Abstract

Analogue computing uses the physical behaviours of devices to provide energy-efficient arithmetic operations. However, scaling up analogue computing platforms by simply increasing the number of devices leads to challenges such as device-to-device variation. Here we report scalable analogue computing and neural networks in the synthetic frequency domain using an integrated nonlinear phononic platform on lithium niobate. This synthetic-domain computing is robust to device variations, as vectors and matrices are concurrently encoded at different frequencies within a single device, achieving a high throughput per area. Leveraging inherent nonlinearities, our device-aware neural network can perform a four-class classification task with an accuracy of 98.2%. The nonlinear phononic computing hardware also maintains consistent performance over a wide operational temperature range (characterized up to 192 °C). Our synthetic-domain computing combines single-device parallelism, inherent nonlinearity and environmental stability, and could be of use in edge computing applications in which power efficiency and environmental resilience are crucial.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data for the plots are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29376791 (ref. 63). Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Source code implementing the device-aware neural networks is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29376791 (ref. 63).

References

Small, J. S. General-purpose electronic analog computing: 1945-1965. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 15, 8–18 (1993).

Sebastian, A., Le Gallo, M., Khaddam-Aljameh, R. & Eleftheriou, E. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 529–544 (2020).

Yao, P. et al. Fully hardware-implemented memristor convolutional neural network. Nature 577, 641–646 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Memristor-based hardware accelerators for artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng 1, 286–299 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Artificial neuronal devices based on emerging materials: neuronal dynamics and applications. Adv. Mater. 35, 2205047 (2023).

Gokmen, T. & Haensch, W. Algorithm for training neural networks on resistive device arrays. Front. Neurosci. 14, 103 (2020).

Xiao, T. P., Bennett, C. H., Feinberg, B., Agarwal, S. & Marinella, M. J. Analog architectures for neural network acceleration based on non-volatile memory. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 011309 (2020).

Rasch, M. J., Carta, F., Fagbohungbe, O. & Gokmen, T. Fast and robust analog in-memory deep neural network training. Nat. Commun. 15, 7133 (2024).

Noh, K. et al. Retention-aware zero-shifting technique for Tiki-Taka algorithm-based analog deep learning accelerator. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl3350 (2024).

Byun, K. et al. Recent advances in synaptic nonvolatile memory devices and compensating architectural and algorithmic methods toward fully integrated neuromorphic chips. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200884 (2023).

Gong, N. et al. Deep learning acceleration in 14nm CMOS compatible ReRAM array: device, material and algorithm co-optimization. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 33.37.31–33.37.34 (IEEE, 2022).

Yasuda, H. et al. Mechanical computing. Nature 598, 39–48 (2021).

Mei, T. & Chen, C. Q. In-memory mechanical computing. Nat. Commun. 14, 5204 (2023).

Wetzstein, G. et al. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature 588, 39–47 (2020).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photon. 15, 102–114 (2021).

Hamerly, R., Bernstein, L., Sludds, A., Soljačić, M. & Englund, D. Large-scale optical neural networks based on photoelectric multiplication. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021032 (2019).

Pai, S. et al. Experimentally realized in situ backpropagation for deep learning in photonic neural networks. Science 380, 398–404 (2023).

Filipovich, M. J. et al. Silicon photonic architecture for training deep neural networks with direct feedback alignment. Optica 9, 1323–1332 (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. 120 GOPS photonic tensor core in thin-film lithium niobate for inference and in situ training. Nat. Commun. 15, 9081 (2024).

Buckley, S. M., Tait, A. N., McCaughan, A. N. & Shastri, B. J. Photonic online learning: a perspective. Nanophotonics 12, 833–845 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Large-scale photonic chiplet Taichi empowers 160-TOPS/W artificial general intelligence. Science 384, 202–209 (2024).

Feng, H. et al. Integrated lithium niobate microwave photonic processing engine. Nature 627, 80–87 (2024).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. An optical neural chip for implementing complex-valued neural network. Nat. Commun. 12, 457 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. All-optical machine learning using diffractive deep neural networks. Science 361, 1004–1008 (2018).

Fu, T. et al. Photonic machine learning with on-chip diffractive optics. Nat. Commun. 14, 70 (2023).

Zhou, T. et al. Large-scale neuromorphic optoelectronic computing with a reconfigurable diffractive processing unit. Nat. Photon. 15, 367–373 (2021).

