Abstract

Multi-functional cysteine-targeting covalent warheads possess significant therapeutic potential in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. Herein, we present novel unsaturated and asymmetric ketone (oxazolinosene) scaffolds that selectively conjugate cysteine residues of peptides and bovine serum albumin under normal physiological conditions. This unsaturated saccharide depletes GSH in NCI-H1299 cells, leading to anti-tumor effects in vitro. The acetyl group of the ketal moiety on the saccharide ring can be converted to other carboxylic acids in a one-pot synthesis. In this way, the loaded acid can be click-released during cysteine conjugation, making the oxazolinosene a potential multifunctional therapeutic agent. The reaction kinetic model for oxazolinosene conjugation to GSH is well established and was used to evaluate oxazolinosene reactivity. The aforementioned oxazolinosenes were stereoselectively synthesized via a one-step reaction of nitriles with saccharides and conveniently converted into a series of α, β-unsaturated ketone N-glycosides as prevalent synthetic building blocks. The reaction mechanisms of oxazolinosene synthesis were investigated through calculations and validated with control experiments. Overall, these oxazolinosenes can be easily synthesized and developed as cysteine-targeted covalent warheads carrying useful click-releasing groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

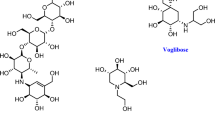

Saccharides are an important class of natural products involved in many biochemical activities, such as providing nutrition1, development of cell structures2,3, and transmitting signals within cells4,5,6. Chemically, saccharides have a hemiacetal group at the C1 position, coupled with multiple chiral hydroxyl groups7. They are capable of undergoing a wide range of reactions, including the synthesis of glycosides8, deoxy-sugars9, glycoconjugates10, and other complex natural products11,12. Moreover, the modification of saccharides has yielded a variety of useful molecules for various medicinal applications. A typical example is the use of metabolic oligosaccharide engineering probes, which utilize glycosyltransferases to incorporate modified saccharides, such as sialic acid or N-acetylglucosamine, onto oligosaccharide chains on the cell surface13,14,15. This allows the generation of alkynyl16 or azide17-labeled glycans in cells to undergo a biorthogonal click reaction with fluorescent or other kinds of small molecule chemical probes. This process has been widely used in proteomics, imaging, extracellular matrix transformation, cancer targeting, etc.18.

Covalent inhibitors can bind to target proteins either reversibly or irreversibly by forming covalent bonds. Compared with non-covalent small molecule inhibitors, covalent inhibitors create a stronger interaction with target proteins. As a result, covalent inhibitors are more efficient, require lower dosages, less likely to cause drug resistance, and can easily target “undruggable” proteins19,20. The rational development of electrophilic moieties, also known as warheads, is of utmost importance21,22. Due to the highly conserved structure and strong nucleophilicity23,24, cysteine is currently one of the most commonly targeted residues by covalent drugs21. However, the number of commercially available cysteine-targeting covalent drugs is still very limited. This shortage could be partly attributed to the lack of ideal molecular warheads. Since the introduction of N-acrylamide into rational covalent drug design25, medicinal chemists have identified many other reliable chemical structures, including thiocyanates26, alkynyl groups27, trifluoromethyl ketones28, heteroaromatics28 and even some warheads containing functional leaving groups29,30, that can react with cysteine residues.

Unsaturated saccharides have been reported to exhibit various biological activities, including anti-tumor31,32, anti-inflammatory33, and antibiotic34 properties. Among these, α-β-unsaturated ketones are readily available and can undergo thiol-ene addition to cysteine32,33,34,35. A desirable warhead should possess appropriate reactivity, the correct configuration, and a suitable size to match the binding pocket of the target protein36. For example, Tauton has been reported as a rational chiral covalent inhibitor of aryl-sulfonyl fluoride, developed through a ligand-first strategy, where only the S-enantiomer showed inhibitory activity against Hsp90 protein, while the R-enantiomer was ineffective due to its configuration. Additionally, a chemical proteomic study involving a series of enantiomeric covalent probes revealed significant differences in the proteins modified by these probes in living cells, underscoring the importance of the warhead’s configuration in selectively modifying the target protein. Both ligand-directed and warhead-directed studies have demonstrated that covalent warheads with chiral structures are of great value in drug discovery37,38. Compared to N-acrylamide, the ketone-type saccharide with at least a six-membered pyran ring and a chiral center at C1, offers significant steric and chiral preference. This makes it a promising candidate for designing ketones that precisely fit the ligand-binding pockets of target proteins. Consequently, the ketone-type saccharide may exhibit high selectivity in its addition reaction with cysteine binding pockets39. However, α, β-unsaturated ketones are highly reactive to cysteine via Michael addition reactions40, which can lead to side effects in vivo41,42. Therefore, to develop highly selective saccharide covalent warheads without potential side effects, it is essential to optimize unsaturated saccharides, particularly the highly reactive α, β-unsaturated ketone-type saccharides by reducing their reactivity.

