Abstract

Transcranial focused ultrasound has shown promising non-invasive therapeutic effects for drug-resistant epilepsy due to its spatial resolution and depth penetrability. However, current manual strategies, which use fixed neurostimulation protocols, cannot provide precise patient-specific treatment due to the absence of ultrasound wave-insensitive closed-loop neurostimulation devices. Here, we report a shape-morphing cortex-adhesive sensor for closed-loop transcranial ultrasound neurostimulation. The sensor consists of a catechol-conjugated alginate hydrogel adhesive, a stretchable 16-channel electrode array and a viscoplastic self-healing polymeric substrate, and is coupled to a pulse-controlled transcranial focused ultrasound device. It can provide conformal and robust fixation to curvy cortical surfaces, and we show that it is capable of stable neural signal recording in awake seizure rodents during transcranial focused ultrasound neurostimulation. The sensing performance allows real-time detection of preseizure signals with unexpected and irregular high-frequency oscillations, and we demonstrate closed-loop seizure control supervised by intact cortical activity under ultrasound stimulation in awake rodents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

An incomplete understanding of the treatment mechanism of intractable epilepsy has led to the low efficacy of conventional medication. To address this, efforts have been made to develop tissue site-specific neurostimulation tools—including deep brain stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation—for drug-resistant epileptic seizures1,2. However, such methodologies suffer from issues related to instability of invasive electrical stimulation. Transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) has shown effective suppression of drug-resistant seizures due to its inflammation-free and long-term stable stimulation, as well as high spatial resolution3,4,5,6,7. However, the preclinical3,4,5,6 and clinical7 trials reported so far, which have used fixed tFUS protocols, have offered limited progress in determining patient-specific neurostimulation parameters. Furthermore, while previous translational studies demonstrated the suppressive effect of tFUS stimulation with a fixed protocol for seizure in animal models, these were verified in only anaesthetized3,4,5 or awake animals with relatively minor symptoms of epileptic behaviour6, without considering the state of the neural activities. What is required is a closed-loop system capable of the optimal therapeutic setting depending on the severity level of the seizure8,9 identified by accurate neurophysiological feedback on stimulation tools.

In this regard, soft brain devices with conformal osculation10,11, robust fixation and mechanical adaptation at the biotic–abiotic interface are essential for both early detection of high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) (80–500 Hz) generated by epileptogenic tissues12,13 and long-lasting neurophysiological feedback to the closed-loop tFUS neurostimulation system. In particular, micro-electrocorticography (ECoG) devices feature high fidelity and high spatiotemporal resolution in electrical neurosignalling, making them suitable for such purposes due to their high-frequency capacity and large-area coverage. However, typical substrate and/or encapsulation materials—such as thick polyimide (PI) and thermally grown silicon dioxide (SiO2)—possess intrinsically high stiffness and poor shape adaptability14,15,16,17,18,19,20, resulting in nonuniform contact on the convolutional structures of cortical surfaces21. Ultrathin mesh devices with dissolvable substrates can offer brain conformability while improving signal quality22,23, but their sensing position accuracy on microsized target tissue points can be limited due to cerebrospinal fluid and tissue micromotion. Existing interfacing devices with low bonding strength to brain tissue24,25,26,27,28 are also vulnerable to ultrasound waves, since the neuromodulatory sonication that delivers acoustic pressure7,29,30,31,32 generates vibration-related mechanical noise. This creates challenges for neurosignal feedback by brain-integrated electrode devices, and optimal closed-loop tFUS neurostimulation cannot be accomplished due to electrical artefact intervention originating from sonication-induced oscillations33. Soft brain-interfacing materials with robust tissue adhesion and conformability34,35 even on a curved surface are thus required to realize artefact-insensitive neural devices coupled with ultrasound stimulation.

In this Article, we report a shape-morphing cortex-adhesive (SMCA) sensor for closed-loop tFUS neurostimulation (Fig. 1a). The SMCA sensor consists of a catechol-conjugated alginate (Alg–CA) as a viscoelastic hydrogel adhesive (Supplementary Fig. 1a)35,36, a stretchable thin (~3 μm) 16-channel microelectrode array and an isophorone bisurea-functionalized polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS–IU) as a viscoplastic self-healing polymer (SHP) substrate (Supplementary Fig. 1b)37. We show that it is capable of conformal and robust fixation to a rodent brain by active shape-adaptation and tough adhesiveness (inset image in Fig. 1a). The cortex-interfacing steps of the SMCA sensor (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Note 1) are as follows. First, robust tissue adhesion via instantaneous gelation of the Alg–CA hydrogel at the contact, which involves conformal contact by filling of interfacial microvoid areas with the swollen hydrogel, brain-mimetic stiffness matching of the tissue–device interface and formation of covalent or non-covalent chemical bonds (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Supplementary Note 1). Second, shape-morphing progress of the patch and complete adhesive gelation resulting in conformal osculation on the wrinkled cortex, which is the synergistic effect of viscoplastic behaviour of the SHP substrate and viscoelastic property of the swollen Alg–CA hydrogel. Finally, stress-free bio-electronic interfacing involves the efficient dissipation of deformation-induced compressive stress energy on the cortex due to the dynamic stress relaxation of the SHP substrate.

a, A schematic illustration and corresponding image for the SMCA sensor mounted conformally on bilateral cerebral hemisphere tissue of rodents. The inset shows the image illustrating robust brain adhesion of the SMCA sensor device on the rat cortex under shear force tension. b, Schematic illustrations of sequential brain-interfacing steps of the SMCA sensor for explaining the tissue-adhesive shape-morphing mechanism. c, An illustration of the closed-loop neural recording and feedback stimulation system integrated with the SMCA sensor and tFUS transducer. The corresponding image (inset) shows the closed-loop therapeutic system implanted into an awake freely moving rat. d, Schematics and corresponding conceptual plots of neural signals of the ECoG devices (top, the conventional ECoG device without tissue adhesion and conformability; bottom, the SMCA sensor) as a function of time under tFUS stimulation. Certainly, the SMCA sensor shows ultrastable neural recording that is not affected by tFUS stimulation. e, Schematic illustrations of the demonstration of closed-loop tFUS seizure suppression in an awake rodent model. The ultrastable neurophysiology capability of the SMCA sensor realizes the real-time delivery of feedback information to the closed-loop neurostimulation system for optimal therapy. Panels adapted from: a and c, mouse skull and brain, ref. 49, under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0; c, rat, ref. 50, under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0.

A miniaturized tFUS transducer was used for awake rodent models with an intracranial SMCA sensor (Fig. 1c). To implement a portable headstage system for a closed-loop brain interface, the tFUS device was coupled with the adaptor of an implanted SMCA sensor using a three-dimensionally printed holder (inset image in Fig. 1c). With the approach, we demonstrate artefact-free ECoG under tFUS neurostimulation in both anaesthetized animals and awake seizure animals. (Fig. 1d). The stable neurosignalling performance allows our platform to function as a chronic seizure predictor and an automatic trigger for neurostimulation by detecting epileptic HFO with high quality. We also use these functionalities to create a strategy for the closed-loop seizure control based on tFUS and the SMCA-ECoG: tFUS initiation triggered by seizure-preceding HFO detection; continuous neurostimulation with an initial dose within a predetermined time interval; tFUS protocol modification in response to real-time feedback that indicates insufficient suppressive efficacy and tFUS termination under the determination that the seizure has been suppressed (Fig. 1e). We illustrate our approach in awake rodents, highlighting the stable closed-loop feedback performance of the SMCA sensor.

