Abstract

Advanced high-throughput chromosome conformation capture techniques, like Hi-C, reveal genome organization into structural units like topologically associating domains (TADs), which are crucial in gene expression regulation. While accurately identifying TADs is vital, distinguishing different types of TAD boundaries and TAD categories remains a significant challenge in genomic research. We develop a Markov clustering-based tool, Mactop, to accurately identify TADs and provide biologically important classifications of TADs and their boundaries. Mactop distinguishes stable and dynamic boundaries based on biological significance. Mactop shows superior performance against multiple TAD-calling methods. More importantly, leveraging spatial interactions among TADs, Mactop uncovers TAD communities characterized by chromatin accessibility and enriched histone modifications. Mactop unveils the ‘chromunity’ within TADs in high-order interaction data, showing that interactions within TADs are diverse rather than uniform. In short, Mactop is a versatile, accurate, robust tool for deciphering chromatin domain, domain community, and chromunity for 3D genome maps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Decoding the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the genome is crucial for deciphering the fundamental principles that govern its functionality1,2,3,4. Advanced chromosome conformation capture techniques, including high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C)5,6, SPRITE7, and Pore-C8, offer an extensive perspective on 3D genomic architecture by quantifying the interactions across chromosomal regions on a global scale. The acquisition of high-throughput chromatin data across a variety of biological contexts and processes has enhanced the understanding of the mechanisms governing DNA packaging within the nucleus, elucidated the dynamic nature of 3D conformational changes throughout developmental progression9, and illuminated the distinctions in cellular architecture between healthy and pathological states2,10.

Investigations into these datasets have revealed a preferential pattern of interaction among chromosomal regions, leading to the emergence of high-order structural formations, such as chromosomal territories5,11, A/B compartments5,12, topologically associating domains (TADs)13,14, and chromatin loops12,15, distinguished by the magnitude of their structural units and the unique molecular characteristics of their composing regions. While the association between the formation of TADs and gene expression alterations remains contentious16,17,18, early studies suggest these units are evolutionarily conserved19 and play roles in both development20 and disease mechanisms21,22. Hence, precise delineation of TADs is essential to connect 3D genomic structure with cellular functionality.

Various methods have been developed to identify TADs in recent years. For instance, one-dimensional linear metrics calculating statistical characteristics between chromatin fragments (bins) on the Hi-C contact map have been adopted to depict the TAD boundaries13,14,23. Clustering methods categorize chromatin fragments (bins) into clusters and designate the bins within the same cluster as a TAD24,25,26. Statistical model-based algorithms utilize probabilistic models with specific assumptions to identify TADs27,28,29. Hi-C maps can be modeled as graphs, and community detection or graph segmentation can be used to identify TADs30,31,32. However, these methods revealed significant inconsistencies in TAD identification33,34,35,36 and notable sensitivity to diverse factors, such as the resolution (i.e., size of the genomic region), sequencing depth, and the sparsity of the input data. Dang et al.37 emphasized that TADs and boundaries could be analyzed and classified according to their distinct characteristics with an ensemble strategy. Critically, current individual methods cannot classify TADs and boundaries based on spatially interacting characteristics, hindering the detailed investigation of their biological functions.

To address this, we developed Mactop, a Markov clustering-based tool designed to identify topologically associating domains in high-throughput chromatin maps. Mactop can categorize TADs and boundaries with different types, providing further insights into their distinct biological functions. Mactop demonstrated superior performance to three competing methods, including the Directionality Index13, Insulation Score14, and Topdom23 in analyzing TAD patterns using silhouette coefficient38, computing stability across different resolutions and sampling depths of Hi-C data, and the enrichment of protein and histone modifications. Moreover, Mactop constructs an interaction map of TADs and demonstrates that TADs form communities with greater spatial proximity and are enriched with histone modifications related to active gene regulation. The chromatin within the community shows a higher level of openness. In contrast to metaTADs39, which are formed by selecting and merging the two most frequently interacting neighboring TADs, TADs within a community exhibit significant spatial interactions but are not necessarily adjacent in genomic position (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the high-order interaction data, Mactop can detect chromunities40 by constructing networks based on similarities between multi-way reads. Compared to sub-TADs41, which are more isolated within the TAD, chromunities exhibit interaction patterns across multiple regions within the TAD. Chromunities typically include a core self-interacting region within the TAD and interactions between this core region and other areas within the TAD. This unique pattern in high-order data highlights the intricate interactions between diverse regions within TADs and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of chromatin organization. In summary, Mactop is a versatile, accurate, robust tool for identifying 3D chromatin structures from diverse types of chromatin maps.

Results

Overview of Mactop

For the initial chromatin interaction matrices, Mactop applies the normalization method42,43 to preprocess the data and help mitigate experimental errors (Fig. 1A). Mactop implements a block segmentation strategy along the main diagonal of the input matrix. Mactop performs a downsampling strategy on the submatrices and adds additional noise to measure the stability of TADs and boundaries. Mactop constructs a chromatin interaction graph for each resampled matrix, where the genomic bins serve as nodes, and the chromatin interactions between two bins form the edges. Mactop applies Markov clustering to the graph, where bins within the same cluster are considered to reside within the same TAD. The sampling and clustering process is repeated sufficiently, and the frequency of two bins appearing in the same cluster is tallied to construct a consistency matrix. Mactop calculates the consensus boundary score in the consistency matrix for each bin and applies a filtering algorithm to determine the final TAD boundary positions (Fig. 1B). Additionally, the types of boundaries can be categorized based on the consensus boundary score.

A Higher-order interaction reads data (top left) and paired reads data (top right). Higher-order interaction reads are decomposed into multiple paired reads through pairwise decomposition (bottom left) and then mapped to Hi-C interaction matrices (bottom right) based on a specified chromatin fragment length (resolution). B The mactop workflow for TAD identification in fixed-length chromatin segments. First, resample and add noise to the interaction matrix. Then, the interaction graph is constructed and clustered. From the clustering results, a consensus matrix is generated. TAD boundaries are then determined based on the consensus boundary score. C The left figure shows the heatmap of TADs identified based on the Hi-C interaction graph. The middle figure displays the heatmap of TAD communities identified from the TAD interaction graph. The right figure presents the heatmap of chromunities identified from the higher-order interaction graph.

Mactop also constructs the interaction graph between TADs and identifies TAD communities with Markov clustering. Furthermore, Mactop could build a similarity graph of multi-way reads in high-order interaction data, which retains more detailed high-order interaction information relative to the Hi-C interaction matrix. Mactop further applies Markov clustering to this graph and identifies the chromatin spatial proximal structures called chromunities (Fig. 1C). In summary, Mactop identifies TADs, domain communities, and chromunities from diverse high-throughput chromosome conformation capture datasets. The recommended parameters for Mactop are detailed in the Methods section.

