Abstract

During development, biological tissues acquire their shape and organization by integrating internal and external cues, with mechanics playing a central role. Mechanical forces steer cell behavior and coordination, giving rise to self-organized architectures that underlie organ formation. While biochemical drivers of differentiation are well characterized, the contribution of topology and physical forces remains less understood. Here, we disentangle the role of alignment, tensile stress, and differentiation in three dimensions. Using self-organized aggregates of C2C12 myoblasts exposed to controlled stretching, we find that cells assemble into multilayered, actin-oriented tissues in which mechanical forces direct long-range 3D organization and promote myogenesis. Differentiation concentrates at the tissue core and surface, coinciding with regions of elevated stress and high cellular order. Single-molecule fluorescent hybridization confirms the overlap between differentiation hotspots and zones of strong alignment. These findings demonstrate that 3D alignment is a prerequisite for myoblast differentiation, and that mechanical constraints significantly boost its efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Morphogenesis is a remarkable process because of its robustness across scales and conditions based on the integration of internal and external signals. Among these feedbacks, mechanical stimuli are of enormous importance for pattern emergence in multicellular systems and organisms1,2,3,4. These signals are transduced by cellular mechanosensors and give rise to macroscopic rearrangements, supracellular movements and complex self-organizing structures that are at the birth of early embryonic patterns5,6. Developmental processes depend on a wide range of forces that correlate with morphogen gradients7, but also with cell shape and local organization. How cells can work together as dynamic collective ensembles to achieve a proper organization and how an organism is shaped by mechanical forces during development are still crucial open questions.

The idea of “topological morphogens”8 is beginning to emerge, meaning that biological functions could arise from topological mechanisms that create reproducible and robust conditions to control them9,10,11,12. Indeed, topological similarities across scales can be found in nature. For example, the network of epithelial tubes providing transport within the body is reminiscent of intestinal arrangements and is related to folding and buckling processes13,14. Thus, development is actually based on a relatively small number of key processes that the variability of tissues and organisms may have hidden at first glance. Theories of out-of-equilibrium active matter provide a new general framework to study these phenomena in multicellular systems15,16. Dimensionality17, curvature18,19 and topological defects20,21,22 seem to be the main ingredients of the interplay between topology and biological function.

The emergence of a third dimension in cell monolayers is, for example, specifically related to defect dynamics at different scales and in different systems, whether for extrusions23 or for multicellular protrusions in confined myoblasts24. Conversely, we might wonder whether the emergence of a three-dimensional shape can help to organize cells and subsequently improve their differentiation. More generally, the role of orientational order and anisotropy in biological processes25 and in model cell monolayers26 is beginning to be taken into account in a more systematic way.

In addition, while biological systems are mostly three-dimensional, studies of 3D model tissues are still sparse, hampered by several obstacles. First, there is a lack of purely cellular minimal model systems that can be constrained in a controlled manner. 3D mechanical constraints are generally applied using 3D scaffolds. The presence of the scaffold adds complexity, as the topography of the biomaterials and their adhesion to the substrate need to be considered17. Secondly, increasing dimensionality opens up a wider range of possible configurations that may prove difficult to model. However, in nematic synthetic fluids, it gives rise to fascinating disclination loops reminiscent of topological defects in 2D27,28. In this context, myogenesis is of particular interest because muscle function is based on a multiscale architecture, from the actin and myosin filaments to the myotubes, syncytial cells that make up the muscle and support its contractility14. However, it is still unclear whether alignment is a prerequisite for differentiation, and the impact of mechanical stimulations present during myogenesis, such as bone extension and cyclic strain induced by motoneurons, remains unknown. In addition, deciphering the interplay between 3D tissue formation and differentiation may be a key challenge for tissue engineering applications29,30. Here, we address this issue by developing an approach based on self-organized purely cellular aggregates whose geometry is controlled using mechanical constraints. More specifically, we study how spindle-shaped C2C12 myoblast cells organize in 3D and differentiate in muscular cells when stretched. To this end, linear, uniaxial and high amplitude stretching is applied over a large tissue using a magnetic device initially designed to drive embryonic stem cell differentiation towards the cardiac pathway31. We show that C2C12 cells organize in an active tissue with a fascinating multilayered structure that drives actin orientation and muscle cell differentiation. Although the third dimension is of great importance in the orientation and the differentiation, applied mechanical forces are the one driving the long-range ordering of the 3D tissue and its subsequent differentiation. Furthermore, the surface of this model tissue emerges as a hotspot in differentiation. Using single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization, we demonstrate that the directional order correlates with the obtained differentiation pattern at the surface. The application of quantitative approaches proves to be powerful to characterize patterns and mechanosensitivity in these model tissues.

Results

Stretching myoblasts in a magnetic stretcher device

To generate cohesive and mechanically stimulable 3D model tissues presenting possible orientational order, we form multicellular aggregates of C2C12 myoblasts (of approximatively 105 cells) (Fig. 1a). C2C12 cells are mouse muscle precursor cells32, i.e. they can differentiate into myotubes after collective alignment, long-range orientation and fusion steps33,34,35. The cells are first labelled with superparamagnetic nanoparticles (NP) to give them magnetic properties36. Incorporation of citrated iron oxide NP37 does not alter the metabolic activity (Supplementary Fig. S1a) or differentiation potential of C2C12 cells (Supplementary Figs. S1b, c and S2b) and is therefore biocompatible. Magnetically labelled cells are equally distributed on two face-to-face magnetic microattractors forming two domes of non-cohesive cells that are brought into contact on day 0 (D0). One of the two attractors is mobile to stimulate and stretch the formed 3D aggregate (Fig. 1a). Maximal near the soft iron tips (in the range of a few pN per cell38,39) and null in the central part of the setup (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b), the magnetic forces are smaller by several orders of magnitude than the adhesion between cells once established, or the pulling forces that cells can exert which are in the nN to μN range40,41. They remain constant over the course of the experiment as the magnetization M is constant over 3 days (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Magnetic forces are therefore necessary to drive the cells between the two micromagnets and concentrate them. Thereafter, the displacement of the mobile micromagnet is used to apply uniform mechanical strain to the entire aggregate (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f).

a Schematic of the magnetic stretching system. A multicellular assembly of magnetic cells is supported by two micromagnets separated by a distance D. As one of the micromagnets is movable, the device imposes the mechanical stretching to the aggregate. b, c Schematics (b) and corresponding representative images (c) of the formation of a cohesive multicellular aggregate in the magnetic stretcher. First, 5 × 104 magnetic cells in suspension are placed on each micromagnet. The two pieces are then brought together and a cohesive aggregate is formed overnight. d, e Schematic (d) and representative images of the stretching of the multicellular aggregate (e) followed by maturation. f Representative 2-photon image of the stretched multicellular aggregate at a depth of 50 μm at day 2. Cells express Lifeact-GFP.

After 9 h in complete medium, a cohesive aggregate with a smooth surface is formed (Fig. 1e). The medium is then changed to differentiation medium (2% horse serum) on day 1 (D1). A linear uniaxial stretching (1 μm step every 3 min for 6 h) is started. The multicellular aggregate is then kept in the magnetic stretcher for 24–48 h (day 2 (D2) and day 3 (D3)), depending on the measurement performed (Fig. 1f).

The mechanical stimulation imposed by the magnetic stretcher is controllable. We chose to focus on a simple stimulation that recapitulates the primitive development of the muscle: uniaxial linear stretching, as cyclic mechanical strain induces potential myogenesis inhibition in 2D42,43. During embryogenesis, the development of human skeletal muscle is coordinated with skeletal development44,45 that influences not only muscle weight and length but also myofilament organisation. Our experimental conditions, 1 μm every 3 min, recapitulate these in vivo conditions (bone elongation is approximately 2 mm/week ≈ 0.6 μm every 3 min for human embryogenesis). We applied a maximum stretching of 30% to reproduce in vivo mechanical stimulation of muscle cells, which can contract and relax by up to 17% of their length to produce voluntary motion46, and which can experience higher stretch during myogenesis47. This strain value is also within the range imposed in hydrogel constructs in muscle tissue engineering43. The magnetic stretching device enables mechanical stresses to be applied to large tissues (approximately 400 μm high and 500 μm in diameter).

