Abstract

Generative models have revolutionized de novo drug design, allowing to produce molecules on-demand with desired physicochemical and pharmacological properties. String based molecular representations, such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) and SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings), have played a pivotal role in the success of generative approaches, thanks to their capacity to encode atom- and bond- information and ease-of-generation. However, such ‘atom-level’ string representations could have certain limitations, in terms of capturing information on chirality, and synthetic accessibility of the corresponding designs.

In this paper, we present fragSMILES, a novel fragment-based molecular representation in the form of string. fragSMILES encode fragments in a ‘chemically-meaningful’ way via a novel graph-reduction approach, allowing to obtain an efficient, interpretable, and expressive molecular representation, which also avoids fragment redundancy. fragSMILES contributes to the field of fragment-based representation, by reporting fragments and their ‘breaking’ bonds independently. Moreover, fragSMILES also embeds information of molecular chirality, thereby overcoming known limitations of existing string notations. When compared with SMILES, SELFIES and t-SMILES for de novo design, the fragSMILES notation showed its promise in generating molecules with desirable biochemical and scaffolds properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular representations based on strings are getting increasing attention in the molecular machine learning community, especially in combination with the so-called ‘chemical language models’ (CLMs), e.g., for de novo molecule design1,2,3 and synthesis planning4,5. The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES)6 notation is the most well-established of such notations. By traversing the two-dimensional graph of a molecule, a SMILES string encodes atoms and bond information using predefined characters (Fig. 1a)7. Thanks to the increasing success of chemical language modeling8,9, several alternatives have been proposed to overcome some of the limitations of SMILES10, e.g., the Self-referencing Embedded Strings11 (SELFIES), which enforce the generation of molecular strings corresponding to valid molecules. While these string notations have successfully led to experimentally-validated de novo designs12,13,14, they are not devoid of limitations. In particular, due to the ‘linearization’ of molecular graph information, fragments are not univocally represented in ‘atom-level’ strings like SMILES, and information on atomic neighborhoods can be distributed in different parts of the string (Fig. 1b). Moreover, de novo designs based on ‘atom-level’ string representations like SMILES might be affected by a limited synthetic accessibility15,16.

A complementary solution for storing and processing molecular information is constituted by representing molecules as a collection of fragments17,18,19,20,21, via fragmentation algorithms like BRICS20,22. Several fragment-based de novo design approaches have been proposed, which can constrain the generation of new molecules that are easier to synthesize16. Several works have focused on how to develop molecular strings at the level of molecular fragments, e.g., t-SMILES23, aimed to reduce the number of invalid sequences, although different sequences can be used to describe a given fragment.

Noteworthy, the strategy to encode fragments as stand-alone words has been documented in the literature, e.g., SMILES Pair Encoding (SPE)24 or Group SELFIES25. Such a shift from atom- to fragment-based notation in chemical language modeling resembles the character- to word-level26 shift in natural language processing (NLP), and it has the potential to yield more efficient and expressive representations27,28. However, current fragment-based approaches have several limitations, e.g. they can generate redundant structural motifs by annotating parts of identical substructures as they were different fragments. This might yield inefficient representation learning, since the same chemical information is annotated inconsistently29,30,31. Other works have used sets of fragments for de novo design. A notable example is SAFE32, which obtains an unordered sequence of interconnected fragment blocks.

To overcome these gaps in molecular representation field, here we propose fragSMILES, a novel ‘chemical-word’-level molecular string notation. Our representation is based on graph reduction, i.e., the simplification of molecular graphs by collapsing selected atoms and bonds into single fragments, thereby reducing the complexity of the graph while retaining key structural and functional information19,33. The reduced graph is then converted into a string-based notation, which we named fragSMILES.

Based on an interpretable tokenization technique, our ‘chemical word’-level representation allows to easily identify building blocks. This allows (a) each fragment to be univocally encoded, irrespective of its molecular neighborhoods, (b) achieving a richer ‘fragment semantics’, while simplifying how fragment linkers are encoded, and (c) obtaining shorter sequences for chemical language modeling, that still preserve key chemical information. In what follows, after introducing the theory of fragSMILES, we show that this new notation advances the state of the art thanks to a better specification of molecular chirality, along with a good capacity to explore the chemical space when combined with de novo design algorithms, e.g., to achieve desirable physico/biochemical properties, synthesizability and scaffold novelty. Additionally, fragSMILES can improve many drug discovery related tasks34 in a broader sense, such as database storing35, chemical reaction predictions36 and bioactivity prediction37.

Results and discussions

Representing molecules as fragSMILES

The fragSMILES notation is generated via molecular graph reduction (Fig. 2a). In particular, the conversion of molecular graphs to fragSMILES consists of three phases (a):

-

1.