Mactop could accurately and robustly identify TADs across Hi-C data with different resolutions and sequencing depths

We applied Mactop and three competing methods, Insulation Score (IS), Directionality Index (DI), and TopDom, to the Hi-C data of five cell lines from Rao et al.12. The numbers of TADs identified across different chromosomes in the five cell lines show variations among the four methods. While Mactop and TopDom identified a broader range of TADs, suggesting their effectiveness in reflecting robust chromatin interactions, IS and DI indicate a more conservative detection (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. S2A). The TAD boundaries identified by different methods showed relatively high consistency, with over 80% detected by at least two methods. Notably, about 95% of boundaries determined by DI were recognized by others. However, it has only 2,387 boundaries in total, significantly fewer than the other three methods, suggesting potential deficiency. In contrast, Mactop identified a higher number of boundaries and showed a lower proportion of boundaries with a low boundary score (the gray section), indicating a greater sensitivity to TAD boundary detection and an enhanced ability to uncover potential TAD boundaries (Fig. 2B).

A Number of TADs identified by each caller with a sample size of 23 representing the total number of chromosome. Outliers are indicated by black dots. B Boundary score of boundaries identified by each caller indicating only identified by itself (white) or identified by 1 (gray), 2 (orange), and 3 (red) other TAD callers. C Ratios of Directional Index (DI) and Insulation Score (IS) for each caller in GM12878, based on a sample size of 23 representing the total number of chromosomes. Higher scores indicate more pronounced interaction changes between upstream and downstream of boundary regions. Mactop differs significantly from TopDom and Insulation (p < 0.05). Outliers are indicated by black dots and extreme outliers are shown as circles. Refer to Supplementary Table S2 for details. D Evaluation of TADs using the silhouette coefficient based on a sample size of 23 representing the total number of chromosomes. Mactop differs significantly from Insulation and Directionality (p < 0.05). Black dots represent outliers. Refer to Supplementary Table S2 for details. E–F Similarities of TADs identified by the callers at different resolutions (E) and depths (F) based on a sample size of 23 representing the total number of chromosomes. Black dots represent outliers, while circles represent extreme outliers. Statistical significance is provided in Supplementary Table S2. G Signal intensity profile of CTCF around the boundary region for each caller. H Percentage of TADs with significant mean histone modification signal (p value < 0.05).

Based on the IS and DI ratios, the TAD boundaries identified by Mactop exhibited notable insulation and directionality compared to the other methods, with more stable performance (Fig. 2C). The silhouette coefficients of the four methods showed that Mactop performed exceptionally well, suggesting its validity and reliability from the clustering perspective (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. S2B). It is worth noting that the DI method exhibited good performance in terms of insulation and directionality metrics while identifying the minimal overall number of TADs. However, it performed worse in terms of the silhouette coefficient than other methods because DI mainly identifies distinct boundaries while potentially missing some hidden boundaries. However, Mactop performed well, highlighting its accuracy in TAD identification. We have provided the comparisons between Mactop and additional methods31,44,45 with the boundary DI, insulation ratio and silhouette coefficient in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Fig. S4A).

We further observed a notable decline of mutual information46 between the results on different datasets for the disparity as the resolution increased, particularly when comparing 25 kb with 100 kb versus 25 kb with 50 kb. Mactop was less affected than other methods, suggesting its relative stability and robustness at varying resolutions (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Fig. S2C). Mactop showed a slight decrease of mutual information at 90% down-sampling compared to methods like Insulation and Topdom and maintained higher mutual information at further reduced sampling rates (70%, 50%). Furthermore, Mactop demonstrates the ability to identify TADs across varying data volumes. Even at sampling rates as low as 5%, 1%, and 0.01%, Mactop robustly identifies TADs (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Fig. S3). This result indicates that Mactop can effectively identify potential TADs even as data quality decreases due to its graph structure-based approach likely, which is resilient to data perturbations and effective in representing topological structures (Fig. 2F, Supplementary Fig. S2D).

Mactop-TAD exhibits distinct enrichment of architectural proteins and histone modifications

TAD boundaries are characterized by the enrichment of architectural proteins, such as CTCF and cohesin elements (RAD21, SMC3), which play a significant role in the formation and functional maintenance of TADs47. In the GM12878 cell line, all methods showed distinct enrichment of CTCF at boundaries, whereas Mactop displayed slightly less enrichment than DI which tends to identify prominent boundaries. Similar patterns on RAD21 and SMC3 were also observed at boundaries in other cell lines (Fig. 2G, Supplementary Fig. S2F).

Within TADs, histone modifications are also widely distributed, playing a vital role in the cellular life processes by activating or repressing the expression of neighboring genes48. Since the number and size of TADs identified by different methods vary distinctly, directly averaging the signals within TADs is not an adequate measure of significant histone enrichment. We measure the degree of histone enrichment in TADs identified by each method with a random background. Among ten types of histone modification signals, TADs identified by Mactop and Topdom demonstrated better histone enrichment (Fig. 2H). Moreover, the histone modifications associated with pressing chromatin expressions such as H3K36me3, H3K79me2, and H3K79ac showed stronger signals, indicated by deeper colors. In short, compared to other methods, TADs identified by Mactop exhibit better biological characteristics both at the boundaries and within the TADs.

Mactop could divide the TAD boundaries into three types with different biological relevance

Mactop measures the stability of TAD boundaries by constructing a consistency matrix. In cell line GM12878, the boundaries were annotated by Mactop as stable, dynamic, and blurry types located on chromosome 2 within the range of 134.75 to 139.15 MB (Fig. 3A). Compared to the direct Hi-C interaction heatmap, the consistency matrix heatmap provides a more precise representation of the bin correlations. We adopted the Contrast Index (CI)49 to measure the interaction characteristics of a bin, with lower values indicating a greater ability of the bin to insulate interactions between its upstream and downstream regions. The TAD boundaries identified by Mactop correspond to the minima of the CI curve. The CI values corresponding to stable boundaries are relatively lower than the other two types of boundaries, indicating a more substantial capability in separating upstream and downstream interactions.

A Hi-C matrix at the top shows chromosomal interaction frequencies in GM12878 chromosome 2, with darker colors marking higher frequencies. The consistency matrix below indicates TAD frequencies with deeper colors for higher-frequency bins. Colored blocks beneath show TAD boundaries identified by Mactop, while the curve above shows the CI value of each bin. ChIP-seq signals for CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3 appear on separate tracks, and the reference sequence genes track at the bottom locates genes. B Numbers of three types of boundaries in the GM12878 cell line: stable (green), dynamic (blue), and blurry (lavender). C, D Average directionality index and insulation score profiles around the boundary region for each boundary type. E Peak signal intensity profile of average CTCF, RNA pol II, and H3K36me3 around the boundary region for each boundary type. F The percentage of TADs with significant mean histone modification signal (p value < 0.05). G Conservation ratio of two boundary types across different cell types based on a sample size of 23 representing the total number of chromosomes with significant differences (p < 0.05). Black dots represent outliers. See Supplementary Table S2 for details.

