Abstract

The Kv11.1 potassium channels and the transcription factor c-Myc both play fundamental roles in controlling cellular homeostasis. Cancers take advantage of dysregulated c-Myc and Kv11.1, however, little is known about the possible link between these proteins. In this work we found that an inverse relationship between c-MYC and Kv11.1 exists in some lung adenocarcinoma. Importantly, patients expressing an elevated level of the Kv11.1 channel present a better overall survival when compared with patients with low expression. Therefore, we evaluated the hypothesis that pharmacologic activation of the Kv11.1 channel in lung cancer may impair tumor growth. We discovered that Kv11.1 activation inhibits lung cancer growth by inducing a senescent phenotype. Moreover, we found that pharmaceutical Kv11.1 opening produced a rapid proteasomal degradation of c-Myc and that this could be antagonized by the OTUD6B deubiquitinase. We concluded that use of Kv11.1 agonists should be considered as anticancer pharmacological strategy against lung adenocarcinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer related deaths worldwide. Adenocarcinoma of the lung (LuAd) is the most common form of lung cancer making up approximately 40–50% of overall lung cancer incidence1. LuAd is most often diagnosed in advanced stage, meaning that it cannot be cured by surgical interventions alone. Chemotherapy is used to treat advanced malignancy. Targeted therapeutics are available to treat a subset of LuAd that are caused by activating mutations in certain kinases, but the remaining advanced stage patients have few options other than chemotherapy, and more recently immunotherapy. The 5-year survival rate for advanced LuAd is a dismal 9%2. The pathogenesis of LuAd is determined by several factors including an array of different driver mutations (e.g., Kirsten rat sarcoma virus; KRASG12V). However, the proto-oncogene c-Myc aberrant expression is demonstrably detected in more than 85% cases of lung cancers, including LuAd3,4. Aside from direct MYC gene amplification (about 20% of cases) c-Myc protein is prevalently upregulated at the post-translational level. Amplification and/or stabilization of c-Myc is an independent factor for poor prognosis5. A well-known mechanism for c-Myc stabilization (for instance, in LuAd cases driven by Ras mutations) is mediated by ERK-dependent phosphorylation of Thr-62 on c-Myc6,7. Therefore, c-Myc activation prevents cells exiting the cell cycle by activating and suppressing transcription of growth-related genes (e.g., p21Cip1, DUSP1)8,9,10. However, in normal conditions, c-Myc is a very short-lived protein. Growth-inhibitory pathways can reduce c-Myc protein level by altering its protein level via activation of proteasomal degradation. The canonical c-Myc degradation signaling requires ubiquitination by the F-Box and WD Repeat Domain Containing 7 (FBXW7) E3 ubiquitin ligases upon phosphorylation of Thr-5811. In contrast, several deubiquitinase, such as ubiquitin-specific proteases (for instance, USP28) can antagonize c-Myc ubiquitination12. Recent studies on c-Myc stability revealed that the isoform 2 of a member of the ovarian tumor domain (OTU)-containing family of deubiquitinating enzymes, OTUD6B-2 plays a major role in controlling non-small cell lung cancer proliferation. Intriguingly, OTUD6B-2 appeared to control c-Myc protein expression independently of ERK activation13.

In physiological conditions, the KCNH2 gene encodes for the Kv11.1 potassium channel which is normally expressed in colon, cardiac14,15,16 or neural crest cells17 where it plays a fundamental role in controlling cellular electrical changes that underline contraction as well as differentiation. However, Kv11.1 expression has also been observed in cancers of different histogenesis where it can contribute to both oncogenic and onco-suppressive processes roles depending on cancer context18. Likewise, many cancers rely on c-Myc overactivation to achieve a so-called “MYC addiction”19. However, the role of Kv11.1 and the therapeutic benefits of targeting this protein in lung cancer have not been sufficiently explored. In this work, we demonstrate that pharmacological activation of Kv11.1 potassium channel produces a growth arrest in several models of LuAd. This growth arrest is associated with proteasomal degradation of c-Myc, which is antagonized the OTUD6B deubiquitinase.

Results

The Kv11.1 potassium channel is a positive prognostic factor in LuAd

We conducted an in silico meta-analysis to investigate the potential role of the Kv11.1 potassium channel in lung cancer using TNMplot (tnmplot.com). Differential gene expression analysis revealed that KCNH2 gene (encoding for Kv11.1 channel protein) is downregulated in both lung adenocarcinoma (LuAd) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) when compared with samples from non-cancerous patients and pediatric tissues (Fig. 1A,–C, E,–G; Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 5). This study suggests that downregulation of Kv11.1 expression could provide an advantage to tumor growth.

