Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is marked by the abnormal aggregation of amyloid-beta peptides within the central nervous system. The formation of amyloid fibrils from amyloid-beta peptides is a hallmark of AD Here, we demonstrate that the aggregation of amyloid-beta 42 spreads both spatially and temporally. By measuring the spatial propagation of amyloid-beta in macroscopic capillaries and performing Monte Carlo simulations, we show that this spreading occurs through a diffusion mechanism involving oligomers in solution. These species, catalytically produced through spontaneous secondary nucleation, significantly accelerate the propagation velocity of the reaction wavefront. Our findings suggest that, in addition to their potential role in toxicity, these oligomers in solution are key drivers of the spatial spreading of aggregation and can therefore be considered key targets for therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The proliferation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) aggregates is a characteristic feature of the onset and development of Alzheimer’s disease1,2. Observations of protein aggregation in living systems suggest that Aβ, along with other amyloidogenic proteins such as α-synuclein and tau, can undergo a process of amyloid formation which progresses from one location to another in space3,4,5,6,7,8. This type of qualitative behaviour has also been identified for the prion diseases9,10,11,12. Both the morphology and molecular structure of Aβ aggregates have been shown to self-replicate when they grow from preformed seeds4. As such, aggregates have the ability to impose their misfolded state on native Aβ monomers through this type of seeding process. The uncontrolled cascade of misfolding and aggregation can ultimately overwhelm cellular clearance mechanisms and perturb the function of neuronal cells in the central nervous system, driving the disease symptoms7.

There has been significant progress in our understanding of the fundamental molecular steps involved in protein aggregation. Bulk experiments reveal several distinct molecular processes driving the overall protein aggregation process. Specifically, primary nucleation leads to the formation of aggregates from the spontaneous assembly of several monomers13. Once formed, these aggregates can elongate by binding monomers at fibril ends, thereby increasing in size. Crucially, many of the disease-implicated amyloid aggregates further possess a distinct propensity towards spontaneous secondary nucleation. In this process, additional nuclei are formed on the surfaces of existing aggregates14,15,16,17. Prior studies have largely focused on the temporal evolution of protein aggregates18,19,20,21. However, the spatial propagation of aggregation is crucial for probing intermediate species and distinguishing the underlying microscopic driving forces. In this paper, we investigate the spatial propagation of amyloid-beta 1-42 (Aβ42) aggregation, a key factor in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. We observe spreading on a mesoscopic scale, ensuring that our understanding of Aβ42 aggregate proliferation aligns with the length scales of the brain’s extracellular environment. This study provides insights into the microscopic processes underlying disease progression. Through capillary experiments, we confirm that Aβ42 aggregation is driven by secondary nucleation and demonstrate that oligomer diffusion is the dominant factor in its spatial spreading.

Results

To monitor the spatial propagation of Aβ42 aggregation, an epifluorescence microscopy setup using laser excitation at 445 nm is employed, as shown in Fig. 1. The benzothiazole salt thioflavin-T (ThT) binds to the aggregates and is used as a latent dye. Monomeric protein at six different concentrations (10 μM, 15 μM, 20 μM, 26 μM, 40 μM, and 55 μM) is loaded into square borosilicate capillaries, which are wax-sealed (Fig. 1A). Similarly, four concentrations of half-converted seeds (0.3 μM, 3 μM, 6 μM, and 12 μM) are added to a 20 μM Aβ42 capillary. Before each experiment, samples are prepared through a size exclusion chromatography (SEC) step to ensure that the solution consisted solely of monomeric proteins, without any pre-formed aggregates (see Materials and Methods). The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1. Borosilicate capillaries (5 cm in length) are filled with monomeric Aβ42 solution via capillary action (Fig. 1A). A seed solution can optionally be added to one end before both ends are sealed with wax. Although the wax interface may promote primary nucleation at the capillary ends, the rate of this process is much lower than that of spontaneous secondary nucleation and spontaneous elongation, so its impact on subsequent protein aggregation and spatial propagation is minimal. Each concentration was tested in five independent replicates in five capillaries. The fluorescent intensity of up to 20 capillaries is recorded in parallel by scanning using an automated stage at fixed time intervals (Fig. 1C). Capillaries are placed horizontally to reduce the effect of gravity on propagation along the capillary and on the sedimentation of large aggregates. Image processing is used to extract a 2D map of the fluorescence position over time, from which the front velocity and secondary nucleation rate can be determined (Fig. 1D–F).

