Abstract

Identifying the mutant genes that are selected during carcinogenesis is key to identifying candidates for intervention and understanding the processes that promote transformation. Here we applied two selection metrics to study the dynamics of mutational selection in a mouse model of ultraviolet light driven skin carcinogenesis in which multiple synchronous tumors develop in each animal. Sequencing normal skin and tumors over a time course revealed two genetic routes to squamous carcinoma. Nonsynonymous Trp53 mutants were positively selected in both epidermis and tumors and present in 90% of tumors. The remaining tumors carried other oncogenic mutants, including activating Kras mutations. However, other positively selected mutant genes lost their competitive advantage in heavily mutated epidermis and in tumors. We found ten mutant genes under negative selection in normal skin, one of which was also negatively selected in tumors. In addition one gene was negatively selected in tumors but not normal skin. We conclude that analysing selection in normal tissue alongside tumors may resolve the dynamics of selection in carcinogenesis and refine the identification of cancer drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mutant selection and tumor evolution may be inferred retrospectively from cancer genomes1,2,3. However, ageing normal tissues, such as the skin epidermis, develop into a patchwork of positively selected mutant clones, including mutants that occur recurrently in cancer4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Some mutants that drive clonal expansions in normal tissues are oncogenic, but others may be neutral or even inhibit carcinogenesis1,5,16,17. Furthermore, the altered environment within growing tumors may lead to the selection of mutants that are neutral in normal tissues1,16. Most tumor sequencing studies have not analysed the normal tissue from which the tumor arose, so that the oncogenicity of some mutant genes selected in tumors remains unclear.

As well as positively selected mutants, identifying mutant genes that are negatively selected, particularly those negatively selected in tumors, may reveal therapeutic targets18. The existence of negative selection in human tumors was initially controversial, but more recent evidence argues it is widespread2,18,19,20. Many studies of normal tissues have too few synonymous mutations to identify negatively selected genes2. However, those studies with sufficient power have detected negative selection of somatic mutants in normal skin and oral epithelium5,21.

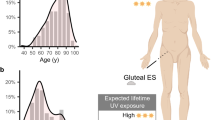

Studying selection in humans is challenging due to variations in the germline, environmental exposures and the age at which lesions develop and the need to sequence both tumor and normal tissue5,10,22,23. These factors may be mitigated in mouse models in which multiple, synchronous lesions develop, facilitating comparison of normal tissue and tumors in the same animal. Here, we used the well-characterized SKH-1 mouse model of UV light-induced skin cancer to explore the dynamics of selection in squamous carcinogenesis24,25,26,27. A key feature of these animals is a high susceptibility to UV-induced tumor formation, which is dependent on a germline mutation in the Hr gene27,28. Repeated exposure to UV light results in skin thickening followed by the development of multiple tumors per animal, which have pathologic features of premalignant actinic keratosis and invasive squamous cell carcinoma24,29. Exome sequencing of SKH-1 cutaneous SCC (cSCC) reveals protein-altering Trp53 mutations are present in most tumors, thus resembling human skin sSCC22,24,30,31,32.

We applied two metrics of selection to normal and tumor tissue. The first was the widely used approach of estimating the ratio of the number of protein-altering (missense, nonsense, essential splice, and insertions/deletions) to synonymous mutations, dN/dS, within each gene, so that for missense mutations, for example,

where n is the total number of mutations of each type across the gene. The implementation of dN/dS used, dNdScv, controls for trinucleotide mutational signatures, sequence composition, and variation in mutation rates between genes, to avoid the known biases in dN/dS estimation2,7. A normalized dN/dS value of 1 is neutral; values significantly above 1 after multiple test correction indicate positive selection, while values below 1 indicate negative selection. In this experiment, dN/dS values reflect the likelihood that a nonsynonymous mutant clone will reach a detectable clone size compared with a synonymous mutant clone in the same gene.

A second measure of selection that may be suitably applied to the current analysis of normal tissue and tumors from a single cell lineage is the ratio of variant allele frequencies (VAF, defined as the proportion of sequencing reads reporting a mutation within each sample) of nonsynonymous and synonymous mutants in each gene (VAF_ns/VAF_s).

Unlike dN/dS, the VAF of all types of nonsynonymous mutations is pooled in the calculation of VAF_ns. If a mutant gene drives clonal expansion, the VAF of nonsynonymous mutants will be significantly larger than the VAF of synonymous mutants in the same gene due to an increased proportion of nonsynonymous mutant cells in the sample, giving a VAF_ns/VAF_S ratio significantly above 1. In contrast, for neutral “passenger” mutations, the VAF_ns/VAF_s ratio will be close to 1.

Here, we assayed the mutational landscape of normal skin epidermis and tumors from a cohort of UV-exposed SKH-1 mice in a time course to explore the dynamics of mutant selection. Two methods of sequencing were employed. To detect mutant clones, we used targeted sequencing of DNA extracted from small samples of normal tissue, where the presence of mutant clones is revealed by mutant reads for each sequenced gene. As mutant clones may only be present in a small fraction of each tissue sample, we used an algorithm, ShearwaterML, to detect mutations. This builds a statistical model of background sequencing errors at each base to identify true variants which have a statistical excess of mutant reads, allowing the detection of mutations present in as few as 1% of the cells in a sample5,7,33. We also measured the mutational burden, the number of mutations per megabase across the genome, using a method called Nanoseq. This is a modification of duplex sequencing, which allows the detection of somatic mutations across a third of the genome with an error rate <5/109 base pairs34. Nanoseq can detect a mutation even if it occurs in just a single DNA molecule in a sample. Importantly for this experiment, Nanoseq estimates of mutational burden are not affected by the expansion of mutant clones.

We found a highly competitive and dynamic mutational landscape during carcinogenesis with two evolutionary trajectories of cSCC formation. Protein-altering Trp53 mutants were under strong positive selection in both normal tissue and tumors. In contrast, other nonsynonymous mutant genes, which are common in human cSCC, drive clonal expansion in normal tissue but appear not to do so within tumors. Negative selection was attenuated in tumors compared with normal tissue.

Results

UV-exposed SKH-1 mouse epidermis becomes densely mutated

A cohort of 20 SKH-1 mice were exposed to three sub-minimal erythema (below sunburn) doses of UV radiation per week. Animals were culled after 8 to 27 weeks of UV irradiation of the back (dorsal) skin (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Epidermal histology confirmed the expected increase in epidermal thickness in the UV-exposed dorsal skin (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b)29. The skin was collected, and tumors were dissected. Part of each lesion was removed for histology, after which spaced cryosections from the remaining tumor were imaged and sequenced (Methods). Wholemounts of normal epidermis from dorsal and ventral skin were then prepared, imaged to confirm the absence of tumors and sent for targeted sequencing to a median depth of 931x coverage for 74 genes associated with squamous cancer (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Data 1, 2).

a Protocol. Following sub-minimal erythema UV dose epidermis and tumors are dissected and sequenced as shown. b, c Mutational burden in irradiated dorsal epidermis. b Substitutions/Megabase, c double base substitutions/megabase, both determined by NanoSeq. Each dot represents one mouse, red bar indicates the median. Source Data: Supplementary Data 3d Density of mutations, each dot is a different epidermal grid sample, grouped by mouse. Source data: Supplementary Data 3, 5.