A Violin plots, and B bar chart of KCNH2 gene expression in LuAd comparing paired tumor and normal gene array (GEO database). The bars represent the proportions of tumor samples exhibiting higher expression of the selected gene compared to noncancerous samples at each of the quantile cut-off values (min=minimum, Q1=1st quartile, Med=median, Q3=3rd quartile, Max=maximum). Specificity was calculated by dividing the number of tumor samples by the sum of tumor and normal samples below each given cut-off. In cases where the fold change was greater than 1, “over” was used instead of “below”. C Survival analysis (Kaplan-Mayer plot) and D progression free survival for LuAd patients expressing high KCNH2 level (red) vs low level (black). E Violin plots and F bar chart of KCNH2 gene expression in LuAd comparing paired tumor and normal gene array (GEO database). G Kaplan-Mayer plot and H progression free survival for SSC patients expressing high KCNH2 level (red) vs low level (black).

Furthermore, we analyzed the impact of KCNH2 expression on overall survival (OS) and First Progression (FP) of LuAd or SSC in patients who smoked (Fig. 1C, D, G, H). Interestingly, we found that OS and FP of LuAd smoker patients in the high-expression cohort was significantly better when compared with low expression (Fig. 1C, D). In contrast, no significant change was observed in OS between high vs low expression in the SSC cohorts’ patients (Fig. 1G, H). Also, a significant better OS was also observed in female patients with high KCNH2 expression level and have received surgery (Supplementary Fig. 1B) or chemotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 1C) when compared with females that did not receive these treatments (Supplementary Fig. 1C). In contrast, females that have received radiotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 1E) present no difference in OS. These data show that KCNH2 can be considered as a favorable prognostic marker in LuAd, and that high activity of Kv11.1 channel can interfere with tumor growth.

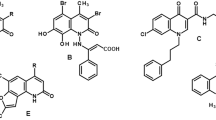

Pharmacological activation of Kv11.1 arrests the cell cycle of LuAd without producing cell death

To further test the hypothesis that high Kv11.1 activity can suppress lung cancer growth we assessed the effects of pharmacological activation of Kv11.1 in a panel of cancer cells Kv11.1 positive human derived lung cancer cell lines including A549, H1437, H1650, and large cell lung carcinoma H1299 (Fig. 2A, B). Cell viability assay revealed that exposing these cells to the Kv11.1 channel activator NS1643 for different time points produced a significant decrease in proliferation rate (Supplementary Fig. 2A). We performed a cell cycle analysis via flow cytometry by propidium iodide staining in Kv11.1 positive LuAd cell lines treated with the Kv11.1 channel activator NS1643 for 24 or 48 h (Fig. 2C, D). We found that 48 h treatment produced a statistically significant accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 cell cycle phase which was associated with a reduction of cells in S phase and G2/M phase of the cell cycle. In addition, we investigated the effects of NS1643 on important proteins controlling cancer cell proliferation such as the oncogene c-Myc and the oncosuppressor p21. Western blot analysis revealed that NS1643 treatment produces downregulation of c-Myc and an up regulation of the tumor suppressor p21 protein levels (Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, these revealed that pharmacological activation of Kv11.1 channel produces strongly inhibits proliferation of lung cancer cells.

A Western blot showing expression of the Kv11.1 ion channel protein in human derived A549, H1299, H1437, H1650 lung cancer cell lines. B Cell imaging of H1299 or H1650 lung cancer cell lines stained with FITC-Kv11.1 (Alomone; APC-109-F) vs unstained (Control). Images were obtained via wide-field fluorescent imaging with a 20× objective lens (blue = DAPI nuclear counterstain, green = GFP-tubulin). C Cell cycle analysis (flow cytometry) of A549 or D) H1299 lung cancer cell line treated with NS1643 (50 mM; 24–48 h). Numeric breakdown (data for NS1643 refers to 48 h of treatment); A459: control G0/G1 phase = 56.66% ± 0.66%; NS1643 G0/G1 phase = 70.53% ± 0.90%; control S phase = 20.0% ± 1.15%; NS1643 S phase = 10.13% ± 0.59%; control G2/M phase = 20.66% ± 0.66%; NS1643 G2/M phase =16.0% ± 0.57%. H1299: control G0/G1 phase = 56.93% ± 0.7%; NS1643 G0/G1 phase = 64.83% ± 0.44%; control S phase = 10.1% ± 1.45%; NS1643 S phase = 9.86% ± 0.52%; control G2/M phase = 26.56% ± 0.58%; NS1643 G2/M phase = 24.0% ± 0.72%. A smaller concentration of NS1643 produced the same effect but for a longer time. E Western blot showing the effects of NS1643 on c-Myc and P21 protein level (50 mM; 24 hr). Bar graph showing quantification of E). * Statistically significant (P < 0.05).

To gain insight on the mechanism linking NS1643 to arrest of cell proliferation, we monitored changes of apoptotic markers via immunofluorescence flow cytometry (Annexin V). We found that NS1643 did not induce a significant alteration of the cell death marker (Fig. 3).