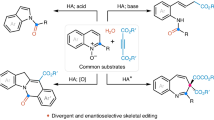

Herein, we present a one-step synthetic strategy for the facile and stereoselective synthesis of asymmetrically ketalized unsaturated saccharides, which we have named “oxazolinosene” (Scheme 1), based on our previous report on the synthesis of oxazolinose43. Further studies revealed that the developed oxazolinosene I was stable under normal physiological conditions (T1/2 ≫ 100 h) and selectively sensitive to sulfhydryl groups in glutathione (GSH) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) models. The binding rate of oxazolinosene I to GSH in PBS solution (pH = 6.8) was ten times slower than that of α, β-unsaturated ketone, which is the hydrolysate of oxazolinosene. Impressively, the ketal moieties at C2 with different carboxylic acids can be prepared via a one-pot synthesis to obtain oxazolinosene II. The thiol-ene addition of oxazolinosene II to GSH resulted in the release of carboxylic acid from the ketal into the cellular environment, potentially playing a synergistic role in the treatment of related diseases29,30.

The discovery of oxazolinosene and its thiol-ene reaction under physiological conditions. (a) The oxazolinosenes were stereoselectively synthesized via a one-step reaction of nitriles with saccharides and conveniently converted into a series of α, β-unsaturated ketone N-glycosides. (b) The acetyl group of the ketal moiety on the saccharide ring can be converted to other carboxylic acids in a one-pot synthesis. In this way, the loaded acid can be click-released during cysteine conjugation.

Results and discussion

Identification of oxazolinosenes and optimization of their synthetic conditions

The oxazolinosene 3A was obtained via the reaction between β-D-glucose penta-acetate (0.5 mmol) and benzonitrile (0.5 mmol) in anhydrous solution and was subsequently used as a model reaction to optimize the reaction conditions (Table 1). In dichloromethane (DCM) at room temperature with one equivalent of trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TfOH), 3A was obtained in a 16% yield (entry 1). No product formation was observed with other Brønsted acids, such as trifluoroacetic acid (entries 2–4). Increasing the amount of TfOH to three equivalents improved the yield to 40%, compared to using two or four equivalents (entries 5–7). Raising the reaction temperature to 40 °C further increased the yield to 60% (entry 8). However, at 60 °C, the yield in 1, 2-dichloroethane (DCE) dropped to 42% (entry 9). Screening other solvents resulted in no product formation (entries 10–12).

Substrate screening

The scope of nitriles and saccharides used to prepare the oxazolinosenes, along with the absolute configuration of 3A determined by X-ray crystallography (deposition number 2036192, Supplementary Data 3), is shown in Scheme 2. During the screening process, we discovered that the main products (3A–3Q) possessed diastereomers (3A’–3Q’), which could be separated using a silica gel column CombiFlash. However, only small amounts of the minor diastereomers (approximately 5 mg) were obtained when the reactions were prepared on a 1 mmol scale. For the purified diastereomer 3A’, the circular dichroism (CD) spectrum showed that its signals were exactly opposite to that of 3A, indicating that the chirality of 3A’ at C1 and C2 is opposite to that of 3A. To further determine the purity of the purified major products (3A–3Q), we tested different HPLC conditions and found that a chiral HPLC column was an effective approach in separating the mixture of major and minor products. Therefore, all major products were purified with the CombiFlash, and the chiral HPLC was used to determine the purity of the purified major products (Supporting Information II-2). The yields of nitriles with electron-donating groups ranged from 48% to 91%, and their d.e. values ranged from 83% to 93% (3B–3E). Halogenated substrates produced low to moderate amounts of products with d.e. values of range from 86% to 90% (3F: 24%, 3G: 30%, 3H: 53%). A relatively low yield was obtained for a trifluoromethyl-substituted nitrile with an electron-withdrawing group (3I: 34%; 85% d.e.). Other nitriles, such as alkynyl (3J: 32%), phenyl (3M: 34%), and those with multiple substituents (3K: 14% and 3L: 40%), also gave low-to-moderate yields. Compound 3J exhibited the lowest diastereoselectivity (76% d.e.) compared to 3M (85% d.e.), which had small amounts of diastereomers. A lower yield of 3K (14%) and 3L (40%) were obtained. Their diastereomers could not be separated using a common silica gel column. We also screened for heteroaryl nitriles. Products containing furanyl (3O: 54%) and naphthyl (3N: 74%) groups were successfully obtained in acceptable yields and good d.e. values. Changing the orientation of the thienyl groups resulted in yield variations and optical purities (3P: 67% yield, 89% d.e.; 3Q: 52% yield, 85% d.e.). However, no products were obtained for cyanide substrates containing basic nitrogen atoms (3Q: n.p.). In general, nitriles with electron-rich properties favored the formation of oxazolinosenes, while nitriles with electron-deficient properties resulted in lower yields.

The scope of nitriles and saccharidesa. (a) The reaction was performed at 0.5 mmol scale using saccharide and trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (3 eq) at 40 °C in anhydrous DCM for 30 min. Then, nitrile (1 eq) was added, and the mixture was stirred under a nitrogen atmosphere for 2 h; (b) HPLC yields; (c) The d.e. values were calculated based on the separated yields of main products and their diastereomers. (d) N.P. no product was found; (e) N.D. the isomer of fucose-type products could not be separated by HPLC, N.S. no stereoselectivity. (f) A mixture of 3A (0.6 mg) and 3A’ (0.3 mg) was dissolved in methanol (1 ml). Then the mixture was separated using an Agilent Pursuit 5 μM, C18 250*4.6 mm column, and CHIRALCEL OD-RH 5 μM 4.6*150 mm column. The elution solvent consisted of water and methanol, the methanol concentration was increased from 5% to 95% over 30 min and subsequently maintained at 95% methanol for an additional 15 min.

