Abstract

Stroke is one of the major causes of mortality and long-term disability worldwide. Chronic-kidney-disease (CKD) is a condition where patients have shown increased vulnerability to stroke with poor functional and cognitive outcomes. Impaired cerebral autoregulation in CKD patients may impose a high risk of stroke. To date, the mechanism of worsened stroke outcomes in CKD patients are limitedly understood. Alterations of endoplasmic-reticulum (ER) homoeostasis via modification of Sel1L-Hrd1 complex is one of the many cellular events that gets triggered following both CKD and stroke leading to accumulation of misfolded proteins, culminating in ER-stress. Therefore, the present study aims to explore the involvement of Sel1L mediated altered ER functions towards worsening of stroke outcome in CKD and further its crucial role towards white matter damage. CKD-stroke complex was induced in male Sprague-Dawley rats followed by middle-cerebral-artery occlusion. At 24 h and 7th day of reperfusion, animals were subjected to behavioral analysis followed by euthanasia, brain harvest and molecular studies. CKD-Stroke-complex animals showed aggravated neurofunctional and cognitive impairment which were further normalized by treatment of an ER-stress inhibitor. This indicates exacerbated stroke outcome in CKD-stroke-complex may be mediated by imbalanced ER-homeostasis due to decreased Sel1L expression leading to enhanced cellular death and neurodegeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is one of the global leading causes of neurobehavioral dysfunction that can result in long-term motor and behavioral impairments as well as mortality1. Individuals with prior underlying comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, and diabetes, are reported to have increased vulnerability as well as poor outcomes following stroke2. Various clinical studies have identified chronic kidney disease (CKD) as one of the potential risk factors for stroke2,3. Many factors, such as increased uremic toxins in blood, hypertension, hyperhomocysteinemia, atrial fibrillation, endothelial dysfunction, impaired cerebral autoregulation, and accelerated arteriosclerosis are reported to have a direct impact on increased stroke risk underlying CKD2,3. To date, stroke preventive measures taken in CKD patients are similar to that followed as conventional stroke treatment in patients having no predisposed pathology4. Therefore, there is an unmet need for specific interventions to reduce stroke susceptibility in CKD patients4. Apart from this, early detection of stroke risk associated with CKD is also crucial that may reduce mortality2. Thus, it is important to investigate the molecular mechanisms towards CKD-mediated exacerbation of stroke pathology and its outcomes.

In CKD, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is reported to play an important role which drives mitochondrial dynamics leading to activation of stress induced mitochondrial hyper fusion5. Sustained ER stress in acute stage of kidney injury can influence CKD progression culminating to progressive loss of renal function. ER stress in CKD can promote collagen deposition and fibrotic damage resulting in disruption of renal tissue architecture5.

Following stroke, mitochondrial dysfunction occurs which reduces adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production1,6. As a result, ATP-dependent biochemical reactions, such as protein folding and post-translational modifications are hindered7. These unfolded/misfolded proteins remain within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen leading to excessive ER stress which is detrimental for cell survival7. ER stress is counterbalanced by unfolded protein response (UPR) which reduces the misfolded protein load via ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway8. Under normal conditions, a balance between ER stress and ERAD maintains ER homeostasis. However, in pathological conditions, ER homeostasis gets altered that perturbs normal cellular functions8. Various ER stress markers have been reported to be upregulated in both CKD and stroke and linked with poor outcomes7,9. Therefore, it is of interest to understand how impaired ER homeostasis can worsen stroke outcomes in CKD patients.

Neurocognitive impairment is observed in both CKD and stroke patients, However, individuals having both the pathologies exhibits exacerbated cognitive impairment10. Following stroke, white matter damage has been reported to contribute towards post-stroke cognitive impairment. However, in CKD, the intricate mechanism of cognitive impairment is less understood11. White matter damage is closely associated with loss of myelin, which further contributes to cognitive decline12,13. The ERAD machinery utilizes the Sel1L-Hrd1 complex which plays a crucial role in the removal of misfolded/unfolded proteins to attenuate ER stress14. Hence, enhanced ERAD following stroke induced white matter damage may decrease myelin production from oligodendrocytes. Therefore, a possible association between white matter damage, decreased myelin production, and exacerbated poor cognitive outcome in CKD-stroke complex can be contemplated. Thus, our goal is to investigate the role of altered ER homeostasis in progression of CKD-stroke complex pathology towards white matter damage, poor functional outcome and associated cognitive decline.

In the present study, we have found that aggravated neurofunctional impairment in CKD-Stroke complex is regulated by impaired ER homeostasis. This impairment is influenced by Sel1L protein. Therefore, modulation of Sel1L mediated impaired ER homeostasis may play a promising role in better stroke management in CKD patients.

Results

CKD-stroke complex model validation

The developed LC-MS/MS method was linear over the range of 0.2 to 20 μg/mL with an r2 value of 0.997. The method was validated for ensuring its accuracy and precision. The accuracy and precision were evaluated at four different quality control levels of lower limit of quantification (0.2 μg/mL), low-quality control (0.6 μg/mL), mid-quality control (8 μg/mL), and high-quality control (16 μg/mL). Intra-day and inter-day accuracy and precision values were within the acceptance limit of ±20% at LLOQ and ±15% at all other quality control levels. The extraction recovery was more than 85% with negligible matrix effect for the analyte and internal standard. Samples were found to be stable in the series of stability experiments including freeze-thaw, autosampler, benchtop, and stock solution stability studies. (Concentration of Hcy in rat brain of different groups and chromatograms are in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Adenine diet decreases body weight, renal clearance of creatinine, urea and uric acid, increases renal clearance of Albumin and increases serum cystatin c level

The proposed hypothesis is described in Fig. 1A and the summary of experimental design is described in Fig. 1B. 0.5% adenine diet significantly decreases body weight over 28 days (Fig. 2A). The urine levels of creatinine, urea and uric acid decreased significantly at 28 days as compared to 0th day (Fig. 2B–D). Albumin excretion in urine was increased at 28th day compared to 0th day adenine diet (Fig. 2E). Consequent significant increases in serum creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels were observed on the 28th day as compared to 0th day (Fig. 2F–H). The serum cystatin c levels were found to be significantly increased over 28 days as compared to 0th day (Fig. 2I).

A Once CKD occurs, it can increase homocysteine level in brain. As a result, stroke can happen. Hyperhomocysteinemia results in impaired endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis via decreased Sel1L expression leading to ER stress mediated halt in oligodendrocyte maturation. Therefore, it is hypothesized that, ER homeostasis perturbation can exacerbate white matter damage towards neurodegeneration in CKD-Stroke complex (Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/72a8jmq). B Summary of experimental design. (Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/jro512v).

Graphs represent A changes in body weight throughout 28 day-Adenine diet (n = 4 and 5 biologically independent animals). Changes in urine levels of- B Creatinine (n = 6 in 0, 7 and 14 days and n = 5 in 21 and 28 days biologically independent animals), C Urea (n = 6 in 0, 7 and 14 days and n = 5 in 21 and 28 days biologically independent animals), D Uric acid (n = 6 in 0, 7 and 14 days and n = 5 in 21 and 28 days biologically independent animals), E Albumin (n = 6 biologically independent animals). Changes in serum levels of- F Creatinine (n = 6 in 7 and 14 days, n = 5 in 0 and 21 days and n = 4 in 28 days biologically independent animals), G Urea (n = 6 in 7 and 14 days, n = 5 in 0 and 21 days and n = 4 in 28 days biologically independent animals), H Uric acid (n = 6 in 7 and 14 days, n = 5 in 0 and 21 days and n = 4 in 28 days biologically independent animals), and I Cystatin c (n = 5 biologically independent animals). J Concentration of homocysteine in brain of different groups (n = 5 biologically independent animals). K Representative H and E and Masson Trichome-stained kidney sections of healthy and CKD rats (scale bar 50 µm), L Representative TEM images showing structural perturbations of ER in different groups (scale bar 0.5 µm). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (image A–H)/Kruskal–Walis’s test (image I, J), and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.5.