Disassembling. This phase ‘breaks’ a given molecule according to customizable set of cleavage rules. Breaking bonds are constituted by either (a) exocyclic single bonds, except for bonds between oppositely charged atoms (e.g., nitro groups), or (b) user-customizable rules, including for example rotatable bonds. In our approach, molecular fragments were obtained by cleaving all the exocyclic single bonds but other user-defined fragmentation rules could also be set (e.g., BRICS)20,22.

-

2.

This phase leads to a set of unique fragments. Each unique fragment is also annotated with indexes to track the ‘breaking’ bonds.

-

3.

Graph reduction. This phase condenses molecular fragments and the ‘breaking’ bonds into the respective nodes and edges of a reduced molecular graph. Bidirected edges specify the correct fragment combination (i.e., by identifying which atoms belong to the ‘breaking’ bonds).

-

4.

Conversion into fragSMILES. The reduced molecular graph is then converted into string notation, where, for interpretability, the SMILES alphabet is used to identify fragment-level nodes.

The ‘syntactic’ rules of the obtained fragSMILES are the following:

-

The nodes representing the fragments are expressed as canonical SMILES, to preserve interpretability of the corresponding chemical information.

-

The edges are provided with numerical indexes, with the notation “< index >” to indicate the connecting atoms between neighboring fragments. In the case of fragments including only a single linking atom (i.e., a single atom having replaceable hydrogen atoms), the numerical index is not shown.

-

Branches are described in parentheses. Before and after the opening parenthesis, numerical indexes indicate how the branches are connected to the fragments.

-

The configuration of chiral centers (Fig. 2b) is indicated as suffix tag to the indices in the case of connector atoms (e.g., <2 R > C1CCOC1 < 4S> to represent the tetrahydrofuran with two given connector carbon atoms in R and S absolute configurations) or as special suffix in the case of non-connector atoms (e.g., C1CC2CNC2CN1 | 2R5S to represent the 3,8-diazabicyclo[4.2.0]octane with the two bridgehead carbon atoms in R and S absolute configurations). The stereochemical configuration of fragments having unspecified connector atoms is also reported as suffix (e.g., C | R to represent the carbon in R absolute configuration).

Like SMILES strings, any molecule can be represented as multiple fragSMILES (depending on the starting point to traverse the reduced graph). This aspect can be leveraged for data augmentation. Alternatively, fragSMILES can be also canonicalized, via graph traversal and fragment prioritization rules (see Materials and Methods). Moreover, Fig. 2b shows that, irrespective of the graph traversal order, in fragSMILES the chiral centers are consistently annotated, unlike in the case of SMILES.

Effect of fragmentation and tokenization rules

Several tokenization techniques can be employed to split molecular portions, textually represented, into computer-manageable ‘units’ (tokens)24,38. fragSMILES notation separates molecular fragments, their connector indices and branching brackets, and considers them as tokens.

We compared the effect of two fragmentation rules for fragSMILES, based on the cleavage of: (a) all the exocyclic single bonds17, and of (b) all the rotatable bonds39. To this end, we used ZINC-250K40 database, which contains 249,414 molecules. Cleaving all exocyclic single bonds generated a more compact vocabulary of token types (5869 vs 13,035), thus mitigating the risk of redundancy29,30,31 (Table 1). Moreover, such fragmentation rule awards the occurrence of ‘generic’ (e.g., amino group, carbon atoms, and phenyls) instead of specific tokens (e.g., aniline and the toluene). An example of different fragmentation rules for a generic molecular structure is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

As a result, the fragmentation based on exocyclic single bonds constitutes a good trade-off between (a) the number of tokens necessary to represent a molecule, and (b) the number of token types. Hence, fragSMILES works as syllable-level language, which is capable of better performances41 and lower complexity42.

For completeness, we implemented in the t-SMILES23 a word-level tokenization, where tokens encode fragments. By comparing the vocabulary size and the number of tokens for t-SMILES word-level, fragSMILES rotatable bonds and fragSMILES exocyclic single bonds, we noticed that t-SMILES, due to its sequence lengths, was unsuitable for fragment tokenization although its vocabulary was larger than ~12 K (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Based on these observations, the default fragmentation strategy for fragSMILES uses exocyclic single bonds.

Compact encoding of molecular information via fragSMILES

The fragSMILES approach allows to encode molecules with a smaller number of elements (‘tokens’43) than SMILES and SELFIES strings given that its tokenization is based on fragments descending from reduced molecular graph. Notably, other tokenization techniques could return shorter sequences24 and whose structure is not always related to any particular molecular fragment (e.g., Byte Pair Encoding)38.