Inverse correlation between KCNH2 and c-MYC

The central oncogene c-Myc is a major factor controlling cancer cell growth and proliferation20. Remarkably, it has been shown that c-Myc can repress p21 expression while we found that treatment of lung cancer cells with Kv11.1 agonists suppressed c-Myc and upregulated p21 expression level (Fig. 2E. This led us to investigate the potential co-relation between KCNH2 (Kv11.1) and MYC (c-Myc) gene expression in lung cancer. We found that LuAd tumors present high Kv11.1 and low c-Myc expression (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, survival analysis proved that patients with elevated level of KCNH2 and MYC present a better overall survival when compared with patients with low level of KCNH2 and high MYC (Fig. 4B–D). However, no significant co-relation between KCNH2 and c-MYC was observed in patients with SSC tumors (Fig. 4E). In addition, the high level of KCNH2 did not reveal significant benefit in SSC patients (Fig. 4F,–H). These data suggest that high expression level of the KCNH2 potassium channel counteracts the pro-oncogenic activity of c-MYC in LuAd.

A KCNH2 mRNA expression (RNA sequence V2 RSEM in log2) showed negative co-relation with MYC. B Survival analysis (cBioPortal) for LuAd patients expressing high KCNH2 level (orange) vs low level (green), C high KCNH2 (orange) and high MYC (purple) or D comparison between high KCNH2, Low KCNH2 and MYC. E–H Survival analysis (cBioPortal) for SSC patients expressing high KCNH2 level (orange) vs low level (green), high KCNH2 (orange) and high MYC (purple) or comparison between high KCNH2, Low KCNH2 and MYC.

Kv11.1 activation rapidly downregulates c-MYC

To test the hypothesis that Kv11.1 activation downregulates c-Myc, we monitored the effect of NS1643 on c-Myc protein level. As c-Myc is known to be a short-lived protein, we treated LuAd cancer cells with NS1643 for different time points ranging from 30 min to 120 min (Fig. 5A, B). Remarkably, Kv11.1 activation produced a significant decrease of c-Myc protein level at the earliest time point of 30 min in all cell lines showing that Kv11.1 activation rapidly affects c-Myc protein expression. These effects were abolished in cells where the expression of Kv11.1 was artificially depleted using RNA interference. In these conditions neither NS1643 nor another chemically distinct Kv11.1 activator PD115087 were able to affect c-Myc protein levels or cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B, C). This supports the hypothesis that the effects of Kv11.1 agonists are specific to the Kv11.1 activity rather than through unspecific targets. Furthermore, the Kv11.1-dependent downregulation of c-Myc is associated with an increased transcription of genes that are known to be suppressed by c-Myc21, including fatty acid synthase (FASN), dual-specific phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-inducible 45 (GADD45) (Fig. 5C, Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data support a model that suggests that pharmacologic activation of Kv11.1 can promote growth arrest in LuAd by a rapid downregulation of c-Myc.

A Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 treatment (50 mM; 0-30-60-120 min) on c-Myc protein level in A549, H1299 or B H1437, H1650 lung cancer cell lines. Bar graph showing quantification of the events in (A, B). C Bar graph shows mRNA expression for FASN, DUSP1, and GaDD45A in A549 or D H1299 lung cancer cell lines after 24 h NS1643 treatment.

Kv11.1 agonist arrests LuAd tumor growth

To assess the potential clinical benefits of pharmacological stimulation of Kv11.1 activity we assessed the efficacy of the Kv11.1 activator NS1643 on LuAd tumor growth. We used the well-defined Lewis lung carcinoma mouse (LLC) syngeneic model which expresses Kv11.1 channel, bears oncogenic KRASG12V mutation22,23. In this model, tumors grow in a syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse; these tumors are representative of human adenocarcinoma lung cancer. We observed reduced cellular proliferation in the LLC cell model when they were exposed to a concentration of NS1643 of 50 mM (Fig. 6A) differently to what was observed in the human model. Also, mice harboring LLC-derived tumors and treated with NS1643 (6 mg/kg) presented significantly reduced tumor volumes in comparison to the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 6B, C) as early as 6 days following injection (day 12). At completion of the study, we observed that the mean tumor weight of control mice was 1.2 ± 0.03 gr (Fig. 6D; Mean ± SEM) while that of the NS1643-treated group was significantly lower at 0.49 ± 0.05 gr (Mean ± SEM). The inhibitory effect of NS1643 on LuAd growth was confirmed in a parallel study performed with xenograft model of nude mice injected with the human-derived LuAd cancer cells H1299 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Remarkably, immunohistochemistry analysis of tumors in mice treated with NS1643 presented a significant downregulation of both proliferation markers Ki67 and c-Myc (Fig. 6E, F).

A Proliferation assay performed with Lewis lung carcinoma cells exposed to NS1643 (25–50 mM/24 h). Inset Western blot indicates expression of the Kv11.1 channel. B Effects of NS1643 injection (6 mg/Kg; 3 days interval of intraperitoneal injection) on LLC tumor growth in LLC syngeneic model. C, D Size and weight comparison of LLC tumors dissected from control (DMSO) or test (NS1643) mice. E Representative images of IHC staining of Ki-67 and F c-Myc (A) in control vs NS1643 treated LLC tumor model. Scale bar = 50 µm, magnification ×400. *, ** statistically significant (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, respectively).

