Abstract

Consciousness alterations occur across various states, encompassing changes in both arousal and awareness. The contributions of thalamic nuclei of consciousness remain incompletely understood. We analyzed fMRI data across general anesthesia (propofol N = 12, sevoflurane N = 12), disorders of consciousness (DoC) (minimally conscious state N = 9, unresponsive wakefulness syndrome N = 9), and sleep stages (wakefulness N = 31, NREM1 N = 24, NREM2 N = 19), investigating thalamocortical connectivity, local fluctuation (complexity/variability), and their coupling. In our results, propofol affected pulvinar-cortical connections; sleep transitions involved ventral lateral posterior (VLp), medial geniculate, and centromedian nuclei; DoC showed extensive disconnections. Five key nuclei demonstrated state- specific alterations: two first-order (VLp, ventral posterolateral) and three higher-order nuclei (pulvinar, centromedian, mediodorsal), with higher-order nuclei showing more consistent involvement. Decreased complexity/variability occurred in 4-6 nuclei during anesthesia and 4-5 in DoC patients. Nucleus-specific coupling between local fluctuation and connectivity systematically varied with consciousness state. This framework advances understanding of thalamic consciousness orchestration and provides potential therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consciousness forms the foundation of human perception of the self and environment, and encompasses two critical dimensions: awareness and arousal1. These distinct states of consciousness manifest differently under various physiological, pharmacological, and pathological conditions. General anesthesia is characterized by low awareness and arousal, the minimally conscious state (MCS) by moderate awareness and high arousal, the unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS) by low awareness and high arousal, and the non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep by moderate awareness and arousal2,3 (Fig. 1a). These states are regulated by complex neural networks4. General anesthesia suppresses arousal and cognition through specific neuronal inhibition5, while disorders of consciousness (DoC) typically result from trauma or ischemia, leading to diminished responses to external stimuli6. Sleep exhibits characteristic neural activity patterns distinct from both these states7. Within these complex neural regulatory networks, the thalamus serves as a hub region connecting cortical and subcortical structures, thereby modulating different states of consciousness8,9,10.

a The wakefulness state is characterized by high levels of both awareness and arousal; During NREM sleep, both awareness and arousal are maintained at moderate levels; In MCS, patients exhibit moderate awareness accompanied by high arousal; UWS patients maintain high arousal despite significantly reduced awareness; Under anesthesia, both awareness and arousal levels are substantially suppressed. b Three datasets representing different states of consciousness were used in this study. The anesthesia dataset included propofol anesthesia (N = 12) and sevoflurane anesthesia (N = 12); the DoC dataset, which included MCS (N = 9) and UWS (N = 9); and the sleep dataset included wakefulness (N = 31), NREM1 (N = 24), and NREM2 (N = 19). c The data analysis workflow. First, we implemented a preprocessing pipeline for datasets acquired at different consciousness states, and performed region of interest (ROI) extraction using predefined brain atlases to obtain time series from cortical regions and thalamic nuclei. Second, we conducted an assessment of thalamocortical functional connectivity using Pearson’s correlation. Then, we analyzed BOLD signal dynamics in thalamic nuclei through sample entropy (complexity) and rolling standard deviation (variability) calculations. Finally, we estimated correlations between local variation and connection changes using Spearman’s rank correlation.

Numerous clinical studies have shown that the thalamus plays a crucial role in the transitions of consciousness. Some researchers found that propofol- and sevoflurane-induced loss of consciousness (LOC) is associated with disrupted thalamocortical communication11,12, while several studies reported abnormal activity in the thalamic nuclei of DoC patients13,14,15. During sleep, some studies have found that the thalamus plays a pivotal role in sustaining wakefulness and regulating NREM sleep16,17. Changes in thalamocortical functional connectivity represent a common neural mechanism underlying alterations in consciousness, whether in the context of anesthesia-induced reversible LOC, persistent pathological changes in DoC patients, or physiological transitions of consciousness during sleep cycles. Recent work has demonstrated that parietal cortex, striatum, and thalamus show greater integration compared to frontal cortex during conscious states, highlighting the importance of cortico-subcortical networks in consciousness regulation18. Additionally, study in non-human primates demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the central thalamus restores arousal and cortical signatures during anesthesia19.

For blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals in the brain, functional connectivity has been widely employed to characterize regional neural synchronization, and thalamocortical functional connectivity is closely associated with consciousness20. To further elucidate the thalamus’s role in consciousness, the local fluctuations indices, complexity and variability can quantify pattern intricacy and signal fluctuations, respectively, both of which correlate with underlying neural activity21,22. Sample entropy quantifies signal complexity and correlates with brain dynamics23. In contrast, rolling SD measures time-varying signal variability. Huang et al.22 observed a widespread reduction in BOLD standard variability across cortical regions during anesthesia and DoC; however, the dynamic changes in the thalamus during this process remain unclear. Treating the thalamus as a homogeneous structure may obscure the functional specificity of distinct nuclei. Investigating specific thalamic nuclei, rather than global thalamic changes, is crucial for understanding consciousness-related neural mechanisms.

In this study, we aimed to address the following questions: (1) How do thalamocortical connections change under different consciousness states? (2) Which thalamic nuclei consistently appear locally active across different states of consciousness? and (3) Is there a relationship between thalamocortical functional connectivity and local fluctuations? Therefore, we analyzed three datasets corresponding to different states of consciousness: the anesthesia dataset (propofol anesthesia [N = 12] and sevoflurane anesthesia [N = 12]), the DoC dataset (MCS [N = 9] and UWS [N = 9]), and the sleep dataset (wakefulness [N = 31], NREM1 [N = 24], and NREM2 [N = 19]) (Fig. 1b). To this end, we analyzed the thalamocortical functional connectivity to identify the thalamic nuclei that undergo connectivity changes (Fig. 1c). Subsequently, we examined sample entropy (complexity) and rolling SD (variability) to investigate how alterations in states of consciousness affect local fluctuations in BOLD signals in specific thalamic nuclei. Finally, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to explore the relationship between changes in thalamocortical connectivity and local fluctuations across different states of consciousness. This study reveals that distinct thalamic nuclei orchestrate consciousness through state-specific patterns of functional connectivity disruption and local signal dynamics, with five key nuclei (ventral lateral posterior [VLp], ventral posterolateral [VPL], pulvinar [Pul], centromedian [CM], and mediodorsal [MD]) demonstrating systematic alterations across pharmacological, pathological, and physiological consciousness transitions. This investigation advances our understanding of how thalamic nuclei dynamically modulate consciousness states, with particular emphasis on functional connectivity patterns within thalamocortical networks during transitions between awareness and arousal.

Results

Thalamocortical functional connectivity changes across consciousness states

Thalamocortical connections have been demonstrated to be associated with changes in consciousness20. We investigated whether changes in consciousness states are reflected in the thalamocortical functional connectivity patterns of the thalamic regions.

Following the preprocessing, BOLD signals of 11 thalamus nuclei were first extracted by using a high spatial resolution thalamic atlas24, including anteroventral (AV) nucleus, ventral posterolateral (VPL) nucleus, ventral lateral anterior (VLa) nucleus, ventral lateral posterior (VLp) nucleus, ventral anterior nucleus (VA) nucleus, mediodorsal (MD) nucleus, centromedian (CM) nucleus, habenula (Hb), pulvinar (Pul), medial geniculate nucleus (MGN), and lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Functional connectivity was quantified by computing Pearson correlation coefficients between each selected thalamic nucleus and 114 predefined cortical ROIs, which corresponded to the seven functional brain networks identified in Yeo et al.‘s study (visual [VIN], somatomotor [SMN], dorsal attention [DAN], salience [SAN], limbic [LIN], frontoparietal [FPN], and default mode networks [DMN])25. All significantly altered cortical ROIs during the consciousness alteration are listed in Supplementary Tables 1–5. We first computed the global efficiency of functional connectivity matrices, confirming that decreases in awareness and arousal levels in our dataset reduce information integration, as detailed in Supplementary Methods and Results (Global Efficiency section; Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, global efficiency decreased significantly under anesthesia and in DoC patients (p < 0.05), but showed only subtle changes during sleep.