Subsequently, five different saccharides were screened, and the corresponding oxazolinosenes were successfully obtained. Interestingly, the major product obtained from both galactose penta-acetate and mannose penta-acetate was 3A. The deoxygenation or removal of the hydroxymethyl group at the C5 position of the saccharides hindered the oxazolinosene formation. For instance, fucose gave products 4A and 4D in low isolated yields (7% and 22%, respectively), with unmeasurable d.e. values. Xylose and ribose gave the product 4B in 34% and 38% yields, respectively, gave racemic mixtures. Similar results were obtained in 4C, indicating that racemization cannot be attributed to nitriles (Supplementary Data 1, Compound 4C). Therefore, the C5 hydroxymethyl group plays a crucial role in controlling the C1 configuration of oxazolinosenes. To further explore the impact of protective groups (Pgs) on the synthesis of oxazolinosene, ten saccharides with different Pgs were prepared and then screened under the optimized conditions. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows their structures and respective yields (5A–J), demonstrating that saccharides with various Pgs can effectively produce the corresponding products.

Proposed mechanisms for the synthesis of 3A and experimental validation

To understand the mechanism of 3A formation, a computational study using density functional theory (DFT) at the M06-2X/6-311G(d) level was performed using Gaussian-1644,45 for geometry optimization, frequency analysis, and a transition state (TS) search in DCM solvent (Supplementary Fig. 2). The proposed reaction pathway and free energy profiles are summarized in Scheme 3A, B. The reaction started with a protonated β-D-glucose penta-acetate (1A1), followed by the removal of acetic acid, leading to the formation of oxocarbenium 1A2’46. This was followed by the elimination of acetic acid at the C3 position to form 1A2 in anhydrous DCM. The conjugation effect of oxocarbenium makes the 2,3-elimination product the preferred intermediate47. The free energy calculation results indicated that the acetoxy group at C6 could greatly stabilize the oxocarbenium cation by immediately forming a seven-membered ring of 1A348,49. It was observed that if the nitrile directly attacks C1 of 1A3, the C-N bond configuration of the main product will consist of 3A’ (Scheme 3C 1A6-2). However, only a small amount of 3A’ was obtained during the screening. This contradictory result indicated the presence of an intermediate whose chirality at C1 differs from 1A3. A small amount of TfO- or nitrile (Scheme 3C 1A4-2, 1A6-2) could directly attack C1, leading to the formation of 3A’ in small quantities. Consequently, 1A4 was formed as an intermediate through the attack of TfO- on C1 of 1A3. The lower d.e. value of compound 4B compared to 3A can be attributed to the absence of the C6 acetoxy group on ribose and xylose, allowing TfO- to attach to C1 from both sides, resulting in an approximately 1:1 ratio of R and S xylose-type intermediates. Thus, the racemic xylose-type oxazolinosene was obtained (Supporting Information II-2 Compound 4B and 4C). The chirality of 1A4 restricted the nitrogen atom of benzonitrile from attacking C1 from the opposite side, leading to the formation of 1A6 in a β-C-N bond via transition state (TS) 1A5, which has a free energy barrier of 23.12 kcal/mol. The nucleophilicity of this oxygen atom is theoretically low due to the electron-withdrawing effect of the acetyl group. Cyclization of the oxazoline ring occurred from 1A4 via two transition states (1A5 and 1A7), resulting in the formation of intermediates 1A6 and 1A8. The free energy barriers for these two transition states were 23.12 and 18.48 kcal/mol, respectively. Notably, acetic trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride (TfOAc) was trapped by benzonitrile, the starting material (Scheme 4A), suggesting that the breakage of ester bond to form an acetyl group would occur.

Proposed mechanisms of 3A synthesis and quantum chemical calculations. A The mechanisms are summarized according to the computational study and several control experiments. B The energies of the intermediates and transition states are presented according to the calculations (kcal/mol). C The illustration of 3A’ generation.

Controlled experiments for mechanism validation. A The side product 2B was isolated from the reaction mixture of 3A. B 1D (galactose) was screened to obtain 3A. C S5 (equimolar with 1A) was added at the beginning of the reaction, and the other procedure was the same as that used for synthesizing 3A. D The external acid 8A, 8B (3 eq) was first dissolved in DCM, and then the other reactants were added according to the optimized conditions.

Finally, with the assistance of TfOH, the acetoxy group at C4 was removed, resulting in the formation of the key intermediate, carbocation 1A9. This carbocation then reacts with an internal acetic acid, ultimately yielding 3A. The calculations revealed that the free energy of the intermediate 3A-1 was higher than that of 3A by 11.96 kcal/mol. Accordingly, 3A should be the main product of this reaction step.

