Abstract

UHRF1 is a pivotal epigenetic regulator bridging DNA methylation and histone modifications, frequently overexpressed in prostate cancer (PCa). However, no UHRF1-targeted therapeutics have advanced to clinical trials. Here, we report the development of H93, a hybrid small molecule integrating functional groups derived from NSC232003 and vorinostat, respectively. H93 exhibits potent anticancer activity in vitro, correlating with UHRF1 protein abundance, and co-crystallization studies confirm that H93 directly binding to the SRA domain of UHRF1. Intriguingly, H93 promotes UHRF1 dimerization, generating a defined binding pocket that stabilizes compound engagement and enhances druggability of UHRF1 as a non-kinase target. Dimerized UHRF1 adopts a “closed” conformation that disrupts its interaction with DNMT1, impairs DNA methylation maintenance, and reactivates epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes. In vivo, H93 demonstrates significant antitumor efficacy. Overall, this study elucidates the structural and mechanistic basis of H93, establishing it as a promising UHRF1-targeted therapy for PCa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the primary treatment for prostate cancer (PCa)1. However, therapeutic resistance typically develops within 18–24 months, driving disease progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC)2. Abiraterone and enzalutamide, the second-generation antiandrogen drugs, have been approved for the treatment of metastatic CRPC, but drug resistance inevitably emerges ~6 months after treatment3,4. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify novel drug targets and develop effective therapeutic agents.

UHRF1 (Ubiquitin-like containing PHD and RING Finger Domains 1, Supplementary Fig. 1a), an essential epigenetic regulator, recognizes hemi-methylated DNA and recruits DNMT1 to newly synthesized daughter strands to maintain DNA methylation5,6. UHRF1 is frequently overexpressed in multiple cancer types, including PCa7, and its elevated expression positively correlates with malignancy, showing significantly higher levels in drug-resistant PCa8. Studies have shown that upregulated UHRF1 facilitates the coordinated silencing of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) by altering DNA methylation patterns9,10. Conversely, UHRF1 deletion has been found to dramatically inhibit PCa cell proliferation by reversing DNA methylation and restoring the expression of silenced TSGs7. These findings suggest that UHRF1 could serve as an ideal diagnostic marker for ADT resistance in PCa and as a promising target for anticancer drug development.

Several small-molecule compounds derived from natural products have been reported to induce UHRF1 protein degradation10,11. Additionally, compounds that preferentially inhibit the interaction of UHRF1 with histone proteins or hemi-methylated DNA have been developed12,13. A recent study screened 260,000 small-molecule candidates from the NCI/DIP Repository and identified NSC232003 as a UHRF1-targeted inhibitor. NSC232003 exhibits high affinity for the SRA domain of UHRF1, thereby inhibiting its interaction with DNMT114. However, in our studies, NSC232003 unfortunately demonstrated weak anticancer activity against PCa (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel compounds based on the structure of NSC232003 to enhance its anticancer efficacy.

In this study, we developed a small-molecule compound, H93, by integrating two functional groups derived from NSC232003 and vorinostat, a selective HDAC inhibitor. We evaluated the in vitro anticancer efficacy of H93 in PCa cells and investigated its impact on DNA methylation maintenance. Furthermore, using co-crystallization techniques, we observed the binding of H93 to the SRA domain of UHRF1 protein and validated its effects on protein conformation through co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. Our study confirms the feasibility of H93 as a UHRF1-targeted small-molecule inhibitor for PCa therapy, and further highlights its potential as a therapeutic strategy for UHRF1-overexpressing cancers. Moreover, our study provides valuable insights for the subsequent design and optimization of UHRF1-targeted inhibitors.

Results

A hybrid chemical compound H93 has been developed

Two distinct inhibitory activities are integrated into a single molecule to achieve synergistic therapeutic efficacy, a strategy known as multi-target drug design. This approach has the potential to enhance therapeutic effects, reduce the risk of drug-drug interactions, provide more predictable pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD), and even mitigate drug resistance15. In our studies, NSC232003 did not exhibit significant anticancer efficacy (Supplementary Fig. 1b), despite being predicted to bind the SRA domain of UHRF1 protein (UHRF1SRA) and strongly inhibiting the interaction between UHRF1 and DNMT114. To address this, we proposed optimizing the structure of NSC232003 by incorporating additional functional groups from other small-molecule drugs. The hydrophobic tails and the Zn²⁺-chelating hydroxamic acid moiety from vorinostat have recently been employed in multi-target drug design strategies16. Moreover, our group and others have reported that UHRF1 deletion and HDAC inhibition can reactivate epigenetically silenced TSGs (Supplementary Fig. 1c)17,18. Based on these findings, we designed a hybrid small-molecule compound by integrating the pyrimidine ring from NSC232003 with the hydrophobic tails and the Zn²⁺-chelating hydroxamic acid moiety from vorinostat (Fig. 1a). Ideally, we hypothesized that this compound binds to UHRF1SRA via the pyrimidine ring from NSC232003, thereby preventing DNMT1 recruitment while simultaneously enhancing anticancer activity through the hydrophobic tails and Zn²⁺-chelating hydroxamic acid from vorinostat. The chemical synthesis of H93 involves a straightforward three-step process, as shown in Fig. 1b, and its structural properties were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Data 1).

H93 inhibited the in vitro proliferation of PCa cells

To assess the antitumor activity of H93, we performed colony formation assays across a panel of PCa cell lines and normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (Fig. 2a), and cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assays in several PCa cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of H93 were determined for each cell line. Notably, the cell viability treated by H93 was negatively correlated with UHRF1 protein expression levels (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2e). Importantly, H93 had no significant effect on the viability of normal endothelial cells, highlighting its tumor-specific activity. These findings suggest that H93 is a UHRF1-targeting small-molecule inhibitor with promising tumor specificity.

a Colony formation assays were used to test the inhibitory activity of H93 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) or PCa cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (Upper) Representative images of colony formation assays are presented. (Lower) The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of each cell line are shown as mean ± SD. b UHRF1 protein expression in HUVEC and PCa cells was assessed by immunoblotting. Experiments were performed in triplicate. c The correlation between H93 inhibitory activity and UHRF1 expression levels in PCa cells was analyzed. A scatter plot illustrates the relationship between relative UHRF1 protein levels and IC50 values. IC50 values were determined using a dose-response nonlinear regression model, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated via linear regression.

