Abstract

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is among the most widely used techniques for structure determination, yet automated workflows remain underdeveloped compared to mass spectrometry. In this work, we introduce NMR molecular networking and apply it to Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) spectra, a key 2D-NMR experiment for structure elucidation. We adapt core principles of MS² networking such as transitivity across multiple spectra, dereplication, and annotation propagation to NMR-driven workflows. First, we develop a modified Hungarian distance metric for HSQC peak matching. Benchmarks show that using this metric, traditional spectral lookup with this score recovers ~70-80% of available structural similarity, but efficiency does not improve when increasing the size of the spectral library. Second, we establish NMR molecular networking using HSQC spectra to propagate annotations and dereplicate compounds. Case studies of experimental natural product spectra demonstrate that annotation transitivity within networks accelerates and improves identification of unknowns. Third, we introduce algorithmic molecular networking, which integrates graph topology metrics to correct inefficient rankings and reduce false positives. Together, these approaches define the first generalizable framework for NMR molecular networking, enabling scalable, high-throughput annotation for natural product discovery and drug development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a versatile analytical technique used for unraveling molecular structures and dynamics1,2. Among its diverse array of experiments, Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) spectroscopy is a key measurement used for structural elucidation3. HSQC is a two-dimensional NMR technique that correlates the chemical shifts of hydrogen (1H) nuclei with those of directly bonded heteronuclei like carbon (typically 13C), offering a valuable balance between information density and acquisition time4,5. In ¹H-¹³C HSQC, only protonated carbons (CH, CH₂, CH₃) are observed, which makes the technique valuable for detecting and characterizing molecular scaffolds. Nonetheless, HSQC has limitations: its low sensitivity, the inability to detect nonprotonated carbons, dependence on acquisition parameters, and susceptibility to solvent conditions hinder direct spectral comparisons and limit the ability to distinguish isomeric species6. Interpreting HSQC spectra typically requires significant chemical expertise and domain knowledge. One major bottleneck is the lack of large, high-quality annotated experimental HSQC datasets necessary for automatic interpretation via machine learning (ML) models. The NMRShiftDB7, the largest open-source database for NMR shifts, covers fewer than 100 experimental HSQC spectra.

Unlike the field of mass spectrometry, which has benefited from a wide array of computational tools8,9 and data-sharing initiatives10, NMR still relies heavily on manual, labor-intensive analysis, where the elucidation of a single structure takes anywhere from hours to weeks for novel chemicals or complex HSQC spectra11. Some structures have even taken years to resolve11, and the limited scope of HSQC libraries often leads to the rediscovery of known molecules or close analogs. To address these challenges, Computer-Assisted Structure Elucidation (CASE) has been developed, which uses computational algorithms to integrate experimental spectra, predicted chemical shifts, and connectivity information to systematically narrow down candidate structures12. Crucially, these workflows will not scale to the demands of drug discovery.

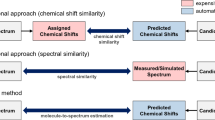

Several computational strategies have emerged to address these challenges to streamline structure matching from HSQC spectra, encompassing classical database-matching techniques and modern ML approaches5. Spectral database matching (viz., top-k lookup) compares the HSQC spectrum of an unknown compound against simulated/experimental spectra of candidate structures. However, because of the laborious nature of HSQC collection, no large public repositories of experimental 13C-1H HSQC spectra exist. Given that computational approaches tend to improve with more reference data, simulated HSQC spectra become an attractive alternative. Two commercial software packages exist for this purpose, MestreNova and ACD/Labs, which use proprietary algorithms to predict HSQC spectra from structure (often by predicting 1H and 13C chemical shifts) and then match the result to the query spectrum5.

Additionally, simulated HSQC spectra can be predicted using quantum chemical calculations13 and ML models5,14. To use these spectra for structure determination, a peak-matching algorithm is required to identify the best spectral match15. Other previous ML models relied on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) like SMART16, or more recently, SMART 2.017, which developed the ‘Moliverse’ for comparing continuous HSQC embeddings. Similarly, DeepSAT18 trained a CNN on experimental and simulated HSQC spectra to predict chemical features to suggest better candidate structures.

All the database methods above focus on finding the same or most similar structure by pairwise comparisons between unknown queries and known libraries. In mass spectrometry, molecular networking is used to find patterns among many MS2 spectra from which structural similarity can often be inferred. When multiple edges connect to a single node (representing an MS2 spectrum), the chances of annotation and interpretability increase, as numerous lines of evidence and higher-order relationships often support the structural interpretation of the query MS2. Popularized by GNPS8,19 after Watrous and colleagues20 first introduced it, molecular networking has been adopted by commercial software and standalone tools. This approach has led to the discovery of thousands of molecules in natural products, metabolomics, and exposomics.

Given the broad success of mass spectrometric molecular networking for compound annotation and discovery and the common use of NMR to validate MS results21,22, it is surprising that no comparable integration has emerged. While small-scale efforts have incorporated ¹H NMR tracking into MS² networks for metabolite identification23, there has been no development of NMR molecular networking frameworks on the scale of their MS² counterparts.

