effects on vegetation (ωd) (P = 1.4 × 10−225, n = 4718). c, Same as a but for the indirect effects (ωi) (P = 6.9 × 10−14, n = 4718).

Extended Data Fig. 6 The projected direct, indirect and climatic impacts on vegetation greenness for global cities under the SSP1-RCP2.6 scenario from 2020 to 2040.

a, Estimated impacts of macroclimate changes on the EVI by 2040 across global cities under SSP1-RCP2.6 scenario. b, Climatic impact on the EVI for cities in different regions across the world. EAS: East Asia and the Pacific, 963 cities; ECS, Europe and Central Asia, 1512 cities; LCN: Latin America and Caribbean, 553 cities; MEA: Middle East and North Africa, 142 cities; NAC: North America, 1202 cities; SAS: South Asia, 80 cities; SSF: Sub-Saharan Africa, 266 cities. The white dots represent the average climatic impact on the EVI weighted by urban areas for each region. The shaded boxes and vertical lines represent the ranges of 25–75% and 10–90%, respectively. c, The probability distributions of climatic impacts for the cities in the Global North and Global South. The dotted lines are the average climatic impacts weighted by urban areas for GN cities and GS cities. The numbers are the proportions of cities with positive or negative climatic impacts. d–f, Same as a–c but for projected direct impacts of urbanization. g–i, Same as a–c but for projected indirect impacts of urbanization.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The projected direct, indirect and climatic impacts on vegetation greenness for global cities under the SSP2-RCP4.5 scenario from 2020 to 2040.

a, Estimated impacts of macroclimate changes on the EVI by 2040 across global cities under SSP2-RCP4.5 scenario. b, Climatic impact on the EVI for cities in different regions across the world. EAS: East Asia and the Pacific, 963 cities; ECS, Europe and Central Asia, 1512 cities; LCN: Latin America and Caribbean, 553 cities; MEA: Middle East and North Africa, 142 cities; NAC: North America, 1202 cities; SAS: South Asia, 80 cities; SSF: Sub-Saharan Africa, 266 cities. The white dots represent the average climatic impact on the EVI weighted by urban areas for each region. The shaded boxes and vertical lines represent the ranges of 25–75% and 10–90%, respectively. c, The probability distributions of climatic impacts for the cities in the Global North and Global South. The dotted lines are the average climatic impacts weighted by urban areas for GN cities and GS cities. The numbers are the proportions of cities with positive or negative climatic impacts. d–f, Same as a–c but for projected direct impacts of urbanization. g–i, Same as a–c but for projected indirect impacts of urbanization.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The projected direct, indirect and climatic impacts on vegetation greenness for global cities under the SSP5-RCP8.5 scenario from 2020 to 2040.

a, Estimated impacts of macroclimate changes on the EVI by 2040 across global cities under SSP5-RCP8.5 scenario. b, Climatic impact on the EVI for cities in different regions across the world. EAS: East Asia and the Pacific, 963 cities; ECS, Europe and Central Asia, 1512 cities; LCN: Latin America and Caribbean, 553 cities; MEA: Middle East and North Africa, 142 cities; NAC: North America, 1202 cities; SAS: South Asia, 80 cities; SSF: Sub-Saharan Africa, 266 cities. The white dots represent the average climatic impact on the EVI weighted by urban areas for each region. The shaded boxes and vertical lines represent the ranges of 25–75% and 10–90%, respectively. c, The probability distributions of climatic impacts for the cities in the Global North and Global South. The dotted lines are the average climatic impacts weighted by urban areas for GN cities and GS cities. The numbers are the proportions of cities with positive or negative climatic impacts. d–f, Same as a–c but for projected direct impacts of urbanization. g–i, Same as a–c but for projected indirect impacts of urbanization.

Extended Data Fig. 9 The projected offsetting coefficients (η) of indirect impacts to direct impacts for global cities under different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways from 2020 to 2040.

a, Estimated η across global cities under SSP1-RCP2.6 scenario. b, The η for cities in different regions across the world. EAS: East Asia and the Pacific, 963 cities; ECS, Europe and Central Asia, 1512 cities; LCN: Latin America and Caribbean, 553 cities; MEA: Middle East and North Africa, 142 cities; NAC: North America, 1202 cities; SAS: South Asia, 80 cities; SSF: Sub-Saharan Africa, 266 cities. The white dots represent the average climatic impact on the EVI weighted by urban areas for each region. The shaded boxes and vertical lines represent the ranges of 25–75% and 10–90%, respectively. c, The probability distribution of η for cities in Global North and Global South. The dotted lines are the average η weighted by urban areas for the GN cities and GS cities. d–f, Same as a–c but for η under the SSP2-RCP4.5 scenario. g–i, Same as a–c but for η under the SSP5-RCP8.5 scenario.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Differences in climatic and socioeconomic characteristic between Global North cities and Global South cities.

The distributions of (a) mean annual temperature, (b) mean annual precipitation, (c) GDP per capita, (d) compound annual growth rate of GDP per capita, (e) population density, and (f) compound annual growth rate of population density the cities in the GS (n = 2888) and GN (n = 1830). The black lines represent the average value of each variable for the GS cities and GN cities. The shaded boxes and the vertical lines represent the ranges of 25–75% and 5–95%, respectively.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Qiu, B., Chakraborty, T. et al. Contrasting effects of urbanization on vegetation between the Global South and Global North. Nat Sustain 8, 373–384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01520-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01520-0

This article is cited by

-

Is it medicine or poison? Exploring the impact of urban expansion on urban resilience in Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2026)

-

Priorities for peri-urban recreation ecology research, policy, and practice in a transforming world

Landscape Ecology (2025)

-

Urban footprints on flora: assessing plant community dynamics across an urbanization gradient in Ranchi, Eastern India

Urban Ecosystems (2025)