Wang, Z., Chang, L., Wang, F., Li, T. & Gu, T. Integrated photonic metasystem for image classifications at telecommunication wavelength. Nat. Commun. 13, 2131 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. 11 TOPS photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks. Nature 589, 44–51 (2021).

Ashtiani, F., Geers, A. J. & Aflatouni, F. An on-chip photonic deep neural network for image classification. Nature 606, 501–506 (2022).

Feldmann, J., Youngblood, N., Wright, C. D., Bhaskaran, H. & Pernice, W. H. P. All-optical spiking neurosynaptic networks with self-learning capabilities. Nature 569, 208–214 (2019).

Dong, B. et al. Higher-dimensional processing using a photonic tensor core with continuous-time data. Nat. Photon. 17, 1080–1088 (2023).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photon. 11, 441–446 (2017).

Nahmias, M. A. et al. An integrated analog O/E/O link for multi-channel laser neurons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 151109 (2016).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Single-chip photonic deep neural network with forward-only training. Nat. Photon. 18, 1335–1343 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Image sensing with multilayer nonlinear optical neural networks. Nat. Photon. 17, 408–415 (2023).

Pintus, P. et al. Integrated non-reciprocal magneto-optics with ultra-high endurance for photonic in-memory computing. Nat. Photon. 19, 54–62 (2025).

Fan, L., Wang, K., Wang, H., Dutt, A. & Fan, S. Experimental realization of convolution processing in photonic synthetic frequency dimensions. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi4956 (2023).

Zhao, H., Li, B., Li, H. & Li, M. Enabling scalable optical computing in synthetic frequency dimension using integrated cavity acousto-optics. Nat. Commun. 13, 5426 (2022).

Buddhiraju, S., Dutt, A., Minkov, M., Williamson, I. A. D. & Fan, S. Arbitrary linear transformations for photons in the frequency synthetic dimension. Nat. Commun. 12, 2401 (2021).

Fan, L. et al. Multidimensional convolution operation with synthetic frequency dimensions in photonics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 034088 (2022).

Basani, J. R., Heuck, M., Englund, D. R. & Krastanov, S. All-photonic artificial-neural-network processor via nonlinear optics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 014009 (2024).

Davis III, R., Chen, Z., Hamerly, R. & Englund, D. RF-photonic deep learning processor with Shannon-limited data movement. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt3558 (2025).

Gong, S., Lu, R., Yang, Y., Gao, L. & Hassanien, A. E. Microwave acoustic devices: recent advances and outlook. IEEE J. Microw. 1, 601–609 (2021).

Lu, R. & Gong, S. RF acoustic microsystems based on suspended lithium niobate thin films: advances and outlook. J. Micromech. Microeng 31, 114001 (2021).

Marpaung, D., Yao, J. & Capmany, J. Integrated microwave photonics. Nat. Photon. 13, 80–90 (2019).

Zhu, D. et al. Integrated photonics on thin-film lithium niobate. Adv. Opt. Photon. 13, 242–352 (2021).

Shao, L. et al. Phononic band structure engineering for high-Q gigahertz surface acoustic wave resonators on lithium niobate. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 014022 (2019).

Shao, L. et al. Microwave-to-optical conversion using lithium niobate thin-film acoustic resonators. Optica 6, 1498–1505 (2019).

Cho, Y. & Yamanouchi, K. Nonlinear, elastic, piezoelectric, electrostrictive, and dielectric constants of lithium niobate. J. Appl. Phys. 61, 875–887 (1987).

Xiao, H., Rasul, K. & Vollgraf, R. Fashion-MNIST: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07747 (2017).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Shao, L. et al. Electrical control of surface acoustic waves. Nat. Electron. 5, 348–355 (2022).

de Castilla, H., Bélanger, P. & Zednik, R. J. High temperature characterization of piezoelectric lithium niobate using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy resonance method. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 244103 (2017).

Hackett, L. et al. Giant electron-mediated phononic nonlinearity in semiconductor–piezoelectric heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 23, 1386–1393 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. Sub-terahertz electromechanics. Nat. Electron. 6, 301–306 (2023).

Liu, B. et al. Surface acoustic wave devices for sensor applications. J. Semicond. 37, 021001 (2016).

Zhou, F. & Chai, Y. Near-sensor and in-sensor computing. Nat. Electron. 3, 664–671 (2020).