In this work, we broadly introduce NMR molecular networking and apply it to HSQC spectra. We expect that the core principles of MS² networking will generalize naturally to NMR-driven workflows. Although cosine similarity has been used in NMR comparisons17, the field lacks an analog to the modified cosine approaches central to MS² networking. To address this, we explored the Hungarian algorithm, a combinatorial optimization method, to more systematically optimize spectral assignments and annotations. Using calculated HSQC data, we demonstrate how a modified Hungarian approach can improve substructure annotation rates and provide a benchmark for evaluating the strengths and limitations of conventional database matching for structure identification. Motivated by these limitations, we established the first HSQC network-driven workflows for annotation propagation and compound dereplication. Finally, we introduce algorithmic molecular networking, in which the intrinsic graph structure of the network is exploited to improve structural candidate ranking in annotation workflows.

Results

Determining the structural limit of HSQC

A central question of this study is: to what extent can HSQC spectra support structural elucidation? To address this, we examined the theoretical relationship between spectral (viz. Hungarian-NN, Mod-Hung) and structural similarity (viz. Tanimoto, MCS, Hybrid) for experimental and simulated spectra. Figure 1 shows the normalized distributions of spectral distances plotted against structural similarity (Tanimoto) for all pairs of experimental HSQC used in this work.

Violin plots showing spectral distances (Modified Hungarian and Hungarian-NN) compared to Tanimoto similarity for 435,711 pairs based on 934 experimental HSQC spectra containing a minimum of 5 peaks. Analogous trends are seen for MCS and hybrid similarities (Figs. S7 and S8) and across simulated HSQC (Figs. S9–11). Spectral distances were generated for the Hungarian-NN and Modified Hungarian algorithms and normalized using CDFs fitting their empirical distributions (Figs. S12–13). Counts for each bin are available in Table S1.

Maximizing structural retrieval requires clear separation between high- and low-similarity pairs. In practice, Fig. 1 shows that low structural similarity does not guarantee high spectral distance, although the reverse is generally true. This mismatch reflects a lack of coherence, which we define as the consistent correspondence between structural similarity and spectral distance. In a fully coherent system, spectral distance would scale monotonically with structural similarity, such that unrelated scaffolds never appear spectrally close and chemically plausible candidates never appear spectrally distant. HSQC spectra, however, are not always coherent: chemically unrelated scaffolds may appear spectrally close due to functional group peak degeneracy (false positives, lower left, Fig. 1), while similar pairs can appear spectrally distant (false negatives, upper right, Fig. 1). Structural false positives present a major hurdle for structure assignment because of their relatively high frequency (Fig. 1, Table S1) and potential for misassignment. Examples of these structural/spectral discontinuities are shown in Figs. S1–3. These effects introduce a tangible risk of erroneous database lookup. Similar patterns were observed for both experimental and simulated HSQC spectra (Figs. S7 and S8). Comparisons of spectral distance to other structural similarity metrics (MCS, Hybrid) are shown in Figs. S9–10. Taken together, these results suggest that the uncertainty in HSQC-structure relationships may be intrinsic to the measurement itself, though more investigation is needed to conclusively confirm this claim.

Modified Hungarian distance for top-K lookup

Before introducing a novel tool for HSQC structure determination, it is essential to identify the limitations of the current status quo. To this end, we benchmarked the use of top-k lookup for structure retrieval and compared the Hungarian-NN and Modified Hungarian Distance algorithms (see Methods: Spectral Similarity). We performed top-k lookup for all experimental HSQC spectra against a fixed library of 99,719 simulated HSQC spectra, using the structural efficiency metric (see Methods: Evaluation Metrics for Structure Retrieval) across all three chemical coverage regimes (i.e., excellent match, close match, and poor match). Hyperparameter tuning for Modified Hungarian distance algorithm across these regimes is shown in Table S2.

Figure 2 shows that the Modified Hungarian algorithm outperforms the naive Hungarian-NN approach in all regimes, improving structural efficiency by an average of 0.05–0.09 hybrid similarity (see Methods: Structural Similarity, the hybrid similarity is the average of the MCS and Tanimoto metrics). This improvement is most pronounced for top-1 rankings and when an excellent match (HybridMax > 0.8) exists in the dataset. Despite this, in the absolute best-case scenario when the dataset contains an exact match (i.e., HybridMax = 1.0), top-k recovers only 48% of these matches in the top-1 and 73% in the top-5. Due to the broad relationship between HSQC and structural similarity (Fig. 1), one-dimensional HSQC comparisons may have an inherent ceiling in their ability to discriminate structure. More generally, we observe that structural efficiency decreases with decreasing chemical coverage (ηExcellentMatch > ηCloseMatch > ηPoorMatch; Fig. 2). As such, the suitability of top-k retrieval for compounds with novel or unknown chemistry is unclear.

