Abstract

Microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins are critical regulators of cerebral cortex development, and their defects can lead to severe cortical malformations. EML1/Eml1 (Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 1) is a microtubule-binding protein whose mutations cause subcortical heterotopia in both humans and mice. While perturbations of Eml1 in neural progenitor cells have been associated with defects in cilia and progenitor cell detachment from the ventricular zone, the regulatory role of Eml1 at the protein level remains understudied. To reveal global changes in the absence of Eml1, we perform a comparative proteomic analysis of the cortices and neural progenitor cells of Eml1 conditional-knockout mice during cerebral cortex development. Our comprehensive analyses reveal that Eml1 depletion causes significant downregulation of multiple centrosomal and spindle proteins in neural progenitor cells. The absence of Eml1 significantly reduces microtubule polymerization and stability. Several microtubule-associated proteins, including Eml4 and Septins, lose their affinity with microtubules in the absence of Eml1. Our findings support the central role of Eml1 in the regulation of microtubules and provide a valuable resource for the investigation of the underlying mechanisms of heterotopia-based pathophysiological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cerebral cortex is a highly complex part of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions. During the developmental stage, it undergoes a finely controlled process known as corticogenesis, which involves the organization of a diverse set of neurons, originating from progenitor cells, across the layers of the cerebral cortex. This complex layering occurs through the communication and coordination of multiple cellular components, including cytoskeletal elements, microtubules (MTs), actin, and intermediate filament networks1,2,3,4. These dynamic interactions ensure the proper cortical layer formation and function for cognitive processes5,6.

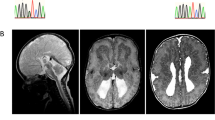

Among the multiple molecular players involved in cortical development, MTs and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) are essential as critical regulators of neurogenesis in cell proliferation, neuronal migration, and axonal guidance processes. Defects in these proteins can lead to cortical malformations, which are disorders resulting in developmental delay, intellectual and motor disabilities, and epileptic seizures5,6,7. Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 1 (EML1), a member of the EMAP family, has appeared as an important protein in both human and mouse cortical malformations8,9,10. Patients with EML1 mutations show a spectrum of abnormalities, including human ribbon-like subcortical heterotopia, involving abnormal neuronal positioning during cortical development, macrocephaly, hydrocephalus, polymicrogyria, and corpus callosum pathology8,9,11.

Notably, the Heterotopic Cortex (HeCo) mouse model with spontaneous Eml1 mutations shows a disruption of radial glial progenitor cells (RGs), including their detachment from the ventricular zone (VZ). This leads to a disruption of the proper distribution of RG in the developing cerebral cortex wall and, subsequently, leads to the formation of heterotopia8,12. RGs are the primary neural progenitors in the developing cortex, guiding neuronal migration and supporting neurogenesis through complex mechanisms requiring their distinct morphology and positioning within the developing cortex13,14,15. HeCo RGs exhibit abnormal proliferation outside the VZ, a phenotype associated with the formation of subcortical heterotopia (SH)8,12.

Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying Eml1-associated SH has revealed that Eml1 mutations cause disrupted primary cilia and centrosomes16,17. The Eml1-dependent cilia impairment phenotype highlights the critical role of MTs in the pathogenesis of SH. Despite its importance, the molecular details of the interaction between Eml1 and the MT cytoskeleton and its disruption in heterotopia remain to be determined.

In this study, we performed label-free and dimethyl labeling-based quantitative proteomic approaches and MT pelleting assays to investigate how the depletion of Eml1 changes protein interactions in cortices and neural progenitor cells during mouse cerebral cortex development. Our comprehensive proteomic maps of cortices and progenitor cells have identified protein signatures in an Eml1 conditional knockout (cKO) heterotopic mouse model, providing a valuable resource for studying the underlying mechanisms of heterotopia formation as well as normal brain development. Follow-up experiments further demonstrated the role of human EML1 in organizing the MT cytoskeleton and enhancing MT stability.

Results

Proteomic profiling of Eml1 cKO cortices revealed changes in the abundance of multiple proteins related to nervous system development

Eml1 perturbations cause cortical malformations during brain development. To systematically characterize the affected cellular pathways, we first examined the proteomic characteristics of embryonic cortices of the Eml1 cKO mouse model. These mice were generated by crossing homozygote Eml1-Flox mice with mice heterozygous for Emx-Cre, resulting in forebrain-specific Eml1 cKO animals. 100% of these Eml1 cKO mice exhibit SH17. We focused our analysis on E15.5 embryonic cortices, a critical time point where the effects of Eml1 depletion on cortical morphology, RG detachment, and primary cilia perturbation are known17. Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis was performed with three independent biological replicates (Fig. 1A).

A Overview of the mouse cortex proteomic workflow with control and Eml1 cKO mice analyzed in three biological replicates by LC-MS/MS. Cortex tissues were collected at E15.5 from 13 WT and 10 Eml1 cKO embryos from 3 different litters. Each replicate was obtained by pooling at least 3 embryos per genotype. Proteins were extracted, digested, and fractionated into 12 by offline high-pH reverse phase before mass spectrometry analysis. Created in BioRender. Ozlu, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ffzluxi. B A total of 6894 proteins were quantified, with 2.5% of the quantified proteins (170 proteins) found to be dysregulated in the cortex of Eml1 cKO mice. C Gene ontology (GO) analysis of dysregulated proteins in the cellular component (CC) using g:Profiler. D GO analysis of dysregulated proteins in the biological process (BP) using g:Profiler. E Volcano plots display proteins quantified in the cortex proteome, with the x-axis representing the log₂ (Fold Change) Eml1 cKO/control and the y-axis showing the −log10(p-value) from the t-test. Gray dots represent proteins with insignificant changes, blue dots specify statistically significant downregulated proteins, and red dots specify statistically significant upregulated proteins. Black vertical lines indicate the log₂ (Fold Change) threshold (±0.2), and the horizontal line marks the significance cutoff (p = 0.05). Dysregulated proteins in the BP GO term Cytoskeletal organization are highlighted. F Dysregulated proteins in the CC GO term Nervous system development are highlighted.

To improve the coverage of the cortex proteome, 200 µg of total protein from cortical lysates was fractionated by offline high-pH reversed phase, and these fractions were analyzed using Orbitrap mass spectrometry. As a result, a total of 8213 proteins were identified, of which 6894 unique proteins were quantified after filtering (Supplementary Data 1). Notably, the quantified proteins exhibited highly consistent log₂ distributions across all three replicates of both control and cKO samples, reinforcing the reproducibility of the data (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Additionally, we observed high quantitative accuracy among the three biological replicates, with Pearson correlation coefficients exceeding 0.95 (Supplementary Fig. 1B). The analysis of the most abundant proteins revealed similar profiles between control and cKO samples (Supplementary Fig. 1C). The top 100 most abundant proteins were enriched in key physiological processes relevant to diverse biological functions, including ‘translation,’ ‘regulation of mRNA metabolic processes,’ ‘regulation of cellular component organization,’ ‘glucose catabolic processes,’ and ‘pyridine nucleotide metabolic processes’ (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

Based on the statistical analysis, we found only 170 proteins (2.5% of the quantified proteome) as significantly differentially expressed between control and Eml1 cKO cortices (p < 0.05) comprising 118 upregulated proteins (log2 (Fold Change) > 0.2) and 52 downregulated proteins (log2 (Fold Change) < −0.2) (Fig. 1B). To investigate the cellular origins of protein dysregulation in Eml1 cKO cortices, we cross-referenced our dysregulated protein list with published cell type-specific markers from E15.5 cortical transcriptomic data (Supplementary Data 1)18. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis based on cellular components revealed a strong enrichment for the dysregulated proteins found in Eml1 cKO within synaptic, cell projections, and neuronal compartment proteins (Fig. 1C). Based on biological processes, cytoskeleton organization and nervous system development were among the top enriched terms (Fig. 1D). Both Tau protein, encoded by the Mapt gene that stabilizes MTs in neurons19, and its interaction partner Bin120 are upregulated in Eml1 cKO cortices, as well as other proteins (Fig. 1E). In the absence of Eml1, several actin cytoskeleton-related proteins, including Cdc42ep2, Coro1a, Abr, and Ccdc53, are also upregulated (Fig. 1E). Multiple dysregulated proteins associated with nervous system development, including Nrxn3, Ptprd, Arhgap44 and Efnb3, are upregulated, whereas Rttn is downregulated in Eml1 cKO heterotopic cortices (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, our analysis identified dysregulation in proteins previously linked to cortical malformations such as Cenpe, Pnkp and Dnaaf521,22,23.