During anesthesia, propofol disrupted Pul-cortical and MGN-cortical connectivity, while sevoflurane showed no significant thalamocortical changes (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1). In the DoC datasets, the MCS group showed reduced cortical connectivity from VLp, Pul, and MD. The UWS group exhibited similar changes, but the extent of the significant changes was less pronounced than in the MCS (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Tables 2, 3). Sleep stage analysis showed no significant functional connectivity differences between wakefulness and NREM1 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Tables 4, 5). Transitions to NREM2 from both wakefulness and NREM1 was characterized by a reduction in thalamocortical connectivity across the VPL, MGN, CM, and Pul nuclei.

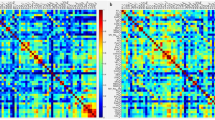

a–c Functional connectivity between thalamic nuclei and 114 cortical ROIs with statistical significance from high to low consciousness states during anesthesia, DoC, and sleep states, respectively. Cortical ROIs correspond to seven functional networks defined by Yeo et al. Difference matrices showing correlation coefficient changes between high and low consciousness states (red indicates stronger connectivity in high consciousness state; blue indicates weaker connectivity; asterisks denote significant differences). Asterisks denote significant differences where functional connectivity significantly decreased (p < 0.05) and correlation coefficients were >0.3 in the high consciousness state. Cortical significance maps showing significantly altered regions, with color intensity indicating significance level.

For pharmacological propofol-induced anesthesia and pathological DoC, changes in connectivity between the Pul nucleus and cortex accounted for a substantial proportion of all significant changes, whereas the MGN under propofol anesthesia, and the VLP and MD nuclei in the DoC group constituted relatively smaller proportions of consciousness state alterations (Fig. 3a). Regarding physiological sleep, transitions from wakefulness to NREM2 primarily involved changes in the MGN, followed by the CM and VPL nuclei, whereas significant changes between NREM1 and NREM2 stages were predominantly distributed in the VPL and CM nuclei, with a smaller proportion in the Pul nucleus and MGN.

a The proportion of thalamic nuclei with correlation coefficients >0.3 and statistical significance across consciousness levels, from high to low consciousness states. b The proportion of individual cortical functional networks with correlation coefficients >0.3 and statistical significance across consciousness levels, from high to low consciousness states. c Integration of sub-figures (a-b), illustrating the proportions of thalamic nuclei and cortical functional networks with correlation coefficients >0.3 and statistical significance across different levels of awareness and arousal.

From the perspective of cortical networks, propofol anesthesia altered connectivity in all networks except the SMN, with the FPN and DMN showing the largest proportions of change (Fig. 3b). In DoC patients, significant changes predominantly occurred in the FPN and DMN but also in the SAN, with relatively fewer changes in the VIN and SMN. For the sleep process, networks exhibiting significant changes included the VIN, SAN, and DMN, with smaller proportions in the SMN and FPN. Overall, significant changes in anesthesia and DoC were concentrated in the Pul nucleus, whereas changes during sleep were distributed across the MGN, VPL, and CM nuclei. All three altered states of consciousness induced significant changes in the connectivity between the DMN, FPN, and thalamic nuclei.

Because no significant changes in thalamocortical connectivity were observed when comparing wakefulness with sevoflurane anesthesia or with the NREM1 stage, we further investigated changes in functional connectivity among 114 the cortical ROIs (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 2). In the anesthesia group, 196 pairs of ROIs showed significant changes with propofol, while 49 pairs changed with sevoflurane. In the DoC group, 380 ROI pairs showed significant changes in patients with MCS, whereas 290 pairs showed changes in patients with UWS. In the sleep group, 279 pairs of ROIs showed significant decreases between the wakefulness and NREM2 stages and 36 pairs of ROIs showed significant decreases between the NREM1 and NREM2 stages. During sevoflurane anesthesia, while thalamocortical connectivity shows no significant changes, loss of consciousness may depend on alterations in cortico-cortical functional connectivity. During sleep, the transition from wakefulness to NREM1 exhibits no significant changes in cortico-cortical connectivity, suggesting that increased sleep depth requires accumulated functional changes before statistical significance is manifested.

Integrating these results, we observed significant changes in the Pul nucleus across three distinct states of consciousness (wakefulness-propofol anesthesia, control-MCS, control-UWS, and NREM1-NREM2), with the transition from MCS to UWS being primarily accompanied by a decrease in awareness levels. The reduction in awareness and arousal levels resulted from alterations in multiple thalamocortical networks, with the corresponding cortical networks primarily concentrated in the FPN and DMN. Propofol anesthesia and DoC involve changes in the Pul nucleus, whereas sleep involves changes in the CM, VPL nuclei, and MGN. From the perspective of awareness and arousal, thalamocortical connections involving the VPL and CM nuclei exhibit relatively minor changes in awareness and arousal processes (during sleep), whereas in DoC, changes in thalamocortical connections involving the Pul nucleus correlate with awareness levels, while the remaining VLp, MD nuclei and MGN (during propofol anesthesia) nucleus-cortical connections may be simultaneously associated with both awareness and arousal.

Identification of consciousness-related thalamic nuclei through complexity and variability signatures

To identify the thalamic nuclei that may be affected by consciousness state transitions, we analyzed BOLD signal characteristics using two measures: sample entropy for complexity and rolling SD for variability, both of which are established indicators of neural activity (Fig. 5a).

a Sample entropy (left) and rolling standard deviation (right) of 11 thalamic nuclei across different consciousness states. Shaded regions demarcate distinct nuclear groups (anterior, lateral, posterior, and medial groups). Asterisks indicate significant changes in thalamic regions where the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed p < 0.05. b Venn diagrams showing significantly altered thalamic nuclei across consciousness states, with emphasis on MCS-UWS differences in the DoC group. c Anatomical visualization of significantly altered thalamic nuclei, including two first-order nuclei (VLp and VPL nuclei) and three higher-order nuclei (CM, Pul, and MD nuclei).

In the general anesthesia group, propofol anesthesia significantly reduced sample entropy in the VA, VLp, Pul, LGN and MD nuclei, and decreased the rolling SD in the VA, VLp, MD, Pul and LGN nuclei (Supplementary Tables 6, 7). Sevoflurane anesthesia led to significant reductions in sample entropy within the VLp, VPL, Pul, CM, MD, and Hb nuclei, alongside decreased rolling standard deviation in the VLp, Pul, MD, and Hb nuclei (Supplementary Tables 8, 9). This pattern of decreased complexity and variability in multiple thalamic nuclei, particularly in higher-order nuclei such as Pul and MD nuclei, suggests that both propofol and sevoflurane may achieve their consciousness-altering effects by disrupting the information-processing capabilities of specific thalamic regions. In the DoC group, significant changes in sample entropy were observed primarily in the Pul, MGN, CM, and MD nuclei (Supplementary Table 10), while significant changes in the rolling SD were concentrated in the VPL nucleus, Pul, MGN, CM, and MD nuclei (Supplementary Table 11). These results demonstrate that, compared with controls, MCS and UWS exhibited significant reductions in thalamic nuclei activity with distinct patterns. Analysis of the sleep dataset revealed no significant changes in either measure across wakefulness, NREM1, or NREM2. During the transition from wakefulness to NREM1 and NREM2 sleep, both awareness and arousal changed moderately relative to general anesthesia, suggesting that NREM sleep retains more brain dynamics than anesthesia.

Furthermore, to examine the relationship between BOLD signal complexity and variability across consciousness states, we computed the Spearman rank correlation between sample entropy and rolling SD in the four datasets. Analysis revealed strong correlations between sample entropy and rolling SD across all states (p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Integrating these findings across consciousness states, we observed distinct patterns of changes in thalamic nuclei complexity and variability that relate differently to arousal and awareness dimensions. In the anesthesia group, the complexity and variability of the thalamic nuclei may be associated with both arousal and awareness, whereas the progression from controls through MCS to UWS primarily reflects changes in awareness. Based on these results, we identified five thalamic nuclei that showed significant changes in both sample entropy and rolling SD across the consciousness states. The five thalamic nuclei included two first-order nuclei, the VLp and VPL nuclei, and three higher-order nuclei, the Pul, CM, and MD nuclei (Fig. 5b, c).