A 5 cm borosilicate capillaries are filled with a monomeric Aβ42 solution by capillary forces. A seed solution is optionally added to one side before sealing both ends with wax. B The capillaries are mounted on a fluorescent microscope with excitation at 445 nm. Capillaries are placed horizontally to reduce the effect of gravity. C A motorized stage scans the capillaries, capturing a series of images at each position over several hours. Twenty capillaries were recorded in parallel. Each concentration was tested in five independent replicates, with each replicate measured in five capillaries and marked with the same color, resulting in five propagation images under the same experimental conditions. D In each scanned capillary image, a small part of the capillary is visible. The location of the capillary is detected using image analysis techniques for image reconstruction. E An overall image of the capillary is reconstructed at each time point. F The image stack (D) is then merged to form a 2D image of the fluorescence position over time. This image is used to detect the front position, secondary nucleation rate, and the front velocity.

In total, we recorded more than 80 capillaries, with a selection of these runs shown in Fig. 2. Two key parameters were extracted from the fronts: the front velocity v, calculated by tracking the time at which the fluorescence signal reaches half its maximum at each position along the capillary. And the secondary nucleation rate κ, obtained as the inverse of the front aggregation time. \(\kappa =\sqrt{2{k}_{+}{k}_{2}{m}^{{n}_{2}+1}}\), where k+ is the elongation rate, k2 is the secondary nucleation rate, n2 is the reaction order of secondary nucleation, and m is the monomer concentration22.

A, B 20 μM amyloid beta monomer aggregation. Due to the Fisher wave speed selection, the velocities can vary significantly. Interestingly, a gap appears at low velocities where aggregation stops. In (B), a buffer solution is added to the top of the capillary, which explains the dark gap. C 20 μM amyloid beta monomer with the first 5 mm filled with 12 μM half-converted seeds. The seeds cause aggregation to start immediately by surpassing primary nucleation but do not noticeably change the aggregation speed. D Aggregation front propagation image for 26 μM monomer, and (E) for 40 μM monomer. In these cases, the front starts from one side, and a gap is present at the other side. F Monte Carlo simulation of a propagating front assuming a constant adhesion rate of monomers on the walls, kadhesion = 1.85 ⋅ 10−5s−1. The gap behavior is reproduced. In A–F, warmer colors indicate high protein concentration, while cooler colors indicate low protein concentration. Red lines mark the protein propagation fronts.

Several features can be observed in these capillaries. First, aggregation usually starts at the ends of the capillaries because the ends are sealed with wax, highlighting the importance of interfaces in primary nucleation. The first side to aggregate is typically the lower side in Fig. 1A, which corresponds to the top side in Fig. 2. Although the wax interface can promote primary nucleation, its effect on subsequent protein aggregation and spatial propagation is minimal, as the primary nucleation rate is much smaller than the secondary nucleation and elongation rates. Second, the velocity changes dramatically between repeats, as shown in Fig. 2A, B for 20 μM Aβ42. This variability is an expected feature of Fisher waves, as the velocity depends on initial conditions and can differ significantly between repeats23. Although front velocities vary significantly, a minimal front velocity \({v}_{\min }\) can be predicted theoretically, providing a lower bound for the front velocity. The detailed derivation of the minimum velocity is outlined in the Supplementary Information section: Minimum velocity of Fisher wave. Third, the aggregation time in the capillaries is much longer than expected from bulk experiments. Using the rates determined from aggregation in PEGylated plates, the aggregation time for a 20 μM monomer solution concentration is approximately 20 h (Fig. 2A, B), which is about 250 times longer than in PEGylated plates, corresponding to an effective monomer concentration of roughly 0.5 μM (see Supplementary Information section: Aggregation time). This discrepancy can be explained by monomers adhering to the surface over time, decreasing the effective monomer concentration and aggregation rate. We simulated a propagating front assuming a constant monomer adhesion rate on the capillary walls (Fig. 2F), which reproduces a similar aggregation timescale as observed in the capillary experiments. Finally, the aggregation run doesn’t always fill the entire capillary, forming a gap as indicated in Fig. 1F and in Fig. 2B–E. This gap could be explained by monomer depletion: monomers diffuse into the front and are trapped in it. However, the gap size resulting from this phenomenon depends on the monomer diffusion coefficient and the front velocity, and the predicted width is much smaller than the observed gap size (see Supplementary information section: Gap size). A more likely explanation is that monomers are adhering to the surface, decreasing the effective monomer concentration, which also explains why the aggregation rate decreases over time, when one would expect it to remain constant. Figure 2F shows the result of a Monte Carlo simulation assuming a constant adhesion rate of monomers on the walls, kadhesion = 1.85 ⋅ 10−5s−1, where the gap size and decreasing aggregation rate are reproduced by assuming a fixed adhesion rate.

