Abstract

The secretion of ligninolytic enzyme provides a competitive advantage for microbial survival. These enzymes are commonly transported to the extracellular milieu via signal peptides for the catabolism of lignin, which cannot be translocated through the cell membrane. However, some bacterial ligninolytic enzymes lack signal peptides, yet they can still be secreted. It remains unclear how these unconventional proteins cross the cell membrane. Here, we reveal a secretion mechanism for the unconventional B-type dye-decolorizing peroxidase (DypB) in Pseudomonas putida A514. Type VI secretion system (T6SS) mediates the inner membrane channel, where interaction of DypB with the T6SS components VgrG and Hcp accounts for periplasmic delivery. Once in the periplasm, DypB is allocated into outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) and released to the extracellular space. The crosslinked translocation model for DypB delivery represents an ingenious mechanism by which bacteria harness extant systems to thrive in a nutrient-poor environment. Moreover, we develop an OMV-surface display platform to improve DypB secretion and further enhance lignin utilization, exemplifying the applicability of OMVs as a lignin biocatalytic nanoreactor. Our study demonstrates the previously unrecognized crosslinking of T6SS and OMVs for the secretion of unconventional ligninolytic peroxidase and provides new perspectives on its biotechnological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microorganisms have evolved secretion systems to adapt to complex natural environments1. These systems play key roles in the transport of proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules, facilitating the microbial competition for resources and space, as well as interaction with the environment2. Lignin, as a prevalent structural component of plants, comprises ~30% of Earth’s non-fossil organic carbon3,4. Microorganisms commonly secrete oxidoreductases, e.g., laccases and peroxidases, for extracellular lignin depolymerization, providing access to the heterogeneous aromatic polymer that cannot translocate the cell membrane5,6. Advances in the understanding of secretion pathways for ligninolytic enzymes have important implications for microbial survival, carbon cycling, and lignin valorization.

Bacterial dye-decolorizing peroxidases (DyPs) have been identified as lignin-oxidizing enzymes. These include the A-type DyP (DypA) in Bacillus subtilis7, the DypBs in Pseudomonas and Rhodococcus8,9,10, and the C-type DyP (DyP2) in Amycolatopsis 75iv211. To date, two major secretion mechanisms for bacterial DyPs have been reported. One involves the Type II secretion system (T2SS) via N-terminal signal peptides. The DypAs in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli were reported to contain a Tat signal sequence12,13. They undergo transmembrane transport via the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway, which recognizes the Tat signal peptide. The other secretion mechanism is dependent on a nano-compartment through a C-terminal signal sequence. In Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, the DypB contains a C-terminal signal sequence that targets it to the neighboring encapsulating nanocompartment. Once encapsulated, it is transported to the extracellular space14,15,16. However, DyPs without any conventional signal peptide can also be secreted to the extracellular surroundings9,17. Taking the DypBs of Pseudomonas putida A514 as an example, algorithm (SignalP, TatP, and SecP) analyses have suggested that they do not contain any of the conventional N- or C-terminal signal sequences (e.g., N-terminal Sec/Tat motifs and C-terminal helical domain and pore-forming β-domain)9. However, our previous studies observed that they can be secreted to the periplasmic and extracellular space9,18, indicating that the secretion of DypBs does not require conventional signal peptides and, therefore, an uncharacterized secretion mechanism mediates the process.

Gram-negative bacteria commonly contain two types of secretion systems that do not require recognition of the classical signal sequences of cargo proteins. One is the Type VI secretion system (T6SS)19,20. This system contains an inner tube composed of Hcp, surrounded by a TssBC outer sheath, and topped by a spiked tip complex of VgrG and PAAR, with a membrane-bound baseplate (TssKEFG), where the ATPase ClpV provides energy for the multicomponent apparatus. It is well-known that T6SS delivers various toxin effectors to neighboring eukaryotic or prokaryotic cells in a contact-dependent manner21. Recent reports suggest that it can also deliver several effectors to the extracellular milieu for metal ion acquisition, in response to environmental fluctuations22,23. In fact, T6SS has a wide range of effectors that display a high diversity in sequence and function. Most of these have no recognizable motifs, especially the single-domain proteins24,25. We hypothesized that P. putida DypB, which lacks any conventional signal peptide, could be transported by T6SS. The other system involves outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), as parts of the unique bacterial secretion pathway type 0 secretion system (T0SS)26,27. OMVs are spherical proteoliposomes, composed of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), glycerophospholipids, and outer membrane proteins28,29. A recent study reported the release of OMVs by P. putida KT2440 containing a set of enzymes to catabolize monomeric lignin-derived compounds, however, the enzymes for lignin depolymerization were absent30. This suggests that OMVs, as an extracellular strategy, assist bacteria in the catabolism of lignin-derived aromatic compounds. We, therefore, inferred that OMVs are harnessed by P. putida A514 to deliver the DypB for the degradation of oligomeric lignin. In addition, OMVs can transport highly concentrated cargo long distances in a protected manner. This unique characteristic enables a diverse range of applications, e.g., vaccination, drug delivery and bioreactors for enzyme cascade reactions31,32. We also expected that these OMVs could be engineered as a nano-bioreactor system for lignin biocatalysis.

Here, we employed the unconventional DypB3152 in P. putida A514 as the subject to investigate this obscure secretion mechanism. Periplasmic protein co-expression network analysis revealed that the protein components of T6SS and T0SS showed positive correlations with DypB3152. Subsequently, the T6SS proteins, especially VgrG, were identified to participate in periplasmic transport of DypB3152. Next, OMVs packaged and delivered the periplasmic DypB3152 to the extracellular surroundings. Moreover, OMVs were engineered as a surface display platform for DypB3152 to harness extracellular enzymatic reactions. This study not only advances our understanding of the crosslinked secretion pathway for the unconventional enzyme, but also provides insights into bacterial OMVs as a promising nanoreactor for lignin biocatalysis.

Results

Proteome analysis reveals the potential roles of T6SS and T0SS in the secretion of unconventional DypB3152

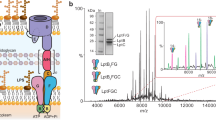

DypB3152 is an Mn2+ independent ligninolytic enzyme in P. putida A514, that lacks any conventional signal peptide9,33. Our previous study observed the periplasmic DypB3152 level and activity in A3152, in which A514 carried the Pmin::dypB3152 expression cassette on the pPROBE-GT plasmid9 (Supplementary Table 1, 2). To reveal the secretion mechanism of DypB3152, the periplasmic proteomes were investigated in A3152 and ApGT (A514 carrying a control vector pPROBE-GT, Supplementary Table 1). The two strains were cultured in M9 medium with either lignin or glucose as the sole carbon source. The corresponding periplasmic proteomes were collected at early- and mid-exponential phases, respectively, and allowed reconstruction of the periplasmic protein co-expression network33. Aligning with the absence of any conventional signal peptide in DypB3152, proteins involved in Type I, II, IV, and V secretion systems were neither identified in the periplasmic proteomes, nor showed significant correlations with DypB3152 (Supplementary Data 1). In contrast, the network revealed that other secretion systems, i.e., T6SS and T0SS, were correlated with DypB3152. Multiple T6SS0137 elements were displayed in the network, and showed strong correlations with DypB3152 (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the expression levels of the T6SS0137 proteins in ApGT were significantly up-regulated under lignin, in comparison to glucose, including DUF17950131, TssA0140 and DotU0147. In addition, A3152, with DypB3152 overexpression, also induced the expression of T6SS0137 proteins (e.g., DUF17950131, VgrG0132, TssA0140 and TssK0143) in the presence of glucose compared to that of ApGT under glucose. Such induced levels were further enhanced when A3152 was cultured under lignin (Fig. 1b), indicating that T6SS might be involved in periplasmic DypB3152 secretion.

a The periplasmic protein co-expression sub-network of DypB3152. The protein components of the secretion systems which were linked to DypB3152 are displayed in the sub-network. Each node represents a protein. Red link: positive correlation, blue link: negative correlation. b Expression levels (log2A) at early exponential phase for proteins involved in secretion. Grey grid indicates that the protein was not expressed. The grid sizes and colors are proportional to the protein levels. L: lignin. G: glucose. Data are shown as mean values from three biological replicates.