Analysis of the structural efficiency of top-k lookup for experimental HSQC lookup on a library of 99,719 simulated spectra benchmarked with the Modified Hungarian and Hungarian-NN algorithms. Analysis is demonstrated for maximum score in the top-1 (A–C) and top-5 (D–F), and broken down by compounds that have an excellent match (0.8 <Hybridmax, A, D), a close match (0.6 <Hybridmax ≤ 0.8, B, E), and a poor match (Hybridmax ≤ 0.6, C, F) in the lookup library. Distributions are plotted using the seaborn Gaussian kernel density estimate (KDE) function, where the y-dimension is arbitrary. Structural efficiency is calculated using the hybrid similarity score (see Methods: Evaluation Metrics for Structure Retrieval).

To explore deeper, we performed an ablation of top-k lookup with varying spectral library sizes (Fig. 3). We performed a top-k retrieval for a fixed set of 500 randomly selected experimental HSQC spectra against randomly selected spectral libraries of increasing size (up to the entire synthetic library of approximately 400,000 spectra). Each larger library was a strict superset of all smaller ones. Figure 3A shows that increasing the library size measurably improves the maximum structural similarity found in the top-1/3/5. However, these gains are not limitless: the decreasing marginal improvement shows apparent convergence toward a performance maximum with increasing dataset size. This plateau is reinforced by Fig. 3B, which examines structural efficiency as a function of library size. While constant for top1/3 lookup, the top-5 lookup efficiency consistently decreases from 0.88 to 0.85 as the spectral library grows from 5000 to the size of the complete library. While modest in magnitude, this uniform decline suggests that expanding the lookup library is an inefficient way to improve structural elucidation due to a phenomenon we call dataset dilution.

Analysis of the average maximum hybrid similarity (A) and structural efficiency (η) (B) for the top-1/3/5 (green/orange/blue) lookup of 500 randomly sampled experimental HSQC spectra in randomly sampled HSQC spectral libraries of varying size retrieved using top-k lookup with the Modified Hungarian distance. Shaded areas represent 20% of the standard deviation of the distribution. All datasets of increasing size are supersets of all smaller datasets.

It’s intuitive that expanding a spectral library improves chemical coverage and the likelihood of finding an accurate match, explaining the initial gains in top-k hybrid similarity in Fig. 3A. However, expanding datasets also raises the likelihood of including false positives (see Fig. 1) or irrelevant compounds much faster than the likelihood of including a ‘correct’ structure, given that there are simply more possible incorrect structures than correct ones. This is the essence of dataset dilution: larger datasets bring diminishing returns and increased risk of false-positive matches due to HSQC/structure variability. Examples of top-5 rankings influenced by dataset dilution are shown in Figs. S1–S3.

It is currently unclear the extent to which these dataset dilution and other lookup limitation effects are caused by the use of simulated HSQC instead of experimental. This thought is purely hypothetical due to the lack of large-scale (i.e., >22,000) experimental HSQC libraries24. Well-curated experimental libraries could plausibly improve retrieval by capturing true chemical-shift dispersion, matrix effects, and more accurate peak positions, thereby tightening spectrum-to-structure coherence. The trade-off for experimental spectra is the need for a GNPS-like framework19 to align spectra across instruments and conditions. Nonetheless, Fig. 1 and S8 show that the non-coherent behavior appears in both experimental and simulated data. In this work, simulation is necessary to achieve the desired scale, but systematically exploring the trade-offs between experimental and simulated HSQC libraries will be essential to move the field forward.

HSQC molecular networking

Given (i) the ineffectiveness of top-k lookup in low-coverage regimes, (ii) inefficient structural recovery even under ideal (exact-match) conditions, and (iii) the increased risk of false positives upon library expansion, there is clear room for improvement for HSQC structure determination. For these reasons, we introduce HSQC Molecular Networking.

The concept is drawn directly from traditional MS2 molecular networking workflows, where a 2D network based on spectral similarity hopes to capture transitive patterns in the chemical space, structural similarity, and other relevant properties8,19. A complete description of our network construction workflow can be found in Methods: HSQC Molecular Networking and is illustrated in Fig. 4A–B. A sample subgraph is shown in Fig. 4C, and network statistics are shown in Fig. 4D–F. As shown in Fig. 4D, our final network contained 99,719 nodes and 401,859 edges. In our subgraph, the average/median node degree (# of edges) is 8.05/3, suggesting a relatively high structural selectivity, also shown in Fig. 4C.

Schematic illustration showing the construction of an HSQC molecular network with (A) input HSQC spectra that are then (B) compared pairwise exhaustively to get spectral similarities (Mod-Hung), structural similarity (Tanimoto, MCS, Hybrid), and mass differences for known substructures. The example subgraph (C) displays species sharing a coumarin backbone (highlighted in red) and illustrates subgraph localized structures, offering a comparative view through the lens of the HSQC molecular network. Histograms (D–F) show summary statistics for the complete network, including an analysis of node (log10) and edge degree (D), Modified Hungarian Distance (E), and Hybrid Similarities (F) for all edges, which were restricted to their respective thresholds (Mod-Hung <30, Hybrid > 0.6). The motivation for the hybrid threshold is shown in Fig. S14. Distributions of edge mass differences are shown in Fig. S15. Non-log distributions are plotted using the seaborn Gaussian kernel density estimate (KDE) function, where the y-dimension is arbitrary.