Brain homocysteine (Hcy) level was increased in CKD-Stroke complex

In CKD+Stroke group, brain Hcy level was upregulated significantly as compared to Sham group. Although elevated, no significant increase of Hcy levels were found in Stroke and CKD group as compared to Sham group. The level was also found higher in the CKD+Stroke group as compared to Stroke group (Fig. 2J).

Adenine diet deposits 2,8- dihydroadenine (2,8-DHA) crystal and increases collagen in kidney sections

A visible deposition of 2,8-DHA crystals and collagen depositions were observed in the transverse sections of kidneys in CKD animals as compared to healthy animals (Fig. 2K).

CKD-stroke complex shows altered morphology of ER in brain sections

The morphology of endoplasmic reticulum in stroke and CKD groups of animals were visible distorted as compared to sham animals. The morphology was maximum distorted in the CKD-stroke group as compared to sham group (Fig. 2L).

CKD-Stroke complex enhances neurodeficit and motor functional impairment

The neurodeficit scores were significantly higher in stroke and CKD+Stroke group of animals as compared to sham animals. Animals in CKD+Stroke groups also showed significant more neurodeficit as compared to stroke group. The score was significantly reduced in 4PBA treated group in comparison to stroke groups (Fig. 3A). In the rotarod test, animals in stroke and CKD+Stroke groups showed significant less retention on the rotating rod as compared to Sham animals in all 5, 10 and 20 RPM speeds. The animals in CKD+Stroke group animals retained on the rotarod for significant less time as compared to Stroke groups also in all speeds. However, the 4PBA treated groups showed an increased retention time on the rotating rod as compared to Stroke and CKD+Stroke treated group. The forelimb grip strength was significantly decreased in the contralateral sides of Stroke and CKD+Stroke animals as compared to Sham animals. However, 4PBA administration has increased the grip strength as compared to Stroke and CKD+Stroke group. In both paws, the grip strength was significantly decreased in Stroke and CKD+Stroke groups as compared to Sham animals whereas, 4PBA treatment significantly increases the grip strength as compared to stroke and CKD+Stroke group (Fig. 3B, C).

Graph representing A neurodeficit score (n = 6 biologically independent animals), B rotarod test at 5 RPM, 10 RPM, 20 RPM (n = 5 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA and CKD + 4PBA groups and n = 3 in CKD + Stroke + 4PBA biologically independent animals). C Grip strength of ipsilateral forepaw, contralateral forepaw and both forepaws (n = 5 biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

CKD-Stroke complex enhances infarct size, decreases neuronal viability and disrupts histological morphology in brain sections

Animals in Stroke, and CKD + Stroke groups showed significant increase in infarct size as compared to Sham animals. The 4PBA treatment also decreased the infarct size as compared to stroke groups. Neuronal histoarchitecture and neuronal viability (expressed as neuronal count) were distorted and significantly decreased in the Stroke and CKD + Stroke groups, which were improved following 4 PBA administration (Fig. 4A–D).

A Representative TTC-stained brain section of different animals. B Graph representing percent relative infarct size. Data (n = 7 biologically independent animals) are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, C Representative H&E stained and Nissl-stained brain sections of different groups. Representative graph of D neuronal count (n = 8 in Sham, CKD, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups and n = 6 in Stroke and CKD + Stroke biologically independent animals), levels of E MDA (n = 6 biologically independent animals), F nitrite (n = 6 biologically independent animals), and G GSH (n = 9 biologically independent animals), following 24 h of MCAo. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

CKD-Stroke complex increases oxidative and nitrosative stress in the brain

The levels of brain lipid peroxidation and nitrite concentrations were significantly increased in Stroke, CKD and CKD + Stroke group animals as compared to Sham animals. 4PBA administration has decreased these levels as compared to Stroke animals. On the other hand, the GSH concentration of Stroke, CKD and CKD + Stroke groups were significantly lower than Sham group. Administration of 4PBA increased the GSH Concentration as compared to Stroke group, but the increase was nonsignificant (Fig. 4E–G).

CKD-Stroke complex increases the gene expression of ER stress and impairs ER homeostasis

Gene expression of ER stress markers such as- Eif2ak3, Atf6, and Ern1, apoptosis markers such as- Ddit3(CHOP) and Caspase12, ERAD marker Sel1L and neurotrophic marker BDNF were evaluated by RT-PCR. An enhanced expression of Eif2ak3, Atf6, Ern1, Ddit3(CHOP) and Caspase12 were observed in Stroke, CKD and CKD + Stroke group as compared to Sham group. Following 4PBA administration, a decrease in all these markers as compared to Stroke, CKD and CKD + Stroke groups were observed. The ERAD marker Sel1L and neurotrophic marker BDNF expressions were significantly decreased in Stroke, CKD and CKD + Stroke animals as compared to Sham animals, which was eventually increased following 4PBA administration (Fig. 5A–G).

Graphs of the mRNA expressions of A Eif2ak3 (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in CKD + Stroke group and n = 5 in CKD + Stroke + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), B ATF6 (n = 7 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA, CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, and n = 6 in CKD + Stroke group biologically independent animals, C ERN1 (n = 10 in Stroke, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA groups, n = 11 in Sham, CKD and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA biologically independent animals), D Ddit3(CHOP) (n = 7 in Sham, CKD, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA, CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 6 in Stroke group and n = 5 in CKD + Stroke group biologically independent animals, E Caspase 12 (n = 8 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA groups biologically independent animals, F Sel1L (n = 8 in Sham, CKD, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA, CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups and n = 7 in Stroke group biologically independent animals), and G BDNF (n = 6 in CKD, CKD + 4PBA groups, CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in CKD + Stroke and Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 3 in Stroke and n = 8 in Sham group biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5.

CKD-Stroke complex modulates the protein expression of ER stress, ERAD, apoptosis and neurotrophic factors

The protein expression of GRP-78, CHOP, ATF4, ATF6, teIF2α, peIF2α, caspase 12 and IRE1α, were significantly increased in Stroke, CKD, and CKD+Stroke groups as compared to Sham group. 4PBA administration decreases the protein expression as compared to Stroke group. Similarly, the protein expression of BDNF and Sel1l were decreased in the CKD-Stroke complex as compared to sham group and 4PBA administration increased the expressions as compared to stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke groups (Fig. 6).

A Representative immunoblots and graphs of B GRP78 (n = 8 biologically independent animals), C CHOP (n = 6 biologically independent animals), D ATF4 (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in CKD + Stroke group biologically independent animals), E ATF6 (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 5 in CKD + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), F teif2α (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 5 in CKD + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), G BDNF (n = 6 biologically independent animals), H pEIF2α (n = 6 biologically independent animals), I Sel1L (n = 6 biologically independent animals), J Caspase 12 (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in CKD + Stroke and Stroke + 4PBA groups biologically independent animals), K IRE1α (n = 6 biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. Sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

CKD-Stroke complex increases the nuclear localization of CHOP, autophosphorylation of PERK, limits oligodendrocyte maturation and neuronal development in brain sections

The nuclear colocalization of CHOP was significantly high in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke group animals as compared to Sham animals, enhanced phosphorylation of PERK and enhanced Olig1 expressions were found in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke animals as compared to Sham group. Expression of NeuN and Syntaxin-1 were found to be less in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke groups as compared to sham group. Administration of 4PBA normalized all these expressions as compared to Stroke and CKD+Stroke group animals (Fig. 7A–E, G–K).