The displacement of the mobile micromagnet during stretching does not affect the magnetic forces as can be seen from the force profiles (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). The magnets thus act as clamps to hold the cohesive aggregate once formed in combination with cell adhesion to the glass slides. The magnetic stretcher imposes mechanical strain to the 3D multicellular aggregate by controlling the movement of the micromagnet, the resulting stretch is homogeneously distributed throughout the sample, except for the first two cell layers31 (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f). The magnetic stretcher stimulates mechanically and stretches the 3D structure (Fig. 1d–f) to drive cell alignment and differentiation. The selected speed is slow enough to allow cells to rearrange between each step48,49. The stretching rate was optimised to improve cell alignment while preventing potential tissue rupture.

Nuclear volume is a sensitive marker of cell stress24,50. In our experiment, we measure nuclear cell volume throughout the aggregate 24 h after stretching to track possible stress heterogeneities. No stress changes are observed in the stretching direction, except for a non-significant decrease in nuclear volume near the microtips (Supplementary Fig. S3g–i), in agreement with PIV studies of cell movements (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f). The two terminal parts could be subjected to slightly and not significantly higher stress due to the proximity of the magnets. However, the changes are much more drastic in the perpendicular direction. Nuclear volume changes are much more impressive in the radial direction; cells at the core of the aggregate have larger nuclei (Supplementary Fig. S3g–i) than cells at the periphery, a 35% increase in nuclear volume is observed.

Stretching aligns the cells

Actin, one of the major cellular proteins of the cytoskeleton, supports the overall structure of cells, and C2C12 cells are no exception. As early as D1, multicellular aggregates show a collective organization. Interestingly, the orientation of the actin filaments at the surface of the aggregates in the magnetic stretcher is tilted almost perpendicular to the orientation in the core of the aggregate at a depth of 50 μm and below (Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Movie 1). This multilayered structure evolves when a mechanical stimulus is applied.

a Schematic of the stretched aggregate to define the azimuthal angle θ with respect to the stretching axis z and the polar angle ϕ with respect to the depth imaging axis x. b Representative 2-photon images of actin filaments (LifeAct-GFP) in a C2C12 multicellular aggregate in the magnetic stretcher at 5 μm depth (left) and at 60 μm depth (right). Images were taken on D1 before stretching. Close to the surface, actin filaments (indicated by white arrows) are oriented with a tilt relative to the z stretching axis higher than 45°, whereas in the core of the aggregate they are parallel to the stretching axis. c Orientation of actin filaments (mean ± SD) as a function of depth x for the aggregate in the magnetic stretcher on D1 before stretching (N = 3 independent experiments) and for the aggregate in the magnetic stretcher on D2 after stretching (N = 4 independent experiments). d Left panels: representative images of C2C12 Lifeact-GFP CTL spheroids and stretched aggregates on D1 and D2 at approximately 50 μm depth. Actin is shown in green. Middle panels: corresponding images with filaments color-coded according to their projected orientation with respect to the stretching axis z for stretched aggregates and a reference axis for CTL spheroids indicated by a white arrow. Right panels: zoom in on the central region of the color-coded orientation map. e Stereoplot of the angular distribution of actin filaments measured between 0 and 120 μm depth for CTL spheroids and for the stretched aggregates at D1 and D2. A peak in the direction of stretching is observed for the stretched aggregates at D2. N = 5 independent experiments for CTL spheroids and N = 4 independent experiments for aggregates in the magnetic stretcher.

To assess the effect of stretching, actin filament orientation was imaged at D1 and D2 in aggregates formed in the magnetic stretcher and compared with control (CTL) spheroids that were formed simultaneously with the stretched aggregates by magnetic moulding38,51 and left free of mechanical constraints in parallel under the same conditions (Fig. 2d). Spheroids represent relaxed systems, with a mean radius of curvature that is similar to that of stretched aggregates (210 ± 20 μm at D1). The shape of the aggregate between the two micro-magnets resembles that of a capillary bridge. Indeed multicellular aggregates behave as viscoelastic fluids38,51. The capillary force exerted by a concave capillary bridge is always contractile. For a concave capillary bridge to exist, this force must be balanced by an external force applied to its two ends52. In the case of the magnetic stretcher, this counterbalancing force is due to the magnetic attraction of the micromagnets and their adhesion to the two plates. Therefore, the shape of the capillary bridge, and in particular the difference between the two principal radii of curvature53, is a clear indicator of the force exerted. Consequently, only the spheroids can correspond to a state with no applied force whereas stretched aggregates correspond to stretched structure with tensile forces.

In both CTL spheroids and stretched aggregates, the number and the length of the actin filaments increase between D1 and D2 (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. S4), but the filaments are much longer in the stretched condition. In addition, the orientation of the filaments aligns impressively with the direction of stretching when we look at the orientation projection maps (Fig. 2d), while no preferential orientation emerges in CTL spheroids. This result is even more striking when we quantify the three-dimensional orientation of the filaments over a 120 μm thick portion of the aggregate (allowing more than 10 cell layers to be imaged). We define both an azimuthal angle θ with respect to the stretching direction and a polar angle φ with respect to the viewing direction (Fig. 2a). If the filaments were arranged to form a helix, they would appear as a ring in the stereoplot, whereas if arranged parallel, a dot or a portion of a disk depending on the portion of the image sample would appear as can be observed from computed aggregates (Supplementary Fig. S5). On D1, small peaks are visible in stretched aggregates at θ equals to 90°, corresponding to tilted filaments at the surface (Fig. 2c, e) while the actin filament orientation is almost uniform in the CTL spheroids. At D2, we observe a remarkable peaked distribution for θ centred around 0° in the stretched aggregates (Fig. 2e) while no preferential orientation is observed in the CTL spheroids. This angular distribution of actin is maintained for up to 2 days, provided that the stretched structure remains intact (Supplementary Fig. S6). In stretched aggregates, elongated cells orient along the direction of stretch in the inner part of the aggregate, initially having a perpendicularly tilted orientation on the surface (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Movie 2) with an angle that decreases over time (Fig. 2c, e). The angle of tilt cells on the periphery at D2 does not exceed 35° with the stretching axis, and only extends 20 μm deep (Fig. 2c). The magnetic stretcher thus drives the 3D alignment of the actin filaments in the direction of stretching in the whole aggregate.

Stretching drives myogenesis

Actin orientation is not the only marker of muscle cell differentiation47. The expression of myogenic factors or the one of proteins required for muscle contractile function, are generally used to quantify the differentiation level. These proteins and factors have a temporal pattern of expression47. Early, intermediate and mature muscle specific differentiation markers can be distinguished54. Myogenesis is schematically regulated by myogenic factors from myogenic differentiation factor 1 (Myod1) and Myogenin (Myog) to myogenic factor 6 (Myf6)55. Moreover, myosin heavy chain isoforms (Myh), troponin (Tnnt) and creatinin kinase M-type (Ckm) are specific markers of mature muscle. To assess differentiation, the expression of specific myogenic genes: Myod1 (early differentiation factor), Myog (intermediate differentiation factor) and Myf6 (late differentiation factor) or Myh, Tnnt and Ckm (specific markers of mature muscle) was measured by quantitative RT-qPCR in stretched aggregates and compared with the expression levels in CTL spheroids at D1. The measurements showed an increase in all myogenic genes after 3 days of differentiation (Fig. 3a). This shows that a purely cellular 3D environment is suitable for myogenesis. The increase in mRNA expression levels even counteracts the slight decrease due to magnetic labelling observed in 2D at short time scales (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Furthermore, if there is an improvement in myogenesis in 3D, the most striking result is that this phenomenon is even enhanced by mechanical stimuli. Indeed, the mRNA expression levels of each myogenic gene are increased by stretch stimulation, with expression levels at least 1.4 times higher in stretched aggregates than in spheroids at day 3 especially for specific markers of mature muscle (Myh, Tnnt and Ckm). To confirm myogenic differentiation at the protein level, the expression of proteins required for muscle contractile function was also determined. Myogenic factor 6 (Myf6) and fast myosin heavy chain (Myh4) proteins were measured by Western blot analysis. After 3 days of differentiation in the stretched condition, expression of both Myh4 and Myf6 proteins was increased compared to the CTL spheroid at day 3 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S7). Immunofluorescence was used to further confirm the expression of mature muscle protein markers, MHC and the late myogenic protein Tnnt. MHC was observed in all cells of the stretched aggregate, at least on the surface of the structure (Fig. 3c), and was found to correlate with the presence of fused (polynucleated) cells and long actin filaments (>100 μm in length, exceeding the size of individual C2C12 cells) (Fig. 3d). Additionally, the level of troponin expression was significantly higher in stretched aggregates after three days of differentiation compared to CTL spheroids (Fig. 3e). Thus, physical stimuli (both dimensionality and mechanical constraints) enhance overall myogenesis, but how this couples with the multicellular architecture and its long-range orientational order remains to be elucidated.