Spontaneous shape-morphing cortex adhesion

To verify brain-interfacing functionalities of the SMCA consisting of viscoelastic Alg–CA hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2) and viscoplastic PDMS–IU SHP (the rationale for material selection is described in Supplementary Note 3), as a soft patch platform resistant to acoustic pressure38, its tissue-adhesion performance and shape-adaptation behaviour were comprehensively investigated by control tests. When compared to the adhesive strength of unmodified Alg coated on the SHP (for example, ~12 kPa) (Fig. 2a, red bars), Alg–CA exhibited strong tissue adhesion against both tensile and shear stresses (for example, 17.4 kPa for tensile test and 23.9 kPa for lap-shear test) (blue bars), originating from the presence of catechol groups39. In particular, the high shear adhesiveness of Alg–CA is essential for achieving no delamination of the implanted device on the cerebral cortex, even under ultrasound-induced mechanical vibration. Additionally, to verify the importance of the viscoplastic SHP with a Young’s modulus of several hundred kPa for stable brain interfacing, the adhesive strength of Alg–CA coated on other stiff or elastic substrate materials, namely, PI or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), was compared (Fig. 2b). As expected, the shear adhesive strength of Alg–CA on siloxane-based stretchable materials (for example, PDMS or SHP) was noticeably stronger than that on a conventional flexible substrate, that is, a stiff PI plate with a GPa-scale mechanical modulus (Fig. 2b). It should be noted that these results were determined under experimental setting where each substrate was fixed on the rigid backing film (for example, polyethylene terephthalate (PET)) to verify the adhesive strength of the tissue-interfacing hydrogel itself coated on the polymeric substrate, which might not reflect mechanically dynamic in vivo environments causing deformation of the whole soft device patches. Thus, we performed an additional adhesion test without the backing film to investigate the effect of substrate materials contributing to tissue-adhesive functionality (Fig. 2c). While applying shear stress on the terminal of the Alg–CA coated on the SHP (for example, SMCA film), the viscoplastic substrate (Supplementary Fig. 4a) was effectively stretched up to 860% of its initial length, verifying the maximized tissue-adhesion performance of the SMCA patch realized by combining high fracture toughness and robust adhesiveness (Fig. 2c, blue and Supplementary Fig. 3, bottom photographs). In contrast, other films, such as Alg on SHP (Fig. 2c, red, and Supplementary Fig. 3, top photographs) or Alg–CA on PDMS (green, and Supplementary Fig. 3, middle photographs), had relatively low toughness values and stretchability (for example, 78% for Alg/SHP and 109% for Alg–CA/PDMS). Furthermore, the SMCA film showed dramatic stress relaxation behaviour as a function of time, indicating its typical viscoplasticity (Fig. 2d, blue, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 and Supplementary Note 4). However, the Alg–CA/PDMS film possessed constant stress after applied strain (green, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 and Supplementary Note 4). In qualitative tests, the excellent stretchability of the SMCA film up to 600% also led to strong adhesion performance onto wet brain tissue (Fig. 2e, bottom photographs), whereas the Alg–CA/PDMS film exhibited mechanical failure (middle photographs) and the Alg/SHP film was easily delaminated from the brain tissue (top photographs). All results for maximized brain-adhesiveness of the SMCA consistently demonstrate the synergistic effect between the viscoplastic substrate with high toughness and dynamic stress dissipation based on reversible hydrogen bonds and the viscoelastic adhesive with strong attachment by tissue-specific chemical bonds.

a, Comparison of the tissue-adhesive strength between Alg and Alg–CA according to stretching direction. Both hydrogel materials were coupled with the SHP substrate. Data points are mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) (n = 3). Unpaired two-tailed t-test: *P = 0.0417 between Alg/SHP and SMCA groups for tensile adhesive strength, ***P = 0.0009 between Alg/SHP and SMCA groups for shear adhesive strength. b, Shear adhesive strength of the tissue-attached Alg–CA-coated bilayers (coated on PI (grey), PDMS (green) and SHP (SMCA) (blue)) with a backing stiff film (PET). Data points are mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3). One-way analysis of variance test: NS, not significant, indicates P = 0.3370 between the Alg–CA/PDMS and SMCA groups, ***P = 0.0002 between the Alg–CA/PI and SMCA groups. c, Shear stress curves of the tissue-attached Alg/SHP (red), Alg–CA/PDMS (green) and SMCA (blue) films without the backing substrate as a function of tensile strain (elongation rate of 100% min−1). Inset illustration depicts a cross-sectional view of a tissue-attached bilayer patch. d, Normalized plot of shear stress of the tissue-attached Alg–CA/PDMS (green) and SMCA (blue) films as a function of time at an elongation strain of 80%. The inset illustration describes the cross-sectional view of a tissue-attached patch while stretched. e, Comparative images regarding tissue-adhesion performances of Alg/SHP (top), Alg–CA/PDMS (middle), SMCA (bottom) films on bovine brain while shear strain was applied. f, Comparative sequential schematics of the FEA model illustrating the time-variant stress distribution of brain-interfaced PDMS (top) and SMCA (bottom) for 1 h. g, Comparative sequential images of Alg–CA/PDMS (top) and SMCA (bottom) mounted on bovine brain tissue with flexuous cortical morphology illustrating the mechanical behaviour of bilayer films over time. The surface temperature of the brain tissue was set at 37 °C. h, Cross-sectional photographs (top) and corresponding confocal fluorescence images (bottom) of Alg–CA/PDMS (left) and SMCA (right) films mounted on the largely winkled surface of bovine cortex. Each image was obtained 1 h after tissue contact.

We also examined stress-free shape-adaptive properties of the SMCA patch (see Supplementary Note 5 for reasoning on the driving source of shape-morphing behaviour of the SMCA). According to finite element analysis (FEA), a SMCA film favourably filled the void space of the curved objects (for example, brain wrinkles) and alleviated deformation-induced stress (Supplementary Figs. 4b and 5), while PDMS failed not only conformal contact to the curvature but also stress relaxation at the interfaced plane (Fig. 2f, details for FEA analysis methodology are described in Supplementary Note 6). Corresponding to the computational models, the spontaneous shape-morphing property of the SMCA film was also observed in ex vivo tests using bovine brain tissue (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Video 1). Although the Alg–CA/PDMS bilayer was not deformed into brain wrinkles (Fig. 2g, top photographs), the SMCA film was autonomously shape-morphed into the concave flexura of the cortex without any externally applied driving force (for example, electromagnetic field, pressure, thermal energy), which led to complete conformation to surface profile (Fig. 2g, bottom photographs) (see Supplementary Note 7 for detailed discussion on the results). The cross-sectional photographical (top) and three-dimensional (3D) confocal microscopic (bottom) images of the fluorescent dye-labelled bilayer patches (green coloured label for Alg–CA, red coloured labels for PDMS and SHP) interfaced with the brain were confirmed (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 7), which verifies osculating capability of the SMCA patch that did not generate a spatial void at the interface (Fig. 2h, right photographs) while there were large air gaps between the cortical surface and the Alg–CA/PDMS bilayer (Fig. 2h, left photographs). The moisture retention of swollen Alg–CA in tissue-attached SMCA patch, stably maintained for 7 days without substantial water loss even in the ex vivo condition, strongly indicates that the SMCA sensor can be chronically integrated with the cortex by the Alg–CA interfacing layer in the in vivo condition of intracranial space filled with cerebrospinal fluid (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results comprehensively demonstrated that our material strategy combining Alg–CA polymer with soft fluidity and instantaneous gelation and PDMS–IU SHP with thermoplastic deformation and effective strain energy dissipation is suitable for biocompatible and brain-osculated interface.

Direct transfer-printing process of SMCA sensor

In addition to the spontaneous shape-morphing performance originating from the thermoplasticity of the viscoplastic SHP, such mechanical functionality can be useful to integrate the SMCA sensor incorporating a new class of printed stretchable electrode devices (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 9, see detailed fabrication process of the ultrathin stretchable multielectrode devices for the SMCA sensor in Methods). The unconventional platform of stretchable electronics is expected to be implemented in a way that ultrathin and wavy structures (~3 μm) are directly transfer printed onto the SHP substrate even without surface stickiness, by embedding the bottom of the device into the shallow surface of the SHP layer and anchoring frame of the device in the gentle pressure-induced shape-deformed substrate whose thermoplastic behaviour is accelerated by higher thermal energy (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6). To fully support our assumption, we prepared the transfer-printing process with different temperatures (25, 40 and 60 °C). As expected, the SEM images illustrating sequentially enhanced shape deformation of thermoplastic SHP by higher temperature evidently verify the reliable direct transfer-printing methodology of ultrathin electrodes realized by anchoring and embedding processes (Fig. 3c), which cannot be achieved in thermoset polymers. Using this method, SHP-printed multielectrode arrays from a wafer-scale manufactured batch (Supplementary Fig. 9) secure high areal uniformity under 0 and 50% strains (Fig. 3d). Our direct transfer-printing process also enables electrical resistance (up to 70% strain in the linear stretching test and 35% strain for 100 cycles in the repetitive stretching test) and electrochemical impedance (up to 50% strain) values of the stretchable electrodes to be highly uniform (Fig. 3e–g). We then completed the SMCA sensor by formation of the Alg–CA film onto the front of electrode array by facile coating and dehydrating of the Alg–CA-dispersed aqueous solution (Supplementary Fig. 10). The hydrogel solution was easily formed into the adhesive dry film by being coated on the front of electrode array as a whole piece without concerns about electrical crosstalk between adjacent channels since the deprotonated polysaccharide hydrogel still possesses high electrical resistance35. Furthermore, the use of the ionically conductive adhesive hydrogel as a bio-interfacing layer resulted in lower magnitude of electrochemical impedance (Supplementary Fig. 11a) by capacitance effect (Supplementary Fig. 11b) indicating that Alg–CA layer itself functions as a low-impedance coating without additional micropatterned or nanostructured films (for example, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS), iridium oxide (IrOx) and titanium nitride (TiN)). In addition to providing interfacial modulus matching (Supplementary Fig. 2) and adhesive functionality (Fig. 2a–c) at the tissue–device contact, therefore, the Alg–CA hydrogel was expected to improve neurosignalling performance of SMCA sensor platform.

