Abstract

Deoxynivalenol (DON), a prevalent mycotoxin in contaminated feed, compromises ovarian function through dual disruption of redox homeostasis and metabolic networks. However, the precise mechanisms underlying DON-induced toxicity and effective strategies to mitigate its reproductive consequences remain incompletely understood. This study reveals the molecular mechanism by which DON induces ferroptosis in porcine granulosa cells through the glycolysis-H3K18la-STEAP3 axis and elucidates how melatonin alleviates DON toxicity via metabolic reprogramming. Multi-omics analyses demonstrate that DON exposure disrupts glycolysis, reduces lactate, and diminished H3K18la. This process is also mediated by the downregulation of P300, a key writer of lactylation, which collectively suppress H3K18la. The loss of H3K18la decreased STEAP3 expression, intracellular iron accumulation, elevated lipid peroxidation, and downregulation of GPX4, ultimately triggering ferroptosis. Furthermore, melatonin restores H3K18la and STEAP3 expression both in vitro and vivo, thereby suppressing ferroptosis and reducing oxidative stress. These findings provide novel molecular targets and therapeutic strategies for DON intoxication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deoxynivalenol (DON), also referred to as vomitoxin due to its intestinal toxicity to piglets, is a secondary metabolite of Fusarium graminearum and belongs to the class of monocenolic sesquiterpene compounds1,2. It is prevalently found in grain products and feed globally, posing a substantial threat to human and animal food safety, particularly in developing and underdeveloped nations3,4. According to the studies conducted by Wu et al. and Zhao et al., DON was detected in feed samples collected from different regions of China during 2013–2015 and 2018–2020. The detection rate of DON in full-price pig feed was 100% in 2018–2020. The DON contamination in wheat harvested in 2018 was the most severe, reaching 9186.4 μg/kg, which significantly exceeded the national standard (GB 13078–2017) of 1000 μg/kg5,6. Although DON is not classified as a carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, it exhibits acute and chronic toxicity to mammals1. Mammals ingesting DON will immediately experience symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal inflammation, which can eventually lead to long-term immune system and organ damage7. Compared with other animals, pigs are more susceptible to vomitoxin, possibly because the proportion of grains in pig feed is higher8. The small intestine and liver, as the main organs for food absorption and metabolism, are particularly vulnerable to toxin damage and can affect the health, immunity, and growth performance of pigs. Additionally, DON exposure can cause oxidative damage to the female reproductive systems of humans and mice9,10. The impact of DON on reproductive damage in female animals may be attributed to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which are induced by oocyte spindle abnormalities11,12. Cetin et al. investigated the response of a variety of cells to DON, of which the ovarian cell line CHO-K1 showed the highest sensitivity13. Nevertheless, the potential mechanism of DON-induced ovary damage in pigs has not been fully clarified. Based on this, studying the toxicological effects of DON on porcine granulosa cells and identifying corresponding treatment methods are of great significance for improving the reduced fertility caused by the toxin.

Dixon et al. identified a novel form of cell programmed death, ferroptosis, in 201214. Ferroptosis distinguishes itself from other forms of programmed death by the characteristic damage to the mitochondrial cristae and rupture of the cell membrane14. The onset of ferroptosis relies on the accumulation of iron ions within the cell. Intracellular accumulation of reduced iron (Fe2+) and lipid peroxides (PLOOH), which are generated from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) through Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4)-mediated catalysis, triggers the Fenton reaction15. This triggers an intracellular lipid peroxidation cycle, resulting in an overload of lipid peroxides within the cell. These lipid peroxides undermine the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane and the plasma membrane, thereby inducing cell death15. In previous studies, the excessive production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Malondialdehyde (MDA), and other oxidative byproducts in cells after mycotoxin-induced damage indicated that mycotoxin-induced damage might lead to ferroptosis16. The cell possesses a System Xc-/Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4)/Glutathione (GSH) reduction system to counteract oxidative damage and ferroptosis17. System Xc- is a complex composed of the Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11) and Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 2 (SLC3A2) proteins, which are accountable for transporting cysteine from the extracellular space into the cell and excreting glutamate from the cell17. Absorbed cysteine is utilized to synthesize glutathione, which is further employed by GPX4 to reduce lipid peroxides to their corresponding alcohols, reducing cellular oxidative damage and inhibiting ferroptosis. In numerous animals, GSH depletion and a decrease in the expression of ferroptosis inhibitory genes are witnessed after DON-induced damage, suggesting that DON causes damage by inducing ferroptosis18,19.

Histone lactylation is a recently discovered post-translational modification that occurs on the lysine residues of histones, utilizing lactate coenzyme A synthesized from lactic acid as the donor20. The primary substrate source for lactylation is L-lactic acid produced through intracellular glycolysis, and blocking glycolysis or inhibiting glucose intake will decrease the level of L-lactylation21. Similar to histone acetylation, histone lactylation impacts nucleosome and chromatin binding, promoting increased chromatin DNA accessibility22. Histone lactylation plays a role in regulating inflammation, tumorigenesis, nerve diseases, and muscle development by facilitating gene expression20,23,24,25. One specific site of histone lactylation, H3K18la, has been found to bind multiple gene promoters and enhance transcriptional regulation through marker enhancers26,27. In sepsis-induced lung injury, H3K18la induces ferroptosis by upregulating RNA methylation levels of ACSL4 via promotion of Methyltransferase Like 3 (METTL3) expression28. In prostate cancer, lactate-dependent H3K18la sustains cell proliferation by promoting GPX4 expression29. However, the function of histone lactylation during animal DON-induced injury remains unknown. DON inhibits the intracellular glycolysis level in HepG2 cells, resulting in depletion of related metabolites such as lactate (Gerdemann et al., 2022). Given the regulatory role of DON on lactate, a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory mechanisms by which DON influences lactylation modification levels is essential.

Melatonin is one of the most significant neuroendocrine hormones synthesized by mitochondria in the body, and its initial perception was to regulate the circadian rhythm30. A series of subsequent reports have also demonstrated that it has antioxidant and free radical scavenging capabilities as an antioxidant31,32,33. It can not only act as an antioxidant itself but also activate various antioxidant enzymes to exert antioxidant effects34,35. Given the established antioxidant properties of melatonin, it is imperative to investigate whether melatonin can mitigate ferroptosis induced by DON. In this study, we examined the participation of lactate metabolism and lactylation in the reproductive damage induced by DON in piglets. DON exposure resulted in ovarian damage in piglets, a decline in lactate levels in granulosa cells, and a reduction in H3K18la levels, thereby inhibiting the expression of Six-Transmembrane Epithelial Antigen of the Prostate 3 (STEAP3). The downregulation of STEAP3 triggered intracellular iron disorder, leading to ferroptosis. These findings illuminate a novel mechanism of the pig ovarian DON response involving lactate metabolism, highlighting melatonin as a potential therapeutic approach for ameliorating DON-induced reproductive damage in pigs.

Results

Don induces porcine ovarian oxidation damage

To investigate the effects of DON exposure on the ovaries of piglets, we established a piglet model fed with DON-supplemented diets (Fig. 1A). We found that dietary supplementation with high doses of DON significantly limited the growth of piglets compared to controls (Fig. 1B). The above results prove the successful establishment of the DON exposure model. Next, we used tissue and serum hormones to evaluate the damaging effects of DON exposure on the reproductive system of pigs. As shown in Fig. 1C, D, the size and weight of the ovaries of piglets exposed to DON decreased significantly, indicating that DON was highly toxic to the ovaries. Histopathological analysis revealed that follicle development was blocked at an early stage in the treatment group relative to the control group, and a large number of atresia and abnormally developed follicles were observed (Fig. 1E). Immunohistochemical results showed that the expressions of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and Antigen KI67 (KI67) in ovarian tissue of mice treated with DON were significantly lower than those in the control group (Fig. 1F, G). DON exposure not only lead to ovarian arrested development, but also lead to reproductive hormones related genes such as Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor (LHCGR), follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily a member 1 (CYP11A1), cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily a member 1 (CYP19A1), 3b-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (HSD3B1), and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Subunit Beta (FSHβ) were inhibited in mRNA and protein level (Fig. 1H–J). This further resulted in a significant decrease in serum Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Estradiol (E2), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), and Progesterone (P4) levels, suggesting that DON exposure caused overall damage to ovarian development in piglets (Fig. 1K–N). Oxidative stress, a signature symptom of mycotoxin exposure, has been reported to be involved in DON-induced reproductive damage in mice36, but its role in reproductive damage in piglets has been less studied. To determine the effect of DON exposure on ovarian oxidative stress in piglets, we assessed serum levels of several redox damage markers. For example, the end product of lipid peroxidation-MDA, key reducing agent GSH, and the ratio of reduced glutathione to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) are involved. The results showed that piglets exposed to DON showed increased MDA levels, decreased GSH levels and GSH/GSSG ratios, and showed higher levels of oxidative stress (Fig. 1O–R). The above evidence suggests that the growth and ovarian development of piglets exposed to DON-contaminated diets suffer organ damage caused by oxidative stress.

