Abstract

Phage therapy is a promising antibacterial strategy against the antibiotic resistance crisis. The evolved phage resistance could pose a big challenge to clinical phage therapy. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive analysis of phage resistance mechanisms during treatment. Here, we characterize 37 phage-resistant mutants of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strain SCNJ1 under phage-imposed selection in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. We show that 97.3% (36/37) of phage-resistant clones possessed at least one mutation in genes related to the CPS biosynthesis. Notably, the wcaJ gene emerges as a mutation hotspot, as mutations in this gene are detected at a high frequency under both conditions. In contrast, mutations in wzc exhibit more association with in vivo samples. These CPS-related mutants all exhibit compromised bacterial fitness and attenuated virulence in mice. Strain CM8 is the only non-CPS-related mutant, which has a bglA mutation that confers phage resistance and retains full fitness and virulence. This study highlights that laboratory characterization of phage resistance evolution can give useful insights for clinical phage therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance poses a substantial threat to the control of infectious diseases. Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is an important opportunistic pathogen causing several infections such as bacteremia, urinary and respiratory tract infections, and pyogenic liver abscess1. Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae has emerged worldwide and was listed as a critical-priority bacteria by the World Health Organization in 20172. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) can cause life-threatening, community-, and hospital-acquired infections in healthy individuals3. Therefore, the convergence of carbapenem resistance and hypervirulence in K. pneumoniae makes it a major infection control challenge4. In this case, phage therapy, relying on bacteriophage (phage) to target and kill bacteria, has gained fresh attention as an alternative treatment for carbapenem-resistant hvKp infections.

An increasing number of successful clinical phage therapies have been reported5,6,7, supporting the idea of phage therapy as a safe and promising strategy against antimicrobial-resistant infections8. Nevertheless, a big challenge for clinical phage application is the evolution of phage resistance in bacteria. Among the varied phage defense mechanisms, gene mutations related to the phage receptor were assumed to be the most common strategy9. For most Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, receptors recognized by phages mainly include components of the bacterial cell wall or protruding structures, such as capsular polysaccharides (CPS), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), pili, and flagella, and also outer membrane proteins (OMPs)10. In K. pneumoniae, CPS is considered as the primary receptor for most phages, and the LPS, the major porin OmpK36, or the siderophore receptor FepA has been identified as a binding receptor to trigger infection11,12,13.

During phage treatment, phage resistance mutants that evolved from a clonal bacterial population have been shown to emerge readily14,15. In K. pneumoniae, the loss or mutation of the capsule is the most common cause mediating phage resistance, and mutations in cps gene clusters, such as wcaJ16, mshA17, and wzc14 were assumed as the genetic basis in previous studies. Besides, truncated LPS, caused by mutations in LPS synthesis gene cluster or deletion in fabF, and mutated OmpC could also lead to phage resistance18,19. In association with the development of phage resistance, mutants of K. pneumoniae generally displayed reduced bacterial fitness and virulence18,20,21, and some became more sensitive to antibiotics22. Suffering from phage-imposed genetic trade-offs, mutants would be more likely to be cleared by the human immune system or be killed by the antibiotics used in combination, which is a double effect of phage therapy23. Phage therapy would thus benefit from clarifying the phage resistance evolution during treatment.

In this study, we employed two different phages to impose strong selective pressure on the host hvKp SCNJ1 by in vitro phage-bacteria coculture and in vivo pneumoniae treatment in mice infected by SCNJ1. We identified the bacterial genetic mutations under phage-imposed selection and investigated how the phage resistance evolution may affect bacterial fitness and virulence traits. We demonstrate that CPS mutations are the main reasons for mediating the evolution of phage resistance under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, accompanied by compromised bacterial fitness and attenuated virulence in hvKp SCNJ1. Additionally, the mutation in the bglA gene also mediates phage resistance, and the bacteria exhibit no reduction in fitness or virulence. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been previously reported in K. pneumoniae.

Results

Recovery of phage-resistant mutants

Phage resistance was tested by inverted spotting plate assays, and the formation of bacterial lawns of resistant mutants on the plate containing podovirus vB_KpnA_SCNJ1-Z (for brevity, referred to here as SCNJ1-Z) or siphovirus vB_KpnS_SCNJ1-C (referred to here as SCNJ1-C) indicated resistance. As a result, eighteen spontaneous mutants resistant to SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C after prolonged (12 h) incubation of bacteria-phage cocultures were selected as representatives for further assays. Meanwhile, nineteen resistant clones recovered from mouse lungs after phage SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C treatment of SCNJ1 were selected. The phage-resistant mutants against SCNJ-C that emerged in culture medium (n = 9) and mice (n = 10) were named CR (CR1 to CR9), and CM (CM1, CM3, CM8, CM9, CM10, CM13, CM17, CM19, CM20, CM22), respectively (Fig. 1a). The resistant mutants against SCNJ-Z that emerged in culture medium (n = 9), and mice (n = 9) were named ZR (ZR1 to ZR9), and ZM (ZM1, ZM5 to ZM12), respectively (Fig. 1a). Additionally, 20 clones randomly selected from the lungs of three mice in the untreated group retained their susceptibility to phage SCNJ1-Z and SCNJ1-C, indicating that the emergence of phage resistance was not driven solely by the selection pressure of the immune system (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Inverted spotting assay. The phage-resistant mutants and control strains (negative control, SCNJ1; positive control, a K47 serotype K. pneumoniae strain SCNJ2; blank control, LB medium) were grown on the LB agar plate containing 109-1010 CFU of phage (SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C). The upper two plates show the phage-resistant mutants selected in the mouse experiments (CM and ZM strains, respectively), and the lower two plates show the phage-resistant mutants selected in culture medium (CR, and ZR strains, respectively). b Sensitivity of phage-resistant mutants against phage SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C. EOP is the efficiency of plating. Darker red indicates the greater efficacy of a phage (higher EOP) in infecting a strain. LOD (limit of detection) indicates no plaques were observed. For the ZM group, statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests were further conducted on ANOVA [F (9, 20) = 2580, p < 0.0001]. For the ZR group, the data was firstly transformed with the formula: Y = EXP (X), and statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test [F (9, 20) = 1.705e + 066, p < 0.0001]. c Suppression of bacterial growth. The growth suppression of SCNJ1 and phage-resistant mutants by phage SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C was expressed as a percentage of the area under the growth curve of the control, corresponding to the suppression of the bacterial culture, calculated using the formula: [(Area of control – Area of phage treatment)/Area of control] × 100%. The presented data, shown as mean ± SD (n = 3), are from a representative experiment. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test [For the CM group, F (10, 22) = 32.25, p < 0.0001; For the ZM group, F (9, 20) = 51.53, p < 0.0001; For the CR group, F (9, 20) = 60.43, p < 0.0001; For the ZR group, F (9, 20) = 195.2, p < 0.0001]. The growth curves and growth inhibition curves of SCNJ1 and phage-resistant mutants are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. d Cross-resistance of phage-resistant mutants. The phage resistance pattern of each mutant against phage SCNJ1-Z, SCNJ1-C, or SCNJ1-Y (short for vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y) was identified by inverted spotting assay and shown as the heatmap of resistance using the RBG values. The RBG was distinguished by the size of colonies after being incubated for 10 to 12 h (The original pictures of the inverted spotting assay were presented in Supplementary Fig. 2). Color shading reflects the resistance type ranging from dark blue (full resistance) to light gray (full susceptibility).