Another potential pathway from 1A8 to 3A could involve a [3,3]-oxa-sigmatropic rearrangement to form 1A1050. To explore this mechanism, we conducted controlled experiments to investigate the reaction pathway from 1A8 to 3A. Our results indicated that the configurational control of asymmetric ketal 3A was identical to that of galactose penta-acetate, in which the acetoxy group at C4 had the opposite configuration. This result was inconsistent with the expected product of the sigmatropic rearrangement (Scheme 4B). In addition, under optimized conditions, a crossover experiment was performed using equal amounts of glucose penta-acetate (1A), glucopyranose penta-benzoate (S5), and two equivalents of benzonitrile (2A). Four products, 3A, 3A2, 3A3, and 3A4, were obtained in comparable yields. This suggested that a 1A9-like intermediate may exist in the reaction from 1A8 to 3A (Scheme 4C). To further verify this observation, a stoichiometric excess of benzoic acids (8A or 8B) was added to the reaction mixture at the beginning of the reaction to capture the key intermediate 1A9, resulting in the successful formation of 9A or 9B, with benzoyloxy substitution at the C2 position in good yields (Scheme 4D). These control experiment results provided evidence for the proposed mechanisms, indicating that carbocation 1A9 is a key intermediate.

Chemical conversions of oxazolinosene 3A and in-tube thiol-ene addition reactions

The chemical reactivity of oxazolinosene 3A was investigated and is presented in Scheme 5A. Compound 3A can be quantitatively hydrolyzed to α, β-unsaturated ketone 6A. Furthermore, when halogenation reagents such as NBS and ICl were used, C3 halogenated α, β-unsaturated ketoses 6B and 6C were obtained in good yields (72% and 68%, respectively, Scheme 5B). The regioselectivity of halogenation was determined using heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) spectral signals (Supporting Information III compound 6B). These unsaturated ketones are important intermediates in the synthesis of drugs or natural products. Compound 3A was used in a thiol-ene addition reaction with cysteine residues. Cysteine, lysine, serine, and threonine were first dissolved in a PBS buffer solution containing 10% DMSO (pH = 7.4). Compound 3A was then added and incubated for 12 h. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that 3A reacted exclusively with cysteine to form 7A1. To further elucidate the selectivity of oxazolinosene toward cysteine, 3A was mixed with each of the four amino acids (Cys, Lys, Ser, and Thr) under the same condition. It was observed that 3A was only consumed in the cysteine solution, exhibiting high stability in solutions of the other three nucleophilic amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 3). N-Acetyl-L-cysteine and its esters were also screened, yielding 7A2 and 7A3, indicating that 3A specifically conjugates with the sulfhydryl group to generate target adducts. Further experiments demonstrated that 3A can react with other peptides containing cysteine residues, such as glutathione (GSH) and pentapeptide, to generate adducts 7B, 7C. This indicates that 3A specifically targets the sulfhydryl group to form target adducts. The presence of other nucleophilic groups, such as the amino group of lysine, did not affect the thiol-ene addition reaction. We also investigated two other peptides containing α-amino, ε-amino, hydroxyl, and disulfide bonds and carboxyl groups. However, due to the absence of free cysteine residues, no adducts were formed (7D, 7E).

Chemical conversions of compound 3A. A a: 3A was reacted with equimolar of TfOH to obtain (6A)/NBS to obtain (6B)/ICl to obtain (6C) in DCM at room temperature for 4 h; b: isolated yield. B c: Cysteine (0.1 mmol), lysine (0.1 mmol), serine (0.1 mmol), and threonine (0.1 mmol) were dissolved in pH 7.4 buffer supplemented with 10% DMSO. Then, 3A (0.4 mmol) was added to the solution. After 12 h of incubation, mass spectrometry was used to determine the product 7A1. d: Six peptides were reacted with 3A at a pH 7.4 buffer containing 10% DMSO to form the corresponding adducts. A pH 7.4 buffer containing 50% methanol was used to dissolve the 3A and GSH while stirring for 4 h at 20 °C, and then, the mixture was analyzed with LC-MS to detect Compound 6D. e: 6A can react with GSH at a pH 7.4 buffer with 50% methanol at room temperature. C 3A was dissolved in PBS (pH = 6.8 or 7.4, respectively) supplemented with 10% DMSO, after which the sample was subjected to HPLC. The peak area of 3A was tested to determine the stability at room temperature.

When compound 6A and GSH were added to a PBS solution containing 10% DMSO, no adduct 7B was formed. However, using a PBS solution (pH 7.4) with 50% methanol, the desired product was formed successfully, likely due to the improved dissolution of 6A. To further investigate the thiol-ene mechanism of oxazolinosene with GSH, we analyzed the reaction intermediate using LC-MS and identified α, β unsaturated ketose 6A, and an enol-type intermediate 6D (Supplementary Fig. 10). Additionally, we tested the reaction half-life of 3A in PBS solutions containing 10% DMSO (pH = 7.4 and 6.8, Scheme 5C and Supplementary Fig. 4). The half-life values were both greater than 100 h, indicating that 3A was not hydrolyzed in either solution. These results suggested that the enol-type intermediate 6D may participate in the reaction more readily than 6A.

The development of covalent warheads or chemical probes typically requires reactivity with free cysteine residues, making it essential to determine the conjugation rate of oxazolinosenes with GSH. The reactivities of two oxazolinosenes (3A and 3A3), α, β-unsaturated ketose 6A, and cinnamaldehyde (Cin), with GSH are shown in Scheme 6A and Supplementary Fig. 5. Four electrophiles were reacted with an equimolar amount of GSH at 20 °C, and their half-lives were calculated using a first-order kinetic equation. Among them, 6A showed the fastest response to GSH (T1/2 = 2.9 h), while the responses of 3A (6.2 h) and 3A3 (12.6 h) were slower than that of 6A but faster than Cin (18.6 h).