Representative immunofluorescence images showing A the nuclear colocalization of CHOP. B pPERK expression, C Olig-1 expression, D NeuN expression, E Syntaxin-1 expression, F TUNEL positive cells (blue color indicates DAPI staining of nucleus and red color indicates apoptotic cells, scale bar 10 μm). Graph representing G Pearson’s Coefficient of Colocalization of CHOP/DAPI in the brain sections (n = 8 biologically independent animals), H Percentage area of pPERK immunofluorescence (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke, CKD + Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 3 in CKD group biologically independent animals), I Percentage area of Olig-1 immunofluorescence (n = 6 in Sham, Stroke + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 5 in Stroke group, n = 4 in CKD group, n = 8 in CKD + Stroke group, n = 7 in CKD + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), J Percentage area of NeuN immunofluorescence (n = 5 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, and CKD + Stroke groups, n = 6 in Stroke + 4PBA and CKD + 4PBA groups n = 7 in CKD + Stroke + 4PBA group biologically independent animals). K Percentage area of Syntaxin-1 immunofluorescence (n = 5 in Stroke, Stroke + 4PBA, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 4 in Sham and CKD + Stroke groups n = 3 in CKD group biologically independent animals), L TUNEL-positive cells/field (n = 6, biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. Sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

CKD-Stroke complex increased neuronal apoptosis

An enhanced TUNEL+ cells were observed in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke groups in comparison to Sham animals. The apoptosis was higher in CKD+Stroke group as compared to stroke animals. 4PBA administration reduces apoptosis as compared to stroke and CKD+Stroke groups (Fig. 7F, L).

CKD-stroke complex shows enhanced white matter damage, distorted tissue morphology, lesser neuronal count and decreased oligodendrocyte maturation at long-term

In a long-term study of 7 days, CKD-stroke complex showed enhanced white matter injury compared to Sham and stroke group as indicated by Luxol Fast blue staining. The tissue morphology was distorted, and neuronal count was still significantly low as compared to Sham groups. The oligodendrocyte markers such as Olig-1 shows significant increase in CKD-stroke complex as compared to Sham and Stroke group animals. The expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) was significantly low in CKD-Stroke group animals as compared to sham animals. All these expressions were normalized following 4PBA administration as compared to stroke group (Fig. 8A–F).

A Representative H&E stained, Nissl stained and Luxol fast blue stained brain sections of different groups. Representative images of protein expression immunofluorescence of- B Olig-1, C MBP. Graphs representing D neuronal count (n = 5 in Sham, Stroke, CKD, CKD + Stroke, CKD + 4PBA and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 6 in Stroke + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), E percentage area of Olig-1 immunofluorescence (n = 9 in Sham and CKD + 4PBA groups, n = 7 in Stroke and CKD + Stroke groups, n = 4 in CKD, n = 10 in Stroke + 4PBA, n = 6 in CKD + Stroke + 4PBA group biologically independent animals), F percentage area of MBP immunofluorescence (n = 5 in Sham, CKD and CKD + Stroke + 4PBA groups, n = 6 in Stroke and CKD + 4PBA groups, n = 4 in CKD + Stroke, n = 7 in Stroke + 4PBA group biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. Sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

CKD-Stroke complex impairs neurobehavior along with motor function and cognitive outcomes at long-term

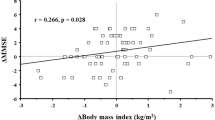

A high neurodeficit score, low retention time in rotarod and less contralateral forepaw grip strength were found in Stroke, and CKD+Stroke group animals at 1,3, and 7 day as compared to Sham group. The observation was reversed following 4PBA administration. Time spend in elevated plus maze closed and open arms were significantly increased and decreased respectively in stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke group animals as compared to Sham group. The %discrimination rate of novel object recognition test (NORT) was decreased in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke animals in all 3 time points as compared to Sham animals. %alteration of arms in Y maze study was significantly decreased in Stroke, CKD and CKD+Stroke groups animals in all time points as compared to sham group. Administration of 4PBA reversed these observation as compared to stroke and CKD+Stroke groups (Figs. 9 and 10).

Rotarod test at A 5 RPM, B 10 RPM, C 20 RPM (n = 6, biologically independent animals). Grip strength of D ipsilateral forepaw, E contralateral forepaw and F both forepaws (n = 9, biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

A Elevated plus maze-closed arm (n = 6, biologically independent animals), B Elevated plus maze-open arm (n = 6, biologically independent animals), C NORT (n = 6, biologically independent animals), D Y maze (n = 6, biologically independent animals). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed for statistical significance using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5 vs. sham; ###p < 0.001, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.5 vs. Stroke.

Discussion

CKD is one of the comorbid conditions in stroke, which has been reported to aggravate the stroke outcomes in clinics15,16,17,18. According to the prospective Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, CKD is defined as individuals with eGFR value less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2,3. Impaired kidney function has been reported to predispose 61.3 million of DALY’s. Among them, 58.4% were contributed by CKD and 40.2% of 25.3 million DALY’s were owed to impaired kidney disease resulted from stroke19. The risk of stroke is 5–30 times greater in CKD patients, specifically to those who are in dialysis. Moreover, post-stroke thrombolytic therapy in CKD patients has been reported to have greater risk of hemorrhagic transformation20. However, the molecular link between CKD and stroke exacerbation is limitedly explored. In a recent cross-sectional analysis of stroke patients with predisposed CKD condition reported an association of eGFR and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio with cerebrovascular disease related neurodegenerative changes21. As ER plays a crucial role in white matter damage and maintenance of myelination in any of the CNS pathology, thus it becomes imperative to decipher the molecular mechanism of aggravated outcomes in CKD-stroke complex targeting ER homeostasis.

Homocysteine (Hcy), an intermediate product of methionine metabolism is reported to be abnormally increased in plasma (hyperhomocysteinemia) in CKD conditions22. Patients suffering from CKD has been reported to have hyperhomocysteinemia due to reduced GFR and absorption of Hcy, since it is bound to albumin by covalent bonds23. Neurons rapidly take up Hcy by specific synaptosomal plasma membrane transport system and fails to metabolize it by betaine remethylation and transsulfuration24,25. This makes cerebral tissue specifically vulnerable to hyperhomocysteinemia. Hcy acts as an excitatory amino acid for N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, thus during blood-brain barrier disruption in stroke, elevated levels of Hcy leads to excitotoxicity of NMDA receptors26,27. In our study, the Hcy levels in the brain tissue was compared between Sham, Stroke, CKD and CKD-stroke complex animals. Interestingly, an elevated brain homocysteine level was observed in the CKD-Stroke complex animals compared to sham, CKD and stroke animals. This indicates that hyperhomocysteinemia may be crucial towards stroke risk in CKD. Studies report that Hcy can also activate group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) leading to activation of the downstream cascade of protein kinase C/ IP3 formation mediated sensitization of ER towards intracellular calcium26. It enhances the ER stress by upregulating the chaperone and non-chaperone proteins26 resulting in morphological perturbation of ER. Similar observations were found in the present study where the cellular ultrastructure was observed where altered morphology of ER structure was noticed.

ER homeostasis plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular health28. It maintains a balance between ER stress mechanism and ERAD system28. Imbalance of this mechanism is reported in various pathological conditions including CKD and stroke. Homocysteinemia is also reported to interfere ER homeostasis leading to impaired cellular function. Therefore, we investigated the involvement of ER homeostasis disruption in CKD-stroke complex, by interrupting the balance by ER stress inhibitor29.

