Abstract

Septic arthritis, primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, poses a significant risk of both mortality and morbidity due to its aggressive nature. The nuc1-encoded thermonuclease NucA of S. aureus degrades extracellular DNA/RNA, allowing the pathogen to escape neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and maintain the infection unabated. Here we show that in the mouse model for hematogenous septic arthritis, the Δnuc1 mutant is much less pathogenic and the severity of clinical septic arthritis is markedly reduced, including decreased weight loss, lower kidney bacterial load, reduced bone erosion, and much less IL-6 production. In vitro, S. aureus genomic DNA induces a robust TNF-α response in macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells abrogated when the DNA is degraded by NucA. Moreover, the wild type induces high levels of TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-6 in neutrophils and osteoblast-like SAOS-2 cells, respectively. NucA exacerbates septic arthritis by increasing extracellular and intracellular survival of bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Septic arthritis, the most aggressive joint disease carrying high mortality and morbidity risk, is predominantly caused by Staphylococcus aureus1. In half of the patients, even when they receive immediate treatment, the joint damage caused by septic arthritis is often irreversible, leading to permanent joint dysfunction2. It is known that innate immunity, including neutrophils and the complement system, protects from the development of septic arthritis3,4.

S. aureus is one of the most successful bacterial pathogens because it expresses many colonization and pathogenicity factors, such as envelope-bound adhesins, or many secreted exoenzymes, including exotoxins, proteases, coagulase, collagenase, hyaluronidase, lipases, and nucleases. S. aureus encodes two nucleases: NucA, which is secreted and encoded by nuc1, and Nuc2, which is membrane-anchored with the C-terminus facing the extracellular environment and encoded by nuc25. Of the two nucleases, it is the NucA that plays the crucial role in degrading extracellular DNA and RNA (eDNA and eRNA, respectively)6,7.

The nuc1 gene encodes a pre-pro-protein that is composed of a signal peptide, which is cleaved off by the signal peptidase, and a short pro-region which is processed by a protease releasing the mature and fully active NucA. NucA, also referred to as thermonuclease, is a Ca2+-dependent, nonspecific endonuclease that catalyzes the hydrolysis of both DNA and RNA at the 5’ position of the phosphodiester bond-producing nucleoside 3’-phosphates and 3’-phosphooligonucleotide as end-products8.

NucA functions to degrade extracellular DNA (eDNA), thus promoting the dispersal and destabilization of biofilm. Consequently, in the S. aureus Δnuc1 mutant biofilm formation was shown to be much more pronounced than in the parent strain. Additionally, neutrophils displayed higher NET formation when exposed to biofilms from the nuc1 null mutant, and killed more bacterial cells, suggesting NucA is essential for the survival of S. aureus biofilms irrespective of whether the bacterium is phagocytosed or not9,10. Survival analysis in a hematogenous implant-associated infection mouse model indicated that nuc1 expression is associated with higher mortality11. NucA also plays an important role in bacterial escape from NETs. NETs are released at sites of infection by activated neutrophils and consist of nuclear or mitochondrial DNA as a backbone with embedded antimicrobial peptides, histones, and cell-specific proteases, thereby providing an extracellular matrix to entrap and kill various microbes12. NucA delayed bacterial clearance in the lung and increased mortality after intranasal infection, thus promoting resistance against NET-mediated antimicrobial activity of neutrophils; consequently, the nuc1 deficient mutant was significantly more susceptible to extracellular killing by activated neutrophils13. However, it is not only the degradation of DNA by NucA that is important for the escape from NETs but also the concomitant production of nucleoside 3’-phosphates and 3’-phosphooligonucleotides, which act as substrates for the adenosine synthase also secreted by S. aureus. The adenosine synthase converts the NucA products to deoxyadenosine, which triggers caspase-3-mediated apoptosis in immune cells14.

Here we have investigated the role of NucA in a well-established mouse model of septic arthritis15. Our data show that in the hematogenous septic arthritis mouse model, NucA causes severe bone destruction, rapid weight loss, and high proinflammatory cytokine production. In vitro analysis suggests that reduced killing by neutrophils as well as the NET degrading activity of NucA and its induction of proinflammatory cytokines in certain host cells could be responsible for the high in vivo pathogenicity of a NucA-expressing strain.

Results

The S. aureus Newman Δnuc1 mutant is much less pathogenic in the mouse model of septic arthritis

To assess the role of NucA, S. aureus Newman wild-type (NWT) and its Δnuc1 mutant were evaluated in a mouse model of S. aureus septic arthritis. Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) mice were employed in this study. Mice received intravenous inoculations with either NWT or Δnuc1 and were observed for 7 days to monitor the infection process and immune response. Remarkably, Δnuc1-infected mice exhibited minimal weight loss until day 7, whereas NWT-infected mice continued to lose weight up to 20% by the experiment’s termination on day 7 (Fig. 1a). The severity of septic arthritis was assessed by clinical arthritis frequency and clinical arthritis score (see “Materials and Methods” for details). Here, Δnuc1-infected mice displayed significantly lower clinical arthritis symptoms than NWT-infected mice. Twenty percent of Δnuc1-infected mice developed mild clinical arthritis symptoms up to day 7. In contrast, 40% of NWT-infected mice exhibited clinical arthritis symptoms as early as day 3, and by day 5, all animals had developed severe septic arthritis (Fig. 1b). Not only was the frequency of arthritis higher, but the clinical arthritis score was also elevated in mice infected with the NWT strain compared to the mutant strain (Fig. 1c). Importantly, both the kidney bacterial load (Fig. 1d) and kidney abscess scores (Fig. 1e) were significantly lower in the mice infected with the Δnuc1 mutant compared to those infected with its parental strain. Figure 1f illustrates the clear differences in kidney abscess formation between NWT- and Δnuc1-infected mice.

a Weight development, (b) clinical arthritis frequency, and (c) score were measured from mice infected with either NWT or Δnuc1 mutant for 7 days. d Bacterial counts in the kidney, (e) kidney abscess score, and (f) representative kidney abscess images from mice were investigated on day 7 post-infection. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test (a, c), where the data were presented as the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Statistical significance: not significant, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

To further confirm our clinical observations, we conducted micro-computed tomography (µCT) scans on all joints from mice inoculated with S. aureus (see Materials and Methods for details). Intravenous injection of S. aureus NWT into NMRI mice resulted in severe bone destruction in 12% of joints after 7 days post-infection, whereas mice infected with the Δnuc1 mutant showed almost no sign of bone erosion (Fig. 2a and b). Figure 2c shows representative 3D images of a wrist, a knee, and a shoulder from mice infected either with the Δnuc1 mutant or the NWT strain.

