Abstract

Liquid-like protein condensates are ubiquitous in cellular system and are increasingly recognized for their roles in physiological processes. Condensed phase harbors distinctive chemical microenvironment, markedly different than dilute aqueous phase. Herein, we demonstrate chemoselective modification pattern of nucleophilic canonical amino acid sidechains (namely – cysteine, tyrosine and lysine) of the protein towards 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan in the dilute and condensed phase. We also delineate how the effect of nucleotides and their in situ enzymatic dissociation temporally modulate the protein condensate’s pH and the protein’s corresponding chemoselective modification. We have shown that the pH of the condensate decreases in the presence of nucleoside triphosphate, whereas it increases in the presence of nucleoside monophosphates or phosphate ion. For instance, we find lysine-specific modification gets inhibited in the presence of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), but significantly enhanced in the presence of monophosphates. This feature enables us to gain temporal control over dynamic change in protein functionalization via enzymatic ATP hydrolysis. Overall, this work substantiates the alteration in pH-responsiveness of Brønsted basicity of a protein’s ε-amine in the condensed phase. Furthermore, this environment sensitivity in chemoselective protein functionalization in condensed phase will be important in adaptable protein engineering to the chemical biology of protein phase separation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protein modifications (both enzymatic and non-enzymatic) are essential for a wide range of biological processes, such as - cellular signaling, disease initiation to progression, natural aging, etc1,2,3,4,5. To this end, as proteins contain a range of reactive side chains like—amines, thiols, alcohols, amides, or carboxylic acids as functional groups, their environment dependency in chemoselective modification remains an exciting challenge6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. In previous instances, chemoselective protein ligation has been reported at a particular biologically relevant pH range, in the presence of light, etc14,15,16,17,18,19. However, the situation will become complex when the surrounding environment responsible for chemoselectivity is—i) in a self-assembled state where the protein remains as a condensed phase through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and (ii) the system’s composition is modulating with time. This would be particularly fascinating when two extreme environmental end-points have different preferences over functional group modification, as the kinetics of change in surrounding conditions will govern the chemoselective output.

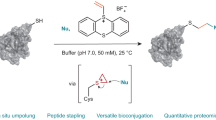

During the 1970s, Luisi et al. first demonstrated tagging of 4-Chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl) in lysozyme at diverse pH ranges and reported that NBD tagging at tyrosine and lysine residues increases with basic pH20,21. However, chicken egg lysozyme is a protein devoid of cysteine (-SH) residue and contains 6 lysine and 3 tyrosine residues22. Therefore, in those reports, the functionalization rate of tyrosine (phenolic -OH) and lysine (primary amine -NH2) was reported with increasing pH. However, NBD has a higher propensity to tag with the thiol (-SH) of cysteine at physiological conditions. Herein, we used bovine serum albumin (BSA), which has 59 lysine, 20 tyrosine, and 35 cysteine (1 available in thiol form, the rest are in disulfide form) residues, and thus the competition will be more in case of BSA compared to lysozyme23. We investigated the pH effect on NBD-functionalization over cysteine, tyrosine, and lysine of BSA in aqueous solution and liquid droplet state at different pH and the presence of diverse nucleotides and phosphates (Fig. 1).

Schematic diagram describing (a) the NBD-functionalization of BSA in a CTAB-mediated condensate (liquid droplet) and (b) pH-responsive chemoselective protein NBD-functionalization in presence of ATP or ATP-hydrolyzed product AMP/Pi inside the droplet. Here, tyrosine (Y), cysteine (C) and lysine (K) can be functionalized via NBD-Cl. c Description of the symbols used for different constituents in this system.

It is worthy to mention that many recent literature reports demonstrated diverse roles of natural phosphates in several applications towards supramolecular and organic chemistry (as phosphates can have wide pH-range). It exemplifies the fascinating topic of why biology chose phosphates24,25,26,27. We also recently demonstrated how both acid or base-catalyzed reactions can be performed in a cationic nanoparticle-based system by in situ modulating the conversion of disodium salt of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to monophosphate (AMP)28,29,30. The previously found literature reports and our recent observation made us inquisitive to explore the effect of ATP and other nucleoside mono/di/triphosphates and its hydrolyzed products (also considering the vast number of adenosine-based nucleotides in biological systems) in modulating chemoselectivity of NBD-functionalization of a protein. Notably, previous literature reports demonstrate the importance of condensate as a host for chemical/enzymatic reactions and related activation/inhibition of diverse substrates at different conditions31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. However, until now, the influence of droplet state on the chemoselective side-chain modification of constituent proteins and that, too, under altering surrounding environments has not been explored. Here, we found that the modification of amine groups is augmented with a decreasing number of phosphate groups in the nucleotides and can also be controlled in a time-dependent manner by using an ATP-degrading enzyme inside the condensed phase. Additionally, we report almost unchanged or mildly altered reactivity of cysteine and tyrosine irrespective of the nucleotide and condensed phase of the protein. Overall, apart from ATP-mediated temporal control of the system in governing chemoselective protein-functionalization, this work unveils the pH-dependent changes of Brønsted basicity or nucleophilicity of a protein’s ε-amine in an assembled state, which is significantly different than the free state.

Results and discussion

Microscopic characterization and probing nucleotide-mediated change in droplet pH

We used cationic surfactant CTAB, which has the propensity to form complex coacervate with anionic protein BSA46. For all experiments, 1 mM fixed CTAB, 50 µM BSA, and 1 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) have been used.