Meanwhile, we also observed that OprD4168, BamB4310, and Lpp4245, were strongly correlated to DypB3152 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 1). These outer membrane proteins and efflux pump periplasmic linkers, as the major components of OMVs, participate in the generation and delivery of OMVs34,35. Similarly, they were induced by either lignin or DypB3152 overexpression (Fig. 1b). While these components were all up-regulated in ApGT under lignin, as compared to glucose, their expression levels were also increased in A3152 in comparison to ApGT, when both strains were cultured in the presence of glucose. In addition, the induced levels were also observed in A3152 under lignin, compared to ApGT under glucose. Thus, we inferred that periplasmic DypB3152 is possibly transported to the extracellular space by OMVs.

T6SSs participate in the periplasmic transport of DypB3152

Proteome analysis demonstrated that the T6SS0137 elements were co-expressed with DypB3152. Subsequent genome analysis showed that the A514 strain harbors multiple T6SS gene clusters, including the 0137 cluster, 2469 cluster, and 5262 cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1). The three T6SS gene clusters all encode multiple components, e.g., Hcp (inner tube), VgrG and PAAR (tip complex), ClpV (ATPase), and VasF/VasK (baseplate components). Among them, the T6SS0137 cluster contains the integral elements, consisting of 17 proteins, while the T6SS2469 and T6SS5262 clusters lack ClpV and VgrG, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, two individual vgrG gene clusters, 0499 and 5775, were also detected in the A514 genome (Supplementary Fig. 1). To explore whether the secretion of DypB3152 is mediated by T6SS, the four vgrG genes, as the classical carrier for T6SS effectors36,37, were respectively deleted in the AR3152 strain. AR3152, which integrated genome editing elements (Cas9n and λ-Red) into the A3152 chromosome, displayed similar DypB3152 protein expression levels to A3152 (Supplementary Fig. 2), and was therefore used as the host strain to investigate the periplasmic DypB3152 secretion. The resulting mutant strains were designated A∆vgrG0132, A∆vgrG0499, A∆vgrG2455 and A∆vgrG5744 (Supplementary Table 1). Western blot assays showed that deletion of vgrG0132 and vgrG2455 led to a significant reduction (63–65%) in the DypB3152 protein levels in the periplasmic space, while it did not impair the DypB3152 protein levels in total cell lysates (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Consistent with the decreased expression levels, we also detected inhibited periplasmic DypB3152 activities in the strains A∆vgrG0132 and A∆vgrG2455, by 50-54% (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the A∆vgrG0132::vgrG0132 and A∆vgrG2455::vgrG2455 mutants almost completely alleviated the diminished protein levels, when we complemented the vgrG0132 and vgrG2455 genes in A∆vgrG0132 and A∆vgrG2455, respectively (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). These complementation strains correspondingly recovered DypB activity by 86-90% (Fig. 2d). In addition, A∆vgrG5744 and A∆vgrG0499 slightly decreased periplasmic protein levels (7-13%) and enzyme activities (3-9%, Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3a, p > 0.05). To further explore the roles of the four VgrGs, the double knockout mutant A∆2vgrG (∆vgrG0132∆vgrG2455) and quad-gene knockout mutant A∆4vgrG were constructed, respectively. Both knockouts exhibited substantially reduced periplasmic protein level (66–77%) and enzyme activity (59-63%), compared to AR3152 (Fig. 2e–f and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Together, the results demonstrated that VgrGs play a role in the periplasmic secretion of DypB3152, of which VgrG0132 and VgrG2455 are the most important components.

a, c, e Western blot analysis of the DypB3152 expression levels in the total cell lysates (Cell) and periplasmic (Peri) space of the relevant ∆vgrG mutants. The periplasmic protein, DsbA, was used as the periplasmic loading control. The cytoplasmic protein, RNA polymerase beta subunit (β-RNAP), was used as the loading control for total cell lysates. AR3152 was used as the control strain. Data are representative of three biological replicates. b, d, f The corresponding periplasmic DypB3152 activity of the ∆vgrG mutants. U/L: the DypB3152 activity per 1 L culture broth. “*”: p value < 0.05, “**”: p value < 0.01, “***”: p value < 0.001 by two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. n = 3 biological replicates.

Next, the T6SS components of the 0137 cluster were investigated, due to the integrity of T6SS0137 cluster and the importance of VgrG0132 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 1). The paaR0130, duf17950131, clpV0133, and hcp0137 genes, which have been reported to influence T6SS effector delivery23,38,39,40, were individually deleted in AR3152. We found that these mutants slightly reduced (9-12%) the abundance and activity of periplasmic DypB3152, each exhibiting a minor effect on DypB3152 secretion (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 4a). To further determine the synergistic effect of the five T6SS0137 components on DypB3152 secretion, the quad-gene deletion mutant A∆4-0132 (∆paaR∆duf1795∆vgrG0132∆clpV) and five-gene disruption mutant A∆5-0132 (∆paaR∆duf1795∆vgrG0132∆clpV∆hcp) were both constructed to inactivate the T6SS0137 system. Compared to AR3152, these decreased the periplasmic DypB3152 abundances by 63-71%, but did not interfere with DypB3152 expression levels in total cell lysates (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Correspondingly, the two mutants also reduced periplasmic DypB3152 activities by 53-60% (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, A∆5-0132, instead of A∆4-0132, exhibited significantly lower activity than A∆vgrG0132, indicating Hcp0137 could work synergistically with other T6SS components for periplasmic DypB3152 transport, although the hcp0137 deletion, by itself, did not significantly inhibit the secretion of DypB3152 (Figs. 3c, e and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Overall, the data revealed that T6SS0137 plays a role in the periplasmic transportation of DypB3152, of which VgrG0132 had the greatest effect on secretion.

a The T6SS0137 gene cluster in P. putida A514. b, d Western blot analysis of DypB3152 expression levels in the total cell lysates (Cell) and periplasmic (Peri) space of the indicated strains. The proteins DsbA and β-RNAP were used as the protein expression controls, while AR3152 was used as the control strain. Data are representative of three biological replicates. (c, e) Periplasmic DypB3152 activity in the corresponding ∆T6SS0137 mutants. “*”: p value < 0.05, “***”: p value < 0.001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. n = 3 biological replicates. f–j Interactions between DypB3152 and targeted proteins. The initial samples (Input) and retained proteins (IP) were analyzed by western blot against Flag and Myc antibody, respectively. IgG indicates the negative control antibody group. Data are representative of two biological replicates.

To further verify whether VgrG0132 acts as the carrier for the secretion of DypB3152, the interaction between DypB3152 and VgrG0132 was tested by co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) assay. As expected, DypB3152 retained VgrG0132, indicating that VgrG0132 carries DypB3152 across the inner membrane (Fig. 3f). To investigate the potential interactions of DypB3152 with additional T6SS0137 components, co-immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry (coIP-MS) was performed in P. putida A514, carrying the FLAG-tagged DypB3152 vector, while A514 with the FLAG-tagged vector acted as the control (Supplementary Table 1-2). Proteins that coeluted with DypB3152 were preliminarily identified by mass spectrometry. Eighty-one proteins, absent in the control, were identified (Supplementary Data 2). A refined subset of three proteins was targeted and further examined by coIP, as they were T6SS0137 components (DUF17950131, Hcp0137, and DotU0144). The assay showed DypB3152 could retain Hcp0137, but not DUF17950131 and DotU0144, suggesting interaction between DypB3152 and Hcp0137 (Fig. 3g–i). Moreover, an interaction between VgrG0132 and Hcp0137 was observed via coIP (Fig. 3j), suggesting that DypB3152, VgrG0132, and Hcp0137 might form a trimer complex. Overall, these results demonstrated that DypB3152 can be delivered to the periplasm via the T6SS0137 system.