a Bone erosion score and (b) CT frequency of the joints in NMRI mice intravenously injected with S. aureus NWT or its Δnuc1 mutant on day 7 post-infection. c Representative 3D images of micro-computed tomography (µCT) scanning of the mice joints (hand, knee, shoulder) created with µCT scanner after infection. Right panel: NWT; left panel: Δnuc1; red arrow indicates bone erosion. d–g Levels of IL-6, TNF-α, KC, and S100A8/A9 were measured in plasma derived from NMRI mice intravenously injected with NWT or Δnuc1. Statistical analyses were performed using the Fisher exact test (a) and Mann-Whitney U test (b, d–g), where the data were represented in mean ± SEM (b, d–g)., where the data were represented in mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: not significant, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Infection with wild-type S. aureus results in a significant increase in the levels of IL-6 and S100A8/A9

IL-6 and TNF-α are essential for septic arthritis development16,17. S100A8/A9 serves as a predictor of septic arthritis in bacteremic mice, and KC (CXCL1) recruits neutrophils, key innate immune cells essential for disease control4,18. Accordingly, on day 7 post-infection we collected blood samples from the infected mice and measured the levels of these immune mediators: IL-6, TNF-α, KC (CXCL1), and S100A8/A9. As shown in Fig. 2d-g, the levels of IL-6, KC (CXCL1), and S100A8/A9 were markedly reduced in Δnuc1-infected mice as compared to NWT-infected mice. While the TNF-α levels tended to be lower in Δnuc1-infected mice, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Collectively, our results indicate that NucA is a crucial virulence factor for S. aureus pathogenicity in an infection model of septic arthritis. We further investigated possible reasons for the reduced pathogenicity of the Δnuc1 mutant in the septic mouse model using different host cells.

NucA digestion of gDNA decreases TNF-α production in mouse macrophages

S. aureus produces various virulence factors and triggers inflammation. Previous research found that the DNA from S. aureus, containing unmethylated CpG motifs, acts as a factor that triggers arthritis and septic shock19,20. Unmethylated bacterial DNA and CpG motifs are recognized by the toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which is expressed in immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells21,22. Recognition via the TLR9 pathway initiates the host response to S. aureus infection.

As staphylococcal macromolecules are frequently contaminated with lipoproteins/lipopeptides that are sensitively detected by Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) at picomolar levels, cytokine induction could be due to these constituents. Therefore, the mutant S. aureus USA300 LAC JE2Δlgt was tested here as a control to recognize a possible interference of TLR2 and TLR9 ligands on cytokine production. JE2 is a plasmid-cured derivative of USA300 LAC strain, which is still methicillin-resistant and an important model strain to study S. aureus virulence23. JE2Δlgt lacks the phosphatidylglycerol: prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase Lgt, and therefore no lipidation of lipoproteins takes place and no TLR2 response can be triggered by this mutant24,25. By including this mutant and the double mutant JE2Δnuc1Δlgt together with JE2 and JE2Δnuc1 in the comparative immunostimulation studies, it is possible to specifically detect NucA-induced cytokine induction.

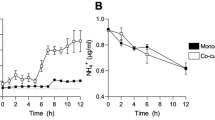

The mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of gDNA from JE2Δlgt and RAW 264.7 (negative control). The standard CpG oligonucleotides ODN2006 and the non-CpG oligonucleotides ODN2137 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (Fig. 3a). gDNA from S. aureus JE2Δlgt increased the production of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α in mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, while gDNA from RAW 264.7 cells did not (Fig. 3a). At a dose of 10 ng/ml, S. aureus gDNA induced the release of high TNF-α levels, as did exposure to 1 µM ODN2006, indicating a high immunostimulatory activity of the staphylococcal DNA.

a Stimulation of mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells with JE2Δlgt gDNA, mammalian gDNA, ODN2006 (CpG oligonucleotide), and ODN2137 (GpC dinucleotides) at varying concentrations for 18 h, followed by TNF-α measurements. b Agarose gel analysis showed the degradation of JE2Δlgt gDNA by gradually decreasing NucA concentration. c Undigested and digested JE2Δlgt gDNA were incubated with RAW 264.7 cells for 18 h. Released TNF-α in cellular supernatants was quantified by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments; ns(not significant), p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest.

Comparative virulence studies in different S. aureus model strains have shown that the USA300 and Newman strain not only have comparable lethality in a mouse sepsis model but are also similar in their hemolytic activity and biofilm formation26. However, in other studies have shown that the two strains exhibit distinct virulence properties; their pathogenicity differs depending on the infection model27,28,29. Both strains also express NucA and the corresponding Δnuc1 mutants could be complemented by pRB473-nuc1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Therefore we used both for the whole study. In S. aureus, NucA is secreted into the supernatant and degrades extracellular DNA and RNA5. This was demonstrated when we incubated the supernatant of JE2 and its mutants JE2Δnuc1, JE2Δlgt, and JE2Δnuc1Δlgt with S. aureus gDNA for 1 h to evaluate the nuclease activity. In all mutants in which nuc1 was deleted, the gDNA remained intact, whereas in JE2 and the JE2Δlgt mutant, the gDNA was completely degraded, indicating that NucA is responsible for gDNA degradation (Supplementary Fig. 1b, 7b). Furthermore, the degradation of eDNA by recombinant NucA, which was expressed and purified from Escherichia coli (Supplementary Figs. 2, 7c), suggested that NucA plays a role in controlling DNA/RNA-dependent immune stimulation. Indeed, the stepwise degradation of S. aureus gDNA by increasing amounts of NucA (from 46 pM to 3 nM) correlated with a stepwise decrease in TNF-α production (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 7a).

The S. aureus nuc1 deletion mutants have an impact on cytokine production in various cell lines

S. aureus activates different host cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and osteoblasts30,31,32. We further investigated whether the immune stimulation of JE2 and its mutants differed in RAW 264.7, neutrophils, and osteoblast-like SAOS-2 cells. We incubated live S. aureus JE2 and its JE2Δnuc1, JE2Δlgt, and JE2Δnuc1Δlgt mutants for 18 h with RAW 264.7, SAOS-2 cells, and 5 h with neutrophils, respectively. To assess the immune responses elicited by different bacterial strains, we measured cytokine production, including classically pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6, as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-1Ra. IL-10 was also very high in sepsis patients, and IL-1Ra and IL-10 also influenced the inflammatory response33,34,35. There was no difference in IL-6 and TNF-α production in RAW 264.7 upon exposure to either JE2 or JE2Δnuc1 (Fig. 4a). In SAOS-2 cells, IL-6 production was decreased in response to all mutants, but there was no difference in TNF-α production. In neutrophils, the production of TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-1Ra was markedly decreased in response to all the mutants (Fig. 4b, c), particularly those lacking lgt (JE2Δlgt and JE2Δnuc1Δlgt). It is not unexpected that the Δlgt mutants induce less cytokines since lipoproteins/lipopeptides trigger a very strong innate immune response. As compared with NWT, there was less IL-6 production in RAW 264.7 and no significant difference in IL-6 and TNF-α in SAOS-2 when exposed to the Δnuc1 strain (Supplementary Fig. 3). As the generated mutants showed hardly any difference in growth and hemolytic activity as compared to the parental strain (Supplementary Fig. 1a, c and d), we assume that all the effects seen are mainly due to the deletion of nuc1 or lgt genes.

