Abstract

Protonic ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) should exhibit high performance at intermediate temperatures in the range of 400–600 °C. To reduce the operating temperature, more active air electrodes (positrodes) are needed. In the present work, BaCo0.4Fe0.4Mg0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFMY) is investigated as a positrode material for application in PCFCs as well as solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). For SOFCs, the polarization resistance ascribed to the oxygen reduction reaction is proportional to pO2−1/4 (pO2: oxygen partial pressure), suggesting that the rate-determining process is the charge transfer on the mixed ionic-electronic conductors. For PCFCs, this polarization resistance is proportional to pO2−1/2, suggesting that the rate-determining process is the oxygen dissociation. The total polarization resistance for the PCFCs using the BCFMY positrode is 0.066 Ωcm2 at 600 °C, lower than that using the BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFZY) positrode. The higher oxygen nonstoichiometry of BCFMY promotes the oxygen dissociation process on the PCFC positrode surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protonic ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) are expected to serve as power generation systems with high energy conversion efficiency operated at intermediate temperatures of 600 °C. This is because the ionic conductivities of perovskite AB1-xB′xO3-δ (A = Ba, Sr, Ca; B = Ce, Zr; B′ = Y, Yb) electrolytes as reported by Iwahara et al.1,2, are higher than those of conventional zirconia-based electrolytes of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). Several researchers have reported negatrode-supported PCFCs with excellent performance3,4,5,6,7. However, the protonic transference number is not unity, because protons, oxide ions, and holes can be conducted through the PCFC electrolytes at high oxygen partial pressures (pO2) and high temperatures above 600 °C8. When an electrolyte with an ionic transference number less than 1 is used, hydrogen is consumed in the open circuit state, and activation polarization resistance is observed in this state owing to current leakage9. Consequently, the power generation efficiencies decrease for PCFCs10,11. The ionic transference number of PCFC electrolytes generally increases with decreasing temperature. In future, the operating temperature for PCFCs should be reduced to 300–400 °C for PCFCs. Which in turn should reduce costs, because expensive heat-resistant materials would be unnecessary for fabricating interconnectors, hot modules, and balance of plants.

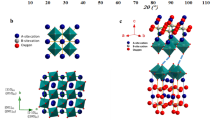

Novel positrode (air electrode) materials are required to reduce the operating temperature, because the oxygen reduction reaction is the rate-determining process for PCFCs12,13,14. The ionic transference number decreases when transition metals such as manganese, iron, cobalt, and nickel are dissolved in barium cerate15 and zirconate16. Although not suitable for application as electrolytes, triple conductors of protons, oxide ions, and holes indicate enhanced performance as electrodes. Recently, many researchers have focused on triple conductors as PCFC positrode materials, because the active areas for oxygen reduction and steam production reactions can spread to the entire surface of the positrode. For example, Ba(Ce, Zr, Y)1-x B′′xO3-δ (B′′: transition metals) is a candidate material for the fabrication of PCFC positrodes17. BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFZY) exhibits high performance due to its lower polarization resistance than that of Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3-δ (BSCF)5,18. Water uptake is observed using thermogravimetric (TG) analysis for BCFZY19. Perovskite PrNi0.5Co0.5O3-δ (PNC)20 and double perovskite PrBa0.5Sr0.5Co1.5Fe0.5O5+δ (PBSCF)21 have also been reported as triple conductors22. However, there is not enough evidence of the contribution from proton conductivity of triple conductive positrodes to the oxygen reduction and steam prodcution reactions. Using time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry with isotopic exchange (16O/18O and 1H/2H), Lozano et al.23 confirmed that protonic conductivity only makes a limited contribution to the steam production process, although oxygen surface exchange is promoted by the presence of steam on the surface of these materials. Therefore, activity of oxygen reduction reaction should be improved for PCFCs as well as SOFCs operated at intermediate temperatures (300–600 °C).