We began by analysing the genomic alterations in normal skin over time using Nanoseq. The mutational burden in dorsal skin rose progressively, reaching a median of over 30 single-base substitutions (SBS)/Megabase by 24 weeks (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 3). The mutational burden estimates by NanoSeq were 20 SBS/Mb higher than those derived from targeted sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 1e). For comparison, the median mutational burden in histologically normal, sun-exposed, middle aged, human skin estimated from targeted sequencing typically ranges from 10–20 SBS/Mb, similar to the burden at the 8-week time point (Supplementary Fig. 1f), but may be several fold higher in patients with multiple keratinocyte cancers5,11,12.

The mutational spectrum was dominated by C > T transitions, consistent with UV exposure, in both targeted and Nanoseq sequencing of the epidermis (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Data 4)7. The mutational spectra from targeted and Nanoseq sequencing were highly correlated (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Double Base Substitutions (DBS) also increased with UV exposure and 35% of the changes were CC > TT, in line with previous observations (Fig. 1c). The ventral epidermis, which was not directly exposed to UV light, remained sparsely mutated throughout the experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Non-UV exposed control mice also showed very few mutations (Supplementary Data 5).

Accompanying the changes in mutational burden we detected a progressive increase in the number of mutations per mm2 of dorsal epidermis with the duration of irradiation (Fig. 1d). Across all time points, the total number of SBS, DBS and indels detected in the dorsal epidermis was 94138, 2126, and 471 respectively in a total area of 10.26 cm2 epidermis (Supplementary Data 5).

Selection of mutant genes in UV-exposed epidermis

To explore the selection of mutant genes in the epidermis, we first determined the dN/dS ratio for each sequenced gene7,35. As missense dN/dS ratios may be misleading if both gain and loss of function mutants occur in the same gene, we only considered the dN/dS for nonsense and essential splice mutants for determining which mutant genes were under selection5. After correction for mutational spectrum, genomic context and multiple testing, eight mutant genes, including Trp53, Notch1, Notch2, Fat1, and Ajuba emerged as being under positive selection in the epidermis (dNdSnonsense/essential splice >1.3, q < 0.01) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 6). The human equivalents of these mutant genes are positively selected in sun-exposed human epidermis5,6,7. Mutants of the skin tumor suppressor histone lysine methyltransferase Kmt2c, atypical cadherin Fat2, and the tyrosine kinase insulin receptor family gene Ros1 were also under positive selection (Fig. 2a)36.

a, b Nonsynonymous: synonymous (dN/dS) ratios in dorsal skin. Mutations in all mice across all time points are pooled; 1 is neutral. a Genes under positive selection (q < 0.01 and dNdS ratio >1.3 for nonsense/splice mutations). b Negatively selected genes (q < 0.01 and dN/dS ratio <0.6 for nonsense/ splice mutations). Source Data: Supplementary Data 6. c–e Nonsynonymous (black points) and synonymous (gray points) VAF distribution for Trp53 (c), Notch1 (d), and Fat1 (e), p values determined by two-tailed Wilcoxon test. Red lines indicate the median. Source Data: Supplementary Data 7. f–h Percentage area of dorsal epidermis colonized by cells mutant for Trp53 (f), Notch1 (g), and Fat1 (h), estimated from summed variant allele frequency at each time point. Data shows the average across all mice for each time point, n = 4 mice for each time point. Upper and lower bounds reflect uncertainty in copy number and multiple mutations per cell. Source Data: Supplementary Data 8.

The large number of mutants enabled us to detect negatively selected mutant genes. A dN/dS analysis revealed ten genes under negative selection in epidermis (dN/dSnonsense/essential splice <0.6, q < 0.01, Fig. 2b and Supplementary Data 6). These included inactivating mutations of the growth factor receptors Egfr, Erbb2, Erbb3, and their downstream signaling intermediates Mtor and Pik3ca in keeping with the pro-proliferative function of the wild-type genes in the epidermis37,38,39. Mutations disrupting the epigenetic regulators Ep300 and Smarca4, the latter essential for epidermal differentiation, the Hedgehog pathway reglulator Smo, Casp8 which is required for epidermal homeostasis, and Atp2a2, mutation of which causes ER stress and the human skin disorder Darier’s disease were also negatively selected40,41,42,43,44.

Next, we analysed the VAF of the dN/dS positive genes. At all time points, Vaf_ns/Vaf_s of Trp53 mutant clones was significantly above 1 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 7). However, this was not the case for other positively selected mutants. For Notch1, Vaf_ns/Vaf_s was significantly above 1 at 8 weeks but not at later time points (Fig. 2d). For all other positively selected mutant gene clones, Vaf_ns/Vaf_s was consistent with neutrality at every time point (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 3a–e, and Supplementary Data 7).

Finally, we investigated the proportion of epidermis colonized by positively selected mutant genes. This may be estimated by summing the VAF for all protein-altering mutations in each gene at each time point. In a diploid tissue, this summed VAF is proportional to the area of epidermis occupied by mutant cells (Fig. 2f–h, Supplementary Fig. 3f–k, and Supplementary Data 8). By 16 weeks UV exposure most of the epidermis was taken over by mutations in genes under positive selection (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Of these genes, mutant Trp53 colonized epidermis more rapidly and extensively than any other positively selected gene, occupying a third of the area of the skin after 16 weeks of UV exposure (Fig. 2f). Notch1 mutants eventually colonize a quarter of the epidermis, whilst Fat1 and other mutant genes were less prevalent (Fig. 2g, h, Supplementary Fig. 3g–k, and Supplementary Data 8).

Characterization of tumor genomes

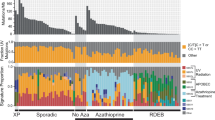

Turning to the tumors, we characterized the lesions which developed from 16 weeks of UV exposure onwards (Fig. 3a). By 27 weeks, animals had between 3 and 12 lesions each. In total, 150 tumors were dissected, with part sent for histopathological examination and the remainder frozen. Histology identified 22 premalignant actinic keratoses (AK) and 126 cSCC in the dorsal skin. cSCC were graded into three categories, I–III, based on their pathological characteristics, with I being well differentiated and III the most malignant (Methods, Supplementary Fig. 3a–c, and Supplementary Data 9). Thirteen AK and 66 cSCC were large enough for multiregional sequencing, using three or more spaced cryosections from which the tumor was micodissected. The size and location of lesions is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3c, d. Targeted DNA sequencing was performed to a median depth of 926x coverage (Supplementary Fig. 3e Methods and Supplementary Data 2).

a Number of tumors per mouse at each time point (n mice 8 weeks, 10; 16 weeks, 4; 18 weeks 2; 20 weeks, 1; 21 weeks, 4; 22 weeks, 1; 23 weeks, 2; 24 weeks, 12; 27 weeks 4). Source data: Supplementary Data 7. b Mutational burden (single-base substitutions/Mb) across tumor histological grade estimated from multiregional targeted sequencing. Each point represents the average burden across the tumor. Number of tumors: AK n = 22, SCC grade I n = 87, SCC grade II n = 36, SCC grade III n = 2, p value from Kruskal–Wallis test. c Tumor mutational burden estimated from targeted sequencing (SBS/Mb). Each point represents the average burden in tumors at that time point. 16 wk, six tumors from four mice; 18 wk, five tumors from two mice; 21 wk, one tumor from one mouse; 22 wk, five tumors from one mouse; 23 wk, six tumors from one mouse; 24 wk, 28 tumors from four mice; 27 wk, 28 tumors from four mice. Source Data: Supplementary Data 8. d CNA over time. Each point represents the average copy number change across the tumor. Red lines indicate the median at each time point. Source Data: Supplementary Data 9.

