Abstract

Anopheles darlingi is the primary malaria vector in Central and South America and is responsible for most malaria transmission in the Amazon region. In this study, we perform whole-genome analysis of individual An. darlingi mosquitoes to explore genomic diversity, signatures of selection, and insecticide resistance markers. We analysed wild-caught (n = 20) and colony-maintained (n = 8) mosquitoes from the State of Rondônia, Brazil. In total, 1.54 million high-quality single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified. Population genomic analysis revealed genetic differentiation between the colony and wild populations. No SNPs previously associated with insecticide resistance were detected. However, several SNPs were observed in four genes commonly associated with insecticide resistance: ace1, rdl, gste2, and vgsc. Genes under directional selection were identified, but no clear selective sweeps were found using genome-wide selection scans. Gene duplications were identified in cytochrome P450 genes, which are known to metabolise pyrethroids. This study provides a detailed genetic profile of An. darlingi, highlighting genes potentially involved in insecticide resistance, and presents an analysis of signatures of selection based on WGS data for this species. Our findings identify markers in insecticide resistance-associated genes that warrant further investigation through phenotypic-genotypic assays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anopheles darlingi (or Nyssorhynchus darlingi1) is a major malaria vector throughout South and Central America2. This species is an efficient vector of both Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria due to its high susceptibility to Plasmodium infection, its ability to maintain transmission at low parasite densities2, and its propensity to feed on humans3,4. Furthermore, An. darlingi is highly adaptable and exhibits significant behavioural variation, including the ability to adapt to environments undergoing urbanisation and deforestation2,5. This species is particularly prominent in recently deforested areas, where its abundance surpasses that of other Anopheles species6. The ongoing anthropisation of these environments is thought to sustain malaria transmission by increasing the availability of larval habitats for Anopheles vectors7,8.

In 2023, an estimated 500,000 malaria cases were reported in the Americas, with Brazil accounting for the largest share (~163,000 cases), predominantly in the Amazon region9. Malaria cases in Brazil have increased from 138,000 in 2015, with P. vivax responsible for 72.1% of infections and P. falciparum for 16%10. Alarmingly, the proportion of P. falciparum cases has risen by 7%11, raising concerns due to its higher mortality rate, particularly among children and pregnant women. Strengthening malaria control in Brazil is crucial to curbing transmission and achieving both the country’s National Elimination Plan and the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) goal of a 90% reduction in malaria incidence by 203012.

Malaria control in Brazil primarily relies on indoor residual spraying (IRS) and insecticide-treated nets (ITNs)13,14. Pyrethroids are the most widely used insecticides against Anopheles mosquitoes, while carbamates and organophosphates are deployed for Aedes control in arbovirus programmes15,16. Systematic insecticide resistance surveillance is essential for informed vector control strategies, yet Brazil currently lacks a national screening programme for Anopheles mosquitoes. Resistance to pyrethroids, carbamates, and organochlorines has been documented in An. darlingi populations in Bolivia, Colombia, French Guiana, and Peru17,18. Insecticide resistance has not been reported in Brazil, which is likely due to limited historical surveillance17.

Insecticide resistance arises through multiple mechanisms, including target-site mutations, metabolic resistance, behavioural adaptations, cuticle thickening, and microbiome alterations19,20. Four key genes associated with insecticide resistance are the voltage-gated sodium channel gene (vgsc), the acetylcholinesterase gene (ace1), the glutathione S-transferase gene (gste2), and the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (rdl – resistant to dieldrin gene). The vgsc gene encodes a transmembrane protein essential for nerve function, and is targeted by pyrethoid and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) insecticides21. Whereas, organophosphate and carbamate insecticides work by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (encoded by ace1), which is required for stopping synaptic transmission by hydrolyzing the acetylcholine neurotransmitter22. The gste2 gene encodes a metabolic enzyme able to metabolise insecticides23, and the rdl gene encodes a GABA subunit which is involved in nervous system signalling24. Target-site resistance is often driven by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these genes. Well-characterised resistance-associated SNPs in the Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (s.l.) complex include V402L, L995F/S, I1527T, F1529C and N1570Y in the voltage-gated sodium channel (vgsc) linked to pyrethroid and DDT resistance, G280S in ace1 conferring organophosphate and carbamate resistance25,26,27, L119F in gste2 associated with DDT/pyrethroid resistance23, and A296G/S, V327I and T345S in the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (rdl), which have been associated with resistance to dieldrin28,29. These SNPs may be identified rapidly using multiplex amplicon sequencing30,31. However, no SNPs associated with target-site resistance in other Anopheles species have been identified in An. darlingi to date32,33,34,35,36. Metabolic resistance, which results from differential gene expression enhancing detoxification enzyme activity23,37,38,39, is hypothesised to play a dominant role in insecticide resistance in An. darlingi, particularly given the absence of known target-site mutations. Increased metabolic resistance can arise from increased copy number of metabolic enzymes, resulting in increased gene expression. Three key metabolic enzyme families include the cytochrome P450s, esterases, and glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs)40. Copy number variation (CNVs) in cytochrome P450 genes is highly complex41,42, and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes has been strongly associated with CNVs in cyp6aa143, cyp6aap44, cyp6m2, cyp6p3, cyp6z1 and cyp9k145,46, and with CNVs in the GST encoding gene gste247. Furthermore, significant overexpression of genes in these metabolic families has been associated with insecticide resistance48,49,50.