In the present work, BaCo0.4Fe0.4Mg0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFMY) is compared to BCFZY in SOFC and PCFC positrodes. It was reported that BCFMY exhibited higher the oxygen permeability than BCFZY because of its high oxygen nonstoichiometry (δ)24,25. High oxygen permeability is realized by the high ionic conductivity and active oxygen surface exchange process, which might reduce the polarization resistance of a positrode in fuel cells. However, materials with high oxygen permeability are not necessarily excellent as PCFCs positrodes. On the other hand, the polarization resistance decreased after incorporating BaCe0.7Zr0.1Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ (BCZYYb) in PCFC positrodes26. Based on these results, BCFMY-BCZYYb and BCFZY-BCZYYb composite positrodes are applied here in negatrode (fuel electrode)-supported PCFCs in addition to SOFCs, and the oxygen partial pressure dependency of polarization resistances is evaluated to discuss the oxygen reduction kinetics for the PCFC positrodes.

Results

SOFCs using BCFMY and BCFZY positrodes

The cross-sectional scanning electron microscopic images of the SOFCs with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes as shown in Fig. S1. Figure 1 shows the current-voltage and power density characteristics for the SOFCs with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes in 10, 21, 40, and 100%O2-N2 at 600 °C, and the data at 700 °C are show in Fig. S2. The theoretical electromotive force (VEMF) was derived from the Nernst equation for SOFCs (Eq. (1)):

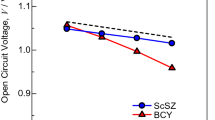

where Rg is the gas constant (8.3145 J mol−1 K−1), T is the absolute temperature (K), F is the Faradaic constant (9.6845 × 105 C mol−1), K is the equilibrium constant of the reaction H2 + 1/2O2 ↔ H2O (8.8072 × 1011 at 600 °C), and pX,a and pX,c are the partial pressures (atm) of X at the negatrode (anode) and positrode (cathode), respectively. The theoretical VEMF, experimental open circuit voltage (VOCV), and maximum power density (Pmax) are listed in Table S1. VOCV was 10–17 mV lower than VEMF owing to slight gas leakage, because the ionic transference number of scandia-stabilized zirconia (ScSZ) electrolyte is almost unity27. VOCV for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was almost the same as that with the BCFZY positrode. VOCV and Pmax increased with increasing oxygen concentration for both cells. Pmax for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was higher than that with the BCFZY positrode under all conditions.

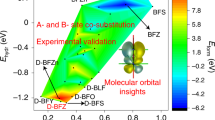

Figure 2a, b show the impedance spectra for the SOFCs with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes in 10, 21, 40, and 100%O2-N2 at 600 °C, and the data at 700 °C are show in Fig. S3. The total polarization resistance (Rp), which was derived from the total radius of the impedance arc in the Nyquist plot, increased with decreasing oxygen concentration for both cells. The impedance spectra were deconvoluted by the distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis as shown in Fig. 2c, d. Five DRT peaks were identified for both SOFCs. The previous papers28 reported the physicochemical origins of DRT peaks for SOFCs. Peak P4 at ca. 100 Hz is ascribed to the oxygen surface exchange and diffusion processes in the positrode, and it was smaller for the cell with the BCFMY positrode than that with the BCFZY positrode. In contrast, P3 at ca. 1 kHz and P5 at ca. 1 Hz, which are ascribed to the steam production and gas diffusion processes, respectively, in the negatrode, were almost the same between the two cells. Figure 3 shows the pO2 dependence of the ohmic and polarization resistances, which are derived from complex non-linear least squares (CNLS) fitting using an equivalent circuit model with a series connection of resistance (R0) and parallel resistance-capacitance (RkCk) elements (Eq. (2)):

where Z(ω) is the total impedance, τk is the time constant, j is the imaginary unit, ω is the angular frequency, and n is the number of DRT peaks. The slopes of R4 for the cells with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes were −0.25 and −0.33, respectively. These values were similar to those of conventional mixed ionic-electronic conductive positrodes such as La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ (LSCF) and BSCF29. R3 was also dependent on pO2 in the positrode despite of negatrode reaction for the SOFCs, because the steam production process required O2− ionic diffusion from the electrolyte. The slopes of R5 for the cells with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes were −0.30 and −0.43, respectively. The elementary electrode reactions will be discussed in the later section.

a, c BCFZY and b, d BCFMY positrodes are used in 10, 21, 40, and 100%O2-N2 at 600 oC. Each DRT peak is ascribed to the following process: P1; physical impedance between the electrolyte and electrode, P2; charge transfer in the negatrode, P3; steam production in the negatrode, P4; oxygen surface exchange and diffusion in the positrode, P5; gas diffusion in the electrode.