The selected resistant mutants were further confirmed by EOP experiments and growth kinetic assays. EOP results indicated that all other ZM and ZR mutants were resistant, except ZM9 (80.15 ± 3.402%, p < 0.0001 vs. SCNJ1) and ZR7 (76.19 ± 1.174, p < 0.0001 vs. SCNJ1), which were only partially resistant to SCNJ1-Z (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2). This result suggests that ZM9 and ZR7 were incomplete-resistant mutants. All the CR and CM mutants are completely resistant to SCNJ1-C (Fig. 1b). As expected, phages SCNJ1-Z and SCNJ1-C efficiently inhibited the growth of SCNJ1, while they did not affect the growth of all the mutant clones (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Each phage-resistant mutant was also evaluated for cross-resistance to SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C. Plated isolates were categorized as resistant, partially resistant, or susceptible based on the appearance of overlying phage spots (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 4). Results showed that all SCNJ1-C-resistant isolates were resistant to SCNJ1-Z and all the SCNJ1-Z-resistant isolates, except ZR7, and ZM9, were also resistant to SCNJ1-C. These results suggest that SCNJ1-C and SCNJ1-Z may utilize the same receptor. We also tested their cross-resistance to the myovirus vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y phage which was isolated from the same host strain SCNJ1. Results showed that only two of these phage-resistant mutants were completely resistant to vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y, indicating that vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y may explore alternative receptors (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Phenotypic characterization of phage-resistant mutants

The colonies of the wild-type SCNJ1 were mucoid with smooth, big colonies and a wet surface (‘msbw’ morphotype) on the LB blood agar plate. The resistant mutants generally displayed non-mucoid morphology with small colonies, and a dry surface (‘nmsd’ morphotype, e.g., CM22), indicating loss of capsule, except that three mutants (CR5, CM8, and ZM10) exhibited ‘msbw’ morphotype similar to SCNJ1 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 1). String test and sedimentation assay indicated that these ‘msbw’ morphotypes retained the hypermucoviscous (Hmv) phenotype as that of SCNJ1, while those ‘nmsd’ isolates generally became hypomucoviscous (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 1). There is one exception, the ‘msbw’ isolate CR5 was interpreted as Hmv by sedimentation assay, but could not form a “string” of >5 mm. The complementation of wild-type wzc from SCNJ1 into CR5 restored the positive string test. The underlying mechanism for this discrepancy remains unknown.

a Representative colony morphologies of K. pneumoniae SCNJ1 and representative strains of phage-resistant mutants on LB blood agar plates. Boxes indicate areas of increased magnification. The 1 cm scale is indicated. The colony morphology of all the phage-resistant mutants is presented in Supplementary Fig. 5. b The area under the growth curve of SCNJ1 and phage-resistant mutants. The presented data, shown as mean ± SD (n = 3), are from a representative experiment. The growth curves were converted into AUC (Area Under the Curve) by GraphPad Prism 10.1.2 to evaluate the growth abilities of SCNJ1 and the page-resistant mutants. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was further conducted on ANOVA [For the CM group, F (10, 22) = 32.55, p < 0.0001; For the ZM group, F (9, 20) = 6.596, p = 0.0002; For the CR group, F (9, 20) = 0.8735, p = 0.5633; For the ZR group, F (9, 20) = 7.586, p < 0.0.0001]. The growth curves of SCNJ1 and phage-resistant mutants are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

The growth curves of all the mutant clones were compared to SCNJ1 in a rich-nutrient medium (Supplementary Fig. 3). Results showed that some mutants, including CM1, CM3, CM19, CM20, CM22, ZM10, and ZR9, exhibited significantly reduced growth kinetics compared to SCNJ1, as revealed by analysis of the area under the curve (Fig. 2b), suggesting a potential fitness cost.

Previous studies have shown that phage-imposed resistance may be accompanied by altered antibiotic susceptibilities as an adaptive trade-off15,22. Therefore, we performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing for these phage-resistant mutants. When compared with the parental SCNJ1, some mutants had an increase of 1–7.5 mm in the diameter of the inhibition zone for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 0.5–9.5 mm for aztreonam, 0.5–6.5 mm for tigecycline, 0.5–5 mm for tetracycline, 0.5–7.5 mm for amikacin, 0.5–7 mm for gentamicin, 1–9 mm for ciprofloxacin, 0.5–2 mm for meropenem, and 0.5–7 mm for imipenem (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, according to the threshold recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), there were no substantial changes from resistance to sensitivity following the phage-resistance evolution.

Genetic changes associated with phage resistance

To characterize the molecular mechanisms associated with their resistance, whole genome sequences of 37 phage-resistant mutants abovementioned were mapped to the parental SCNJ1 reference genome [GenBank accession no. CP174529 (chromosome), CP174530 (pVir-SCNJ1), CP174531 (pNDM5-SCNJ1)] respectively. A summary of high-probability mutations detected in these resistant isolates is shown in Table 1. The analysis revealed a total of 68 mutations, encompassing 27 distinct mutations. Among them, 24 were predicted to impact the function of the encoded proteins, consisting of 11 missense mutations, 7 insertion mutations, 4 frameshift mutations, 1 deletion mutation, and 1 nonsense mutation (Fig. 3a and Table 1). Each resistant mutant carries at least one mutation. Interestingly, all the phage-resistant isolates from in vivo samples had a synonymous mutation (A77A, GCC → GCT) in the glycerol kinase gene glpK, as confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Although the synonymous mutations did not alter the amino acid sequence of the resulting protein, these mutations can alter the mRNA and, therefore, affect fitness24. Sanger sequencing also revealed that none of the 15 randomly selected isolates from the lungs of three untreated mice had this point mutation, indicating that the glpK mutation is most likely to have emerged as a result of combined selective pressures from phages and those from the mice’s internal environment, such as the immune system.

a The heatmap shows the genetic mutations of 37 phage-resistant clones. The glpK, mutated genes related to CPS biosynthetic pathways, and other mutations are colored green, red, and blue, respectively. b The adsorption efficiencies of SCNJ1-C or SCNJ1-Z to phage-resistant mutants. SCNJ1 served as the positive control. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments in triplicate. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was further conducted on ANOVA [For the C group, F (19, 40) = 66.73, p < 0.0001; For the Z group, F (18, 38) = 46.26, p < 0.0001]. c Representative spot assays of the wild-type SCNJ1, phage-resistant mutants (CM22, CR5, ZM10, and CM8), complemented strains (CM22/pSTV28-wzc, CR5/pSTV28-wzc, ZM10/pSTV28-wzc and CM8/pSTV28-bglA) and empty-vector strains (CM22/pSTV28, CR5/pSTV28, ZM10/pSTV28 and CM8/pSTV28). Phage SCNJ-Z or SCNJ-C ( ~ 1010 PFU/ml) was serially diluted for the spot test.

CPS serves as the adsorption receptor of K. pneumoniae phages during phage infection, and mutations in genes responsible for the synthesis of CPS are a frequent cause of phage resistance14. In our screen, the overwhelming majority (36/37, 97.3%) of phage-resistant isolates possessed at least one mutation in a gene related to the CPS biosynthesis pathway. Mutations in the wcaJ gene (encoding a glycosyltransferase) of the cps operon were most frequently detected (21/37), including missense mutation (such as ZM9, and ZM11), nonsense mutation (CM9), deletion mutation (ZM6), frameshift mutation (CM1, and ZM5), and interruption by the insertion of IS5 at different nucleotide positions (such as ZM1, and ZM12). All these wcaJ mutants displayed ‘nmsd’ morphology (Supplementary Fig. 5). Adsorption experiments showed significantly impaired adsorption for them after incubation with the corresponding phage (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1), suggesting loss of capsule.