The PBS-washed bacteria were incubated with (a) RAW 264.7 cells at an MOI = 30, (b) SAOS-2 cells at an MOI = 3, and (c) with neutrophils at an MOI = 50. Cellular supernatants were collected after 18 h for RAW 264.7 and SAOS-2 cells, and after 5 h for neutrophils to measure various cytokines by ELISA assay. For neutrophils, the experiments were displayed from n = 10 donors. Triplet experiments were conducted; error bars indicate ± SEM; not significant, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest.

JE2Δnuc1 exhibits decreased internalization or survival in various host cells

S. aureus can be engulfed by multiple cells36,37. We determined bacterial survival and phagocytosis in neutrophils, following a previously used protocol38,39. With different conditions tested, we found that better results were obtained with an MOI (multiplicity of infection)=2 for the phagocytosis assay and an MOI = 0.1 for the bacterial killing assay. Under these conditions, the survival of JE2Δnuc1 was decreased already at early time points as compared to JE2 (Fig. 5a). This was consistent with a lower phagocytosis index in JE2Δnuc1 (Fig. 5a). This led us to investigate whether live JE2 and its mutants differ in internalization by other host cells such as RAW 264.7. To assess only intracellular survival, membrane adherent and extracellular bacteria were killed after 1.5 h incubation, and then the CFU of internalized bacteria per host cell was determined. In RAW 264.7 we observed lower intracellular numbers of JE2Δnuc1 cells as compared to JE2 and the complementation strain JE2Δnuc1(pRB473-nuc1), suggesting that survival was affected by nuc1 (Fig. 5b).

a For bacterial killing in neutrophils, JE2, JE2Δnuc1 and JE2Δnuc1 complemented with plasmid-expressed nuc1 (JE2Δnuc1 pRB473-nuc1) were opsonized with 10% human pooled serum. Neutrophils were incubated with bacteria at an MOI = 0.1 for 1 h and bacterial survival was checked at 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, and 1 h after exposure to neutrophils. Fluorescence-labeled bacteria were incubated with neutrophils at an MOI of 1:2 and the phagocytosis index was calculated 1 h after incubation via FACS. b To investigate bacterial survival in RAW 264.7, RAW 264.7 was incubated with JE2, JE2Δnuc1, and JE2Δnuc1(pRB473-nuc1) at an MOI of 1:20 for 1.5 h. Extracellular and attached bacteria were removed by gentamicin and lysostaphin before lysing the cells. Neutrophils used in these experiments were obtained from 4 donors and the other experiments were performed at least three times; error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest. Statistical significance: not significant, p > 0.05, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001.

Effect of live bacteria and supernatant on NETs formation and clearing

Neutrophils act as the first defense line of the innate immune system and form NETs to clear pathogens38. NETs consist of a DNA backbone coated with various proteins, such as myeloperoxidase (MPO), nuclear proteins (histones), neutrophil elastase (NE), and calprotectin40,41. In S. aureus, NucA can degrade extracellular DNA, thereby reducing NET formation and evading immune clearance. Here, the neutrophils were exposed to live bacteria (MOI = 1:2) and bacterial supernatants (2%) for 2 h following eDNA-staining with SYTOX Green. Live bacteria caused a slow increase in NETosis, whereas the bacterial supernatant induced a stronger NET release in a shorter time (Fig. 6a, b). Additionally, neutrophils were still viable after 3 h incubation (Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Sytox Green assay of neutrophils exposed to JE2, JE2Δnuc1, JE2Δlgt, and JE2Δnuc1Δlgt with live bacteria (MOI = 1:2) or overnight supernatant (2% volume) for 2 h. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) of Sytox Green normalized to Triton X-100-lysed neutrophils are shown. b Representative fluorescence images of Sytox Green staining after 3 h of incubation. Scale bar = 500 µm. c Representative images of immunofluorescent staining after 1 h of incubation. Blue: DNA (Hoechst 33342); Green: myeloperoxidase, MPO; Red: citrullinated histone H3, citH3, scale bar: 500 µm. The graph displays the average values ± SEM obtained from 4 donors; not significant, p > 0.05, one-way between-groups ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest.

Immunofluorescence staining of NET formation (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs. 5, 6) further confirmed NETosis occurred, as visible by positive staining for DNA (blue), MPO (green), and citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3, red) after 1 h incubation of neutrophils with bacterial cell-free supernatant but not with live bacteria. NET was higher in response to JE2Δnuc1 mutants and their supernatants than in the parental strain, as also can be observed in fluorescence microscopy images (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6). This suggests that the supernatant of Δnuc1 mutants is less effective in degrading DNA, resulting in increased levels of NETs.

Discussion

The comparative studies between S. aureus parental strain and the Δnuc1 mutant revealed that NucA is an important virulence factor in septic arthritis. S. aureus NWT-infected mice showed marked weight loss, much increased clinical arthritis frequency, a 3-fold higher abscess score, severe bone erosion, and very high IL-6 content in the plasma. In contrast, the Δnuc1-infected mice showed hardly any signs of septic arthritis, almost no weight loss, their clinical arthritis and abscess scores were much lower, and the bacterial load in kidneys was decreased (Fig. 1). Most remarkable, however, was that Δnuc1-infected mice showed almost no bone erosion in the joints (Fig. 2a, b, c). Here, we provide three lines of in vitro evidence to support our in vivo observations: 1) NucA efficiently degrades bacterial DNA, which can trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, known for their critical roles in septic arthritis development; 2) NucA production may increase the intracellular survival of S. aureus; 3) NucA produced by S. aureus effectively digests NETs formed by neutrophils, potentially aiding bacterial evasion from innate immune killing, and thereby promoting bacterial survival and exacerbating disease severity.

Most bacteria release DNA and RNA during proliferation. In S. aureus DNA is released during cell lysis resulting from induction of prophages or activation of proteins with holin-like properties such as CidA and LrgA42. The secreted NucA degrades eDNA/RNA very efficiently to allow the reuse of the degradation products. How powerful NucA is in degrading eDNA is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1b and 7b. When the supernatants of JE2 and its mutants were incubated with gDNA, it was completely degraded within 1 h by the supernatant of JE2 but not by the Δnuc1 mutants. This efficient degradation of eDNA not only ensures the reuse of nucleic acid building blocks but also the escape of staphylococci from a biofilm community or NETs, providing NucA-expressing bacteria a clear advantage during infection43.