H93 directly binds UHRF1SRA and forms a complex with the UHRF1SRA dimer

To elucidate the molecular mechanism of UHRF1 inhibition by H93, we first assessed its binding affinity to UHRF1SRA using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays. H93 exhibited strong binding to UHRF1SRA, with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.44 ± 0.04 µM (Fig. 3a). We further validated the interaction of H93 and UHRF1SRA by performing co-crystallization analysis (Fig. 3b). The crystal structure of UHRF1SRA/H93 complex was determined at a 2.4 Å resolution in the P31 space group, and the detailed interactions were analyzed using LigPlot+ software19. As shown in Fig. 3b, the final 2Fo−Fc electron density map clearly defined the presence of H93 within the UHRF1SRA/H93 complex structure, and the omit/polder maps of H93 were shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a. H93 forms the hydrogen bonds with Trp527, Arg528 and Arg581 of UHRF1SRA, respectively. Interestingly, this binding mode differs completely from the previously predicted model of NSC232003 at the 5-methylcytosine (5mC) cavity based on theoretical druggability assessments14. To further validate the binding model of UHRF1SRA and H93, we mutated the three key residues involved in the interaction. The mutant proteins exhibited a 3- to 5-fold reduction in binding affinity to H93 compared to wild-type UHRF1SRA (Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1). These findings confirm that H93 directly interacts with UHRF1SRA through Trp527, Arg528, and Arg581.

a The binding affinity between H93 and UHRF1SRA was measured using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays. Representative images are shown. b H93 (magenta) interacts with UHRF1SRA (cyan) through hydrogen bonds. The final refined 2Fo-Fc electron density map for H93 is contoured at 1.0σ and shown in gray. Key interacting residues are displayed as stick representations, with hydrogen bonds indicated by black dotted lines. c H93 is positioned within the pocket formed at the UHRF1SRA dimerization interface. d Key interactions at the UHRF1SRA dimer interface. UHRF1SRA molecules (cyan and lime) and H93 (magenta) are represented as sticks, with hydrogen bonds depicted as black dotted lines.

In the co-crystallization structure, we unexpectedly observed that two UHRF1SRA molecules (A and B) interacted with each other and formed a pocket, within which a single H93 compound was enclosed inside the pocket (Fig. 3c). The two UHRF1SRA molecules formed a dimer with an interface of ~1200 Ų. Specifically, the Asp584 residue of UHRF1SRA-A formed a hydrogen bond with the His445 residue of UHRF1SRA-B, while the side chain of Lys563 in UHRF1SRA-A established a hydrogen bond with the main chain of Ala618 in UHRF1SRA-B (Fig. 3d). We further analyzed the detailed interactions at the UHRF1 dimer interface by PDBsum (Supplementary Fig. 3c). In addition to the hydrophilic interactions, there were intermolecular hydrophobic interactions contributed by the linear aliphatic region of H93 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). These hydrogen bonds, along with non-bonded interactions, contributed to stabilizing the UHRF1SRA dimer. We then compared the UHRF1SRA dimer interface observed in this study with previously reported apo-UHRF1SRA structures (PDB ID: 3BI7)20. The dimer interface in our structure closely resembles that of the apo-UHRF1SRA dimer. The overall structures of the two dimers align closely, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.19 Å based on Cα atoms (Supplementary Fig. 3e).

H93 promotes UHRF1SRA dimerization in vitro and disrupts the UHRF1-DNMT1 interaction

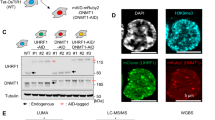

Based on the co-crystallization structure, we hypothesized that H93 may promote the dimerization of UHRF1SRA. To test this, we constructed and purified two distinct UHRF1SRA fusion proteins tagged with GST or His, allowing differentiation between individual UHRF1 proteins. By mixing GST-UHRF1SRA and His-UHRF1SRA and performing GST pull-down assays, we found that H93 significantly enhanced UHRF1SRA dimerization (Supplementary Fig. 4a). To further validate this effect in cell lines, we assessed the dimerization of full-length UHRF1. We constructed UHRF1 fusion proteins with either His or Flag tags and co-expressed them in HEK293T cells. Co-IP assays confirmed that H93 promoted the interaction between differentially tagged UHRF1 proteins, supporting its role in enhancing UHRF1 dimerization (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4b). To corroborate these findings, we employed a BiFC assay. We generated plasmids encoding fusion proteins of UHRF1 with either the C-terminal (VC155) or N-terminal (VN155) fragment of the yellow fluorescent protein Venus. These plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells along with dsRed plasmids. Upon interaction of VC155-UHRF1 and UHRF1-VN155, the Venus fragments came into close proximity, resulting in fluorescence emission (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Cells were treated with varying concentrations of H93 or for different durations, as indicated in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4d. H93 steadily increased fluorescence intensity and the proportion of fluorescence-positive cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. These findings confirm that H93 stabilizes UHRF1 dimerization and increases the abundance of UHRF1 dimers in cells.

a Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) showed that H93 promotes the protein dimerization of exogenously expressed UHRF1. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with His-UHRF1 and Flag-UHRF1 plasmids, followed by treatment with 0, 5, 10, or 20 μM of H93 for 8 h. The cell lysates were incubated with protein A/G bead-bound anti-His antibody, then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-His or anti-Flag antibodies. b HEK293T cells were co-transfected with VC155-UHRF1, UHRF1-VN155 and dsRed plasmids for 48 h and then treated with H93 (0, 5, 10 or 20 μM) for 2, 4 or 6 h. The protein interaction between VC155-UHRF1 and UHRF1-VN155 was assessed by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. The length of the scale bar is 20 μm. c HEK293T cells were co-transfected with His-UHRF1 and Myc-DNMT1 plasmids, and then treated with H93 (0, 5, 10 or 20 μM) for 8 h. Cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP using an anti-His antibody, and DNMT1 protein was assessed by immunoblotting. d DU145 (Left) or VCaP (Right) cells were treated with H93 (0, 5, 10 or 20 μM) for 8 h, and the endogenous protein interaction between UHRF1 and DNMT1 was measured by Co-IP. e H93 had no significant effect on the interaction of UHRF1 and DNMT1 when the W527, R528, and R581 residues were mutated to alanine (UHRF13A). HEK293T cells were co-transfected with myc-DNMT1 and His-UHRF1WT or His-UHRF13A plasmids for 48 h, followed by treatment with 0 or 20 μM H93 for 8 h and subjected to Co-IP. Experiments were performed in at least triplicate, and representative images are presented.