Neurofunctional impairments are well reported in both CKD and stroke conditions. We observed that neurofunctional deficits, motor co-ordination impairment, increased infarct size, decreased neuronal viability, and altered brain tissue morphology in CKD-stroke complex. An improvement in functional outcomes were observed following administration of 4PBA in stroke, CKD and CKD-stroke complex animals indicating the involvement of the ER stress mediated neurodegeneration.

Presence of Hcy has been known to subsequently lead to oxidative stress, that is further aggravated by the chronic ER stress condition in stroke26. Elevated MDA and nitrite levels were observed in the CKD-stroke complex animals while the levels were significantly decreased in the 4-PBA treated groups. The level of GSH, an antioxidant, was significantly increased in the 4-PBA treated groups as compared to the untreated groups.

The ERAD mechanism is primarily mediated by HRD1-SEL1L complex formations, which are involved in removal of the unfolded proteins which is triggered during ER stress condition30. In pathological conditions, SEL1L expression gets downregulated leading to impaired ERAD function. We observed, the gene and protein expression of SEL1L to be significantly decreased in CKD-stroke complex, which was further increased in the 4-PBA treated groups. This gives a preliminary hint toward the involvement of impaired ERAD mediated clearance as one of the key pathological players of CKD-stroke complex.

The UPR is sensed by three transmembrane sensor proteins, also known as ER stress arms, viz, PRKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) α, and inositol-requiring protein 1 (IRE1) α present in the luminal domain of ER. Among them, PERK is majorly linked with global translation inhibition, antioxidant response, and mitochondrial bioenergetics demand31. Once PERK is activated, it phosphorylates eIF2α which selectively induces transcription factor ATF4 and ultimately results in CHOP-mediated apoptosis31,32. The actively involved UPR transducer Atf6 and the protein kinase Ern1 (IRE1) gene and protein levels were observed to be significantly upregulated in the CKD-stroke group which were further downregulated following 4-PBA administration. To further explore the involvement of ER stress in CKD-stroke complex, we evaluated the gene expression of Eif2ak3 and its corresponding phosphorylated protein pPERK in the brain tissue. Interestingly, the gene level was not significantly increased in the CKD-stroke complex compared to stroke group in singlet, however, the gene expression was significantly increased when compared to CKD group. On the other hand, the autophosphorylation of PERK protein was significantly increased in CKD+Stroke group in comparison to both stroke and CKD groups. This indicates the rapid activation of PERK pathway because of ER stress which may aggravate the stroke outcome in CKD conditions. The glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) is ER stress sensing chaperone that guides the cell towards apoptosis, which has been reported to be involved in Hcy mediated ER stress condition33. The consequent apoptotic markers and levels of apoptosis were also increased in the CKD-stroke complex and their downregulation following 4PBA administration gives a clear indication of the involvement of ER homeostasis alteration as a crucial molecular player of CKD-stroke pathology.

Hcy has been extensively reported to have severe cognitive declining effect, thus associated to increased risk of dementia and stroke34. BDNF, a neurotrophin that has been known to have neuroprotective effect by reducing ER stress and improving neuroplasticity. In a study, inhibiting the action of Hcy was observed to increase the expression of BDNF, and eventually imparting neuroprotective effect35. The protein synthesis pathway was also hampered and indicated by reduced gene and protein expression of BDNF in CKD-stroke complex. BDNF has been reported to enhance maturation of oligodendrocytes and leading to white matter differentiation by enhancing the expression of Olig1 and MBP36,37. In the current study, we have observed that decreased BDNF expression in CKD-stroke complex that might hamper the oligodendrocyte differentiation, neuronal maturation and myelin formation leading to enhanced white matter injury. In long-term, the 4PBA treatment helped in oligodendrocytes maturation as evident from the expression of myelin basic protein in the corpus callosum of ipsilateral hemisphere. The cognitive behavior impairment was also observed to be improved following ER stress inhibitor administration which clearly indicates the involvement of ER homeostasis in maintaining white matter injury.

Earlier studies of our lab have reported the involvement of ER stress in stroke38,39,40,41,42,43. in the present study reports that, stroke in predisposed CKD condition can exacerbate the disbalance of ER homeostasis which aggravates the stroke outcome as well as white matter injury leading to neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction. As comorbid conditions are closely associated to the genetic as well as somatic factors of the individuals, further studies related to the genetic predisposition of various other factors needs to be performed. A gender disparity study is also solicited as hormonal controls are closely related to the blood clotting mechanism and kidney functions. Moreover, compared to any other surgical model of induction, the present CKD-stroke model has lesser mortality rate, and a higher reproducibility. Therefore, imbalance in ER homeostasis influenced by Sel1L may be one of the major molecular links towards increased white matter injury and exacerbated neurodegeneration in CKD-stroke complex.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Unless specified otherwise, kits, reagents, and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Invitrogen, and Abcam. The usage was carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Homocysteine and 4-methyl-o-phynylenediamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Analytical grade solvents and reagents namely methanol, acetonitrile, formic acid, and ammonium formate were purchased from Fischer scientific.

Animals

The study was carried out using male Sprague Dawley rats, weighing between 250–280 g. All in vivo experiments were carried out in conformity with the Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA) guidelines and were conducted with permission from the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of NIPER-Ahmadabad. The animals were obtained from either NIPER-Ahmedabad’s in-house animal breeding facility or from CCSEA-approved commercial breeding agencies. The approved IAEC numbers are: NIPERA/IAEC/ 2019/010;2020/004;/2021/031. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. The rats were subjected to the studies after being quarantined for five to seven days in individually ventilated cages at 25 ± 0.5 °C and 60 ± 5% relative humidity (12 h of alternate light and dark cycles). Within the quarantine period, rats were fed a standard pellet diet and had free access to clean water. Randomization was used to assign the animals in various groups and evaluate the results by investigators blinded to the study.

Experimental design

All animals were divided into seven groups via randomization, viz., Sham (n = 25), Stroke (n = 35), CKD (n = 22), CKD + Stroke (n = 40), Stroke + 4PBA (n = 29), CKD + 4PBA (n = 25), CKD + Stroke + 4PBA (n = 30). During the study, ten animals were dead, and 46 animals were excluded due to artery perforation, nonsignificant neurodeficit score, non-significant alterations of brain oxygenation and cerebral blood flow, small or no infarct, aberrant physiological parameters, and high glucose level. 4PBA was administered at a dose of 200 mg/kg body weight thrice a day with feed (equivalent to 1.2 g/kg mixed with feed)44. Animals were divided into five different panels for molecular and biochemical studies, histological studies, LC-MS studies, TEM studies and long-term behavioral studies. Following the study, animals were euthanized as per approved protocol. Next, brains were harvested and subjected to further molecular studies. To perform histological study, animals were euthanized by Transcardial perfusion using chilled saline. Further, brains were fixed with formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned using microtome instrument. Following MCAo surgery, post-operative care was done by saline infusion, body temperature maintenance, analgesia, liquid diet supply, and closed monitoring of the animals placed in individual ventilated cages. All experiments were performed in a blind manner while the allocation of different groups and their functional assessments.

CKD-Stroke complex model induction

Induction of chronic kidney disease

Rats were fed a diet containing 0.5% adenine mixed in normal food pellet for 28 days to create the experimental CKD model45,46. When adenine is ingested orally, its poorly soluble metabolite 2,8 dihydroxyadenine (2,8 DHA) builds up and precipitates and crystallizes in tubules and microvilli, causing podocyte injury, fibrosis, collagen deposition, and the start of an inflammatory cascade mimicking an advanced diseased stage47,48.

