Abstract

Ammonia (NH3) plays a vital role in agriculture and chemical manufacturing, yet its conventional production is energy-intensive and environmentally harmful. Developing cleaner, more efficient alternatives is essential. Here we show a newly developed dual-metal nanocluster catalyst, Fe2Co1/NC, that effectively converts nitrate and nitrite pollutants into NH3 through an electrochemical process. This catalyst achieves high NH3 production rates and Faradaic efficiency, surpassing single-metal Fe/NC and Co/NC catalysts, and remains stable over extended use. When incorporated into nitrate- or nitrite-based zinc batteries, the system enables simultaneous NH3 production and electricity generation, highlighting its potential for coupled energy recovery and environmental remediation. This work provides valuable design principles for bimetallic nanocluster catalysts and offers a promising strategy for the sustainable conversion of nitrogen-containing waste into useful chemicals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is a vital raw material in both agricultural and chemical production1,2,3. While the Haber-Bosch process currently dominates industrial production, its severe energy penalties (1–2% global energy consumption) and substantial CO2 emissions fundamentally conflict with carbon neutrality objectives4,5,6. This contradiction has driven paradigm-shifting innovations in electrochemical NH3 synthesis, particularly through nitrogen reduction (NRR) and nitrate/nitrite reduction (NO3RR/NO2RR) pathways7,8. Despite the theoretical potential of NRR to be green, the high stability of the N≡N triple bond (dissociation energy of 941 kJ mol−1), coupled with the nonpolar nature of nitrogen and poor aqueous solubility, resulted in unsatisfactory NH3 yields and Faraday efficiencies (FEs)9,10. In contrast, NO3RR/NO2RR powered by renewable energy, is a competitive and promising technology11. Principally, NO3RR/NO2RR is thermodynamically and kinetically superior to NRR12. Besides, this innovative approach utilizes NO3−/NO2−, abundant nitrogen sources in industrial wastewater, enabling direct conversion to NH3 under ambient conditions13. This technology has the dual advantage of cleaning up nitrogen pollution, as well as producing high-purity NH314. Nevertheless, NO3RR/NO2RR produces a variety of by-products (e.g., N2, NOx) due to its complex reaction pathway, which affects selectivity and NH3 yield15. Therefore, designing catalysts with superior activity and high selectivity is the critical key to achieving efficient NO3RR/NO2RR16.

Nitrogen-doped carbon matrices exhibit prominent advantages in electrocatalysis, including their high electrical conductivity ensures rapid electron transfer. Concurrently, as catalyst supports, the enhanced surface hydrophilicity and the formation of metal-nitrogen coordination active sites (M-Nx) synergistically enhance the activity and stability of electrocatalytic reactions, making them ideal substrates for replacing noble metal catalysts17,18,19,20. Recently, non-noble single-atom catalysts (SACs) anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon matrices have attracted extensive attention in NO3RR/NO2RR studies21,22,23,24, owing to their distinctive geometrical configurations, tunable electronic properties, and near-theoretical-limit atomic utilization efficiency25. Yet, non-noble single-metal active sites often suffer from low selectivity and insufficient stability26. To broaden the application of SACs, the researchers have developed a variety of modulation methods for designing atomic sites, including replacing ligand atoms27, structuring metal-organic frameworks28,29, constructing ligand structures30, and building bimetallic nanoclusters31. Among them, the strategy of constructing bimetallic nanoclusters has garnered significant attention, attributed to its dual advantages of the ultra-high atomic utilization efficiency of single atoms and synergistic catalysis32,33. An and his research team employed Cu-Ni bimetallic clusters in combination with constraint engineering for the first time to solve the problems of slow NO3RR kinetics, severe shortage of catalytically active sites, and side reactions affecting the catalytic efficiency of monometallic catalysts34. Lee et al. achieved a high NH3 yield (4.625 mmol h−1 cm−2) for powdered NO3RR catalysts by in-situ constructing CuCo bimetallic clusters and maximizing the synergistic effect of two metal35. However, reports on the design of bifunctional bimetallic cluster catalysts catering to both NO3RR and NO2RR remain scarce. Accordingly, the rational design of highly efficient multifunctional metal cluster catalysts has become a key research frontier in the contemporary landscape.

Herein, we report the Fe-Co bimetallic nanocluster catalysts (Fe2Co1/NC), which are anchored within a nitrogen-doped porous carbon (NC) matrix, exhibiting pronounced bifunctional activity for NO3RR and NO2RR. The Fe2Co1/NC architecture, engineered through hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching of a sacrificial silica template, yields a well-defined conductive carbon framework. This structural design not only facilitates efficient charge transfer kinetics and enhances overall electrical conductivity but also maximizes the exposed density of catalytically active sites. Furthermore, the porous carbon matrix serves as a high-surface-area scaffold for immobilizing Fe-Co nanoclusters, enabling synergistic enhancement of catalytic performance. Consequently, the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst demonstrates exceptional activity for NO3RR and NO2RR, with its performance metrics significantly outperforming those of single-metal counterparts (Fe/NC, Co/NC). Notably, Zn-NO3− and Zn-NO2− batteries equipped with Fe2Co1/NC cathodes achieve remarkable power densities while sustaining NH3 production, highlighting their practical utility in energy conversion technologies and the valorization of nitrogenous waste.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Fe2Co1/NC