PCFCs using BCFMY and BCFZY positrodes

The cross-sectional scanning electron microscopic images of the PCFCs with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes as shown in Fig. S4. Figure 4 shows the current-voltage and power density characteristics for the PCFCs with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes in 9.7, 20, 40, and 97%O2-3%H2O-N2 at 600 °C, and the data at 700 °C are show in Fig. S5. VEMF was derived from the Nernst equation for PCFCs (Eq. (3)):

The theoretical VEMF, experimental VOCV, and Pmax are listed in Table S2. VOCV and Pmax increased with increasing oxygen concentration for both cells. Pmax for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was higher than that with BCFZY positrode under all conditions. Pmax was 1.01 W cm−2 in 97%O2-3%H2O at 600 °C for the PCFCs with the BCFMY positrode, which was 5.7 times higher than that for the SOFCs (0.177 W cm−2 in 100%O2). However, VOCV was 97–144 mV lower than VEMF, because of hole conductivity at high pO2 for the PCFCs using the BZYb electrolyte.

Figure 5a, b show the impedance spectra for the PCFCs with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes in 9.7, 20, 40, and 97%O2-3%H2O-N2 at 600 °C, and the data at 700 °C are show in Fig. S6. R0, which was derived from the intercept of the impedance arc at high frequencies, increased with decreasing oxygen concentration for the cells with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes because of hole conductivity in the Yb-doped barium zirconate (BZYb) electrolyte. Rp also increased with decreasing oxygen concentration. The ionic transference number (ti) was estimated from R0, Rp, VOCV, and VEMF8 (Eq. (4)):

a, c BCFZY and b, d BCFMY positrodes are used in 9.7, 20, 40, and 97%O2-3%H2O-N2 at 600 oC. Each DRT peak is ascribed to the following process: P1; physical impedance between the electrolyte and electrode, P2; charge transfer in the negatrode, P3; steam production in the positrode, P4; oxygen surface exchange and diffusion in the positrode, P5; gas diffusion in the electrode and nonstoichiometric oxygen variation at the interface between the electrolyte and positrode.

The values of ti were estimated to be 0.938–0.912 and 0.919–0.894 in 9.7–97%O2 for the PCFCs with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes, respectively. For the cell with BCFMY positrode, ti was slightly lower than that for the cell with the BCFZY positrode. On the other hand, Rp for the PCFCs was one order of magnitude smaller than that for the SOFCs at 600 °C. The impedance spectra were deconvoluted using the DRT analysis as shown in Fig. 5c, d. Five DRT peaks were identified in the DRT spectra for both PCFCs. Table S3 shows the physicochemical origins of DRT peaks for PCFCs. The cell with the BCFMY positrode indicated smaller P4 and P5 than those for the cell with BCFZY positrode. Figure 6 shows the pO2 dependence of the ohmic and polarization resistances, which were derived from the CNLS fitting using an equivalent circuit model with a series connection of ohmic resistance (R0) and parallel polarization resistance-capacitance (RkCk) elements as shown in Eq. (2). The slopes of R4 for the cells with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes were −0.59 and −0.55, respectively. These values were different from those for the SOFCs as shown in Fig. 3. The slopes of R3 are almost the same as that of R4, because both P3 and P4 processes occurred at the positrode. The slopes of R5 for the cells with BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes were −0.25 and −0.21, respectively. The cell with the BCFMY positrode indicated the lower R5, because its ti is lower than that for the cell with the BCFZY positrode.