Validation of CKD model

Starting from the day of CKD induction, urine and blood (retro orbital route) was collected every 7 days for 28 days. Serum was then separated by centrifuging the clotted blood at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The separated serum and urine were then used for determining level of creatinine, uric acid, urea and urine albumin. Urea content was estimated using a commercially available urea assay kit. The urease enzyme hydrolyzes the urea found in serum and urine to produce ammonia, which then combines with the phenolic chromophore to form a complex that is green in color. The intensity of green colored complex is directly correlated with the amount of urea in the serum and urine. The Bioanalyser was used to detect the absorbance at 570 nm, providing the quantities in mg/dl49. Elevated serum creatinine levels suggest renal failure. Creatinine tests determine glomerular filtration rate as well as the amount of creatinine in the serum or urine. Picrate Jaffe’s reaction was used to assess the serum and urine creatinine level using commercial assay kits (Identi kit). The amount of creatinine in the serum or urine is directly correlated with the intensity of the orange-colored complex that is produced when creatinine interacts with picric acid in alkaline condition. Bioanalyser was used to measure the absorbance at 520 nm50. Using the readily available assay kit (Identi kit), the Uricase method was used to evaluate the amount of uric acid. When uric acid and uricase combine, allantoin and H2O2 are produced which further reacts with phenol, and the intensity of the red colored complex that develops is used to calculate the creatinine concentration. The Bioanalyser was used to measure absorbance at 520 nm51. Albumin level in urine was measured using commercially available albumin assay kit (identi). Albumin and bromocresol green react at a specific pH to form a colored complex, which was detected in bioananalyser at 630 nm.

Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo)

To induce CKD-Stroke complex, MCAo was performed on the 29th day following completion of the adenine diet. All surgical techniques were carried out in accordance with earlier research with few minor modifications38,39,40,41,42. The animals were intubated and ventilated using Harvard instruments after anesthetizing with gas anesthesia (isoflurane/oxygen, 4% during induction and 1.5% during maintenance). The animals’ blood glucose was checked using a glucometer (One Touch® Glucose Strips) before the surgery. Laser Doppler flowmetry (AD Instruments) was performed to measure cerebral blood flow in addition to continuous monitoring of brain and rectal temperatures. Near-infrared spectroscopy (Moor VMS-NIRS monitor), was employed for monitoring the Regional Cerebral Oxygen Saturation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Arterial blood was drawn before to, during, and after surgery via cannulation of the right femoral artery using PE-50 catheters (from BD Bioscience) in order to evaluate blood gas parameters such as pH, pO2, and pCO2 using a blood gas analyzer (Radiometer) (Supplementary Table 2). Using silicone-coated nylon filament (Doccol Corp.), the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) was blocked for 90 min to cause focal cerebral ischemia in rats38,39,40. The animals received appropriate post-operative care, including analgesics to reduce pain. Similar surgical isolations were performed on the sham animals, but the filament was not inserted.

Estimation of homocysteine (Hcy) in the brain by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Preparation of stock solution, calibrants and quality control samples for LCMS

The primary stock solution of Hcy (1000 µg/mL) and 4-methyl-o-phynylenediamine (internal standard: IS) (100 µg/mL) were prepared in methanol. A 0.1% v/v formic acid solution was added while preparing the working stock solutions of the analyte. Calibration standard solutions of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 µg/mL were prepared by serially diluting the primary and working standards. The working solution of 4-methylene-o-phynylene diamine was prepared by diluting the primary stock to prepare a 0.5 µg/mL solution. Three quality control solutions namely low-quality control (0.6 μg/mL), mid-quality control (8 μg/mL), and high-quality control (16 μg/mL) were also prepared after serial dilution of the respective working solutions.

Brain tissue homogenate preparation

Rat brain (Sprague Dawley) was obtained, cerebellum was removed, minced and then weighed. 2% formic acid in water as a homogenizing solution was added in the ratio of 1:5 i.e., 500 µL solution in a 100 mg brain sample. Homogenization was done by TissueLyser LT® for 15 min. The content was then centrifuged for 30 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at 80 °C.

Sample extraction for brain homogenates

A simple protein precipitation technique using methanol was employed for extraction of HCY from brain tissue homogenate. The brain tissue homogenate (100 µl) was taken in a micro-centrifuge tube added with 20 µl of IS solution along with 10 µL of 0.1% formic acid, and vortexed for 20 s. Thereafter, 200 µl of methanol was added, vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C, supernatant was collected and injected into the LC-MS system for analysis.

LC-MS/MS parameters

The chromatographic separation was achieved using a Biphenyl (Kinetex, 3 x 150 mm, 2.6 μm) column with the mobile phase 0.1% formic acid:methanol (30:70) at 0.5 mL/min. The injection volume for the sample was 5 μL. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for HCY and IS were optimized as m/z 136 → m/z 90 and m/z 123→m/z 106, respectively. Compound-dependent and source-dependent parameters were optimized through tuning after infusing the Hcy and IS. The declustering potential, entrance potential, collision energy, and collision cell exit potential were set at 59 V, 10 V, 17 V, and 15 V, respectively. For IS, declustering potential, entrance potential, collision energy, and collision cell exit potential were 106 V, 10 V, 27 V, and 15 V, respectively. Source-dependent parameters namely ion spray voltage, temperature, ion source gas 1, ion source gas 2 and curtain gas were optimized at 5500 V, 400 °C, 40, 40, and 40 psi, respectively. Retention time of HCY and IS was about 1.31 min and 1.39 min, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging

Transcardial PBS perfusion was performed, and brains were fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight. Next, they were subjected to 1% OsO4 treatment, washed in acetone for dehydration, infiltered and embedded in Araldite CY 212 (TAAB, UK) for further sectioning. Eighty nm sections were cut with gray-silver color interference following mounting onto 300 mesh copper grids. Further the sections were stained in alkaline lead citrate and aqueous uranyl acetate. Finally, they were observed under a Tecnai G2 20 high-resolution transmission electron microscope (Fei Company, The Netherlands). The operating voltage of 200 kV was maintained. Images were acquired using Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc.) software attached to the microscope52. (Acknowledgement: Sophisticated Analytical Instrumentation Facility (SAIF), AIIMS, New Delhi, for sample processing and image acquisition).

Behavioral assessment

Behavioral assessments were conducted at 1, 3, and 7 days after reperfusion, in compliance with our earlier reports38,39,41,42. The neurodeficit scoring was done using a 12-point scaling system. Postural reflex, visual and tactile placement test, and proprioception was evaluated. On this scale, a score of 0 indicated the least impaired neurological response, while a score of 12 indicated the maximum loss of neurological function53.

Rotarod and grip strength

Using an electronic grip strength meter, rats’ forepaw grip strength after surgery was assessed. Peak force (N), produced by the animal’s paw gripping a sensor-connected mesh was used to measure the motor strength of the animal. Measurements of post-stroke grip strength were made at 1 day after reperfusion, while a baseline was made an hour before surgery38,39,40,42,54. A rotarod motor test (Rotamex, Columbus Instruments) was used to evaluate motor coordination. The animals are put through three trials with a 180-s cutoff time. During each trial, they try to walk on the spinning rod at 5, 10, and 20 revolutions per minute (RPM) with 10 min of rest in between. At every speed, the retention time on the rod is noted. In addition to baseline testing conducted an hour before surgery, the animals undergo training and acclimatization on the rod for three days before the procedure. Post-stroke data was also collected at 1 day after reperfusion38,39,40,42,54.

The novel object recognition test (NORT) and the Y-maze

These tests were used to assess cognitive function. The animals used in the Y maze test were put in the middle of the maze and given complete freedom to wander around. For 5 min, the number of entrances into the arms and alterations were recorded. For 2 days prior to surgery, the animals in the NORT experiment were acclimatized to the open arena for 5 min each day. On the day of surgery Animals were given two identical things (same heights and forms) in the open arena, and they were given 5 min to explore (familiar objects). One object will be swapped out for a novel one after 30 min that is comparable in height but different in shape. The amount of time spent exploring the novel object and the familiar object will be recorded.