a, An exploded illustration of a SMCA sensor consisting of the shape-morphing SHP substrate, printed stretchable electrode array and adhesive Alg–CA hydrogel. b, Concept schematics for the newly proposed transfer-printing process of a stretchable device consisting of PI substrate and/or encapsulation layers and deposited metal nanomembranes using the shape-morphing property of the SHP substrate. c, SEM images of the transfer printed stretchable devices on the shape-morphing SHP substrate without thermal annealing (i) and after thermal annealing at 25 °C (ii), 40 °C (iii) and 60 °C (iv) for 10 min. Each inset shows magnified electrodes of the devices under different thermal annealing conditions. d, A cumulative probability of the electrical resistance of all channels from wafer-scale fabricated four-stretchable electrode arrays (total 72 channels) transfer printed on the shape-morphing SHP substrate. e, Resistance of the stretchable electrode while stretching up to 70% strain. Inset images show a SHP-transferred electrode device patch before and after stretching. f, Normalized electrical resistance during repetitive stretching cycles with 35% strain. The inset graph shows magnified raw plot of resistance in ten stretching cycles. g, Electrochemical impedance while stretching up to 50% strain. h–j, Images showing the ultraconformal, robust brain-adhesive performance of the SMCA sensor device on an ex vivo bovine cortex with a curvilinear surface. h, Formation of an ultraconformal osculation of the SMCA sensor device along a randomly wrinkled surface of the cortex via shape-morphing properties. i, Robust brain integration of the SMCA sensor device withstanding shear force tension. j, Durable brain-adhesive interface after circumfusing a water droplet.

Before the in vivo demonstration using the SMCA sensor, its on-brain adhesion was investigated on the ex vivo bovine cortex (Fig. 3h–j). The SMCA sensor was conformally mounted on the uneven wrinkled cortex surface and spontaneously shape-morphed into the various valleys with different depths (Fig. 3h). It is clearly confirmed that integration of the ultrathin stretchable electrode array with mesh-like serpentine interconnect pattern does not decrease thermoplasticity or stress relaxation property of the SMCA sensor patch compared to bare SHP film, which leads to ultraconformality of the cortex-interfacing device (Supplementary Fig. 12). Such tissue-adhesion performance was stably maintained when shear stress was applied to the SMCA sensor (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Video 2); moreover, the robust adhesion property was proved even in the washdown condition by water (Fig. 3j, Supplementary Fig. 13 for extended sequential images and Supplementary Video 3 showing the full sequence of the adhesion test in the washdown condition). Considering the successful ex vivo demonstration, our SMCA sensor is highly suitable for achieving the ultimate brain–device interface.

tFUS artefact-resistant neural recording

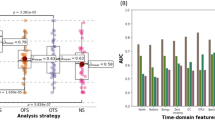

Designed for spontaneous adaptation to the 3D curvilinear geometry and surface morphology of the cortex, the shape-morphing and tissue-adhesive functionalities of the SMCA sensor were expected to contribute to securing clear electrical brain activity during tFUS neurostimulation without sonication-induced artefacts, which would not be achieved in other soft neural device platforms (Fig. 4a). To prove our assumption, we prepared an acute in vivo experimental setting where the neurosignalling stability under tFUS sonication of the SMCA sensor is investigated (details of the experimental setup are described in Supplementary Note 8). We presented the quantitative neurophysiology performance of soft ECoG devices coupled with ultrasound stimulation by signal qualities of baseline activity and tFUS-evoked event-related potentials (ERPs). Each parameter was evaluated by averaging power spectral density (PSD) of their noise sources, which are 60 Hz line noise and the tFUS-defining pulse-repetition frequency (PRF) respectively, extracted from the neural signal for multiple animals (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 14 and Table 1 for detailed information on the acute in vivo experiment). A typical protocol of tFUS with a PRF of 1 kHz and a 50% duty cycle, which has been previously reported for eliciting a neuronal response40, was used due to not only its guaranteed neuroactivative effect but also its identifying frequency distinct from the principal range of brain activity (0.1 to 600 Hz for rat)41, which could easily be considered as tFUS-induced artefact in power spectral analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 15 for detailed information on acute in vivo sonication setup and neurostimulation protocol).

a, Schematic image of the in vivo material performance test. b–e, Top-view images of brain-mounted stretchable electrodes integrated with four different materials, including PDMS (b), SHP (c), Alg (interface)/SHP (substrate) (d) and SMCA (SMCA sensor) (e). f–i, Series of electrocorticogram raw plots from a representative trial of each material platform (upper graphs) and magnified data plots of three consecutive channels, including a channel located on the visual cortex of the left hemisphere (channel 15) directly stimulated by tFUS of each material platform (lower graphs), including PDMS (f), SHP (g), Alg (interface)/SHP (substrate) (h) and SMCA (SMCA sensor) (i). j, Statistical analysis results of average noise and artefact level showing the signal quality of electrical activity from each material platform. The power density of PRF shows the artefact level caused by ultrasound stimulation (n = 60). Box plots indicate median (white line), 25 and 75% quartiles and maximal and minimal values except outliers (whiskers) (NS, not significant, indicates P > 0.05 among the PDMS, SHP and Alg/SHP groups, ***P < 0.001 between the SMCA sensor and other control groups with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. P = 2.5996 × 10 × 10−6 for PDMS(tFUS)-SMCA(tFUS), P = 5.4934 × 10 × 10−5 for SHP(tFUS)-SMCA(tFUS), P = 0.0002 for Alg/SHP(tFUS)-SMCA(tFUS), P = 7.0151 × 10 × 10−12 for PDMS(Baseline-tFUS), P = 7.3078 × 10 × 10−10 for SHP(Baseline-tFUS), P = 2.6968 × 10 × 10−13 for Alg/SHP(Baseline-tFUS) and P = 2.3678 × 10 × 10−9 for SMCA(Baseline-tFUS)). M, motor; S, somatosensory; C, cingulate; R, retrosplenial; P, posterior parietal; V, visual; B, bregma; Ref, reference; Gnd, ground. Panel a, mouse skull and brain, adapted from ref. 49 under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0; rat, adapted from ref. 50 under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0.