Since the SRA domain plays a crucial role in mediating the interaction between UHRF1 and DNMT1, we next examined whether H93 disrupts this interaction. We co-transfected His-UHRF1 and Myc-DNMT1 plasmids into HEK293T cells, and treated them with increasing concentrations of H93. Co-IP assays using an anti-His antibody revealed that H93 reduced UHRF1-DNMT1 interaction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 4e). To further confirm this effect in a physiological context, we assessed the impact of H93 on endogenous UHRF1-DNMT1 interactions in DU145 and VCaP cells, both of which express high levels of UHRF1 and are sensitive to H93 treatment. Co-IP experiments consistently demonstrated that H93 reduced UHRF1-DNMT1 interactions in both cell lines (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4f). BiFC assays further corroborated these results, showing that H93 inhibited the UHRF1-DNMT1 interaction in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 4g).

Since we previously demonstrated that H93 directly binds the UHRF1SRA domain (Fig. 2), we investigated whether this binding is required for its effect on UHRF1-DNMT1 interaction. We generated a UHRF1 mutant (UHRF13A) with three key residues (W527A, R528A, and R581A) mutated and assessed the impact of H93 on its interaction with DNMT1 using Co-IP. Unlike wild-type UHRF1, the UHRF13A mutant showed no further reduction in DNMT1 binding upon H93 treatment (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4h). Collectively, these results demonstrate that H93 stabilizes UHRF1 dimerization while simultaneously inhibiting the UHRF1-DNMT1 interaction by directly binding to the UHRF1SRA domain.

H93 reduced global DNA methylation levels

To further investigate the mechanism of H93-mediated UHRF1 inhibition, we examined its impact of H93 on the maintenance of DNA methylation. Total DNA 5mC levels were measured in UHRF1-high-expressing PCa cell lines (DU145 and VCaP) using dot-blotting following 48 h treatment with varying concentrations of H93. As anticipated, H93 remarkably reduced the total DNA methylation levels consistently in DU145 and VCaP cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig 5a, b). These results were further validated using ELISA-based quantification of 5mC levels, which confirmed the dose-dependent reduction in global DNA methylation level (Fig. 5b). These findings suggest that H93 may exert its anticancer efficacy by reducing DNA methylation levels, particularly in the promoter regions of TSGs downstream of UHRF1, thereby reversing TSGs’ epigenetic silencing. We tested the mRNA level of TSGs which were previously reported regulated by UHRF1, including BRCA1, RUNX3, CDH1 and CDKN1A21,22,23. The results of real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) showed that H93 elevated the gene expression of TSGs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5c). Taken together, the cell proliferation and global DNA methylation analyses highlight the potential of H93 as a therapeutic agent targeting UHRF1 highly expressed PCa.

a DU145 (Left) or VCaP (Right) cells were treated with indicated concentrations of H93 for 48 h, and the total DNA methylation level was measured by 5-methylcytosine (5mC) DNA dot-blot assays. Experiments were performed in triplicate. b DU145 (Left) or VCaP (Right) cells were treated with 0 (black dots), 10 (black squares) or 20 μM (black triangles) of H93 for 48 h, and the total DNA methylation level was measured by 5mC ELISA assays. The data are represented as the mean ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments. c Quantitated gene expression changes of representative tumor suppressor genes in DU145 (Upper) and VCaP (Lower) cells treated with 0 (empty black circles), 2.5 (black squares), 5 (black triangles), 10 (black rhombus) or 20 μM (black dots) of H93. n = 3 independent experiments. d–f DU145 subcutaneous xenografts were induced in immune-deficient nude mice, and then treated with vehicle (20 ml kg−1 day-1) or H93 (50 or 100 mg kg−1 day−1) by oral administration. n = 8 per group. The tumor nodes were harvested 28 days after treatment. d The tumor volumes (Left) and weights (Right) were compared with vehicle 20 ml kg−1 day−1 group depicted as black dots, H93 50 mg kg−1 day−1 group as black squares, H93 100 mg kg−1 day−1 group as black triangles. n = 8 animals. e The body weights of nude mice were continuously monitored and vehicle 20 ml kg−1 day−1 group was depicted as black line, H93 50 mg kg−1 day−1 group as red line, H93 100 mg kg−1 day−1 group as glaucous line. n = 8 animals. f Representative images of Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE), Ki67 immunochemistry (IHC) and transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining in DU145 xenografts subjected to different concentrations of H93 (Left), and the quantitative data of Ki67 (Middle) and TUNEL (Right) staining, with vehicle 20 ml kg−1 day−1 group depicted as black dots, H93 50 mg kg−1 day−1 group as black squares, H93 100 mg kg−1 day−1 group as black triangles, and n = 40 views. The length of scale bars is 200 μm (×100) or 50 μm (×400). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. The data are shown as mean ± SD.

H93 repressed in vivo tumor growth of PCa xenografts

Since H93 has demonstrated high potential as an anticancer drug, we assessed the in vivo anticancer effect of H93. DU145, a highly malignant AR−/PSA− PCa cell derived from an advanced PCa patient with brain metastasis, was selected to induce subcutaneous tumor xenografts in immune-deficient nude mice. Animals with tumor xenografts were divided into three groups and treated respectively with vehicle (20 ml kg−1), H93 (50 mg kg−1), or H93 (100 mg kg−1) by gavage each day. The animals were sacrificed to anatomize the tumor nodes 28 days after treatment. The relative tumor volume on Day 28 to that on Day 0 demonstrated that H93 significantly repressed tumor growth compared to the control (Fig. 5d). The data were validated by the weights of tumor nodes collected at the endpoint of experiment (Fig. 5d). Importantly, H93 did not affect the body weights of animals throughout the experiment (Fig. 5e), suggesting the safety of H93 in the further clinical trials. By using immunochemistry (IHC) of Ki67 and transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays (Fig. 5f), H93 decreased the expression level of Ki67 and increased the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells. These results suggest that H93 has a high potential for future success in clinical trials, based on its significant in vitro and in vivo anticancer activity against PCa, as well as good safety.