T0SS mediates extracellular secretion of DypB3152

As DypB3152 was not detected in the culture supernatants, the extracellular secretome of P. putida A514 was investigated via scanning electron microscopy (SEM), (Fig. 4a). The observation of small (60~150 nm) nanoparticles validated that P. putida A514 secreted OMVs to the extracellular space (Supplementary Fig. 5). To further verify our hypothesis that these OMVs packaged and transported the periplasmic DypB3152 to the extracellular space, DypB3152 in A3152 was successively assayed in the total cell lysates, periplasm, supernatants, and OMVs by western blot assay (Fig. 4a). DypB3152 was present in the total cell lysates, periplasm and OMVs, but not in the culture supernatants, confirming that DypB3152 is trafficked to the extracellular space via OMVs (Fig. 4a). Subsequently, the location of DypB3152 in OMVs was examined. After treatment of the OMVs with proteinase K to digest proteins on their surfaces, DypB3152 could still be detected in the OMVs. In contrast, the well-known OMV surface protein, OprF41, was digested by proteinase K (Fig. 4b). Moreover, when we lysed the OMVs with SDS and then digested their proteins by proteinase K, DypB3152 was not detected (Fig. 4b). In view of these results, we posited that DypB3152 is incorporated into OMVs for delivery across the outer membrane. To further examine whether T6SS influences the delivery of DypB-containing OMVs, we detected the extracellular DypB3152 in the T6SS-deficient mutants. Similar protein levels were detected between the periplasm and OMVs in the T6SS-deficient mutants, while the protein levels in total cell lysates were not impaired (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 6). It confirmed that T6SS was responsible for periplasmic transport, while OMVs play a role in extracellular secretion.

a Western blot analysis of the DypB3152 in the total cell lysates (Cell), periplasm (Peri), supernatants (Sup) and OMVs of P. putida A3152. 80 µg total protein per sample was used to detect the DypB3152 level. b Western blot analysis of DypB3152 location in the OMVs of A3152. OprF, the OMV surface protein, was used as the positive control. c Western blot analysis of the DypB3152 expression levels in the OMVs, periplasmic fractions and total cell lysates of the relevant T6SS-deficient mutants. The proteins DsbA and β-RNAP were used as the protein expression controls, while AR3152 was used as the control strain. Data are representative of two biological replicates.

Taking the above results together, we propose a secretion model for the DypB3152 protein in P. putida A514 (Fig. 5a). It is transported in a two-step process across the inner and outer membranes. DypB3152, as the T6SS-associated cargo, passes through the cytoplasmic membrane via T6SS0137. VgrG0132 and Hcp0137 interact with each other to act as the carriers for DypB3152 transportation across the inner membrane via the baseplate of the T6SS. VgrG2455 also assists in the transmembrane transport. Once in the periplasmic space, DypB3152 is incorporated into OMVs and exported through outer-membrane trafficking.

a Model for delivering DypB3152 to the extracellular space. DypB3152, VgrG, and Hcp interact with each other and then are shuttled across the inner membrane via the T6SS baseplate components. VgrG and Hcp could assemble into the T6SS apparatus, while the periplasmic DypB is then incorporated into OMVs. The OMV-coated DypB is finally delivered to the extracellular space. b Schematic illustration of the bio-designed DypB3152 nanoreactor for lignin biocatalysis. DypB3152 is first displayed on the surface of OMVs, and then the OMV yield is increased by genetic manipulation and OVAT. The synthetic nanoreactor can efficiently deliver DypB on the surface of OMVs, contributing to lignin degradation.

Bio-designed DypB3152 secretion to develop a lignin biocatalytic nanodevice

As stated earlier, DypB3152 is not located on the surface of OMVs. Its absence in the culture supernatants further indicated the low DypB3152 secretion efficiency. Consequently, we attempted to efficiently display DypB3152 on the surface of OMVs to improve accessibility to the substrate. First, as previously reported9, an expression vector (pUCP18-Gm) with a higher copy number was used to enhance the level of periplasmic DypB3152 expression level, generating the A3152B strain. Second, fused expressions with various surface-anchoring proteins were tested in the A3152B strain. DypB3152 was correspondingly fused to SylB1424, LolB2050, OprF3701, and OprD4168, generating the recombinant strains ASylB, ALolB, AOprF, and AOprD, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Western blot assays suggested two (ASylB and ALolB) of the four strains, packaged DypB3152 in the OMVs (Fig. 6a). Proteinase K treatment confirmed they successfully displayed DypB3152 on the surface of OMVs, with up to 0.87 U/mg of OMV total proteins in ASylB (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Together, we developed two nanodevices that successfully displayed active DypB3152 on the surface of OMVs.

a Western blot analysis of the four DypB3152 fused proteins in the OMVs. β-RNAP was used as the protein expression negative control to exclude the cytoplasmic contamination in OMV samples. A3152B was used as the control strain. b Western blot analysis of the DypB3152 location in the ASylB and ALolB OMVs. OMVs were treated with (+) or without (-) proteinase K. Data in (a, b) are representative of two biological replicates. c The OMV yield in the corresponding ∆tolA mutants. The OMV yield is indicated by the total protein of the OMVs in 1 L of culture broth. d The DypB activity on the surface of OMVs in the ASylB∆tolA and ASylB∆tolR strains. The optimized DypB protein level (e) and activity (f) in the culture supernatants. The protein level was quantified by ELISA assay. g, h Cell growth and lignin degradation by the ASlyB∆tolA strain. AR3152 and A∆tolA were used as the control strains, respectively. Data in (c–h) are presented as mean values ± standard deviation, n = 3 biological replicates. “*”: p value < 0.05, “**”: p value < 0.01, “***”: p value < 0.001 by two-sided Student’s t-test. i The FTIR spectrum of untreated lignin and treated lignin by A3152B, A∆tolA, and ASlyB∆tolA, respectively. Data are representative of three biological replicates. The P. putida strains (a–f) were cultured in LB medium, while the strains (g–i) were cultured in 0.3% kraft lignin-M9 medium, supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract and 2 mM MnSO4 for DypB production.

Next, the nanodevice yield was enhanced by mutation of the Tol-Pal system. Because the mutation of tol-pal operon increases the release of OMVs in many bacteria42, the genes tolA4149 and tolR4151 in the tol-pal operon were individually deleted in A3152B, ASylB and ALolB, generating the six mutants A∆tolA, ASylB∆tolA, ALolB∆tolA, A∆tolR, ASylB∆tolR, and ALolB∆tolR (Supplementary Table 1). Mutation of either tolA4149 or tolR4151 resulted in a more than a ~2-fold increase in OMV yields (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 7b). Moreover, both ASylB mutants showed slightly higher OMV yields than the ALolB mutants, up to 15 mg/L OMVs in ASylB∆tolA (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 7b). Correspondingly, the secretions of DypB3152 protein were significantly improved in these ASylB mutants (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). The highest activity on the surface of OMVs was observed in the ASylB∆tolA strain, achieving 1.44 U/mg of OMV total proteins (Fig. 6d).

Therefore, ASylB∆tolA was targeted for the optimization of extracellular DypB3152 yield by the classical one variable at a time (OVAT) method. Five parameters were tested to improve DypB3152 production at the levels of transcription and translation (Supplementary Table 3). (i) The transcription level of dypB3152 was optimized by using different concentrations of xylose to induce the xylose-dependent promoter PxylA. (ii) Four cultivation parameters were examined to improve the DypB3152 protein level, including medium, pH, temperature, and D-cycloserine (the inducer for OMVs production43). Among these, D-cycloserine, medium, and pH showed greater effects on extracellular DypB3152 production. As a result, the extracellular DypB3152 protein level and activity could be directly detected in the culture supernatants of ASylB∆tolA. The nanodevice yield reached 24.03 ng/mL DypB3152, with 8.21 U/mL activity (Fig. 6e, f). In contrast, neither A3152B nor A∆tolA showed the detectable DypB3152 protein level in the culture supernatants (Fig. 4e, f). Finally, ASylB3152∆tolA was cultured under kraft lignin to test the biocatalytic effect of the engineered DypB3152 nanodevice. Significant growth improvement was observed in ASylB3152∆tolA, with ~2.6-fold enhancement over A3152B (Fig. 6g). Moreover, 2.4-fold higher lignin was utilized by ASylB3152∆tolA, reaching 12% (Fig. 6h). Lignin degradation was further assessed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). It revealed the evident changes in the chemical bonds of kraft lignin by ASylB3152∆tolA, A∆tolA and A3152B, as compared to the blank (Fig. 6i). The changes mainly ranged from 1045 to 3418 cm−1, especially at 1045, 1329, 1510, 1600~1750, 2940 and 3418 cm−1 (Fig. 6i). The spectral band at 1045 cm−1 was associated with C-O stretching in the aliphatic ethers of lignin44; the band at 1329 cm−1 might be due to the C−H vibration of the S-unit45; the band at 1510 cm−1 could be attributed to the C=C stretching vibration of the aromatic ring46; the bands at 2940 and 3418 cm−1 were assigned to the asymmetric C−H and O-H stretching vibrations in the aliphatic chains of lignin47. Interestingly, in contrast to A∆tolA and A3152B, the characteristic peak of lignin by ASlyBΔtolA was weaker. It is consistent with the results of extracellular DypB3152 activity, cell growth, and lignin utilization assays (Fig. 6e, h), further illustrating the lignin biocatalytic effect of the DypB3152 nanodevice. Taken together, these results demonstrated that the DypB3152 nanodevice has a potential application in lignin biocatalysis (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