The total number of SBS, DBS, and indels detected in the 79 sequenced lesions was 49357, 1513, and 235, respectively (Supplementary Data 10). The mutational burden estimated from targeted sequencing data were similar in AK and all grades of cSCC (p = 0.55, Kruskal–Wallis test) but rose with the duration of UV exposure (Fig. 3b, c). The proportion of the genome with copy number alterations (CNA), estimated from off-target reads, also rose with the length of UV exposure (Fig. 3d, Methods, and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). CNA changes were widely distributed over chromosomes, though gains were most frequent on chromosomes 2 and 5 and losses on chromosome 1 (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Data 11).

Mutational selection in tumors

We next investigated mutant selection within tumors, beginning with dN/dS analysis. Positively selected mutant genes in tumors were the same as in the epidermis, except that Kmt2c was not selected in tumors (Figs. 2a, 4a). However, negative selection was markedly different. Only nonsynonymous mutants of Egfr and nonsense/essential splice and indel mutants of Rb1, which was not under selection in the epidermis, were under negative selection. (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Data 12).

a Genes under positive selection in tumors according to dN/dS. Mutations in all mice across all time points are pooled. q < 0.01, dNdS ratio >1.3 for nonsense/splice mutations. b Genes under negative selection in tumors according to dN/dS. Mutations in all mice across all time points are pooled q < 0.01, dNdS ratio <0.6 for nonsense/splice mutations. Source Data: Supplementary Data 12. c–e Distribution of synonymous and nonsynonymous clone size within tumors for clones mutant for Trp53 (c), Notch1 (d), and Fat1 (e). Only tumors with three slices/ tumor are used (n = 68). Each dot represents a clone. P value determined by the Wilcoxon test. Source Data: Supplementary Data 13. f–h Percentage of tumor colonized by cells mutant for Trp53 (f), Notch1 (g), and Fat1 (h), estimated from summed VAF at each time point. Data shows average across all tumors for each time point, 16 wk n = 6, 18-21 wk n = 17, 24 wk n = 28, 27 wk n = 28. Upper and lower bounds indicate uncertainty in copy number and multiplicity of mutations per cell. Source Data: Supplementary Data 14.

Vaf_ns/Vaf_s analysis showed only mutant Trp53 had Vaf_ns/Vaf_s significantly above 1 (Fig. 4c–e and Supplemental Data 13). Consistent with this, the proportion of tumor tissue mutant for mutant Trp53 rose progressively and was almost double that of other mutant genes under positive selection (Fig. 4f–h and Supplemental Data 14). Most Trp53 missense mutants resulted in codon changes within the DNA binding domain in both epidermis and tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7). A similar distribution of TP53 missense mutants is seen in human sun-exposed skin and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma5,7,23,45.

We noted there were eight tumors from eight mice where the proportion of Trp53 mutants was below that of the epidermis (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Data 15). Comparison of selection in these Trp53low tumors compared with Trp53high lesions revealed differences in the selection of other mutant genes, including stronger selection of Kras and Tgfbr1 mutants in the Trp53low group. Conversely, there were no differences in mutant gene selection comparing tumors with a proportion of Notch1 or Fat1 mutant cells above or below that in the epidermis (Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Fraction of tissue (summed VAF) with nonsynonymous mutants of Trp53. Dots are tumors (T) or epidermis (E). Tumors in pink have a lower proportion of mutant Trp53 than the epidermis in the same animal. Central bar is median, box indicates quartiles, bars indicate range. Comparison of summed VAF in epidermis and tumor p = 4.8 × 10−16, two-tailed nested ANOVA. Source Data: Supplementary Data 15. b Selection in Trp53-high and -low tumors. Summed VAF (proportion of mutant tissue) is plotted for each sequenced gene; each dot is a gene, line indicates equivalence in both groups. two-tailed Z-test with Benjamini–Hochberg multiple test correction for outliers Fat2 p = 0.002, Fat4 p = 0, Ros1 p = 0.014, Kras p = 0, Tgfbr1 p = 0.029. Source Data: Supplementary Data 15. c Heatmap of tumors with fraction of mutant Trp53 lower than the epidermis. The average summed VAF of other known tumor drivers is shown. Source Data: Supplementary Data 15. d Fraction of genome instability (fraction CNA) in relation to proportion of tumor tissue carrying Trp53 mutations (summed VAF Trp53). Tumors identified as Trp53 low (Fig. 5a) are marked as pink dots. r2 = 0.3, p < 0.0001 linear regression. Source Data: Supplementary Data 11.

Three Trp53low tumors harbored gain-of-function mutant Kras (one each of lesions with KrasG12D, KrasG12C, and KrasP34L) and two were mutant for Tgfbr1 (one with clonal nonsense and missense mutations and the other with a missense mutation). (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Fig. 8). Functional studies in mice argue gain-of-function Kras and Tgfbr1 mutations promote squamous skin tumor formation46,47,48,49. Notch2 and Kmt2c mutations, found recurrently in mouse and human skin SCC, were present in two tumors50,51,52,53. In one tumor, there were no detected mutations in the panel of sequenced genes.

Mutant Trp53-high lesions were more likely to undergo CNA than mutant Trp53-low tumors (Fig. 5d, Methods). These results suggest there may be two routes of cSCC evolution, with most lesions being Trp53-high and a minority Trp53-low, harboring alternative driver mutants, including mutant Kras and Tgfbr1.

An advantage of the SKH-1 model is that the multiplicity of tumors in each animal allows investigation of whether genome changes are more similar for lesions arising within the same host than across different mice. We focused on animals at 24 and 27 weeks, where the number of tumors per mouse is highest. There was no significant difference in the proportion of Trp53 mutant cells (Fig. 6a, b), mutational burden (Fig. 6c, d), or the proportion of copy number altered genome (Fig. 6e, f) between tumors in different animals at the same time point (two-tailed F test). The variation within each animal in each of these three parameters was similar to that between animals. Animals developed both AK and SCC, and there was no significant difference in histological tumor types between each animal (Fig. 6g, h, two-tailed F test). We conclude that tumor genomes were not influenced by host factors in SKH-1 mice.

a, b Fraction of tumor mutant for Trp53 after 24 (a p = 0.51) and 27 (b p = 0.22) weeks of UV exposure. Each column is a different mouse (animals 1–4) and each point is a tumor. The medians from each animal are also plotted. Source Data: Supplementary Data 15. c, d Tumor mutational burden after 24 (c p = 0.3) and 27 (d p = 0.5) weeks of UV exposure. Each column is a different mouse (1–4) and each point is a tumor. The medians from each animal are also plotted. Source Data: Supplementary Data 10. e, f Fraction of genome which shows CNA at 24 (e p = 0.89) and 27 (f p = 0.68) weeks of UV exposure. Each column is a different mouse (1–4) and each point is a tumor. Red lines indicate medians from each mouse. p value calculated with ANOVA. Source Data: Supplementary Data 11. g, h Histology of tumors from each mouse at 24 (g p = 1) and 27 (h p = 0.99) weeks UV exposure. p value calculated with Kruskal–Wallis. n tumors sequenced (histology)/mouse 24 weeks, mouse 1,5(6); mouse 2,6(6); mouse 3,10(11); mouse 4,7(9) tumors 27 weeks, mouse 1, 8(8); mouse 2, 7(9); mouse 3, 6(6); mouse 4, 7(7). Source Data: Supplementary Data 9.