We first checked the physical nature of the coacervate in the presence of all the nucleotides by doing microscopic imaging and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments and calculating the apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) values (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). It showed CTAB-BSA form micron-sized liquid-like droplets with high mobility (0.002-0.004 μm2 s-1). The condensates in all the samples for which the FRAP was recorded showed a liquid-like nature, and the Dapp values were comparable among them. There were still small variations in the Dapp, with ATP and Ade + Pi showing lower mobility while AMP and ADP show higher mobility than buffer. This may be due to the fact that ATP interacted stronger with CTAB than di- and mono-nucleotides. We also checked the stability of the droplets for 12 h by keeping in a closed seal hybridization chamber (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this case, with time due to Ostwald ripening, droplet sizes were increased, indicating the liquid-like nature of the droplets47. Herein, we found faster coalescence or formation of larger droplets with time in the case of AMP or Pi, compared to ADP or ATP. In other words, with decreasing number of phosphates, the coalescence behavior of the droplets increased.

a Brightfield image of CTAB-BSA droplets (taken after 2 h) inside which the BSA-NBD reaction was taking place. b Representative FRAP images of CTAB-BSAFITC (FITC-tagged BSA, 5% tagged) droplet in buffer. Pre-bleached images were taken 5 min after mixing the reaction components. c Fluorescence recovery plot of CTAB-BSAFITC droplet in the absence and presence of 0.2 mM ATP. d Dapp values for CTAB-BSAFITC droplet in the absence and presence of nucleotides and phosphate (Pi), extracted from fitting the FRAP data against an exponential function. The method of fitting is given in the Methods section. Experimental conditions: [BSA] or [BSAFITC] = 50 μM; [CTAB] = 1 mM; [NBD-Cl] = 100 μM; [HEPES] = 1 mM, pH 7. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 5).

We further checked surface zeta potential (ζ) of the droplets in the absence and presence of nucleotides (Supplementary Table 1). The ζ-value of the droplet was found to be 15 ± 4 mV, whereas ζ-value of only BSA was −30 ± 5 mV at our experimental condition. This indicates that CTAB-BSA droplet is enriched with cationic surfactant CTAB. However, ζ-value of CTAB-BSA droplet after the addition of ATP, ADP and AMP was changed to −5 ± 2, 2 ± 1 and 5 ± 2 mV, respectively. This also suggests nucleotide binding with the droplet and ATP has the highest efficiency in decreasing the surface potential of the droplet. It also prompted us to quantify the amount of nucleotide bound in the CTAB-BSA droplet. To elucidate this, we centrifuged the droplet-containing solution at 25000 × g for 60 min to precipitate the condensed part (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Then we collected the supernatant to analyze the unbound nucleotide or BSA content. We found irrespective of the presence and absence of nucleotides the amount of BSA in the supernatant is almost comparable with a value of 42-44 μM (Supplementary Fig. 3b). It suggests that only 6-8 μM of BSA was precipitated at the bottom of the centrifuge tube after centrifugation in each case. Similarly, we found the amount of ATP, ADP and AMP in the precipitated solid was around 55 ± 2, 30 ± 1.5 and 25 ± 2 μM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3c). This again suggests that ATP has the highest affinity as well as maximum residential propensity with the BSA-CTAB droplet.

Subsequently, we were interested in elucidating the change of droplet pH in the presence of nucleotides. It is worthy to mention that recently, we reported nucleotides can alter the pH of a CTAB-modified nanoparticle surface, and thereby, the catalytic preference of nanoparticles over acid-to-base-catalyzed reactions can be regulated28. Herein, we used anionic pyranine (8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid / HPTS) as a pH-responsive fluorescence probe to determine droplet pH (Fig. 3a)48,49. To check the binding of HPTS to droplets in the absence and presence of nucleotides, we did an ultrafiltration experiment with a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) membrane (Supplementary Fig. 4). The absence of HPTS in the filtrate suggests it remains with the droplet irrespective of the presence or absence of nucleotides. At first, we measured droplet pH at increasing amounts of adenosine mono/di/trinucleotides (AM/D/TP) and free phosphate ion (Pi) via fluorescence spectroscopy (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 5). Here, we found that the pH of the native CTAB-BSA droplet was around 6.5 in pH 7 buffer due to the presence of acidic protein BSA. We would also like to mention pH buffering effect of BSA was also reported in earlier literature50. Herein, we found with increasing AMP or Pi from 200 to 600 µM, the droplet pH increased from 6.7 to 7.1. Droplet pH slightly decreased to 6.3 upon the addition of 600 µM ADP. Interestingly, we noticed a sharp decrease in pH of 5.6 and 5.35 in the presence of 400 and 600 µM of ATP, respectively (Fig. 3b).

a Schematic diagram showing the pH-dependent increase in fluorescence of the dye pyranine (HPTS) and its use in this study in estimating the pH inside the BSA droplet. b Change in droplet pH in the absence and presence of AMP, ADP, ATP and Pi of varying concentrations, as determined by fluorescence spectroscopy of pyranine. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). c Representative confocal images of the pyranine-containing BSA droplet with varying fluorescence intensity, in the presence and absence of ATP and Pi. d The droplet pH corresponding to the images shown in c as an average of 10 individual droplets. Error bars represent standard deviation. Experimental condition: [CTAB] = 1 mM, [BSA] = 50 µM, [Pyranine] = 2 µM, [HEPES] = 1 mM; pH 7.0; T = 25 °C, * and ** indicate p-values of 0.013 and 0.003, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 10).

Next, we conducted control experiments to determine which droplet constituents (CTAB or BSA) predominantly influence the droplet pH in the presence or absence of nucleotides or phosphate ions (Supplementary Fig. 6). So, we checked the effect of adding nucleotides and Pi in the presence of only BSA at our experimental condition using HPTS dye (pH = 7, HEPES = 1 mM). We observed the pH of the solution remains almost unchanged in each case. Only in the presence of ATP (0.2 mM), it slightly decreased to 6.75 ± 0.05; with Pi (0.6 mM), it marginally increased to 7.12 ± 0.08 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Then, we performed a control experiment with only CTAB micelles using the same anionic HPTS dye. We found the surface pH of the micelle was around 7.7 ± 0.03 in the absence of any nucleotide or Pi. This is due to the accumulation of basic anions of the buffer salt at the micellar interface, which has already been reported in previous works28,29. Interestingly, in the presence of ATP (0.2 mM), ADP (0.2 mM), AMP (0.2 mM) and Pi (0.6 mM) the values changed to 5.6 ± 0.06, 6.7 ± 0.02, 7.7 ± 0.04 and 7.8 ± 0.06, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6b). It suggests binding of the nucleotides at the micellar interface drastically change the interfacial pH and the pH decreasing effect was very prominent in the case of ATP. We would like to mention that disodium salt of ATP contains two H+ ions as counter ions, whereas for AMP, the number of H+ is zero. Therefore, the binding of ATP increases the local H+ concentration in the surroundings, leading to decreased pH.