In bacteria, secreted cargoes commonly contain conserved motifs for recognition by transporters. For instance, C-terminal signal peptides can be interacted with ABC transporters in type I secretion systems (T1SS)48,49, or bound by VirD4/VirB proteins in type IV secretion systems (T4SS)50, while N-terminal signal peptides (e.g., Sec and Tat) are recognized by either the SecB-dependent pathway51 or twin-arginine translocation pathway52 in type II and V secretion systems (T2SS and T5SS), respectively. In addition, the N-terminal domain of some T6SS effectors also has specific motifs, e.g., rearrangement hotspots (RHS), YD repeats, MIX motifs and FIX motifs25,53,54. How a protein without any classical signal peptide traverses the inner and outer membranes has been a major question in this field, as ascribing it to only cytoplasmic/periplasmic leakage has been unconvincing. Here, we found a crosslinked translocation model, providing an answer to this question (Fig. 5a). First, VgrG-dependent T6SS periplasmic transportation was revealed. The T6SS components, VgrG and Hcp, localize to the inner membrane20. DypB3152 interacts with these components. It is inferred to form a DypB3152-VgrG-Hcp trimeric complex, which could be further investigated by crystallization and structural determination in the future55. This complex is then shuttled across the inner membrane via the T6SS baseplate components. Once in the periplasm, DypB3152 could be released from the complex. VgrG proteins should assemble into a trimeric complex as a spike, while Hcp rings may dock beneath it and form a long flexible tube56. It is worth noting that deletion of hcp did not significantly impair periplasmic DypB3152 protein level or activity (Fig. 3b, c). Therefore, DypB3152 is not a Hcp-associated effector, although it shows an interaction with Hcp (Fig. 3g). This is possibly related to the size of DypB3152 (32 kDa). Hcp-dependent effectors typically have a low molecular weight, under 20 kDa57. A large protein (>30 kDa) would arrest Hcp ring assembly and secretion, despite it not impairing the interaction58. Each interaction among DypB3152, Hcp, and VgrG should enhance the association of DypB3152 with T6SS and further contribute to its transport across the inner membrane. Subsequently, the periplasmic DypB3152 is incorporated into OMVs, and the OMV-encapsulated DypB3152 is finally delivered to the extracellular space (Fig. 5a). T6SS-mediated recruitment of OMVs has been reported, where LPS-binding effectors, being secreted by T6SS, recruit OMVs for bacterial competition and horizontal gene transfer59. Here, we reveal the unrecognized interconnection for the delivery of a ligninolytic enzyme, representing an ingenious mechanism by which bacteria harness extant cellular processes to thrive in a dynamically changing environment.

Importantly, T6SS-mediated periplasmic DypB3152 delivery has several unique features. First, DypB3152 is identified as a T6SS-associated cargo for carbon utilization, further elucidating the diverse functions of T6SS. The well-known T6SS effectors, which include toxins2 and proteins for metal ion acquisition, e.g., molybdate-binding protein (ModA)60, are commonly located in the same operon together with their cognate VgrG, Hcp, or PAAR proteins39,61. Genome analysis revealed that the gene for DypB3152 is distant from the T6SS0137 and T6SS2469 clusters. Additionally, the classical N-terminal motifs, e.g., RHS, YD repeats, MIX, and FIX motifs, were not identified in DypB3152. Our study expands the T6SS substrate repertoire and pinpoints that T6SS participates in ligninolytic enzyme trafficking, providing a survival advantage in the absence of labile carbon sources. Second, T6SS mediates DypB3152 transportation from the cytoplasm to the periplasm. T6SS has been reported to directly deliver effectors to the extracellular milieu or neighboring cells, bypassing the periplasm23,62,63. Alternatively, periplasmic proteins (e.g., ModA) are transported by T6SS from the periplasm to the extracellular space, where VgrG and Hcp are considered to be assembled in the periplasm60. Here, we reveal that DypB3152 can be delivered to the periplasm via the interaction with VgrG and Hcp, even though they might not yet have assembled into a needle-shaped structure. Third, while T6SS contributes to DypB3152 secretion, it is not entirely relied upon. For T6SS specialized effectors, deletion of any effector-bound T6SS component (e.g., VgrG, Hcp, and ClpV) would fully prevent their secretion23,64. In contrast, neither the deletion of the four vgrG genes nor the five genes in T6SS0137 could completely prevent DypB3152 secretion in this study, with 23-29% of periplasmic protein levels still retained (Figs. 2, 3). Considering that DypB3152 also showed significant correlations with other transport proteins, e.g., TtgA (an efflux pump)65 and FtsY (the signal recognition particle receptor)66, SotB0592 (sugar efflux transporter)67 and DUF (the domain of unknown function)68 (Supplementary Data 1), we inferred DypB3152 might not be a specific substrate of T6SS in P. putida, confirming the view that bacteria could engage underutilized systems to transport additional substrates in response to natural environment fluctuations69.

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), also called T0SS, can function as nanoscale vectors for the encapsulation and transport of highly concentrated enzymes with long-distance delivery70. They have gained attention for their broad functions (e.g., intercellular interactions, virulence, and nutrient acquisition)71,72,73, and potential applications (e.g., vaccine and drug delivery vectors)74,75. Here, we expanded their utilization in recalcitrant carbon catabolism, which would aid in developing microbial strategies for lignin valorization. OMV catabolism of lignin-derived aromatic compounds has been observed in P. putida KT244030. A set of enzymes for monomeric lignin-derived compounds was packaged in OMVs and delivered into the extracellular milieu. However, the enzymes for lignin depolymerization were absent in the KT2440 OMVs. In our study, we revealed that DypB3152, with its characterized lignin depolymerization activity9,10,33, was packaged into OMVs in P. putida A514.

Undoubtedly, OMVs, enriched in a diverse array of enzymes, are a promising lignin valorization nano-bioreactor with unique advantages. Lignin greatly induces OMV biogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 8c-d). Extracellular OMVs ensure enzymatic access to lignin, a substrate that cannot translocate through the microbial cell membranes. Meanwhile, the low molecular weight catabolic products are easily taken up by the recipient cells. The natural spatial separation can also mitigate substrate toxicity. However, the limited DypB3152 secretion in A3152 should be acknowledged (Fig. 4a). Moreover, DypB3152 is likely located inside the OMVs, restricting its direct access to lignin. Here, we developed an OMV-surface display platform to engineer this natural nano-bioreactor (Fig. 5b). DypB3152, in conjunction with a tethering outer membrane lipoprotein (e.g, SylB and LolB)76,77 was successfully displayed on the surface of OMVs, facilitating lignin accessibility. Moreover, the level of DypB3152 in the nanobioreactor was further improved, via an increase of the OMV and DypB3152 yields, reaching 24.03 ng/mL DypB3152 in the culture supernatants. Consequently, the engineered extracellular nano-bioreactor significantly promoted lignin utilization and cell growth, aligning with the ΔdypB mutant of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 which had greatly reduced lignin degradation activity8. Our work provides an efficient synthetic biological tool for lignin utilization.