When analyzed on ZINC-250K40 database, fragSMILES returned an average length of 17 tokens (Fig. 3), remarkably smaller than the length of Group-SELFIES25, SELFIES11 and SMILES (which have an average of 30, 37 and 44 tokens, respectively). Representations with fewer tokens in combination with deep learning have the potential advantage to reduce computational complexity and memory usage44.

Token number distribution of fragSMILES, Group SELFIES, SELFIES and SMILES, computed on ZINC-250K molecules. The boxplot represents the length distribution of fragSMILES (whiskers indicate 1st and 3rd quartiles, median, the central line and the cross indicate the median and mean values, respectively, and circles indicate the outliers).

Noteworthy, the top occurring tokens are those made by the single carbon atom fragment, irrespective if it is a terminal methyl or a polysubstitued carbon, and connectivity tags as <0> or <3 > . Rare tokens are instead made by cyclic fragments provided with unambiguous chirality and occurring in very few molecular structures. The high frequency of fragments such as single carbon or nitrogen atoms demonstrates that fragSMILES captures mainly the occurrence of non-redundant tokens. For instance, aniline and toluene are represented by two different structural tokens. They are the amino group and the aromatic ring for the aniline and the carbon atom and the aromatic ring for the toluene (Supplementary Fig. 3).

De novo molecule design with fragSMILES

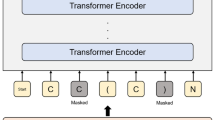

We benchmarked fragSMILES for de novo molecule design in comparison with SMILES, SELFIES and t-SMILES. To this end, we employed Recurring Neural Networks (RNNs)45 with Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) cells46, as implemented in the MOSES benchmarking platform47. While many architectures for de novo design exist, LSTMs have been widely adopted in this field and extensively validated in the wet-lab3,12,48,49,50. The MOSES platform was chosen as it provides a curated dataset, predefined metrics, and a ready-to-use LSTM model for benchmarking on de novo drug design purposes.

Models were trained on the MOSES dataset (approximately 1.9 M molecules) using a five-fold cross validation and on each of the representations separately.

The trained models were used to sample 6000 molecules for each representation (i.e., fragSMILES, SELFIES, SMILES, and t-SMILES), for each cross-validation fold, obtaining 30,000 in total for each representation. For each set of generated strings, we computed (a) validity, capturing the number of ‘chemically valid’ molecules generated from each representation (b) uniqueness, capturing the number of non-duplicated molecules, and (c) novelty, quantifying the number of de novo designs that were not present in the training set (Table 2). Detailed explanations about the metrics are reported in the Materials and Methods. In this context, fragSMILES strings showed an intermediate behavior between SELFIES and t-SMILES (best) vs SMILES (worst). SELFIES showed consistently better values of validity and uniqueness as t-SMILES, while the latter showed best novelty value, and fragSMILES reached statistically significant better than SMILES strings for validity and uniqueness (Table 2). Validity was computed on the initial 6000 generated samples, while uniqueness and novelty were computed on the number of valid, and valid and unique molecules, respectively.

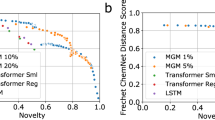

To further investigate the quality of the generated de novo designs, we sampled an additional set of 6000 (per 5-fold of the cross-validation) novel molecules for each representation. We computed an array of metrics to quantify the similarity of the designs to the known molecules. In particular, we computed (Table 2):

-

Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD)51, which captures the differences of biological and chemical properties between de novo designs and a reference set of molecules (test set molecules here, Table 2). The lower the FCD, the more similar two sets are.

-

Physicochemical properties, i.e., lipophilicity (logP)52, Synthetic Accessibility (SA)53, Quantitative Estimation of Drug-likeness (QED)54,55 and molecular weight (MW). The differences of these properties between de novo designs and training set molecules were reported as Wasserstein-1 distance56 (the lower, the more similar the two sets).

In this context, fragSMILES showed consistently superior performance across all the analyzed metrics, with statistically significant improvements in two out of five cases with SMILES, four out of five cases with SELFIES and four out of five cases with t-SMILES (Table 2). These results suggest that fragSMILES are an ideal trade-off between chemical space exploration (validity, uniqueness, novelty) and the identification of designs with desirable properties (i.e., similar to the training set molecules).

Considering that the training set contains drug-like molecules, fragSMILES generated new molecules with a desirable property profile in terms of logP, QED, and MW. A similar consideration can be extended to the SA values. For the sake of comparison, results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5.