The value of HSQC molecular networking for structural analysis becomes obvious upon manual inspection of the subgraph shown in Fig. 4C. All species drawn in this two-hop neighborhood share a methyl-coumarin scaffold with an ether-linked amide (Fig. 4C, red). Coumarin, a natural product, was first isolated from tonka beans and is found in cinnamon, vanilla grass, and fenugreek25. We see that local neighborhoods do an excellent job of preserving modifications to this scaffold and that edges preserve distinctive structural motifs. Examples of these motifs include a backbone-fused cyclopentane ring (Fig. 4: nodes 2, 3, 4, and 5), fused cyclohexane ring (Fig. 4: nodes 1, 0, 8, and 9), piperidine ring (Fig. 4: green, nodes 6 and 7), carboxylic acid (Fig. 4: blue, nodes 1, 10, 8, and 9), and thioether groups (Fig. 4: yellow, nodes 1 and 10).

Applications of HSQC molecular networking

Annotation propagation and structure dereplication

Next, we present a potential use case for NMR Molecular Networking, in which an ‘unknown’ experimental spectrum is queried into our constructed molecular network (see Fig. 5). We propose that the use case demonstrated here could be readily integrated into annotation propagation or structure dereplication workflows like those commonly used in MS2 networking.

Query (unknown structure) edges were added with a Hungarian distance threshold of 35. Substructures highlighted in red show dissimilarities when compared to the query structure. Node indices are arbitrary. One-hop neighbors of the query are depicted in green and two-hop neighbors in blue. Additional structures are shown in Fig. S16.

In this case study, we obtained an unknown via the separation and isolation of plant extract, which was then measured using a Bruker 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a TCI 1.7 mm micro-cryoprobe. This compound was identified as the vinca alkaloid, Pleurosine. Pleurosine is a vinca alkaloid, a class of anti-mitotic natural products commonly incorporated in chemotherapy26. As shown in Fig. 5, this HSQC query is a complex spectrum describing a large molecule, a difficult elucidation for any NMR scientist. Manual structure elucidation was completed by first using a combination of literature search, MS2 database matching, and 1H NMR data to ascertain the structural class. Then, functional groups were identified using 2D NMR (e.g., HSQC) data, validated by literature search of other known vinca alkaloid structures. Finally, the full assignment was completed using the ACDLabs structure elucidator to match the spectra and confirm the identity of the unknown. We estimate that the structure elucidation of Pleurosine took between 4 to 5 h of human labor.

To demonstrate how NMR molecular networking could accelerate this workflow and improve over top-k lookup, we incorporate this HSQC into the network as an ‘unknown’ (see Fig. 5). Upon query addition to the molecular network, we see four one-hop neighbor structures where the top-1 structure (Node 1) has a structural efficiency of 95%, correctly identifying the vinca alkaloid scaffold with minor errors in sidechain substituents. In contrast to the manual workflow, the HSQC Networking annotation propagation is completed in less than a minute and provides several high structural similarity candidate structures (see Fig. 5, S16).

While showing successful structure annotation propagation, this case study also demonstrates additional potential pitfalls of top-k lookup when applied to unknown queries. Of the top-4 structures (also our one-hop neighbors), two are highly efficient matches (Nodes 1 and 6), one is reasonably efficient (Node 10), and one is a poor match that is a structural false positive containing very little of the correct scaffold (Node 7). However, in this ranking, the difference in the Hungarian distance between all four top-k candidates is small (ΔHung <4), and it is difficult to confidently differentiate the false positive from the true positive on the basis of spectral similarity alone. This example raises another potential issue with top-k lookup: how can we confidently identify correct structural candidates when the scoring metric does not provide clear separation between the top-ranked candidates?

A key benefit of HSQC Molecular Networking is the applicability of transitivity to increase the confidence of a structural candidate. At the one-hop neighbor level, the local neighborhood can highlight differences in highly confident candidates not shown by a pure ranking approach. For instance, both of the ‘high efficiency’ candidates (Nodes 1 and 6) are highly connected in the neighborhood of the query, sharing several one- and two-hop neighbors. In contrast, the false positive (Node 7) is completely disconnected from the neighborhood of the query. Moreover, we observe that several structures are not directly connected to the query, but are excellent for close structural matches (See Fig. S16). Most notably, this includes the highest rank structural candidate (Node 4, η = 1.0), which is not ranked highly by the Hungarian distance algorithm due to incorrect matching of the far-downfield aldehyde peak. Although not directly linked to the query, this structure is strongly embedded within its neighborhood, sharing multiple one- and two-hop connections. In practice, manual inspection of this network subgraph would likely highlight the candidate as viable based on transitivity alone.

