Abstract

Spiders, a keystone predatory group for terrestrial ecosystem balance, have underexplored gut microbiotas. We collected 1090 spiders from 34 families in southwestern China, performing 16S rRNA sequencing to investigate their gut microbiota. Wandering and ambushing spiders exhibited higher α-diversity, while web-building spiders showed the lowest α-diversity with the highest endosymbiont infection rates. Gut microbiota diversity was significantly higher in Guizhou-region spiders than in Sichuan-region spiders. All spiders showed high amount of endosymbiont ASVs, which varied with foraging strategies and regions. Additionally, closer geographic distances between spiders were associated with more similar gut microbiota diversity levels. Environmental factor analysis preliminary revealed a positive correlation between precipitation and gut microbiota diversity, though its generalizability is limited by geographic sampling. Random processes were the primary drivers of spiders’ gut microbial community assembly. Our findings highlight that spider gut microbiota assembly is predominantly driven by stochastic processes but regulated by foraging strategies and geographic factors, providing a framework for understanding predator-microbe interactions in spiders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spiders are one of the most evolutionarily successful predators within terrestrial arthropods, exhibiting remarkable species diversity and adaptability to various ecological niches, and playing an irreplaceable role in maintaining the stability of the food web and the nutrient cycle1,2,3. Spiders have a unique extraintestinal digestion mode (where the venom anesthetizes the prey and then injects digestive fluid to liquefy the tissues before ingesting it), diverse lifestyles, and wide distribution etc., making it a special model for studying the gut microbiome4. In recent years, gut microbiotas have been widely studied and proven to play an extremely important role in the health, metabolism, disease, and other aspects of the host5,6,7,8,9,10. However, most of the studies about gut microbiomes were focused on humans, mammals, and livestock. Whether gut microorganisms can enhance spider fitness or contribute to their adaptive evolution remains poorly understood. Moreover, there are relatively few studies on the gut microbiota of spiders, and they are often limited to a few spider species11,12,13, leaving a significant gap compared to more extensively studied animal groups.

The composition and function of the gut microbiome in spiders may be closely related to multiple self-characteristics and environmental factors4,14,15. Previous studies have investigated the relationship between the gut microbiome of spiders and host system development, habitat, and source of food in some spider species4,14,15, and the phylosymbiosis between Hawaiian spiders and their microbiota16. However, the relationship between foraging strategies and spiders’ gut microbiota has not been well elaborated yet. Unlike other animals (like mammals, fish), which cannot be categorized as carnivorous, vegetarian, or omnivorous, spiders are almost entirely carnivorous (so far, only one kind of vegetarian spider, Bagheera kiplingi17, has been reported from Mexico and Costa Rica). Instead, their foraging strategy represents a distinctive characteristic and remarkable lifestyle, which can be divided into three main types of life: wandering, web-building, and ambushing18. Web-building (overground) and ambushing (waiting in the subterranean burrows or surface fissures) spiders rely on stationary traps to capture prey, while wandering spiders actively hunt, resulting in broader prey ranges, greater mobility, and higher metabolic rates19,20,21. The discrepancy of their foraging strategies (actively pursuit, net capture, ambush) leads to significant distinctions in food sources, activity ranges, and the degree of microhabitat exposure, providing an ideal model for the study of the evolution of life-specific microbiomes. We hypothesize that the foraging strategies of spiders can significantly influence the composition of their gut microbiota. Specifically, due to the broader prey range and higher mobility of wandering spiders and the microbial exposure in the soil of ambushing spiders (living in subterranean burrows or surface fissures), they could harbor more diverse gut microbiota and may enrich distinct microbial taxa compared with web-building spiders22,23,24,25.

Despite the gut microbiota emerging as a prominent research focus in recent years, previous studies in spiders have predominantly only focused on specific or a limited number of microbial groups, with endosymbiotic bacteria being the primary subject of investigation26,27,28. Endosymbionts, which primarily inhabit host cells, were ubiquitously found in arthropods and could induce diseases or establish mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships in their hosts29. In spiders, they play a crucial role in reproductive regulation via cytoplasmic incompatibility30. The carrying rate of endosymbiotic bacteria in spiders seems to be higher than that of other arthropod groups27. Previous studies have speculated that it might be related to the vertical transmission between spiders, cannibalism, and the enrichment of a wide range of food sources, but there is no solid conclusion at present27. Thus, we are also planning to explore whether the foraging strategy of spiders will affect the infection rate of their endosymbionts.

To address these hypotheses, we conducted extensive field sampling of spiders in southwestern China. Our study aims to: (1) reveal the effects of different foraging strategies on the composition of the spider gut microbiota; (2) explore the infection status of endosymbionts in spiders and determine whether their foraging strategies influence the endosymbiont infection rate; (3) investigate the influence of other factors, such as geographical and environmental factors, on the spider gut microbiota; and (4) uncover the microbial community assembly processes in spider gut. This study aims to fill the gap in research on the impact of spiders’ foraging strategy on their gut microbial community and the related influencing environmental factors. By synthesizing these findings, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of spider gut microbiota and its ecological determinants.

Results

Samples and sequencing quality

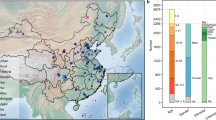

A total of 1090 samples collectively represented 35 families, 155 genera, and 288 species of spiders, which were collected at 11 sites in southwest China (Fig. 1A). According to the division of foraging strategies, we obtained 562 web-building spiders, 419 wandering spiders, and 99 ambushing spiders (Supplementary Data 1). Then, we performed 16S rRNA sequencing to obtain the gut microbiota information for those spiders. From these samples, we obtained 85,708,846 raw 16S rRNA sequences. After quality filtering with DADA2, 45,306,529 high-quality sequences were retained, which were classified into 100,822 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), with an average of 41,528 ASVs per sample. The rarefaction curve analysis of sample quality showed that as sequencing depth increased, the curve flattened, suggesting that further sequencing depth would only marginally increase the number of detected microbial species (Supplementary Fig. 1). This indicated that the sequencing results comprehensively reflected the information on the gut microbiota present in the samples. Moreover, when the number of sequences reached 20,000, the rarefaction curve was nearly completely flat, retaining 95.69% (1090 samples) of the samples. Therefore, we set the threshold at 20,000 for rarefaction, which will be used for subsequent β-diversity-related analyses.

A The sampling sites of spiders in this study. B The PCoA results among the three foraging strategies of spider gut microbiota. The α diversity of (C). Shannon index and (D). Simpson index of spiders’ gut microbiota for three foraging strategies of spiders (ambushing: n = 99; wandering: 429; web-building: 562). The relative abundance of gut microbiota at (E). The phylum level, (F). The genus level, and (G). The species level in three foraging strategies of spiders. The top 30 differentially abundant gut microbial (H). phyla, I genera, and J species among different foraging strategies of spiders identified by LEfSe, with the highest LDA values. The number of microbial (K) genera and (L) species identified in at least 10% of spider individuals of each foraging strategy group (the circle) and the number of specific microbiotas in each foraging strategy group (the common area).