Further analysis reveals that signals such as CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3 are highly expressed at stable boundaries identified by Mactop. In contrast, dynamic boundaries also exhibit certain signal expressions, which are relatively weaker. This observation demonstrates that the boundaries determined by Mactop have strong biological relevance and suggests that TAD boundaries exhibit specific biological differences.

We quantified the number of each boundary type identified by Mactop in the GM12878 cell line (Fig. 3B). Stable boundaries are the most common, dynamic ones are the second, and blurry ones only account for 4%. The average directionality index signal indicates a significant change in the interaction patterns around the stable boundaries but relatively weaker changes for dynamic ones and almost no changes for blurry ones (Fig. 3C), suggesting the marked insulation differences between stable and dynamic boundaries but barely visible signals for blurry boundaries. Similarly, stable boundaries showed significant insulating effects compared to dynamic ones for upstream and downstream interactions, delineating the clear boundary differences. While the blurry ones displayed a slightly opposite trend (Fig. 3D). In short, the stable and dynamic boundaries show consistent biological relevance with TAD boundaries but exhibit distinct functional characteristics. The blurry boundaries and their adjacent regions may represent areas where chromatin interactions are relatively uniform without forming distinct TAD structures.

Both stable and dynamic boundaries exhibited significant enrichment of CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3 signals compared to a random background (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. S4B). Notably, the signal enrichment at stable boundaries was significantly higher than that at dynamic boundaries, indicating the differences in insulating function and stability between stable and dynamic boundaries may be related to the abundance of architectural proteins. Furthermore, RNA Pol II and histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K36me3, and H3K9ac), which mark active transcriptional regulation, were observed around both stable and dynamic boundaries (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. S4C). These modifications were significantly enriched at stable boundaries. In contrast, the enrichment at dynamic boundaries was weaker, indicating a close relationship between stable boundaries and active transcriptional regulation. Accordingly, TADs can be categorized into two types, i.e., the first consisting solely of stable boundaries and the second consisting of at least one dynamic boundary. Histone modification enrichment discerned that the first type of TADs showed distinct histone modification enrichment (Fig. 3F). Notably, the enrichment of promoters indicative of active chromatin expression (H3K4me1, H3K27ac) stood out more prominently than other modifications, indicating a tendency towards more active gene expression within TADs framed by stable boundaries.

To further verify the conservation of stable and dynamic boundaries across various cell lines, the boundary positions of TADs in the GM12878 cell line were used as a reference to compare with four other cell lines (Fig. 3G). The conservation of stable boundaries across cell lines was around 0.4, significantly higher than the conservation rate of 0.1 for dynamic ones, indicating that stable boundaries are more conserved across cell lines. In short, the two types of boundaries by Mactop exhibit distinct biological relevance and varying degrees of stability across different cell lines.

The TAD network could reveal the spatial topological relationships between TADs

We constructed a TAD interaction network with nodes representing individual TADs and edges signifying significant interactions between TADs. Taking chromosome 2 of the GM12878 cell line as an example, the visualization of the network’s adjacency matrix reveals square patterns distributed along the diagonal (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. S5A), suggesting that TADs exhibit spatial proximity in a specific organizational manner. In addition, some rectangular patterns can be observed at positions far from the diagonal, indicating that certain TADs tend to be spatially close despite being linearly distant. The average shortest path length between any two TADs in the TAD interaction network was 4.26 links (Fig. 4B), indicating most TADs are very closely linked and show the small-world property50. The degree distribution of the TAD interaction network suggests that most TADs have fewer than 20 connections and only a few TADs with more than 100 connections may act as hubs within the network (Fig. 4C). Overall, this distribution suggests the presence of a few highly connected hubs and many TADs with limited connections within the network, implying a potential hierarchical or modular structure of the network.

A TAD interaction frequencies in GM12878 chromosome 2, with darker red colors marking higher frequencies. B Distribution of the shortest path between pairs of TADs in the TAD interaction network. C Degree distribution of the TAD interaction network. D Clustering visualization of the TAD interaction network. E Degree distribution of the clustering coefficients of the TAD interaction network. F Degree distribution of the topological coefficients of the TAD interaction network. G Number of TADs within communities of varying sizes, the red bar represents isolated TADs, while the blue bar represents TADs within a community. H Spatial density of open chromatin between TADs forming communities and isolated TADs. The sample size is 1350 for isolated TADs and 3115 for community TADs with significant differences (p < 0.05). Black dots represent outliers, while circles represent extreme outliers. See Supplementary Table S2 for details. I Average signal intensity of several biological features within communities and isolated TADs in GM12878 with blue dots representing TADs within communities and red triangles representing isolated TADs. J Relative distributions of several biological features within communities and isolated TADs and their adjacent regions in GM12878 with the blue line representing TADs within communities and the red line representing isolated TADs. K Average conservation score of community TADs across different chromosomes in five cell lines. The sample size is 23 and black dots represent outliers.

Upon visualizing the TAD interaction network (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Fig. S5B), it is immediately apparent that some nodes within the network have more connections than others, forming dense intersections of lines, which could be the hubs. The overall network structure is divided into several distinct groups or clusters, which may represent TAD groups that are either spatially closer to each other or more functionally related. The average clustering coefficient51 of the TAD interaction network revealed that the coefficient tends to decrease as the number of connections increases, and TADs with fewer connections exhibit higher clustering coefficients, indicating they were part of highly clustered local groups (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Fig. S5C).

On the other hand, nodes with more connections have lower clustering coefficients, suggesting that they may connect multiple distinct groups and act as hubs within the network. This pattern is consistent with the characteristics of a hierarchical network where hub nodes link different clusters while non-hub nodes are more densely connected within their respective clusters. The topological coefficient of the TAD interaction network demonstrates a downward trend with an increasing number of connections. Nodes with fewer links typically have higher topological coefficients, indicating they may form closely-knit local clusters (Fig. 4F). However, diverging from the previously observed high clustering coefficients, even nodes with more connections maintain a relatively stable topological coefficient, suggesting that while there are some hub nodes, the overall network connectivity is homogeneous.

Mactop could identify TAD communities within a TAD network

The TAD interaction network shows the emergence of stable communities of TADs and Mactop could effectively identify them. In the GM12878 cell line, clusters of three or more TADs were identified as TAD communities. Based on the distribution of TAD community size and the number of TADs, approximately two-thirds of TADs tend to form TAD communities (Fig. 4G). To explore the differences between the two types of TADs, we adopted the spatial density of open chromatin (SDOC)52, which quantifies the openness of specified chromatin regions based on the Hi-C interaction maps and DNase-seq data. We could observe that TAD communities show higher SDOC than isolated TADs, suggesting that community TADs exhibit more significant overall activity than isolated ones, possibly because spatially proximate TADs can share more gene regulatory elements (Fig. 4H).