a Myogenic marker expression levels, determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Relative mRNA expression levels are measured for CTL spheroids at D1 and D3, and for stretched aggregates at D3. RPLP0 was used as a housekeeping gene. At least N = 6 for CTL spheroids with 4 independent experiments, N = 4 to 8 in 4 to 8 independent experiments for stretched aggregates at D3 for each gene. Mean ± standard error on the mean (SEM) is indicated and each point indicates an independent experiment. Myod1, myogenic differentiation 1, Myog, myogenin, Myf6, myogenic factor 6, Tnnt, troponin T, Ckm, creatin kinase M-type, Myh, myosin heavy chain; mRNA, messenger RNA; D, day. b Western Blot of CTL spheroids at D1 and D3 and stretched aggregates at D3 for myosin heavy chain, MHC and myogenic factor 6, Myf6. α-tubulin is used as a loading protein control. c Representative confocal image of a stretched aggregate at D3. Immunostaining of MHC (red) is superimposed with nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. d Representative confocal image of a stretched aggregate at D2. Both F-actin (green) and nuclei (blue) are visible. Scale bar = 20 μm. One can notice long actin filaments and the presence of fused (multinucleated) cells. e Representative confocal images of a spheroid and stretched aggregates at D3. Immunostaining of troponin T protein (magenta) is superimposed with nuclei (cyan) in a transverse cryosection of a CTL spheroid (left), of a stretched aggregate (middle) and in a longitudinal cryosection of a stretched aggregate. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Spatially resolved muscle differentiation patterns under stretching constraints

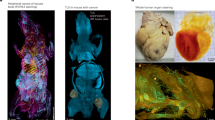

In the context of muscle differentiation, cell orientation has generally been associated with myoblast fusion and muscle differentiation, it is also a biomarker of muscle pathologies56. However, in the context of spindle cells, the emergence of differentiation is also generally correlated with topological defects21,24 either half integer or integer defects. C2C12 cells are spindle-shaped cells and for instance on circular patterns, integer topological defects have been identified as hotspots for myosin expression24. How cell organization can drive muscle differentiation therefore remains an open question. In stretched aggregates, topological defects are clearly identified at the surface: plus and minus half integer defects are present on the lateral surface of the aggregates, while their number decreases over time, whereas surface 2D projected defects accumulate in the regions in contact with the slides (Fig. 4). The expression of skeletal muscle troponin, a specific marker of mature muscle differentiation, was studied by imaging mRNA using single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridisation57,58,59 at D2 to look more closely at the pattern emergence (Myh1 is expressed in the same cells as Tnnt1 and gives the same differentiation pattern—Supplementary Fig. S8). mRNA expression is maximal on the lateral surface of the aggregates and at the central part of the aggregate (Fig. 4b). It reproduces the pattern observed in the immunofluorescence images of the Tnnt1 protein (Fig. 3e). This distribution correlates with the area of high surface 2D projected defects density (Fig. 4) but also for the lateral surface with the decrease of nuclear volume (Supplementary Fig. S3i). In the central part of the aggregate, the surface 2D projected defects are actually resolved in 3D, creating a well oriented region along the stretching axis where differentiation is important (Fig. 5e). On the surface of the aggregate, multilayering actually limits the possibility to resolve the defects in 3D.

a 3D Reconstruction from confocal images of stretched aggregates. Actin filaments are made visible using SiR-actin labelling. Topological defects are highlighted in blue (half integer defects) and in red (integer defect). Scale bar = 100 μm. b Representative confocal image of troponin T expression (magenta) superimposed with contour integration of actin filaments labelled with phalloidin (grey). The section corresponds to the attached part of the aggregate. Scale bar = 100 μm.

a Representative confocal images of sections of a spheroid and a stretched aggregate (D2). First row: projection of actin filaments (red) at the surface, local orientation of the filaments and the extracted coherency are shown from left to right. Second row: nuclei labelled with DAPI (blue) and mRNA FISH signals for Tnnt1 (cyan) are visible and superimposed. Scale bars = 100 μm. b Zoom of two specific areas of the surface of the stretched aggregate with either high (1) or low (2) ordered actin structure. Scale bars represent 20 μm. c Ratio of Tnnt1 positive cells as a function of the local amplitude of the coherency of both stretched aggregates (green) and spheroids (orange). Linear fits are obtained for each data sets and the one for stretched aggregate is superimposed with the corresponding color. For stretched aggregates, χ2 = 0.6. N = 5 different aggregates were studied for each case.

Together with the orientation map, mRNA expression shows that not only the core of the aggregate but also the interfaces are key regions for differentiation. We therefore focus on the surface region of the aggregates to explore the interplay between actin organisation as a marker of cell order and differentiation. By performing conformal projections of curved interfaces for both actin structures and mRNA expression (to preserve angles and thus orientational order between actin filaments) (Supplementary Fig. S9), the tilted structure of actin filaments on the surface of stretched aggregates at D2 is imaged. The tilt angle with respect to the stretching axis is distributed from 0 to 40∘ depending on the experiment and the position over the aggregate. Again, multicellular spheroids show shorter actin filaments and are more disordered (Fig. 5a) than stretched aggregates. Unsurprisingly, Tnnt1 mRNA expression in stretched aggregate is much higher than in CTL spheroids. To quantify actin local alignment, we introduce a coherency map (Fig. 5a-c). Coherency is the local amplitude of the nematic order parameter defined as \(S=\frac{1}{2}\langle 3{{{\rm{cos}}}}^{2}(\alpha )-1\rangle\) where α is the angle between filaments and the director, it equals 1 if the filaments are perfectly aligned and equals 0 in disordered orientation. By dividing the projected lateral surface into 50 μm long squares (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Fig. S9), we examined the fraction of cells expressing Tnnt1 in correlation with the mean amplitude of the nematic order parameter S (Fig. 5c). Overall, the more aligned the actin filaments, the greater the number of myoblasts entering muscle differentiation for stretched aggregates. While an identical trend can be seen in the case of spheroids, in which no mechanical stress is applied (the effect is difficult to see because both the number of cells expressing troponin is very low and actin alignment has a lower order parameter), the effect is obvious in the case of stretched aggregates. In the case of the stretched aggregates, a high slope of the linear fit is measured with a larger χ2 value around 0.6 (to compare to a χ2 value smaller than 0.1 for CTL spheroids). This indicates a high mechanosensitivity under constraint in these precursor muscle tissues.

Discussion

The use of magnetically labelled cells allows the formation of cohesive multicellular structures that can be manipulated using micromagnets. Magnetically labelled cells are then both the building blocks of minimal model micro-tissues and the force actuators in the tissue, the global force on the tissue is mediated by intercellular adhesions. These 3D tissues can be stretched at will as the micromagnets act as clamps that are able to sustain the tissue at both ends, distributing the stretch almost uniformly throughout the volume31 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S3d–f). However the surface of the aggregate and the parts closer to the micromagnets are slightly more tensile. The tensile forces localized at the surface of the elongated tissue can be deduced from nuclear volume changes as nucleus are highly sensitive to local changes (Supplementary Fig. S3g–i); their distribution is reminiscent of the one observed in embryos60.

Applied to spindle-shaped cells such as mouse muscle precursor cells C2C12, this model mechanical stretcher gives rise to complex self-organizing structures. Actin organization supports the cell and is a key element of its cytoskeleton. In addition, as myoblasts differentiate, supracellular actin fibres align with the body axis of the aligned muscle cells. So given the nematic properties of actin and its constitutive relationship with muscle structure21, multicellular organization is seen from actin observation. First, cell layering occurs in these 3D systems when they form. Surface effects have previously been observed in multicellular spheroids51 or embryos61 and have been associated with differential adhesion. In spheroids, differential cell tension and adhesion tends to flatten cells at the periphery with long actin filaments, while cells in the centre are rounder presenting cortical actin51. In contrast, in stretched multicellular aggregates, cells are all elongated. The overall structure of the actin filaments is not modified from the surface to the core but their global orientation twists from the surface, where it is tilted relative to the stretching axis, to the core, where it is not.

