Abstract

CYP3A4 metabolizes a significant proportion of all approved drugs in the human body. However, the mechanism by which substrates access the catalytic center in concert with conformational changes remains unresolved. Here, we captured spontaneous substrate-binding events from outside the enzyme to the catalytic center of CYP3A4 using long-timescale, unbiased MD simulations. During each entry process, the ligand initially resided on the surface of CYP3A4 with the F–F′ loop oriented downward for over 5 μs. The F–F′ loop then moved upward to permit substrate entry and restricts its exit. After entry, the substrate underwent a conformational rearrangement, while the F–F′ loop began to move downward again. One of the final bound poses closely resembled the experimentally determined conformation. The dissociation constant derived from a Markov state model agreed well with experimental data. Overall, our work provides an atomistic, dynamic view of the substrate entry mechanism in CYP3A4.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How do substrates access active sites buried deep within enzymes? This question is crucial, as substrate entry can influence catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and reaction selectivity. Although experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provide valuable structural insights, they cannot capture the dynamic details of substrate entry. Computational methods, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, therefore play a complementary role by offering continuous trajectories of ligand-binding events, along with detailed insights into key intermediate conformations and transient access tunnels1,2. For instance, Ayaz and colleagues used classical MD simulations to investigate the binding of the drug imatinib to Abl tyrosine kinase3, revealing significant conformational changes involving approximately 20 residues in the activation loop. In the case of cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s), unbiased MD simulations by Follmer et al. showed that camphor enters the active site of bacterial P450cam (CYP101A1) through an allosteric mechanism4, while Ahalawat and Mondal demonstrated that camphor recognition by CYP101A1 occurs exclusively via a single, well-defined pathway in which displacement of Phe87, rather than large-scale protein opening, was key to substrate entry5. Fischer and Smieško applied unbiased MD simulations to study substrate access to membrane-bound human CYP2D6 by placing acetaminophen, butadiene, chlorzoxazone, debrisoquine, or propofol in the simulation box, and found that substrate entry is relatively easier for the allelic variant CYP2D6*53 than for the wild type6. Although such simulations have been successful for relatively small and rigid substrates, substrate entry remains a largely intractable event within the typical timescale of unbiased simulations, particularly for large, flexible substrates that may require specific protein motions for access. The exisitence of multiple substrate entry tunnels in human P450s further complicate the problem. Consequently, most studies to date have employed biased MD simulations to accelerate substrate-binding events7,8,9,10. While these biasing approaches are highly effective at promoting substrate transport, they may introduce artifacts, as both substrate behavior and protein conformational changes can be inadvertently influenced by the applied biasing forces3,11,12. Thus, a persisting dilemma is that although unbiased MD simulations are more desirable for elucidating the intrinsic substrate-binding mechanisms, they remain especially challenging for human P450s.

Human P450s play a crucial role in the biosynthesis of endogenous compounds and in the metabolism of most drugs and environmental xenobiotics, through alkane hydroxylation and other oxidative transformations13,14,15,16. For these reactions to proceed, substrates must first enter the deeply buried, heme-containing active site. Following catalysis, the resulting products must exit the catalytic site to permit subsequent substrate turnover. In the catalytic cycle of P450s, electrons, protons, and molecular oxygen are required to generate the high-valent iron–oxo species known as compound I13,16,17,18. In microsomal P450s, electron transfer from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) is mediated by NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, while protons are delivered through hydrogen-bond networks involving amino acid residues and water molecules19,20,21. To facilitate substrate entry and product release, human P450 structures typically contain multiple tunnels, which contribute to substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency by accommodating a range of molecular shapes22,23,24. A more detailed understanding of substrate-binding pathways would deepen mechanistic insights into P450 function by clarifying the roles of individual tunnels and the influence of protein motions on substrate binding, as well as enabling the estimation of transport kinetics25,26. Such knowledge provides a dynamic perspective on metabolic processes that critically shape the pharmacokinetic profiles of drugs and is expected to enhance drug development strategies beyond static views of substrate-binding poses.

Among all P450s, CYP3A4 is particularly important because it metabolizes a significant proportion of all approved drugs27. Williams et al. reported, based on crystallographic analysis, that the active site volume of CYP3A4 is approximately 520 ų, suggesting that the site is not inherently very large and that conformational changes may be required for accommodating bulky ligands28. It has also been shown that two ligands can bind simultaneously within the active site of CYP3A429,30. To detect structural changes upon substrate binding, Ekroos and Sjögren determined crystal structures of CYP3A4 complexed with ketoconazole and erythromycin29. Their analysis revealed that the enzyme is highly flexible, with the active-site volume increasing by over 80% upon ligand binding. Significant conformational changes were observed in the F–G region (including helices F and G and the intervening loops), the C-terminal loop, and helix I (colored regions in Fig. 1a), while the F–F′ loop remained unresolved due to low electron density. In a separate study, Skopalík et al. used MD simulations at both room temperature (298.15 K) and elevated temperature (398.15 K) to compare structural flexibility across CYP2A6, CYP2C9, and CYP3A431. Their results indicated that CYP3A4 is the most flexible, which may contribute to its broad substrate specificity. These features contrast with those of P450cam, for which unbiased MD simulations showed no significant conformational changes during camphor binding5. This difference may be attributed to the intrinsically rigid nature of P450cam or to the small size of camphor (only 11 heavy atoms), which allows it to access the active site without inducing notable structural rearrangements. Therefore, elucidating conformational changes of CYP3A4 during the binding of relatively large substrates using unbiased MD simulations remains a challenging but important objective, and careful substrate selection is crucial for such studies.

a Overall structure of CYP3A4 complexed with 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin (DHB) (PDB ID 6OOB), compared with its apo form (PDB ID 1TQN)34,35. The DHB-bound structure is shown in gray, with the F–G region (residues 202–258) highlighted in red, helix I (residues 291–323) in green, and the C-terminal loop (residues 464–490) in blue. The corresponding regions in the apo structure (white) are rendered with lighter shading for comparison. The side chains of the F–F′ loop are displayed and show close alignment between the two structures. DHB is shown in yellow. b Chemical structure of DHB with atoms C26 and O06 labeled.

Among all compounds catalyzed by CYP3A4, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin (DHB), which contains 27 heavy atoms, is of moderate size (Fig. 1b). DHB is a furanocoumarin found in grapefruit, featuring a psoralen head and a dihydroxylated carbon tail32. Upon oxidation of its furan ring, DHB forms a reactive metabolic intermediate that contributes to the mechanism-based inactivation of CYP3A4. We recently investigated this reaction using hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, which revealed that the metabolism preferentially produces a γ-ketoenal metabolite33. A crystal structure of CYP3A4 complexed with DHB has been resolved, revealing that DHB binding induces only subtle structural changes relative to the apo form (Fig. 1a)34,35. The overall root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the DHB-bound and apo structures is 0.37 Å, while the RMSD for the F–F′ loop is 0.22 Å. The previously identified flexible regions in both structures are well aligned, as are the side chains of the F–F′ loop. DHB is neither too large to access the active site nor too small to induce conformational dynamics, making it a suitable model for studying substrate entry into CYP3A4 via unbiased MD simulations.