Qualitatively, our HSQC molecular networks offer NMR scientists (i) structures that could be used for starting ‘inspiration’ with relevant functional group permutations that could plausibly describe the HSQC spectrum, (ii) patterns in repeated structural motifs highlighted by transitive that increase annotation confidence, and (iii) additional potential high-similarity candidates not retrieved by top-k approaches. This network-based context allows candidate structures to be supported by multiple, independent spectral relationships, reducing reliance on any single potentially noisy or inaccurate comparison. In doing so, it enables a more robust and chemically consistent propagation of annotations across related spectra.

Algorithmic molecular networking

To move beyond anecdotal evidence and test whether implicit graph structure can systematically improve retrieval, we introduce algorithmic molecular networking: a reranking strategy that integrates graph structure into candidate evaluation. Because HSQC molecular networks encode both spectral and structural similarity, we hypothesized that a spectrum’s neighborhood could provide additional context for identifying the most likely structure of an unknown. In practice, this means that candidates sharing structurally consistent neighbors with the query are themselves more likely to be correct, extending the observations of Fig. 5 into a generalizable framework.

To formalize this concept, we developed a workflow described in Methods: Algorithmic Molecular Networking, in which top-k candidates from spectral library search are reranked using graph information. Graph context serves as a correction factor to the Hungarian distance, mitigating cases where spectral and structural similarity are misaligned or inefficient. Figure 6A compares average hybrid similarity and structural efficiency before and after reranking. We focus on experimental spectra with ≥15 HSQC peaks (n = 263), as these spectra are more information-rich yet challenging to interpret due to spectral congestion. For granularity, we distinguish inefficient rankings (ηtop3 < 0.8) from efficient ones. This distinction matters: efficient rankings have little room for improvement, while inefficient ones are where reranking can have the greatest impact.

A Summary of the average hybrid score and structural efficiency (top 3/10) for 263 experimental HSQC spectra (>15 peaks) that have been ranked by top-k lookup (yellow) and re-ranked by our algorithmic molecular networking approach (blue) with the relative improvement highlighted (B) Illustration of top-3 ranking for a steroid using the two methods, where algorithmic networking is able to identify highly similar structural candidates far outside the top-10 determined by top-k lookup. C Example of an ‘incomplete’ triangle where three highly structurally similar steroid derivatives are ‘missing’ an edge in the molecular network due to a high Modified Hungarian Distance calculated arising from heteroatom mismatch.

For inefficient rankings (ηtop3 < 0.8, n = 86), algorithmic molecular networking produces significant gains: average hybrid similarity increases by +18.7% (relative improvement, top-3) and +7.4% (top-10), while structural efficiency improves by +26.6% and +11.6%, respectively. Across all annotations, reranking increases the proportion of annotations that are both highly efficient (η > 0.9) and yield relevant structures (Average Hybrid > 0.5) by +14.9% and +9.0% in the top-10 lookup (Fig. 6A). This indicates reranking leaves efficient rankings intact, since the Hungarian distance weighting provides inertia from direct spectral matching. Additional results for high and low efficiency rankings are shown in Fig. S17.

Figure 6B illustrates the reranking improvement with a steroid query: a class of compounds notoriously difficult to resolve by HSQC due to the dominance of non-diagnostic aliphatic C–H signals in the ‘sterol envelope’27. Top-k retrieves several high spectral similarity candidates (Mod-Hung. <30 - determined ad hoc by manual examination of structural pairs at different thresholds), but none exceed a hybrid similarity of 0.35 because they do not correctly match the fused hydrocarbon ring scaffold. After reranking, two excellent matches (Hybrid = 0.77, 0.60) containing the correct steroid backbone are promoted into the top-3. Notably, these candidates were originally buried at ranks 30 and 66, far beyond the top-5/10 that an NMR scientist might realistically inspect. Complete top-5 rankings are shown in Figs. S18 and S19. These compounds had Hungarian distances (32.3, 33.2) similar to non-steroids in the original top-3 (29.9, 30.3, Fig. 6B), illustrating dataset dilution once again: non-steroids with many aliphatic C–H bonds artificially align with the steroid backbone, lowering spectral distances and crowding out the correct hits.

Herein lies the value of algorithmic molecular networking: network context via the PWRA score supports candidates with multiple independent spectral relationships, reducing reliance on any single noisy comparison. In doing so, it improves coherence, where the most plausible candidates are consistent with both spectral similarity and the structural context of their neighborhood. Figure 6C further shows an example of missing coherence: three derivatized steroids differing only in heteroatom side chains. Although the backbones are identical, mismatched heteroaromatic peaks (e.g., furan vs. pyridine, electron-donating vs. withdrawing aromaticity, see Fig. S20) inflate spectral distance, preventing closure of the “triangle.” More discussion of these effects is available in the Supplementary Information: Incomplete Triangles and in Fig. S21. By accounting for transitivity in our graph topology ranking, algorithmic molecular networking can resolve incomplete triangles and recover structurally valid candidates that top-k lookup alone would miss.