Exploration of the reaction kinetics of thiol-ene addition to oxazolinosene and GSH. A Different electrophiles (0.2 mmol) were incubated with an equimolar amount of GSH in a pH 7.4 buffer solution containing 50% methanol (20 ml) at 20 °C. The peak area of the electrophile was normalized to that of Compound 3A. Linear regression was performed for the peak area following the first-order kinetic equation. Their half-lives were calculated as T1/2 = ln 2/−slope. B 3A and 6A were incubated with different equivalents of GSH in a PBS buffer solution containing 50% methanol (20 ml) at 37 °C. Linear regression was performed for the peak area following the first-order kinetic equation. Their half-lives were calculated as T1/2 = ln 2/−slope. C Changes in the amounts of 3A3 and the products of 3A3 reacting with GSH in the mixture. D Structures of 3A, 3A3, 6A and cinnamaldehyde.

Utilizing the preliminary results, we tested the reactivity of 3A in solutions mimicking the Tumor Micro-environment (TME) and normal cells at pH 7.4 or 6.851. Given that the concentration of GSH in tumor cells is 1000 times greater than in normal cells in vivo52, we measured the reaction rate of the covalent warhead at a concentration of 100 μM53. At 37 °C, 3A (100 μM) was reacted with equimolar amounts of GSH (pH = 7.4) and 100 mM GSH (pH = 6.8). The reaction of 3A with GSH proceeded faster at 37 °C than at room temperature (T1/2 = 2.80 h vs. 6.2 h) but was still slower than that of 6A (Scheme 6B and Supplementary Fig. 6, 2.80 h vs. 0.13 h). Increasing the amount of GSH to 1000 equivalents resulted in a 6-fold increase in thiol-ene addition compared to equimolar conditions (2.80 h vs. 0.45 h). No significant difference was observed in the reaction rate of 6A with GSH between the two concentrations (less than 10 min). Consequently, 3A exhibited a faster reaction rate with GSH in the TME compared to normal cells. The rapid reaction rate of 6A may contribute to strong off-target effects, rendering oxazolinosene 3A a more suitable candidate for the development of covalent inhibitors or chemical probes.

The quantities of 3A3 reactants and products were sequentially documented in Scheme 6C. As the reaction progressed, 3A3 was progressively consumed, resulting in the formation of adduct 7B and benzoic acid (BzOH). Throughout the reaction, the concentration of 6A remained low. Consequently, during the thiol-ene addition reaction, the carboxylic acid (BzOH in this instance) could be released into the solution.

We noted that the reactivity of oxazolinosene with GSH can be adjusted by altering the ketal moiety at C2. In further exploration of the methods to fine-tune this reactivity, we varied the substituents of the nitriles and saccharides (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). Our findings revealed that both nitriles and saccharides can significantly influence the reaction rates of oxazolinosenes with GSH. Nineteen oxazolinosenes exhibited varying reaction rates with GSH, all of which were faster than that of acrylamide but slower than 6A. The calculated half-lives for each compound are outlined in Supplementary Scheme 2. Notably, the reaction rate of the glucose-type oxazolinosene 3A (0.48 h) was slower than that of the xylose-type product 4C (0.31 h). The thiophene-containing structure 3Q displayed a notably slower rate, approximately seven times slower than the 4-alkynyl benzonitrile product 3J (1.45 h vs. 0.2 h) and 16 times slower than 6A (0.09 h). Furthermore, the position of the substituent also impacted the GSH conjugation rate. For instance, the reaction rate of 3-methoxybenzonitrile-type products (3D) with GSH was twice as fast as that of 3C (0.39 h vs. 0.75 h). These results suggest that the reactivity of oxazolinosenes is influenced not only by the carboxylic acids at the C2 position but also by changes in the structures of the nitriles and saccharides.

These findings suggest that oxazolinosenes can engage in thiol-ene reactions within tubes via special mechanisms. The moderate T1/2 value of 3A falls between that of α, β-unsaturated ketone 6A, and Cin, indicating a mild reactivity towards cysteine. This characteristic renders 3A a promising candidate for potential covalent drug development. Moreover, the impact of GSH conjugation can be adjusted through modifications to the ketal, nitrile, and saccharide components. While most ketal structures in oxazolinosenes solutions remained unhydrolyzed to 6A, in GSH-rich environments like the TME, oxazolinosenes can readily conjugate with cysteine residues, releasing the leaving group into the solution promptly. Consequently, the distinct properties of oxazolinosenes make them potential multifunctional cysteine-targeting covalent warheads for loading and click-releasing drug molecules.