Mutations in the wzc gene (encoding a tyrosine-protein kinase) of the cps operon were detected in 9 resistant isolates, including missense mutation (CR5, CM19, CM22, and ZM10), frameshift mutation (CM13, and CM17), and insertion mutation by IS5 (CM3, and CM10) or ISKox3 (ZR2). For these wzc mutants, most of them were also ‘nmsd’ colonies (Supplementary Fig. 5), and phage adsorption to them was significantly reduced when compared to that of parental SCNJ1 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1). While, CR5 and ZM10, which had an amino acid substitution at position 561 (Y561D) and 640 (P640S) of Wzc, respectively, showed ‘msbw’ morphology similar to SCNJ1 (Fig. 2a). The phage adsorption to CR5 was only ~10% less than that to SCNJ1 (CR5 vs. SCNJ1, 88.64 ± 1.00 vs. 99.70 ± 0.13, p = 0.3860, Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 1). By contrast, phage adsorption to ZM10 was 10.55 ± 7.92, which was dramatically reduced when compared to SCNJ1 (p < 0.0001, Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1). To examine whether the point mutations of wzc in CR5, ZM10, and CM22 (WzcI649F, low adsorption, as a control) cause these phenotype changes, we cloned the wild-type wzc from SCNJ1 into CR5, ZM10, and CM22, respectively. Spot tests showed that the complemented strains CM22/pSTV28-wzc, CR5/pSTV28-wzc, and ZM10/pSTV28-wzc became susceptive to phage as expected (Fig. 3c).

The remaining mutations related to the CPS biosynthesis pathway include an insertion of IS5 or ISKox3 in (or upstream of) wzi or ctg_01605 in the cps operon (CR3, ZR7, CM20, and ZM7). Besides, a 23,516-bp deletion was present in ZR9, and the deleted fragment contained some genes of the cps operon (wcaI-wcaJ-gnd-manC-manC-ugd). In addition to those mutations in the cps operon, a single missense mutation in rfaH, which encodes a transcription antiterminator required for CPS production was identified in CR720. These mutants generally displayed ‘nmsd’ appearance, and phage adsorption to them was significantly impaired (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting reduced CPS production. Moreover, the cps mutations, especially those from in vivo samples frequently co-occurred with another mutation in genes such as rcsA (encoding an auxiliary protein of the Rcs phosphorelay system)25, scrY (encoding a sucrose porin26), lapB (encoding a heat shock protein involved in the assembly of LPS27), nuoC (encoding a quinone oxidoreductase in the respiratory chain of mitochondria28), or lepB (encoding a leader peptidase I29, the mutation in CR2). Whether these proteins are involved in phage resistance development warrants further explorations.

Especially, strain CM8, which had an amino acid substitution at position 387 (D to N) of BglA (a 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase30), was the only resistant clone that did not carry any genetic mutation related to CPS biosynthesis. It had a similar colony morphology and undifferentiated adsorption rate to that of SCNJ1 (p = 0.9849, Fig. 2a and Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 1). Complementation of the wild-type bglA successfully restored the phage sensitivity of CM8 (Fig. 3c), indicating a substantial role of bglA in conferring phage resistance in K. pneumoniae.

Phage resistance is not solely caused by capsule deficiency

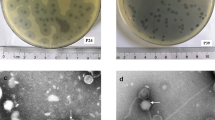

Based on the phenotypic and genetic characterization of phage-resistance mutants described above, we selected CR5 (WzcY561D, ‘msbw’ colony, high adsorption), ZM10 (WzcP640S, ‘msbw’ colony, low adsorption), CM22 (WzcI649F, ‘nmsd’ colony, low adsorption) and CM8 (BglAD387N, ‘msbw’ colony, low adsorption) for further vetting. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showed that CM22 was nonencapsulated, while CR5, ZM10, and CM8 included a capsule on the surface, like the parental SCNJ1 (Fig. 4a). Uronic acid quantification showed that the abundance of CPS was significantly reduced in CM22 (CM22 vs. SCNJ1, 12.57 ± 1.28 vs. 55.73 ± 9.84 μg/109 CFU, p < 0.0001), while that of CR5, ZM10, and CM8 were comparable to SCNJ1 (57.24 ± 2.83, 49.86 ± 4.86, 47.53 ± 8.25 vs. 55.73 ± 9.84 μg/109 CFU, p = 0.9943, 0.6277 and 0.3659, respectively) (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that loss/modification of the capsule has contributed to phage resistance, whereas, other undefined mechanisms are also involved in the phage resistance evolution.

a Electron microscope image of SCNJ1, and its mutants CR5, CM8, ZM10, and CM22. One representative image from three images obtained from one section is shown. b Capsule production was measured by uronic acid content and normalized to 109 CFU bacteria. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test [F (4, 10) = 25.48, p < 0.0001].

Phage-resistant mutants showed varying resistance to serum and phagocytosis

Biofilm formation is an important factor in mediating colonization, a first and requisite step in the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae3. In this study, we measured and compared the biofilm biomass of phage-resistant mutants with that of its parental strain SCNJ1 at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h. ZM10 displayed significantly decreased biofilm phenotype compared with SCNJ1 at all three-time points (ZM10 vs. SCNJ10.27 ± 0.11 vs. 0.37 ± 0.10 at 12 h, 0.40 ± 0.14 vs. 0.83 ± 0.12 at 24 h, and 0.36 ± 0.13 vs. 0.54 ± 0.13 at 48 h, p = 0.0525, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.0006, respectively) (Fig. 5a). The biofilm biomass of CR5 was also significantly lower than SCNJ1 at 24 h and 48 h (0.45 ± 0.08, and 0.27 ± 0.06, respectively, both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5a). CM22 showed significantly decreased biofilm formation at 24 h (0.62 ± 0.18, p < 0.0001), while no significant difference from SCNJ1 was observed at 48 h (p = 0.1073, Fig. 5a), suggesting a slower biofilm dispersion rate of CM22. These results indicate that different mutations in wzc have different effects on bacterial biofilm formation. CM8 produced comparable levels of biofilms as the wild-type SCNJ1 did at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, indicating a dispensable role of bglA in biofilm formation.

a Biofilm formation of SCNJ1 and representative strains of phage-resistant mutants CM8, CR5, ZM10, and CM22 in a 96-well polystyrene plate at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, measured by OD595nm after crystal-violet staining. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA, accompanied by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test [Interaction: F (8, 146) = 12.94, p < 0.0001; Row Factor: F (2, 146) = 102.8, p < 0.0001; Column Factor: F (4, 146) = 46.62, p < 0.0001]. b Time-dependent bactericidal effect of 75% normal human serum for 3 h at 37 °C. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test [Interaction: F (12, 40) = 9.362, p < 0.0001; Row Factor: F (3, 40) = 80.88, p < 0.0001; Column Factor: F (4, 40) = 34.24, p < 0.0001]. c In vivo phagocytosis assays. BALB/c mice (n = 6 for each strain) were infected intranasally with a dose of 1 × 108 CFU/mouse of SCNJ1 or phage-resistant mutants CM8, CR5, ZM10, or CM22. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed at 90 min after inoculation before the number of bacteria engulfed by alveolar macrophages was counted. The changes of phage-resistant mutants in phagocytosis were normalized to the parental SCNJ1, which was set to the baseline value of 1. Each symbol represents 1 animal and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test [F (4, 21) = 38.28, p < 0.0001].

We then evaluated the bacterial survival ability of phage-resistance mutants under 75% serum exposure. Over a 3-h incubation period, ~ 99.9% of CM22 was killed, while the wild-type SCNJ1 could withstand the serum killing and even propagate in it, from 105 CFU/ml at 0 h to 107 CFU/ml at 3 h (Fig. 5b). ZM10 also survived in the serum but exhibited significantly lower growth ability compared to that of SCNJ1 at 2 and 3 h (p = 0.1389, and p = 0.0089, respectively). Conversely, CR5 and CM8 showed increased resistance to serum, with viable counts increased at 1 h in serum and a significantly higher number of viable bacteria in the next two hours than SCNJ1 (p = 0.0020 and p = 0.0070, respectively, Fig. 5b). These results indicate that the mutations in CR5 (WzcY561D) and CM8 (BglAD387N) have promoted bacterial resistance to serum killing, while mutations in CM22 (WzcI649F) and ZM10 (WzcP640S) make the bacteria more vulnerable in the serum.