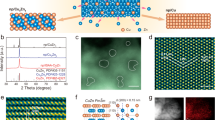

Figure 1a illustrates the process flow for the preparation of Fe2Co1/NC catalyst loaded on NC using SiO2 as a hard template, with the core steps including precursor impregnation, high-temperature carbonization, and template etching (see Synthesis Methods for details). To elucidate the morphological features of the catalyst, comprehensive characterizations including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were performed. SEM images (Fig. 1b–f) reveal uniformly porous carbon architectures across all Fe: Co molar ratios (1:1, 1:2, 2:1, 1:4, 4:1), resulting from selective etching of SiO2 templates by HF. This three-dimensional interconnected pore structure not only ensures high electrical conductivity but also significantly increases the exposure of electrochemically active sites, thereby optimizing charge transfer kinetics36. Further TEM characterization of Fe2Co1/NC corroborates its porous framework (Fig. 1g, h). Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image analysis directly visualizes that sub-nanometric Fe and Co metal nanoclusters with an average size of 0.90 nm are densely dispersed on the porous carbon matrix (Fig. 1i). This unique nanostructure may facilitate interfacial electron transfer kinetics, offering a strategy to enhance electrocatalytic efficiency in complex multi-step reactions37. The Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping manifests that Fe, Co, C, N, and O are well dispersed over carbon substrate (Fig. 1j). Furthermore, the XRD spectrum of Fig. 1k indicates broad diffraction peaks at about 24.1 ° and 43.7 °, corresponding to the (002) and (100) crystal planes of graphitic carbon, respectively38. In contrast, the absence of diffraction peaks from the Fe/Co metal or alloy crystalline phases indicates that the metal species are present in the form of sub-crystalline clusters, in agreement with the TEM results. This may be due to the low content of Fe and Co elements in the samples and the small size of the nanoclusters formed39.

a Synthesis process of Fe2Co1/NC. SEM images of b Fe1Co1/NC, c Fe1Co2/NC, d Fe2Co1/NC, e Fe1Co4/NC, f Fe4Co1/NC. g, h TEM image and i Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image of Fe2Co1/NC, red circles highlight bimetallic nanoclusters (inset: the particle size distribution of FeCo sub-nanoclusters). j HAADF-STEM image and corresponding EDS elemental maps for Fe, Co, C, N, and O. k XRD patterns of Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC and Co/NC. XPS spectra of l C 1 s, m Fe 2p, n Co 2p for Fe2Co1/NC. o Fe K-edge XANES spectra of Fe2Co1/NC and the standard samples and p their corresponding FT-EXAFS spectra.

Complementary to these analyses, the chemical composition and elemental valence states of Fe2Co1/NC were systematically characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). XPS spectra confirm the presence of elements Fe, Co, C, N, and O in Fe2Co1/NC, which is in line with the EDS-mapping results (Fig. 1l–n and Figs. S1, 2). The C1s XPS spectra showed characteristic peaks at 289.84, 287.11, 285.82, and 284.80 eV, corresponding to O-C=O, C=O, C-N, and C-C/C=C bonds, respectively (Fig. 1l)40. The deconvoluted N1s spectrum (Fig. S1) exhibits five resolved components assigned to distinct nitrogen configurations: oxidized species (402.59 eV), graphitic N (401.33 eV), pyrrolic N (400.33 eV), pyridinic N (399.26 eV), and a characteristic metal-nitrogen (M-N) coordination peak at 398.36 eV41. The O 1 s analysis (Fig. S2) reveals oxygen-containing moieties including O-C=O (534.56 eV), C-O (532.89 eV), C=O (531.37 eV), alongside a definitive metal-oxygen (M-O) coordination signal at 530.09 eV. The concurrent presence of M-N and M-O bonds in Fe2Co1/NC confirms atomic-level coordination of Fe/Co centers with adjacent N and O ligands. Such interactions between the metal and N and O contribute to the high dispersibility of the metal nanoclusters, preventing their aggregation and growth during the reaction process42. The high-resolution Fe 2p XPS spectrum (Fig. 1m) exhibits characteristic spin-orbit doublets with Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 components at 711.1 eV and 724.7 eV, respectively, both diagnostic of divalent iron (Fe2+). Shake-up satellite features at 716.4 eV and 732.5 eV further confirm octahedral coordination of Fe2+ with oxygen ligands43. The high-resolution Co 2p XPS spectrum (Fig. 1n) exhibits characteristic spin-orbit doublets with Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 components at 780.3 eV and 796.4 eV, respectively, both signatures of divalent cobalt (Co2+). Additional shake-up satellite features are definitively assigned at 788.1 eV (associated with Co 2p3/2) and 805.5 eV (corresponding to Co 2p1/2)44. Critically, XPS analysis confirmed the absence of metallic iron (Fe0) and cobalt (Co0) species, consistent with phase identification derived from XRD characterization. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was utilized to elucidate the electronic structure and local coordination environment of the as-synthesized sample. In the Fe K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra (Fig. 1o), the Fe XANES absorption edge for Fe2Co1/NC lies between those of Fe foil and Fe2O3, indicating that Fe is in a partially oxidized valence state. The k2-weighted Fourier-transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 1p) reveals a prominent peak at 1.57 Å for Fe2Co1/NC, attributed to Fe-N bonding, which aligns with the N 1 s XPS analysis. Notably, the FT-EXAFS spectra also exhibit a peak at 2.54 Å, corresponding to Fe-Co bonding, providing evidence of a direct interaction between Fe and Co8. The above analytical techniques collectively corroborate both the effective synthesis of the Fe2Co1/NC architecture and its inherent structural superiorities.