A Experimental flowchart of 28-day DON treatment in pigs (n = 6). B Body weight of pigs (n = 6). C The size of pig ovaries (n = 6). D Ovary weight of pigs (n = 6) E Representative histology of the pig ovary’s H&E staining. Scale bars: 100 µm. F, G Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67 and PCNA in pig ovarian tissues. Scale bars: 100 µm. H, I mRNA expression levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes in pig ovaries determined by qPCR (n = 3). J Protein levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes in pig ovaries determined by Western blot (WB), with Tubulin as the loading control (n = 6). K–N ELISA measurement of reproductive hormone levels (FSH, E2, LH, and P4) in pig ovaries (n = 6). O–R ELISA measurement of oxidative stress markers (MDA, GSH, and GSH/GSSG) in pig ovaries (n = 6). Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via unpaired Student’s t-test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (A) was created with FigDraw with copyright.

Don induces oxidation damage in porcine granulosa cells (GC)

Ovarian granulosa cells have the function of secreting estrogen and progesterone, and these hormones play a crucial role in maintaining female reproductive health and fertility. To further explore the damage mechanism of DON on the porcine reproductive system, this study used porcine ovarian granulosa cells to establish an in vitro research model. Porcine ovarian GCs were exposed to different concentrations (0–1 μg/ml) of DON for 24 h. The results indicated that DON decreased the cell viability in a dose - dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Compared with the control group, the viability of GCs treated with 0.25 μg/ml DON was significantly reduced, and the cell morphology also changed significantly, showing cell shrinkage, rounding, and even obvious cell death (Fig. 2B). Exposure to DON at concentrations exceeding 0.25 μg/ml severely disrupted the stability of hormone synthesis-related proteins in granulosa cells, suggesting a consequential loss of cellular functionality (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Based on these results, this study selected this concentration for subsequent research to determine whether DON could cause oxidative damage to granulosa cells. The results of immunofluorescence staining showed that the ROS level in cells treated with DON increased significantly (Fig. 2C, D). The results of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detection indicated that the MDA level in cells increased and the GSH level decreased after DON treatment (Fig. 2E, F), suggesting that DON treatment disrupted the oxidative homeostasis of granulosa cells and induced oxidative stress. Subsequently, this study found that the oxidative stress of granulosa cells induced by DON significantly inhibited the expression levels of steroid-synthesis-related genes and the content of estrogen (Fig. 2G–J), indicating that DON treatment might impair the function of GCs.

A Cell viability of porcine granulosa cells treated with different concentrations of DON (0–1 μg/ml) for 24 h, as determined by CCK8 assay (n = 6). B Morphological observation of porcine granulosa cells in the control and DON-treated groups (magnification 100×). C Representative images of ROS levels in granulosa cells from the control and DON-treated groups, observed by confocal microscopy. Scale bars: 40 µm. D–F ELISA measurement of ROS, GSH, and MDA levels (n = 6). G, H mRNA expression levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes in porcine granulosa cells determined by qPCR (n = 3). I Protein expression levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes in porcine granulosa cells determined by Western blot (WB), with Tubulin as the loading control (n = 3). J ELISA measurement of reproductive hormone E2 levels in porcine granulosa cells (n = 6). K Number of peptides detected in the two groups. L Score plot of principal component analysis (PCA) of proteomics data from control and DON-treated granulosa cells. M Volcano plot showing differentially expressed proteins. Red represents upregulated proteins, blue represents downregulated proteins, and gray represents no significant difference. N Heatmap showing the expression levels of antioxidant-related proteins in control and DON-treated granulosa cells (n = 3). O, P qPCR quantification of antioxidant genes SOD2 and CAT (n = 3). Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA (A)and unpaired Student’s t-test (D–H, J, O, P). (ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

To clarify the specific mechanism by which DON induces oxidative damage to granulosa cells, this study used proteomics to detect the protein expression levels before and after DON treatment. The mass spectrometry analysis results presented good data quality (Fig. 2K, L, Supplementary Fig. 1A). Proteomic analysis identified a total of 7182 proteins belonging to 90,605 peptides, among which 517 proteins were upregulated and 695 proteins were downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 1C–F, Supplementary Data 2). This study found that the expression levels of steroid-synthesis-related genes Hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 8 (HSD17B8) and StAR-related lipid transfer domain containing 5 (STARD5) decreased significantly after DON treatment (Fig. 2M). The heatmap showed that the expression levels of proteins involved in most of the antioxidant functions in cells decreased significantly after DON treatment (Fig. 2N). Next, we used qPCR to validate the expression levels of two genes, catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Fig. 2O, P). This evidence indicates that DON caused oxidative damage by disrupting the redox homeostasis of granulosa cells.

DON induces ferroptosis in porcine granulosa cells

Evidence suggests that ferroptosis participates in mycotoxin-induced oxidative damage. We speculated that ferroptosis might be the cause of DON-induced oxidative damage of porcine ovarian granulosa cells. The decreased expression of mitochondrial-localized SOD2 protein rather than cell membrane-localized SOD1 indicates that oxidative damage mainly occurs within mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). The results of functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the proteome revealed that the differentially expressed proteins were mainly enriched in cell components such as the cell membrane, mitochondria, mitochondrial membrane, and electron respiratory chain, etc(Fig. 3A). Concurrently, the proteomic results demonstrated that the expression level of GPX4 significantly declined and that of ACSL4 significantly increased after DON treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). The outcomes of WB, immunofluorescence, and qPCR further confirmed the alterations of GPX4 and ACSL4 (Fig. 3B–D, Supplementary Fig. 2E). Shrinkage of mitochondrial morphology is a hallmark characteristic of ferroptosis, the results of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicated that the mitochondrial morphology of cells shrank after DON treatment (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that the phenomena of GSH depletion and MDA increase resulting from cellular oxidative stress might be concomitant with DON-induced ferroptosis.

A GO cellular component enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins in control (CK) and DON-treated granulosa cells. The size of the dots represents the number of proteins, and the color represents the significance of the pathway. The x-axis indicates the enrichment factor, and the y-axis represents different functional terms. B–D Western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence analysis of GPX4 and ACSL4 protein abundance in CK and DON-treated granulosa cells. Scale bars: 40 µm. E Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing mitochondrial morphology in granulosa cells before and after DON treatment (scale bar: 4 µm and 0.4 µm). F, G Representative images of Fe²⁺ and ROS levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in CK, DON-treated, and Fer-1-treated granulosa cells observed by laser confocal microscopy (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. H, I Representative images of mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 probe) levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in CK, DON-treated, and Fer-1-treated granulosa cells observed by laser confocal microscopy (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. Red represents high mitochondrial membrane potential, green represents low mitochondrial membrane potential, and blue represents nuclei. Scale bars: 40 µm. J–L WB analysis of GPX4 and ACSL4 protein expression levels in different groups(n = 3). M–S qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of reproduction-related genes of different groups (n = 3). Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (G) or one-way ANOVA (I, K–S) with Tukey’s post hoc test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Ferrostatin-1(Fer-1) is the earliest reported ferroptosis inhibitor, which inhibits ferroptosis by suppressing lipid peroxidation and regulating iron ion metabolism14. To further confirm that DON can induce ferroptosis in granulosa cells, we co-cultured granulosa cells with DON and different concentrations of ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 (0.1–10 μM). Compared with the DON group, co-culturing with 0.2–5 μM Fer-1 could effectively improve cell viability, among which 1 μM Fer-1 had the most significant improvement effect (Supplementary Fig. 2F). Therefore, Fer-1 with a concentration of 1 μM was selected for subsequent experiments. Intracellular iron ions and lipid peroxides are markers of ferroptosis, while mitochondrial peroxides and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) are markers of mitochondrial activity. Chemical fluorescent probes were used to stain intracellular reactive oxygen species, iron ions, mitochondrial peroxides, and mitochondrial membrane potential. The results showed that after DON treatment, intracellular reactive oxygen species, iron ions, and mitochondrial superoxide significantly increased, while MMP significantly decreased, indicating that DON-induced mitochondrial damage and reduced its activity (Fig. 3F–I, Supplementary Fig. 2G). The addition of Fer-1 alleviated the increase in cellular and mitochondrial peroxides caused by DON exposure and improved mitochondrial function to a certain extent (Supplementary Fig. 2H). The expression of ferroptosis characteristic genes after Fer-1 treatment was detected, and it was found that the expression of GPX4 was significantly restored, while the expression of ACSL4 was inhibited (Fig. 3J–L, Supplementary Fig. 2I, J). Further detection of the expression of reproductive hormone-related genes showed that Fer-1 treatment significantly restored the expression levels and protein abundance of genes such as FSHβ, CYP11A1, and STAR, and the level of estrogen also increased to a certain extent (Fig. 3M–S, Supplementary Fig. 2K, L). The above evidence indicates that ferroptosis is the main way of DON-induced granulosa cell damage, and the use of ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 can improve DON-induced oxidative damage, enhance cell and mitochondrial activity, and improve cell function.