Post-stroke depression like behavior was measured using the elevated plus maze (EPM)

Rats were allowed to explore the arms (2 open and 2 closed arms) for 5 min, following positioned in the middle. Time spent in open and closed arms was recorded. EPM, NORT and the Y-maze experiments were performed at 1,3, and 7-day post-surgery.

Quantification of cerebral infarct size

In brain matrix (RWD Lifesciences), 2 mm coronal sections of the brain were cut out, and they were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in 1% 2,3,5-Tetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution in 0.1 M PBS. 4% paraformaldehyde was then used to fix the stained sections. In contrast to the non-viable zone, which was colorless, the viable sections were stained red. After the sections were imaged, the percentage relative infarct size was calculated using NIH ImageJ software38,39,40,42,53.

Histological assessment

After the stroke, the rats were transcardially perfused with ice-cold normal saline at days 1, 3, and 7, and then with 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF). Using a tissue embedding machine (Thermo Scientific, Histostar), the collected tissues were treated in alcohol gradients and then embedded in paraffin media (from Leica Surgipath). The Leica HistoCore MULTICUT microtome was used to cut sections measuring 20 and 10 μm. Nissl stain and Luxol fast blue (LFB) stain was used on the 20 μm sections and haematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stain was used on the 10 μm sections. The sections were stained in accordance with the techniques we previously described. After deparaffinization, the sections were soaked in 100% alcohol for 1 min, Harris Haematoxylin solution for 10 min, and Eosin Y stain for 1 min. For Nissl staining, the sections were incubated in pre-warmed 0.1% cresyl violet in acetate buffer (pH 3.6), for 15 min before being dehydrated and treated with differential medium (equal parts ethyl alcohol, ether and chloroform). The neuronal counting was performed using the particle analyzing application of the NIH ImageJ software, which was based on previously published studies with minor modifications55. For LFB staining sections were delipidized in chloroform and then hydrated using 100% and 95% ethanol respectively. Sections were then incubated in LFB staining solution for 2 h at 60 °C followed by rehydration in gradient concentration of alcohol and finally water. Differentiation was performed using 0.05% lithium carbonate solution and 70% ethanol alternatively. Counter staining was then performed using cresyl violet for 2–3 min followed by washing, dehydration and mounting. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed on kidney sections to confirm the presence of collagen fibers prevalent in CKD. For 1 h, slides were incubated in a warmed Bouin solution (54–60 °C). The sections were then washed with water after cooling at room temperature. After incubating in Weigert’s iron haematoxylin for 5 min, the slides were again washed with water. Stained sections were then differentiated using phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid after being treated in acid fuschin for 15 min. Following a 5-to 10-min incubation period in aniline blue, the slides were next incubated for 3–5 min in acetic acid. Afterwards, alcohol was used to dehydrate the sections before mounting them. The stained slides were mounted with Dibutylphthalate Polystyrene Xylene (DPX) and photographed under a light microscope (Leica DM 750)38,39,41,42.

Tissue lysate preparation

The ipsilateral coronal brain tissue weighed between 75 and 100 mg, and it was homogenized in chilled condition using a micropestle with 1 ml of either extraction buffer (used for nitrite and malondialdehyde quantification) or radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) solution containing protease inhibitor. After being sonicated, the samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 × g (4 °C). Using the bicinchoninic acid assay (PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit), total protein concentration of the lysate was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 562 nm53,54.

Biochemical estimations

All biochemical procedures were carried out with minor alterations in accordance with previously published research54. The thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay was used to measure the amounts of malondialdehyde (MDA) in order to determine the degree of lipid peroxidation in the samples. The sample was treated with a solution of glacial acetic acid (20% v/v), sodium dodecyl sulfate (8.1% v/v), and thiobarbituric acid (0.8% w/v) before being incubated for 1 h at 95 °C in a water bath. Using spectrophotometry, the absorbance was determined at 532 nm, and the concentration was expressed as μM/mg of protein42,53. The Griess method was used to estimate the nitrosative stress and determine the amount of nitrite present in the samples. The samples were treated in a 1:1 ratio with Griess working reagents A (0.1% naphthyl ethylenediamine) and B (1% sulfanilamide in 5% orthophosphoric acid), and they were then left to incubate for 30 min at room temperature. Once the samples have been incubated, they are plated in a 96-well plate and subjected to spectrophotometric observation at 540 nm, with findings expressed as μM/mg of protein42,53. Ellman’s DTNB reaction in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was used to estimate GSH, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 20 min at 45–50 °C in a water bath. After measuring the sample’s absorbance at 412 nm, the results were expressed as μM/mg of protein42,56.

RNA isolation and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT‑PCR)

Gene expression of Atf6, Ern1, Eif2ak3, CHOP, Caspse12, BDNF, Sel1L were analyzed by RT-PCR method. According to our previously published research, the RNA was isolated from cortical brain tissue using the TRIzol method using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Cat. no. 15596026). Using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), the 260/280 ratio was used to evaluate the quality of the extracted RNA. Using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad), the cDNA was synthesized in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The gene expressions were measured using a Real-time PCR machine (CFX Real Time-PCR, Bio-Rad) and SYBR® Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad). 18S rRNA (endogeneous control) expression was used to normalize the gene expression of Atf6, Ern1, Eif2ak3, Ddit3(CHOP), Caspase12, BDNF, and Sel1L (Sigma Aldrich, KiCqStart Primer) (Primer sequences Supplementary Table 3). The 2−ΔΔCt method was utilized to calculate the relative change in expression54,57.

Western blotting

Thirty µg of protein-containing sample was added in Laemmli buffer and denatured in a dry bath at 100 °C for 5 min. Depending on their molecular weights, the protein bands were separated in various SDS-PAGE gels (8%–14% polyacrylamide gel). Running buffer comprising glycine (250 mM), SDS (0.1%), and Tris (25 mM) was used for electrophoresis. Using the semi-dry gel transfer method (Trans-Blot® TurboTM Transfer System, BioRad), proteins were transferred from the gel to methanol-activated Bio-Rad PVDF membranes for immunoblotting. After that, the protein-containing membrane was blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 5% bovine serum albumin in 1X Tris-Buffered Saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST). After TBST wash, the membranes were left overnight at 4 °C to be incubated with primary antibodies against Caspase 12 (1:1000; ab62484), peif2α (1:1000; PA5-118533), Total eif2α (1:1000; sab4500729), CHOP (1:500; ab11419) and ATF6 (1:1000; SAB5700037), sel1L (1:1000; PA5-88333), GRP-78(1:1000; SAB5700613), BDNF (1:1000; ab108319), ATF4 (1:1000; ab23760), IRE1 alpha (1:1000; PA5-20189) and normalized to β actin (1:10,000; ab6276). Following the initial incubation, the membranes are soaked in TBST on the following day and subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP conjugated goat anti-rabbit (ab6789) and goat anti-mouse (ab6721) at a dilution of 1:10,000 (details of antibodies used are provided in Supplementary Table 4). Following the secondary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed with TBST and examined using the enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL, Bio-Rad) in the gel doc system (Bio-Rad). NIH ImageJ software was used for densitometry analysis to quantify the protein bands58,59.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was performed for measuring the level of Cystatin C in the serum samples as per manufacturer’s instruction. For the experiment Rat Cystatin C ELISA Kit (Thermo Fisher scientific: ERCST3) was used and manufacturer’s protocol was followed. Briefly, 100 µl of the separated serum (diluted 4 times) was added in wells and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day contents of wells were discarded and washed 4 times with 1x wash buffer and biotinylated antibody (80 times diluted) was added. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, contents were discarded and washed 4 times before addition of Streptavidin-HRP solution (incubated for 45 min at room temperature). Then 100 µl TMB substrate was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature following 4 times washing. Fifty µl of stop solution was then added to stop the reaction and absorbance was taken at 450 nm within 15 min.