Based on the average biological signal enrichment analysis (Fig. 4I), community TADs showed significantly higher signals than isolated ones for architectural proteins such as CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3, which are crucial to defining TAD boundaries. Markers of chromatin activation, like H3K4me2 and H3K4me3, also exhibited increased presence in community TADs. While repressive histone modifications presented a slight difference, community TADs still demonstrated a slightly stronger signal. In addition, DNA methylation, DNase sensitivity, and RNA expression suggested greater chromatin openness and gene expression activity within community TADs. Similarly, community TADs had higher signals for transcription factors such as YY1 and RNA polymerase II (Pol2), indicating enhanced regulatory activities and transcriptional potential. These findings collectively suggested a distinct activity level in community TADs, indicating their potentially greater importance in cell function and gene regulation than isolated TADs. The average signal distribution of various biological markers within and at the boundaries of TADs showed that structural proteins such as CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3 were enriched at TAD boundaries, consistent with their critical role in maintaining TAD structure (Fig. 4J, Supplementary Fig. S5D). Histone modifications associated with gene activation (like H3K4me1 and H3K4me2) were enriched in the interior regions of TADs, and those linked to gene silencing (such as H3K9me3) had lower signals at the TAD center. DNase-seq signals indicated more open chromatin at the boundaries. Overall, community TADs universally exhibited higher signal intensities across all markers than isolated TADs, suggesting that community TADs may possess more complex gene regulatory networks and tighter gene expression control. These patterns indicate that the distribution of biological signals within TADs is complex and functionally diverse. In five cell lines, the conservation of community TADs was evaluated (see methods). Community conservation was defined based on an over 80% overlap of TAD positions across different cell lines. The average conservation of these community structures exceeded 50% across the five cell lines (Fig. 4K, Supplementary Fig. S5E).

To summarize, the architecture of TAD communities represents an organizational framework within the genome, wherein TADs harbor abundant functional elements shared among proximal TADs to facilitate coordinated gene regulation, and this structure tends to be positionally conserved across different cell lines.

Mactop could identify chromunities in high-order interaction data

In comparison to Hi-C data, higher-order interaction data offers a more comprehensive representation of the spatial proximity among multiple chromatin fragments, thereby enabling exploration of the spatial interactions occurring within specific chromatin regions.

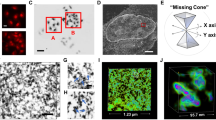

Mactop first identifies TADs on the interaction matrix mapped by higher-order interaction data (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, by utilizing higher-order interaction reads within a region, interaction proximity graphs can be constructed and clustered to reveal higher-order interaction clusters within that region. These clusters are centered on the specific chromatin regions, radiating out to other regions, and such structure is termed chromunity (Fig. 5B). By calculating interactions at different chromatin distances, chromunity exhibits significantly high interaction values within specific regions (Fig. 5C Top). By comparing to the background interactions, chromunity stands out by occupying a significant proportion of interactions in distinct regions, and this distribution showcases unique overlapping patterns (Fig. 5C Bottom). However, due to the spatial overlap of higher-order interactions, it becomes challenging to recognize this unique chromunity distribution within the Hi-C interaction matrix.

A Heatmap of the Hi-C contact matrix, dotted lines indicating the positions of TAD. B Heatmaps of four chromunity represented with different colors. C The contact frequency against genomic distance for four chromunity reads in the TAD (top), with the normalized observed/expected contact frequency for the same read illustrated at the bottom. D Number of TADs containing different numbers of chromunities in a single TAD. E Open chromatin signal between TADs and chromunities with a sample size of 129 for TADs and 395 for chromunities, showing significant differences (p < 0.05). Black dots represent outliers, and circles indicate extreme outliers. F Average histone modification signals in TADs, chromunities, metaTADs, and subTADs on 23 chromosomes. Chromunities show significant enrichment differences compared to other structures (p < 0.05). Black circles represent outliers. See Supplementary Table S2 for details. G Three examples in the GM12878 and K562 cell lines demonstrate TADs and the chromunities formed by different high-order interaction clusters within them. Top and middle heatmaps show the pairwise contact and multiway contact reads cluster within chromunity, respectively. The bottom panel shows the distribution of CTCF, DNase-seq, and various histone modifications in the corresponding region, along with the gene positions.

On chromosome 2 of the GM12878 cell line, the number of chromunities identified within different TAD regions was counted. The majority of TADs include 1-3 chromunities and a minority have four or more (Fig. 5D). Based on DNase-seq data, chromunity regions exhibit higher average signals compared to whole TAD regions, indicating that they are more accessible (Fig. 5E). Histone modifications associated with gene activation were also enriched in the Chromunity regions compared to TAD, MetaTAD, and SubTAD regions (Fig. 5F). Above, chromunity represents more accessible and active domains within chromatin, potentially due to their inherent ability to interact with more areas within the chromatin.

Mactop identified the TAD and chromunities (clusters 1, 2) within the GM12878 cell line on chromosome 2 between 105.4 to 105.6 MB (Fig. 5G Left). Chromunity showcases specific regions within the TAD with a high frequency of chromatin interactions, suggesting that the spatial interactions of chromatin among TADs are structurally organized. Moreover, the enrichment tracks provided the localization information of architectural proteins and epigenetic marks and showed a correlation between the regions of intense interaction in the chromunity and the peaks for CTCF. Similarly, regions of high interaction also coincided with marks of active chromatin, such as H3K4 methylation and DNase hypersensitivity, indicating these areas are transcriptionally active. The relationship between the high-order interaction clusters and the CTCF signals suggested that CTCF could mediate these complex interactions within the TAD, potentially contributing to the formation of sub-TAD structures or functional domains. Additionally, the genes involved in this region are also distributed within the two chromunities and do not span across them. This observation further supports the significance of chromunities in defining specific functional domains within the genome and their role in gene regulation.

In the GM12878 and K562 cell lines, Mactop detected TADs with similar locations and sizes but had differences in chromunity (Fig. 5G Center and Right). The variations in the high-order interaction clusters in K562, when compared to GM12878, could be due to distinct transcriptional programs, epigenetic landscapes, or differential protein-DNA interactions influencing the 3D chromatin structure. In conclusion, the differences in chromunity indicate cell-type-specific chromatin architecture and regulatory mechanisms. These cell type-specific patterns emphasize the dynamic nature of the genome and the specific biological context of each cell type modulates chromatin’s structural and functional features.

