Abstract

Plastic films are extensively utilized in agroecosystems, and their residues are accumulating in global soil at a worrying rate. Biodegradable films are employed as a substitute for polyethylene (PE) films due to their rapid degradation rate. Although the taxonomic diversity of soil microbiome in response to biodegradable films has been studied, its alterations in functional diversity remain unexplored. Here, we conduct a two–year field experiment in cherry tomato to address how PE and poly (butylene adipate–co–terephthalate) (PBAT) influences soil microbiota across multi–kingdom (bacteria, fungi, and protists) regarding its taxonomic and functional diversity. The results show that PBAT exposure reduces the taxonomic diversity while increasing functional diversity across multi–kingdom domains compared to PE exposure. We further find that the decreased taxonomic diversity under PBAT exposure reduces the complexity of microbial inter–kingdom and internal–kingdom networks. Conversely, PBAT exposure enhances microbial functional diversity (Shannon index) and average genome size, accompanied by elevated abundances of plastic–degrading genes as well as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur cycling functional genes. Overall, our study indicates that environmental filtration induced by PBAT exposure changes the microbial life adaptive strategies and leads to a decoupling between taxonomic diversity and functional diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

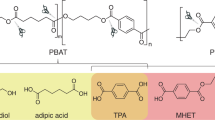

Polyethylene (PE) plastic films are widely used in agroecosystems. However, the incomplete recovery of plastic fragments, combined with inputs from atmospheric deposition and sewage sludge application, contributes to plastic pollution in farmlands1. Biodegradable films, composed of synthetic, petroleum-derived biodegradable polymers such as poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT), are an alternative material that will combat plastic pollution because they degrade gradually without releasing deleterious byproducts2. Still, biodegradable plastics may not degrade completely3, hence producing more microplastic (MP) fragments than conventional plastic films4. Therefore, it is necessary to quantify the potential consequences of biodegradable plastics in the soil ecosystem, especially on soil microbial community assembly and functioning.

Previous studies have shown that MP exposure, including biodegradable plastics, can alter soil microbial communities and assembly. Bacterial taxonomic diversity typically decreases under MP exposure, although the relative abundance of some specific bacteria, such as Lysobacter, Comamonadaceae, and Bacilli tends to increase due to their ability to degrade plastic-associated hydrocarbons via enzymes like esterases and lipases5,6. Similarly, fungal taxonomic diversity has also been reported to decline under plastic exposure7. This reduction is primarily attributed to the fact that fungal community assembly under environmental pressures such as MP exposure is mainly driven by stochastic processes, which limit the dispersal of fungal taxa. So far, some studies have explicitly focused on bacterial and/or fungal communities, paying limited attention to protists and their interaction. Hence, this narrow approach falls short of fully capturing the impacts of plastic exposure on microbial taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom soil microbiota. As major consumers of bacteria in soils, protists occupy an important position at the base of soil food webs8. They are also potentially important vehicles for delivering MP into the soil food chain. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of microbial taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom soil microbiota in response to plastic exposure is imperative.

Microorganisms are involved in the degradation processes of plastic, generally making them the first responders to environmental perturbation9,10. Microbial functional diversity and resilience under plastic exposure reflect changes in their biodegradation functions, representing microorganisms’ specific abilities to break down plastic. A compelling example of microorganisms biodegrading plastics through plastic-degrading functional genes is the bacterium “Ideonella sakaiensis”11. This powerful bacterium can secrete two key enzymes: polyethylene terephthalate hydrolase and mono (2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate hydrolase under polyethylene terephthalate (PET) exposure, which are regulated by the specific functional genes, namely PETase and MHETase genes, leading to enhanced PET degradation. On the other hand, functional diversity provides critical insights into the role microbes play in ecosystem processes, particularly in mediating key biogeochemical cycles12. This includes the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur (CNPS) through the expression of specific functional genes. Therefore, uncovering the mechanisms that link plastic exposure to microbial functional potential is essential for understanding the broader ecological consequences of plastic pollution in terrestrial environments13. Nonetheless, the link between microbial taxonomic and functional diversity, particularly across multi-kingdom soil microbiota, remains poorly documented.

In ecological communities, the relationship between microbial taxonomic and functional diversity plays a crucial role in shaping ecosystem resilience and functionality, often reflecting the intricate interplay between species richness and their ecological roles14. Although a positive correlation between microbial taxonomic and functional diversity is generally documented, these relationships can vary depending on environmental conditions and disturbance intensity, highlighting the dynamic nature of biodiversity in response to ecological stresses. The reason could be that specific taxonomic species have unique functional traits. Hence, greater taxonomic diversity under the conditions of species coexistence can promote higher functional diversity, thereby supporting stability in ecosystem functioning15. However, the relationship between microbial taxonomic and functional diversity may vary depending on the specific environmental stressor and the ecosystem being studied. For example, Wang et al. showed an inverse relationship between the taxonomic and functional diversity of the bacterial community, along a gradient of increasing pH16. Similarly, the decoupling between microbial functionality and taxonomy has also been demonstrated in a recent study by Fan et al.17. This discrepancy may be explained by functional redundancy, wherein multiple microbial taxa perform the same ecological function, resulting in a weak correlation between taxonomic composition and functional potential. In the context of the current study on PBAT exposure, it is proposed that PBAT can shift species composition by promoting the proliferation of new taxa with specific traits related to plastic biodegradation18. Such community shifts may further help preserve or even enhance functional diversity, even as taxonomic diversity declines, indicating a decoupling of functionality from taxonomy. Nevertheless, this speculation on PBAT exposure requires further verification through comprehensive studies.

Despite advancements in understanding environmental microbiome responses to MP exposure, a notable gap remains in generalizable insights into how microbial functional diversity corresponds to patterns in taxonomic diversity under biodegradable plastic exposure. Although some studies suggest that biodegradable plastics can selectively enrich microbial taxa capable of degrading polymer components, quantitative assessments of functional diversity and functional profiles remain limited, even as substantial changes in microbial taxonomic composition are widely reported. Hence, we hypothesized that if soil microbiota is exposed to biodegradable plastics, as compared to PE, it would reduce the taxonomic diversity, while enhancing functional diversity across multi-kingdom soil microbiota, leading to an inverse relationship between the two. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a two-year field experiment comparing the effects of conventional PE and biodegradable PBAT exposure on cherry tomatoes in a terrestrial ecosystem. This study investigates the impacts of different plastic exposures on taxonomic diversity, community assembly, and co-occurrence relationships across multi-kingdom soil microbiota (bacteria, fungi, and protists). Moreover, microbial functional diversity via metagenome shotgun sequencing and its association with taxonomic diversity via amplicon sequencing were assessed. This study would provide an insight into the ecological drivers impacting multi-kingdom microbiota under biodegradable plastic and conventional PE exposure.