Discussion

UHRF1, as a key epigenetic regulator, serves as a bridge between histone modifications and DNA methylation by interacting with HDAC1 or DNMT1 proteins5,6. Epigenetic drugs, such as DNMT1 or HDAC1 inhibitors, have been widely used to treat blood malignancies. However, no UHRF1-targeted agents have been tested in clinical trials to date. Both our and other studies have demonstrated that co-targeting UHRF1 and HDAC1 exhibits synergistic anticancer efficacy in vitro17,18. Based on a rational multi-target drug design strategy, we designed and synthesized a small-molecule compound, H93, by incorporating the pyrimidine ring derived from NSC232003 with the hydrophobic tails and the Zn²⁺-chelating hydroxamic acid derived from vorinostat.

In the co-crystallization structure, we observed that H93 directly binds to the W527, R528, and R581 residues within the SRA domain of the UHRF1 protein. Mutations at these residues significantly reduced the binding strength between H93 and UHRF1SRA. We are the first group to report that the SRA domain of UHRF1 forms a dimer, a finding supported by both co-crystallization and crystallographic analyses. Interestingly, a previous study in 2011 reported that the PHD domain of UHRF1 also forms a dimer in crystal structures24. Based on existing literature and our current findings, we speculate that UHRF1 may exist as a dimer under physiological conditions, maintaining a monomer-dimer equilibrium. To our knowledge, H93 is the first compound demonstrated to directly bind to the SRA domain of UHRF1, as validated by co-crystallization. Moreover, its binding model differs from that of NSC232003, which was predicted to occupy the 5mC cavity of UHRF1 based on theoretical druggability assessments14. Furthermore, Co-IP results showed that NSC232003 did not promote UHRF1 dimerization as H93 did (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

Additionally, we clearly observed that two dimerized UHRF1SRA molecules formed a stable pocket, within which compound H93 was enclosed (Fig. 3a). The data suggested that H93 stabilizes UHRF1 dimerization by modifying the protein interface, creating an ideal drug-binding pocket that encapsulates H93 and enhances the druggability of UHRF1 as a non-kinase protein. This interaction model is not unique, as several similar mechanisms have been reported recently, highlighting a general principle of protein conformation modulation by small molecules25. For instance, small-molecule compounds induce the sequestration of PD-L1 homodimers, preventing PD-1 from binding to PD-L1 and thereby blocking downstream signal activation26. Similarly, NSC13728 and KI-MS2-008 stabilize Max-Max protein homodimers, disrupting Myc-Max heterodimer formation and its subsequent signaling27,28. However, further evidence is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms in greater depth and expand our understanding of UHRF1 protein stabilization.

DNMT1 is a DNA methyltransferase responsible for maintaining the stable inheritance of genomic methylation. UHRF1 recognizes hemi-methylated DNA following replication, recruits DNMT1 to the newly synthesized DNA, and sustains the 5mC status5,6. We found that H93 promotes UHRF1 dimerization while disrupting its interaction with DNMT1. We hypothesize that H93 may reduce the pool of monomeric UHRF1, and the dimerized UHRF1 may adopt a ‘closed’ conformation that prevents DNMT1 recruitment, thereby interfering with the maintenance of DNA methylation patterns.

H93 significantly decreases global methylation levels and may also reduce the methylation of CpG islands in the promoters of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) downstream of UHRF1. As we expected, H93 increases the mRNA level of UHRF1-regulated TSGs, such as BRCA1, RUNX3, CDH1 and CDKN1A (Fig. 5c). The in vitro cell viability after administration of H93 is negatively correlated with UHRF1 protein levels in PCa cells (Fig. 2), indicating that H93 functions as a UHRF1-targeted small-molecule inhibitor. Furthermore, H93 demonstrated significant in vivo anticancer efficacy on AR−/PSA− DU145 tumor xenografts, and high doses did not show obvious toxicity. Notably, co-administration of H93 with existing PCa therapies (e.g. enzalutamide or olaparib) synergistically induced PCa cell killing (Supplementary Fig. 6b), which indicates promising prospects for clinical application.

Besides, as a multi-target molecule, H93 inhibits the deacetylase activity of HDAC1 and HDAC6 and decreases the acetylation level of histone H3 (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6c). The interaction of H93 and class I HDACs might also play an important role in the antitumor effect of H93. Further studies are needed to explore the exact interaction of H93 and HDACs.

As an SRA-binding compound, H93 does not alter UHRF1’s histone-binding via TTD/UBL domains and PHD finger-mediated H3K9me3 recognition (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Since the high homology of SRA domains between UHRF1 and UHRF2 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 6e), H93 likely binds the SRA domains of UHRF2. We are interested in testing the binding ability of H93 to the SRA domains of UHRF2 and exploring the new functions. To enhance our comprehension of H93, we would verify whether modifying H93 prevents UHRF1 dimerization or enhances SRA binding affinity in further studies.

Conclusions

We developed a UHRF1-targeted small-molecule compound, H93, and observed that H93 directly binds to the SRA domain of UHRF1, promoting protein dimerization. The dimeric conformation of UHRF1 may hinder the maintenance of DNA methylation and exert anticancer effects.

Methods

Synthesis procedure of compound H93

The stirred solution of 8-methoxy-8-oxooctanoic acid (S102139, 8.142 g, 43 mmol) in DMSO (40 mL) was added successively 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt, 7.02 g, mmol), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI, 9.98 g, 52 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 13.41 g, 104 mmol), and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h followed by addition of 5-aminopyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (S102138, 5.00 g, 39 mmol) in a portionwise manner. The reaction was agitated at 35 °C until the reaction finished as indicated by HPLC (typically within 16 h). On cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was added to a stirred ice-water (200 mL), and the mixture thus obtained was brought to pH = 3 with concentrated hydrochloric acid. A large number of precipitates formed, and the slurry was agitated for 30 min at room temperature. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with 100 mL saturated aqueous NaHCO3, washed with 20 mL water twice, dried at 50–55 °C overnight to give methyl 8-((2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl) amino)-8-oxooctanoate (S102140, 9.40 g, 81%), which was utilized in the subsequent procedure.

