Abstract

The entomophilic roundworm Pristionchus pacificus produces a group of complex ascaroside pheromones (e.g., ubas#1), which are built with various intermediates originating from primary metabolic pathways. However, the exact biosynthetic pathways resulting in the production of these modular pheromones remain enigmatic. Here, the application of a workflow combing bioinformatic tools, CRISPR engineering and chemical analysis supports the discovery of three new carboxylesterases Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-6 and Ppa-UAR-12 from P. pacificus. Ppa-UAR-5 links two simple ascarosides oscr#9 and ascr#12 to the 2’-position of ubas#3 to furnish the biosynthesis of ubas#1 and ubas#2, whereas Ppa-UAR-12 links two ascr#1 at the 4’-position to synthesize dasc#1. Finally, Ppa-UAR-6 is essential for the biosynthesis of npar#1-3 and part#9. The expression patterns of Ppa-uar-6 and Ppa-uar-12 in intestinal and epidermal cells further suggest pheromone biosynthesis is tissue-specific. These findings support the notion that the expansion and subsequent diversification of carboxylesterases in P. pacificus generates complex modular signaling pheromones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The entomophilic roundworm Pristionchus pacificus is a model nematode for evolutionary developmental biology1,2. Most Pristionchus species are found to be ecologically associated with scarab beetles3,4,5, normally arresting as dauer larvae (a developmentally stress-resistant larval stage) on living beetles. These nematodes resume development when bacteria proliferate on beetle carcasses and become available as food source. Like other nematodes of the family Diplogastridae, P. pacificus exhibits a mouth-form dimorphism with the so-called stenostomatous (St) or eurystomatous (Eu) form, a striking example of phenotypic plasticity of feeding structures6. Specifically, St animals have a single tooth and feed on bacteria, whereas Eu animals are equipped with two sharp teeth enabling them to predate on other nematodes7,8,9,10,11,12. As genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 engineering is reliably established in P. pacificus13,14,15,16, this technique allows the in-depth investigation of the regulatory mechanism of mouth-form development and its associated predatory behavior. For example, the combination of forward and reverse genetic tools resulted in the identification of the major regulator of mouth-form plasticity eud-117, and the self-recognition locus self-1 that prevents cannibalism against genetically identical kin12. In addition, P. pacificus excretes signaling molecules referred to as “nematode-derived modular metabolites”, a group of ascaroside pheromones initially characterized from Caenorhabditis elegans18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, which are also found to influence the development of the mouth form and dauer formation33,34,35.

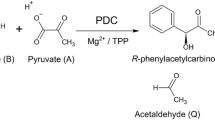

Similar to C. elegans, P. pacificus produces a wide variety of signaling ascarosides33,36,37. However, unlike C. elegans only three simple ascarosides—ascr#9 (asc-C5), ascr#12 (asc-C6) and ascr#1 (asc-C7)—have so far been identified (Fig. 1a). These simple ascarosides harbor an ascarylose sugar linked to the aglycone of a short fatty acid side chain, which are derived from the long chain ascarosides via several cycles of peroxisomal β-oxidation38,39,40,41,42,43,44. In addition, simple ascarosides can act as core structures (Fig. 1a) that are further decorated with additional building blocks to generate three types of complex modular ascarosides (Fig. 1b), including UBAS (3-ureidoisobutyrate ascarosides), DASC (dimeric ascaroside) and PASC (phenylethanolamide ascaroside)33. P. pacificus-produced ascarosides or paratosides are named using four-letter codes “SMIDs” (Small Molecule Identifiers, see the SMID database, www.smid-db.org), for example, ubas#1 and dasc#133. Indeed, each type of modular ascaroside incorporates different kinds of intermediates originating from various primary metabolic pathways. For example, UBAS ascarosides carry a common unit of pyrimidine metabolic pathway-derived ureidoisobutyric acid at the 4’-position, with some complex UBAS ascarosides, like ubas#1 and ubas#2, even separately containing an additional building block of oscr#9 (asc-ωC5) and ascr#12 (asc-C6) at the 2’-position. In contrast, DASC ascarosides are normally comprised of two units of simple ascarosides, which are linked at the 2’- or 4’-position. Finally, P. pacificus produces a group of unique NPAR paratosides including part#9 (paratoside) and npar#1-3 (nucleoside-based paratoside). Based on the structural skeleton of part#9 that is an epimer of ascr#9, npar#1-3 are integrated with additional groups of adenosine-based threonine at their C5 fatty acid side chains (Fig. 1b). So far, only P. pacificus and its closely related species from the genus Pristionchus have been reported to produce these specialized metabolites33,37.

a Chemical structures of simple ascarosides including ascr#9, ascr#12, and ascr#1. b Structures of chemically modified modular signaling molecules (e.g., UBAS, DASC, and NPAR pheromones). c 20 out of 76 candidate genes (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) with homology to Ppa-uar-149 were knocked out by CRISPR/Cas9, from which Ppa-uar-5, Ppa-uar-12, and Ppa-uar-6 genes were shown to regulate the biosynthesis of UBAS, DASC and NPAR pheromones, respectively. d A workflow for screening carboxylesterase genes that are responsible for the biosynthesis of modular pheromones from P. pacificus.

These decorated signaling molecules play critical roles in the regulation of various developmental processes in P. pacificus. For example, the dimeric ascaroside dasc#1 is able to trigger the formation of the Eu mouth form33, while UBAS and NPAR pheromones are capable of inducing dauer formation7,33,34,36,45,46,47,48. Given this complex biochemistry that is in part linked to the developmental decisions which respond to changing environmental influences, we seek to investigate the biosynthetic origins of these modular signaling molecules. While little is known about these biosynthetic pathways, Falcke and co-workers49 previously discovered a key gene Ppa-uar-1 in the genome of P. pacificus by analyzing both metabolomes and transcriptomes of 264 P. pacificus wild isolates. Differences in the metabolome of independent wild isolates were linked to the Ppa-uar-1 gene through a genome-wide association study (GWAS) mapping. Ppa-uar-1 mutants, analyzed by LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry) of both worm culture medium (exo-metabolomes) and worm pellets (endo-metabolomes), showed the absence of UBAS ascarosides, which are characteristic of the attachment of a ureidoisobutyric acid unit at the 4’-position (Fig. 1b). These results indicate for the first time, that the carboxylesterase Ppa-UAR-1 is capable of linking ureidoisobutyric acid to the 4’-position of simple ascarosides to further produce a group of modular UBAS ascarosides (Fig. 1b)49. However, up to date, the downstream factors of the biosynthetic pathway of ubas#1 and ubas#2 have still been elusive, i.e., the exact mechanism of how additional units of oscr#9 and ascr#12 are incorporated into the 2’-position of ubas#3 remains unknown. In addition, the biosynthetic origins of the remaining types of modular signaling molecules are completely uninvestigated. Therefore, it will be important to explore the mechanisms of how different building blocks are integrated into the core structures of simple ascarosides for the biosynthesis of these structurally complex pheromones.