Coupling between local thalamic activity and cortical connectivity

During the transition between the different states of consciousness, we observed significant changes in thalamic nuclei regarding both thalamocortical connectivity and local fluctuations. To investigate whether thalamic nuclei exhibit coupling between thalamocortical functional connectivity and local thalamic fluctuations, we calculated average functional connectivity between each thalamic nucleus and cortex, and then performed Spearman’s rank correlation analysis between these values and both sample entropy and rolling SD (Fig. 6).

a Correlation of sample entropy and average connectivity strength (left) and correlation of rolling SD and average connectivity strength (right). Shaded regions demarcate distinct nuclear groups (anterior, lateral, posterior, and medial groups). Asterisks indicate significant changes in thalamic regions where FDR-corrected p < 0.05 for the corresponding correlation coefficient. b Integration of thalamic nuclei with statistically significant correlation coefficients between local fluctuations and average connectivity strength across different consciousness states. The forward slash (/) indicates that no significant activation was detected in any thalamic nuclei.

Under propofol anesthesia, significant positive correlations between sample entropy and mean connection strength in the VPL nucleus and MGN during wakefulness were abolished, becoming non-significant under anesthesia. In contrast, the CM nucleus transitioned from a non-significant weak correlation during wakefulness to a significant negative correlation after anesthesia (Supplementary Table 12).

Similarly, regarding the correlation between rolling SD and mean connection strength, the VPL, Pul, and MGN exhibited significant positive correlations during wakefulness that became non-significant weak correlations after anesthesia, and the CM nucleus likewise shifted to a significant negative correlation (Supplementary Table 13). Under sevoflurane anesthesia, only the LGN changed from a non-significant positive correlation during wakefulness to a significantly strong correlation under anesthesia (Supplementary Tables 14, 15).

In DoC patients, a significant positive correlation between the sample entropy and mean connection strength was observed in the VA nucleus of patients with UWS, which was absent in both the control group and patients with MCS (Supplementary Tables 16, 17). Additionally, the MGN showed a significant positive correlation between sample entropy and mean connection strength in the control group, whereas no significant correlations were observed in the MCS and UWS patients. In the sleep group (Supplementary Tables 18, 19), only the Hb nucleus during NREM1 sleep exhibited a significant negative correlation between sample entropy and mean connection strength; while only the MGN during NREM1 sleep demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the rolling SD and mean connection strength.

Additionally, we employed support vector machine (SVM) methods to perform classification analyses of different consciousness states, using the average thalamocortical functional connectivity, complexity, and variability of different thalamic nuclei as input data (detailed in Supplementary Methods and Results sections, Machine learning; Supplementary Tables 20–27). The results demonstrated that SVM classification achieved relatively good performance under propofol and sevoflurane anesthesia, with the VLp and VLa nuclei exhibiting optimal classification performance, respectively. For the classification of DoC patients and sleep states, accuracy was relatively lower; however, certain nuclei, such as MGN and LGN, still demonstrated considerable classification capacity. We observed that several nuclei showing statistical significance in thalamocortical functional connectivity and local fluctuations also achieved relatively high classification accuracy. However, relying solely on thalamus-related features for state classification may have inherent limitations, and future studies could consider incorporating spatial information to enhance classification performance.

Discussion

This study investigated the role of thalamic nuclei in consciousness state transitions through analysis of thalamocortical functional connectivity, local fluctuations, and the relationship between these two components. Our analysis yielded three key findings.

-

(1).

Different consciousness states showed distinct patterns of thalamocortical functional disruption, with propofol anesthesia (low awareness/low arousal) primarily affecting Pul connections, and sleep progression from wakefulness to NREM2 (moderate awareness/low arousal) selectively affecting VPL, CM nuclei, and MGN connectivity. In DoC, where arousal was preserved but awareness varied, the results showed more extensive disconnections in the VLp, Pul, and MD pathways (more extensive in MCS than in UWS).

-

(2).

Across states with varying levels of arousal and awareness, five thalamic nuclei (VLp, VPL, Pul, CM, and MD nuclei) demonstrated significant alterations in BOLD signal complexity and variability. First-order nuclei (VLp and VPL nuclei) showed significant changes during anesthesia (low awareness/low arousal) and DoC (varying awareness/high arousal), whereas higher-order nuclei (Pul, CM, and MD nuclei) exhibited changes across all states, suggesting potential interventions in consciousness modulation.

-

(3).

Analysis of local thalamic activity and thalamocortical connectivity coupling revealed state-specific patterns across consciousness states. In anesthesia, VPL nucleus and MGN correlations present during wakefulness disappeared under unconsciousness, while CM nucleus shifted to a negative correlation. DoC patients showed VA-specific positive coupling in the UWS and progressive MGN decoupling with declining awareness. During sleep, Hb exhibited negative correlations in NREM1, while MGN maintained positive coupling, indicating differential thalamic engagement during physiological consciousness fluctuations.

From a functional connectivity perspective, our results revealed that propofol anesthesia predominantly disrupts the connections between the Pul nucleus, a higher-order thalamic nucleus, and multiple brain networks. Previous research in macaques has shown that Pul nucleus modulates cortical synchronization and attention26. The propofol-induced disruption of Pul-cortical connections may therefore compromise information transmission, leading to diminished responsiveness to external stimuli. The MGN relays auditory information from the thalamus to the cortex27. During propofol anesthesia, mismatch negativity disappears with increasing drug concentration28,29, suggesting disrupted MGN-cortical connectivity that aligns with our results. Given the role of the MGN in integrating auditory information, this suggests that the MGN participates in bottom-up information flow changes during propofol anesthesia. These results suggest that disrupted connectivity between the Pul nucleus and cortex, as well as MGN and cortex, contributes to propofol-induced unconsciousness. In contrast, sevoflurane anesthesia did not induce significant changes in thalamocortical connectivity, and exhibited limited significant alterations in cortico-cortical connections. Although previous studies have documented decreased functional connectivity under sevoflurane anesthesia30,31, our divergent findings may be related to different anesthetic depths, highlighting the need for further investigation.

Examination of DoC revealed that MCS and UWS patients exhibited significantly decreased functional connectivity between the VLp, Pul, and MD nuclei and cortical regions compared with the control group. The abnormal connectivity in the VLp (motor control and coordination32) and MD (memory and executive function33) nuclei reflects impaired motor and cognitive circuits in DoC patients. The consistent changes in the Pul thalamic nuclei between DoC and propofol anesthesia support their pivotal role in regulating awareness, suggesting that DoC and anesthesia-induced unconsciousness may partially share common neural mechanisms. Interestingly, patients with UWS showed less significant disruption of thalamocortical connectivity than patients with MCS, which is consistent with previous findings15. By analyzing the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRglc) in patients with MCS, Stender et al. demonstrated that UWS patients exhibited uniformly reduced metabolism across all brain regions34. This global metabolic suppression may explain the more uniform reduction in neural connectivity observed in the UWS, in contrast to the selective disruption patterns observed in the MCS.

Thalamocortical functional connectivity showed a non-significant increase from wakefulness to NREM1 sleep, consistent with findings by Hale et al.35. This enhancement may reflect a brain’s shift from external vigilance to internal cognitive processing during early sleep onset. A further progression from wakefulness to NREM2 sleep was characterized by significant decreases in functional connectivity, specifically in the VPL, CM nuclei, and MGN, compared with the wakefulness to NREM1 transition. The VPL nucleus mediates somatosensory integration36, and its reduced cortical connectivity reflects decreased sensory processing during sleep progression. In NREM2 sleep, the thalamus performs “sensory gating”: the MGN blocks auditory input to maintain sleep stability, manifesting as weakened MGN-cortical connectivity. Similarly, reduced CM nucleus connectivity—which normally triggers arousal from NREM sleep37—may help maintain sleep states. The enhanced thalamocortical functional connectivity during the transition from wakefulness to NREM1 may reflect a shift in the brain from external vigilance to internal cognitive processing. Subsequently, the significant reduction in cortical connectivity with both the VPL, CM, and MGN nuclei during NREM2 may contribute to sleep maintenance through dual mechanisms: inhibition of sensory input (VPL and MGN) and decreased arousal-triggering capability (CM).