Two mechanisms are known to drive the spatial propagation of aggregation: either diffusion is restricted and propagation is dominated by fibril growth, or intermediate oligomeric species and mature fibrils diffuse freely and promote aggregation further along the capillary. If spatial propagation is driven by fibril growth, the velocity is given by vgrowth = 2k+mδ/π23, where the elongation rate k+ can be measured by AFM. δ = 1Å represents the length of a monomer. The local monomer concentration m can not be directly measured but can be estimated from the secondary nucleation rate κ measured by the bulk kinetics. Bulk measurements of Aβ42 aggregation kinetics in PEGylated plates provide the relationship \(\kappa =\sqrt{2{k}_{+}{k}_{2}{m}^{{n}_{2}+1}}=\sqrt{2}\cdot {k}_{agg}\cdot {m}^{3/2}\), which leads to \(m={(\kappa /\sqrt{2}{k}_{agg})}^{2/3}\) when n2 = 2 and \({k}_{agg}=\sqrt{{k}_{+}{k}_{2}}\). The propagation velocity through growth is: \({v}_{growth}=2{k}_{+}\delta {(\kappa /\sqrt{2}{k}_{agg})}^{2/3}/\pi\). If the spatial propagation is instead driven by diffusion, the time evolution of fibril mass concentration M(t, x) is described by ref. 23:

where \(\overline{D}\) represents the effective diffusion coefficient. The effective diffusion coefficient \(\overline{D}\) represents an average measure of fibril mobility under a mean-field approximation, depending only on the average fibril size and the effective medium viscosity23. To determine the secondary nucleation rate κ from the fluorescence curves, the slope at the half-aggregation time is used, assuming ∇2M(t, x) ≈ 0. This equation describes a Fisher wave, where the velocity depends on the initial conditions. The minimum velocity is derived as: \({v}_{\min }=2\sqrt{\overline{D}\cdot \kappa }\) (see the Supplementary information section: Minimum velocity of Fisher wave for the derivation of the minimum velocity).