Our analysis of cortices showed a high coverage of quantified proteins but a relatively low proportion of dysregulated ones. The cortex region of the E15.5 embryonic brain contains a wide variety of cell types, including progenitor cells, corticothalamic projection neurons, subcerebral projection neurons, callosal projection neurons, interneurons, and Cajal-Retzius cells24. Therefore, it remains possible that many dysregulated proteins may be diluted at the tissue level due to the complexity of the cortex.

Primary cultures of progenitor cells lacking Eml1 exhibit dysregulations of microtubule organization and translation-related proteins

Since Eml1-linked heterotopia formation is closely linked to phenotypes in RG8,12,16, we aimed to analyze the proteome of primary cultures of neural progenitor cells derived from Eml1 cKO mice. To this end, we prepared highly enriched populations of Pax6+ RG-like cell cultures from control and Eml1 cKO mice at E14.5, minimizing cell complexity from the mixed composition of cortex tissue and enabling a targeted analysis of the RG-like progenitor cells.

Unlike cortex tissue, obtaining sufficient protein concentrations for comprehensive proteome analysis of the cells was a significant challenge. To overcome this, we employed a dimethyl isotopic labeling-based quantitative proteomics approach, labeling 20 µg of protein from control and Eml1 cKO progenitor cell lysates with light and heavy isotopes (Fig. 2A). Following labeling, the light- and heavy-labeled control and cKO samples were pooled and fractionated by offline high-pH reversed phase. This approach yielded nearly 4000 quantified proteins, 266 of which showed significant dysregulation (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Data 2). The log2 H/L ratios of the biological replicates exhibited consistent intensity distributions (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Additionally, we observed positive correlations between the two biological replicates for both quantified and dysregulated proteins, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.51 and 0.99, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

A Overview of proteomic workflow for mouse neural progenitor cells derived from control and Eml1 cKO embryos. Pax6+ neural progenitor cells were isolated at E14.5 and propagated in culture. Cells were obtained from 6 WT and 6 Eml1 cKO embryos collected from 3 different litters. Each replicate was generated by pooling 3 embryos per genotype. Proteins were extracted, labeled using dimethyl isotopic labeling and fractionated by offline high-pH reverse phase prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Created in BioRender. Ozlu, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/5x8vohl. B Identification of 266 significantly dysregulated proteins out of nearly 4000 quantified proteins in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells. C Functional network analysis of the 266 dysregulated proteins generated with ClueGO in Cytoscape, highlighting enriched functional categories. D PANTHER GO-Slim Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) for the upregulated (135 proteins) (brown) and downregulated (131 proteins) (blue) proteins in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells, respectively.

Furthermore, clustering analysis of all detected dysregulated proteins revealed that Eml1 depletion disrupted multiple biological process networks, including cytoplasmic MT organization, regulation of response to endoplasmic reticulum stress, translation, and protein localization to the vacuole (Fig. 2C). Among the dysregulated proteins, 131 were downregulated, while 135 were upregulated. GO analysis showed that downregulated proteins were enriched in processes, including MT cytoskeleton organization, MT structure, and structural constituents of the cytoskeleton, aligning with the known MT-binding role of Eml1 and suggesting its involvement in MT organization in neural progenitor cells (Fig. 2D)25. In contrast, upregulated proteins were enriched in processes associated with the regulation of translation, ribosome structure, and RNA binding components (Fig. 2D).

Next, we focused on dysregulated proteins involved in MT cytoskeleton organization and protein metabolic process due to their pronounced dysregulation upon Eml1 depletion (Fig. 3). Our analysis revealed distinct clusters of proteins involved in spindle organization, organelle organization, and organelle transport along MTs. We observed dysregulation of proteins associated with the MT organizing center (MTOC), a critical structure involved in MT nucleation and organization, in which Tubg1 is a major component26. We observed significant downregulation of Tubg1, which encodes γ-tubulin, in Eml1 cKO progenitor cells. Our recent study confirmed the reduction of Tubg1 in progenitor cells at E12.5 and E15.5 in Eml1 cKO cortices by immunocytochemistry, correlating with decreased MT growth17.

A Volcano plots display proteins quantified in the neuronal progenitor cell proteome, with the x-axis showing log₂ (Fold Change) Eml1 cKO/control and the y-axis representing −log10(p-value) from the t-test. Gray dots indicate unchanged proteins, while significantly downregulated and upregulated proteins are shown in blue and red, respectively. Black vertical lines indicate the log₂ (Fold Change) threshold (±0.2), and the horizontal line marks the significance cutoff (p = 0.05). Proteins belonging to “Microtubule cytoskeleton organization” and “Translation” are outlined in black. B Microtubule cytoskeleton organization proteins and protein translation proteins were selected from the dysregulated list of 266 proteins using UniProt biological processes. Microtubule cytoskeleton organization was clustered into three groups: spindle organization, organelle organization, and organelle transport along microtubules. The proteins in protein metabolic processes were clustered into positive regulation of translation and macromolecule biosynthetic processes subgroups. Red circles represent upregulated proteins, and blue circles represent downregulated proteins in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells. Proteins localized to the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) are highlighted in gray, and ribosomal proteins are highlighted in orange.

Additionally, spindle organization-related proteins, including Numa1, Kif3b, and Tacc3, were downregulated in Eml1 cKO progenitor cells (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, our analysis revealed dysregulation in organelle organization and organelle transport proteins associated with mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomes, and the Golgi apparatus (e.g., Ckap4, Map1b, Vps41, Kif1b, and Tmem55B) (Fig. 3A, B).

The dysregulated proteins involved in translation cluster in macromolecular biosynthetic processes and positive regulation of translation (Fig. 3A, B). Notably, ribosomal proteins such as Rps20, Rps10, Rpl36, and Rps25 were strongly upregulated in Eml1 cKO progenitor cells. A previous study showed that EMAP family proteins are involved in ribosome attachment to MTs27, and our findings suggest a potential role for Eml1 in ribosome association. Interestingly, we also observed upregulation of Ttc5, a tubulin-specific ribosome-associating factor that triggers cotranslational degradation of tubulin mRNAs in response to excess soluble tubulin28. It has been reported that Eml4 interacts with Ttc5 in HEK cells29. Excess cytoplasmic tubulin resulting from dysregulated MT dynamics and turnover mechanisms may lead to Ttc5 upregulation in Eml1 cKO cells.

In summary, proteomic analysis of cultured neural progenitor cells suggests that Eml1 depletion induces molecular alterations in MT cytoskeleton organization and ribosome-related processes.

Depletion of Eml1 disrupts the network of microtubule-associated proteins

To investigate the impact of Eml1 depletion on MT organization, we performed an MT pelleting assay in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells. Endogenous tubulin was polymerized with taxol, MTs and MAPs were sedimented, and the MT-bound proteins were analyzed via gel fractionation followed by Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Fig. 4A). Despite starting with equivalent cell numbers in control and cKO samples, we observed striking differences in the amount of pelleted MTs between the groups. Both biological replicates of cKO samples exhibited decreased levels of MTs and MAPs on SDS-PAGE gels with Coomassie staining (unpaired two-tailed t-test, p = 0.044) (Fig. 4B).