Moreover, the transition from high to low levels of consciousness is associated with significantly reduced thalamic functional connectivity, primarily in the FPN and DMN. Disruption of thalamic-mediated network information integration ultimately leads to the dissociation of conscious content and the interruption of external perception38, suggests that the collapse of the integrative function of thalamus as a multi network hub is a critical factor in the decline in consciousness levels. Across three distinct consciousness states, the Pul nucleus predominantly mediates propofol anesthesia, while the VPL, CM nuclei, and MGN primarily regulate NREM-related changes. Altered thalamocortical connectivity between the three thalamic nuclei and the cortex correlates with decreased arousal and awareness. In the progression from the control group through the MCS to the UWS, the arousal levels remained relatively high, and awareness progressively declined. The DoC group demonstrates significant alterations in the thalamocortical connectivity of the VPL, Pul, and MD nuclei. These findings further validate that the disconnection between these three thalamic nuclei and the cortex is specifically associated with awareness.

BOLD signal characteristics varied systematically with consciousness states, with higher complexity and variability marking the consciousness baseline and reduced measures indicating states like anesthesia, sleep, MCS, and UWS. We identified the thalamic nuclei that showed significant changes across these states as being closely associated with consciousness. Our analysis revealed that the five nuclei demonstrated significant changes across all consciousness transitions. Primary nuclei (e.g., VLp for movement regulation and synchronization32, VPL for sensory inputs36) showed reduced complexity, corresponding to impaired stimulus perception under anesthesia and in DoC. Higher-order thalamic nuclei, which act as integration hubs for cortical information flow and cognition, include the Pul (sensory-cognitive processing39), CM (arousal and attention40), and MD (memory and executive functions33). Our findings indicate that under anesthesia and DoC, the disruption of these higher-order thalamic functions impairs cortical information integration, resulting in compromised external information processing. Among these nuclei, the Pul and MD nuclei are commonly involved in propofol anesthesia, sevoflurane anesthesia, and DoC, suggesting a stronger association with consciousness changes than other nuclei.

Our analysis revealed a significant difference in BOLD signal characteristics, with MCS patients showing lower variability and complexity compared to UWS patients. As pointed out by Laureys et al., brain activity in patients with UWS is characterized by nonspecific, randomized brain activity41. While patients with MCS show partial restoration of brain function42, that remains insufficient for complex information processing. Therefore, these BOLD signal characteristics may serve as potential biomarkers for differentiating between MCS and UWS. Multiple studies have documented sleep-induced disruptions in thalamocortical connectivity43,44,45. Notably, our analysis revealed no significant changes in thalamic signal characteristics during the NREM1 and NREM2 sleep stages, suggesting that spontaneous sleep may selectively modulate thalamocortical connectivity while preserving intrinsic thalamic BOLD signal dynamics.

Furthermore, in our dataset, the transition from wakefulness to anesthesia resulted in a shift from high arousal/high awareness to low arousal/low awareness, whereas the progression from the control group to the MCS to the UWS represented a change from high arousal/high awareness to moderate arousal/low awareness to low arousal/low awareness. Nuclei showing changes in complexity and variability in the DoC group were likely associated with awareness. Together, these findings suggest that among the nuclei identified in our study, the VPL, Pul, CM, and MD nuclei, but not the VLp nucleus, were likely associated with conscious awareness.

After investigating the thalamocortical functional connectivity and local fluctuations within the thalamus, we employed Spearman’s rank correlation to examine whether the thalamic nuclei simultaneously link thalamocortical functional connectivity with local fluctuations. The coupling relationships may carry important physiological implications for consciousness regulation. We suggest that positive correlations between local fluctuations and thalamocortical connectivity might suggest that enhanced intrinsic neural activity within thalamic nuclei tends to coincide with stronger cortical integration, potentially supporting consciousness maintenance and content integration. Conversely, we interpret negative correlations as possibly reflecting a more complex relationship where increased local activity appears to correspond with reduced cortical connectivity, which we suggest may indicate competitive resource allocation or compensatory mechanisms that emerge during altered consciousness states.

In the propofol dataset, significant positive correlations between local fluctuations and thalamocortical functional connectivity emerged in the VPL/MGN during wakefulness. These two nuclei, serving as the somatosensory and auditory relay nuclei, respectively46,47, exhibited significant positive correlations, reflecting the demand for integrating external information and real-time transmission of cortical information during wakefulness. Weiner et al. indicated that the CM nucleus, as a medial nucleus, does not selectively connect to a specific network under propofol anesthesia48. In our results, the significant negative correlation between local fluctuations and cortical network connectivity under propofol anesthesia may be related to its inhibitory regulatory role in awareness and arousal. Under sevoflurane anesthesia, variability strongly correlated with LGN cortical connectivity, potentially reflecting visual pathway compensation. This differs from propofol due to distinct mechanisms: propofol enhances GABA-A receptor inhibition49, while sevoflurane inhibits NMDA receptors and enhances various inhibitory ion channels50, thereby generating different neurodynamic characteristics.

In UWS patients, sample entropy strongly correlated with the connectivity strength of the VA nucleus. Since the VA nucleus transmits basal ganglia output to the cortex51, this positive correlation may reflect compensatory reorganization through enhanced local-cortical connections, though it fails to restore awareness-related functions. The lack of significant MGN correlation between sample entropy and connection strength in MCS/UWS patients suggests that dissociation between local auditory fluctuations and whole-brain connectivity may impair network integration and awareness. Notably, MGN sample entropy correlated positively in MCS but negatively in UWS, consistent with Boly et al.‘s finding that MCS patients process complex auditory information while UWS patients retain only basic auditory encoding52. However, these interpretations remain speculative and would require further validation through causal investigations.

In sleep state research, the habenula (Hb) nucleus, which modulates emotions and sleep regulation53, shows hyperactivation-induced REM sleep increases54. Our results reveal a negative correlation between Hb sample entropy and connectivity during NREM1, suggesting that decoupling between local dynamics and functional integration in Hb may be a key mechanism for maintaining NREM1 stability. In contrast, the positive correlation between MGN rolling SD and connectivity in NREM1 reflects preserved sensory processing during light sleep55.

Regarding arousal, the CM nucleus showed weakened cortical connectivity and altered local-connectivity coupling during propofol anesthesia, supporting the role of medial thalamic nuclei in maintaining cortical arousal56. Specifically, the negative correlation exhibited by the CM nucleus during anesthesia may reflect a compensatory mechanism of its regulatory network as arousal levels decrease. Additionally, the decoupling phenomenon during NREM1 sleep further confirmed the differential roles of specific thalamic nuclei in arousal state regulation. Regarding the awareness dimension, changes in the coupling relationships in relay nuclei (VPL, MGN, LGN) reveal the importance of sensory information integration for awareness. Particularly in DoC patients, abnormal MGN coupling may reflect the dysfunction in auditory awareness networks. The differences between patients with MCS and UWS in this respect suggest that recovery of awareness function may be closely related to the synergistic effects between local neural activity and large-scale functional connectivity in specific sensory pathways.

In this study, we investigated the impact of thalamic nuclei on consciousness by comparing anesthesia, DoC, and sleep datasets, identifying VPL and CM nuclei as potentially associated with arousal and awareness. Through co-activation analysis of thalamic activity, Han et al. found that activation of the VPL nucleus remained high during UWS (impaired awareness) but decreased during REM (high arousal)3. Our results revealed that the VPL nucleus showed significant alterations in complexity, variability, and functional connectivity under general anesthesia, suggesting their potential involvement in awareness modulation. The same nuclei demonstrated differential contributions to arousal and awareness across consciousness states, possibly due to differences in computational metrics and datasets, warranting further investigation. Besides, Huang et al. demonstrated that anesthesia-induced loss of consciousness is accompanied by a transition in core-matrix functional geometry from a balanced state to a matrix-deficient state57. In our results, the VLp, MD and portions of the Pul nuclei that exhibited significant changes across different consciousness states correspond to the transmodal thalamic regions identified by Huang et al. (i.e., matrix-rich projecting areas), aligning with their core-matrix perspective. Notably, the VPL and portions of the Pul nuclei, which correspond to unimodal thalamic regions, also demonstrated significant changes in our results. As a complement to these findings, it indicates that thalamic regions with unimodal properties are likewise affected by alterations of the conscious state.