Previous molecular studies of An. darlingi have focused on screening a limited number of loci in four candidate resistance genes (vgsc, ace1, gste2, rdl). However, genome-wide approaches are needed to identify novel resistance markers30,36. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has been extensively applied to An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes to investigate population structure and resistance evolution51,52. Here, we apply WGS to two Brazilian An. darlingi populations in Rondônia State: a wild population from Candeias do Jamari, and a colony population from Porto Velho, both in the State of Rondônia and < 100 km apart from each other. By examining ancestry, population structure, and genetic regions under selection, we aimed to characterise genomic diversity and identify molecular markers potentially associated with insecticide resistance in this vector population, serving as a valuable resource for future research on vector adaptation and resistance mechanisms.

Results

Whole genome sequence data for An. darlingi

Twenty-eight An. darlingi mosquito samples were sequenced using WGS, yielding an average genome-wide coverage of 8.99-fold. The dataset comprised 20 wild-caught specimens from Candeias do Jamari (Rondônia) and 8 colony samples derived from mosquitoes originally maintained in Porto Velho (Rondônia) in 2018. After variant calling and quality filtering, 1,539,646 high-quality variants were retained for analysis, with 1,489,593 variants detected in the wild-caught samples and 535,667 in the colony samples. This discrepancy in variant number is likely due to the difference in sample size between these two populations.

An. darlingi colony samples are genetically distinct from wild populations

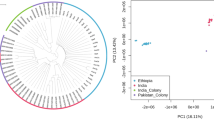

Admixture analysis identified two ancestral groups (K = 2), designated as K1 and K2, which differentiate the colony (n = 8) and wild (n = 20) Rondônia populations (Fig. 1). One colony sample (AnDar_1382) exhibited mixed ancestry from both K1 and K2, while three wild-caught samples primarily belonged to K2 but contained a small proportion of K1 ancestry.

Principal component analysis (PCA) reveals a clear genetic distinction between the colony and wild mosquitoes, consistent with the admixture analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). As expected, chromosome-specific PCA highlights the separation between colony and wild mosquitoes across chromosomes 2, 3, and X (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mitochondrial PCA, and a maximum likelihood tree based on the mitochondrial genome, did not show clear distinction between the colony and wild mosquitoes (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Population differentiation due to genetic structure was measured using the Fixation index (FST) statistic, where a value of 1 indicates complete differentiation between two populations, whereas a value of 0 indicates no differentiation53. FST analysis calculated in 1000 bp windows revealed allele frequency differences between the two populations. On chromosome 2, 349 SNPs had an FST ≥ 0.75, including 25 SNPs with an FST ≥ 0.9 and 3 SNPs with an FST of 1. On chromosome 3, 63 SNPs had an FST ≥ 0.75, with 8 of these reaching FST ≥ 0.9. Chromosome X had 3 SNPs with an FST ≥ 0.75, while no SNPs on the mitochondrial genome had FST ≥ 0.75 (FST on the mitochondrial genome ranged from 0.062 to 0.419). Genomic windows and genes with FST ≥ 0.9 across the genome are summarised in Table 1. Median genome-wide FST between the wild-caught and colony Rondônia An. darlingi populations was 0.143. This population differentiation is markedly high in comparison to other Anopheles species; low divergence is common in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii (FST < 0.05)54, and even FST computed between these two species has been identified as low (FST < 0.14)51. Similarly high An. darlingi FST values were identified in a larger study of 1,094 mosquitoes, where the median pairwise FST between populations in Brazil, Colombia, Guiana, Guyana, Peru, and Venezuela was 0.1855. These high An. darlingi FST values indicate increased genetic separation between populations, in comparison with African Anopheles species.

Mutations in genes associated with insecticide resistance

SNPs were identified in four key genes associated with insecticide resistance in other vector species (ace-1, gaba, GSTe2, and vgsc) (Supplementary Table 1). Seven nonsynonymous SNPs were detected in these four genes (Table 2). However, none of the resistance mutations that have previously been associated with insecticide resistance in Anopheles species were detected. An additional 129 potential genes of interest were investigated, including those where reported SNPs have been associated with reduced insecticide efficacy. These included vgsc, ace-1, all gaba genes, cytochrome P450s, carboxylesterases, glutathione transferases, and glucuronyltransferases. In total, 442 nonsynonymous SNPs were identified across these genes (Supplementary Data 1). The T283K mutation in the ADAR2_008159 gene (cyp6aa1 in An. funestus) has been identified as possibly linked to deltamethrin resistance in An. darlingi55. This mutation was not identified in the Rondônia samples. However, two other non-synonymous mutations were identified in this gene: I370V at 43.8% allelic frequency in the wild population and 31.3% in the colony population, and E359Q, which was found at 8.8% allelic frequency in the wild population and was absent in the colony population.

Nucleotide diversity

Nucleotide diversity (π) is the average number of nucleotide differences per site, between two populations56. π was calculated to estimate the level of genetic variation within the wild mosquito population, and was computed in 100 bp windows across the genome. The average nucleotide diversity among these 20 An. darlingi was π = 0.002, which is lower than has previously been found in An. gambiae s.l. populations from 15 locations across Africa (averaging at π = 0.015)51, and likely reflects this small sample size. Nucleotide diversity in key insecticide resistance genes was compared between the wild-caught An. darlingi (n = 20) and a reference dataset of wild-caught An. gambiae sensu stricto (s.s.) samples (n = 42) from Bubaque Island in the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa (Table 3)57. This reference dataset was selected for comparison as both are wild Anopheles populations caught in a small geographic area. Nucleotide diversity was low in both populations but consistently 3 to 6 times higher in the wild-caught An. gambiae s.s. from Bubaque Island than the wild-caught An. darlingi (Table 3), indicating relatively little variation within this small sample of wild-caught An. darlingi from Rondônia State.

