Abstract

The skin, the body’s largest organ, has a heterogeneous structure with various cell types and tissue layers. In vivo noninvasive 3D volumetric imaging with multi-contrast, high resolution, a large field-of-view (FOV), and no-motion artifacts is crucial for studying skin biology and diagnosing/evaluating diseases. Traditionally high-resolution in vivo skin microscopy methods capture images in the en-face (xy) plane parallel to the skin surface but are affected by involuntary motion, particularly during large-area volumetric data acquisition using xy-z mosaicking. In this work, we developed an xz-y imaging method that acquires images in the vertical (xz) plane and extends the FOV by moving the skin laterally along the y-direction. This approach is conceived based on our observation that involuntary skin movements are mostly along the vertical direction. Combined with a unique motion correction method, it enables 3D image reconstruction with subcellular resolution and an extended FOV close to a centimeter (8 mm). A multimodality microscopy system using this method provides simultaneous reflectance confocal, two-photon excited fluorescence, and second harmonic generation imaging, enabling multi-contrast capabilities. Using this system, we captured histology-like features of normal skin, vitiligo, and melanoma, demonstrating its potential for in vivo skin biology studies, clinical diagnosis, treatment planning and monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In vivo, noninvasive microscopy imaging plays an important role in normal skin evaluation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, skin disease assessment7,9, and cancer diagnosis10,11,12,13. Optical coherence tomography (OCT), reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), and multiphoton microscopy (MPM) are three popular imaging methods that are intensively used. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses. A typical OCT imaging system has a large field of view and mm order imaging depth. It can generate 3D volumetric data at a fast speed. However, its relatively low spatial resolution (tens of microns) hampers its capability to differentiate single cells. Imaging contrast of OCT originates from the variation of tissue refractive index. It provides tissue structural information but no molecule-specific information. RCM’s contrast is also based on the tissue refractive index fluctuations. High numeric aperture (NA) objective and confocal detection configuration enable RCM to have a subcellular resolution (micron) and optical sectioning capability within a depth of about 200 µm. Different from OCT and RCM, MPM provides molecular-specific information based on two-photon excitation fluorescence (TPF) signals of cellular and tissue endogenous fluorophores and second harmonic generation (SHG) signals of collagen fibers. MPM imaging also has the highest resolution (sub-microns) and best sectioning capability among the three methods but they typically have a slower imaging speed and a smaller field of view.

Volumetric imaging with high resolution, large field of view, and high speed is a key research focus for noninvasive microscopy skin imaging method development. This is crucial because the skin, as the body’s largest organ, is spatially heterogeneous, composing distinct layers and diverse cell types essential to its function. Volumetric imaging that covers a large area can give a precise and comprehensive evaluation of the skin (normal or diseased)14,15. High-resolution 3D imaging enables a clear understanding of the location, morphology, and function of target cells, as well as their interactions with surrounding tissue components5,6,16. High-speed imaging enhances practical in vivo applications, making the technique more efficient and feasible15,17,18. Fast, high-resolution, large-area volumetric imaging could enable standardized clinical measurements, eliminating the need for preselecting imaging depth - a current challenge in clinical applications14.

Several works have been reported in pursuit of the above goals, each tailored to specific applications. Line field confocal OCT that combines the high lateral resolution of confocal detection and high vertical resolution of line-filed OCT has achieved volumetric imaging of normal skin and skin diseases in an FOV of 1.2 mm×0.5 mm × 0.5 mm19. The volume was constructed by stacking horizontal frames (xy-z stack) at a frame rate of 8 frames per second16.

RCM volumetric imaging can also be acquired in a FOV of 500 µm × 500 µm × 200 µm using xy-z stacking. Larger FOV has been achieved through tile mosaicing or video mosaicing of multiple xy images20. Strip mosaicing has been used in ex vivo applications to enhance acquisition speed21. However, these large FOV images are acquired just in one or several selected depths, or with a large z step size (as large as 10 µm), lacking detailed full-depth 3D information over a wide area. Consequently, accurate selection of imaging depth is crucial for diagnosis and relies heavily on the clinician’s experience14.

MPM skin imaging is typically acquired in a small field (<250 µm × 250 µm) with high cellular resolution but a slow imaging speed (several seconds per frame), represented by the commercial systems from Jenlab6,22. Volumetric imaging is also based on xy-z stacking. Two to four small ROI volume stacks (130 µm × 130 µm × 200 µm, z step size 2.3 µm) have been shown to give representative results for skin aging quatification6. Balu et al. developed a more advanced MPM imaging system that features large FOV, high imaging speed, and enhanced molecular contrast23. MPM images of a size of 1.2 × 1 cm2 have been reported for ex vivo samples by strip mosaicing at selected depths. In vivo volumetric imaging results were also reported that cover an area of 3.2 mm × 3.2 mm by tile mosaicing of z stacks (each z stack contains only 12 x-y images with a step size of 10 µm)15.

The above-mentioned volumetric imaging method is all based on xy-z stacking, which we think is one key limitation factor that prevents fast-speed, high-resolution, large FOV, motion-tolerant volumetric imaging of skin in vivo. When performing in vivo imaging, involuntary motion from breathing, heartbeat, and muscle contraction must be considered. We observed that the involuntary skin motions are mostly up and down along the vertical z-direction in the xz plane. This is clearly visualized in Supplementary Movies 1 and 2. Supplementary Movie 1 was taken by imaging in the en-face (horizontal) x-y plane. The contents of the image frames are constantly changing due to the involuntary motion in the z-direction, making it difficult to reconstruct a correct 3D volume. Supplementary Movie 2 was taken by imaging in the vertical x-z plane. Now the contents of the image frames remain the same although they are moving up and down, but never moving outside of the imaging plane, making it possible to reconstruct a correct 3D volume with linear shifting to accurately correct the motion artifacts.

When performing xy-z stacking volumetric imaging, the involuntary motion, with its moving direction along the z-direction, could cause the depth information of the acquired xy images to be inaccurate and information from different depths mingled together in the z stack. As a result, it will be very challenging to retrieve reliable data from the tile mosaiced z stacks without depth mismatch. In addition, tile mosaicing needs to frequently move and stop the translation stage which slows down the data acquisition speed. We hereby propose an alternative volumetric imaging method that is based on the y-stacking of xz vertical sectioning images. It is suitable for laser scanning-based microscopy imaging modalities, including both RCM and MPM. This method offers at least three key benefits that can significantly enhance large FOV volumetric imaging and potentially accelerate the clinical adoption of optical biopsy techniques.

-

1)

It is motion tolerant. When imaging in the xz plane at a high frame rate (15 frames/s or higher), there will be minimum motion artifact within each frame. And the skin surface position can also be recorded in each frame making it possible to reconstruct a 3D volume through linear shifting of each frame to correct the up-and-down motion artifacts between frames.

-

2)

It easily achieves an extended field of view by translating the skin along the y-direction. No stitching in the y-axis is needed. This type of “volumetric strip mosaicking” makes large FOV volumetric imaging much faster than tile mosaicking of z stacks just like 2D strip mosaicking is faster than tile mosaicking21.

-

3)

The balance between the high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and high volumetric imaging speed can be adjusted conveniently by changing the translation speed in the y-direction without affecting the motion-correction capability. When needed, employing a slower translation speed and the same frame rate, more frames can be acquired within the same y-translation distance. This way, neighbor frames can be averaged after motion correction to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. In contrast, for xy-z stacking imaging, frame averaging is prone to motion artifacts along the z-direction, leading to blurred images.

Direct xz plane imaging has been reported by ourselves24 in 2011 and others later for RCM and MPM. Mansoor et al. reported a vertical scanning method for RCM using magnetically driven optical fiber and microlens for x and z scanning24. Thomas et al. reported vertical plane MPM imaging results from a murine cancer model using a Galvo mirror and a translation stage for x and z scanning respectively25. Czekalla et al. reported a wide field vertical plane MPM imaging method using a linear piezo to move a customized lightweight objective in z-direction together with the scan lens for wide field x scanning26. Recently Enspectra Health, Inc. has developed a commercial handheld probe that combines RCM and MPM for direct vertical plane imaging. A compact design was achieved by using an ultrafast fiber laser, MEMs scanner, internal depth-focusing through changing the beam divergence, and a customized objective lens. The probe achieves an imaging speed of 4.5 frames per second in low-resolution mode and 0.39 frames per second in high-resolution mode27. However, these methods fail to meet the demands for fast volumetric imaging due to their slow frame rates. Additionally, the use of customized components makes them inconvenient to apply across different platforms.

