Abstract

Polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) thin films, fabricated at nano-scale by Layer-by-Layer (LbL) self-assembly techniques, have diverse nanotechnology applications. Precise thickness measurement during layer buildup is crucial in controlling the thickness. In this work, we present a novel optical measurement technique for in-situ analysis of the PEM film build-up by utilizing Etched Fiber Bragg Gratings (EFBG)-based sensors to quantify the deposited thickness. PEM films were deposited over EFBG by alternative deposition of weak polyelectrolytes Poly(allylamine hydrochloride)(PAH) and Poly(acrylic acid)(PAA) with quantitative analysis of adsorption and desorption steps at varying pH conditions. Further, the desorption process was observed in detail at the sub-nanometer scale, with PAA exhibiting a linear desorption while PAH follows an exponential desorption. This validates the inter-diffusive behavior of the low molecular weight polyelectrolytes during the PEM buildup, not only during the adsorption process but also during the desorption process. Thus, EFBG could be utilized as a precision tool to extract fundamental information during individual PEM layer build-up, thereby fine-tuning the nano-scale architecture of multilayers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly of polyelectrolytes, proposed by Decher et al., is a unique and cost-effective technique to fabricate molecularly thin films on a wide range of substrates without using expensive infrastructure1,2,3. LbL technology involves the adsorption and desorption processes of oppositely charged polymer ions, followed by rinsing with de-ionized (DI) water to build up polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) films. PEM deposition is primarily driven by electrostatic interaction and assembly parameters like pH, ionic strength, molecular weight, dipping, and rinsing time. The fabrication protocol determines the morphological and optical characteristics of the PEM film. The properties of PEM have been characterized in their dry state by utilizing optical techniques such as ellipsometry and surface plasmon spectroscopy4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. The kinetics of the progressive layer build-up and quantitative analysis of LbL adsorption of various polyelectrolyte pairs under different deposition conditions have been explored using multiple in-situ analysis techniques like Ellipsometry, Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Surface Plasmon Spectroscopy (SPS) and Optical Waveguide Lightmode Spectroscopy (OWLS)12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. These techniques have been used along with optical techniques like Confocal microscopy, Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP), Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), and non-optical techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Secondary Ion Mass Spectroscopy (SIMS) for probing interlayer diffusion19,22,26,27,28,29,30. Confocal microscopy is more suitable for thick films and cannot be used for films with thicknesses less than 100 nm19,22. Optical techniques like FRAP and FRET require fluorescent tagging of diffusing species28,29,30, while non-optical techniques like XPS and SIMS can alter the native structure of PEM films26,27. Fiber optic multicavity Fabry-Perot interferometric sensors have been developed for monitoring the buildup of PEM films with a reported resolution of 0.1 nm, but the fabrication procedure for such structures involves cleaving a silica capillary tubing and splicing it to another single-mode fiber, making it notably challenging to replicate31.

Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBG) sensors are wavelength-modulation-based sensors with a very high sensitivity and sampling rate compared to intensity-modulated optical sensors. They can be used to detect the thickness deposited over its surface in real-time from the change in Bragg wavelength shift due to the change in the effective refractive index of the sensing element. FBGs have also been written over sensing structures like exposed core micro-structured optical fibers to improve their sensitivity32. These micro-structured fiber structures have to be drawn from a preform and needs to be spliced to single mode fibers for using them in sensing, making it a challenge to achieve high efficiency and repeatability.

Etched Fiber Bragg Grating (EFBG) sensors, obtained via chemical etching of FBGs, also operate by detecting the shift in Bragg wavelength, with the added advantage of having a significantly higher sensitivity which is comparable to Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)-based techniques33,34. EFBGs can be easily embedded in a microfluidic channel to probe a very low volume of analytes and are ideal for probing the kinetics of ultra-thin film deposition with a thickness range of 1-2 nm during the initial layers deposition33,35.