Chemical space exploration with fragSMILES

In what follows, we focus our de novo design efforts using a training set of 270,408 bioactive molecules57 (for Kd/KI/IC50/EC50 < 1 μM) from ChEMBL58 v22. Unlike the previously used MOSES molecules, this set contains stereochemistry information, and is aimed at a specific task, namely, generating drug-like molecules. This test was used to elucidate various properties of fragSMILES: (a) the effect of string augmentation on the quality of de novo designs, (b) the representation capability to capture chirality, and (c) the potential to explore novel molecular scaffolds. These aspects are discussed below. Supplementary Fig. 6 shows how alternative representations of fragSMILES are obtained for the same molecule.

fragSMILES augmentation

‘Atom-level’ representations like SMILES and SELFIES are non-univocal, since they can be obtained starting from any non-hydrogen atom, and by reading the graph in different directions. As a result, a molecule can be represented by multiple valid strings for training purposes: such ‘data augmentation’ can improve the quality of molecules produces via chemical language modeling59,60,61. The new fragSMILES notation can also be augmented: since any node of the reduced graph can be the starting point for traversal, multiple fragSMILES can be obtained from the same molecule. This property allows to perform data augmentation, as for SMILES and SELFIES. Furthermore, the reduced graph allows to explicitly account for the chiral centers of stereoisomers. In this respect, the corresponding fragSMILES reports the absolute configurations, tokenized as R and S, respectively. Thus, the chiral centers in fragSMILES are univocally assigned, irrespective of the order of their substituents in the string notation. Unlike SMILES62, this makes fragSMILES tokens univocal and invariant to graph traversal order once the chiral centers have been defined.

On the selected molecular set, RNN models were trained for each string notation (SMILES, SELFIES, t-SMILES and fragSMILES notations), and on their single- (canonical representation) and five-fold augmented versions. 61,870 fragSMILES representations were not augmentable until to five-folds, because they were composed of fully linear graphs. As far as fragSMILES is concerned, we calculated an average of 10 alternative representations as maximum number per molecule of the Zinc250K dataset. Our results align with what observed for SMILES strings, where augmentations larger than 10 do not lead to remarkable improvements in the model quality8,60,63.

Five-fold cross validation was carried out, and each fold was used to generate 6000 strings to compute validity, uniqueness and novelty (Table 3). The (bio)chemical properties previously discussed (Table 2) were also evaluated, using a pool of 6000 novel designs per each fold (Table 3).

In agreement with existing literature59,63,64, the augmentation improved the quality of de novo designs for SMILES and SELFIES in terms of novelty, uniqueness and validity. This is also visible on fragSMILES (Table 3). The same trend in performance was observed (i.e., SELFIES and t-SMILES yielding the best values of validity, uniqueness, and novelty), with fragSMILES de novo designs being the most similar to the reference molecules in terms of chemical and biological properties (FCD in Table 3). In most cases, string augmentation led to a small decrease in (bio)chemical similarity to the reference set (Supplementary Figs. 7-9).

Capturing chirality with fragSMILES

The previously generated 6000 strings for each fold were used to analyze the capacity of each representation to capture chirality. In particular, for each of the representations, the 6000 strings were filtered to a subset containing tokens referring to chirality information (i.e., 1770 ± 70 for SMILES × 1 and 1800 ± 200 for SMILES × 5, 1820 ± 40 for SELFIES × 1 and 1900 ± 100 for SELFIES × 5, 1840 ± 90 for t-SMILES × 1 and 1900 ± 100 for t-SMILES × 5, 1770 ± 90 for fragSMILES × 1 and 2000 ± 100 for fragSMILES × 5). Each of these strings was then converted into a molecule (if possible), and the number of (in)valid, unique and novel molecules was quantified.

It is important to note that the conversion of fragSMILES into a valid molecule can only happen when chiral fragments (tokens) preserve their stereocenters (i.e., they have four different substituents). Several SMILES, SELFIES and t-SMILES strings can contain errors as they report achiral carbon atoms as chiral (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 10), which become syntactically valid only after sanitization and canonization with RDKit65.

In this context, fragSMILES produce a significantly higher number of molecules with unambiguously annotated and correct chirality (Table 3), thereby advancing upon known limitations of existing molecular strings (Supplementary Fig. 11)62,66.

Exploration of novel scaffolds with fragSMILES

Finally, we performed a scaffold analysis on the 6000 novel molecules previously generated per fold. In particular, Bemis-Murcko scaffolds67 were computed to identify the number of unique and novel scaffolds (Table 4).

In this context, SELFIES outperformed both SMILES, t-SMILES and fragSMILES. In their non-augmented version, SMILES and fragSMILES show comparable performance of scaffold uniqueness (no statistical difference achieved) unlike t-SMILES that performed worse. When five-fold augmentation is performed, SMILES outperforms fragSMILES, with a 3% higher scaffold novelty. t-SMILES achieved the same trend as the non-augmented version.