Natural selection across the An. darlingi genome

Integrated haplotype (iHS) and Garud’s H12 statistics were used to identify loci under directional selection in the wild samples (n = 20). The iHS metric measures extended haplotype homozygosity to identify signatures of recent selection within a particular population58. A total of 103 loci showed evidence of directional selection, which may be due to selection pressure from insecticide use, or from other selection pressures (iHS score ≥ 4) (Fig. 2A). Of the 103 loci with significant iHS scores, 57 were in protein-coding genes (Table 4). None of these protein-coding genes have previously been associated with insecticide resistance in An. darlingi or other Anopheles species.

A iHS scores for wild-caught mosquito samples (n = 20) where iHS score ≥ 4 indicates positive selection. This significance threshold is depicted by the black dashed line. B XP-EHH comparison between colony mosquitoes (n = 8) and wild (n = 20) mosquitoes. Values ≤ -4 indicate significant selection in the wild-caught samples when compared to the colony mosquitoes, whereas values ≥ 4 indicate significant selection in the colony mosquitoes when compared to the wild samples.

Garud’s H12 statistic examines the frequency of the most common haplotype in a population (H1) versus the second most common haplotype (H2), to identify soft and hard selective sweeps59. H12 was also calculated as an additional method to identify selective sweeps across the genome60. No significant sweeps were identified (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) compares selection between two populations by contrasting haplotype lengths associated with the same allele in different populations61. XP-EHH analysis was performed to identify loci under significant positive directional selection in the wild mosquitoes when compared to colony mosquitoes (Fig. 2B). A value ≤ -4 indicates significant selection in the wild-caught samples when compared to the colony mosquitoes, whereas a value ≥ 4 indicates significant selection in the colony mosquitoes. Protein-coding genes identified to be under significant selection are listed in Table 5. Notably, loci under significant selection in wild mosquitoes, compared to colony mosquitoes, were located outside of protein-coding genes.

To further investigate signatures of selection, Tajima’s D (TD) statistic was calculated in 20,000 bp windows across the genome for each population. In the colony samples, median TD was 1.09, and 269 windows exhibited TD values > 2.5 (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting balancing selection or a recent population bottleneck; consistent with the characteristics of a colony-bred population. Whereas the wild-caught samples had a median TD of -0.877, suggesting possible population expansion. This is lower than the TD found in a larger study of 1094 An. darlingi from across South America (median TD = 0.26 per population), suggesting stability in An. darlingi population size55. Whereas, our lower TD value supports a possible population expansion in the wild-caught mosquitoes from Rondônia, which may be influenced by our small sample of 20 wild-caught mosquitoes. Both of these studies identified TD values contrasting with the more negative TD associated with An. gambiae populations, which are reported as TD < -1.5 and reflect rapid population expansion within this African species complex51.

Structural variants

Structural variants (SVs) were identified in regions containing putative genes of interest, including 148 inversions, 54 deletions, 27 duplications, 18 insertions, and 32 inter-chromosomal translocations (Supplementary Data 2). Among these SVs, we identified gene duplications which frequently involved members of the cytochrome P450 gene family (Table 6); a gene family previously associated with insecticide resistance41,48. These included cytochrome P450 4cs3-like, 4d1-like, 4C1-like and 3A19-like genes, and cytochrome P450 6a13, 313a4, and 313a1 genes. Additionally, we identified duplications that introduced premature stop codons, splice region variants, and duplicated exons. One limitation of this analysis is the relatively low average read depth (8.99-fold), which may have resulted in missed SVs that could be detected in future studies using higher coverage sequencing.

Discussion

This study presents WGS data and analysis for two An. darlingi populations from Rondônia, Brazil: a wild-caught population from Candeias do Jamari and a colony population originated from mosquitoes collected in Porto Velho. Clear genetic separation between these two populations was identified in the principal component and admixture analyses, with distinct ancestries and differentiation across chromosomes 2, 3, and X. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis and principal component analyses of mitochondrial DNA did not show clear separation between the colony and wild-caught populations, which is not surprising given the close proximity of the Candeias do Jamari and Porto Velho collection sites (<100 km apart). Nucleotide diversity was low in both populations, reflecting the small sample size, and Tajima’s D analysis suggested a bottleneck in the colony mosquitoes and possible population expansion in the wild-caught mosquitoes. These findings align with expectations for the colony, given extensive inbreeding, and for the wild-caught population, which was sampled from a small geographic area (radius <5 km).

Fixation index (FST) analysis further supported genetic differentiation between the two populations, with chromosome 2 showing the highest divergence, followed by chromosome 3 and chromosome X. Whereas, FST analysis of the mitochondrial genome showed reduced divergence. Notably, the gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor subunit 2 (ADAR2_002857) on chromosome 2 exhibited high differentiation between the colony and wild-caught samples. Organochlorine insecticides act by binding to the GABA receptor complex, with the most common resistance mutation being A259S/G in the rdl gene29,62. Overall, FST was high in An. darlingi when compared with other Anopheles species, including An. gambiae and An. coluzzii in Africa51. This high FST is corroborated by a much larger study of 1094 An. darlingi from across South America, which also found elevated FST scores in An. darlingi population comparisons55.