A multilayered organization of spindle-shaped cells has already been observed in organs and is tissue specific62: whereas corneal cells show no correlation between successive layers, muscles have perpendicular crisscross layering21,63. This crisscross layerings can also be observed in vitro in multilayered systems64,65. In muscle, these organizations persist for complex functions that may actuate organ formation66. In our model system driven by external forces, the structure obtained one day after 3D myoblast tissue formation recapitulates this tilted organization (Fig. 2b, c) observed in vivo. However, it is gradually modified by the application of external forces and subsequent rearrangements to provide a more globally oriented structure (Fig. 2e) by decreasing the tilt angle at the surface (Fig. 2c). This self-organisation specific to muscle is necessary for the normal development of its three-dimensional architecture64. The still persistent tilt at the end of maturation could also be reminiscent of the one observed for cells covering polymer capillary bridges18 except that, in our case, no chirality is noticed. The tilt angle measured at around 35° after maturation is close to that obtained for preosteoblastic cells deposited on PDMS structures18 (around 30°). This angle was found to be independant of capillary bridge shape in the case of PDMS substrate. Despite the shapes of the PDMS and cellular capillary bridges diverging, as C2C12 tissue has a higher surface tension (100 mN/m)51 than that of PDMS (20 mN/m), this angle appears to be identical in the stretched aggregates. Consequently, similar factors can be envisaged to explain this tilt. Tension and alignment to the local straight directions (as if cells would minimize their free energy by aligning with straight direction) are the most important factors. In addition, surface tension may explain the observed multilayering. If not fully explained, this configuration is like in the in vivo systems, it forms prior to muscle fibers orientation66.

In CTL spheroids, cells experience the same differentiation medium and could be driven towards the myogenic pathway. However, while actin filaments length increases, global random organization persists. External mechanical forces are the actuators of cell alignment, they tend to elongate the actin filaments and the cells and orient them in the direction of stretch. C2C12 cells are well described as nematic objects67, meaning that they tend to minimise possible bend and splay in 3D and thus align with each others23,68,69. Elastic constants known as Frank-Oseen parameters can describe this trends to avoid orientation change and the subsequent orientation order in these type of liquid crystals-like systems. However, interface regions with glass slides tend to align cells parallel to the slides, potentially creating a tilt that is eventually gradually resolved depending on the nematic interaction and the actual Frank-Oseen elastic parameters, which may change during differentiation. Indeed, while confluent myoblasts show numerous defects and changes in orientation, myotube formation reduces this type of events and shows long-range ordering in 2D.

Mechanical stretch not only drives the actin network cell alignment but it also enhances differentiation to mature muscle. Looking at both early (Myod1), intermediate (Myog) and late (Myf6) factors of myogenesis70 as well as mature muscle specific markers (Myh, Tnnt, Ckm), if 3D conditions are sufficient to induce muscle differentiation (Fig. 3a), differentiation is greatly improved by mechanical stretching, especially for mature muscle specific markers as shown for the troponin isoforms and myosin heavy chain by RT-qPCR, Western Blot and immunofluorescence protein staining. Contrary to scaffold approaches71, purely cellular 3D culture conditions actually enhance muscle cell differentiation compared to 2D culture conditions. Upregulation levels obtained two days after differentiation medium addition and linear stretching are comparable to those obtained after 7 days of differentiation on 2D slides (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, in the case of stretched aggregates, a microtissue is obtained, which means that its geometry is closer to that found in vivo. Muscle differentiation has a multilevel interplay72. Cell elongation and orientation33 seem to play key roles in fusion and differentiation processes70. Mechanical stretching by inducing both orientation and elongation accelerate this process as already observed on 2D substrates73,74,75,76,77 and in miniaturized systems30. During myogenesis, mechanical forces and the actomyosin cytoskeleton play crucial roles78. Myotubes attach themselves to tendons and undergo high tension in the form of tensile forces. Actin then transitions from a disordered state to an ordered state in the manner of an isotropic, nematic transition79. Our experiment reproduced this process of mechanically controlled self-organisation using myoblasts meaning not fully differentiated cells, which also transition from a randomly distributed state in the absence of applied forces to a highly oriented state in the presence of stretching.

Protein and mRNA imaging point at two main hotspots for differentiation, in addition to the central part of the aggregate, that are correlated with higher tensile forces (as extracted from nuclear size analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3i)) and higher defect density: first, the region in contact closer to the magnet and second the lateral surface of the stretched aggregates. The regions of the stretched aggregate close to the micromagnets are high surface 2D projected defect density regions situated at the central part of the stretched aggregates that exhibit a high differentiation level. Such a correlation has already been observed in confined C2C12 patterns24. In numerous studies starting from cell monolayers, the emergence of a third dimension is specifically linked to the dynamics of topological defects at different scales and in different systems from epithelium monolayers to Hydra morphogenesis21,23,80. For nematic objects and on deformable substrates, depending on the nematic elastic constants and the boundary conditions, the emergence of disclinations is accompanied by deformation of the surface81. For example, shape-changing vesicles encapsulating a microtubule-kinesin film form fibrillar protrusions to relieve the stress arising from half-integer defects82. This recapitulates the mechanisms involved in the growth and regeneration of Hydra tentacles83. In addition, Hydra head regeneration depends on integer topological defects63, as does the formation of multicellular protrusions in confined myoblasts24 or germ band extension in Drosophila84. In stretched aggregates, defects relieve the stress induced by boundary effects due to cells parallel to the glass slide at the interface and create a cell structure parallel to the stretching direction in the center that correlates with high differentiation (Figs. 3e and 4).

In addition, the lateral surfaces show higher differentiation. In this region, specific surface tension forces are known to play a role in embryonic morphogenesis60. Similarly, in stretched aggregates, surface cells experience maximum tension due to stretching related either to direct mechanical stretching and imposed boundary conditions (Supplementary Fig. S3g–i), which may explain their privileged differentiation. Mechanical constraints therefore drive the differentiation process. Furthermore, in this region, the differentiation level is associated with a high local orientational order. It reproduces the results obtained in myoblast-derived monolayers85. Comet-like defects are observed on these 3D structures and apply compressive stress on the structure77 which drives cell alignment. Early differentiation is located in these aligned regions. No significant correlation was observed with local mean curvature (Supplementary Fig. S8c) except for a slight non-significant tendency to favour areas of low curvature18,86. But if this tendency is observed both in spheroids and in stretched aggregates, the sensitivity associated with it, that is, the degree of correlation and the subsequent differentiation level obtained at a given order range, is higher when the aggregate is mechanically stimulated (Fig. 5c).

This study illustrates the complex interplay between physical cues and the emergence of differentiation maps in a 3D purely cellular complex system. It recapitulates the main features of myogenic processes and highlights the impact of mechanical constraints on the resulting structure but also on the sensitivity of the process. Indeed, mechanical constraints drive both cell alignment and actin orientation, but also a higher subsequent differentiation in long-range oriented regions. The ability of this tool to drive the formation of complex structures highlights the importance of linking cell signaling with cell organization. Mechanically-induced spatial reorganization modifies the local signals that each cell receives in a tissue, leading to the emergence of differentiation patterns. Mechanical stimuli enable the rational assembly of multicellular architectures and their potential remodeling. Combined with the modularity of synthetic cell adhesions87,88, this approach should potentially offer valuable insights into the dynamics of complex systems and facilitate the engineering of multi-layered structures. Overall, the mechanical stimulation of purely cellular 3D tissues provides powerful capabilities for cell and tissue engineering, as well as for the systematic study of multicellular organization. Additionally, the aim of scaffold-free cell therapies is to develop three-dimensional, organ-specific tissue substitutes in vitro by exploiting the natural ability of cells to form organised tissues by recapitulating developmental processes89,90. This ability surpasses that of artificial devices attempting to replicate the architecture of the extracellular matrix, and may be of interest to biorobotics91. However, the disadvantage of these scaffold-free classical methods is that they generally do not allow the use of stimuli, particularly mechanical stimuli, despite their importance in scaffolded systems92 as myobundles93,94. The magnetic stretcher enables this type of stimulation to be added and its impact to be investigated. It holds the potential to be used in the context of co-cultures and further physical stimulations for instance using optogenetically stimulated cells95. Our study also sheds light on the dynamics of complex systems and nematic tissues, demonstrating its potential to engineer customized self-organizing tissues or materials. The emerging understanding of morphogenesis through topology not only solves a key puzzle in biology, but also provides a mechanistic framework for future approaches to tissue engineering by highlighting processes with high robustness.

Methods

Cell culture and cell line construction (C2C12 Lifeact-GFP)

C2C12 cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1772). The C2C12 Lifeact-GFP stable cell line was constructed by transfecting the cells with a Lifeact-GFP Puromycin plasmid (pLVX-LifeAct-GFPtag2, gift from Sylvie Coscoy) using Lipofectamine3000 reagents (L3000001, Invitrogen). Cells were selected with puromycin and sorted by FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting FACS Aria Fusion, BD Biosciences). The clone selected presented a similar differentiation phenotype to C2C12 wild-type cells. C2C12 Lifeact-GFP cells were cultured in complete medium corresponding to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco), supplemented with 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin (P/S, Gibco), 2 μg/mL puromycin (P7255, Sigma) and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco).