Here, we report the discovery of three new carboxylesterase proteins Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-12 and Ppa-UAR-6 in P. pacificus, which are required for the biosynthesis of UBAS, DASC and NPAR pheromones, respectively (Fig. 1c). Knockout mutants of Ppa-uar-5, Ppa-uar-12 and Ppa-uar-6 led to the loss of specific sets of pheromones in both exo-metabolomes and endo-metabolomes. Ppa-uar-6 and Ppa-uar-12 were further observed to be specifically expressed in the intestine of P. pacificus, which highlights the importance of this tissue for pheromone biosynthesis. The discovery of these biosynthetic proteins provides new opportunities for uncovering the evolution and biological functions of signaling molecules in nematodes.

Results

Knockout of 20 homologs of Ppa-uar-1 by CRISPR/Cas9

To explore the biosynthetic origins of structurally complex pheromones in P. pacificus (Fig. 1b), we hypothesized that homologs of the carboxylesterase Ppa-UAR-149 might play important roles in the formation of these signaling molecules. Bioinformatic analysis of the P. pacificus genome revealed 75 homologs of Ppa-uar-149 and they were renamed as Ppa-uar-x (x marked from 2 to 76) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The amino acid sequences of the homologous UAR proteins were properly aligned and 20 of them were found to be most closely related to Ppa-UAR-1 in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data). Thus, we were motivated to concentrate on these 20 uar genes, all of which were targeted for the creation of knockout mutants through CRISPR/Cas9 engineering (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). We indeed succeeded in generating presumptive null mutants with a total of 57 mutant alleles in these 20 genes (Supplementary Table 1). To study these mutants further, we cultured all the mutant worms in S-medium for the collection of exo-metabolomes and endo-metabolomes (see Methods), followed by LC-MS examination of their pheromonal compositions, which were compared with those of wild type P. pacificus worms (Fig. 1d). This workflow supported the discovery of three new genes encoding for biosynthetic enzymes, i.e., Ppa-uar-5, Ppa-uar-6, and Ppa-uar-12 (Fig. 1c, d). Similar to Ppa-uar-1 in P. pacificus49 and the cest genes in C. elegans32,50,51, these three genes also encode carboxylesterase proteins (esterase or hydrolase) belonging to the α/β-hydrolase-fold enzyme superfamily with a predicted C-terminal transmembrane domain32,50,51. The conserved GXSXG motif containing the catalytic Serine together with the other two catalytic residues Glu and His were also found in Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-6 and Ppa-UAR-12 (Supplementary Fig. 2), which suggests a conserved Glu-His-Ser catalytic triad in UAR proteins. Four conserved Cys residues that are responsible for forming the disulfide bonds of protein structures were also observed (Supplementary Fig. 2). Here, we found that Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-12, and Ppa-UAR-6 separately regulated the biosynthesis of UBAS, DASC, and NPAR pheromones (Fig. 1c). In the following paragraphs, the biosynthetic capacities for each newly identified carboxylesterase are described in detail.

Ppa-UAR-5 functions downstream of Ppa-UAR-1 to furnish the biosynthesis of dauer pheromones ubas#1 and ubas#2

First, we generated three new alleles of Ppa-uar-1 mutants by CRISPR/Cas9 (Supplementary Table 1) to add to the previously reported Ppa-uar-1 mutants49. Indeed, these new mutants did not produce any trace of UBAS ascarosides. Given that both ubas#1 and ubas#2 carry a common building block of ubas#3, these results suggested that ubas#3 might be a biosynthetic precursor of ubas#1 and ubas#249. However, how the remaining two building blocks oscr#9 (asc-ωC5)39 and ascr#12 (asc-C6) (Fig. 1a) are incorporated into the 2’-position of ubas#3 for the biosynthesis of ubas#1 and ubas#2 was still elusive.

To elucidate the biosynthetic pathways of ubas#1 and ubas#2, all of the above-mentioned 57 mutants were maintained in 50 ml liquid culture, and the resulting exo-metabolomes and endo-metabolomes were freeze-dried, extracted by methanol, concentrated and aliquoted for LC-MS analysis (see Methods). Out of these mutants, CRISPR/Cas9 targeting exon 4 of Ppa-uar-5 produced three mutant alleles, including tu2019 that carried an insertion of 68 bp along with 5 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Additionally, the Ppa-uar-5 alleles tu2020 and tu2021 carried deletions of 11 bp and 4 bp, respectively (Fig. 2a). We found that all three alleles of Ppa-uar-5 did not produce ubas#2 anymore, while only trace amounts of ubas#1 remained detectable in the exo-metabolomes (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data). Previously, tiny amounts of ubas#1 were also detected in Ppa-uar-1 mutants49. However, in contrast to the complete absence of ubas#3 in Ppa-uar-1 mutants49, ubas#3 was abundantly produced in Ppa-uar-5 mutants (Fig. 2b, c). Quantitative analysis of the three major UBAS ascarosides in the exo-metabolomes clearly showed that Ppa-uar-5 mutants markedly produced much larger amounts of ubas#3 than wild type worms (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Data), indicating that ubas#3 should act as the biosynthetic precursor of ubas#1 and ubas#2. Furthermore, LC-MS examination of the endo-metabolomes of Ppa-uar-5 mutants also showed that very large amounts of ubas#3 were produced, whereas ubas#1 and ubas#2 completely disappeared (Fig. 2d, e). Together, these experiments suggest that the absence of ubas#1 and ubas#2 was a result of blocking their biosynthetic pathway instead of the excretory process. Thus, Ppa-UAR-5 likely acts on the intermediate precursor ubas#3 and is involved in the biosynthesis of ubas#1 and ubas#2. Therefore, we have identified a new enzyme, Ppa-UAR-5, that acts downstream of Ppa-UAR-1 and is involved in linking oscr#9 and ascr#12 to the 2’-position of ubas#3 to finally furnish the biosynthesis of ubas#1 and ubas#2 (Fig. 2g). Lastly, microinjection experiments were performed to explore the expression patterns of Ppa-uar-1 and Ppa-uar-5. However, we did not succeed in generating fluorescent worms, which might be due to several potential reasons, such as associated toxicity or extremely low level of expression.

a Three mutant alleles of Ppa-uar-5 were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 engineering. b−e The production of UBAS pheromones including ubas#1, ubas#2, and ubas#3 in the exo-metabolomes (b, c) and endo-metabolomes (d, e) of both wild type P. pacificus PS312 and mutants were examined by LC-MS. The pound signs (#) denote non-ascarosides. f Ion abundances of UBAS pheromones in the exo-metabolomes of wild type P. pacificus PS312 and three mutants were quantitatively analysed (n = 3 per group) (Supplementary Data). Error bars represent standard deviation ( ± SD). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns not significant. g Biosynthetic pathway of UBAS pheromones. Ppa-UAR-1 introduced one unit of ureidoisobutyric acid to the 4’-position of simple ascaroside ascr#9 to produce an intermediate ubas#349. Ppa-UAR-5 was responsible for attaching another building block of oscr#9 (asc-ωC5) or ascr#12 to the 2’-position of ubas#3 to finally yield ubas#1 and ubas#2, respectively.