S102140 (9.00 g, 30 mmol) was added portionwise to a stirred solution of NaOH (2.42 g, 61 mmol) in water (90 mL) at room temperature. Additionally, the mixture thus obtained was agitated at 30–40 °C until HPLC indicated the reaction was completed (typically within 2–3 h). On cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was brought to pH = 8.58 with concentrated hydrochloric acid. The resulting mixture was agitated with celite (2.25 g) for 2 h and filtered off; additionally the filtrate was brought to pH = 2–3 with concentrated hydrochloric acid. A large number of precipitates formed, and the slurry was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with water (20 mL × 2) and dried at 50–55 °C for 48 h to give 8-((2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl) amino)-8-oxooctanoic acid (S102142, 8.28 g, 97%), which was used directly in the next step.

To a stirred solution of S102142 (1.40 g, 4.9 mmol) in DMSO (7 mL) at 50 °C was added triethylamine (TEA, 2.25 g, 22 mmol) and THF (7 mL), and the solution thus obtained was cooled to 0–10 °C, followed by dropwise addition of ethyl chloroformate (ECF, 0.64 g, 5.9 mmol). After these procedures, the mixture thus obtained was agitated for 1 h under these conditions, followed by portionwise addition of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.03 g, 15 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 0–10 °C until the HPLC indicated the completion of the reaction (typically within 16 h). On completion, the reaction mixture was poured into water (30 mL), and a solution of NaOH (1.20 g) in water (12 mL) was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was filtered off, and the filtrate was brought to pH = 8.5–8.6 with concentrated hydrochloric acid to give a slurry, which was further stirred for 1 h. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with water (5 mL) and redissolved in 10% NaOH. After the pH was adjusted to pH = 8.5–8.6 with concentrated hydrochloric acid, the precipitates formed were collected by centrifugation, washed with water (5 mL) and dried at 50–55 °C for 48 h to give H93.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Reagents

UHRF1 inhibitor NSC232003(Cat# HY-103236), PARP inhibitor olaparib (Cat# HY-10162) and androgen receptor inhibitor enzalutamide (Cat# HY-70002) were purchased from MCE (Shanghai, China). Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Cat# B14002) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Cat#B15002) were purchased from Bimake (Shanghai, China). Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Cat#11668-027) was purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). From Beyotime Biotech (Shanghai, China) was purchased solution of crystal violet staining (Cat#C0121). Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Cat#A610037) was obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). For immunoblotting assays, mouse anti-UHRF1 (Cat#sc-373750, RRID: AB_10947236, Santa cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), rabbit anti-β-Actin (Cat#3700S, RRID: AB_2242334, CST, Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-β-Tubulin (Cat#15115S, RRID: AB_2798712, CST), mouse anti-His (Cat#A00186, RRID: AB_914704, Genscript, Nanjing, China), rabbit anti-Flag (Cat#2368 T, RRID: AB_2217020, CST), mouse anti-GST (Cat#ABM40020, RRID: AB_2895668, Abbkine, Wuhan, China), rabbit anti-DNMT1 (Cat#A00172, RRID: AB_2895667, Boster, Pleasanton, CA, USA), rabbit anti-acetylated histone 3 (Cat#8173S, RRID: AB_10949503, CST), rabbit anti-histone 3 (Cat#4499S, RRID:AB_10544537, CST), rabbit polyclonal to Histone H3 (tri methyl K9) (Cat# ab8898, RRID: AB_306848, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), goat anti-rabbit (Cat#ab205718, RRID: AB_2819160, Abcam), and goat anti-mouse (Cat#ab205719, RRID:AB_2755049, Abcam) antibodies were utilized. In the Primary Antibody Diluent Solution (Cat#P0256, Beyotime) were diluted antibodies. For Co-IP assays, mouse anti-His (Cat#A00186, Genscript) antibodies were utilized. In IHC assays, mouse anti-UHRF1 (Cat#sc-373750, RRID: AB_10947236, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-Ki-67 (Cat#9449, RRID: AB_2797703, CST) were used. All antibodies were used at the concentrations recommended by the manufacturers. Colorimetric TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Cat#C1098) was purchased from Beyotime Biotech. All compounds are >95% pure by HPLC analysis.

Biological resources

UHRF1 cDNA was respectively inserted into pBiFC-VC155 (RRID: Addgene_22011) or pBiFC-VN155 (I152L) (RRID: Addgene_27097) vectors which were utilized in BiFC assays.

Cell culture

DU145 (PCa, Cat# HTB-81, ATCC, Bethesda, MA, USA), VCaP (PCa, Cat#CRL-2876, ATCC), PC3 (PCa, Cat#CRL-1435, ATCC), CWR22Rv1 (PCa, Cat#CRL-2505, ATCC), C4-2 (PCa, Cat#CRL-3314, ATCC), LNCaP (PCa, Cat#CRL-1740, ATCC), HUVEC (human umbilical venous endothelial cells, Cat#PCS-100-013, ATCC) and HEK293T (embryonic kidney cells, Cat#CRL-1573, ATCC) cell lines were used in the experiments. The gender of the cells is male.

PCa cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cat#22400105, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). HEK293T and HUVEC cells were maintained in DMEM high-glucose medium (Cat#11965126, Thermo Fisher). Cells <20 passages were used. All cell lines were cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher, Cat#10100139 C), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin was adjusted to the medium (Thermo Fisher, Cat#15640055).

Colony formation assay

500 cells were plated in 12-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, cells were cultured in 1 mL medium containing stepwise concentrations of H93 for 7 days, and DMSO was used as a control. Medium was changed in 3-day intervals. At the end of the treatment, cells were washed 3 times with PBS buffer and fixed with paraformaldehyde, then stained with crystal violet at room temperature overnight. Before the images were acquired, the plates were washed 4 times. The crystal violet dye was solubilized by 0.1% SDS buffer, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using Perkin Elmer EnspireManager (version 4.13.3005.1482).