Discussion

The mutational landscape of UV-exposed SKH-1 mouse epidermis was comparable to that in humans. By the end of the experiment, the mutational burden of normal skin had risen to a similar level as that of sun-exposed skin in humans with a history of multiple keratinocyte cancer12. The mutational spectrum in mouse epidermis was narrower than in human skin, being almost exclusively confined to UV-associated C > T and CC > TT changes. In contrast, in human epidermis, a third or more of mutations are due to cell intrinsic processes (COSMIC signatures SBS1, 5, and 40), resulting in a much broader mutational spectrum5,23. This difference is likely to reflect ageing in humans as the burden of mutations due to these “clock-like” signatures increases in proportion with time54.

dN/dS analysis showed the mutant genes under positive selection in UV-treated mouse epidermis overlapped with those positively selected in human sun-exposed skin (Fig. 7)5,7,23. Trp53 was the fittest positively selected mutant in mouse epidermis, evidenced by VAF_ns/VAF_s values significantly above 1 throughout the experiment. In contrast, for the other positively selected mutant genes VAF_ns/VAF_s was significantly above neutrality only for Notch1 at the 8-week time point. How might the discrepancy between a positive a dN/dS ratio and the neutral VAF_ns/VAF_s be explained? Lineage tracing studies in squamous epithelia in transgenic mice show that mutants such as Trp53 and Notch1 expand rapidly for a short period while mutants are competing with less fit wild-type cells17,55,56,57. However, once mutant cells are surrounded by cells of similar fitness, their phenotype and competitive fitness revert towards wild type. It is this phenotypic reversion that enables tissues like the epidermis to carry a high proportion of mutant cells and yet continue to function normally. The positive selection detected by dN/dS may reflect the brief period of clonal expansion in a wild-type background whereas neutral VAF_ns/VAF_s result from a much longer period of neutral dynamics following phenotypic reversion. As the tissue approaches saturation with positively selected mutants at 16 weeks, only Trp53 mutants have a robustly positive VAF_ns/VAF_s. Human TP53 mutants are more strongly selected than other mutants in human facial skin which is saturated with mutant clones, arguing they have a higher fitness than other positively selected mutants23. By contrast, in facial skin which is sparsely mutated and has a lower burden of UV-induced mutations, NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 mutants are preferentially selected, and TP53 mutants are comparatively rare23. The high fitness of mutant Trp53 may result from continuing UV light exposure, which drives the exponential expansion of p53 mutant clones in mouse and human skin57,58,59.

Negatively selected genes with dN/dS for nonsense mutations <0.7 and q < 0.01, blue, and positively selected mutants dN/dS for nonsense mutations >1.3 and q < 0.01, red, are shown. Genes in yellow are also selected in the human sun-exposed epidermis and AK/cSCC. Source Data: Supplementary Data 6, 12.

Four mutant genes, Fat2, Ajuba, Ros1 and Kmt2c were positively selected in mice but have not been shown to be selected in human epidermis. Of these genes, Ros1-deleted cells have been reported to drive clonal expansion in a CRISPR/Cas9 screen in normal mouse epidermis. Kmt2c was identified as a tumor suppressor in a mouse transposon screen for genes regulating squamous carcinogenesis, and the related histone lysine methyltransferase, KMT2D, is selected in human epidermis36,60. AJUBA, which regulates keratinocyte cytoskeletal signaling via RAC, is positively selected in other human squamous epithelia21,35,61. Of the ten negatively selected mutants in mouse, only inactivating PIK3CA mutants have been shown to be negatively selected in human skin5. This may reflect the smaller number of mutations detected in human studies, as sufficient synonymous mutations are required to identify negatively selected genes.

Turning to carcinogenesis, the data were consistent with two convergent evolutionary routes to develop cSCC, both of which may be followed in the same animal. In both SKH-1 mice and humans, the majority of UV-induced tumors are p53 mutant8,22,24,49,50,62,63,64,65,66. However, p53 wild-type tumors that harbor other drivers, including oncogenic mutant Kras and Tfbr1, were also seen, paralleling TP53 wild-type human tumors8,22,49,66,67. Copy number alterations were more likely to occur in TP53 mutant than wild-type tumors, a finding also seen in human cSCC22.

The dN/dS positive mutant genes were similar in the epidermis and tumors (Figs. 2a, 4a). This is also the case for the commonest positively selected mutant genes in sun-exposed human skin, NOTCH1, NOTCH2, TP53, and FAT1, which are also frequently mutated in AK and cSCC5,7,22,31,68. However, this need not mean that the positively selected mutants are driving tumor initiation and growth17,69. Mutations that are selected in the epidermis are likely to be found in a subset of tumors, even if they do not contribute to transformation5,7. In tumors, Vaf_ns/VAf_s is positive for Trp53, suggesting protein-altering Trp53 mutations may drive tumor growth (Fig. 4f). However, this is not the case for other positively selected mutants for which Vaf_ns/VAf_s is neutral (Supplemental Data 13). Mutant genes in tumors that do not drive tumor growth may contribute to orthogonal malignant phenotypes such as invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis30,51,70.

There are no comparable human studies in which mutations in cSCC and AK have been directly compared with adjacent skin. Mutants that drive clonal expansions in normal tissues or premalignant lesions may be neutral or even inhibitory in malignant transformation5,17,35,69,71. In humans, the proportion of TP53 mutant tumors is increased compared with the fraction of TP53 mutant sun-exposed skin5. Conversely, the proportion of NOTCH1 and FAT1 mutant human tumors is similar to the proportion of normal skin mutants for these genes5. Collectivel,y these observations suggest NOTCH1 and FAT1 may not make a substantial contribution to the transformation and growth of cSCC.

Negative selection was markedly different between normal tissue and tumors. In the epidermis, most of the negatively selected mutants are known to impact keratinocyte proliferation or differentiation. In tumors, negative selection was attenuated, and only two negatively selected mutant genes were found. The reasons for this may be that mutants with a negative fitness impact hitchhike along with positively selected mutations, so the net fitness of the clone remains positive. Such ‘genomic hitchhiking’ is most likely to occur in lesions with a high mutational burden, such as those in this study20. In addition, the degree of spatial competition between clones in an expanding lesion is reduced compared with the “zero sum game” of the epidermis, and environmental differences between tumor and epidermis may contribute to altered selection32,57. Mutant Egfr was negatively selected in both epidermis and tumors, consistent with the impairment of mouse skin tumor growth following the transgenic deletion of Efgr and EGFR inhibitor studies in human skin SCC72,73 (Fig. 7). The negative selection of Egfr in normal epidermis reveals a dependency that correlates with the skin toxicity of EGFR inhibitors in humans74,75. The negative selection of nonsense and essential splice Rb1 mutants in tumors seems at odds with the tumor suppressor role of RB1 in a range of human cancers76. However, this finding is consistent with the results of conditional Rb1 deletion in the epidermis of adult Rb1flox/flox mice77. In a chemical carcinogenesis protocol, Rb1 loss resulted in fewer and smaller tumors compared with wild-type controls77. The reduced size of the Rb1-/- tumors is due to increased apoptosis in tumor cells, consistent with negative selection of Rb1 in mouse skin tumors77.