Our findings advance the understanding of thalamic dynamics during altered consciousness. We provide a nucleus-specific analysis of thalamocortical connectivity, local fluctuations, and their coupling across three distinct conditions. Recent studies of Panda et al. have provided critical insights into the dynamic properties of brain networks in DoC patients. Specifically, Panda et al. demonstrated that DoC patients exhibited shorter network state durations and reduced metastability in the subcortical fronto-temporo-parietal network (Sub-FTPN)58. This network exhibits substantial overlap with the fronto-temporo-parietal network, which is consistent with our current findings of altered thalamo-FPN connectivity in DoC patients (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, their study revealed that DoC patients demonstrated decreased broadcasting capacity between thalamus and fronto-temporo-parietal regions59. Consistent with these findings, our results demonstrate significantly reduced thalamocortical functional connectivity in the VLp, MD and Pul nuclei of DoC patients, confirming the thalamus as a critical hub for consciousness regulation.

Besides, the mesocircuit hypothesis proposed by Schiff et al. emphasizes the central thalamus (particularly the intralaminar nuclei) as a critical node in the frontal/prefrontal cortical–striatopallidal–thalamocortical loop systems, playing a pivotal role in maintaining consciousness states60. In the thalamic atlas employed in our study, the intralaminar nuclear components primarily comprise the CM nucleus. In our results, the CM nucleus showed significant changes during transitions between states of consciousness, which aligns with the mesocircuit model’s proposition that the central thalamus serves as a “switch” mechanism during consciousness transitions. It must be acknowledged that our results cannot directly establish a causal role of the CM nucleus in arousal enhancement or therapeutic interventions. Future studies should investigate DoC patients undergoing deep brain stimulation of intralaminar nuclei (such as CM and central lateral (CL) nuclei), to determine whether changes in consciousness levels (CRS-R scores) before and after stimulation correlate with local alterations in intralaminar thalamic nuclei.

Our findings reveal distinct mechanisms of propofol and sevoflurane anesthesia, which have significant implications for clinical practice. The selective disruption of Pul-cortical connectivity under propofol anesthesia, contrasted with the absence of significant thalamocortical changes under sevoflurane, indicates that these anesthetics achieve loss of consciousness through distinct neural pathways. These mechanistic differences may inform anesthetic selection for specific patient populations or surgical procedures. Furthermore, our findings provide neurobiologically informed targets for neuromodulation interventions. The consistent involvement of the CM nucleus across multiple states of consciousness, combined with its role in the mesocircuit hypothesis, strongly supports its therapeutic potential for deep brain stimulation in DoC patients61.

Limitations

Our study utilized datasets obtained using different MRI parameters across various consciousness states, which introduced potential confounds in cross-state comparisons. Differences in scanner parameters and acquisition duration may introduce systematic biases, thereby affecting our comparison results across different consciousness states. To mitigate these effects, we implemented standardized preprocessing pipelines using fMRIPrep. Furthermore, we focused our analysis on relative changes within each dataset rather than absolute comparisons across datasets. Future studies adopting unified acquisition protocols across all consciousness states will enhance the validity of state comparisons and provide more definitive evidence for common thalamocortical mechanisms of consciousness suppression. From a methodological point of view, while sample entropy and rolling SD effectively captured BOLD signal dynamics, additional metrics for neural activity characterization could reveal complementary aspects of thalamic function across consciousness states. The limitations underscore the need for larger cohort studies with standardized data collection protocols across consciousness states and more sophisticated analytical frameworks to fully characterize the dynamic nature of consciousness-related thalamic activity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our analysis of alterations in pharmacological, pathological, and physiological consciousness revealed distinct thalamic mechanisms underlying consciousness regulation. We demonstrated that consciousness states exhibit characteristic thalamocortical disconnection patterns, with propofol anesthesia affecting Pul-cortical pathways, sleep transitions involving the VPL/CM nuclei and MGN, and showing VLp, Pul, and MD nuclei disconnections correlating with awareness levels. Five thalamic nuclei (VLp, VPL, Pul, CM, and MD nuclei) exhibited significant alterations in BOLD signal dynamics, with higher-order nuclei showing more consistent involvement across consciousness states. Additionally, the nucleus-specific coupling between local activity and global connectivity systematically varies with the consciousness state. These findings establish a hierarchical framework for thalamic involvement in consciousness regulation, providing potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for clinical interventions in disorders of consciousness.

Material and methods

Datasets-1: General anesthesia

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking University International Hospital, Peking University, Beijing, China. All the participants provided written informed consent. The study included 24 patients with vertebral canal occupation, 12 of whom were anesthetized with propofol (male/female: 8/4; age: 26–57 years) and 12 with sevoflurane (male/female: 8/4; age: 21–65 years). All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Prior to anesthesia induction, 10-min functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning was performed as a baseline. Continuous electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure measurement, and pulse oximetry were performed using an MRI-compatible vital signs monitor (GE Healthcare Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA). Following the confirmation of adequate collateral circulation via Allen’s test, continuous invasive arterial pressure monitoring was established through radial artery catheterization. Total intravenous anesthesia was administered using target-controlled infusion for both induction and maintenance in all study groups. Anesthesia was induced with target plasma concentrations of propofol (4–6 μg−1 mL) and remifentanil (3 ng−1 mL), or with sevoflurane (8%) at a fresh gas flow of 8 L−1 min with 80% oxygen. Rocuronium bromide (1 mg−1 kg) was administered intravenously when the bispectral index (BIS) decreased below 60. Following anesthesia induction and tracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation was initiated using an MRI-compatible anesthesia machine (GE Healthcare Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA) with continuous end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring. Anesthesia was maintained with target plasma concentrations of either propofol (4–6 μg−1 mL) and remifentanil (4–8 ng−1 mL), or sevoflurane (2.5–3%) and remifentanil (4–8 ng−1 mL). The BIS score was maintained between 40 and 60, and according to the anesthesiologists’ assessment, all patients remained unconscious under these conditions. After anesthesia induction, the BIS monitor was removed, and a 10-min equilibration period was allowed for hemodynamic and BIS stabilization before initiating fMRI scanning.

All anatomical and functional images were collected using a Siemens 3 T scanner (Siemens Verio Dot 3.0T, Germany) with an 8-channel phase sensitivity encoding head coil (IMRIS). High-resolution T1-weighted (T1w) anatomical images were acquired for each participant (TR/TE/TI = 2220/3.25/900 ms, FA = 90°, FOV = 250 × 250 mm, image matrix: 256 × 256, 192 slices with 1-mm thickness, gap = 0 mm). Functional images were acquired using whole-brain gradient-echo-planar images (TR/TE = 220/30 ms, FA = 90°, FOV = 192 × 192 mm, image matrix: 64 × 64). The scan time for both wakefulness and general anesthesia was 540 s.

Datasets-2: DoC

The dataset was previously published using analyses different from those applied here62, and all ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking University International Hospital, Peking University, Beijing, China. Written informed consent was obtained from the legally authorized representatives of all participants. By visually selecting patients with no apparent brain tissue damage, we included 18 DoC patients, of whom nine with MCS (male/female: 7/2; age: 21 to 69 years) and nine with UWS (male/female: 7/2; age: 36 to 69 years). All patients were in the chronic phase (>3 months) and were in a non-anesthetized resting state during data acquisition. The final CRS-R score was determined through a comprehensive evaluation based on five CRS-R assessments (Supplementary Table 28). An equal number of cases were randomly selected from the anesthesia dataset as the control group, ensuring no statistical differences in age and sex distributions (Supplementary Tables 29, 30).