A Overview of microtubule pelleting proteomic workflow for mouse neural progenitor cells derived from control and Eml1 cKO embryos. Pax6⁺ neural progenitor cells were isolated at E14.5, lysed, and treated with taxol to stabilize microtubules prior to pelleting. Pellet fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Cells were obtained from 4 WT and 4 Eml1 cKO embryos collected from 2 different litters, and each replicate was generated by pooling 2 embryos per genotype. Created in BioRender. Ozlu, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/5nokslf. B Pelleted microtubule intensities of tubulin bands (50 kDa) from Coomassie-stained gels (Fig. 4A) were quantified using Fiji (ImageJ). Data represent mean ± SD from two biological replicates. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; p = 0.046. C Among the 2805 quantified proteins, 347 (12.4%) were dysregulated in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells. D Volcano plot displays quantified proteins in microtubule pelleting assay, with the x-axis showing log₂ (Fold Change) Eml1 cKO/control and the y-axis representing −log₁₀(p-value) from the t-test. Within quantified proteins, unchanged proteins (gray), significantly downregulated proteins (blue), and significantly upregulated proteins (red) are labeled accordingly. Black vertical lines indicate the log₂ (Fold Change) threshold (±0.2), and the horizontal line marks the significance cutoff (p = 0.05). Tubulins, EMAPs, and Septins are labeled in the graph. E Western blot analysis of microtubule pelleting assay performed on mouse neural progenitor cells derived from control and Eml1 cKO embryos. Pax6⁺ neural progenitor cells were isolated at E14.5, lysed, and treated with either DMSO or taxol. Supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were collected for analysis. Cells were obtained from 10 WT and 11 Eml1 cKO embryos collected from 3 different litters. Each replicate was generated by pooling at least 2 embryos per genotype. F Quantification of the % tubulin in the pellet fraction represented in (E). Error bars represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA; p < 0.0001 (****). G Sept2 levels in the pellet fraction, normalized to tubulin. Error bars represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA; p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.0001 (****). H STRING-db analysis of the dysregulated proteins highlighting the connection between Septins and EMAP family proteins. Lines between the proteins correspond to known interactions. Blue circles represent downregulated proteins in the microtubule pelleting of Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells.

To identify Eml1-dependent alterations in the MT cytoskeleton, each protein was normalized to tubulin intensities as a reference protein. Our analysis revealed consistent distributions across two replicates of control and cKO samples, with Pearson correlation coefficients exceeding 0.84 (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). Notably, out of 2805 quantified proteins, 347 were dysregulated between control and Eml1 cKO samples (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Data 3). To ensure an unbiased analysis, we used the average tubulin intensity as a reference and normalized cKO protein intensities to the control. Despite this tubulin normalization favoring cKO progenitors, 320 proteins were significantly downregulated (log2 (Fold Change) < −0.5), while only 27 proteins were upregulated (log2 (Fold Change) > 0.5). These results indicate severe disruptions in the MT-associated network in Eml1-depleted cells.

Importantly, Eml4’s MT affinity is reduced in the absence of Eml1 (Fig. 4D). Although Eml1 depletion in progenitor cells does not significantly alter the total abundance of Eml4 (−log (p-value) = 0.67 and log2 (Fold Change) = −0.39) (Supplementary Data 2), it leads to a significant dissociation of Eml4 from MTs (−log (p-value) = 2.12 and log2 (Fold Change) = −4.64) (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Data 3). Similarly, Eml1 depletion significantly affects the MT association of multiple Septins (Fig. 4D).

Septins are GTP-binding proteins that form distinct filamentous networks along MTs, actin, and intermediate filaments, associating with MTs. Septins can colocalize with perinuclear, Golgi-nucleated, subcortical, and axonemal MTs to regulate their stability and MT organization through interaction with MT-binding proteins30,31,32,33,34,35,36. In mice, there are a total of thirteen Septin genes37. Our analysis identified nine Septins, seven of which (Sept2, Sept3, Sept5, Sept6, Sept8, Sept9, and Sept11) were significantly downregulated in Eml1 cKO progenitor cells. The remaining two (Sept7 and Sept10) were also downregulated but did not meet the significance threshold (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Data 3).

To confirm the impact of Eml1 depletion on MT polymerization, we performed another MT pelleting assay using DMSO- and taxol-treated control and cKO neural progenitor cells and analyzed MT and free tubulin levels (Fig. 4E). Comparison of DMSO- and taxol-treated cells revealed that cKO cells had significantly less MTs and higher levels of free tubulin after taxol treatment (Fig. 4E, F, Supplementary Fig. 3C). This supports our findings and suggests that Eml1 plays a role in stabilizing MTs in neural progenitor cells. Western blot analysis also confirmed reduced Sept2 associated with taxol-stabilized MTs and an increased soluble fraction of Sept2 in Eml1 cKO neural progenitor cells (Fig. 4E, G, Supplementary Fig. 3D).

While no direct interaction between Septins and EMAP family proteins is known, our MT proteome analysis reveals that Eml4 and Sept2 share two common interactors from our list: Ckap5 (cytoskeleton-associated protein 5) and Dync1h1 (a component of the dynein motor complex), both of which also exhibit reduced MT affinity in Eml1 cKO cells (Fig. 4D). Specifically, Ckap5 plays crucial roles in MT nucleation by regulating the γ-tubulin ring complex at MTOCs38 and Dync1h1, a motor protein, is essential for cargo transport39. Eml1 depletion leads to a reduction in these interconnected protein hubs on MTs (Fig. 4H), potentially contributing to Eml1-mediated MT organization. All key dysregulated proteins across three datasets (cortex proteome, neural progenitor proteome and microtubule-associated proteome) are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

EML1 interacts with EML4 and contributes to its association with microtubules

To further investigate the role of EML1 in MT cytoskeleton organization, we generated an EML1 KO HeLa cell line using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. qPCR analysis confirmed reduced EML1 expression in the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease and sgRNA1-3-expressing cell population compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 4A), while single colonies selected from sgRNA2-treated cells showed no detectable EML1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Antibodies against EML1 did not work to confirm this deletion at the protein level. Therefore, we transduced EML1 KO HeLa cells with an Eml1-GFP vector, and western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody confirmed the loss of Eml1-GFP in KO but not in control cells (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Consistent with our MT pelleting assay in mouse neural progenitor cells (Fig. 4), EML1 KO HeLa cells exhibited fewer pelleted MTs (Fig. 5A, B) and significantly lower EML4 and SEPT2 association with MTs compared to controls, even after normalization to MT levels (Fig. 5A, C, D). Despite these differences in MT association, total protein levels of EML4 and SEPT2 remained comparable between EML1 KO and control HeLa cells (Fig. 5A). Similarly, immunostaining revealed that total EML4 fluorescence intensities after paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation were unchanged between conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E). However, after methanol fixation, which removes many soluble proteins40, EML4 levels were diminished in EML1 KO cells (Fig. 5E, Supplementary Fig. 4F), and tubulin levels were also reduced, consistent with the previous study17 (Supplementary Fig. 4G). Next, we quantified the colocalization of EML4 and tubulin in methanol-fixed cells. To eliminate intensity differences, we used Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The results indicate reduced colocalization in EML1 KO cells compared to controls (Fig. 5F).

A Western blot analysis of microtubule pelleting assay with the indicated antibodies of whole-cell lysate (WCL) and pellet (P) fractions from control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO HeLa cells treated with taxol. B Quantification of the % tubulin in the pellet fraction represented in (A). Error bars represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; p = 0.0003. C Relative intensity of EML4 in the pellet fractions of control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO cells, normalized to tubulin levels. Error bars represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; p = 0.0007. D Relative intensity of SEPT2 in the pellet fractions of control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO cells, normalized to tubulin levels. Error bars represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test, p = 0.0002. E Immunofluorescence images of control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO HeLa cells stained for EML4 (green), α-tubulin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Images are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar: 10 µm. F Quantification of EML4/tubulin colocalization in control and EML1 KO cells using Pearson correlation coefficient. Data represent 30 cells per condition for each of the two independent experiments. Error bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; p = 0.0387. G Western blot analysis of GFP pull-down assay with the indicated antibodies of whole-cell lysates (WCL), unbound (UB), and elution (ELU) fractions from HeLa cells expressing GFP-only or GFP-tagged Eml1. Eml1-GFP was detected using a GFP antibody. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown.