It is known that bacterial DNA triggers an inflammatory response and induces cytokine production via the TLR9 receptor21,22. Further studies in mice have proven that DNA from S. aureus results in arthritis20,44. To check the potential involvement of bacterial DNA and the role of NucA in inflammation, gDNA was isolated from the JE2Δlgt mutant to avoid lipoprotein contamination. The NucA-digested DNA and intact DNA were then incubated with RAW 264.7 cells. In these cells, staphylococcal DNA induced TNF-α production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a); as the gDNA was progressively degraded by increasing concentrations of NucA, TNF-α production decreased with progressing degradation (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Similar results were also obtained with Group A Streptococcus (GAS), which produces the DNase Sda1 to prevent IFN-α and TNF-α secretion by murine macrophages45. TNF-α is recognized as pathogenic in the initiation and progression of septic arthritis16. Moreover, combining antibiotics with a TNF-α inhibitor yielded superior results as compared to antibiotics alone, effectively reducing synovitis and joint destruction in a mouse model of septic arthritis46. Simultaneously, TNF-α plays a crucial role in the Th1 response and primes phagocytes for effective elimination of pathogens47. Anti-TNF-α treatment has been shown to compromise immune killing efficacy, leading to increased kidney bacterial load in a mouse model of S. aureus septic arthritis48. Hence, NucA disrupts the immune-stimulating effect of bacterial DNA, potentially leading to an elevated kidney bacterial load.

As we showed that NucA-digested bacterial eDNA has no immune-stimulating activity in murine macrophages, we expected that the Δnuc1 mutant, in which eDNA is not degraded (Supplementary Fig. 1b, 7b), would elicit a stronger immune response than the parental strain in various cell types. S. aureus stimulates the immune response in various cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, as well as non-immune cells, such as osteoblast cells30,31,32. In addition, osteoblasts and osteoclasts are responsible for bone remodeling and construction49,50. Accordingly, macrophages RAW 264.7, osteoblast cells SAOS-2 and neutrophils were employed in this study. JE2Δnuc1 mutant triggered no IL-6 or TNF-α production in RAW 264.7 (Fig. 4a, b). What we see is that lipoproteins play a decisive role in immune stimulation in RAW 264.7 cells, which is in agreement with earlier results25,51,52. However, JE2Δnuc1 mutant induced less IL-6 in SAOS-2 cells and less TNF-α in neutrophils, while NWTΔnuc1 induced less IL-6 in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition to measuring pro-inflammatory cytokines, we also measured the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 and IL-1Ra, in neutrophils to assess the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory responses during infection. IL-10 is critical for regulating and balancing the infection and immune response, which typically increases during inflammation53,54. IL-1Ra, as a natural antagonist of IL-1 signaling and related to extensive IL-10 production, could influence the inflammatory response and is used to treat inflammation55,56. IL-1R knock-out mice developed more severe septic arthritis, but IL-1R treatment for inflammation-related diseases could also increase the infections in sepsis35,48,57. When neutrophils were exposed to the parental strain and its mutants, JE2Δnuc1 showed less IL-10 and IL-1Ra production. Those results give a hint that NucA has an impact on immune stimulation.

The next key question that arises in this context is the molecular causes of NucA-induced septic arthritis and bone erosion. To investigate this, we measured the levels of several cytokines in the blood of mice on 7 days post-infection. Previous studies have shown that IL-6 and TNF-α are critical for septic arthritis development16,17. Patients who have septic arthritis exhibit high concentrations of TNF58,59. Lack of TNF-α has been associated with an inefficient ability to clear bacteria16. In addition, KC attracts neutrophils that control septic arthritis, and S100A8/A9 has been identified as an early predictor of septic arthritis during S. aureus bacteremia4,18. Since in vivo experiments showed minimal differences in TNF-α induction after infection with WT or nuc1 mutant, we further investigated this phenotype in vitro. However, in macrophage-like and osteoblast-like cells, JE2 and JE2Δnuc1 did not cause any significant difference in TNF-α production (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3). In neutrophils, more TNF-α production was induced by the parental strain than by the nuc1 mutant. In the septic arthritis mouse model, NWT induced an almost 100-fold higher IL-6 production in plasma than its Δnuc1 mutant. The very high IL-6 content in the blood reflects the severity of septic arthritis by infection with the NucA-expressing strain. In fact, sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome is correlated with an increased IL-6 content. However, there is no significant difference in IL-6 production between JE2 and its Δnuc1 mutant in the different cell cultures, showing once again that the in vitro situation does not always reflect the in vivo situation. IL-6, which is mainly produced by macrophages and T lymphocytes in response to pathogens, is not only a key player in rheumatoid arthritis, but it also promotes megakaryocyte maturation and the release of platelets when reaching the bone marrow. IL-6 has emerged alongside IL-1 and TNF as a master regulator of inflammation: it is essential for innate and adaptive immunity, is required for efficient pathogen clearance, and has important physiological roles in humans regulating the acute-phase response, hematopoiesis, metabolic rate, lipid homeostasis, and neural development.

The pronounced upregulation of S100A8/A9 in NWT-infected mice compared to the Δnuc1-infected mice could be induced by IL-6-triggered inflammation and leukocyte recruitment60,61. The high levels of IL-6 and S100A8/A9 at the end of the mouse experiment reflect the severity of infection. Inflammatory cytokines play a role in the bone remodeling process. For example, in IL-6 deficient mice, bone erosion was reduced62. Therefore, the NucA-expressing strain could cause high IL-6 production, which may lead to uncontrolled progression of bone destruction by osteoclasts.

Furthermore, we also found that the JE2Δnuc1 mutant exhibited reduced survival, which could explain why we detected less bacteria inside neutrophils 1 h after exposure to neutrophils (Fig. 5a). This encouraged us to investigate the internalization in other cell lines. As shown in Fig. 5b, we also observed reduced numbers of JE2Δnuc1 in RAW 264.7 cells. These findings indicate that NucA increases S. aureus survival, likely both extracellularly and intracellularly, which may contribute to an increase in the severity of septic arthritis.

In hematogenous septic arthritis, compromised innate immune defenses increase the likelihood that bacteria in the bloodstream invade joints, ultimately leading to the development of septic arthritis15. Neutrophils are recognized as vital immune cells guarding against S. aureus septic arthritis. Neutrophil-depleted mice exhibited heightened and more frequent septic arthritis, coupled with compromised bacterial clearance as evidenced by elevated CFU counts in both blood and kidneys4. We also compared the effects of live bacteria and the corresponding culture supernatant on degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs represent a form of innate immune response that prevents microorganisms from spreading, while the high local concentration of antimicrobial agents may kill bacteria63,64. The S. aureus thermonuclease NucA is known to degrade the DNA within NETs to escape scavenging and killing38. It has been shown that the combined activity of S. aureus nuclease and adenosine synthase converts extracellular DNA to deoxyadenosine (dAdo) in staphylococcal abscesses. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) mediates dAdo transportation in macrophages, leading to caspase-3-induced apoptosis14,65,66. This could be happening in our model as well, but we did not analyze the viability of macrophages isolated from abscesses.