Citrated iron oxide nanoparticles

Maghemite superparamagnetic citrated iron oxide nanoparticles (γ-Fe2O3) were obtained by alkaline coprecipitation of Fe(II) chloride and Fe(III) chloride according to Massart’s procedure96 followed by an oxidation thanks to the addition of boiling iron nitrate and finally the addition of sodium citrate. The adsorption of citrate anions to the NP ensures the electrostatic stability of the suspension. The resulting solution is composed of NP of about 8 nm diameter.

Cell labelling

C2C12 cells were magnetically labelled by an incubation with a solution of iron oxide nanoparticles at [Fe] = 1–2 mM and 5 mM citrate in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) for 30 min leading to an uptake of about 3 pg of iron per cell (measured by magnetophoresis). NP are incorporated through the endocytosis pathway and are stored in the endosomes as described in ref. 36. No influence of the iron oxide NP uptake was observed on the cell viability, the metabolic activity, or the ability of various cell types to differentiate31,97,98.

The magnetization of the multicellular aggregates stays almost constant during 3 days, evidencing that NP are not eliminated from cells (Fig. S3c).

Metabolic activity

Cell metabolic activity (Supplementary Fig. S1) was quantified thanks to a fluorescent resazurin-based assay (TOX8-1KT, Sigma-Aldrich). The assay was performed 2 h (D0) or 24 h after nanoparticle uptake (D1). The resazurin-based solution was incubated 2 h at 1:10 in DMEM (without phenol red) according to the supplier’s protocol. Fluorescence was measured for each condition with a plate reader (Enspire, Perkin Elmer) with an excitation wavelength at 560 nm and an emission wavelength at 590 nm in a 96-well plate.

Immunofluorescence analysis on 2D samples

Cells in 2D were fixed for 15–20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature (RT). They were then permeabilized 15–20 min in 0.1% Triton X-100 at RT and non-specific interactions were prevented by an incubation with 5% BSA (#05479, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at RT. Myh was labelled thanks to the MF20 mouse primary antibody (dilution 1:200 in 0.5% BSA D-PBS 1×, DSHB) incubated for 2 h at RT. Troponin was labelled using anti-troponin T antibody (mouse monoclonal, SAB4200717, Sigma, dilution 1:200 in 0.5% BSA D-PBS 1×, DSHB). Cells were then incubated for 2 h at RT with a goat anti-mouse Atto550 antibody (dilution 1:500 in 0.5% BSA D-PBS 1×, 43394, Sigma). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (dilution 1:1000 in D-PBS 1×, H3570, Invitrogen) for 15–20 min at RT. Images were obtained by confocal microscopy with the LSM 780 Zeiss microscope equipped with a 20× water immersion objective (W Plan-Apochromat 20×/1.0 DIC, Zeiss). Represented images correspond to Z-projections on 8–10 μm.

RT-qPCR measurements

Total RNA was extracted from multicellular aggregates with the NucleoSpin RNA Kit (740955, Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For aggregate disruption, each aggregate was rinsed with D-PBS 1× and resuspended in 350 μL lysis buffer and disrupted with about 30 one-second pulses performed with a Biovortexer and a spiral pestle (918034 and 918044, Biospec). Complementary DNAs were obtained with the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (18064022, Thermofischer Scientific) and random hexamers (C1181, Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Green Master Mix (4309155, Thermofischer Scientific). The RPLP0 gene coding for the 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 was used as a reference transcript. The primer sequences used for RPLP0, Myod1, Myog, Myf6, Tnnt1, Tnnt3, Myh1, Myh3, Myh4 and Ckm are presented in Fig. S2a.

Protein extraction and Western Blot

For protein extraction, multicellular aggregates were rinsed with D-PBS 1× and put in an ice cold solution of 30 mM Tris-EDTA (pH adjusted with concentrated HCl to 7.4), 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 1× anti-phosphatase cocktail (Roche, 04906837001) and 1× anti-protease cocktail (Roche, 11836170001). Multicellular aggregates were disrupted using lysing beads (Precellys lysing kit, P000912-LYSK0, Bertin) and the Precellys24 tissue homogenizer device (Bertin). Samples were then left for 30 min in ice and centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000g and 4 °C. The supernatant was retrieved and protein concentration was quantified by Bradford assay.

The multicellular aggregate protein extracts were then used for Western Blot analysis. Proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide 4–20% gels and transferred on PVDF membranes. After rinsing the membranes with TBS-Tween 20 buffer (TBST), the membranes were blocked for 1 h in the EveryBlot blocking buffer (12010020, Biorad) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies rabbit anti-Myf6 (sc-301, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse myosin heavy chain (Myh) (MF 20, DSHB) both diluted at 1:1000 with 5% BSA. Membranes were then washed 3 times with TBST and incubated for 1 h with the anti-mouse (#7076, Cell Signaling) or anti-rabbit (#7074, Cell Signaling) horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies diluted at 1:2000 in the Everyblot blocking buffer. Peroxidase activity was revealed using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent, RPN2232, Cytiva) and the Syngene PXi device (Ozyme). Alpha-tubulin was used as the loading control and immuno-probed with the mouse anti-alpha tubulin antibody (T5168, Sigma).

Biocompatibility of nanoparticles

The biocompatibility of citrated iron oxide NP incorporation for mouse muscle precursor cells C2C12 was carefully assessed by measuring the metabolic activity and the differentiation level.

Measurements on the metabolic activity of cells show no difference in comparison with control cells 2 h after NP incorporation at day 0 and at day 1 (Fig. S1a). Besides, differentiation tests were performed after NP incorporation showing no phenotypic difference on the myotubes formation. Supplementary Figure S1b shows representative images of cells after 7 days of differentiation. Both in the control condition and with the incorporation of NP at day 0, long myotubes are obtained. These elongated polynucleated cells express myosin heavy chain, a marker of myogenic differentiation involved in the contraction of functional muscular cells, in both control and NP conditions after 3 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S1c).

Finally, NP incorporation decreases slightly mRNA levels for all genes related to myogenic differentiation at day 1 after NP incorporation, probably due to the upregulation of genes involved in NP uptake and storage such as ferritin99. However, the same mRNA levels of the myogenic marker genes are recovered with or without NP incorporation for most genes at day 3 and for all genes at day 7 of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S2). In conclusion, NP uptake does not alter significantly the cell metabolic activity or the ability of cells to differentiate at medium (3 days) and long term (7 days).

Formation of C2C12 spheroids

C2C12 CTL spheroids were obtained as described in ref. 51. In summary, C2C12 cells grown in 2D and at 70−80% confluency were incubated for 30 min with a solution of NP at [Fe] = 2 mM supplemented with 5 mM citrate. After 2 h of incubation in complete medium, cells were trypsinized, centrifuged and resuspended in a minimal volume (a few hundreds of μL). Suspended cells where then attracted in spherical agarose molds of 1.2 mm diameter, previously coated for 30 min with an anti-adhesive rinsing solution (07010, Stemcell Technologies), with permanent magnets placed below each mold. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2, spheroids were removed from the molds by gentlye pipetting the surrounding medium.

The magnetic stretcher device

The magnetic stretcher device is composed of a tank with two identical 3D printed polymer holders (PA2200, polyamide) in which a permanent neodymium magnets (6 × 6 mm, Supermagnete) is inserted and put into contact with a soft iron tip of 400 μm diameter. Cells are deposited on each microtip protected by a 100 μm thick glass slide. One of the magnetic pieces is fixed while the second one can be moved thanks to a step-by-step motor (Z812B, Thorlabs) actuated by a controller (TDC001 or KDC101, Thorlabs). Temperature is regulated at 37 °C. A homemade cover was built to enable the displacement of the objective while keeping the box closed. The pH stability was ensured either by addition of 10 mM HEPES to the medium or a flow of 5% CO2 in the box (OkoLab controller). Simulations of the magnetic field and the magnetic field gradient between the two magnets are performed using the software COMSOL Multiphysics (additional module AC/DC). The volume magnetic force f applied to the cells is proportional to the magnetic field gradient, since \(\overrightarrow{f}=(\overrightarrow{M}\cdot \overrightarrow{\nabla })\overrightarrow{B}\), where \(\overrightarrow{M}\) is the volume magnetic moment and \(\overrightarrow{B}\) is the magnetic field.