Computational studies have provided valuable insights into substrate entry and exit pathways in CYP3A4 through biased MD simulations. Fishelovitch et al. employed steered MD (sMD) simulations to examine the egress of temazepam and 6β-hydroxytestosterone through six pathways, revealing that these metabolites exhibit different preferences for specific exit routes36. In these pathways, π-stacked phenylalanine residues act as key gatekeepers, and product egress requires disruption of hydrophobic interactions within the active site. Another study by Paloncýová et al., using bias-exchange metadynamics, investigated the extraction of 1,3,7-trimethyluric acid (TMU) from the CYP3A4 active site and demonstrated that enzyme flexibility is crucial for TMU permeation37. The study identified the solvent channel, typically closed in classical MD simulations, as the energetically preferred escape route. In addition, Hackett examined testosterone binding to CYP3A4 through large-scale accelerated MD simulations38. Despite these advances, no study to date has captured the spontaneous substrate-binding process to CYP3A4 using unbiased MD simulations.

Here, we aim to elucidate the complete substrate-binding pathway—from the exterior to the deeply buried catalytic center of CYP3A4—by performing multiple long-timescale, unbiased MD simulations. These simulations provide atomistic insights into the substrate-entry dynamics and enable us to identify a critical conformational change that facilitates this process. We further employ sMD simulations and umbrella sampling to quantify the free-energy barriers associated with DHB dissociation both in the presence and in the absence of this conformational change, thereby assessing its impact on substrate transport and stabilization within the active site. Finally, we construct a Markov state model (MSM) to characterize the dynamic interconversion among distinct states defined by different substrate positions along the entry tunnel, and to compare the predicted dissociation constant (Kd) with the experimental value.

Results

DHB binding scheme

Figure 2a schematically illustrates the workflow of our MD simulations, where each dark gray line represents an individual trajectory. After approximately 11 μs of simulation from the initial structure, the F–F′ loop underwent an upward movement in the first three sets of MD simulations. Parallel and independent simulations were subsequently initiated from these F–F′-up conformations to increase the likelihood of DHB entry. Two of these simulations successfully captured the DHB binding process via distinct tunnels, represented by the connected red lines and labeled trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4, each totaling 15 μs in simulation time (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2, respectively). Subsequently, additional parallel simulations were performed based on these two trajectories. In trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4 (Fig. 2b, c), the DHB molecule transitioned from the free to the bound state, with the color gradient (from red to blue) indicating its positional changes over time. The figures also show the time evolution of the distances between the heme iron and the C26/O06 atoms of DHB, together with snapshots of key conformational states.

a Top: Schematic representation illustrating the upward movement of the F–F′ loop during DHB binding. Bottom: Overview of the MD simulations. Each line represents an individual trajectory, and each orange dot denotes an initial structure from which parallel simulations were initiated. Red lines indicate the two binding trajectories, labeled 0-1-3 and 0-2-4, each spanning 15 μs. b, c Left: DHB transitions from the free to the bound state in trajectories 0-1-3 (b) and 0-2-4 (c), with a red-to-blue color gradient indicating the time-dependent positional change of DHB. Right: Time evolution of Fe–C26 and Fe–O06 distances during the simulations. Key conformational states are labeled with Roman numerals I–IV, corresponding to snapshots shown in (d, e). Snapshots of DHB binding poses from trajectory 0-1-3 (d) and 0-2-4 (e), corresponding to the numbered states in (b, c). The entry tunnel is colored cyan for trajectory 0-1-3 (d) and yellow for trajectory 0-2-4 (e). The F–F′ loop is highlighted in green, and a portion of the B–C loop in magenta.

Initially, DHB molecules were randomly placed, with the starting configuration shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. In trajectory 0-1-3, DHB began far from the tunnel entrance (state I in Fig. 2d) and subsequently migrated into the active site via the cyan-colored tunnel (tunnel 2b)23. Before reaching the catalytic center, DHB was stabilized at the entrance of tunnel 2b (state II in Fig. 2d). As binding progressed, the F–F′ loop moved upward, and DHB underwent a conformational rearrangement to enter the catalytic center (state III in Fig. 2d). Ultimately, DHB became trapped in the active site (state IV in Fig. 2d), as indicated by shortened Fe–O06 and Fe–C26 distances.

We used the same initial structure (Supplementary Fig. 1) for energy minimization in trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4. However, the subsequent equilibration steps produced different equilibrated structures, and each resulting structure was used as the first frame for the production MD phase. In trajectory 0-2-4, before reaching the active site, the DHB molecule remained positioned at the entrance of tunnel 2a (state I in Fig. 2e)23. It then migrated into the catalytic center via the yellow tunnel, in contrast to the cyan tunnel utilized in trajectory 0-1-3. This yellow tunnel features two entry points: the left corresponds to the solvent channel, and the right connects to tunnel 423. The classification of the transport pathways, including the solvent channel and tunnels 2a, 2b, and 4, follows the scheme described by Cojocaru et al.23. Initially, DHB attempted to enter the active site via the right-side branch of the yellow tunnel (state II in Fig. 2e), as evidenced by decreases in the Fe–C26 and Fe–O06 distances. The preferential use of this right-side entrance in the bifurcated tunnel may be attributed to the presence of a nearby phenylalanine cluster28. However, rather than proceeding directly to the active site, DHB briefly resided in the left-side branch near the junction during the trajectory (Supplementary Movie 2), which triggered an upward shift of the F–F′ loop (state III in Fig. 2e). Thus, although the right-side yellow tunnel was primarily used (Fig. 2c), the transport pathway of DHB in trajectory 0-2-4 was not strictly linear. Finally, DHB rapidly approached the catalytic center (state IV in Fig. 2e). In both trajectories, DHB followed distinct tunnels yet ultimately became stably bound within the CYP3A4 active site.

DHB resides on the protein surface for an extended time before entering the active site, with the F–F′ loop oriented downward

Before entering the active site, in both trajectories, the DHB molecule remained associated with the protein surface for an extended period, during which the F–F′ loop adopted a downward-oriented conformation. In trajectory 0-1-3, between 4.6 and 9.6 μs of simulation time, DHB was stably positioned at the entrance of the cyan tunnel (Fig. 3a). During this period, the structure remained relatively stable, as reflected by only minor fluctuations in the distances between the heme iron and the C26/O06 atoms of DHB (Fig. 3b). This stabilization was likely due to interactions with nearby residues and a neighboring DHB molecule: the bound DHB formed hydrogen bonds with residues R106 and Q79, along with both a hydrogen bond and a π–π interaction with the adjacent DHB molecule (Fig. 3c). Although the F–F′ loop fluctuated during this period, it consistently maintained a downward-oriented conformation. These strong interactions stabilized DHB at the entrance of the cyan tunnel, retaining its position for approximately 5 μs while the F–F′ loop remained in the downward-oriented state.