Neuroimaging data were acquired using a 3.0-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scanner (Siemens Verio Dot 3.0 T, Germany) equipped with an eight-channel phased-array head coil (IMRIS). High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images were obtained using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.25 ms, inversion time (TI) = 900 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view (FOV) = 250 × 250 mm², acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1 mm, no interslice gap, and 192 sagittal slices. Whole-brain functional images were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence as follows: TR = 220 ms; TE = 30 ms; flip angle = 90°; FOV = 192 × 192 mm²; acquisition matrix = 64 × 64. Data acquisition lasted for 420 s.

Datasets-3: Sleep

The sleep data were obtained from the database OpenNeuro (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds003768), in which the simultaneous Electroencephalography (EEG) and fMRI during sleep were recorded63,64. All data were collected at the Pennsylvania State University after obtaining informed consent. In the dataset, several runs of sleep data were recorded, and three sleep stages (NREM1, NREM2, and NREM3) were marked; we extracted the sleep data of at least 3 min and reorganized the data into a single subject. Accordingly, 31 wakefulness, 24 NREM1, and 19 NREM2 data were included in this study.

Image acquisition was performed on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner equipped with a 20-channel head-neck coil. High-resolution structural images were obtained using a T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.28 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle = 8°, FOV = 256 × 256 mm², matrix size = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1 mm, 176 sagittal slices, no gap), followed by functional data acquisition using a gradient-echo EPI sequence (TR = 2100 ms, TE = 25 ms, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 220 × 220 mm², matrix size = 80 × 80, slice thickness = 4 mm, 35 axial slices with no gap, parallel imaging factor = 2). Each functional run consisted of 600 seconds.

fMRI data preprocessing

Previous research has demonstrated that FMRIB Software Library (FSL) serves as a powerful tool for preprocessing data from DoC patients, exhibiting excellent performance in ICA-based denoising procedures65. Given that employing different preprocessing methods may introduce potential sources of error, and considering fMRIPrep’s demonstrated advantages in reproducibility and methodological transparency66, we opted to implement fMRIPrep for standardized preprocessing across all datasets. Additionally, we employed an ICA-based FSL preprocessing pipeline consistent with López-González et al. to conduct sensitivity analysis on the DoC group data65, validating the robustness of our results (detailed in the Supplementary Methods and Results section, Preprocessing pipeline validation; Supplementary Fig. 4).

The preprocessing procedures were implemented using fMRIprep (https://fmriprep.org/en/25.0.0/)66 and the Python package nilearn (https://nilearn.github.io/dev/index.html)67. The preprocessing steps of T1 images are as follows: (1) correction for intensity non-uniformity; (2) skull-stripping; (3) brain tissue segmentation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white-matter (WM) and gray-matter (GM); (4) brain surfaces reconstruction; and (5) spatial normalization to standard space. The preprocessing steps of BOLD images are as follows: (1) discarding the first five points; (2) slice-time correction; (3) coregistration with T1 images; (4) head motion regression (six-dimensional motion derivatives and framewise displacement); (5) band-pass filtering to 0.01–0.1 Hz; (6) spatial smoothing with 6 mm FWHM; and (7) normalization of each voxel’s time-course to zero mean and unit variance. As the global signal has a potential impact on general anesthesia68, global signal regression (GSR) has not been applied to data preprocessing, and the CSF and WM signals were regressed out as confounds.

Following the preprocessing, BOLD signals of 11 thalamus nuclei were first extracted by using a high spatial resolution thalamic atlas24, including anteroventral (AV) nucleus, ventral posterolateral (VPL) nucleus, ventral lateral anterior (VLa) nucleus, ventral lateral posterior (VLp) nucleus, ventral anterior nucleus (VA) nucleus, mediodorsal (MD) nucleus, centromedian (CM) nucleus, habenula (Hb), pulvinar (Pul), medial geniculate nucleus (MGN), and lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Subsequently, the sample entropy and rolling SD were calculated for each thalamic ROI.

Functional connectivity analysis

In the present study, we analyzed the functional connectivity between the thalamus and ROIs using Pearson’s correlation. When investigating thalamocortical connectivity, we first examined whether there were linear temporal relationships between thalamic nuclei and different ROIs. Using a predefined cortical atlas with 114 ROIs69, we extracted ROI time series of the cerebral cortex. For functional connectivity analysis, we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients between thalamic nuclei and the cerebral cortex, followed by Fisher’s z-transformation. As supplementary alternative approaches, we also computed mutual information and spectral coherence (detailed in Supplementary Methods and Results section, Functional connectivity measures subsection; Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). Additionally, to distinguish between thalamocortical and cortico-cortical effects on consciousness state changes, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients among all 114 cortical ROIs.

Quantifying local fluctuation through sample entropy and rolling SD

Sample entropy is a method used to measure the complexity of a given time series. It is not sensitive to data sample points and is suitable for short time series70,71, which can be calculated using the following steps: First, for a time series \({{{\rm{x}}}}=[{{{{\rm{x}}}}}_{1},{{{{\rm{x}}}}}_{2},{{{{\rm{x}}}}}_{3},\ldots ,{{{{\rm{x}}}}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}]\) and embedding dimension m, the embedding vector can be constructed as \([{x}_{i},{x}_{i+1},{x}_{i+2},\ldots ,{x}_{i+m-1}]\). Then, the r-neighborhood conditional probability function \({c}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{m}\) for each \({{{\rm{i}}}}\in [1,{{{\rm{N}}}}-m]\) was calculated:

where r is the tolerance distance calculated by dividing the scaling parameter by the SD of the input vector. \(\Theta (\bullet )\) is the Heaviside function defined as

and the Chebyshev distance \({\Vert \bullet \Vert }_{1}\) is defined as:

Therefore, the sample entropy is given by

where Um is the average of \({C}_{i}^{m}\):

In the present work, we chose m = 2 and r = 0.5 as the parameters to calculate the sample entropy, which is consistent with previous studies21,23.

For low-frequency BOLD signals, we used the rolling SD of the evaluated variability. The analysis used a window size of 1/20 of the total signal length with single TR steps and computed the mean of the rolling SDs across all windows. The linear relationship between sample entropy and rolling SD was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients for each thalamic nucleus. Furthermore, we conducted sensitivity analyses on the parameter selection for sample entropy and rolling standard deviation to ensure that the chosen parameters were appropriate (detailed in Supplementary Methods and Results section, Sensitivity Analysis; Supplementary Figs. 7, 8).

Statistics and reproducibility

The sample size (n) for each group represents the number of biologically independent samples (i.e., individual human participants). The samples in this study were selected in accordance with previous experiments to reduce patient burden. No a priori statistical power calculations were conducted to guide sample size. The study comprised three independent datasets: (1) General Anesthesia Dataset: propofol anesthesia (n = 12) and sevoflurane anesthesia (n = 12); (2) Disorders of Consciousness Dataset: minimally conscious state (n = 9) and unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (n = 9); (3) Sleep Dataset: wakefulness (n = 31), NREM1 (n = 24), and NREM2 (n = 19). No experiments were technically replicated within participants; all analyses were performed on single scanning sessions per participant. In this study, replicates were defined at the subject level. For the general anesthesia dataset, each patient contributed two data points (wakefulness and anesthesia), representing within-subject comparisons. For the DoC dataset, each patient contributed a single data point representing their diagnosed consciousness state. For the sleep dataset, each recording session meeting the minimum duration criterion (≥3 min) was treated as an independent observation.

All neuroimaging analyses were performed using standardized preprocessing pipelines to ensure reproducibility. Functional MRI data preprocessing was conducted using fMRIPrep, which provides robust and reproducible preprocessing workflows. For the DoC dataset, sensitivity analyses were performed using an alternative ICA-based FSL preprocessing pipeline to validate the robustness of the findings. Thalamic nuclei were identified using a high-resolution thalamic atlas, which parcellated 11 thalamic nuclei bilaterally. Functional connectivity was computed between each thalamic nucleus and 114 cortical ROIs derived from the Yeo 7-network parcellation. Signal complexity was quantified using sample entropy with parameters m = 2 and r = 0.5, consistent with established protocols. Signal variability was assessed using rolling standard deviation with a window size of 1/20 of the total signal length. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to validate the appropriateness of these parameters. Each analysis (functional connectivity, sample entropy, rolling SD) was computed independently for each subject, and group-level statistics were performed across all subjects within each dataset. For machine learning classification analyses, SVM models were trained using cross-validation procedures to prevent overfitting.