Previous studies using mitochondrial cox-1 sequences have suggested that geographic barriers, such as the Andes and Amazon River, influence An. darlingi population structure63,64,65,66. The colony samples in this study originated from mosquitoes collected in Porto Velho in 2018, while the wild-caught samples were obtained less than 100 km away in 2018 and 201967. Our study demonstrates the advantage of genome-wide approaches in resolving population dynamics as, despite their geographic proximity, WGS analysis was able to effectively distinguish the ancestries of these populations.

No well-characterised mutations associated with insecticide resistance in other Anopheles species were detected in An. darlingi. However, we identified seven novel nonsynonymous SNPs within four key resistance-associated genes (ace-1, rdl, GSTe2, vgsc), including the Pro523Leu mutation in vgsc. Further research is needed to determine their functional significance, including the integration of phenotypic resistance data. Similar investigations in An. funestus have identified molecular markers of resistance, suggesting a comparable approach could be applied to An. darlingi38,68,69.

Metabolic detoxification is hypothesised to play a greater role in An. darlingi insecticide resistance than target-site mutations70. In An. gambiae, pyrethroid resistance has been linked to copy number variations (CNVs) in detoxification enzyme families (cytochrome P450s, esterases, and glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs)). Using WGS, we were able to examine the genetic diversity of these gene families in An. darlingi. We found no selective sweeps over insecticide resistance-related genes through analysis of extended haplotype homozygosity using H1260. However, structural variant analysis revealed high-impact gene duplications involving multiple cytochrome P450 genes:cyp4c3, cyp4d2, cyp4c1, cyp9f2s, cyp6a13, cyp313a4, cyp3a19, cyp313a1-like. Three of these genes (cyp4c1, cyp4c3, cyp4d2) have been implicated in insecticide resistance in other species71,72; cyp4c1 is upregulated in Aedes aegypti resistant to DDT, pyrethroids, and carbamates, and in Cydia pomonella larvae resistant to deltamethrin73,74. Additionally, cyp4c1 has been linked to metabolic compensation during starvation in cockroaches and is hormonally regulated75,76. It has also been found to be upregulated in the crop pest Leptinotarsa decemlineata following exposure to neonicotinoids77. In contrast, the function of cyp4c3 remains less well understood, though it has been found upregulated in honeybees after amitraz insecticide treatment78.

In addition, we identified a duplication in the glutathione S-transferase gene (ADAR2_012021), a gene family known to confer resistance to organophosphates and DDT79. Class 1 GSTs, which mediate resistance in Musca domestica, are believed to perform a similar function in Anopheles species, though further evidence is needed to confirm this80,81,82. More generally, to determine the functional role of these duplications in insecticide resistance, further studies incorporating phenotypic resistance data are required. Comparative RNA-seq analysis of insecticide-resistant and susceptible An. darlingi populations could help to identify resistance-associated gene expression changes. Limitations of this study include the lack of phenotypic resistance data and the small overall sample size, which is limited to a small geographic region. Future studies should incorporate larger sample sizes of An. darlingi from diverse regions, along with phenotypic resistance data for the most frequently used insecticides in Brazil. Other phenotypes can also be investigated, such as biting behaviour, which has been explored for this species using low-coverage genomic sequencing data of pooled samples83.

Overall, our study presents an initial analysis of WGS data from An. darlingi malaria vectors, establishing a foundation for future studies with more expansive sample sizes and associated phenotypic data. Large-scale surveillance of An. darlingi is essential to gain deeper insights into its molecular ecology and to identify genomic markers linked to key traits, including insecticide resistance, vector competence, blood-feeding behaviour, and adaptation to environmental changes. This comprehensive approach will provide valuable insights into the genetic factors influencing An. darlingi populations and enhance the development of targeted control strategies.

Methods

Mosquito collection, species identification, and DNA extraction

Two populations of An. darlingi from the State of Rondônia were used in this study, one wild-caught population from Candeias do Jamari, right margin of Madeira River, (n = 20), and a cohort of colony isolates from Porto Velho (n = 8)67. The wild-caught mosquitoes were collected during vector density studies in malaria-endemic regions in Rondônia in 2018–19. Entomological surveys were performed as 8 consecutive collections at the beginning of the rainy season (Oct and Nov 2018), and another eight collections were performed at the beginning of the dry season (May and June 2019)84. The colony of mosquitoes has been maintained since 2018, originally collected in Porto Velho, left margin of Madeira River45. Specimens were morphologically identified via microscopy. Genomic DNA from the isolates was extracted from the whole mosquito using Qiagen DNaeasy Blood and Tissue kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 fluorimeter HS DNA kit (Thermofisher), and stored at −20 °C.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Twenty-eight An. darlingi isolates were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq on 2 x 250 bp paired-end configuration in 2024, with an average read-depth of 8.99-fold. The raw paired fastq files were trimmed using trimmomatic software (version 0.39), and then aligned using bwa-mem software to the AnoDar_H01 (An. darlingi) reference genome using default parameters85,86. Genome coverage from the mapped bam files was calculated using samtools, and variants called and validated using HaplotypeCaller and VailidateVariants from GATK software, respectively (v4.1.4.1)87,88. Once VCFs had been generated for each sample, GATK was used to create a multi-sample VCF with GenomicsDBImport and GenotypeGVCF functions. The multi-sample VCF was filtered to include chromosomal variants using bcftools (v 1.17) and GATK’s VariantFiltration, with parameters: QD > 5.0, QUAL > 30.0, SOR < 3.0, FS < 60.0, MQ > 40.0, MQRankSum > − 12.5, ReadPosRankSum > -8.0. Reads were subsequently filtered to retain those with DP > 5.0 and GQ > 20.0, and variants were filtered to retain those with < 20.0% missing genotypes or MAF > 0.01. The resulting VCF was phased with Beagle (version 5.2)89 and annotated using SnpEff (v5.1 d)90.