Our direct vertical plane (xz) imaging is realized by a fast resonance scanning mirror in the x-direction in combination with the objective scanning in the depth (z-) direction by a piezo positioner. The half-video rate vertical scanning speed can be reached to minimize the in-frame motion. The small xz field of view limited by the scanning angle is extended by replacing the y-scanning axis with lateral skin translation (along the y-direction) to reach several millimeters. A motion-correction method was then developed for tissue volume reconstruction. In this way, fast, high-resolution, and motion-tolerant volumetric imaging of in vivo skin was achieved with an extended field of view.

We initiated and realized the co-registration of three imaging modalities – RCM, TPF, and SHG in 2013 – providing three distinct contrasts simultaneously, offering complementary tissue information28. In the epidermis, RCM has a strong signal and helps visualize cell junctions and melanin caps, while TPF imaging shows cell cytoplasm and nucleus28. In the dermis, SHG imaging visualizes collagen fibers, while TPF shows elastic fibers. All the three imaging modalities have been incorporated into the current work. Once a volumetric dataset has been acquired using our method, the data may be viewed in any plane. For example, the data may be viewed in vertical planes to observe low-power histology-like tissue structure information. The data may be viewed in any horizontal plane to observe high-resolution cellular morphology. Furthermore, the data allows the display of any structures of interest and their interrelationships with one another and with their surroundings in three dimensions. This unique method gives a comprehensive solution to address the source of contrast, resolution, field of view, imaging speed, and 3D spatial information. We demonstrated this method on normal, vitiligo, and cancerous human skin imaging in vivo.

Results

3D tomographic imaging with an extended field of view

This newly developed 3D tomographic imaging method is comprised of three co-registered microscopy imaging modalities to provide complimentary tissue contrasts: reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and two multiphoton microscopy (MPM) modes: two-photon fluorescence (TPF) and second harmonic generation (SHG) (Fig. 1a). The method is based on direct vertical plane tissue imaging. It is achieved by a resonance scanning mirror (8 kHz) fast scanning the femtosecond (fs) laser beam in the x-direction and simultaneously by a piezo positioner scanning the objective along the depth axis (z-direction). The piezo scanner is driven by amplitude- and phase-compensated sinusoidal voltages to reach a vertical imaging speed of 15 frames per second through bidirectional imaging, which effectively reduces the in-frame motion artifact (see details in the “Methods” section and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Extended FOV 3D tomographic imaging is realized by (stretching) moving the skin using a motorized translational stage (Fig. 2a) at a uniform speed in the y-direction with vertical section images being continuously acquired (Fig. 1b). The y-direction moving speed determines the frame sampling rate along this axis. Tissue features according to depth as well as the surface position are recorded in real-time in every frame. All motion that affects the recorded surface position can be conveniently calculated and corrected by comparing neighboring frames to render a volume with minimal motion artifacts (Fig. 1b and “Methods” section). Higher resolution post-processed en-face images can be achieved by increased y-direction sampling density. This xz plane vertical sectioning plus y-translation facilitated 3D volumetric imaging and can thus acquire a large tissue volume along the y-direction without the need for stitching.

a Schematic drawing of the volumetric multimodal microscopy optical imaging system based on vertical sectioning tissue imaging. A femtosecond (fs) laser beam after passing through a polarizing beamsplitter was scanned in the x-direction by a resonance scanning mirror and relayed to the back aperture of the objective. The focal point of the laser beam is scanned in the z-direction by moving the objective using a piezo positioner. Two-photon fluorescence (TPF) and second harmonic generation (SHG) signals are collected by the objective and reflected by the dichroic mirror and the beamsplitter to two photomultiplier tubes (PMTs). Reflectance confocal (RCM) signal is collected by the objective and reflected to the avalanche photodiode (APD) by the polarizing beamsplitter after passing through the dichroic mirror and the scanning mirrors. b The procedure for volumetric data acquisition and motion correction. Volumetric data was acquired by simultaneously scanning in the xz direction and (stretching) moving the skin with the translation stage in the y-direction. The acquired raw data is then reconstructed after skin surface detection, motion detection, motion correction, and frame averaging process (see details in the “Methods” section).

a shows how the skin site is interfaced with the imaging head. b and c show two types of interface configurations. b is used for direct measurement of the skin, which includes a window adapter, a metal window, and a plastic plate with a hole in the center. c is used for motion-suppressed measurement, which includes a window adapter, a metal window, and a coverslip. d–g Example of xz vertical sectioning images acquired in vivo on a dorsal forearm of a 46-year-old male volunteer at the excitation wavelength of 785 nm and the merged pseudocolor images of the three channels show various skin layers. SC: stratum corneum, SG: stratum granulosum, SS: stratum spinosum, SB: stratum basale (marked by arrows), DP: dermal papilla. The white rectangular in (d) outlines a multilayer sandwich-like skin structure near the skin surface, the dark layer is assumed to be stratum lucidum (SL). White arrows point to basale cells containing melanin. Color is coded in green for RCM, red for TPF, and magenta for SHG. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Direct vertical plane imaging

Figure 2a, b illustrate the 3D model of the imaging head of the system and the skin measurement interface. The skin site can be measured directly or with a glass coverslip (see details in the “Methods” section). Figure 2d–g demonstrates the vertical images acquired by the three modalities from the forearm normal skin of a volunteer in vivo, along with the merged composite pseudocolor image (red for TPF, green for RCM, magenta for SHG). Various layers of skin were easily visualized in the pseudocolor image (more details in the “Methods” section, Supplementary Note 1, and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The rectangular region in Fig. 2d outlines the sandwiched structure made of the three skin layers: The bright uppermost layer is the stratum corneum (SC). It has strong reflectance and TPF signals, appearing yellow in the pseudocolor RGB image. The second layer has low reflectance but high TPF signals, it is assumed to be the stratum lucidum (SL). The next bright layer (high RCM signal) is stratum granulasum (SG). The stratum basale (SB), as indicated by the arrows in Fig. 2d and e, is filled with bright spots arising from melanin-rich keratinocytes. Below the stratum basale layer, distinctive signals in the SHG channel show the distribution of collagen within the upper dermis. Dynamic capillary blood flow has previously been observed by RCM in the horizontal plane29, now we can also monitor it in the dermal papilla in the vertical plane (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, and Supplementary Movie 3). Clear visual demarcation of epidermis and dermis is important in cancer diagnosis since most such neoplasms arise near the epidermal-dermal junction; moreover, this boundary region defines invasiveness and thus the prognosis of cancers such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma.

Motion correction and surface flattening

Figure 3 shows the motion-affected raw volumetric data acquired from the dorsal forearm of a 29-year-old male volunteer with an excitation wavelength of 880 nm. A plastic plate with an open hole was used as the measurement interface for direct skin measurement. xz images are simultaneously recorded by the three modalities of RCM, TPF, and SHG with 4072 frames in each modality. The moving speed of the y-translation stage was set to 11.72 µm/s, which corresponded to 1280 frames/mm. Therefore, the imaged tissue dimension is 200 µm × 200 µm × 3.2 mm. After contrast enhancement of the TPF and SHG videos, the three videos were merged to generate a pseudocolor image by assigning the green color to RCM, the red color to TPF, and the magenta color to SHG. The merged video was then viewed three-dimensionally in ImageJ as shown in Fig. 3d. Motion artifacts are obviously visible in the 3D image reconstructed from the raw videos. The motion artifacts can be classified into two types: the system-caused motion which is labeled by the solid arrows and involuntary motion from the subject which is marked by the hollow arrows. The system-caused motion features as a sharp shift of the imaged skin surface. It is generated when the z stage is moved upward or downward manually during the imaging process to keep the skin surface in the top part of the field of view to have more tissue information imaged. The involuntary motion at the dorsal forearm is typically caused by breath, pulse beat, or muscle contraction and relaxation, which features small amplitude and periodicity. These two types of motions both dominate the motion artifacts in the z-direction.