Table 1 shows the R0 and Rp in 20%O2-3%H2O-N2 at 600 °C for the PCFCs with the BCFZY, and BCFMY positrodes. R0 for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was smaller than that with the BCFZY positrode despite of a lower electrical conductivity24. The cell with the BCFMY positrode exhibited a lower ti, which increased the hole conductivity. Rp for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was also smaller than that with the BCFZY positrode. It was reported that the oxygen permeability of BCFMY is higher than that of BCFZY because of a higher oxygen nonstoichiometry (δ)24,25. The higher δ possibly promotes the oxygen surface exchange process at the positrode. R0 and Rp for the PCFCs with the BSCF and BCFZY positrodes measured by Zhu et al.18 are also shown in Table 1. Although it is difficult to compare R0 among these cells, because R0 depends on the electrolyte thickness and cell configurations, the cell with the BCFMY positrode in the present work indicated the smallest Rp, suggesting the BCFMY is one of the most promising candidate materials for PCFC positrodes.

Discussion

Figure 7 shows the schematic of elementary positrode reactions for the SOFCs and PCFCs. Six processes are considered for the oxygen reduction reaction on the positrode30,31:

For the SOFCs, the rate-determining process is the charge transfer (Oad + Vo•• + 2e′ → OO×) on the entire surface of the mixed ionic-electronic conductors. For the PCFCs, the rate-determining process is the oxygen dissociation (O2,ad → 2Oad) on the positrode surface, because steam production is promoted along the processes shown as the dotted lines.

Process (1) O2(g) → O2,ad

Process (2) O2,ad → 2Oad

Process (3) Oad + e′ → O′ad

Process (6) \({{\rm{O}}}^{{\prime\prime} }_{{{\rm{TPB}}}}+{{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{o}}}}^{\bullet \bullet }\to {{{\rm{O}}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{\times }\)

Process (5) O′TPB+e′→O′′TPB

Process (4) O′ad → O′TPB

where r(n), R(n), i(n), \({\overrightarrow{k}}_{(n)}\) and \({\overleftarrow{k}}_{(n)}\), and aX are the reaction rate, resistance, current density, forward and reverse reaction constants of process (n), and the thermodynamic activity of X, respectively. When mixed ionic-electronic conductors are used as SOFC positrodes, the charge transfer process (7) Oad + Vo•• + 2e′ → OO× is proceeds on the entire surface, and the reaction rate of process (7) is the average of the reaction rates of processes (3), (4), (5), and (6)13,32. Therefore, R(7) is proportional to pO2−1/4, which agrees with the slope of R4 for the SOFCs as shown in Fig. 3. However, the slopes of R5 for the SOFCs with the BCFZY and BCFMY positrodes were −0.30 and −0.43, respectively, which disagrees with R(1) ∝ pO2−1. R5 also includes the polarization resistance ascribed to the gas diffusion process in the negatrode substrate, which is independent on pO2 at the positrode. For PCFCs, the slope of R5 is approximately −1/4 for PCFCs as shown in Fig. 6, because the nonstoichiometric variation of the BZYb electrolyte is similar to that in process (7). On the other hand, the slope of R4 for the PCFCs was also different from that for the SOFCs. Processes (5) and (6) hardly occur for the PCFCs, because the adsorbed OH can be generated from O’ and OH• at triple phase boundaries. Steam production is promoted along the processes shown as the dotted lines in Fig. 7, and the effect of proton conductivity in the positrode was limited. The slope of R4 was approximately −1/2 for the PCFCs as shown in Fig. 6, suggesting that the dominant rate-determining process is the oxygen dissociation (2). The polarization resistance for the cell with the BCFMY positrode was smaller than that for the cell with BCFZY positrode because of the higher oxygen nonstoichiometry.

Conclusion

In the present work, BCFMY is compared with BCFZY as positrodes in SOFCs and PCFCs. For both cells, the BCFMY positrode exhibited better performance than the BCFZY positrode because of a lower polarization resistance at ca. 100 Hz, which is ascribed to the oxygen surface exchange and diffusion processes. For the SOFCs, this resistance was proportional to pO2−1/4, and the rate-determining process was the charge transfer (Oad + Vo•• + 2e′ → OO×) on the entire surface of the mixed ionic-electronic conductors. On the other hand, the maximum power density was 1.01 W cm−2 in 97%O2-3H2O at 600 °C for the PCFCs with the BCFMY positrode, which was 5.7 times higher than that for the SOFCs (0.177 W cm−2 in 100%O2). The polarization resistance ascribed to the oxygen surface exchange and diffusion processes was proportional to pO2−1/2 for the PCFCs, and the rate-determining process was the oxygen dissociation (O2,ad → 2Oad) on the positrode surface. BCFMY is one of the most promising positrode materials, because its total polarization resistance was only 0.066 Ω cm2 in 21%O2-3%H2O-N2 at 600 oC.