Extensive spectral analysis

In the 1H NMR spectrum, all five active protons (four NH and one OH) resonated at a lower field and displayed as broad singlets, respectively, which were further confirmed to be D2O-exchangable by 1H NMR with one drop of D2O in DMSO-d6. Two CH2 groups adjacent to C = O displayed as triplets with a coupling constant ranging at 7.3–7.5 Hz, respectively. The remaining four continuous CH2 groups fell into two groups, resonating at 1.44–1.52 and 1.22–1.25 ppm, respectively, and either displayed as a multiplet. For the 1H NMR spectrum, four C = O groups in amide moieties resonated at a lower field, ranging between 171.8 and 149.6 ppm. The two olefinic carbons in the uracil nucleus resonated at 129.4 and 113.3 ppm, respectively. The remaining six carbons in (CH2)6 resonated at a higher field as six separable signals at 35.4–25.0 ppm. The target molecule H93 responded well in HRMS determination in positive electrospray ionization mode (ESI+), and a [M + H]+ peak was obtained with an observed m/z consistent with the calculated one. The IR spectrum was collected as a KBr pellet, and characteristic absorption bands were observed, such as 3265 cm−1 for N–H stretching, 3031 cm−1 for Ar–H stretching and 1644 cm−1 for C = O stretching.

All the spectra were in good agreement with the proposed structure of H93. Yield: 1.03 g (70%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.37 (brs, 1H, D2O exchangable), 10.63 (brs, 1H, D2O exchangable), 10.31 (brs, 1H, D2O exchangable), 9.01 (s, 1H, D2O exchangable), 8.64 (brs, 1H, D2O exchangable), 8.04 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 2.32 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2CO), 1.92 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2CO), 1.44–1.52 (m, 4H, CH2 × 2), 1.22-1.25 (m, 4H, CH2 × 2); 13C(1H) NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 171.8 (C = O), 169.1 (C = O), 160.7 (C = O), 149.6 (C = O), 129.4 (C = CNH), 113.3 (C = CNH), 35.4 (CH2), 32.2 (CH2), 28.4 (CH2), 28.3 (CH2), 25.1 (CH2), 25.0 (CH2); Mp: 274.2–277.6 °C; HRMS (ES + ) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd 299.1350, found 299.1345; IR (KBr plate): ν = 3265 (N–H stretching), 3031 (Ar–H stretching), 2936, 2900, 2844, 1760, 1644 (C = O stretching), 1566.

Protein expression and purification

Human UHRF1 SRA domain (UHRF1SRA, residues 414–617) was cloned into the pET28a vector with a C-terminal His tag and purified as described before20. Briefly, the fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain Rosetta (DE3) and induced by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.2 mM). Cell lysates were homogenized and loaded onto a pre-equilibrated nickel affinity column. The bound protein was eluted and subjected to additional purification by a Fast S cation exchange column and a Superdex 75 column. The final UHRF1SRA protein with the C-terminal His tag was concentrated to ~10–15 mg mL−1 and stored at −80 °C for use.

Site-directed mutagenesis

UHRF1SRA mutants were generated with the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Cat# C112-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) using the pET28a-UHRF1SRA and pGEX-6p1-UHRF1SRA plasmids as templates. All the mutants were validated by DNA sequencing in Tsingke (Beijing, China). The mutant or wild-type UHRF1SRA proteins were prepared for further experiments.

ITC assay

UHRF1SRA protein and H93 were diluted in the running buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.1% DMSO). The ITC experiments were performed on a Nano ITCRun software (version 3.8.6) (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) to measure the binding avidity of UHRF1SRA and H9329. H93 (50 µM) was adjusted to the solvents comprising 10–40 µM UHRF1SRA protein. 50 mL of H93 was injected into the sample cell containing UHRF1SRA protein or running buffer using 2 μL injections with 300 s intervals. We used the NanoAnalyze software to analyze the titration data using an independent sample model. All titrations were performed in independent experiments at least twice.

Crystallization and structure determination

UHRF1SRA and H93 were mixed with a molar ratio of 1:3. Crystals of H93/UHRF1SRA were grown at 18 °C by the hanging-drop method with a reservoir buffer of 0.1 M Bris-Tris, pH 6.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 2.2–2.4 mM ammonium sulfate. For data collection, a single crystal was soaked in a well solution plus 20% (v/v) glycerol and 5% sucrose and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at a wavelength of 0.98 Å and at the BL19U1 beamlines of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF)30. The data were processed using HKL200031. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with a phaser from the PHENIX package (version 1.20.1-4487) using the previously solved UHRF1SRA structure (PDB: 3BI7) as a search template20,32. Then the structure was refined with phenix.refine and model building was performed using WinCoot33. Translational liberation-screw (TLS) refinement was used during the last stages of refinement. The final structure was deposited in the PDB database (8JIG). The interactions between H93 and UHRF1SRA were analyzed by LigPlot+19. The interactions in UHRF1SRA dimer were analyzed by PDBsum34. Graphic representations of the structure were generated using PyMOL35. Data collection and refinement statistics of the crystallographic analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

His pull-down

The purified GST-UHRF1SRA proteins were incubated with His-UHRF1SRA proteins in PBS buffer containing 1 mM TCEP at 4 °C for 0.5 h. Then the complex was incubated with 0, 5 or 10 μM H93, respectively, at 4 °C for 0.5 h. The mixture was incubated with 20 μL nickel beads (GE Healthcare, Marlborough, MA, USA) at 4 °C for 10 min, and then the nickel beads were washed with PBS buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP and 1% Triton X-100, suspended in 100 μL of protein loading buffer and loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. GST-UHRF1SRA proteins were detected by western blotting with anti-GST antibody, and His-UHRF1SRA was detected with anti-His tag antibody.

GST pull-down

pGEX-4T-1-UHRF1 plasmid was constructed using the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene fusion system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, to produce GST and GST-UHRF1 fusion protein, pGEX-4T-1 or pGEX-4T-1-UHRF1 plasmids were transfected into BL21 competent cells. Protein expression was induced by IPTG. GST-UHRF1 and GST proteins were purified by binding to GST-sefinose resins (Cat#C600031, Sangon Biotech). Resins were incubated with cell lysates from HEK293T cells overexpressing the indicated plasmids on a 4 °C spinner overnight, and washed with GST washing buffer (Cat#C600326, Sangon Biotech) for 4 times. Resin-binding proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. Cell lysates were incubated with the indicated antibodies at 4 °C overnight, and then supplemented with protein A/G magnetic beads (MCE, Cat# HY-K0202) on a 4 °C spinner for 1 h. After incubation, beads were collected and washed 4 times in RIPA buffer and heated in SDS loading buffer. Protein samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed and protein concentrations were measured with a Bradford assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 23236). 20 μg proteins of each sample were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE gel, and then transferred to PVDF membranes (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, Cat# ISEQ00010). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Images were taken by the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and Bio-Rad Image Lab (version 3.0).