Clearly, the ECoG devices using SHP, Alg/SHP and SMCA were conformally adapted to the cortex surface except PDMS, which led us to reason that this conformability originates from the shape-morphing characteristic of the SHP substrate (Fig. 4b–e). Compared to electrode-printed devices supported on the SHP substrate, opaque air gaps were dominantly formed at the interface between the PDMS-based ECoG device and cortex since the supporting patch of the device did not conform to the cortical surface even after the gentle touch resulted from the lack of shape adaptability, which indicates that soft ECoG devices coupled with the conventional elastomeric substrate without its own tissue conformality are incapable of forming uniformly osculant interface even with the small animal’s brain whose cortical structure of sulcus and gyrus is not very flexuous compared to that of non-human primates or human (Fig. 4b). The non-conformal bio-electronic interface caused a degradation in the neural signal, possibly by 60 Hz of line noise (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 16). Moreover, such unstable tissue-interfacing led to a large distortion of the original neural signals under tFUS sonication (a magnified graph below, Fig. 4f). On the other hand, the soft ECoG device platforms using shape-morphing SHP substrate including the SMCA sensors uniformly conformed to the surface morphology of the cortex without any void in a short time (within 1 min) due to the accelerated shape deformation by gentle touch (Fig. 4c–e). The ECoG device printed on the SHP substrate demonstrated better baseline signal quality (Fig. 4c,g and Supplementary Fig. 16). The Alg hydrogel with fluidic material property and modulus-matching capability further reinforced brain conformality (Fig. 4d) and baseline stability (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 16). Despite satisfactory improvement with respect to baseline, the tFUS-induced noise still greatly intervened during neuromodulation period, indicating that tissue conformality alone cannot completely prevent mechanical artefacts (Fig. 4g,h, magnified graphs below). In this regard, we observed that such artefacts were effectively reduced in the SMCA sensor conformally affixed to the cortex (Fig. 4e,i). In addition to stable baseline neural recording due to extremely conformal interfacing with ionically conductive soft hydrogel (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 16), continuous neurophysiology capability of the SMCA sensor under tFUS sonication also realizes monitoring of the intact tFUS-modulated neural response in the manner of specific ERP patterns from channels close to the sonicated visual cortex (Fig. 4i, a magnified graph). Time trace plot of multichannel ECoG streaming further verifies that there was no crosstalk issue between the electrodes both in Alg/SHP devices and SMCA sensors that used a cortex-interfacing hydrogel layer as a whole piece35. To further quantitatively support the unprecedented neurophysiological stability under tFUS neurostimulation of the SMCA sensor, we analysed the PSD of 1 kHz PRF sonication-induced artefacts within in vivo neural signals recorded from the aforementioned four ECoG devices (Fig. 4j). Considering the frequency range of neural oscillation41, if the power of the 1 kHz frequency increased during tFUS stimulation, then it is regarded as a tFUS-induced artefact, not a neural signal. The representative and statistical results regarding the power level trends on each ECoG platform clearly support our assumption (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 17). The control groups without tissue-adhesive functionality were evidently vulnerable to tFUS neurostimulation (Fig. 4f–h and Supplementary Fig. 17a–c). In contrast, our SMCA sensor effectively minimized 1 kHz PRF-related mechanical artefact intervention (Supplementary Fig. 17d), which was not enough to be realized by only conformality without a robust surface fixation property (Supplementary Fig. 17b,c) (a detailed discussion on visualized tFUS-induced artefacts in recorded neural signals appears in Supplementary Note 9). Put together, the results highlight that the coexistence of tough adhesion and shape-morphing properties inherent in the SMCA sensor platform played the most important role in achieving high-fidelity monitoring of cortical activity coupled with ultrasound modulation, thereby increasing the possibility for the realization of closed-loop tFUS neurostimulation (see Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Note 10 for the discussion on the probable operating mechanisms of the soft ECoG device platforms including the SMCA sensor with the correlation between material functionalities and neurosignalling performance).

Seizure-preceding epilepsy control with tFUS

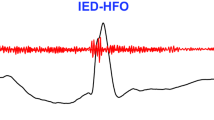

Considering the tFUS artefact-resistant neural signal monitoring performance of the SMCA sensor, our materials synthesis and device fabrication strategies were expected to remain valid for acoustically transparent interfacing to both normal and seizure-induced brain tissues even in long-term intracranial implantation. Notably, the accurate detection of the seizure-preceding HFO as an informative biomarker of the following ictal phase can lead to instantaneous triggering of effective neurostimulation for early-stage suppression of epileptic seizures. In this regard, the HFO recording capability of the SMCA sensor in an awake rat model with a kainic acid-induced seizure was investigated (Fig. 5a–d). Typical HFO signals included in raw cortical activity were confirmed by fast and short burst oscillations in the range of 80 to 500 Hz (Fig. 5a, top and middle) and the corresponding power spectrum (Fig. 5a, bottom), whose signal quality is not degraded for long-term implantation (see Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20 and Supplementary Note 11 for details). Not only capable of of long-term multichannel ECoG recording, the implanted SMCA sensor also verifies its chronic biocompatibility (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 21). Staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein to show its expression in astrocytes, and IBA-1, representative of ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 protein expression in microglia, revealed sustained biosafety of the SMCA sensors both in the short- (4 weeks) and long-term (24 weeks) when compared to the sham group.

a, Raw signal (top), filtered HFO (80–500 Hz bandpass filter, middle) and power spectrogram (bottom) of HFO measured by the SMCA sensor in the kainic acid seizure model. b, Automated tFUS stimulation in the awake kainic acid model triggered by HFO detection. Seizure spike waves (SW) sequentially followed HFO (indicated by #). The time trace was adopted from channel 8 (Ch. 8) in Fig. 4b (indicated by *). c, Sham trial 16-channel raw time traces and spectrogram of the tFUS/ECoG-based automated stimulation system. d, tFUS stimulation trial 16-channel raw time traces and spectrogram, triggered by HFO detection. e,f, Averaged z score topography of epileptic oscillatory power of sham (e) trials and tFUS stimulation (f) trials (eight pairs of Sham-tFUS trials from six animals). g–j, Normalized average PSD of delta (1–4 Hz) (g), theta (4–8 Hz) (h), alpha (8–13 Hz) (i) and beta (13–30 Hz) (j) from Sham and tFUS seizure cases (HFO detection at t = 0). Data points are mean ± s.e.m. All channel averaged, eight pairs of Sham-tFUS trials from six animals are used (Wilcoxon rank sum test, *P < 0.05). Max., maximum.

Next, neural recording performance of the SMCA sensor coupled with customized tFUS stimulation with the therapeutic protocol in awake animals for monitoring and treating epileptic seizures was investigated. To better facilitate portable bidirectional neural interface platform in freely moving animals, a customized headstage system combined with a tFUS transducer and an implanted SMCA sensor was devised (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Note 12). In the system, responsive tFUS stimulation determined by seizure-preceding HFO detection was set to be targeted to the right CA3 of the hippocampal area before ictal onset. With this approach, our customized system precisely predicted the following seizure spike wave and appropriately performed a proactive therapeutic action (Fig. 5b). We adopted a tFUS protocol of 40 Hz PRF as the therapeutic trial42 to be applied to awake seizure animals (see Supplementary Fig. 23 and Supplementary Note 13 for rationale of the tFUS protocol and detailed information of stimuli pulse engineering).

Consequently, neural recording performance of the SMCA sensor in awake seizure rats was stably maintained regardless of the intervention of continuous tFUS neurostimulation (Fig. 5c,d) (see Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25 for detailed information on the system setup and in vivo experimental procedure). In the representative time trace of all channels, raw signals recorded from the same seizure animal, we observed that the amplitude and duration of epileptic spike waves were dramatically diminished by 3 min of stimulation initiating from the moment of seizure-preceding HFO detection with the protocol of 40 Hz PRF and 5% duty cycle during a tFUS-stimulated seizure episode (termed tFUS) (Fig. 5d, upper graph) in comparison with those of ictal waves during the sham seizure episode (termed sham) of the same period of time (recording for 3 min without neurostimulation after the moment of HFO detection) right before the tFUS case (Fig. 5c, upper graph). Corresponding to the electrophysiological activities recorded in the seizure epoch, the normalized power spectrogram of a channel electrode in the SMCA sensor array near the tFUS neurostimulation site (Ch. 9) supported the online seizure-suppressive effect of tFUS neurostimulation (Fig. 5c,d, lower graphs). It should be noted that there was no tFUS artefact interference in any frequency band of the brain activity including the 40 Hz corresponding to the PRF of the seizure-suppressive protocol, which again definitely highlight the ultrasound artefact-resistant neurosignalling performance of our SMCA sensor platform allowing us to evaluate the efficacy of the neurostimulation protocol. On the premise of that, in terms of the power spectrogram free from the artefact, the therapeutic result indicates that the trend of abnormal neural activity was effectively suppressed by a control protocol of tFUS neurostimulation rather than natural sedation over time, as presented in the sham case (Fig. 5c, lower graph) (see Extended Data Fig. 2 for the control study of tFUS-modulated seizure activity from a single channel and the spatiotemporal pattern of neural recordings from the principal seizure phase, details are described in Supplementary Notes 14 and 15).

Furthermore, the seizure control effect of a 40 Hz PRF stimulation on multiple animal subjects was cumulatively investigated to evaluate the average efficacy of the tFUS neurostimulation protocol and identify its prognostic variation for the individual in vivo models. The series of two-dimensional z score topographies classified according to the main frequency band of brain activities averaged from all pairs of the sham and tFUS cases illustrates that oscillatory power and duration from delta (1–4 Hz) to beta (13–30 Hz) oscillations were largely suppressed in both hemispheric areas after applying the tFUS neurostimulation triggered by HFO detection to the right CA3 region (Fig. 5f) in comparison with sham cases (Fig. 5e). Each of the averaged oscillatory power density values also illustrated that oscillation energy ranging from the delta to beta frequency bands was largely suppressed during tFUS stimulation compared to that of the Sham cases in the same time interval (Fig. 5g–j). These results consistently demonstrated that the amplitude of ictal oscillation and duration of seizure-like hyperactivity were reduced by the 40 Hz PRF protocol, successfully verifying its online therapeutic efficacy.