The growth mechanism of weak polyelectrolytes participating in the layer buildup process has been under investigation for a long time. pH-dependent modulation in thickness, surface roughness, wettability, and porosity has been studied extensively4. PEM buildup occurs largely due to consecutive alternative deposition of oppositely (positively and negatively) charged polymers due to the surface charge reversal at each deposition step, resulting in a gradual build-up of the PEM stack. The LbL assembly of Poly (allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and Poly (acrylic acid) (PAA) is due to the formation of water-insoluble complexes of polycations and polyanions through electrostatic attractions36. It has also been shown that (PAH/PAA) multilayers could be adsorbed as “thick and rough” or “thin and smooth” films just by altering the pH of the polyelectrolyte solution. A simple pH-based modification also helped in tuning the nanoscale porosity of the films5. These were ex-situ analyses performed on films after the deposition process, thus missing out on critical information about the kinetics of layer deposition. In another significant QCM-based in-situ study, pH regimes were identified, and the (PAH/PAA) buildup was exponential due to the interdiffusion of polyelectrolytes. In other pH regimes, the growth was linear due to the opposition of precursor layers for the inter-diffusion of polyelectrolytes37. It was also shown in an earlier work that low molecular weight PAH can diffuse “in and out”, resulting in an exponential layer build-up38. The buildup mechanism was also observed in real-time for certain biopolymers, namely (poly(L-lysine)/ hyaluronic-acid (PLL/HA), in which the mechanism of growth was exponential due to the “in and out” diffusion of polyelectrolytes, as elaborated in similar works19,22. The interdiffusion of polymer chains was also observed in poly(L-lysine)/poly(L-glutamic acid) (PLL/PGA) system by examining the distance-dependent fluorescence intensity of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled PLL39. Additionally, the diffusivity of PLL chains was found to vary with changes in the ionic strength of the surrounding medium39.

In this work, an in-situ analysis of the weak PEM (PAH/PAA) buildup process was monitored using an EFBG-based optical sensing interrogation system. An investigation of the adsorption and desorption kinetics of PAH/PAA in the layer buildup was carried out under two different pH conditions, i.e., pH 5.5 and pH 7. All the experiments were performed by using low molecular weight PAH (Mw ~ 15 kDa) and high molecular weight PAA (Mw ~ 150 kDa). As pH plays a significant role in the charge density of weak polyelectrolytes, its significance in determining the thickness of the PEM film has been validated through EFBG. The optical EFBG technique allows us to observe the difference in thicknesses at the two pH values, even at the initial stages of layer build-up when the thickness of the film is below 100 nm. This in-situ monitoring also allows a unique perspective on the desorption phenomenon during the rinsing step. PAA is observed to have a linear rate of desorption, while PAH is observed to have an exponential rate of desorption after the rinsing steps. This validates the “in and out” diffusion of low molecular weight PAH, leading to the exponential growth of (PAH/PAA) PEM system, as claimed by other groups38,40. In addition, a quantitative analysis of adsorbed and desorbed polymer masses was also performed to understand the contribution of each step of poly-ions during the multi-layer buildup process. Thus, Bragg wavelength shifts from the EFBG measurements can be used to monitor individual layer growth and control the film thickness precisely, even at the sub-nanometer scale, by fine-tuning the LbL deposition parameters.

Results and discussions

Experimental setup

The PEM film deposition process involves the inflow of solutions of polycations (PAH) and polyanions (PAA) in an alternating manner into a Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) microfluidic channel housing the optical EFBG sensor, as shown in Fig. 1(a). The channel has a width of 100 μm and a depth of 50 μm and allows for accurate regulation of the flow rate of around 1 \(\mu L/\min\), to ensure precise control over the deposition process. We first injected PAH solution into the respective tubing connected to the inlet pipe which feeds into the microfluidic channel. The outlet knob is closed for 20 min, keeping the EFBG sensor dipped in the PAH solution. Following this, the PAH solution is cleared out by opening the outlet for 5 min and injecting DI water into the channel. The same procedure is then used for depositing PAA, followed by the rinsing step. This buildup process on the EFBG sensor as depicted in Fig. 1(a) (inset). The deposition process is monitored in situ using the optical interrogator system, which measures the Bragg wavelength shift at a sampling rate of 1 Hz. The increase in Bragg wavelength during the pumping of PAH and PAA solutions indicates the deposition of PEM. In contrast, a decrease in Bragg wavelength during the rinsing process is indicative of the desorption of PEM. This process is repeated to obtain the desired number of bilayers while continuously monitoring the Bragg wavelength. The notation EFBG-(PAH pH/PAA pH) n will be used in this work to represent the layer buildup of PEMs on EFBGs sensors, where ‘n’ stands for the number of bi-layers being adsorbed on EFBGs and pH corresponds to the pH of the polyelectrolyte solution.

a Schematic illustration of the experimental setup of LbL deposition on EFBG. Inset (a) Schematic diagram of FEM model for EFBG for generating thickness data from experiments. b Thickness values \((t)\) in nm for different values of Bragg wavelength shifts \((\Delta {\lambda }_{B})\) using exponential growth model of the FEM model.