Ppa-UAR-12 regulates the biosynthesis of dimeric ascaroside dasc#1

Utilizing two monomeric building blocks of simple ascarosides, many nematodes including C. elegans52 and its relatives53 are able to produce specific pheromonal content of dimeric ascarosides, each of which harbors an exclusive homo- or heterodimeric structure isomerized through a 2’- or 4’-ester linkage. Extensive chemical investigation of the P. pacificus exo-metabolomes also supports the identification of four dimeric ascarosides dasc#1, dasc#4, dasc#6, and dasc#9 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), from which dasc#1 [4’-(asc-C7)-asc-C7] and dasc#4 [2’-(asc-C5)-asc-C5] represent the two most abundant components33,37. The homodimeric dasc#1 is constructed by connecting two identical monomeric building blocks of ascr#1 (asc-C7) via a 4’-ester linkage (Fig. 1b), whereas another ascaroside dimer, dasc#4, carries two units of ascr#9 (asc-C5), which are instead linked at the 2’-position (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, how two simple ascarosides like ascr#1 and ascr#9 (Fig. 1a) are biochemically processed to yield diverse dimeric ascarosides with different structures and activities is still mysterious. Here, we report a new gene, Ppa-uar-12, encoding the Ppa-UAR-12 enzyme which is capable of establishing a unique 4’-ester linkage for the biosynthesis of dasc#1.

When analyzing the pheromone production in Ppa-uar-12 mutants, we found that all three alleles of Ppa-uar-12 mutants (tu1607, tu1608 and tu1609), carrying deletions of 10 bp, 2 bp and 22 bp in exon 4, respectively (Fig. 3a), did not produce any trace of dasc#1 in their exo-metabolomes (Fig. 3b, c, f and Supplementary Data). In addition, only trace amounts of dasc#1 could be detected in the corresponding endo-metabolome samples (Fig. 3d, e), indicating that the biosynthesis of dasc#1 was abolished in Ppa-uar-12 mutants. However, Ppa-uar-12 mutants were still able to produce other types of pheromones (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Data), suggesting that Ppa-UAR-12 regulates the biosynthesis of dasc#1 and has substrate-specificity on the biosynthetic precursor ascr#1. When we examined dasc#4, a previously identified 2’-linked homodimeric ascaroside37, we found that dasc#4 was present in both the exo- and endo-metabolomes of Ppa-uar-12 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 4a-e and Supplementary Data). These observations suggest that Ppa-UAR-12 is only involved in the biosynthesis of the 4’-linked but not the 2’-linked ascaroside dimer (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4f). This was further supported by the detection of the other two 2’-linked minor dimeric ascarosides dasc#6 and dasc#9 in Ppa-uar-12 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together, these results should demonstrate that Ppa-UAR-12 enables the connection of two monomeric building blocks of ascr#1 and regulates the biosynthesis of dasc#1 via the formation of a specific 4’-ester linkage (Fig. 3g). However, in vitro enzymatic assays will be required in the future to test the promiscuity of Ppa-UAR-12.

a Three mutant alleles of Ppa-uar-12 were generated by CRISPR/Cas9. b−e The production of dasc#1 in the exo-metabolomes (b, c) and endo-metabolomes (d, e) of both wild type P. pacificus PS312 and mutants were examined by LC-MS. f Ion abundances of dasc#1 in the exo-metabolomes of wild type P. pacificus PS312 and three mutants were quantitatively analysed (n = 3 per group) (Supplementary Data). Error bars represent standard deviation ( ± SD). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns not significant. g Biosynthetic pathway of ascaroside dimer dasc#1. Ppa-UAR-12 specifically linked two units of ascr#1 at the 4’-position to biosynthesize dimeric ascaroside dasc#1. h, i Confocal sections and overlaid Nomarski images of the reporter line expressing Ppa-uar-12p::RFP at 5 ng/μL in the intestine. Scale bar of (h) is 100 μm. Scale bar of (i) is 10 μm. White arrows highlighted the nuclear localization of Ppa-uar-12p::RFP. j, k Confocal sections and overlaid Nomarski images of the reporter line expressing Ppa-uar-12p::RFP at 10 ng/μL in the epidermal cells. Scale bar of (j) is 100 μm. Scale bar of (k) is 10 μm. White arrows highlighted the expression of Ppa-uar-12p::RFP in an individual epidermal cell.

P. pacificus-produced dasc#1 has previously been reported to modulate its mouth-form dimorphism by inducing the Eu mouth morph33. We found that all three Ppa-uar-12 mutants defective in dasc#1 production were still capable of forming the Eu mouth form with ratios similar to the P. pacificus wild type animals (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, the abolishment of dasc#1 did not influence the mouth-form dimorphism of P. pacificus, indicating that pheromone signaling and dasc#1 alone cannot override other aspects of mouth-form regulation which resulted in the predominance of the Eu phenotype under the standard laboratory growth conditions.

Dissecting the expression patterns of biosynthetic genes may provide crucial insights into the cellular localization and the identification of the specific tissues responsible for synthesizing target pheromones. To investigate the expression pattern of Ppa-uar-12, a plasmid carrying the coding region of RFP codon-optimized for P. pacificus, under the control of the Ppa-uar-12 promoter was generated14, and stable transgenic reporter lines were obtained after microinjection. Confocal imaging revealed that the biosynthetic gene Ppa-uar-12 was mainly expressed in the intestine of the worms (Fig. 3h). Besides the nuclei of intestinal cells (Fig. 3i), some weak RFP fluorescence was also observed in the epidermal cells (Fig. 3h). When we subsequently generated transgenic lines by injecting higher concentrations of the target DNA with a concentration of 10 ng/μL after linearization, we could further confirm that Ppa-uar-12 was indeed expressed in the epidermal cells of P. pacificus (Fig. 3j, k). Together, we identified a new biosynthetic enzyme Ppa-UAR-12 from P. pacificus and revealed its cellular localization in the intestinal and epidermal cells for the biosynthesis of the dimeric ascaroside dasc#1.

Ppa-UAR-6 is essential for the biosynthesis of dauer pheromones part#9 and npar#1-3

In 2012, a group of NPAR pheromones including part#9 and npar#1-3 (Fig. 1b) was identified in P. pacificus33. All of these paratosides harbor an unusual core structure of paratose probably derived from the common ascarylose sugar via 2’-epimerization33,54, and exhibit the ability to induce dauer formation33,36. So far, only some closely related species of P. pacificus from the pacificus-clade were found to produce NPAR pheromones37. Also, we have not found any clues about the biosynthetic origins of these signaling molecules over the last decade. Here, we identify a new gene Ppa-uar-6 in P. pacificus, which encodes the Ppa-UAR-6 enzyme that is essential for the biosynthesis of both part#9 and npar#1-3.