To further elucidate the characteristics of the novel scaffolds, we computed the total number of novel scaffolds containing new fragments compared to the training set molecules (reported as “No. novel fragments” and computed based on fragSMILES fragments, in Table 4).

SMILES, SELFIES and t-SMILES can generate a higher number of new scaffolds compared to fragSMILES. However, many of these scaffolds are new primarily because they include cyclic fragments that were not present in the training set. This behavior is likely due to their character-level tokenization68, which allows a very high number of possible combinations, independently on the chemical relevance. Noteworthy, fragSMILES can also generate new cyclic systems and promote scaffold novelty (Supplementary Table 1) if an atom-level tokenization is set. On the other hand, fragSMILES on word-level tokenization is more effective at capturing the scaffolds present in the training set and generating genuinely novel cores by recombining different cyclic elements. This ability to create novel cores through recombination bears potential for de novo molecule design, as it ensures that the generated molecules are more likely to possess desired chemical properties, to be chemically stable and synthetically feasible.

Conclusions

This work introduced fragSMILES, a novel ‘chemical-word’-level notation for molecules. Unlike previous fragment-based representations, fragSMILES possesses desirable qualities, i.e., it (a) reports fragments and their ‘breaking’ bonds independently, (b) allows canonical encoding of fragments without redundancy, and (c) strikes an ideal balance between sequence length and vocabulary size. Our systematic analysis shows that fragSMILES possess desirable properties for de novo design and a good capacity to explore the chemical space while preserving desirable physico- and bio-chemical properties. Importantly, the fragSMILES notation excels in capturing molecular chirality, a critical aspect often overlooked by traditional string-based representations62.

Thanks to its ‘chemical-word’-level character and expressive representation of chemical information, we expect the fragSMILES notation to advance current capabilities of chemical language modeling, not only for de novo molecule design. Specifically, it could improve but reaction properties or molecule properties69,70, synthesis planning15, prediction of challenging bioactivity prediction tasks, e.g., fields involving activity cliffs37 and chiral activity cliffs71, due to fragSMILES improved detection of chirality. Moreover, its textual representation could help database storing35 and fragment-based molecule searching, avoiding substructure searching by employing the use of slower graph-based algorithms.

By setting word-level or atom-level tokenization rules, fragSMILES can be employed to effectively explore uncharted regions of the chemical space. The applicability of fragSMILES can be further extended to new tasks in the molecular sciences, e.g., by incorporating additional fragmentation rules or incorporating additional chemical information relative to the fragments. Finally, we expect the development of neural network architectures tailored to word-level processing to further propel the potential of fragment-based notations for generative artificial intelligence in chemistry.

Methods

Graph reduction procedure for fragSMILES

After interpreting atom-based molecular graphs as RDKit (v. 2023.9.5)65 ‘Mol’ objects, fragSMILES are obtained with the following procedure:

-

1.

Cleavage bond definition. Cleavage bonds pattern can be defined and customized via SMARTS72 notation.

-

2.

Molecule fragmentation. Based on the defined cleavage bonds, molecules are divided into fragments. In this work, this was performed via the ‘Chem.FragmentOnBonds’ function of RDKit.

-

3.

Conversion into a reduced graph. All information on obtained fragments (nodes) and cleavage bonds (edges) are converted into a bidirectional graph. In this work, this was handled via NetworkX73 package (v. 3.2.1) and interpreted as a bidirectional graph carrying all attributes for nodes and edges.

fragSMILES canonicalization

The canonicalization of the reduced graph is achieved via the following steps:

-

1.

longest paths are recognized;

-

2.

paths that branch out earlier along the way are retained;

-

3.

paths with more numerous branching are retained;

-

4.

Equal paths are compared by the sequence of their component nodes. Each node, depending on the fragment it represents, is identified by a unique numeric ID that places it in a ranking. The path with the most importance is considered.

All codes for tool employing are written as Python language and available on GitHub link https://github.com/f48r1/chemicalgof or Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12700298.

Data sources and preprocessing

The following datasets and preprocessing steps were used:

-

ZINC-250K database40 was obtained from repository of a recent work25. It contained 249,414 molecules but some of them were discarded because they contained only one fragment according to the fragmentation framework. Specifically, 86 and 864 molecules were discarded when the exocyclic single bond rule and rotatable bond rule were applied, respectively.

-

MOSES dataset47 consisted of 1,936,962 molecules whose SMILES data were converted to SELFIES and fragSMILES representations. 269 molecules were discarded because they were composed of a single cyclic fragment.

-

The bioactive ChEMBL subset was obtained by a recent work57. It contained around 650 K structures from ChEMBL v. 22 having Kd/KI/IC50/EC50 < 1 μM.