NO3RR performance evaluation

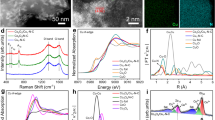

To evaluate the NO3RR performance of the synthesized catalysts, a series of electrochemical measurements were conducted using a conventional three-electrode system in an H-battery configuration. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV, Fig. 2a) tests in 0.1 M K2SO4 and 0.1 M KNO3 electrolytes reveals that the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst exhibits a more rapid increase in current density with negative potential progression compared to Co/NC and Fe/NC counterparts, demonstrating superior catalytic activity for NO3RR. Notably, Fe2Co1/NC achieves a significantly enhanced current density of −81.79 mA cm−2 at −1.2 V vs. RHE, indicating that the bimetallic configuration effectively promotes NH3 generation while suppressing the competing hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

a The LSV curves for Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC and Co/NC. b Comparative FEs and NH3 production rate of FeXCoY/NC, Fe/NC and Co/NC at different potentials. c Potential-dependent FEs and NH3 yield for Fe2Co1/NC. d ECSA measurements. (e) Nyquist plots from EIS. f, g Durability testing results. h Comparison of NH3 generation rates under different conditions (inset: 1H NMR spectra). i In situ FTIR spectroscopy of Fe2Co1/NC.

To identify the optimal catalyst, we systematically assessed the FEs and NH3 production rate of FexCoy/NC catalysts across Fe:Co ratios (1:1, 1:2, 2:1, 1:4, 4:1), along with monometallic Fe/NC and Co/NC controls. FEs and production rates were calculated from chronoamperometric test (I-T) and NH3 quantification (UV-Vis spectrophotometry of diluted post-electrolysis electrolyte, Fig. S3). As depicted in Fig. 2b, Fe2Co1/NC exhibits the highest FEs at all tested potentials, demonstrating superior selectivity for the NO3RR. Notably, it achieves the highest FE at −1.0 V vs. RHE, confirming maximal NO3− to NH3 conversion selectivity at Fe:Co = 2:1. Furthermore, the significantly higher FE of Fe2Co1/NC versus monometallic controls confirms a marked synergistic effect within Fe-Co nanoclusters for promoting NO3RR, consistent with established literature39. As depicted in Fig. 2c, the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst exhibits optimal NO3RR performance at −1.0 V vs. RHE under standard conditions, achieving a FE of 85.6% and a peak NH3 production rate of 171.5 μmol h−1 cm−2. A comparative analysis with recently reported catalysts (Table S1) reveals that the Fe2Co1/NC material exhibits significantly superior overall catalytic performance. Notably, the FE exhibits a systematic decline with positive potential shifts, decreasing considerably to 42.7% at −1.2 V vs. RHE. This behavior is attributable to the intensified HER, which competes with NO3RR and diminishes catalyst selectivity towards the NH3 synthesis pathway45.

To further elucidate intrinsic activity differences, the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of each catalyst was evaluated via double-layer capacitance (Cdl) measurements within the non-faradaic potential region, while interfacial charge transfer kinetics were probed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). As shown in Figs. S4-S6 and Fig. 2d, the Cdl value of Fe2Co1/NC (34.0 mF cm−2) significantly exceeds that of Fe/NC (11.1 mF cm−2) and Co/NC (14.2 mF cm−2), for different scanning rates from 50 mV s−1 to 100 mV s−1. This indicates a larger ECSA for Fe2Co1/NC, implying greater exposure of electrochemically accessible active sites. Furthermore, EIS measurements conducted at −1.0 V vs. RHE (Fig. 2e) assessed the interfacial processes of Fe/NC, Co/NC, and Fe2Co1/NC. The Nyquist plots for all catalysts exhibit distinct high-frequency semicircular arcs, primarily corresponding to the charge transfer resistance (Rct) at the electrode/electrolyte interface. Fe/NC displays the largest arc diameter, indicating the highest Rct. In contrast, Fe2Co1/NC exhibits the smallest arc diameter, significantly lower than both Fe/NC and Co/NC, unequivocally confirming its minimal Rct. This reduced Rct directly reflects accelerated charge transfer kinetics at the Fe2Co1/NC interface during the NO3RR. Integrating the Cdl and EIS analyses, the superior catalytic performance of Fe2Co1/NC, manifested in high FE and NH3 production rate, is attributed to two key factors: (1) an enlarged ECSA providing abundant active sites, and (2) significantly reduced Rct ensuring efficient interfacial electron transfer. This enhancement arises from the highly dispersed bimetallic (Fe-Co) nanoclusters within the porous NC matrix of Fe2Co1/NC. This structure maximizes active site exposure while optimizing electron conduction pathways, thereby synergistically promoting the overall kinetics of the NO3RR.