Results

Taxonomic diversity and assembly across microbial kingdoms

We used amplicon sequencing to characterize the taxonomic diversity and composition of the multi-kingdom soil microbiota based on 156 soil DNA samples spanning four different compartment niches and three exposure concentrations. Our results revealed that compartment niches explained a higher variation (38–55%) compared to plastic types exposure (1–6%), through principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) ordinations and PERMANOVA analyses (Fig. 1a). The taxonomic diversity (alpha diversity) under PE exposure was significantly higher than PBAT (Fig. 1b; p < 0.05). In the plastisphere, compared to the PE exposure, bacterial, fungal, and protistan taxonomic diversity (Chao1 index) decreased 65%, 58%, and 45%, respectively, under PBAT exposure during the 2020 cropping season (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Unconstrained PCoA ordination based on the Bray–Curtis distance matrices of bacterial, fungal and protistan communities in response to exposure to different plastic types across different compartment niches (bulk soil: BR, rhizosphere: RS, root endosphere: Endo, and plastisphere: PS); b Alpha-diversity (Shannon and Chao1 index) of bacterial, fungal and protistan communities in response to different plastic types exposure (CK, PE, and PBAT) (n = 56 for bacteria and fungi; n = 52 for protists. CK treatment had no plastisphere samples). The top and bottom of the box represent the 75th and 25th quartiles, respectively, and the horizontal line within the box represents the median of each treatment. The asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001), while “ns” represents non-significant differences (p > 0.05) among different plastic types exposure (CK, PE, and PBAT) using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Taxonomic classification exhibited distinct differences in the composition of all kingdoms across various compartmental niches and plastic types exposure (Supplementary Fig. 3). The bacterial community predominantly comprised Alphaproteobacteria (52.6%), Acidobacteria (20.0%), and Actinobacteria (11.2%). For fungi, Sordariomycetes (59.1%) and Agaricomycetes (23.7%) were the dominant phyla, while Archaeplastida (56.8%) and Amoebozoa (22.3%) dominated the protistan community. Furthermore, in the plastisphere, the PBAT exposure significantly enriched Alphaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria by 31.4%, 88.6%, and 39.2%, respectively, in bacteria; increased Agaricomycetes by 90.6% in fungi; and elevated Metazoa by 72.3% in protists compared to PE exposure (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 1–3; p < 0.05).

The taxonomic diversity in phylogenetic diversity (pd index) was higher under PE than PBAT exposure regardless of four compartment niches, although a statistically significant difference was observed only for fungi (p < 0.0001), and not for bacteria and protists (Fig. 2a). This different was particularly pronounced in the plastisphere, where the pd index was 50% higher for bacteria, 56% higher for fungi, and 42% higher for protists under PE exposure compared to PBAT (Supplementary Fig. 4). Several specific amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (such as bacterial ASV19757, fungal ASV9, and protistan ASV1) that responded to the application of different plastic types exposure were selected at different compartmental niches using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5). The phylogenetic relationships of these specific ASVs of bacteria, fungi, and protists were constructed (Fig. 2c).

a Phylogenetic diversity of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities in response to plastic types exposure (n = 56 for bacteria and fungi; n = 52 for protists. CK treatment had no plastisphere samples). The top and bottom of the box represent the 75th and 25th quartiles, respectively, and the horizontal line within the box represents the median of each treatment. The asterisks indicate significant differences (****p < 0.0001), while “ns” represents non-significant differences (p > 0.05) among different treatments using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. b Specific bacterial, fungal, and protistan species in response to different plastic types exposure using the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe). Datasets were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test (P < 0.05) to determine the differential specific species that were ranked according to the LDA score (log 10). c Cladogram illustrating phylogenetic relationships of specific species of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities. Multilayer rings, from the inner to the outside layer, represent: (inner ring) phylum level taxonomy; (ring 1) plastic types categories based on LEfSe of specific ASVs, (ring 2–4) relative abundance of specific ASVs in response to different plastic types exposure.

Community-level habitat niche breadths and the neutral community model were employed to uncover the mechanisms driving microbial community assembly. Lower mean Bcom (Habitat niche breadths) values were observed in the bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities under PBAT exposure than PE exposure across most compartment niches (Supplementary Fig. 6). It suggested that microorganisms under PBAT exposure were subject to more environmental filtering. The neutral community model further indicated that the assembly process of microbial communities across compartment niches was dominated by deterministic process under PBAT compared to PE exposure (Fig. 3). Given the higher contribution of deterministic processes and lower value in mean Bcom for microbiome communities under PBAT exposure, it can be inferred that environmental filtering, like exposure to PBAT, plays a dominant role in deterministically shaping microbiome communities’ composition.

CK treatment had no plastisphere samples). Each point represents a microbial ASV, and different colors indicate ASVs that occur more or less frequently than predicted by the neutral model. The predicted occurrence frequency is shown as a solid blue line, and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval around the neutral model. The R2 indicates the fit to the neutral model.

Inter- and intra-kingdom co-occurrence networks and topological characteristics

We further constructed inter- and intra-kingdom co-occurrence networks of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities to graphically visualize the potential relationships and illustrate their vulnerability and resilience to different plastic types (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 7). We found that a larger number of specific bacterial ASVs in response to PBAT, identified by the LEfSe, was also reflected in the bacterial co-occurrence network. For example, PBAT exposure revealed a higher proportion of specific ASV, nearly 25% compared to 6.3% under PE exposure (Fig. 4a).

a Internal-kingdom co-occurrence networks showing distribution patterns of the specific ASVs. Differently colored specific bacterial, fungal, and protistan species indicate their responsive plastic-type exposure, and the grey-coloured ASVs represent the non-specific species. b Comparison of topological characteristics of internal-kingdom network response to different plastic types exposure. c Natural connectivity response to different plastic types exposure, measured by the proportion of taxa remaining after the random removal of 50%. d Network vulnerability response to different plastic types exposure, measured by maximum node vulnerability (n = 56 for bacteria and fungi; n = 52 for protists. CK treatment had no plastisphere samples).

The associated topological characteristics of inter- and intra-kingdom co-occurrence networks for bacteria, fungi, and protists, such as nodes, average connectivity, density, transitivity, and degree centralization, were higher under PE compared to PBAT exposure (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). We further simulated the taxonomic extinction and calculated robustness (the resistance to node loss) of the inter-kingdom co-occurrence network. Based on either random species loss or targeted removal of module hubs in the inter-kingdom co-occurrence network, PE exposure showed higher robustness than that under control (CK) and PBAT exposure (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Moreover, while simulating the natural connectivity and vulnerability of microbiota networks, we found that the complexity and stability of the internal-kingdom co-occurrence network were greatly lower under PBAT than PE exposure (Fig. 4c, d). Meanwhile, some specific bacterial ASVs with biodegradable functions in response to PBAT exposure were also highlighted in the co-occurrence network.