Closed-loop dose-regulating seizure control

Although the optimally selected tFUS protocol may act as a key enabler for effectively suppressing irregular ictal symptoms originating from epileptic seizures, as intractable epilepsy is an unforeseeable disorder that features discrete patterns of ictal oscillations, tFUS neurostimulation with a fixed protocol remains limited to personalized electroceuticals. Considering the critical challenge, the closed-loop function should be integrated into the bidirectional sensing-stimulation system. In this regard, we systemically designed a closed-loop framework capable of adaptive-feedback control of tFUS neurostimulation protocols corresponding to various seizure states in numerous individual cases (Fig. 6a,b) (details for design and operational flow of the closed-loop seizure control system are described in Supplementary Note 16). The unconventionality of the proposed system, equipped with an autonomous dose-regulating function, originates from the use of an intact neural response for therapeutic sonication as a feedback parameter, which is achieved by the artefact-free SMCA sensor.

a, Flow chart of the tFUS–SMCA sensor-coupled closed-loop seizure control system. b, Schematic illustration of the two-type tFUS dose modulation concept, Ispta modulation (‘A’ mode) and Isppa modulation (‘B’ mode). AMP, amplitude; PD, pulse duration. c,d, Representative time trace of all channels (c) and time trace and spectrogram of a single channel (Ch. 9) (d) of the closed-loop seizure control episode with an Ispta dose increase. e,f, Representative time trace of all channels (e) and time trace and spectrogram of a single channel (Ch. 9) (f) of the closed-loop seizure control episode with an Isppa dose increase. Norm., normalized; PD, pulse duration.

In general, based on the precise HFO detection via the SMCA sensor, the evoked seizure oscillation was effectively controlled by tFUS neurostimulation with the default protocol (spatial-peak temporal-average intensity (Ispta) of 0.05 W cm−2 and spatial-peak pulse-average intensity (Isppa) of 1 W cm−2) in our closed-loop system (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 17). For more undesired cases not resolved by the default setting, our two types of closed-loop were also demonstrated. Representative examples of the ‘A’ mode and ‘B’ mode closed-loop illustrated seizure control by Ispta- or Isppa-modulated three-level tFUS protocols (Fig. 6c,e). In the detailed trace of neural activity as a magnified profile documented from a channel located in the posterior parietal cortex, the five different phases of the closed-loop sequence could be indexed at the individual neural waveforms from preseizure (or interictal) (phase I) oscillation, through the seizure epoch, to baseline recovery ranges under three-level closed-loop tFUS neurostimulations (Fig. 6d,f). In both cases, the induced seizure model was an intransigent type that was not alleviated by the initial neurostimulation trial (dose 1) with the default setting (phase II), resulting in a dose increase. Although the following Ispta and Isppa modulations (dose 2) were certainly effectual, the considerable amplitude and duration of ictal waves were still observed (phase III). Another dose increment (dose 3) finally led to full mitigation of residual epileptiform discharge (phase IV) (see Supplementary Notes 18 and 19 for a detailed description of the closed-loop Ispta or Isppa dose-regulating tFUS seizure suppression). The corresponding power spectrogram also supported that the dose-regulating closed-loop system was effective in suppressing different types of randomized seizure. The maximum intensity of tFUS protocol used in the closed-loop system satisfies the recent guidelines of biophysical safety for tFUS stimulation43, inducing tissue temperature rise less than 2 °C, which considered to be safe and unlikely to result in tissue-damaging issues (Supplementary Fig. 27). The most intensive soundwaves we used were also verified to be free from undesired blood-brain barrier (BBB) opening issues (see Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Note 20 for detailed information on the BBB opening verification test). In addition to the single channel-driven neural signal trace, the three kinds of spatiotemporal amplitude topographic map data of neural dynamics in the full sequence of tFUS-regulated seizure suppression were achieved by the SMCA sensor array (Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5, Supplementary Note 21 and Video 6). It should be noted that the seizure spikes recorded by the multielectrode array in the SMCA sensor clearly indicate that there is no electrical interference in the neural signal, supported by temporally delayed ictal peaks from the channel near the signal source (Supplementary Fig. 26). The case study for closed-loop tFUS seizure suppression includes a seizure model with repetitive radial dynamics triggered from a channel located nearly on the posterior parietal cortex that might be considered the seizure source (Ch. 13) and spread throughout the right hemispheric area (Fig. 4, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Video 7). During the three-level closed-loop tFUS epoch, two-dimensional topographies of electrical seizure activity in the colour map also illustrate its most intense level (representative peaks *1 to *3, phase II) almost not affected by the dose 1 protocol, gradual attenuation trend of seizure intensity and oscillation frequency with maintaining its characteristic propagating pattern by the dose 2 protocol, and suppression of residual ictal waves by the dose 3 protocol (a representative peak *8, phase IV) (see Supplementary Video 6 for sequential topographic clips of spatiotemporal electrographic neural dynamics during the closed-loop Ispta-regulating seizure suppression episode). Such informative findings regarding effective suppression of the varied epileptiform discharges and distinct ictal dynamics involved in each seizure case from individual animals were clearly visualized.

Conclusions

We have reported a SMCA sensor for closed-loop tFUS neurostimulation. The SMCA device has a layered structure consisting of ionically conductive and adhesive Alg–CA polymers and viscoplastic SHPs. It exhibits conformal and robust fixation on a curved cortical surface, providing stable ECoG signal monitoring even under tFUS neurostimulation in freely moving awake rodents. In particular, our closed-loop epilepsy therapeutic system effectively suppressed irregular ictal waves through tFUS dose-regulating neurostimulation. Furthermore, the spatiotemporal mappings obtained by the SMCA sensor array illustrate how tFUS neurostimulation positively affects injured tissue sites associated with abnormal neural activities even in the presence of acoustic waves. Our SMCA platform could potentially be used to develop closed-loop tFUS systems that can flexibly determine an optimal manoeuvre in response to the state of the intact brain activity modulated by ultrasound stimulation.

Methods

Materialization of SMCA bilayer films

The SMCA bilayer films were simply fabricated by coupling a SHP as a substrate and an Alg–CA adhesive hydrogel as an adhesive. After O2 plasma treatment of an SHP surface, 150 μl of an aqueous solution of Alg–CA hydrogel (2.5% dissolved in deionized water) was drop-casted and uniformly coated on a 100-μm-thick patch of the SHP substrate within a mould that defined the adhesive area. The hydrogel-coated SHP films were dried over 6 h on a clean bench for solidification of the hydrogel and assembly of the SMCA films.

Stress relaxation characterization and FEA

SHP films and PDMS (Sylgard 184, 20:1 crosslinking agent weight ratio) (Dow Chemical Company) films, both with 200 μm thicknesses, were each cut to a length of 30 mm and a width of 5 mm. Each sample was stretched to a tensile strain of 30% with a stretching speed of 50% strain per min, and the tensile stress at the strain was measured for 60 min by a dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) instrument (DMA Q800, TA Instruments) to characterize the stress relaxation property. The stress relaxation properties of the SHP and PDMS films were characterized at two different temperatures (25 and 37 °C) to determine the temperature dependence. On the basis of the DMA results, the mechanical behaviour of the materials was simulated by the FEA model (ANSYS, Ansys). Mesh structures for the brain-interfaced patch material were designed by modelling software (Inventor Professional, AUTODESK). The two-dimensional distribution of stress energy at the interface between the patch material and brain tissue over time was calculated and visualized to verify the dynamic behaviour of the brain-interfaced patch materials.