Population genetic analysis

From the filtered multi-sample VCF, a pairwise-genetic distance matrix was generated using PLINK (v1.90b6.21 64-bit)91,92. This matrix was used for the generation of a maximum-likelihood tree using RAxML-NG (v 1.2.0), and principal component analysis was calculated using the R package ape (5.7-1)93. The ML tree generated was annotated and visualised in iTOL94. Ancestry admixture analysis was conducted using ADMIXTURE software (version 1.3)95. The optimum K value (estimated number of ancestral populations) was calculated through cross-validation of 1-10 eigenvalue decay dimensions92. In this instance, K = 2 was estimated, and ADMIXTURE software was used to analyse the shared ancestral populations (denoted K1 and K2) in these samples. The output was then visualised in R using ggplot2 package (v 3.4.2)96.

Genomic regions under selection were identified with the python package scikit-allel (v 1.3.6)97. Three complementary statistics were used: H1260, iHS, and XP-EHH61,98. The Integrated Haplotype Statistic (iHS) was used to find directional selection within populations, and extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) between the two populations99,100. Garud’s H12 was calculated using phased biallelic SNPs in 1000 bp windows, using the moving_garud_h function97. Two hundred iterations of H12 were calculated, followed by plotting of the mean value for each genomic window. iHS was computed using phased biallelic SNPs using the allel.ihs function97. Raw iHS scores were then standardized using the function allel.standardize_by_allele_count, and p-values were plotted. XP-EHH was calculated using phased biallelic SNPs using the allel.xpehh function. The Tajima’s D (TD) statistic was calculated using vcftools (v0.1.16) in 20 kbp windows across chromosomes to identify balancing selection101,102. Nucleotide diversity (π) was calculated in 100 bp windows across chromosomes using vcftools and plotted in R. Weir and Cockerham’s F statistic (FST) was calculated in 1-kbp windows over each chromosome using the windowed_weir_cockerham_fst function in scikit-allel97.

Examination of insecticide resistance associated genes

A bed file of genes commonly associated with target-site insecticide resistance SNPs was created. All annotated cytochrome P450s and esterases linked to metabolically mediated insecticide resistance were included. The bed file was then applied to the multi-sample VCF using bcftools (v1.17) view function. The snpEff software was then used to annotate the effect each SNP would have on the protein’s amino acid sequence90. A custom-built database was created for this, following the snpEff instructions at https://pcingola.github.io/SnpEff/snpeff/build_db_gff_gtf/ and using the instructions AnoDar_H01 GFF file which is available for download from NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_943734745.1/). DELLY (v1.1.8) was used to investigate CNVs across the whole genome103. These were then filtered for quality and for those impacting genes within the expanded list of candidate genes used above.

Ethics & inclusion

This project was determined and conducted in collaboration with local researchers and is locally relevant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All raw data used in this work is publicly available from the NCBI BioProject database under accession number PRJEB66076. Sample IDs for the mosquito samples used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Code availability

All code used to analyse data is publicly available at https://github.com/sophiemoss/Anopheles_darlingi_genome_wide_analysis_Rondonia_Brazil.

References

Foster, P. G. et al. Phylogeny of Anophelinae using mitochondrial protein coding genes. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 170758 (2017).

Hiwat, H. & Bretas, G. Ecology of Anopheles darlingi Root with respect to vector importance: a review. Parasit. Vectors 4, 177 (2011).

Klein, T. A., Lima, J. B. P. & Tada, M. S. Comparative Susceptibility of Anopheline Mosquitoes to Plasmodium Falciparum in Rondonia, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 44, 598–603 (1991).

Gil, L. H. S., Tada, M. S., Katsuragawa, T. H., Ribolla, P. E. M. & da Silva, L. H. P. Urban and suburban malaria in Rondônia (Brazilian Western Amazon) II: perennial transmissions with high anopheline densities are associated with human environmental changes. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 102, 271–276 (2007).

Charlwood, J. D. Biological variation in Anopheles darlingi root. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 91, 391–398 (1996).

Da Silva-Nunes, M. et al. Malaria on the amazonian frontier: Transmission dynamics, risk factors, spatial distribution, and prospects for control. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79, 624–635 (2008).

Angêlla, A. F. et al. Seasonal genetic partitioning in the neotropical malaria vector, Anopheles darlingi. Malar. J. 13, 1–10 (2014).

Moutinho, P. R., Gil, L. H. S., Cruz, R. B. & Ribolla, P. E. M. Population dynamics, structure and behavior of Anopheles darlingi in a rural settlement in the Amazon rainforest of Acre, Brazil. Malar. J. 10, 1–13 (2011).