In conclusion, this study reveals a mechanism for the secretion of unconventional DypB3152 in P. putida, involving in the coordinated action of T6SS and T0SS. Our study not only recognizes DypB3152 as a T6SS-associated protein but also demonstrates that periplasmic secretion can be mediated by T6SS, a previously unknown trait. Moreover, we uncover that a ligninolytic enzyme can be secreted via OMVs in P. putida, a mechanism in which only the delivery of aromatic compound catabolic enzymes had previously been observed30. Importantly, an OMV-surface display platform was developed to exemplify the applicability of bacterial OMVs as a lignin biocatalytic nanoreactor. Though still in its infancy, the rational construction and display of artificial multi-enzyme complexes on this nanoreactor system in the next step would greatly enhance lignin biocatalysis.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The strains used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Escherichia coli Mach I (TransGen Biotech) was grown on Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium at 37 °C, 150 rpm, which was used for all molecular cloning manipulations. P. putida A514 and its mutants were grown on either LB medium or M9 medium (3 g/L KH2PO4, 6 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 1% 100 × Goodies mix (2.87 g/L MgCl2-6H2O, 0.25 g/LCaCO3, 0.56 g/L FeSO4-7H2O, 0.18 g/L ZnSO4-7H2O, 0.11 g/L MnSO4-H2O, 0.03 g/L CuSO4-5H2O, 0.03 g/L CoCl2-6H2O, 0.008 g/L H3BO3, 24.07 g/L MgSO4, 1.11 g/L CaCl2, 0.03 g/L VB1))9,78 supplemented with either 15 mM glucose or 0.3% (w/v) kraft lignin at 30 °C, 150 rpm, respectively. The lignin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA (catalog # 370959). It is insoluble in water and was extracted by the hot alkaline (sulfate) method9. To enhance DypB production, 0.2% yeast extract and 2 mM MnSO4 were added to the M9 medium, as previously reported9. The optical density at an absorbance of 600 nm (OD600) was measured to evaluate the cell growth in LB or M9 medium with glucose, while cells per milliliter were monitored by plate count to indicate cell growth under lignin9. All growth experiments were performed with three biological replicates.

Plasmid and mutant construction

All plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4, respectively. Plasmids were constructed according to standard molecular cloning protocols and were verified by DNA sequencing (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher). Plasmid pUCP18-2 was constructed to delete the clpV gene. It was created by inserting the Ptrc::clpV sgRNA and 0.5 kb clpV homologous arms with the pyrF gene into pUCP18, which had been cut with Pst I and Sac I. The Ptrc::clpV sgRNA was amplified and fused with the RBS-free Ptrc promoter amplified from pTrc99A79. The 0.5 kb upstream and downstream of the clpV homologous repairing arms were amplified from the A514 genome using the primers clpV UD-F/clpVUD-R and clpV DD-F/clpV DD-R, respectively, and were subsequently spliced to produce the 1-kb donor by overlap extension PCR. Similarly, additional plasmids were constructed to delete vgrG0132, vgrG0499, vgrG2455, vgrG5774, paaR0130, duf17950131, hcp0137, tolA4149, and tolR4151, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Gene deletion in P. putida A514 was performed based on our previously reported CRISPR/Cas9n-based genome editing method80. Briefly, the Pmin::cas9n and PxylA::gam-bet-exo expression cassettes were integrated to the A514 genome through pUCP18-1 plasmid electroporation. The mutant was verified by DNA sequencing, generating the ARc9n strain. ARc9n, which showed similar DypB3152 protein levels with A3152 (Supplementary Fig. 2), was used as the host strain for subsequent mutant construction.

To delete clpV, the plasmid pUCP18-2 was transformed into ARc9n by electroporation and cultured in liquid LB medium supplemented with 4 mM xylose, 30 μg/mL tetracyclines and 20 μg/mL uracil at 30 °C for 18 h. 100 μL cell culture was transferred to 5 mL fresh 15 mM glucose-M9 medium, supplemented with 4 mM vanillic acid, grown overnight at 30 °C and 200 rpm for plasmid curing, and finally spread on M9 agar plates. Colonies without green fluorescence were randomly picked for PCR screening and DNA sequencing, generating ARc9nΔclpV. It was then transformed with the plasmid pG3152, generating the A∆clpV strain. Additional knockout mutants in this study were constructed based on the same procedures (Supplementary Table 1).

pGTvgrG0132-3152 was constructed for the vgrG0132 complementation assay. The open reading frame (ORF) fragments for the dypB gene (PputA514_3152) and vgrG (PputA514_0132) gene were amplified by PCR with the respective corresponding primers (Supplementary Table 4). Through gene splicing using overlap extension PCR, they were fused with Pmin and Ph5 promoters to generate Pmin-3152 and Ph5-0132 DNA fragments, respectively. The DNA fragments were then digested with Hind Ⅲ/Xba I and Xba I/BamH I, respectively, and ligated into pPROBE-GT (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, pGTvgrG2455-3152 was constructed using the same procedure. For the complementation assay, each complementary plasmid (pGTvgrG0132-3152 and pGTvgrG2455-3152) was introduced into the corresponding mutant by electroporation, followed by selection on LB agar plate supplemented with 30 μg/mL gentamycin.

For fusion expression of dypB with membrane proteins, the open reading frame (ORF) fragment for the dypB gene (PputA514_3152) and the PxylA promoter were amplified by PCR with the corresponding primers (Supplementary Table 4). They were digested and ligated into the plasmid pUCP18-Gm through Xba I and Kpn I, constructing the vector pU3152His. Subsequently, the open reading frame (ORF) fragments for slyB (PputA514_1424), lolB (PputA514_2050), oprF (PputA514_3701), and oprD (PputA514_4168) were amplified by PCR with the respective corresponding primers (Supplementary Table 4), and then fused with the dypB gene using flexible linkers (GGGGS) by overlap extension PCR. These DNA fragments were digested and ligated into the plasmid pUCP18-Gm through Xba I and Kpn I, constructing the vectors pUslyB3152His, pUlolB3152His, pUoprF3152His, and pUoprD3152His, respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

pUFlag3152 was constructed for DypB3152 interactions screening. The DNA fragment of the dypB gene, with an N-terminal Flag-tag, was digested and ligated into the plasmid pU3152His through Xba I and Kpn I, constructing the vector pUFlag3152. The paaR (PputA514_0130) with an N-terminal myc-tag and a Ph3 promoter was fused together by overlap extension PCR. The resulting fragment was then digested and ligated into the plasmid pUFlag3152 through Xho I and Bln I, constructing the vector pUFlag3152-mycpaaR. pUFlag3152-mycvgrG2455, pUFlag3152-mychcp, pUFlag3152-mycdotU and pUFlagvgrG2455-mychcp were individually constructed using the same procedure (Supplementary Table 2).