For statistics, while the functional connectivity between the thalamic nucleus and cortical ROIs was first Fisher’s z-transformed, we used the network-based statistic (NBS) to identify the connectivity significance (v1.2 release, https://www.nitrc.org/projects/nbs). NBS is a nonparametric statistical approach designed to address the multiple comparisons problem in graph-structured data analyses. This method provides weak control over the family-wise error rate when performing simultaneous univariate hypothesis tests across all connections within a graph72. According to the existing literature73,74, the selected number of permutations was 5000, the corrected p value was 0.05, and the statistic threshold was set as 3.

R project (version 4.2.2; http://www.r-project.org) was used for statistical analysis of local fluctuations. Comparisons of sample entropy and rolling SD between baseline and altered consciousness states were conducted using both the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Mann–Whitney U-test) and the Bayesian t-test with default effect size priors (Cauchy scale 0.707). Effect sizes (rank-biserial correlation r for Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Cliff’s Delta δ for Mann–Whitney U-test), 95% confidence intervals, and nonparametric permutation tests (n = 5000) were also computed for all statistical results. For DoC and sleep datasets, each containing three distinct consciousness states, multiple comparison corrections were implemented using false discovery rate (FDR, α = 0.05). Bayesian analyses were employed as complementary approaches to supplement the frequentist statistical framework. In the Bayesian statistical results, the two-tailed Bayes factor BF10 was calculated, which quantifies the relative probability of the observed data (i.e., BF10 is equal to p(data |hypotheses1)/p(data|hypotheses0)). Previous studies showed that BF for different test statistics falls within the range between 2.4 and 3.4 when p equals 0.0575. An BF10 value between 3 and 10 indicates moderate evidence in favor of the alternative hypotheses (H1)76. Therefore, we select BF10 = 3 as the significance threshold, which means that the alternative hypothesis (H1: there is an effect) is three times more likely than the null hypothesis (H0: there is no effect), where: BF₁₀ <3: Anecdotal evidence for H₁;3≤ BF₁₀ <10: Moderate evidence for H₁;BF₁₀ ≥10: Strong evidence for H₁.

To analyze the coupling between thalamocortical functional connectivity and local fluctuations, thalamocortical functional connectivity in each thalamic nucleus were first averaged. Spearman correlation analyses were then performed between the average functional connectivity strength and both sample entropy and rolling SD, thereby quantifying the degree of coupling between them.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The time series data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to the execution of an appropriate data sharing agreement. Interested researchers must sign a data sharing agreement that ensures compliance with ethical guidelines, data protection regulations, and appropriate use of the data for scientific research purposes before access can be granted (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16742865)77.

Code availability

The code, computational, and statistical results have been uploaded to (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17204881)78. ROI parcellation can be obtained by contacting the authors of the sources cited in this paper. The following publicly available tools were utilized for data preprocessing and analysis: fMRIPrep (https://fmriprep.org/en/25.0.0/, version 25.0.0); FSL (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl, version 6.0.7); EntropyHub (https://github.com/MattWillFlood/EntropyHub, version 2.0); scikit-learn (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/, version 1.7.2); NBS (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/nbs/, version 1.2); R project (https://www.r-project.org/, version 4.5.0).

References

Laureys, S. The neural correlate of (un) awareness: lessons from the vegetative state. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 556–559 (2005).

Lee, M. et al. Quantifying arousal and awareness in altered states of consciousness using interpretable deep learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 1064 (2022).

Han, J. et al. The neural correlates of arousal: ventral posterolateral nucleus-global transient co-activation. Cell Rep. 43, 113633 (2024).

Vaitl, D. et al. Psychobiology of altered states of consciousness. Psychol. Conscious. 1, 2–47 (2013).

Jiang-Xie, L.-F. et al. A common neuroendocrine substrate for diverse general anesthetics and sleep. Neuron 102, 1053–1065.e1054 (2019).

Bernat, J. L. Questions remaining about the minimally conscious state. Neurology 58, 337–338 (2002).

Girardeau, G. & Lopes-dos-Santos, V. Brain neural patterns and the memory function of sleep. Science 374, 560–564 (2021).

Hwang, K., Bertolero, M. A., Liu, W. B. & D’Esposito, M. The human thalamus is an integrative hub for functional brain networks. J. Neurosci. 37, 5594–5607 (2017).

Baluch, F. & Itti, L. Mechanisms of top-down attention. Trends Neurosci. 34, 210–224 (2011).

Dobrushina, O. R. et al. Sensory integration in interoception: Interplay between top-down and bottom-up processing. Cortex 144, 185–197 (2021).

Malekmohammadi, M., Price, C. M., Hudson, A. E., DiCesare, J. A. & Pouratian, N. Propofol-induced loss of consciousness is associated with a decrease in thalamocortical connectivity in humans. Brain 142, 2288–2302 (2019).

Ranft, A. et al. Neural correlates of sevoflurane-induced unconsciousness identified by simultaneous functional magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography. Anesthesiology 125, 861 (2016).

Hannawi, Y., Lindquist, M. A., Caffo, B. S., Sair, H. I. & Stevens, R. D. Resting brain activity in disorders of consciousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 84, 1272–1280 (2015).

Thibaut, A. et al. Metabolic activity in external and internal awareness networks in severely brain-damaged patients. J. Rehabil. Med. 44, 487–494 (2012).

Zheng, Z. S., Reggente, N., Lutkenhoff, E., Owen, A. M. & Monti, M. M. Disentangling disorders of consciousness: Insights from diffusion tensor imaging and machine learning. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38, 431–443 (2017).

Brown, R. E., Basheer, R., McKenna, J. T., Strecker, R. E. & McCarley, R. W. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1087–1187(2012).

Ren, S. et al. The paraventricular thalamus is a critical thalamic area for wakefulness. Science 362, 429–434 (2018).

Afrasiabi, M. et al. Consciousness depends on integration between parietal cortex, striatum, and thalamus. Cell Syst. 12, 363–373.e311 (2021).

Luppi, A. I. et al. Local orchestration of distributed functional patterns supporting loss and restoration of consciousness in the primate brain. Nat. Commun. 15, 2171 (2024).

Nakajima, M. & Halassa, M. M. Thalamic control of functional cortical connectivity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 44, 127–131 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. Interindividual signatures of fMRI temporal fluctuations. Cereb. Cortex 31, 4450–4463 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Decoupled temporal variability and signal synchronization of spontaneous brain activity in loss of consciousness: an fMRI study in anesthesia. Neuroimage 124, 693–703 (2016).

Omidvarnia, A., Zalesky, A., Van De Ville, D., Jackson, G. D. & Pedersen, M. Temporal complexity of fMRI is reproducible and correlates with higher order cognition. Neuroimage 230, 117760 (2021).

Saranathan, M., Iglehart, C., Monti, M., Tourdias, T. & Rutt, B. In vivo high-resolution structural MRI-based atlas of human thalamic nuclei. Sci. Data 8, 275 (2021).

Yeo, B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Saalmann, Y. B., Pinsk, M. A., Wang, L., Li, X. & Kastner, S. The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science 337, 753–756 (2012).

Ward, L. M. The thalamus: gateway to the mind. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 4, 609–622 (2013).

Simpson, T. et al. Effect of propofol anaesthesia on the event-related potential mismatch negativity and the auditory-evoked potential N1. Br. J. Anaesth. 89, 382–388 (2002).

Heinke, W. et al. Sequential effects of increasing propofol sedation on frontal and temporal cortices as indexed by auditory event-related potentials. Anesthesiology 100, 617–625 (2004).

Palanca, B. J. A. et al. Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging correlates of sevoflurane-induced unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 123, 346 (2015).