When we exposed neutrophils to live S. aureus, we observed a time-dependent increase in stained eDNA, but there was no pronounced difference between stimulation with JE2 and its mutants (Fig. 6a, b) until 2 h after exposure. When we incubated neutrophils with the corresponding supernatants, we observed a clear difference in the response to JE2Δnuc1 mutants as compared to other strains (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6). Immunofluorescence revealed a stronger DNA signal in response to JE2Δnuc1 supernatants, suggesting decreased NET degradation. The question remains as to why we did not see a major difference between the wild-type and the Δnuc1 live bacteria. We assume that by washing the bacterial cells with PBS, NucA is washed out and the bacteria are rapidly phagocytosed and killed when incubated with neutrophils.

Overall, our study suggests that NucA plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of S. aureus septic arthritis, as evidenced by Δnuc1-infected mice showing reduced arthritis severity, bone erosion, and kidney abscess formation, alongside lower bacterial loads. In vitro data further support these findings, demonstrating that NucA degrades bacterial DNA, shields S. aureus from killing, and digests neutrophil extracellular traps, ultimately promoting bacterial survival and worsening disease severity. How NucA triggers severe bone erosion is the subject of further research. In a summary image, we illustrated the main differences between NucA-producing and -non-producing S. aureus strains (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 1. All the primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was grown in Luria-broth medium (LB), and Staphylococcus aureus strains were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Millipore, Merck) or basic medium (BM) broth (Luria broth supplemented with 0.1% K2HPO4 and 0.1% glucose) or stored as previously mentioned67. To keep the plasmids in the bacteria, E. coli was supplied with ampicillin or kanamycin and S. aureus was supplied with 10 µg/ml chloramphenicol. For comparison of growth kinetics, the S. aureus JE2, Newman, and their mutants were grown in TSB medium, and measured with Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher) for 24 h.

Deletion of nuc1 and lgt in S. aureus

nuc1 is the nuclease1-encoding gene and lgt is the lipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase enzyme-encoding gene7,25. For deleting nuc1 and lgt genes, the knockout plasmid pBASE6 was employed. The disruption primers were designed to contain upstream and downstream of the target gene regions. Fragments were generated by PCR and subcloned into EcoRV-digested pBASE6 vector, resulting in pBASE6Δnuc1 and pBASE6Δlgt. The resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli DC10B for amplification. Then, plasmids were isolated and verified by DNA sequencing. The correct plasmids pBASE6Δnuc1 and pBASE6Δlgt were transformed into an intermediate host, S. aureus RN4220, by electroporation to restrict foreign DNA and then into S. aureus JE2 or S. aureus Newman (NWT). The process for deletion of lgt and nuc1 from S. aureus was followed as previously described68. Positive colonies were incubated in TSB with 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm) at 43 °C overnight and then transferred to TSB supplemented 7.5 μg/ml Cm at 43 °C for another overnight incubation. The culture was plated and a single colony was picked for inoculation at 30 °C. The overnight culture was diluted and plated onto TSA plates containing 1 μg/ml anhydrotetracycline (ATc) for two days. Colonies from the plate were streaked on TSA with or without Cm. The colonies that could grow on TSA plate but not on TSA with Cm were selected for PCR verification, resulting in JE2Δnuc1, NewmanΔnuc1, JE2Δlgt, and JE2Δnuc1Δlgt.

Construction of complementation strain

For complementation, the plasmid pRB473-nuc1 was introduced. The nuc1 fragment was amplified, ligated to pRB473 plasmids, and transformed into E. coli DC10B. Positive colonies were selected and verified via DNA sequencing. The correct plasmid was purified and transformed into JE2Δnuc1 and Δnuc1, yielding JE2Δnuc1(pRB473-nuc1) and Δnuc1(pRB473-nuc1).

Hemolytic activity and nuclease activity assays

Bacteria were grown in TSB medium overnight. The OD578 of overnight culture was adjusted and spotted on the Blood Agar (TSA with Sheep Blood) plates (Thermo Fisher) at 37 oC, and then the hemolysis zone was measured. The supernatants of overnight culture were checked for nuclease activity using DNase Test Agar with Toluidine Blue (Merck, Millipore). The DNase Test Agar plates were incubated at 37oC.

Mouse model for S. aureus septic arthritis

To compare the pathogenicity of S. aureus Newman wild-type strain (NWT) and its Δnuc1 mutant, a septic arthritis mouse model was used. NMRI female mice, aged 8 weeks, were purchased from Envigo (Venray, Netherlands). All mice were housed at the animal facility at the University of Gothenburg. Mice were kept under standard temperature and light conditions and were fed laboratory chow and water ad libitum. Mice (n = 5/group) housed in the same cage were randomly assigned to receive an intravenous injection of 200 µl of an arthritic dose of either S. aureus Newman strain (2.8 × 106 CFU/mouse) or Δnuc1 mutant (2.8 × 106 CFU/mouse). Mice were monitored for weight loss and clinical signs of arthritis from day 0 to day 7 in a manner blinded to the bacterial strains. Morphine (Abcur AB, 10 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously (s.c.) daily to all mice starting three days after infection to alleviate pain associated with septic arthritis. On day 7, mice were sacrificed to collect samples, including blood, kidneys, and joints. Kidneys were collected aseptically and scored on a scale of 0 (no abscess), 1 (mild abscess), 2 (moderate abscess) to 3 (severe abscess). The kidneys were then minced and diluted with sterile PBS. Dilutions were plated on horse blood agar plates, incubated at 37 oC for 24 h, and the colonies obtained were counted using a colony counter (Stuart Scientific, Made in the UK).

Clinical evaluation of arthritis

Observers (M.D. and T.J.) blinded to the treatment groups visually inspected all 4 limbs of each mouse. Arthritis was defined as erythema and/or swelling of the joints. A clinical scoring system ranging from 0 to 3 was used for each paw (0, no inflammation; 1, mild visible swelling and/or erythema; 2, moderate swelling and/or erythema; and 3, marked swelling and/or erythema).

Microcomputed Tomography (μCT)

On 7 day post-infection, the mice were sacrificed and all paws were scanned by SkyScan 1176 μCT (Bruker, Antwerp, Belgium). The scanning was conducted at 55 kV/ 455 μA, with a 0.2-mm aluminum filter. The exposure time was 47 ms. The X-ray projections were obtained at 0.7° intervals with a scanning angular rotation of 180°. The NRecon software (version 1.6.9.8; Bruker) was used to reconstruct 3D images which were further evaluated by using CT-Analyzer (version 2.7.0; Bruker). Each joint was evaluated by two researchers (M.D. and T.J.), in a blinded manner, using a scoring system from 0 to 3 (0: healthy joint; 1: mild bone destruction; 2: moderate bone destruction; and 3: marked bone destruction) as previously described17.