To explore the ability of phage-resistance mutants to resist early immune clearance in vivo, we intranasally inoculated BALB/c mice (n = 6 for each strain) with 1 × 108 CFU of SCNJ1 or mutants and counted the bacteria engulfed by alveolar macrophages obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. We found that CM22 were phagocytosed 1.86 ± 0.24 fold more efficiently than the wild-type SCNJ1 (Fig. 5c), indicating that CM22 had dramatically decreased resistance to phagocytosis (p < 0.0001 vs. SCNJ1). In contrast, significantly lower number of CR5, ZM10, and CM8 were engulfed by macrophages when compared to SCNJ1 (p = 0.0011, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.0076, respectively), suggesting that mutations in CR5 (WzcY561D), ZM10 (WzcP640S), and CM8 (BglAD387N) helped to resist phagocytosis in the lung (Fig. 5c).

Attenuated virulence of phage-resistant strains in mice, except for CM8 (BglAD387N)

As a fitness trade-off, phage-resistance mutation may lead to changes in the bacterial virulence in the host. To compare the virulence between the phage-resistant mutants and wild-type SCNJ1, we intranasally inoculated BALB/c mice with 2 × 107 CFU of SCNJ1 or mutants and monitored the survival of them for 7 days. As shown in Fig. 6a, mice infected by the wild-type SCNJ1 were all dead within 48 h, whereas those infected with ZM10 or CM22 all survived over 7 days (Fig. 6a), suggesting that ZM10 and CM22 had significantly reduced virulence (both p < 0.0001 vs. SCNJ1, respectively). CR5-infected mice had 30% mortality at 48 h, 80% by day 4, and all died by day 6 after infection (Fig. 6a), revealing the partially but significantly attenuated virulence of CR5 mutant (p = 0.0014 vs. SCNJ1). These results illustrate the indispensable role of wzc in contributing to the virulence of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae. In contrast, mice challenged with CM8 behaved similarly to those infected by wild-type SCNJ1 and also experienced 100% mortality at 48 h, indicating that mutation in CM8 (BglAD387N) had little impact on its virulence.

a Survival of BALB/c mice (n = 10 for each strain) intranasally inoculated with 2 × 107 CFU of SCNJ1 or its mutant CM8, CR5, ZM10, or CM22. An in extremis state or death was monitored for 7 days. The survival of mice challenged with CR5, ZM10, and CM22 was significantly increased compared to that of mice challenged with SCNJ1 (p < 0.01, p < 0.0001, and p < 0.0001, respectively, as determined by a log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). b Bacterial loads in the liver, lungs, and spleen of mice (n = 5 for each strain) at 48 h after intranasally infected with 1 × 106 CFU of SCNJ1 or its mutants. The liver, lungs, and spleen of mice were carefully aseptically homogenized and serially diluted for bacterial enumeration. Each symbol represents 1 animal and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. For bacterial loads in the liver and spleen, the data was transformed with the formula: Y = Ln (X + 1) before one-way ANOVA analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test [Lung: F (4, 16) = 13.46, p < 0.0001; Liver: F (4, 16) = 97.91, p < 0.0001; Spleen: F (4, 16) = 271.3, p < 0.0001]. c Histological images of hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained lung tissues at 48 h after infection with 1 × 106 CFU of SCNJ1, its mutant or PBS (negative control). The figures are representative of three sections in three mice that showed similar pathology in the tissues. Areas of increased magnification were shown in the below panels (scale bars, 50 µm).

Phage-resistant mutants showed significantly declined colonization, dissemination, and pathogenicity in mice, except for CM8 (BglAD387N)

Next, we assessed the ability to survive and colonize phage-resistant mutants and their pathogenicity in mice. BALB/c mice (n = 5 for each strain) were intranasally infected with 1×106 CFU of SCNJ1 or mutants, and their organs (lung, liver, and spleen) were harvested and bacterial titers quantified at 48 h after infection. As a result, the wild-type SCNJ1 yielded significantly higher bacterial loads than CR5, ZM10, and CM22 in the lung, liver, and spleen, respectively (all, p < 0.0001, Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 2), indicating that mutations in wzc in CR5, ZM10, and CM22 had substantially reduced bacterial colonization ability in mice. CM8 had lower bacterial titer than SCNJ1 in the lung (p = 0.0007), but the number of bacteria recovered was maintained at a high level (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 2). Besides, mice infected with CM8 had approximately 0.16- and 1.02-fold bacterial titers in their livers (p = 0.0952) and spleens (p = 0.9905), respectively, compared to those infected with SCNJ1 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 2). These data suggest that CM8 (BglAD387N) maintained a strong ability to colonize and disseminate in mice.

To gain insight into host response to bacterial infection, histopathological analysis was performed on murine lungs prepared 48 h after infection with 1 × 106 CFU of SCNJ1 or its mutant. Compared to the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, negative control) group, the lung tissues of mice infected by SCNJ1 were damaged and filled with a large number of red blood cells, accompanied by a significant exudate. The infection of CM8 caused extensive infiltration of inflammation cells and evident hemorrhage in the lung tissues. In contrast, CR5-infected lungs exhibited only sporadic areas of inflammation, and the mice treated with ZM10 and CM22 strains did not show obvious pathological changes. These findings support that the mutations in wzc in CR5, ZM10, and CM22 were dramatically attenuated in the virulence of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae, while bglA mutation makes little difference.

Phage treatment rescues CM8-infected mice

Mouse infection models above demonstrated that CM8 had full virulence and comparable in vivo fitness to its wild-type SCNJ1. To rescue CM8-infected mice, we employed the lytic phage vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y capable of lysing CM8 in vitro assay (Fig. 1d). BALB/c mice (n = 10 for each group) were intranasally infected with 1 × 107 CFU of CM8 and then intranasally inoculated with phage vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y [1 × 108 PFU/mouse, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10], or with PBS (as a negative control) 1.5 h after bacterial infection. Mice in the PBS-treated group showed an 80% survival rate at 48 h, while 0% by day 3 (Fig. 7). Conversely, all mice that received phage treatment survived and no death was observed over the 7 days (p < 0.0001 vs PBS treatment group). All the surviving mice, except two, had either substantially cleared or only had a small number of CM8. There was no significant difference in survival between the safe test and PBS control groups (Fig. 7). Collectively, these results reveal the therapeutic potential of vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y against fully virulent phage-resistant mutants like CM8 (BglAD387N).

vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y is an additional phage isolated on the host strain SCNJ1 which can effectively lyse CM8 in vitro. The therapeutic potential of vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y in treating CM8-infected mice was investigated by the pneumonia model. Survival of mice (n = 10 for each group) infected intranasally with CM8 (1 × 107 CFU) followed by treatment with phage (MOI, 10) 1.5 h later. An equivalent volume of PBS was treated as a control. Equivalent volumes of sterile PBS were injected instead of bacteria for a safe test group. p < 0.0001 (phage treatment group versus the PBS treatment group) using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Discussion

In this study, we constructed an evolutionary scenario for a K54 hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strain SCNJ1, wherein it was selected by two distinct phages during in vitro culture and in vivo pneumoniae treatment. A comprehensive analysis of resistant populations was carried out, aiming to address the genetic basis of bacterial resistance to phages and how those genetic changes affect their fitness and virulence phenotypes.