Modelling EFBG

The electromagnetic waves frequency domain interface in the wave optics module of COMSOL multiphysics was utilized to model the EFBG. The schematic of the EFBG design is shown in Fig. 1(a) (inset). The electromagnetic waves frequency domain interface uses the Finite element method (FEM) to solve the frequency domain form of Maxwell’s equations and provides the electric field distribution for the design structure. The effective refractive index (\({n}_{{eff}}\)) obtained from the simulations is used to obtain the Bragg wavelength using Eq. 1. The simulation parameters utilized for the simulations are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

As the adsorbed polyelectrolyte thickness changes, the corresponding Bragg wavelength of the EFBG shifts. The Bragg wavelength for different values of adsorbed thickness was obtained, and an exponential growth model given in Eq. 2 was used to obtain a relation between the two parameters.

Where, t is the adsorbed thickness in nm, and \(a\) and \(b\) are the curve-fitting constants. The values of the constants were obtained using curve fitting as a = 337.1 nm and b = 0.773 nm−1. The fit model is shown in Fig. 1(b) which shows the simulated values of adsorbed thickness for different Bragg wavelength shifts. Using this relation, the real-time change in Bragg wavelength data can be mapped to the thickness of polymer adsorbed over the EFBG.

Mechanism of layer growth

Polyelectrolyte multilayer buildup at the surface of EFBG takes place primarily due to consecutive alternative deposition of oppositely charged polymers causing a surface charge reversal at each deposition step, resulting in a gradual layer build-up of polyelectrolytes. The LbL assembly of PAH/PAA is due to the ionic attractions between the carboxylate (COO-) and ammonium (NH3+) groups resulting in the formation of polyelectrolyte complexes of polycations and polyanions as shown in Fig. 2(a)36. Adsorption of the PEM complex on the EFBG surface causes a change in \({n}_{{eff}}\) of the EFBG. This causes a shift in Bragg wavelength as per Eq. 1, which is monitored by using our measurement setup, as shown in Fig. 1(a). Three separate experiments were carried out for each pH on different EFBG sensors. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the shift in Bragg wavelength, monitored in situ, during layer-by-layer adsorption of weak polyelectrolytes for one set of experiments. An increase in the Bragg wavelength shows layer buildup of individual experiments of EFBG-(PAH5.5/PAA5.5)n and EFBG-(PAH7/PAA7)n self-assembly at pH 5.5 and pH 7. The Bragg wavelength shift data was converted the adsorbed polyelectrolyte thickness using the exponential model in Eq. 1 to obtain Fig. 2(d). Initially, it can be seen from Fig. 2d that, the PEM growth is linear. At the 5th bilayer mark, an exponential growth in the deposition is observed. The rate of deposition is observed to be faster for pH= 5.5 than pH=7. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the deposition of individual polyelectrolyte layers, and supplementary Figs. 3(a), (b) define the conventions used for the various parameters for the quantitative analysis in this paper.

a LbL deposition due to coulombic electrostatic interaction between anionic PAA and cationic PAH chains. b SEM image of PEM-coated EFBG. c Schematic of “in and out” diffusion mechanism for (PAH/PAA) multilayer after deposition of 5 bilayers. d PAH/PAA layer deposition expressed in terms of thickness deposited over the EFBG surface.

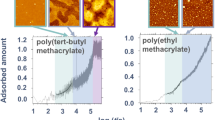

Figure 3a, b compare relative pre and post-rinse growth curves of (PAH5.5/PAA5.5)n with (PAH7/PAA7)n. system respectively. Figure 3c, d compare the relative pre- and post-rinse growth curves of the two systems with respect to the extracted thickness values from COMSOL simulations. The growth curves have been plotted for a set of 3 experiments for pH 5.5 and pH 7 systems. It was evident from both pre- and post-relative growth curves that the total growth of the pH 5.5 system was about 42% (43%) and 48% (50%), relatively higher than that of the pH 7 system, respectively. Another interesting observation was that, for both pH 5.5 and pH 7.0 systems, there was exponential growth.

a Pre-rinse growth curve using Bragg wavelength shift data. b Post-rinse growth curve using Bragg wavelength shift data. c Pre-rinse adsorbed experimental thickness measurement fitted with COMSOL simulations. d Post-Rinse adsorbed experimental thickness measurement fitted with COMSOL simulations. Error bars indicate one standard deviation from the mean value, n = 3.