Our previous study identified Eml4 as an interactor of Eml1 in Neuro2A cells17. Next, we performed a GFP pull-down assay using HeLa cells expressing Eml1-GFP to investigate whether Eml1 and EML4 form a complex. Our results showed that EML4 was associated with Eml1-GFP, and not in cells expressing only GFP (Fig. 5G). These findings suggest that EML1 and EML4 interact, which may facilitate EML4’s association with MTs.

EML1 promotes microtubule stability

To directly assess the role of EML1 in MT stability, we performed immunofluorescence staining for acetylated tubulin to visualize stable MT structures in control and EML1 KO HeLa cells. EML1 depletion resulted in a significant reduction in acetylated tubulin levels compared to control cells (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Fig. 4H). This reduction remained significant even after normalizing acetylated tubulin levels to total MT intensities (Fig. 6B), indicating that EML1 depletion impacts MT stability. Additionally, EML1 KO cells exhibited increased sensitivity to nocodazole, an agent that inhibits the polymerization of MTs. Both mock (DMSO) and low-dose nocodazole-treated control cells had similar levels of MTs. Under the same conditions, nocodazole-treated EML1 KO cells were unable to maintain their MT network, since MT intensities were significantly reduced compared to mock-treated EML1 KO cells (Fig. 6C, D). These results suggest that EML1 is essential in maintaining polymerized and stable MTs.

A Immunofluorescence images of control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO HeLa cells stained for acetylated α-tubulin (green), α-tubulin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 10 µm. B Quantification of relative acetylated α-tubulin levels in control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO cells, normalized to total tubulin. Data represent 30 cells per condition for each of the three independent experiments. Error bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; p = 0.0494. C Immunofluorescence images of control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO HeLa cells treated with DMSO or 80 nM nocodazole for 2 h, stained for α-tubulin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Images are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar: 10 µm. D Quantification of relative α-tubulin intensity in control and CRISPR-Cas9 EML1 KO cells under DMSO- and nocodazole-treated conditions. Data represent two independent replicates, with 20 cells per condition. Error bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA; p = 0.0455 (*) and ns = not significant.

Discussion

In this study, we performed quantitative proteomic analyses from the Eml1 cKO mouse brain at E14.5-15.5 and identified Eml1 depletion-dependent dysregulation in cortices and primary cultures of neural progenitor cells. In cortices, Eml1 depletion causes dysregulations in proteomes that are associated with synapse, cell projection, cytoskeleton organization and nervous system development. Several proteins related to nervous system development, such as Ptprd, Efnb3, Pax6 and Arhgap44, are upregulated. Ptprd, a receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase, is involved in cortical neurogenesis in rodents by regulating the numbers of intermediate progenitor cells and neurons41. Similarly, the proteins Efnb3 and Pax6, which are involved in neuronal migration and cortical layering42,43, were found to be upregulated. These upregulations may occur as a compensatory response to abnormal migration observed in the brains of Eml1 cKO mice, and/or they could result from altered signaling pathways in Eml1 cKO mice44, leading to increased expression as a downstream effect.

Rttn is a centrosomal protein essential for proper mitotic spindle assembly, ciliogenesis, and neuronal migration45,46. Its downregulation in the Eml1 cKO cortex, as revealed by our proteomics data, suggests a functional interplay between Eml1 and Rttn. Eml1 mutations have been shown to impair primary cilia formation, affecting apical radial glia (aRG) function during cortical development16. Given Rttn’s role in ciliogenesis and its requirement for maintaining cortical architecture47, its reduced expression may further contribute to the cortical malformations observed in Eml1 cKO. Remarkably, tau, a key regulator of microtubule stability in neurons, is also upregulated. It is highly abundant in the embryonic mouse brain, and its increased expression may serve to counteract the microtubule defects caused by EML1 loss48.

The proteomic analysis of neural progenitor cells reveals that the depletion of Eml1 leads to the downregulation of several proteins involved in spindle, centrosome organization and cytoplasmic microtubule organization. It has been reported that ectopic expression of Eml1 decorates the mitotic spindle8 while its disruption leads to longer spindles12. Spindle organization defects have also been observed with Eml4 and Eml6 depletion, highlighting the significance of EMAP family proteins in maintaining spindle integrity49,50. γ-tubulin, a key structural element in MT nucleation and organization26, was found to be significantly downregulated in Eml1 cKO progenitor cells17. Consistent with this observation, our recent study showed that the absence of Eml1 compromises the presence of γ-tubulin at the centrosomes and MT regrowth from centrosomes17. Other essential centrosomal components, including Numa, Tacc2, and Tacc3, are dysregulated in the proteome of Eml1 cKO progenitor cells, underlying a global role of Eml1 in centrosome organization. Additionally, Kif1b and Kif3b, kinesins essential for organelle and vesicle transport, synaptic function, and neuronal viability51,52,53, are downregulated in the absence of Eml1. The molecular details of functional interactions between Eml1 and these kinesins remain to be investigated.

Eml1 cKO progenitor cells undergo early delamination, e.g., detachment from the VZ to more superficial layers, as well as showing primary cilium defects16. The primary cilium defects can influence several signaling pathways, including Hippo, Wnt, and mTOR pathways54. Progenitor cells in the VZ have direct connections to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), via primary cilia, which serves as both a proliferative niche and a nutrient source for neural progenitor cells55. Our Eml1 cKO neuronal progenitor proteome revealed the upregulation of several ribosomal proteins and Lamtor4. Lamtor4 is a component of the Ragulator complex, which senses amino acid availability in cells and recruits and activates mTORC156. The upregulation of ribosomal proteins is associated with various human cancers57, and the upregulation of Lamtor4 is also linked to cancer metabolism controlling mTOR signaling58. These findings may suggest a potential survival mechanism in Eml1 cKO cells through these upregulations, similar to cancer cells, because depletion of Eml1 disrupts cellular interactions with the CSF due to early delamination. Therefore, these cells have limited access to crucial proliferative VZ niches and nutrient sources. They are instead exposed to a more superficial extracellular environment. Further research is required to fully understand the upregulation of dysregulated proteins in relation to the RG phenotype.

Eml1 depletion in progenitor cells also led to the upregulation of tubulin-folding cofactor B (Tbcb)59 and tetratricopeptide protein 5 (Ttc5)28. Ttc5 is a ribosome-associating factor that triggers the degradation of tubulin mRNA in response to excess soluble tubulin, dynamically tuning tubulin abundance28. The upregulation of Tbcb and Ttc5 in Eml1-depleted cells may indicate a compensatory response to maintain the balance between free tubulin levels and MT growth rate. In line with this, we observed that the absence of Eml1 leads to significantly less polymerization of MTs in both mice and humans. The reason for sedimentation of less MTs could be partly due to defective recruitment of γ-tubulin to the centrosomes thus defective MT nucleation in the absence of Eml117. Indeed, when MTs are imaged in methanol-fixed HeLa cells, significantly less MTs are quantified as compared to control (Fig. 6C, D). Similar results were also observed in embryonic brain slices at E12.5 in control and Eml1 cKO17. In addition, acetylated MTs that show stable MTs are significantly less in EML1 KO HeLa cells, even if they were normalized to total MTs. Furthermore, in the absence of EML1, HeLa cells are more susceptible to the MT inhibitor of polymerization, nocodazole. While these experiments demonstrate a clear effect of EML1 on microtubule stability in HeLa cells, the cellular context differs considerably from that of neuronal progenitors in terms of microtubule organization, the expression pattern of MAPs, and the regulatory mechanisms involved19. Therefore, further studies in neuronal progenitors are crucial to determine the exact role of EML1 in neuronal cells and brain development. Overall, EML1 promotes the nucleation, polymerization, and stabilization of microtubules.