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report (2024).

Global Malaria Programme: WHO Global. WHO World Malaria Report 2022. WHO.

Laporta, G. Z., Grillet, M. E., Rodovalho, S. R., Massad, E. & Sallum, M. A. M. Reaching the malaria elimination goal in Brazil: a spatial analysis and time-series study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 11, 39 (2022).

Torres, K. et al. Malaria Resilience in South America: Epidemiology, Vector Biology, and Immunology Insights from the Amazonian International Center of Excellence in Malaria Research Network in Peru and Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 107, 168–181 (2022).

Rocha, E. M. et al. Vector-Focused Approaches to Curb Malaria Transmission in the Brazilian Amazon: An Overview of Current and Future Challenges and Strategies. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 5, 161 (2020).

Baia-da-Silva, D. C. et al. Current vector control challenges in the fight against malaria in Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 52, e20180542 (2019).

Campos, K. B. et al. Assessment of the susceptibility status of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) populations to pyriproxyfen and malathion in a nation-wide monitoring of insecticide resistance performed in Brazil from 2017 to 2018. Parasit. Vectors 13, 531 (2020).

de Leandro, A. S. et al. Malathion insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti: laboratory conditions and in situ experimental approach through adult entomological surveillance. Trop. Med. Int. Health 25, 1271–1282 (2020).

WHO. Global Malaria Programme: Malaria Threats Map. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/surveillance/malaria-threats-map.

World Health Organisation. Global Report on Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Vectors: 2010-2016 Global Malaria Programme.

Namias, A., Jobe, N. B., Paaijmans, K. P. & Huijben, S. The need for practical insecticide-resistance guidelines to effectively inform mosquito-borne disease control programs. eLife 10, e65655.

Organização Mundial da Saúde. Guidelines for Malaria Vector Control. Guidelines for Malaria Vector Control (2019).

Nardini, L. et al. The voltage-gated sodium channel, para, limits Anopheles coluzzii vector competence in a microbiota dependent manner. Sci. Rep. 13, 14572 (2023).

Weill, M. et al. Insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors. Nature 423, 136–137 (2003).

Riveron, J. M. et al. A single mutation in the GSTe2 gene allows tracking of metabolically based insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector. Genome Biol. 15, R27 (2014).

Taylor-Wells, J., Brooke, B. D., Bermudez, I. & Jones, A. K. The neonicotinoid imidacloprid, and the pyrethroid deltamethrin, are antagonists of the insect Rdl GABA receptor. J. Neurochem. 135, 705–713 (2015).

Martinez-Torres, D. et al. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol. Biol. 7, 179–184 (1998).

Ranson, H. et al. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol. Biol. 9, 491–497 (2000).

Weill, M. et al. The unique mutation in ace-1 giving high insecticide resistance is easily detectable in mosquito vectors. Insect Mol. Biol. 13, 1–7 (2004).

Yang, C., Huang, Z., Li, M., Feng, X. & Qiu, X. RDL mutations predict multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles sinensis in Guangxi, China. Malar. J. 16, 482 (2017).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Identification and distribution of a GABA receptor mutation conferring dieldrin resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 484–491 (2011).

Acford-Palmer, H. et al. Application of a targeted amplicon sequencing panel to screen for insecticide resistance mutations in Anopheles darlingi populations from Brazil. Sci. Rep. 15, 731 (2025).

Moss, S. et al. Genomic surveillance of Anopheles mosquitoes on the Bijagós Archipelago using custom targeted amplicon sequencing identifies mutations associated with insecticide resistance. Parasit. Vectors 17, 10 (2024).

Lol, J. C. et al. Development of molecular assays to detect target-site mechanisms associated with insecticide resistance in malaria vectors from Latin America. Malar. J. 18, 202 (2019).

Orjuela, L. I. et al. Absence of knockdown mutations in pyrethroid and DDT resistant populations of the main malaria vectors in Colombia. Malar. J. 18, 1–9 (2019).

Application of a targeted amplicon sequencing panel to screen for insecticide resistance mutations in Anopheles darlingi populations from Brazil. https://www.researchsquare.com, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3053716/v1 (2023).

Loureiro, A. C. et al. Molecular diversity of genes related to biological rhythms (period and timeless) and insecticide resistance NaV and ace-1in Anopheles darlingi. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 118, e220159 (2023).

Bickersmith, S. A. et al. Mutations Linked to Insecticide Resistance Not Detected in the Ace-1 or VGSC Genes in Nyssorhynchus darlingi from Multiple Localities in Amazonian Brazil and Peru. Genes 14, 1892 (2023).

Cariño, F. A., Koener, J. F., Plapp, F. W. & Feyereisen, R. Constitutive overexpression of the cytochrome P450 gene CYP6A1 in a house fly strain with metabolic resistance to insecticides. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 24, 411–418 (1994).

Ibrahim, S. S., Ndula, M., Riveron, J. M., Irving, H. & Wondji, C. S. The P450 CYP6Z1 confers carbamate/pyrethroid cross-resistance in a major African malaria vector beside a novel carbamate-insensitive N485I acetylcholinesterase-1 mutation. Mol. Ecol. 25, 3436–3452 (2016).

Vontas, J., Katsavou, E. & Mavridis, K. Cytochrome P450-based metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles and Aedes mosquito vectors: Muddying the waters. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 170, 104666 (2020).