In trajectory 0-1-3, DHB is stabilized at the entrance of the cyan tunnel (tunnel 2b) from 4.6 to 9.6 μs (a), while in trajectory 0-2-4, it is stabilized at the entrance of tunnel 2a (between helices A′ and F′) from 0 to 7 μs (d). The F–F′ loop is shown in green, and part of the B–C loop is colored magenta. Multiple colored F–F′ loops illustrate positional changes, and a color gradient traces the time-dependent positional change of DHB. Time evolution of the Fe–C26 and Fe–O06 distances, as well as the F–F′ loop RMSD, is shown for the 4.6–9.6 μs interval in trajectory 0-1-3 (b) and the 0–7 μs simulation in trajectory 0-2-4 (e). c Representative structure of bound DHB (pink), stabilized by nearby residues R106 and Q79, as well as by another DHB molecule (yellow) in trajectory 0-1-3. Hydrogen bonds are indicated. f Representative structure of bound DHB stabilized by residue Y53 in trajectory 0-2-4.

A similar phenomenon was observed in trajectory 0-2-4, where the DHB molecule remained located at the entrance of tunnel 2a (between helices A′ and F′) from 0 to 7 μs of simulation (Fig. 3d). The conformational fluctuations of DHB were more pronounced in trajectory 0-2-4 than in trajectory 0-1-3, as indicated by the larger positional displacements of the DHB molecule over time in Fig. 3d and the greater fluctuations in the Fe–C26 and Fe–O06 distances shown in Fig. 3e. In one representative structure, the bound DHB molecule formed a T-shaped π–π interaction with residue Y53 (Fig. 3f). However, this interaction was insufficient to stabilize the DHB conformation to the same extent observed in trajectory 0-1-3. The movement of the F–F′ loop was similar to that in trajectory 0-1-3: it fluctuated throughout the simulation but consistently remained in a downward-oriented conformation (Fig. 3d). In summary, DHB was stabilized at the entrance of either tunnel 2b or 2a for extended periods, with the F–F′ loop maintaining the downward-oriented conformation throughout.

After DHB’s residence, the F–F′ loop moves upward, facilitating DHB binding and preventing its exit

After DHB’s residence on the surface of CYP3A4, the F–F′ loop began to move upward, while DHB remained bound to the surface with positional or conformational changes. To characterize this behavior, we analyzed the Fe–O06 distance and the RMSD of the F–F′ loop for both trajectories. In the wheat-colored regions of Fig. 4a, b, the F–F′ loop retained a downward-oriented conformation, and the DHB molecule remained surface-associated, as illustrated by the wheat-colored F–F′ loop and DHB structures in Fig. 4c, d. In the segments corresponding to the white regions in Fig. 4a, b, the F–F′ loop transitioned to an upward-oriented state, as indicated by a marked increase in RMSD and the green-colored F–F′ loop shown in Fig. 4c, d. However, the minimal change in DHB position suggests that DHB had not yet entered the active site in these intervals. Even in the trajectory where the DHB molecule ultimately failed to access the active site, a similar phenomenon occurred: DHB remained near the entrance of tunnel 2a, as seen in trajectory 0-2-4, and the F–F′ loop transitioned upward after approximately 11 μs of simulation, remaining in the upward-oriented conformation thereafter (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Time evolution of the Fe–O06 distance and F–F′ loop RMSD in trajectories 0-1-3 (a) and 0-2-4 (b). Trajectory frames were aligned to the crystal structure prior to RMSD calculation. The F–F′ loop adopts a downward-oriented conformation in the wheat-colored region and transitions upward after the wheat-white boundary, maintaining an upward-oriented conformation thereafter. The DHB molecule remains on the surface of CYP3A4 before the purple region and becomes trapped in the active site within the purple region. Structural comparison between the wheat–white boundary state and the dashed-point state in trajectories 0-1-3 (c) and 0-2-4 (d). Wheat-colored F–F′ loops and DHB molecules correspond to the wheat–white boundary in (a, b), while green-colored F–F′ loops and DHB molecules represent the structures at the dashed points. Structural comparison between the dashed-point state and the white–purple boundary state in trajectory 0-1-3 (e) and trajectory 0-2-4 (f). Pink-colored F–F′ loops and DHB molecules correspond to the white–purple boundary in (a, b). The side chain of R212 is explicitly shown.

The upward movement of the F–F′ loop subsequently facilitated DHB entry while simultaneously hindering its exit. At the interface between the purple- and white-colored regions in Fig. 4a, b, the DHB molecule began to become confined within the F–G region, particularly the F–F′ loop (Fig. 4e, f). In this conformation, the F–F′ loop blocked DHB departure in trajectory 0-1-3 (Fig. 4e), while the bound DHB would sterically clash with the F–F′ loop in the crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 3c), indicating that loop displacement is required for substrate access to the active site. Notably, displacement of key side chains in the F–F′ loop plays a pivotal role in DHB entry into CYP3A4. In particular, the upward reorientation of the side chain of R212 is crucial for DHB entry in both trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). During attempted entry into the active site in trajectory 0-2-4 (state II in Fig. 2e), the downward orientations of residues R212 and L216 on the F–F′ loop impeded DHB access (Supplementary Fig. 5c and Supplementary Movie 2). However, when the side chains of R212 and L216 reoriented upward, DHB access into the catalytic center was facilitated (Supplementary Fig. 5d and Supplementary Movie 2). In trajectory 0-2-4, the entrance tunnel was defined by the upward-oriented F–F′ loop (Fig. 2e), and DHB entry directly induced further upward displacement of the loop (Fig. 4b, f), resulting in higher RMSD values and more pronounced conformational changes in the F–F′ loop compared to trajectory 0-1-3. Although the bound molecule in trajectory 0-2-4 did not clash with the F–F′ loop in the crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 3f), the F–F′ loop remained indispensable for both DHB entry and its retention within the active site. Because the movement of the F–F′ loop preceded DHB access and contributed to both promoting entry and preventing exit, we propose that this conformational change is a key determinant of DHB binding.

We examined RMSD fluctuations of other key loops potentially involved in DHB binding (Supplementary Fig. 6). Among these loops, the F–F′ loop exhibited the largest conformational change as reflected by its RMSD profile. Although the E–F loop also showed fluctuations, its crystal structure was incomplete and had to be reconstructed using MODELLER39,40, which may have influenced its RMSD values. In contrast, the F–F′ loop was fully resolved in the crystal structure35, confirming that its large movement resulted directly from the MD simulations with DHB bound. Additionally, we compared the crystal structures with representative structures from the purple regions of trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4 (Supplementary Fig. 7). An upward-oriented conformation of the F–F′ loop was also observed in the clotrimazole-bound crystal structure (PDB ID: 8SPD)41. The RMSD values of the F–F′ loop were smaller between these representative structures and 8SPD than between them and 6OOB (DHB-bound). Notably, the side chain of R212 on the F–F′ loop pointed downward in 6OOB but upward in both 8SPD and the representative structure, even though only the β-carbon of the side chain of R212 was resolved in 8SPD (Supplementary Fig. 7). These findings support the robustness of the conclusion that the F–F′ loop undergoes upward movement during substrate binding, as captured by our simulations.