Limitations of the study follow from the targeted sequencing approach used. There may be additional positively selected mutants in genes not in the sequenced panel, and universal essential and other genes under negative selection were not included. Furthermore, the resolution of the approach used to identify CNA is low, and changes smaller than a chromosome arm amplification or deletion may not be detected. The estimate of the proportion of the genome with CNA should be viewed as a lower bound. Sample size is also an issue, with only 8 Trp53 low lesions. The data were consistent with there being two routes of tumor evolution, Trp53high and Trp53low, but a larger sample of lesions would be required to confirm this statistically.

We conclude that the genomic evolution of UV-exposed normal skin and the tumors that arise from it is convergent in mice and humans. Both positive and negative selection varies between normal tissue and tumors. Alterations in negative selection between tumors and normal tissue may be a general feature of carcinogenesis. Mutant genes negatively selected in both normal tissue and tumors suggest toxicity may occur in the normal epidermis if the gene targeted therapeutically. Conversely, mutant genes under negative selection only in tumors may be optimal candidates for antitumor therapy78. Model systems such as that employed here offer a route to resolving the dynamics of selection in carcinogenesis. Finally, this work demonstrates the utility of sequencing normal tissue alongside tumors in the same individuals.

Methods

Husbandry

A total of 52 SKH-1-hr hairless immunocompetent mice (Crl:SKH-1-Hrhr, Charles River Laboratories) were housed in a standard colony (4–5 animals per cage), in a temperature- and light-controlled environment (12/12-h light/dark cycle) and maintained with water and food ad libitum.

UVB-irradiation

Mice were UV irradiated on their backs three times per week with 70 mJ/cm2 of UVB using a GL40E 40 W tube (SNEE), which emits most of its energy within the UVB range (90%; emission spectrum 280–370; 10% UVA)79. Doses of UVB (312 nm) were monitored using an appropriate radiometer. Non-irradiated (sham-manipulated) aged-matched mice were used as controls. Each mouse was an independent experimental unit. Sample size was estimated from previous reports24,25. Numbers of animals and tumors per time point are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

The time of tumor appearance, tumor number and size were monitored three times per week. Euthanasia (using CO2 gas in accordance with the requirements of the Veterinary Office of the Canton Vaud (Switzerland) and Federal Swiss Veterinary Office Guidelines). The Veterinary Office of the Canton Vaud permitted a maximum tumor size of 0.5 cm3 and this limit was not exceeded in any experiments. The maximum permitted weight loss was 10% of the initial weight, and this limit was not exceeded in any experiments. Tumors, non-tumoural dorsal skin and ventral skin samples were collected.

Tumor grading

Tumors were graded as previously described79. Mouse skin tumors were paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Histological analysis of actinic keratosis and tumor classification were performed in a blind manner by a dermatopathologist.

SCCs were classified according to the Broders’ classification based on the degree of SCC keratinization and of keratinocyte differentiation80. This classification is as follows: SCC Grade I: 75% keratinocytes are well differentiated; SCC Grade II: >50% keratinocytes are well differentiated; SCC Grade III: >25% keratinocytes are well differentiated, and SCC Grade 4: <25% keratinocytes are well differentiated. Actinic keratoses were defined histologically and classified as grade I, II, or III based on the degree of cytological atypia of epidermal keratinocytes and involvement of adnexal structures according to ref. 81.

Wholemount sample preparation

The whole back skin was cut into rectangular pieces of ~4 by 5 mm and incubated in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA at 37 °C for 2 h. The skin samples were transferred into PBS, and the epidermis was carefully scraped off using a curved scalpel by holding one corner of the sample with forceps. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min.

Epidermal samples were immunolabelled with p53 antibody (CM5, Vector Laboratories VP-P956) to highlight morphologically abnormal areas prior to dissection into 1–2mm2 grids. Samples were blocked in staining buffer (0.5% Bovine Serum Albumin, 0.25% Fish Skin Gelatin, and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) with 10% donkey serum for 1 h at room temperature. Wholemount samples were then incubated with p53 antibody (1:500) in staining buffer overnight, washed three times in PBS/0.2% Tween-20, incubated with fluorchrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, A31572) for 2 h at room temperature and washed as before.

Epidermal wholemounts were dissected into 1–2 mm2 grids and DNA extracted using QIAMP DNA microkit (Qiagen) by digesting overnight and following manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted using prewarmed AE buffer, where the first eluent was passed through the column two further times. Flash-frozen liver DNA was used as the germline control, and DNA was extracted as for the epidermal samples.

Tumors

The time of tumor appearance, tumor number and size were monitored three times per week. Euthanasia (using CO2 gas in accordance with the requirements of the Veterinary Office of the Canton Vaud (Switzerland) and Federal Swiss Veterinary Office Guidelines) took place when the largest tumor volume reached 0.5 cm3 or in the case of 10% weight loss compared to the initial weight. These limits were not exceeded in any experiments. Tumors, non-tumoural dorsal skin and ventral skin samples were collected.

Tumor grading

Tumors were graded as previously described79. Mouse skin tumors were paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Histological analysis of actinic keratosis and tumor classification were performed in a blind manner by a dermatopathologist.

SCCs were classified according to the Broders’ classification based on the degree of SCC keratinization and of keratinocyte differentiation80. This classification is as follows: SCC Grade I: 75% keratinocytes are well differentiated; SCC Grade II: >50% keratinocytes are well differentiated; SCC Grade III: >25% keratinocytes are well differentiated, and SCC Grade 4: <25% keratinocytes are well differentiated. Actinic keratoses were defined histologically and classified as grade I, II or III based on the degree of cytological atypia of epidermal keratinocytes and involvement of adnexal structures according to ref. 81.

Wholemount sample preparation

The whole back skin was cut into rectangular pieces of ~4 by 5 mm and incubated in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA at 37 °C for 2 h. The skin samples were transferred into PBS, and the epidermis was carefully scraped off using a curved scalpel by holding one corner of the sample with forceps. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min.

Epidermal samples were immunolabelled with p53 antibody (CM5, Vector Laboratories VP-P956) to highlight morphologically abnormal areas prior to dissection into 1–-2 mm2 grids. Samples were blocked in staining buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.25% fish skin gelatin, and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) with 10% donkey serum for 1 h at room temperature. Wholemount samples were then incubated with p53 antibody (1:500) in staining buffer overnight, washed three times in PBS/0.2% Tween-20, incubated with fluorchrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, A31572) for 2 h at room temperature and washed as before.

Epidermal wholemounts were dissected into 1–2 mm2 grids and DNA extracted using QIAMP DNA microkit (Qiagen) by digesting overnight and following manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted using prewarmed AE buffer, where the first eluent was passed through the column two further times. Flash-frozen liver DNA was used as the germline control, and DNA was extracted as for the epidermal samples.