DON treatment decreases lactate and histone lysine lactylation (Kla)

Glycolysis serves as the primary energy-supplying pathway in granulosa cells37. To investigate the effect of DON on glycolysis in granulosa cells, we reanalyzed transcriptomic data from previous studies in which granulosa cells were treated with DON38. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that the glycolysis pathway was ranked first among significantly enriched pathways, indicating that these genes were highly expressed in the control group (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Proteomic analysis further demonstrated that hexokinase 2 (HK2), which catalyzes the first step of glycolysis by converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, was significantly downregulated at the protein level (Supplementary Fig. 3B). To detect differences in lactate levels before and after DON treatment, we employed LC-MS/MS-based targeted metabolomics to quantify metabolites involved in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. The results showed clear intra-group clustering and inter-group separation, indicating significant metabolic differences between the DON-treated and control groups (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Further analysis of metabolites involved in the glycolysis pathway among the 26 differentially detected metabolites revealed that DON treatment significantly reduced the levels of glucose and lactate (Supplementary Data 3). This finding was further validated using an ELISA kit (Fig. 4B–E, Supplementary Fig. 3D). Collectively, these multi-omics results demonstrate that DON treatment inhibits the glycolysis pathway in granulosa cells, leading to a significant reduction in intracellular lactate levels.

A Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing the top 10 functional enrichment results of all genes in the transcriptome. B Heatmap showing the relative levels of glycolysis-related metabolites before and after DON treatment. C, D Violin plots showing the relative levels of glucose and lactate in the two groups(n = 3). E ELISA measurement of lactate levels in ovarian GCs of different mouse groups (n = 9). Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of histone lactylation. F Schematic diagram of the structure and enzyme catalysis of histone lactylation, G Immunoblot analysis of pan-Kla in granulosa cells before and after DON treatment. H, I Prediction of potential lysine lactylation sites in porcine histone H3 and H4 using the CPLM database (http://cplm.biocuckoo.cn/index.php). J–L Western blotting analysis of site-specific histone lactylation in granulosa cells of control (CK) and DON-treated groups (n = 3). Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via unpaired Student’s t-test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (F) was created with FigDraw with copyright.

Lactate can serve as an epigenetic factor and bind to histone lysine residues, leading to histone lysine lactylation (Fig. 4F). As the donor of lactylation, the decrease in lactate levels significantly reduces the level of pan-lysine lactylation (Fig. 4G). Histones H3 and H4 exhibit relatively strong transcriptional regulatory functions, and multiple acetylation sites on H3 and H4 have been identified in humans and mice that play functional roles through transcriptional activation39. Since there are currently no reports on histone lactylation in pigs, we searched the CPLM database and found that each of porcine H3 and H4 contains four lysine residues capable of undergoing acetylation (Fig. 4H, I). Considering the high degree of conservation in the positions of acetylation and lactylation sites between humans and mice, we hypothesized that these sites may also undergo lactylation. To identify the specific histone lysine residues affected by DON treatment, we measured the changes in lactylation levels at eight lysine residues on histones H3 and H4 (Fig. 4J). Among these, H3K18 was the only site where lactylation levels were significantly reduced following DON treatment (Fig. 4K, L). H3K18la, as the most extensively studied histone lactylation site, has been reported to play a critical role in promoting gene expression39. Based on these findings, we propose that DON treatment disrupts glycolytic metabolism in granulosa cells, inhibits lactate production, and leads to reductions in both pan-lactylation and H3K18la levels, potentially affecting gene transcription and further influencing cellular function.

Lactate protects GCs from DON-induced ferroptosis via enhancing H3K18 lactylation

We hypothesized that lactate and H3K18la levels are crucial for maintaining the survival of granulosa cells. To validate this hypothesis, we treated granulosa cells with several substances that can modulate lactylation levels. Supplementation with lactate significantly increased cellular lactylation levels, alleviated DON-induced cell death, and we found that supplementation with Nala had a similar effect (Fig. 5A, B). In contrast, treatment with 2-DG alone, which blocks glycolysis, promoted granulosa cell death. Moreover, cells co-treated with 2-DG and DON exhibited significantly lower H3K18la levels and cell viability compared to cells treated with DON alone (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). These findings further confirm the protective role of lactate in granulosa cells. Both lactate and Nala supplementation effectively increased lactylation levels. However, lactate can simultaneously upregulate acetylation to promote gene transcription, whereas Nala exclusively modulates lactylation40. Therefore, we selected Nala to further investigate the effect of lactylation levels on toxin-induced ferroptosis in granulosa cells (GCs). The results showed that Nala supplementation effectively restored GPX4 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels and inhibited ACSL4 expression (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. 4C, D). Results of LCM and TEM revealed that Nala supplementation reduced intracellular iron levels and ROS levels, improved mitochondrial function and morphology (Fig. 5D–I). Functional assays demonstrated that Nala effectively restored the expression of genes related to reproduction and steroid hormone metabolism (Fig. 5J, K, Supplementary Fig. 4E–H). Western blot analysis further confirmed that the abundance of certain reproduction-related proteins and ferroptosis markers was improved following Nala supplementation (Fig. 5L, M).

A Cell viability of granulosa cells treated with control (CK), DON, DON + Nala (10 mM), or DON + lactate (10 mM) for 24 h, as determined by CCK8 assay (n = 6). B Immunoblot analysis of H3K18la levels in CK, DON-treated, DON + Nala (10 mM), and DON + lactate(10 mM)-treated groups, with H3 as the loading control. C qPCR analysis of GPX4 and ACSL4 gene expression levels in CK, DON-treated, and DON + Nala-treated granulosa cells (n = 3). D Representative confocal microscopy images of Fe²⁺ and ROS levels in CK, DON-treated, and DON + Nala-treated granulosa cells. (Scale bar: 40 µm). E Confocal microscopy images showing the intensity of the lipid peroxidation probe (BDP 581/591 C11) in granulosa cells of different groups. (Scale bar:40 µm). F Quantitative data for relative fluorescence of Fe²⁺ and ROS staining. G Confocal microscopy images showing mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 probe) and nuclear co-localization in granulosa cells of different groups. (Scale bar: 20 µm). H Quantitative data for relative fluorescence of BDP 581/591 C11 and JC-1 staining. I TEM images showing mitochondrial morphology in granulosa cells of different groups (scale bar: 20 µm). J, K qPCR analysis of the effects of Nala supplementation on the expression levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes (n = 3). L Western blot (WB) analysis of the effects of Nala supplementation on the protein expression levels of steroidogenesis and reproductive hormone-related genes. M WB analysis of the effects of DON + Nala co-treatment on GPX4 and ACSL4 expression. Significant changes in gene expression were observed in the treated groups compared to controls. Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (A, C, I, J) and two-way ANOVA (F, G) with Tukey’s post hoc test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

P300 and SIRT1 are the regulators for H3K18la in porcine GCs

P300 is currently recognized as the most extensively studied lactyltransferase, reported in humans and mice to catalyze the binding of lactyl-CoA to histone lysine residues in a lactate-dependent manner23,28 (Fig. 4F). Proteomic analysis revealed that P300 was the only histone acetyltransferase (HAT) family member downregulated in granulosa cells following DON treatment, suggesting that P300 plays a predominant role in regulating lactylation in porcine granulosa cells (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Fig. 5A).