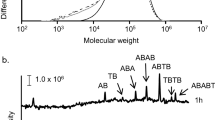

Functional profiles of microbiota under different plastic types

Functional predictions based on amplicon sequencing (using the FAPROTAX database) and metagenomic sequencing of 18 representative samples across three plastisphere types and two experimental years, were applied to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the functional potential of soil microbiota. Firstly, amplicon sequencing showed that the relative abundance of the metabolic and functional profiles of PBAT exposure was significantly higher than PE exposure and CK in most compartment niches, especially in those involved in N cycling, like nitrification, nitrate respiration, and nitrate reduction (Supplementary Fig. 10; p < 0.05). Furthermore, metagenomic analysis was conducted to profile the microbiome’s functional genes. It revealed that the functional gene diversity (Shannon index in term of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and carbohydrate-active enzyme gene repertoire (CAZyome)) was significantly higher under the PBAT exposure than PE and CK (Fig. 5a; p < 0.05). Different microbiome functional genes (KEGG orthologs (KO), CAZyome, and cluster of orthologous groups (COG)) of PE, PBAT, and CK treatments were clustered and distinctly separated from each other (R2 = 0.31*−0.45**; Fig. 5b). In addition, the average genome size was greatly higher under PBAT treatment, showing an 18.9% increase compared to the PE treatment. This implied that PBAT exposure may promote higher functional diversity within microbial communities, potentially by enriching specific taxa with larger, more functionally versatile genomes (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a Functional diversity (Shannon index) of KO, CAZyome, and COG. The top and bottom of the box represent the 75th and 25th quartiles, respectively, and the horizontal line within the box represents the median of each treatment. The asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001), while “ns” represents non-significant differences (p > 0.05) among different plastic types exposure (CK, PE, and PBAT) using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. b Unconstrained PCoA ordinations based on the Bray–Curtis distance matrices of KO, CAZyome, and COG functional genes. c Identification of functional genes in the KEGG database involved in C cycling functions using the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) in response to different plastic types exposure. Datasets were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis test (P < 0.05) to determine the differential functional genes that were ranked according to the LDA score (log 10). d Abundances (count number) of 6 functional genes involved in C cycling functions in response to different plastic types exposure. e Accumulative abundance (count number) of all functional genes involved in Xenobiotics Biodegradation and Metabolism pathways in response to different plastic types exposure. f Abundance (count number) of 3 specific functional genes involved in Xenobiotics Biodegradation and Metabolism in response to different plastic types exposure. Error bars represent mean ± standard error (SE), with each data point indicating an individual sample library (n = 6).

Several functional genes related to C cycling that responded to the plastic types exposure were selected using LDA effect size (LEfSe) (Fig. 5c). The results revealed that most of the selected C cycling-related genes, such as genes maeB, fdwA, suc, sdhD, ppc, and edd, had the highest abundance under PBAT exposure compared to PE and CK, as shown in Fig. 4d. The accumulated abundance (count number) of C-cycling functional genes (Supplementary Fig. 12a), P-cycling functional genes (Supplementary Fig. 12c), and S-cycling functional genes (Supplementary Fig. 12e), were significantly higher under PBAT exposure than PE and CK (p < 0.05). Notably, the abundance of functional genes ppc (C), soxB (S), and gspH (P) under PBAT exposure was greatly higher than PE and CK (Supplementary Fig. 12b, d, f). Concerning plastic-degrading functional genes, the accumulated abundance of all these genes was significantly higher under PBAT than PE exposure and CK, as shown in Fig. 5e (p < 0.001). In particular, the abundance of genes tfdB, pcaG, and Ad under PBAT exposure increased by 18%, 11%, and 39%, respectively, compared to PE (Fig. 5f).

In total, 27 functional genes involved in N cycling were exclusively retrieved, including those participating in N fixation, nitrification, denitrification, assimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (ANRA) and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) (Fig. 6a). Compared to CK, PBAT exposure increased the abundances of functional genes involved in DNRA and partial denitrification, while PE exposure induced a decrease in functional gene abundances participating in most N cycling processes (Fig. 6a). Comparing the gene abundances under PE with PBAT, we found that PBAT exposure induced higher average abundances of nifH/K genes encoding for N fixation, norC genes for denitrification, nasA genes for ANRA, and napA/B genes for DNRA (Fig. 6a). The microbial community involved in N cycling was mainly dominated by Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria (Supplementary Fig. 13), and they were also the major phyla driving the processes of N fixation, nitrification, denitrification, DNRA and ANRA under PBAT exposure (Supplementary Fig. 14). For individual N cycling process, the enhanced N fixation processes under PBAT exposure relative to CK were mainly driven by Methylocystis and Pseudacidovorax. While the DNRA and ANRA processes under PBAT exposure, relative to CK treatment, were mainly driven by Rhizobium, Tardiphaga, and Lysobacter (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Data). Interestingly, Pearson’s correlation suggested a significant relationship between functional diversity (Shannon index based on KO, CAZyome, and COG) and taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom domains (Supplementary Fig. 15; p < 0.05).

The variation of nitrogen cycling processes regulated by a functional gene and b microbial genera between PE vs. CK, PBAT vs. CK, and PBAT vs. PE. Orange and blue lines indicate that the functional genes are increased and decreased by the former treatment, respectively. The dotted line indicates that the functional genes are not detected. The number in the parentheses represents the fold change value between the two comparative treatments.

The relationship of multi-kingdom soil microbiota with soil environmental factors

Several soil environmental factors, such as dissolved organic carbon (DOC), available nitrogen (AN), available phosphorus (AP), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP), microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), and pH were significantly affected by exposure to plastic types (Table S4; p < 0.05). In general, the AN and AP were both decreased while the MBC, MBP, and MBN were enhanced under PBAT exposure compared to CK (Table S4). For example, the AN and AP decreased by 46% and 26%, respectively, under PBAT exposure; while MBC, MBP, and MBN increased by 71%, 32%, and 40%, respectively, under PBAT exposure in comparison with CK in 2022 (Table S4). Soil enzymes such as β-D-Glucosidase (BG), cathepsin (CB), and GTPase-activating protein (GAP) were also significantly influenced by exposure to plastic types (p < 0.05). For instance, BG, CB, and GAP were increased by 46%, 26%, and 44%, respectively, under PBAT exposure in comparison with CK in 2021, and by 23%, 9%, and 26% in 2022 (Table S5). Furthermore, an RDA revealed that different plastic types’ exposures were clustered and distinctly separated from each other. The PBAT exposure consistently showed a positive effect on BG and CB ordination across multi-kingdom domains during both experimental years, implying that PBAT exposure improves soil BG and CB (Supplementary Fig. 16). It was further observed that the soil chemical properties, such as pH, DOC, MBN, AN, AP, and MBC, and soil enzyme parameters were the most important contributors to multi-kingdom soil microbiota (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Discussion