Thiol-ene addition in living cells as a GSH depletor or covalent warhead

Changing the GSH/GSSG ratio in cancer cells can lead to intracellular oxidative stress, potentially resulting in the inhibition of cell growth54. We have shown that oxazolinosene 3A can conjugate with GSH in PBS solution at a moderate rate. Therefore, it can also be used as a GSH depleting agent. Initially, cytotoxicity tests of 3A, 3A3, 6A, and Cin were performed. The results showed that 3A, 3A3, and Cin exhibited mild cytostatic effects on the viability of NCI-H1299 cells. The best inhibitory activity was achieved with 6A (Scheme 7A and Supplementary Scheme 3). Subsequently, the capability of these compounds to eliminate or deplete GSH was then assessed using GSH and GSSG Assay Kits. GSH activities were significantly depleted in 6A-treated cells. 3A showed a moderate depletion of GSH abundance and was superior to Cin and 3A3 (Scheme 7B). To verify the thiol-ene addition of oxazolinosene and GSH in cells, the presence of 7B was determined using LC-MS. The NCI-H1299 cells and cell lysates were each incubated with 3A for 4 h. Both samples were subjected to LC‒MS spectral analysis. Adduct 7B was detected in all the samples (Scheme 7C and Supplementary Fig. 12).

Conjugation of oxazolinosenes to cysteine in cells and proteins. A H1299 cells were treated with different concentrations of compounds for 72 h, cell viability was measured using a CCK-8 kit, and the IC50 value of each compound was calculated by GraphPrism software. B H1299 cells were treated with DMSO, 3A, 3A3, 6A, or cinnamaldehyde (Cin) for 3 h at a final concentration of 100 μM. The relative levels of GSH in each sample were determined with a GSH and GSSG Assay Kit, and the data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, compared with the 3A group, t-test). C The workflow for the identification of glutathione-compound conjugates in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 12). D Modification of the free cysteine residue on BSA (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Within this experimental framework, GSH depletion is usually associated with ferroptosis inducer55, radiotherapy enhancement56, and the establishment of a GSH-sensitive drug delivery system57. Our intracellular tests showed that 3A was a more effective GSH scavenger in both aqueous solution and cell culture than Cin, which is widely used in GSH-sensitive drug delivery systems.

Moreover, our findings indicated that 3A3 exhibited lower reactivity with GSH compared to 3A, demonstrating that external acids with steric hindrance can modulate the conjugation reactivity. Additionally, structural modifications of saccharides and nitriles offer additional avenues for adjusting reactivity. Therefore, in the future development of GSH scavengers or covalent drugs, careful consideration of conjugation rates will be essential when selecting nitriles or saccharides. For covalent inhibitors, oxazolinosenes with slower reaction rates, such as compound 3Q, may be preferable, while oxazolinosenes like 3J could be better suited as GSH depletors. Alternatively, the asymmetrical ketal moiety of the oxazolinosene can be regarded as a “cargo”, carried by the unsaturated saccharide. For example, the anti-tumor drug bexarotene 8B58 was selected as a model to obtain compound 9B (Scheme 4D), which also proved that complex drug molecules can be incorporated into oxazolinosene. It is therefore predicted that bexarotene (or other loaded “cargo”) could be released to the tumor cells concurrently with thiol-ene addition, thereby exerting a synergistic effect on treating the target disease.

Modification of CYS residues in proteins

To further explore the potential application of oxazolinosene in covalent drug design, we conducted bio-MS studies to confirm its ability to modify free cysteine residues in proteins. Compounds 3A, 3A3, and 6A were incubated with BSA in Tris-HCl solution at 37 °C for 12 h, and the resulting samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The modification of free cysteine residues in the ligand-binding pocket of BSA was identified in all three samples (Scheme 7D). Thus, we believe that oxazolinosenes may be valuable tools in medicinal chemistry for targeting cysteine residues in covalent drug design.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed a facile method for the stereoselective synthesis of novel unsaturated and asymmetric ketalized saccharides (oxazolinosenes) using commercially available saccharides and nitriles under acid-catalyzed conditions. These oxazolinosenes are stable in PBS and can be conveniently converted into a series of α, β-unsaturated ketoses, making them versatile synthetic building blocks. The unsaturated and asymmetrically ketalized moiety of oxazolinosene has demonstrated specificity in facilitating thiol-ene addition to cysteine residues in peptides. This reactivity extends to the modification of free cysteine residues within the ligand-binding pocket of bovine serum albumin (BSA) under normal physiological conditions. As a result, oxazolinosene can deplete glutathione (GSH) levels in NCI-H1299 cells, which in turn induces anti-tumor activity in vitro. In addition, the changeable ketal moiety can serve as a carrier for the covalent drug-localized releaser, providing additional drug potentiation.

Method

General procedure for the synthesis of oxazolinosene

All the instruments used in this manuscript were listed in the Supplementary Methods.

To a solution of saccharide (0.5 mmol), TfOH (trifluoromethanesulfonic acid) (1.5 mmol) in dry DCM (dichloromethane) was added. Stirring the reaction mixture at 40 °C for 30 min, nitrile (0.5 mmol) was added. Keep the solution stirred at 40 °C for 2 h. Then, the mixture was poured into water (20 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (20 mL) three times. The organic layers were combined and washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product which was purified by a silica gel column.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, Supplementary Information and other files. All the NMR Spectra can be found in Supplementary Data 1. Supplementary Data 2 summarize the M06-2X/6-311G(d) Cartesian coordinates of computational study. Supplementary Data 3 is the X-ray data file of compound 3A. Supplementary Data 4 provide the value of each data point shown in Schemes 5–7.

References

Vansoest, P. J., Robertson, J. B. & Lewis, B. A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74, 3583–3597 (1991).