Thomas, J. G. et al. Spectral interferometry-based microwave-frequency vibrometry for integrated acoustic wave devices. Optica 12, 935–944 (2025).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396 (1997).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Shao, L. Code and plot data for “Synthetic-domain computing and neural networks using lithium niobate integrated nonlinear phononics”. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29376791.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Rohde & Schwarz for support with the microwave instrumentation. Device fabrication was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (CNMS2022-B-01473 and CNMS2024-B-02643, L.S.), which is a US Department of Energy, Office of Science User Facility. Research was partially supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) under grant no. W911NF-23-1-0235 (L.S.) and award no. FA9550-22-1-0548 (W.X.), and by Commonwealth Cybersecurity Initiative in Virginia (W.X.). Development of the optical vibrometer was partially supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) OPTIM program (HR00112320031, L.S.). Development of the nonlinear phononic device and material calculation were partially supported by DARPA SynQuaNon DO program under agreement no. HR00112490314 (L.S.). The work at the University of Texas at Dallas is supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) under grant no. N00014-23-1-2020 (W.G.V.). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the United States government. No official endorsement should be inferred. Approved for public release.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J., W.X. and L.S. conceptualized the idea. J.J., Z.X. and L.S. performed the numerical simulations. J.J., Z.X. and L.S. also fabricated the devices with processes developed by I.I.K. and B.R.S. W.X. and M.J. designed the computing and neural network architectures. L.S. implemented and trained the neural networks. J.J. performed the measurements and analysed the data with the help of L.S., J.G.T. and Y.Z. performed the optical vibrometer measurements. P.B., M.S. and W.G.V. performed the first-principles calculations. All authors analysed and interpreted the results. J.J. prepared the manuscript with revisions from all authors. L.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Electronics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

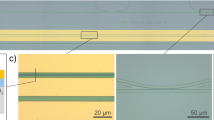

Extended Data Fig. 1 Characterizations of our phononic device.

a, Optical microscopic images of devices used for device characterization. Fundamental IDT pair is used in b, second-order IDT pair is used in c, nonlinear computing unit is used in d-f. b, Transmission (S21) and reflection (S11) spectra of the fundamental IDT pair. The gap between the IDT pair is 20 µm. The transmission S21 at 1023 MHz is -22 dB, leading to a power conversion efficiency of about 8.0%. c. Transmission (S21) and reflection (S11) spectra of the second-order IDT pair. The gap between the IDT pair is 100 µm. Due to weak reflections of IDT, oscillation pattern in S21 is observed with a free spectral range (FSR) of 15 MHz, close to a FSR of 18.5 MHz for a phononic cavity formed by the IDT pair. We estimate that the power conversion efficiency is 3.2% for the second-order IDT. d. The measured output spectrum from Port 3, showing both fundamental and second-order signals. An input signal of 0 dBm at 1,023 MHz is applied at Port 1. e. Output powers of second-harmonic generation (SHG) at different input frequencies. The input power is 0 dBm. Black dots are measured data, and the blue curve is a Lorentzian fitting to the data. The fitting shows a full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) bandwidth of 1.20 MHz. f. The input-output power relationship of SHG. Linear scale plot in Inset. The extracted cable-to-cable nonlinear conversion efficiency is 0.063%/W. Considering the fundamental (second-order) IDT conversion efficiency is about 8.0% (3.2%), the on-chip nonlinear conversion efficiency at the peak frequency is estimated as 24.6%/W.

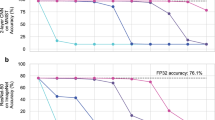

Extended Data Fig. 2 Comparison of performance metrics among 6 different devices from 3 nanofabrication rounds (denoted as R1, R2, and R3).

Matrix multiplication of two randomly generated 8×8 matrices is used as a benchmark. a, The peak second-harmonic generation (SHG) power for different devices. b, The frequency of peak SHG for different devices. c, Normalized mean-square error (NMSE) of measured matrices against expected matrices. The carrier microwave frequency is adjusted for each device to near its peak SHG. NMSE follows the χ2 distribution, the error bars represent 90% confidence interval (5% on both ends) and the dots represent the mean value of fitted χ2 distribution. Fifty (50) matrix multiplications are measured for each device.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Ten-digits MNIST classification using our device-aware neural network.

a, Measured spectrum of the input and output of the first layer. The input includes the image pixels (28×28) and 2,216 trained parameters with df = 100 Hz and f0 = 1,023.50 MHz. The output has 6,000 elements and the first 3,783 elements are fed into a digital computer to multiply with a 10 × 3,783 matrix. b, Confusion matrices of the calculated and experimentally measured inference results of the first 1,000 validation images, showing similar performance of inference with a calculated (partially experimental) accuracy of 94.6% (94.5%). c, NMSE of measured results of the first layer compared to calculated results.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Ten-digits MNIST classification using kernel-based convolution neural network fit on our device.