A Heatmap showing differential expression of HAT family members in proteomic data before and after DON treatment (n = 3). B CCK8 assay showing cell viability in control (CK), DON-treated, DON + Nala co-treated, and P300 knockdown or inhibition + DON + Nala co-treated porcine granulosa cells after 24 h of treatment (n = 6). C, D Western blot (WB) analysis showing the relative abundance of H3K18la after treatment with different concentrations of C646, with H3 as the loading control (n = 3). E–H WB analysis showing the effects of P300 knockdown and overexpression on H3K18la under normal conditions and after Nala supplementation. H3 and Tubulin were used as loading controls for H3K18la and P300, respectively (n = 3). I–K Confocal microscopy images showing the effects of P300 knockdown on Fe²⁺ levels, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial membrane potential. (scale bar:40 µm). L Quantitative data for relative fluorescence of Fe2+, BDP 581/591 C11, and JC-1 staining. M Schematic diagram illustrating the interaction between P300 and lactyl-CoA. Amino acids involved in the interaction are shown as stick models, the compound molecule is represented as a green stick structure, and the EP300 (A0A8W4FCE1) protein molecule is depicted as a pink helical structure. N Protein sequence alignment of P300 across different species, highlighting the high conservation of arginine at position 1068 in the HAT domain. O, P WB analysis showing the effects of the P300 R1368A mutation on H3K18la with or without 10 mM Nala. Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Data in (A and D) were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data in (F, H, and L) were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data in (P) was evaluated via an unpaired Student’s t-test. (ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

Based on these findings, we investigated the role of P300 in porcine granulosa cells by using C646 (a P300 inhibitor) and siRNA to suppress P300 activity and expression, respectively. CCK8 assays demonstrated that the therapeutic effects of Nala against DON-induced toxicity were abolished under both treatment conditions (Fig. 6B). Western blot analysis showed that both interventions significantly reduced H3K18la levels, whereas P300 overexpression markedly enhanced H3K18la (Fig. 6C–H). Furthermore, P300 knockdown blocked the ability of Nala to restore mitochondrial activity, reduce intracellular ROS levels, and modulate ferroptosis-related gene expression (Fig. 6I–L, Supplementary Fig. 5B, C). The restorative effects of Nala on steroidogenesis and reproduction-related gene expression were also impaired following P300 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 5D–J). Notably, P300 overexpression in DON-treated granulosa cells significantly improved cell viability compared to wild-type controls (Supplementary Fig. 5K). Furthermore, an in vitro lactylation assay conclusively demonstrated P300-mediated catalytic activity toward H3K18la (Supplementary Fig. 5L). These results collectively indicate that the protective effects of lactate against DON-induced damage are mediated through its role as a precursor for P300-catalyzed lactylation.

To further elucidate the catalytic mechanism of how P300-mediated H3K18la, we performed molecular docking analysis using Autodock Vina to investigate the interaction between P300 and lactyl-CoA (PubChem: 1926-57-4), aiming to determine their binding mode and active sites (Fig. 6M). The results revealed a strong binding affinity between the HAT domain of P300 and lactyl-CoA, with lactyl-CoA embedded within the pocket structure of P300. Notably, R1368 extended into the central region of lactyl-CoA, forming multiple interactions, and exhibited the shortest distance to lactyl-CoA among all amino acid residues (Supplementary Fig. 5M). Conservation analysis across multiple species demonstrated that R1368 is highly conserved, suggesting its essential role in the interaction between P300 and lactyl-CoA (Fig. 6N). To validate our hypothesis regarding the functional importance of R1368, we generated a site-directed mutant by substituting arginine at position 1368 with alanine (R1368A) to disrupt the strong interaction with lactyl-CoA. Western blot analysis confirmed our prediction, as the R1368A mutation significantly reduced lactylation levels, and this reduction could not be rescued by lactate supplementation (Fig. 6O, P). These findings indicate that P300 catalyzes histone H3K18la through the interaction between R1368 in its HAT domain and lactyl-CoA.

SIRT1-3 and HDAC1-3 are widely recognized as lactylation erasers, while other HDAC family members also possess potential delactylation activity41. To identify candidate delactylases in porcine granulosa cells, we first analyzed the expression patterns of all HDAC family members based on proteomic data from porcine granulosa cells. Heatmap analysis revealed the expression of nine HDAC members and five SIRT members in granulosa cells, with no significant differences observed (Supplementary Fig. 5N). Given the detectable expression of HDAC1-3 and SIRT1-3 in porcine granulosa cells, we constructed corresponding siRNA-transfected cells to assess their effects on H3K18la. The results demonstrated that SIRT1 knockdown exhibited the most pronounced enhancement of H3K18la levels (Supplementary Fig. 5O, P). Consistent with P300, in vitro lactylation assays further substantiated the delactylase activity of SIRT1 (Supplementary Fig. 5L). These findings suggest that P300 and SIRT1 may serve as potential writer and eraser, respectively, and that the inhibitory effect of DON on H3K18la is primarily mediated through the suppression of P300 rather than the activation of SIRT1.

Inhibition of H3K18la decreases the transcription of STEAP3 and HSD3B1

To identify candidate genes regulated by H3K18la in ferroptosis, we performed CUT&Tag assays using an Anti-H3K18la antibody (PTM-1427RM) to mark candidate genes regulated by H3K18la (Fig. 7A). DON treatment enhanced the enrichment of H3K18la near transcription start sites (TSS), with 12.25% of differentially enriched peaks (DP) located within ±3 kb of gene promoters. Among these, 624 genes were associated with loss of DP in promoter regions (Fig. 7B–E, Supplementary Data 4). KEGG pathway analysis of the lost DP-associated genes revealed significant enrichment in the ferroptosis pathway (Fig. 7F). This pathway included four genes: ATG7, MAP1LC3C, STEAP3, and VDAC2. Visualization analysis showed that H3K18la peaks were highly enriched at the promoters of these genes in the control group, but their enrichment levels decreased after DON treatment (Fig. 7G, Supplementary Fig. 6A–C).

A Schematic diagram of the CUT&Tag workflow in DON-treated granulosa cells. B, C Genome-wide distribution of H3K18la and its enrichment near transcription start sites (TSS). Schematic of the experimental design illustrating the comparison between control (CK) and DON. Three biological replicates were performed for each group, and CUT&Tag sequencing was conducted to analyze H3K18 lactylation binding at gene promoters. D Heatmap showing differential H3K18 lactylation binding peaks at gene promoters, as assessed by CUT&Tag. The heatmap illustrates changes in lactylation modifications between CK and DON groups. E Volcano plot highlighting the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between CK and DON conditions, with genes categorized based on their lactylation status (gain, loss, stable). The plot shows significant changes in gene expression associated with H3K18 lactylation following sleep deprivation. F KEGG analysis of genes associated with promoter-enriched LOSS DPs. G, H IGV visualization showing the enrichment of H3K18la at the promoter regions of STEAP3 and HSD3B1. The tracks show clear changes in lactylation patterns at these gene promoters. I Enrichment ratio of H3K18la at the promoter regions of STEAP3 and HSD3B1 in DON-treated and DON + Nala co-treated granulosa cells (n = 3). J–L Effects of DON treatment and DON + Nala co-treatment on the gene and protein expression levels of STEAP3 and HSD3B1. (Scale bar:40 µm) Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (A) was created with FigDraw with copyright.

STEAP3 is a member of the STEAP family and contains two key domains for iron uptake: a six-transmembrane domain at the COOH-terminal and a cytoplasmic N-terminal oxidoreductase domain. Based on the observed changes in intracellular iron levels, we selected STEAP3 to investigate its potential regulatory mechanism in granulosa cell ferroptosis.