The buildup mechanism that leads to exponential growth can be explained by the “in and out” diffusion of one among the two oppositely charged polyelectrolytes during the layer buildup. This hypothesis was experimentally validated earlier, in which one of the polyelectrolytes, PLL, diffuses into precursor layers during the adsorption step. PLL diffuses out during subsequent rinsing and continues to diffuse out even when dipped in oppositely charged HA, during which inter-polyelectrolyte complex is formed on the surface, resulting in the exponential growth of PEMs22. The influence of low molecular weight PAH was also studied, and it was observed that PAH is able to diffuse “in and out” of the film during assembly, resulting in an exponential layer build-up37. It was also observed for strong polyelectrolyte systems that the diffusion coefficient of polyanions decreases with their molecular weight in poly-(diallyldimethylammonium)/polystyrene sulfonate (PDADMA /PSS) system, which causes a decrease in the mobility of the diffusing species41,42. The same theory is likely to apply to the PAH/PAA system, where the low molecular weight mobile PAH polycations can diffuse throughout the film. The PEM thickness deposited is thus proportional to the number of mobile ions that have diffused in the film during the previous deposition step. The new thickness of the PEM film can be depicted as19.

where, δT(n + 1) is the change in thickness on the deposition of a new layer, T(n) is the current thickness of the assembly, and \(k\) is a proportionality constant. This results in the exponential growth of the PEM system. Hence, it can be concluded from the investigations discussed so far that the “in and out” diffusion of PAH (low molecular weight) during the layer buildup process might be the possible reason for the exponential growth of (PAH/PAA) multilayer system. Additionally, the absolute desorption analysis for both pH systems was also performed.

Figure 4a, b shows the absolute values of an inter-sample mean of the desorbed mass (\({\Delta \lambda }_{{des}}\)) which is the difference between \({\lambda }_{{post}}\) and corresponding \({\lambda }_{{pre}}\). Figure 4c, d show the desorbed values of thickness (Δtdes) after each rinse for PAA and PAH. It is evident from Fig. 4 that the decrement in the mass of PAH is exponential for both pH 5.5 and pH 7 systems, and the decrement in mass is linear for PAA in both systems. While the contribution of low molecular PAH chains to adsorption is greater than that of PAA, their short chain lengths result in weaker attachment to the EFBG surface, which is evident in its exponential desorption. All these observations emphasize that irrespective of the assembly pH, the “in and out” diffusion of PAH may eventually lead to the exponential growth of PEMs. The “inand out” diffusion of PAA might not be observed as it has a higher molecular weight, and its mobility is suppressed due to its more coiled chain structure than its counter ions. pH, which plays a crucial role in the degree of ionization of weak polyelectrolytes, does not seem to cause any significant change in the desorption characteristics.

a Desorption curves of PAH and PAA of pH 5.5 system. b Desorption curves of PAH and PAA of pH 7 system. c Desorption curves of PAH and PAA of pH 5.5 system with extracted thickness. d Desorption curves of PAH and PAA of pH 7 system with desorbed thickness. Error bars indicate one standard deviation from the mean value, n = 3.

Determination of mass during layer adsorption and desorption

From the desorption analysis shown in Figs. 4c, d, if the decrement in the adsorbed amount of PAH in both the systems was considered, the growth constant, b, of pH 5.5 is ~0.2309, whereas, for pH 7 system, b is approximately 0.1672. This implies that the amount of PAH diffusing out from the PEMs is lesser in the pH 7 system than in the pH 5.5 system. Figure 4 also shows the desorption curves for PAA of both the systems. The desorption of PAA is linear in both cases, but the slopes are different (−1.099 for pH 5.5 and −0.8511 for pH 7). This implies that a relatively smaller amount of PAA is being used for layer buildup in the pH 7 system than in the pH 5.5 system. In order to understand the contribution of each polyelectrolyte to the layer buildup mechanism, mean-based mass adsorption and desorption calculations were performed for both pH systems.

Using Eqs. 4 & 5, Mass fraction analysis was performed for both adsorbed (MFads) and desorbed (MFdes). The initial mass (Γinit) is the mass of polyelectrolytes that adsorbs to the surface before rinsing. The actual adsorbed mass (Γact) is the mass retained on the surface as molecularly thin film after successive post-rinse process Fig. 5a, b shows the plot for mass fraction analysis for both pH systems. It is evident from Fig. 5(a) that approximately 60% of the mass fraction of PAH and PAA participates in the layer buildup of the pH 5.5 system, and only around 20 to 30% of the mass fraction of polyelectrolytes participates in the layer buildup of the pH 7 system (Fig. 5b). As the exponential growth depends on the mass of PAH that possibly diffuses “in and out” of the polymer stack, the mass fraction of adsorption might be higher in the pH 5.5 system than in the pH 7 system.