The taxonomic diversity of microorganisms plays a crucial role in resisting the environmental disturbances caused by PE and PBAT exposure, thereby stabilizing an ecosystem19. Our study evidenced decreases in both taxonomic and evolutionary diversities of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities under PBAT, compared to PE exposure. Various factors may explain these results. Firstly, it could be caused by the selective pressure exerted by PBAT exposure, which may favour specific microorganisms more compatible with plastic exposure13. Our results reinforce this concept, as both the neutral community model and Bcom revealed that the environmental filtering induced by PBAT exposure influenced the microbial community assembly, especially in the deterministic process20. Secondly, it could be explained by the hydrophilicity of PBAT, allowing ester bond cleavage during hydrolysis to form water-soluble low molecular weight oligomers, which are then used by some specific microorganisms as an additional carbon source. Hence, these microorganisms can outcompete others that metabolize plastic-derived carbon slowly or not at all21,22. For example, ASV19757 in the bacterial community was identified as Bacillus subtilis, a species known to degrade PBAT plastic23. In addition, ASV17, ASV75, and ASV1365 from the family Xanthomonadaceae have been previously reported to be involved in the biodegradation of polylactic acid and pentachlorophenol, highlighting their potential role in the PBAT degradation24,25.

The decreased microbial taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom domains could negatively influence the complexity of microbial inter- and intra-kingdom networks26. Our results also confirm the assertion by revealing that PBAT exposure reduced the complexity and stability of microbial networks compared to PE exposure, as presented by lower robustness, nodes, links, and higher vulnerability of inter- and intra-kingdom co-occurrence networks. Previous studies have also shown that the decreasing microbial taxonomic diversity reduces the potential microbial connections and interactions27. PE exposure reflects greater network complexity and stability by adsorbing nonpolar organic matter and various soil microorganisms due to their high hydrophobicity28. Similarly, Sun et al. also suggested that the co-occurrence network of the PE plastisphere exhibited greater network complexity and stronger stability than those in the polylactic acid plastisphere29. Our findings indicated that PBAT exposure could decrease connectivity and complexity of co-occurrence networks across multi-kingdom domains, due to reduced microbial taxonomic diversity.

The enhanced functional diversity under PBAT exposure was supported by metagenomic data, as evidenced by increases in both functional gene diversity (Shannon index; Fig. 5a) and average genome size (Supplementary Fig. 11). Higher average genome size is often associated with greater microbial functional diversity, reflecting increased metabolic versatility and ecological adaptability in response to environmental stressors such as PBAT16,30. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the observed increase in microbial functional diversity was accompanied by an elevated abundance of plastic-degrading functional genes. These included genes involved in xylene degradation, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation, and chloroalkane and chloroalkene degradation, as well as CNPS functional genes associated with key biogeochemical cycles. However, this increase in functional diversity was associated with decreased microbial taxonomic diversity and a more fragile co-occurrence network, as mentioned above. Plastic-degrading functional genes can encode enzymes with specific catalytic sites that break down the chemical bonds within a plastic polymer into smaller components like monomers or oligomers31,32. Notably, this study also evidenced three important plastic-degrading enzymes, i.e., 2,4-dichlorophenol 6-monooxygenase, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase dioxygenase and 1,2-dioxygenase, which were respectively encoded by the tfdB, pcaG, and Ad genes, that were enriched under PBAT exposure in comparison to PE. The enzyme 2,4-dichlorophenol 6-monooxygenase is a hydroxylase involved in the degradation of chlorinated aromatic pollutants, produced by the pyrolysis of polymer and plastic additives33. While protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase and 1,2-dioxygenase is linked to the degradation of styrene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon28,34. Additionally, our study also confirmed higher enzymatic activities of soil β-glucosidase, cellulase, and GAP under PBAT exposure compared to PE. Such an enhancement of enzymatic activities can be attributed to favourable soil conditions, such as optimal soil moisture, a balanced pH level, adequate organic matter, suitable temperature, and a diverse microbial community, all of which may be triggered by the biodegradation of PBAT within the soil35.

Except for plastic-degrading functional genes, CNPS functional genes were enriched under PBAT exposure than PE, through 16S RNA functional forecast and metagenomes analysis. For example, PBAT exposure increased most N-cycling genes related to N assimilation and denitrification, such as nifH and napA/B. A higher C: N ratio following PBAT degradation was the primary driver of higher N assimilation and denitrification. This elevated the microorganisms’ demand for ammonium and N sources, which were assimilated into biomass to support growth. The “electron shuttling” hypothesis proposed by Rillig et al. also suggests that the increase in carbon source supply accelerates the N transformations in the biodegradable plastisphere of PBAT, rather than of nonbiodegradable PE36. This speculation is consistent with our findings that PBAT exposure increases MBC, MBN, and MBP while decreasing the available N (nitrate and ammonium) and available P in the soil compared to PE exposure. It is logical to infer that in a high C: N ratio after PBAT biodegradation, where C is abundant but other nutrients, like N, P, and S, are limited, the variations in C-cycling genes can shift the microbial community structure, in favour of some specific microorganisms with enhanced C utilization strategies. This strategy of prioritizing C utilization can also enable higher microbial activity and more efficient immobilization of other nutrients, which play a major role in the overall nutrient cycling dynamics, like N, P, and S supply. Overall, it could be inferred that the enrichment of CNPS functional genes under PBAT exposure plays a central role in sustainable agriculture development by altering soil nutrient supply37,38.

Taxonomic diversity refers to the range of different kinds of microorganisms present in a given environment, categorized by their taxonomic classification, including phylum, class, genus, and species. In contrast, functional diversity represents the range of metabolic activities or functions these species can perform, such as C-cycling or contaminant degradation14,15. A positive correlation between taxonomic and functional diversity often exists as species with different evolutionary histories, represented by a higher taxonomic diversity, tend to have evolved different functional traits. This suggests that a wider range of species, as indicated by a higher taxonomic diversity, usually leads to a higher functional diversity as well19,27.

Although often positively correlated, the relationship between taxonomic and functional diversity can be complex, with situations where a diverse array of species does not necessarily guarantee a high level of functional diversity. In some cases, a community with a high taxonomic diversity may have many species performing similar functions, leading to lower functional diversity depending on the environment and specific microbial community involved. Previous studies have indicated that environmental conditions such as pH, aridity, salinity, and heavy metals can influence the translation and linkage between taxonomic diversity to functional diversity14. For example, a change in pH may increase taxonomic diversity but decrease functional diversity if the new species primarily perform similar functions16. The current study also suggests that functional diversity does not necessarily correlate with taxonomic diversity. This discrepancy can be explained by the PBAT degradation process, which requires microorganisms to have a greater abundance of functional genes (such as plastic-degrading and CNPS functional genes often retained by a few microbes). These genes enable them to perform degradation functions and cope with the environmental stress caused by PBAT exposure. In contrast, such an adaptive strategy is not required under PE exposure, as PE is not biodegradable, and most functional genes remain inactive and can’t support microbial growth.