In order to identify which component dominates the reaction-diffusion process of the spatial propagation of Aβ42, the measured velocities of the front, v, are plotted against the measured secondary nucleation rates, κ, for all monomer and seed concentrations in Fig. 3. The green line represents the velocity of propagation through growth: vgrowth. The parameters we substitute are k+ = 3 ⋅ 106 M−1s−1, δ = 1Å and kagg = 2.8 ⋅ 105 M−3/2s−1 at 37 °C for Aβ4217,23,24, which gives \({v}_{growth}=5.43\cdot 1{0}^{-4}{\kappa }^{\frac{2}{3}}\, mm\cdot {h}^{-1}\). It is evident that the velocity predicted by growth-limited propagation is three orders of magnitude lower than the measured velocity of the front v, suggesting that the reaction-diffusion process cannot be dominated by growth. Apart from growth, spatial propagation can be driven by the diffusion of fibrils or intermediate oligomers. The minimum velocity of fibril propagation through fibril diffusion, modeled as a Fisher wave, \({v}_{\min }^{{{\mathrm{fi}}}bril}=0.44{\kappa }^{\frac{2}{3}}mm\cdot {h}^{-1}\), is plotted as the magenta line in Fig. 3 (see Supplementary information section: Theory of protein aggregation kinetics and propagation). The magenta line represents an ideal lower bound of the measured velocity at various monomer concentrations and secondary nucleation rates. The black line shows the fitted propagation result through oligomer diffusion, modeled as a Fisher wave: \({v}_{\min }^{oligomer}=2\sqrt{{D}_{{{\mathrm{fi}}}t}^{oligomer}\cdot \kappa }\). For all seeded and unseeded measurements, the fitted oligomer diffusion coefficient is \({D}_{{{\mathrm{fi}}}t}^{oligomer}=0.664m{m}^{2}\cdot {h}^{-1}\), which is slightly smaller than the monomer diffusion coefficient Dmonomer = 0.97mm2 ⋅ h−1. This indicates that oligomer diffusion dominates the spatial propagation of the aggregation process. We further compare the timescales of oligomer conversion and diffusion to verify that diffusion occurs more rapidly than conversion, ensuring that oligomers remain unconverted during the diffusion process. The rate of oligomer conversion to fibrils is kconv = 3.3 ⋅ 10−2h−124,25. The corresponding conversion time scale is 30 hours, which is relatively longer than the spatial propagation time. This also suggests that spatial propagation is primarily driven by oligomer diffusion, as it occurs faster than the conversion of oligomers into fibrils.

The velocity of the front is plotted against the secondary nucleation rate κ for unseeded and seeded capillaries. Both front velocity and κ are measured from the front propagation. The green line represents the growth-limited velocity vgrowth, which is three orders of magnitude lower than the observed value. The magenta line denotes the minimum velocity \({v}_{\min }^{{{\mathrm{fi}}}bril}\) predicted by fibril diffusion as a Fisher wave. The black line represents a fit to all data points using the function for the oligomer diffusion minimum velocity \({v}_{\min }^{oligomer}=2\sqrt{{D}_{{{\mathrm{fi}}}t}^{oligomer}\kappa }\). Each concentration of monomer and seeds was tested in five independent replicates in five capillaries.

To further demonstrate that oligomer diffusion dominates the spatial propagation of the aggregation process, we performed Monte Carlo simulations of Aβ42 aggregation and propagation. In this particle-based model, Aβ42 is represented as monomers, oligomers modeled as particles containing a constant number of monomers (n = 2), and fibrils, which undergo processes such as diffusion, elongation, secondary nucleation, oligomer conversion, and oligomer dissociation. Primary nucleation is not included; instead, the simulations are initialized with predefined fibril seeds. This framework allows us to follow the spatial and temporal evolution of fibril populations under different experimental conditions. The aggregation kinetic model that takes the intermediate oligomeric state into consideration is described in previous studies24. The simulation results for three scenarios are displayed as heatmaps in Fig. 4. Above each heatmap is the corresponding reaction scheme. An adhesion rate, kadhesion = 1.85 ⋅ 10−5s−1, has been included to describe how monomers adhere to the capillary surface over time and monomers can diffuse freely for all scenarios. In Fig. 4A and B, both oligomers and fibrils can diffuse freely. Their diffusion coefficients depend on their respective hydrodynamic radius Rh: D = kBT/6πηRh, where η is the dynamic viscosity. Figure 4A shows the spatial propagation of fibril mass, while Fig. 4B shows the spatial propagation of oligomers mass. We can clearly observe that oligomer diffusion drives the propagation front, which indicates that oligomer diffusion dominates the protein spatial propagation. In Fig. 4C, oligomers can diffuse freely, but fibril diffusion is halted by setting fibril hydrodynamic radius Rh = ∞ and the corresponding diffusion coefficient is D = 0. The simulation result is similar to that in Fig. 4A, which also proves that oligomer diffusion is the dominat mechanism in protein propagation. In Fig. 4D, fibrils can diffuse freely, but oligomer diffusion is halted. The diffusion of fibrils is much slower than that of oligomers. In summary, the Monte Carlo simulations of spatial aggregation propagation show that oligomer diffusion dominates the spatial propagation of the aggregation process.