Catalyst stability, a critical metric for practical implementation, was rigorously evaluated for Fe2Co1/NC. Cyclic electrolysis tests at −1.0 V vs. RHE over six cycles (Fig. 2f) demonstrate almost constant FEs and NH3 production rates, indicating exceptional cycling stability. Furthermore, a 40-hour durability test (Fig. 2g) reveals stable current density without decay, confirming long-term operational robustness. After the catalytic reaction, the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst maintains its original porous morphology (Fig. S7), with no noticeable structural changes observed. Additionally, a comparison of the pre- and post-reaction XPS spectra (Fig. S8) shows no significant differences. These findings collectively demonstrate the excellent electrochemical stability of Fe2Co1/NC for NO3RR. Additionally, to rigorously assess the catalyst’s resilience in the presence of industrial wastewater contaminants, 0.01 M Cl− was introduced into the electrolyte to simulate complex real-world matrices. As shown in Fig. S9, the NH3 yield rate and FEs exhibits negligible changes across the applied potentials compared to those in the original electrolyte. This consistent performance under chloride-rich conditions demonstrates the catalyst’s excellent Cl− tolerance, underscoring its potential for practical application in nitrate-contaminated wastewater treatment systems.

To definitively confirm the origin of NH3 and exclude potential contributions from environmental contamination or impurities, systematic control experiments were conducted (Fig. 2h). The analysis reveals negligible NH3 detection under three conditions: at the OCP, in the absence of NO3⁻, and without electrochemical pretreatment. The observed NH3 levels are substantially lower than the production rate (171.5 μmol h−1 cm−2) achieved with Fe2Co1/NC under optimal NO3RR conditions. Additionally, 15N isotopic labeling was employed to definitively trace the nitrogen source of the electrogenerated NH3 (inset in Fig. 2h). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) analysis reveals a characteristic triplet for NH4⁺ when 14NO3− serves as the nitrogen source, whereas a distinct doublet is exclusively observed when 15NO3− is fed. These results conclusively demonstrate that the produced NH3 originates directly from the NO3RR, rather than from atmospheric N2 fixation or external nitrogen contaminants39.

To mechanistically elucidate the dynamic mechanism of the NO3RR over Fe2Co1/NC catalysts, in situ Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to track potential-dependent intermediates (Fig. 2i). Distinct spectral features emerged under cathodic polarization (−0.6 ~ −1.5 V vs. RHE), contrasting with negligible signals at OCP. The ν(O-H) and δ(H-O-H) absorption peaks at 3355 cm−1 and 1632 cm−1 indicate that the interfacial hydrolysis process continues to provide protons for the reaction, which is a key prerequisite for the proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) pathway46. the characteristic peaks of ν(NO) characteristic peak at 1456 cm−1 reveals the generation of nitric oxide (NO (ads)) in the adsorbed state, corroborating the activation of nitrate via the successive deoxygenation pathway (NO3− → NO2− → NO (ads)). The δ(NOH) absorption peaks at 1520 cm−1 are also observed during this process. δ(N-H) vibrational mode at 1584 cm−1 provides direct evidence for the presence of hydroxylamine (NH2OH) intermediates47, while the enhanced ν(N-H) vibration at 3750 cm−1 is a clear indication of the eventual generation of free NH348. The above in situ FTIR constructed a complete reaction pathway: NO3− → NO (ads)→NOH → NH2OH → NH3.

To elucidate the role of the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst in enhancing the NO3RR while suppressing the competing HER, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed. Given that the adsorption of NO3− and H⁺ is regarded as a prerequisite for catalytic activity9,49, the d-band centers of three catalysts (Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC, and Co/NC) were first evaluated via projected density of states (PDOS) analysis (Fig. 3a). The results show that the d—band center of Fe/NC (εd = −1.07 eV) is higher than that of Co/NC (εd = −1.37 eV). Meanwhile, due to the interaction between Fe and Co atoms, the εd value of Fe2Co1/NC is adjusted to a moderate level of −1.12 eV, which effectively modulates the interaction between the metal active sites and reaction intermediates50. Subsequently, the adsorption energies (ΔEad) of NO3− and H⁺ on the catalysts were calculated. Notably, Fe2Co1/NC exhibits a higher ΔEad for NO3− and a lower ΔEad for H⁺ compared to Fe/NC and Co/NC (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that the bimetallic sites more readily capture NO3−, initiating the reduction reaction. Fe2Co1/NC demonstrates more favorable kinetic properties for the NO3RR, while the weaker proton adsorption effectively suppresses the HER51. The preferential adsorption of NO3− over H⁺ further confirms the selective promotion of NO3RR and inhibition of HER on Fe2Co1/NC52. In addition, charge density difference analysis revealed significant electron transfer between the Fe2Co1/NC surface and the adsorbed NO3⁻ (Fig. 3c), indicating efficient activation of NO3⁻, which is essential for subsequent reduction steps53.

To further understand the reaction mechanism, the free energy profiles for the complete NO3RR pathway were computed for each catalyst. As depicted in Fig. 3d, the potential-determining step (PDS) for the catalysts corresponds to the proton-electron transfer of *NO to *NOH (*NO + H⁺ + e− → *NOH). After *NOH is generated, the reaction proceeds further, ultimately producing NH3 on the Fe2Co1/NC surface. Notably, the PDS energy barrier of Fe2Co1/NC (0.91 eV) is significantly lower than those of Co/NC (1.51 eV) and Fe/NC (2.92 eV), suggesting that bimetallic synergy effectively reduces the critical energy barrier, accelerates the conversion of NO3− to NH3, and thereby enhances catalytic efficiency50. Collectively, both theoretical and experimental results validate that that the bimetallic Fe2Co1/NC catalyst not only promotes NO3− adsorption but also facilitates a more efficient reaction pathway by reducing energy barriers, thereby significantly enhancing NO3RR performance.