Immunofluorescence

Protein immunofluorescence in 10 μM brain slices was carried out using techniques somewhat modified from previously published works58,60,61. For clarification, the slides were heated and then incubated in xylene to deparaffinize the microtome slices. After the alcohol gradient dehydration stage, heat-mediated antigen retrieval with sodium citrate buffer and 4% BSA blocking in 1% TBST were performed (for 30 min in the 0.3 M glycine solution and 90 min in the glycine-free solution). The sections were then incubated with the primary antibodies: anti-CHOP (1:200; PA5-88116), anti-phospho-PERK (1:100; MA5-15033), anti-Olig1 (1:500; PA5-21613), anti-MBP (1:100; Bioss-BS0380R), anti-NeuN (1:200; ab104224) and anti-Syntaxin-1 (1:200; MA5-17612) at 4 °C overnight after being washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The primary antibodies were diluted 1:100 or 1:200 in PBS. After rinsing the sections, the following day with 1X PBST (containing 0.1% Tween 20), they were incubated for 1 h at room temperature (avoided direct exposure to light) with the respective secondary antibodies, Alexa Flour® 488 and Alexa Flour® 555 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor® 647 goat anti-mouse. After that, the protein was counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (1 μg/ml) for 5 min and mounted with a coverslip. High resolution images of the treated sections were obtained using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope; Leica TCS SP8 Microsystems), and ImageJ, an NIH program, was used for analysis58,60.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

A TMR Red, In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, 12156792910) was used to perform the TUNEL assay in 10 μM brain slices to measure the degree of apoptosis. 4% paraformaldehyde was used to fix the tissue sections, and alcohol was then used for dehydration. Sodium citrate buffer was used for heat-mediated antigen retrieval after the tissue was permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X solution. The TUNEL enzyme solution was then added, and after 60 min at 37 °C in a dark, humid chamber and DAPI labeling, TUNEL-positive cells were visualized as red fluorescence nuclei at 580 nm (using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope; Leica TCS SP8 Microsystems)58,62.

Statistics and reproducibility

Every available data point is shown as mean value ± Standard Deviation (SD). To look at the statistical differences between groups, GraphPad Prism version 9 (San Diego, CA) was used. For sample numbers more than 3, one-way and two-way ANOVA were applied along with Tukey’s, Kruskal Wallis and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests unless and otherwise specified. For all experiment sample numbers of each group were minimum 3 and maximum 11. If a p value of less than 0.05 was found, statistical significance was confirmed in every instance. ’Lenth, R.V (2006). Java Applets is used for power and sample size analysis (Computer software)63.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Conclusion

CKD is attributed to an aggravated stroke. Our study reports that the exacerbated neurofunctional outcome as well as cognitive impairments in CKD-stroke complex are majorly regulated by impaired ER homeostasis influenced by Sel1L. Thereby, modulating ER stress and ERAD pathway, can pave a new therapeutic opportunity for better management of stroke in CKD patients.

Data availability

All data of the study are included in the current manuscript and its Supplementary files. Preliminary and additional data of the study and all uncropped blots (Supplementary Fig. 3) are available in Supplementary Material. The source data are available in Supplementary File 1. Full statistical details are available in Supplementary File 2. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

No original custom code was developed within this work. Only previously published and open-access software was used following developer’s instructions, cited and described in detail under the relevant method subsections and Supplementary notes.

References

Sarmah, D. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in stroke: implications of stem cell therapy. Transl. Stroke Res. 10, 121–136 (2019).

Shah, B. et al. Cerebro-renal interaction and stroke. Eur. J. Neurosci. 53, 1279–1299 (2021).

Abramson, J. L., Jurkovitz, C. T., Vaccarino, V., Weintraub, W. S. & McClellan, W. Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: the ARIC Study. Kidney Int. 64, 610–615 (2003).

Ghoshal, S. & Freedman, B. I. Mechanisms of stroke in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 50, 229–239 (2019).

Ricciardi, C. A. & Gnudi, L. The endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in kidney disease: implications for vascular growth factors. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 12910–12919 (2020).

Datta, A. et al. Cell death pathways in ischemic stroke and targeted pharmacotherapy. Transl. Stroke Res. 11, 1185–1202 (2020).

Veeresh, P. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria crosstalk: from junction to function across neurological disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1457, 41–60 (2019).

Sims, S. G., Cisney, R. N., Lipscomb, M. M. & Meares, G. P. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in astrocytes. Glia 70, 5–19 (2022).

Miyazaki-Anzai, S. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress effector CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) regulates chronic kidney disease-induced vascular calcification. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e000949 (2014).

Pépin, M. et al. Cognitive disorders in patients with chronic kidney disease: specificities of clinical assessment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 37(Suppl. 2), ii23–ii32 (2021).

Viggiano, D. et al. Mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction in CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 452–469 (2020).

Aboul-Enein, F. et al. Preferential loss of myelin-associated glycoprotein reflects hypoxia-like white matter damage in stroke and inflammatory brain diseases. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 62, 25–33 (2003).

Bouhrara, M. et al. Evidence of demyelination in mild cognitive impairment and dementia using a direct and specific magnetic resonance imaging measure of myelin content. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 998–1004 (2018).

Ji, Y. et al. The Sel1L-Hrd1 endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation complex manages a key checkpoint in B cell development. Cell Rep. 16, 2630–2640 (2016).

Wyld, M. & Webster, A. C. Chronic kidney disease is a risk factor for stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 30, 105730 (2021).

Ghoshal, S. & Freedman, B. I. Mechanisms stroke patients chronic kidney Dis. Am. J. Nephrol. 50, 229–239 (2019).

Toyoda, K. & Ninomiya, T. Stroke and cerebrovascular diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. Lancet Neurol. 13, 823–833 (2014).

Yahalom, G. et al. Chronic kidney disease and clinical outcome in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 40, 1296–1303 (2009).

Bikbov, B. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733 (2020).

Nayak-Rao, S. & Shenoy, M. P. Stroke in patients with chronic kidney disease…: how do we approach and manage it?. Indian J. Nephrol. 27, 167–171 (2017).

Vemuri, P. et al. Association of kidney function biomarkers with brain MRI findings: the BRINK study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 55, 1069–1082 (2017).

Zhou L. Homocysteine and Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurosci. 30, e14420 (2024).

Cohen, E., Margalit, I., Shochat, T., Goldberg, E. & Krause, I. The relationship between the concentration of plasma homocysteine and chronic kidney disease: a cross sectional study of a large cohort. J Nephrol. 32, 783–789 (2019).

Grieve, A., Butcher, S. P. & Griffiths, R. Synaptosomal plasma membrane transport of excitatory sulphur amino acid transmitter candidates: kinetic characterisation and analysis of carrier specificity. J. Neurosci. Res. 32, 60–68 (1992).

Finkelstein, J. D. The metabolism of homocysteine: pathways and regulation. Eur J Pediatr. 157, S40–S44 (1998).

Sachdev, P. S. Homocysteine and brain atrophy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 29, 1152–1161 (2005).

Lipton, S. A. et al. Neurotoxicity associated with dual actions of homocysteine at the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94, 5923-5928 (1997).