Discussion

In this study, we develop a simple but powerful tool, Mactop, for identifying TADs, TAD communities, and chromunities in chromatin maps. Mactop adopts a graph construction algorithm and the Markov clustering procedure tailored for various types of chromatin interaction data. The utilization of the Markov clustering algorithm is a noteworthy choice due to its ability to group samples into distinct clusters by maximizing intra-cluster similarity while minimizing inter-cluster connections, making it a promising candidate for the TAD identification task.

The main challenge in directly applying the Markov clustering algorithm to Hi-C data is the inherent complexity and high dimensionality of genomic interaction data. We propose a thoughtful solution using graph segmentation to address this challenge. It begins by dividing the high-dimensional data into moderately sized subgraphs, effectively mitigating the computational burden. The subsequent application of multiple perturbations and Markov clustering within each subgraph aims to identify consistent boundaries. Mactop effectively detects TADs by aggregating results from all subgraphs and provides a consistency-based metric for boundaries, highlighting the reliability of the boundary detection process.

Mactop has been extended to identify 3D ring-shaped chromatin structures, specifically chromatin loops12. In the GM12878 cell line, Mactop was successfully applied to identify loops within high-resolution Hi-C maps. Compared to other algorithms, Mactop demonstrates a distinct advantage in rapidly detecting loops over larger genomic regions. For further details see Supplementary Materials.

In the future, joint identification of TADs under multiple conditions could be a critical direction for a deep understanding of the conservation and variability of TADs across different biological states. Expanding mactop to identify nested or hierarchical structures of TADs, such as sub-TADs and meta-TADs, will provide a more granular analysis of chromatin regions. Improvements to the graph construction method, for example, by integrating similarity features from epigenomic data, will enhance the precision of TAD detection. With the increasing availability of single-cell Hi-C data53 and the development of data simulation methods54, there is now a growing opportunity to analyze the 3D chromatin structure in single cells. These directions will collectively advance the capabilities of Mactop at the forefront of high-order chromatin interaction data analysis.

Materials and methods

Pairwise decomposition of multi-way data

In the pairwise decomposition process, given a set of multi-way reads \(R=\left\{{r}_{1},{r}_{2},\ldots ,{r}_{n}\right\}\) consisting of n reads, we decompose it into all possible pairs of reads P. For every read ri and rj in R that interact, we define a pairwise relation pij. Subsequently, we construct an interaction matrix M, where Mij represents the frequency of interaction between ri and rj. For each \({p}_{{ij}}\in P\), we update the matrix M as follows: \({M}_{{ij}}={M}_{{ij}}+1\).

Constructing consistency matrix

The construction of a consistency matrix from a Hi-C matrix involves a process of iterative clustering with added noise, quantifying the co-occurrence of bin pairs in clusters across multiple iterations. Initially, the original Hi-C matrix is denoted as M, and n is defined as the number of clustering iterations with noise. For each iteration i (where I = 1,2,…,n), noise is added to M to create a perturbed matrix Mi, and clustering is performed to yield the result Ci. The consistency matrix CM is then initialized, with the dimension equals that of M, and for each pair of bins a,b, the frequency Counta,b of them being clustered together across all n results is counted. The consistency value for each bin pair is calculated \(C{M}_{a,b}=\frac{{{\mbox{Count}}}_{a,b}}{n}\). After evaluating all bin pairs, CM emerges as the final consistency matrix, representing the proportion of times each pair of bins was co-clustered, thereby revealing the stable clustering patterns and underlying genomic region relationships in the Hi-C data.

Generate the randomized TADs

To generate randomized TADs, the lengths of original TADs are preserved while their positions are randomized. Initially, each TAD i in the original set is represented by its length \({L}_{i}={en}{d}_{i}-{{{{\rm{start}}}}}_{i}\). A list of indices \(I=[1,2,\ldots ,n]\) corresponding to these TADs is created, where n is the total number of TADs. This list of indices is then randomized to produce a shuffled sequence I'. New TADs are generated by sequentially positioning them along the genomic region, starting from position 0. For each index j in I', a new TAD is defined with a start position currentPos and an end position \({endPos}={currentPos}+{L}_{{I}_{j}^{{\prime} }}\), and currentPos is updated for the next TAD. The initial position of currentPos is defined as the first bin of the data. The randomized TADs comprise tuples (currentPos, endPos), maintaining the original lengths but with randomized genomic locations. This approach ensures that the randomized TAD set mimics the length distribution of the original ones, providing a basis for comparative analyses while varying their spatial positioning.

Markov clustering algorithm (MCL)

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a graph where V is the set of vertices and E is the set of edges. Define A as the adjacency matrix of G, where Aij represents the weight of the edge between vertices i and j. If i and j are not directly connected, \({A}_{{ij}}=0\). Firstly, transform A into a stochastic matrix M by normalizing each row to sum to one, so that it represents transition probabilities of a random walk on the graph:

The MCL algorithm then iteratively applies two operations, expansion and inflation, to matrix M:

-

1.

Expansion (Matrix Squaring): M is replaced by M2, effectively simulating two steps of a random walk.

$$M={M}^{2}$$ -

2.

Inflation: Each element of M is raised to the power γ (inflation parameter) and renormalized to maintain stochasticity. Inflation controls the granularity of clustering by reinforcing intra-cluster transitions and weakening inter-cluster transitions.

After the inflation step, M is normalized to keep the matrix stochastic. These two steps are repeated until M converges, which means that multiple iterations do not significantly change M. The converged matrix M indicates the cluster structure of the graph, where dense blocks along the diagonal represent clusters.

Construct a TAD interaction network

For a set of TADs, denoted as \(T=\left\{{t}_{1},{t}_{2},\ldots ,{t}_{n}\right\}\), where each ti represents a TAD on the genome. We build a weighted graph \(G=(T,E,w)\) to represent TAD-TAD interaction, where the weight \(w(e)\) is defined as follows:

where Z is the z-score, calculated as \(\frac{\bar{{I}_{{{{\rm{tads}}}}}}-\mu }{\sigma }\), where \(\bar{{I}_{{tads}}}\) is the mean interaction strength between TADs ti and tj, μ is the mean of the background distribution of interactions, and σ is the standard deviation of the background distribution.

Construct a muti-way reads similar network

Given a subset of multi-way reads \(\tilde{D}\), we build a weighted graph \(G=(\tilde{D},E,w)\) of bin-wise concatemer overlap, where the weight \(w(e)\in [0,1]\) on each edge \(e=\left\{{d}_{1},{d}_{2}\right\}\in E\) represents the Jaccard similarity of concatemer pair \({d}_{1},{d}_{2}\in \tilde{D}\). A second weighted graph \(\hat{G}=(\tilde{D},\hat{E},\hat{w})\) is then built with weights \(\hat{w}(e)\) that represent the number of \(k=25\) nearest neighbors (that is, most similar) that are shared by each concatemer pair \(e\in \hat{E}\).