Our study highlights that environmental filtration induced by PBAT exposure changes the adaptive strategies of microbes. It also enables the decoupling of taxonomic diversity from functional diversity. In this context, it can be inferred that functional diversity is crucial as it directly impacts ecosystem functioning, particularly degradation processes, making it a key indicator of overall ecosystem health. Conversely, microbial taxonomic diversity cannot predict the ecosystem functionality. Hence, our study underscores the central role of microbial functional diversity in ecosystems. Our findings provide an insight into the community assembly processes and ecosystem functions, while also strengthening our understanding of the relationship between microbial taxonomic and functional diversity.

The degradation rate of PBAT under field conditions ranges from partial to substantial but remains highly context dependent. Recent studies have reported approximately 20–60% biodegradation of PBAT composite mulch films within six months under soil conditions39,40,41. In our own field experiments, we also confirmed that PBAT mulch films gradually degraded during the crop growth cycle; however, noticeable residues persisted at harvest and continued to diminish over time. These residues, together with their progressive fragmentation into microplastics, can directly and continuously influence the microbial taxonomic and functional diversity that was a central focus of our study39. Considering both the persistence of mulch residues and the dynamic processes of their breakdown into microplastics, further research is required to emphasize the importance of long-term monitoring across diverse field environments in order to better elucidate their ecological interactions and underlying mechanisms31.

In summary, our study revealed that PBAT exposure reduced the taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom domains while increasing functional diversity (Shannon index based on KO, COG, and CAZy) compared to PE exposure. The decreased taxonomic diversity was primarily attributed to selective pressure and hydrophilicity exerted by PBAT exposure. Additionally, we found that the complexity of microbial inter- and intra-kingdom networks decreased alongside the reduced taxonomic diversity under PBAT exposure. Moreover, despite the decrease in microbial taxonomic diversity, the abundance of plastic-degrading and CNPS functional genes was increased under PBAT exposure. Our study further concludes that environmental filtration induced by PBAT exposure changes microbial life adaptive strategies and leads to the decoupling of taxonomic diversity and functional diversity. This suggests that even with reduced taxonomic richness, microbial communities may retain or even enhance functional potential under specific environmental pressures. Given the central role of microbial functional diversity in regulating ecosystem processes, we hope our findings stimulate further research into the mechanisms driving this decoupling. In particular, exploring strategies such as developing synthetic microbial communities could offer valuable insights into optimizing microbial functions42. Such efforts will deepen our understanding of microbial community assembly and the functional dynamics that underpin ecosystem resilience.

Methods

Field preparation and experimental design

Field experiments on cherry tomato were performed at the Ledong Experimental Station of Hainan University (109°17′0″E, 18°74′0″N), Hainan Province, China, over two cropping seasons, from 2020 to 2022. During both seasons, one-month-old cherry tomato seedlings were manually transplanted at a depth of approximately 10 cm into well-prepared field beds with rows spaced 100 cm apart in October and harvested in April of the following year. Then the field was left fallow until October the same year. The experimental site has a tropical monsoon climate. From 2020 to 2022, the annual average precipitation was 1786 mm and the mean air temperature was 23.8 °C. The experimental field had laterite soil. In 2020, the topsoil (0–20 cm) contained 17.14 g kg−1 of soil organic matter, 0.75 g kg−1 of total N, 5.67 g kg−1 of total P, 11.71 mg kg−1 of available N, and 48.95 mg kg−1 of available P. The soil pH was 6.04.

The treatments comprised two plastic types (PE and PBAT) and three exposure concentrations (0, 800, and 4000 kg ha−1) under plastic film mulching conditions. The selection of these two plastic types was based on their widespread applications, distinct physicochemical properties, and contrasting degradability profiles. It allowed us to explore the differential effects of conventional versus biodegradable plastics on soil microbial communities and their functional potential. At the start of each cropping season, residue fragments specific to the corresponding treatments were manually applied to the soil surface before tillage and subsequently incorporated into the soil during the tillage process. The three plastic exposure concentrations were selected to represent the realistic doses of the current “ambient exposure”, “moderate exposure”, and “maximum exposure” in some Chinese farmlands under film-covered field conditions43. Additionally, plots without plastic exposure and plastic film mulching were kept as the control in the field experiment. The treatments were arranged according to a randomized complete block design with four replications (Supplementary Fig. 1). The field was tilled one week before mulching, at which time a basal dose of N (300 kg N ha−1), P (750 kg P ha−1), and K (375 kg K ha−1) fertilisers were spread over the topsoil, based on soil test recommendations. This was followed by the weighing and spreading of the PE and PBAT residue fragments on the soil surface. The PE and PBAT residues were manually incorporated into the topsoil layer (0–30 cm) within each designated treatment plot to ensure a spatial distribution at the plot scale. The PE and PBAT residue fragments were obtained by cutting the plastic film into small pieces (4 × 5 cm) using scissors. After the PE and PBAT residual debris were incorporated into the topsoil, ridges and furrows were formed artificially with a width of 55 cm. Then, the alternate ridges were mulched using the PE and PBAT films.

Sample collection and soil chemical properties

In both cropping seasons, soil samples were collected from the topsoil (0–25 cm) across four different compartment niches (bulk soil, rhizosphere, root endosphere, and plastisphere) were collected at the cherry tomato maturity stage for all the plots in 2021 and 2022. Bulk soil samples were collected from the topsoil between two rows using a stainless-steel auger with a 3 cm diameter. Five representative subsamples of bulk soil were thoroughly mixed, passed through a 2 mm steel mesh, and combined as a one sample for each plot. The sampling approach aligns with the scale of microplastic incorporation, ensuring that the samples accurately reflect the treatment effects. Rhizosphere compartments that were tightly attached to the fine roots were also sampled for each plot according to Fu et al.44. To collect the root endosphere sample, the roots were surface-sterilized for 1 min in 80% ethanol and subsequently sterilized again for 1 min in 0.25% NaClO, then thoroughly ground under liquid nitrogen. For the plastisphere samples, the plastic residues were collected artificially from the topsoil, and the soil tightly bound to the film surface was extracted by immersing it in a sterile saline solution. Although PBAT is classified as biodegradable, our field observations indicated that a substantial portion of the PBAT residues had not fully degraded, allowing for plastisphere sample collection. The resulting soil suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the pellet was defined as plastisphere soil. All samples were immediately sealed in sterile polyethylene bags and transported to the laboratory within 6 h in a portable refrigerator containing ice. The bulk soil was partitioned into two parts. One subsample was stored at 4 °C to measure soil chemical properties. Another subsample and the plastisphere samples were stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction. Only the bulk soil samples were used for soil chemical property measurements. A total of 156 soil samples for bacteria and fungi, 144 soil samples for protists (root endosphere samples were not collected in 2021) were taken and stored at −80 °C before DNA extraction (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Prior to the determination of soil chemical properties, soil moisture was measured using the oven-drying method. Soil pH was determined after shaking the suspension for 1 h using a digital pH meter (STEH-200N, Shanghai, China). AN (NH4+ and NO3−) was extracted with 1 M KCl solution, and concentrations in the extract was quantified using a standard colourimetric procedure with an automatic discrete analyser (DeChem-Tech, Hamburg, Germany). Available P was determined using the sodium bicarbonate extraction method. DOC (mg kg−1) was extracted using the same solution as inorganic C and analysed using a total organic carbon analyser (TOC-L CPH, Shimadzu Corp., Japan). MBC, MBN, and MBP were determined by the chloroform fumigation-extraction method45.