Tumor sample preparation

Tumors were frozen in OCT and perpendicularly sectioned in a sequential manner. A thickness of 50 µm sections for sequencing were used. Tumors were stained, and tumor epithelia were collected for sequencing on the same day. Tumor sections were incubated in staining buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.25% fish skin gelatin, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% saponin, and 1 mM EDTA in PBS) supplemented with 10% donkey serum for 15 min. Keratin 14 (Covance PRB-155P) antibody (used to label epithelia) was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 using an antibody labeling kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific A20181). Sections were incubated with directly conjugated Keratin 14 antibody for 20 min in staining buffer, followed by two washes in 0.1% saponin PBS for 10 min. Positively stained Keratin 14 areas were dissected under fluorescent Leica M165 FC microscope and used for DNA extraction. Stroma was discarded. DNA was extracted as described above.

Targeted sequencing

DNA was sequenced at high depth using a custom bait panel (Agilent SureSelect) covering murine homologs of 74 genes implicated in human cancers, as described previously82. A list of genes covered by the bait set can be found in Supplementary Data 2.

About 200 ng of genomic DNA was fragmented (average size distribution ~150 bp, LE220, Covaris Inc), purified, libraries prepared (NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library prep Kit, New England Biolabs), and index tags applied (https://emea.illumina.com/products/by-type/accessory-products/idt-pcr-index-sets.html). Index-tagged samples were amplified (six cycles of PCR, KAPA HiFi kit, KAPA Biosystems), quantified (Accuclear dsDNA Quantitation Solution, Biotium), and then pooled together in an equimolar fashion. About 500 ng of pooled material was taken forward for hybridization, capture and enrichment (SureSelect Target enrichment system, Agilent technologies), normalized to ~6 nM), and submitted to cluster formation for sequencing on HiSeq2500 (Illumina) to generate 75 bp paired-end reads.

BAM files were mapped to the GRCh37d5 reference genome using BWA-mem (version 0.7.17)83. Duplicate reads were marked using SAMtools (v1.11)68). Depth of coverage was also calculated using SAMTools to exclude reads which were: unmapped, not in the primary alignment, failing platform/vendor quality checks or were PCR/Optical duplicates. BEDTools (version 2.23.0) coverage program was then used to calculate the depth of coverage per base across samples84 (Supplementary Figs. 1c, d—epidermis, 4e— tumor).

Nanoseq

About 50 ng of DNA was used for DupSeq library preparation according to ref. 34. Briefly, DNA was digested with mung bean nuclease, A-tailed, repaired and tagged. 0.3 fmol of indexed tagged library were sequenced with 14 PCR cycles before quantifying and sequencing on Novaseq6000 (Illumina) with 150 bp PE reads to give a median 0.6x duplex coverage. About 3 fmol of indexed tagged libraries generated from DNA extracted from the liver of the same mouse was used as the germline control for calling of SNPs and indels. For both SNV and indels, only calls which passed all the defined filters were used https://github.com/cancerit/NanoSeq.

Mutation calling

For targeted sequencing data, sub-clonal mutation variant calling was made using the deepSNV R package (also commonly referred to as ShearwaterML), version 1.21.3, available at https://github.com/gerstung-lab/deepSNV, used in conjunction with R version 3.3.0 (2016-05-03)35. Variants were annotated using VAGrENT85.

Mutations called by ShearwaterML were filtered using the following criteria

-

Positions of called SNVs must have a coverage of at least 100 reads

-

Germline variants called from the same individual were removed from the list of called variants.

-

Adjustment for FDR and mutations demanded support from at least one read from both strands for the mutations identified.

-

Pairs of SNVs on adjacent nucleotides within the same sample are merged into a dinucleotide variant if at least 90% of the mapped DNA reads containing at least one of the SNV pair, contained both SNVs.

-

Identical mutations found in multiple contiguous tissue biopsies are merged and considered as a single clone in order to prevent duplicate clone counting.

ShearwaterML was run with a normal panel of approximately 16k (tumor) or 31k (epidermis) reads.

Calculations of the percentage mutant epithelia

The percentage of mutant tissue was estimated from the variant allele frequency, allowing for the uncertainty over copy number and nesting of mutants. dN/dS analysis was performed using https://github.com/im3sanger/dndscv35.

Copy number analysis

The copy number analysis was performed with the pipeline defined in Abby et al.17, which was slightly modified in the following ways: (1) The segmentation gamma parameter was increased from 10 to 30. This parameter controls the likelihood that the segmentation starts a new segment. (2) Instead of the mean logR (log ratio, sample coverage normalized with coverage of the matched normal and corrected for GC content) per segment, the median logR was used as a summary statistic. This decreases the sensitivity of the gain/loss calling step to outlier data. We found these two changes reduce spurious segments, resulting in low confidence calls on these data. A bin size of 100 Kb was used with QDNAseq.

A parameter sweep was performed to investigate how segmentation behavior changes with different penalty (Segmentation γ) and minimum-size (k-min) settings. We compared five runs with different parameters (γ = 10, default γ = 30, k_min = 2, γ = 50, and γ = 100) and computed consistent run-level metrics: the number of segments per sample, segment-length distributions (absolute and normalized), and copy number class composition by summed segment length. These metrics permit direct comparison of segmentation granularity, the relative contribution of different length classes to total segmented bases, and whether copy-number balance (gain/loss/normal proportions) is preserved across parameter choices.

The vast majority of segments are concentrated in very large segments ( > 50 Mb) for all runs (default γ = 30 → ~89.9%; γ = 10 → ~81.6%; γ = 100 → ~95.3%), indicating that we are conservatively calling chromosome-scale events that dominate the total segmented length (Supplementary Fig. 6a). This trend is as expected. Increasing γ leads to a higher segmentation penalty and fewer segments (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Similarly, decreasing the gamma leads to more segments, specifically, substantially more short segments (<1 Mb: 304 vs default = 169). However, copy-number class composition by summed length is highly stable across runs (for the default run, gain = 5.36%, loss = 5.66%, normal = 88.98%), with only small shifts for other γ values. (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

The parameter sweep serves as an explicit robustness check, which indicates that chromosome-level CNA patterns are robust to reasonable segmentation-parameter choices for the sequencing data.

The code of this pipeline is available86.

Clonality analysis

A tumor was assigned the label monoclonal or multifocal. A tumor was assigned as monoclonal when it fit one of the following categories (in order of priority): (1) At least five SNVs and at least one CNA >10 Mb were present in all samples, (2) at least 20 SNVs were present in all samples, (3) at least five SNVs present in all samples excluding samples without detected SNVs or CNAs from the edge of the tumor (in this scenario a sample was taken from just beyond the tumor boundary and therefore was completely normal), and (4) at least five SNVs were present in all samples and the CNA profile did not contain any alterations >10 Mb.

A tumor was assigned as multifocal when it fit one of the following categories (in order of priority): (1) samples did not share any clonal SNVs nor CNAs, at least two samples had separate sets of at least five SNVs and separate CNAs >10 Mb, (2) at least two samples had separate sets of at least five SNVs and the CNA profiles did not contain any alterations >10 Mb.

The remaining tumors were manually inspected and consistently yielded separate clonal expansions consistent with a multifocal label supported by SNVs, but with few conflicting CNAs. There is emerging evidence of parallel evolution of CNAs during a tumor’s lifetime87. The remaining set of tumors were therefore assigned to be multifocal due to the support from SNVs.

Statistics and reproducibility

Animals were randomly assigned to treatments and time points. Numbers of mice at each time point are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Investigators were not blinded to experimental time points. Statistical tests, as described in figure legends, were two-tailed unless noted.