NS1643 activates c-Myc proteasomal degradation

To evaluate the hypothesis that Kv11.1 activation promotes c-Myc degradation, we performed a protein decay assay with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 7A, B). We observed a reduction in c-Myc protein density in cells treated with the combination of cycloheximide and NS1643 compared to NS1643 or CHX alone (Fig. 7A, B). In contrast, treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 completely rescued the effect of NS1643 on c-Myc (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, we observed a statistically significant reduction of the c-Myc protein stability markers serine 62 phosphorylation on c-Myc in NS1643-treated cells (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. 4C). These data suggest Kv11.1 activation promotes a proteasomal degradation of c-Myc.

A Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 alone, cycloheximide alone (CHX) or NS1643 and CHX at different time points (0, 30, 60, 90 min) on c-Myc protein density in A549 lung cancer cells. Intensities were normalized for the loading control histone H3. B Quantification of the events in (A) for the 0, 30, 60 min time points. C Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 (50 mM; 24 h) alone or with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in A549 cells. The bar graph indicates quantification of (C). D Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 (50 mM; 24 h) on phosphorylation of Serine 62 or Threonine 58 of c-Myc in A549 cell line. E Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 (50 mM; 24 h) on the doxycycline-induced c-MycT58A in A549 cells. F Western blot showing the effect of NS1643 (50 mM; 24 h) on c-Myc in A549 cells transiently transfected with either OTUD6B1 or OTUD6B2 in pCDNA3. Similar results were obtained in H1299. *, **statistically significant (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, respectively).

Kv11.1-dependent c-Myc degradation is antagonized by OTUD6B2

To gain insight into the mechanism of Kv11.1-dependent c-Myc proteasomal degradation we tested the hypothesis that NS1643 can activate the well-known Fbxw7-mediated destabilization of the c-Myc protein. More specifically, the SCFFbxw7 E3 ligase complex is recruited to c-Myc upon phosphorylation of the c-Myc threonine 58 (T58)24. Our data showed that phosphorylation of T58 of c-Myc is not upregulated upon NS1643 treatment; rather, we observed a statistically significant decrease in phosphorylation of this site (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. 5). This led us to suspect that Kv11.1 activation promotes c-Myc degradation independently of the phosphodegron comprising T58 and S62. To confirm this, we used a mutant c-Myc harboring a threonine to alanine substitution at position 58. We first transduced cells with a lentiviral vector encoding for a doxycycline-inducible, proteasomal-resistant c-Myc (Fig. 7E; cMyc-T58A; Supplementary Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. 5). This construct includes a mutation on Thr58 with alanine and protects this mutant from rapid proteasomal degradation and renders this protein less dependent upon KRAS stimulation25. Then, we exposed these cells to NS1643 and monitored c-Myc protein expression. Remarkably, although the c-Myc-T58A construct was produced in transfected cells as proved by the increased c-Myc density when compared with naïve cells, we found that NS1643 was still capable of reducing c-Myc protein expression significantly. These data suggest that Kv11.1 activation promotes proteasomal-dependent c-Myc degradation via a mechanism independent from the phosphodegron regulated by ERKs activity.

The Ovarian tumor domain-containing protein 6B (OTUD6B), presents two splice variants named OTUD6B-1 and OTUD6B-2. OTUD6B-2 stimulates the accumulation of c-Myc in a proteasome-dependent fashion, while OTUD6B-1 does not affect c-Myc expression13. These effects were observed without altering ERKs activity in NSCLC cells13. For this reason, we tested the hypothesis that Kv11.1 activation can affect OTUD6B2-dependent degradation of c-Myc. Therefore, we first transfected cells with constructs encoding for OTUD6B-1, OTUD6B-2, or control plasmid. Then, we monitored c-Myc protein density in these cells before and after being exposed to NS1643 (Fig. 7F). We found that treatment with NS1643 produced a reduction of both OTUD6B-1 and OTUD6B-2. However, re-expression of the OTUD6B-2 isoform to near physiologic levels but not the re-expression of OTUD6B-1, prevented Kv11.1 activation-dependent loss of c-Myc. These data indicate that the OTUD6B-2 deubiquitinase antagonizes the Kv11.1 activation-dependent downregulation of c-Myc in LuAd.

Discussion

Worldwide LC, with LuAd being the most diagnosed, is the second most common cause of death. It is widely accepted that lung cancer is a group of clinical entities that share cellular and molecular origins but that have various clinical behaviors which result in different prognosis. Thus, analyzing the prognosis for an individual patient with lung cancer is difficult. Earlier studies have shown that smoking, gender, age and TNM staging of lung cancer are the main prognostic basis for lung cancer. Knowledge of these prognostic factors allows us to choose a personalized treatment for an individual patient.