Volumetric imaging through the y-stacking allows convenient correction of the above motion artifacts because each xz image records not only the tissue information but also the skin surface. Based on the fact that the skin surface is continuous, a motion-correction algorithm was developed. The motion during imaging is first detected and then the volume data is motion-corrected accordingly. The motion detection procedure with an example is shown in Fig. 4, which includes four steps.

a The image of the raw volume (RCM) with motion artifacts. b The method to calculate the relative motion between every two neighbor frames. b-1 and b-2 are two example neighbor raw frames: frame 2833 and frame 2834. b-3 The detected surface position curves of (b-1) and (b-2). b-4 The difference between the two curves in (b-3). b-5 The histogram of the counts of the difference value of (b-4). b-6 data points selected from (b-5) with the x-value (difference of the surface positions) of which fall within the range between −8 and 2. c The curve of the relative motion of every two neighbor frames. d The calculated motion curve, the tread of the motion curve, and the realigned motion curve. e The volume image after motion correction.

Step 1. The skin surface positions for each frame are determined. Each frame of the raw RCM video records depth information from the top dark region (in water) to the bright water-skin interface and then further into the skin tissue. Skin surfaces were detected from every xz-plane RCM frame based on intensity thresholding: along each column from top to bottom, for those first two consecutive pixels that have intensities higher than a threshold value of 50 (for an 8-bit grayscale image), the first pixel will be defined as the surface pixel and its row index is recorded. In this way, the skin surface (256 points) of every frame is determined and noted as Sn, which is an array of the row indexes of the surface pixels across all columns. The subscript n is the numeric index of the frame. Two adjacent frames are shown in Fig. 4b-1 and b-2 and their detected surface arrays are plotted in Fig. 4b-3.

Step 2, The difference array (Diffn) of the skin surfaces of two neighbor frames is calculated through subtraction: Diffn = Sn-Sn-1, as demonstrated in Fig. 4b-4.

Step 3, The outliers are eliminated. The frequency histogram of Diffn was plotted (Fig. 4b-5) showing the number of occurrences for each difference value. And the most frequently appearing value dmode within Diffn was determined. Outliers are eliminated using a selection window set from dmode − 5 to dmode + 5. Any element of Diffn with its value not sitting within the window is deleted and a new array Diff ‘n is generated. In Fig. 4b-5, we can see that values with the most counts lie between −8 and 2. The dmode is −3 which has a count of 49. Diff ‘n was plotted in Fig. 4b-6 with 22 data points being filtered out.

Step 4. The relative motion is determined using the average value of Diff ‘n. In Fig. 4b-6, the average value of all the data points is -2.19, which is treated as the relative motion between the two frames in Fig. 4b-1 and b-2. To retain the surface profile of the volume, the differences with average values smaller than 0.5 pixels were re-assigned as zero, thus assuming no motion.

The relative motion of every successive frame to its previous frame is determined according to the above four steps as shown in Fig. 4c. Next, a motion curve (the black line) is generated as shown in Fig. 4d which shows every frame’s total motion in relation to the first frame by adding up all the previous relative motions. Every frame is shifted up/down the corresponding number of lines in the motion curve to remove the motion effect. For practical reasons, one more step can also be added to complete the final correction process as illustrated in Fig. 4d: offsetting the motion curve by its linear regression fitting line (the blue curve). For each data point in the detected motion curve, its motion value is subtracted by the corresponding value in the linear regression fitting line. After the subtraction, a realigned motion curve is achieved (the red line), which has an overall flat trend. The motion-corrected results are shown in Fig. 4e. Compared to the raw volume image in Fig. 4a, a continuous skin surface is recovered without being over-smoothed.

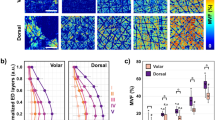

Figure 5a–f shows the volumetric imaging results after motion correction. A 3D rendering movie of the motion-corrected data is shown in Supplementary Movie 4. After motion correction, the minor and major motion-induced fluctuations were greatly reduced while the overall skin surface texture with the shapes of hair, surface scale, and other debris was kept. The advantage of motion correction is that the volumetric image can be viewed horizontally and vertically or in any arbitrary plane (Fig. 5b) without artifacts. In a vertical view, the epidermal-dermal junction is clearly outlined in a wide field; while in a horizontal view at a selected depth, epidermal cellular and/or tissue information can be shown with high, subcellular resolution. With a wavelength of 880 nm, TPF signals can be dominantly excited from sweat ducts, hair shafts, and stratum corneum. Figure 5c was the zoomed orthogonal view of a sweat duct in the epidermis (Supplementary Movie 5). For better visibility, only the TPF channel was selected to display. In the vertical planes (yz and xz plane), the sweat gland is shown as stacked parallel lines (pointed by hollow arrows) with a length of about 50 µm. In the horizontal plane, it looks like an oval-shaped disk. Figure 5d was the zoomed orthogonal view of a hair shaft in the epidermis (Supplementary Movie 6). The hair shaft has strong TPF signals (red color in the images). The xz image shows that the hair shaft has a diameter of 57 µm and it starts from the dermis and opens to the epidermis. Both the xz and xy images show the basal cells are arranged in a circle surrounding the hair shaft. Figure 5e is the zoomed orthogonal view of the selected part of the volume (right rectangle box in Fig. 5b). The epidermal cells were visible in the xy plane with the resolution of RCM. Some red spots were shown in the yz plane image as pointed out by the solid white arrows. They were melanophages or melanin granules which have TPF signals. Figure 5f shows one yz plane image with only the TPF and SHG channel signals, which shows the clear separation of the stratum corneum (in red color) and top dermis (in magenta color).

a 3D image of the motion-corrected volume. b Orthogonal view of the 3D image in the yz and xy plane. The dashed yellow lines indicate the sectioning position. The three dashed rectangular boxes from left to right correspond to the position of (c–e). c The zoomed-in orthogonal view of a sweat gland with only the TPF channel (left rectangular box in b). The arrows point to a spinal sweat duct. d The zoomed-in orthogonal view of a hair follicle (central rectangular box in b). e The zoomed-in orthogonal view of a subvolume (right rectangular box in b). f Vertical plane image of the volume with only TPF and SHG channels. g 3D image of the surface flattened volume. h Vertical plane image of the surface flattened volume. i–k Horizontal plane image of the surface flattened volume at different depths. Color is coded in green for RCM, red for TPF, and magenta for SHG. Color is coded in green for RCM, red for TPF, and magenta for SHG. Scale bar 100 µm.

We also noticed that different skin layers are sometimes sectioned into a single horizontal image as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 5b because of the roughness of the skin surface, making it inconvenient to compare cellular or tissue structures at the same “tissue depth”. Here the tissue depth refers to the depth below the skin surface rather than an arbitrary flat plane. With the volume data, we are able to solve this problem by a surface-flattening method (results are shown in Fig. 5g–k, method details in the “Methods” section, Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Figs. 8, 9, and Supplementary Movie 7). Figure 5g shows the 3D image of the surface flattened volume. Figure 5h shows the vertical plane image of the volume and Fig. 5i–k shows horizontal plane images of the surface flattened volume at different depths. Figure 5j has the same tissue depth (42.0 µm) as that of the orthogonal center of Fig. 5b. We can see that the tissue structures are similar at the same tissue depth in the normal skin of different sites.

High-resolution 3D tomographic in vivo imaging of normal skin

The fs laser wavelength can also be tuned to shorter wavelengths such as 735 nm to acquire volumetric microscopy images with better TPF cellular resolution (Fig. 6, Supplementary Movies 8, 9, Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). A 200 µm × 200 µm × 2.3 mm volume of normal forearm skin was acquired in vivo from a 29-year-old volunteer with both RCM and TPF channels. The SHG signal is not separated from the TPF channel because of the lack of a dichroic mirror at hand. The raw volume is made of 15,000 frames with each frame being 256 pixels by 256 pixels after 2 × 2 pixel binning of the acquired 512 × 512 pixels image. The laser power was 40 mw. The whole volume was acquired in 17 min with a slow translation speed (2.34 µm/s) for five-frame averaging. Figure 6 only shows the TPF channel results to emphasize the high cellular resolution. The trace of the motion during the data acquisition can be clearly observed from the motion-corrected yz plane image (Fig. 6a) as a curve that separates the bottom of the tissue data from the dark background. It is necessary to mention, that the skin was measured directly without using a cover glass for motion suppression, which further demonstrates the motion tolerance of our method.