Methods

Materials and cell preparation

(Sc2O3)0.10(CeO2)0.01(ZrO2)0.89 (ScSZ) and BaZr0.8Yb0.2O3-δ (BZYb) were chosen as electrolyte materials for the SOFCs and PCFCs, respectively. Planar NiO-ScSZ and NiO-BZYb substrates were prepared by uniaxial-pressing at 30 MPa and tape-casting, respectively. The weight ratio of NiO to ScSZ or BZYb was 6:4. Graphite powder was added as a pore former to increase the porosity of the negatrode substrates33. The ScSZ and BZYb were selected as electrolyte materials because of higher conductivity than (Y2O3)0.08(ZrO2)0.92 (YSZ)27 and higher durability than BaCe0.7Zr0.1Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ (BCZYYb)8, respectively. These electrolyte thin-films and Ce0.9Gd0.1O1.95 (GDC) interlayer were then fabricated by spin-coating using the slurries mixed with a binder (polyvinyl butyral; Sekisui Chemical), a dispersant (tallow propylene diamine, Kao), and a plasticizer (dioctyl adipate; Wako Pure Chemical) in ethanol and toluene for 48 h. The negatrode substrates and electrolyte thin-films were co-fired in air at 1400 and 1475 °C for the SOFCs and PCFCs, respectively. The GDC interlayer sintered at 1250 °C for 2 h in air was inserted between the electrolyte and positrode for the SOFCs. BaCo0.4Fe0.4Mg0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFMY) and BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ (BCFZY) powders were prepared by Pechini method24,25. The crystal structure, composition, and oxygen nonstoichiometry (δ) were evaluated using synchrotron X-ray diffraction, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and thermogravimetric analysis (TG) reported by Alam et al.24. The BCFMY and BCFZY positrodes incorporating BCZYYb were printed on the GDC interlayer and BZYb electrolyte, and then sintered at 1000 °C for 1 h in air. The weight ratio of BCFMY or BCFZY to BCZYYb was 7:3. The diameters of the positrodes and button cells were 6 and 23 mm, respectively.

Electrochemical Evaluation

The setup for the electrochemical evaluation is described in Ref. 34. Platinum meshes and paste were used as the current collectors. The button cells were heated to 700 °C, and then 97%H2-3%H2O gas was supplied to the negatrode for 3 h at a rate of 100 mL/min to reduce the nickel catalyst. Consequently, the temperature was decreased to 600 °C, and a mixed gas of x %O2-y %H2O-(100-x-y) %N2 (SOFC: x = 100, 40, 21, 10, y = 0, PCFC: x = 97, 40, 20, 10, y = 3) was supplied to the positrode at a rate of 200 mL/min. Current-voltage characteristics from VOCV to 0.4 V and electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at 0.85 V were recorded using a potentiostat/galvanostat with a frequency response analyzer (BioLogic VPS). The EIS data were deconvoluted by DRT analysis27,35,36 using the Z-Assist software37. The real impedance was used in the DRT analysis because of its lower susceptibility to measurement errors and inductive components than the imaginary impedance38. The Kramers-Kronig validation was performed using the K-K test39 and Lin-KK Tool40 software, revealing that the residuals between the measured and Kramers-Kronig transformed impedances were within 0.5%. Subsequently, the resistances and capacitances obtained from the DRT analysis were refined by CNLS fitting using the ZView software (Scribner Associates), assuming an equivalent circuit model with a series connection of resistance (R0) and parallel resistance-capacitance (RkCk) elements.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Iwahara, H., Esaka, T., Uchida, H. & Maeda, N. Proton conduction in sintered oxides and its application to steam electrolysis for hydrogen production. Solid State Ion. 3-4, 359–363 (1981).

Iwahara, H. Technological challenges in the application of proton conducting ceramics. Solid State Ion. 77, 289–298 (1995).