Besides, we reorganized the information on the number of spider individuals recorded during the sampling process for each sample (Supplementary Data 1), and then conducted a linear regression analysis with the alpha diversity. The results were not significant (R-squared = 0.001, p-value = 0.1388), which proved that the number of individual samples in this study had no significant impact on diversity. However, a minor impact of this sampling cannot be ruled out completely.

Foraging strategies affect the gut microbial composition of spiders

Firstly, we revealed the gut microbiota of spiders among different foraging strategies. The wandering spiders had the highest α diversity, while the ambushing and web-building spiders differed slightly (Fig. 1B, C). Furthermore, the PCoA showed that relatively low explained variation among the three foraging strategy groups, however, the differences between them were still significant (P value = 0.001, Fig. 1D). Then, we tried to reveal the gut microbiota composition among three foraging strategy spiders. Based on the SILVA classifier, the ASVs were annotated as bacteria across 67 phyla, 204 classes, 607 orders, 1161 families, 3525 genera, and 4904 species. At the phylum level (Fig. 1E), Proteobacteria were found to be absolutely dominant, with an average relative abundance of 56.13–68.80%. Additionally, Firmicutes (15.37–17.68%), Bacteroidetes (7.06–10.47%), and Actinobacteriota (3.27–7.45%) also accounted for significant proportions among the three foraging strategy spiders. At the genus level, the most abundant microbiotas were Wolbachia, GCF-002259525, Achromobacter, Ralstonia, and Pseudomonas_E_647464 (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, the most abundant species were Achromobacter denitrificans, GCF-002259525 sp002259525, Ralstonia pickettii, and Wolbachia pipientis (Fig. 1G). From the perspective of gut microbial composition, the main microbiota of the spiders with different foraging strategies were similar, but the relative abundance was significantly different (Fig. 1E–G). We have noticed that some endosymbionts have been annotated in our gut microbiota (e.g., Wolbachia, Cardinium, and Rickettsia), but they only account for a small proportion; the majority are other types of bacteria (Fig. 1F).

Next, we performed LEfSe to identify the differential microbiota between different foraging strategy spiders. We identified 25 differential phyla (Supplementary Data 2), 228 differential genera (Supplementary Data 3), and 210 differential species (Supplementary Data 4) among three foraging strategy spiders (Fig. 1H–J). Among them, the wandering spiders had the largest number of differential microbiotas (134 differential genera and 109 differential species), while web-building had the least (20 differential genera and 19 differential species). In the ambushing spiders, rhizobium, like Mesorhizobium and Bradyrhizobium were more abundant than the other two spiders (Fig. 1I). Moreover, we noticed that the endosymbionts, including Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Rickettsiella, and Cardinium, were all more abundant in the web-building spiders (Fig. 1I).

Furthermore, we also counted the microbes identified in at least 10% of spider individuals of each foraging strategy group and identified the number of specific microbiotas in each foraging strategy spider. We found that ambushing spiders had the most abundant specific microbiotas, with 116 unique genera and 127 unique species (Fig. 1K, L), including Haematomicrobium, Chitinophaga, Luteibacter, and so on. However, the web-building spiders had only eight unique genera and 12 unique species (Fig. 1K, L), including Salinivibrio, Hamiltonella, Tullyiplasma, and so on. Moreover, the wandering spiders had 113 unique genera and 96 unique species, such as Pelospora, Lactococcus, and Proteiniphilum. In addition, ambushing and wandering spiders had the most common microbiotas (510 genera and 317 species), and ambushing and web-building spiders had the least common bacteria (435 genera and 266 species).

The impact of geographical variations

Considering that the samples were collected from two distant regions (with environmental differences), Sichuan (SC) and Guizhou (GZ) (Fig. 1A), we also divided geographical regions to investigate whether there were differences in the gut microbes of spiders in different regions and whether the influence of foraging strategy on gut microbes in different regions was consistent. Firstly, we compared the microbial differences between the two regions (SC vs GZ). The PCoA showed a significant separation between the spiders’ gut microbiota of SC and GZ (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the α diversity of spiders in SC was significantly higher than that of GZ (Fig. 2B, C).

The α diversity of A Shannon index and B Simpson index of spiders’ gut microbiota for different sampling regions of Sichuan (n = 436) and Guizhou (n = 654). C The PCoA results between two sampling regions of spider gut microbiota. D The relative abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level in two sampling regions. E The top 30 differentially abundant gut microbial genera (sorted by LDA values) between the Sichuan and Guizhou regions. The number of microbial (F) genera and (G) species identified in at least 10% of spider individuals of each foraging strategy group (the circle) and the number of specific microbiotas in each foraging strategy group (the common area). The α diversity (Shannon index) of spiders’ gut microbiota for different sampling regions of (H) Sichuan (SC, ambushing: n = 67; wandering: 143; web-building: 226) and (I) Guizhou (GZ, ambushing: n = 32; wandering: 286; web-building: 336) regions. The relative abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level in three foraging strategies of spiders in (J) Sichuan and (K) Guihzou regions. L. The top 30 differentially abundant gut microbial genera (sorted by LDA values) between different foraging strategies in the Sichuan and Guizhou regions, respectively.

Next, we revealed the gut microbial composition in the two regions. The dominant microbiotas were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes, at the phylum level, in both two regions (Supplementary Fig. 2A). However, at the genus level, we noticed that the dominant microbiotas were Ralstonia, Pseudomonas E 647464, Wolbachia, in SC, while Achromobacter, GCF-002259525, and Wolbachia in GZ (Fig. 2D). At the species level, the dominant microbiotas were Ralstonia pickettii, GCF-002259525 sp002259525, Wolbachia pipientis in SC, and Achromobacter denitrificans, GCF-002259525 sp002259525, Wolbachia pipientis in GZ (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Significant composition differences were observed in SC and GZ spider gut microbes, so we further performed LEfSe differential analysis. The results showed that 25 phyla (Supplementary data5), 349 genera (Supplementary data6), and 406 species (Supplementary data7) exhibited significant relative abundance differences between SC and GZ, with most of them being higher in GZ (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). For example, 23 phyla had significantly higher relative abundance in GZ, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and so on. However, only Proteobacteria and Armatimonadetes were higher in SC (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Besides, 282 genera were more abundant in GZ, including endosymbionts (Cardinium, Rickettsia, Rickettsiella), and probiotics (Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Lactobacillus), while the other 67 genera (e.g., Ralstonia, Pseudomonas, and Stenotrophomonas) were more abundant in SC (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, we found that the number of specific microbes in GZ (318 genera and 294 species) was significantly higher than that in SC (60 genera and 64 species) (Fig. 2F, G), consistent with the diversity results.