To evaluate the energetic role of the F–F′ loop, we performed sMD simulations42,43 to pull the DHB molecule out of the active site along the binding tunnels identified in trajectories 0-1-3 and 0-2-4 (Fig. 5a, d), followed by umbrella sampling to compute the associated free-energy profiles44. In trajectory 0-2-4 (Fig. 2c), although the substrate was primarily transported through the right-side tunnel (Fig. 2c), the pathway was not entirely linear; DHB briefly resided in the left-side branch near the junction (Supplementary Movie 2), a motion that could not be captured by the force-based reaction coordinate in sMD simulations. As a result, the reaction coordinate applied to the yellow-colored pathway did not fully reproduce the actual substrate trajectory. Despite this simplification, the sMD–umbrella sampling approach provided valuable insights into the free-energy landscape.

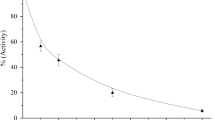

DHB exit pathways through different tunnels in trajectories 0-1-3 (a) and 0-2-4 (d). The green F–F′ loops indicate loop movement in the absence of applied force, and the color gradient from red to blue illustrates the time-dependent positional change of DHB. Free energy profiles for DHB exit from the active site of CYP3A4 via tunnels in trajectory 0-1-3 (b) and 0-2-4 (e). Each panel presents two profiles: the red curve corresponds to simulations with a harmonic restraint applied to the backbone atoms of the F–F′ loop, while the black curve represents simulations conducted without the applied force. c, f Structures at the dashed points in (b, e). Left: Structure with applied force. Right: Structure without applied force. DHB is shown in pink, and the side chains of key residues are depicted in cyan using a licorice representation.

The free energy increase was approximately 15 kcal mol-1 for both exit pathways in the absence of an external force (black traces in Fig. 5b, e). However, when a restraining force was applied to the backbone atoms of the F–F′ loop during the exit process, the free energy increase rose to around 30 kcal mol-1 (red traces in Fig. 5b, e). A comparison of the two free energy profiles in Fig. 5b, e reveals that the primary energy differences appeared after the point marked by the dashed line, with the corresponding structures shown in Fig. 5c, f. When force was applied to the F–F′ loop, several residues, particularly F215 within the loop, impeded the DHB exit pathway (left panels in Fig. 5c, f). In contrast, in the absence of the applied force, the flexible F–F′ loop allowed greater mobility of key residues, thereby reducing steric hindrance and facilitating DHB egress. These findings underscore the critical role of F–F′ loop flexibility in DHB dissociation, as restraining its motion significantly increases the associated free-energy rise.

Simulations reveal downward movement of the F–F′ loop during DHB’s conformational transition toward its crystallographic binding pose

After DHB became trapped within CYP3A4, subsequent MD simulations (trajectories 3–5 and 3–6) revealed that the F–F′ loop began to move downward as DHB underwent a conformational transition toward the binding pose observed in the crystal structure (Supplementary Movies 3 and 4)35. During this transition, aromatic (π–π stacking-like) contacts with phenylalanine residues, together with hydrogen bonding, appeared to play critical roles in stabilizing the conformational rearrangement of DHB. In both trajectories shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8, the RMSD of the F–F′ loop decreased progressively and eventually reached a stable value. Structural comparisons of the F–F′ loop between multiple simulated structures and the crystal structure are presented in Fig. 6d, e, showing that as DHB approached the heme center, the F–F′ loop gradually moved downward. However, due to the limited simulation timescale, we were unable to capture a structure in which the F–F′ loop adopted the fully downward-oriented conformation observed in the crystal structure of the DHB-bound complex (Fig. 6d, e). Further analysis revealed that phenylalanine residues formed π–π stacking-like contacts with the psoralen ring of the DHB molecule, thereby facilitating the conformational transition (Supplementary Fig. 9). Additionally, the DHB tail was stabilized through hydrogen bonding with residue E349 (Supplementary Fig. 10).

a Top: Schematic diagram illustrating the conformational changes of DHB and the F–F′ loop. Bottom: Two distinct pathways leading to stable DHB conformations with the psoralen head oriented toward the heme group, captured by independent, unbiased MD simulations. Time evolution of RMSD values for DHB and the F–F′ loop during MD simulations 3-5 (b) and 3-6 (c). All trajectory frames were aligned to the crystal structure prior to RMSD calculation. d, e Conformational transitions of the F–F′ loop during the simulations. The loops colored red, pink, light blue, and dark blue correspond to states I, II, III, and IV in b (d) or c (e), respectively. The overall enzyme structure is taken from the crystal structure, with the F–F′ loop shown in green. Final DHB structures (cyan) from trajectories 3-5 (f) and 3-6 (g), each aligned to the crystal structure (green)35.

In trajectory 3-5, the DHB molecule underwent continuous conformational adjustments, ultimately adopting the conformation observed in the crystal structure (Fig. 6f)35. Although the final RMSD between the simulated and crystal structures fluctuated around 3 Å, the pose was not highly stable, as indicated by the large standard deviation of the RMSD values. Nevertheless, the MM-PBSA results in Supplementary Table 3 showed that the binding energy between DHB and the enzyme in this final pose was the most favorable among all major poses. In trajectory 3-6, the final pose was more stable, with smaller RMSD variations. However, the DHB conformation differed from that in the crystal structure, primarily due to a rotation and translational displacement of the psoralen moiety (Fig. 6g). Despite this deviation, aromatic (parallel-displaced π–π stacking-like) contacts with the heme group were maintained, consistent with the mechanism proposed by Rossi and coworkers45. Overall, following conformational adjustment, the DHB molecule adopted either the crystallographic binding conformation or an alternative binding mode, both of which preserved aromatic π–π stacking-like interactions with the heme group. Additionally, the F–F′ loop gradually moved downward during the conformational transition.

In summary, our simulations captured, for the first time, the key conformational transition of the F–F′ loop from a downward- to an upward-oriented conformation during two distinct DHB access events. The upward-oriented conformations closely resembled those observed in a CYP3A4 crystal structure complexed with clotrimazole41. The DHB binding process followed a two-step mechanism comprising an initial surface residence phase and a subsequent induced-fit transition. In the first step, the DHB molecule remained associated with the protein surface (at the entrance of tunnel 2a or 2b) for an extended period, after which it triggered a substantial conformational rearrangement of the F–F′ loop. DHB then entered the active site, where it was stabilized by the upward-oriented loop and underwent further conformational adaptation within the expansive binding pocket of CYP3A4. As DHB adjusted its conformation, the F–F′ loop reverted to the downward-oriented state. Notably, one of the simulated DHB binding poses closely reproduced the crystallographic binding mode.