Choi, S. et al. Exceptional power density and stability at intermediate temperatures in protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nat. Energy 3, 202–210 (2018).

Dailly, J. & Marrony, M. BCY-based proton conducting ceramic cell: 1000 h of long term testing in fuel cell application. J. Power Sources 240, 323–3270 (2013).

Duan, C. et al. Readily processed protonic ceramic fuel cells with high performance at low temperatures. Science 349, 1321–1326 (2015).

Yang, L. et al. Enhanced sulfur and coking tolerance of a mixed ion conductor for SOFCs: BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2-xYbxO3-δ. Science 326, 126–129 (2009).

Duan, C. et al. Highly durable, coking and sulfur tolerant, fuel-flexible protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nature 557, 217–222 (2018).

Sumi, H. et al. Investigation of degradation mechanisms by overpotential evaluation for protonic ceramic fuel cells. J. Power Sources 582, 233528 (2023).

Nomura, K. & Kageyama, H. Transport properties of Ba(Zr0.8Y0.2)O3-δ perovskite. Solid State Ion. 178, 661–665 (2007).

Wang, Z., Mori, M. & Araki, T. Steam electrolysis performance of intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell and efficiency of hydrogen production system at 300 Nm3h-1. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 4451–4458 (2010).

Nakamura, T. et al. Energy efficiency of ionic transport through proton conducting ceramic electrolytes for energy conversion applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 15771–15780 (2018).

He, F., Peng, R. & Xia, C. Cathode reaction models and performance analysis of Sm0.5Sr0.5CoO3-δ-BaCe0.8Sm0.2O3-δ Composite cathode for solid oxide fuel cells with proton conducting electrolyte. J. Power Sources 194, 263–268 (2009).

Toriumi, H. et al. High-valence-state manganate(V) Ba3Mn2O8 as an efficient anode of a proton-conducting solid oxide steam electrolyzer. Inorg. Chem. Front. 6, 1587–1597 (2019).

Sumi, H. et al. External current dependence of polarization resistances for reversible solid oxide and protonic ceramic cells with current leakage. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 1853–1861 (2023).

Shimura, T., Tanaka, H., Matsumoto, H. & Yogo, T. Influence of the transition-metal doping on conductivity of a BaCeO3-based protonic conductor. Solid State Ion. 176, 2945–2950 (2005).

Han, D. et al. Electrochemical and structural influence on BaZr0.8Y0.2O3-δ from manganese, cobalt, and iron oxide additives. J. Am. CerAm. Soc. 103, 346–355 (2020).

Kasyanova, A. V., Tarutina, L. R., Rudenko, A. O., Lyagaeva, J. G. & Medvedev, D. A. Ba(Ce,Zr)O3-based electrodes for protonic ceramic electrochemical cells: towards highly compatible functionality and triple-conducting behaviour. Russ. Chem. Rev. 89, 667–692 (2020).

Zhu, L., O’Hayer, R. & Sullivan, N. P. High performance tubular protonic ceramic fuel cells via highly-scalable extrusion process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 27784–27792 (2021).

Ren, R. et al. Tuning the defects of the triple conducting oxide BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ perovskite toward enhanced cathode activity of protonic ceramic fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 18365–18372 (2019).

Ding, H. et al. Self-sustainable protonic ceramic electrochemical cells using a triple conducting electrode for hydrogen and power production. Nat. Commun. 11, 1907 (2021).

Seong, A. et al. Electrokinetic proton transport in triple (H+/O2-/e-) conducting oxides as a key descriptor for highly efficient protonic ceramic fuel cells. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004099 (2021).

Merkle, R., Hoedl, M. F., Raimondi, G., Zohourian, R. & Maier, J. Oxides with mixed protonic and electronic conductivity. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 51, 461–493 (2021).

Lozano, H. T., Druce, J., Cooper, S. J. & Kilner, J. A. Double perovskite cathodes for proton-conducting ceramic fuel cells: are they triple mixed ionic electronic conductors? Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 18, 977–986 (2017).

Alam, M. S., Kagomiya, I. & Kakimoto, K. Tailoring the oxygen permeability of BaCo0.4Fe0.4Y0.2-xAxO3-δ (x = 0, 0.1; A: Zr, Mg, Zn) cubic perovskite,. Ceram. Int. 49, 11368–11377 (2023).