In addition, we further explored the effect of the foraging strategy on the gut microbiota of samples in GZ and SC, respectively. The results of α diversity showed different patterns in the two regions, that is, SC had the highest gut microbial diversity of ambushing spiders and the lowest gut microbial diversity of web-building spiders (Fig. 2H and Supplementary Fig. 2E), while GZ had the highest diversity of wandering spiders and no significant difference between ambushing and web-building (Fig. 2I and Supplementary Fig. 2F). However, the PCoA showed significant but rare differences among different foraging strategies both in SC and GZ (Supplementary Fig. 2G, H). Then, from the perspective of microbial composition, the dominant microbes of different foraging strategies in the two regions were similar, but with abundant differences, and the bias between the two regions was obvious (Fig. 2J, K and Fig. S3). The relative abundance of major microbiotas in the gut of ambushing spiders was obviously different between SC and GZ groups, which were dominated by Aquirickettsiella and Wolbachia in GZ, whereas Wolbachia and Ralstonia in SC (Fig. 2J, K). The LEfSe difference analysis also found that the ambushing spiders had the largest number of differential microbes in SC, while the wandering spiders had the highest number in GZ (Fig. 2L and Fig. S4). Furthermore, we noticed that the endosymbionts, like Wolbachia, Rickettsiella, and Cardinium, were more abundant in the web-building spiders than in ambushing and wandering spiders in GZ, but no difference in SC (Fig. 2L).

High endosymbiont infection rate in spiders

Endosymbionts were an essential component of the spider gut microbiota, and we detected a high relative abundance of endosymbionts in spider gut microbes. (Fig. 1F, G). We noticed that there were four common spider endosymbionts, including Wolbachia, Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Rickettsiella. Thus, we separately calculated their infection rates to explore whether their foraging strategy and region had an impact on their infection rates. First, we calculated the endosymbiont infection rate in all samples and found that Wolbachia had the highest infection rate (85.14%), followed by Cardinium (50.55%), Rickettsia (38.07%), and Rickettsiella (24.59%). Moreover, we found that 980 (89.91%) spider individuals were infected with at least one endosymbiont, and 88 (8.07%) individuals were infected with all four endosymbionts (Fig. 3A).

A The number spider individual with the infection of four common endosymbionts, including Wolbachia, Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Rickettsiella. The common area represents the number of individuals, which simultaneously infected with multiple endosymbionts. B The prevalence of four endosymbionts in three different foraging strategy spiders. C The prevalence of four endosymbionts in two regions.

Next, we calculated the endosymbiont infection rate in spiders with different foraging strategies and regions. We found that the infection rates were highest in web-building spiders in all four endosymbionts, and were also higher in wandering spiders than in ambushing spiders, except Rickettsiella (Fig. 3B). Consistently, the relative abundance of endosymbionts was also found to be the highest in web-building spiders (Fig. 1I). In different regions, four endosymbiont infection rates were all obviously higher in GZ than in SC, especially Cardinium (Fig. 3C). We further calculated the endosymbiont infection rate in different regions of the same host from the level of family, genus, and species to exclude the influence of host taxonomy on the infection rate. According to the sample size, we selected three hosts at each level and found that the infection endosymbiont rate of GZ was almost always higher than that of SC, especially Cardinium (Supplementary Data 8).

Geographical distance and precipitation had significant effects

Considering the obvious differences in the gut microbiotas of spiders from different regions, we further presented the microbial profiles of different sampling sites. The PCoA showed that the samples from the same sampling sites were aggregated (Fig. 4A). The results of α diversity showed that there were obvious differences in different sites between SC and GZ, and the differences were also significant in the same region, especially in SC (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Data 9). In addition, different foraging strategies had a significant impact on the α diversity of spiders’ gut microbiota in different sampling sites, especially those in ambushing spiders (Fig. S5 and Supplementary Data 10). Next, we also examined the effect of the geographical distance of the sampling site on the diversity of gut microbiota in spiders (Supplementary Data 11). It was found that the closer the sampling sites of spiders were, the more similar the α diversity levels of their gut microbiota were (Fig. 4C).

A The PCoA results between 11 sampling sites of spider gut microbiota. B The α diversity (Shannon index) of spider gut microbiota in 11 sampling sites (FJS: n = 169; QRG: n = 146; XS: n = 339; JA: n = 37; JGS: n = 48; JLG: n = 101; LG: n = 107; LM: n = 53; LQS: n = 32; QCS: n = 37; XLXS: n = 21). C The geographical distance (Km) of the sampling site on the microbial diversity similarity (1-Bary-Curits) of gut microbiota in spiders, with Mantel test. D The average monthly temperature throughout the year in the region of GZ and SC. E The average monthly precipitation throughout the year in the region of GZ and SC. F The correlation between the α diversity (Shannon, Simpson, Faith, and Chao1) of gut microbiota in spiders and the environmental factors (precipitation and temperature). The number within the circle represents the correlation coefficient. The larger the number, the higher the correlation. Blue indicates a positive correlation. G The relationship between α diversity (Shannon index) of spider gut microbiota and the precipitation. H The relationship between α diversity (Simpson index) of spider gut microbiota and the precipitation.

In addition to geographical distance, we also explored the impact of climate on the gut microbiota of spiders. We obtained the temperature and precipitation data of each sampling site, as well as the other 19 factors related to temperature and precipitation (see methods). We found that the average monthly temperature throughout the year in the GZ region was almost always lower than that in the SC region (Figs. 4D and S6). The precipitation in the SC region was lower than that in the GZ in most months, but it entered the flood season from July to September, during which the precipitation was significantly higher than that in the GZ region. The flood season in the GZ region was mainly from May to July (Fig. 4E). Subsequently, we conducted a correlation analysis of precipitation and temperature with the α diversity of gut microbiota in all spiders and found that rainfall was significantly positively correlated with the α diversity (Figs. 4F–H and S7), while temperature was not significantly correlated with the α diversity. These results suggest that the higher the precipitation in a region, the higher the α diversity of the gut microbiota of spiders.

Overall, we found that geographical distance and precipitation significantly affected the composition of the gut microbiota of spiders. However, the limited geographic regions sampling makes this part of the study preliminary.