Monomers diffuse in all panels with the adhesion rate kadhesion = 1.85 ⋅ 10−5s−1. In (A, B), both oligomers and fibrils diffuse freely. In (C), only oligomers can diffuse while the fibril diffusion has been halted, and in (D), only fibrils diffuse while the oligomer diffusion has been halted. (A, C, D) show the spatial propagation of fibril mass concentration, while (B) shows the spatial propagation of oligomer number concentration.

Discussion

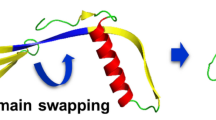

The presence of Aβ aggregates in the brain is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding how these toxic aggregates form and spread, both temporally and spatially in human brain, is crucial. The spatial propagation of Aβ aggregates in vitro has largely been overlooked in the past. Here, by developing an experimental platform using capillaries under fluorescence microscopy, we are able to monitor the spatial spreading of aggregates on a macroscopic length scale, in addition to tracking the temporal evolution of the species. Our findings, based on capillary front measurements and Monte Carlo simulations indicate that oligomer diffusion represents the dominant microscopic process governing the spreading of aggregate species. The detailed schematic illustration of the propagation mechanism is shown in Fig. 5. Oligomer diffusion velocity is 103 times faster than fibril growth velocity. The 50mm capillaries and the oligomer diffusion coefficient (0.664 mm2 ⋅ h−1) with a propagation velocity of 1 mm ⋅ h−1 indicate that oligomers require about 50h to traverse the capillary, suggesting that capillary size does not significantly affect the observed behavior. As detailed previously for Aβ42, insulin and certain other amyloidogenic proteins14,15,16, filaments catalyze the production of additional oligomers on their surfaces. Oligomeric species of Aβ42 were characterized and modeled within an aggregation kinetic framework to elucidate their dynamic roles during amyloid fibril formation24,26. We propose that the diffusion of oligomers promotes the proliferation of aggregate species, further driving the aggregation of Aβ42. Our work emphasizes the significance of this mechanism in the proliferation of aggregate species. Secondary nucleation generates many small oligomers, which can diffuse more quickly than mature fibrils due to their smaller size, thereby enhancing spatial propagation through diffusion. In this way, low-molecular-weight species may be crucial for controlling spreading behavior and prion-like phenomena in the aggregation of Aβ42 and other amyloidogenic proteins. Our results indicate that targeting oligomer spreading could be a key approach for developing therapies against neurodegenerative diseases. Our experiments were conducted in vitro under carefully controlled conditions. In vivo, additional factors such as hydrodynamic effects from interstitial fluid flow and molecular crowding can further modulate the spreading velocity. The approach we have developed may prove useful for investigating amyloid propagation under laboratory conditions and for discovering modulators of this process. This approach offers an effective way to examine the impact of various potential drug molecules on both the temporal and, crucially, spatial development of Aβ42 aggregation. This approach therefore opens up the path to investigating approaches that can help to reduce the spatial propagation of Aβ42 aggregation.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant Aβ42

Aβ42 recombinant protein was expressed and purified according to a previously described protocol27. Briefly, lyophilised Aβ42 was fully dissolved in guanadinium chloride (1 mL) on ice to give a 6 mM solution, pH 8. The Aβ42 solution (1 mL) was injected onto a column (GE Healthcare SuperdexTM 75, 10/300 GL Sweden, 25 mL). The buffer was exchanged with a pre-prepared de-gased phosphate buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4 / NaH2PO4, 0.2 mM EDTA, pH 8) under column flow 0.7 mL.min−1, pressure 0.7 MPa. The obtained stock solution of Aβ42 was stored on ice temporarily during the preparation of capillaries. Monomeric peptide was isolated using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to remove pre-formed aggregates, as described previously22,27,28.

Preparation of capillaries containing unseeded Aβ42

Monomeric Aβ42 solutions at 5 different concentrations (10 μM, 15 μM, 20 μM, 26 μM and 40 μM) were prepared by diluting into the pre-prepared phosphate buffer with ThT (20 μM) in a low-bind Eppendorf. This solution was gently mixed by slow aspiration of a pipette. Each square borosilicate capillary (0.2 mm ID, ≈ 50 mm length, CM Scientific) was filled by capillary action and sealed with wax plugs to prevent evaporation; first at the raised end and then at the lower end, taking care to minimize the air trapped inside. Each experiment consisted of multiple repeats for each concentration of protein. The capillaries were aligned on a glass slide and held in place with epoxy glue at the ends of the capillaries. The time between removing the samples from ice to starting the measurement was typically 30 min. (Capillaries of the lowest concentrations were always prepared first as these were expected to aggregate more slowly and so least affected by the delay due to preparation time).