Zn-NO3 − battery performance evaluation

Based on the excellent structural chemistry and catalytic properties of Fe2Co1/NC, a Zn-NO3− battery system was successfully constructed using it as the cathode and Zn foil as the anode (Fig. 4a). To evaluate the electrochemical performance of Zn-NO3− batteries with different materials (Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC, and Co/NC) as cathode materials, the discharge performance tests were carried out in a mixed electrolyte of 0.1 M KNO3 and 0.1 M K2SO4 (Fig. 4b). The results show that the battery based on Fe2Co1/NC cathode exhibits significantly better electrochemical performance with a peak power density as high as 0.39 mW cm−2 compared to Fe/NC and Co/NC batteries. In addition, the OCP of the battery is measured to be 0.71 V (Fig. 4c). To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the system, the electrolyte after electrolysis was analyzed by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy at different current densities (Fig. S10), from which the NH3 yield of the Zn-NO3− battery based on the Fe2Co1/NC cathode and its FE is quantitatively determined. As shown in Fig. 4d, both the NH3 yield and FEs increase simultaneously with the increase of current density. The optimal performance is achieved at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with an NH3 yield of 25.1 μmol h−1 cm−2 and a FE of 53.9%. The rate performance of the Zn-NO3− battery featuring a Fe2Co1/NC cathode was evaluated (Fig. 4e). An increase in current density from 2 mA cm−2 to 10 mA cm−2 results in a progressive widening of the gap between its charge and discharge curves. This characteristic response highlights the system’s robust electrochemical behavior across different current densities.

Battery stability is a key indicator for evaluating its overall performance. As shown in Fig. 4f, the Zn-NO3− battery was subjected to a constant current discharge test for 15 h at a constant current density of 5 mA cm−2. The results show that the Zn-NO3− battery with Fe2Co1/NC cathode exhibits a stable discharge voltage plateau, which fully confirms its excellent cycling stability. In conclusion, the bimetallic cluster architecture demonstrates not only high catalytic efficiency for NO3− to NH3, but also exhibits high energy conversion efficiency and significant potential for practical engineering applications.

NO2RR performance research

Nitrite anion (NO2−) presents unique advantages as a promising substrate for aqueous electrochemical NH3 synthesis, including low N=O bond dissociation energy, favorable aqueous solubility, and relatively high redox potential. To evaluate the NO2RR performance, the electrocatalytic performance of three synthesized catalysts (Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC, and Co/NC) for NO2− to NH3 conversion was systematically evaluated through LSV measurements. As depicted in Fig. 5a, the LSV curves measured in 0.1 M KNO2 and 0.1 M K2SO4 electrolyte reveal that the current density of Fe2Co1/NC is significantly higher than that of Fe/NC and Co/NC in the potential range of 0.0 V vs. RHE to −1.2 V vs. RHE, peaking at 150 mA cm−2. This exceptional activity confirms the superior NO2RR capability of Fe2Co1/NC, which establishes favorable kinetics for NH3 synthesis. These results demonstrate that bimetallic cluster structures effectively synergize to enhance the intrinsic electrocatalytic activity of catalytic sites54,55. To identify optimal NO2RR catalysts, we systematically evaluated the ammonia synthesis performance of Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC, and Co/NC within the potential window of −0.9 to −1.1 V vs. RHE. As depicted in Fig. 5b, NH3 yield exhibits a positive potential dependence, with Fe2Co1/NC demonstrating superior NH3 production rates that underscore its exceptional catalytic efficacy. This enhancement is attributed to bimetallic cluster-mediated synergistic effects, aligning with prior studies confirming the critical role of dual-metal configurations in NO2RR pathways3,56. To precisely quantify FEs and NH3 yield for Fe2Co1/NC catalysts, the I-T method (Fig. S11) coupled with UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. S12) was employed for systematic assessment. As depicted in Fig. 5c, the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst exhibits a peak NH3 generation rate of 322.6 μmol h−1 cm−2 at a potential of −1.2 V vs. RHE, surpassing recently reported catalysts and highlighting the synergistic effect of bimetallic nanoclusters (Table S2). Its FEs show a typical volcano distribution, reaching an optimum value of 78.1% at −1.0 V vs. RHE, and then falling back to 63.4% at −1.2 V vs. RHE. This efficiency decay was attributed to the intensification of the HER at high cathodic potentials, which competes with the nitrite reduction process and thus inhibits the selectivity of NH3 synthesis57. A long-term stability assessment of the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst was subsequently conducted (Fig. 5d). At a potential of −1.2 V vs. RHE, the catalyst maintains a stable current density of 40 mA cm−2 for 25 hours. This performance underscores the excellent catalytic stability of the Fe2Co1/NC catalyst over an extended period.