Ecological processes and enterotypes of the spider gut microbiota

To better understand the driving forces of the spider’s gut microbial composition, we further explored the microbial community assembly processes of the spider by evaluating deterministic processes (homogeneous selection and heterogeneous selection) and stochastic processes (homogeneous dispersal, dispersal limitation, and ecological drift). We performed phylogenetic bin-based null model analysis (iCAMP) to determine the potential contribution of deterministic and stochastic processes to bacterial community assembly. The quantification of ecological processes revealed that stochastic processes predominantly governed the assembly of spiders’ gut microbiota (average proportion: 80.14%) (Fig. 5A, B), where dispersal limitation (average proportion: 41.07%) and ecological drift (average proportion: 38.59%) were the most dominant ecological processes, and homogenizing selection, which belongs to deterministic processes (average proportion: 17.93%), also had a relatively high proportion. Among spiders with different foraging strategies, we found that the web-building spiders had the highest levels of homogeneous selection and drift, but the lowest level of dispersal limitation (Fig. 5A). In terms of different sampling regions, the level of homogeneous selection in SC was significantly higher than that in GZ, while the level of drift was significantly lower than that in GZ (Fig. 5B).

A The microbial community assembly processes of the spider in three different foraging stategies, by evaluating deterministic processes and stochastic processes. DL dispersal limitation, DR ecological drift, HD homogeneous dispersal, HeS heterogeneous selection, HoS homogeneous selection. B The microbial community assembly processes of the spider in two different sampling regions, by evaluating deterministic processes and stochastic processes. C The PCoA of spider gut microbiotas’ enterotype. D The relative abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level in four enterotypes. E The count of spider individuals in each enterotype in different foraging strategies. F The count of spider individuals in each enterotype in different sampling regions.

Lastly, we conducted the enterotype for the gut microbiota of the spiders to further reveal the difference in the spiders’ microbial composition. We found that the gut microbiotas were divided into four enterotypes at the genus level (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Data 11). Among them, the majority of the samples belonged to the mixed type (Type 1, 732 individuals), with Achromobacter (13.01%) as the dominant microbe. The other three types were dominated by Wolbachia (Type 2, 111 individuals), Ralstonia (Type 3, 130 individuals), and GCF-002259525 (Type 4, 117 individuals), respectively, all having relative abundances exceeding 66% (Fig. 5D). We conducted further statistical analysis on the distribution of different enterotypes across various foraging strategies and regions. The results revealed that, except for the Ralstonia-dominated type (Type 3), which was solely present in the SC region, the remaining enterotypes exhibited no distinct biases concerning foraging strategy or region (Fig. 5E, F).

Discussion

Spiders, as important predators in terrestrial ecosystems, exhibit high diversity and wide distribution, and occupy significant ecological niches1,2,3. However, in contrast to the extensive studies on the gut microbiota of animals like primates, mice, fish, and birds31,32,33,34,35, research on the gut microbiota of spiders remains notably scarce. Thus, we collected an extremely large sample, including 1090 spider individuals representing 35 families, 155 genera, and 288 species from southwestern China, to research the gut microbiota of spiders. This study aimed to comprehensively explore the gut microbiota of spiders and investigate how foraging strategies and environmental factors of spiders shape the composition and characteristics of the gut microbiota.

Almost all spiders are carnivorous, but regardless of their body sizes, they all exhibit different lifestyles and foraging strategies. Web-building spiders usually devote most of their energy to the selection of foraging sites and the construction of webs. Compared with wandering spiders, they can reduce their metabolic rate and breathing rate to improve tolerance36. In contrast, wandering spiders need to hunt their prey actively, proactively, and extensively. This hunting lifestyle greatly increases the frequency of their contact with the surrounding environment, and the sources of their prey are more abundant and diverse37. At the same time, they also need to consume more energy. The foraging tactics of ambushing spiders are somewhat similar to those of web-building spiders, both waiting for prey to arrive before catching them. The most notable difference between the two is that the former mostly waits for an ambush at the hole entrance, while the latter mainly relies on the webs as a hunting tool. Studies have found that web-building spiders in farmlands almost exclusively fed on flying insects, while wandering spiders had a higher variation in preying on their prey38,39. There are certain differences in the foraging intensity and prey types among different life types of spiders. When comparing the gut microbiota of spiders with different foraging strategies, the gut microbial diversity and the number of differential microbes of the wandering spiders were both significantly higher than those of ambushing and web-building spiders, and both the diversity and the number of differential microbes in the web-building spiders were the lowest (Fig. 1C, D, H–J). These results could potentially be caused by the fact that the heightened mobility, expanded foraging ranges, and elevated metabolic rates of wandering spiders increase their exposure frequency and diversity of environmental microbial sources, thus allowing the spiders to have more chances to acquire a variety of microbes20,21,40. In contrast, certain spider webs possess antibacterial properties. To a certain degree, these properties impede web-building spiders from obtaining microbiotas from the environment41,42. Additionally, as spider webs are suspended on the ground, the chances of spiders coming into contact with soil microorganisms are also reduced43. Collectively, these factors may account for the relatively lower richness and diversity of the gut microbiota observed in web-building spiders.

Next, the Mantel test between the sampling geographical distance and the spider gut microbial similarity and the comparison of differences between different regions proved that geographical location also has a significant impact on the gut microbiota of spiders. It can generally be considered as an approximate value of the comprehensive impact of environmental factors, including the local natural history, climatic conditions, and resources of flora and fauna44, The integrated effect of these factors determines the composition of the regional pool. Armstrong et al.45 found that within the Hawaiian Islands, the composition of the spider gut microbiota was relatively conserved, and the species differentiation caused by geographical isolation had little impact on the composition of the spider gut microbiota. He speculated that the spider gut is mainly occupied by environmentally derived microorganisms. Our inference is consistent with Armstrong: spiders can directly or indirectly obtain microbial resources from the environment, and these microorganisms may simply follow opportunistic colonization within the spider. The similarity of spider microorganisms at the same geographical location may be due to the overlap of the regional pool. Considering the limited ability of gut microorganisms among individual spiders to spread, and the possibility that they do not rely on specific microorganisms to enhance their fitness, it is reasonable that the spider gut microbiota is dominated by environmental microorganisms. However, contrasting with the findings by Tyagi et al.46, who reported no association between spider gut microbiota and geographical location in Indian species, starkly oppose our conclusions, but their study lacked credible statistical tests, and the homogeneity of their study environment is relatively high, which may lead to an underestimation of its sensitivity to geographical factors45.

Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was found between precipitation and the gut microbiota of spiders. Research has demonstrated that precipitation enhances the microbial diversity of soil47 and the overall biodiversity in the environment48,49. Southwest China, where the SC and GZ regions are nestled, is recognized as one of the 34 biodiversity hotspots in the world and plays a vital role in global biodiversity conservation50. Furthermore, drought has also been proven to affect the intestinal microorganisms of certain wild animals, like common cranes51, Anolis Lizards52, and spiders14. Chen et al.14 found that the gut microbial diversity of wolf spiders decreased in simulated drought-stressed conditions. Therefore, we speculated that the abundant precipitation in this region has promoted the increase of soil microorganisms and the enrichment of overall biodiversity, and thus has also contributed to the increase in the diversity of gut microbiota in spiders. Moreover, the augmentation of soil microorganisms due to abundant precipitation also indirectly validates the rationale behind the high gut microbial diversity and higher abundance of common soil microbiotas such as Mesorhizobium53, Bradyrhizobium54, and Pseudonocardia55, observed in ambushing spiders. However, we lack the gut microbiota data of spiders collected in arid regions. This is also a limitation of our study on the impact of precipitation on the gut microbiota of spiders.