Soil enzyme activities, i.e., BG, CB, and GAP, were determined following the methods described by Nannipieriet et al.46 and Chen et al.47. Prior to enzyme measurement, soil moisture was recorded using the oven-drying method. Each sample was prepared in twelve replicates and incubated at 25 °C. Fluorescence measurements were conducted with an enzyme-labelling device (SpectraMaxi3×, Salzburg, Austria) with excitation at 365 nm for BG and CB, and 410 nm for GAP. The activity of soil extracellular enzymes was calculated on the basis of soil dry weight and reaction time, and expressed as nmol·g−1·dry·soil·h−1.

DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

Total soil genomic DNA was extracted from 0.5 × g of fresh soil using FastDNATM SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −20 °C before further analysis. The quality of the DNA was checked on a 1% agarose gel, and the DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar concentration and sequenced using paired-end reads on an Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the standard protocols. The hypervariable region V3–V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified with primer pairs 338 F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), and fungal ITS1-2 region was amplifed using primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS2 (5′- GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC -3′), and 18S V9 hypervariable region of eukaryotes was amplifed using primers TAReuk454FWD1 (5′- CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC-3′) and TAReukREV3 (5′- ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRA -3′), using an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 PCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems ABI 9700, CA, USA). The PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 27 denaturation cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 45 s, single extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and ending at 4 °C. The PCR mixtures contain 5 × TransStart FastPfu buffer 4 μL, 2.5 mM dNTPs 2 μL, forward primer (5 μM) 0.8 μL, reverse primer (5 μM) 0.8 μL, TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase 0.4 μL, template DNA 10 ng, and finally dd H2O up to 20 μL. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. The PCR product was extracted from a 2% agarose gel, purified using AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and quantified using a Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar and paired-end sequences on an Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). All samples (mentioned in Supplementary Fig. 1) were subjected to amplicon sequencing to provide a comprehensive assessment of microbial community structure across different compartment niches, treatments, and years.

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw sequencing reads were pre-quality filtered and trimmed using fastp version 0.20.048 and merged using FLASH49. Sequences were processed using USEARCH 10.0 software and VSEARCH 2.14 software50,51 and ASVs were identified using the DADA2 algorithm52. Bacterial, fungal, and protistan taxonomic assignments were performed using SILVA (v13.8), UNITE (v8.0), and PR2 (v4.12.0) reference databases, respectively. A total of 6,978,036 bacterial, 7,422,989 fungal, and 20,371,565 protists high-quality reads were retrieved and sorted into 14474 bacterial, 2443 fungal, and 9728 protistan ASVs.

Metagenomic sequencing and data mining

Only a subset of 18 representative samples (3 plastisphere types: PE, PBAT, and CK × 2 years × 3 replicates) was selected for metagenomic sequencing, enabling detailed functional and taxonomic profiling using the Illumina NovaSeq platform with paired-end protocols. This subset was chosen to enable detailed functional and taxonomic profiling while balancing the constraints of sequencing cost and computational feasibility. Sequencing libraries were generated using ALFA-SEQ DNA Library Prep Kit, and the library quality was assessed using the Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and Qsep400 High-Throughput Nucleic Acid Protein Analysis (Guangdong Magigene Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) system. Raw sequences were quality-filtered using Trimmomatic (v0.39)53. Finally, an average of 2 Gb of clean data was retrieved for each sample. These quality-controlled high-quality reads were subjected to de novo assembly by using MEGAHIT (K-mer: k-min 35, k-max 95, and k-step 20) (v1.2.9)54. Scaftigs with contig lengths above 500 bp were screened for subsequent analysis. DIAMOND software was used to blast the Unigenes against the sequences of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses, which were all extracted from the NR database of NCBI. The functional profiles of microbiomes were characterized based on KEGG Orthology (KO), Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme (CAZyome), and Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG). For each sequence’s blast result, the best Blast Hit was used for subsequent analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

In both cropping seasons, a total of 156 soil samples were collected from the topsoil (0–25 cm) under four compartment niches (bulk soil, rhizosphere, root endosphere, and plastisphere) and three exposure concentrations (0, 800, and 4000 kg ha−1) at the cherry tomato maturity stage (Supplementary Fig. 1). All 156 soil samples were used for DNA extraction and stored at −80 °C. These DNA samples were subjected to amplicon sequencing for bacteria and fungi; while 144 samples were used for protist sequencing (root endosphere samples were not included in 2021). A subset of 18 representative samples (three plastisphere types: PE, PBAT, and CK × 2 years × 3 replicates) was selected for metagenomic sequencing.

Alpha-diversity was calculated using the “diversity”, “estimate”, and “pd” function in “vegan” package and “picante” package of R55. Habitat niche breadths were calculated using the “niche.width” function in “spaa” package56. Taxonomic differences, soil chemical properties, soil enzyme, functional genes, and habitat niche breadths of different treatments were tested using Tukey’s posthoc test at 95% confidence interval using the “HSD.test” function in agricolae package of R57. All other comparisons were examined in Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, using the “stat_compare_means” function in “ggplot2” package of R58. Relationships between taxonomic diversity (Shannon index) and functional diversity (Shannon index) were tested by Pearson’s correlation analysis, using geom_smooth function in the “ggplot2” package of R. The beta-diversity was ordinated in weighted Bray–Curtis distance matrices using PCoA, and then plotted in the phyloseq package of R for bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, separately59. The significant differences among various influencing factors affecting the dissimilarity of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities were tested with PERMANOVA using “adonis2” function of the R package “vegan”55. The N cycling-related genes and microbial taxa between two treatments (PE vs. CK, PBAT vs. CK, PBAT vs. PE) were assessed by >twofold increase in relative abundance. Redundancy analysis (RDA) and rank of environmental factors importance were conducted to determine the influence of soil chemical properties on bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, using the R package “vegan”55. Average genome size was calculated based on metagenomic data following the method of Wang et al.16. In brief, it was evaluated by using MicrobeCensus pipeline that assesses the genome size based on the sequence coverage of 30 core single-copy genes, which were found to be universally present in bacteria and archaea.