Three Ppa-uar-6 mutant alleles were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 engineering. While the first allele tu2011 carried a 5 bp deletion in exon 3, the other two alleles tu2012 and tu2013 displayed insertions of 11 bp and 7 bp, respectively (Fig. 4a). LC-MS profiling of the NPAR pheromones from Ppa-uar-6 mutant-derived exo-metabolomes showed that part#9 and npar#1-3 were all lost (Fig. 4b, c, f and Supplementary Data). Similarly, part#9 and npar#1-3 were also fully abolished in the corresponding endo-metabolome samples (Fig. 4d, e). These results represent the first evidence demonstrating that the biosynthesis of NPAR-type pheromones was completely blocked by mutating a specific gene, in this case Ppa-uar-6. In contrast, the other types of pheromones could still be detected from the Ppa-uar-6 mutant worms (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data). Accumulating amounts of ascr#9 in mutant worms were observed when analyzing the production of three simple ascarosides (ascr#9, ascr#12 and ascr#1) (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Data). These observations suggest that ascr#9 should play a role as the biosynthetic precursor of part#9 and npar#1-3, i.e., we hypothesize that Ppa-UAR-6 creates an ester link on ascr#9, resulting in the production of npar#1-3, by connecting tRNA metabolism-derived intermediate33,55,56 to the C5 fatty acid side chain (Fig. 4g). Our findings also suggest that part#9 is derived from ascr#9 via hydrolysis of npar#1-3 (Fig. 4g), which happens downstream of the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway that converts long-chain ascarosides into short-chain ascarosides (e.g., ascr#9) (Fig. 5a)39,41. This was further corroborated by our prior discovery that Ppa-daf-22 mutant animals defective in the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway, did not produce part#9 and npar#1-3 (Fig. 5)41, which should result from blocking the production of their biosynthetic precursor ascr#9. Furthermore, recent studies showed that none of the long-chain paratosides could be detected from Ppa-daf-22 mutants54, which confirmed the short-chain paratoside part#9 should not originate from long-chain paratosides through cycles of the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the biosynthetic mechanism of the short-chain paratoside part#9 is very distinguishable from that of short-chain ascarosides (Figs. 4g and 5).

a Three mutant alleles of Ppa-uar-6 were generated by CRISPR/Cas9. b−e The production of NPAR pheromones in the exo-metabolomes (b, c) and endo-metabolomes (d, e) of both wild type P. pacificus PS312 and mutants were examined by LC-MS. The pound sign (#) denotes non-ascarosides. Inserted ion chromatograms of npar#1-3 were magnified 10 times. f Ion abundances of NPAR pheromones in the exo-metabolomes of wild type P. pacificus PS312 and mutants were quantitatively analysed (n = 3 per group) (Supplementary Data). Error bars represent standard deviation ( ± SD). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns not significant. g Proposed biosynthetic pathway of NPAR pheromones. 1). Ppa-UAR-6 linked tRNA metabolism-derived intermediate to the C5 fatty acid side chain of ascr#9; 2). npar#1-3 were then biosynthesized following an epimerization step; 3). part#9 should be a hydrolysis product of npar#1-3. h−n Section and Nomarski images of a transgenic worm in all developmental stages ((h, i) Young adult; (j, k) J4 larval stage; (l) J3 larval stage; (m) J2 larval stage; (n) J1 larval stage) expressing Ppa-uar-6p::RFP. Scale bar of (h) and (j) is 100 μm. Scale bar of (i) and (k−n) is 10 μm. White arrows highlighted the nuclear localization of Ppa-uar-6p::RFP. o Section and Nomarski images of a male worm expressing Ppa-uar-6p::RFP in the nucleus of intestinal cells. Scale bar is 10 μm. White arrows highlighted the nuclear localization of Ppa-uar-6p::RFP.

a Long-chain ascarosides went through several cycles of peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway41 to yield short-chain ascarosides as the core structures, which could be further chemically modified by divergent carboxylesterases to produce complex modular pheromones. Ppa-daf-22 mutants did not produce any short-chain ascarosides or modular pheromones41. b In this study, Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-12 and Ppa-UAR-6 were discovered to be involved in the biosynthesis of ubas#1-2, dasc#1, and the group of npar#1-3 and part#9 pheromones, respectively. Ppa-UAR-1 was previously found to specifically link ureidoisobutyric acid to the 4’-position of ascr#9 for the biosynthesis of ubas#349.

We generated Ppa-uar-6p::RFP transgenic lines through microinjection. We found the expression of Ppa-uar-6 in the intestine of young adult hermaphrodites (Fig. 4h, i). Notably, earlier developmental stages from J1 to J4 worms (Fig. 4j-n) together with males (Fig. 4o) were also shown to have an identical intestinal expression pattern. Thus, the intestine of P. pacificus serves as the primary site for the biosynthesis of NPAR pheromones. Taken together, our work indicates that the complex P. pacificus pheromones discussed above are synthesized and pooled in the intestinal or epidermal cells.

Future applications of our workflow—genome-wide bioinformatics of genes encoding certain enzyme classes, followed by the systematic generation of gene knockouts, and subsequent LC-MS analysis of mutants—will possibly involve bioinformatic analysis from other Pristionchus and more distantly related nematode species given the many genome sequences are currently available (Fig. 1d). As a proof of principle, we have finally screened the orthologs of Ppa-UAR-6 across 31 Pristionchus species. We found single 1:1 ortholog of the Ppa-UAR-6 enzyme from each of the five Pristionchus species that are most closely related to P. pacificus, i.e. P. taiwanensis, P. kurosawai, P. sikae, P. occultus and P. exspectatus (Supplementary Fig. 10). In contrast, more distantly related Pristionchus species do not contain such 1:1 orthologs of Ppa-UAR-6. This result indicates the recent and ongoing evolutionary diversification of enzymes involved in the production of NPAR pheromones and is in line with our previous findings that NPAR pheromones are only produced by species of the pacificus-clade37.

Discussion

The biosynthesis of plant and microbe-derived secondary metabolites has been intensively studied using many different bacteria and plant species57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. In contrast, the biosynthesis of nematode pheromones is still challenging and has thus far only been investigated in C. elegans and C. briggsae, together with some preliminary studies in P. pacificus32,49,50,51,66,67. Here, we seek to investigate the biosynthetic origins of modular signaling molecules in P. pacificus, each of which exhibits considerable complex chemical structures (Fig. 1b). Previously, only one gene, Ppa-uar-1, had been discovered to be involved in the biosynthesis of UBAS ascarosides from P. pacificus49. In this study, LC-MS analysis of CRISPR/Cas9-generated mutants of 20 homologs of Ppa-uar-1 facilitated the discovery of three carboxylesterase proteins Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-12 and Ppa-UAR-6, which function downstream of the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway (Fig. 5a) to regulate the biosynthesis of UBAS, DASC and NPAR pheromones, respectively (Fig. 5b). These continuous efforts provide a step forward in uncovering the intricate biosynthetic regulatory mechanisms for each type of modular signaling molecules in P. pacificus.

In the future, the application of such a workflow—genome-wide bioinformatics of genes encoding certain enzyme classes, followed by the systematic generation of gene knockouts, and subsequent LC-MS analysis of mutants—will possibly accelerate the discovery of biosynthetic genes for modular signaling molecules from other Pristionchus and more distantly related nematode species (Fig. 1d). Given that the CRISPR/Cas9 technique is widely applicable to knock out genes in Pristionchus species (e.g., P. mayeri)68, it is increasingly feasible to investigate the detailed biosynthetic mechanisms of modular ascarosides in other nematodes. For example, it is very likely that Ppa-UAR-5 is also involved in the biosynthesis of the recently identified UPAS pheromones (Supplementary Fig. 11), given that UPAS pheromones share very similar structures with UBAS37. Similarly, the recent discovery of novel ascarosides from other Caenorhabditis species like C. briggsae53,54,69,70,71, also offers great opportunities to explore their detailed biosynthetic mechanisms32,51,67. Therefore, the workflow described in this study highlights a promising strategy to identify enzymes involved in the regulation of other complex pheromones in nematodes and potentially beyond (Fig. 1d).