Although in the past decades the development of targeted drugs for LC, alongside the introduction of immune checkpoints inhibitors, has changed the natural history of LC, the 5-year survival of advanced LuAd is still 9% only. Several factor can contribute to the occurring inefficacy of treatments which include insurgence or resistance to therapy and/or lack of novel targets. In this work we show that lung cancer tends to downregulate expression Kv11.1 potassium ion channel and that this event associates with a worse overall survival in LuAd patients. Specifically, survival analysis of LuAd patients that were smokers, female, received surgery or chemotherapy and expressed high level of the KCNH2 gene (encoding for Kv11.1 channel) presented a significantly better prognosis when compared with patients with low expression. These results suggest that KCNH2 expression level could be used to strengthen diagnostic and prognostic investigations for an unmet and large subpopulation of lung cancer patients.

Our in-silico investigation prompted to test whether high activity of Kv11.1 could affect lung cancer growth. Therefore, we tested the effects of Kv11.1 agonist NS1643 in two distinct lung cancer mice models: the LLC and H1299 xenograft. The LLC-derived tumors are characterized by expression of KRASG12C mutation which is the most common genetic mutation in North American lung adenocarcinoma patients. Recently, some therapeutic success has been achieved by using direct inhibitors of the KRASG12C protein which show clinical response rates of 37–43%. Unfortunately, these agents fail to generate lasting therapeutic responses with median progression-free survival of ~6.5 months. Also, the H1299 cells that we used in our xenograft model lack expression of the oncosuppressor p53. Our data show that pharmacological activation of the Kv11.1 produced a cytostatic effect in both in vivo models of lung cancer. This event was characterized by an inhibition of cell proliferation, arrests of the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase but without producing cell death. We have observed that these events also occurred when we experimented the effects of Kv11.1 activation in different cancer settings, such as breast cancers (e.g., estrogen-receptor positive or negative) or melanoma26,27,28 and, in all cases, it underlined the activation of a senescent phenotype. These data suggests that activation of Kv11.1 presents similar anticancer effects independently of the cancer histology but, KCNH2 expression level in LuAd could be considered as a potential discriminatory factor for treatment efficacy. However, further testing this hypothesis would require experimentation that is not the focus of the current investigation.

Several studies have intriguingly linked Kv11.1 expression to the development of cancer, yet the exact biochemical pathway connecting these phenomena remains unclear. One potential mechanism involves the interaction between Kv11.1 and β-integrin, known to facilitate oncogenic signaling29. Notably, this interaction seems to occur independently of Kv11.1’s ionic conductivity, as β-integrin recruits the Kv11.1 channel while it remains closed30. Our experiments reveal that sustained activation of Kv11.1 channel currents triggers an anti-proliferative signaling cascade in LuAd and other cancer types. It’s plausible that continuous channel activation (opening) with NS1643 could disrupt its association with β-integrin, thereby suppressing oncogenic signaling. Furthermore, like the anticancer effects of Kv11.1 activation, blocking the channel inhibits tumor growth31. This underscores the critical role of maintaining proper ionic gradients, as either hyper- or hypo-conductivity of Kv11.1 channels halts cancer cell proliferation. However, Kv11.1 blockade may lead to cardiac dysfunction and an increased risk of ventricular fibrillation, discouraging its use in cancer treatment. Nevertheless, our prior evidence suggests that acute or chronic treatment with Kv11.1 activators such as NS1643, rather than blockers, does not significantly impact heart or organ function26,32. This implies that Kv11.1 agonists could be safely employed in cancer therapy. We propose that pharmacological activation of Kv11.1 channels could be an effective and safe strategy for treating challenging cancers such as LuAd.

Our investigation of the mechanism linking Kv11.1 to inhibition of tumor growth revealed that activation of Kv11.1 produced a downregulation of the central oncogene c-Myc. C-Myc is a well-known central oncogene that controls a variety of hallmarks of cancer, including proliferation, metabolism, survival. In addition, c-Myc can prevent cellular senescence by bypassing or repressing cell cycle check points such as p2133. Therefore, suppressing c-Myc is considered as a promising cancer treatment strategy. Nevertheless, direct targeting c-Myc has proven to be a major challenge for several decades. In the current work we discovered that pharmacological stimulation of the Kv11.1 potassium channel activates a proteasomal degradation of c-Myc which support the anticancer effects of Kv11.1 agonists and the occurring of the senescent phenotype in lung cancer cell lines as characterized by increased p21 protein level. Our mechanistic discoveries propose that activation of the Kv11.1 channel resulting in rapid downregulation of c-Myc can be antagonized by the deubiquitinase OTUD6B. This event can be rescued by re-expression of OTUD6B-2 at near physiological level. OTUD6B-2 appears to operate outside the known phosphodegron, including T58 and S62. We are currently investigating the E3 ligase that OTUD6B-2 antagonizes, and this will be the subject of an independent study. We propose that the Kv11.1-Low/OTUD6B2-high may serve as an independent prognostic marker for poor prognosis in LuAd which might be considered for treatment strategy using Kv11.1 activator.