Recommended parameters

Mactop has two key parameters: Inflation and Variance. Inflation determines the granularity of clustering, while Variance affects the consistency of the results. We calculated the Silhouette coefficient across various parameter settings for both 10 kb and 50 kb data. The results suggest that the optimal settings are an Inflation value of 1.4 for 10 kb resolution and 1.5 for 50 kb resolution, with a consistent Variance of 0.2 for both (Supplementary Fig. S2G). Additional parameter recommendations are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Hi-C matrix normalization

We used the iterative correction and eigenvector decomposition method (ICE) for Hi-C data normalization. ICE normalizes Hi-C data by iteratively eliminating biases introduced by experimental procedures and intrinsic genomic properties, assuming equal visibility for all genomic loci. This process results in a corrected matrix of relative contact probabilities, allowing for more accurate and unbiased comparisons within and between datasets. The parameters for the ICE method are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

TAD-calling methods

We compared Mactop with three representative TAD-calling methods: the directionality index (DI) method, the insulation score (IS) method, and TopDom. For all methods, we used default or recommended parameters. The parameter for those methods are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Directionality index (DI)

The DI method calculates the DI score for each genomic bin to determine its tendency for more frequent interactions with either upstream or downstream regions, thus indicating its directional bias. These scores are then analyzed using a hidden Markov model to ascertain the state of each bin (such as upstream-biased, downstream-biased, or unbiased). Ultimately, bins exhibiting significant directional bias are identified as TAD boundaries.

Insulation score (IS)

The IS method defines a sliding window to calculate an insulation score for each genomic bin on a chromatin contact map. The score is derived from the average number of DNA-DNA interactions within the window. Local minima in the vector of these insulation scores are considered indicators of TAD boundaries, indicating regions where chromatin’s internal interactions exceed interactions with external regions, thereby defining the boundaries of TADs.

TopDom

TopDom applies a fixed-size sliding window on the Hi-C contact matrix to detect interaction patterns between chromatin regions. TopDom identifies local maxima of interaction frequencies within each window as candidate TAD boundaries, followed by calculating scores for these boundaries to determine the actual TAD borders. The scoring system in TopDom is based on the variation in interaction frequency near the boundaries with higher scores indicating a higher likelihood of being TAD boundaries.

TAD evaluation criteria

We evaluate the TAD quality through diverse enrichment metrics alongside internal validation metrics typically employed.

Internal validation metrics

Based on the characteristics of TADs in the Hi-C interaction matrix, various metrics have been designed to assess the properties of chromatin segments. We have chosen the Insulation score, Directionality Index, Contrast index, and the Silhouette Coefficient, a metric for evaluating clustering results, to measure the properties of TAD boundaries.

Insulation score ratio

For a specific bin b, we calculate the insulation scores for defined regions upstream \(\left({I}_{u}\right)\) and downstream \(\left({I}_{d}\right)\) of it. The length of these regions is denoted as l. Insulation scores for each bin x within these regions are computed using the formula \({I}_{x}=\frac{{\sum }_{k=x-w}^{x+w}{\sum }_{l=y-w}^{y+w}{M}_{k,l}}{{w}^{2}}\), where Mk,l is the interaction value in the interaction matrix, and w is the window size. The slope S is then determined as \(S=\frac{{I}_{\max }-{I}_{\min }}{2l}\), where \({I}_{\max }\) and \({I}_{\min }\) are the maximum and minimum insulation scores in the combined upstream and downstream regions. This slope quantifies the variation in insulation scores and serves as a metric to evaluate TAD boundary characteristics in the specified region.

Directionality index (DI)

DI is computed for a defined length \((l)\) around the bin b using the formula: \(D{I}_{i}=\frac{{\sum }_{j=i+1}^{i+l}{M}_{i,j}-{\sum }_{j=i-l}^{i-1}{M}_{i,j}}{{\sum }_{j=i+1}^{i+l}{M}_{i,j}+{\sum }_{j=i-l}^{i-1}{M}_{i,j}}\), where Mi,j represents the interaction frequency between bins in the Hi-C matrix. The slope of the DI is then determined by calculating the difference between the maximum and minimum DI values within this region, divided by the total length of the region \((2l)\). This slope provides a quantitative measure of the change in interaction directionality and is particularly useful for identifying and characterizing TAD boundaries in the genomic region surrounding the selected bin.

Contrast index (CI)

CI is calculated by assessing interactions between a chosen number of upstream and downstream bins (n) around a specified bin b. The formula incorporates the sum of interactions U and D across these n bins upstream and downstream, respectively, and is defined as \(U={\sum }_{i=b-n}^{b-1}{\sum }_{j=b-n}^{b-1}{M}_{i,j}\) and \(D={\sum }_{i=b+1}^{b+n}{\sum }_{j=b+1}^{b+n}{M}_{i,j}\), where \({M}_{i,j}\) denotes the interaction frequency in the Hi-C matrix. CI is then calculated as \({CI}=\frac{U+D}{2\times \left({\sum }_{i=b-n}^{b}{\sum}_{j=b}^{b+n}{M}_{i,i}\right)}\), with the denominator summing the internal interactions within the region around b. This index is especially useful for quantitatively analyzing interaction strengths and patterns, aiding in identifying and understanding the dynamics of chromatin interactions around TAD boundaries.

Enrichment analysis

Enrichment of known architectural proteins

We calculate the enrichment of three known architectural proteins (CTCF, RAD21, and SMC3) in the TAD boundaries of five cell lines from Rao et al.12. TAD boundaries are defined by the starting bin and the ending bin of each predicted TAD, along with one preceding the starting bin and one following the ending bin. Let N be the total number of bins in a chromosome, nbind be the number of bins with one or more ChIP-seq peaks or accessible motif sites, ntad be the number of TAD boundary bins, and \({n}_{{tad}-{bind}}\) be the number of TAD-boundary bins with a binding event (ChIP-seq peak or accessible motif match site). The fold enrichment for a particular protein is calculated as: \(\frac{{n}_{{tad}-{bind}}/{n}_{{tad}}}{{n}_{{bind}}/n}\). Within each cell line, the fold enrichment across all chromosomes is averaged and then the mean across cell lines is used to rank the TAD-calling methods.