Several MT-associated proteins, including Eml4, lose their affinity for MTs. Thus, we suggest that this may be a reason for less stable MTs in the absence of EML1. It has been shown that EML4 is strongly associated with long interphase MTs, but as cells progress into mitosis, phosphorylation triggers its dissociation from highly dynamic spindle MTs, thereby removing its MT-stabilizing activity to allow proper chromosome congression60. It is plausible that Eml1 helps promote the binding of Eml4 to neuronal MTs, increasing their stability. Notably, MT stabilization with Epothilone D rescues multiple Eml1-associated phenotypes, including centrosomal defects, RG detachment, and reduces the volume of heterotopia in mouse embryos17. Therefore, Eml1 may cooperate with Eml4 in its central role in MT stabilization during cortical development. In support of this idea, EML4’s oncogenic fusion variants have been shown to promote MT stability and enhance cell migration via NEK kinase signaling pathways25,61. Given that MT dynamics are essential for neuronal polarity, migration, and axonogenesis1,2, EML1-EML4 interaction may be critical for proper neuronal organization. Our findings raise the possibility that EML1-EML4 interactions contribute to MT-based regulations underlying cortical tissue architecture. Future studies could investigate the impact of EML1-EML4 interaction in these developmental processes.

A recent study has shown that Eml1 facilitates tubulin acetylation in neuroblast cell lines and cortical neurons obtained from E18 rats62. The authors propose that Eml1 and α-tubulin acetyltransferase, αTAT1 interaction promotes microtubule stability, thus axonal growth in neurons62. EML1 may function as a hub protein, capable of interacting with multiple microtubule-associated proteins. It contains key domains that support its role as a scaffold for protein-protein interactions. The TAPE (tandem atypical propeller in EMLs) domain, consisting of two beta-propellers, and the trimerization domain (TD) at the N-terminus enable the formation of trimers contribute to its microtubule association and ability to interact with multiple partners25,63. Thus, EML1 loss could mainly reflect its scaffolding role in microtubule network organization rather than direct interaction with specific proteins.

Our MT pelleting assay showed that the absence of Eml1 reduces the binding affinity of several members of the Septin family to MTs in both neural progenitor cells and cultured human cancer cells. Although there is no known direct link between Eml1 and Septin protein families, they may cooperate in the regulation of MTs. Both neuronal Septins and Eml1 promote the growth and stability of MTs during the development of the mammalian brain64. Eml1 may enhance the affinity between Septins and MTs, either directly through protein interactions or indirectly by modulating the dynamics of MTs, to stabilize their interaction. It has been shown that Septins preferentially associate with stable, acetylated MTs65; thus, the observed reduction in Septin association may be linked to the decrease in acetylated MT levels seen in Eml1 cKO cells. Therefore, disrupted MT stability with Eml1 depletion may indirectly affect Septin recruitment. Further experimental studies are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between Eml1, Septins, and MTs, and the consequences of disrupting this interaction.

Overall, our study provides the first comprehensive overview of proteomic analyses of the cerebral cortex with Eml1 depletion, associated with heterotopia formation. It reveals a large-scale change in binding partners for MTs and provides evidence that Eml1 is one of the main regulators of the MT cytoskeleton in cortices to stabilize MTs. A detailed analysis of any of the dysregulations in Eml1-depleted cells will yield more insights into the underlying mechanisms involving the EMAP family, brain development, and heterotopia formation.

Methods

Ethics statement

All experimental procedures were approved by the local ethical committee (Charles Darwin, Paris, France) and conducted following national and international guidelines (CE 2010/63/EU, French national APAFIS n° 23424, 46509). Eml1fl/fl and Eml1fl/fl*Emx1-Cre C57BL/6J mice were housed under controlled lighting conditions (12L:12D, lights on at 07:00) and provided with food and water. Males and females were used in all analyses. Prior to dissection, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Cortical tissue collection

Upon sacrificing the pregnant females, E15.5 embryos were collected, and the cortex region was dissected in ice-cold 1x HBSS. Following cortex collection, tissues were washed with PBS to minimize the possibility of blood contamination, and samples were stored at −80 °C until protein extraction.

Cell culture

Highly enriched populations of Pax6+ neural progenitor cells were cultured following an adapted protocol66. Briefly, cortices from E14.5 embryos were dissected in an ice-cold basal medium (DMEM/F12 Hams, 1% Pen-Strep, 2.9 mg/ml glucose, and 1.2 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate). Followingly, the ice-cold basal medium was replaced with a pre-warmed complete medium (basal medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml of FGF (F0291, Sigma Aldrich), 20 ng/ml of EGF (E9644, Sigma Aldrich), and 1x B27 without vitamin A (12589-010, Gibco)). Cells were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells in 6-well culture plates, which were pre-coated with 2 µg/cm2 poly-L-lysine (P6407, Sigma Aldrich) followed by 1 µg/cm2 fibronectin (F1141, Sigma Aldrich). The cells were split once at 7 days before cell collection. Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh complete medium every 2 days for 1 week.

HeLa Kyoto and HEK293 cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere. Cells were passaged at ~80% confluency using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA.

Plasmid construction

CRISPR/Cas9-based EML1 knockout plasmids were constructed by cloning sgRNA oligonucleotides into the BbsI restriction sites of the lentiCRISPRv2 vector (#52961; Addgene), as described67. The following sgRNA sequences were used as top/bottom pairs: sgRNA1, 5′-CACCGTCGGCGGCTGAACATTACTG-3′/5′-AAACCAGTAATGTTCAGCCGCCGAC-3′; sgRNA2, 5′-CACCGAAGTAGACGGTCTCTCCCGT-3′/5′-AAACACGGGAGAGACCGTCTACTTC-3′; sgRNA3, 5′-CACCGCGTCTACTTCATCGCATCCG-3′/5′-AAACCGGATGCGATGAAGTAGACGC-3′. A non-targeting sgRNA (5′-CACCGACGGAGGCTAAGCGTCGCAA-3′/5′-AAACTTGCGACGCTTAGCCTCCGTC-3′)68 was used to generate a matching control cell line.

For Eml1-GFP expression, Eml1 cDNA was inserted into the BamHI restriction site of the pLenti-CMV-puro vector (17448; Addgene) using Gibson assembly, as described69. The following primers were used for Gibson cloning: forward, 5′-GAAGACACCGACTCTAGAGCACCATGGAGGACGGCTTCTC-3′; and reverse, 5′-CTCACCAGGTGGCGACCGGTGTAATGACTCGCCACTGCATGAT-3′. All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Transfection and generation of stable cell lines

HeLa Kyoto cells were transfected with lentiCRISPRv2 constructs containing EML1-targeting or non-targeting sgRNAs using Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000001, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, cells were selected with puromycin (1.0 µg/ml), and single-cell clones were isolated by limiting dilution. Clones were expanded and screened for EML1 knockout.

For stable Eml1-GFP expression, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with psPAX2, pMD2.G, and pLenti-CMV vectors encoding Eml1-GFP or GFP-only, as previously described70. Viral supernatants were used to transduce HeLa Kyoto cells, followed by puromycin selection (1.0 µg/ml) and validation by fluorescence microscopy and Western blotting.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA Kit (740955.50, Macherey-Nagel) and reverse-transcribed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814, Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was performed using Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (M3003S, New England Biolabs) on LightCycler 480 Instrument II (Roche) with primers specific for EML1 and PPBI. Gene expression levels were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method71, and normalized to PPBI as an endogenous control. The following primers were used: The following primers were used: EML1 (forward: 5′-GGGTCTATGGGTACAGGGGT-3′, reverse: 5′-ACTGCTAGGCACTTCACGTC-3′)44; PPIB (forward: 5′-GGAGATGGCACAGGAGGAA-3′, reverse: 5′-GCCCGTAGTGCTTCAGTTT-3′)72.

In-solution digestion and fractionation of mouse cortex

The cortices of control and Eml1 cKO mice were subjected to protein isolation using a lysis buffer of 8 mol/L urea, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (15677308, Thermo Fisher Scientific), phosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor mixture (04906837001, Roche), and 1% n-octylglucoside in 50 mmol/L pH 8.0 ammonium bicarbonate. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA assay (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Three biological replicates of 200 μg of total proteins from controls and cKOs were subjected to the reduction of disulfide bonds with 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol for 1 h at 56 °C, followed by cysteine alkylation with 20 mmol/L iodoacetamide for 45 min in the dark at room temperature. The urea concentration was reduced to 1 mol/L, and trypsin was added at a 1:40 enzyme-to-protein ratio. Protein digestion was performed at 37 °C overnight and quenched with 10% formic acid (FA).