Additionally, KEGG analysis revealed enrichment in the ovarian steroid hormone pathway. Among the genes in this pathway, HSD3B1, which encodes an enzyme involved in steroid hormone metabolism, also showed a significant decrease in H3K18la peaks after DON treatment. This suggests that DON may induce reproductive damage not only by triggering ferroptosis but also by disrupting steroid hormone synthesis (Fig. 7H). Further confirmation through Chip-qPCR demonstrated that, compared to the control group, the enrichment of H3K18la at the promoters of STEAP3 and HSD3B1 significantly decreased after DON treatment, while lactate supplementation ameliorated this effect (Fig. 7I). qPCR results also indicated that lactate restored the DON-induced reduction in the expression levels of STEAP3 and HSD3B1 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7J). These findings suggest that DON treatment suppresses STEAP3 transcription by reducing H3K18la levels.

We further analyzed the protein abundance of STEAP3 after DON treatment using immunofluorescence and Western blot (WB). The results showed that STEAP3 abundance significantly decreased compared to the control group, but the addition of Nala reversed this phenomenon (Fig. 7K, L).

We also analyzed the downregulated H3K18la-binding motifs in the promoter regions and found that the PPARα motif was significantly enriched (Supplementary Fig. 6D, E). PPARα exerts antioxidant effects by catalyzing the expression of CAT and SOD, which scavenge intracellular ROS, representing a classic pathway for cellular protection against oxidative damage. qPCR results showed that toxin treatment suppressed the expression levels of PPARα downstream genes, SOD and CAT, by reducing H3K18la levels (Supplementary Fig. 6F), indicating that DON enhances cellular damage both by promoting ferroptosis and by inhibiting antioxidant gene expression.

To further confirm the transcriptional regulation of STEAP3 by H3K18la, we transfected cells with either wild-type histone H3 or the mutant H3K18R (mimicking the non-lactylated state) to observe STEAP3 expression when H3K18la levels were suppressed. Western blot (WB) confirmed that H3K18R reduced intracellular H3K18la levels to some extent, validating the effectiveness of this approach in porcine granulosa cells (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Further analysis revealed that STEAP3 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels was significantly lower in H3K18R-treated cells compared to the wild-type (WT) group, confirming that reduced H3K18la levels decreased STEAP3 expression (Supplementary Fig. 7B, C). Interestingly, the addition of Nala (sodium lactate) to H3K18R cells failed to restore STEAP3 expression, indicating that lactate’s restorative effect on STEAP3 depends on H3K18la levels (Supplementary Fig. 7B).

Additionally, we introduced another histone H3 mutant, H3K18T, which mimics lactylation modification, into the cells. The results showed that STEAP3 expression levels were elevated in the H3K18T group (Supplementary Fig. 7D). Confocal microscopy revealed that H3K18T cells exhibited reduced iron levels, decreased lipid peroxidation, improved mitochondrial function, and reduced oxidative damage compared to H3K18R cells (Supplementary Fig. 7E–G). These results demonstrate a positive correlation between H3K18la levels and STEAP3 expression, suggesting that H3K18la may regulate intracellular iron levels and influence ferroptosis by promoting STEAP3 expression.

DON exposure induced ferroptosis by downregulating H3K18la and STEAP3 expression

To investigate the role of STEAP3 in DON-induced ferroptosis in granulosa cells, we transfected normal granulosa cells with STEAP3-specific siRNA (Fig. 8A). The results demonstrated that STEAP3 knockdown significantly inhibited cell viability (Fig. 8B). Further analysis revealed that STEAP3 deficiency led to increased intracellular iron levels and ROS accumulation, accompanied by decreased GPX4 expression and impaired cell viability, indicating that STEAP3 depletion induces ferroptosis (Fig. 8C–E, Supplementary Fig. 8A, B).

A WB analysis of STEAP3 protein levels in granulosa cells transfected with Si-NC or Si-STEAP3. B CCK8 assay showing cell viability in granulosa cells transfected with Si-NC or Si-STEAP3 (n = 6). C Immunofluorescence analysis of GPX4 protein expression in granulosa cells transfected with Si-NC or Si-STEAP3. (Scale bar:40 µm). D, E Representative images of Fe²⁺ and ROS levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in Si-NC and Si-STEAP3 granulosa cells observed by laser confocal microscopy (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. F–H Representative images of lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial membrane potential levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in Si-NC, Si-STEAP3, and Si-STEAP3 + Fer-1 granulosa cells observed by laser confocal microscopy (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. I–K Confocal microscopy images and their relative fluorescence intensity showing changes in lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial membrane potential in granulosa cells treated with OE-NC, OE-NC + DON, and OE-STEAP3 + DON. (Scale bar:40 µm) Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via Student’s t-tests and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. (ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

To further explore the relationship between STEAP3 and ferroptosis, we treated STEAP3-knockdown cells with Fer-1. The results showed that Fer-1 treatment effectively suppressed iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation induced by STEAP3 deficiency, improved mitochondrial membrane potential, and significantly alleviated cell death (Fig. 8F–H). To mechanistically delineate STEAP3 deficiency-driven ferroptosis via iron overload, deferoxamine (DFO) was employed to chelate intracellular labile iron pools. DFO demonstrated dose-responsive restoration of cellular viability in STEAP3-deficient GCs (Supplementary Fig. 8C). DFO administration not only attenuated the STEAP3 knockdown-induced Fe²⁺ accumulation but also concomitantly rescued mitochondrial bioenergetics and mitigated intracellular lipid peroxide formation (Supplementary Fig. 8D). These findings suggest that STEAP3 maintains iron homeostasis in porcine granulosa cells, and its deficiency leads to intracellular iron overload, thereby triggering ferroptosis.

Subsequently, we established a STEAP3 overexpression model to determine its protective role against DON-induced ferroptosis in granulosa cells (Supplementary Fig. 8E). Compared to OE-NC cells, STEAP3-overexpressing cells exhibited enhanced resistance to DON treatment, characterized by increased GPX4 expression, reduced iron levels, ROS accumulation, and lipid peroxidation, as well as improved mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 8I–K, Supplementary Fig. 8F, G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that DON treatment induces ferroptosis in granulosa cells by suppressing STEAP3 expression and disrupting cellular iron homeostasis.

Melatonin promotes STEAP3 expression by improving glycolysis-lactate-H3K18la

Melatonin is a crucial antioxidant in animals and has been shown to ameliorate deoxynivalenol (DON)-induced apoptosis in human granulosa cells36. To determine whether melatonin can alleviate DON-induced reproductive damage in pigs, we investigated the protective effects of different concentrations of melatonin (MEL, 0.1–10 µg/mL) on DON-induced injury in porcine granulosa cells. The CCK8 assay results demonstrated that 1 µg/mL melatonin significantly improved the viability of granulosa cells (Fig. 9A). The protective effects of melatonin were also reflected in the restoration of estradiol (E2) and reproductive hormone-related genes (Fig. 9B, Supplementary Fig. 9A–G). Further analysis revealed that 1 µg/mL melatonin effectively reduced intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), iron ions, and lipid peroxidation, while improving mitochondrial function (Fig. 9C–G).

A CCK8 assay showing cell viability in granulosa cells co-cultured with DON and different concentrations of melatonin (0.1, 1, 10 µM) for 24 h (n = 6). B ELISA measurement of E2 levels in granulosa cells cultured with DON alone or co-cultured with 1 µM melatonin for 24 h (n = 6). C, D Representative images of Fe²⁺ and ROS levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in granulosa cells cultured with DON alone or co-cultured with 1 µM melatonin for 24 h (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. E–G Representative images of lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial membrane potential levels and their relative fluorescence intensity in CK, DON, and DON + MEL granulosa cells observed by laser confocal microscopy (n = 3). Scale bars: 40 µm. H ELISA analysis showing changes of lactate levels (n = 6) in granulosa cells cultured with DON alone or co-cultured with 1 µM melatonin for 24 h. I Schematic diagram of melatonin treatment in mice for 28 days (n = 6). J, K ELISA measurement of changes in reproductive hormones (FSH) and oxidative stress markers (GSH) in the serum of mice treated with DON alone or co-treated with DON + melatonin (n = 6). L Immunofluorescence analysis of cell proliferation (Ki67) levels in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups. (Scale bar: 40 µm) M–O qPCR analysis of glycolysis-related gene expression in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups (n = 3). P ELISA measurement of lactate levels in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups (n = 6). Q Immunofluorescence analysis of H3K18la levels in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups. (Scale bar: 40 µm) R qPCR analysis of STEAP3 gene expression in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups (n = 3). S ELISA measurement of Fe2+ levels in ovarian tissues of different mouse groups (n = 6). Bars indicate the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, with significance levels denoted as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (I) was created with Biorender.