Histone modification enrichment

We use the proportion of predicted TADs that are significantly enriched in histone modification signals (compared to the “null” histone-modification signal distribution of randomly shuffled TADs) as a validation metric to assess the quality of TADs, similar to Roy et al.44. For each TAD, we calculate the mean histone modification ChIP-seq signal within the TAD. Next, we find the “null” histone-modification signal distribution from randomly shuffled TADs. To generate randomly shuffled TADs, we take the lengths of all predicted TADs within a chromosome, as well as the lengths of interspersed stretches between the TADs (i.e., “non-TAD” stretches) if a TAD-calling method skips over regions of the genome. Next, we randomly move around the TAD and non-TAD stretches within the chromosome to preserve the TAD length distribution. We repeat this procedure ten times. Then, we compute the mean histone modification ChIP-seq signal within these randomly shuffled TADs, generating the null or background distribution of histone modification signals. The empirical p-value of a predicted TAD’s histone modification signal is calculated as the proportion of randomly shuffled TADs with higher ChIP-seq signal than that of the given TAD. A TAD was significantly enriched if its empirical p-value was less than 0.05, i.e., more than 95% of randomly shuffled TADs have a lower histone modification signal. Finally, we get the proportion of predicted TADs with significant histone modification signals.

Histone modification enrichment across the two TAD categories

We explored whether the TADs demarcated by different types of boundaries showed enrichment of various histone modifications. Thus, we first divided the TADs into different clusters according to their boundary types. We call a TAD stable if it is surrounded by two stable boundaries, and we call a TAD dynamic if its two boundaries contain at least one dynamic boundary. Furthermore, using the method mentioned in the Histone Modification Enrichment section, we examined the number of histone modification enrichments in different types of TADs and divided this by the total number of TADs of that type to obtain the histone modification enrichment proportion for each type of TAD.

Downsampling of the Hi-C interaction matrix

The downsampling of Hi-C data aims at simulating lower sequencing depths. This process methodically decreases the original interaction frequencies, maintaining a specific percentage, denoted as p, of the data. This is achieved through the following:

Define sampling depth percentage

Set the percentage of data to be retained, denoted as p, which is a value between 0 and 100.

Original interaction matrix

The original Hi-C interaction matrix is represented as M, where each element Mi,j indicates the frequency between genomic loci i and j.

Detailed downsampling process

For each interaction element Mi,j, we calculate the expected number of interactions to retain: \({E}_{i,j}={M}_{i,j}\times \frac{p}{100}\), and generate a random number for each interaction, denoted as Ri,j, uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. The downsampled interaction \({M}_{i,j}^{{\prime} }\) is determined using a thresholding method:

where \({{\lceil }}\cdot {{\rceil }}\) is the ceiling function and \({{\lfloor }}\cdot {{\rfloor }}\) is the floor function. The matrix M' represents the downsampled Hi-C data, with each element \({M}_{i,j}^{{\prime} }\) reflecting the interaction frequency adjusted for the chosen sampling depth p.

Community conservation score

Let Ci represent the community structure in the i-th cell line, and let Bj represent a specific bin on the chromosome. Define the conservation score Si for bin Bj as:

where n is the total number of cell lines. \(I({B}_{j}\in {C}_{i})\) is an indicator function, which equals 1 if bin Bj is part of a community in the i-th cell line \(({B}_{j}\in {C}_{i})\), and 0 otherwise. For a specific community C within a cell line, define the Community Conservation Score SC as the average of the conservation scores of all bins within that community:

where \(\left|C\right|\) is the number of bins in community C.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data were presented as boxplots, showing the median and interquartile range (IQR), based on at least three independent analyses. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for each dataset. For the comparisons between any two groups, an independent two-sample t-test was used, and if the normality assumption was violated, a Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05. All hypothesis tests were performed using the SciPy Python library.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

High-throughput chromosome conformation capture datasets: We applied Mactop to the interaction count matrices from in situ Hi-C (with MboI as the restriction enzyme) for five cell lines: GM12878, NHEK, HMEC, HUVEC, and K562 at 25-kb, 50-kb, and 100-kb resolution (GEO accession: GSE63525), respectively. We also used the Pore-C data for the GM12878 cell line (GEO accession: GSE114242, GSE202539). ChIP-seq, DNase-seq, ATAC-seq, and motif datasets: We obtained several ChIP-seq datasets to interpret results by Mactop and other methods. For CTCF, the ChIP-seq narrow-peak datasets were available as ENCODE Uniform TFBS composite track were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser (wgEncodeEH000029,wgEncodeEH000075,wgEncodeEH000054,wgEncodeEH000042, wgEncodeEH000063). The ChIP-seq data (H2A.Z, H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K36me3, H3K79me2, H4K20me1, YY1) were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser (wgEncodeEH000014,wgEncodeEH000021,wgEncodeEH000027,wgEncodeEH000064, wgEncodeEH000062, wgEncodeEH000066, wgEncodeEH000068). The source data behind the graphs in this paper can be downloaded from the Supplementary Data.

Code availability

The code of data processing and Mactop is accessible via this link on Zenodo55: https://zenodo.org/records/14575324 and GitHub: https://github.com/zhanglabtools/Mactop.

References

Bonev, B. & Cavalli, G. Organization and function of the 3D genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 661–678 (2016).

Krijger, P. H. L. & De Laat, W. Regulation of disease-associated gene expression in the 3D genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 771–782 (2016).

Rowley, M. J. et al. Evolutionarily conserved principles predict 3D chromatin organization. Mol. Cell 67, 837–852.e7 (2017).

Szabo, Q., Bantignies, F. & Cavalli, G. Principles of genome folding into topologically associating domains. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw1668 (2019).

Walker, L. M. et al. Broad and Potent Neutralizing Antibodies from an African Donor Reveal a New HIV-1 Vaccine Target. Science 326, 285–289 (2009).

Rowley, M. J. & Corces, V. G. Organizational principles of 3D genome architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 789–800 (2018).

Quinodoz, S. A. et al. Higher-order inter-chromosomal Hubs Shape 3D genome organization in the nucleus. Cell 174, 744–757.e24 (2018).

Deshpande, A. S. et al. Identifying synergistic high-order 3D chromatin conformations from genome-scale nanopore concatemer sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1488–1499 (2022).

Zheng, H. & Xie, W. The role of 3D genome organization in development and cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 535–550 (2019).

Chakraborty, A. & Ay, F. The role of 3D genome organization in disease: From compartments to single nucleotides. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 90, 104–113 (2019).

Cremer, T. & Cremer, C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 292–301 (2001).

Rao, S. S. P. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014).

Dixon, J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012).

Crane, E. et al. Condensin-driven remodelling of X chromosome topology during dosage compensation. Nature 523, 240–244 (2015).

Tang, Z. et al. CTCF-mediated human 3D genome architecture reveals chromatin topology for transcription. Cell 163, 1611–1627 (2015).

Kim, S., Yu, N.-K. & Kaang, B.-K. CTCF as a multifunctional protein in genome regulation and gene expression. Exp. Mol. Med. 47, e166–e166 (2015).