Preparation of capillaries containing seeded Aβ42

A small aliquot of monomeric Aβ42 solution was diluted to a final concentration of 20 μM in pre-prepared phosphate buffer with ThT (20 μM) and incubated at 37 oC in a microplate (Corning 96 Well Half Area) in a plate reader (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG) until the aggregation curve reached a plateau. Dilutions of these fully-converted monomer seeds were prepared and stored on ice. The time to half-completion (half-time) of the aggregation was identified and seeds, termed half-converted monomer seeds, were produced by repeating the aggregation in the microplate until this time-point and storing the appropriate dilutions on ice. For both types of seeded experiment the capillaries were prepared by aspirating monomeric Aβ42 via capillary action to fill approximately 75% of the capillary. The remaining 25% was then filled in the same manner with seeds and the capillary sealed with wax, at the end with seeds and then at the other end. The capillary preparation was always started from the lowest seed concentrations. As for unseeded experiments, the time between removing the samples from ice to starting the measurement was typically 30 min.

Epifluorescence instrument used in conjunction with an automated stage

An epifluorescence instrument was used for all experiments with an incorporated automated stage (MS-2000 FT, ASI). In brief, a 445 nm laser (MLD, Cobolt) beam, was attenuated with neutral density filters, expanded and collimated. This beam was passed through an excitation filter (FF01-488/20-25, Laser2000) to remove any stray wavelength of light, then directed to the back aperture of the microscope (RAMM, ASI), aligned parallel to the optical axis. A lens was inserted to collimate the beam, reflected by the dichroic mirror (FF484-FDi01-25 × 36, Laser2000), on the sample through the objective (4X, 0.13 NA, Nikon). Emission was collected through the same objective and passed through the same dichroic mirror and a long-pass filter (BLP01-473R-25, Laser2000) before being directed to a camera (CoolSnap MYO, Photometrics).

Programming automated stage for capillary experiments

The automated stage was programmed (Micromanager) to scan the length of the capillaries which were aligned vertically on a glass slide in a meticulous manner such that they were perfectly parallel to the stage movement over the 5 cm distance scanned. This allowed 5 capillaries aligned adjacent to one another with minimal spacing to fit into one field of view (horizontally). Once the first set of 5 capillaries had been scanned the stage was programmed to repeat equivalent scans starting from the top of the next set of 5 capillaries. This process was replicated until all capillaries for the experiment had been scanned (29 positions per capillary length). Using this method a set of brightfield images were taken for each position to confirm that every single capillary remained in view throughout. The brightfield LED was then blocked and fluorescence images taken using a 445 nm laser with a shutter. The whole scanning process was set to repeat every 5 minutes in order to track the position of the ThT dye-active species (Aβ42 aggregates) arising.

Data analysis

The data is analyzed as described in Fig. 1: In each image, the location of each capillary is detected. The images are combined together by knowing the pixel size and the automatic stage step size. The image of each capillary is then separated and an average is taken along the width. Each time point is then used as a column in a 2D map representing the space-time evolution of the propagation front. For each pixel line, the position and slope at the half aggregation point is extracted. The half aggregation point is used because ∇2M ≈ 0 in Equation (S4). The slope can be converted in an aggregation rate as described in Equation (S1) and the velocity is extracted by comparing the half time between neighboring points.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All numerical source data underlying the figures in this study, as well as the corresponding analysis code, have been deposited as Supplementary Data accompanying this manuscript.

References

Hardy, J. & Selkoe, D. J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. (N.Y.) 297, 353–6 (2002).

Mucke, L. & Selkoe, D. J. Neurotoxicity of amyloid β-protein: Synaptic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, 1–17 (2012).

Jarrett, J. T., Berger, E. P. & Lansbury, P. T. The Carboxy Terminus of the β Amyloid Protein Is Critical for the Seeding of Amyloid Formation: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. J. 32, 4693–4697 (1993).