Meroueh, S. O. et al. Three-dimensional structure of the bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4404–4409 (2006).

Preston, A., Mandrell, R. E., Gibson, B. W. & Apicella, M. A. The lipooligosaccharides of pathogenic gram-negative bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 139–180 (1996).

Bucior, I. & Burger, M. M. Carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions in cell recognition. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 631–637 (2004).

Bucior, I. & Burger, M. M. Carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction as a major force initiating cell-cell recognition. Glycoconj. J. 21, 111–123 (2004).

Bucior, I., Scheuring, S., Engel, A. & Burger, M. M. Carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction provides adhesion force and specificity for cellular recognition. J. Cell Biol. 165, 529–537 (2004).

Crich, D. En route to the transformation of glycoscience: a chemist’s perspective on internal and external crossroads in glycochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17–34 (2021).

Yamatsugu, K. & Kanai, M. Catalytic approaches to chemo- and site-selective transformation of carbohydrates. Chem. Rev. 123, 6793–6838 (2023).

Bennett, C. S. & Galan, M. C. Methods for 2-deoxyglycoside synthesis. Chem. Rev. 118, 7931–7985 (2018).

Shivatare, S. S., Shivatare, V. S. & Wong, C. H. Glycoconjugates: synthesis, functional studies, and therapeutic developments. Chem. Rev. 122, 15603–15671 (2022).

Zhu, D. P., Geng, M. Y. & Yu, B. Total synthesis of starfish cyclic steroid glycosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203239 (2022).

Ohyabu, N., Nishikawa, T. & Isobe, M. First asymmetric total synthesis of tetrodotoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 8798–8805 (2003).

Mahal, L. K., Yarema, K. J. & Bertozzi, C. R. Engineering chemical reactivity on cell surfaces through oligosaccharide biosynthesis. Science 276, 1125–1128 (1997).

Dube, D. H. & Bertozzi, C. R. Metabolic oligosaccharide engineering as a tool for glycobiology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 616–625 (2003).

Prescher, J. A., Dube, D. H. & Bertozzi, C. R. Chemical remodelling of cell surfaces in living animals. Nature 430, 873–877 (2004).

Hsu, T. L. et al. Alkynyl sugar analogs for the labeling and visualization of glycoconjugates in cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2614–2619 (2007).

Laughlin, S. T. et al. Metabolic labeling of glycans with azido sugars for visualization and glycoproteomics. Methods Enzymol 415, 230–250 (2006).

Kufleitner, M., Haiber, L. M. & Wittmann, V. Metabolic glycoengineering—exploring glycosylation with bioorthogonal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 510–535 (2023).

Sutanto, F., Konstantinidou, M. & Domling, A. Covalent inhibitors: a rational approach to drug discovery. RSC Med. Chem. 11, 876–884 (2020).

Johnson, D. S., Weerapana, E. & Cravatt, B. F. Strategies for discovering and derisking covalent, irreversible enzyme inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2, 949–964 (2010).

Du, J. et al. cBinderDB: a covalent binding agent database. Bioinformatics 33, 1258–1260 (2017).

Gersch, M., Kreuzer, J. & Sieber, S. A. Electrophilic natural products and their biological targets. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 659–682 (2012).

Marino, S. M. & Gladyshev, V. N. Cysteine function governs its conservation and degeneration and restricts its utilization on protein surfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 902–916 (2010).

Catalan, J. Influence of inductive effects and polarizability on the acid-base properties of alkyl compounds. Inversion of the alcohol acidity scale. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 9, 652–660 (1996).

Pan, Z. Y. et al. Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Chemmedchem 2, 58–61 (2007).

Ren, P. X. et al. Discovery and mechanism study of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitors with a new reactive group. J. Med. Chem. 66, 12266–12283 (2023).

Ngo, C. et al. Alkyne as a latent warhead to covalently target SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Med. Chem. 66, 12237–12248 (2023).

Riddhidev, B. et al. Rational design of metabolically stable HDAC inhibitors: an overhaul of trifluoromethyl ketones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 244, 114807 (2022).

Wen, W. et al. N-Acylamino saccharin as an emerging cysteine-directed covalent warhead and its application in the identification of novel FBPase inhibitors toward glucose reduction. J. Med. Chem. 65, 9126–9143 (2022).

Reddi, R. N. et al. Tunable methacrylamides for covalent ligand directed release chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4979–4992 (2021).

Hu, Y., Zhang, Z., Yin, Y. & Tang, G. L. Directed biosynthesis of iso-aclacinomycins with improved anticancer activity. Org. Lett. 22, 150–154 (2020).

Santos, J. A. M. et al. Structure-based design, synthesis and antitumoral evaluation of enulosides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 128, 192–201 (2017).

Goto, K. et al. Synthesis of 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose derivatives and evaluation of their inflammasome inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 3763–3772 (2018).

Han, J. J. et al. Terphenyl derivatives and terpenoids from a wheat-born mold Aspergillus candidus. J. Antibiot. 73, 189–193 (2020).

Jackson, P. A., Widen, J. C., Harki, D. A. & Brummond, K. M. Covalent modifiers: a chemical perspective on the reactivity of α,β-unsaturated carbonyls with thiols via hetero-Michael addition reactions. J. Med. Chem. 60, 839–885 (2017).