The successfully reconstructed high-resolution cellular imaging is demonstrated in Fig.6c, where the nucleus and cytoplasm of individual cells are visualized with crispy clear contrast over an extended FOV of 200 µm × 2.3 mm. Characteristic depth-dependent variations of normal skin cellular and morphological features are clearly shown in Fig. 6b–f and described in detail in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11.

3D tomographic in vivo imaging of vitiligo

The system was used for in vivo volumetric imaging of a vitiligo lesion on the abdomen of a 40-year-old male volunteer under 880 nm fs laser excitation (Fig. 7, Supplementary Movie 10). A volume of 200 µm × 200 µm × 8 mm was imaged in 11.3 min covering the transition zone from the pigmented area (right side in Fig. 7) to the non-pigmented area (left side in Fig. 7). The volumetric image (Fig. 7a), horizontal plane image at the depth of 28 µm (Fig. 7b) and vertical plane image (Fig. 7c) sectioned in the middle of the volume are displayed. The pigmented area features a lot of pigmented cells at the top of the dermal-epidermal junction as shown in the zoomed view (Fig. 7f, g) of the green rectangular region in Fig. 7b, c, while the non-pigmented area has very few pigmented cells (Fig. 7d, e, orange rectangular region in Fig. 7b, c). The pigmented cells have both reflectance and TPF signals, therefore they are visualized as yellowish dots in the pseudocolor image (two example pigmented cells are pointed to by white arrows in Fig. 7f). This volumetric data was successfully acquired and reconstructed even with the apparent breath-caused periodical motion as pointed out by the black arrow in Fig. 7e. After motion correction, the trace of the motion is visualized directly as an undulation line contrasted between the background of the imaging data and the filled pure black space, which has a peak-to peak amplitude of 10 µm and a frequency of 16 cycles per minute. The motion pattern matches the respiratory rate of a healthy adult (12–20 breaths per minute)30,31. The successful reconstruction of the volumetric data demonstrates the motion tolerance of the system.

a An image of the 3D volumetric data cube of a dimension of 200 µm × 200 µm × 8 mm encompassing the transition zone from the pigmented area (right side) to the non-pigmented area (left side). b An xy plane image sectioned at the depth of 28 µm. c A yz plane image that is sectioned in the middle of the volume. d and (e) are zoomed views of a rectangular region selected (orange rectangle) in the non-pigmented area in (b) and (c). The yellow dashed line in (d) and (e) shows the corresponding section plane position of (e) and (d). f and (g) are zoomed views of a rectangular region selected (green rectangle) in the pigmented area in (b) and (c). The yellow dashed line in (f) and (g) shows the corresponding section plane position of (g) and (f). The red arrows in f point to two example pigmented cells. The black arrow in (e) points to the undulation traces of motion. Color is coded in green for RCM, red for TPF, and magenta for SHG. Scale bar: 100 µm.

3D tomographic in vivo imaging of melanoma in situ

Finally, the system has been used for in vivo volumetric imaging of a melanoma in situ lesion on the upper back under 880 nm fs laser excitation (Fig. 8 and Supplementary movie 11). A volume of 200 µm × 200 µm × 5 mm was imaged in 7 min, encompassing cancerous tissue (left side), lesion border (middle section), and normal tissue (right side). The volume was surface flattened and contrast-enhanced along the depth direction for better visualization of the tissue features (more details in the “Methods” section). An overview of the vertical plane and the xy plane shows the apparent decrease of upper dermis collagen signals in the cancerous region compared to the normal skin region (Fig. 8a). Three sub-volumes as marked in Fig. 8a were cropped for detailed examination of the cancerous, border, and normal tissue regions. The corresponding vertical views were displayed in Fig. 8b and five selected horizontal images at different depths (D1–D5) marked in Fig. 8b were displayed in Fig. 8c and d. In the cancerous region, the dermal collagen is barely visible, while the epidermis is filled with dendritic pagetoid cells (arrowheads). Around the epidermal-dermal junction, there are no clear rete ridges but the aggregate of atypical cells (arrows) arranged with nonspecific patterns. These features are similar to those described in previous RCM studies of cutaneous melanoma in situ12,32,33,34. The lesion border is rich in round-shaped, bright cells forming typical dermal papillae structures, which are the characteristics of benign nevi11,32,33. The normal tissue region in contrast features a thinner epidermis, abundant dermal collagen signals, and no apparent cellular atypia.

a The yz plane overview of the tissue volume with a dimension of 200 µm × 200 µm × 5 mm encompassing the lesion (left), its border (middle), and the adjacent normal tissue (right). b Zoomed-in yz plane images of the above three selected sub-volumes as marked by white boxes in (a) for detailed examination The three boxes from left to right correspond to cancerous, border, and adjacent normal tissue respectively. c, d Horizontal views of the three sub-volumes at five depths as marked in (b). Note that the exact depth of D1–D5 in the three sub-volumes is selected differently to show the most typical morphological features. The cancerous zone shows dendritic pagetoid cells (white arrowheads) and aggregated atypical cells (white arrows) with nonspecific patterns (the dashed circle). The border zone is filled with bright, round-shaped cells forming dermal papillae that contain collagen signals. The normal tissue has abundant collagen signals with clearly defined dermal papillae. Color is coded in green for RCM, red for TPF, and magenta for SHG. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Discussion

Reorientating the optical imaging perspective from horizontal to vertical plane imaging and extending the field of view by skin tissue translation are the key innovations underlying our xz-y large FOV volumetric imaging technique. In combination with a motion-correction method, we realized reliable up to 8 mm length extended FOV 3D volumetric image reconstruction. This results in subcellular resolution en-face section images from the volume and also a confirmation of perfect motion correction and registration of the vertical imaging sections and perfect 3D reconstruction.

Upon examining the reconstructed 3D volumetric image, we observed that the involuntary motion of the skin tissue during imaging acquisition can be analyzed retrospectively (Fig. 7e, g). The motion traces resemble an undulating line, with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 10 µm and a frequency of 16 cycles per minute. This motion pattern appears to correspond with the respiratory rate of a healthy adult, which ranges from 12 to 20 breaths per minute30,31. This finding further confirms the success of our xz-y volumetric imaging approach. The relationship between this motion and breathing, heart rate, and muscle contractions warrants further investigation. Our xz-y volumetric imaging method provides a quantitative approach to this endeavor.

The current 200 µm × 200 µm FOV of the vertical section (xz) imaging was mainly limited by the objective, this could be increased to 400 µm × 200 µm or 800 µm × 200 µm by using high NA low magnification objectives to double or quadruple the measurement volume without increasing the acquisition time. Multiple volume stripes can also be stitched together in the x-direction to cover an even larger surface area (an ex vivo example was demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 12). In addition, the xz frame rate could be further improved by scanning fewer lines considering the relatively low vertical resolution. In this paper, 512 lines are scanned within a depth of 200 µm. Scanning half the number of lines will double the frame rate while keeping a reasonable sampling density in the depth direction. In addition, current vertical scanning was achieved by moving the objective with a piezo positioner. The scanning speed is limited by the driving power and load capacity of the piezo positioner. For higher speed xz scanning, remote focusing may be an alternate choice35,36. It is necessary to mention that volumetric imaging can be acquired with a cover glass for motion suppression and physical surface flattening or without a cover glass for keeping the native status and surface roughness details of the skin. Measurement with a cover glass is recommended for many cases because the physically flattened surface also introduces less distortion for the focused laser light and gives better imaging results. However, there are instances where the use of a cover glass is impractical or undesirable, such as when imaging significantly elevated lesions or lesions with uneven surfaces. The pressure exerted by the cover glass on the skin can significantly alter tissue blood volume and blood flow dynamics in the dermal capillaries and it may also alter the tissue density and tissue morphology.