Now, the CTAB-BSA droplet pH (using HPTS dye via fluorescence spectroscopy) was 6.5 ± 0.04 in the absence of any nucleotide. It suggests the buffering effect of BSA was dominant inside the droplet. However, in the presence of ATP, ADP, AMP and Pi (under identical experimental conditions as mentioned before) the droplet pH changes to 6.05 ± 0.06, 6.4 ± 0.04, 6.7 ± 0.05 and 7.1 ± 0.05, respectively. Herein, we found the pH increasing effect observed for only AMP and Pi in case of only CTAB, is much less in case of droplet, indicating the buffering effect of BSA. However, in the case of ATP, a prominent decrease in droplet pH suggests the binding with CTAB inside the droplet played the dominant role.

After establishing the contents and pH of the CTAB-BSA droplets in the absence and presence of the nucleotides, we were curious to check the pH of the bulk solution. For this, we again performed centrifugation at 25000 × g to precipitate the condensed phase in solid form and then used the supernatant for measuring pH. In this case, we used both HPTS dye and pH meter reading to record the pH of the supernatant when the droplet was formed both in the absence and presence of the nucleotides and Pi (Supplementary Table 2). In this case, we found the pH values were comparable for both methods. Interestingly, we observed for ATP-doped system, the supernatant pH was around 6.3 which was 0.25 unit higher than the droplet pH. Again, supernatant pH for AMP and Pi was almost identical to that of droplet pH, as those are close to pH 7. Due to dynamic nature of the droplet, nucleotide, CTAB and BSA are also present in the bulk; therefore, the bulk pH deviates from pH = 7. In any case, this experiment indicates that the pH of the droplet decreases when ATP is present.

We also checked with other nucleoside monophosphates (NMPs) using uracil, cytosine, and guanosine (Abbreviated as UMP, CMP, and GMP), where a similar increase in droplet pH value was observed alike AMP and Pi (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The pH-alteration behavior of pyrophosphate (PPi), with two phosphate units linked with phosphoanhydride bond) was similar to ADP. The pH-decreasing trend of another nucleoside triphosphate, CTP, was like that of ATP (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). These experiments suggest the number of phosphate linkage, not the nucleobase type is the key in regulating droplet pH.

To further confirm the pH is changing on the droplet selectively, we performed a confocal microscopy experiment. Firstly, we calibrated the fluorescence intensity of the droplet in the presence of HPTS at different buffers with known pH values calculated from the spectroscopic data (Supplementary Fig. 8). Here, we also clearly found low fluorescence intensity of the droplet in the presence of ATP (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. 9). However, the fluorescence intensity increased in the presence of AMP or Pi, compared to only the buffer, corroborating our earlier observation (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Fig. 9).

Effect of droplet in chemoselective activation or inhibition of protein functionalization at diverse pH

Next, we investigated the NBD-functionalization rate over BSA in the presence of different nucleotides and pH-containing buffer in solution and liquid droplet phase. We also verified that there was no significant change in the conformation alteration of BSA via circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 10). It is well-known that NBD can, in principle, be attached to an amine group (lysine group of protein), thiol group (cysteine), and phenol group (tyrosine)20,51,52,53,54. NBD-functionalization with serine has not been observed even at basic pH (due to the much lower nucleophilicity of the alkyl hydroxy group than the amine or phenolic group) in previous instances. Therefore, we also disregarded any functionalization of the serine group20,21. Notably, UV spectral maxima for NBD-amine, thiol, and phenol are 482, 425, and 385 nm, respectively, with distinctive molar extinction co-efficient values (Supplementary Table 3)20,51,52. We also verified this fact by synthesizing model compounds (Supplementary Figs. 11–13). We followed the rate of NBD-amine/thiol/tyrosine formation in BSA by following the UV-Vis spectral pattern coupled with deconvolution at different time intervals (4–12 h) (Supplementary Figs. 14–15, see Methods for details). The number of amine-NBD, thiol-NBD, and phenol-NBD residues per protein molecule formed during reaction have been designated as λ[K(NBD)], λ[C(NBD)] and λ[Y(NBD)], respectively in this manuscript. The concentration of NBD-Cl added was fixed at 100 μM for all experiments, which is twice that of protein.

Upon analyzing experimental results, we found the reactivity of specific λ[K(NBD)] sharply enhanced by 7-10-fold in droplet condition at pH 7 buffer (Supplementary Fig. 16). However, the change of rate of λ[C(NBD)] and λ[Y(NBD)] content remains almost unchanged. This trend of increasing λ[K(NBD)] and almost non-changing λ[C(NBD)] and λ[Y(NBD)] in droplet state compared to buffer remains almost similar in other pH values (from pH 5.6 to 8.2) also (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 17–18). The enhancement of lysine-functionalization rate in droplet state compared to buffer remains ~10 fold from 5.6-7.5 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 18a). At pH 8.2, the enhancement fold is slightly lowered as the rate is higher even in free buffer. In the case of λ[C(NBD)], the droplet effect is very low, even less than 2-fold, until pH 7.5. After that, it diminished (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 18b). Interestingly, in the case of λ[Y(NBD)] droplet effect, it decreased with increasing pH (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 18c). It is probably due to the transfer of NBD from tyrosine to lysine (Supplementary Fig. 19)21,55,56. Overall, we found the formation of the droplet can indeed expedite and modulate the lysine-specific NBD functionalization at different pH. For the control experiment, we measured amine-tagging in the presence of anionic surfactant, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), cationic surfactant with lower chain length dodecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (DTAB) and by taking a lower concentration of CTAB (0.1 mM) where BSA does not form coacervate (Supplementary Figs. 20–21). A noticeably low NBD modification of lysine moiety was seen in those instances. It signifies the role of assembled protein in the droplet phase for such modification, as closely packed amine moiety can efficiently increase the nucleophilicity of amine57,58,59,60.

a Schematic diagram (left) and table (right) showing the extent of change of NBD-derivatization of different functional groups of BSA in droplet state in comparison to that in free state in solution, in the presence of acidic, neutral and basic pH buffers. (b)-(d) Plots show the change in number of lysine-NBD (b), cysteine-NBD (c) and tyrosine-NBD (d) residues (denoted as λ [K(NBD)], λ [C(NBD)] and λ [Y(NBD)] per protein molecule in BSA) at different pH, in the presence (red, droplet state) and absence (blue, solution state) of CTAB, after 12 h. Low strength buffers were used in all the experiments. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). Experimental condition: [CTAB] = 1 mM, [BSA] = 50 µM, [NBD-Cl] = 100 µM, [HEPES] = 1 mM. pH Buffers: [MES] = 1 mM for pH 5.6 and 6.0; [HEPES] = 1 mM for pH range of 6.6 to 8.2; T = 25 °C.