Zn-NO2 − battery performance evaluation

Building upon the excellent NO2RR performance of the catalysts, researchers assembled Zn-NO2− batteries using Fe2Co1/NC, Fe/NC, and Co/NC catalysts to investigate their electrochemical performance within a battery configuration systematically. Discharge tests were performed in a mixed electrolyte containing 0.1 M KNO2 and 0.1 M K2SO4 (Fig. 6a). The results demonstrate that the Fe2Co1/NC-based battery exhibits significantly superior power density compared to those with single-metal Fe/NC or Co/NC catalysts, peaking at approximately 4.58 mW cm−2 at 4.75 V vs. Zn/Zn2+. Furthermore, the OCP of the Fe2Co1/NC-based Zn-NO2− battery was measured at 1.43 V vs. Zn/Zn2+ (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the stability of the Zn-NO2− battery employing an Fe2Co1/NC cathode was evaluated (Fig. 6c). The battery demonstrates no significant performance degradation during continuous operation for 7 h across current densities ranging from 0.2 to 5 mA cm−2.

To systematically assess the performance of the Zn-NO2− battery with the Fe2Co1/NC cathode, the NH3 yields and FEs were further measured at various current densities (Fig. 6d). The data reveal that the NH3 yield reaches a peak value of 30.9 μmol·h−1 at 8 mA cm−2, while the FE achieves 76.0% at 4 mA cm−2. Subsequent charge-discharge tests (Fig. 6e) indicate that the voltage gap of the Zn-NO2− battery systematically increased as the current density was stepped up from 0.5 mA cm−2 to 3.0 mA cm−2. At a low current density of 0.5 mA cm−2, the voltage gap was 1.49 V, while at a high current density of 3.0 mA cm−2, the voltage gap widened to 2.19 V, indicating the excellent charging and discharging performance of the battery. Long-term cycling stability tests (Fig. 6f) confirm highly stable performance output over 24 h of continuous operation. Collectively, these electrochemical performance metrics demonstrate the significant potential of the Fe2Co1/NC material for NH3 production in Zn-NO2− battery. This system enables the dual-functional objective of synchronous ammonia synthesis and pollutant removal, offering a viable approach for the integration of electrocatalytic ammonia production and environmental remediation.

Conclusions

In this study, a bifunctional Fe2Co1/NC electrocatalyst was successfully synthesized via hydrogen fluoride etching of silica templates to construct porous carbon substrates, synergistically anchoring FeCo bimetallic nanoclusters as active sites. The catalyst exhibits excellent activity for NO3RR and NO2RR. Comprehensive structural characterizations including SEM, TEM, HAADF-STEM, XPS and XAFS collectively confirm the structural integrity of the material. In situ spectroscopy and theoretical simulations further elucidate the catalytic mechanism and reaction pathways. Electrochemical measurements demonstrate that Fe2Co1/NC achieves optimal NO3− to NH3 conversion at −1.0 V vs. RHE, delivering an exceptional NH3 yield of 171.5 μmol h−1 cm−2 and a FE of 85.6%. The catalyst maintains excellent operational stability for 40 h. When integrated into a Zn-NO3− battery, the system simultaneously generates electricity (0.39 mW cm−2), and NH3 (25.1 μmol h−1 cm−2, 53.9% FE). For NO2RR, Fe2Co1/NC attains a peak FE of 78.1% at −1.0 V vs. RHE. The maximum NH3 yield reaches 322.6 μmol h−1 cm−2 at −1.2 V vs. RHE, with sustained stability exceeding 25 hours. Assembled Zn-NO2− battery exhibits substantially enhanced performance, attaining a power density of 4.58 mW cm−2. Overall, this work offers a robust platform for dual-function nitrogen conversion and provides valuable guidance for designing high-performance bimetallic nanocluster catalysts.

Methods

Material synthesis

Synthesis of Fe2Co₁/NC catalysts

Initially, citric acid monohydrate (C6H8O7⋅H2O, 5.0 g), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 5.0 g), silica template (SiO2, 1.5 g), iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.33 g), and cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.12 g) were co-dissolved in 15 mL of deionized water. A homogeneous precursor solution was formed through ultrasonication-assisted magnetic stirring. This solution was subjected to vacuum freeze-drying to obtain a solid mixture, which was then thoroughly ground to yield a white precursor powder. Subsequently, the powder was subjected to high-temperature pyrolysis in a tube furnace under a continuous flow of high-purity argon (Ar). The thermal program was set to heat to the target carbonization temperature of 900 °C at a ramping rate of 10 °C min−1, followed by isothermal carbonization for 3 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, a black intermediate product was obtained. To remove the SiO2 template, the product was immersed in a 5 wt% hydrofluoric acid (HF) aqueous solution and etched at room temperature for 10 h. Following etching, the sample was repeatedly washed with copious amounts of deionized water until a neutral pH was achieved to eliminate residual acid and dissolved silicon species. Finally, the washed solid product was dried in an oven at 60 °C, thus obtaining the target Fe2Co1/NC catalyst powder.

Synthesis of FeₓCoᵧ/NC (x:y = 4:1, 1:2, 1:1, 1:4)

Synthesized using identical procedures but with adjusted Fe/Co precursor masses. FexCoy/NC (x:y = 4:1, 1:2, 1:1, 1:4) were synthesized in the same steps, but the masses of Fe and Co were replaced with 0.4 g Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O and 0.072 g Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O (4:1), 0.1667 g Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O and 0.2401 g Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O (1:2), 0.25 g Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O and 0.1801 g Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O (1:1), 0.1 g Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O and 0.2881 g Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O (1:4). FexCoy/NC means that the total mass of the iron-containing material, 0.5 g, is used to determine the amount of substance n. The mass of the iron-containing material is found by substituting n of X/X + Y, and the mass of the cobalt-containing material is found by substituting n of Y/X + Y for the mass of the cobalt-containing material.