RCM channel in the multimodality imaging system is crucial. It provides the strongest signals across the entire wavelength tuning range of the fs laser and can offer detailed tissue structure and cellular information, especially when the corresponding TPF signal is weak. RCM channel images were also used as references for motion correction because it has low background noise and strong surface signals. In addition, this channel can be used to monitor blood flow which cannot be achieved by TPF and SHG channels. Different from that of the RCM channel, the signal intensity of the TPF and SHG channels is excitation wavelength-dependent4. Between 735 nm and 880 nm, the overall signal intensity in the TPF channel gradually decreases, particularly from cells, while the collagen SHG signal increases. Although it is not possible to make the images of the three channels all have the maximum resolution and contrast at a single excitation wavelength, balanced results still could be achieved depending on applications. We demonstrated the volumetric imaging results using 735 and 880 nm. The 880 nm wavelength was selected for fast-speed volumetric imaging with good epidermis and dermis contrast. This wavelength has deeper penetration and generates stronger dermis SHG signals from collagen fibers. The RCM channel provides the cellular information in the epidermis. Despite the low pixel dwell time and excitation efficiency, the weak TPF channel still provides valuable information, including stratum corneum, hair shaft, sweat gland ducts, and certain dermal components with strong TPF signals. The 735 nm wavelength was selected for high-resolution TPF imaging of cells, the translation speed was also slowed down by five times so that neighbor frames could be averaged to increase the SNR. In this case, the RCM channel image shows cell junctions in the epidermis and inhomogeneous tissue structures in the dermis, while the TPF channel highlights cell plasma, melanin distribution, and dermal elastin fibers. Although the SHG signal is not very strong, it can still be separated from the TPF signal using a dichroic mirror. Further testing of wavelengths between 730 nm and 880 nm is needed to identify an optimized wavelength that allows all three channels to produce images with good and balanced SNR, even if not the highest. To the best of our knowledge, our group is the first to propose and realize simultaneous, co-registered RCM, TPF, and SHG imaging, fully leveraging their complementary capabilities27.

The method can be referred to as optical shave biopsy, capturing detailed 3D tissue information within a depth of 200 µm over a large field up to 8 mm wide. Unlike current RCM imaging37, it eliminates the need to predefine the depth at which horizontal images are captured, making it promising for standardizing imaging methods to improve clinical adoption. The recorded volumetric data can be used not only for skin evaluation and disease diagnosis but also as a valuable reference for pinpointing the same micro-site in longitudinal monitoring studies. Moreover, it can serve as a superior training and teaching resource compared to large field-of-view xy images at only a few selected depths.

With advancements in compact designs for MPM and RCM imaging systems27,38, the optical shave biopsy method demonstrated in this paper could be integrated into these systems, resulting in a more compact and convenient device for routine clinical applications. The handheld probe as currently developed by Enspectra Health Inc. can acquire vertical plane MPM and RCM images directly but still faces challenges such as low speed and low resolution. If their imaging speed could be further improved and the skin surface could be well controlled to stay in the field of view, xz-y volumetric imaging capability could be implemented to provide much richer information.

In conclusion, we have developed a 3D volumetric multimodal microscopy imaging method based on vertical plane scanning that provides a fast and convenient way to acquire motion-corrected and reliably reconstructed 3D in vivo skin tissue images with multi-contrast and subcellular resolution over a close to centimeter (8 mm) wide extended field of view. Using the developed method, we have successfully realized the noninvasive acquisition of histology-like diagnostic features from normal skin, vitiligo, and melanoma three-dimensionally, thereby demonstrating the great potential of this unique 3D imaging method for in vivo skin biology study, clinical diagnosis, pre-treatment planning, and post-treatment monitoring among others.

Methods

System setup

The volumetric multimodal microscopy imaging system consists of three co-registered laser scanning microscopy imaging modalities: reflectance confocal, two-photon fluorescence, and second harmonic generation (Fig. 1a). Using a single laser this system can simultaneously acquire images from these three channels within the same cross-section to yield multi-contrast morphologic tissue details. RCM is based on elastic light scattering arising from refractive index variation across different tissue components; TPF relies on endogenous tissue fluorophores including keratin, elastin, NADH, FAD, and melanin, while SHG is a distinctive nonlinear optical mode that is solely due to second harmonic signals from cutaneous collagen. As shown in Fig. 1a, an 80 MHz Ti: sapphire femtosecond laser (Chameleon, Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, California) with wavelength tunable between 720 and 950 nm is used as the light source for imaging. Then the pulse width of the beam is pre-compensated using a prism pair, after which the beam is expanded and collimated before reaching a scanning unit with an 8 kHz resonance scanning mirror and a Galvo scanner mirror. A polarization beamsplitter in between the collimation and the scanning unit together with a quarter waveplate is used for reflectance confocal signal detection. The laser beam is then relayed to the rear aperture of a 60× (NA = 1.0) water-immersion objective (LUMPLFLN60X/W, Olympus Canada, Markham, Ontario) and focused onto the skin. This objective is attached to a piezoelectric positioner (MIPOS 500, Piezosystem Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) for z-direction scanning. For RCM the reflectance signal is descanned by the scanning mirrors, redirected by PBS, and focused to an avalanche photodiode (APD) module (C10508, Hamamatsu Corp., Bridgewater, NJ) with a 20 µm pinhole thereby forming the RCM image. The MPM signals collected by the objective are reflected by a dichroic mirror (FF665-Di02-25×36, Semrock, Inc.) and focused by a lens. They are then short-pass filtered (FF01-680/SP-25, Semrock) and split by another dichroic mirror (Di01-405-25×36 for 785 nm excitation, FF458-Di02-25×36 for 880 nm excitation, and empty for 735 nm excitation, Semrock, Inc.) into two photomultiplier tubes (PMT, H9433MOD-03, Hamamatsu Corp., Bridgewater, New Jersey) for detection of TPF and SHG images respectively. For SHG detection there is a bandpass filter (FF01-390/40-25 for 785 nm excitation, FF01-440/40-25 for 880 nm excitation, Semrock, Inc.) in front of the PMT, whereas for TPF detection a short-pass filter (FF01-650/SP-25, Semrock, Inc.) is used instead. The RCM signals detected by APD and the TPF and SHG signals detected by PMTs are simultaneously collected by a frame grabber (Helios XA, Matrox Electronic Systems Ltd., Canada) to generate RCM, TPF, and SHG images. Because all three imaging channels use the same laser source and scanning unit, the three images are co-registered. The scanning unit, the relay lenses, the piezo positioner, the objective, and the two PMT detectors are assembled together as the imaging unit, forming a key portion of the imaging head. An articulated mirror arm connects the optical path between an optical table and the imaging head, facilitating skin imaging of different body sites.

For volumetric imaging, motorized translation stages are integrated into the system including a z-translation stage (X-LSQ075A, Zaber Technologies) and motorized x- and y-translation stages (LNR25ZFS, Thorlabs). The imaging unit (Fig. 2a) is fixed on the carriage of the z stage so that the z stage can be used for real-time position adjustment of the focal plane. The xy translation stages are fixed on the base of the z stage. A customized adapter with a clear central through-hole was installed on the x stage as a skin measurement interface. On the top surface of the adapter, four holes are drilled to fit in magnets, and on the bottom of the adapter, a sinkhole was milled to accommodate a customized metal window which also has a central opening. It is this metal window that is affixed onto the skin using double-sided adhesive tape; the metal window is magnetically attached to the adapter. The xy translation stages can move the skin bidirectionally; during volumetric imaging, the skin is moved only by the y stage.

The imaging unit together with the stages form the imaging head (Fig.2a) which in turn is supported by an articulated arm. The entire system is controlled by customized software written in C++ to control scanning, stage motion, data acquisition, and data saving. Post-image processing, motion correction, and volume reconstruction were completed by customized software written in C++.