Previous studies have shown that modifications of the polysaccharide exposed on the cell surface are the major strategy for developing phage resistance in K. pneumoniae13,14,17. In our work, most of the resistance development was accompanied by a smaller colony and impaired adsorption as a result of capsule deficiency. Importantly, this resistance phenotype was favored under planktonic coculture and also in a murine context. Genomic-based analysis reinforced that the mutations in genes required for CPS biosynthesis and those in wcaJ and wzc constitute the most common genetic basis for the resistance phenotype. Importantly, mutations in wcaJ were found at high frequency under both conditions, revealing wcaJ as a hotspot, despite that the mutation types of wcaJ from in vivo samples are diverse whereas in vitro wcaJ mutations are all IS5 insertion mutations. In contrast, mutations in wzc exhibited more association with in vivo samples. Besides, we noticed that all the in vivo resistant mutants had a synonymous mutation in glycerol kinase gene glpK and that these in vivo cps mutations frequently co-occurred with other distinct gene mutations in addition to glpK. These results are indicative of combined selection pressure by phages and the immune system. Despite the minor differences in the mutation pattern between the in vivo and in vitro samples, mutations in the CPS genes were predominant among the phage-resistant mutants under both conditions, implying the possibility of predicting phage resistance evolution during phage treatment through in vitro assays.

Genetic investigation showed that CM22, CR5, and ZM10 all had a single missense mutation in wzc, leading to amino acid substitution of WzcI649F, WzcY561D, and WzcP640S, respectively. Wzc is the master regulator for both polymerization and translocation of CPS31. Genetic mutations in the wzc gene were frequently identified in phage-resistant mutant isolates, and these changes generally cause reduced CPS production, like WzcI649F in our case14,21,22. However, WzcP640S produced a similar capsule level to the wild-type SCNJ1 but a sharply reduced adsorption, raising the possibility that qualitative alterations (for example, by selection for mucoviscosity) on the cell surface may have prevented capsule-targeting phage access to specific receptors22. This speculation was supported by the fact that WzcP640S displayed markedly higher mucoviscosity than SCNJ1 did (Supplementary Fig. 6). Unlike WzcP640S, WzcY561D produced similar quantities of CPS with SCNJ1, and they had no significant difference in phage adsorption rates compared to SCNJ1. This implies that the phage-specific receptor was intact; meanwhile, phage can access its adsorption receptor in WzcY561D. So, why phage can be adsorbed but not establish a productive infection? For WzcY561D, the mutated Wzc may alter the structure of the capsule so that it is adsorbable but not degraded by the phage, ultimately rendering the phage unable to irreversibly bind to its secondary receptor32.

In this study, we found that WzcI649F, the one with the capsule defective, showed compromised resistance to serum killing and was vulnerable to macrophage phagocytosis. As expected, the virulence of WzcI649F was significantly attenuated in the mouse infection model and was easily cleared by the immune system, which is consistent with the well-established model that the emerged phage resistance is prone to sensitize bacteria to the host immune system17,20,33. Whereas, WzcY561D and WzcP640S enhanced resistance to phagocytosis, which could be explained by the mechanism that Hmv blocks adherence and internalization by macrophages34,35, as CR5 (WzcY561D), and ZM10 (WzcP640S) displayed higher Hmv levels than the wild-type SCNJ1 did. Fortunately, despite their ability to resist phagocytosis, WzcY561D and WzcP640S were also less virulent in mice and showed reduced colonization and pathogenicity. It is likely that CR5 (WzcY561D) and ZM10 (WzcP640S) had failed to overcome the stresses imposed by the host, such as the reactive oxygen species produced by effector cells of the innate immune system and the limited-iron condition36,37. These results indicate that different mutations in wzc gene mediate phage resistance through different mechanisms and that the changes in the capsule, no matter quantitative or qualitative, play a dominant role in the phage resistance development of K. pneumoniae.

CM8 (BglAD387N), an in vivo phage-resistant clone, gets special attention in our work, as it had a similar amount of CPS and phage adsorption rate to SCNJ1. A single missense mutation in the 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase-encoding gene bglA, resulting in a substitution of an amino acid (D387N) conferred phage resistance in this mutant. The mutated BglA may have an impact on the production of secondary receptors, such as lipopolysaccharide, which resulted in the failure of phage infection. Notably, CM8 (BglAD387N) exhibited enhanced resistance to phagocytosis and retained virulence in mice, compared with the general impaired bacterial fitness and virulence in CPS-related mutants as revealed in this study and previous studies17,20,21. The inconsistent trade-offs between phage resistance and bacterial fitness have also been reported in some other bacterial pathogens. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14, LPS mutants became attenuated while CRISPR-resistant mutants remained virulent38. In K15 Escherichia coli, capsule mutants retained virulence while LPS mutants showed significant attenuation39. These fully virulent phage-resistant mutants are unfavorable for the treatment of any corresponding infections and can ultimately influence the severity of the disease. Future work will be crucial to understanding the leading drivers of the evolution of fully virulent phage-resistant clones.

The application of lytic phages to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae in animal models has been documented in previous studies18,40,41. Using an established mouse model of pneumoniae, we demonstrate that phage vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y improved survival outcomes and reduced bacterial burdens in CM8-infected mice. However, we also observed the emergence of phage-resistant mutants during this treatment. To overcome the problem of phage resistance, a comprehensive understanding of the phage-bacteria interactions and the mechanisms driving phage resistance in the bacterial hosts is required. These findings collectively support the idea that phage therapy can moderate the severity of infections by K. pneumoniae, while the synergy of suitable antibiotics, or phages utilizing alternative receptors is needed for the effective treatment of K. pneumoniae infections.

We are aware of the limitations of the current study. First, we primarily hoped to identify different phage resistance patterns under in vitro versus in vivo conditions, while no substantial difference was found. A larger number of independent bacterial cultures followed by pool-sequencing would be expected to reveal specific resistance patterns, if there exists one. Second, two different phages were used for studying phage resistance development. However, they both target the capsular polysaccharide receptor of K. pneumoniae, which may lead to a relatively low diversity of resistance pathways. Third, the present study examined the genetic changes imposed by phage resistance evolution and highlighted the close link between capsule biosynthesis and resistance. However, substantial work remains to be done to figure out how the mutation in bglA (in CM8) conferred phage resistance but also retained its full virulence, and why the mutations in wzc (in CR5, ZM10, and CM22) resulted in distinct phenotypic characteristics.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that CPS mutation is the major strategy involved in phage-borne resistance in hvKp SCNJ1. The BglAD387N mutation does not carry an adaptive trade-off effect and represents a novel phage resistance mechanism in hvKp. To maximize the efficacy of clinical phage therapy, further systematic characterization of phage resistance evolution under different conditions with different phages is needed.

Methods

Bacterial strains and bacteriophages

K. pneumoniae strain SCNJ1 (5,474,953 bp, 57.29% GC) is an ST29-K54 serotype carbapenem-resistant hvKp that was recovered from the sputum of a patient in Sichuan Province in November 201842. Genomic analysis revealed that no CRISPR-Cas, DISARM, or BREX system was detected in the SCNJ1 genome (Supplementary Method). Unless specified otherwise, all bacterial strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) or LB agar and cultivated at 37 °C.

Two lytic phages, the podovirus vB_KpnA_SCNJ1-Z (for brevity, referred to here as SCNJ1-Z), and siphovirus vB_KpnS_SCNJ1-C (referred to here as SCNJ1-C), which both formed circular translucent plaques against SCNJ1, were isolated and characterized in our previous study43. SCNJ1-Z and SCNJ1-C are double-stranded DNA genomes with sizes of 43,428 bp [57 putative open reading frames (ORFs)] and 46,039 bp (83 putative ORFs), respectively. SCNJ1-Z and SCNJ1-C had relatively short latency periods (9 min, and 7 min, respectively), with a burst size of 9.06 ± 0.81 PFU/cell, 6.25 ± 1.58 PFU/cell, respectively. The vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y phage is an additional phage isolated on the same host strain SCNJ143. It has a DNA genome size of 50,360 bp (80 putative ORFs) and it is a member of the myovirus family, with an icosahedral head and a sheathed contractile tail by microscopic examination. vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y exhibited high lytic activity, with a latency period of 7 min and a burst size of 13.26 ± 2.53 PFU/cell. Capsule may serve as the receptor by the three phages, as at least one putative depolymerase gene was detected in each phage43.