The dominant bacterial phyla in the spider gut microbiota--Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria--mirror those found in most arthropods56. Notably, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in spider gut microbiota exceeds that of other arthropod groups57, which often correlates with pathogenic infections and intestinal dysbiosis in vertebrates58. As a previous study pointed out, the carrying of endosymbionts would affect the abundance of other microorganisms in the spider’s gut microbiota59, and played multifaceted roles, including manipulating host reproduction, supplying essential nutrients, and aiding in immune defense mechanisms for arthropods29,60. We also found that our spider samples widely harbored high-abundance endosymbionts, consistent with past studies28, and significantly higher than the estimated endosymbiont infection rate in arthropods (~30%). Unlike some monophagous or oligophagous arthropods61,62,63,64, spiders have diverse food sources and rich nutrition. This makes the “nutritional supply” hypothesis insufficient to explain their dependency on endosymbionts, even though some studies have speculated that co-infection with Wolbachia and Cardinium may be beneficial for spiders in synthesizing fats and free amino acids65. Besides, the frequent cannibalism in spiders likely serves as an underappreciated vector for horizontal endosymbiont transfer, particularly given the observed high infection rates across populations27. Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying endosymbiont infection in spiders has yet to be reasonably elucidated. In this study, we found that the endosymbiont infection rates of spiders with different foraging strategies were significantly different. The web-building spiders had the highest infection rate, while the ambushing spiders had the lowest. Moreover, there are significant differences in infection rates among different regions. The infection rates of the same host vary significantly in different regions. It suggests that both the foraging strategy and the living environment (like precipitation) of spiders have a significant impact on the infection rate of their endosymbionts. In summary, this study further confirmed the universality of endosymbiont infection in spiders and the potencial ecological environment, like precipitation, and foraging strategy driving the colonization of the endosymbionts, but the mechanism of endosymbiont carriage and functional role in spiders require further experimental verification.

Understanding the mechanisms that control community diversity, function, succession, and biogeography is one of the central issues in microbial ecology66. Existing studies have revealed the community assembly of the gut microbiota in vertebrates and found that stochastic processes (including dispersal limitation and drift) were the main driving factors67,68. Our results also emphasized the importance of stochastic processes in the ecological processes of spider gut microbiota. Even though PCoA analysis showed that the gut microbiota of spiders from the same geographical population cluster well, stochastic processes still dominated the ecological processes between individual spiders, where ecological drift and dispersal limitation were the two main driving forces, which increased the variation and dissimilarity of the gut microbiota among spiders. Besides, the foraging strategies and regions both affected the gut microbial community assembly of spiders. The homogeneous selection of web-building spiders is significantly higher than that of wandering and ambushing spiders. Meanwhile, the α diversity of web-building spiders’ gut microbiota was the lowest, but the infection rate and abundance of endosymbionts were the highest. We speculate that the highly abundant endosymbionts squeeze the colonization of other microbes, thereby leading to a decrease in their microbial diversity and enhancing their homogeneous selection. However, why the abundance and infection rate of endosymbionts are higher in web-building spiders remains to be revealed, and more data related to the diet and environmental sources are needed to support.

This study explored the composition and differences in gut microbiota among spiders with different foraging strategies, as well as the influence of environmental factors. However, this study still has certain limitations. First, due to the difficulties in separating tissues, we used the complete abdomen microbiota for analysis, and therefore, a solid discrimination between, e.g., endosymbionts and gut microbiota was not possible. Future studies should use a better method, separately dissecting intestinal contents, for sample collection. Second, 16S rRNA sequencing was employed in this study. While cost-effective, this technology is inferior to metagenomic sequencing in species identification accuracy, functional analysis, and microbiota coverage. Thus, sequencing techniques could be further improved. Additionally, we only studied the samples in limited geographic regions from southwest China with relatively abundant precipitation, which made this part of the study preliminary. More samples from diverse environments are needed, like arid regions in China (e.g., Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang) with extremely low precipitation.

Conclusions

This study represents the most extensive research to date, involving 1090 samples, to explore the impact of spider foraging strategies on the gut microbiota. This study found that there were significant differences in the gut microbiota of spiders with different foraging strategies: higher diversity and specific microbes in wandering and ambushing spiders but lower in web-building spiders. Notably, the study discovered that spiders exhibit a relatively high infection rate of endosymbiotic bacteria, and both foraging strategies and geographical factors play a role in determining this infection rate. Geographically, microbial similarity declines with distance, and rainfall enhances diversity via soil microbe enrichment. In summary, our study demonstrated that spider gut microbiota assembly was predominantly stochastic, yet modulated by foraging behaviors and environmental precipitation. Our findings not only revealed the factors influencing the spider’s gut microbiota, but also advanced our understanding of predator-microbe dynamics.

Methods

Sample collection, identification, and preparation

Samples were collected from 11 sites in southwestern China (Sichuan and Guizhou Provinces) from May 2022 to April 2023. To encompass a diverse range of species, sampling was conducted across various habitats and microhabitats, including farmlands, forests, shrublands, rocky walls, earth slopes, riversides, and wastelands. To ensure environmental stability at each site, sampling intervals and elevation gradients were carefully controlled within a smaller range. Spider collection primarily used three methods: (1) Shaking method. For spiders inhabiting high places or plants (e.g., leaves, branches), gently vibrate or tap plant stems/branches with a hand or stick to make them fall onto a sterile cloth, then transfer to collection bottles using forceps; (2) Manual collection. For large, slower-moving or easily accessible spiders, wear sterile gloves to capture them by hand (or with forceps for web-building species), then place them in collection bottles; (3) Excavation method. For burrowing or soil/humus-dwelling spiders, use a small shovel to carefully dig around burrows, then collect using forceps and transfer to collection bottles. No chemical reagents were used during the collection process. The spiders were stored individually in appropriate glass tubes or collection boxes according to their body size to prevent cannibalism and cross-contamination of microorganisms. Each spider was kept individually with only a small amount of sterile water to ensure survival. After collection, the samples were brought back to the laboratory and stored for 72 h to eliminate interference from undigested food-borne microorganisms. After this period, the spiders were directly immersed in 95% ethanol and stored at −20 °C until identification and dissection.