Aggregate formation in the magnetic stretcher

After tank sterilization, the glass slides on each micromagnet are incubated with Matrigel (356234, Corning) diluted at 0.5 mg/mL in cold DMEM for 1 h at room temperature for coating. After rinsing, the tank is filled with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, 2.5 μg/mL Amphotericin B, 2 μg/mL puromycin and 1× anti-oxidant supplement (A1345, Sigma).

C2C12 cells are incubated for 30 min with a solution of NP at [Fe] = 1–2 mM supplemented with 5 mM citrate. After 2 h of incubation in complete medium, cells are resuspended at 5 million cells/mL in complete medium. Ten microlitres of suspended cell solution (equivalent to 50k cells) are deposited on each micromagnet forming a hemisphere of non cohesive cells. The two micromagnets are then approached at a distance of 350–400 μm as shown in Fig. 1d, e. After an overnight incubation, the tank medium is changed for the differentiation medium composed of DMEM with 2% HS, 1% P/S, 2.5 μg/mL Amphotericin B and 1× anti-oxidant supplement. A linear stretch at 1 μm every 3 min of the cohesive multicellular aggregate is started for 6 h and the mobile piece is reapproached of about 40 μm at the end of the stretching. The medium is changed with fresh differentiation medium every 24 h for the next 2 days.

Over 72 h, the nuclei retain their distinct shape and regular profile in all regions of the aggregate (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, non-apoptotic and non-hypoxic conditions were confirmed in C2C12 multicellular aggregates of similar sizes within 24 h through Caspase 3 and HIF alpha stainings51 and Caspase-3 (Sigma) staining reveals no signs of apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S10) after 3 days. C2C12 cells differentiate under starvation conditions, meaning their viability is unaffected by reduced access to nutrients.

Live bright field and 2-photon microscopy imaging

Bright field images were obtained with a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope and a 10× objective. Live fluorescence images were obtained through 2-photon microscopy using an SP8 Leica microscope coupled with an Insight DeepSee tunable laser. Acquisition were obtained at a wavelength of 980 nm with a 20× water immersion objective (HCX APO L 20×/1.00W, Leica).

Imaging of fixed 3D samples

CTL spheroids and stretched aggregates were fixed for 1 h at RT in 4% PFA. Stretched aggregates were fixed in situ then retrieved with a micropipette. For immunofluorescence on cryosections, aggregates were embedded in OCT (Optimal Cutting Compound, 361603E, VWR) for 1 h at RT, they were then frozen in iso-pentane (24872.260, VWR), cooled down in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −20 °C. In total, 6–10 μm cryosections were obtained (Leica CM1520).

For immunofluorescence, 3D samples were permeabilized and non-specific interactions were blocked by incubating the 3D samples in 5% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 for at least 4 h at RT. SPY555-actin (dilution 1:400) or SiR-actin (Spirochrome) (dilution 1:1000) or was incubated with the samples for at least 24 h in D-PBS 1×, 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X100 to ensure an optimal actin imaging. Myh was labelled thanks to the MF20 mouse primary antibody (dilution 1:100 in 0.5% BSA D-PBS 1×, DSHB and 0.1% Triton X100) incubated for 24 h at RT followed by a 24 h incubation at RT with a goat anti-mouse Atto550 antibody (dilution 1:500 in 0.5% BSA D-PBS 1×, 43394, Sigma and 0.1% Triton X100). Tnnt (Anti-Tnnt1 Abcam) was labelled using the same protocol. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (dilution 1:1000 in D-PBS, H3570, Invitrogen) for 24 h at RT. Samples were imaged by confocal microscopy thanks to the LSM 780 Zeiss microscope and with a 20× water immersion objective (W Plan-Apochromat 20×/1.0 DIC, Zeiss).

Actin filament orientation extraction

To obtain actin filament position and length, ridge detection filter was applied. Actin filament orientation was extracted thanks to Orientationpy code the derived 3D Python version of the ImageJ plug-in OrientationJ (Biomedical Imaging Group, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland)100 from either live 2-photon microscopy images or confocal images on fixed samples. Orientation of actin filaments was assessed from images located from 0 to 120 μm below the surface of the spheroid or the stretched aggregate.

The representative images for the orientation maps were obtained from ImageJ plugin OrientationJ with a gaussian gradient.

Single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization

mRNA FISH probes were purchased from ACDBio (Mm-Myh1-O2 539381, Mm-TnnT1-C3 466911). Fixation and labelling protocols were optimized from published protocols59,101. Briefly, multicellular aggregates were fixed in situ for 1 h, in a solution of 4% PFA, 0.25% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% Tween, 5 mM EGTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1:100 Alexa Fluor™ 488 phalloidin (Molecular Probes). After fixation, they were incubated in D-PBS with 1:100 Alexa Fluor™ 488 phalloidin (Molecular Probes), 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% BSA for 4 h to ensure optimal retention of cytoskeleton structures.

Probes were heated to 40 °C for 10 min. Samples were then incubated in Eppendorf tubes overnight (O/N) in probes diluted 1:50 in Probe Diluant (300041, ACDBio). The next morning, samples were washed 3× 15 min in wash buffer under agitation at RT (RNAscope Wash Buffer Reagents, ACDBio, 310091). Samples were incubated with each amplification solutions consecutively for 35 min at 40 °C and then washed 3× 5 min at RT in wash buffer. Samples were incubated in HRP-C1 for 20 min at 40 °C and then washed 3× 5 min at RT in wash buffer. Samples were incubated in TSA-570 (323272, ACDBio) or TSA-650 (323272, ACDBio) diluted 1:1500 in TSA buffer for 35 min at 40 °C and then washed 3× 5 min at RT in wash buffer.

Samples were incubated in HRP blocker for 20 min at 40 °C and then washed 3× 5 min at RT in wash buffer. Samples were stained in DAPI (solution from the RNAscope kit) for 5 min or O/N in 1:1000 Spy505 (Spirochrome) and then mounted in ProLong™ Gold (Invitrogen, P36930) in between two coverslips (thickness 1.5 mm, 22 mm × 22 mm) with double spacers (Thermo Scientific™ Gene Frame, 65 μL) between them.

Image analysis

To conformally project aggregates surfaces from 3D volumes, we used both the ImageJ plugin LocalZ projector and the Matlab Deproj application102 without noticing important changes as our samples are relatively flat over the 150 μm height of the observation. The projection is a conformal transformation that preserves the angles between objects and therefore the shapes (Supplementary Fig. S9).

The velocity field was extracted from time-resolved bright-field images using the PIVLab software package within Matlab103.

Nuclei detection was performed using a StarDist plugin trained for 3D nuclei detection. Coherency is extracted from ImageJ plugin OrientationJ in 2D images and from Python orientationpy plugin in 3D reconstruction (Supplementary Fig. S9). Coherency in Fig. 5 is calculated on the projected surface over a thickness of 7 μm (the height of the first cell layer). Line integral contour of cells was obtained using the Matlab dedicated function. Curvature was extracted from confocal fluorescence images using Matlab.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Statistical tests were performed with Mann–Whitney tests using the ranksum function in Matlab. Statistical significance is indicated using p-values (*, ** and *** correspond to p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) and ns indicates non-significant differences. Each N corresponds to an independent experiment that may contain several replicates. By replicating each experiment more than 4 times, we validate its reproductibility. All data were taken into account except if the stretched aggregate detached.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset supporting this article is available on Zenodo platform (at https://zenodo.org/records/17543835?). Other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hannezo, E. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Mechanochemical feedback loops in development and disease. Cell 178, 12–25 (2019).

Shahbazi, M. N. Mechanisms of human embryo development: from cell fate to tissue shape and back. Development 147, dev190629 (2020).

Lei, M. et al. The mechano-chemical circuit drives skin organoid self-organization. Proc. Natl. Am. Soc. PNAS 120, e2221982120 (2023).

Firmin, J. et al. Mechanics of human embryo compaction. Nature 629, 646–651 (2024).

Xiong, F. et al. Interplay of cell shape and division orientation promotes robust morphogenesis of developing epithelia. Cell 159, 415–427 (2014).

Zhu, M. & Zernicka-Goetz, M. Principles of self-organization of the mammalian embryo. Cell 183, 1467–1478 (2020).

Wang, Z., Marchetti, M. C. & Brauns, F. Patterning of morphogenetic anisotropy fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220167120 (2023).

Hoffmann, L. A., Carenza, L. N., Eckert, J. & Giomi, L. Theory of defect-mediated morphogenesis. Sci. Adv. 8, eabk2712 (2022).