Extraction of the extracellular, periplasmic, and total cell lysates

Each relevant A514 strain was grown at 30 °C, 150 rpm in LB medium, supplemented with 30 µg/mL gentamicin. When OD600 reached 6.5, 200 mL of cell culture was centrifuged (8000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatants were collected as the extracellular secreted proteins, while the cell pellets were used to extract the periplasmic proteins and total cell lysates. Periplasmic proteins were extracted by osmotic shock9. Briefly, the cell pellets from 100 mL of cell culture were resuspended in 10 mL buffer A (30 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 20% (m/v) sucrose and 0.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)), incubated at room temperature for 10 min, centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and resuspended in ice-cold 5 mM MgSO4 buffer (pH 6.0). After incubation at 4 °C for 20 min, the resuspended solutions were centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected as the periplasmic extracts. Meanwhile, cell pellets from the remaining 100 mL of cell culture were resuspended in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and lysed by sonication (150 W, on 1 s and off 1 s for 5 min)9. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation (13000 g, 5 min, 4 °C) as total cell lysates. Protein concentrations in the total cell lysates, periplasmic fractions, and extracellular fractions were quantified by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo, USA, catalog # 23225), and used to detect the DypB3152 protein level and activity. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

DypB activity assay

The enzymatic activity assays were monitored by a microplate reader (BioTek, Cytation 5, USA) at 25 °C. DypB activity was measured via the oxidation of 5 mM ABTS ((2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), Aladdin, China, catalog # 30931-67-0) in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.5) with 1 mM H2O2, at 420 nm (ε420 = 36,000 M−1 cm−1)10. One unit of DypB activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that oxidized 1 μmol of ABTS per min81. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

Periplasmic proteome and protein co-expression network

The periplasmic proteomic data and protein co-expression network used in this study were from our recent study33 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14545684). Briefly, A3152 and ApGT were cultured in M9 medium supplemented with either 15 mM glucose or 0.3% (w/v) lignin as the sole carbon source. Cell cultures were collected at early- and mid-exponential phases to extract the periplasmic proteins. Proteomic data was generated by the nano system (Thermo Scientific, EASY-nLC1200, USA) coupled with a 1,000,000 FWHM high-resolution Nano Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer system (Thermo Scientific, USA)33. The periplasmic protein co-expression network was constructed based on Spearman’s rank correlations with the threshold of |r | > 0.45, p < 0.05, and displayed by Cytoscape software.

Western blot assay

Samples (80 µg proteins per sample) were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.45 µM, Millipore, USA). The membrane was blocked with QuickBlock Blocking Buffer (Beyotime, China, catalog # P0260) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and incubated with the corresponding primary antibody at 4 °C overnight82. The membrane was washed 4-5 times with TBST buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, pH 7.4) and incubated with secondary antibody (Mouse IgG HRP-conjugated antibody ((ABclonal, China, catalog # AS061) for 1 h64. For the primary antibody, the anti-His antibody (ABclonal, China, catalog # AE003), 1:10,000) was used to detect DypB3152 and OprF with the corresponding C-terminal His-tag, while the anti-DsbA antibody ((Sangon, China, catalog # D190650), 1:2000) was employed to detect the disulfide bond formation protein A (DsbA), as the periplasmic loading control. Meanwhile, the antibody (Boster, China, catalog # BM5368), 1:2000), against RNA polymerase Beta subunit (β-RNAP) was used as the total cell lysates loading control, and the negative control to exclude the cytoplasmic contamination in the periplasm and subsequent OMV samples. Signals were detected by the ECL immunoblotting detection reagent (Bio-Rad, USA, catalog # 1705061) with a Chemiluminescence imager (Tanon 5200Multi, China)60. Proteins were quantified using ImageJ software. The expression of DypB3152 is presented as the normalized ratio of the target protein to RNAP (DypB3152/RNAP)83. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

Co-immunoprecipitation MS analysis (coIP-MS)

The relevant A514 strains with Flag-tag, AFlag and AFlag3152, were grown on LB medium at 37 °C until OD600~6.5. Cells were harvested and washed twice with ice-cold PBS by centrifugation (8000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, 100 mM PMSF). The total cell lysates were extracted via sonication (150 W, on 1 s and off 1 s for 5 min)9. The cell lysate was incubated with 2 μL anti-Flag antibody (ABclonal, China, catalog # AE005) at 4 °C for 16 h, and then was mixed with 20 μL protein A/G MagBeads (Beyotime, China, catalog # P2108) at 4 °C, 50 rpm for 4 h84. The antibody-protein complex was captured by magnetic adsorption and eluted with 20 μL elution buffer.

The eluted proteins obtained by coIP were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE for in-gel digestion. The gel was cut into slices, and the gel fragments digested, with the peptides extracted and lyophilized for further analysis. Peptides were suspended in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The peptide mixture was desalted by C18 ZipTip (Millipore, USA) for proteome analyses by the nano system coupled with a high-resolution mass spectrometer system (Thermo Scientific, USA)33. The raw data were searched against the proteome sequence databases of P. putida A514 Genome Database. The co-immunoprecipitation proteomic datasets are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

The candidates, which were revealed by coIP-MS, were further examined for their interactions with DypB3152 by coIP assay. As described above, the cell lysate was extracted and incubated with the corresponding antibody and protein A/G MagBeads (BeyoMag, China, catalog # P2108). Subsequently, the eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blot assay. Mouse IgG HRP-conjugated antibody (ABclonal, China, catalog #AS061), 1:10,000, was used in an IgG group as a negative control. Anti-Flag ((ABclonal, China, AE005), 1:10000) was used to detect DypB3152 with a C-terminal Flag-tag, while anti-myc ((ABclonal, China, catalog # AE010), 1:10000) was used to detect interacting proteins with a C-terminal myc-tag.

OMV extraction, purification, imaging, and quantification

OMVs were isolated, purified, and quantified based on the reported method59. Briefly, cell cultures at the stationary phase were centrifuged at 6000 g, 20 min, 4 °C. The supernatants were successively filtered through 0.45 and 0.22 µm vacuum filters to thoroughly remove cells. The resulting filtrate was ultracentrifuged at 150,000 g, 1 h, 4 °C using an Optima L-100XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA), and then the pellets that contained the OMVs were suspended in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The OMVs were further purified by the Bacterial MVs Isolation Kit (Rengen Biosciences, China, catalog # BacMV40-10), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified OMVs were stored at -80 °C for later analysis.

The OMV samples were plated on poly-L-lysine–coated glass coverslips and fixed with glutaraldehyde. The samples were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (from 30% (v/v) to 90% (v/v)), freeze-dried, and coated in gold (Au), then mounted. The nanoparticles were visualized and measured with a scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 250 FEG, USA) under 0.45 torr and a beam accelerating voltage of 30 keV.

The total protein concentrations in the OMVs were measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo, USA, catalog # 23225), while the DypB3152 levels in the OMVs were detected by Western blot analysis. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

The extracellular location of DypB3152

To evaluate the extracellular location of DypB3152, the OMVs were treated by proteinase K. Proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL) was incubated with 20 µg of OMVs at 37 °C for 20 min to digest the proteins on the surface of the OMVs. Meanwhile, 1% SDS (v/v) was used to disrupt the intact OMV membrane, followed by proteinase K to digest the total proteins of the OMVs. The treated samples were analyzed by Western blot assay.

Displaying the DypB3152 on the surface of OMVs

DypB3152 was fused with the membrane protein, SlyB, LolB, OprF, and OprD, in the pUCP18-Gm plasmid, generating pUslyB3152His, pUlolB3152His, pUoprF3152His, pUoprD3152His, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). They were transformed into A514 strain and selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 30 μg/mL gentamycin. The generated recombinant strains ASlyB, ALolB, AOprF, and AOprD were grown at 30 °C, 150 rpm in LB medium, supplemented with 30 µg/mL gentamicin. OMVs were extracted from these strains and purified as described above. Western blot assay was performed to identify the DypB3152 protein levels and extracellular location with/without proteinase K treatment.

Optimization of extracellular DypB3152 production by the one variable at a time method (OVAT)

Five parameters were investigated by classical OVAT method to optimize extracellular DypB3152 production in A3152 (Supplementary Table 3). First was the xylose inducer (1–4 mM) of PxylA promoter to initiate DypB3152 transcription. The second parameter was D-cycloserine (100-500 μg/mL) to induce OMVs generation. Additional parameters involved the culture conditions, including culture medium (M9 and LB), pH (5.0–7.0) and culture temperature (20–30 °C). ASlyB∆tolA was cultured by inoculating a single colony into 5 mL LB medium and incubating at 30 °C and 200 rpm. When OD600 reached 6.5, a 1% (v/v) transfer to 100 mL fresh LB medium was performed and cultured at 30 °C, 150 rpm. Cells were collected by centrifugation (8000 g, 4 °C, 15 min) to measure the DypB activity and protein level in OMVs. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

ELISA quantitation of the DypB3152 level in the culture supernatants

The relevant A514 strains were cultured in LB medium under the optimized conditions, as described above. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation (3000 g, 4 °C, 20 min) when OD600 reached 6.5. To measure the DypB3152 protein level in the supernatants, ELISA assays were performed using the His tag ELISA Detection Kit protocol (GenScript, China, catalog # L00436), according to the manufacturer’s protocol85. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