Similar to the discovery of the uar genes in P. pacificus, more than 40 homologs of Ppa-uar-1 were identified in the genome of C. elegans, which are referred to as Cel-cest genes. Indeed, five important candidate genes were ascertained to regulate the biosynthesis of different types of modular ascarosides, through the formation of an ester or amide bond32,50,51. For example, the C. elegans sex pheromone ascr#872 is formed by CEST-2.2 through the introduction of a folate metabolic pathway-derived intermediate to the terminal carboxyl group of ascr#7 (asc-▵C7)51. Thus, it will be highly interesting to study the biosynthetic mechanisms and capacities of UAR and CEST proteins in a broader evolutionary context.

Along with the CEST enzymes from C. elegans50,51, all the newly identified proteins Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-6, and Ppa-UAR-12, as well as Ppa-UAR-1, share high similarities of their predicted protein structures (Supplementary Fig. 12) and exhibit high specificity for their substrates. For example, the esterase proteins Ppa-UAR-1 and Ppa-UAR-5 exhibit substrate-specificity on ascr#9 and ubas#3, respectively, by selectively targeting their 4’- and 2’-position for the biochemical reactions (Fig. 2g). Similarly, Ppa-UAR-12 establishes a 4’- but not a 2’-linkage for the biosynthesis of dimeric ascarosides (Fig. 3g). However, to test the selectivity and specificity of these enzymes in more detail will require additional efforts to purify UAR proteins from heterogeneous system to reconstitute the biosynthesis of pheromones in vitro. Currently, we can not completely rule out the promiscuity of some of the studied enzymes.

Based on our experiments and other studies from different laboratories44,50,51,73, the confirmed expressions of the carboxylesterase genes in the intestine and in several epidermal cells further support the notion that these excretory tissues serve as the primary sites for the biosynthesis of nematode signaling molecules. In summary, using a workflow including (i) bioinformatic tools for genome-wide carboxylesterase identification, (ii) CRISPR/Cas9 gene knockouts and (iii) chemical analysis of multiple mutant lines, three new biosynthetic genes Ppa-uar-5, Ppa-uar-12, and Ppa-uar-6 were discovered from P. pacificus. The identified carboxylesterases specifically function in the intestinal and epidermal cells to regulate the biosynthesis of modular pheromones. All of these biosynthetic enzymes exhibit substrate-specificity. This systematic study largely illuminates the intricate biosynthetic mechanisms by which diversification of carboxylesterases in P. pacificus generates complex modular signaling pheromones.

Methods

Nomenclature of ascarosides from P. pacificus

In additional to the four-letter codes “SMID” nomenclature rules (www.smid-db.org), structure-based abbreviations “(head group-)asc-(ω)(Δ)C#(terminal group)” were also used to describe common ascarosides, UBAS ascarosides and NPAR. For those DASC ascarosides consisting of two simple ascaroside units, the first ascaroside was placed in parentheses to differentiate it from the second ascaroside. For example, 4’-linked dimeric ascaroside dasc#1 was named as dasc#1 [4’-(asc-C7)-asc-C7]; 2’-linked dimeric ascaroside dasc#4 was named as dasc#4 [2’-(asc-C5)-asc-C5].

Nematode strains and maintenance

All the mutant nematodes used in this study were listed in the Supplementary Table 1. A mixture of 3 g NaCl, 16 g Agar (Kobe I pulv. 1100 g/cm2), 2.5 g peptone, 1 ml 1 M CaCl2, 1 ml 1 M MgSO4, 25 ml 1 M KPO6 (KH2PO4 and K2HPO4) was dissolved in 1 l distilled water, which was mixed well and autoclaved. Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) agar was prepared by further adding 1 ml 5 mg/ml Cholesterol (in Ethanol) into the sterilized solution. The NGM agar could be poured or pumped into petri plates. Medium size plates (60 mm diameter) were used for general strain maintenance, and larger plates (90 mm diameter) were used for growing large quantities of worms, such as for liquid culture. All the strains of wild type and mutants were maintained at 20 °C on NGM agar plates seeded with E. coli OP50 lawn.

Chemicals and reagents

All the pheromones from P. pacificus PS312 wild type animals have already been elucidated before33,36,37, these known pheromones were applied as standard control for chemical analysis while investigating their biosynthetic pathways. For the target pheromones from CRISPR/Cas9 generated mutants, their retention times, molecular weights and MS/MS fragmentation patterns were carefully and extensively examined by LC-ESI-qTOF-HR-MS, all of which were highly consistent with those from wild type worms (Figs. 2, 3 and 4, Supplementary Data). New biosynthetic intermediates, by-products or end products were not described or discovered from any mutants in this study.

Protein sequence alignment and phylogenetic reconstruction

The amino acid sequence of Ppa-UAR-1 annotated by Falcke et al.49 was used for BLASTP search (e-value < 0.00001) against P. pacificus protein annotations (version 3) on www.pristionchus.org. Seventy-five protein sequences were obtained as the top BLASTP hits. These sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE program (version 3.8.31)74. The resulting multiple sequence alignment was used for a maximum likelihood tree reconstruction using the phangorn package in R (version 4.3.1, model = “WAG + G(4) + I”, optNni = TRUE)75. The best tree model was determined using the pml_bb function. 100 bootstrap replicates were calculated for the midpoint rooted tree and nodes with the standard support values above 50 were visualized on the generated tree in Supplementary Fig. 1.

To examine the conserved Glu-His-Ser catalytic triad, the alignments of amino acid sequences from four functional proteins (i.e., Ppa-UAR-1, Ppa-UAR-5, Ppa-UAR-12 and Ppa-UAR-6) were visualized on Clustal Omega webpage76. The conserved motif and catalytic residues were characterized in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Previously, we have screened all the pheromone compositions from 31 Pristionchus species across the genus of Pristionchus, and only few nematodes from the pacificus-clade were restrictively found to produce NPAR pheromones37. In this study, Ppa-UAR-6 enzyme was discovered to be essential for the biosynthesis of NPAR pheromones. To test the evolutionary consistency, a phylogenetic tree of 1531 homologous proteins of Ppa-UAR-6 across 31 Pristionchus species was constructed in Supplementary Fig. 10. In brief, BLASTP search using default settings (e-value = 10) on the internal BLAST server was applied to screen the protein sequences, which were aligned using the MUSCLE program (version 3.8.31)74,77. The aligned sequences were used to generate a phylogenetic tree on raxmlGUI (version 2.0.10) with an application of the default settings (Model: BLOSUM62; Run mode: ML tree search + bootstrapping (Transfer Bootstrap); Bootstrap replicates: 100)78. The resultant tree was then visualized and annotated on the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform (version 7.2.1)79.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of twenty esterase genes

CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts were generated using previously published protocols in P. pacificus13,14. CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) were designed to target the first, second, third or fourth exon of the gene. crRNAs and tracrRNA (Cat. No. 1072534) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). crRNAs were fused to tracrRNA (IDT) at 95 °C for 5 min, after which the Cas9 endonuclease (Cat. No. 1081058) purchased from IDT was further added. The CRISPR/Cas9 complex was prepared by mixing 0.5 mg/ml Cas9 nuclease, 0.1 mg/ml tracrRNA, and 0.056 mg/ml crRNA in the TE buffer followed by a 10 min incubation at 37 °C. The Ppa-eft-3p::RFP plasmid (20 ng/μl) was added as co-injection marker14. Specific crRNA and primers applied for knocking out each candidate gene were listed in Supplementary Table 3. Microinjections were performed following standard practice using an Eppendorf microinjection system. Injected P0s were removed ca. 16 h post injection. Eggs from each injected P0 animal were allowed to hatch and further transferred onto single NGM agar plates. These F1 animals were genotyped via Sanger sequencing to establish heterozygous null mutant worms. A similar protocol was used to screen homozygous worms in the subsequent F2 generation.