Nucleotide-mediated chemoselective protein functionalization pattern in a droplet state

Next, we checked the NBD-functionalization rate with C, Y, and K of BSA in the presence of nucleotides of different contents in the droplet state. Herein, we found that the rate of λ[K(NBD)] formation decreased with increasing concentration of ATP (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 22c) and increased with increasing concentration of AMP (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 24c), compared to only buffer. The rate of λ[K(NBD)] formation slightly decreased with increasing ADP content (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 23c). Notably, for Pi, the rate of increase was even higher as the amount of Pi was chosen as three times higher than ATP concentration (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 25c). This helped to distinguish the effect of the same amount of Pi in free and phosphoanhydride-bonded situations. Furthermore, we checked the effect of another trinucleotide, CTP, which behaves like ATP in terms of inhibiting NBD-tagging with lysine. The moderate inhibiting behavior of ADP and PPi and the activation effect of another nucleoside monophosphate (A/U/G/CMP) were found almost identical. We also noted the formation rate of λ[Y(NBD)] and λ[C(NBD)] in the presence of nucleotides, which were kinetically much faster than λ[K(NBD)] (Supplementary Figs. 22–25). Growth of λ[C(NBD)] content remains almost unaltered in each case, showing cysteine functionalization is pH-insensitive. For λ[Y(NBD)], a slight decrease in formation rate was observed for the ATP-doped system compared to the buffer. Otherwise, the rate of increase was almost identical (Supplementary Fig. 22a). However, for AMP and Pi after 4 h, we observed a decay in λ[Y(NBD)] and λ[C(NBD)] contents, suggesting NBD transfer from Y to K and C to K at higher pH as mentioned in the literature (Supplementary Fig. 26)21,55,56,61.

a Representative UV-vis absorption spectra of BSA-NBD reaction in presence of CTAB and in absence and presence of ATP and Pi. Here 0.2 mM ATP and 0.2 mM Ade + 0.6 mM Pi (complete hydrolyzed product of ATP) were used. Dotted lines represent deconvoluted spectra representing only the lysine (amine)-functionalized NBD. Please see Methods for the details of deconvolution protocol. b Change in λ[K(NBD)] as a function of time in absence and presence of nucleotides (0.2 mM) and phosphate (0.6 mM), in presence of CTAB. c Alteration in λ[K(NBD)] content in terms of percent increase or decrease (given in decimal) with respect to buffer in presence of different amount of nucleotides (0.2–0.6 mM) and Pi (0.6–1.8 mM) after 12 h. d–f Change in λ[K(NBD)] as a function of time (d) in presence of nucleoside triphosphate, ATP and CTP; (e) diphosphate ADP and pyrophosphate (PPi) and (f) nucleoside monophosphate, AMP, UMP, GMP and CMP. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicate measurement. Experimental condition: [CTAB] = 1 mM, [BSA] = 50 µM, [NBD-Cl] = 100 µM, [HEPES] = 1 mM; pH 7.0; T = 25 °C. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Temporal in situ alteration of pH and NBD-functionalization using an ATP-degrading enzyme

The previous experiments described in Fig. 3 indicated that converting ATP to Ade + Pi in principle can increase the droplet pH from ~5.8 to ~6.8 in situ (as per confocal data), which might alter the protein functionalization behavior with time. To observe this fact, we added different amounts of ATP hydrolyzing enzyme, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (50 and 600 nM) in the system at a fixed amount of ATP (200 μM) (Fig. 6). The amount of enzyme is almost 1000 to 80-times lower than BSA content, and thereby we ignored any modification of NBD to ALP. We found that with higher ALP, the change in droplet pH is faster, according to confocal microscopy. We used an HPTS probe to measure the droplet pH, as discussed in Fig. 3. Here, with higher enzyme content, the change in droplet pH from 5.8 to 6.5 occurred within 15 min. However, in the case of low enzyme content, it took around 60 min. It was due to the conversion of ATP to phosphate inside the droplet via enzyme and the corresponding increase in droplet pH. We, therefore, expected that lysine-specific NBD functionalization could also be upregulated with time inside the droplet system by controlling the enzymatic ATP-cleavage rate. In fact, we also find λ[K(NBD)] formation rate can be enhanced at a faster rate for high enzyme content and a slower rate for low enzyme content, while λ[Y(NBD)] and λ[C(NBD)] formation is almost constant in all these conditions (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 27). Afterwards we showed that amount of λ[K(NBD)] can be increased in a regular manner with increasing concentration of ALP in the system after 4 h (Supplementary Fig. 28). Overall, we demonstrated here ATP-triggered inhibition of λ[K(NBD)] can be reversed in a controllable manner concurrently with time via in situ enhancing droplet pH using ATP-degrading enzyme, alkaline phosphatase.

a Schematic diagram describing the temporal regulation of NBD-functionalization of BSA in a CTAB-mediated condensate by ATP-hydrolyzing enzyme alkaline phosphatase (ALP). b Representative confocal images of the pyranine-containing BSA droplet in the presence of fixed concentration of ATP and two different concentrations of ALP (50 and 600 nM), taken after 5, 15 and 60 min. c The pH of pyranine-containing BSA droplet with ATP and different concentrations of ALP, as determined from the fluorescence intensity of confocal images. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 10). d Change in λ[K(NBD)] as a function of time for BSA droplets containing ATP in the presence of different concentrations of ALP. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). Experimental condition: [CTAB] = 1 mM, [BSA] = 50 µM, [ATP] = 200 µM, [Pyranine] = 2 µM, [NBD-Cl] = 100 µM, [HEPES] = 1 mM; pH 7.0; T = 25 °C.