Animal ethics

All experiments involving animals were approved by the Veterinary Office of the Canton Vaud, Switzerland (VD1528.5) in accordance with the Federal Swiss Veterinary Office Guidelines and conform to the Commission Directive 2010/63/EU. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Data availability

The sequencing datasets generated during the study are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home) with the following dataset accession numbers: ERP166413 (epidermal sequencing dorsal and ventral). ERP166414 (tumor sequencing). ERP141605 (nanoseq of dorsal epidermis). Numerical source data is provided as Supplementary Data 2–15.

Code availability

The code used for copy number analysis is available on https://github.com/PHJonesGroup/Skrupskelyte_etal_SI_code and has been deposited on Zenodo, https://zenodo.org/records/1773445686.

References

Gerstung, M. et al. The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature 578, 122–128 (2020).

Martincorena, I. et al. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell 171, 1029–1041.e1021 (2017).

Martínez-Jiménez, F. et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 555–572 (2020).

Wei, L. et al. Ultradeep sequencing differentiates patterns of skin clonal mutations associated with sun-exposure status and skin cancer burden. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd7703 (2021).

Fowler, J. C. et al. Selection of oncogenic mutant clones in normal human skin varies with body site. Cancer Discov. 11, 340–361 (2021).

Lynch, M. D. et al. Spatial constraints govern competition of mutant clones in human epidermis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1119 (2017).

Martincorena, I. et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 348, 880–886 (2015).

South, A. P. et al. NOTCH1 mutations occur early during cutaneous squamous cell carcinogenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 2630–2638 (2014).

Hernando, B. et al. The effect of age on the acquisition and selection of cancer driver mutations in sun-exposed normal skin. Ann. Oncol. 32, 412–421 (2021).

Kaur, K. et al. Skin cancer risk is increased by somatic mutations detected noninvasively in healthy-appearing sun-exposed skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 144, 2187–2196.e2113 (2024).

Kim, Y.-S., Bang, C. H. & Chung, Y.-J. Mutational landscape of normal human skin: clues to understanding early-stage carcinogenesis in keratinocyte neoplasia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 143, 1187–1196.e1189 (2023).

Wong, H. Y. et al. Epidermal mutation accumulation in photodamaged skin is associated with skin cancer burden and can be targeted through ablative therapy. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf2384 (2023).

Yizhak, K. et al. RNA sequence analysis reveals macroscopic somatic clonal expansion across normal tissues. Science 364, eaaw0726 (2019).

Fowler J. C., Jones P. H. Somatic mutation: what shapes the mutational landscape of normal epithelia? Cancer Discov. 12, 1642–1655 (2022).

Colom, B. et al. Spatial competition shapes the dynamic mutational landscape of normal esophageal epithelium. Nat. Genet. 52, 604–614 (2020).

Colom, B. et al. Mutant clones in normal epithelium outcompete and eliminate emerging tumours. Nature 598, 510–514 (2021).

Abby, E. et al. Notch1 mutations drive clonal expansion in normal esophageal epithelium but impair tumor growth. Nat. Genet. 55, 232–245 (2023).

Besedina, E. & Supek, F. Copy number losses of oncogenes and gains of tumor suppressor genes generate common driver mutations. Nat. Commun. 15, 6139 (2024).

Weghorn, D. & Sunyaev, S. Bayesian inference of negative and positive selection in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 49, 1785–1788 (2017).

Tilk, S., Tkachenko, S., Curtis, C., Petrov, D. A. & McFarland, C. D. Most cancers carry a substantial deleterious load due to Hill-Robertson interference. eLife 11, e67790 (2022).

Lawson, A. R. J. et al. Somatic mutation and selection at population scale. Nature 647, 411–420 (2025).

Inman, G. J. et al. The genomic landscape of cutaneous SCC reveals drivers and a novel azathioprine associated mutational signature. Nat. Commun. 9, 3667 (2018).

King, C. et al. Somatic mutations in facial skin from countries of contrasting skin cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 55, 1440–1447 (2023).

Knatko, E. V. et al. Whole-exome sequencing validates a preclinical mouse model for the prevention and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev. Res. 10, 67–75 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. Loss of hairless confers susceptibility to UVB-induced tumorigenesis via disruption of NF-kappaB signaling. PLoS ONE 7, e39691–e39691 (2012).

Schaffer, B. S. et al. Immune competency of a hairless mouse strain for improved preclinical studies in genetically engineered mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 2354–2364 (2010).

Benavides, F., Oberyszyn, T. M., VanBuskirk, A. M., Reeve, V. E. & Kusewitt, D. F. The hairless mouse in skin research. J. Dermatol. Sci. 53, 10–18 (2009).

Voigt, A. Y., Michaud, M., Tsai, K. Y., Oh, J. & Sundberg, J. P. Differential hairless mouse strain-specific susceptibility to skin cancer and sunburn. J. Invest. Dermatol. 139, 1837–1840.e1833 (2019).

Blohm-Mangone, K. et al. Pharmacological TLR4 antagonism using topical resatorvid blocks solar UV-induced skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 11, 265–278 (2018).

Bailey, P. et al. Driver gene combinations dictate cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma disease continuum progression. Nat. Commun. 14, 5211 (2023).

Thomson, J. et al. The genomic landscape of actinic keratosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 141, 1664–1674.e1667 (2021).

Chitsazzadeh, V. et al. Cross-species identification of genomic drivers of squamous cell carcinoma development across preneoplastic intermediates. Nat. Commun. 7, 12601 (2016).

Gerstung, M., Papaemmanuil, E. & Campbell, P. J. Subclonal variant calling with multiple samples and prior knowledge. Bioinformatics 30, 1198–1204 (2014).

Abascal, F. et al. Somatic mutation landscapes at single-molecule resolution. Nature 593, 405–410 (2021).

Martincorena, I. et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science 362, 911–917 (2018).

Aiderus, A. et al. Transposon mutagenesis identifies cooperating genetic drivers during keratinocyte transformation and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma progression. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009094 (2021).

Franzke, C. W. et al. Epidermal ADAM17 maintains the skin barrier by regulating EGFR ligand-dependent terminal keratinocyte differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1105–1119 (2012).

Dahlhoff, M., Muzumdar, S., Schafer, M. & Schneider, M. R. ERBB2 is essential for the growth of chemically induced skin tumors in mice. J. Invest. Dermatol. 137, 921–930 (2017).

Dahlhoff, M., Schafer, M., Muzumdar, S., Rose, C. & Schneider, M. R. ERBB3 is required for tumor promotion in a mouse model of skin carcinogenesis. Mol. Oncol. 9, 1825–1833 (2015).

Indra, A. K. et al. Temporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis in embryonic surface ectoderm and fetal epidermal keratinocytes unveils two distinct developmental functions of BRG1 in limb morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Development 132, 4533–4544 (2005).

Mardaryev, A. N. et al. p63 and Brg1 control developmentally regulated higher-order chromatin remodelling at the epidermal differentiation complex locus in epidermal progenitor cells. Development 141, 101–111 (2014).

Savignac, M., Edir, A., Simon, M. & Hovnanian, A. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1111–1117 (2011).