Reporter line of Ppa-uar-12

To construct the transcriptional reporter line for Ppa-uar-12, a 3.0 kb Ppa-uar-12 promoter fragment was amplified from P. pacificus genomic DNA using 2 × Phanta Flash Master Mix (Vazyme, P520). This fragment was cloned into the Ppa-eft-3p::RFP plasmid vector (a gift from Ziduan Han, Northwest A&F University, China) upstream of RFP to substitute the Ppa-eft-3 promoter using ClonExpress Ultra One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, C115) through homologous recombination. DNAs were prepared from multiple independent isolates, then verified by restriction digestion and sequencing. Plasmid DNA and genomic DNA were cut by PstI and injected as two fragments into the gonads of young adult P. pacificus worms at concentrations of 5 ng/μL and 30 ng/μL, respectively, to establish intergenerationally inherited worms that could consistently express RFP fluorescence. Constructs were normally injected at 5 ng/μL or 10 ng/μL. The expression pattern was confirmed in more than three independent lines. Single worms were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope. Stable lines of Ppa-uar-12 were imaged and properly frozen at -80 °C for further usage. Worms recovered from -80 °C were confirmed to consistently express RFP fluorescence.

Reporter line of Ppa-uar-6

Reporter lines of Ppa-uar-6 were constructed using the identical method as described for Ppa-uar-12. Constructs were injected at 10 ng/μL. The expression pattern was confirmed in more than three independent lines. Single worms were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope. Stable lines of Ppa-uar-6 were also imaged and frozen at -80 °C for further usage. Worms recovered from -80 °C were confirmed to consistently express RFP fluorescence.

Preparation of bacterial food source for growing nematodes in liquid culture

LB medium (4 l) inoculated with a single colony of E. coli OP50 was incubated in a shaker at 37 °C with 170 rpm. After one night, E. coli OP50 pellets were collected by centrifugation (Beckman Coulter, Avanti JE 369003, JA10 rotor, 5000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C). The supernatants were removed and resulted E. coli OP50 pellets were transferred into 50 ml falcon tubes for further centrifugation (Cence, H2050R, Swing rotor 0302891036, 4000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C). E. coli OP50 pellets were equally split into six sterilized plastic tubes (50 ml) and stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C for further usage. All the experiments were performed in a clean bench to avoid any potential contamination. Each tube of E. coli OP50 pellet was diluted by adding 10 ml M9 buffer. On the first day, 2.5 ml E. coli OP50 pellets were added into the nematode liquid cultures (50 ml) as their bacterial food source.

Collection of exo-metabolome (culture medium) and endo-metabolome (worm pellets) from mutant worms grown in 50 ml liquid culture

Bleached worms were initially cultured on five NGM plates (9 cm diameter) that were coated with 700 μl E. coli OP50. Using 6 ml M9 buffer to wash worms into a sterilized glass flask containing 50 ml S-medium. On the first day, prepared E. coli OP50 was diluted in 10 ml M9 buffer, and 2.5 ml of diluted E. coli OP50 pellets were added into each flask as bacterial food source. Worm cultures were incubated at 22 °C and 140 rpm for 1 week. Worms were harvested through centrifugation (Eppendorf, Centrifuge 5810 R, FA-45-6-30 rotor, 8000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) to collect the culture medium (exo-metabolome) as well as the worm pellets (endo-metabolome). The resulting exo-metabolome samples were frozen at -80°C for one night and further dried into solid powder by lyophilizer. The solid powder was then extracted three times with 100 ml methanol each. Crude extracts were combined, filtered and dried at 40 °C under reduced pressure to remove organic solvents. Samples were finally dissolved in 1 ml methanol and 100 μl aliquots were applied for LC-MS analysis. The endo-metabolome samples were also frozen at -80 °C for one night and further dried by lyophilization into a solid powder. The dried powder was extracted three times by adding 5 ml methanol each time. Crude extracts were combined, filtered and dried at 40 °C under reduced pressure to remove methanol. Samples were finally dissolved in 0.5 ml methanol and 100 μl aliquots were applied for LC-MS analysis. All the 57 mutant strains were successfully grown in S-medium for chemical analysis. Exo-metabolome and endo-metabolome samples of wild type P. pacificus PS312 were prepared as standard controls. Three biological replicates were performed for each strain.

Chemical analysis of pheromones in exo-metabolomes and endo-metabolomes

Exo-metabolome and endo-metabolome samples were separately dissolved in 1 ml and 0.5 ml methanol. Samples were further filtered and 100 µl aliquots were applied for LC-MS analysis. LC-HR(ESI-)-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II Series HPLC system connected to an Agilent 6546 high resolution qTOF spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization operating in negative ion mode. The HPLC instrument was equipped with an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (250 × 3 mm, 5 µm particle diameter). A mixture of water (H2O + 0.1% Formic acid) and acetonitrile (ACN + 0.1% Formic acid) was used to elute the LC-MS system with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min (an injection volume of 2 µl). The LC-MS system was equilibrated with 3% acetonitrile for 3 min, followed by gradient elution (3%-100% acetonitrile) over 15 min, and finally washed with 100% acetonitrile for 2 min, after which the acetonitrile content of the solvent was decreased to 3% within the next 2 min. After every third sample, a blank MeOH run was performed using the same method. The exo- and endo-metabolomes of mutants were analyzed by LC-MS under the condition of Electrospray ionization (ESI) with Agilent 6546 high resolution qTOF system operating with capillary voltage 3500 V, dry gas flow of 12.0 l/min and dry temperature 275 °C. LC-MS analysis was conducted using the single MS mode by scanning from m/z 50 to 1700. Area (relative ion abundances) of the EIC (Extracted Ion Chromatograms) ion peaks for each individual pheromone in both wild type and mutants were calculated for quantitative analysis (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Agilent Qualitative Analysis 10.0 software was used to calibrate, process and analyze the mass data of mutants and wild type P. pacificus PS312.

Mouth-form phenotyping

The mouth-form dimorphism of tu1607, tu1608 and tu1609 mutants were screened by a Zeiss LSM 980 microscope using standard protocols33. Wild type P. pacificus PS312 was used as control. All the nematodes grown on NGM agar plates were kept in non-starved conditions and crowding of populations was properly avoided. Fresh E. coli OP50 culture was applied as food source. Young adult worms were picked for mouth-form screening (Supplementary Fig. 7). At least ten individual worms for each mutant strain and wild type were selected for mouth-form screening. All the tested worms were equipped with the Eu mouth form. Intermediate or St mouth form was not observed for any strains in this study.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were conducted to determine significance of pairwise differences of pheromone production between mutants and wild type worms by using GraphPad Prism 10.5.0. At least three biological replicates for all the experiments were performed. Data were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance levels were indicated as ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns not significant. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. R version 4.3.1 (www.R-project.org) was used to analyze the phylogenetic relationship of 76 UAR proteins.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the main text and the Supplementary information. Supplementary Data are provided as source data with this paper. Raw LC-MS data that support the findings of this study are available in the Figshare repository with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29648123. Chemical identities of each individual pheromone such as molecular weights and retention times are described in Supplementary Data.