BiFC assay

To validate the effect of H93 on the protein interaction of UHRF1 and DNMT1, BiFC assays were conducted according to the protocol of Dr. Hu’s laboratory36. In brief, plasmids encoding UHRF1 fused to VC155 and UHRF1 fused to VN155 (I152L) or DNMT1 fused to VN155 (I152L) were constructed and transfected into HEK293T cells using LipofectamineTM 2000 Transfection Reagent. Meanwhile, plasmids encoding dsRed were transfected as an internal control for ratio analysis. 48 h after transfection, culture media were replaced with the indicated concentration of H93 or DMSO. YFP and CFP images from the same fields of transfected cells were acquired at the indicated time using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope and ZEISS ZEN (version 3.7). The fluorescence intensity of 100 cells per sample was quantified, and the YFP/CFP ratio of individual cells was calculated.

DNA Dot-blot assay

Genomic DNA was extracted using a genomic DNA purification kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (CoWin Biosciences, Beijing, China). Genomic DNA was denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, and 100 ng of DNA with a volume of 2 μL of each sample was blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. After air-drying, DNAs were fixed at 80 °C for 30 min. The membrane was incubated in 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 h, and then with anti-5-methylcytosine or anti-5-hydroxymethylcytosine antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washing, the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h, and then visualized by chemiluminescence. Methylene blue intensity was used to determine the amount of DNA.

ELISA of DNA 5mC

DNA methylation was quantified using the MethylFlashTM Methylated DNA Quantification Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Epigentek Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA). Briefly, 100 ng of input DNA were used per reaction. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured by a microplate reader (Multiskan-GO, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA from DU145 and VCaP cells was extracted using RNAiso Plus (TAKARA, Kusatsu, Japan, Cat# 9108). cDNA was synthesized with RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat# K1621). RT-qPCR was performed using Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch, and data were analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager (version 2.1). Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate. The mRNA expression levels were determined as fold change by 2−ΔΔCT method (2−(∆CT) treated cells/2−(∆CT) control), and the data were normalized to β-Actin.

The RT-qPCR primer sequences in this study were as follows: β-Actin (Forward, 5’-CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC-3’; Reverse, 5’-AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCA CGT-3’); BRCA1 (Forward, 5’-GAAACCGTGCCAAAAGACTTC-3’; Reverse, 5’-CCAAGGTTAGAGAGTTGGACAC-3’); RUNX3 (Forward, 5’-AGGCAATGAC GAGAACTACTCC-3’; Reverse, 5’-CGAAGGTCGTTGAACCTGG-3’); CDH1 (Forward, 5’-CGAGAGCTACACGTTCACGG-3’; Reverse, 5’-GGGTGTCGAGGGA AAAATAGG-3’); CDKN1A (Forward, 5’-TGTCCGTCAGAACCCATGC-3’; Reverse, 5’-AAAGTCGAAGTTCCATCGCTC-3’).

Ethics statement

All experiments involving animals were conducted according to the ethical policies and procedures approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Pharmaceutical, China (Approval no. 20220110-0012).

Animal experiments

To construct a PCa formation model, 8-week-aged male Balb/c nude mice were raised in a specific pathogen free (SPF) environment with 4 mice per individually ventilated cage. To validate the in vivo anti-tumor effect of H93, DU145 cells were subcutaneously injected into the dorsal flanks of mice, with 8 × 106 cells per mouse. After tumor formation, the animals with similar body weight and tumor size were randomly assigned to 3 groups (n = 8 per group), and individually treated by oral gavage with H93 (50 or 100 mg kg−1 day−1) or vehicle control (20 ml kg−1 day−1) for a continuous 28 days. Measurements of body weight were taken at 3-day intervals. Xenograft tumors were excised for analysis after sacrifice.

IHC assay

For IHC staining, tissue sections were dewaxed in water after xylene and gradient ethanol. The sections were heated in a pH 8.0 Tris-EDTA antigen-repairing buffer and then blocked by 3% H2O2 and goat serum. In turn, slides were incubated with specific primary and secondary antibodies successively and stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB).

TUNEL assay

For the TUNEL assay, tissue sections were dewaxed to water by xylene and gradient ethanol, and digested by proteinase K at 37 °C for 30 min. After blocking peroxidase with 3% H2O2, slides were incubated with biotin labeling solution and streptavidin-HRP solution in order, and finally stained with DAB.

HDACs fluorogenic assay

The inhibition effect of H93 on the deacetylase activity of class I HDACs was measured by the Fluorogenic HDAC1-6 Assay Kit (Cat#50061/50062/50073/50064/50065 /50076, BPS Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the HDAC fluorometric substrate, containing an acetylated lysine side chain, is incubated with purified HDAC enzyme and different concentrations of H93, and the deacetylation produces a fluorophore that can then be measured using SpectraMax M5 multi-Mode Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by the CCK-8 kit (Cat# E606335, Sangon Biotech), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5000 cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. After 3 days of treatment, cells were incubated with 10 μL CCK-8 and 100 μL medium at 37 °C for 2 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using Perkin Elmer EnspireManager (version 4.13.3005.1482).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 9 software, and greyscales were measured using ImageJ (version 1.44p). Measurements were taken from distinct samples. We calculated the first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), and interquartile range (IQR) using the interquartile range method. Data points that fell outside the range of Q1−3 × IQR or Q3 + 3×IQR were excluded. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-test was used to analyze two groups of data with normal distribution. The data met the assumption of normality (p > 0.05, Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (p > 0.05, Levene’s test). IC50 values were determined using a dose-response nonlinear regression model, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated via linear regression. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. p-values were two-sided.

Data availability

Compound H93 generated in this study will be made available on request, but we may require a completed materials transfer agreement if there is potential for commercial application. The structure factors and coordinates for the UHRF1SRA /H93 complex have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank with the accession code 8JIG. For NMR spectra of H93, see Supplementary Data 1. For other source data, see Supplementary Data 2. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Sathianathen, N. J. et al. Indirect comparisons of efficacy between combination approaches in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 77, 365–372 (2020).