Materials and methods

Prognostic analysis

The Kaplan–Meier Plotter database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) is a database that evaluates the prognostic value of a specific gene by analyzing data from the GEO and TCGA databases. According to the median KCNH2 or MYC expression levels, patients were divided into high and low expression groups; the difference in survival was compared using Logrank test between the two groups; and a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was drawn.

Cell lines and culture

A549, H1299, H1437 and H1650 cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (4.5 g/L glucose) (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini Bio, West Sacramento, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin (10,000 units/mL)/streptomycin (10,000 µg/mL) (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

In vivo experiments

C57Bl6 mice. We implanted with 250,000 Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells by subcutaneous injection into the shaved right flank of adult male immune competent C57Bl6 mouse model. NS1643 was first diluted into DMSO at 2.3 M and immediately before treatment the drug was prepared by mixing with water at a 1:4 ratio of DMSO to water. Animals were randomized when tumors reached 5 mm2. Mice received intraperitoneal injections of 6 mg/kg drug (treatment group) or DMSO saline mix (control) three times a week and tumors were measured by a blinded observer.

The methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by the Medical University of South Carolina IACUC committee with the protocol #: IACUC-2022-01505

Xenograft

We injected subcutaneously 5 million cells in 100 µl of sterile saline in the right flank of ten mice. Three days after injection of cells, we treated one group of 5 mice with 10 mg/kg of NS1643 subcutaneously (Monday, Wednesday, Friday), while the other group of 5 mice received only the DMSO vehicle. Mice were monitored for four weeks after injection of cells. After the monitoring period, mice were euthanized using CO2 inhalation; tumor masses, if present, were excised and measured with a caliper. Tumor volumes were calculated using the modified ellipsoidal formula: V = ½ (Length × Width2.

Reagents, antibodies and siRNA

All antibodies were bought from Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). C-Myc Antibody for Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was bought from Abcam (ab32072, 1:1000) (Waltham, MA, USA). P21 (cell siganling, 2947S, 1:1000) The anti-KCNH2 antibody was bought from Alomone Lab (APC-062, 1:1000) (Israel). Phospho C-Myc (S62) and (T58) were purchased fromm cell signaling (13748S, 13749S, 1:1000). NS1643 was bought from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel). PD118057 (cat#313674-97-4) Doxycycline(cat# D9891) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Cycloheximide was bought from Selleckchem (cat#.S7418) (Houston, TX, USA). MG132 was bought from Enzo Life Sciences (cas# 133407-82-6, Farmingdale, NY, USA). Rneasy FFPE Kit was bought from Qiagen (Cat. 73504). Si-RNA targeting Kv11.1 and was bought from Origene (Cat. SR302526). The transfection reagent was bought from Origene (Cat. TT320001).

Lentiviral vectors and transfections

We used the backbone pCW57.1, which was a gift from David Root (Addgene plasmid # 41393; http://n2t.net/addgene:41393; RRID:Addgene_41393). MYC T58A (human) was PCR-amplified from MSCV Myc T58A puro, which was a gift from Scott Lowe (Addgene plasmid # 18773; http://n2t.net/addgene:18773; RRID:Addgene_18773). We used primers 5’-GGGGCTAGCATGTCTAGACCCCTCAACG-3’ and 5’-GGGACCGGTTTACGCACAAGAGTTCCGT-3’. The polymerase was the Phusion High-Fidelity PCR (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The PCR product was gel-purified, restriction digested and inserted into the NheI and AgeI restriction sites of pCW57.1. Lentiviral packaging was performed in HEK293FT cells by co-transfecting 10 μg of the lentiviral genome alongside equal amounts of pSPAX2 and pCMV-VSVG on 30 × 106 HEK 293FT cells. The transfection agent was PEI Prime™ linear polyethylenimine (SigmaAldrich) used at a 2:1 stoichiometry as compared to total amount of plasmid DNA. 54 h after transfection, the supernatant of HEK293FT cells was collected, filtered through a 0.45 μm polyethersulfone filtration unit and applied to target cells. Twenty five hours after infection, cells were selected with 5 μg/ml puromycin in complete growth medium for 1 week.