Ex vivo tissue-adhesion test

The bioadhesive properties of the SMCA film were comprehensively evaluated by ex vivo investigation using rodent skin and bovine brain tissue. The adhesion strength of SHP-coupled bilayer patch materials in the tensile and shear directions was investigated to compare the performance of Alg and Alg–CA hydrogels by performing a stretching test with a universal testing machine (34SC-1, Instron). Additional adhesion tests to investigate the optimal material combination of an Alg–CA adhesive and polymeric backbone substrates were also performed with a universal testing machine. For the material control test, several Alg–CA-coated bilayer platforms, with different substrate materials (PI, PDMS and SHP, thickness of 100 μm) whose backside was fixed onto a piece of PET film by commercial bonds (Loctite 401, Loctite), were attached to wet rodent skin, which was also fixed on a PET fragment. To further investigate the synergistic effect between the interfacial adhesives and backbone substrates considering dynamic behaviour under strain, another adhesion test and stress relaxation test were performed on tissue-assembled bilayer patches without a stiff PET-backing layer. To evaluate adhesion strength to tissue with curved surfaces, a shear stretching test was performed on patch materials mounted on bovine brain tissue with a stretching speed of 50% strain per min using an auto-stretcher machine (Motorizer X‐translation Stages, Jaeil Optical System). For the all-adhesive tests, tissue-interfaced hydrogel materials were swollen by silane precoated on the tissue over 1 min before stretching.

Ex vivo verification of shape-morphing property for brain conformability

The shape adaptability and brain conformality of the SMCA film were investigated by ex vivo experiments using bovine brains with uneven surface profiles. For the control test, bilayer adhesive patches, including Alg–CA/PDMS and SMCA (Alg–CA/SHP) films whose substrate materials were 100 μm thick, were mounted on a piece of bovine brain tissue with highly convolutional wrinkles and in contact with both convex sides of the tissue flexion. The bottom of the brain tissue was immersed in a silane solution, with appropriate heating applied to maintain the temperature of the tissue at 37 °C. Without any external force applied to the samples, side view images of the contact interface were obtained to evaluate the extent of shape-morphing and conformal osculation of the patch materials to the surface flexure of the brain tissue over time. Cross-sectional fluorescent images of a dyed adhesive hydrogel layer at the adjacent view were obtained to also investigate the shape-morphology of the patch materials at the brain interface and evaluate the degree of conformal osculation to the brain surface. During the ex vivo conformality tests, the bottom area of tissues was immersed in a petri dish filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (including 0.137 M sodium chloride, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 4.3 mM sodium phosphate (dibasic) and 1.4 mM potassium phosphate (monobasic)) (PBS, 1×, pH 7.4). To match the tissues’ temperature to body temperature, the PBS-filled dishes containing the tissue were loaded on a hot plate and the temperature of the tissues’ surfaces was raised to 37 °C while being monitored with a thermometer embedded in the hot plate. The cortical surface of the tissues was coated with PBS using a swab to prevent it from drying during the tests.

Fabrication of the stretchable ECoG electrode arrays

Fabrication of the stretchable ECoG electrode arrays began with spin coating of a PI (~1.5 μm thick, Sigma-Aldrich) ultrathin backbone layer on a silicon oxide wafer (SiO2, 4-inch size), followed by thermal annealing (soft baking at 150 °C for 30 min, hard baking at 250 °C for 1 h) for full crosslinking. Photolithography and lift-off in acetone defined a pattern of electrodes, interconnects and pads in the bilayer of Ti (~20 nm)/Au (~300 nm) deposited by electron beam evaporation. Another PI (~1.5 μm thick) ultrathin encapsulation layer was spin-coated on a plasma-treated bottom PI layer, followed by thermal annealing. Photolithography and lift-off in acetone defined a patterned Al (~300 nm) layer deposited by thermal evaporation. Reactive ion etching of exposed PI layers and wet etching of the Al reactive ion etching blocking layer (in APAL-1, APCT defined the pattern of PI-encapsulated electrode arrays. The completed stretchable electrode device was transfer printed onto a layer of SHP, followed by bonding an anisotropic conductive film cable to the output pads for connection to the interfacing circuit board.

Transfer printing of stretchable electrode arrays on the shape-morphing SHP and PDMS films

A piece of water-soluble tape was used to delaminate a fabricated electrode device from a wafer. The tape used to deliver the device was laminated on a substrate film with a thickness of 100 μm, dissolved in deionized water and removed from the polymer while the thin film device was transferred to a substrate layer. The transfer-printing process of ultrathin devices onto PDMS substrate is completed in the step for mechanically pressing the front of the transferred device on the sticky PDMS surface. In case of the process with the shape-morphing SHP, on the other hand, the transferred device on the SHP layer was thermally annealed in a hot plate for 10 min and gently pressed by a flat glass panel. The electrode arrays were embedded into the substrate surface, accompanied by anchoring of the device frame by the shape-morphing SHP driven by pressure and thermal energy.

FE-SEM analysis

Field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) (Inspect F50, FEI) was used to observe the interfaces between the transfer printed electrode arrays and shape-morphing SHP substrates. Each electrode-printed SHP film was cross-sectioned by using a razor blade and coated with a platinum layer before imaging. Pt is coated to the front of the samples before analysis to enable high-resolution imaging by forming electrical path to prevent electrons from being charged on the surface of the samples including insulating polymer layer (for example, PI and SHP).

Electrical and electrochemical characterization of the ECoG array printed on SHP

Stretchable electrode devices coupled with SHP substrate were laterally elongated by using an automatic stretching machine with a rate of 20% strain per min for resistance-strain characterization. The resistance of electrode devices under strain was measured using a four-point probe method (Keithley 400, Tektronix). Cyclic stretching tests were performed with a strain of 35% for 100 cycles during continuous resistance measurement. To characterize the electrochemical impedance property of stretchable electrodes under strain, electrode devices were stretched up to 50% while stretching 10% at a time by using a manual stretching stage. The impedance of the electrodes was measured using a potentiostat analyser (ZIVE) in PBS solution (1×, pH 7.4). A platinum wire and an Ag–AgCl electrode (BASiAg–AgCl and 3 M NaCl) were used as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was characterized as a function of frequency ranging from 1 Hz to 100 kHz in response to the input source with fixed amplitude correlation amplitude of 10 mV. The measured electrochemical impedance spectroscopy plots were profiled with ten points per decade.

Ex vivo verification of the cortex-interfacing performance of SMCA sensor patch devices

The brain-integration performance of the SMCA sensor was evaluated by an ex vivo test using a bovine brain model. A combined SMCA sensor patch was mounted on the whole bovine brain coated with silane to maintain wet conditions and swelled for 1 min. With the adhesive interfacial hydrogel sufficiently swelled, brain-adhesive performance was evaluated by holding and pulling the pad area of the SMCA sensor device in the transverse direction using a tweezer. To evaluate the durability of adhesion, the adhesive area of the SMCA sensor device was flushed down by a syringe-released silane stream while being pulled in the shear direction, followed by repetitive lateral pull-down motions.

Animal preparation and mobilization for in vivo experiments

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST-2021-12-159). All animals were cared for in accordance with the guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room with alternating light and dark cycles (12 h cycles, light on 07:00–19:00) and ad libitum access to water and food. Male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 6–8 weeks old were separated for acute in vivo neural recording performance test (n = 5), seizure-preceding epilepsy control test (n = 6), closed-loop dose-regulating seizure control (n = 3), long-term implantation recording performance test (n = 5) and biocompatibility evaluation (n = 16) groups for the study.

In vivo acute animal experiments for neural recording under ultrasound stimulation

Acute in vivo neural recording and tFUS stimulation tests were performed on anaesthetized rodents to evaluate the electrophysiological recording performance of each brain-interfacing platform under ultrasound stimuli conditions. For all ECoG experiments, recordings were conducted with Digital Lynx SX (Neuralynx), sampled at 8 kHz. All four types of electrode, including PDMS, SHP, Alg/SHP and SMCA sensor platforms, were tested with ketamine–xylazine cocktail-anaesthetized animals. The ECoG devices were applied alternately to the same animal to compare the difference in cortex-interfacing performance for the identical brain geometry (Supplementary Fig. 14). The order of electrodes to test was pseudo-randomly decided to minimize the effect of the level of ketamine or xylazine anaesthesia and the possible effect of previous stimulation performed on the animal. For each electrode, experiments were performed as follows: (1) soft patch electrode devices were mounted onto the opened cortical areas of both hemispheres. All kinds of ECoG devices mounted on both secured hemispheric cortical areas of anaesthetized rats were left on hold for 1 min to investigate the spontaneous brain conformality of each platform. (2) Baseline neural activity was recorded for 5 min. (3) Neural recording under tFUS stimulation follows baseline recording. Rat’s left visual cortex (anteroposterior −5.5, mediolateral −3.5) was stimulated by a mounted transducer with a sonication protocol of 1 kHz PRF, 50% duty cycle, 2.5 W cm−2 Isppa, 200 ms sonication duration for 100 trials. Neural activity was continuously recorded by electrode arrays, and ultrasound-induced ERPs were verified for each stimulation session. These tests were repetitively conducted on five animals to collect data (Supplementary Table 1). After the experiments, all animals were euthanized by CO2 gas in a hermetic chamber.