Phages were amplified using the host strain SCNJ1 and purified by centrifugation and filtration (0.22 µm). The resulting stock solution, with a concentration of ~1 × 1010 PFU/mL was diluted in PBS.

Selection of phage-resistant mutants

In vitro

SCNJ1 from overnight cultures were inoculated into fresh LB at a rate of 1:100 and grown to log phase [the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) ~ 0.6–0.8] at 37 °C with shaking. 1 ml of bacterial culture [~5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)] and 10 μl of phages [~1 × 107 plaque forming unit (PFU) of SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C] were mixed at an MOI of 0.02, and the suspension was incubated at 37 °C with aeration for 12 h. The cultures were then plated on LB agar plates to produce individual colonies. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

In vivo

Animal experiments were approved by the Southwest Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and we have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Female Kunming mice aged 3 to 5 weeks were obtained from the Animal Center Laboratory of Southwest Medical University. After being lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, nine mice (three mice per group) were intranasally infected with 50 µl (~ 1 × 106 CFU per mouse) of the SCNJ1 strain. Two hours after infection, 50 µl of phages (SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C, at an MOI of 100) or PBS were intranasally incubated in the infected mice. 12 h later, mice were euthanized and a laparotomy was carried out to obtain the lung. The lungs were homogenized in 1 ml PBS by a high-speed low-temperature tissue homogenizer (Wuhan Servicebio Tech, China). The suspension was diluted in PBS and plated on LB agar plates.

After overnight incubation at 37 °C, 20 colonies from each animal or plate from the in vitro experiment were randomly picked, yielding a total of 60 colonies for determination of phage susceptibility by inverted spotting plate assays after purifying on LB agar by two rounds of subculture. After that, 9 or 10 phage-resistant isolates against SCNJ-C or SCNJ-Z selected by different colony morphology and size were further confirmed by EOP experiments and growth kinetic assays. The verified phage-resistant isolates against SCNJ-C that emerged in culture medium and mice were named CR (n = 9), and CM (n = 10), respectively. Those resistant isolates against SCNJ-Z in culture medium and mice were named ZR (n = 9), and ZM (n = 9), respectively.

Spot test

100 μl of the log-phase phage-resistant isolate was spread on an LB agar plate, and 5 μl of high-titer phage stocks (109–1010 PFU/ml) were dropped onto the agar overlaid by the bacterial strain17. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the presence/absence of a plaque was regarded as phage sensitivity/resistance.

Inverted spotting assay

1 ml of a sterile-filtered phage stock (109–1010 PFU/ml) and 1 ml molten LB-top agar were gently mixed and distributed onto LB agar plates. After agar solidification and drying, 5 µl of log-phase bacterial culture of the phage-resistant mutant was dropped onto the agar and incubated at 37 °C for 10–12 h44. The presence/absence of a bacterial lawn was regarded as phage sensitivity/resistance.

EOP analysis

10 µl of sterile-filtered phage stock (103 PFU, SCNJ1-Z, or SCNJ1-C) was mixed with 1 ml overnight bacterial culture of SCNJ1 (~ 1×109 CFU) or phage-resistant mutants, respectively. After 10 min, 1 ml infected bacterial culture was mixed with 1 ml low melting point agarose solution before pouring on an LB agar plate and incubating at 37 °C. After 12 to 14 h, the plates were inspected for plaques, and the presence of a lysis plaque was recorded as the strain was susceptible to the tested phage45. EOP value was calculated by dividing the average number of plaques on phage-resistant mutants by that on the parental strain SCNJ1. The experiment was repeated at least three times in triplicate.

Growth kinetics assay

For growth kinetics assay in LB broth without phage pressure, 200 µl of bacterial cultures with the starting OD600 of ~0.1 (~ 1 × 108 CFU), were grown in a flat-bottomed 96-well microplate (Corning, United States). For growth kinetics assay under phage pressure, 100 µl of bacterial culture at an OD600 of 0.2 (~ 2 × 108 CFU) was mixed with 100 µl phages at an MOI of 0.0001. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h with a shaking cycle every 60 min when OD600 was measured by a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy H1). These experiments were independently performed three times in triplicate.

String test and mucoviscosity assay

The hypermucoviscous phenotype was confirmed by the string test and the sedimentation assay. For the string test, bacteria were grown on LB agar plates containing 5% sheep blood and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The string test was confirmed positive when a viscous string longer than 5 mm could be generated by touching and pulling a single colony upwards with a standard inoculation loop25. For the sedimentation assay, overnight bacterial culture was adjusted to an OD600 = 1.0 in a final volume of 1 ml PBS. The suspension was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min, and the OD600 of the supernatant was measured by a microplate reader34. Results were expressed as a ratio of the supernatant OD600 to that in the input culture.

Phage adsorption assay

1 ml of overnight bacterial cultures (SCNJ1 or phage-resistant mutant) or 1 ml of sterile PBS (as a control) and 10 µL of sterile-filtered phages (SCNJ1-Z or SCNJ1-C) were mixed at an MOI of 0.0001. The suspension was incubated at 37 °C and shaken at 220 rpm for 10 min with aeration and immediately centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant containing free phages was serially diluted, and mixed with the bacterial culture of SCNJ1 at a 1:1 v/v ratio, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 10 min. The incubated suspension and molten LB-top agar were gently mixed (1:1 v/v ratio) and distributed onto LB-agar plates. After solidification, the plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight20. Non-adsorbed phage was quantified by the double-layer agar method and recorded in PFU/ml. The efficiency of adsorption = [1 − (the phage titers of strains/the phage titers of PBS)] × 100%.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the SCNJ1, or phage-resistant mutants was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar as recommended by CLSI guidelines46. The log-phase bacterial culture was adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland (~ 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) and plated on the Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Zone diameters were determined following incubation with antibiotic disks at 37 °C for 16–18 h. The results were interpreted according to the CLSI guidelines. The tested antibiotics were aztreonam (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 μg), tetracycline (30 µg), tigecycline (15 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), amikacin (30 μg), ceftazidime, cefoxitin (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ampicillin-sulbactam (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (36 μg), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25 μg). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control.

Bacterial genome sequencing and analysis

The genomic DNA of the phage-resistant mutant was extracted using a Bacterial Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified DNA was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) with the 150-bp paired-end approach by the Tsingke Biotech (Beijing, China). Raw data were filtered by fastp47 (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) and the resulting clean reads were aligned to the SCNJ1 reference genome by using Breseq version 0.39.048 (https://barricklab.org/twiki/bin/view/Lab/ToolsBacterialGenomeResequencing) with the code ‘breseq -r SCNJ1chromosome.gbk -r pVir-SCNJ1.gbk -r pNDM5-SCNJ1.gbk -o sample filtered.sample_1.fq.gz filtered.sample_2.fq.gz’. Mutations detected were subsequently manually reviewed.