Tranfection on cell lines was performed using 1 μg of purified plasmid DNA per 106 cells (70–80% confluent; 5 × 106 total) resuspended in 0.8 ml of OptiMEM using a BioRad Gene Pulser Xcell electroporator. After electroporation, cells were washed in complete medium once and plated. OTUD6B-1 and OTUD6B-2 in pCDNA3 were previously described13.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR Analysis

Total tumor tissue RNA from paraffin-embedded tumor tissues was purified using Qiagen Rneasy FFPE Kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Total RNAs from cancer cells were extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies, NY, USA). For cells harvested with Trizol, 1 mL Trizol was added to each plate and the suspension transferred to a fresh tube. For Trizol extraction, 200 µL chloroform was added to the tube and shaken for 15 s. Samples were incubated at room temperature (RT) for 2–3 min and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper clear phase was transferred to a fresh tube. Prior to precipitating the RNA with isopropanol, 2 µL glycogen as a carrier was added to the clear phase. Then after addition of 500 µL isopropanol, samples were incubated for 10 min at RT and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL of 75% cold ethanol, mixed, and centrifuged at 7600 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Then the RNA pellet was resuspended in 100 µL of RNase-free water. For the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA), 1 μg of RNA was used according to the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Relative expression of each gene was normalized to Beta-actin (ACTB).

Primers:

PRIMERS FOR ACTB are missing.

FASN For: 5′-TACGACTACGGCCCTCATTT-3′

FASN Rev: 5′-CCATGAAGCTCACCCAGTTATC-3′

GADD45A For: 5′-AGGACGACGACAGAGATG-3′

GADD45A Rev: 5′-CTGACGCGCAGGATGTT-3′

DUSP1 For: 5’-GTGGAAATCCTGCCCTTTCT-3’

DUSP1 Rev: 5’-GGATGCTCTTGTACTGGTAGTG-3’

ACTB For: 5’-CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC-3’

ACTB Rev: 5’-AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT-3’

Protein extraction and western blotting

After RNA extraction from Trizol, 300 µL of 95% ethanol was added to the phenol–ethanol phase, mixed and let the mixture stand at RT for 2–3 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The upper phase was removed, 750 µL of isopropanol was added to 400 µL of the lower phase, and the samples were incubated 10 min at RT. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were washed three times with cold acetone. The protein pellets were dissolved in 75 µL water and mixed with 25 µL Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol. Finally, samples were heated for 10 min at 95 °C and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min. The same amount of protein samples was loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were incubated for 1 h in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS) having 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and then overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Membranes were washed with TBST three times and then incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at RT, followed by washing with TBST. Proteins were visualized by the Imager (ChemiDoc MP Imaging System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Histone H3 was evaluated for normalization of protein expression.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was assessed by using a BD Pharmingen FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I. Briefly, cells were harvested and washed with PBS twice. The pellets were resuspended in 1× Binding Buffer and incubated for 15 min at room temperature with 3 µL of FITC Annexin V and 3 µL of Propidium Iodide in the dark. Then, 400 µL of 1× Binding Buffer was added to each tube prior to analysis. Samples were analyzed with a flow cytometer (LSR Fortessa with HTS, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA). The gating strategy included initial selection of intact cells based on forward scatter area (FSC-A) versus side scatter area (SSC-A) to exclude debris. Doublets were excluded using FSC-A versus FSC-H gating. Apoptotic populations were determined using bivariate plots of Annexin V (FITC channel) versus PI (PE channel).

Cell cycle assay

Cells were harvested and washed twice with cold PBS. The pellets were resuspended in PBS with 1% formaldehyde and 0.2% Trition X-100. Then, the cells were incubated in PBS with DAPI for 2 h. The samples were analyzed with a flow cytometer (LSR Fortessa with HTS, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA). Gating was performed to exclude debris (FSC-A vs SSC-A) and doublets (FSC-A vs FSC-H). DNA content histograms of DAPI intensity. Cell populations were assigned to the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases based on DAPI intensity.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The sections were run on the Leica Bond III modified Protocol F to include extra washes between steps. C-Myc antigen retrieval was at a low pH for 30 min and Ki-67 was high pH for 30 min. Primary incubation was 10 min. After washing, slides were incubated with secondary antibody. Microscopy was performed using an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan). For the evaluation of immunohistochemistry slides (histoscore) using ImageJ, positive cells were counted in each image per slide, with two different slides per mouse.

H1299 and H1650 cells were fixed in acetone kept at −20 °C for 10’, washed in PBS, blocked in PBS containing 1% human serum, exposed to antibodies in PBS plus serum at a dilution 1:50. After incubation, cells were washed five times in an excess of PBS, mounted using ProLong™ Glass Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen) and analyzed under a fluorescent microscope. The control antibody was Rabbit anti-Mouse IgG Recombinant Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean values ± standard error, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (t-test). Representative experiments were replicated at least three times. Statistical analysis for tumor growth was performed with the Mann-Whitney test.

Ethical approval

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request to the corresponding author: Saverio Gentile. Source data can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

References

Travis, W. D. et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 244–285 (2011).

Global Burden of Disease Cancer C., Fitzmaurice, C. et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1749–1768 (2019).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511, 543–550 (2014).

Ellrott, K. et al. Scalable open science approach for mutation calling of tumor exomes using multiple genomic pipelines. Cell Syst. 6, 271–281. e7 (2018).

Lee, K. S. et al. c-MYC copy-number gain is an independent prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One 10, e0139727 (2015).