Vertical plane scanning

Vertical-plane xz scanning is realized with an 8 kHz resonance mirror for fast x-axis scanning and a piezo positioner for slow z-axis scanning. A DC voltage signal was used to drive the resonance scanner to scan along the x-direction. The amplitude of this voltage controls the scanning range. The piezo positioner is controlled by a controller unit (NV 40/1CLE, Piezosystem Jena GmbH, Jena) which has a bandwidth of around 10 Hz (capacitance of 21 µF). A voltage waveform was generated by a data acquisition (DAQ) card (NI USB-6343, Nation Instruments, Inc.) and sent to the controller to drive the piezo positioner for scanning the focused laser spot in the z-direction. Every time one line is scanned, the resonance scanner will output a horizontal synchronization signal (Hsync). Hsync signals the movement of the piezo positioner by one step in the z-direction (slow axis). To generate an image with 512 × 512 pixels, at least 512 steps need to be executed in the z-direction. However, due to the limited bandwidth of the controller and the mechanical inertia of the piezo positioner, the piezo positioner cannot directly follow the driving signal. If the piezo positioner is driven by a sawtooth signal, the resulting movement trajectory will not be a linear pattern, which makes it hard to do image correction. When it is driven by a sinusoidal signal, the actual moving trajectory will retain a sine pattern, but with a phase shift and amplitude attenuation that can be pre-compensated easily. To achieve high-speed bidirectional imaging, we employed a sinusoidal drive signal.

Amplitude attenuation means the piezo positioner will not reach the designated maximum position set by the driving voltage, causing a difference between the actual versus desired scanning ranges; the actual scanning range is calibrated by monitoring the feedback position curve of the piezo positioner with an oscilloscope. To correct phase shift, phase pre-compensation is required to match the starting point of z scanning to the vertical synchronization signal. This is done by incorporating a phase shift into the driving voltage.

Supplementary Fig. 1 is an illustration showing the compensation process. Supplementary Fig. 1a shows the time shift Δt and the amplitude attenuation ΔA between the drive signal and the feedback signal. Strictly speaking, the time shift Δt is the phase shift between the feedback signal and the vertical synchronization signal (Vsync) which marks the start of a new frame. The Vsync signal is generated by the DAQ card after counting a certain number of Hsync pulses. The number of Hsync pulses is equal to the number of lines that are scanned in a half-scanning cycle for bidirectional imaging.

The function of the drive signal is:

Here n refers to the ordinal of the line that is going to be scanned and N is the total number of lines that will be scanned in a full scanning cycle. The period between adjacent lines equals the time that the 8 kHz resonance scanner takes to scan one single line (TR), which is 1/8000 s. A is the voltage amplitude.

For compensation, the original drive signal function was modified by adding a phase shift component \(\Delta n\) (\(\Delta n=\frac{\Delta t}{{T}_{R}}\)). At the same time, voltage amplitude A was replaced with a calibrated one, A′ which compensates for the attenuation.

Therefore, the new function is:

After compensation, the actual motion of the piezo positioner matched the Vsync signal well and the amplitude of the feedback signal had the desired amplitude A as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b.

Bidirectional imaging

To increase the imaging speed, we implemented bidirectional imaging by fully utilizing the sinusoidal scanning pattern. One image is generated during the downward scanning and a second image is generated during the upward scanning. The key to achieving this function is via video timing configuration of the frame grabber (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Step 1. Set the synchronization signals to enable bidirectional imaging or upgrade from unidirectional imaging. For unidirectional imaging, one Vsync is generated after the piezo completes a full cycle, whereas for bidirectional imaging, there has to be one Vsync signal for each half cycle.

Step 2. Configure the video timing. The image acquisition device is a frame grabber. The digitizer configuration files (DCF) are used to define video timing. The same settings also apply to other image acquisition devices, for example, a data acquisition card. Four parameters are to be set for vertical scanning: number of lines per frame (N0), vertical synchronization time (VS), front porch (FP), and back porch (BP). The parameter VS sets the time period for vertical synchronization, while the FP and BP set time periods before and after VS when imaging is blanked. The relationship among the four parameters is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The actual imaging area falls between BP and the next FP. For bidirectional imaging, it is necessary to keep the imaging region of both the upward scanning and the downward scanning the same. Otherwise, the vertical scanning range of the two acquired images will be different. The DCF file is therefore set to make FP equal in time to the sum of VS and BP. To make better use of the scanning area, FP can be made as short as possible and BP can be set to zero such that FP can have the same time period as VS. The total number of lines scanned in the vertical direction in a cycle is N = 2(N0 + VS + FP). For our imaging system, N0 is set to 512, VS = 5, and FP = 5, therefore the total N is 1044.

The bidirectional imaging proposed here is not limited to the linear region and information from both upward and downward scanning is acquired. Therefore, almost the entire scanning cycle is used. More importantly, the frame rate is doubled by bidirectional imaging, which benefits the in vivo vertical section imaging.

Image distortion correction

Images or videos acquired through bidirectional vertical section scanning will double the frame rate of image acquisition but also introduce image distortions. For the x-direction, sinusoidal correction algorithms were used to redistribute the pixels according to their index in the acquired original images39. In contrast, signals in the z-direction were affected by both nonlinear scanning and piezo positioner hysteresis. We corrected every pixel position according to its feedback position data and considered three kinds of distortions. The first distortion is the inverted image acquired during upward scanning. The second distortion is image stretching in the top and bottom parts arising from the sinusoidal scanning. The last and most challenging one is caused by the hysteresis of the piezo positioner. Hysteresis prevents the actual trajectory of the piezo positioner from following an ideal sine wave in the fast scanning mode, leading to mismatches between the downward and upward scanning trajectories. The phenomenon of hysteresis during vertical scanning is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The actual scanning trajectory is rebuilt according to the position feedback signals acquired during scanning. Supplementary Fig. 3a shows all position data (1044 points) of one scanning cycle of the piezo positioner. In Supplementary Fig. 3b, the position data of the upward scanning (blue line) is horizontally flipped to compare with that of the downward scanning (red line). The effect of hysteresis is marked by a black arrow pair. This nonlinear distortion cannot be easily corrected by a standard sinusoidal algorithm as is used for resonance scanning in the x-direction. To correct all sources of distortion as described above we use the feedback position data to redistribute each pixel from the raw image to a distortion-free image via pixel mapping. The correction procedure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b, c. We used the downward image as an example to show the procedure.

First, based on the first and last position data (Pbottom and Ptop) as well as the number of lines (N) scanned in each cycle, an ideal sinusoidal wave is generated using the following function:

Then a projection line L is generated which is tangential to the ideal sine wave at the middle point N/2. The slope of line L is \(K=\frac{2{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{A}_{0}}{{{{\rm{N}}}}}\), and the line function is \({{{\rm{L}}}}(n)={Kn}+{B}_{0}-\pi {A}_{0}\). The downward scanning position curve is named as DScan(n) and the flipped upward scanning position curve as UScan(n). According to video timing, position data that corresponds to the acquired image can be determined: with our configuration, it is the 5th to 516th data point (index starts from 0). We name the corresponding start and end indices nstart and nend. These 512 position data points are matched to the 512-pixel lines in the acquired raw image one by one. The z position where each pixel line in the raw image is acquired can be expressed as Ppixel_index = DScan(pixel_index + nstart). The pixel_index also starts from 0. The next step is to determine the number of pixel lines for the corrected image as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b. Both DScan(nstart) and DScan(nend) are projected to the horizontal axis through projection line L to get the new start and end indices (n′start and n′end) for the corrected image. The number of pixel lines for the corrected images is therefore n′end − n′start + 1. The z position of each pixel line (with an index of pixel_index’) in the corrected image can be calculated as Ppixel_index′ = L(pixel_index′ + n′start).

For each Ppixel_index′ or L(n′ = pixel_index’ + n′start), the value is compared to all the position data inside on the DScan curve to find the nearest one (i.e. ndown) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3c. A match relation between all n′ and ndown is then built and expressed as an array: M(n′) = ndown (n′ starts from n′start to n′end), so L(n′) = DScan(M(n’)) = DScan(ndown).

Finally, each pixel line of the corrected image will be filled by a corresponding pixel line in the raw image using the actual position as an intermediate parameter:

Therefore, a pixel line with the index of pixel_index′ in the corrected image will be replaced by a pixel line with the index of M(pixel_index′ + n′start) − nstart in the raw image.

Similar to the standard sinusoidal algorithm, the above correction method will also lead to decreased pixel number in the vertical direction, especially in the top and bottom regions. The vertical line number of the corrected image, in this case, decreased to 337 from the original number of 512. The new image was expanded to 512 lines through linear interpolation. Finally, the image was binned by a factor of 2 along both the x and z directions to increase the signal-to-noise ratio.