FAPROTAX (Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa) and FUNGuild using “trans_func” function of the R package “microeco”, were used to predict the metabolic and functional profiles of bacterial and fungal communities in response to the plastic types exposure under different compartment niches from the 16S and ITS rDNA data60. LDA effect size (LEfSe) analysis was performed using the R package “microeco” to identify specific microorganisms across plastic type in four compartment niches, as well as functional genes in KO database involved in C cycling60. The functional genes were ranked according to the Kruskal–Wallis test (P < 0.05). Phylogenetic relationships of specific microorganisms were constructed to form a phylogenetic tree (as a cladogram) by a maximum likelihood approach in the IQ-TREE method61. Phylogenetic trees were visualized using an online open-source tool (Interactive Tree of Life, version 4.4.2)62.

A neutral community model was constructed to evaluate the assembly mechanisms, specifically the stochastic processes for bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, separately. The method for running a neutral community model has been previously described by Sloan et al.63. The assembly mechanism of the microbial community was based on three assumptions: (1) the ASVs were selected randomly from a common pool; (2) the death rate of the microbial community was equivalent to the growth rate; and (3) the dispersal efficiency of ASVs was comparable for different compartment niches. Thus, this model assumed that variations in microbial communities mainly resulted from the stochastic processes (ecological drift), and that relative abundance can be used to predict their ASV frequency.

Co-occurrence networks of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities were constructed based on spearman rank correlation scores (Spearman’s r > 0.7 or r < −0.7; P < 0.001) for all ASVs. The networks were visualised by the layout of Fruchterman–Reingold with 104 permutations in the R package “igraph”64 and Gephi software. Network topological characteristics, consisting of the number of nodes, average connectivity, number of modules, clustering coefficient, degree, and closeness centrality, were calculated using an “igraph”64. These topological characteristics were used to quantify the connectivity and complexity of co-occurrence networks64. Robustness was assessed by measuring the proportion of remaining species in this network after the removal of the random or targeted node. Natural connectivity was used to test the resistance or stability of the network in natural connectivity due to node or edge removal. The vulnerability of each node measures the relative contribution of the node to the global efficiency. Robustness, natural connectivity, and vulnerability of the network were calculated by the function “Robustness.Random.removal”, “natural.con.microp” “Vulnerability.micro” and in “gClusterNet” package65. It should be noted that the multi-kingdom co-occurrence networks presented here reflect correlation-based patterns rather than quantitative or causal relationships between microbial taxa66. Nevertheless, multi-kingdom co-occurrence networks that integrate microbial taxa from bacteria, fungi, and protists have been increasingly applied to investigate potential microbial interactions, such as mutualism, competition, and shared environmental preferences within complex ecosystems66,67.

In order to clarify the influence of different plastic types’ exposure on the targeted parameters, the treatments with PE exposure were combined for data analysis and represented by the abbreviation “PE” (regardless of various PE concentrations). Likewise, treatments with PBAT exposure (regardless of various PBAT concentrations) were combined and represented by the abbreviation “PBAT”, while treatment without plastic exposure was represented by the abbreviation “CK”.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw sequence data reported in this paper were submitted to the Genome Sequence Read Archive in the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation (GSA number, CRA021378). 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data are available under Runs CRR1423449–CRR1423604 (Experiments CRX1306952–CRX1307107). ITS amplicon sequencing data are available under Runs CRR1423605–CRR1423760 (Experiments CRX1307108–CRX1307263). 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing data are available under Runs CRR1423761–CRR1423904 (Experiments CRX1307264–CRX1307407). Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data are available under Runs CRR1424433–CRR1424450 (Experiments CRX1307884–CRX1307901). Source data for graphs and charts presented in the study can be found at Figshare depository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29974594.v2)68.

Code availability

The command line code of R software for the bioinformatics processing in this study was deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/chenyunshu0817/LD_plastic–residue) and Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17364310)69.

References

Sa’adu, I. & Farsang, A. Plastic contamination in agricultural soils: a review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 35, 13 (2023).

Agostinho, B., Silvestre, A. J., Coutinho, J. A. & Sousa, A. F. Synthetic (bio)degradable polymers–when does recycling fail?. Green. Chem. 25, 13–31 (2023).

Albright, V. C. III & Chai, Y. Knowledge gaps in polymer biodegradation research. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 11476–11488 (2021).

Qin, M. et al. A review of biodegradable plastics to biodegradable microplastics: another ecological threat to soil environments?. J. Clean. Prod. 312, 127816 (2021).

Joos, L. & De Tender, C. Soil under stress: the importance of soil life and how it is influenced by (micro)plastic pollution. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 1554–1566 (2022).

Salam, M. et al. Effects of micro (nano)plastics on soil nutrient cycling: state of the knowledge. J. Environ. Manag. 344, 118437 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Terrestrial plastisphere as unique niches for fungal communities. Commun. Earth. Environ. 5, 483 (2024).

Rillig, M. C. & Bonkowski, M. Microplastic and soil protists: a call for research. Environ. Pollut. 241, 1128–1131 (2018).

MacLean, J. et al. The terrestrial plastisphere: diversity and polymer-colonizing potential of plastic-associated microbial communities in soil. Microorganisms 9, 1876 (2021).

Arif, Y., Mir, A. R., Zieliński, P., Hayat, S. & Bajguz, A. Microplastics and nanoplastics: source, behavior, remediation, and multi-level environmental impact. J. Environ. Manag. 356, 120618 (2024).

Shosuke, Y. et al. A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly (ethylene terephthalate). Science 351, 1196–1199 (2016).

Hu, X. et al. Distinct influence of conventional and biodegradable microplastics on microbe-driving nitrogen cycling processes in soils and plastispheres as evaluated by metagenomic analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 451, 131097 (2023).

Song, T. et al. Effect of conventional and biodegradable microplastics on the soil-soybean system: a perspective on rhizosphere microbial community and soil element cycling. Environ. Int. 190, 108781 (2024).

Ruhl, I. A. et al. Microbial functional diversity correlates with species diversity along a temperature gradient. Msystems 7, e00991–21 (2022).

Barabás, G., Parent, C., Kraemer, A., Perre, F. V. & De Laender, F. The evolution of trait variance creates a tension between species diversity and functional diversity. Nat. Commun. 13, 2521 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Bacterial genome size and gene functional diversity negatively correlate with taxonomic diversity along a pH gradient. Nat. Commun. 14, 7437 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Modest functional diversity decline and pronounced composition shifts of microbial communities in a mixed waste-contaminated aquifer. Microbiome 13, 106 (2025).

Xu, Z. et al. Effects of biodegradable (PBAT/PLA) and conventional (LDPE) mulch film residues on bacterial communities and metabolic functions in different agricultural soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 472, 134425 (2024).

Tilman, D., Isbell, F. & Cowles, J. M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 471–493 (2014).

Li, K., Jia, W., Xu, L., Zhang, M. & Huang, Y. The plastisphere of biodegradable and conventional microplastics from residues exhibit distinct microbial structure, network and function in plastic-mulching farmland. J. Hazard. Mater. 442, 130011 (2022).