Henriksson, M. & Luscher, B. Proteins of the Myc network: essential regulators of cell growth and differentiation. Adv. Cancer Res. 68, 109–182 (1996).

Marcu, K. B., Bossone, S. A. & Patel, A. J. myc function and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61, 809–860 (1992).

Herkert, B. & Eilers, M. Transcriptional repression: the dark side of myc. Genes Cancer 1, 580–586 (2010).

Walz, S. et al. Activation and repression by oncogenic MYC shape tumour-specific gene expression profiles. Nature 511, 483–487 (2014).

Watson, J. D., Oster, S. K., Shago, M., Khosravi, F. & Penn, L. Z. Identifying genes regulated in a Myc-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36921–36930 (2002).

Farrell A. S., Sears R. C. MYC degradation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a014365 (2014).

Sun, X. X., Sears, R. C. & Dai, M. S. Deubiquitinating c-Myc: USP36 steps up in the nucleolus. Cell Cycle 14, 3786–3793 (2015).

Sobol, A. et al. Deubiquitinase OTUD6B isoforms are important regulators of growth and proliferation. Mol. Cancer Res. 15, 117–127 (2017).

Guasti, L. et al. Identification of a posttranslational mechanism for the regulation of hERG1 K+ channel expression and hERG1 current density in tumor cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 5043–5060 (2008).

Kang, Y., Guo, J., Yang, T., Li, W. & Zhang, S. Regulation of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel by Nedd4 family interacting proteins (Ndfips). Biochem. J. 472, 71–82 (2015).

Li, K. et al. Tetrameric assembly of K(+) channels requires ER-located chaperone proteins. Mol. Cell 65, 52–65 (2017).

Arcangeli, A. et al. HERG- and IRK-like inward rectifier currents are sequentially expressed during neuronal development of neural crest cells and their derivatives. Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 2596–2604 (1997).

Zheng, Z. & Song, Y. Integrated analysis of the voltage-gated potassium channel-associated gene KCNH2 across cancers. BMC Bioinforma. 24, 51 (2023).

Gabay M., Li Y., Felsher D. W. MYC activation is a hallmark of cancer initiation and maintenance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a014241 (2014).

Dhanasekaran, R. et al. The MYC oncogene - the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 23–36 (2022).

Gartel, A. L. & Shchors, K. Mechanisms of c-myc-mediated transcriptional repression of growth arrest genes. Exp. Cell Res 283, 17–21 (2003).

Layton, M. G. & Franks, L. M. Heterogeneity in a spontaneous mouse lung carcinoma: selection and characterisation of stable metastatic variants. Br. J. Cancer 49, 415–421 (1984).

Bertram, J. S. & Janik, P. Establishment of a cloned line of Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells adapted to cell culture. Cancer Lett. 11, 63–73 (1980).

Yada, M. et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 23, 2116–2125 (2004).

Hollern, D. P., Yuwanita, I. & Andrechek, E. R. A mouse model with T58A mutations in Myc reduces the dependence on KRas mutations and has similarities to claudin-low human breast cancer. Oncogene 32, 1296–1304 (2013).

Breuer, E. K. et al. Potassium channel activity controls breast cancer metastasis by affecting beta-catenin signaling. Cell Death Dis. 10, 180 (2019).

Lansu, K. & Gentile, S. Potassium channel activation inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells by activating a senescence program. Cell Death Dis. 4, e652 (2013).

Perez-Neut, M. et al. Activation of hERG3 channel stimulates autophagy and promotes cellular senescence in melanoma. Oncotarget 7, 21991–22004 (2016).

Becchetti, A., Duranti, C. & Arcangeli, A. Dynamics and physiological meaning of complexes between ion channels and integrin receptors: the case of Kv11.1. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 322, C1138–C1150 (2022).

Becchetti A., et al. The conformational state of hERG1 channels determines integrin association, downstream signaling, and cancer progression. Sci Signal. 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aaf3236 (2017).

Crociani, O. et al. hERG1 channels regulate VEGF-A secretion in human gastric cancer: clinicopathological correlations and therapeutical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 1502–1512 (2014).

Fukushiro-Lopes, D. F. et al. Preclinical study of a Kv11.1 potassium channel activator as antineoplastic approach for breast cancer. Oncotarget 9, 3321–3337 (2018).

Wang, J., Xie, L. Y., Allan, S., Beach, D. & Hannon, G. J. Myc activates telomerase. Genes Dev. 12, 1769–1774 (1998).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G., M.B. conceived the study, designed experiments, and supervised the project. N.E., D.D., performed cell culture, pharmacological treatments, and western blot analyses. R.N. carried out the cell-derived xenograft experiments and interpreted in vivo results. S.G. and M.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Cheng Zhan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eskandari, N., Delisi, D., O’Neil, R. et al. Activation of Kv11.1 potassium channel suppresses non-small cell lung cancer growth by promoting c-Myc degradation. Commun Biol 8, 1615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08917-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08917-9