NucA expression and purification

NucA is an extracellular enzyme, which is secreted as mature Nuc1. The nucA gene was cloned into the vector pET28a with C-terminal His-tag and this construct was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). The transformant carrying pET28a-NucA-6xHis was grown in LB at 37 oC supplemented with 50 µg/ml ampicillin. When OD600 reached 0.6–0.8, the bacteria were induced with 1 mM IPTG at 18 oC overnight for overexpressing NucA. The overnight culture was collected, resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl), and lysed by an ultrasonic sonicator with a pulse every 4 s for 4 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant of lysate was collected and then loaded onto an Ni-NTA column. Fractions containing NucA were collected with Buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. NucA enzyme was dialyzed with PBS, concentrated, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until use.

Genomic bacterial DNA (gDNA) degradation assay with NucA

S. aureus JE2Δlgt was cultured in TSB medium overnight. The bacterial pellet was collected and resuspended in TE buffer supplemented with lysostaphin and RNase at 37 °C for 30 min. Bacterial gDNA was then purified via phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, precipitated with isopropanol, washed with ethanol, and then dissolved in H2O69. gDNA was incubated with varying concentrations of recombinant NucA for 1 h at 37 oC. Samples were then added to RAW 264.7 cells for stimulation and loaded on the agarose gel for visualization.

Preparation of bacteria and bacterial supernatant

BM medium was used for inoculating S. aureus at 37 oC with shaking from fresh BM agar plates. Cultures were harvested after 16 h by centrifuging and washed with PBS. To get bacterial dosage (MOI, multiplicity of infection), bacteria were calculated to OD/CFU. Bacterial supernatants were collected and filtered with a 0.2 µm pyrogen-free round column. The supernatants were kept on ice until use and adjusted to equal concentrations according to bacterial number. The supernatant was tested for its ability to degrade gDNA and its activity on neutrophils.

Neutrophil isolation

Venous blood was freshly collected by EDTA-tubes (Sarstedt, Germany) from several healthy individuals. 6 mL blood was layered on 6 mL of Lymphocyte poly-cell separation medium (Cedarlane, Burlington, Canada). Centrifugation was done without pause, at 500 × g for 40 min at room temperature. The PMN layer was collected and washed twice with 12 mL PBS, and centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min at room temperature with settings of acceleration 5 and deceleration 4. Cells were resuspended in RPMI medium without phenol red (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). Cell counts were obtained by the Trypan Blue exclusion method, utilizing a Neubauer counting chamber.

Cell culture and immune stimulation assay

The murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 oC with 5% CO2. The human osteoblast-like cell line SAOS-2 was grown in McCoy’s 5 A Medium (Sigma) supplemented with 15% FBS, 1% glucose, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Prior to stimulation, RAW 264.7 and SAOS-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated overnight until reaching confluency, while neutrophils were directly seeded into the plates before adding all stimulants. Immune stimulation was performed for 18 h at 37 oC and 5% CO2, except for neutrophils which were stimulated for 5 h. The cellular supernatants were then collected and stored at −20 oC until determining the cytokines production.

Detection of cytokines by ELISA

Cytokines collected from the cellular supernatants of different cell lines were measured with the uncoated ELISA kit (Invitrogen) according to instructions. The plasma levels of IL-6, TNF-α, keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), and S100A8/A9 in blood collected from NMRI mice intravenously infected with Newman WT (NWT) and Δnuc1 were quantified using DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems Europe) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Neutrophil bacterial killing assay

JE2 and JE2Δnuc1 were grown overnight. Bacteria were collected, regrown to the log phase, washed with PBS, and opsonized with 10% human pooled serum in RPMI for 1 h at 37 oC. Neutrophils were seeded in 24-well plates, incubated with bacteria (100%) at an MOI = 0.1. After 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, and 1 h, the neutrophils were lysed with ice-cold ddH2O and centrifuged for 15 min at 4 oC. The lysates were plated on agar plates with serial dilutions and CFUs were counted the next day. The S. aureus survival (killing) was calculated by comparing the counted CFU to the original added CFU and normalized to JE2.

Phagocytosis assay

Bacteria were grown overnight, collected, regrown until the log phase, and washed with PBS. Bacteria were opsonized with 10% human pooled serum in RPMI without phenol red for 1 h at 37 oC and then were labeled with Alexa Flour 633 conjugate (Invitrogen, W21404) for 20 min at 37 oC. The unlabeled fluorochrome was washed twice by PBS. Neutrophils were seeded into 24-well plates and incubated with bacteria at an MOI = 2. After 1 h incubation, the neutrophils were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min on ice. The fluorescence intensity of fixed neutrophils was determined with a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). The phagocytotic index was calculated as number of fluorescent-positive neutrophils multiplied by the fluorescence mean and normalized to JE2 parent strain to minimize the individual error. This index shows how many bacteria were phagocytosed per cell.

Internalization assay

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in 24-well plates with 500 µl of culture medium until reaching confluency. Cells were washed with PBS, and the pre-warmed culture medium without antibiotics was added to each well. Bacteria were grown to the log phase before infection. The cells were then incubated with bacteria for 1.5 h to yield an MOI of 20:1. After incubation, gentamycin, and lysostaphin were added to kill the extracellular bacteria for 1 h. The cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 supplemented with 0.05% Trypsin and lysates were plated to determine internalized bacteria70. Internalization was calculated as CFU of internalized bacteria/host cell-seeded and normalized to JE2.

Sytox green assay

Isolated neutrophils were prepared to be 2 × 105 cells/mL, and then 1 µM Sytox Green (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) was added. 1% Triton X-100 solution was used for extracellular DNA normalization. Cells were stimulated for 5 h with MOI = 1:2 live bacteria and 2% overnight bacterial supernatant. Fluorescent intensity was measured every 30 min at Ex 485 nm/Em 520 nm, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 by the microplate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). Microscopic images were taken with EVOS Fl (Thermo Fisher) fluorescence microscope at 3 h of incubation.

Live-dead staining

Isolated neutrophils were incubated with an MOI of 1:2 live bacteria and 2% overnight bacterial supernatant. To visualize live cells, neutrophils were stained with 2 µM Calcein AM and Ethidium Bromide for 10 min at 37 oC in RPMI medium without phenol red. Images were taken with the EVOS Fl (Thermo Fisher) fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence

Neutrophils were diluted to 3 × 105 cells/mL and seeded onto self-prepared poly-L-lysine coated chamber slides. The cells were incubated with live bacteria at an MOI of 2 and 2% overnight bacterial supernatant at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 for 1 h. Following incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, the cells were incubated overnight with myeloperoxidase (1:200 in PBS, sc-52707, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) and citH3 (1:1000 in PBS, ab5103, Abcam). After washing with PBS, the staining was continued with an Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000 in PBS, A10667, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Hoechst 33342 (2 µg/mL) for 2 h. The chambers were then removed, and the slides were mounted using Fluoromount G mounting medium (Thermo Fisher) and covered with coverslip. Microscopy was conducted using an EVOS Fl fluorescence microscope (Thermo Fisher).