In vivo awake animal experiment for seizure monitoring with the SMCA sensor under tFUS triggered by HFO detection

Awake in vivo experiments of real-time neural recording and tFUS stimulation were performed on the seizure rodent model with the intracranially implanted SMCA sensor device. A kainic acid model was adopted to model drug-induced seizure in animals. Animals were subjected to a single therapy session to standardize the conditions for tFUS seizure control experiments. A custom code in MATLAB (R2020a, MathWorks) was used to control tFUS stimulation via the VISA interface and send events to the Neuralynx recording system to synchronize stimulation with the ECoG recording. The experimental setup and protocol were configured as follows: (1) preparing the animal acutely anaesthetized by isoflurane in an experimental chamber, an ultrasound transducer wired with a control system composed of multiple function generators and radiofrequency amplifier was mounted directly on the scalp and assembled with the headstage adaptor connected to implanted SMCA sensor devices. A 3D-printed guide system was used to fix the transducer on the scalp to stimulate the right CA3 region (anteroposterior −3.8, mediolateral 3.3), one of the region reported for kainic acid-induced epileptiform activities44,45. Ultrasound transmission gel (Ecosonic, Sanpia) was applied between the scalp surface and the transducer for acoustic coupling. The paired adaptor, coupled with a preamplifier module tethered from a neural recording instrument, was combined with the headstage adaptor. (2) After the animal woke up from anaesthesia, followed by adaptation in the chamber, the awake baseline signal was recorded over 5 min. The measured data were simultaneously uploaded to a customized ultrasound control system to establish a baseline root-mean-square (r.m.s.) power of the HFO frequency range (100–500 Hz) of the intact animal’s neural signal for judging HFO and seizure activity. (3) An acute seizure model was induced by intraperitoneal injection of kainic acid solution (5 mg kg−1, Sigma-Aldrich) into awake animals. (4) With the confirmation of seizure modelling through ictal activity and abnormal behaviour after injection (approximately 7 to 25 min after kainic acid injection, time varied among individual animals), a sequence of neural activity for the sham seizure case (no stimulation) for 3 min from the moment when the first preceding seizure HFO was detected was instrumented by SMCA sensors. The threshold of HFO detection was 9 ms consecutive blocks with mean r.m.s. + 5 s.d. (5) An ultrasound control algorithm with updated neural signal information of the animal was operated during the interictal period after the sham seizure episode to prepare for another seizure. The tFUS control algorithm was designed to trigger ultrasound stimulation by detecting pathological high-frequency components based on baseline information and to automatically terminate the operation after 3 min of stimulation. The stimulation protocol was 40 Hz PRF, 5% duty cycle and 1 W cm−2 Isppa. Simultaneous neural recording by SMCA sensors under seizure-suppressive tFUS stimulation was performed for the whole experiment. The seizure control effect of a 40 Hz PRF stimulation was quantitively evaluated with a total of six rodents with eight pairs of tFUS and sham cases. After experiments, seizure animals were euthanized by CO2 gas in a hermetic chamber after the experiments.

In vivo awake animal experiment for dose-regulating tFUS closed-loop epileptic seizure control with SMCA sensor feedback

A closed-loop algorithm was designed for dose-regulating tFUS stimulation. For dose regulation, Isppa and Ispta of the stimulation protocol was calculated as follows46:

where P is pressure, ρ is density of the propagating medium, c is speed of sound in the propagating medium t is the time and PD is pulse duration.

All stimulation protocols used in this study were below the maximum intensity (0.72 W cm−2 Ispta, with lower than 190 W cm−2 Isppa) of Food and Drug Adminstration safety guidance47.

For every experiment, the stimulation protocol was set to the default protocol (40 Hz PRF, 5% duty cycle, 1 W cm−2 Isppa, 0.05 W cm−2 Ispta) at the beginning of an experimental session. When stimulation was turned on by HFO detection, it was kept for a minimum of 30 s. If a seizure spike wave was detected, then the system measured whether it continued or was suppressed. To monitor seizure spike waves, an amplitude correlation method (modified from ref. 48) was used as follows:

where Sn is signal of the current frame.

The frame size for amplitude correlation measurement was 300 ms. The measured amplitude correlation was used to decide whether to continue, modulate or stop stimulation. For stimulation protocol modulation, the tFUS protocol was systemically modulated by following the protocol presets of each mode. The stimulation protocol preset for each mode (Ispta or Isppa control) was designed, as shown in Supplementary Table 2. For the Ispta modulation session, duty cycle was systemically increased from 5 to 15% with a step size of 5% (pulse duration was increased from 1.25 to 3.75 ms), while acoustic pressure was fixed to 283 kPa. This resulted in a change in Ispta from 0.05 to 0.15 W cm−2 with a step size of 0.05 W cm−2, while Isppa was fixed at 1 W cm−2. For the Isppa modulation session, duty cycle was systemically decreased from 5 to 3.8% with a step size of 0.6% (pulse duration was decreased from 1.25 to 0.95 ms), while acoustic pressure was increased from 283 to 322 kPa. This resulted in a change in Isppa from 1 to 1.3 W cm−2 with a step size of 0.15 W cm−2, while Ispta was fixed at 0.05 W cm−2. If the stimulation was over and a new stimulation was started with the next HFO detection, then the stimulation protocol was reset to the default protocol. Since seizure symptoms vary and there is a possibility that the protocol modulation range that the system provides is not optimal for some individuals, there would still be failed cases where seizure suppression is not achieved within the prepared protocol modulation scenario. If the seizure becomes severe and reaches upper thresholds during stimulation, just in case, then the system decreases intensity or stops the operation of tFUS for the safe control of the seizure. After demonstrations, seizure animals were CO2-euthanized after the experiments.

Data processing and statistical analysis for in vivo animal experiments

Data processing and statistical analysis were performed with custom MATLAB codes. For acute material tests, a total of 60 electrodes from each material sample were randomly selected from all channels of animals to match the sample size. The time-locked signal of the baseline and tFUS stimulation period of ECoG oscillations synchronized with the stimulation events were collected from each trial. Baseline signals of each trial were collected from −300 to −100 ms, while the tFUS stimulation period was 0 to 200 ms from the start of tFUS stimulation. For baseline and tFUS periods, normalized PSD of artefacts (60 Hz line noise or noise from 1 kHz PRF) was obtained by short-time Fourier transform and grand averaged for each electrode. For seizure suppression experiments with awake freely moving animals, a notch filter with a cut-off frequency of 60 Hz was used to remove line noise from the data. To remove movement noises, movement timepoints were collected during the experiment by at least two trained researchers with monitoring videos. Movement timepoints were cross-checked with animal behaviour video recordings for validation. PSD of movement timepoints were replaced with averaged PSDs collected from before the starting point of the movement, or after the end point of movement of each frequency. Two seconds of data were collected from before or after movement period. To analyse the effect of 3 min of tFUS stimulation with fixed protocols, PSD performed by short-time Fourier transform was measured from each channel. The PSDs of delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) oscillations were measured and z scored or normalized by the baseline for z score topography and statistical analysis. For z score topography, a total of 5 min of data, including 1 min pre-HFO, was averaged by a 30 s temporal window for each channel. Topography was performed with the EEGLAB toolbox in MATLAB. For statistical analysis, a total of 5 min of data, including 1 min pre-HFO, was averaged by a 20 s temporal window, and the normalized PSD of all channels was averaged. To visualize the closed-loop tFUS stimulation, an ECoG signal synchronized with time-locked events of tFUS device control was collected from each representative case. The normalized PSD was calculated for the channel placed on the posterior parietal cortex (channel 9). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for statistical tests of the acute material test and awake seizure suppression experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The customized MATLAB codes used for in vivo demonstration and analysing ECoG signals in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fisher, R. S. & Velasco, A. L. Electrical brain stimulation for epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10, 261–270 (2014).

Ryvlin, P. et al. Neuromodulation in epilepsy: state-of-the-art approved therapies. Lancet Neurol. 20, 1038–1047 (2021).

Min, B. K. et al. Focused ultrasound-mediated suppression of chemically-induced acute epileptic EEG activity. BMC Neurosci. 12, 23 (2011).