Understanding the diversified role of different forms of phosphate-linkage in maintaining biological processes is a topic of interest both in chemistry and biology24,25,26,27. In this context, we showed here the diversified role of nucleotides (having phosphoester to phosphoanhydride bonds) and phosphates in droplet state protein modification, simultaneously showing significance of biotransformation in the condensed state62. Lysine-specific modification gets inhibited in the presence of ATP, but significantly enhanced in the presence of monophosphates, which allows temporal control over dynamic change in protein functionalization via enzymatic ATP hydrolysis. We believe this temporal modulation of nucleotide-mediated chemoselective behavior in the liquid droplet state of protein will find immense application in bioconjugation strategies, protein engineering, and deciphering altered protein modification behavior in diverse condensed phases63.

We would also like to mention that light-mediated in situ pH change using photoresponsive molecules (like—spiropyran to merocyanine or light-induced ester hydrolysis via photocleavable unit) and corresponding alteration in micro and macroscale property is a fascinating topic of research64,65. Here, we exploited enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphoanhydride bond and the corresponding change in system pH for biomolecule functionalization in a time-dependent manner. Notably, carboxylic ester or amide hydrolysis-induced pH change has been exploited in a variety of dynamic supramolecular systems66. However, until now, the chemical system that depends on pH change due to phosphoanhydride bond hydrolysis, and the corresponding change in system property or controlling chemical reactivity is scarce. Notably, ATP-fuelled dynamic supramolecular systems and chemical information exchange are important topics of research, but this aspect of in situ pH change was not highlighted in those cases67,68,69,70. We would also like to mention that most of the systems reported ATP-driven formation of assembly or coacervate via multivalent binding with a cationic polymeric unit69,70. In contrary, here we reported ATP-mediated change of the internal environment of an already formed coacervate system without compromising the intrinsic structural aspects of the system (condensed liquid-like droplets). In a different aspect, this work gives rise to the future possibility of reversing pH via enzymatic linkage of phosphate and corresponding reactivity in situ. We believe this study can be the pathway towards diverse kinds of nucleotide-mediated chemistry and biochemistry of different (bio)molecular assembly, (bio)polymer conjugation and their temporal alteration in reactivity not only in solution state, but also in biologically more significant condensed phase (for example—in a macromolecularly crowded environment).

Methods

Materials

All commercially available reagents were used as received without any further purification. Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), bovine serum albumin fraction V (BSA), adenosine (Ade), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phenol, ammonium chloride, disodium phosphate, sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium pyrophosphate dibasic (SAPP/ PPi), 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid trisodium salt (HPTS/ Pyranine), uridine monophosphate disodium (UMP. 2Na), sodium hydroxide pellets, dodecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (DTAB), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), chloroform-d (CDCl3), MES (4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid), Tris base (tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane), (HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) were procured from Sisco Research Laboratory (SRL), India. 4-Chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (or 4-Chloro-7-nitro-1,2,3-benzoxadiazole/ NBD-Cl), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Sephadex G-25, n-octanethiol, n-octylamine, acetonitrile, alkaline phosphatase (ALP, from bovine pancreas), adenosine monophosphate (AMP. 2Na), guanosine monophosphate disodium (GMP. 2Na), adenosine triphosphate (ATP. 2Na), and cytidine triphosphate disodium (CTP. 2Na) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Adenosine diphosphate (ADP. 2Na) and cytidine monophosphate disodium (CMP. 2Na) were purchased from the Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI). Ethyl acetate for synthesis was purchased from Avantor Performance Materials India (Rankem brand). Milli-Q (Merck Millipore) type-I water had been used for all the experiments, unless otherwise mentioned. Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit (10 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO)) with Ultracel-10 regenerated cellulose membrane (Merck Millipore) was used for centrifugation filtration experiments. The pH values of aqueous buffer solutions were measured using a pH Tutor bench pH meter (Eutech Instruments). Micro pH electrode (EC-FG43904, Eutech Instruments) was used to measure pH of supernatants after centrifugation. mySPIN 12 Mini Centrifuge (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Centrifuge 5427 R (Eppendorf) were used for centrifugation experiments.

General sample preparation

The concentrations of stock solutions were calculated either by weighing or by UV-visible spectroscopy using their molar extinction coefficients. In water: ɛ280 = 43,824 M−1cm−1 for BSA; ɛ280 = 106,400 M−1cm−1 for ALP; ɛ260 = 15,400 M−1cm−1 for adenosine and its nucleotides; ɛ260 = 7500 M−1cm−1 for cytidine tri- and monophosphate; ɛ260 =11,700 M−1cm−1 for guanosine monophosphate; ɛ260 = 9900 M−1cm−1 for uridine monophosphate; ɛ456 = 46,000 M−1cm−1 (in 10 mM NaOH) for pyranine71. In acetonitrile: ɛ338 = 11,400 M−1cm−1 for NBD-Cl. The stocks of all proteins, surfactants, and nucleotides were stored in Type- I ultrapure water, whereas NBD-Cl in acetonitrile. The final composition of acetonitrile in the reaction mixture never exceeded more than 0.5% (v/v). All the experiments were done without removing the unreacted NBD-Cl from the reaction mixture.

FITC-tagging of BSA

The FITC- tagging of BSA was done by following the procedure used previously in our laboratory without any modification72. 1 mg/ml FITC in DMSO was added to 100 µl of BSA and kept for reaction at 4 °C for 6 hours. 50 mM of ammonium chloride was added to quench the reaction. After 2 hours, the tagged protein was purified through Sephadex G-25 gel filtration column using 5 mM HEPES pH 7 as the mobile phase. The degree of labeling (DOL) for each fraction was estimated using UV-vis spectroscopy.

UV-visible absorption spectroscopy

All the UV-visible spectra were recorded either in a non-treated flat-bottomed transparent polystyrene 96-well microplate (Tarsons Products Limited) using POLARstar Omega (BMG LABTECH GmbH) microplate reader in absorbance mode or in a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette using Varian Cary 60 (Agilent Technologies) spectrophotometer. The path length of a 200 μl reaction mixture in the microplate was estimated to be approximately 0.6 cm. The plates were set to shake at 100 rpm in double-orbital mode before each reading. Prior to analysis, for baseline correction, the spectrum of water was subtracted from the entire UV-visible absorption spectrum of each sample. In addition, for turbidity correction, the absorbance value at 600 nm of the same sample was subtracted from the complete sample spectrum.