Cloning and complementation experiments

The genomic DNA of SCNJ1 was used as the template for the amplification of mutated genes using primers in Supplementary Table 3. The pSTV28-kan vector was linearized by PCR amplification using primes pSTV28-kan-F/R. The PCR amplicons of mutated genes were cloned into the pSTV-28-kan vector by homologous recombination using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and transformed competent E. coli DH5α cells via heat shock. The resulting recombinant plasmids were electroporated into corresponding phage-resistant mutants and the transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Individual colonies were picked and cultured, and faithful ligation was confirmed by PCR using primers kan-F/R and subsequent Sanger sequencing.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using an HT7800 (HITACHI, Japan) by Scientist Biotechnology (Sichuan, China). The samples were fixed for at least 2 h at room temperature in 3% glutaraldehyde, then pre-embedded with 1% agarose solution and fixed with 1% osmium acid prepared with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature in the dark for 2 h. The prepared samples were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in alcohol grades, incubated with propylene oxide, and infiltrated overnight with a 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and low-viscosity epoxy resin49. The following day, samples were embedded in epoxy resin and polymerized. Ultrathin sections (approximately 60–80 nm) were cut on a Leica UC7 microtome, transferred to copper grids stained with lead citrate, and examined and imaged using an HT7800 TEM.

CPS quantification

Uronic acids were quantified to assess capsule production18. 500 µl of overnight bacterial cultures adjusted to an OD600 of 1.0 (~ 2.5 × 109 CFU) were mixed with 100 µl of 1% zwittergent 3–14 detergent in 100 mM citric acid buffer (pH = 2.0). The samples were incubated at 50 °C for 20 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the capsule polysaccharide was precipitated with absolute ethanol at 4 °C overnight. The following day, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. After the pellets were dried completely, 200 µl of ddH2O was added to dissolve them. To hydrolyze capsule polysaccharide, 1.2 ml of sodium tetraborate-sulfuric acid solution (12.5 mM sodium tetraborate was dissolved in 100 mL H2SO4) was added to the samples, mixed, and boiled at 100 °C for 5 min. After cooling in ice water to room temperature, 20 µl of 10% 3-hydroxy diphenol in 0.5% NaOH solution was added to the samples, followed by shaking for 5 min. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm using the microplate reader. A standard curve of uronic acid was established to quantify the CPS content. The experiment was independently performed three times in triplicate.

Biofilm formation assay

Biofilm formation was determined using crystal-violet staining on a 96-well microtiter plate50. The log-phase bacterial culture was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1, diluted 1:100 in LB medium, and incubated statically in sterile 96-well microtiter plates (200 µl/well). The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, respectively. At each time point, the wells were washed five times with ddH2O and dried. Cultures were fixed for 15 min after 200 µl of methanol was added to each well. After that, methanol was removed, and the biofilm was stained with 200 µl of 0.1% crystal-violet for 15 min. Then, crystal violet was removed and the wells were washed three times with ddH2O. After the wells were dried, stained biofilms were resuspended in 200 µl of 33% glacial acetic acid. Five minutes later, the absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader. The experiment was repeated at least three times in triplicate.

Serum bactericidal assay

4 × 106 CFU of log-phase bacteria were suspended in PBS and mixed at a 1:3 v/v ratio with normal human serum from healthy volunteers in a final volume of 400 µl. The mixture was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. At 0, 1, 2, and 3 h, 100 μl aliquots were retrieved, diluted, and plated on LB agar plates for colony counting. The percentage of survival was determined as the number of bacteria that survived relative to the initial bacterial loading33. The experiment was repeated at least three times in triplicate.

Mouse experiments

Animal experiments were approved by the Southwest Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and we have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks were obtained from Jiangsu Huachuang sino Pharma Tech (Jiangsu, China). Before and following inoculation, mice had unlimited access to food and water.

Survival assay

Ten mice were selected randomly for each group. After being lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, mice were intranasally infected with the strain being evaluated (SCNJ1, CR5, ZM10, CM8, or CM22) by placing 50 µl bacterial suspension in PBS (~ 2×107 CFU) on the nares51. As a control, three mice were intranasally inoculated with 50 µl sterile PBS. Mice were monitored for 7 days at 24-hour intervals, with an in extremis state or death being used as the study endpoint.

In vivo phagocytosis assay

Six mice were selected randomly for each group. After being lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, mice were intranasally infected with 50 µl (~ 1×108 CFU) of SCNJ1, CR5, ZM10, CM8, or CM22. As a control, three mice were inoculated with 50 µl sterile PBS intranasally. At 90 min after inoculation, mouse lungs were lavaged using 3 ml PBS to collect the alveolar phagocytes, and the suspension was treated with 100 µg/ml gentamicin at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, the cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 5 min, and washed with PBS two times before resuspended in 500 µl PBS. The phagocytes were lysed using 1% Triton X-100, and vortexed for 15 s52. After serial dilution, the suspension was plated for colony counting.

Organ burden assays

After being lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, five mice were intranasally infected with 50 µl (~ 1 × 106 CFU) of SCNJ1, CR5, ZM10, CM8, or CM22. As a control, three mice were inoculated with 50 µl sterile PBS. After 48 h, mouse organs (spleen, liver, and lung) were harvested, weighed, and homogenized in sterile PBS by high-speed low-temperature tissue homogenizer52. The homogenates were serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates for colony counting. The number of CFU determined in the organs was standardized per 1 g wet organ weight.

Histopathology

For histologic analysis (3 mice per group), mice were intranasally infected with ~1 × 106 CFU of SCNJ1, CR5, ZM10, CM8, or CM22. After 48 h, the lungs of mice were removed, washed in PBS, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. Embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm and dried before staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were obtained using an Olympus BX43 microscope and a Sony E3ISPM20000KPA camera. Figures were created using ImageView 4.11.22149.

Phage treatment

After being lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, twenty mice (ten mice per group) were intranasally inoculated with 50 µl (1 × 107 CFU) CM8. One hour after bacterial infection, the treatment group was intranasally inoculated with 50 µl (~ 1 × 108) of sterile-filtered phage stock of vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y at an MOI 1015. The untreated group was intranasally inoculated with 50 µl sterile PBS. Mice in the control group and safe test group were given 50 µl sterile PBS and then treated with either 50 µl of PBS or vB_KpnM_SCNJ1-Y (~ 1 × 108 PFU), respectively. Mice were monitored for 7 days at 24-h intervals, with an in extremis state or death being used as the study endpoint.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism 10.1.2, and data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). To assess the growth ability of SCNJ1 and the phage-resistant mutants, the area under the curve was calculated. The growth suppression was expressed as a percentage of the area under the growth curve of the control, corresponding to the suppression of the bacterial culture, calculated using the formula: [(Area of control – Area of phage treatment)/Area of control] × 100%. For the growth suppression assay, the area under the curve, phage adsorption efficiency, EOP analysis, capsule quantification, phagocytosis assay, and organ burden assays, statistical significances were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s post hoc test. Before statistical analysis of some data, IBM SPSS Statistic 27 software was employed for natural logarithm transformation or exponential function transformation. For the biofilm formation and serum resistance assays, statistical significances were evaluated using two-way ANOVA. The survival curves were analyzed via a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 were treated as the levels of statistical significance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Illumina raw reads of K. pneumoniae phage-resistant mutants are available in the NCBI SRA database under the bioproject PRJNA1190331. Other data are presented within the paper and supplemental material. The source data of this study are deposited in Open Science Framework with the link https://osf.io/csfuq/?view_only=f93d8fa85145490f9f382d11bd82635d.

References

Zhu, J., Wang, T., Chen, L. & Du, H. Virulence factors in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Micro. 12, 642484 (2021).

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327 (2018).

Russo, T. A. & Marr, C. M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 32, e00001–e00019 (2019).

Gu, D. et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 37–46 (2018).

Nick, J. A. et al. Host and pathogen response to bacteriophage engineered against Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. Cell 185, 1860–1874.e1812 (2022).

Petrovic Fabijan, A. et al. Safety of bacteriophage therapy in severe Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nat. Microbiol 5, 465–472 (2020).