More broadly, algorithmic molecular networking shines when the query HSQC is dense and the lookup library has low structural resolvability. When an HSQC contains a distinctive diagnostic peak pattern with low library overlap, top-k surfaces a clearly separated, confident hit. But for steroids, peptides, sugars, heavily functionalized scaffolds, and large molecules, HSQC patterns overlap across many potential decoys and top-k becomes diluted, yielding numerous “good” candidates with similarly low spectral distances and little separation from one another. In these cases, algorithmic molecular networking adds higher-order, transitive structural discrimination: by leveraging shared neighborhoods, we observe that NMR molecular networks can promote the truly plausible candidates and resolves ties that top-k alone cannot.

Discussion

In this work, we tackle the question: to what extent can structures be elucidated from HSQC spectra? Across both simulated and experimental datasets, we find that direct pairwise comparison of spectra is often insufficient: spectral distance does not reliably correspond to structural similarity, leading to potential structural false positives. Our evaluation of top-k lookup approaches further highlights these limitations. Even in cases where exact structural matches were present, top-k retrieval often failed to rank them as the top candidates. More generally, we observed that top-k recovers an average of ~70-80% of the available similarity in a spectral library. As the dataset size increases, retrieval efficiency stagnates or declines due to dataset dilution, where an influx of medium-quality candidates and structural false positives reduces the likelihood of recovering the best match. Taken together, these results underscore the fundamental challenges of relying solely on pairwise comparisons of spectra for direct structure retrieval, while also emphasizing scalability as a persistent obstacle for high-throughput screening using NMR.

This gap motivates a shift in perspective: rather than treating each spectrum as an independent query, methods should exploit the implicit structure of spectral libraries, where transitive relationships between spectra encode higher-order patterns more closely aligned with chemical similarity. To these ends, we introduce HSQC molecular networking as a framework for identifying patterns in NMR-structure space. Inspired by traditional MS-based molecular networking, we map HSQC spectra as nodes connected by edges that encode both spectral and structural similarity, allowing the network to capture transitivity and neighborhood structure that pairwise comparisons cannot. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to construct NMR or HSQC molecular networks. With this framework, we showcase applications in annotation propagation and structure dereplication. By incorporating ‘unknown’ experimental queries into the network, we demonstrate how transitivity can eliminate false positives, increase the confidence of true positives, and reveal novel candidate structures that are overlooked by top-k approaches.

Building on this foundation, we develop algorithmic molecular networking to rerank structural candidates using network topology indices that describe structural transitivity (e.g., shared neighbors). This reranking acts as a correction factor for spectral similarity metrics, rescuing complex spectra and inefficient match regimes while preserving accuracy when direct spectral matching is already reliable. Together, these methods shift HSQC interpretation from isolated comparisons to a context-aware, internally-consistent network and provide a more scalable route toward NMR-driven structure determination. Our approach provides end users with an interactive tool that can be used for structural inspiration, confidence via neighborhood consensus, and exploration of functional group modifications within a chemical class en route to elucidation.

While HSQC molecular networking represents a meaningful step toward automated structure elucidation, it is not without limitations. Because we rely on simulated spectra, matching will inherit inaccuracies from simulations and overlook spectral artifacts (noise, impurities). Constructing a molecular network is computationally demanding: the all-vs-all pairwise comparison of HSQC spectra scales quadratically with the number of spectra. Our network is also derived from natural products libraries, which may reduce its relevance for other chemical classes. For algorithmic molecular networking, our proof-of-concept analysis also focused only on spectra with more than 15 peaks. For more targeted applications of the technology, it is also critical to determine a clear relationship between high-efficiency and low-efficiency rankings based on the structure and/or HSQC spectra.

Overall, NMR molecular networking offers immediate value for benchtop scientists by streamlining the interpretation of HSQC spectra and accelerating structure elucidation for natural product discovery, untargeted metabolomics, and drug development research. In each of these settings, network-based consensus provides a practical starting point that reduces the interpretive burden, yielding practical starting structures for an expert. Looking forward, the fusion of HSQC and MS² molecular networks represents a natural evolution: fragmentation-derived substructural motifs and NMR-derived scaffolds in a hybrid network present an attractive, complementary view of chemical space derived from experimental measurements. Such multimodal frameworks would broaden the reach of dereplication, enhance annotation confidence, and open new opportunities in metabolite characterization and chemical biology. Ultimately, this work moves toward the long-term goal of high-throughput, non-targeted structure determination from experimental data, a direction in which our efforts are ongoing.

Methods

HSQC datasets

To generate the synthetic HSQC library, we combined natural products from the COCONUT database28 and LOTUS database29. We then filtered structures to include only compounds (neutral molecules) with masses between 120 and 1200 Da, containing exclusively the elements C, H, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, and I. After filtering, our final library contained 373,526 unique compounds. For all species, we simulated HSQC NMR spectra using the Mestrelab Mnova NMRPredict software and the internal ECMAScript scripting engine and automatically exported the F2 and F1 HSQC NMR shifts. These spectra are all made available alongside this study (see Data and Software Availability).