Abrányi-Balogh, P. et al. A road map for prioritizing warheads for cysteine targeting covalent inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 160, 94–107 (2018).

Cuesta, A., Wan, X. B., Burlingame, A. L. & Taunton, J. Ligand conformational bias drives enantioselective modification of a surface-exposed lysine on Hsp90. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3392–3400 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Direct mapping of ligandable tyrosines and lysines in cells with chiral sulfonyl fluoride probes. Nat. Chem. 15, 1616–1625 (2023).

Singh, J., Petter, R. C., Baillie, T. A. & Whitty, A. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 307–317 (2011).

Hexum, J. K., Tello-Aburto, R., Struntz, N. B., Harned, A. M. & Harki, D. A. Bicyclic cyclohexenones as inhibitors of NF-κB signaling. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 3, 459–464 (2012).

Uetrecht, J. Immune-mediated adverse drug reactions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 22, 24–34 (2009).

Zhang, X. C., Liu, F., Chen, X., Zhu, X. & Uetrecht, J. Involvement of the immune system in idiosyncratic drug reactions. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 26, 47–59 (2011).

Dong, S. F. et al. One step stereoselective synthesis of oxazoline-fused saccharides and their conversion into the corresponding 1,2-cis glycosylamines bearing various protected groups. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 1580–1588 (2021).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01. (2016).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Ranade, S. C. & Demchenko, A. V. Mechanism of chemical glycosylation: focus on the mode of activation and departure of anomeric leaving groups. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 32, 1–43 (2013).

ElNemr, A. & Tsuchiya, T. alpha-Hydrogen elimination in some 3- and 4-triflates of alpha-D-glycopyranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 301, 77–87 (1997).

Crawford, C. J. & Seeberger, P. H. Advances in glycoside and oligosaccharide synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 7773–7801 (2023).

Singh, Y., Geringer, S. A. & Demchenko, A. V. Synthesis and glycosidation of anomeric halides: evolution from early studies to modern methods of the 21st century. Chem. Rev. 122, 11701–11758 (2022).

Mirabella, S. et al. Allyl cyanate/isocyanate rearrangement in glycals: stereoselective synthesis of 1-amino and diamino sugar derivatives. Org. Lett. 22, 9041–9046 (2020).

Feng, L. Z., Dong, Z. L., Tao, D. L., Zhang, Y. C. & Liu, Z. The acidic tumor microenvironment: a target for smart cancer nano-theranostics. Natl Sci. Rev. 5, 269–286 (2018).

Yin, C. et al. A single composition architecture-based nanoprobe for ratiometric photoacoustic imaging of glutathione (GSH) in living mice. Small 14, 1703400 (2018).

Bodnarchuk, M. S., Cassar, D. J., Kettle, J. G., Robb, G. & Ward, R. A. Drugging the undruggable: a computational chemist’s view of KRASG12C. RSC Med. Chem. 12, 609–614 (2021).

She, T. T. et al. Sarsaparilla (smilax glabra rhizome) extract inhibits cancer cell growth by S phase arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy via redox-dependent ERK1/2 pathway. Cancer Prev. Res. 8, 464–474 (2015).

Pan, W. L. et al. Microenvironment-driven sequential ferroptosis, photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy for targeted breast cancer therapy by a cancer-cell-membrane-coated nanoscale metal-organic framework. Biomaterials 283, 121449 (2022).

Zhang, X. D. et al. Glutathione-depleting gold nanoclusters for enhanced cancer radiotherapy through synergistic external and internal regulations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 10601–10606 (2018).

Geng, P. et al. GSH-sensitive nanoscale Mn3+-sealed coordination particles as activatable drug delivery systems for synergistic photodynamic-chemo therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 31440–31451 (2021).

Lowe, M. N. & Plosker, G. L. Bexarotene. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 1, 245–250 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Professors Jingshan Shen and Xiangrui Jiang from Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (SIMM), CAS, for their valuable discussions and assistance with this project. We have many thanks to Professor Tiehai Li from SIMM, Dr. Wouter Remmerswaal and Dr. William Darling from Mate’s group of Uppsala University, for helping us revising the manuscript and Dr. Ruisheng Xiong from Uppsala University for his kind discussions with us about the 2D-NMR experiments. We extend our special thanks to Professor Guangbo Ge from the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for conducting the preliminary enzyme activity screening. We appreciate for the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1004304); National Natural Science Foundation of China (22077131; 22277129); Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project; Chinese Pharmaceutical Association-Yiling Biopharmaceutical Innovation Project (CPAYLJ201908); the State Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs (K202108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sanfeng Dong contributed to the compound synthesis and the manuscript writing. Hui Huang performed the biological activity evaluation and the manuscript revision. Jintian Li carried out the computational study. Xiaomei Li helped to do some synthetic experiments. Yingxia Li, Hu Zhou, Bo Li, and Weiliang Zhu conceived and designed the experiments, and revised the manuscript for the final decision. Other authors took part in the discussion about the experiments and manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, S., Huang, H., Li, J. et al. Development of ketalized unsaturated saccharides as multifunctional cysteine-targeting covalent warheads. Commun Chem 7, 201 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01279-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01279-z

This article is cited by

-

Covalent chemical probes

Communications Chemistry (2025)