References

Sommer, R. J. Pristionchus Pacificus-a Nematode Model For Comparative And Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 420 (Brill Academic Pubulisher, Nertherlands, 2015).

Schroeder, N. E. Introduction to Pristionchus pacificus anatomy. J. Nematol. 53, e2021-91 (2021).

Herrmann, M., Mayer, W. E. & Sommer, R. J. Nematodes of the genus Pristionchus are closely associated with scarab beetles and the Colorado potato beetle in Western Europe. Zool. (Jena.) 109, 96–108 (2006).

Herrmann, M. et al. The nematode Pristionchus pacificus (Nematoda: Diplogastridae) is associated with the oriental beetle Exomala orientalis (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in Japan. Zool. Sci. 24, 883–889 (2007).

Kanzaki, N. et al. Nine new Pristionchus (Nematoda: Diplogastridae) species from China. Zootaxa 4943, zootaxa.49431 (2021).

Susoy, V., Ragsdale, E. J., Kanzaki, N. & Sommer, R. J. Rapid diversification associated with a macroevolutionary pulse of developmental plasticity. eLife 4, e05463 (2015).

Bento, G., Ogawa, A. & Sommer, R. J. Co-option of the hormone-signalling module dafachronic acid-DAF-12 in nematode evolution. Nature 466, 494–497 (2010).

Bumbarger, D. J., Riebesell, M., Rödelsperger, C. & Sommer, R. J. System-wide rewiring underlies behavioral differences in predatory and bacterial-feeding nematodes. Cell 152, 109–119 (2013).

Wilecki, M., Lightfoot, J. W., Susoy, V. & Sommer, R. J. Predatory feeding behaviour in Pristionchus nematodes is dependent on phenotypic plasticity and induced by serotonin. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1306–1313 (2015).

Sieriebriennikov, B., Markov, G. V., Witte, H. & Sommer, R. J. The role of DAF-21/Hsp90 in mouth-form plasticity in Pristionchus pacificus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1644–1653 (2017).

Sieriebriennikov, B. & Sommer, R. J. Developmental plasticity and robustness of a nematode mouth-form polyphenism. Front. Genet. 9, 382 (2018).

Lightfoot, J. W. et al. Small peptide–mediated self-recognition prevents cannibalism in predatory nematodes. Science 364, 86–89 (2019).

Witte, H. et al. Gene inactivation using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. Dev. Genes Evol. 225, 55–62 (2015).

Han, Z. et al. Improving trangenesis efficiency and CRISPR-associated tools through codon optimization and native intron addition in Pristionchus nematodes. Genetics 216, 947–956 (2020).

Nakayama, K. I., Ishita, Y., Chihara, T. & Okumura, M. Screening for CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations using a co-injection marker in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. Dev. Genes Evol. 230, 257–264 (2020).

Hiraga, H., Ishita, Y., Chihara, T. & Okumura, M. Efficient visual screening of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. Dev. Growth Differ. 63, 488–500 (2021).

Ragsdale, E. J., Müller, M. R., Rödelsperger, C. & Sommer, R. J. A developmental switch coupled to the evolution of plasticity acts through a sulfatase. Cell 155, 922–933 (2013).

Golden, J. W. & Riddle, D. L. A pheromone influences larval development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 218, 578–580 (1982).

Bartley, J. P. Structure of the ascarosides from Ascaris suum. J. Nat. Prod. 59, 921–926 (1996).

Jeong, P. Y. et al. Chemical structure and biological activity of the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer-inducing pheromone. Nature 433, 541–545 (2005).

Butcher, R. A., Fujita, M., Schroeder, F. C. & Clardy, J. Small-molecule pheromones that control dauer development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 420–422 (2007).

Choe, A. et al. Ascaroside signaling is widely conserved among nematodes. Curr. Biol. 22, 772–780 (2012).

Srinivasan, J. et al. A modular library of small molecule signals regulates social behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001237 (2012).

Ludewig, A. H. & Schroeder, F. C. Ascaroside signaling in C. elegans. WormBook 18, 1–22 (2013).

Schroeder, F. C. Modular assembly of primary metabolic building blocks: a chemical language in C. elegans. Chem. Biol. 22, 7–16 (2015).

von Reuss, S. H. & Schroeder, F. C. Combinatorial chemistry in nematodes: modular assembly of primary metabolism-derived building blocks. Nat. Prod. Rep. 32, 994–1006 (2015).

Leighton, D. H. & Sternberg, P. W. Mating pheromones of Nematoda: olfactory signaling with physiological consequences. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 38, 119–124 (2016).

Butcher, R. A. Decoding chemical communication in nematodes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 472–477 (2017a).

Butcher, R. A. Small-molecule pheromones and hormones controlling nematode development. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 577–586 (2017b).

von Reuss, S. H. Exploring modular glycolipids involved in nematode chemical communication. Chimia 72, 297–303 (2018).

Butcher, R. A. Natural products as chemical tools to dissect complex biology in C. elegans. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 50, 138–144 (2019).

Wrobel, C. J. J. & Schroeder, F. C. Repurposing degradation pathways for modular metabolite biosynthesis in nematodes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 676–686 (2023).

Bose, N. et al. Complex small-molecule architectures regulate phenotypic plasticity in a nematode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12438–12443 (2012).

Bose, N. et al. Natural variation in dauer pheromone production and sensing supports intraspecific competition in nematodes. Curr. Biol. 24, 1536–1541 (2014).

Sommer, R. J. Pristionchus-beetle association: towards a new natural history. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 209, 108243 (2025).

Yim, J. J., Bose, N., Meyer, J. M., Sommer, R. J. & Schroeder, F. C. Nematode signaling molecules derived from multimodular assembly of primary metabolic building blocks. Org. Lett. 17, 1648–1651 (2015).

Dong, C., Weadick, C. J., Truffault, V. & Sommer, R. J. Convergent evolution of small molecule pheromones in Pristionchus nematodes. eLife 9, e55687 (2020).

Butcher, R. A. et al. Biosynthesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 1875–1879 (2009).

von Reuss, S. H. et al. Comparative metabolomics reveals biogenesis of ascarosides, a modular library of small-molecule signals in C. elegans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1817–1824 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. Acyl-CoA oxidase complexes control the chemical message produced by Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112, 3955–3960 (2015).

Markov, G. V. et al. Functional conservation and divergence of daf-22 paralogs in Pristionchus pacificus dauer development. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 2506–2514 (2016).

Zhang, X., Li, K., Jones, R. A., Bruner, S. D. & Butcher, R. A. Structural characterization of acyl-CoA oxidases reveals a direct link between pheromone biosynthesis and metabolic state in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, 10055–10060 (2016).

Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Perez, D. H., Jones Lipinski, R. A. & Butcher, R. A. Acyl-CoA oxidases fine-tune the production of ascaroside pheromones with specific side chain lengths. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 1048–1056 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Biosynthetic tailoring of existing ascaroside pheromones alters their biological function in C. elegans. eLife 7, e33286 (2018).

Ogawa, A., Streit, A., Antebi, A. & Sommer, R. J. A conserved endocrine mechanism controls the formation of dauer and infective larvae in nematodes. Curr. Biol. 19, 67–71 (2009).

Mayer, M. G. & Sommer, R. J. Natural variation in Pristionchus pacificus dauer formation reveals cross-preference rather than self-preference of nematode dauer pheromones. Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 2784–2790 (2011).

Mayer, M. G., Rödelsperger, C., Witte, H., Riebesell, M. & Sommer, R. J. The orphan gene dauerless regulates dauer development and intraspecific competition in nematodes by copy number variation. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005146 (2015).

Werner, M. S., Claaßen, M. H., Renahan, T., Dardiry, M. & Sommer, R. J. Adult influence on juvenile phenotypes by stage-specific pheromone production. iScience 10, 123–134 (2018).

Falcke, J. M. et al. Linking genomic and metabolomic natural variation uncovers nematode pheromone biosynthesis. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 787–796.e12 (2018).

Faghih, N. et al. A large family of enzymes responsible for the modular architecture of nematode pheromones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13645–13650 (2020).

Le, H. H. et al. Modular metabolite assembly in C. elegans depends on carboxylesterases and formation of lysosome-related organelles. eLife 9, e61886 (2020).

Bhar, S. et al. An acyl-CoA thioesterase is essential for the biosynthesis of a key dauer pheromone in C. elegans. Cell Chem. Biol. 31, 1011–1022 (2024).

Dong, C., Dolke, F., Bandi, S., Paetz, C. & von Reuss, S. H. Dimerization of conserved ascaroside building blocks generates species-specific male attractants in Caenorhabditis nematodes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 18, 5253–5263 (2020).

Bergame, C. P., Dong, C., Sutour, S. & von Reuss, S. H. Epimerization of an ascaroside-type glycolipid downstream of the canonical β-oxidation cycle in the nematode Caenorhabditis nigoni. Org. Lett. 21, 9889–9892 (2019).

Machnicka, M. A. et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways-2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D262–D267 (2012).

Thiaville, P. C., Iwata-Reuyl, D. & de Crécy-Lagard, V. Diversity of the biosynthesis pathway for threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A), a universal modification of tRNA. RNA Biol. 11, 1529–1539 (2014).

Wink, M. Annual Plant Reviews: Biochemistry Of Plant Secondary Metabolism 40th edn (Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2010).

Crawford, J. M. & Clardy, J. Bacterial symbionts and natural products. Chem. Commun. 47, 7559–7566 (2011).

Donia, M. S. et al. A systematic analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters in the human microbiome reveals a common family of antibiotics. Cell 158, 1402–1414 (2014).

Walsh, C. T. Insights into the chemical logic and enzymatic machinery of NRPS assembly lines. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 127–135 (2016).

Caputi, L. et al. Missing enzymes in the biosynthesis of the anticancer drug vinblastine in Madagascar periwinkle. Science 360, 1235–1239 (2018).

Crits-Christoph, A., Diamond, S., Butterfield, C. N., Thomas, B. C. & Banfield, J. F. Novel soil bacteria possess diverse genes for secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Nature 558, 440–444 (2018).

Tong, Y., Weber, T. & Lee, S. Y. CRISPR/Cas-based genome engineering in natural product discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 1262–1280 (2019).

Nett, R. S., Lau, W. & Sattely, E. S. Discovery and engineering of colchicine alkaloid biosynthesis. Nature 584, 148–153 (2020).

Addington, E., Sandalli, S. & Roe, A. J. Current understandings of colibactin regulation. Microbiology 170, 001427 (2024).

Wyatt, T. D. Pheromones And Animal Behavior: Communication By Smell And Taste 1st edn, Vol. 408 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003).

Cohen, S. M., Wrobel, C. J. J., Prakash, S. J., Schroeder, F. C. & Sternberg, P. W. Formation and function of dauer ascarosides in the nematodes Caenorhabditis briggsae and Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 12, jkac014 (2022).

Yoshida, K. et al. Rapid chromosome evolution and acquisition of thermosensitive stochastic sex determination in nematode androdioecious hermaphrodites. Nat. Commun. 15, 9649 (2024).

Dong, C., Dolke, F. & von Reuss, S. H. Selective MS screening reveals a sex pheromone in Caenorhabditis briggsae and species-specificity in indole ascaroside signalling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 7217–7225 (2016).

Dong, C. et al. Comparative ascaroside profiling of Caenorhabditis exometabolomes reveals species-specific (ω) and (ω-2)-hydroxylation downstream of peroxisomal β-oxidation. J. Org. Chem. 83, 7109–7120 (2018).

Dolke, F. et al. Ascaroside signaling in the bacterivorous nematode Caenorhabditis remanei encodes the growth phase of its bacterial food source. Org. Lett. 21, 5832–5837 (2019).

Pungaliya, C. et al. A shortcut to identifying small molecule signals that regulate behavior and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 7708–7713 (2009).

Artyukhin, A. B. et al. Metabolomic “dark matter” dependent on peroxisomal β-oxidation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2841–2852 (2018).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Schliep, K. P. Phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011).

Madeira, F. et al. The EMBL-EBI job dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W521–W525 (2024).

Rödelsperger, C. et al. Phylotranscriptomics of Pristionchus nematodes reveals parallel gene loss in six hermaphroditic lineages. Curr. Biol. 28, 3123–3127 (2018).

Edler, D., Klein, J., Antonelli, A. & Silvestro, D. raxmlGUI 2.0: A graphical interface and toolkit for phylogenetic analyses using RAxML. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 373–377 (2021).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Frank C. Schroeder for valuable discussions about the biosynthetic pathway of NPAR pheromones. We also thank Dr. Ziduan Han and Dr. Shuai Sun for their assistance with microinjection. LC-MS data and confocal microscopic images were collected by using Waters LCMS, Agilent LC-HR(ESI)-qTOF-MS and Zeiss LSM 980. Mutants were generated by using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing microinjection system. All the instruments were accessed from the Instrumentation and Service Center for Science and Technology (ISCST), Beijing Normal University, Zhuhai. We are grateful to Dr. Wu Wen, Dr. Yuan Gao, Dr. Xianxin Dong and Dr. Pingzhou Du at ISCST for technical supports and data acquisition. This work was funded by the Max Planck Society, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants NO. 22107011, 22407016 & 22477010) and Department of Education of Guangdong Province (Grant NO. 2021KQNCX269).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z., P.T. and W.X. performed experiments and conducted data analysis. S.Y., H.W. and T.L. assisted with microinjection and worm culturing. R.J.S. and C.D. supervised the project. P.Z., P.T., W.X., R.J.S. and C.D. wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. P.Z., R.J.S. and C.D. provided the funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Tuan Anh Nguyen and Laura Rodríguez Pérez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, P., Theam, P., Xu, W. et al. Biosynthesis of modular signaling molecules requires functional diversification of carboxylesterases in Pristionchus pacificus. Commun Biol 8, 1213 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08641-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08641-4