a, Measured spectrum of the input and output of the first layer. The input includes the image pixels (28×28) and 128 non-zero parameters (8 kernels, each has 16 non-zero parameters) with df = 50 Hz and f0 = 1,022.92 MHz. The output includes (2×784-1 = 1,567) elements of quadratic operation of input image and 8 convoluted features (each has 847 parameters). The gray curve at the second-order frequency is self-convolutions of kernels and will be multiplied by zeros in the fully connected layer. The first 8,480 elements are fed into a digital computer to multiply with a 10 × 8,480 matrix. b, Confusion matrices of the calculated and experimentally measured inference results of the first 1,000 validation images, showing similar performance of inference with a calculated (partially experimental) accuracy of 95.1% (95.0%). c, NMSE of measured results of the first layer compared to calculated results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Demonstration of difference frequency operation mode (DFOM).

a, The principle of DFOM in the synthetic domain. Input vectors \(\mathop{a}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) and \(\mathop{c}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) are encoded in the lower-half of fundamental frequency band and second-order frequency band, respectively. df is the frequency spacing between two neighboring frequency bins. The difference frequency generation process of our phononic device generates cross-convolutions \(\mathop{B}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) at the upper-half of the fundamental frequency band. μ is the nonlinear conversion efficiency of the device. \({f}_{{a}_{0}}+{f}_{{B}_{0}}={f}_{{c}_{0}}\). b, Input 1 (input 2) is injected into our device through a fundamental IDT at Port 1 (a second-order IDT at Port 3), while the output is measured at the other fundamental IDT at Port 2. c, Measured spectrum of randomly generated 4×4 input matrices U (V), which are encoded in the fundamental frequency band (second-order frequency band) row by row (column by column) with df = 100 Hz, \({f}_{{a}_{0}}\) = 1,022.972 MHz, and \({f}_{{B}_{0}}\) = 1,023.028 MHz. d, Measured output of the product matrices W=UV in the fundamental frequency band. e, Input matrices U and V, the measured and expected matrix W. Matrices W are normalized. Numbers are rounded to two decimal places. f, Normalized mean-square error (NMSE) of measured matrices when two randomly generated N×N matrices are multiplied, N = 4, 8, and 16. For each N, 50 independent cases are measured.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Cascaded computing.

Our computing units can be cascaded by interleaving sum frequency operation mode (SFOM) and difference frequency operation mode (DFOM). This process implements the multiplication of three matrices, Y=U−1 U V. First, the multiplication W=UV is performed using SFOM, where the inputs U and V are encoded in the fundamental frequency band, and the output W shows up in the second-order frequency band. The output W is routed into DFOM as an input signal X, for the operation Y = U−1 X. Note that the cascaded signals remain at the same frequency bins and no digital signal processing is needed. By encoding U−1 into the fundamental frequency band as another input, the output Y is obtained at the fundamental frequency band. Numbers are rounded to two decimal places. The measured Y closely matches the input V, demonstrating a high fidelity in cascaded computing. We note that we detected and regenerated the analog signal in cascade, but no additional digital processing is applied; this is due to the technical limitations of our experimental setup that prevent simultaneous measurement of two devices.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Demonstration of peak computing capabilities.

The convolution process of a 128-by-128-pixel image is used to demonstrate the computing area density and power efficiency of our device. a, Both image pixels (128×128) and kernel elements (3×3) are encoded in the fundamental frequency band row by row with df = 20 Hz. During the encoding process, the image (kernel) is zero-padded and flattened into a 130×130 (3×130) vector to avoid mixing of pixels in neighboring rows. The grayscale of the pixel is represented by the amplitude of each frequency bin. The output image is retrieved from cross-convolution in the second-order frequency band. b, The measured time-domain input electric signal in a period. The peak instantaneous power is 120 mW and the average power 9.75 mW. c, The image is convoluted with two 3×3 kernels to highlight horizontal/vertical edges, which is then combined to show edge highlighting. The measured images after convolution agree with the expected images. f0 = 1,022.2381 MHz, fC0 = 2,045.173 MHz. The photo of Virginia Tech Torgersen bridge used in this figure is taken by the authors.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Note 1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, J., Xi, Z., Thomas, J.G. et al. Synthetic-domain computing and neural networks using lithium niobate integrated nonlinear phononics. Nat Electron 8, 698–708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-025-01436-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-025-01436-9