Gibson, M. C., Patel, A. B., Nagpal, R. & Perrimon, N. The emergence of geometric order in proliferating metazoan epithelia. Nature 442, 1038–1041 (2006).

Gibson, W. T. et al. Control of the mitotic cleavage plane by local epithelial topology. Cell 144, 427–438 (2011).

Minc, N., Burgess, D. & Chang, F. Influence of cell geometry on division-plane positioning. Cell 144, 414–426 (2011).

Fischer, S. C., Bassel, G. W. & Kollmannsberger, P. Tissues as networks of cells: towards generative rules of complex organ development. J. R. Soc. Interface 20, 20230115 (2023).

Fouchard, J. et al. Curling of epithelial monolayers reveals coupling between active bending and tissue tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9377 (2020).

Wang, X., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, D., Vourc’h, T., Silberzan, P. & Barakat, A. I. Contractility-induced self-organization of smooth muscle cells: from multilayer cell sheets to dynamic three-dimensional clusters. Commun. Biol. 6, 262 (2023).

Marchetti, M. C. et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1143 (2013).

Metselaar, L., Yeomans, J. M. & Doostmohammadi, A. Topology and morphology of self-deforming active shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 208001 (2019).

Viswanathan, P. et al. 3d surface topology guides stem cell adhesion and differentiation. Biomaterials 52, 140–147 (2015).

Ehrig, S. et al. Surface tension determines tissue shape and growth kinetics. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav9394 (2019).

Tang, W. et al. Collective curvature sensing and fluidity in three-dimensional multicellular systems. Nat. Phys. 18, 1371–1378 (2022).

Kawaguchi, K., Kageyama, R. & Sano, M. Topological defects control collective dynamics in neural progenitor cell cultures. Nature 545, 327–331 (2017).

Maroudas-Sacks, Y. et al. Topological defects in the nematic order of actin fibres as organization centres of hydra morphogenesis. Nat. Phys. 17, 251–259 (2020).

Vafa, F. & Mahadevan, L. Active nematic defects and epithelial morphogenesis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 098102 (2022).

Saw, T. B. et al. Topological defects in epithelia govern cell death and extrusion. Nature 544, 212–216 (2017).

Guillamat, P., Blanch-Mercader, C., Pernollet, G., Kruse, K. & Roux, A. Integer topological defects organize stresses driving tissue morphogenesis. Nat. Mater. 21, 588–597 (2022).

Lefebvre, M. F., Claussen, N. H., Mitchell, N. P., Gustafson, H. J. & Streichan, S. J. Geometric control of myosin II orientation during axis elongation. Elife 12, e78787 (2023).

Turiv, T. et al. Topology control of human fibroblast cells monolayer by liquid crystal elastomer. Sci. Adv. 6, aaz6485 (2020).

Duclos, G. et al. Topological structure and dynamics of three-dimensional active nematics. Science 367, 1120–1124 (2020).

Alam, S. et al. Active fréedericksz transition in active nematic droplets. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041002 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Engineered skeletal muscles for disease modeling and drug discovery. Biomaterials 221, 119416 (2019).

Rose, N. et al. Bioengineering a miniaturized in vitro 3d myotube contraction monitoring chip to model muscular dystrophies. Biomaterials 293, 121935 (2020).

Du, V. et al. A 3d magnetic tissue stretcher for remote mechanical control of embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00543-2 (2017).

Yaffe, D. & Feldman, M. The formation of hybrid multinucleated muscle fibers from myoblasts of different genetic origin. Dev. Biol. 11, 300–317 (1965).

Fortier, M. et al. Rhoe controls myoblast alignment prior fusion through rhoa and rock. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1221–1231 (2008).

Gingras, J. et al. Controlling the orientation and synaptic differentiation of myotubes with micropatterned substrates. Biophys. J. 97, 2771–2779 (2009).

Wang, P.-Y., Yu, H.-T. & Tsai, W.-B. Modulation of alignment and differentiation of skeletal myoblasts by submicron ridges/grooves surface structure. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 106, 285–294 (2010).

Rivière, C. et al. Internal structure of magnetic endosomes. Eur. Phys. J. E 22, 1–10 (2007).

Wilhelm, C. & Gazeau, F. Universal cell labelling with anionic magnetic nanoparticles. Biomaterials 29, 3161–3174 (2008).

Mazuel, F. et al. Magnetic flattening of stem-cell spheroids indicates a size-dependent elastocapillary transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.114.098105 (2015).

Gemperle, J. et al. Live-cell magnetic manipulation of recycling endosomes reveals their direct effect on actin protrusions to promote invasive migration. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu6361 (2025).

Clarke, D. N. & Martin, A. C. Actin-based force generation and cell adhesion in tissue morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 31, R667–R680 (2021).

Pan, J. et al. Quantifying molecular- to cellular-level forces in living cells. J. Phys. D 54, 483001 (2021).

Kumar, A., Murphy, R., Robinson, P., Wei, L. & Boriek, A. M. Cyclic mechanical strain inhibits skeletal myogenesis through activation of focal adhesion kinase, rac-1 gtpase, and nf-kappab transcription factor. FASEB J. 18, 1524–35 (2004).

Pang, K. T. et al. Insight into muscle stem cell regeneration and mechanobiology. Stem Cell Res Ther. 14, 129 (2023).

Stewart, D. M. Regulation of Organ and Tissue Growth (Associated Press, New York, 1972).

Powell, C. A., Smiley, B. L., Mills, J. & Vandenburgh, H. H. Mechanical stimulation improves tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283, C1557–C1565 (2002).

van Donkelaar, C., Willems, P., Muijtjens, A. & Drost, M. Skeletal muscle transverse strain during isometric contraction at different lengths. J. Biomech. 32, 755–762 (1999).

Chal, J. & Pourquie, O. Making muscle: skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development 144, 2104–2122 (2017).

David, R. et al. Tissue cohesion and the mechanics of cell rearrangement. Development 141, 3672–3682 (2014).

Tlili, S. L., Graner, F. & Delanoë-Ayari, H. A microfluidic platform to investigate the role of mechanical constraints on tissue reorganization. Development 149, dev200774 (2022).

Hobson, C. M. et al. Correlating nuclear morphology and external force with combined atomic force microscopy and light sheet imaging separates roles of chromatin and lamin a/c in nuclear mechanics. Mol. Biol. Cell 31, 1651–1821 (2020).

Nagle, I. et al. The importance of intermediate filaments in the shape maintenance of myoblast model tissues. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.76409 (2022).

Petkov, P. V. & Radoev, B. P. Statics and dynamics of capillary bridges. Colloids Surf. A 460, 18–27 (2014).

Kralchevsky, P. A. & Nagayama, K. Chapter 11—Capillary Bridges and Capillary-Bridge Forces, vol. 10 of Studies in Interface Science (Elsevier, 2001).

Iberite, F., Gruppioni, E. & Ricotti, L. Skeletal muscle differentiation of human ipscs meets bioengineering strategies: perspectives and challenges. npj Regen. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-022-00216-9 (2022).

Yu, D. et al. Myogenic differentiation of stem cells for skeletal muscle regeneration. Stem Cells Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8884283 (2021).

Xu, B. et al. Nanotopography-responsive myotube alignment and orientation as a sensitive phenotypic biomarker for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biomaterials 183, 54–66 (2018).

Borrelli, C. & Moor, A. E. Single-molecule rna fish in whole-mount organoids. Methods Mol. Biol. 2171, 237–247 (2020).

Santos, M. D. et al. Single-nucleus rna-seq and fish identify coordinated transcriptional activity in mammalian myofibers. Nat. Commun. 11, 5102 (2020).

Hansen, C. L. & Pelegri, F. Methods for visualization of RNA and cytoskeletal elements in the early zebrafish embryo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2218, 219–244 (2021).

Krieg, M. et al. Tensile forces govern germ-layer organization in zebrafish. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 429–436 (2020).

Manning, M. L., Foty, R. A., Steinberg, M. S. & Schoetz, E.-M. Coaction of intercellular adhesion and cortical tension specifies tissue surface tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12517–12522 (2010).

Conrad, G. W., Hart, G. W. & Chen, Y. Differences in vitro between fibroblast-like cells from cornea, heart, and skin of embryonic chicks. J. Cell Sci. 26, 119–137 (1977).

Ravichandran, Y., Vogg, M., Kruse, K., Pearce, D. J. & Roux, A. Topology changes of the regenerating hydra define actin nematic defects as mechanical organizers of morphogenesis. BiorXiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.07.588499 (2024).