Spider species were identified using both the morphological classification method and the DNA barcoding technique. Spiders that were subadults, new species, or undetermined species were classified to the genus level. Sample preparation was conducted on an aseptic laminar flow bench: first, they were rinsed with 75% ethanol for at least 1 minute to remove residual surface microorganisms, then transferred to pre-sterilized petri dishes with an alcohol lamp burning beside the dish at all times. Finally, the spider’s opisthosomas were removed using sterilized forceps and dissecting needles, and then quickly transferred to a centrifuge tube filled with 75% ethanol. It should be noted that: (1) If a spider’s body is large enough (>10 mm), one individual is considered as one sample; if the spider’s body is small (<10 mm), multiple individuals of the same species are pooled into one sample, with up to 15 individuals per sample. (2) The method of characterizing the gut microbiota by the microorganisms contained in the spider’s opisthosoma (abdomen) has been widely used and recognized in related studies4,69,70. Although the spider’s opisthosomas also include organs such as the heart, silk glands, and ovaries, the spider’s stomach is located in the cephalothorax, and its intestine is located in the opisthosomas, which serves as the primary colonization site for microorganisms. Other organs in the opisthosoma of spiders exhibit a simple microbial composition with a low abundance of microbiota4,69,70. Therefore, our study adopts the established sampling protocol. None of the spiders used in this study were endangered or protected species. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University (Project No.: SCU250905001).

DNA extractions and high-throughput sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from these samples via the CTAB method, and its concentration and purity were assessed using a 1% agarose gel. DNA samples were then quantified and diluted to a standard concentration of 1 μg/μL with sterile water. The quantified method of DNA was as follows: the sample with a brightness level nearly identical to that of the standard sample is the one containing 50 ng of nucleic acid. Based on the comparison of the sample’s brightness with that of the standard sample and the calculation of the sample’s concentration using the loading volume, multiple gradient dilutions are then carried out. The 16S rRNA genes’ variable regions V3–V4 were amplified using primers 341F (CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG) and 806R (GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT)71, each with an attached barcode (to distinguish different samples), to enable high-throughput sequencing. PCR was performed with a 15 μL volume of Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix, incorporating 0.2 μM of each primer. The thermal cycling profile initiated with an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s, concluding with a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were visualized by mixing with an equal volume of 1× loading buffer containing SYBR green and subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. Bands of equidensity were purified using the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Sequencing libraries were prepared with the TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA), incorporating unique index codes for each sample. Library quality was evaluated using the Qubit@2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Finally, the library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform and 250 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Sequence analysis

Raw sequencing data generated by the Illumina platform were processed using QIIME 2 v2021.572 software. The paired-end sequences underwent a series of preprocessing steps, including truncation, dereplication, merging, and denoising through the Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm (DADA2) pipeline73. This approach generated the ASV table and the representative sequences for each ASV. The representative sequences were subsequently utilized to construct a phylogenetic tree using the FastTree pipeline74, which provided an estimation of phylogenetic relationships among the ASVs. ASVs were annotated by the pre-trained Naive Bayes classifier based on the SILVA database (v2022.10)75 at a confidence level of 70% chloroplast, mitochondrial, and undefined reads were subsequently manually removed according to the annotation table. The ASV rarefaction curves were plotted using Origin software (v 2019b) to evaluate the sequencing quality, filter out microbial samples that did not meet the sequencing depth criteria, and rarefy the sequences for subsequent beta diversity-related analyses. The alpha diversity (Chao1, Shannon, and Faith’s PD), beta diversity (unweighted UniFrac distances), and Analysis of Similarities (ANOSIM) were calculated using the diversity pipeline in QIIME2.

Statistics and reproducibility

To compare the α-diversity between the different groups, we performed a Wilcoxon test between two groups and Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test among three groups. β-diversity was visualized by Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distance and tested by adonis using package vegan v2.6-10 76. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfse) was used for finding differentially abundant microorganisms by package microeco v1.15.077, and a relatively strict linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score was set as ≥2. Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 v3.5.178 and ggpubr v0.6.079 packages in R. The Venn diagrams were plotted by jevnn (https://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/index.html)80.

Acquisition and analysis of environmental factors

The longitude and latitude information of the sampling points were transformed into a geographical distance matrix using the R package geosphere v1.5-2081. Meanwhile, the Bray-Curtis distance of the sample microbiota was calculated by the R package vegan v2.6-1076. Then, the Mantel test was used to examine the correlation between the microbial similarity (1-Bray-Curtis) and the geographical distance matrix, utilizing vegan v2.6-10.

The datasets of sampling sites’ temperature and precipitation were provided by the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn). The monthly average precipitation data from 2019 to 2023 were used to represent the precipitation conditions of each month. The monthly average temperature in 2022 was used to represent the temperature of each month. Next, the correlation between the microbial diversity index and temperature and precipitation was calculated using the R package corrplot v0.9582, and the scatter-fitting plots of the diversity index and temperature and rainfall were plotted using the linear regression model.

Quantification of the gut microbiota assembly process

For the investigation of the gut microbiome assembly process in spiders, the assembly process of the spider gut microbiome was quantified using a null-model approach. Firstly, we used the genus level of the gut microbiota of spiders, and the phylogenetic tree corresponding to the representative sequences was constructed and output using the FastTree plugin74. The iCAMP package v1.5.1283 was used to calculate ecological processes. Initially, the observed taxa were binned into different groups based on their phylogenetic relationships. Subsequently, null-model analysis was performed on phylogenetic diversity using the beta net relatedness index (βNRI) with 999 randomizations, and the Raup-Crick (RC) index was calculated to delineate ecological processes83. The ecological processes were categorized based on the βNRI and RC values as follows: homogenizing selection was inferred when βNRI < −1.96, heterogeneous selection was inferred when βNRI > −1.96, homogenizing dispersion was inferred when |βNRI| ≤ 1.96 and RC < −0.95, and dispersal limitation was inferred when |βNRI | ≤ 1.96 and RC > 0.95, and ecological drift was inferred when |βNRI| ≤ 1.96 and |RC| ≤ 0.95. Finally, all bins within the community groups were integrated to calculate the proportion of ecological processes among samples.

Enterotype analysis of the spider

An enterotype analysis was completed using the Wekemo Bioincloud (https://www.bioincloud.tech)84. Based on the Jensen-Shannon distance between samples, clustering was carried out using the partition around the Center Point (PAM) algorithm, and the optimal number of classifications was determined by the Calinski-Harabasz (CH) index. The visualization was used with ggplot2 v3.5.178.

Ethics declarations

None of the spiders used in this study were endangered or protected species. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University (Project No.: SCU250905001).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequencing reads from this study have been submitted to the China National GeneBank Database (CNP0007324; CNGBdb, https://db.cngb.org/) and Genome Sequence Archive database (PRJCA051897: CRA034046; GSA, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/).