Hemingway, J. & Ranson, H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45, 371–391 (2000).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals high complexity of copy number variation at insecticide resistance loci in malaria mosquitoes. Genome Res. 29, 1250–1261 (2019).

Weetman, D., Djogbenou, L. S. & Lucas, E. Copy number variation (CNV) and insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: evolving knowledge or an evolving problem?. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 27, 82–88 (2018).

Ibrahim, S. S. et al. Pyrethroid Resistance in the Major Malaria Vector Anopheles funestus is Exacerbated by Overexpression and Overactivity of the P450 CYP6AA1 Across Africa. Genes 9, 140 (2018).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Copy number variants underlie major selective sweeps in insecticide resistance genes in Anopheles arabiensis. PLOS Biol. 22, e3002898 (2024).

Vontas, J. et al. Rapid selection of a pyrethroid metabolic enzyme CYP9K1 by operational malaria control activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 4619–4624 (2018).

Hearn, J. et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies a CYP9K1 haplotype conferring pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa. Mol. Ecol. 31, 3642–3657 (2022).

Mitchell, S. N. et al. Metabolic and Target-Site Mechanisms Combine to Confer Strong DDT Resistance in Anopheles gambiae. PLOS ONE 9, e92662 (2014).

Njoroge, H. et al. Identification of a rapidly-spreading triple mutant for high-level metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae provides a real-time molecular diagnostic for antimalarial intervention deployment. Mol. Ecol. 31, 4307–4318 (2022).

Ingham, V. & Nagi, S. Genomic profiling of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: insights into molecular mechanisms. Res. Sq. rs.3.rs-3910702 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3910702/v1. (2024).

Meiwald, A. et al. Association of Reduced Long-Lasting Insecticidal Net Efficacy and Pyrethroid Insecticide Resistance With Overexpression of CYP6P4, CYP6P3, and CYP6Z1 in Populations of Anopheles coluzzii From Southeast Côte d’Ivoire. J. Infect. Dis. 225, 1424–1434 (2022).

Consortium, A. gambiae 1000 G et al. Genetic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nature 552, 96–100 (2017).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Genome-wide association studies reveal novel loci associated with pyrethroid and organophosphate resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Nat. Commun. 14, 4946 (2023).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 38, 1358 (1984).

Anopheles gambiae 1000 Genomes Consortium Genome variation and population structure among 1142 mosquitoes of the African malaria vector species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Genome Res. 30, 1533–1546 (2020).

Tennessen, J. A. et al. Population genomics of Anopheles darlingi, the principal South American malaria vector mosquito. 2025.03.13.643102 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.03.13.643102 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. High levels of nucleotide diversity and fast decline of linkage disequilibrium in rye (Secale cereale L.) genes involved in frost response. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 6 (2011).

Moss, S. et al. Phenotypic evidence of deltamethrin resistance and identification of selective sweeps in Anopheles mosquitoes on the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau. Sci. Rep. 14, 22840 (2024).

Glenn-Peter Saetre and Mark Ravinet. Evolutionary Genetic - Concepts, Analysis and Practice. (OUP Oxford, 2019).

Garud, N. R. & Rosenberg, N. A. Enhancing the mathematical properties of new haplotype homozygosity statistics for the detection of selective sweeps. Theor. Popul. Biol. 102, 94–101 (2015).

Garud, N. R., Messer, P. W., Buzbas, E. O. & Petrov, D. A. Recent selective Sweeps in North American Drosophila melanogaster Show Signatures of Soft Sweeps. PLOS Genet 11, e1005004 (2015).

Tang, K., Thornton, K. R. & Stoneking, M. A new approach for using genome scans to detect recent positive selection in the human genome. PLOS Biol. 5, e171 (2007).

Spadar, A., Collins, E., Messenger, L. A., Clark, T. G. & Campino, S. Uncovering the genetic diversity in Aedes aegypti insecticide resistance genes through global comparative genomics. Sci. Rep. 14, 13447 (2024).

Angêlla, A. F., Gil, L. H. S., Da Silva, L. H. P. & Ribolla, P. E. M. Population structure of the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi in Rondônia, Brazilian Amazon, based on mitochondrial DNA. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 102, 953–958 (2007).

Mirabello, L. & Conn, J. E. Molecular population genetics of the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi in Central and South America. Heredity 96, 311–321 (2006).

Emerson, K. J., Conn, J. E., Bergo, E. S., Randel, M. A. & Sallum, M. A. M. Brazilian Anopheles darlingi Root (Diptera: Culicidae) Clusters by Major Biogeographical Region. PLOS ONE 10, e0130773 (2015).

Pedro, P. M. & Sallum, M. A. M. Spatial expansion and population structure of the neotropical malaria vector, Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 97, 854–866 (2009).

Araujo, M. et al. Brazil’s first free-mating laboratory colony of Nyssorhynchus darlingi. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 52, e20190159 (2019).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Cis-regulatory CYP6P9b P450 variants associated with loss of insecticide-treated bed net efficacy against Anopheles funestus. Nat. Commun. 10, 4652 (2019).

Weedall, G. D. et al. A cytochrome P450 allele confers pyrethroid resistance on a major African malaria vector, reducing insecticide-treated bednet efficacy. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaat7386 (2019).