Chen, S. G. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound pulsation suppresses pentylenetetrazol induced epilepsy in vivo. Brain Stimul. 13, 35–46 (2020).

Chu, P. C. et al. Pulsed-focused ultrasound provides long-term suppression of epileptiform bursts in the kainic acid-induced epilepsy rat model. Neurotherapeutics 19, 1368–1380 (2022).

Murphy, K. R. et al. A tool for monitoring cell type–specific focused ultrasound neuromodulation and control of chronic epilepsy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2206828119 (2022).

Lee, C. C. et al. Pilot study of focused ultrasound for drug‐resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia 63, 162–175 (2022).

Berényi, A. et al. Closed-loop control of epilepsy by transcranial electrical stimulation. Science 337, 735–737 (2012).

Ouyang, W. et al. A wireless and battery-less implant for multimodal closed-loop neuromodulation in small animals. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1252–1269 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Syringe-injectable electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 629–636 (2015).

Zhao, S. et al. Tracking neural activity from the same cells during the entire adult life of mice. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 696–710 (2023).

Zijlmans, M. et al. Changing concepts in presurgical assessment for epilepsy surgery. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 594–606 (2019).

Staba, R. J. et al. Quantitative analysis of high-frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) recorded in human epileptic hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 1743–1752 (2002).

Viventi, J. et al. Flexible, foldable, actively multiplexed, high-density electrode array for mapping brain activity in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1599–1605 (2011).

Chiang, C.-H. et al. Development of a neural interface for high-definition, long-term recording in rodents and nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaay4682 (2020).

Khodagholy, D. et al. NeuroGrid: recording action potentials from the surface of the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 310–315 (2015).

Lee, W. et al. Transparent, conformable, active multielectrode array using organic electrochemical transistors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10554–10559 (2017).

Tchoe, Y. et al. Human brain mapping with multithousand-channel PtNRGrids resolves spatiotemporal dynamics. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabj1441 (2022).

Vomero, M. et al. Glassy carbon electrocorticography electrodes on ultra-thin and finger-like polyimide substrate: performance evaluation based on different electrode diameters. Materials 11, 2486 (2018).

Vomero, M. et al. Conformable polyimide-based μECoGs: bringing the electrodes closer to the signal source. Biomaterials 255, 120178 (2020).

Besson, P. et al. Small focal cortical dysplasia lesions are located at the bottom of a deep sulcus. Brain 131, 3246–3255 (2008).

Kim, D.-H. et al. Dissolvable films of silk fibroin for ultrathin conformal bio-integrated electronics. Nat. Mater. 9, 511–517 (2010).

Shi, Z. et al. Silk‐enabled conformal multifunctional bioelectronics for investigation of spatiotemporal epileptiform activities and multimodal neural encoding/decoding. Adv. Sci. 6, 1801617 (2019).

Tringides, C. M. et al. Viscoelastic surface electrode arrays to interface with viscoelastic tissues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1019–1029 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Topological supramolecular network enabled high-conductivity, stretchable organic bioelectronics. Science 375, 1411–1417 (2022).

Tybrandt, K. et al. High‐density stretchable electrode grids for chronic neural recording. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706520 (2018).

Fallegger, F. et al. MRI‐Compatible and conformal electrocorticography grids for translational research. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003761 (2021).

Song, S. et al. Deployment of an electrocorticography system with a soft robotic actuator. Sci. Robot. 8, eadd1002 (2023).

Mueller, J. et al. Simultaneous transcranial magnetic stimulation and single-neuron recording in alert non-human primates. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1130–1136 (2014).

Kim, M. G. et al. Image-guided focused ultrasound modulates electrically evoked motor neuronal activity in the mouse peripheral nervous system in vivo. J. Neural Eng. 17, 026026 (2020).

Suarez-Castellanos, I. M. et al. Spatio-temporal characterization of causal electrophysiological activity stimulated by single pulse focused ultrasound: an ex vivo study on hippocampal brain slices. J. Neural Eng. 18, 026022 (2021).

Sarica, C. et al. Toward focused ultrasound neuromodulation in deep brain stimulator implanted patients: ex-vivo thermal, kinetic and targeting feasibility assessment. Brain Stimul. 15, 376–379 (2022).

Airan, R. D. et al. Noninvasive targeted transcranial neuromodulation via focused ultrasound gated drug release from nanoemulsions. Nano Lett. 17, 652–659 (2017).

Deng, J. et al. Electrical bioadhesive interface for bioelectronics. Nat. Mater. 20, 229–236 (2021).

Choi, H. et al. Adhesive bioelectronics for sutureless epicardial interfacing. Nat. Electron. 6, 779–789 (2023).

Lee, C. et al. Bioinspired, calcium-free alginate hydrogels with tunable physical and mechanical properties and improved biocompatibility. Biomacromolecules 14, 2004–2013 (2013).

Kang, J. et al. Tough and water-insensitive self-healing elastomer for robust electronic skin. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706846 (2018).

Younan, Y. et al. Influence of the pressure field distribution in transcranial ultrasonic neurostimulation. Med. Phys. 40, 082902 (2013).

Yang, K. et al. Polydopamine-mediated surface modification of scaffold materials for human neural stem cell engineering. Biomaterials 33, 6952–6964 (2012).

Blackmore, J. et al. Ultrasound neuromodulation: a review of results, mechanisms and safety. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 45, 1509–1536 (2019).

Buzsaki, G. & Draguhn, A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 304, 1926–1929 (2004).

Stypulkowski, P. H. et al. Brain stimulation for epilepsy–local and remote modulation of network excitability. Brain Stimul. 7, 350–358 (2014).

Aubry, J. F. et al. ITRUSST consensus on biophysical safety for transcranial ultrasonic stimulation. Preprint at arXiv arXiv:2311.05359 (2023).

Ben‐Ari, Y. E. et al. Long‐lasting modification of the synaptic properties of rat CA3 hippocampal neurones induced by kainic acid. J. Physiol. 404, 365–384 (1988).

Mouri, G. et al. Unilateral hippocampal CA3-predominant damage and short latency epileptogenesis after intra-amygdala microinjection of kainic acid in mice. Brain Res. 1213, 140–151 (2008).

Fomenko, A. et al. Low-intensity ultrasound neuromodulation: an overview of mechanisms and emerging human applications. Brain Stimul. 11, 1209–1217 (2018).

FDA Guidance. Information for Manufacturers Seeking Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers (FDA, 2019); www.fda.gov/media/71100/download

White, A. M. et al. Efficient unsupervised algorithms for the detection of seizures in continuous EEG recordings from rats after brain injury. J. Neurosci. Methods 152, 255–266 (2006).

Mouse skull and brain. Open source for 3D model. Thingverse www.thingiverse.com/thing:3079327 (2018).

Lab rat. Open source for 3D model. Sketchfab https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/lab-rat-9f1e720a87ac40e7bda7096d760cced7 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was dominantly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (grant nos. 2020R1C1C1005567 (D.S.), 2022M3E5E9018583 (D.S.), RS-2023-00208262 (M.S.), 2021R1A2C2008829 (Hyungmin Kim)) and Institute for Basic Science (grant no. IBS-R015-D1). This work was also supported by MSIT, Korea, under the ICT Creative Consilience Program (grant no. IITP-2023-2020-0-01821) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information and Communications Technology Planning and Evaluation). This study was also partially funded by KIST Institutional Program (grant no. 2E33141) and the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (grant no. 2022M3E5E9016506 (J. Kim)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. and Hyungmin Kim conceived the project and M.S., Hyungmin Kim and D.S. supervised the project. S.L. and J. Kum conducted all experiments with assistance from co-authors. S.K. and J.H.C. assisted materialization and ex vivo adhesion test. H.J. performed the mechanical simulation and analysed the dynamic stress distribution. S.A. assisted harvesting rodents’ brain tissues for histological analysis. S.J.C., Hyeok Kim and H.-S.H. conducted histological imaging and provided the interpretation of the biological and histological data. W.L. and K.J.Y. provided technical advice. D.S., Hyungmin Kim, M.S. and J. Kim provided financial support to the project. S.L., J. Kum, M.S., Hyungmin Kim and D.S. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all the co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Electronics thanks Xinge Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Immunohistology analysis of SMCA sensor-attached rodent brain tissue. The fluorescence microscopic images show double labelling for an immunofluorescent astrocytic marker GFAP and microglia/macrophage marker Iba-1 at the implantation sites of both positive control (Sham) and SMCA sensor (SMCA). Cell nuclei were DAPI-stained for visualization.