Alam, M. S., Kagomiya, I. & Kakimoto, K. Oxygen non-stoichiometry and mixed conductivity of Ti-doped BaCo0.4Fe0.4Y0.2O3-δ perovskite,. Solid State Ion. 395, 4116203 (2023).

Watanabe, K. et al. Performance enhancement of protonic ceramic fuel cells using a co-free La0.65Ca0.35FeO3-δ cathode composited with perovskite Ba(Ce,Zr)O3-δ-based oxides. Ceram. Int. 50, 40402−40408 (2024).

Kosacki, I., Anderson, H. U., Mizutani, Y. & Ukai, K. Nonstoichiometry and electrical transport in Sc-doped zirconia. Solid State Ion. 152-153, 431–438 (2002).

Sumi, H., Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Yamaguchi, T. & Fujishiro, Y. Degradation evaluation by distribution of relaxation times analysis for microtubular solid oxide fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 339, 135913 (2020).

Takeda, Y., Kannno, R., Noda, M., Tomida, Y. & Yamamoto, O. Cathodic polarization phenomena of perovskite oxide electrodes with stabilized zirconia. J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 2656–2661 (1987).

van Heuveln, F. H. & Bouwmeester, H. J. M. Electrode properties of Sr-doped LaMnO3 on Yttria-stabilized zirconia. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 134–141 (1997).

Kim, J.-D. et al. Characterization of LSM-YSZ composite electrode by AC impedance spectroscopy. Solid State Ion. 143, 379–389 (2001).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhanced oxygen reduction kinetics of IT-SOFC cathode with PrBaCo2O5+δ/Gd0.1Ce1.9O2-δ coherent interface. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 3495–3505 (2022).

Sumi, H., Yamaguchi, T., Hamamoto, K., Suzuki, T. & Fujishiro, Y. Effects of anode microstructure on mechanical and electrochemical properties for anode-supported microtubular solid oxide fuel cells. J. Am. CerAm. Soc. 96, 3584–3588 (2013).

Sumi, H., Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Nomura, K. & Sato, K. Why is the performance different between small- and large-scale SOFCs? Electrochim. Acta 443, 141965 (2023).

Schichlein, H., Muller, A. C., Voigts, M., Krugel, A. & Ivers-Tiffée, E. Deconvolution of electrochemical impedance spectra for the identification of electrode reaction mechanisms in solid oxide fuel cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 32, 875–882 (2002).

Leonide, A., Rüger, B., Weber, A., Meulenberg, W. A. & Ivers-Tiffée, E. Evaluation and modeling of the cell resistance in anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B234–B239 (2010).

Weese, J. A reliable and fast method for the solution of fredhol integral equations of the first kind based on tikhonov regularization. Comput. Phys. Commun. 69, 99–111 (1992).

Ivers-Tiffée, E. & Weber, A. Evaluation of electrochemical impedance spectra by the distribution of relaxation times. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 125, 193–201 (2017).

Boukamp, B. A. A linear Kronig-Kramers transform test for immittance data validation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142, 1885–1894 (1995).

Schönleber, M., Klotz, D. & Ivers-Tiffée, E. A method for improving the robustness of linear Kramers-Kronig validity tests. Electrochim. Acta 131, 20–27 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This paper is partially based on results obtained from a project entitled “Development of Ultra-High Efficiency Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cell Devices, Collaborative Industry-Academia-Government R&D Project for Solving Common Challenges Toward Dramatically Expanded Use of Fuel Cells and Related Equipment” (JPNP20003) commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. Sumi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing-Original draft preparation. K.W.: Resources, Data curation. A.S.: Investigation. M.F.: Validation. H. Shimada: Resources, Investigation. Y.M.: Supervision. M.S.A.: Resources, I.K.: Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Inyoung Jang and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sumi, H., Watanabe, K., Sharma, A. et al. Oxygen reduction kinetics of high performance BaCo0.4Fe0.4M0.1Y0.1O3-δ (M = Mg, Zr) positrode for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Commun Chem 8, 71 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01468-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01468-4