Fluorescence spectroscopy with pyranine dye

For the estimation of pH of BSA droplets using pyranine dye Cary Eclipse (Agilent Technologies) fluorescence spectrometer was used. All the spectra were measured after incubating the samples for 1 hour at room temperature.

Confocal and widefield microscopy

The confocal imaging and FRAP experiments were carried out on ZEISS LSM 980 Elyra 7 super-resolution microscope with a 63× oil-immersion objective (NA 1.4) and Airyscan 2 detector equipped with 32 channels (GaAsP), using a high-resolution monochrome cooled AxioCamMRm Rev.3 FireWire(D) camera. An excitation laser of wavelength of 488 nm was used for imaging samples with pyranine and FITC-tagged proteins, with an emission filter of 519 nm. The images were analyzed using the software ZEN Blue 3.2. The fluorescence intensity analysis of confocal images of samples with pyranine was done using ImageJ software (Calibration plot given in Supplementary Fig. 8)73.

The brightfield and epifluorescence microscopy experiments were performed using the ZEISS Axis Observer 7 microscope with AxioCam 503 Mono 3 Megapixel with ZEN 3 software. An excitation wavelength of 475 nm was used for imaging FITC-tagged (λem = 519 nm) proteins. The widefield microscopy experiments were done using either a cover slip or using secure seal circular hybridization chambers (Grace Bio-Labs) with dimensions of 8–9 mm in diameter and 1 mm in fluid depth.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) measurements

A region of 1 µm (r = 0.5 µm) was selected for bleaching inside coacervate droplets, for which a 488 nm laser diode was used on FITC-tagged proteins. Fluorescence recovery curves were normalized, background-corrected, plotted and fitted using the Origin software. Dapp values were obtained by fitting the normalized FRAP data against the exponential equation with recovery function, f(t) = A (1−e−t/τ), which was used previously in the literature74. Here, τ is the recovery timescale, from which Dapp was calculated using the formula: Dapp ≈ r2/ τ.

Zeta potential (ζ) measurements

Zeta potential values were estimated using Horiba Zetasizer SZ100-V2 Nanoparticle Analyzer in a carbon-coated electrode. The zeta potential was calculated using the Smoluchowski equation: μ = 2ζε/3ηf(κr), [where ε = dielectric constant, η = viscosity, µ = electrophoretic mobility, f(κr) = Debye function, ζ = zeta potential]. The reported zeta potential values are the average of five measurements.

Circular Dichroism (CD) measurements

Chirascan spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics) was used to record far-UV CD spectra. The measurements were done in a quartz cuvette of 1 mm path length. The spectra were averaged over 2 scans, followed by blank subtraction.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker Avance-III 400 MHz spectrometer.

Procedure for the deconvolution of the UV-visible spectra of NBD-tagged proteins

Prior to the following steps, the entire spectrum of each sample was subtracted from the baseline spectrum of water and the absorbance value at 600 nm for the same sample for turbidity correction. For deconvoluting the complete spectrum of an NBD-tagged protein into its possible component spectral curves, a curve-fitting software (Fityk) was employed75. Using this software, a model curve (or simply “model”) was created as a sum of potential component curves (component functions), whose parameters, excluding the maximum height of the curve, were assigned manually. The terms “function”, “model”, and “function type” are used here in the same sense as defined in the software manual. The parameters for these functions were determined from the recorded UV-visible spectra of the synthesized model compounds for NBD-amine (NBD-octylamine), NBD-thiol (NBD-octanethiol), and NBD-phenol adducts (Supplementary Fig. 14a–e) and were fed into the software for fitting (Supplementary Fig. 14f). Based on the shapes of the curves of model spectra, they were treated as either “Gaussian” (symmetrical bell curve) or “Split-Gaussian” (asymmetrical) functions whose characteristics are also pre-defined in the software (Supplementary Fig. 14g, h). The parameters for individual functions such as the center of the curve (a1) and half-width at half maximum (HWHF) (a2 for Gaussian) were fixed. Note As mentioned earlier, the peak height (a0), which translates to the absorbance of the respective component species, was not fixed and was estimated after fitting. The model function was fitted, using the in-built Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, for multiple rounds of iteration until the model and experimental curves reached a good agreement and the process reached the lowest possible chi-squared (χ2) value (Supplementary Fig. 14f). The value of χ2 was not taken as a criterion for a good fitting since all the spectra attained a chi-squared value much lower than 1. However, a satisfactory R-squared (R2) value of more than 0.99 was reached for almost every fitting. The concentrations (c) of the component species in the protein were calculated according to Beer-Lambert’s law, by using appropriate molar extinction coefficient (ε) and path length (l) values (Supplementary Table 3).

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information and supplementary data files. Raw files of main manuscript Figs. 2c, d, 3b, d, 4b, c, d, 5a–f, 6c, d are provided in Supplementary Data 1. All the data are also available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Santos, A. L. & Lindner, A. B. Protein posttranslational modifications: Roles in aging and age-related disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 1–19 (2017).

Harmel, R. & Fiedler, D. Features and regulation of non-enzymatic post-translational modifications. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 244–252 (2018).

Jennings, E. Q., Fritz, K. S. & Galligan, J. J. Biochemical genesis of enzymatic and non-enzymatic post-translational modifications. Mol. Asp. Med. 86, 101053 (2022).

Xia, Y. et al. A cascade enzymatic reaction scheme for irreversible transpeptidative protein ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6838–6844 (2023).

Wang, Z. A. & Cole, P. A. The chemical biology of reversible lysine post-translational modifications. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 953–969 (2020).

Brimble, M. A., Ackermann, L., Li, Y.-M. & Raj, M. Chemoselective methods for labeling and modification of peptides and proteins. Org. Lett. 25, 6605–6606 (2023).

Spicer, C. D. & Davis, B. G. Selective chemical protein modification. Nat. Commun. 5, 4740 (2014).