Network of dynamic transitions along the substrate-binding pathway via a Markov state model

For the complete trajectory 0-1-3-5 leading to the crystallographic DHB binding pose, we constructed an MSM to characterize the binding process46. A simple three-macrostate model was sufficient to effectively describe this process (Fig. 7). In State A, the DHB molecule resides on the CYP3A4 surface with the F–F′ loop in the downward-oriented conformation. Most DHB molecules are positioned near the entrance of tunnel 2b, awaiting access to the active site. In States B and C, DHB is bound to CYP3A4. The rate-determining step in the entry/exit process corresponds to the transition between State A and State B. In State B, the F–F′ loop moves upward to capture a DHB molecule. In State C, DHB undergoes conformational adaptation within the active site, and the psoralen moiety becomes oriented toward the heme center, closely resembling the crystallographic binding conformation. The association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants derived from the MSM were 3.0 × 10⁷ M⁻¹ s⁻¹ and 6.1 s⁻¹, respectively. Experimental studies have reported a dissociation constant (Kd) for DHB binding to CYP3A4 of 2.2 × 10⁻⁷ M35, calculated as koff/kon. Our MSM-derived Kd value of 2.0 × 10⁻⁷ M is in excellent agreement with this experimental result. We note, however, that the computationally derived kinetic parameters (kon and koff) may be influenced by the absence of a membrane, whereas the calculated Kd, being a thermodynamic quantity, is expected to be less sensitive to such effects.

The network kinetically connects multiple metastable intermediates (States A–C). All conformations were obtained from the MSM constructed along the trajectory leading to the crystallographic binding pose (trajectory 0-1-3-5). Ten representative snapshots of the F–F′ loops (green) and DHB molecules from each macrostate are shown. The mean first-passage times (MFPTs), indicated by arrows between macrostates, are presented to illustrate the transition kinetics.

Furthermore, a six-macrostate model, shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, is consistent with our previous observations of the DHB binding process. After initially diffusing randomly around the protein surface (State A′), DHB accumulates near the entrance of tunnel 2b (State B′), and subsequently progresses into the active site, accompanied by an upward movement of the F–F′ loop (State C′). Subsequent conformational changes within the active site (States D′ and E′) lead to DHB adopting a final binding pose that closely resembles the conformation observed in the crystal structure, after which the F–F′ loop gradually begins to move downward (State F′).

Second substrate binding via a new tunnel when the active site is already occupied by one substrate

In addition to single-substrate binding, we observed a phenomenon in which two substrates bound sequentially in independent trajectories 3-7 and 4-8 (Supplementary Movies 5 and 6). Notably, the substrates entered the active site one after the other, with representative structures shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. The entry tunnel for the first DHB molecule was the cyan tunnel in trajectory 0-1-3 and the yellow tunnel in trajectory 0-2-4. In contrast, the second DHB molecule entered through tunnel 2a in both trajectories (Fig. 8b, c), with the entry gate located between helices A′ and F′, the same region where DHB remained for an extended period prior to entry in trajectory 0-2-4 (Fig. 3d). It is noteworthy that substrate entry from tunnel 2a has also been reported by Hackett using accelerated MD simulations of CYP3A4 in a membrane environment38. Although the RMSD of the F–F′ loop remained relatively high after the second DHB molecule was stabilized within the active site, structural comparisons revealed a partial downward displacement of the loop upon the second binding event (Fig. 8), resembling the downward movement of the F–F′ loop observed during DHB’s conformational transition in single-substrate binding (Fig. 6). This non-decreasing RMSD behavior may result from additional lateral motion of the F–F′ region relative to the heme plane. In both trajectories, the final conformations of the two DHB molecules remained stable, as evidenced by minimal fluctuations in the Fe–C26 distance and only moderate RMSD changes in the F–F′ loop. The final binding poses observed in the simulations are illustrated in Fig. 8f, g. In summary, two substrates can sequentially enter and stably occupy the active site of CYP3A4, with the F–F′ loop once again moving downward in response to the second substrate binding.

a Top: Schematic representation illustrating the sequential binding of two DHB molecules and the associated conformational change of the F–F′ loop. Bottom: Overview of the MD simulations, with two distinct pathways leading to the dual DHB binding indicated by star symbols. b, c Left: Positional changes of the second DHB molecule (DHB2) as it binds to the active site of CYP3A4 in trajectories 3-7 (b) and 4-8 (c). The first bound DHB molecule is shown in green. Right: Time evolution of the Fe–C26 distance for DHB2 and the RMSD of the F–F′ loop during MD trajectories 3-7 (b) and 4-8 (c). Trajectory frames were aligned to the crystal structure before RMSD calculation. d, e F–F′ loop conformational changes during the simulations. Loops colored red, pink, light blue, and dark blue represent states I, II, III, and IV in b (d) or c (e), respectively. The overall enzyme structure is based on the crystal structure, with the F–F′ loop colored green. Final binding poses of the two DHB molecules in trajectories 3-7 (f) and 4-8 (g). The first DHB molecule is shown in pink, and the second in green. The distances between the heme iron and C26 on DHB are labeled in Å.

Plausible mechanism of DHB binding

Based on the preceding findings, we summarize the DHB binding process in Fig. 9. Initially, the DHB molecule resides on the surface of CYP3A4 while the F–F′ loop remains in a downward-oriented conformation for an extended period. In step (1), DHB binding triggers a conformational rearrangement of the F–F′ loop, with DHB maintaining a similar location but adopting a new orientation. In step (2), the DHB molecule enters the active site and becomes trapped by the F–F′ loop region. In step (3), DHB adjusts its binding pose as it approaches the catalytic center, while the F–F′ loop shifts partially downward. Alternatively, in step (4), DHB adjusts its pose while remaining near the entrance, awaiting the entry of a second DHB molecule. In step (5), the second DHB enters the catalytic site with the F–F′ loop still in an upward-oriented conformation. After step (6) or (6′), the F–F′ loop adopts a partially downward-oriented conformation, and one or two DHB molecules become stabilized within the active site. The conformation of the bound DHB molecule closely resembles that observed in the crystal structure after step (6). Although the fully downward-oriented conformation of the F–F′ loop was not captured in our MD simulations due to limitations in simulation timescale, the crystal structure of the DHB-bound complex clearly shows the loop adopting this conformation. Therefore, we propose that the F–F′ loop continues to move downward as the initially bound DHB molecule adopts the experimentally observed conformation, as shown after steps (7) and (7′). The downward movement of the F–F′ loop may help stabilize the final binding conformation and facilitate catalytic activity.

Discussion

In this study, we performed unbiased MD simulations of DHB binding to CYP3A4, starting from the unbound state and capturing transitions to multiple bound conformations. In one of these states, the binding pose of DHB closely matched the conformation observed in the crystal structure35. Additionally, in several other bound states, two DHB molecules were simultaneously accommodated within the active site, consistent with a previous report identifying two DHB binding sites35. The simulations revealed a two-step binding mechanism, in which DHB initially resided on the surface of CYP3A4 for an extended period (surface residence), followed by a major conformational change involving an upward movement of the F–F′ loop (induced-fit transition). This upward shift facilitated DHB entry into the catalytic pocket while simultaneously preventing premature dissociation. Subsequently, DHB underwent conformational rearrangement within the pocket, adopting two stable poses that form aromatic (π–π stacking-like) contacts with the heme group, while the F–F′ loop gradually began to move downward. In the dual-substrate binding scenario, the F–F′ loop also moved downward after the second DHB molecule entered the active site. Given that the F–F′ loop adopts a fully downward-oriented conformation in the DHB-bound crystal structure, we speculate that further downward displacement of the loop is required to initiate catalysis. The F–F′ loop may act as a gate-like structural element, moving upward to permit substrate entry, and downward to stabilize the substrate near the heme center, thereby facilitating the catalytic reaction. Our multiple long-timescale, unbiased MD simulations provide molecular-level insight into the central role of the F–F′ loop in DHB binding. Moreover, the ability of CYP3A4 to accommodate and oxidize even larger substrates underscores the broader significance of this loop motion, not only for DHB oxidation but also for the metabolism of a wide range of substrates.