Resulting peptides were initially desalted using Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (WAT023590, Waters) and then fractionated via offline high-pH reversed-phase fractionation for comprehensive proteome analysis. Briefly, the peptides were reconstituted in 15 mM ammonium hydroxide (2% ACN, pH 10) and loaded onto Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (WAT023590, Waters) that had been pre-activated with methanol and 15 mM ammonium hydroxide buffer (pH 10, containing 60% ACN). The flow-through was collected as the first fraction. Subsequent elution was conducted in a stepwise manner with increasing acetonitrile concentrations (6–10–12–14–16–18–20–22–24–26–28–30–60–90% ACN). For the final fraction, eluates containing 28–30–60–90% ACN were combined. Following fractionation, all 12 fractions from each sample were dried using a SpeedVac and stored at −20 °C.

In-solution digestion, isotopic labeling, and fractionation of neural progenitor cells

Neural progenitor cells were subjected to in-solution tryptic digestion following the same protocol used for cortex tissues. After lysis and desalting, isotopic labeling of control and Eml1 cKO samples was performed by labeling primary amines with dimethyl isotopes, according to an adapted protocol73,74. For light dimethyl labeling, a mixture of 4% formaldehyde solution (CH2O) and 0.6 mol/L cyanoborohydride solution (NaBH3CN) was prepared in 50 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), while for dimethyl heavy labeling, a mixture of 4% 13CD2-labeled formaldehyde solution and 0.6 mol/L cyanoborodeuteride solution (NaBD3CN) was used.

Twenty micrograms of peptides from two biological replicates of controls and cKOs were loaded onto C18 stage-tips and flushed with the prepared light and heavy dimethyl labeling solutions, respectively. The labeled peptides of controls and cKOs were then fractionated again via offline high-pH reversed-phase fractionation for comprehensive proteome analysis using the same protocol as for cortices, but on C18 stage-tips. Following fractionation, 12 fractions of two dimethyl-labeled neuronal progenitor cell samples were dried using a SpeedVac and stored at −20 °C.

Microtubule pelleting assay

Neural progenitor cells of control and Eml1 cKO were lysed in a buffer containing 100 mmol/L PIPES dipotassium salt (sc-258019, Santa Cruz), 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM DTT, a protease inhibitor (15677308, Thermo Fisher Scientific), phosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor mixture (04906837001, Roche), 20 µmol/L cytochalasin D (11330, Cayman Chemical), and 20 µmol/L latrunculin B (428020, Sigma Aldrich). Lysates were precleared at 2500×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, samples were further centrifuged at 100,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were incubated with 25 µmol/L taxol (paclitaxel, HY-B0015, MedChemExpress) and 0.5 mmol/L GTP for 20 min at room temperature to stabilize the microtubules. The stabilized microtubules were pelleted at 100,000×g for 30 min at 25 °C with a cushion of 40% glycerol in BRB80 buffer containing 1 mmol/L DTT, 25 µmol/L taxol, 1 mmol/L GTP, and protease inhibitor.

The pellet was resuspended in CM buffer (100 mmol/L K-PIPES pH 7, 2 mmol/L EGTA, 1 mmol/L MgCl2) containing 20 µmol/L cytochalasin D and 20 µmol/L latrunculin B, followed by centrifugation at 100,000 rpm for 30 min at 25 °C with a second 40% glycerol cushion75. The final pellets were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel (BR4561085, Bio-Rad). After, either Western blotting analysis was performed, or the Coomassie-stained gels were cut into six pieces; each gel piece was digested with trypsin, followed by C18 stage-tip-based desalting.

Data acquisition

The peptides were reconstituted in a solution containing 5% formic acid (FA) and 5% acetonitrile (ACN) for MS analysis and analyzed in triplets using an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano reversed-phase chromatographic platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each dataset fraction was loaded onto an in-house packed 75 μm i.d. × 45 cm C18 column (Reprosil-Pure C18, 1.9 μm, 200 Å, Maisch) kept at 55 °C by a column oven and run at a flow rate of 300 nL/min.

The chromatographic separation of peptides began with 4% solution B (0.1% FA in ACN) and gradually increased to 25% over 70 min. The gradient continued from 25 to 40% solution B over 5 min. Peptides in the mass range of 400–1500 m/z with positive polarity were allowed for detection in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. For MS1 spectra acquisition, the resolution was set to 70,000, the automatic gain control (AGC) target was 3e6, and the maximum injection time was 60 ms. The top 15 most intense peptides per cycle were selected for fragmentation in the higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) cell with normalized collision energy (NCE) 26. MS2 spectra acquisition was performed at a resolution of 17,500, with an AGC target of 5e4, a maximum injection time of 60 ms, and a fixed first mass of 120 m/z. The isolation window was also set to 2.0 m/z, dynamic exclusion was set to 50 ss, and charge exclusion was set as unassigned, 1, >6.

Data processing

MS data were processed using MaxQuant version v2.4.7.0 against the Mus musculus UniProt FASTA database (UP000000589, accessed in July 2022)76. Enzyme specificity was set to trypsin, and the search included cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification and N-acetylation and oxidation (Methionine) as variable modifications. For the dimethyl-labeled samples, in addition to the previous modifications, dimethyl channels (Var DimethNter0, Var DimethLys0, DimethNter8, and Var DimethLys8) were configured as variable modifications. Up to two missed cleavages were allowed for protease digestion. Match between runs was enabled. Default settings were used for other parameters.

The resulting outputs were further processed in Perseus77, Microsoft Excel, and data visualized using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) or Python. For the cortex proteome from the three biological replicates, minimum two values from each control and cKO set were used. For cortex proteome control- or cKO-specific proteins, missing not-at-random values (MNAR) were imputed with the minimal values in each dataset in the cortex proteome. For dimethyl samples and the microtubule-associated network from the two replicates, only values identified in both biological replicates were considered. MNAR in microtubule-associated network were imputed with the half-minimum values in each dataset. Statistical tests for pairwise comparisons were performed using a two-sample, two-tailed Student’s t-test in Perseus. A one-sample t-test was performed for dimethyl labeling experiments, and calculated p-values are reported in the corresponding supplementary data. GO enrichment analysis was performed using g:Profiler and PANTHER GO-Slim with Mus musculus78,79. GO enrichment was determined using default settings as the significance level 0.05. Functionally grouped networks of enriched categories for dysregulated proteins were generated using the ClueGO plug-in of Cytoscape80.

GFP pull-down assay

HeLa Kyoto cells expressing Eml1-GFP or GFP-only were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP-40, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay (23200, Thermo Fisher Scientific). GFP pull-down was performed using GFP-Trap Agarose (gta-100, ChromoTek) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Equilibrated beads were incubated with lysates at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle rotation, then washed three times in lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted by incubating beads in 2× SDS Laemmli buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 100 mM DTT) at 95 °C for 5 min.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane.

Membranes were blotted with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-α-Tubulin (1:1000, 3873, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-GAPDH (1:4000, 97166, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-GFP (1:1000, 11814460001, Roche), rabbit anti-EML4 (1:4000, NBP1-86805, Novus Biologicals), and rabbit anti-Septin 2 (1:2500, 11397-1-AP, Proteintech). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies included anti-mouse (1:2000, 7076, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-rabbit (1:2000, 7074, Cell Signaling Technology). Detection was performed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (1705061, Bio-Rad), and chemiluminescent signals were captured with the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified using Fiji (ImageJ v2.16.0) and normalized to loading controls.

Confocal microscopy

HeLa cells were grown on glass coverslips and fixed in either ice-cold methanol (−20 °C, 10 min) or 4% PFA (room temperature, 15 min), followed by three washes with PBS. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST, 5 min) and blocked with 5% BSA in PBS (1 h).

Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA in PBST: mouse anti-α-Tubulin (1:1000, 3873, Cell Signaling Technology), rat anti-α-Tubulin (1:200, sc-53029, Santa Cruz Technology), mouse anti-acetylated-α-Tubulin (1:100, sc-23950, Santa Cruz Technology), and rabbit anti-EML4 (1:4000, NBP1-86805, Novus Biologicals). After washing with PBST, secondary antibodies were applied: Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse (1:1000, A21202, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 555 anti-mouse (1:1000, 4409, Cell Signaling Technology), Alexa Fluor 555 anti-rabbit (1:1000, A11075, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rat (1:500, A11077, Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 633 anti-mouse (1:500, A21062, Invitrogen). DNA was stained with DAPI-containing mounting medium (ab104139, Abcam).

Confocal images were acquired using a Leica DMi8 SP8 laser scanning microscope with a ×63/1.40 NA oil immersion objective. Z-stacks were collected at 0.5–1.0 µm intervals and processed using LAS X software (v5.3.0, Leica). Image analysis and colocalization quantification (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) were performed using Fiji.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data are presented as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD, as indicated in figure legends. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed t-tests or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in GraphPad Prism (v10.2.1). A p < 0.05 was considered significant. Experiments included at least two biological replicates (n ≥ 2), with most conducted in triplicate (n = 3). Image quantification and colocalization analyses were performed across multiple fields of view. Statistical details for mass spectrometry are in the “Data processing” section. Exact sample sizes, statistical tests, and p-values are provided in the figure legends and Supplementary Data 4. Sample sizes were determined based on previous publications and pilot studies using comparable methodologies, with consideration of assay sensitivity and experimental feasibility. Where appropriate, data collection and analysis were performed in a blinded manner to reduce bias. All experiments were carried out by a primary experimenter to ensure procedural consistency.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD052486. Detailed protein lists for each proteome analysis are provided in Supplementary Data 1–3. All source data underlying the graphs from western blot and immunofluorescence experiments are available in Supplementary Data 4. Uncropped and unedited versions of all western blot images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 5. Any additional information about the data reported in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

This study did not generate custom computer code.

References

Menon, S. & Gupton, S. L. Building blocks of functioning brain: cytoskeletal dynamics in neuronal development. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 322, 183–245 (2016).

Pacheco, A. & Gallo, G. Actin filament-microtubule interactions in axon initiation and branching. Brain Res. Bull. 126, 300–310 (2016).

Kirkcaldie, M. T. & Dwyer, S. T. The third wave: intermediate filaments in the maturing nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 84, 68–76 (2017).

Lasser, M., Tiber, J. & Lowery, L. A. The role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in neurodevelopmental disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 165 (2018).

Stouffer, M. A., Golden, J. A. & Francis, F. Neuronal migration disorders: focus on the cytoskeleton and epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 92, 18–45 (2016).

Romero, D. M., Bahi-Buisson, N. & Francis, F. Genetics and mechanisms leading to human cortical malformations. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 76, 33–75 (2018).

Klingler, E., Francis, F., Jabaudon, D. & Cappello, S. Mapping the molecular and cellular complexity of cortical malformations. Science 371, eaba4517 (2021).

Kielar, M. et al. Mutations in Eml1 lead to ectopic progenitors and neuronal heterotopia in mouse and human. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 923–933 (2014).

Shaheen, R. et al. The genetic landscape of familial congenital hydrocephalus. Ann. Neurol. 81, 890–897 (2017).

Markus, F. et al. A novel missense variant in the EML1 gene associated with bilateral ribbon-like subcortical heterotopia leads to ciliary defects. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 1159–1167 (2021).

Oegema, R. et al. EML1-associated brain overgrowth syndrome with ribbon-like heterotopia. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 181, 627–637 (2019).

Bizzotto, S. et al. Eml1 loss impairs apical progenitor spindle length and soma shape in the developing cerebral cortex. Sci. Rep. 7, 17308 (2017).

Götz, M. & Barde, Y.-A. Radial glial cells: defined and major intermediates between embryonic stem cells and CNS neurons. Neuron 46, 369–372 (2005).

Noctor, S. C., Flint, A. C., Weissman, T. A., Dammerman, R. S. & Kriegstein, A. R. Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature 409, 714–720 (2001).

Noctor, S. C., Martínez-Cerdeño, V., Ivic, L. & Kriegstein, A. R. Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 136–144 (2004).

Uzquiano, A. et al. Mutations in the heterotopia gene Eml1/EML1 severely disrupt the formation of primary cilia. Cell Rep. 28, 1596–1611.e1510 (2019).

Zaidi, D. et al. Forebrain Eml1 depletion reveals early centrosomal dysfunction causing subcortical heterotopia. J. Cell Biol. 223, e202310157 (2024).

Telley, L. et al. Temporal patterning of apical progenitors and their daughter neurons in the developing neocortex. Science 364, eaav2522 (2019).

Kapitein, L. C. & Hoogenraad, C. C. Building the neuronal microtubule cytoskeleton. Neuron 87, 492–506 (2015).

Calafate, S., Flavin, W., Verstreken, P. & Moechars, D. Loss of Bin1 promotes the propagation of tau pathology. Cell Rep. 17, 931–940 (2016).

Mirzaa, G. M. et al. Mutations in CENPE define a novel kinetochore-centromeric mechanism for microcephalic primordial dwarfism. Hum. Genet. 133, 1023–1039 (2014).

Shen, J. et al. Mutations in PNKP cause microcephaly, seizures and defects in DNA repair. Nat. Genet. 42, 245–249 (2010).

Horani, A. et al. The effect of Dnaaf5 gene dosage on primary ciliary dyskinesia phenotypes. JCI Insight 8, e168836 (2023).

Di Bella, D. J. et al. Molecular logic of cellular diversification in the mouse cerebral cortex. Nature 595, 554–559 (2021).

Richards, M. W. et al. Microtubule association of EML proteins and the EML4-ALK variant 3 oncoprotein require an N-terminal trimerization domain. Biochem. J. 467, 529–536 (2015).

Kollman, J. M., Merdes, A., Mourey, L. & Agard, D. A. Microtubule nucleation by γ-tubulin complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 709–721 (2011).

Suprenant, K. A., Dean, K., McKee, J. & Hake, S. EMAP, an echinoderm microtubule-associated protein found in microtubule-ribosome complexes. J. Cell Sci. 104, 445–450 (1993).

Lin, Z. et al. TTC5 mediates autoregulation of tubulin via mRNA degradation. Science 367, 100–104 (2020).

Höpfler, M. et al. Mechanism of ribosome-associated mRNA degradation during tubulin autoregulation. Mol. Cell 83, 2290–2302.e13 (2023).

Bowen, J. R., Hwang, D., Bai, X., Roy, D. & Spiliotis, E. T. Septin GTPases spatially guide microtubule organization and plus end dynamics in polarizing epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 194, 187–197 (2011).

Ghossoub, R. et al. Septins 2, 7 and 9 and MAP4 colocalize along the axoneme in the primary cilium and control ciliary length. J. Cell Sci. 126, 2583–2594 (2013).

Hotta, T. et al. EML2-S constitutes a new class of proteins that recognizes and regulates the dynamics of tyrosinated microtubules. Curr. Biol. 32, 3898–3910.e3814 (2022).

Martinez, C. et al. Platelet septin complexes form rings and associate with the microtubular network. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 1388–1395 (2006).

Sellin, M. E., Holmfeldt, P., Stenmark, S. & Gullberg, M. Microtubules support a disk-like septin arrangement at the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4588–4601 (2011).

Song, K. et al. A SEPT1-based scaffold is required for Golgi integrity and function. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs225557 (2019).

Spiliotis, E. T., Hunt, S. J., Hu, Q., Kinoshita, M. & Nelson, W. J. Epithelial polarity requires septin coupling of vesicle transport to polyglutamylated microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 180, 295–303 (2008).

Hall, P. A., Jung, K., Hillan, K. J. & Russell, S. H. Expression profiling the human septin gene family. J. Pathol.206, 269–278 (2005).

Ali, A., Vineethakumari, C., Lacasa, C. & Lüders, J. Microtubule nucleation and γTuRC centrosome localization in interphase cells require ch-TOG. Nat. Commun. 14, 289 (2023).