Grachtchouk, V. et al. The magnitude of hedgehog signaling activity defines skin tumor phenotype. EMBO J. 22, 2741–2751 (2003).

Kovalenko, A. et al. Caspase-8 deficiency in epidermal keratinocytes triggers an inflammatory skin disease. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2161–2177 (2009).

Piipponen, M., Riihilä, P., Nissinen, L. & Kähäri, V.-M. The role of p53 in progression of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 13, 4507 (2021).

van der Weyden, L. et al. Acute sensitivity of the oral mucosa to oncogenic K-ras. J. Pathol. 224, 22–32 (2011).

Lapouge, G. et al. Identifying the cellular origin of squamous skin tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7431–7436 (2011).

Bian, Y. et al. Progressive tumor formation in mice with conditional deletion of TGF-β signaling in head and neck epithelia is associated with activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Cancer Res. 69, 5918–5926 (2009).

Cammareri, P. et al. Inactivation of TGFβ receptors in stem cells drives cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 7, 12493 (2016).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Genomic analysis of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 1447–1456 (2015).

Pickering, C. R. et al. Mutational landscape of aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 6582–6592 (2014).

Wang, N. J. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in Notch receptors in cutaneous and lung squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17761–17766 (2011).

Yoshioka, A. et al. The landscape of genetic alterations of UVB-induced skin tumors in DNA repair-deficient mice. Exp. Dermatol. 31, 1607–1617 (2022).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578, 94–101 (2020).

Murai, K. et al. p53 mutation in normal esophagus promotes multiple stages of carcinogenesis but is constrained by clonal competition. Nat. Commun. 13, 6206 (2022).

Piedrafita, G. et al. A single-progenitor model as the unifying paradigm of epidermal and esophageal epithelial maintenance in mice. Nat. Commun. 11, 1429 (2020).

Murai, K. et al. Epidermal tissue adapts to restrain progenitors carrying clonal p53 mutations. Cell Stem Cell 23, 687–699.e688 (2018).

Klein, A. M., Brash, D. E., Jones, P. H. & Simons, B. D. Stochastic fate of p53-mutant epidermal progenitor cells is tilted toward proliferation by UV B during preneoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 270–275 (2010).

Zhang, W., Remenyik, E., Zelterman, D., Brash, D. E. & Wikonkal, N. M. Escaping the stem cell compartment: sustained UVB exposure allows p53-mutant keratinocytes to colonize adjacent epidermal proliferating units without incurring additional mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13948–13953 (2001).

Renz, P. F. et al. In vivo single-cell CRISPR uncovers distinct TNF programmes in tumour evolution. Nature 632, 419–428 (2024).

Nola, S. et al. Ajuba is required for Rac activation and maintenance of E-cadherin adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 195, 855–871 (2011).

Al-Rohil, R. N. et al. Evaluation of 122 advanced-stage cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas by comprehensive genomic profiling opens the door for new routes to targeted therapies. Cancer 122, 249–257 (2016).

Kranen, H. J. V. et al. Frequent p53 alterations but low incidence of ras mutations in UV-B-induced skin tumors of hairless mice. Carcinogenesis 16, 1141–1147 (1995).

Khan, S. G. et al. Mutations in ras oncogenes: rare events in ultraviolet B radiation-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 15, 96–103 (1996).

Wang, Y. et al. p53 gene mutations in SKH-1 mouse tumors differentially induced by UVB and combined subcarcinogenic benzo[a]pyrene and UVA. Photochem. Photobio. 84, 444–449 (2008).

Chang, D. & Shain, A. H. The landscape of driver mutations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. NPJ Genom. Med. 6, 61 (2021).

Su, F. et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 207–215 (2012).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10, giab008 (2021).

Herms, A. & Jones, P. H. Somatic mutations in normal tissues: new perspectives on early carcinogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 7, 189–205 (2023).

Pastushenko, I. et al. Fat1 deletion promotes hybrid EMT state, tumour stemness and metastasis. Nature 589, 448–455 (2021).

Beckman, R. A. Efficiency of carcinogenesis: is the mutator phenotype inevitable? Semin. Cancer Biol. 20, 340–352 (2010).

Pham, J. P., Rodrigues, A., Goldinger, S. M., Sim, H. W. & Liu, J. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Dermatol. 33, e14978 (2024).

Sibilia, M. et al. The EGF receptor provides an essential survival signal for SOS-dependent skin tumor development. Cell 102, 211–220 (2000).

Holcmann, M. & Sibilia, M. Mechanisms underlying skin disorders induced by EGFR inhibitors. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2, e1004969 (2015).

Friedman, N. et al. Preventing skin toxicities induced by EGFR inhibitors by topically blocking drug-receptor interactions. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabo0684 (2023).

Knudsen, E. S., Pruitt, S. C., Hershberger, P. A., Witkiewicz, A. K. & Goodrich, D. W. Cell cycle and beyond: exploiting new RB1 controlled mechanisms for cancer therapy. Trends Cancer 5, 308–324 (2019).

Ruiz, S. et al. Unexpected roles for pRb in mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 65, 9678–9686 (2005).

Bányai, L., Trexler, M., Kerekes, K., Csuka, O. & Patthy, L. Use of signals of positive and negative selection to distinguish cancer genes and passenger genes. Elife 10, e59629 (2021).

Montagner, A. et al. Src is activated by the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ in ultraviolet radiation-induced skin cancer. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 80–98 (2014).

Broders, A. C. Squamous cell epithelioma of the skin: a study of 256 cases. Ann. Surg. 73, 141–160 (1921).

Röwert-Huber, J. et al. Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br. J. Dermatol. 156, 8–12 (2007).

King, C. et al. Somatic mutant selection is altered by prior NOTCH1 mutation in aging esophageal epithelium. Preprint at bioRxiv 2024.2009.2026.615123 (2024).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at arXiv:1303.3997 (2013).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Menzies, A. et al. VAGrENT: variation annotation generator. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 52, 15.18.11–15.18.11 (2015).

Sood, R. & Jones, P. H. Skrupskelyte etal SI code: publication supporting code and notebooks. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17734456 (2025).

Watkins, T. B. K. et al. Pervasive chromosomal instability and karyotype order in tumour evolution. Nature 587, 126–132 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Maude Delacombaz for expert assistance with Histology and Lisa Cherbuin, Marie Sgandurra, Lionel Mury, Hélène Garcia, and Dr Christine Pich for assistance with UV exposure and sample harvesting. This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust to the Wellcome Sanger Institute (098051, 296194, and 220540/Z/20/A) and Cancer Research UK Program Grants to P.H.J. (C609/A17257 and C609/A27326). B.H. is supported by a Royal Society URF grant (UF130039). L.M. is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-169232), SKINTEGRITY.CH collaborative research and the Etat de Vaud, University of Lausanne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S., C.W., J.K., and E.G. performed experiments. J.C.F., S.D., N.B., R.S., J.F., T.Q., and C.K. analysed data. I.A. performed statistical analysis supervised by B.H. J.C.F. and P.H.J. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors. L.M. and P.H.J. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Robert A. Beckman, Radhakrishnan Sabarinathan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Murali Dharan Bashyam and Johannes Stortz. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skrupskelyte, G., Fowler, J.C., Dentro, S. et al. The dynamics of mutational selection in cutaneous squamous carcinogenesis. Commun Biol 9, 127 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09406-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09406-9