For ZINC and the bioactive ChEMBL molecules, isotope information was removed, and salts charges were neutralized keeping the heavier organic part. Geometric stereochemical information at the double bond (“/” and “\” characters) were removed but retaining optical stereochemical (“@” and “@@” characters) one. Finally, SMILES were canonized, and duplicates were removed. For ChEMBL, only molecules containing 10 to 32 fragSMILES tokens were retained, obtaining 270,408 molecules. MOSES dataset was not preprocessed further. All datasets used in this work listed molecules as SMILES strings, which were used to obtain canonical SELFIES and fragSMILES notations.

Model training and hyperparameter optimization

The RNN architectures used in this work were taken from the MOSES47 benchmarking platform. Default settings for parameterization do not provide a customizable embedding size. Therefore, we extended a customizable setting of embedding size for RNN model trained on fragSMILES representations, useful for word-level NLP26. Sampling was performed via softmax function with a temperature of T = 1.

For each representation, each cross-validation fold and each level of augmentation, the following hyperparameters were optimized: number of hidden layers (2, 3), number of hidden units per layer (256, 512), batch size (256, 512). Adam optimizer and a learning rate of 0.001 were used. Cross-validation loss was used for model optimization, in combination with early stopping at loss convergency. The details of the optimized hyperparameters can be found in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

The values of the evaluation metrics shown in the main text refer to models adopting hyperparameters that maximized novelty metric for SMILES notation at the sampling phase. Notably, the trend of performance as the hyperparameters changed was also observed by the other notations.

Evaluation metrics

For each model, strings were sampled at the early-stopping epoch. All generated strings were converted into canonical SMILES to assess their validity, uniqueness and novelty. In particular, validity was calculated on the total number of sampled SMILES strings that could be converted to chemically-valid molecules (by RDKit ‘Chem.MolFromSmiles’). Uniqueness was calculated on the valid (canonical) SMILES that were not duplicated. Novelty was calculated on the unique canonical SMILES that were not already included in the training set.

All other metrics were calculated by using software available in MOSES. Molecular scaffolds were computed via the RDKit (v. 2023.9.5) ‘Chem.Scaffolds.MurckoScaffold’ module of RDKit package.

For the sake of completeness, all the results of the metrics provided by MOSES are reported as Supplementary Data 1.

Data availability

The data employed to conduct our analysis are available on GitHub, at the following URL https://github.com/f48r1/fragsmiles.

Code availability

The code for graph reduction and obtaining fragSMILES is available in Python language on GitHub, at the following URL: https://github.com/f48r1/chemicalgof, and on Zenodo at the following https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12700298. All code to reproduce our analysis and processing steps can be found on GitHub, at the following https://github.com/f48r1/fragsmiles.

References

Grisoni, F. Chemical language models for de novo drug design: Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 79, 102527 (2023).

Alberga, D. et al. De novo drug design of targeted chemical libraries based on artificial intelligence and pair-based multiobjective optimization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 4582–4593 (2020).

Segler, M. H. S., Kogej, T., Tyrchan, C. & Waller, M. P. Generating focused molecule libraries for drug discovery with recurrent neural networks. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 120–131 (2018).

Schwaller, P. et al. Molecular transformer: a model for uncertainty-calibrated chemical reaction prediction. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1572–1583 (2019).

Öztürk, H., Özgür, A., Schwaller, P., Laino, T. & Ozkirimli, E. Exploring chemical space using natural language processing methodologies for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 25, 689–705 (2020).

Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 28, 31–36 (1988).

Weininger, D., Weininger, A. & Weininger, J. L. SMILES. 2. Algorithm for generation of unique SMILES notation. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 29, 97–101 (1989).

Skinnider, M. A., Stacey, R. G., Wishart, D. S. & Foster, L. J. Chemical language models enable navigation in sparsely populated chemical space. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 759–770 (2021).

Özçelik, R. et al. Chemical language modeling with structured state space sequence models. Nat. Commun. 15, 6176 (2024).

O’Boyle, N. & Dalke, A. DeepSMILES: an adaptation of SMILES for use in machine-learning of chemical structures. (2018).

Krenn, M. et al. SELFIES and the future of molecular string representations. Patterns 3, 100588 (2022).

Merk, D., Friedrich, L., Grisoni, F. & Schneider, G. De novo design of bioactive small molecules by artificial intelligence. Mol. Inform. 37, 1700153 (2018).

Li, X., Xu, Y., Yao, H. & Lin, K. Chemical space exploration based on recurrent neural networks: applications in discovering kinase inhibitors. J. Cheminformatics 12, 1–13 (2020).

Moret, M. et al. Leveraging molecular structure and bioactivity with chemical language models for de novo drug design. Nat. Commun. 14, 114 (2023).