Fonseca-González, I., Quiñones, M. L., McAllister, J. & Brogdon, W. G. Mixed-function oxidases and esterases associated with cross-r esistance between DDT and lambda-cyhalothrin in Anopheles darlingi Root 1926 populations from Colombia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 104, 18–26 (2009).

Dulbecco, A. B., Calderón-Fernández, G. M. & Pedrini, N. Cytochrome P450 Genes of the CYP4 Clan and Pyrethroid Resistance in Chagas Disease Vectors. Front. Trop. Dis. 3, 1 (2022).

Killiny, N., Hajeri, S., Tiwari, S., Gowda, S. & Stelinski, L. L. Double-Stranded RNA Uptake through Topical Application, Mediates Silencing of Five CYP4 Genes and Suppresses Insecticide Resistance in Diaphorina citri. PLOS ONE 9, e110536 (2014).

Lien, N. T. K. et al. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis of Changes Associated with Insecticide Resistance in the Dengue Mosquito (Aedes aegypti) in Vietnam. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100, 1240–1248 (2019).

Insects | Free Full-Text | Genome-Wide Selective Signature Analysis Revealed Insecticide Resistance Mechanisms in Cydia pomonella. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/13/1/2.

Lu, K.-H., Bradfield, J. Y. & Keeley, L. L. Juvenile hormone inhibition of gene expression for cytochrome P4504C1 in adult females of the cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 667–673 (1999).

Cytochrome P450 family 4 in a cockroach: molecular cloning and regulation by regulation by hypertrehalosemic hormone. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.10.4558.

Bouafoura, R. et al. Characterization of Insecticide Response-Associated Transcripts in the Colorado Potato Beetle: Relevance of Selected Cytochrome P450s and Clothianidin. Insects 13, 505 (2022).

Ye, L. et al. Transcriptomic analysis to elucidate the response of honeybees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) to amitraz treatment. PLOS ONE 15, e0228933 (2020).

Enayati, A. A., Ranson, H. & Hemingway, J. Insect glutathione transferases and insecticide resistance. Insect Mol. Biol. 14, 3–8 (2005).

Ranson, H. et al. Cloning and Localization of a Glutathione S-transferase Class I Gene from Anopheles gambiae*. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5464–5468 (1997).

Fournier, D., Bride, J. M., Poirie, M., Bergé, J. B. & Plapp, F. W. Insect glutathione S-transferases. Biochemical characteristics of the major forms from houseflies susceptible and resistant to insecticides. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1840–1845 (1992).

Pasteur, N. & Raymond, M. Insecticide resistance genes in mosquitoes: their mutations, migration, and selection in field populations. J. Hered. 87, 444–449 (1996).

Alvarez, M. V. N. et al. Nyssorhynchus darlingi genome-wide studies related to microgeographic dispersion and blood-seeking behavior. Parasit. Vectors 15, 106 (2022).

Andrade, A. O. et al. Description of malaria vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) in two agricultural settlements in the Western Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 63, e60 (2021).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arxiv.org n/a, n/a (2013).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10, 1–4 (2021).

Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1207.3907. (2012)

Browning, B. L., Tian, X., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1880–1890 (2021).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 6, 80–92 (2012).

fastq2matrix/scripts at master · LSHTMPathogenSeqLab/fastq2matrix. GitHub https://github.com/LSHTMPathogenSeqLab/fastq2matrix/tree/master/scripts.

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296 (2021).

Alexander, D. H. & Lange, K. Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 246 (2011).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. ggplot2 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98141-3. (2009)

Miles, A. et al. cggh/scikit-allel: v1.3.13. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13772087 (2024).

Gautier, M., Klassmann, A. & Vitalis, R. rehh 2.0: a reimplementation of the R package rehh to detect positive selection from haplotype structure. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 78–90 (2017).

Sabeti, P. C. et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449, 913–918 (2007).

Voight, B. F., Kudaravalli, S., Wen, X. & Pritchard, J. K. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 4, e72 (2006).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA Polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989).

Rausch, T. et al. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28, i333–i339 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the PIVEM/Fiocruz Rondônia for An. darlingi culture. JFM also gratefully acknowledges their CNPq productivity grant (process number: 304830/2022-4). This work was supported in part by the Brazilian Ministry of Health/DECIT/CNPq N° 23/2019 (Grant number 442653/2019-0) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-003970). Under the grant conditions of the foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the author's accepted manuscript version that might arise from this submission. The study also received funding from the International Centres of Excellence for Malaria Research (ICEMR) programme GR109237 (CON-80002357). H.A.P. was funded by a BBSRC LIDo-DTP PhD studentship. T.G.C. and S.C. are funded by the UKRI (BBSRC BB/X018156/1; MRC MR/X005895/1; EPSRC EP/Y018842/1). S.M. is funded by UKRI (BBSRC BB/X018156/1). The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., M.A., A.O.A. and J.M. provided resources. H.A.-P. and S.M. performed bioinformatic and statistical analyses with guidance from E.M., J.P. and M.H. H.A.-P. and S.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and S.M. compiled the final version. All authors edited and approved the final version. T.G.C., S.C. and M.A. conceived and directed the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to the publication of this manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jason Charamis, Peter Arensburger, Jun Li, and John Essandoh for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michele Repetto.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moss, S., Acford-Palmer, H., Andrade, A.O. et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic diversity in Anopheles darlingi from Rondônia State, Brazil. Commun Biol 9, 52 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09316-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09316-w