Bao, J. et al. Non-active antibiotic and bacteriophage synergism to successfully treat recurrent urinary tract infection caused by extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 771–774 (2020).

Pirnay, J.-P. et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1434–1453 (2024).

Hatfull, G. F., Dedrick, R. M. & Schooley, R. T. Phage Therapy for Antibiotic-Resistant Bacterial Infections. Annu. Rev. Med. 73, 197–211 (2022).

Bertozzi Silva, J., Storms, Z., Sauvageau, D. & Millard, A. Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, fnw002 (2016).

Dunstan, R. A. et al. Epitopes in the capsular polysaccharide and the porin OmpK36 receptors are required for bacteriophage infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Rep. 42, 112551 (2023).

Hao, G. et al. O-antigen serves as a two-faced host factor for bacteriophage NJS1 infecting nonmucoid Klebsiella pneumoniae. Micro. Pathog. 155, 104897 (2021).

Lourenço, M. et al. Phages against Noncapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae: Broader Host range, Slower Resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 11, e0481222 (2023).

Hesse, S. et al. Phage resistance in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 evolves via diverse mutations that culminate in impaired adsorption. mBio 11, e02530–19 (2020).

Gordillo Altamirano, F. et al. Bacteriophage-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii are resensitized to antimicrobials. Nat. Microbiol 6, 157–161 (2021).

Tan, D. et al. A frameshift mutation in wcaj associated with phage resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microorganisms 8, 378 (2020).

Fang, Q., Feng, Y., McNally, A. & Zong, Z. Characterization of phage resistance and phages capable of intestinal decolonization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Commun. Biol. 5, 48 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Development of phage resistance in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with reduced virulence: a case report of a personalised phage therapy. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 29, 1601.e1601–1601.e1607 (2023).

Geng, H. et al. Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae to Phage hvKpP3 Due to High-Molecular Weight Lipopolysaccharide Synthesis Failure. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e04384–04322 (2023).

Tang, M. et al. Phage resistance formation and fitness costs of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae mediated by K2 capsule-specific phage and the corresponding mechanisms. Front Microbiol 14, 1156292 (2023).

Song, L. et al. Phage selective pressure reduces virulence of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae through mutation of the wzc gene. Front. Microbiol. 12, 1156292 (2021).

Majkowska-Skrobek, G. et al. The evolutionary trade-offs in phage-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae entail cross-phage sensitization and loss of multidrug resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 7723–7740 (2021).

Kortright, K. E., Chan, B. K., Koff, J. L. & Turner, P. E. Phage therapy: a renewed approach to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 25, 219–232 (2019).

Shen, X., Song, S., Li, C. & Zhang, J. Synonymous mutations in representative yeast genes are mostly strongly non-neutral. Nature 606, 725–731 (2022).

Walker, K. A. & Miller, V. L. The intersection of capsule gene expression, hypermucoviscosity and hypervirulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 54, 95–102 (2020).

Hardesty, C., Ferran, C. & DiRienzo, J. M. Plasmid-mediated sucrose metabolism in Escherichia coli: characterization of scrY, the structural gene for a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sucrose phosphotransferase system outer membrane porin. J. Bacteriol. 173, 449–456 (1991).

Klein, G., Kobylak, N., Lindner, B., Stupak, A. & Raina, S. Assembly of lipopolysaccharide in Escherichia coli requires the essential LapB heat shock protein. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 14829–14853 (2014).

Novakovsky, G. E., Dibrova, D. V. & Mulkidjanian, A. Y. Phylogenomic analysis of type 1 NADH:quinone oxidoreductase. Biochem. Biokhimiia 81, 770–784 (2016).

Musik, J. E. et al. New perspectives on Escherichia coli signal peptidase I substrate specificity: investigating why the TasA cleavage site is incompatible with LepB cleavage. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0500522 (2023).

Zangoui, P., Vashishtha, K. & Mahadevan, S. Evolution of aromatic β-glucoside utilization by successive mutational steps in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 197, 710–716 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. The molecular basis of regulation of bacterial capsule assembly by Wzc. Nat. Commun. 12, 4349 (2021).

Gordillo Altamirano, F. L. & Barr, J. J. Unlocking the next generation of phage therapy: the key is in the receptors. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 68, 115–123 (2021).

Kaszowska, M. et al. The mutation in wbaP cps gene cluster selected by phage-borne depolymerase abolishes capsule production and diminishes the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11562 (2021).

Mike, L. A. et al. A systematic analysis of hypermucoviscosity and capsule reveals distinct and overlapping genes that impact Klebsiella pneumoniae fitness. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009376 (2021).

Xu, Q., Yang, X., Chan, E. W. C. & Chen, S. The hypermucoviscosity of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae confers the ability to evade neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis. Virulence 12, 2050–2059 (2021).

Juttukonda, L. J. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii OxyR regulates the transcriptional response to hydrogen peroxide. Infect. Immun. 87, https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00413-18 (2019).

Raymond, K. N., Dertz, E. A. & Kim, S. S. Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3584–3588 (2003).

Alseth, E. O. et al. Bacterial biodiversity drives the evolution of CRISPR-based phage resistance. Nature 574, 549–552 (2019).

Gaborieau, B. et al. Variable fitness effects of bacteriophage resistance mutations in Escherichia coli: implications for phage therapy. J. Virol. 98, e01113–e01124 (2024).

Hesse, S. et al. Bacteriophage treatment rescues mice infected with multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258. mBio 12, e00034–21 (2021).

Martins, W. et al. Effective phage cocktail to combat the rising incidence of extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 16. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11, 1015–1023 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. bla NDM-5 carried by a hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae with sequence type 29. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8, 140 (2019).

Fang, C. et al. Isolation and characterization of three novel lytic phages against K54 serotype carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol 13, 1265011 (2023).

Gillis, A. & Mahillon, J. An improved method for rapid generation and screening of Bacillus thuringiensis phage-resistant mutants. J. Microbiol Methods 106, 101–103 (2014).

Kutter, E. Phage host range and efficiency of plating. Methods Mol. Biol. 501, 141–149 (2009).

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd edn. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2023).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Deatherage, D. E. & Barrick, J. E. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol. Biol. 1151, 165–188 (2014).

Ernst, C. M. et al. Adaptive evolution of virulence and persistence in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Med 26, 705–711 (2020).

Coffey, B. M. & Anderson, G. G. Biofilm formation in the 96-well microtiter plate. Methods Mol. Biol. 1149, 631–641 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. TolC2 is required for the resistance, colonization and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J. Med Microbiol 66, 1170–1176 (2017).

Tan, R. M. et al. Type IV pilus glycosylation mediates resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic activities of the pulmonary surfactant protein A. Infect. Immun. 83, 1339–1346 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900125, 82302576), a scientific and technological project in Sichuan Province (2022JDRC0144), and projects supported by the Joint Funds of the Luzhou and Southwest Medical University Natural Science Foundation (2024LZXNYDJ037 and 2024LZXNYDJ022). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.Z. and Y.L.; methodology and resources, Y.F., M.Y., L.C., and Y.J.L.; software, Y.F. and M.Y.; formal analysis, Y.L. and L.H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, L.H.Z. and Y.F.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and L.H.Z. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Tobias Goris and Laura Rodríguez Pérez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Y., Yin, M., Cao, L. et al. Capsule mutations serve as a key strategy of phage resistance evolution of K54 hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Commun Biol 8, 257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07687-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07687-8

This article is cited by

-

Characterization and genomics of phage Henu2_3 against K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae and its efficacy in animal models

AMB Express (2025)

-

Novel bacteriophages effectively target multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2025)

-

Predictors of mortality and progression from colonization to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bloodstream infection in hematologic disorders: a single-center retrospective study

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2025)