Synthesis of Fe/NC

The procedure for the synthesis of Fe/NC is similar to that of Fe2Co1/NC. However, only 0.5 g of Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O was used as the sole metal precursor.

Synthesis of Co/NC

Co/NC was synthesized in the same steps as Fe2Co1/NC. However, only 0.5 g of Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O was used as the sole metal precursor.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper on the Supplementary Information and are also available upon request from the corresponding author. All NMR spectra recorded during this study are included in the Supplementary Data 1 file. The raw data for the theoretical calculations during this study are included in Supplementary Data 2 file. All the raw data for the figures during this study are included in Supplementary Data 3 file.

References

Sun, S. et al. Spin-related Cu-Co pair to increase electrochemical ammonia generation on high-entropy oxides. Nat. Commun. 15, 260 (2024).

Shen, Z. et al. Highly accessible electrocatalyst with in situ formed copper-cluster active sites for enhanced nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. ACS Nano 19, 4611–4621 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Advances in the synthesis strategies of carbon⁃based single⁃atom catalysts and their electrochemical applications. China Powder Sci. Technol. 30, 35–45 (2024).

An, T.-Y. et al. Utilizing the Wadsley-Roth structures in TiNb2O7@C microspheres for efficient electrochemical nitrogen reduction at ambient conditions. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 7, 201 (2024).

Dong, J.-H. et al. Engineering Ce promoter to regulate H* species to boost tandem electrocatalytic nitrate reduction for ammonia synthesis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2422025 (2025).

Chen, M. et al. Advanced characterization enables a new era of efficient carbon dots electrocatalytic reduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 535, 216612 (2025).

Jiang, Z. et al. Molecular electrocatalysts for rapid and selective reduction of nitrogenous waste to ammonia. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2239–2246 (2023).

Lu, H. et al. Electron-deficient asymmetric Co centers marry oxygen vacancy for NO3RR: Excellent activity and anion resistance property. Chem. Eng. J. 503, 158536 (2025).

Huang, Z. et al. Recent progress in electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction to ammonia (NRR). Coord. Chem. Rev. 478, 214981 (2023).

Wu, T., Melander, M. M. & Honkala, K. Coadsorption of NRR and HER intermediates determines the performance of Ru-N4 toward electrocatalytic N2 reduction. ACS Catal. 12, 2505–2512 (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Tandem electrocatalytic reduction of nitrite to ammonia on rhodium–copper single atom alloys. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401941 (2024).

Choi, J. et al. Identification and elimination of false positives in electrochemical nitrogen reduction studies. Nat. Commun. 11, 5546 (2020).

Ren, Z., Shi, K. & Feng, X. Elucidating the intrinsic activity and selectivity of Cu for nitrate electroreduction. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3658–3665 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Self-powered energy-efficient electrochemical nitrite reduction coupled with sulfion oxidation for ammonia synthesis and sulfur recovery over hierarchical cobalt sulfide nanostructures. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 365, 124991 (2025).

Cui, Z. et al. Multi-dimensional Ni@TiN/CNT heterostructure with tandem catalysis for efficient electrochemical nitrite reduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202501578 (2025).

He, N. et al. Efficient nitrate to ammonia conversion on bifunctional IrCu4 alloy nanoparticles. ACS Nano 19, 4684–4693 (2025).

Lian, K. et al. Coupling value-added methanol oxidation with CO2 electrolysis by low-coordinated atomic Ni sites. ACS Nano 19, 20001–20011 (2025).

Chen, K. et al. Urea electrosynthesis from nitrate and CO2 on diatomic alloys. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402160 (2024).

Du, W. et al. Synergistic Cu single atoms and MoS2-edges for tandem electrocatalytic reduction of NO3− and CO2 to urea. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401765 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Promoting electroreduction of CO2 and NO3− to urea via tandem catalysis of Zn single atoms and In2O3-x. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2402309 (2024).

Zhu, R., Qin, Y., Wu, T., Ding, S. & Su, Y. Periodic defect engineering of iron–nitrogen–carbon catalysts for nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Small 20, 2307315 (2024).

Cheng, X. et al. Unveiling structural evolution of Fe single atom catalyst in nitrate reduction for enhanced electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis. Nano Res. 17, 6826–6832 (2024).

Wei, T., Zhou, J. & An, X. Recent advances in single-atom catalysts (SACs) for photocatalytic applications. Mater. Rep. Energy 4, 100285 (2024).

Huang, G. et al. Anion-regulated active nickel site for nitrate reduction in efficient ammonia electrosynthesis and Zn-Nitrate Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2500577. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202500577 (2025).

Lu, X., Wei, J., Lin, H., Li, Y. & Li, Y.-Y. Boron regulated Fe single-atom structures for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 14654–14664 (2024).

Liang, C. et al. Rational regulation of Cu species in N-doped carbon-hosted Cu-based single-atom electrocatalysts for the conversion of nitrate to ammonia. Coord. Chem. Rev. 522, 216174 (2025).