Since computing an HSQC molecular network requires an all-vs-all approach, this would require roughly 70 billion edge calculations. For computational feasibility, 100,000 spectra were randomly sampled for HSQC networks, which we further filtered. We found that lipids result in non-diagnostic ‘hairballs’ (i.e., minimal structural selectivity) in the molecular network, so we filtered them from the dataset using heuristic rules. Compounds with fewer than five HSQC peaks were excluded because they have minimal diagnostic information and often present as structural false positives.

To benchmark the methods in the study, we utilized a library of 1046 publicly available experimental HSQC spectra that we downloaded from PubChem30. These experimental 1H-13C NMR spectra (HSQC) were small molecules and were deposited by the maintainers of the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB). These experimental spectra were filtered identically to the computed HSQC.

Similarity metrics

Spectral similarity

The crux of structure elucidation from HSQC is often the correct assignment of peaks between query and database lookup spectra5. HSQC spectra can be represented as unordered sets of (1H, 13C) peaks, where large clusters are often difficult to disentangle. The Hungarian Algorithm (also known as the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm) is commonly used to address this problem, by optimally matching peaks via a cost matrix to minimize the Euclidean distance of all pairs31. Priessner et al.5 pioneered the optimization of this algorithm for HSQC, benchmarking different strategies for peak matching and padding in cases where spectra have different numbers of peaks. Their study concluded that Hungarian Distance combined with Nearest-Neighbor (Hungarian-NN) padding performed best for HSQC matching.

Modified Hungarian Distance

In this work, we aim to better understand the limitations of the correlation between HSQC spectral similarity and structural similarity (see Results: Determining the Structural Limit of HSQC). To augment this exploration and maximize the relationship between spectral and structural similarities, we developed a Modified Hungarian Distance with several key modifications to the original algorithm.

First, using estimated uncertainties for 1H/13C peak widths (σH / σC = 0.01 / 0.2 ppm), we normalize all 1H and 13C coordinates to dimensionless quantities. This ensures that the 13C coordinate space does not dominate the lower-magnitude 1H coordinates. Second, we acknowledge that structural similarity does not correspond one-to-one with spectral similarity because of the abstraction of structure into an HSQC spectrum. Two structures may share common substructures or functional groups. Yet, the exact peaks for these moieties can shift within a specific ppm range due to differences in local magnetic environments, solvent effects (particularly in the 1H dimension), instrumental variation, or experimental noise.

A central goal of the Modified Hungarian Distance is to capture partial structure matches by introducing a structural tolerance based on the Euclidean distance associated with the functional group uncertainty.

Where fC and fH are the functional group tolerances. In this work, we found that values of 2.5 ppm and 0.5 ppm provided the best performance for structure retrieval for 13C and 1H tolerances, respectively. In the Hungarian cost matrix, all pairs outside of this tolerance are penalized by an additional factor added to the calculated distance to discourage assignment and reward matches within the tolerance range. We also include the different padding strategies (zero, truncation, nearest neighbors) described by ref. 5. For all subsequent discussion, we calculate a) the Modified Hungarian distance and b) the Hungarian-NN distance5 (see Software and Data Availability). The modified cosine metric for MS2 similarity was developed to enable the original MS2 molecular networks and has served to consolidate the field16. We introduce the Modified Hungarian distance to enable NMR molecular networking, and hope that it can serve a similar purpose.

Structural similarity

While Tanimoto similarity is the most commonly used metric for structural similarity, it is well known to be limited for reasons including but not limited to a bias on molecular weight32, fingerprint variability33, and due to the intrinsic limitations of binary molecular representations34. As such, we also consider two additional structural similarity scores in our analysis of HSQC. First, the Maximum Common Subgraph (MCS, see Supplementary: Structural Similarity Metrics) between two structures35, which can reward partial substructure matches more heavily than a pure Tanimoto approach, but may be limited because of computational scalability, perturbation sensitivity, and lack of global molecular context36,37. However, given that both Tanimoto and MCS have their own implicit biases in rewarding structural similarity, we seek to find a better metric. To these ends, we also incorporate a ‘hybrid’ similarity, which is defined as:

This metric seeks to find a compromise between the benefits and limitations of the Tanimoto and MCS metrics and offset the biases of each similarity metric. In this study, we use Hybrid similarity metric as our primary metric for evaluation based on the input of our in-house NMR scientists (see Supplementary: Structural Similarity)

Coverage Regimes

Understanding the bounds of a structural similarity metric (especially with respect to structural efficiency) is particularly important when there is no guarantee of an exact (or even close) match in the dataset, such as in natural product or dark metabolite research. To this end, we define three regimes of chemical coverage to assess performance as a function of available structural similarity:

-

i).

Excellent Match (0.8 > Hybridmax)

-

ii).

Close Match (0.6 <Hybridmax ≤ 0.8)

-

iii).

Poor Match (Hybridmax ≤ 0.6)

Examples of structures in each regime are shown in Figs. S1–S5. Assessing performance in low-coverage regimes provides a worst-case scenario evaluation, particularly valuable for novel or unknown chemistry. Distributions of Hybridmax values for experimental annotations are shown in Fig. S6.