Shadish, J. A. & DeForest, C. A. Site-selective protein modification: From functionalized proteins to functional biomaterials. Matter 2, 50–77 (2020).

Krall, N., da Cruz, F. P., Boutureira, O. & Bernardes, G. J. L. Site-selective protein-modification chemistry for basic biology and drug development. Nat. Chem. 8, 103–113 (2016).

Hackenberger, C. P. R. & Schwarzer, D. Chemoselective ligation and modification strategies for peptides and proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 10030–10074 (2008).

Hoyt, E. A., Cal, P. M. S. D., Oliveira, B. L. & Bernardes, G. J. L. Contemporary approaches to site-selective protein modification. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 147–171 (2019).

Reddy, N. C., Kumar, M., Molla, R. & Rai, V. Chemical methods for modification of proteins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 18, 4669–4691 (2020).

Rosen, C. B. & Francis, M. B. Targeting the N terminus for site-selective protein modification. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 697–705 (2017).

Keenan, T. et al. A tale of two bioconjugations: pH controlled divergent reactivity of protein α-oxo-aldehydes in competing α-oxo-mannich and catalyst-free aldol ligations. ACS Chem. Biol. 16, 2387–2400 (2021).

Song, W., Wang, Y., Qu, J., Madden, M. M. & Lin, Q. A photoinducible 1,3‐dipolar cycloaddition reaction for rapid, selective modification of tetrazole‐containing proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 2832–2835 (2008).

Metanis, N. & Hilvert, D. Harnessing selenocysteine reactivity for oxidative protein folding. Chem. Sci. 6, 322–325 (2015).

Chalker, J. M., Bernardes, G. J. L. & Davis, B. G. A “tag-and-modify” approach to site-selective protein modification. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 730–741 (2011).

Rose, D. A. et al. Self-immolative hydroxybenzylamine linkers for traceless protein modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6050–6058 (2022).

Tang, K. C., Maddox, S. M., Backus, K. M. & Raj, M. Tunable heteroaromatic azoline thioethers (HATs) for cysteine profiling. Chem. Sci. 13, 763–774 (2022).

Aboderin, A. A., Boedefeld, E. & Luisi, P. L. Reaction of chicken egg white lysozyme with 7-chloro-4-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 328, 20–30 (1973).

Aboderin, A. A. & Boedefeld, E. Reaction of chicken egg white lysozyme with 7-chloro-4-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole. II. Sites of modification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 420, 177–186 (1976).

Canfield, R. E. The amino acid sequence of egg white lysozyme. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 2698–2707 (1963).

Majorek, K. A. et al. Structural and immunologic characterization of bovine, horse, and rabbit serum albumins. Mol. Immunol. 52, 174–182 (2012).

Knouse, K. W. et al. Nature chose phosphates and chemists should too: How emerging P(V) methods can augment existing strategies. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 1473–1485 (2021).

Sorrenti, A. et al. Non-equilibrium steady states in supramolecular polymerization. Nat. Commun. 8, 15899 (2017).

Westheimer, F. H. Why nature chose phosphates. Science 235, 1173–1178 (1987).

Abdelouahdi, K., Bouaid, A., Barakat, A. & Solhy, A. Natural phosphates and their catalytic applications. Design and Applications of Hydroxyapatite‐Based Catalysts 481–531 https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527830190.ch14 (2022).

Mahato, R. R., Shandilya, E., Dasgupta, B. & Maiti, S. Dictating catalytic preference and activity of a nanoparticle by modulating its multivalent engagement. ACS Catal. 11, 8504–8509 (2021).

Mahato, R. R., Juneja, S. & Maiti, S. Benchmarking cationic monolayer protected nanoparticles and micelles for phosphate‐mediated and nucleotide‐selective proton transfer catalysis. Chem. Asian J. 18, e202300657 (2023).

Shandilya, E., Rallabandi, B. & Maiti, S. In situ enzymatic control of colloidal phoresis and catalysis through hydrolysis of ATP. Nat. Commun. 15, 3603 (2024).

Testa, A. et al. Sustained enzymatic activity and flow in crowded protein droplets. Nat. Commun. 12, 6293 (2021).

Nakashima, K. K., van Haren, M. H. I., André, A. A. M., Robu, I. & Spruijt, E. Active coacervate droplets are protocells that grow and resist Ostwald ripening. Nat. Commun. 12, 3819 (2021).

Barriales, K. et al. Localized and regulated peptide pigment formation inside liquid droplets through confined enzymatic oxidation. Chem. Commun. 59, 14138–14141 (2023).

Jain, A. et al. Connected peptide modules enable controlled co-existence of self-assembled fibers inside liquid condensates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15002–15007 (2022).

Priyanka, M. S. Co-assembly-mediated biosupramolecular catalysis: thermodynamic insights into nucleobase specific (oligo)nucleotide attachment and cleavage. J. Mater. Chem. B 11, 10383–10394 (2023).

Küffner, A. M. et al. Acceleration of an enzymatic reaction in liquid phase separated compartments based on intrinsically disordered protein domains. ChemSystemsChem 2, e2000001 (2020).

Davis, B. W. et al. Colocalization and sequential enzyme activity in aqueous biphasic systems: Experiments and modeling. Biophys. J. 109, 2182–2194 (2015).

Wei, Y., Cheng, G., Ho, H.-P., Ho, Y.-P. & Yong, K.-T. Thermodynamic perspectives on liquid–liquid droplet reactors for biochemical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6555–6567 (2020).

Fraccia, T. P. & Martin, N. Non-enzymatic oligonucleotide ligation in coacervate protocells sustains compartment-content coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 2606 (2023).

Gnanamani, E., Yan, X. & Zare, R. N. Chemoselective N‐alkylation of indoles in aqueous microdroplets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 3069–3072 (2020).

Wang, J., Abbas, M., Wang, J. & Spruijt, E. Selective amide bond formation in redox-active coacervate protocells. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–11 (2023).

Smokers, I. B. A., van Haren, M. H. I., Lu, T. & Spruijt, E. Complex coacervation and compartmentalized conversion of prebiotically relevant metabolites. ChemSystemsChem 4, e202200004 (2022).