Zheng, W. Z. et al. Sustainable recycling of the biodegradable polyester poly (butylene succinate) via selective catalytic hydrolysis and repolymerization. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 209, 107771 (2024).

Meyer et al. Synergistic biodegradation of aromatic-aliphatic copolyester plastic by a marine microbial consortium. Nat. Commun. 11, 5790 (2020).

Jang, Y. et al. Enhancing biodegradation of PBAT through bio-stimulation using Pseudozyma jejuensis for effective plastic waste reduction. Chemosphere 340, 139867 (2023).

Apinya, T., Sombatsompop, N. & Prapagdee, B. Selection of a Pseudonocardia sp. RM423 that accelerates the biodegradation of poly(lactic) acid in submerged cultures and in soil microcosms. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 99, 23–30 (2015).

Lin, Z. et al. Enhancing pentachlorophenol degradation by vermicomposting associated bioremediation. Ecol. Eng. 87, 288–294 (2015).

Qiu, L. et al. Erosion reduces soil microbial diversity, network complexity and multifunctionality. ISME J. 15, 2474–2489 (2021).

Ratzke, C., Barrere, J. & Gore, J. Strength of species interactions determines biodiversity and stability in microbial communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 376–383 (2020).

Fan, P., Yu, H., Xi, B. & Tan, W. A review on the occurrence and influence of biodegradable microplastics in soil ecosystems: are biodegradable plastics substitute or threat?. Environ. Int. 163, 107244 (2022).

Sun, Y., Shi, J., Wang, X., Ding, C. & Wang, J. Deciphering the mechanisms shaping the plastisphere microbiota in soil. Msystems 7, e00352–22 (2022).

Ngugi, D. K. et al. Abiotic selection of microbial genome size in the global ocean. Nat. Commun. 14, 1384 (2023).

Bhatt, P. et al. New insights into the degradation of synthetic pollutants in contaminated environments. Chemosphere 268, 128827 (2021).

Wright, R. J., Bosch, R., Langille, M. G., Gibson, M. I. & Christie-Oleza, J. A. A multi-OMIC characterisation of biodegradation and microbial community succession within the PET plastisphere. Microbiome 9, 1–22 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Effect of weak electrical stimulation on m-dichlorobenzene biodegradation in biotrickling filters: insights from performance and microbial community analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 390, 129881 (2023).

de Sousa, S. T. P. et al. Exploring the genetic potential of a fosmid metagenomic library from an oil-impacted mangrove sediment for metabolism of aromatic compounds. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 189, 109974 (2019).

Jia, X. et al. Effects of LDPE and PBAT plastics on soil organic carbon and carbon-enzymes: a mesocosm experiment under field conditions. Environ. Pollut. 362, 124965 (2024).

Rillig, M. C., Leifheit, E. & Lehmann, J. Microplastic effects on carbon cycling processes in soils. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001130 (2021).

Hu, X. et al. Metagenomic strategies uncover the soil bioavailable phosphorus improved by organic fertilization in Mollisols. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 349, 108462 (2023).

Du, T. et al. Metagenomics insights into the functional profiles of soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles in a walnut orchard under various regimes of long-term fertilisation. Eur. J. Agron. 148, 126887 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Degradation of biodegradable plastic films in soil: microplastics formation and soil microbial community dynamics. J. Hazard. Mater. 492, 138250 (2025).

Hua, Z. et al. Quantitative analysis of PBAT microplastics and their degradation products in soil by mass spectrometry. Eco-Environ. Health 4, 100166 (2025).

Liao, J. & Chen, Q. Biodegradable plastics in the air and soil environment: low degradation rate and high microplastics formation. J. Hazard. Mater. 418, 126329 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. Collective dynamical regimes predict invasion success and impacts in microbial communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 406–416 (2025).

Sutkar, P. R., Gadewar, R. D. & Dhulap, V. P. Recent trends in degradation of microplastics in the environment: a state-of-the-art review. J. Hazard. Mater. 11, 100343 (2023).

Fu, L. et al. Continuous application of bioorganic fertilizer induced resilient culturable bacteria community associated with banana Fusarium wilt suppression. Sci. Rep. 6, 27731 (2016).

Shi, Z., Xiong, L., Liu, T. & Wu, W. Alteration of bacterial communities and co-occurrence networks as a legacy effect upon exposure to polyethylene residues under field environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 426, 128126 (2022).

Nannipieri, P. et al. Soil enzymology: classical and molecular approaches. Biol. Fertil. Soils 48, 743–762 (2012).

Chen, L. et al. Nitrogen availability regulates topsoil carbon dynamics after permafrost thaw by altering microbial metabolic efficiency. Nat. Commun. 9, 3951 (2018).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, 884–890 (2018).

Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Edgar, R. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Callahan, B. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bolger, A., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, D., Liu, C., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package (R package version 2.0–4, 2015).

Zhang, J. & Zhang, M. J. Spaa: Species Association Analysis http://CRAN.R–project.org/package=spaa (R package version 0.2.1, 2013).

Mendiburu, F. & Simon, R. Agricolae – Ten years of an open source statistical tool for experiments in breeding, agriculture and biology. PeerJ 3, e1748 (2015).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

McMurdie, P. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Liu, C., Cui, Y., Li, X. & Yao, M. Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97, fiaa255 (2021).

Nguyen, L., Schmidt, H., Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 256–259 (2019).

Sloan, W. et al. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 732–740 (2005).

Csárdi, G. Modeling Complex Systems by Evolving Networks. PhD thesis (Eötvös Loránd University, 2010).

Wen, T. et al. ggClusterNet: an R package for microbiome network analysis and modularity-based multiple network layouts. iMeta 1, e32 (2022).

Peng, Z. et al. Agricultural subsoil microbiomes and functions exhibit lower resistance to global change than topsoils in Chinese agroecosystems. Nat. Food 6, 375–388 (2025).

Zhang, H. et al. Multiple stressors drive multitrophic biodiversity and ecological network dynamics in a shrinking sandy lake. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 527 (2024).

Shi, Z. C. W. PE residue. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29974594.v2 (2025).

Shi, Z. chenyunshu0817/PE-residue2024: CW PE residue (v1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16902958 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Hainan University (No. KYQD(ZR)20018). We gratefully acknowledge Meijie Wang for her excellent assistance in conducting the field experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. conducted the field experiments, collected and processed the samples, analysed the data, and prepared the original draft. L.X. and Z.L. assisted with data analysis and visualization. F.S., Q.Y., and J.K.W. contributed to manuscript preparation and data analysis. W.W. supervised the project, revised the manuscript, and provided guidance of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jie Wang, Jingjing Peng, Youzhi Feng, Fayuan Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: David Favero and George Inglis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Xiong, L., Li, Z. et al. Biodegradable plastic exposure enhances microbial functional diversity while reducing taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom soil microbiota in cherry tomato fields. Commun Biol 8, 1675 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09070-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09070-z