Kinetic analysis and limit of detection

Analysis of the kinetics of LbL assembly of pH 5.5 and pH 7 systems was performed by considering the meantime taken by each polyelectrolyte to reach 90% of their saturation thickness during each layer buildup. Figure 6a shows the quantified time analysis of pH 5.5 and pH 7 systems. For the pH 5.5 system, the adsorption time of PAH for the 6th layer is around five minutes, while PAA requires thirteen minutes to reach 90% of its saturated thickness. Even for the pH 7 system, the adsorption time for the 6th layer of PAH is less than PAA by around a minute. These findings illustrate that PAH adsorption is faster than PAA due to its lower molecular weight and associated electrostatic interactions25. On the contrary, high molecular weight PAA suppresses the interlayer diffusion while slowing down the deposition significantly due to the highly coiled structure of high molecular weight PAA chains40. The difference in the saturation time for different pH is due to a change in the degree of ionization, which contrasts the adsorption due to the electrostatic interaction between the multilayered surface and the incoming polymeric chain.

The results of this study point to the many advantages of EFBG, including its low noise, high sensitivity, and real-time measurements. Figure 6(b) compares the popular PEM thickness monitoring techniques with respect to their limit of detection. Ellipsometry is one of the most popular methods for thickness characterization and can be used for sub-nanometer thickness measurements, but requires bulk film’s optical characteristics to be known in advance, and the substrate roughness results in uncertainty in the measurement, especially for ultrathin films below 25 nm43,44. QCM and AFM are the popular non-optical techniques for monitoring PEM buildup. Although AFM gives absolute thickness measurement, it is based on the height difference between the substrate and the film’s surface by creating a step patterning or a ‘tip scratch’45. QCM, on the other hand, can provide inaccurate thickness measurement due to changes in mass on account of adhered liquids46.

EFBG not only allows us to observe PEM buildup during the initial layers at nano-scale (less than 10 nm) but also provides compelling evidence for the “in and out” diffusion of lower molecular weight species during the adsorption of PEM complex at the dipping and desorption phases. Confocal microscopy, which has been widely used for reporting “in and out” diffusion, has limited sensitivity due to the diffraction limit, and PEM films need to be deposited to several micrometers thickness, while FRAP and FRET require fluorescent tagging of diffusing species46. Non-optical methods like XPS and SIMS can be used to study inter-layer diffusion, but they are destructive techniques that lead to changes in the nativity of the deposited PEM films46. EFBG can be used as a standalone optical technique for thickness measurement and probing the “in and out” diffusion, thereby helping us to analyze the influence of various factors that determine PEM film buildup, thus enabling and expediting their utility in multiple nanotechnology and biosensing applications.

Conclusion

In-situ studies on layer buildup mechanism were performed on weak polyelectrolyte-based PEMs with EFBGs. The studies on weak polyelectrolyte systems point to an “inter diffusive” behavior of low molecular weight PAH leading to the exponential growth of PEMs. The studies on adsorbed and desorbed mass at different assembly pH emphasize that the modulation in optical properties, like the thickness of PEMs, can be attributed to the differences in the extent of “in and out” diffusion of PAH in the PEMs at different assembly pH conditions. EFBG measurement is dependent on the Bragg wavelength shift, which can be measured accurately up to 1 pm accuracy. This allows us to monitor the nano-scale PEM deposition, giving significant insight into the “in and out” diffusion phenomenon at the initial layer buildup. The measurement setup is also relatively inexpensive and can be applied to analyze films with a wide range of thicknesses. The EFBGs in-situ method is extremely versatile in studying the kinetics of the sequential deposition of self-assembled species and can help tune the parameters in the multilayer build-up process and explore the bio-molecule adsorption and desorption process.

Methods

Materials

The polyelectrolytes, PAH of Mw~15 KDa, and PAA 150 KDa were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. The Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Hydrochloric acid (HCl), and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) were acquired from Merck for adjusting ionic concentration and pH. Polyelectrolyte solutions were prepared for ionic strength of 0.1 M and 0.01 M concentration based on repeat unit molecular weight using 18.2MΩ ultra-pure DI water from a Millipore purification system. The optical fiber SM1500 was procured from Fibercore Inc., USA. SM1500 supports single-mode light propagation in the wavelength range of 1550–1650 nm.

Fabrication of fiber Bragg gratings

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors were fabricated using photosensitive fiber SM1500, sourced from Fibercore Inc., USA. This fiber features a core diameter of 4.2 μm of with a refractive index of 1.4749, and a cladding diameter of 80 μm with a refractive index of 1.4440. The phase mask technique was utilized to inscribe the gratings on the photosensitive core, wherein the fiber was exposed to 248 nm KrF excimer laser pulses with an energy of 3 mJ and a repetition rate of 200 Hz33. The laser beam was passed through a phase mask (pitch = 1064 nm) to generate an interference pattern that induced a localized refractive index modulation within the core, thereby forming the FBG structure33. The grating inscription was performed over a length of approximately 3 mm, with the resulting grating periodicity of ~532 nm, yielding a baseline Bragg wavelength around 1550 nm.