Chemical analyses of treated lignin

The residual lignin concentration in cell culture was measured by Prussian blue assay33,86. Briefly, the pH of the cell culture was adjusted to 12.5 with 2 M NaOH to dissolve the residual lignin. 1.5 mL of sample was mixed with 100 μL 8 mM K3Fe (CN)6 and 100 μL 0.1 M FeCl3 and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The absorbance at 700 nm was photometrically monitored. The experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

The FTIR spectra of each sample were analyzed by an FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet iS50). Each 2 mg of dried lignin sample was pressed against the diamond crystal surface of the spectrometer. Spectra were obtained in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode in the spectral range of 4000 ~ 500 cm−1 by 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The assignment of the major absorption bands to the lignin chemical structure was referenced against the literature47. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical differences between two groups were examined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests, which were performed with Graphpad Prism 9.5. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and p < 0.01 was deemed highly significant, and p < 0.001 was regarded as highly statistically significant. The quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard derivation of three biological replicates. The qualitative data were representative of two biological replicates.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The coIP-MS raw data in this study were deposited in the Mass spectrometry Interactive Virtual Environment (MassIVE) under the accession number MSV000098758. The vector plasmids generated in this study have been deposited with Addgene, accession numbers 245289–245297. The uncropped and unedited blot images are provided in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 9–12). Numerical source data for all figures are provided as Supplementary Data 3. All the data supporting the findings of this study are present in the article, Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data 1-3. All other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Costa, T. R. et al. Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 343–359 (2015).

Russell, A. B., Peterson, S. B. & Mougous, J. D. Type VI secretion system effectors: poisons with a purpose. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 137–148 (2014).

Liu, Z.-H., Li, B.-Z., Yuan, J. S. & Yuan, Y.-J. Creative biological lignin conversion routes toward lignin valorization. Trends Biotechnol. 40, 1550–1566 (2022).

Dong, N. Q. & Lin, H. X. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant-environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 180–209 (2021).

Bugg, T. D. H., Williamson, J. J. & Rashid, G. M. M. Bacterial enzymes for lignin depolymerisation: new biocatalysts for generation of renewable chemicals from biomass. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 55, 26–33 (2020).

Ji, T. et al. Lignin biotransformation: Advances in enzymatic valorization and bioproduction strategies. Ind. Crops Prod. 216, 118759 (2024).

Min, K., Gong, G., Woo, H. M., Kim, Y. & Um, Y. A dye-decolorizing peroxidase from Bacillus subtilis exhibiting substrate-dependent optimum temperature for dyes and β-ether lignin dimer. Sci. Rep. 5, 8245 (2015).

Ahmad, M. et al. Identification of DypB from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 as a lignin peroxidase. Biochemistry 50, 5096–5107 (2011).

Lin, L., Wang, X., Cao, L. H. & Xu, M. Lignin catabolic pathways reveal unique characteristics of dye-decolorizing peroxidases in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 1847–1863 (2019).

Rahmanpour, R. & Bugg, T. D. Characterisation of Dyp-type peroxidases from Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5: Oxidation of Mn(II) and polymeric lignin by Dyp1B. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 574, 93–98 (2015).

Välimets, S. et al. Characterization of Amycolatopsis 75iv2 dye-decolorizing peroxidase on O-glycosides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 90, e00205–e00224 (2024).

Sugano, Y. & Yoshida, T. DyP-Type peroxidases: Recent advances and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5556 (2021).

Jongbloed, J. D. et al. Two minimal Tat translocases in Bacillus. Mol. Microbiol. 54, 1319–1325 (2004).

Sutter, M. et al. Structural basis of enzyme encapsulation into a bacterial nanocompartment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 939–947 (2008).

Contreras, H. et al. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis nanocompartment and its potential cargo proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18279–18289 (2014).

Rahmanpour, R. & Bugg, T. D. Assembly in vitro of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 encapsulin and peroxidase DypB to form a nanocompartment. FEBS J. 280, 2097–2104 (2013).

Brown, M. E., Barros, T. & Chang, M. C. Y. Identification and characterization of a multifunctional dye peroxidase from a lignin-reactive bacterium. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 2074–2081 (2012).

Lin, L. et al. Systems biology-guided biodesign of consolidated lignin conversion. Green. Chem. 18, 5536–5547 (2016).

Lin, L., Lezan, E., Schmidt, A. & Basler, M. Abundance of bacterial Type VI secretion system components measured by targeted proteomics. Nat. Commun. 10, 2584 (2019).

Leiman, P. G. et al. Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 4154–4159 (2009).

Granato, E. T., Smith, W. P. J. & Foster, K. R. Collective protection against the type VI secretion system in bacteria. ISME J. 17, 1052–1062 (2023).

Si, M. et al. Manganese scavenging and oxidative stress response mediated by type VI secretion system in Burkholderia thailandensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, E2233–e2242 (2017).

Song, L. et al. Contact-independent killing mediated by a T6SS effector with intrinsic cell-entry properties. Nat. Commun. 12, 423 (2021).

Unterweger, D., Kostiuk, B. & Pukatzki, S. Adaptor proteins of type VI secretion system effectors. Trends Microbiol 25, 8–10 (2017).

Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, F., Li, D. D. & Li, Y. Z. Identification of type VI secretion system toxic effectors using adaptors as markers. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 3723–3733 (2020).

Toyofuku, M., Nomura, N. & Eberl, L. Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 13–24 (2019).

Guerrero-Mandujano, A., Hernández-Cortez, C., Ibarra, J. A. & Castro-Escarpulli, G. The outer membrane vesicles: Secretion system type zero. Traffic 18, 425–432 (2017).

Pathirana, R. D. & Kaparakis-Liaskos, M. Bacterial membrane vesicles: Biogenesis, immune regulation and pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1518–1524 (2016).

Schwechheimer, C. & Kuehn, M. J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 605–619 (2015).

Salvachúa, D. et al. Outer membrane vesicles catabolize lignin-derived aromatic compounds in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 9302–9310 (2020).

Behrendorff, J., Borràs-Gas, G. & Pribil, M. Synthetic protein scaffolding at biological membranes. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 432–446 (2020).

Alves, N. J. et al. Bacterial nanobioreactors-directing enzyme packaging into bacterial outer membrane vesicles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 24963–24972 (2015).

Liang, C. et al. The Pseudomonas ligninolytic catalytic network reveals the importance of auxiliary enzymes in lignin biocatalysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 122, e2417343122 (2025).

Choi, C.-W. et al. Proteomic characterization of the outer membrane vesicle of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Proteome Res. 13, 4298–4309 (2014).

Albrecht, R. & Zeth, K. Structural basis of outer membrane protein biogenesis in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27792–27803 (2011).

Wu, C. F. et al. Effector loading onto the VgrG carrier activates type VI secretion system assembly. EMBO Rep. 21, e47961 (2020).

Bondage, D. D., Lin, J. S., Ma, L. S., Kuo, C. H. & Lai, E. M. VgrG C terminus confers the type VI effector transport specificity and is required for binding with PAAR and adaptor-effector complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, E3931–E3940 (2016).

Whitney, J. C. et al. An interbacterial NAD(P)+ glycohydrolase toxin requires elongation factor Tu for delivery to target cells. Cell 163, 607–619 (2015).

Silverman, J. M. et al. Haemolysin coregulated protein is an exported receptor and chaperone of type VI secretion substrates. Mol. Cell 51, 584–593 (2013).

Burkinshaw, B. J. et al. A type VI secretion system effector delivery mechanism dependent on PAAR and a chaperone-co-chaperone complex. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 632–640 (2018).

Lee, S. H., Lee, S. Y. & Park, B. C. Cell surface display of lipase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 using OprF as an anchoring motif and its biocatalytic applications. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8581–8586 (2005).

Llamas, M. A., Ramos, J. L. & Rodríguez-Herva, J. J. Mutations in each of the tol genes of Pseudomonas putida reveal that they are critical for maintenance of outer membrane stability. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4764–4772 (2000).