The same correction method was performed for the upward scanning image. Since each pixel in the corrected image was placed according to its actual position, all three kinds of distortions were corrected at the same time. In addition, it was found that the motion of the piezo positioner had good reproducibility. Therefore, it is unnecessary to acquire position data for every scanning cycle. Instead, the position data was only acquired at the tenth cycle when the motion already become stable. Every time a new imaging operation starts, the position data acquisition procedure is started first and then these data are used for distortion correction during real-time imaging.

In vivo skin measurements

Before each measurement, the skin site was cleaned with distilled water. The skin site can be measured directly or with a glass coverslip (Fig. 2b, c). For direct skin measurement, a plastic plate with a circular opening at the center (5 mm size) was used to attach the metal window to the skin. Double-sided adhesive tapes were attached along the edge of both sides of the plastic plate. One side of the plastic plate is attached to the metal window and the other side to the skin by positioning the location of interest to the center of the opening. The metal window served to couple the skin site to the translation stage. Water is added between the microscope objective and the skin surface for refractive index matching. The skin tissue volumes shown in Fig. 1 were acquired in this way.

The skin can also be measured with a glass coverslip, thereby further suppressing motion and flattening the skin surface for improved imaging quality. In this situation, the coverslip was attached to the metal window first with ring-shaped double-sided tape. Then a drop of water was added on the skin site to be measured followed by attaching the metal window to the skin with another piece of ring-shaped double-sided tape. Care was taken to avoid introducing bubbles between the coverslip and the skin. Here again, the metal window is served to couple the skin site to the translation stage. Finally, water is added between the microscope objective and the coverslip for refractive index matching. The vitiligo (Fig. 7) and melanoma in situ lesion (Fig. 8) were measured in this way.

Digital image processing

Before the images from the three channels were merged to build a pseudocolor composite. The SHG and TPF images were digitally processed using ImageJ (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). First, a median filter with a radius of 1 pixel is applied to the target image for noise reduction. Then we used the window/level function to increase the contrast and brightness. RCM images are generally not digitally processed when generating pseudocolor composites, but when necessary, it was processed for better visualization through intensity compensation (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Fig. 6 and 7).

Volumetric imaging

The procedure for volumetric imaging is shown in Fig. 1b. The skin is moved by the translation stage in the y-direction (up to 12 mm) while the xz section images are continuously acquired rapidly at 15 frames per second. The frame rate divided by the translation speed of the y stage determines the sampling rate of the volumetric imaging. For example, if the translation speed is 15 µm/s, the sampling rate will be 1 frame/µm or 1000 frames/mm. This value should match the sampling rate or pixel resolution in the x and z directions. The raw vertical imaging has a dimension of 200 × 200 µm with a pixel resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. In order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and decrease the image size, 2 by 2 pixel binning is further applied to reach a pixel resolution of 256 × 256 pixels for every vertical section image. To match this pixel resolution, we should acquire 1280 frames per millimeter in the y-direction, which corresponds to a translation speed of 11.72 µm/s. If high SNR is required, similar to pixel binning for the vertical section image, the y-translation speed can be set lower as desired to acquire more images per µm for frame averaging. For example, for five-frame averaging, the y-translation speed can be set at 2.34 µm/s. In this case, 6400 (1280 × 5) frames will be acquired for one millimeter. When the volume is reconstructed, five-frame averaging is performed to match the pixel resolution of the x and y directions. The motion-correction step is performed after acquiring all the volumetric data, with an average processing time of 1.7 s per 1000 frames.

Surface flattening

The surface-flattening method adjusts the overall skin surface of the imaged volume so that it is aligned along a single plane. Although one straightforward idea is to directly align the detected skin surface to a single plane, it will introduce new artifacts. This is because the skin surface detected using the thresholding method does not correspond to the exact skin surface automatically especially when there is debris on the top. However, the overall profile of the skin surface can be determined by low-pass filtering the detected and motion-corrected skin surface. Based on the smoothed skin surface profile, every surface point of the skin volume can be flattened continuously. It allows the shaping of the skin surface without introducing large local variations. It also keeps the micro-roughness of the skin. The details are shown below.

Step 1. Obtain the skin surface profile of the motion-corrected volume. The surface of every xz frame of the raw volume is a one-dimensional (1D) array Sn, therefore, the detected skin surface of the whole raw volume is a two-dimensional (2D) array which is expressed as S_volume. According to the motion curve determined in the motion-correction section, every Sn is subtracted by the corresponding value in the motion curve to generate Sn_new. All Sn_new forms a new 2D array called S_volume_new, which represents the motion-corrected skin surface of the whole volume.

Step 2. The low spatial frequency profile of S_volume_new was generated and designated as S_volume_new_filtered. The low spatial frequency profile shows the overall curvature of the skin surface while avoiding the high dependence on the thresholding detection method. The 2D low-pass surface filtering method is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. The 2D array of the motion-corrected surface was displayed as an image as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a. To avoid the edge effect, the 2D array was symmetrically padded around the four edges with an extension length of 200 pixels. The original 2D data has a dimension of 256 pixels by 4071 pixels and the extended dataset now has a dimension of 656 pixels by 4471 pixels. The dashed rectangular outlines the dimension of the original data. The Fourier domain of 2D padded data is calculated and displayed as an image in the Fourier domain, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8b. According to the principle of discrete Fourier transform (DFT), the frequency domain image has the same dimensions as the raw image. However, the interval at which the DFT is sampled is the reciprocal of the dimension of the input. Therefore, the same 2π spatial frequency has different samples in the x and y-direction.

Then a first-order 2D Butterworth filter was generated with the function:

Where x and y correspond to the coordinates of points in the image in the Fourier domain, x0 and y0 are the coordinates of the center of the image, and dx and dy correspond to the cutoff spatial frequency in the x and y-direction. The filter can be displayed as the filter image in Supplementary Fig. 8c. The cutoff frequency was set at 2π/25, which means the two ratios- dx to the dimension in the x-direction and dy to the dimension in the y-direction were set at 1/25. Filtered Fourier domain data (Supplementary Fig. 8d) can be generated by multiplying the filter with the Fourier domain data. Next, though inverse discrete Fourier transform, we can then get the low-pass filtered 2D padded surface data. The filtered 2D surface data without padding can finally be cropped out and designated as S_volume_new_filtered.

Step 3. The position of a flat surface is set as the xy plane passing the maximum value of the overall profile of the first frame. And the difference between S_volume_new_filtered and the flat surface is calculated as S_deltatoflat.

Step 4. The total correction array Acorrection is calculated by adding the corresponding values of the motion curve array to the S_deltatoflat. Finally, every column of the raw volume data is shifted up/down according to the corresponding value of Acorrection.

Volume contrast enhancement

A method based on gamma correction and linear histogram stretching was used for volume contrast enhancement. Gamma correction is a nonlinear histogram stretching operation:

Iin and Iout are normalized pixel intensities (in the range of 0–1) before and after gamma correction. When γ is smaller than 1, gamma correction will make the dark part of the image brighter, while the already bright part changes less. Liner histogram stretching stretches the range of the intensity values of an image into a larger range to improve the contrast. First, the method applied gamma correction for each horizontal plane image in the surface flattened volume. The gamma value was set depending on the brightness of the image and it has a range of 0.4–1. The brightness is evaluated as the ratio between the average pixel intensity (Ave_pixel) of all nonzero pixels in the image to the maximum intensity (i.e. 255 for an 8-bit image):

After gamma correction, each image is further contrast-enhanced by stretching its histogram from (minimum nonzero, maximum) to (0.1, 1), (0,1), and (0,1) for RCM, TPF, and SHG channels respectively. Nonzero pixels are emphasized because the motion correction and surface-flattening methods fill the volume with many zero values and the actual background of the acquired images is not zero. If these filled zeros are treated as the minimum pixel value of the image, the contrast enhancement methods will over-correct the images that have many zero-value pixels, making these images too bright.

Statistics and reproducibility

We have successfully acquired over 60 datasets using the xz-y volumetric imaging method from 12 volunteers. This includes 6 volunteers for normal skin measurement and 6 for diseased skin, including 1 melanoma. In some instances, we were unable to reconstruct the volumetric data. The method fails when motion is too severe, causing the skin surface to frequently move outside of the vertical plane’s field of view. Additionally, the reconstruction of high-quality data may be compromised if the skin window is not properly secured with the stage adapter, leading to lateral movement.