Code availability

The analysis code has been submitted to GitHub (https://github.com/WJiao95/16S-spider) and Zenodo85 (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17640349).

References

Gao, Y., Wu, P. F., Cui, S. Y., Ali, A. & Zheng, G. Divergence in gut bacterial community between females and males in the wolf spider Pardosa astrigera. Ecol. Evol. 12, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8823 (2022).

Zhang, L. H., Zhang, G. M., Yun, Y. L. & Peng, Y. Bacterial community of a spider, Marpiss magister (Salticidae). 3 Biotech 7, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0994-0 (2017).

Zhang, L. H., Yun, Y. L., Hu, G. W. & Peng, Y. Insights into the bacterial symbiont diversity in spiders. Ecol. Evol. 8, 4899–4906 (2018).

Kennedy, S. R., Tsau, S., Gillespie, R. & Krehenwinkel, H. Are you what you eat? A highly transient and prey-influenced gut microbiome in the grey house spider Badumna longinqua. Mol. Ecol. 29, 1001–1015 (2020).

Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 55–71 (2021).

Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W. & Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148, 1258–1270 (2012).

Weng, M. & Walker, W. A. The role of gut microbiota in programming the immune phenotype. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 4, 203–214 (2013).

Brown, E. M., Clardy, J. & Xavier, R. J. Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host Microbe 31, 173–186 (2023).

Ross, F. C. et al. The interplay between diet and the gut microbiome: implications for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 671–686 (2024).

Sun, J. A. et al. Gut microbiota as a new target for anticancer therapy: from mechanism to means of regulation. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00678-x (2025).

Muegge, B. D. et al. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 332, 970–974 (2011).

Yatsunenko, T. et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486, 222 (2012).

Yao, R. et al. Fly-over phylogeny across invertebrate to vertebrate: the giant panda and insects share a highly similar gut microbiota. Comput Struct. Biotechnol. 19, 4676–4683 (2021).

Chen, L. J., Li, Z. Z., Liu, W. & Lyu, B. Impact of high temperature and drought stress on the microbial community in wolf spiders. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe 283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116801 (2024).

Rezác, M., Rezácová, V. & Heneberg, P. Differences in the abundance and diversity of endosymbiotic bacteria drive host resistance of a dominant spider of central European orchards, to selected insecticides. J. Environ. Manag. 373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123486 (2025).

Perez-Lamarque, B., Krehenwinkel, H., Gillespie, R. G. & Morlon, H. Limited evidence for microbial transmission in the phylosymbiosis between Hawaiian spiders and their microbiota. mSystems 7, e0110421 (2022).

Meehan, C. J., Olson, E. J., Reudink, M. W., Kyser, T. K. & Curry, R. L. Herbivory in a spider through exploitation of an ant-plant mutualism. Curr. Biol. 19, R892–R893 (2009).

Szymkowiak, P. & Grabowski, P. Morphological differentiation of ventral tarsal setae and surface sculpturing of theraphosids (araneae: theraphosidae) with different types of lifestyles. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 115, 314–323 (2022).

Ramírez, D. S. et al. Deciphering the diet of a wandering spider (Phoneutria boliviensis; Araneae: Ctenidae) by DNA metabarcoding of gut contents. Ecol. Evol. 11, 5950–5965 (2021).

Uetz, G. W. Foraging strategies of spiders. Trends Ecol. Evol. 7, 155–159 (1992).

Schmitz, A. Respiration in spiders (Araneae). J. Comp. Physiol. B 186, 403–415 (2016).

Groussin, M. et al. Unraveling the processes shaping mammalian gut microbiomes over evolutionary time. Nat. Commun. 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14319 (2017).

Deschasaux, M. et al. Depicting the composition of gut microbiota in a population with varied ethnic origins but shared geography. Nat. Med. 24, 1526 (2018).

Rocafort, M. et al. HIV-associated gut microbial alterations are dependent on host and geographic context. Nat. Commun. 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44566-4 (2024).

Weng, H. D. et al. Humid heat environment causes anxiety-like disorder via impairing gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in mice. Nat. Commun. 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49972-w (2024).

Duron, O., Hurst, G. D. D., Hornett, E. A., Josling, J. A. & Engelstädter, J. High incidence of the maternally inherited bacterium in spiders. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1427–1437 (2008).

White, J. A. et al. Endosymbiotic bacteria are prevalent and diverse in agricultural spiders. Micro. Ecol. 79, 472–481 (2020).

Goodacre, S. L., Martin, O. Y., Thomas, C. F. G. & Hewitt, G. M. Wolbachia and other endosymbiont infections in spiders. Mol. Ecol. 15, 517–527 (2006).

Douglas, A. E. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct. Ecol. 23, 38–47 (2009).

Rosenwald, L. C., Sitvarin, M. I. & White, J. A. Endosymbiotic Rickettsiella causes cytoplasmic incompatibility in a spider host. Proc. Biol. Sci. 287, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1107 (2020).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Age-, sex- and proximal-distal-resolved multi-omics identifies regulators of intestinal aging in non-human primates. Nat. Aging 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00572-9 (2024).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Sex- and age-related trajectories of the adult human gut microbiota shared across populations of different ethnicities. Nat. Aging 1, 87 (2021).

Kroon, S. et al. Sublethal systemic LPS in mice enables gut-luminal pathogens to bloom through oxygen species-mediated microbiota inhibition. Nat. Commun. 16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57979-0 (2025).

Minich, J. J. et al. Host biology, ecology and the environment influence microbial biomass and diversity in 101 marine fish species. Nat. Commun. 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34557-2 (2022).

Schmiedová, L., Tomásek, O., Pinkasová, H., Albrecht, T. & Kreisinger, J. Variation in diet composition and its relation to gut microbiota in a passerine bird. Sci. Rep. 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07672-9 (2022).

Welch, K., Haynes, K. & Harwood, J. Prey-specific foraging tactics in a web-building spider. Agric. Forest Entomol. 15, https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12023 (2013).

Pyke, G. H. Optimal foraging theory - a critical review. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 15, 523–575 (1984).

Nyffeler, M. Prey selection of spiders in the field. J. Arachnol. 27, 317–324 (1999).

Ludy, C. Prey selection of orb-web spiders (Araneidae) on field margins. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 119, 368–372 (2007).

Mishra, A., Kumar, B. & Rastogi, N. Predation potential of hunting and web-building spiders on rice pests of Indian subcontinent. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sc. 41, 1027–1036 (2021).

Wright, S. & Goodacre, S. L. Evidence for antimicrobial activity associated with common house spider silk. Bmc Res. Notes 5, 326 (2012).

Tahir, H. M., Qamar, S., Sattar, A., Shaheen, N. & Samiullah, K. Evidence for the antimicrobial potential of silk of cyclosa confraga (Thorell, 1892) (Araneae: Araneidae). Acta Zool. Bulg. 69, 593–595 (2017).