Yun, S. H. et al. Antibiotic treatment modulates protein components of cytotoxic outer membrane vesicles of multidrug-resistant clinical strain, Acinetobacter baumannii DU202. Clin. Proteom. 15, 28 (2018).

Liu, C. F. et al. Succinoylation of sugarcane bagasse under ultrasound irradiation. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 1465–1473 (2008).

Zhang, J. et al. Effect of ammonia fiber expansion combined with NaOH pretreatment on the resource efficiency of herbaceous and woody lignocellulosic biomass. ACS Omega 7, 18761–18769 (2022).

Reyes-Rivera, J. & Terrazas, T. Lignin analysis by HPLC and FTIR. Methods Mol. Biol. 1544, 193–211 (2017).

Miao, G. et al. Deep eutectic solvents for efficient fractionation of lignocellulose to produce uncondensed lignin and high-quality cellulose. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 13, 2197–2209 (2025).

Masi, M. & Wandersman, C. Multiple signals direct the assembly and function of a type 1 secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3861–3869 (2010).

Benabdelhak, H. et al. A specific interaction between the NBD of the ABC-transporter HlyB and a C-terminal fragment of its transport substrate haemolysin A. J. Mol. Biol. 327, 1169–1179 (2003).

Christie, P. J., Whitaker, N. & González-Rivera, C. Mechanism and structure of the bacterial type IV secretion systems. Biochim. Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 1843, 1578–1591 (2014).

Tsirigotaki, A., De Geyter, J., Šoštaric´, N., Economou, A. & Karamanou, S. Protein export through the bacterial Sec pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 21–36 (2017).

Palmer, T. & Berks, B. C. The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 483–496 (2012).

Jana, B., Fridman, C. M., Bosis, E. & Salomon, D. A modular effector with a DNase domain and a marker for T6SS substrates. Nat. Commun. 10, 3595 (2019).

Salomon, D. et al. Marker for type VI secretion system effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 9271–9276 (2014).

Tao, Y. et al. Structure of a eukaryotic SWEET transporter in a homotrimeric complex. Nature 527, 259–263 (2015).

Pukatzki, S., Ma, A. T., Revel, A. T., Sturtevant, D. & Mekalanos, J. J. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 15508–15513 (2007).

Hernandez, R. E., Gallegos-Monterrosa, R. & Coulthurst, S. J. Type VI secretion system effector proteins: Effective weapons for bacterial competitiveness. Cell. Microbiol. 22, e13241 (2020).

Howard, S. A. et al. The breadth and molecular basis of hcp-driven type VI secretion system effector delivery. mBio 12, e0026221 (2021).

Li, C. et al. T6SS secretes an LPS-binding effector to recruit OMVs for exploitative competition and horizontal gene transfer. ISME J. 16, 500–510 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa T6SS-mediated molybdate transport contributes to bacterial competition during anaerobiosis. Cell Rep. 35, 108957 (2021).

Ma, L. S., Hachani, A., Lin, J. S., Filloux, A. & Lai, E. M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens deploys a superfamily of type VI secretion DNase effectors as weapons for interbacterial competition in planta. Cell Host Microbe 16, 94–104 (2014).

Lin, J., Xu, L., Yang, J., Wang, Z. & Shen, X. Beyond dueling: roles of the type VI secretion system in microbiome modulation, pathogenesis and stress resistance. Stress Biol. 1, 11 (2021).

Cianfanelli, F. R., Monlezun, L. & Coulthurst, S. J. Aim, load, fire: the type VI secretion system, a bacterial nanoweapon. Trends Microbiol 24, 51–62 (2016).

Zhu, L. et al. T6SS translocates a micropeptide to suppress STING-mediated innate immunity by sequestering manganese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2103526118 (2021).

Basler, G., Thompson, M., Tullman-Ercek, D. & Keasling, J. A Pseudomonas putida efflux pump acts on short-chain alcohols. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11, 136 (2018).

Angelini, S., Deitermann, S. & Koch, H. G. FtsY, the bacterial signal-recognition particle receptor, interacts functionally and physically with the SecYEG translocon. EMBO Rep. 6, 476–481 (2005).

Zhai, G., Zhang, Z. & Dong, C. Mutagenesis and functional analysis of SotB: A multidrug transporter of the major facilitator superfamily from Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1024639 (2022).

Famelis, N. et al. Architecture of the mycobacterial type VII secretion system. Nature 576, 321–325 (2019).

Maphosa, S., Moleleki, L. N. & Motaung, T. E. Bacterial secretion system functions: evidence of interactions and downstream implications. Microbiology 169, https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001326 (2023).

Vader, P., Mol, E. A., Pasterkamp, G. & Schiffelers, R. M. Extracellular vesicles for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 106, 148–156 (2016).

Toyofuku, M. et al. Membrane vesicle-mediated bacterial communication. ISME J. 11, 1504–1509 (2017).

Biller, S. J. et al. Bacterial vesicles in marine ecosystems. Science 343, 183–186 (2014).

Vidakovics, M. L. et al. B cell activation by outer membrane vesicles-a novel virulence mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000724 (2010).

Chen, D. J. et al. Delivery of foreign antigens by engineered outer membrane vesicle vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 3099–3104 (2010).

Gujrati, V. et al. Bioengineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles as cell-specific drug-delivery vehicles for cancer therapy. ACS Nano 8, 1525–1537 (2014).

Peng, L. H. et al. Engineering bacterial outer membrane vesicles as transdermal nanoplatforms for photo-TRAIL-programmed therapy against melanoma. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2735 (2020).

Konovalova, A. & Silhavy, T. J. Outer membrane lipoprotein biogenesis: Lol is not the end. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0030 (2015).

Sambrook, J., Russell, D., Russell, D. & Russell David, W. Molecular Clonning: A Laboratory Manual. (1989).

Wang, Q., Tappel, R. C., Zhu, C. & Nomura, C. T. Development of a new strategy for production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by recombinant Escherichia coli via inexpensive non-fatty acid feedstocks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 519–527 (2012).

Zhou, Y. et al. Development of a CRISPR/Cas9n-based tool for metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for ferulic acid-to-polyhydroxyalkanoate bioconversion. Commun. Biol. 3, 98 (2020).

Santos, A., Mendes, S., Brissos, V. & Martins, L. O. New dye-decolorizing peroxidases from Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas putida MET94: towards biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 2053–2065 (2014).

Zhao, Z. et al. Frequent pauses in Escherichia coli flagella elongation revealed by single cell real-time fluorescence imaging. Nat. Commun. 9, 1885 (2018).

Zhang, G., Li, X., Wu, L. & Qin, Y.-X. Piezo1 channel activation in response to mechanobiological acoustic radiation force in osteoblastic cells. Bone Res. 9, 16 (2021).

Chen, L. J. et al. Gm364 coordinates MIB2/DLL3/Notch2 to regulate female fertility through AKT activation. Cell Death Differ. 29, 366–380 (2022).

Cao, L. et al. Efficient extracellular laccase secretion via bio-designed secretory apparatuses to enhance bacterial utilization of recalcitrant lignin. Green. Chem. 23, 2079–2094 (2021).

Zhao, C. et al. Synergistic enzymatic and microbial lignin conversion. Green. Chem. 18, 1306–1312 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370115, 32570118) and the National Key Research and Development Project (2023YFC3403500, 2024YFD2401701). This study contributes to the science plan of the Ocean Negative Carbon Emissions Program. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We would like to thank Jing Zhu, Jingyao Qu, and Zhifeng Li, from the Core Facilities for Life and Environmental Sciences, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology of Shandong University for assistance in Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (EASY-nLC & Nano-Tribrid MS Orbitrap Fusion Lumos) and data processing. We appreciate the FTIR measurements assisted by Zhen Yan from the Analytical Testing Center, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Shandong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. and C.L. conceived and designed the study. C.L., X.W. and W.Z. performed the experiments. L.L. and C.L. analyzed the data. L.L. and C.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Haichun Gao and Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, C., Lin, L., Wang, X. et al. The secretion of Pseudomonas unconventional peroxidase facilitates extracellular carbon acquisition from heterogeneous lignin. Commun Biol 8, 1318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08749-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08749-7