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of Animal Research of Gothenburg approved all experiments conducted on mice. The mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the Swedish Board of Agriculture’s regulations and recommendations on animal experiments. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Blood was collected from healthy adult volunteers and written informed consent was given. The institutional review board of the University of Tübingen approved the study and all adult subjects provided informed consent. This study was done in accordance with the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Tübingen that approved the study (Approval number 015/2014 BO2). All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Statistics and reproducibility

All the data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software). The data are presented in mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance: ns (not significant) p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Details of statistical analyses for each experiment are provided in “Materials and Methods”.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Primary source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Additional requests for the data and materials in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mathews, C. J., Weston, V. C., Jones, A., Field, M. & Coakley, G. Bacterial septic arthritis in adults. Lancet 375, 846–855 (2010).

Kaandorp, C. J., Krijnen, P., Moens, H. J., Habbema, J. D. & van Schaardenburg, D. The outcome of bacterial arthritis: a prospective community-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 40, 884–892 (1997).

Na, M. et al. Deficiency of the complement component 3 but not factor b aggravates Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis in mice. Infect. Immun. 84, 930–939 (2016).

Verdrengh, M. & Tarkowski, A. Role of neutrophils in experimental septicemia and septic arthritis induced by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 65, 2517–2521 (1997).

Tang, J. et al. Two thermostable nucleases coexisted in Staphylococcus aureus: evidence from mutagenesis and in vitro expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 284, 176–183 (2008).

Kiedrowski, M. R. et al. Staphylococcus aureus Nuc2 is a functional, surface-attached extracellular nuclease. PLoS One 9, e95574 (2014).

Hu, Y., Xie, Y., Tang, J. & Shi, X. Comparative expression analysis of two thermostable nuclease genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 265–271 (2012).

Cuatrecasas, P., Fuchs, S. & Anfinsen, C. B. The interaction of nucleotides with the active site of staphylococcal nuclease. Spectrophotometric studies. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 4759–4767 (1967).

Bhattacharya, M. et al. Leukocidins and the nuclease Nuc prevent neutrophil-mediated killing of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Infect. Immun. 88 (2020).

Bhattacharya, M. et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms release leukocidins to elicit extracellular trap formation and evade neutrophil-mediated killing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7416–7421 (2018).

Yu, J. et al. Thermonucleases contribute to Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation in implant-associated infections-A redundant and complementary story. Front. Microbiol. 12, 687888 (2021).

von Kockritz-Blickwede, M. & Nizet, V. Innate immunity turned inside-out: antimicrobial defense by phagocyte extracellular traps. J. Mol. Med.87, 775–783 (2009).

Berends, E. T. et al. Nuclease expression by Staphylococcus aureus facilitates escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Innate Immun. 2, 576–586 (2010).

Thammavongsa, V., Missiakas, D. M. & Schneewind, O. Staphylococcus aureus degrades neutrophil extracellular traps to promote immune cell death. Science 342, 863–866 (2013).

Jin, T. Exploring the role of bacterial virulence factors and host elements in septic arthritis: insights from animal models for innovative therapies. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1356982 (2024).

Hultgren, O., Eugster, H. P., Sedgwick, J. D., Korner, H. & Tarkowski, A. TNF/lymphotoxin-alpha double-mutant mice resist septic arthritis but display increased mortality in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 161, 5937–5942 (1998).

Fatima, F. et al. Radiological features of experimental staphylococcal septic arthritis by micro computed tomography scan. PLoS One 12, e0171222 (2017).

Deshmukh, M. et al. Gene expression of S100a8/a9 predicts Staphylococcus aureus-induced septic arthritis in mice. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1146694 (2023).

Sparwasser, T. et al. Bacterial DNA causes septic shock. Nature 386, 336–337 (1997).

Deng, G. M., Nilsson, I. M., Verdrengh, M., Collins, L. V. & Tarkowski, A. Intra-articularly localized bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs induces arthritis. Nat. Med. 5, 702–705 (1999).

Krieg, A. M. et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature 374, 546–549 (1995).

Hemmi, H. et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408, 740–745 (2000).

Fey, P. D. et al. A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. mBio 4, e00537–00512 (2013).

Hashimoto, M. et al. Not lipoteichoic acid but lipoproteins appear to be the dominant immunobiologically active compounds in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 177, 3162–3169 (2006).

Stoll, H., Dengjel, J., Nerz, C. & Götz, F. Staphylococcus aureus deficient in lipidation of prelipoproteins is attenuated in growth and immune activation. Infect. Immun. 73, 2411–2423 (2005).

Herbert, S. et al. Repair of global regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and comparative analysis with other clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 78, 2877–2889 (2010).

Dos Santos, D. C. et al. Staphylococcus chromogenes, a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species that can clot plasma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 1372–1375 (2016).

Baba, T., Bae, T., Schneewind, O., Takeuchi, F. & Hiramatsu, K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 190, 300–310 (2008).

Kennedy, A. D. et al. Targeting of alpha-hemolysin by active or passive immunization decreases severity of USA300 skin infection in a mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 1050–1058 (2010).

Bost, K. L. et al. Staphylococcus aureus infection of mouse or human osteoblasts induces high levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-12 production. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1912–1920 (1999).

Marriott, I. et al. Osteoblasts produce monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in a murine model of Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis and infected human bone tissue. Bone 37, 504–512 (2005).

Gunn, N. J. et al. A human osteocyte cell line model for studying Staphylococcus aureus persistence in osteomyelitis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 781022 (2021).

Alanara, T., Karstila, K., Moilanen, T., Silvennoinen, O. & Isomaki, P. Expression of IL-10 family cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: elevated levels of IL-19 in the joints. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 39, 118–126 (2010).

Osuchowski, M. F., Welch, K., Siddiqui, J. & Remick, D. G. Circulating cytokine/inhibitor profiles reshape the understanding of the SIRS/CARS continuum in sepsis and predict mortality. J. Immunol. 177, 1967–1974 (2006).

Hultgren, O. H., Svensson, L. & Tarkowski, A. Critical role of signaling through IL-1 receptor for development of arthritis and sepsis during Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 168, 5207–5212 (2002).

Nair, S. P., Bischoff, M., Senn, M. M. & Berger-Bachi, B. The sigma B regulon influences internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by osteoblasts. Infect. Immun. 71, 4167–4170 (2003).

Almeida, R. A., Matthews, K. R., Cifrian, E., Guidry, A. J. & Oliver, S. P. Staphylococcus aureus invasion of bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Dairy Sci. 79, 1021–1026 (1996).

Lu, T., Porter, A. R., Kennedy, A. D., Kobayashi, S. D. & DeLeo, F. R. Phagocytosis and killing of Staphylococcus aureus by human neutrophils. J. Innate Immun. 6, 639–649 (2014).