Melatonin supplementation has been shown to enhance glycolysis and alleviate oxidative stress through metabolic reprogramming42. We hypothesized that this phenomenon also exists in porcine granulosa cells. Since the glycolysis initiation gene HK2 was significantly suppressed by DON, we measured the expression levels of HK2 before and after melatonin supplementation using qPCR. The qPCR results revealed that HK2 expression decreased after DON treatment, but melatonin supplementation restored its expression (Supplementary Fig. 9H). Based on this, we further assessed lactate levels in granulosa cells. As expected, melatonin significantly increased the lactate content that was reduced by DON (Fig. 9H). These results confirm that melatonin can improve lactate levels by enhancing glycolysis.

Additionally, we investigated the regulatory mechanism of MEL-H3K18la-STEAP3. Consistent with our expectations, compared to DON-treated granulosa cells, H3K18la levels were significantly increased, and STEAP3 expression was elevated in melatonin-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 9I). Melatonin supplementation also restored the expression of GPX4 and suppressed ACSL4, indicating that melatonin can inhibit DON-induced ferroptosis in granulosa cells (Supplementary Fig. 9J, K). To further determine whether the protective effects of melatonin depend on STEAP3, we silenced STEAP3 using siRNA transfection in granulosa cells, treated them with DON, and then supplemented them with melatonin. We found that melatonin could not rescue ferroptosis caused by STEAP3 deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 9L). These findings suggest that melatonin alleviates DON-induced ferroptosis by enhancing lactylation modification and promoting STEAP3 gene expression.

To validate these findings, we established a mouse model of ovarian injury induced by DON and treated the mice with 20 mg/kg melatonin to observe whether melatonin exerts protective effects on the ovaries (Fig. 9I). The results showed that the body weight of the DON-treated group significantly decreased, while the weight of the DON + melatonin co-treatment group was closer to normal levels compared to the DON group (Supplementary Fig. 10A). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining revealed that DON treatment impaired ovarian health, leading to follicular atresia and nuclear pyknosis, which were alleviated by melatonin supplementation (Supplementary Fig. 10B). Similarly, the number of oocytes and their maturation rate were significantly lower in DON group than those of the control group mice. However, they were significantly improved in the MEL co-treatment group. Serum hormone levels and ovarian oxidative damage indicators demonstrated that melatonin mitigated the DON-induced decline in reproductive hormone levels, reduced MDA accumulation, and rescued GSH depletion (Fig. 9J, K; Supplementary Fig. 10E, F). Immunohistochemistry results showed that DON treatment significantly reduced the levels of PCNA and KI67, while melatonin supplementation effectively reversed this phenomenon (Fig. 9L; Supplementary Fig. 10G). qPCR results indicated that melatonin promoted the expression of reproductive hormone-related genes (Supplementary Fig. 10H–M). These results confirm the successful establishment of a melatonin-treated mouse model of DON-induced ovarian injury.

To demonstrate that melatonin supplementation alleviates ovarian oxidative damage by enhancing the H3K18la-STEAP3 axis through metabolic reprogramming and lactate accumulation, we first examined the expression of key glycolysis-related genes, including HK2, 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase (PFKFB), Lactate Dehydrogenase A (LDHA), and blood lactate levels. The results showed that melatonin enhanced the expression of HK2, PFKFB, and LDHA, leading to increased blood lactate levels and elevated H3K18la (Fig. 9M–Q; Supplementary Fig. 10N). To determine whether the rise in H3K18la levels promoted STEAP3 expression in the ovaries, we assessed STEAP3 expression levels in different groups using qPCR and immunofluorescence. DON suppressed STEAP3 expression in the ovaries, and melatonin effectively reversed this effect (Fig. 9R, Supplementary Fig. 10O). Based on the function of STEAP3, we measured iron levels in the ovaries and detected GPX4 expression using immunofluorescence. Melatonin supplementation significantly reduced iron levels and restored GPX4 expression, which was suppressed by DON (Fig. 9S, Supplementary Fig. 10P), indicating that melatonin alleviates ovarian tissue damage by inhibiting DON-induced ferroptosis. In summary, these results demonstrate that melatonin supplementation effectively mitigates DON-induced ovarian injury in mice by enhancing the glycolysis-H3K18la-STEAP3 axis.

Discussion

In this study, through the piglet model and cell experiments, we demonstrated that deoxynivalenol (DON) exposure can induce reproductive damage in piglet ovaries and granulosa cells by triggering ferroptosis. We found that, mechanistically, DON exposure blocks glycolysis and lactate production in porcine granulosa cells, reduces the level of H3K18la, inhibits the expression of STEAP3, leading to an increase in intracellular ferrous ions, thus inducing ferroptosis. Lactate culture effectively improves the cell viability of DON-exposed granulosa cells by restoring H3K18la. Inhibiting P300 and knocking down STEAP3 both block the repair effect of lactate. Most importantly, we discovered that melatonin can effectively alleviate the reproductive damage caused by DON exposure at both the cellular and animal levels by restoring the H3K18la level, providing a new potential treatment option for animals exposed to DON in actual production (Fig. 10).

DON is one of the most harmful toxins in food safety and livestock production43. To better understand the mechanism by which DON causes reproductive damage in piglets, we constructed a DON-induced cell injury model using porcine granulosa cells. Granulosa cells, as important members of the reproductive system, provide energy and hormones to oocytes, regulate follicular atresia and apoptosis, and maintain the existence of the cumulus-oocyte complex within a specific cycle44,45,46. Ferroptosis has been identified as a new form of cellular oxidative damage, featuring unique initiation mechanisms and injury phenomena14. Currently, numerous studies have shown that mycotoxins, including DON, exert their toxicity by inducing ferroptosis in cells/organisms47,48. The core mechanism lies in the counteraction between the reduction system represented by GPX4/GSH and the oxidation system represented by Fe²⁺/ACSL4/PLOOH49. Therefore, a decrease in GPX4/GSH and an increase in Fe²⁺/ACSL4/PLOOH can be regarded as markers of ferroptosis. As the initiation site of ferroptosis, the atrophy of cell mitochondria morphology and the decline of mitochondrial membrane potential after DON treatment provide important evidence for us to judge the occurrence of ferroptosis50. Notably, with deepening investigations into ferroptosis mechanisms, regulatory pathways independent of the GPX4-GSH axis continue to be discovered, including the CoQ10-dependent FSP1/DHODH system and the GCH1-BH4 biosynthesis pathway. In DON-induced porcine intestinal injury models, FSP1 expression was suppressed by DON, while the roles of DHODH and GCH1 in mycotoxin-induced ferroptosis remain unreported. Our proteomic analysis failed to detect FSP1 and GCH1 expression, while a significant decrease in DHODH expression was observed. The potential involvement of DHODH in mitigating DON-induced ferroptosis in granulosa cells warrants mechanistic investigation in future studies.

STEAP3 is responsible for the conversion of intracellular ferric iron to ferrous iron. Currently, some articles have reported that in hepatocytes and tumor cells, the absence of STEAP3 leads to an increase in intracellular iron ion levels, inducing cellular oxidative stress51. Compared with wild-type (WT) mice, Zhang et al. induced more iron accumulation and a stronger inflammatory response in STEAP3-knockout mice through lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induction, which may be due to the induction of cellular ferroptosis52. STEAP3 had been reported to be regulated by classical epigenetics. Lv et al. analyzed the changes in histone modifications associated with STEAP3 in the ENCODE database. The results showed that classic super-enhancers such as H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 were significantly enriched on STEAP353. They also found that knocking down P300 inhibited the enrichment of H3K27ac in three regions of the STEAP3 gene, thus significantly reducing the expression of the STEAP3 gene and accompanying a phenotype of inhibited cell proliferation.