Previous studies have emphasized the structural flexibility of P450s during substrate binding. For instance, Ekroos and Sjögren demonstrated significant conformational changes in the F–G region, C-terminal loop, and helix I during crystallographic analysis, while the F–F′ loop remained unresolved due to low electron density29. In our study, the most prominent conformational change is attributed to the movement of the F–F’ loop, which appears to be critical for substrate entry and stabilization. Moreover, the upward-oriented conformation of the F–F′ loop observed in the clotrimazole-bound structure further supports the functional relevance of this motion41.

A Markov state model constructed from trajectory 0-1-3-5, which reproduced the crystallographic DHB binding pose, yielded both the on-rate and off-rate constants. The resulting dissociation constant (Kd = koff/kon = 2.0 × 10⁻⁷ M) closely matches the experimental value (2.2 × 10⁻⁷ M)35. This close agreement suggests that the substrate-binding pathway observed in our simulation may reflect the physiological route of DHB binding, with the rate-determining step corresponding to the transition between State A and State B.

Because P450s, particularly CYP3A4, play a versatile role in xenobiotic metabolism, the mechanisms governing substrate entry and exit have long been a subject of debate. In this work, we identified several DHB-binding pathways using unbiased MD simulations and demonstrated the pivotal role of the F–F′ loop in facilitating DHB binding, offering new mechanistic insights into the substrate recognition process and catalytic function of CYP3A4. This remains an intriguing topic with multiple layers of complexity. Our findings provide a foundation for future large-scale computational studies aimed at deepening our understanding of substrate entry, product egress, and the conformational dynamics of P450s.

Methods

Unbiased MD simulation

Although there are small differences in the orientations of residues on the F–F′ loop (including R212) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 12a) between DHB-bound CYP3A4 and apo CYP3A4, similar variability is also observed among different apo CYP3A4 structures (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Moreover, the loop is inherently flexible, and the minor differences in the initial conformations of the R212 and F215 side chains are expected to have only a negligible effect on the microsecond-scale trajectories. Consistent with this expectation, during our MD simulations, we captured structures in which the rotations of the R212 and F215 side chains corresponded to those seen in the apo structures (Supplementary Fig. 12d). Given the high structural similarity between the DHB-bound and apo CYP3A4 structures, the X-ray crystal structure of DHB-bound human CYP3A4 (PDB ID 6OOB) was used as the starting model for all simulations, after removal of the bound DHB molecule34,35. Microsomal P450s like CYP3A4 are membrane-bound10,47. However, because inclusion of a membrane–protein composite model would result in substantial computational cost, we primarily employed a membrane-free model. The absence of the membrane may introduce artificially increased flexibility into the protein structure, potentially leading to structural collapse during long-timescale force-field-based simulations. Nevertheless, the loop movement event occurred within relatively short timescales (<~11 μs) in our model and was not observed in the absence of substrates (Supplementary Fig. 13). These observations support the interpretation that the loop movement is triggered by substrate binding, rather than prolonged simulation. Missing residues in the crystal structure were modeled using MODELLER39,40. The substrate-free CYP3A4 structure was placed at the center of an octahedral box filled with TIP3P water, ensuring a minimum distance of 10 Å between the protein surface and the box edge48. Na+ and Cl– ions were added to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological salt concentration of 0.15 M. Three DHB molecules were randomly placed in the solvent while avoiding direct contact with the protein. The final simulation system contained 52,249 atoms. The all-atom Amber ff19SB force field was applied to the protein, heme, and ions49. Parameters for the pentacoordinate ferric heme complex were taken from the literature50, and parameters for DHB were derived from the general AMBER force field (GAFF), with RESP charges computed at the B3LYP/6-31 G* level of theory51,52.

All unbiased MD simulations were performed using the CUDA version of Amber 22 with a leapfrog integrator53,54,55. The systems were first equilibrated through energy minimization followed by a mixed NVT/NPT protocol. Production runs were carried out in the NPT ensemble at 310 K using a Langevin thermostat (relaxation time: 2.0 ps) and 1 bar with a Berendsen barostat (relaxation time: 1.0 ps)56,57. The SHAKE algorithm was applied to constrain covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms58, and long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 10.0 Å cutoff59.

Three independent simulations were initiated from the same starting configuration, with random velocities assigned to all particles. After 11 µs of simulation, the F–F′ loop moved upward. To increase the likelihood of capturing the DHB-binding event, four additional simulations were initiated from the final frame of each 11 µs run. In two of these trajectories (0-1-3 and 0-2-4), a single DHB molecule entered the active site of CYP3A4. Subsequently, four independent, unbiased MD simulations were performed based on these two trajectories to capture a DHB binding pose resembling that observed in the crystal structure. Additionally, the binding of two DHB molecules within the same catalytic pocket was observed during two independent extended MD simulations.

To assess the impact of the membrane on substrate binding, we also performed MD simulations with CYP3A4 embedded in a lipid bilayer environment. The N-terminal transmembrane helix of CYP3A4 was added based on the AlphaFold3-predicted structure, and the resulting full-length protein model was incorporated into a lipid membrane60. To enhance the likelihood of observing F–F′ loop movement and DHB binding, five parallel MD simulations were conducted with ten DHB molecules distributed around the protein surface. All other simulation parameters were identical to those used in the membrane-free systems. Owing to computational limitations, we were unable to perform a sufficiently large number of long-timescale simulations with this extended model, and the DHB substrate did not fully enter the active site within the available simulation time. Importantly, however, in one of these simulations, the F–F′ loop shifted upward within 6 µs (Supplementary Fig. 14), yielding a representative structure similar to that observed in the absence of a membrane. Several DHB molecules were stabilized at the entrance of tunnel 2b (Supplementary Fig. 14), consistent with the behavior observed in trajectory 0-1-3 (Fig. 3), suggesting that DHB may also access the active site via tunnel 2b under membrane-bound conditions. All MD trajectories mentioned in the main text and the Supplementary Information are summarized in Supplementary Table 4, and the Supplementary movies with their descriptions are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

sMD and umbrella sampling simulations

To analyze the energy changes associated with DHB molecule exit, with and without restraint of the F–F′ loop, we performed sMD and umbrella sampling simulations42,43,44. Initial configurations were generated by gradually increasing the center-of-mass (COM) distance between the DHB molecule and the heme iron, using a harmonic force constant of 5 kcal mol-1 Å-2 and a pulling rate of 1 Å ns-1. Two exit directions were considered, corresponding to the reverse of the DHB entry pathways observed through the right-hand yellow and cyan tunnels. To restrain the F–F′ loop during DHB exit, a harmonic force of 25 kcal mol-1 Å-2 was applied to the backbone atoms of the F–F′ loop. This setup yielded four sMD trajectories, covering two exit tunnels with or without F–F′ loop restraints. The sMD-generated configurations were subsequently used as starting structures for umbrella sampling44. The COM distance between the iron and the DHB molecule ranged from 7.5 Å to 30.0 Å, with a window spacing of 0.5 Å. Each window was restrained with a harmonic potential using a force constant of 10 kcal mol-1 Å-2 to ensure sufficient overlap between adjacent sampling windows. Each window was simulated for 20 ns to achieve converged sampling. Finally, the potential of mean force (PMF) along the reaction coordinate was computed using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)61,62,63,64.