Hoang, H. T., Schlager, M. A., Carter, A. P. & Bullock, S. L. DYNC1H1 mutations associated with neurological diseases compromise processivity of dynein–dynactin–cargo adaptor complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1597–E1606 (2017).

Stadler, C., Skogs, M., Brismar, H., Uhlen, M. & Lundberg, E. A single fixation protocol for proteome-wide immunofluorescence localization studies. J. Proteomics73, 1067–1078 (2010).

Tomita, I. et al. SGLT2 inhibition mediates protection from diabetic kidney disease by promoting ketone body-induced mTORC1 inhibition. Cell Metab. 32, 404–419.e406 (2020).

Henderson, N. T. et al. Ephrin-B3 controls excitatory synapse density through cell-cell competition for EphBs. Elife 8, e41563 (2019).

Talamillo, A. et al. Pax6 regulates regional development and neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex. Dev. Biol. 255, 151–163 (2003).

Jabali, A. et al. Human cerebral organoids reveal progenitor pathology in EML1-linked cortical malformation. EMBO Rep. 23, e54027 (2022).

Chou, E. J. & Tang, T. K. Human microcephaly protein RTTN is required for proper mitotic progression and correct spindle position. Cells 10, 1441 (2021).

Shamseldin, H. et al. RTTN mutations cause primary microcephaly and primordial dwarfism in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 862–868 (2015).

Kheradmand Kia, S. et al. RTTN mutations link primary cilia function to organization of the human cerebral cortex. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 533–540 (2012).

Prezel, E. et al. Tau can switch microtubule network organizations: from random networks to dynamic and stable bundles. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 154–165 (2018).

Chen, D. et al. EML4 promotes the loading of NUDC to the spindle for mitotic progression. Cell Cycle 14, 1529–1539 (2015).

Yin, H., Hou, X., Zhang, T., Shi, L. & Su, Y.-Q. Participation of EML6 in the regulation of oocyte meiotic progression in mice. J. Biomed. Res. 34, 44 (2020).

Lyons, D. A., Naylor, S. G., Scholze, A. & Talbot, W. S. Kif1b is essential for mRNA localization in oligodendrocytes and development of myelinated axons. Nat. Genet. 41, 854–858 (2009).

Alsabban, A. H., Morikawa, M., Tanaka, Y., Takei, Y. & Hirokawa, N. Kinesin Kif3b mutation reduces NMDAR subunit NR 2A trafficking and causes schizophrenia-like phenotypes in mice. EMBO J. 39, e101090 (2020).

Tanaka, Y. et al. The molecular motor KIF1A transports the TrkA neurotrophin receptor and is essential for sensory neuron survival and function. Neuron 90, 1215–1229 (2016).

Wheway, G., Nazlamova, L. & Hancock, J. T. Signaling through the primary cilium. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 6, 8 (2018).

Lehtinen, M. K. et al. The cerebrospinal fluid provides a proliferative niche for neural progenitor cells. Neuron 69, 893–905 (2011).

Mu, Z., Wang, L., Deng, W., Wang, J. & Wu, G. Structural insight into the Ragulator complex which anchors mTORC1 to the lysosomal membrane. Cell Discov. 3, 1–10 (2017).

El Khoury, W. & Nasr, Z. Deregulation of ribosomal proteins in human cancers. Biosci. Rep. 41, BSR20211577 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Lysosomal TMEM9-LAMTOR4-controlled mTOR signaling integrity is required for mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Commun. 43, 159 (2023).

Serna, M. et al. The structure of the complex between α-tubulin, TBCE and TBCB reveals a tubulin dimer dissociation mechanism. J. Cell Sci. 128, 1824–1834 (2015).

Adib, R. et al. Mitotic phosphorylation by NEK6 and NEK7 reduces the microtubule affinity of EML4 to promote chromosome congression. Sci. Signal. 12, eaaw2939 (2019).

O’Regan, L. et al. EML4-ALK V3 oncogenic fusion proteins promote microtubule stabilization and accelerated migration through NEK9 and NEK7. J. Cell Sci. 133, jcs241505 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Eml1 promotes axonal growth by enhancing alphaTAT1-mediated microtubule acetylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1871, 119770 (2024).

Richards, M. W. et al. Crystal structure of EML1 reveals the basis for Hsp90 dependence of oncogenic EML4-ALK by disruption of an atypical beta-propeller domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5195–5200 (2014).

Ageta-Ishihara, N. et al. Septins promote dendrite and axon development by negatively regulating microtubule stability via HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2532 (2013).

Kuzmic, M. et al. Septin-microtubule association via a motif unique to isoform 1 of septin 9 tunes stress fibers. J. Cell Sci. 135, jcs258850 (2022).

Sun, T. et al. A comparison of proliferative capacity and passaging potential between neural stem and progenitor cells in adherent and neurosphere cultures. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 29, 723–731 (2011).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013).

Uretmen Kagiali, Z. C. et al. CLIC4 and CLIC1 bridge plasma membrane and cortical actin network for a successful cytokinesis. Life Sci. Alliance 3, e201900558 (2020).

Gibson, D. G. et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 (2009).

Dull, T. et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 72, 8463–8471 (1998).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Bilgic, S. N. et al. EDA2R-NIK signalling promotes muscle atrophy linked to cancer cachexia. Nature 617, 827–834 (2023).

Kagiali, Z. C. U. et al. Systems-level analysis reveals multiple modulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and identifies DNAJB4 and CD81 as novel metastasis inducers in breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics18, 1756–1771 (2019).

Senturk, A. et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics analysis uncovers PAK2-and CDK1-mediated malignant signaling pathways in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 21, 100417 (2022).

Özlü, N. et al. Binding partner switching on microtubules and aurora-B in the mitosis to cytokinesis transition. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 336–350 (2010).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized ppb-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote) omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 (2016).

Reimand, J. et al. g:Profiler—a web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2016 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W83–W89 (2016).

Thomas, P. D. et al. PANTHER: making genome-scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Sci. 31, 8–22 (2022).

Bindea, G. et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 25, 1091–1093 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ceyda Seren Ceyhan for her assistance with the proteomics experiments and all members of the Nozlu lab for their valuable discussions and comments. We also acknowledge the Koç University Proteomics Facility (KUPAM) for the services to support this research. Additionally, we thank the IFM mouse phenotyping facility for their assistance and the CNRS TAAM facility, Orléans, France. We thank Jean-Bernard Manent for his comments on the manuscript and Denis Jabaudon for his guidance. Method illustrations were created with BioRender.com. This project is supported by TUBITAK (218S432) and ERA-Net E-Rare (Heteromics E-Rare18-049), including TUBITAK (122S422), International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) (CRP/23/011) awarded to N.O. and the French ANR (under the frame of E-Rare-3, the ERA-Net for Research on Rare Diseases) and the French Fondation pour la recherche medicale (FRM, Equipe FRM 2020 awarded to F.F. EQU202003010323) and the ANR Ribocortex (ANR-22-CE16-0025-01) projects. The French lab was supported by Inserm and Sorbonne University. D.Z. was supported by an FRM grant FDT202204015115 and Sorbonne University. V.V. was supported by Sorbonne University and an FRM grant (FDT202404018220). F.F. was supported by the CNRS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.N.Y. performed proteomics experiments, statistical analysis, data analysis, and data visualization. D.T. performed cell biology experiments, including microscopy, biochemical assays, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, RT-qPCR, statistical analysis, data analysis, and data visualization. D.T. designed the graphical abstract. D.Z. and V.V. collected the tissue and cell samples. B.A.K. provided instrumental support. F.F. and N.O. initiated and designed the project. N.O. conceived and supervised the study. B.N.Y., D.T., and N.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jin-Wu Tsai and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Tiago Dantas and Dario Ummarino. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yigit, B.N., Tufekci, D., Viola, V. et al. Loss of Eml1 alters microtubule-associated protein networks in mouse brain heterotopia. Commun Biol 8, 989 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08394-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08394-0

This article is cited by

-

Septins in the nervous system: from cytoskeletal dynamics to neurological disorders

Cell Communication and Signaling (2025)