Based on the lactate transferase activity of P300, we further extended their findings and proposed another regulatory mechanism of P300, which was to promote STEAP3 gene expression by catalyzing H3K18la in porcine granulosa cells, thereby affecting cell viability. Since H3K18la can also co-mark enhancers with H3K27ac and H3K4me3, whether H3K18la can enhance STEAP3 remains to be further studied, and other peaks bound by H3K18la can be further explored for potential enhancer activity26. Although the function of STEAP3 in maintaining iron homeostasis in humans and mice is relatively well understood, its function in pigs has not been reported yet. We found that STEAP3 expression in porcine granulosa cells treated with DON was inhibited by H3K18la depletion, increasing the intracellular divalent iron ion level, which triggered ferroptosis. Notably, many non-histone lactylation modifications have been reported to play important roles, such as EGR1 and XRCC1 nuclear translocation, and LZKF1 transcriptional activity regulation54,55. The latest research indicates that there is a direct synergistic regulatory relationship between the lactylation of histones and non-histones (Lu et al.54; Sun et al.56). While H3K18la could activate the transcription of target genes, lactylation that occurs in non-histones can exert secondary regulation at the functional level on the same biological process. The two interact specifically in time and space to form a synergistic effect of epigenetic regulation, significantly enhancing the biological functions related to metabolic reprogramming. In this study, we were unable to further explore whether STEAP3 could be lactylated and the associated potential function. Future work can explore the importance of STEAP3 lactylation in iron homeostasis.

The process by which cell gene expression and related metabolites are restored under the induction of other factors is called metabolic reprogramming. In boar germ cells damaged by heat stress, the addition of melatonin significantly increases the levels of key glycolytic genes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2), ALDOA, GAPDH, and LDHA in glucose metabolism through metabolic reprogramming, and increases the lactate level, thereby enhancing cell viability42. In HT2-induced testicular interstitial injury, melatonin can alleviate tissue damage through the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase/glutathione pathway. Knocking out glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase weakens the therapeutic effect of melatonin57. Melatonin can alleviate the oxidative damage of mouse granulosa cells and meiotic defects of oocytes induced by DON10,36. Our research shows that the supplementation of melatonin can restore the expression of core glycolytic genes through metabolic reprogramming of glucose metabolism in porcine granulosa cells and mouse ovaries, respectively, thereby improving lactate production, further enhancing lactylation, and inhibiting ferroptosis. The results of supplementing melatonin to STEAP3-knockout granulosa cells indicate that the therapeutic effect of melatonin depends on the enhanced expression of STEAP3 by H3K18la.

In conclusion, this study provides the first experimental evidence that mycotoxins directly disrupt glycolytic metabolism and subsequently suppress histone lactylation—a previously unrecognized epigenetic mechanism driving cell ferroptosis. We are the first to establish the causal link between mycotoxin exposure, H3K18la-dependent transcriptional regulation, and iron homeostasis dysregulation through a lactate-H3K18la-STEAP3 axis. These findings not only reveal a novel molecular paradigm for deoxynivalenol (DON)-induced reproductive toxicity in mammals but also pioneer the discovery that melatonin counteracts mycotoxin damage by rescuing histone lactylation-mediated gene networks. Our work fundamentally expands the mechanistic understanding of environmental toxin pathogenesis by connecting metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic modification, and ferroptosis execution, while offering actionable therapeutic strategies for improving animal reproductive health.

Materials and methods

Fusarium culture and DON production

A suitable quantity of the cryopreserved Fusarium graminearum (ACCC39294) was retrieved and pre-cultured in Chafer’s medium at 30 °C with 85% humidity for 5 days to enhance spore production. Following this, the Fusarium graminearum spores were inoculated into Cargill piglet feed and thoroughly mixed to achieve a 20% moisture content. The mixture was then incubated in a controlled environment at 28 °C and 85% humidity for 17 days. During the incubation period, the incubation environment was maintained with sufficient airflow to ensure uniform fungal growth. After the 17-day cultivation period, the deoxynivalenol (DON) content in the Cargill piglet feed was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) according to the method specified in DB13/T 2954–2019 for DON determination in feed. The quantification of DON employed a Waters TQ-S LC-MS/MS system with strict adherence to GB 5009.111-2016. Separation was achieved using a Waters Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 column (1.7 μm particle size, 2.1 mm × 50 mm), maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of: Phase A: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile, Phase B: 0.1% formic acid in ultrapure water. A six-minute gradient elution program was optimized as follows: Initial conditions (10% A, 90% B) transitioned linearly to 50% A at 1.5 min, rapidly increased to 95% A at 1.6 min (held until 4.5 min), and returned to initial conditions at 4.6 min for re-equilibration. The flow rate was constant at 0.3 mL/min with an injection volume of 2 μL. For mass detection, positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) was applied with a capillary voltage at 2.82 kV. DON-specific transitions were monitored: m/z297→231.1 (qualitative ion) and m/z297→249.1 (quantitative ion). Source parameters included 150 °C ion source temperature and 350 °C desolvation temperature under 700 L/h nitrogen flow. The mycotoxin content determined in this experiment is provided in the supplementary materials.

Animal experiments

The animal experimental protocol for this study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Anhui Agricultural University under permit no. AHAU20201025.

For the piglets experiment, a total of 12 female three-way hybrid piglets [(Duroc × Landrace) × Large White] (5 weeks of age) purchased from Lu'an Shitun Husbandry were randomly divided into two groups, with six piglets in each group housed individually. Both groups were guaranteed free access to water. The CK group was fed with the original Cargill piglet feed, and the DON group was fed with DON excess piglet feed (Fig. 1A). All piglets were fed continuously for 28 days and weighed weekly. On the day of slaughter, serum was collected from the anterior vena cava and centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min before cryopreservation at −80 °C for subsequent hormone assays. At the end of the experiment, all piglets were euthanized by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital, and ovarian tissues were collected for pathological examination.

For the mouse experiment, eighteen 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Wuhan Sevier Bio (Wuhan, China) and bred at the experimental platform of Anhui Agricultural University. These mice were divided into three groups (n = 6), including a control group (CK), a DON treatment group (DON, 200 µg/kg), and a melatonin treatment group (20 mg/kg MEL + 200 µg/kg DON). DON and MEL were dissolved in sterile water, and the DON and MEL groups were given DON by gavage at 8 am daily, and the CK group was fed an equal volume of saline. The MEL group was given MEL by gavage at 16 PM, and the other two groups were given the same amount of normal saline33,58. The three groups of mice were housed in the same environment with AD libitum access to food and water. After 28 days of feeding, mice were sacrificed, and ovarian tissue and blood samples were collected.

Oocyte isolation

For superovulation and collection of metaphase II (MII) stage oocytes, all mice were subsequently treated with 5 IU hCG (Sigma). After 13 h, the COCs were harvested from the oviducts of different groups.

HE staining

In brief, the procedure involves fixing fresh ovary tissue of porcine and mouse in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h, followed by trimming, dehydrating through a graded ethanol and xylene series, embedding in paraffin, and sectioning at 4 µm thickness. The sections are then floated on a water bath, transferred to slides, and dried at 60 °C. For staining, the sections are deparaffinized, stained with Harris hematoxylin, differentiated with acid alcohol, and counterstained with eosin. The sections are then dehydrated, cleared with xylene, mounted, and examined under a microscope for image capture and analysis.

Serum hormone

Hormones of the mouse and porcine were determined using a commercially available assay kit (Jingmei Biotechnology) via the ELISA method.

Western blot

Cell or tissue of porcine lysis was performed in RIPA buffer with the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail. Equal amounts of protein were separated via SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, MA, USA), and probed with corresponding primary antibodies as specified. Tubulin or GAPDH was applied as the loading control for proteins, and histone H3 for histone lactylation. Detailed antibody information is provided in the attached table.

Cell culture

Porcine ovarian granulosa cell culture methods were described in detail in a previous study59. Briefly, cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin antibiotic mixture (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). This cultivation was carried out at a temperature of 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Drug treatments

2-DG (MCE; Cat. No. HY-13966), lactate (MCE; Cat. No. HY-B2227), Nala (Macklin; S817880), and melatonin (MCE; Cat. No. HY-B0075) were dissolved in water as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Ferrostatin-1 (MCE; Cat. No. HY-100579), c646 (MCE; Cat. No. HY-13823), A485 (MCE; Cat. No. HY-107455), DFO (MCE; Cat. No. HY-D0903) and DON (MCE; Cat. No. HY-N6684) were dissolved in DMSO as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Some drug concentrations were determined according to previous reports. Specifically, 10 mM of 2-DG, lactate, and Nala and 20 or 50 µmol/L of C646 were used20,40. For other drugs, DON, Fer-1, A485, and Melatonin, different concentrations were used to determine the optimal effect concentration. Cells were transfected with the P300 and STEAP3 overexpression plasmid or a negative control plasmid.