Takahashi, H., Shimizu, T., Nakayama, M., Yamato, M. & Okano, T. The use of anisotropic cell sheets to control orientation during the self-organization of 3d muscle tissue. Biomaterials 34, 7372–7380 (2013).

Sarkar, T. et al. Crisscross multilayering of cell sheets. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad034 (2023).

Huycke, T. R. et al. Genetic and mechanical regulation of intestinal smooth muscle development. Cell 179, 90–105 (2019).

Duclos, G. et al. Spontaneous shear flow in confined cellular nematics. Nat. Phys. 14, 728–732 (2018).

Doostmohammadi, A., Ignés-Mullol, J., Yeomans, J. M. & Sagués, F. Active nematics. Nat. Commun. 9, 3246 (2018).

Nejad, M. R. et al. Stress-shape misalignment in confluent cell layers. Nat. Commun. 15, 3628 (2024).

Ganassi, M. et al. Myogenin promotes myocyte fusion to balance fibre number and size. Nat. Commun. 9, 4232 (2018).

Tomasch, J. et al. Changes in elastic moduli of fibrin hydrogels within the myogenic range alter behavior of murine c2c12 and human c25 myoblasts differently. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 836520 (2022).

Petrany, M. J. & Millay, D. P. Cell fusion: merging membranes and making muscle. Trends Cell Biol. 29, 964–973 (2019).

Pennisi, C. P., Olesen, C. G., de Zee, M., Rasmussen, J. & Zachar, V. Uniaxial cyclic strain drives assembly and differentiation of skeletal myocytes. Tiss. Eng. Part A https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0089 (2011).

Ku, S. H., Lee, S. H. & Park, C. B. Synergic effects of nanofiber alignment and electroactivity on myoblast differentiation. Biomaterials 33, 6098–6104 (2012).

Collinsworth, A. M. et al. Orientation and length of mammalian skeletal myocytes in response to a unidirectional stretch. Cell Tissue Res. 302, 243–51 (2000).

Chan, A. H. P. et al. Combinatorial extracellular matrix cues with mechanical strain induce differential effects on myogenesis in vitro. Biomaterials 11, 5893–5907 (2023).

Toquin, Y. L. et al. Mechanical stresses govern myoblast fusion and myotube growth. BioRXiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.22.624831 (2024).

Kim, J. H., Jin, P., Duan, R. & Chen, E. H. Mechanisms of myoblast fusion during muscle development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 32, 162–170 (2015).

Lemke, S. B. & Schnorrer, F. Mechanical forces during muscle development. Mechan. Dev. 144, 92–101 (2017).

Duclos, G., Erlenkamper, C., Joanny, J.-F. & Silberzan, P. Topological defects in confined populations of spindle-shaped cells. Nat. Phys. 13, 58–62 (2017).

Pearce, D. J. G., Thibault, C., Chaboche, Q. & Blanch-Mercader, C. Passive defect driven morphogenesis in nematic membranes. BiorXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.16654 (2023).

Keber, F. C. et al. Topology and dynamics of active nematic vesicles. Science 345, 1135–1139 (2014).

Livshits, A. et al. Plasticity of body axis polarity in hydra regeneration under constraints. Sci. Rep. 12, 13368 (2022).

Nandi, S., Balse, A., Inamdar, M. M., Kumar, K. V. & Narasimha, M. Actomyosin cables position cell cohorts during drosophila germband retraction by entraining their morphodynamic and mechanical properties. BiorXiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.23.509113 (2022).

Skillin, N. P. et al. Stiffness anisotropy coordinates supracellular contractility driving long-range myotube-ecm alignment. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn0235 (2024).

Jana, S., Levengood, S. & Zhang, M. Anisotropic materials for skeletal-muscle-tissue engineering. Adv. Mater. 28, 10588–10612 (2016).

Toda, S., Blauch, L. R., Tang, S. K. Y., Morsut, L. & Lim, W. A. Programming self-organizing multicellular structures with synthetic cell-cell signaling. Science 361, 156–162 (2018).

Stevens, A. J. et al. Programming multicellular assembly with synthetic cell adhesion molecules. Nature 614, 144–152 (2023).

DuRaine, G. D., Brown, W. E., Hu, J. C. & Athanasiou, K. A. Emergence of scaffold-free approaches for tissue engineering musculoskeletal cartilages. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 43, 543–554 (2014).

Shahin-Shamsabadi, A. & Cappuccitti, J. In vivo-like scaffold-free 3d in vitro models of muscular dystrophies: The case for anchored cell sheet engineering in personalized medicine. Adv. Health Mater. 14, 2404465 (2024).

Cordelle, M. Z., Snelling, S. J. B. & Mouthuy, P.-A. Skeletal muscle tissue engineering: From tissue regeneration to biorobotics. Cyborg. Bionic Syst. 6, 0279 (2025).

Pinton, L. et al. 3d human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived bioengineered skeletal muscles for tissue, disease and therapy modeling. Nat. Protoc. 18, 1337–1376 (2023).

Madden, L., Juhas, M., Kraus, W. E., Truskey, G. A. & Bursac, N. Bioengineered human myobundles mimic clinical responses of skeletal muscle to drugs. ELife 9, e04885 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Three-dimensional tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle model of pompe disease. Commun. Biol. 4, 524 (2021).

McNamara, H. M. et al. Bioelectrical domain walls in homogeneous tissues. Nat. Phys. 6, 357–364 (2020).

Massart, R. Preparation of aqueous magnetic liquids in alkaline and acidic media. IEEE Trans. Magn. 17, 1247–1248 (1981).

de Walle, A. V. et al. Magnetic nanoparticles in regenerative medicine: what of their fate and impact in stem cells? Mater. Today Nano 11, 100084 (2020).

Perez, J. E., Nagle, I. & Wilhelm, C. Magnetic molding of tumor spheroids: emerging model for cancer screening. Biofabrication 13, 015018 (2020).

Mazuel, F. et al. Massive intracellular biodegradation of iron oxide nanoparticles evidenced magnetically at single-endosome and tissue levels. ACS Nano 10, 7627–7638 (2016).

Rezakhaniha, R. et al. Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in the arterial adventitia using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 11, 461–473 (2011).

Kersigo, J. et al. A rnascope whole mount approach that can be combined with immunofluorescence to quantify differential distribution of mrna. Cell Tiss. Res. 374, 251–262 (2018).

Herbert, S. et al. Localzprojector and deproj: a toolbox for local 2d projection and accurate morphometrics of large 3d microscopy images. BMC Biol. 19, 136 (2021).

Thielicke, W. & Sonntag, R. Particle image velocimetry for matlab: accuracy and enhanced algorithms in pivlab. J. Open Res. Softw. https://doi.org/10.5334/jors.334 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the ImagoSeine core facility of the Institute Jacques Monod (member of the France BioImaging, ANR-10-INBS-04) and especially Nicolas Valentin on the FACS platform. We thank the staff of the MPBT (physical properties—low temperature) platform of Sorbonne Université for their support. We acknowledge Veronique Thevenet (Laboratoire MSC, UMR 7057, Paris) and Aude Michel (PHENIX, UMR 8234, Paris) for providing us with the nanoparticles. We acknowledge Sylvie Coscoy for LifeAct-GFP plasmid. This work was supported by the Program Emergence(s) de la Ville de Paris (Grant MAGIC Project) and the Ile-de-France Region via the DIM BioConv’S. The study was supported by the Labex Who Am I?, Labex ANR-11-LABX-0071, the Université de Paris, Idex ANR-18-IDEX-0001 funded by the French Government through its Investments for the Future program and the French Defense Procurement Agency (DGA-AID) France. This project has received financial support from the CNRS through the Tremplin Action.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.N., L.S., P.G. and A.R. performed the magnetic stretcher experiments. I.N., L.S., P.G., T.S. and M.R. did the immunofluorescence imaging. I.N. and N.L. performed the RT-qPCR experiments and analysis. T.S. and M.R. performed image analysis. I.N. and M.R. performed orientation analysis. I.N., F.D., S.B.P. and N.L. performed Western blots. T.S., L.R., M.Rec, C.W. and M.R. designed the magnetic stretcher and incubation chambers. L.S. and P.G. performed the FISH experiments. I.N., N.L. and M.R. designed the experiments. M.R. supervised the study and wrote the original draft. I.N., L.S., F.D., T.S., S.B.P., C.W. and N.L. reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Marine Luciano and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagle, I., van der Spek, L., Gesenhues, P. et al. Shaping 3D minimal model tissues with mechanical constraints to orchestrate muscle differentiation. Commun Biol 8, 1853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09252-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09252-9