Petkova, A. T., Leapman, R. D. & Guo, Z. Self-Propagating, Molecular-Level Polymorphism in Alzheimer’s beta-Amyloid Fibrils. Science 307, 262–266 (2005).

Westermark, G. T. & Westermark, P. Prion-like aggregates: Infectious agents in human disease. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 501–507 (2010).

Toyama, B. H. & Weissman, J. S. Amyloid Structure: Conformational Diversity and Consequences. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 557–585 (2011).

Jucker, M. & Walker, L. C. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 501, 45–51 (2013).

Guo, J. L. & Lee, V. M. Y. Cell-to-cell transmission of pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Med. 20, 130–138 (2014).

Prusiner, S. B. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 13363–13383 (1998).

Collinge, J. P RION D ISEASES OF H UMANS AND A NIMALS : Their Causes and Molecular Basis. Annu. Rev. 24, 519–50 (2001).

Aguzzi, A. & Calella, A. M. Prions: Protein Aggregation and Infectious Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 89, 1105–1152 (2009).

Aguzzi, A. & Falsig, J. Prion propagation, toxicity and degradation. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 936–939 (2012).

Jarrett, J. T. & Lansburry, P. T. Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie?. Cell 73, 1055–1058 (1993).

Knowles, T. P. J. et al. An analytical solution to the kinetics of breakable filament assembly. Science. (N.Y.) 326, 1533–7 (2009).

Knowles, T. P. J. et al. Observation of spatial propagation of amyloid assembly from single nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14746–14751 (2011).

Cohen, S. I. A. et al. Proliferation of amyloid-β42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9758–63 (2013).

Cohen, S. I. et al. Distinct thermodynamic signatures of oligomer generation in the aggregation of the amyloid-β peptide. Nat. Chem. 10, 523–531 (2018).

Nielsen, L. et al. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: Elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry 40, 6036–6046 (2001).

Grey, M. et al. Acceleration of α-synuclein aggregation by exosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 2969–2982 (2015).

Lindberg, D. J., Wranne, M. S., Gilbert Gatty, M., Westerlund, F. & Esbjörner, E. K. Steady-state and time-resolved Thioflavin-T fluorescence can report on morphological differences in amyloid fibrils formed by Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 418–423 (2015).

Meisl, G. et al. Molecular mechanisms of protein aggregation from global fitting of kinetic models. Nat. Protoc. 11, 252–272 (2016).

Cohen, S. I. A. et al. Nucleated polymerization with secondary pathways. I. Time evolution of the principal moments. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 065105 (2011).

Cohen, S. I. A. et al. Spatial Propagation of Protein Polymerization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 098101 (2014).

Michaels, T. C. et al. Dynamics of oligomer populations formed during the aggregation of alzheimer’s aβ42 peptide. Nat. Chem. 12, 445–451 (2020).

Dear, A. J. et al. Kinetic diversity of amyloid oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 12087–12094 (2020).

Wei, J., Meisl, G., Dear, A. J., Michaels, T. C. & Knowles, T. P. Kinetics of amyloid oligomer formation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 54, 185–207 (2025).

Walsh, D. M. et al. A facile method for expression and purification of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid β-peptide. FEBS J. 276, 1266–1281 (2009).

Fisher, R. A. The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Ann. Eugen. 7, 355 (1937).

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme through the ERC grant DiProPhys (agreement ID 101001615); the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the ETN grant NANOTRANS (grant agreement No. 674979, Q.P.); and the Nidus studentship scheme (J.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.P., C.T., U.L., and T.P.J.K conceived the project. Q.P., C.T., P.A. and U.L. designed and performed experiments. Q.P., J.W., T.C. and T.M. developed the theory, performed the simulation, and analyzed the data. P.A., S.L., and T.P.J.K. provided supervision. Q.P., C.T., U.L., J.W., and T.P.J.K wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the data, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Phuong H. Nguyen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peter, Q., Taylor, C., Lapinska, U. et al. Oligomers mediate the spatial transmission of Aβ peptide aggregation. Commun Chem 9, 35 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01837-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01837-z