MSM analysis of the MD Data

To identify the kinetically relevant metastable states and their interconversion rates along the DHB entry pathway, we performed MSM analysis using the PyEMMA package65,66,67,68. The input features included: binary contact matrices between key amino acid residues and DHB, the COM of the bound DHB, the Fe–O6, Fe–C12, and Fe–C26 distances, and the RMSD of the F–F′ loop. Each trajectory frame was encoded as a 16-dimensional feature vector. To reduce dimensionality, we applied time-lagged independent component analysis (tICA)69,70 for dimensionality reduction with a lag time of 60 ns, retaining the top two components. The resulting 2D data were discretized into 600 microstates using k-means clustering71. Bayesian MSMs were constructed with a lag time of 60 ns, following validation of the Markovian property through implied timescales across different lag times (Supplementary Fig. 16)72. Kinetic rate constants (kon and koff) were estimated using the mean first-passage time73 (MFPT) approach, where kon = 1/(MFPTonC) and koff = 1/(MFPToff), with C representing the DHB concentration (8.2 mM). Finally, transition path theory (TPT) was applied to identify dominant transition pathways and quantify their net fluxes74,75.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and Supplementary Information. Due to the large size of the MD trajectories generated in this work, they are available for non-commercial use upon request by contacting J.Y. (220059035@link.cuhk.edu.cn). The crystal structure used in this work (PDB code 6OOB) is available from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). MD simulations were performed using Amber 22 (https://ambermd.org/GetAmber.php), and MSM analyses were carried out using PyEMMA package (http://emma-project.org/latest/). These software tools are available from their respective developers or institutions. Input files for the MD simulations, MSM analyses, and sMD simulations are freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/CatherineYan11/DHB_binding_CYP3A4). The numerical data used for the plots from Figs. 2–8 are provided in Supplementary Data 1; those for the plots from Supplementary Figs. 2–8 in Supplementary Data 2; and those for the plots from Supplementary Figs. 9–14 in the Supplementary Data 3.

References

Buch, I., Giorgino, T. & De Fabritiis, G. Complete reconstruction of an enzyme-inhibitor binding process by molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10184–10189 (2011).

Shan, Y. et al. How does a drug molecule find its target binding site? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9181–9183 (2011).

Ayaz, P. et al. Structural mechanism of a drug-binding process involving a large conformational change of the protein target. Nat. Commun. 14, 1885 (2023).

Follmer, A. H., Mahomed, M., Goodin, D. B. & Poulos, T. L. Substrate-dependent allosteric regulation in cytochrome P450cam (CYP101A1). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16222–16228 (2018).

Ahalawat, N. & Mondal, J. Mapping the substrate recognition pathway in cytochrome P450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 17743–17752 (2018).

Fischer, A. & Smieško, M. Spontaneous ligand access events to membrane-bound cytochrome P450 2D6 sampled at atomic resolution. Sci. Rep. 9, 16411 (2019).

Kingsley, L. J. & Lill, M. A. Substrate tunnels in enzymes: structure-function relationships and computational methodology. Proteins 83, 599–611 (2015).

Su, K. H. et al. Calculation of CYP450 protein-ligand binding and dissociation free energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 025101 (2021).

Fu, T., Zhang, H. & Zheng, Q. Molecular insights into the heterotropic allosteric mechanism in cytochrome P450 3A4-mediated midazolam metabolism. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 5762–5770 (2022).

Berka, K., Paloncýová, M., Anzenbacher, P. & Otyepka, M. Behavior of human cytochromes P450 on lipid membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 117, 11556–11564 (2013).

Spanke, V. A., Egger-Hoerschinger, V. J., Ruzsanyi, V. & Liedl, K. R. From closed to open: three dynamic states of membrane-bound cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 39, s10822-025–00589-1 (2025).

Hruska, E., Abella, J. R., Nüske, F., Kavraki, L. E. & Clementi, C. Quantitative comparison of adaptive sampling methods for protein dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 244119 (2018).

Denisov, I. G., Makris, T. M., Sligar, S. G. & Schlichting, I. Structure and chemistry of cytochrome P450. Chem. Rev. 105, 2253–2277 (2005).

Shaik, S., Hirao, H. & Kumar, D. Reactivity patterns of cytochrome P450 enzymes: Multifunctionality of the active species, and the two states-two oxidants conundrum. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 533–552 (2007).

Hirao, H. et al. Computational studies on human cytochrome P450: advancing insights into drug metabolism. Trends Chem. 7, 358–371 (2025).

Shaik, S. et al. P450 enzymes: their structure, reactivity, and selectivity-modeled by QM/MM calculations. Chem. Rev. 110, 949–1017 (2010).

Shaik, S., Kumar, D., de Visser, S. P., Altun, A. & Thiel, W. Theoretical perspective on the structure and mechanism of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem. Rev. 105, 2279–2328 (2005).

Schlichting, I. et al. The catalytic pathway of cytochrome P450cam at atomic resolution. Science 287, 1615–1622 (2000).

Wade, R. C., Winn, P. J., Schlichting, I. & Sudarko A survey of active site access channels in cytochromes P450. J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 1175–1182 (2004).

Oprea, T. I., Hummer, G. & Garcia, A. E. Identification of a functional water channel in cytochrome P450 enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 2133–2138 (1997).

Hamdane, D. et al. Structure and function of an NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase in an open conformation capable of reducing cytochrome P450. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11374–11384 (2009).

Winn, P. J., Lüdemann, S. K., Gauges, R., Lounnas, V. & Wade, R. C. Comparison of the dynamics of substrate access channels in three cytochrome P450s reveals different opening mechanisms and a novel functional role for a buried arginine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5361–5366 (2002).

Cojocaru, V., Winn, P. J. & Wade, R. C. The ins and outs of cytochrome P450s. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1770, 390–401 (2007).

Urban, P., Lautier, T., Pompon, D. & Truan, G. Ligand access channels in cytochrome P450 enzymes: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1617 (2018).

Don, C. G. & Smieško, M. Out-compute drug side effects: focus on cytochrome P450 2D6 modeling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. 8, e1366 (2018).

Guengerich, F. P., Wilkey, C. J. & Phan, T. T. N. Human cytochrome P450 enzymes bind drugs and other substrates mainly through conformational-selection modes. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 10928–10941 (2019).

Rendic, S. & Guengerich, F. P. Survey of human oxidoreductases and cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic and natural chemicals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 28, 38–42 (2015).

Williams, P. A. et al. Crystal structures of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science 305, 683–386 (2004).