Sarkar, A. et al. Microbial transmission in animal social networks and the social microbiome. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1020–1035 (2020).

Ramalho, M. O., Bueno, O. C. & Moreau, C. S. Microbial composition of spiny ants (Hymenoptera:Formicidae:Polyrhachis) across their geographic range. BMC Evol. Biol. 17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-0945-8 (2017).

Armstrong, E. E. et al. A holobiont view of island biogeography: Unravelling patterns driving the nascent diversification of a Hawaiian spider and its microbial associates. Mol. Ecol. 31, 1299–1316 (2022).

Tyagi, K., Tyagi, I. & Kumar, V. Interspecific variation and functional traits of the gut microbiome in spiders from the wild: the largest effort so far. Plos ONE 16, e0251790 (2021).

Qiu, Y. P. et al. Climate warming suppresses abundant soil fungal taxa and reduces soil carbon efflux in a semi-arid grassland. Mlife 2, 389–400 (2023).

Jactel, H. et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationships in forests: climate matters. Biol. Lett. 14, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2017.0747 (2018).

Niu, B. & Fu, G. Response of plant diversity and soil microbial diversity to warming and increased precipitation in alpine grasslands on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau - A review. Sci. Total Environ. 912, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168878 (2024).

Mittermeier, R. A., Turner, W. R., Larsen, F. W., Brooks, T. M. & Gascon, C. Global Biodiversity Conservation: The Critical Role of Hotspots.in Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas (eds Frank E. Zachos & Jan Christian Habel) 3–22 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011).

Wang, C. Y. et al. Extreme drought shapes the gut microbiota composition and function of common cranes wintering in Poyang Lake. Front. Microbiol. 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1489906 (2024).

Williams, C. E. et al. Sustained drought, but not short-term warming, alters the gut microbiomes of wild anolis lizards. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e0053022 (2022).

Du, X. Y. et al. Proximity-based defensive mutualism between Streptomyces and Mesorhizobium by sharing and sequestering iron. ISME J. 18, https://doi.org/10.1093/ismejo/wrad041 (2024).

Shah, V. & Subramaniam, S. Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110: a representative model organism for studying the impact of pollutants on soil microbiota. Sci. Total Environ. 624, 963–967 (2018).

Riahi, H. S., Heidarieh, P. & Fatahi-Bafghi, M. Genus Pseudonocardia: what we know about its biological properties, abilities and current application in biotechnology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 132, 890–906 (2022).

Yun, J. H. et al. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 5254–5264 (2014).

Gurung, K., Wertheim, B. & Salles, J. F. The microbiome of pest insects: it is not just bacteria. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 167, 156–170 (2019).

Shin, N. R., Whon, T. W. & Bae, J. W. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 496–503 (2015).

Vanthournout, B. & Hendrickx, F. Endosymbiont dominated bacterial communities in a dwarf spider. Plos ONE 10, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117297 (2015).

Jing, X. F. et al. The bacterial communities in plant phloem-sap-feeding insects. Mol. Ecol. 23, 1433–1444 (2014).

Baumann, P. Biology of bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 155–189 (2005).

Weiss, B. L. et al. Interspecific transfer of bacterial endosymbionts between tsetse fly species: infection establishment and effect on host fitness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 7013–7021 (2006).

Wang, S., Hua, X. G. & Cui, L. Characterization of microbiota diversity of engorged ticks collected from dogs in China. J. Vet. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.4142/jvs.2021.22.e37 (2021).

Baumann, P. et al. Genetics, physiology, and evolutionary relationships of the Genus Buchnera - intracellular symbionts of aphids. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49, 55–94 (1995).

Li, C. F., He, M., Yun, Y. L. & Peng, Y. Co-infection with Wolbachia and Cardinium may promote the synthesis of fat and free amino acids in a small spider, Hylyphantes graminicola. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2019.107307 (2020).

Zhou, J. Z. & Ning, D. L. Stochastic community assembly: does it matter in microbial ecology? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R. 81, https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00002-17 (2017).

Huang, G. P. et al. Global landscape of gut microbiome diversity and antibiotic resistomes across vertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 838, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156178 (2022).

Pan, B. Z. et al. Geographical distance, host evolutionary history and diet drive gut microbiome diversity of fish across the Yellow River. Mol. Ecol. 32, 1183–1196 (2023).

Sheffer, M. M. et al. Tissue- and population-level microbiome analysis of the wasp spider argiope bruennichi identified a novel dominant bacterial symbiont. Microorganisms 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8010008 (2020).

Millar, E. N., Surette, M. G. & Kidd, K. A. Altered microbiomes of aquatic macroinvertebrates and riparian spiders downstream of municipal wastewater effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 809, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151156 (2022).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 6, 1621–1624 (2012).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581 (2016).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Liu, C., Cui, Y. M., Li, X. Z. & Yao, M. J. Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa255 (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4. (2016).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. R package version 00, https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/ (2023).

Bardou, P., Mariette, J., Escudié, F., Djemiel, C. & Klopp, C. Jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinform. 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-293 (2014).

Hijmans, R. J. Geosphere: spherical trigonometry. R Package Version 1, 5–20 (2024).

Taiyun Wei, V. S. R package ‘corrplot’: visualization of a correlation matrix. R Package Version 0.95, (2024).

Ning, D. L. et al. A quantitative framework reveals ecological drivers of grassland microbial community assembly in response to warming. Nat. Commun. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18560-z (2020).

Gao, Y., Zhang, G., Jiang, S. & Liu, Y. X. Wekemo Bioincloud: a user-friendly platform for meta-omics data analyses. Imeta 3, e175 (2024).

WJiao95/16S-spider: Spider16S-v1.0 v. v1.0 (Zenodo, 2025).

Acknowledgements

We especially thank Professor Hao Yu at the College of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University for the sample collection in Guizhou. We also express our gratitude to the members of our research group for their hard work in the field of sample collection in Sichuan. They are Mian Wei, Qiuqiu Zhang, Qian Chen, Xuewei Geng, Yiting He, Xuelian Weng, Hanlin Wang, and Yuanhao Du. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants NSFC-31750002) for Dr. Yucheng Lin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiao Wang and Shuqiao Wang performed the bioinformatics analyses; Jiao Wang wrote the manuscript; Shuqiao Wang, Chuang Zhou, and Qian Chen collected the samples; Zhenxin Fan and Yuchen Lin revised the manuscript, designed, and supervised the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Marc Domènech, Evgeniia Propistsova, Hirokazu Toju, Jordan Cuff and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Hannes Schuler and Tobias Goris.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Wang, S., Chen, Q. et al. Foraging strategies and geographic factors jointly shape gut microbiota of spiders in the Sichuan and Guizhou regions of China. Commun Biol 9, 86 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09358-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09358-0