Gao, W. & Coley, C. W. The synthesizability of molecules proposed by generative models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 5714–5723 (2020).

Seo, S., Lim, J. & Kim, W. Y. Molecular generative model via retrosynthetically prepared chemical building block assembly. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206674 (2023).

Jinsong, S., Qifeng, J., Xing, C., Hao, Y. & Wang, L. Molecular fragmentation as a crucial step in the AI-based drug development pathway. Commun. Chem. 7, 20 (2024).

Ivanov, N. N., Shulga, D. A. & Palyulin, V. A. Decomposition of small molecules for fragment-based drug design. Biophysica 3, 362–372 (2023).

Pogány, P., Arad, N., Genway, S. & Pickett, S. D. De novo molecule design by translating from reduced graphs to SMILES. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 1136–1146 (2019).

Podda, M., Bacciu, D. & Micheli, A. A deep generative model for fragment-based molecule generation. International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics (2020).

Kong, Y. et al. Integrating concept of pharmacophore with graph neural networks for chemical property prediction and interpretation. J. Cheminformatics 14, 52 (2022).

Taleongpong, P. & Brooks P. Improving Fragment-Based Deep Molecular Generative Models. in ICML’24 Workshop ML for Life and Material Science: From Theory to Industry Applications (2024).

Wu, J.-N. et al. t-SMILES: a fragment-based molecular representation framework for de novo ligand design. Nat. Commun. 15, 4993 (2024).

Li, X. & Fourches, D. SMILES pair encoding: a data-driven substructure tokenization algorithm for deep learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 1560–1569 (2021).

Cheng, A. H. et al. Group SELFIES: a robust fragment-based molecular string representation. Digit. Discov. 2, 748–758 (2023).

Asudani, D. S., Nagwani, N. K. & Singh, P. Impact of word embedding models on text analytics in deep learning environment: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 10345–10425 (2023).

Khurana, D., Koli, A., Khatter, K. & Singh, S. Natural language processing: state of the art, current trends and challenges. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 3713–3744 (2023).

Chuang, K. V., Gunsalus, L. M. & Keiser, M. J. Learning molecular representations for medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 63, 8705–8722 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Scientific Large Language Models: A Survey on Biological & Chemical Domains. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.14656 (2024).

Chen, J.-A., Niu, W., Ren, B., Wang, Y. & Shen, X. Survey: exploiting data redundancy for optimization of deep learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–38 (2023).

Yang, H., Lou, C., Li, W., Liu, G. & Tang, Y. Computational approaches to identify structural alerts and their applications in environmental toxicology and drug discovery. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33, 1312–1322 (2020).

Noutahi, E., Gabellini, C., Craig, M., Lim, J. S. C. & Tossou, P. Gotta be SAFE: a new framework for molecular design. Digit. Discov. 3, 796–804 (2024).

Harper, G., Bravi, G. S., Pickett, S. D., Hussain, J. & Green, D. V. S. The reduced graph descriptor in virtual screening and data-driven clustering of high-throughput screening data. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 44, 2145–2156 (2004).

Liao, C., Yu, Y., Mei, Y. & Wei, Y. From Words to Molecules: A Survey of Large Language Models in Chemistry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01439 (2024).

Feller, D. The role of databases in support of computational chemistry calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 17, 1571–1586 (1996).

Schwaller, P., Vaucher, A. C., Laino, T. & Reymond, J.-L. Prediction of chemical reaction yields using deep learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2, 015016 (2021).

Van Tilborg, D., Alenicheva, A. & Grisoni, F. Exposing the limitations of molecular machine learning with activity cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 5938–5951 (2022).

Leon, M., Perezhohin, Y., Peres, F., Popovič, A. & Castelli, M. Comparing SMILES and SELFIES tokenization for enhanced chemical language modeling. Sci. Rep. 14, 25016 (2024).

Scharfer, C. et al. Torsion angle preferences in druglike chemical space: a comprehensive guide. J. Med. Chem. 56, 2016–2028 (2013).

Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. ZINC: a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 45, 177–182 (2005).

Park, K., Lee, J., Jang, S. & Jung, D. An Empirical Study of Tokenization Strategies for Various Korean NLP Tasks. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02534 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. How Large a Vocabulary Does Text Classification Need? A Variational Approach to Vocabulary Selection. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10339 (2019).

Mahmoud, H. H., Hafez, A. M. & Alabdulkreem, E. Language-independent text tokenization using unsupervised deep learning. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 35, 321 (2023).

Hu, X., Chu, L., Pei, J., Liu, W. & Bian, J. Model complexity of deep learning: a survey. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 63, 2585–2619 (2021).