Ekroos, M. & Sjögren, T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13682–13687 (2006).

Sevrioukova, I. F. Interaction of CYP3A4 with caffeine: first insights into multiple substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 105117 (2023).

Skopalík, J., Anzenbacher, P. & Otyepka, M. Flexibility of human cytochromes P450: molecular dynamics reveals differences between CYPs 3A4, 2C9, and 2A6, which correlate with their substrate preferences. J. Phys. Chem. B. 112, 8165–8173 (2008).

Lin, H. L., Kenaan, C. & Hollenberg, P. F. Identification of the residue in human CYP3A4 that is covalently modified by bergamottin and the reactive intermediate that contributes to the grapefruit juice effect. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 40, 998–1006 (2012).

Yan, J. & Hirao, H. QM/MM study of the metabolic oxidation of 6’,7’-dihydroxybergamottin catalyzed by human CYP3A4: preferential formation of the γ-ketoenal product in mechanism-based inactivation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 65, 4620–4629 (2025).

Yano, J. K. et al. The structure of human microsomal cytochrome P450 3A4 determined by X-ray crystallography to 2.05-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38091–38094 (2004).

Sevrioukova, I. F. Structural insights into the interaction of cytochrome P450 3A4 with suicide substrates: mibefradil, azamulin and 6’,7’-dihydroxybergamottin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4245 (2019).

Fishelovitch, D., Shaik, S., Wolfson, H. J. & Nussinov, R. Theoretical characterization of substrate access/exit channels in the human cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme: involvement of phenylalanine residues in the gating mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B. 113, 13018–13025 (2009).

Paloncýová, M., Navrátilová, V., Berka, K., Laio, A. & Otyepka, M. Role of enzyme flexibility in ligand access and egress to active site: bias-exchange Metadynamics study of 1,3,7-trimethyluric acid in cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 2101–2109 (2016).

Hackett, J. C. Membrane-embedded substrate recognition by cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 4037–4046 (2018).

Sali, A. & Blundell, T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 (1993).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Hsu, M. H. & Johnson, E. F. Differential effects of clotrimazole on X-Ray crystal structures of human cytochromes P450 3A5 and 3A4. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 51, 1642–1650 (2023).

Jensen, M., Park, S., Tajkhorshid, E. & Schulten, K. Energetics of glycerol conduction through aquaglyceroporin GlpF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6731–6736 (2002).

Xia, S. & Hirao, H. The dissociation process of NADP(+) from NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase studied by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 128, 7148–7159 (2024).

Torrie, G. M. & Valleau, J. P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 187–199 (1977).

Rossi, M. et al. The grapefruit effect: interaction between cytochrome P450 and coumarin food components, bergamottin, fraxidin and osthole. X-ray crystal structure and DFT studies. Molecules 25, 3158 (2020).

Chodera, J. D. & Noé, F. Markov state models of biomolecular conformational dynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 25, 135–144 (2014).

Baylon, J. L., Lenov, I. L., Sligar, S. G. & Tajkhorshid, E. Characterizing the membrane-bound state of cytochrome P450 3A4: structure, depth of insertion, and orientation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 8542–8551 (2013).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Tian, C. et al. ff19SB: amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 528–552 (2020).

Shahrokh, K., Orendt, A., Yost, G. S. & Cheatham III, T. E. Quantum mechanically derived AMBER-compatible heme parameters for various states of the cytochrome P450 catalytic cycle. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 119–133 (2012).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

He, X., Man, V. H., Yang, W., Lee, T.-S. & Wang, J. A fast and high-quality charge model for the next generation general AMBER force field. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 114502 (2020).

Salomon-Ferrer, R. et al. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. explicit solvent particle mesh ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 3878–3888 (2013).

Le Grand, S., Götz, A. W. & Walker, R. C. SPFP: speed without compromise-a mixed precision model for GPU accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 374–380 (2013).

Case, D. A. et al. Amber 2022 (University of California, 2022).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Izaguirre, J. A., Catarello, D. P., Wozniak, J. M. & Skeel, R. D. Langevin stabilization of molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 114, 2090–2098 (2001).

Ryckaert, J.-P., Ciccotti, G. & Berendsen, H. J. C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 (1977).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Kumar, S., Rosenberg, J. M., Bouzida, D., Swendsen, R. H. & Kollman, P. A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Chem. Phys. 13, 1011–1021 (1992).

Kumar, S., Rosenberg, J. M., Bouzida, D., Swendsen, R. H. & Kollman, P. A. Multidimensional free-energy calculations using the weighted histogram analysis method. J. Comput. Phys. 16, 1339–1350 (1995).

Roux, B. The calculation of the potential of mean force using computer simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 275–282 (1995).

Souaille, M. & Roux, B. T. Extension to the weighted histogram analysis method: combining umbrella sampling with free energy calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 135, 40–57 (2001).

Scherer, M. K. et al. PyEMMA 2: a software package for estimation, validation, and analysis of Markov Models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 5525–5542 (2015).

Plattner, N. & Noé, F. Protein conformational plasticity and complex ligand-binding kinetics explored by atomistic simulations and Markov models. Nat. Commun. 6, 7653 (2015).

Zhuang, Y., Howard, R. J. & Lindahl, E. Symmetry-adapted Markov state models of closing, opening, and desensitizing in α 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Commun. 15, 9022 (2024).

Pande, V. S., Beauchamp, K. & Bowman, G. R. Everything you wanted to know about Markov State Models but were afraid to ask. Methods 52, 99–105 (2010).

Molgedey, L. & Schuster, H. G. Separation of a mixture of independent signals using time delayed correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3634–3637 (1994).

Schwantes, C. R. & Pande, V. S. Improvements in Markov State Model construction reveal many non-native interactions in the folding of NTL9. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 2000–2009 (2013).

Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 28, 129–137 (1982).

Noé, F., Wu, H., Prinz, J. H. & Plattner, N. Projected and hidden Markov models for calculating kinetics and metastable states of complex molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 184114 (2013).

Da, L. T., Sheong, F. K., Silva, D. A. & Huang, X. Application of Markov State Models to simulate long timescale dynamics of biological macromolecules. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 805, 29–66 (2014).

Yu, T.-Q., Lapelosa, M., Vanden-Eijnden, E. & Abrams, C. F. Full kinetics of CO entry, internal diffusion, and exit in myoglobin from transition-path theory simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3041–3050 (2015).

Metzner, P., Schütte, C. & Vanden-Eijnden, E. Transition path theory for Markov jump processes. Multiscale Model Sim 7, 1192–1219 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ganghong Young Scholar Development Fund, the Shenzhen Natural Science Foundation (2022), and funding to the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology from Shenzhen City and Longgang District (C10120180043, LGKCSDPT2024001). The authors thank Jianyu Yang and Songyan Xia for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. designed research, performed research, and analyzed data. H.H. conceived and supervised the project. J.Y. and H.H. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Kshatresh Dubey, Canan Atilgan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, J., Hirao, H. Molecular dynamics simulations elucidate the role of the F–F′ loop in substrate entry into CYP3A4. Commun Chem 9, 17 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01815-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01815-5