Donau, C. et al. Active coacervate droplets as a model for membraneless organelles and protocells. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Alfano, C. et al. Molecular Crowding: The History and Development of a Scientific Paradigm. Chem. Rev. 124, 3186–3219 (2024).

Cao, S. et al. Dipeptide coacervates as artificial membraneless organelles for bioorthogonal catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–14 (2024).

Yin, C., Lin, Z., Jiang, X., Martin, N. & Tian, L. Engineering the coacervate microdroplet interface via polyelectrolyte and surfactant complexation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 27447–27456 (2023).

Ivanov, I. et al. Directed growth of biomimetic microcompartments. Adv. Biosyst. 3, 1800314 (2019).

Jahnke, K., Grubmüller, H., Igaev, M. & Göpfrich, K. Choice of fluorophore affects dynamic DNA nanostructures. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 4186–4195 (2021).

Nandi, R. & Amdursky, N. The dual use of the pyranine (HPTS) fluorescent probe: A ground-state pH indicator and an excited-state proton transfer probe. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2728–2739 (2022).

Giosa, L., Zadek, F. & Langer, T. The buffer power of blood: a reappraisal of its mathematical expressions with implications on the role of albumin as a buffer. J. Appl. Physiol. 135, 196–199 (2023).

Birkett, D. J., Price, N. C., Radda, G. K. & Salmon, A. G. The reactivity of SH groups with a fluorogenic reagent. FEBS Lett. 6, 346–348 (1970).

Kenner, R. A. & Aboderin, A. A. New fluorescent probe for protein and nucleoprotein conformation. Binding of 7-(p-methoxybenzylamino)-4-nitrobenzoxadiazole to bovine trypsinogen and bacterial ribosomes. Biochemistry 10, 4433–4440 (1971).

Glasgow, B. J. & Abduragimov, A. R. Methods toward simplification of time resolved fluorescence anisotropy in proteins labeled with NBD (4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan) adducts. MethodsX 6, 998–1008 (2019).

Jiang, C. et al. NBD-based synthetic probes for sensing small molecules and proteins: design, sensing mechanisms and biological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 7436–7495 (2021).

Ferguson, S. J., Lloyd, W. J. & Radda, G. K. The mitochondrial ATPase: Selective modification of a nitrogen residue in the β subunit. Eur. J. Biochem. 54, 127–133 (1975).

Roustan, C., Fattoum, A. & Pradel, L.-A. Spatial proximity of a tyrosyl and a lysyl residue in the active site region of yeast 3-phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochimie 61, 663–669 (1979).

Westheimer, F. H. & Schmidt, D. E. Jr pK of the lysine amino group at the active site of acetoacetate decarboxylase. Biochemistry 10, 1249–1253 (1971).

Westheimer, F. H. Coincidences, decarboxylation, and electrostatic effects. Tetrahedron 51, 3–20 (1995).

Giger, L. et al. Evolution of a designed retro-aldolase leads to complete active site remodeling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 494–498 (2013).

Ottelé, J., Hussain, A. S., Mayer, C. & Otto, S. Chance emergence of catalytic activity and promiscuity in a self-replicator. Nat. Catal. 3, 547–553 (2020).

Detmers, P., Weber, A., Elzinga, M. & Stephens, R. E. 7-Chloro-4-nitrobenzeno-2-oxa-1,3-diazole actin as a probe for actin polymerization. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 99–105 (1981).

Küchler, A., Yoshimoto, M., Luginbühl, S., Mavelli, F. & Walde, P. Enzymatic reactions in confined environments. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 409–420 (2016).

Mayr, C. et al. Frontiers in biomolecular condensate research. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 512–514 (2023).

Weißenfels, M., Gemen, J. & Klajn, R. Dissipative self-assembly: Fueling with chemicals versus light. Chem 7, 23–37 (2021).

Ragazzon, G. & Prins, L. J. Energy consumption in chemical fuel-driven self-assembly. Nat. Nanotech 13, 882–889 (2018).

Sharma, C., Maity, I. & Walther, A. pH-feedback systems to program autonomous self-assembly and material lifecycles. Chem. Commun. 59, 1125–1144 (2023).

Mishra, A., Dhiman, S. & George, S. J. ATP‐driven synthetic supramolecular assemblies: From ATP as a template to fuel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2740–2756 (2021).

Dhiman, S., Jain, A., Kumar, M. & George, S. J. Adenosine-phosphate-fueled, temporally programmed supramolecular polymers with multiple transient states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16568–16575 (2017).

Koga, S., Williams, D. S., Perriman, A. W. & Mann, S. Peptide–nucleotide microdroplets as a step towards a membrane-free protocell model. Nat. Chem. 3, 720–724 (2011).

Ahmad, A. et al. Facile preparation of hexagonal nanosheets via polyion complex formation from α-helical polypeptides and polyphosphate-based molecules. Chem. Commun. 59, 1657–1660 (2023).

Taniguchi, M. & Lindsey, J. S. Database of absorption and fluorescence spectra of >300 common compounds for use in PhotochemCAD. Photochem. Photobiol. 94, 290–327 (2018).

Aastha, Priyanka & Maiti, S. Simultaneous quantification of serum albumin and gamma globulin using Zn(ii)-metallosurfactant via a coffee ring pattern. Chem. Commun. 59, 6536–6539 (2023).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Elbaum-Garfinkle, S. et al. The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7189–7194 (2015).

Wojdyr, M. Fityk: a general-purpose peak fitting program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 1126–1128 (2010).

Acknowledgements

S.M. acknowledges the financial support of the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) (File No. CRG/2022/002345). NKE acknowledges CSIR, India (09/0947(12588)/2021-EMR-I). PP and RRM acknowledge IISER Mohali for the doctoral research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K.E. performed most of the experiments including data analysis, Priyanka did the microscopic and centrifugation studies, R.R.M. synthesized and characterized the model compounds. S.M. conceived the idea, wrote the manuscript and all authors commented on it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Dibyendu Das and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this wor k. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ettikkan, N.K., Priyanka, P., Mahato, R.R. et al. Nucleotide-mediated modulation of chemoselective protein functionalization in a liquid-like condensed phase. Commun Chem 7, 242 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01333-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01333-w