Van Steensel, B. & Furlong, E. E. M. The role of transcription in shaping the spatial organization of the genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0114-6 (2019)

Ghavi-Helm, Y. et al. Highly rearranged chromosomes reveal uncoupling between genome topology and gene expression. Nat. Genet. 51, 1272–1282 (2019).

Luo, X. et al. 3D Genome of macaque fetal brain reveals evolutionary innovations during primate corticogenesis. Cell 184, 723–740.e21 (2021).

Stadhouders, R., Filion, G. J. & Graf, T. Transcription factors and 3D genome conformation in cell-fate decisions. Nature 569, 345–354 (2019).

Haarhuis, J. H. I. et al. The Cohesin release factor WAPL restricts chromatin loop extension. Cell 169, 693–707.e14 (2017).

Holzmann, J. et al. Absolute quantification of cohesin, CTCF and their regulators in human cells. eLife 8, e46269 (2019).

Shin, H. et al. TopDom: an efficient and deterministic method for identifying topological domains in genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 44, e70 (2016).

Haddad, N., Vaillant, C. & Jost, D. IC-Finder: inferring robustly the hierarchical organization of chromatin folding. Nucleic Acids Res. gkx036 https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx036. (2017)

Ye, Y., Gao, L. & Zhang, S. MSTD: An efficient method for detecting multi-scale topological domains from symmetric and asymmetric 3D genomic maps. Nucleic Acids Res 47, e65 (2019).

Soler-Vila, P., Cuscó, P., Farabella, I., Di Stefano, M. & Marti-Renom, M. A. Hierarchical chromatin organization detected by TADpole. Nucleic Acids Res 48, e39 (2020).

Lévy-Leduc, C., Delattre, M., Mary-Huard, T. & Robin, S. Two-dimensional segmentation for analyzing Hi-C data. Bioinformatics 30, i386–i392 (2014).

Ron, G., Globerson, Y., Moran, D. & Kaplan, T. Promoter-enhancer interactions identified from Hi-C data using probabilistic models and hierarchical topological domains. Nat. Commun. 8, 2237 (2017).

Serra, F. et al. Automatic analysis and 3D-modelling of Hi-C data using TADbit reveals structural features of the fly chromatin colors. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005665 (2017).

Yan, K.-K., Lou, S. & Gerstein, M. MrTADFinder: A network modularity based approach to identify topologically associating domains in multiple resolutions. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005647 (2017).

Norton, H. K. et al. Detecting hierarchical genome folding with network modularity. Nat. Methods 15, 119–122 (2018).

Li, A. et al. Decoding topologically associating domains with ultra-low resolution Hi-C data by graph structural entropy. Nat. Commun. 9, 3265 (2018).

Dali, R. & Blanchette, M. A critical assessment of topologically associating domain prediction tools. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 2994–3005 (2017).

Zufferey, M., Tavernari, D., Oricchio, E. & Ciriello, G. Comparison of computational methods for the identification of topologically associating domains. Genome Biol 19, 217 (2018).

Liu, K., Li, H., Li, Y., Wang, J. & Wang, J. A comparison of topologically associating domain callers based on Hi-C data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 1–1 https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2022.3147805 (2022)

Dang, D., Zhang, S.-W., Duan, R. & Zhang, S. Defining the separation landscape of topological domains for decoding consensus domain organization of the 3D genome. Genome Res 33, 386–400 (2023).

Dang, D., Zhang, S.-W., Dong, K., Duan, R. & Zhang, S. Uncovering topologically associating domains from three-dimensional genome maps with TADGATE. Nucleic Acids Res. gkae1267 https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1267 (2024)

Rousseeuw, P. J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 20, 53–65 (1987).

Fraser, J. et al. Hierarchical folding and reorganization of chromosomes are linked to transcriptional changes in cellular differentiation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 852 (2015).

Zhong, J.-Y. et al. High-throughput Pore-C reveals the single-allele topology and cell type-specificity of 3D genome folding. Nat. Commun. 14, 1250 (2023).

Narendra, V., Bulajić, M., Dekker, J., Mazzoni, E. O. & Reinberg, D. CTCF-mediated topological boundaries during development foster appropriate gene regulation. Genes Dev 30, 2657–2662 (2016).

Imakaev, M. et al. Iterative correction of Hi-C data reveals hallmarks of chromosome organization. Nat. Methods 9, 999–1003 (2012).

Hu, M. et al. HiCNorm: removing biases in Hi-C data via Poisson regression. Bioinformatics 28, 3131–3133 (2012).

Lee, D.-I. & Roy, S. GRiNCH: simultaneous smoothing and detection of topological units of genome organization from sparse chromatin contact count matrices with matrix factorization. Genome Biol 22, 164 (2021).

Liu, J., Li, P., Sun, J. & Guo, J. LPAD: using network construction and label propagation to detect topologically associating domains from Hi-C data. Brief. Bioinform. 24, bbad165 (2023).

Shannon, C. E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

De Wit, E. TADs as the Caller Calls Them. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 638–642 (2020).

Andrey, G. et al. Characterization of hundreds of regulatory landscapes in developing limbs reveals two regimes of chromatin folding. Genome Res 27, 223–233 (2017).

Zhan, Y. et al. Reciprocal insulation analysis of Hi-C data shows that TADs represent a functionally but not structurally privileged scale in the hierarchical folding of chromosomes. Genome Res 27, 479–490 (2017).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Strogatz, S. H. Exploring complex networks. Nature 410, 268–276 (2001).

Jiang, S. et al. Spatial density of open chromatin: an effective metric for the functional characterization of topologically associated domains. Brief. Bioinform. 22, bbaa210 (2021).

Arrastia, M. V. et al. Single-cell measurement of higher-order 3D genome organization with scSPRITE. Nat Biotechnol 40, 64–73 (2022).

Fan, S. et al. scHi-CSim: a flexible simulator that generates high-fidelity single-cell Hi-C data for benchmarking. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, mjad003 (2023).

Duan, R., Dang, D., Fan, S., Yao, S. & Zhang, S. Deciphering chromatin domain, domain community and chromunity for 3D genome maps with Mactop. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14575324 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [No. 2019YFA0709501 to S.Z.], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 32341013, 12326614, 12126605], the R&D project of Pazhou Lab (Huangpu) [No. 2023K0602 to S.Z.], and the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research [No. YSBR-034 to S.Z.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. conceived and supervised the project. R.D. and D.D. designed and implemented Mactop algorithm. R.D., D.D. and S.F. validated the study. R.D., S.Y. and S.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jiapei Yuan, Zhijun Duan and Cizhong Jiang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kuangyu Yen and Aylin Bircan, David Favero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, R., Dang, D., Fan, S. et al. Deciphering chromatin domain, domain community and chromunity for 3D genome maps with Mactop. Commun Biol 8, 1290 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07635-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07635-6