Weiss, E., Schlatterer, K., Beck, C., Peschel, A. & Kretschmer, D. Formyl-Peptide receptor activation enhances phagocytosis of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 221, 668–678 (2020).

Halverson, T. W., Wilton, M., Poon, K. K., Petri, B. & Lewenza, S. DNA is an antimicrobial component of neutrophil extracellular traps. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004593 (2015).

Papayannopoulos, V., Metzler, K. D., Hakkim, A. & Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell Biol. 191, 677–691 (2010).

Ranjit, D. K., Endres, J. L. & Bayles, K. W. CidA and LrgA proteins exhibit holin-like properties. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2468–2476 (2011).

Sultan, A. R. et al. During the early stages of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation, induced neutrophil extracellular traps are degraded by autologous thermonuclease. Infect. Immun. 87 (2019).

Deng, G. M. & Tarkowski, A. The role of bacterial DNA in septic arthritis. Int J. Mol. Med. 6, 29–33 (2000).

Uchiyama, S., Andreoni, F., Schuepbach, R. A., Nizet, V. & Zinkernagel, A. S. DNase Sda1 allows invasive M1T1 Group A Streptococcus to prevent TLR9-dependent recognition. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002736 (2012).

Fei, Y. et al. The combination of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor and antibiotic alleviates staphylococcal arthritis and sepsis in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 348–357 (2011).

Onnheim, K., Bylund, J., Boulay, F., Dahlgren, C. & Forsman, H. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha primes murine neutrophils when triggered via formyl peptide receptor-related sequence 2, the murine orthologue of human formyl peptide receptor-like 1, through a process involving the type I TNF receptor and subcellular granule mobilization. Immunology 125, 591–600 (2008).

Ali, A. et al. CTLA4 immunoglobulin but not anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy promotes staphylococcal septic arthritis in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 1308–1316 (2015).

Nakashima, K. & de Crombrugghe, B. Transcriptional mechanisms in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Trends Genet. 19, 458–466 (2003).

Köllisch, G. et al. Various members of the Toll-like receptor family contribute to the innate immune response of human epidermal keratinocytes. Immunology 114, 531–541 (2005).

Nguyen, M. T. & Götz, F. Lipoproteins of Gram-positive bacteria: key players in the immune response and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 891–903 (2016).

Nguyen, M. T. et al. Lipid moieties on lipoproteins of commensal and non-commensal staphylococci induce differential immune responses. Nat. Commun. 8, 2246 (2017).

Leech, J. M., Lacey, K. A., Mulcahy, M. E., Medina, E. & McLoughlin, R. M. IL-10 Plays Opposing Roles during Staphylococcus aureus Systemic and Localized Infections. J. Immunol. 198, 2352–2365 (2017).

Kasten, K. R., Muenzer, J. T. & Caldwell, C. C. Neutrophils are significant producers of IL-10 during sepsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 28–31 (2010).

Fischer, E. et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist circulates in experimental inflammation and in human disease. Blood 79, 2196–2200 (1992).

Dinarello, C. A. Interleukin-1 and interleukin-1 antagonism. Blood 77, 1627–1652 (1991).

Ali, A. et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist treatment aggravates staphylococcal septic arthritis and sepsis in mice. PLoS One 10, e0131645 (2015).

Talebi-Taher, M., Shirani, F., Nikanjam, N. & Shekarabi, M. Septic versus inflammatory arthritis: discriminating the ability of serum inflammatory markers. Rheumatol. Int. 33, 319–324 (2013).

Saez-Llorens, X. et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 beta in synovial fluid of infants and children with suppurative arthritis. Am. J. Dis. Child 144, 353–356 (1990).

Ma, L., Sun, P., Zhang, J. C., Zhang, Q. & Yao, S. L. Proinflammatory effects of S100A8/A9 via TLR4 and RAGE signaling pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. Int J. Mol. Med. 40, 31–38 (2017).

Gopal, R. et al. S100A8/A9 proteins mediate neutrophilic inflammation and lung pathology during tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 1137–1146 (2013).

Wong, P. K. et al. Interleukin-6 modulates production of T lymphocyte-derived cytokines in antigen-induced arthritis and drives inflammation-induced osteoclastogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 158–168 (2006).

Brinkmann, V. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303, 1532–1535 (2004).

Fuchs, T. A. et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell Biol. 176, 231–241 (2007).

Winstel, V., Missiakas, D. & Schneewind, O. Staphylococcus aureus targets the purine salvage pathway to kill phagocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6846–6851 (2018).

von Kockritz-Blickwede, M. & Winstel, V. Molecular prerequisites for neutrophil extracellular trap formation and evasion mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Immunol. 13, 836278 (2022).

Mohammad, M. et al. The role of Staphylococcus aureus lipoproteins in hematogenous septic arthritis. Sci. Rep. 10, 7936 (2020).

Geiger, T. et al. The stringent response of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on survival after phagocytosis through the induction of intracellular PSMs expression. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1003016 (2012).

Dalpke, A., Frank, J., Peter, M. & Heeg, K. Activation of toll-like receptor 9 by DNA from different bacterial species. Infect. Immun. 74, 940–946 (2006).

Nguyen, M. T. et al. The νSaα specific lipoprotein like cluster (lpl) of S. aureus USA300 contributes to immune stimulation and invasion in human cells. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004984 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft the Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2124—390838134 “Controlling Microbes to Fight Infections” to F.G., grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish Government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement grant number ALFGBG-823941 to T.J., N.L. was supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council. We are grateful to Stefanie Krajewski, Clinical Research Laboratory, Department of Thoracic, Cardiac and Vascular Surgery, University Hospital Tübingen, 72076 Tübingen, Germany, for providing us with SAOS-2 cells. S.E. received funding from the German Research Council (EH471/5-1). The funders had no role in design, analysis, and reporting of the study. A.W. received funding from the DFG Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 156 “The skin as a sensor and effector organ orchestrating local and systemic immune responses” (project B05) and DFG Priority Programs SPP 2225 “EXIT Strategies of Intracellular Pathogens” (projects 446404928 and We-4195/25-1). We acknowledge support by Open Access Publishing Fund of University of Tübingen.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.G., N.L. designed the study and the experiments; T.J., M.V.D. designed and carried out the septic arthritis model; F.S., S.E., A.N., and N.L. carried out neutrophil experiments; N.L., N.H. constructed deletion mutants; N.L., A.V.A., and A.W. carried out cell lines experiments; F.G., N.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Mohini Bhattacharya and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Christopher LaRock and Mengtan Xing. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Deshmukh, M.V., Sahin, F. et al. Staphylococcus aureus thermonuclease NucA is a key virulence factor in septic arthritis. Commun Biol 8, 598 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07920-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07920-4

This article is cited by

-

Advancing virulence factor prediction using protein language models

BMC Biology (2025)