Fabrication of EFBG

The cladding of the FBG sensor was etched by dipping it in an aqueous solution of Hydrofluoric acid (HF) at 40% concentration. During the etching process, the shift in the Bragg wavelength was continuously monitored, and the etching was stopped when the Bragg wavelength shifted by a predetermined value.

Preparation of polyelectrolytes and maintaining the pH

Polyelectrolytes PAH and PAA were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, India. 18.2 MΩ De-ionized (DI) water from the Merck Millipore unit was used to prepare all the aqueous solutions. Polyelectrolyte solutions were prepared with 0.01 M (based on repeating unit Mw of Polyelectrolyte) concentration, with ionic strength of 0.1 M NaCl. The pH of polyelectrolyte solution (PAH/PAA) was adjusted to 5.5/5.5 or 7.5/3.5 using 0.1 M NaOH and 0.1 M HCl. All chemicals were utilized without undergoing any further purification procedures.

PEM in-situ monitoring using optical EFBG technique

In-situ studies of the PEM film deposition were performed by alternatively dipping the EFBGs in cationic polyelectrolyte solution (PAH) and anionic polyelectrolyte solution (PAA), with intermittent rinsing steps. The dipping period was maintained at 20 min, and any loosely bound polyelectrolyte ions were removed with a 5 min DI water rinsing cycle.

Optical sensing interrogator system

SM130 from Micron Optics Inc., USA, was used for optical interrogation, which consists of a 10 mW light source centered wavelength around 1550 nm with a 40 nm bandwidth. The resolution of this system is 1 pm at a sampling rate of 1 kHz.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy

The surface morphology studies were performed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) from Zeiss. For SEM studies, the PEMs were desiccated overnight, and the dried samples were sputtered with 2 nm of gold using the sputtering unit from Zeiss. The images were taken using an “in-lens” detector of SEM at a working distance (WD) of 1:5 mm ≤ WD ≤ 5 mm. The beam accelerating voltage was kept ≤ 15 KeV.

Ellipsometry

The thickness of PEMs was measured using M-2000, a variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometer from J.A. Woollam. Accurate measurements of the thickness of polymers need careful modelling techniques to obtain accurate results. Unknown optical parameters, thickness, and complex refractive index of the PEM film are obtained by fitting the experimental Ψ and ∆ values to Fresnel equations using extensive modelling techniques47.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Decher, G., Hong, J. D. & Schmitt, J. Buildup of ultrathin multilayer films by a self-assembly process: III. Consecutively alternating adsorption of anionic and cationic polyelectrolytes on charged surfaces. Thin Solid Films 210–211, 831–835 (1992).

Decher, G. Fuzzy nanoassemblies: toward layered polymeric multicomposites. Science 277, 1232–1237 (1997).

Prashanth, G. R., Goudar, V. S., Suran, S., Raichur, A. M. & Varma, M. M. Non-covalent functionalization using lithographically patterned polyelectrolyte multilayers for high-density microarrays. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 171–172, 315–322 (2012).

Shiratori, S. S. & Rubner, M. F. pH-dependent thickness behavior of sequentially adsorbed layers of weak polyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 33, 4213–4219 (2000).

Hiller, J., Mendelsohn, J. D. & Rubner, M. F. Reversibly erasable nanoporous anti-reflection coatings from polyelectrolyte multilayers. Nat. Mater. 1, 59–63 (2002).

Cho, J., Char, K., Hong, J.-D. & Lee, K.-B. Fabrication of highly ordered multilayer films using a spin self-assembly method. Adv. Mater. 13, 1076–1078 (2001).

Lee, S.-S. et al. Layer-by-layer deposited multilayer assemblies of ionene-type polyelectrolytes based on the spin-coating method. Macromolecules 34, 5358–5360 (2001).

Chiarelli, P. A. et al. Controlled fabrication of polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films using spin-assembly. Adv. Mater. 13, 1167–1171 (2001).

Zhai, L., Nolte, A. J., Cohen, R. E. & Rubner, M. F. pH-gated porosity transitions of polyelectrolyte multilayers in confined geometries and their application as tunable Bragg reflectors. Macromolecules 37, 6113–6123 (2004).

Kharlampieva, E., Kozlovskaya, V., Chan, J., Ankner, J. F. & Tsukruk, V. V. Spin-assisted layer-by-layer assembly: variation of stratification as studied with neutron reflectivity. Langmuir 25, 14017–14024 (2009).