Cell morphological observations

We used a microscope (Leica Microsystems DM2500, Wetzlar, Hessen, Germany) to examine the cellular morphology photographs after different treatments.

Cell viability assay

Porcine GCs were seeded into 96-well plates (20000 cells per well) and cultured overnight. The cells were then treated with the corresponding drugs added to each well as needed for the experiment, and the cells were cultured for an additional 24 h. 5 μL CCK8 solution (Beyotime, C0038, China) was added to each well, and after 3 h of incubation, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA).

TEM analysis

Porcine GC pellets were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in gradual ethanol and propylene oxide, embedded in Epon, and cured for 24 h at 60 °C. Ultrathin sections (50 nm) were placed onto 200 mesh copper grids and double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before transmission electron microscopy analysis (HITACHI HT7700 Exalens).

RNA isolation and qRT‒PCR assays

For the ovary of porcine and mouse and GCs, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (15596-018, Invitrogen). 200 ng total RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (1708890, Bio-Rad). qRT‒PCR was carried out using a CFX96 real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (1708880, Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A melting curve was created for each amplicon to verify its accuracy. The levels of target mRNAs were normalized to those of β-actin. The primer sequences are listed in Table S3.

Transcriptomics data analysis

Regarding the GC's transcriptome data used in this paper, we obtained the dataset published in 2019 by Yang et al.38 from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Its accession number is No. PRJNA553632.

LC-MS/MS-based proteomics analysis

A cell count of 1 × 107 GCs was utilized for proteomic analysis. For cell samples, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA) on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 20 min, and 4 °C). The protein solution was precipitated with acetone, and was reduced with 50 mM dithiothreitol for 1.5 h at 30 °C. The protein solution was alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, 100 mM TEAB was added to the urea in the protein sample that was then digested overnight by trypsin at a 1:50 trypsin-to-protein mass ratio. Finally, Bioinformatic analysis methods have been described in previous studies60.

Targeted metabolomics analysis

A cell count of 2 × 107 GCs was utilized for metabolomics analysis. Resuspend the cell pellet in 100 μL ultrapure water, mix well, take 50 μL of the suspension, add 200 μL pre-cooled methanol, vortex at 2500 r/min for 2 min, freeze the sample in liquid nitrogen for 5 min, thaw on ice for 5 min, vortex for 2 min, repeat this freeze-thaw-vortex cycle 3 times, centrifuge at 12,000 r/min, 4 °C for 10 min, transfer 200 μL supernatant to a new tube, store at −20 °C for 30 min, centrifuge again under the same conditions, take 180 μL supernatant, filter through a protein precipitation plate, analyze using UPLC (Waters ACQUITY H-Class D) and MS/MS (QTRAP® 6500+), prepare standard solutions, construct a database from chromatographic peak intensities, perform qualitative analysis using MultiQuant 3.0.3 software, for the remaining 50 μL suspension, repeat the freeze-thaw process 3 times, centrifuge, determine protein concentration by the BCA method, and use protein concentrations of parallel samples to calibrate metabolomics data.

Cell staining by fluorescent probes

Porcine GCs were used for fluorescence probe staining. All stains were performed according to manufacturing protocols. FerroOrange (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.; Cat. No. F374), 1 μM for 30 min; Lipid Peroxidation Probe -BDP 581/591 C11 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.; Cat. No. L267), 200 µmol/l for 2 h; JC-1 MitoMP Detection Kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.; Cat. No. MT09), 4 µmol/l for 30 min; MitoBright ROS Deep Red - Mitochondrial Superoxide Detection (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.; Cat. No. MT16), 10 μmol/l for 30 min. Data analysis and visualization were performed using ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

We referred to the method of Wang et al. for immunofluorescence of animal ovarian tissues and granulosa cells61. The pre-prepared ovarian sections of mouse and porcine were dewaxed and rehydrated using xylene and gradient ethanol, respectively. Subsequently, sections were subjected to 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) for high-temperature antigen retrieval, followed by blocking with 10% donkey serum for 1 h before incubating with primary antibodies overnight. After this, the sections were exposed to fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37 °C. Finally, nuclei were visualized using 4′,6-diamidino-2phenylindole (DAPI) staining. For immunofluorescence staining of GCs, the collected GCs were treated with 4% PFA and 0.25% Triton X-100 for fixation and permeabilization, respectively. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), GCs were transferred to primary antibodies to incubate overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with PBS, the GCs were exposed to fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37 °C. The nuclei were visualized with DAPI. All the sections and GCs were submitted to an LSM 800 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) to capture images with the same parameters.

Cleavage under targets and tagmentation (CUT&Tag) and data analysis

The CUT&Tag experiments of DON-treated GCs were performed by Wuhan Frasergen Bioinformatics Co., Ltd. In brief, magnetic bead linkage, antibody incubation, ProteinG-Tn5 binding, library construction, and sequencing were performed by Frasergen. Data were filtered using Trimmomatic(v0.39) in the CUT&Tag analysis pipeline. Bowtie2 was used to align the clean data to the reference genome, and Samtools(v1.12) and Picard(v2.25.6) were used to filter the low-quality alignment data. MACS3(v3.0.0a6) was used to perform Peak calling on the final valid data. DiffBind was employed to detect differential peaks (DP) from peak sets. Peaks with|log2Fold Change | >0.58 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were defined as the statistically significant DP. We used the deepTools(3.5.1) package to map the signal enrichment intensities of Peak, TSS, and Genebody regions, and the ChIPseeker package was used for gene annotation of Peak. Genes which enriched in the loss of DP promoter were performed to Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. For genome browser representation, the BIGWIG files were loaded using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)62.

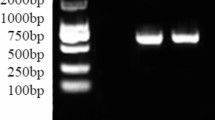

ChIP-qPCR

The cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, and crosslinking was quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and collected. The cells were lysed on ice for 10 min in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% SDS). Next, the lysed cells were sonicated with a Misonix sonicator 3000 (9 W; 20 s on; 40 s off; total length 3 min), and an average fragment size of 200,500 bp was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Anti-H3K18la (PTM-1427RM; 2 mg) and anti-IgG (3900S; 2 mg) antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation. The precipitated DNA fragments containing the STEAP3 and HSD3B1 promoter were quantified by qPCR using the primers described in Supplementary Table 4.

DNA mutagenesis

H3K18R, H3K18T, and P300 R1368A mutations were generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA)63.

Transfection of siRNA and overexpression plasmid

SiRNAs were obtained from Sangon (China). The porcine granulosa cells were seeded onto 24-well plates, allowed to reach 30–50% confluence, and then transduced with siRNA using transfection reagents (RNAfit, HANBIO, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h post-transfection, cells were harvested for the measurement of mRNA expression levels. The sequences of siRNA are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Plasmids were prepared from GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Porcine granulosa cells were transfected with 3 μg plasmids with Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 h to fulfill overexpression of the specific genes.

Lentivirus transfection

To realize the stable expression of P300 knockdown, recombinant lentivirus expressing sh-P300 was prepared by Hanbio Tech (Shanghai, China). Porcine GCs at a confluence of 30–40% were transfection with lentivirus [10 multiplicities of infection (MOI), MOI = virus titer (TU/mL) × virus volume (mL)/cell number] for 24 h, and screened with 1 μg/mL puromycin (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) for one week and maintained in 0.4 μg/mL puromycin. After confirmation of expression with RT-qPCR and western blot, the sh-P300 cell line was used for subsequent experiments. The sequences of sh-P300 and sh-NC are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (v.8.4.3, La Jolla, CA, USA). The values were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normality was confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05 for all groups), and homogeneity of variances by the Brown–Forsythe test (p > 0.05). Differences between the two groups were assessed by an unpaired Student’s t-test. For experiments involving three or more groups, one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test were applied. Data were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05 (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.