Gupta, A. et al. Generative recurrent networks for de novo drug design. Mol. Inform. 37, 1700111 (2018).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Polykovskiy, D. et al. Molecular sets (MOSES): a benchmarking platform for molecular generation models. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 565644 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Discovery of highly potent, selective, and orally efficacious p300/CBP histone acetyltransferases inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 63, 1337–1360 (2020).

Grisoni, F. et al. Combining generative artificial intelligence and on-chip synthesis for de novo drug design. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg3338 (2021).

Skinnider, M. A. Invalid SMILES are beneficial rather than detrimental to chemical language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 437–448 (2024).

Preuer, K., Renz, P., Unterthiner, T., Hochreiter, S. & Klambauer, G. Fréchet ChemNet distance: a metric for generative models for molecules in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 1736–1741 (2018).

Wildman, S. A. & Crippen, G. M. Prediction of physicochemical parameters by atomic contributions. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 39, 868–873 (1999).

Ertl, P. & Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminformatics 1, 1–11 (2009).

Bickerton, G. R., Paolini, G. V., Besnard, J., Muresan, S. & Hopkins, A. L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 4, 90–98 (2012).

Shultz, M. D. Two decades under the influence of the rule of five and the changing properties of approved oral drugs: miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 62, 1701–1714 (2018).

Panaretos, V. M. & Zemel, Y. Statistical aspects of Wasserstein distances. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 6, 405–431 (2019).

Grisoni, F., Moret, M., Lingwood, R. & Schneider, G. Bidirectional Molecule Generation with Recurrent Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 1175–1183 (2020).

Gaulton, A. et al. The ChEMBL database in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D945–D954 (2017).

Arús-Pous, J. et al. Randomized SMILES strings improve the quality of molecular generative models. J. Cheminformatics 11, 71 (2019).

Bjerrum, E. J. SMILES Enumeration as Data Augmentation for Neural Network Modeling of Molecules. ArXiv abs/1703.07076, (2017).

Nigam, A., Friederich, P., Krenn, M. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Augmenting genetic algorithms with deep neural networks for exploring the chemical space. ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv190911655 (2019).

Yoshikai, Y. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat. Commun. 15, 1197 (2024).

Moret, M., Friedrich, L., Grisoni, F., Merk, D. & Schneider, G. Generative molecular design in low data regimes. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 171–180 (2020).

Schwaller, P., Vaucher, A. C., Laino, T. & Reymond, J.-L. Data augmentation strategies to improve reaction yield predictions and estimate uncertainty. chemrxiv (2020).

Landrum, G. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software. https://www.rdkit.org/ (2016).

Tom, G., Yu, E., Yoshikawa, N., Jorner, K. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-tkjr1 (2024).

Bemis, G. W. & Murcko, M. A. The properties of known drugs. 1. Molecular frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 39, 2887–2893 (1996).

Langevin, M., Minoux, H., Levesque, M. & Bianciotto, M. Scaffold-constrained molecular generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 5637–5646 (2020).

Heid, E. & Green, W. H. Machine Learning of Reaction Properties via Learned Representations of the Condensed Graph of Reaction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 2101–2110 (2022).

Born, J. & Manica, M. Regression Transformer enables concurrent sequence regression and generation for molecular language modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 432–444 (2023).

Schneider, N., Lewis, R. A., Fechner, N. & Ertl, P. Chiral cliffs: investigating the influence of chirality on binding affinity. ChemMedChem 13, 1315–1324 (2018).

Schmidt, R. et al. Comparing molecular patterns using the example of SMARTS: theory and algorithms. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 2560–2571 (2019).

Hagberg, A. & Conway, D. Networkx: Network analysis with python. URL Httpsnetworkx Github Io (2020).

Acknowledgements

FG acknowledges the support from the Centre for Living Technologies. The authors acknowledge Derek van Tilborg for his comments on the manuscript draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.M., M.T., O.N., F.C., N.A., N.G., D.T., F.G. Data curation: F.M. Formal analysis: F.M. Investigation: F.M., M.T. Methodology: F.M., F.C., N.A. Software: F.M. Visualization: F.M. Writing, review and editing: all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Francesca Grisoni is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Chemistry, but was not involved in the editorial review of, or the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Kenneth Atz, Emmanuel Noutahi, and Giustino Sulpizio for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mastrolorito, F., Ciriaco, F., Togo, M.V. et al. fragSMILES as a chemical string notation for advanced fragment and chirality representation. Commun Chem 8, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01423-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01423-3

This article is cited by

-

How evaluation choices distort the outcome of generative drug discovery

Journal of Cheminformatics (2025)

-

Evaluation of chirality descriptors derived from SMILES heteroencoders

Journal of Cheminformatics (2025)