Xu, L., Selin, V., Zhuk, A., Ankner, J. F. & Sukhishvili, S. A. Molecular weight dependence of polymer chain mobility within multilayer films. ACS Macro Lett. 2, 865–868 (2013).

Caruso, F., Niikura, K., Furlong, D. N. & Okahata, Y. 1. Ultrathin multilayer polyelectrolyte films on gold: construction and thickness determination. Langmuir 13, 3422–3426 (1997).

Lvov, Y., Ariga, K., Onda, M., Ichinose, I. & Kunitake, T. A careful examination of the adsorption step in the alternate layer-by-layer assembly of linear polyanion and polycation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 146, 337–346 (1999).

Aulin, C., Varga, I., Claesson, P. M., Wågberg, L. & Lindström, T. Buildup of polyelectrolyte multilayers of polyethyleneimine and microfibrillated cellulose studied by in situ dual-polarization interferometry and quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Langmuir 24, 2509–2518 (2008).

Büchner, K., Ehrhardt, N., Cahill, B. P. & Hoffmann, C. Internal reflection ellipsometry for real-time monitoring of polyelectrolyte multilayer growth onto tantalum pentoxide. Thin Solid Films 519, 6480–6485 (2011).

Advincula, R., Aust, E., Meyer, W. & Knoll, W. In situ investigations of polymer self-assembly solution adsorption by surface plasmon spectroscopy. Langmuir 12, 3536–3540 (1996).

Gu, Y., Weinheimer, E. K., Ji, X., Wiener, C. G. & Zacharia, N. S. Response of swelling behavior of weak branched poly(ethylene imine)/poly(acrylic acid) polyelectrolyte multilayers to thermal treatment. Langmuir 32, 6020–6027 (2016).

Shevchenko, Y., Ahamad, N. U., Ianoul, A. & Albert, J. In situ monitoring of the formation of nanoscale polyelectrolyte coatings on optical fibers using Surface Plasmon resonances. Opt. Express 18, 20409 (2010).

Picart, C. et al. Molecular basis for the explanation of the exponential growth of polyelectrolyte multilayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 99, 12531–12535 (2002).

Baba, A., Kaneko, F. & Advincula, R. C. Polyelectrolyte adsorption processes characterized in situ using the quartz crystal microbalance technique: alternate adsorption properties in ultrathin polymer films. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 173, 39–49 (2000).

Garg, A., Heflin, J. R., Gibson, H. W. & Davis, R. M. Study of film structure and adsorption kinetics of polyelectrolyte multilayer films: effect of pH and polymer concentration. Langmuir 24, 10887–10894 (2008).

Lavalle, P. et al. Direct evidence for vertical diffusion and exchange processes of polyanions and polycations in polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Macromolecules 37, 1159–1162 (2004).

Guzmán, E., Ritacco, H., Rubio, J. E. F., Rubio, R. G. & Ortega, F. Salt-induced changes in the growth of polyelectrolyte layers of poly(diallyl-dimethylammonium chloride) and poly(4-styrene sulfonate of sodium). Soft Matter 5, 2130 (2009).

Menchaca, J., Jachimska, B., Cuisinier, F. & Perez, E. In situ surface structure study of polyelectrolyte multilayers by liquid-cell AFM. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 222, 185–194 (2003).

Enarsson, L.-E. & Wågberg, L. Adsorption kinetics of cationic polyelectrolytes studied with stagnation point adsorption reflectometry and quartz crystal microgravimetry. Langmuir 24, 7329–7337 (2008).

Gilbert, J. B., Rubner, M. F. & Cohen, R. E. Depth-profiling X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of interlayer diffusion in polyelectrolyte multilayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 6651–6656 (2013).

Whitlow, S. J. & Wool, R. P. Diffusion of polymers at interfaces: a secondary ion mass spectroscopy study. Macromolecules 24, 5926–5938 (1991).

Velk, N., Uhlig, K., Vikulina, A., Duschl, C. & Volodkin, D. Mobility of lysozyme in poly(l-lysine)/hyaluronic acid multilayer films. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 147, 343–350 (2016).

Picart, C. et al. Application of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching to diffusion of a polyelectrolyte in a multilayer film. Microsc. Res. Tech. 66, 43–57 (2005).

Peralta, S., Habib-Jiwan, J.-L. & Jonas, A. M. Ordered polyelectrolyte multilayers: unidirectional FRET cascade in nanocompartmentalized polyelectrolyte multilayers. ChemPhysChem 10, 137–143 (2009).

Zhang, Y., Shibru, H., Cooper, K. L. & Wang, A. Miniature fiber-optic multicavity Fabry–Perot interferometric biosensor. Opt. Lett. 30, 1021 (2005).

Warren-Smith, S. C., Kostecki, R., Nguyen, L. V. & Monro, T. M. Fabrication, splicing, Bragg grating writing, and polyelectrolyte functionalization of exposed-core microstructured optical fibers. Opt. Express 22, 29493 (2014).

Shivananju, B. N., Renilkumar, M., Prashanth, G. R., Asokan, S. & Varma, M. M. Detection limit of etched fiber Bragg grating sensors. J. Light. Technol. 31, 2441–2447 (2013).

Mudachathi, R., Shivananju, B. N., Prashanth, G. R., Asokan, S. & Varma, M. M. Calibration of etched fiber Bragg grating sensor arrays for measurement of molecular surface adsorption. J. Light. Technol. 31, 2400–2406 (2013).

Shivananju, B. N., Prashanth, G. R., Asokan, S. & Varma, M. M. Reversible and irreversible pH induced conformational changes in self-assembled weak polyelectrolyte multilayers probed using etched fiber Bragg grating sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 201, 37–45 (2014).

Cranford, S. W., Ortiz, C. & Buehler, M. J. Mechanomutable properties of a PAA/PAH polyelectrolyte complex: rate dependence and ionization effects on tunable adhesion strength. Soft Matter 6, 4175 (2010).

Bieker, P. & Schönhoff, M. Linear and exponential growth regimes of multilayers of weak polyelectrolytes in dependence on pH. Macromolecules 43, 5052–5059 (2010).

Sun, B., Jewell, C. M., Fredin, N. J. & Lynn, D. M. Assembly of multilayered films using well-defined, end-labeled poly(acrylic acid): influence of molecular weight on exponential growth in a synthetic weak polyelectrolyte system. Langmuir 23, 8452–8459 (2007).

Pahal, S., Raichur, A. M. & Varma, M. M. Subdiffraction-resolution optical measurements of molecular transport in thin polymer films. Langmuir 32, 5460–5467 (2016).

Yu, J., Meharg, B. M. & Lee, I. Adsorption and interlayer diffusion controlled growth and unique surface patterned growth of polyelectrolyte multilayers. Polymers 109, 297–306 (2017).

Sill, A., Nestler, P., Azinfar, A. & Helm, C. A. Tailorable polyanion diffusion coefficient in LbL films: the role of polycation molecular weight and polymer conformation. Macromolecules 52, 9045–9052 (2019).

Sill, A. et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayer films from mixtures of polyanions: different compositions in films and deposition solutions. Macromolecules 53, 7107–7118 (2020).

Tompkins, H. G. The Effect of Roughness. In A User’s Guide to Ellipsometry 95–106 (Elsevier, 1993).

Ogieglo, W., Wormeester, H., Eichhorn, K.-J., Wessling, M. & Benes, N. E. In situ ellipsometry studies on swelling of thin polymer films: a review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 42, 42–78 (2015).

Hiller, J. & Rubner, M. F. Reversible molecular memory and pH-switchable swelling transitions in polyelectrolyte multilayers. Macromolecules 36, 4078–4083 (2003).

Pahal, S., Boranna, R., Prashanth, G. R. & Varma, M. M. Simplifying molecular transport in polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 223, 2100330 (2022).

Fujiwara, H. Data Analysis. In Spectroscopic Ellipsometry 147–207 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470060193.ch5.

Acknowledgements

Prashanth G.R. acknowledges financial support from the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) for the award Early Career Research Grant (Sanction No. ECR/2016/000427). Shivananju Bannur Nanjunda acknowledges financial support from the Ministry of Human Resource and Development (Sanction No. 11/9/2019-U.3(A))—Center of Excellence in Biochemical Sensing and Imaging Technologies (CenBioSIm), Ministry of Education (Sanction Number: IOE Phase II projects)—Institute of Excellence in Healthcare and Assistive Technologies, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) (Sanction No. SRG/2022/001874).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.N. and G.R.P. conceived the idea and supervised the experiments. N.P.V. and R.B. carried out the experiments and characterizations. N.P.V., C.T.N., S.P. and R.P.K.J. carried out simulation. G.R.P., S.B.N., N.P.V., R.B. and S.P. wrote the manuscript incorporating inputs from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Rui Min and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naik Parrikar, V., Boranna, R., Pahal, S. et al. Sub-nanometer scale investigation of polyelectrolyte adsorption and desorption processes using etched fiber Bragg grating technique. Commun Chem 8, 208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01602-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01602-2