Zhang, W., Zhao, Y., Huang, W., Huang, T. & Wu, B. Coordination environment manipulation of single atom catalysts: regulation strategies, characterization techniques and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 515, 215952 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Electronic metal–support interaction triggering interfacial charge polarization over CuPd/N-doped-C nanohybrids drives selectively electrocatalytic conversion of nitrate to ammonia. Small 18, 2203335 (2022).

yang, Y. et al. Research progress on adsorption mechanism of radioactive iodine by metal-organic framework composites. China Powder Technol. 30, 151–160 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. The “4 + 1” strategy fabrication of iron single-atom catalysts with selective high-valent iron-oxo species generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2322283121 (2024).

Zheng, S.-J. et al. Unveiling ionized interfacial water-induced localized H* enrichment for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202413033 (2025).

Liu, L. & Corma, A. Bimetallic sites for catalysis: from binuclear metal sites to bimetallic nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 123, 4855–4933 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Entropy-engineered middle-in synthesis of dual single-atom compounds for nitrate reduction reaction. ACS Nano 18, 23168–23180 (2024).

Guo, T., Zhou, D. & Zhang, C. Perspectives on electrochemical nitrogen fixation catalyzed by two-dimensional MXenes. Mater. Rep. Energy 2, 100076 (2022).

Jang, W. et al. Homogeneously mixed Cu–Co bimetallic catalyst derived from hydroxy double salt for industrial-level high-rate nitrate-to-ammonia electrosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27417–27428 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. NH3-induced in situ etching strategy derived 3D-interconnected porous MXene/carbon dots films for high performance flexible supercapacitors. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 231 (2023).

Hu, Q. et al. Subnanometric nickel phosphide heteroclusters with highly active Niδ+–Pδ− pairs for nitrate reduction toward ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 12228–12238 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Single-atom Co meets remote Fe for a synergistic boost in oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2500617 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Co-engineering of Fe–Mn nanoclusters with porous carbon for enhanced electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis. Chem. Commun. 61, 4399–4402 (2025).

Ma, X. et al. S-doped mesoporous graphene modified separator for high performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Mater. Rep. Energy 4, 100279 (2024).

Liu, Z., Ma, J., Hong, M. & Sun, R. Potassium and sulfur dual sites on highly crystalline carbon nitride for photocatalytic biorefinery and CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 13, 2106–2117 (2023).

Tan, X. et al. Synthesis of NiMo–NiMoOx with crystalline/amorphous heterointerface for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 18, 94907368 (2025).

Peng, M. et al. Bioinspired Fe3C@C as highly efficient electrocatalyst for nitrogen reduction reaction under ambient conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 40062–40068 (2019).

Zhao, D. et al. Ni–Co bimetallic phosphide catalyst toward electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis under ambient conditions. RSC Adv. 15, 10390–10394 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Interfacial water structure modulation on unconventional phase non-precious metal alloy nanostructures for efficient nitrate electroreduction to ammonia in neutral media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202508617 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Harnessing Spin-Lattice Interplay in Metal Nitrides for Efficient Ammonia Electrosynthesis. Adv. Mater. 2504505. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202504505 (2025).

Liu, W. et al. Regulating local electron distribution of Cu electrocatalyst via boron doping for boosting rapid absorption and conversion of nitrate to ammonia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2408732 (2024).

Rao, X. et al. A porous Co3O4-carbon paper electrode enabling nearly 100% electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Mater. Rep. Energy 3, 100216 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Synergy of single atoms and sulfur vacancies for advanced polysulfide–iodide redox flow battery. Nat. Commun. 16, 2885 (2025).

Ye, W. et al. Continuous intermediates spillover boosts electrochemical nitrate conversion to ammonia over dual single-atom alloy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. e202509303. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202509303 (2025).

Wang, G. et al. NiMoO4 nanorods with oxygen vacancies self-supported on Ni foam towards high-efficiency electrocatalytic conversion of nitrite to ammonia. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 647, 73–80 (2023).

Ge, J. et al. Al-Ce intermetallic phase for ambient high-performance electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate to ammonia. ChemCatChem 15, e202300795 (2023).

Yang, M. et al. NiMo-based alloy and its sulfides for energy-saving hydrogen production via sulfion oxidation assisted alkaline seawater splitting. Chin. Chem. Lett. 36, 110861 (2025).

Luo, J. et al. Local microenvironment reactive zone engineering promotes water activation. Mater. Rep. Energy 5, 100327 (2025).

Li, X. & Hu, W. Review of design strategies for particle catalysts used in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction in acidic media. China Powder Sci. Technol. 31, 81–90 (2025).

Lu, Y., Liu, W. & Jiang, Y. Research progress on oxidase-like performance of cobalt-based single-atom catalysts. China Powder Sci. Technol. 31, 66–74 (2025).

Wang, W., Chen, J. & Tse, E. C. M. Synergy between Cu and Co in a layered double hydroxide enables close to 100% nitrate-to-ammonia selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26678–26687 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Guangxi Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (2024GXNSFFA010008), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22469002 and 22304028), and Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province of China (20240101098JC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Yang and M. Chen synthesized, characterized and performed electrochemical tests, to which J. Ma contributed. L. Zhang performed the in-situ FTIR calculations, to which Y. Feng and L. Zhuo contributed. Y. Wang, C. Hu and X. Liu co-edited the paper. M. Yang and M. Chen co-wrote the paper. X. Liu supervised this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Uk Sim, Ke Chu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, M., Chen, M., Wang, Y. et al. Dual-function FeCo bimetallic nanoclusters for ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate/nitrite reduction. Commun Chem 8, 267 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01674-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01674-0