Palanca, B., Avidan, M. & Mashour, G. Human neural correlates of sevoflurane-induced unconsciousness. Br. J. Anaesth. 119, 573–582 (2017).

Charyasz, E. et al. Functional mapping of sensorimotor activation in the human thalamus at 9.4 Tesla. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1116002 (2023).

Bolkan, S. S. et al. Thalamic projections sustain prefrontal activity during working memory maintenance. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 987–996 (2017).

Stender, J. et al. Quantitative rates of brain glucose metabolism distinguish minimally conscious from vegetative state patients. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35, 58–65 (2015).

Hale, J. R. et al. Altered thalamocortical and intra-thalamic functional connectivity during light sleep compared with wake. Neuroimage 125, 657–667 (2016).

Rektor, I., Kanovsky, P., Bares, M., Louvel, J. & Lamarche, M. Event-related potentials, CNV, readiness potential, and movement accompanying potential recorded from posterior thalamus in human subjects. A SEEG study. Neurophysiol. Clin. 31, 253–261 (2001).

Gent, T. C., Bandarabadi, M., Herrera, C. G. & Adamantidis, A. R. Thalamic dual control of sleep and wakefulness. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 974–984 (2018).

Whyte, C. J., Redinbaugh, M. J., Shine, J. M. & Saalmann, Y. B. Thalamic contributions to the state and contents of consciousness. Neuron 112, 1611–1625 (2024).

Guedj, C. & Vuilleumier, P. Functional connectivity fingerprints of the human pulvinar: decoding its role in cognition. Neuroimage 221, 117162 (2020).

Ilyas, A., Pizarro, D., Romeo, A. K., Riley, K. O. & Pati, S. The centromedian nucleus: anatomy, physiology, and clinical implications. J. Clin. Neurosci. 63, 1–7 (2019).

Laureys, S., Owen, A. M. & Schiff, N. D. Brain function in coma, vegetative state, and related disorders. Lancet Neurol. 3, 537–546 (2004).

Giacino, J. T. et al. Comprehensive systematic review update summary: disorders of consciousness: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Neurology 91, 461–470 (2018).

Picchioni, D. et al. Decreased connectivity between the thalamus and the neocortex during human nonrapid eye movement sleep. Sleep 37, 387–397 (2014).

Magnin, M. et al. Thalamic deactivation at sleep onset precedes that of the cerebral cortex in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3829–3833 (2010).

Akeju, O. et al. Disruption of thalamic functional connectivity is a neural correlate of dexmedetomidine-induced unconsciousness. Elife 3, e04499 (2014).

Gentet, L. J. & Ulrich, D. Strong, reliable and precise synaptic connections between thalamic relay cells and neurones of the nucleus reticularis in juvenile rats. J. Physiol. 546, 801–811 (2003).

Kumar, V. J., Beckmann, C. F., Scheffler, K. & Grodd, W. Relay and higher-order thalamic nuclei show an intertwined functional association with cortical-networks. Commun. Biol. 5, 1187 (2022).

Weiner, V. S. et al. Propofol disrupts alpha dynamics in functionally distinct thalamocortical networks during loss of consciousness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2207831120 (2023).

Miao, Y., Zhang, Y., Wan, H., Chen, L. & Wang, F. GABA-receptor agonist, propofol inhibits invasion of colon carcinoma cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 64, 583–588 (2010).

Mapelli, J. et al. The effects of the general anesthetic sevoflurane on neurotransmission: an experimental and computational study. Sci. Rep. 11, 4335 (2021).

McFarland, N. R. & Haber, S. N. Thalamic relay nuclei of the basal ganglia form both reciprocal and nonreciprocal cortical connections, linking multiple frontal cortical areas. J. Neurosci. 22, 8117–8132 (2002).

Boly, M. et al. Cerebral processing of auditory and noxious stimuli in severely brain injured patients: differences between VS and MCS. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 15, 283–289 (2005).

Ge, F. et al. Chronic sleep fragmentation enhances habenula cholinergic neural activity. Mol. psychiatry 26, 941–954 (2021).

Aizawa, H., Cui, W., Tanaka, K. & Okamoto, H. Hyperactivation of the habenula as a link between depression and sleep disturbance. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 826 (2013).

Andrillon, T., Poulsen, A. T., Hansen, L. K., Léger, D. & Kouider, S. Neural markers of responsiveness to the environment in human sleep. J. Neurosci. 36, 6583–6596 (2016).

Saalmann, Y. B. Intralaminar and medial thalamic influence on cortical synchrony, information transmission and cognition. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8, 83 (2014).

Huang, Z., Mashour, G. A. & Hudetz, A. G. Propofol disrupts the functional core-matrix architecture of the thalamus in humans. Nat. Commun. 15, 7496 (2024).

Panda, R. et al. Disruption in structural–functional network repertoire and time-resolved subcortical fronto-temporoparietal connectivity in disorders of consciousness. Elife 11, e77462 (2022).

Panda, R. et al. Whole-brain analyses indicate the impairment of posterior integration and thalamo-frontotemporal broadcasting in disorders of consciousness. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 4352–4371 (2023).

Schiff, N. D. Recovery of consciousness after brain injury: a mesocircuit hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 33, 1–9 (2010).

Yang, Y. et al. Revolutionizing treatment for disorders of consciousness: a multidisciplinary review of advancements in deep brain stimulation. Mil. Med. Res. 11, 81 (2024).

Qin, X. et al. Differential brain activity in patients with disorders of consciousness: a 3-month rs-fMRI study using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation. Front. Neurol. 15, 1477596 (2024).

Gu, Y., Sainburg, L. E., Han, F. & Liu, X. Simultaneous EEG and functional MRI data during rest and sleep from humans. Data Brief. 48, 109059 (2023).

Gu, Y. et al. Simultaneous EEG and fMRI signals during sleep from humans. OpenNeuro. https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds003768.v1.0.12 (2025).

López-González, A. et al. Loss of consciousness reduces the stability of brain hubs and the heterogeneity of brain dynamics. Commun. Biol. 4, 1037 (2021).

Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111–116 (2019).

Abraham, A. et al. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front. Neuroinform. 8, 14 (2014).

Lu, F. et al. Distinct effects of global signal regression on brain activity during propofol and sevoflurane anesthesia. Front. Neurosci. 19, 1576535 (2025).

Wang, C., Ong, J. L., Patanaik, A., Zhou, J. & Chee, M. W. Spontaneous eyelid closures link vigilance fluctuation with fMRI dynamic connectivity states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9653–9658 (2016).

Richman, J. S. & Moorman, J. R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H2039–H2049 (2000).

Yentes, J. M. et al. The appropriate use of approximate entropy and sample entropy with short data sets. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 41, 349–365 (2013).

Zalesky, A., Fornito, A. & Bullmore, E. T. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage 53, 1197–1207 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. Functional connectivity evidence for state-independent executive function deficits in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 291, 76–82 (2021).

Chen, H., Wang, Y., Ji, T., Jiang, Y. & Zhou, X. H. Brain functional connectivity-based prediction of vagus nerve stimulation efficacy in pediatric pharmacoresistant epilepsy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 3259–3268 (2023).

Benjamin, D. J. et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 6–10 (2018).

Jeffreys, H. The Theory of Probability (Oxford Univ. Press, 1998).

Liang, Z. et al. Differential engagement of thalamic nuclei orchestrates consciousness states across anesthesia, sleep, and disorders of consciousness. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16742865 (2025).

Liang, Z. et al. Code and result for differential engagement of thalamic nuclei orchestrates consciousness states across anesthesia, sleep, and disorders of consciousness. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17204881 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Scientific and Technological Innovation 2030 (STI2030-Major Projects 2021ZD0204300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 62471428, 82430040, and 62103354), the S&T Program of Hebei (21372001D), and the Hebei Natural Science Foundation (F2022203081).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, F.L. and J.W.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, X.G. and L.Y.; data curation, T.L., X.Q., and X.C.; writing—original draft, F.L.; writing—review & editing, Z.L. and X.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Zirui Huang, Mohsen Afrasiabi, and Rajanikant Panda for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article