Mustapha, S. et al. Potential roles of endoplasmic reticulum stress and cellular proteins implicated in diabesity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 8830880 (2021).

Shruthi, K., Reddy, S. S., Chitra, P. S. & Reddy, G. B. Ubiquitin-proteasome system and ER stress in the brain of diabetic rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 5962–5973 (2019).

Kaneko, M. et al. A different pathway in the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced expression of human HRD1 and SEL1 genes. FEBS Lett. 581, 5355–5360 (2007).

Sicari, D., Delaunay-Moisan, A., Combettes, L., Chevet, E. & Igbaria, A. A guide to assessing endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and stress in mammalian systems. FEBS J. 287, 27–42 (2020).

Kaur, H. et al. Endovascular stem cell therapy post stroke rescues neurons from endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin receptor kinase B signaling. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12, 3745–3759 (2021).

Xiao, K. et al. Interaction between PSMD10 and GRP78 accelerates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated hepatic apoptosis induced by homocysteine. Gut Pathog. 13, 1–14 (2021).

Tay, S., Ampil, E., Chen, C. & Auchus, A. The relationship between homocysteine, cognition and stroke subtypes in acute stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 250, 58–61 (2006).

Wei, H. -j et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and neuronal apoptosis in rat hippocampus via upregulation of the BDNF-TrkB pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 35, 707–715 (2014).

Ramos-Cejudo, J. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor administration mediated oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelin formation in subcortical ischemic stroke. Stroke 46, 221–228 (2015).

Zhao, H., Gao, X.-Y., Wu, X.-J., Zhang, Y.-B. & Wang, X.-F. The Shh/Gli1 signaling pathway regulates regeneration via transcription factor Olig1 expression after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurol. Res. 44, 318–330 (2022).

Sarmah, D. et al. Cardiolipin-mediated alleviation of mitochondrial dysfunction is a neuroprotective effect of statin in animal model of ischemic stroke. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14, 709–724 (2023).

Datta, A. et al. Inosine attenuates post-stroke neuroinflammation by modulating inflammasome mediated microglial activation and polarization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1869, 166771 (2023).

Yavagal, D. R. et al. Efficacy and dose-dependent safety of intra-arterial delivery of mesenchymal stem cells in a rodent stroke model. PLoS ONE 9, e93735 (2014).

Vats, K. et al. Intra-arterial stem cell therapy diminishes inflammasome activation after ischemic stroke: a possible role of acid sensing ion channel 1a. J. Mol. Neurosci. 71, 419–426 (2021).

Datta, A. et al. Post-stroke impairment of the blood-brain barrier and perifocal vasogenic edema is alleviated by endovascular mesenchymal stem cell administration: modulation of the PKCδ/MMP9/AQP4-mediated pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 2758–2775 (2022).

Kaur, H. et al. Endovascular stem cell therapy promotes neuronal remodeling to enhance post stroke recovery by alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress modulated by BDNF signaling. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 19, 264–274 (2023).

He, M. et al. Olanzapine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in the hypothalamus were inhibited by an ER stress inhibitor 4-phenylbutyrate. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 104, 286–299 (2019).

Claramunt, D. et al. Chronic kidney disease induced by adenine: a suitable model of growth retardation in uremia. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 309, F57–F62 (2015).

Diwan, V., Brown, L. & Gobe, G. C. Adenine-induced chronic kidney disease in rats. Nephrology 23, 5–11 (2018).

Claramunt, D., Gil-Peña, H., Fuente, R., Hernández-Frías, O. & Santos, F. Animal models of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Is adenine intake an appropriate model?. Nefrología 35, 517–522 (2015).

Klinkhammer, B. M. et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of kidney injury in 2,8-dihydroxyadenine nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 31, 799–816 (2020).

Fawcett, J. K. & Scott, J. E. A rapid and precise method for the determination of urea. J. Clin. Pathol. 13, 156–159 (1960).

Taussky, H. H. A microcolorimetric determination of creatine in urine by the Jaffe reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 208, 853–861 (1954).

Fossati, P., Prencipe, L. & Berti, G. Use of 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxybenzenesulfonic acid/4-aminophenazone chromogenic system in direct enzymic assay of uric acid in serum and urine. Clin. Chem. 26, 227–231 (1980).

Singh, R. et al. Ultrastructural changes in cristae of lymphoblasts in acute lymphoblastic leukemia parallel alterations in biogenesis markers. Appl. Microsc. 51, 20 (2021).

Pravalika, K. et al. Trigonelline therapy confers neuroprotection by reduced glutathione mediated myeloperoxidase expression in animal model of ischemic stroke. Life Sci. 216, 49–58 (2019).

Kaur, H. et al. Endovascular stem cell therapy post stroke rescues neurons from endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin receptor kinase B signaling. ACS Chem. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00506 (2021).

O’Brien, J., Hayder, H. & Peng, C. Automated quantification and analysis of cell counting procedures using ImageJ plugins. J. Vis. Exp. 17, e54719 (2016).

Kaur, H. et al. Endovascular stem cell therapy post stroke rescues neurons from endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin receptor kinase B signaling. ACS Chem. Neurosci. (2021).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Sarmah, D. et al. Sirtuin-1-mediated NF-κB pathway modulation to mitigate inflammasome signaling and cellular apoptosis is one of the neuroprotective effects of intra-arterial mesenchymal stem cell therapy following ischemic stroke. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 18, 821–838 (2022).

Saraf, J. et al. Intra-arterial stem cell therapy modulates neuronal calcineurin and confers neuroprotection after ischemic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci. 129, 1039–1044 (2019).

Ismael, S., Zhao, L., Nasoohi, S. & Ishrat, T. Inhibition of the NLRP3-inflammasome as a potential approach for neuroprotection after stroke. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–9 (2018).

Ansorg, A., Bornkessel, K., Witte, O. W. & Urbach, A. Immunohistochemistry and multiple labeling with antibodies from the same host species to study adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Vis. Exp. 98, e52551 (2015).

Bieber, M. et al. Description of a novel phosphodiesterase (PDE)-3 inhibitor protecting mice from ischemic stroke independent from platelet function. Stroke 50, 478–486 (2019).

Lenth, R. V. Java applets for power and sample size. http://www.stat.uiowa.edu/~rlenth/Power (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER) Ahmedabad administration for providing the facility and support for conducting this study. The authors would also like to acknowledge Ms. Monika Seervi, Mr. Kunjan Parikh, Mr. Janapati Srinu, Dr. Shirish Bhatiya, and Dr. Satish Bhalodiya for their technical support in the study. Sophisticated Analytical Instrumentation Facility (SAIF), AIIMS, New Delhi, for sample processing and image acquisition and www.BioRender.com for image preparation. The study is funded by the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, for the senior research fellowship grant of A.D. (45/13/2020-PHA/BMS), ICMR project grant of P.B. (IIRP-2023-3905/F1) and www.BioRender.com for image preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: P.B. Data acquisition: A.D., P.P., D.G., P.J., M.K., J.S., A.K., N.M., G.K., A.B., B.G., P.D., V.P., D.S., H.K., N.R. and R.R. Analysis and interpretation of data: A.D., A.K., N.M., B.G., G.K., A.B. and P.B. Drafting and revision of the manuscript: A.D., B.G., A.B., R.R., A.B.H., P.S. and P.B. All authors have approved the final manuscript (A.B.—Anirban Barik and A.B.H.—Anupom Borah). H.K. is currently affiliated with the Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA, USA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Farhad Danesh and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joao Valente. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Datta, A., Patale, P., Ghosh, D. et al. Modulation of Sel1L can alleviate altered ER homeostasis towards white matter damage in CKD-stroke complex. Commun Biol 8, 677 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08100-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08100-0