Komura, K. et al. Current treatment strategies for advanced prostate cancer. Int. J. Urol. 25, 220–231 (2018).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1995–2005 (2011).

Scher, H. I. et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1187–1197 (2012).

Unoki, M., Nishidate, T. & Nakamura, Y. ICBP90, an E2F-1 target, recruits HDAC1 and binds to methyl-CpG through its SRA domain. Oncogene 23, 7601–7610 (2004).

Bostick, M. et al. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science 317, 1760–1764 (2007).

Babbio, F. et al. The SRA protein UHRF1 promotes epigenetic crosstalks and is involved in prostate cancer progression. Oncogene 31, 4878–4887 (2012).

Wan, X. et al. UHRF1 overexpression is involved in cell proliferation and biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 35, 34 (2016).

Unoki, M. Current and potential anticancer drugs targeting members of the UHRF1 complex including epigenetic modifiers. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 6, 116–130 (2011).

Alhosin, M. et al. Down-regulation of UHRF1, associated with re-expression of tumor suppressor genes, is a common feature of natural compounds exhibiting anti-cancer properties. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 41 (2011).

Ashraf, W. et al. Natural and synthetic anticancer epidrugs targeting the epigenetic integrator UHRF1. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 28, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28165997 (2023).

Liu, W. H. et al. Discovery and mechanism of small molecule inhibitors selective for the chromatin-binding domains of oncogenic UHRF1. Biochemistry 61, 354–366 (2022).

Hu, C. L. et al. Targeting UHRF1–SAP30–MXD4 axis for leukemia initiating cell eradication in myeloid leukemia. Cell Res. 32, 1105–1123 (2022).

Myrianthopoulos, V. et al. Tandem virtual screening targeting the SRA domain of UHRF1 identifies a novel chemical tool modulating DNA methylation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 114, 390–396 (2016).

Szumilak, M., Wiktorowska-Owczarek, A. & Stanczak, A. Hybrid drugs—a strategy for overcoming anticancer drug resistance? Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 26, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092601 (2021).

Li, X., Li, X., Liu, F., Li, S. & Shi, D. Rational multitargeted drug design strategy from the perspective of a medicinal chemist. J. Med. Chem. 64, 10581–10605 (2021).

Niinuma, T. et al. UHRF1 depletion and HDAC inhibition reactivate epigenetically silenced genes in colorectal cancer cells. Clin. Epigenet. 11, 70 (2019).

Yin, L. et al. PARP inhibitor veliparib and HDAC inhibitor SAHA synergistically co-target the UHRF1/BRCA1 DNA damage repair complex in prostate cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37, 153 (2018).

Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 2778–2786 (2011).

Avvakumov, G. V. et al. Structural basis for recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA domain of human UHRF1. Nature 455, 822–825 (2008).

Zhou, L. et al. UHRF1 promotes proliferation of gastric cancer via mediating tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 1241–1251 (2015).

Aibara, D. et al. Gene repression through epigenetic modulation by PPARA enhances hepatocellular proliferation. iScience 25, 104196 (2022).

Obata, Y. et al. The epigenetic regulator Uhrf1 facilitates the proliferation and maturation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 15, 571–579 (2014).

Hu, L., Li, Z., Wang, P., Lin, Y. & Xu, Y. Crystal structure of PHD domain of UHRF1 and insights into recognition of unmodified histone H3 arginine residue 2. Cell Res. 21, 1374–1378 (2011).

Bailly, C. & Vergoten, G. Protein homodimer sequestration with small molecules: focus on PD-L1. Biochem. Pharm. 174, 113821 (2020).

Guzik, K. et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) interaction via transiently induced protein states and dimerization of PD-L1. J. Med. Chem. 60, 5857–5867 (2017).

Carabet, L. A., Rennie, P. S. & Cherkasov, A. Therapeutic inhibition of Myc in cancer. Structural bases and computer-aided drug discovery approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010120 (2018).

Follis, A. V., Hammoudeh, D. I., Daab, A. T. & Metallo, S. J. Small-molecule perturbation of competing interactions between c-Myc and Max. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 807–810 (2009).

Chen, X. et al. Structural basis for DNA recognition by FOXC2. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 3752–3764 (2019).

Zhang, W.-Z. et al. The protein complex crystallography beamline (BL19U1) at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 170 (2019).

Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 (1997).

Adams, P. D. et al. The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods (San Diego, CA) 55, 94–106 (2011).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Laskowski, R. A., Jabłońska, J., Pravda, L., Vařeková, R. S. & Thornton, J. M. PDBsum: structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 27, 129–134 (2018).

Bramucci, E., Paiardini, A., Bossa, F. & Pascarella, S. PyMod: sequence similarity searches, multiple sequence-structure alignments, and homology modeling within PyMOL. BMC Bioinform. 13, S2 (2012).

Shyu, Y. J., Liu, H., Deng, X. & Hu, C.-D. Identification of new fluorescent protein fragments for bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis under physiological conditions. Biotechniques 40, 61–66 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Changdeng Hu at Purdue University for providing the plasmids for BiFC assays. We also thank the staff from the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation facility beamlines BL17U/BL19U/BL02U/BL10U/BL17B for assistance during diffraction data collection. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81572542, 81874096, 81974074, 82172654); Research Project of Key Discipline of Guangdong Province (grant number 2019GDXK0010); National Key Specialty Construction Project of Clinical Pharmacy, High Level Clinical Key Specialty of Clinical Pharmacy in Guangdong Province (grant number 2018RS3026); Key Engineering Team, Discipline Cultivation Projects, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University (grant number 2024ZZ10) and Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department (grant number 2021RC4012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: L.X. and C.Y.H. Investigation: F.Y.X., J.L.Y., X.G.J., P.Y.C., F.Y.M., Z.Q.L., L.Y.H., Z.G.L., L.X.K., and P.Y.B. Writing-original draft: F.Y.X. and J.L.Y. Resources: C.Y.H. and L.X. Supervision: C.Y.H. and L.X. Funding acquisition: C.Y.H. and L.X. Writing-review and editing: F.Y.X., J.L.Y. C.Y.H., and L.X.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Guan-Jun Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Y., Jiang, L., Xie, G. et al. A Hybrid compound H93 treats prostate cancer by directly binding UHRF1 and promoting protein dimerization. Commun Chem 8, 356 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01744-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01744-3