Inclusion & ethics

The study and informed consent process for human subject measurements were approved by the University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board (Certificate #: H96-70499). Consent forms were acquired from all study subjects. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Custom code and software for motion correction and volume reconstruction are available from the Zenodo Repository - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14648379 (ref. 40).

References

Rajadhyaksha, M., Grossman, M., Esterowitz, D., Webb, R. H. & Anderson, R. R. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin: melanin provides strong contrast. J. Invest. Dermatol. 104, 946–952 (1995).

Longo, C., Casari, A., Beretti, F., Cesinaro, A. M. & Pellacani, G. Skin aging: in vivo microscopic assessment of epidermal and dermal changes by means of confocal microscopy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 68, e73–e82 (2013).

Konig, K. & Riemann, I. High-resolution multiphoton tomography of human skin with subcellular spatial resolution and picosecond time resolution. J. Biomed. Opt. 8, 432–439 (2003).

Breunig, H. G., Studier, H. & König, K. Multiphoton excitation characteristics of cellular fluorophores of human skin in vivo. Opt. Express 18, 7857–7871 (2010).

Pouli, D. et al. Imaging mitochondrial dynamics in human skin reveals depth-dependent hypoxia and malignant potential for diagnosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 367ra169–367ra169 (2016).

Pena, A. M. et al. In vivo multiphoton multiparametric 3D quantification of human skin aging on forearm and face. Sci. Rep. 12, 14863 (2022).

Deegan, A. J. et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of normal skin and inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Laser Surg. Med. 50, 183–193 (2018).

Olsen, J., Holmes, J. & Jemec, G. B. Advances in optical coherence tomography in dermatology—a review. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 040901 (2018).

Huck, V. et al. From morphology to biochemical state–intravital multiphoton fluorescence lifetime imaging of inflamed human skin. Sci. Rep. 6, 22789 (2016).

Balu, M. et al. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 151, 1068–1074 (2015).

Balu, M. et al. Distinguishing between benign and malignant melanocytic nevi by in vivo multiphoton microscopy. Cancer Res. 74, 2688–2697 (2014).

Guitera, P. et al. In vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma using a two-step method: analysis of 710 consecutive clinically equivocal cases. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 2386–2394 (2012).

Pellacani, G., Pepe, P., Casari, A. & Longo, C. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J. Dermatol. 171, 1044–1051 (2014).

Bozkurt, A. et al. Skin strata delineation in reflectance confocal microscopy images using recurrent convolutional networks with attention. Sci. Rep. 11, 12576 (2021).

Vicente, J. R., Durkin, A., Shrestha, K. & Balu, M. In vivo imaging with a fast large-area multiphoton exoscope (FLAME) captures the melanin distribution heterogeneity in human skin. Sci. Rep. 12, 8106 (2022).

Ogien, J., Daures, A., Cazalas, M., Perrot, J.-L. & Dubois, A. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for three-dimensional skin imaging. Front. Optoelectron.13, 381–392 (2020).

Balu, M., Mikami, H., Hou, J., Potma, E. O. & Tromberg, B. J. Rapid mesoscale multiphoton microscopy of human skin. Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 4375–4387 (2016).

Lee, A. et al. In vivo video rate multiphoton microscopy imaging of human skin. Opt. Lett. 36, 2865–2867 (2011).

Dubois, A. et al. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for high-resolution noninvasive imaging of skin tumors. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 106007 (2018).

Kose, K. et al. Automated video-mosaicking approach for confocal microscopic imaging in vivo: an approach to address challenges in imaging living tissue and extend field of view. Sci. Rep. 7, 10759 (2017).

Abeytunge, S. et al. Confocal microscopy with strip mosaicing for rapid imaging over large areas of excised tissue. J. Biomed. Opt. 18, 61227 (2013).

Balu, M. et al. In vivo multiphoton NADH fluorescence reveals depth-dependent keratinocyte metabolism in human skin. Biophys. J. 104, 258–267 (2013).

Fast, A. et al. Fast, large area multiphoton exoscope (FLAME) for macroscopic imaging with microscopic resolution of human skin. Sci. Rep. 10, 18093 (2020).

Mansoor, H. et al. Vertical optical sectioning using a magnetically driven confocal microscanner aimed for in vivo clinical imaging. Opt. Express 19, 25161–25172 (2011).

Thomas, G. et al. In vivo nonlinear spectral imaging as a tool to monitor early spectroscopic and metabolic changes in a murine cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma model. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 4281 (2014).

Czekalla, C. et al. Technical parameters of vertical in vivo multiphoton microscopy: a critical evaluation of the flyscanning method. Laser Phys. Lett. 12, 085602 (2015).

Montgomery, K. L., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J. M. & Sanchez, G. N. Handheld multiphoton and pinhole-free reflectance confocal microscopy enables noninvasive, real-time cross-sectional imaging in skin. Sci. Rep. 14, 26129 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Perfectly registered multiphoton and reflectance confocal video rate imaging of in vivo human skin. J. Biophoton.6, 305–309 (2013).

Saknite, I. et al. Association of Leukocyte Adhesion And Rolling In Skin With Patient Outcomes After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Using Noninvasive Reflectance Confocal Videomicroscopy. JAMA Dermatol. 158, 661–669 (2022).

Massaroni, C. et al. Contact-based methods for measuring respiratory rate. Sensors 19, 908 (2019).

Liu, H., Allen, J., Zheng, D. & Chen, F. Recent development of respiratory rate measurement technologies. Physiol. Meas. 40, 07TR01 (2019).

Gerger, A. et al. Diagnostic applicability of in vivo confocal laser scanning microscopy in melanocytic skin tumors. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124, 493–498 (2005).

Pellacani, G. et al. The impact of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnostic accuracy of melanoma and equivocal melanocytic lesions. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 2759–2765 (2007).

Borsari, S., et al. In vivo dermoscopic and confocal microscopy multistep algorithm to detect in situ melanomas. Br. J. Dermatol. 179, 163–172 (2018).

Botcherby, E. J., Juškaitis, R., Booth, M. J. & Wilson, T. An optical technique for remote focusing in microscopy. Opt. Commun. 281, 880–887 (2008).

Botcherby, E. J. et al. Aberration-free three-dimensional multiphoton imaging of neuronal activity at kHz rates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2919–2924 (2012).

Rajadhyaksha, M., Marghoob, A., Rossi, A., Halpern, A. C. & Nehal, K. S. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Laser Surg. Med. 49, 7–19 (2017).

Zong, W. et al. Fast high-resolution miniature two-photon microscopy for brain imaging in freely behaving mice. Nat. Methods 14, 713–719 (2017).

Sanderson, M. J. Acquisition of multiple real-time images for laser scanning microscopy. Microsc. Anal. 18, 17–23 (2004).

Wu, Z. & Zeng, H. Motion correction and volume reconstruction software for: motion-tolerant 3D volumetric multimodality microscopy imaging of human skin with subcellular resolution and extended field-of-view. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14648379 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #: MOP130548 and Grant #PJT-166023), the Canadian Dermatology Foundation, the VGH & UBC Hospital Foundation, the BC Hydro Employees Community Services Fund, and Mitacs through the Mitacs Accelerate Program. Z.W. and Y.T. acknowledge CIHR Skin Research Training Centre for doctoral scholarship funding. We greatly appreciate the fruitful discussions with Dr. David I. McLean during the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

For this publication, H.Z. conceived the project. Z.W. and H.Z. designed the study. Z.W., Y. T., and Y.H. designed and built the multimodality imaging system. Z.W. implemented the xz-y volumetric imaging method and programmed the corresponding imaging acquisition, motion correction, and volume reconstruction software. Z.W. and Y.T. acquired the volumetric data from volunteers and analyzed the results. J.Z., H.L., and H.Z. helped with the ethics application. H.L. and S.K. recruited the study subjects. H.Z. and H.L. acquired the funding. H.Z. and H.L. supervised the project. Z. W. prepared the initial manuscript draft. All authors contributed to the interpretation and validation of the imaging results and the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests