Abstract

Molecular generation models, especially chemical language model (CLM) utilizing SMILES, a string representation of compounds, face limitations in handling large and complex compounds while maintaining structural accuracy. To address these challenges, we propose the Fragment Tree-Transformer based VAE (FRATTVAE), which treats molecules as tree structures with fragments as nodes. FRATTVAE incorporates several innovative techniques to enhance molecular generation. Molecules are decomposed into fragments and organized into tree structures, allowing for efficient handling of large and complex compounds. Tree positional encoding assigns unique positional information to each fragment, preserving hierarchical relationships. The Transformer’s self-attention mechanism models complex dependencies among fragments. This architecture allows FRATTVAE to surpass existing methods, making it a robust solution that is scalable to unprecedented dataset sizes and molecular complexities. Distribution learning across various benchmark datasets, from small molecules to natural compounds, showed that FRATTVAE consistently achieved high accuracy in all metrics while balancing reconstruction accuracy and generation quality. In molecular optimization tasks, FRATTVAE generated high-quality, stable molecules with desired properties, avoiding structural alerts. These results highlight FRATTVAE as a robust and versatile solution for molecular generation and optimization, making it well-suited for a variety of applications in cheminformatics and drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the fields of drug discovery and materials engineering, there is a demand for efficiently finding chemical compounds with desired molecular properties. To efficiently explore this vast chemical space, computational approaches, such as QSAR models have been used for predicting the activity values of candidate compounds against targets1. However, even when limited to synthesizable small molecules, the number of candidate compounds reaches 1060 2, and predicting the activity values for all compounds in the chemical space takes a considerable amount of time. Therefore, as an alternative approach, molecular generation models that directly generate compound structures with the desired properties through computation have garnered attention3. These models are capable of learning a chemical space reflecting the chemical properties of a set of compounds and then generating a variety of novel compounds based on this learned space.

Various deep molecular generation models have been developed thus far with the aim of constructing chemical latent spaces and computationally generating new compound structures4. In these models, molecules are represented either as strings or graphs. Among the string representations, models that handle molecules as SMILES strings5 utilize model architectures developed in the field of natural language processing, such as LSTM6 and Transformer7, to implicitly learn SMILES grammar and molecular structures. SMILES-based models have been reported to accurately replicate the properties of compounds learned from libraries of compounds8. In general, learning the grammatical rules of SMILES necessitates large datasets. Furthermore, minor changes in SMILES representations can lead to significant alterations in molecular structure9,10.

Graph-based models, on the other hand, can explicitly handle molecular structures. Models like the Constrained Graph VAE11 and Junction Tree VAE (JTVAE)9 ensure the validity of molecules by sequentially generating graph structures. Representing molecules as graphs with fragment nodes prevents the generation of invalid structures9 and reduces the graph size compared to atomic units, thereby shortening learning and generation times. The Non-Autoregressive Graph VAE10 managed datasets containing relatively large molecules like GuacaMol12 by reducing molecular graph sizes through treating common small substructures as single nodes. Moreover, diverse models, such as the Principal Subgraph VAE (PSVAE)13, which automatically discovers key substructures from datasets, and MoLeR14, integrating molecular generation at both atomic and fragment levels, have been proposed. MoLeR demonstrated high performance on molecular optimization benchmark tasks.

The tree structure, a specific type of graph structure that contains no cycles (acyclic graph), has also been actively used in molecular generation in a series of studies, beginning with JTVAE9. The tree structure efficiently represents the branching structures characteristic of compounds. JTVAE has become widely used as a benchmark for molecular generation models due to its high reconstruction accuracy on the ZINC dataset15. While JTVAE is tailored only for small molecules with a molecular weight around 500, Hierarchical VAE (HierVAE)16 showed high reconstruction accuracy in datasets composed of large compounds with repeating structures like polymers by dealing with molecular structures at relatively large fragment units. We previously developed the Natural Product-oriented VAE (NPVAE)17 specifically to manage complex and large molecules, such as natural compounds. The model employs Tree-LSTM18, a variant of RNN, applied to the constructed tree structure for extracting molecular features. Moreover, it incorporates stereostructure prediction, enabling reconstructions and generations that consider the stereochemistry of molecules. Nevertheless, a common problem for these three VAE models is the sequential processing inherent to LSTM, which leads to slower computation speeds and poses challenges in handling large datasets.

Finally, many molecular generation models are of the variational autoencoder (VAE) type, consisting of an encoder and a decoder. VAE models explicitly construct a chemical latent space that embeds molecules into a continuous vector space19. VAE-based models allow molecules to be treated as continuous latent variables, enabling property optimization initiating from any molecule in the latent space20.

In this study, we propose the Fragment Tree-Transformer based VAE (FRATTVAE), a model that handles large-scale and complex compounds while achieving high reconstruction accuracy and generation quality. FRATTVAE processes compounds as tree structures with fragments as nodes, facilitating the handling of stereoisomers and managing molecules with salts and solvents, which are challenging for conventional graph representations. By adopting the Transformer with multi-head attentions of query-key-value type and applying a positional encoding method for tree structures, FRATTVAE resolves the sequential processing issues of LSTM used in models like JTVAE and NPVAE, significantly enhancing molecule generation accuracy and computational speed. While existing VAE models showed significant drops in accuracy for certain evaluation metrics, FRATTVAE consistently achieved high accuracy in reconstruction and several benchmark metrics, including Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD), across five benchmark datasets, ZINC250K15, MOSES8, GuacaMol12, Polymer21, and SuperNatural322, with diverse molecular property distributions. In molecular optimization benchmark tasks, FRATTVAE demonstrated superior performance to state-of-the-art models. The conditional model, Conditional FRATTVAE (C-FRATTVAE), effectively generates molecules with desired properties under multiple conditions. In addition, the Transformer-based model enables GPU massive parallel computations, making large-scale processing possible. Towards constructing a large chemical model, we developed a model trained on 12 million molecules from the entire molecule datasets in ChEMBL23 and DrugBank24, and the PubChem10M dataset used in ChemBERTa25. The total number of parameters in this FRATTVAE model reached 1 billion, illustrating the scalability of our approach.

Overall, FRATTVAE is the first approach to integrate a tree-structured Transformer VAE with fragment-based tokenization, enabling parallel processing of molecular fragments. By doing so, our model captures complex long-range dependencies among fragments while remaining highly scalable. In fact, FRATTVAE’s architecture permits training on unprecedented dataset sizes and generation of much larger, more complex molecules than was previously feasible with earlier fragment- or graph-based VAEs. This unique combination of techniques represents a significant methodological innovation beyond prior works (e.g., JTVAE, NPVAE) that relied on sequential RNN encoders, and it allows FRATTVAE to handle chemical spaces of vastly greater size and complexity.

Results and discussions

High-level overview of FRATTVAE

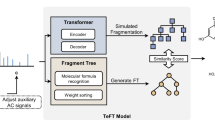

FRATTVAE uses a Transformer-based VAE, as shown in Fig. 1, leveraging the power of the Transformer architecture. FRATTVAE is composed of three main parts: preprocessing, encoder, and decoder.

a Model architecture. This illustrates the architecture of FRATTVAE, showing how molecules are processed as tree structures. Each tree structure is embedded with tree positional encoding and conditions such as molecular weight (MolWt) and logP. The encoder and decoder components utilize multi-head attention and feed-forward layers to process the latent variables for molecular generation. When training the model as a conditional VAE, conditions are provided just before the 〈super root〉. b Generation process. This depicts the molecular generation process in FRATTVAE. Starting from a latent variable, the decoder generates child nodes sequentially, ensuring the proper molecular structure is reconstructed. The process includes handling complex dependencies through the attention mechanism, facilitating the accurate generation of large and complex molecular structures.

- Preprocessing: molecules are decomposed into fragments using predefined rules, organized into tree structures to simplify handling large and complex molecules. Since fragments themselves possess pharmacological activity and physicochemical properties26, preserving their structure enables the capture of the molecule’s properties.

- Positional encoding: the tree structure is encoded using a tree positional encoding method27, which assigns unique positional information to each fragment based on its location within the tree. This encoding is crucial for the Transformer to understand the hierarchical and branching relationships between fragments.

- Token embedding: ECFP28 are used as token embeddings for the fragments. ECFP captures local chemical properties of each fragment, providing rich feature representations for the Transformer model.

- Transformer-based VAE: the core of FRATTVAE consists of an encoder and a decoder (Fig. 1a). The encoder processes the tree structure and obtains a latent variable z of the molecule. The decoder uses this latent variable z to reconstruct the tree structure (Fig. 1b), ensuring the generated molecules maintain chemical validity.

- Training and optimization: the model is trained using a combination of reconstruction loss (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{{recon}}\)) and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{{KL}}\)) as shown in Fig. 1a. This ensures the latent space reflects chemical properties while promoting diversity.

- Conditional FRATTVAE (C-FRATTVAE): This extension allows molecule generation according to given conditions by incorporating molecular properties into both the encoder and decoder during training (Fig. 1a).

Datasets and baselines

To demonstrate adaptability of our FRATTVAE across various datasets, we used five different datasets that vary in the number of molecules and molecular weight (Supplementary Table S1). The KDE plots of property distributions for MolWt (molecular weight), QED (Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness), SA Score29 and NP-likeness30 in each dataset are displayed in Supplementary Fig. S1. For a fair comparison, we adopted the same data splits into training and test for ZINC250K15 and Polymer21 as Jin et al.9,16. MOSES8 and GuacaMol12 are benchmark datasets for evaluating molecular generation. We used the hold-out datasets specified in8,12. For the Natural Products dataset, we selected compounds with a molecular weight over 500 from SuperNatural322 and performed data splitting based on stereochemistry. Consequently, molecules that differ only in stereochemistry are not included in both the training and test sets.

We employed graph-based VAE models such as JTVAE9, HierVAE16, PSVAE13, MoLeR14, NPVAE17, and two SMILES-based VAE, recurrent neural network VAE (named SMIVAE)8,12 and Transformer VAE (named SMITransVAE)31,32. All models were used with their default hyperparameters. Some hyperparameters for SMIVAE were adjusted to accommodate natural compounds in the Natural Products dataset. For some models, publicly available pre-trained models were utilized. Moreover, we modified all models to deterministically generate a unique molecule for a given latent variable z in both generation and reconstruction processes. Additionally, the encoding of molecules was changed to deterministic encoding14.

Distribution learning

In distribution learning, we evaluated whether the model could learn the characteristic distribution of the dataset. The following list of metrics was used for evaluation.

- Reconstruction Accuracy (Recon): this measures the proportion of molecules in the test dataset for which the decoded molecule M′ from the latent variable \({z}_{M}\) of molecule M has SMILES representation that match perfectly with M. Reconstruction accuracy ensures the correspondence between actual molecules and their latent variables.

- Reconstruction Similarity (Similar): this is the average Tanimoto coefficient between molecule M in the test dataset and its decoded counterpart M′.

- Validity: the proportion of generated molecules that are valid. Validity is checked by an RDKit33 molecular structure parser, which verifies valency and consistency of aromatic bonds.

- Uniqueness: the proportion of unique molecules among the valid generated molecules. A low value indicates that the model is collapsing, generating only a few typical molecules.

- Novelty: the proportion of valid generated molecules that do not exist in the training dataset. A low value may indicate overfitting.

- FCD34: This metric detects whether the generated molecules are diverse and have similar molecular properties to those in the test data. Particularly, FCD allows for the evaluation of how well the model captures the chemical and physiological characteristics and distribution of the given dataset. A similar molecular property distribution results in a low FCD. Following previous research12, we calculated the final FCD score S as:

This scale transforms FCD to a value between 0 and 1, where a higher value indicates closer property distribution.

- KL Divergence (KL-Div.): this measures the KL divergence of physicochemical properties between the generated molecules and test data, calculated from physicochemical descriptors such as molecular weight, the number of aromatic rings, and the count of rotatable bonds. Similar to FCD, values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating closer physicochemical properties between the generated molecules and the test data.

- logP: Represents the lipophilicity of a molecule. A moderate lipophilicity is required for pharmaceutical compounds.

- QED: an indicator representing the drug-likeness of a molecule. Since it is calculated based on existing oral drugs, it can be considered an indicator of oral drug-likeness. It is expressed as a value between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating structures that are more like oral pharmaceuticals35.

- NP-likeness: a measure of naturalness. NP-likeness score is a measure designed to estimate how closely a given molecule resembles known natural products30.

For these three metrics (logP, QED, and NP-likeness), we used the 1D Wasserstein-1 distance between the metric distributions of the generated and test sets, rather than their absolute values.

- SAscore: a score representing the difficulty of synthesis based on molecular structure. It is expressed as a value between 1 and 10, with values closer to 10 indicating higher synthesis difficulty29.

All metrics except Novelty were calculated using valid generated compounds. For all models, generated compounds were produced by randomly sampling 10,000 latent variables from a Gaussian distribution \(N(0,I)\). This process was repeated five times to calculate the average for each metric.

All results of distribution learning for each method across five benchmark datasets are shown in Table 1. (Since each score in Table 1 represents the average obtained from 10,000 trials, we have provided a separate table (Supplementary Table S2) showing both the means and standard deviations.) In the two benchmark datasets, MOSES and GuacaMol, FRATTVAE surpassed existing methods in almost all metrics, especially in terms of FCD. The primary goal of a molecular generation model is to create novel molecules with properties similar to those learned, making FCD particularly important. The FCD scores of two SMILES-based VAE, SMIVAE and SMITransVAE, are extremely low. JTVAE, HierVAE, and NPVAE were unable to handle diverse and large datasets like GuacaMol due to several errors and their high computational costs. Furthermore, SMIVAE has fallen into a posterior collapse36, limiting its ability to generate only a restricted set of molecules. On the other hand, SMITransVAE exhibited very high reconstruction accuracy scores, but its validity and FCD scores were extremely low. Since, as mentioned earlier, all metrics except Novelty were calculated using only valid generated molecules, the notably poor validity and FCD performance of SMITransVAE make a direct comparison based solely on reconstruction accuracy and related metrics inappropriate. In particular, FCD serves as the most representative metric for evaluating distribution learning quality, further highlighting the limitation of comparing SMITransVAE to models with significantly higher validity. Among models with high validity, FRATTVAE achieved the highest reconstruction accuracy. Additionally, on the GuacaMol dataset and the Natural Products dataset discussed below, FRATTVAE notably achieved more than an order-of-magnitude higher accuracy in terms of SA score and NP-likeness compared to all other methods. This clearly demonstrates that, by generating molecules through combinations of known chemical fragments, FRATTVAE inherently produces chemically reasonable and more readily synthesizable structures, while simultaneously preserving natural product-like characteristics. We also computed properties distribution for traditional drug-likeness properties, QED and logP scores, between generated and test sets to assess their real-world relevance. FRATTVAE’s generated molecules have property distributions that closely match those of the real test compounds, indicating our model does not produce outlier molecules in terms of drug-likeness or lipophilicity.

In the Polymer dataset and the Natural Products dataset, which include relatively large molecules, FRATTVAE achieved reconstruction accuracy and FCD that surpassed existing methods. Many models, including SMITransVAE are unable to handle the massive molecules contained in the Natural Products. In the Polymer dataset, FRATTVAE significantly outperformed HierVAE and NPVAE in terms of reconstruction accuracy. In the Natural Products dataset, FRATTVAE surpassed SMIVAE in all metrics except Uniqueness, and particularly excelling in reconstruction similarity. Natural compounds, which are produced through biological processes, often have novel structures and exhibit high biological activity37,38. Indeed, two-thirds of the small molecule drugs approved between 1981 and 2019 are derived from natural compounds and are widely utilized as pharmaceuticals39. Moreover, with the publication of extensive natural compound databases, such as COCONUTS40 and SuperNatural322, there is a growing expectation for the development of cheminformatics approaches tailored to natural compounds30. FRATTVAE has demonstrated its capability to manage not only structurally homogeneous molecules like polymers but also heterogeneous structures such as natural compounds.

Lastly, we also conducted comparisons on the ZINC250K dataset, which consists of small molecular weight compounds and is most commonly used as a benchmark dataset in existing methods. FRATTVAE demonstrated results comparable to the top-ranked existing methods in all metrics, except for the reconstruction accuracy of SMITransVAE, as discussed above (Reconstruction accuracy and similarity considering stereostructures (3D) are shown in Supplementary Table S3). In terms of FCD, FRATTVAE’s performance is nearly equivalent to MoLeR and significantly surpasses JTVAE, successfully achieving both high reconstruction accuracy and FCD. Additionally, C-FRATTVAE, a model trained with conditions including molecular weight, logP, SA score29, QED35, NP-likeness30, and TPSA, demonstrated performance equivalent to FRATTVAE even in random sampling.

The total number of unique fragment types extracted for each dataset is listed in Supplementary Table S4. As expected, the Natural Products set has the highest number of fragment types per molecule (due to very diverse structures), while the Polymer set has the lowest (due to repetitive units). This underscores that Natural Products are structurally heterogeneous, whereas Polymers are relatively homogeneous. FRATTVAE proved effective across this spectrum, handling small molecules up to very large natural compounds with equal ease.

Conditional Generation

We developed a conditional model, Conditional FRATTVAE (C-FRATTVAE), which simultaneously incorporates multiple conditions such as molecular weight, logP, SA score, QED, NP-likeness, and TPSA, and evaluated its generation capabilities. The dataset used was ZINC250K. We input 10,000 randomly sampled latent variables along with specified property values into the decoder to generate molecules. Furthermore, to demonstrate the capability to generate molecules aligned with multiple properties, we generated 10,000 molecules under conditions combining molecular weight, logP, QED, and the SA score.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of properties of the molecules generated when each property is given as a condition. Originally, since ZINC250K is composed of compounds with a limited range of properties, conditional generation is challenging. Nevertheless, it was generally possible to generate molecules in accordance with the conditions. Notably, it was possible to generate molecules with larger molecular weights and lower QEDs that are not typically found in ZINC250K. In the generation under multiple conditions, it was observed that distributions aligned with each condition were generated accordingly (Fig. 2b).

a Distribution of properties for molecules generated under a single condition. The red color represents the distribution of the training dataset, ZINC250K. b Distribution of properties for molecules generated under multiple conditions. This includes two-dimensional KDE plots with SA Score on the vertical axis and MolWt (molecular weight), logP, or QED on the horizontal axis respectively.

Property Optimization

We next evaluated the model’s ability to optimize molecular properties, in line with previous studies9,13. In these tasks, the goal is to generate molecules that maximize a given property (or properties), such as drug-likeness or an adjusted logP. Specifically, we considered two single-property optimization objectives on the ZINC250K dataset: maximizing QED and maximizing Penalized logP (PlogP)41. QED is a drug-likeness metric bounded between 0 and 1 (higher is more drug-like). PlogP is defined as the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) of a molecule penalized by undesirable structural features – notably, it subtracts penalties for poor synthetic accessibility and the presence of large ring systems. As a result, PlogP has no fixed upper or lower limit (very difficult or unsynthesizable molecules will receive large negative penalties). We trained all models on ZINC250K (as in the distribution learning task) for this experiment. We selected PSVAE and MoLeR as baseline models for comparison in these optimization tasks.

To perform molecule optimization, we used the Molecule Swarm Optimization (MSO) method20, which is designed to optimize a molecule by navigating in the model’s continuous latent space (it is a variant of particle swarm optimization applied to molecule generation). For each property objective, we ran MSO for 100 iterations with a swarm of 100 particles (each particle being a candidate latent point that the algorithm refines). In total. this yields up to 10,000 optimized molecules per model and objective. We started each optimization with an initial seed molecule (benzene in our case) and allowed latent vectors to explore within a range of [-2, 2] in each dimension. Additionally, we constructed a conditional variant, C-FRATTVAE, that was trained to accept the property value as an input; for this model, we could generate molecules by simply setting the condition to an extreme value (QED = 1 or PlogP=20, in this case) without needing MSO.

The top three optimized molecules (highest-scoring) from each model for QED and PlogP are shown in Table 2. (The SMILES strings and compound structures of these top three molecules are provided in Supplementary Table S9.) All methods achieved high QED values for their top solutions, and FRATTVAE’s best molecules were comparable to those from C-FRATTVAE, PSVAE, and MoLeR in QED. In the PlogP optimization, however, FRATTVAE and C-FRATTVAE found molecules with dramatically higher PlogP scores than the baselines. FRATTVAE’s top PlogP molecules had values around 16–17, and C-FRATTVAE (leveraging the property condition during generation) achieved even higher PlogP around 20–21 for its best molecules. By contrast, PSVAE and MoLeR only reached PlogP around 5–9. This is striking given that the ZINC250K training set contains very few compounds with such high logP. It appears that by using fragment combinations (especially adding hydrophobic ring structures and long carbon chains), FRATTVAE can make large leaps in logP in a single generation step, whereas atom-level models have difficulty exploring those modifications. Indeed, by conditioning on the property, C-FRATTVAE was able to significantly improve logP while still maintaining reasonable QED in its outputs.

We focused on PSVAE and MoLeR as baselines in these optimization tasks because they represent state-of-the-art deep generative models for molecular optimization. Based on previously reported results in the literature, PSVAE is known to achieve higher accuracy than JTVAE and HierVAE for property optimization. Furthermore, the MSO method requires iterative evaluations of the model to search for optimal solutions, making it computationally infeasible to apply models with high computational costs, such as JT-VAE and HierVAE. Therefore, we excluded JTVAE and HierVAE from this comparison.

GuacaMol goal-directed optimization

We further evaluated FRATTVAE on the 20 challenging goal-directed optimization tasks from the GuacaMol benchmark suite, which are designed to reflect real-world virtual screening objectives. Each task specifies a particular goal (e.g., rediscovering a known drug given its structure or properties, optimizing multiple properties simultaneously, etc.) and yields a score between 0 and 1 for candidate molecules, with higher scores meaning better achievement of the goal. We applied MSO for these tasks in a similar manner as above, using the models trained on the GuacaMol dataset in the distribution-learning stage. For these experiments, we included MoLeR as a baseline (PSVAE was excluded here due to its very high computational cost on these large tasks). Following prior studies14,20, we used 200 particles over 250 iterations for MSO in each task, with initial seed molecules randomly selected from the GuacaMol dataset (with 40 trials and an exploration range of [-2, 2]).

In addition to the raw goal score, we measured the “Quality” of the top 100 optimized molecules for each task using the GuacaMol medicinal chemistry filter for structural alerts12. This filter flags molecules containing certain undesirable substructures that are known to be unstable, reactive, or likely to produce toxic metabolites. The Quality metric is the fraction of top molecules that pass this filter (i.e., have no structural alerts), and provides an indication of synthesizability/tractability of the optimized compounds.

The results for all 20 tasks are summarized in Table 3. FRATTVAE outperformed MoLeR on 12 of the 20 tasks, often by a substantial margin, and achieved a higher overall average score across all tasks. In particular, our model excelled in the rediscovery tasks (where the goal is to generate a specific known drug molecule) and the similarity tasks (where the goal is to generate molecules structurally similar to a given drug while improving certain properties). FRATTVAE also performed strongly on the multi-property optimization (MPO) tasks, which require balancing several properties simultaneously – it often found a better compromise than MoLeR between optimizing properties like logP or TPSA and maintaining structural similarity to known pharmaceuticals.

A common challenge in unconstrained optimization is that methods may exploit the scoring function by proposing chemically bizarre or unsynthesizable structures that achieve high scores. We observed that MoLeR’s top solutions sometimes included such problematic structures. Using the structural alert filter to evaluate Quality, FRATTVAE’s optimized molecules had a consistently higher filter pass rate than MoLeR’s (see Table 3, “Quality” column). For example, when optimizing specific objectives, about 22% of the top molecules from FRATTVAE were flagged by the filter, compared to 35% for MoLeR. We investigated the source of these alerts: in our fragment-based approach, any alerts present in generated molecules largely stem from the original fragment library rather than novel problematic substructures created by the model. Indeed, we found that about 26% of the fragments in our library (for GuacaMol) contain an alert substructure, and among all the optimized molecules flagged by the filter, only 7 molecules (out of 312 flagged) had an alert that was not already present in at least one fragment. In other words, FRATTVAE did not invent new toxic motifs; the few alerts in its outputs were inherited from the building blocks. This behavior contrasts with atom-level models that might assemble entirely new problematic configurations. To further validate this, we computed the Synthetic Accessibility (SA) scores for molecules optimized by FRATTVAE versus a MoLeR. We found that FRATTVAE’s top solutions had better synthetic feasibility: the average SA score of the top 100 molecules optimized by FRATTVAE was lower (indicating easier synthesis) than that of MoLeR. Overall, because FRATTVAE builds molecules by combining chemically reasonable fragments, it tends to generate compounds that are inherently more realistic and synthetically accessible. This is reflected in the high Quality scores of FRATTVAE’s optimized molecules, indicating fewer “structural alert” functionalities compared to the baseline.

While our comparative analysis focused on deep generative models, there are also non-neural approaches to molecular optimization, such as Graph GA and CReM. Graph GA (a genetic algorithm approach)12 and CReM (a rule-based fragment mutation method)42 have shown very strong performance on certain GuacaMol tasks, often achieving top scores by brute-force search. However, unlike our method (and the generative model baselines we chose), which aim to generate molecules exhibiting similar characteristics to their training datasets, these methods operate with fundamentally different trade-offs and are not directly comparable to VAE-based models. A rigorous head-to-head comparison with such heuristic methods is beyond our scope, but we have included literature-reported scores of Graph GA and CReM in the context of GuacaMol benchmark tasks as Table 3. In general, our focus was to demonstrate FRATTVAE’s advantages over other learning-based models; nonetheless, Graph GA and CReM represent complementary strategies for goal-directed molecule generation.

Computational time of FRATTVAE

We compared the computational efficiency of FRATTVAE to other graph-based VAE models (PSVAE, MoLeR, NPVAE) in terms of preprocessing, training, and sampling (generation) speed. Following prior reports13,14, we know JTVAE and HierVAE are significantly slower and less scalable, so we did not include them in the computational time comparison. Table 4 reports the time per molecule for each stage (preprocessing, training, and generation) on three datasets of different sizes (ZINC250K, MOSES, Polymer), measured on the same hardware. FRATTVAE was dramatically faster than all baseline models in the preprocessing and training stages. This is attributable to our parallelized fragment processing and the Transformer’s ability to utilize GPU acceleration fully. In the generation stage, FRATTVAE was slightly slower than MoLeR on the small molecule datasets (ZINC250K and MOSES), but still more than twice as fast as PSVAE, and it did not slow down as dataset size increased (unlike PSVAE, whose generation speed dropped on the larger MOSES set). NPVAE was too computationally demanding to evaluate on ZINC or MOSES at all. In the Polymer dataset (with much larger molecules), FRATTVAE outperformed all models in every stage, including generation. These results indicate that FRATTVAE’s design is not only accurate but highly scalable and efficient for large-scale use. Crucially, FRATTVAE’s Transformer architecture allows massive parallelization, giving it a clear advantage in scalability. We were able to train an extraordinarily large instance of FRATTVAE—with 1 billion parameters—on a dataset of over 12 million molecules (see below), a scale far beyond what previous graph-based VAEs have achieved. This parallelism means FRATTVAE can explore chemical space orders of magnitude faster than models with sequential generation processes, effectively opening the door to generative modeling on the entirety of available chemical space. Such computational scalability is a practical benefit for drug discovery workflows that require training on very large libraries or need to generate and evaluate millions of compound candidates quickly.

Towards large-scale learning model

To explore the benefits of scaling up our approach, we trained a larger FRATTVAE model—named “FRATTVAE-large”—on a combined dataset of 12,250,314 unique molecules (comprising ~2.40 million molecules from ChEMBL23, 11.6 thousand from DrugBank24, and 10.0 million from the PubChem10M subset used in ChemBERTa25, after removing duplicates). This large-scale model contains roughly 1.03 billion parameters and incorporates ~1.2 million unique fragment types – far exceeding the fragment count in any single benchmark dataset used previously (see Supplementary Table S4). We trained the FRATTVAE-large model for 420 epochs; training loss and label accuracy curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. (Here, “label accuracy” refers to the percentage of fragment labels correctly predicted by the decoder during training, analogous to next-character prediction accuracy in language models.) The trained model parameters are publicly available on our GitHub repository.

As summarized in the Supplementary Table S5, the large-scale FRATTVAE model exhibited substantial improvements on several specific GuacaMol goal-directed optimization tasks (e.g., Troglitazone rediscovery improved from 0.817 to 1.000, Deco Hop from 0.935 to 0.975, and Scaffold Hop from 0.880 to 0.922), clearly demonstrating the benefits of large-scale training. However, improvements on other tasks were more modest, and performance slightly decreased in certain cases. Consequently, the overall average score increased only marginally (from 0.772 to 0.775). These results indicate that while the large-scale FRATTVAE model provides substantial gains for specific objectives, the average overall enhancement remains incremental.

Conclusion

FRATTVAE consistently demonstrated superior reconstruction accuracy and FCD across all datasets, matching or surpassing existing methods. This high reconstruction performance indicates that the model successfully constructs a rich latent space capturing essential molecular structural information. By utilizing tree-structured representations and tokenizing fragments with ECFP, FRATTVAE efficiently captures both local and global features of molecules, proving effective for a wide variety of compound types – from small drug-like molecules to very large natural products.

In property optimization tasks, FRATTVAE (and its conditional variant C-FRATTVAE) performed exceptionally well, particularly for improving PlogP, despite the training data lacking molecules with extreme logP. The fragment-level representation allowed the model to make significant structural modifications in a single step (for example, adding or expanding ring systems and alkyl chains), which led to much larger logP increases than atomic-level models could achieve. Moreover, FRATTVAE’s fragment-based approach enabled faster convergence in optimization, highlighting its practicality for tasks requiring substantial structural changes.

In the GuacaMol goal-directed benchmark, FRATTVAE excelled in rediscovery, similarity, and MPO tasks, outperforming a leading baseline (MoLeR) in most cases. The latent space learned by FRATTVAE exhibits a strong correspondence between latent variables and molecular properties, enabling effective navigation for optimization. Importantly, the model was able to balance improving target properties (like logP or TPSA) while maintaining structural similarity to known drugs, which is crucial for realistic drug discovery scenarios.

A key advantage of FRATTVAE is its scalability and practical applicability. Thanks to the Transformer architecture and fragment-based design, FRATTVAE can be trained on extremely large datasets and handle molecules of unprecedented size and complexity – a feat that was previously infeasible for generative models. We showed that a 1-billion-parameter FRATTVAE trained on 12 million molecules can generalize to smaller benchmarks and difficult optimization tasks, underscoring its ability to operate at both small and ultra-large scales. This combination of accuracy, scalability, and versatility positions FRATTVAE as a next-generation model for cheminformatics. In conclusion, FRATTVAE provides a versatile and powerful approach to molecular generation and optimization, outperforming prior methods in both distribution-learning and property-directed tasks. Its use of a Transformer with fragment tokenization enables chemical space exploration at a new scale, poising FRATTVAE to become a new benchmark for molecular generative models and to enable discovery campaigns that were previously impractical. Future work may explore even larger datasets, additional conditioning factors, and further improvements in computational efficiency to expand the horizons of data-driven molecular design.

Material and methods

Model architecture of FRATTVAE

FRATTVAE is a VAE built around a tree-transformer architecture (Fig. 1). It consists of an encoder that maps a fragment tree to a continuous latent vector, and a decoder that reconstructs a fragment tree from a latent vector. Both encoder and decoder are based on the Transformer sequence model7, adapted to handle tree-structured fragment sequences. The overall structure of FRATTVAE is shown in Fig. 1. FRATTVAE is composed of three main parts: preprocessing, encoder, and decoder. In preprocessing, compounds are decomposed into fragments and transformed into the corresponding tree structure. A positional encoding method for tree structures27 is then used to encode the position of each node within the tree, enabling the application of the Transformer. The encoder encodes the compounds into latent variables z, and the decoder uses the latent variables z as input to generate the tree structure in a depth-first manner.

Preprocessing: fragment tokenization and embedding using ECFP

In preprocessing, molecules are represented as a tree structure with fragments as nodes17. Initially, molecules are decomposed into fragments according to decomposition rules. We used BRICS43 for the fragmentation rules. BRICS is a method of breaking bonds based on retrosynthetic chemistry, thus, it is expected that molecules reconstructed from fragments will be easier to be synthesized. In addition, to limit the number of unique fragments, ring structures and substituent bonds were also considered as cleavage sites, similar to previous studies9,15. The identified bonds are cleaved, and the cleaved sites are capped with a dummy atom ‘*’. Additionally, dummy atoms carry information on connection order and chirality, enabling the reconstruction of some stereostructures (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Each fragment is stored as a unique fragment label, and fragments with different connection points are saved under different labels. Molecules are decomposed using this method and structured into a tree structure with fragments as nodes. Each node is assigned the ECFP28 value of its fragment as a feature. In other words, ECFP is used as the token embedding for fragments. The root node of each tree structure is determined based on CANGEN algorithm of RDKit33, meaning the priority of each atom is determined by valency and atomic number, and the fragment containing the atom with the highest priority is uniquely identified as the root node. Furthermore, this model accommodates molecules containing difficult-to-handle elements in standard graph representations, such as metal ions and solvents (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Therefore, it can handle almost all molecules, regardless of the types or number of atoms they contain. The hyperparameters for preprocessing in FRATTVAE is shown in Supplementary Table S6.

Tree positional encoding

In the Transformer, the position information of input data is represented by positional encoding. To handle tree structures with the Transformer, we adopted the tree positional encoding developed by Shiv et al.27. This positional encoding method is intended for handling directed trees with ordered child nodes and can be applied to the fragment tree representations in this study. If the degree of each node (the maximum number of child nodes) is n and the depth is k in the tree, then the positional encoding for each node is represented by a vector of dimensions n × k. When the ith child of node A is denoted \({A}_{i}\), its positional encoding, \({{pos}}_{{A}_{i}}\), is expressed as follows:

Here, \({e}_{i}^{n}\) is an n-dimensional one-hot vector where the ith dimension is 1. \({{pos}}_{A}\left[:-n\right]\) represents the vector from the 1st dimension to the n × (k-1)th dimension of the positional encoding posA of node A. Thus, by truncating the last \(n\) elements from posA, the positional encoding is consistently maintained at n × k dimensions. Thus, the positional encoding of n × k dimensions functions like a pushdown stack. The positional encoding of the root node \(R\) is initialized as the zero vector \({0}_{n\times k}\). An example of tree positional encoding when the degree of the tree is \(n=2\) and the depth is \(k=3\) is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S3. Furthermore, this positional encoding can be parameterized as follows to enable learning of the positional encoding:

Here, \({p}_{n}\) is an \(n\) -dimensional learnable parameter. Unlike conventional positional encoding, during generation, it is necessary to dynamically compute the positional encoding each time a label for the next node is predicted. Therefore, the partially constructed subtree structure is maintained, and information about the parent node of the predicted label is preserved. Finally, this method deals with trees where each parent node has a fixed number of children. Therefore, we predetermined \(n\) and \(k\), and all fragment trees were positionally encoded as \(n\)-ary trees of depth \(k\).

Transformer-based VAE

In the field of natural language processing, several VAE models based on the Transformer have been proposed. Biesner et al44. integrate the token vectors of each word from a Transformer encoder using an RNN to obtain a single latent variable. On the other hand, Ok et al45. encodes the token vector of the sentence representation into a latent variable through a simple linear layer. Since sequential processing with RNNs undermines the advantage of parallel processing offered by the Transformer, our model is based on the approach of Ok et al. to construct the VAE model. The model hyperparameters in FRATTVAE is shown in Supplementary Table S7.

Encoder

In the encoder, the fragment tree is encoded into the latent variable \(z\). The encoder is implemented as a model that adds a fully connected layer to the standard Transformer Encoder to encode to the normally distributed latent variable \(z\). The fragment tree is input to the encoder with the special node at the top of the fragment tree, denoted 〈super root〉. The 〈super root〉 possesses a learnable feature vector \({x}_{{root}}\) and aggregates the entire structural information of the input molecule through attention with 〈super root〉, representing the molecule with a single latent variable. Each node in the fragment tree has an ECFP feature vector x and positional encoding pos. When the molecule has L fragments, the processing in the encoder is represented by the following equations:

Here, \({W}^{x}\) and \({b}^{x}\) represent the learnable weights and bias of the fully connected layer, and \({h}_{{root}}\) is the embedding representation of 〈super root〉. From this \({h}_{{root}}\), the latent variable \(z\) is calculated:

Here, \({W}^{\mu }\) and \({W}^{\sigma }\) are the weights of the fully connected layer, \({b}^{\mu }\) and \({b}^{\sigma }\) are the biases, and \(\epsilon\) is random noise from the standard normal distribution \(N(0,I)\).

Decoder

In the decoder, the latent variable \(z\), the 〈super root〉, and the subtree up to time \(t-1\) are input to predict the fragment label \({F}_{t}\) at time t. The decoder is implemented as a model that has modified the source-target Attention layer in the Transformer decoder to a latent-target attention layer. In the latent-target attention layer, the latent variable \(z\) is converted into key and value, and the decoder input serves as the query to compute the attention. This layer tightly links the latent space with the decoder, enabling generation aligned with the latent space. The input to the decoder initially includes the 〈super root〉, shared with the encoder. Similarly, each fragment also has an ECFP feature vector \(x\) and positional encoding \({pos}\). When the molecular latent variable is \(z\), the processing in the decoder is represented by the following equations:

Here, \({W}^{m}\) and \({b}^{m}\) represent the weights and bias of the fully connected layer, respectively. Equation (15) represents a fully connected layer that aligns the embedding dimension of the Transformer with the dimension of the latent variable. This allows the dimensions of the latent variable to be reduced without reducing the size of the Transformer model.

Training

In the training of the model, the fragment tree is input in parallel to both the encoder and decoder. In the decoder input, masking is applied to prevent referencing inputs after time \(t-1\) when predicting the fragment at time t. The loss function is a weighted sum of the cross-entropy loss (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{{recon}}\)), calculated from the predicted labels and the true labels, and the KL divergence (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{{KL}}\)), which measures the distance between the distribution of the latent variables and a normal distribution. When the predicted label is \(y\), the true label is \(\hat{y}\), the mean of the latent variable distribution is \(\mu\), and the variance is \({\sigma }^{2}\), the loss function \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}\) is expressed as follows:

Here, \({w}_{r}\) and \({w}_{{kl}}\) are the weights applied to the cross-entropy loss and KL divergence, respectively. The training conditions are detailed in Supplementary Table S8.

Generation

In the generation process, the latent variable \(z\) and 〈super root〉 are input, and fragment labels are sequentially generated to construct the tree structure in a depth-first manner (Fig. 1b). The latent variable \(z\) is randomly sampled from the standard normal distribution \(N(0,I)\). At time 0, the 〈super root〉 is input into the decoder to predict the fragment \({F}_{1}\) at time 1. Since fragment \({F}_{1}\) serves as the root node, its positional encoding is initialized as the zero vector \({0}_{n\times k}\). Next, both the 〈super root〉 and \({F}_{1}\) are input into the decoder to predict the fragment \({F}_{2}\). Fragment \({F}_{2}\), as a child node of \({F}_{1}\), has its positional encoding calculated. This process is repeated until no nodes have child nodes left or a 〈pad〉 is predicted. Finally, the generated fragment tree is converted into a molecule.

Conditional VAE

Conditional VAE (CVAE)46 is an extension of the VAE model that enables the generation of molecules according to given conditions, such as molecular properties. CVAE accomplishes this by incorporating molecular properties as conditions into both the encoder and decoder during training. Each condition is converted into a vector with the model’s embedding dimension via a fully connected layer and is added before the 〈super root〉 (Fig. 1a). Through attention between conditions and molecules, the properties are reflected in the latent variables. During generation, desired conditions are added to the decoder side, allowing for generation according to the specified conditions.

Molecular optimization

In molecular optimization, the molecular structure is optimized to improve properties and activities. Several benchmark optimization tasks were conducted using the optimization method MSO20. MSO applies a heuristic optimization method termed particle swarm optimization (PSO) to molecules, optimizing the latent variable \(z\) based on the objective function f within a continuous chemical latent space. PSO is a probabilistic optimization method that utilizes the principles of swarm intelligence to identify an optimal point within a given search space, as determined by a specific objective function. This technique involves a group of agents, referred to as particles, which navigate through the search space. The update equations for the ith latent variable \({z}_{i}\) in the particle swarm at iteration \(k\) are as follows:

Here, \({z}^{{best}}\) is the best point for particle \({z}_{i}\) at iteration \(k\), and \({z}^{{best}}\) is the best point among the entire particle swarm. \(w\) is a constant that controls the change in latent variables from the previous iteration, \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\) are weights for the contributions of individual and collective experiences, and \({r}_{1}\) and \({r}_{2}\) are random numbers from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. The optimized latent variable \({z}^{{best}}\) is decoded to generate a molecule with the desired properties. Default values were used for the hyperparameters \(w\), \({c}_{1}\), and \({c}_{2}\) in MSO.

Data availability

All datasets used in this study can be obtained by following the instructions provided at https://github.com/slab-it/FRATTVAE. The source data for the graphs in Fig. 2 are available as Supplementary Data.

Code availability

The source code for the implementation of FRATTVAE is available at https://github.com/slab-it/FRATTVAE.

References

Rifaioglu, A. S. et al. Recent applications of deep learning and machine intelligence on in silico drug discovery: methods, tools and databases. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1878–1912 (2019).

Bohacek, R. S., McMartin, C. & Guida, W. C. The art and practice of structure-based drug design: a molecular modeling perspective. Med. Res. Rev. 16, 3–50 (1996).

Skinnider, M. A. et al. Chemical language models enable navigation in sparsely populated chemical space. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 759–770 (2021).

Pang, C., Qiao, J., Zeng, X., Zou, Q. & Wei, L. Deep Generative models in de novo drug molecule generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model 64, 2174–2194 (2024).

Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput Sci. 28, 31–36 (1988).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. (NIPS, 2017).

Polykovskiy, D. et al. Molecular sets (MOSES): a benchmarking platform for molecular generation models. Front Pharm. 11, 565644 (2020).

Jin, W., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Junction tree variational autoencoder for molecular graph generation. Proc. Int. Mach. Learn. 80, 2323–2332 (2018).

Kwon, Y., Lee, D., Choi, Y. S., Shin, K. & Kang, S. Compressed graph representation for scalable molecular graph generation. J. Cheminform. 12, 58 (2020).

Liu, Q., Allamanis, M., Brockschmidt, M. & Gaunt, A. Constrained graph variational autoencoders for molecule design. In: Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS, 2018).

Brown, N., Fiscato, M., Segler, M. H. S. & Vaucher, A. C. GuacaMol: benchmarking models for de novo molecular design. J. Chem. Inf. Model 259, 1096–1108 (2019).

Kong, X., Huang, W., Tan, Z. & Liu, Y. Molecule generation by principal subgraph mining and assembling.Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 2550–2563 (2022).

Maziarz K., et al. Learning to extend molecular scaffolds with structural motifs. In Proc. of the 10th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2022).

Sterling, T. & Irwin, J. J. ZINC 15 - Ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model 55, 2324–2337 (2015).

Jin, W., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Hierarchical generation of molecular graphs using structural motifs. Proc. 37th Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 119, 4839–4848 (2020).

Ochiai, T. et al. Variational autoencoder-based chemical latent space for large molecular structures with 3D complexity. Commun. Chem. 6, 249 (2023).

Tai, K. S., Socher, R. & Manning, C. D. Improved semantic representations from tree-structured long short-term memory networks. In Proc. of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. (ACM, 2015).

Gómez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 268–276 (2018).

Winter, R. et al. Efficient multi-objective molecular optimization in a continuous latent space. Chem. Sci. 10, 8016–8024 (2019).

St John, P. C. et al. Message-passing neural networks for high-throughput polymer screening. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 234111 (2019).

Gallo, K. et al. SuperNatural 3.0-a database of natural products and natural product-based derivatives. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D654–D659 (2023).

Gaulton, A. et al. The ChEMBL database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D945–D954 (2017).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2018).

Chithrananda, S., Grand, G. & Ramsundar, B. ChemBERTa: large-scale self-supervised pretraining for molecular property prediction. Machine Learning for Molecules Workshop, NeurIPS (2020). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.09885 (2020).

Bissantz, C., Kuhn, B. & Stahl, M. A medicinal chemist’s guide to molecular interactions. J. Med Chem. 53, 5061–5084 (2010).

Shiv, V. & Quirk, C. Novel positional encodings to enable tree-based transformers. In: Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS, 2019).

Rogers, D. & Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model 50, 742–754 (2010).

Ertl, P. & Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminform. 1, 8 (2009).

Chen, Y. & Kirchmair, J. Cheminformatics in natural product-based drug discovery. Mol. Inf. 39, e2000171 (2020).

Dollar, O., Joshi, N., Beck, D. A. C. & Pfaendtner, J. Attention-based generative models for de novo molecular design. Chem. Sci. 12, 8362–8372 (2023).

Flam-Shepherd, D., Zhu, K. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Language models can learn complex molecular distributions. Nat. Commun. 13, 3293 (2022).

Landrum G. and Others. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software. https://www.rdkit.org/ (2016).

Preuer, K., Renz, P., Unterthiner, T., Hochreiter, S. & Klambauer, G. Fréchet chemnet distance: a metric for generative models for molecules in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model 58, 1736–1741 (2018).

Bickerton, G. R., Paolini, G. V., Besnard, J., Muresan, S. & Hopkins, A. L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 4, 90–98 (2012).

Bowman, S. R. et al. Generating sentences from a continuous space. In Proc. 20th SIGNLL Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning (CONLL, 2016).

Rodrigues, T., Reker, D., Schneider, P. & Schneider, G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat. Chem. 8, 531–541 (2016).

Kakeya, H. Natural products-prompted chemical biology: phenotypic screening and a new platform for target identification. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 648–654 (2016).

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 770–803 (2020).

Sorokina, M., Merseburger, P., Rajan, K., Yirik, M. A. & Steinbeck, C. COCONUT online: collection of open natural products database. J. Cheminform. 13, 2 (2021).

Kusner, M. J., Paige, B. & Hernández-Lobato, J. M. Grammar variational autoencoder. In Proc of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning. (ICML, 2017).

Polishchuk, P. CReM: chemically reasonable mutations framework for structure generation. J. Cheminform. 12, 28 (2020).

Degen, J., Wegscheid-Gerlach, C., Zaliani, A. & Rarey, M. On the art of compiling and using ‘drug-like’ chemical fragment spaces. ChemMedChem 3, 1503–1507 (2008).

Biesner, D., Cvejoski, K. & Sifa, R. Combining variational autoencoders and Transformer language models for improved password generation. In Proc. of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. 1-6 (ICARS, 2022).

Ok, C., Lee, G. & Lee, K. Informative language encoding by variational autoencoders using transformer. Appl Sci. 12, 7968 (2022).

Kingma, D. P., Mohamed, S., Jimenez Rezende, D. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised learning with deep generative models. In: Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS, 2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Area (A) “Latent Chemical Space” [23H04885, and 23H04880] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I.: implemented the software, analysed data, and compared with the existing methods. A.Y.: trained on large datasets and analysed data. M.A.: analysed models and data. Y.S.: designed and supervised the research, analysed data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Pavel Polishchuk, Mariia Matveieva, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inukai, T., Yamato, A., Akiyama, M. et al. Leveraging tree-transformer VAE with fragment tokenization for high-performance large chemical model generation. Commun Chem 8, 228 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01640-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01640-w