Evaluation metrics for structure retrieval

Limitations of top-k accuracy

In database retrieval, a query spectrum is compared against a reference library of predicted or experimental spectra to identify candidate molecular structures ranked by spectral similarity. Top-k accuracy is the traditional benchmark for evaluating structure retrieval in HSQC lookup libraries. For each query spectrum, candidate structures are ranked by similarity, and success is defined by whether the ‘correct’ structure appears within the top k positions of that ranked list. While intuitive and easy to interpret, this metric alone does not fully capture the challenges of HSQC-based structure elucidation and has several limitations.

First, the metric used to optimize any workflow should reflect the needs of the person who will ultimately be using the tool. In this study, structure elucidation workflows are intended to work with the NMR scientist to accelerate structure elucidation. Top-k accuracy assumes that there is precisely one ‘correct’ answer for a given lookup query. While returning the exact structural match is the preferred outcome in an ideal world, a correct backbone or scaffold may be sufficient as a starting guess, which human expertise can refine to identify the exact match. These partial matches can accelerate the structure elucidation process, which is otherwise extremely tedious; for challenging structures, generating a structure from HSQC can take weeks to months (Elyashberg, 2015).

Second, there is no guarantee that an exact match exists in the lookup database, particularly in studies aiming to identify novel chemical structures38.

Lastly, because HSQC is abstracted from structural reality and does not fully describe a molecule’s structure (e.g., no information on quaternary carbons), an exact structure cannot always be confidently ascertained from HSQC alone. HSQC encodes only C–H bonds with indirect descriptions of functional groups, so structure elucidation from a single HSQC spectrum will always suffer from permutation uncertainty. For this reason, NMR scientists routinely incorporate COSY, NOESY, DEPT, and 1H/13C NMR spectra to resolve structures39.

Structural efficiency (η)

With this framing, we introduce a metric to describe the success of HSQC matching: structural efficiency, defined as

where η is the efficiency of a prediction, sk(max) is the maximum structural similarity in the top-k ranked compounds, and smax is the compound with the maximum structural similarity to the query in the dataset. For top-k studies, we only consider the best structure in the top-100 ranked by Hungarian distance for the ‘maximum’, reflecting the practical limit of how many candidates a human expert could feasibly review. Performing structural similarity calculations (specifically MCS) for the entire lookup library would be highly computationally impractical.

For example, if the most similar compound in the database has a similarity of 0.8, and the best structure in the top-3 has a similarity of 0.6, the efficiency of top-3 retrieval is 0.6/0.8 = 0.75. This avoids penalizing close matches that are not the absolute best in the dataset: if a retrieved candidate has a hybrid similarity of 0.80 versus a best candidate at 0.84, the efficiencies are 0.95 and 1.00, respectively. Such a candidate would still serve an NMR scientist well.

HSQC molecular networking

The goal of HSQC Molecular Networking is to leverage numerous lines of evidence and higher-order relationships between HSQC to better support the structural interpretation of queries, leveraging the core principles of MS2 networking. HSQC molecular networks are generated by performing a pairwise all-vs-all comparison of MestreNova simulated HSQC spectra (n = 99,719) using Modified Hungarian similarity to score pairs of HSQC spectra. It is important to note that the number of edge calculations for a given network will scale quadratically with the number of input spectra. We build our network using only a meaningful sample of the total library because of this prohibitive network construction runtime scaling (100,000 vs 414,000 spectra: 5 billion vs. 70 billion edge calculations). Only similarities below an empirically set threshold (Mod-Hung. ≤ 30) were retained as edges.

For all edges with known structures (all simulated spectra), we also calculated structural similarity (i.e., Tanimoto, MCS, and Hybrid) and embedded these as edge features. We observed that spectral similarity does not always maximize structural similarity (see Fig. 1), and many edges were presented as ‘structural false positives’ (see Figs. S1–3). Given that the goal is to create a network that communicates links between spectral and structural similarity, we set a structural similarity threshold for edges with known structures (Hybrid > 0.6) to further refine the relationships of the network.

Algorithmic molecular networking

In essence, algorithmic molecular networking re-ranks a set of HSQC spectra in the HSQC Molecular Network based on their network topology (e.g., connectivity/clustering within the molecular network) with the goal of improving the rate of structure retrieval. The re-ranking is performed by calculating a metric based on the local neighborhood, using information embedded in nodes and edges. Pseudocode for this procedure is shown in Supplementary: Algorithmic Molecular Networking. Since we are interested in demonstrating the improvements this work offers over top-k lookup, we frame it in terms of reranking the results of top-k lookup. Given that database search is the dominant paradigm for structure retrieval via HSQC5, we need to demonstrate that our tool can outperform this baseline.

First, for a given query, we perform a top-k lookup against the reference library using modified Hungarian distance, producing an initial ranked list of candidates. We use a database with the same size (n = 99,719) as the molecular graph to maximize comparability. We then add the query to the graph using a more permissive threshold (Mod-Hung <40 - determined ad hoc to maximize annotation efficacy without diluting query neighbors) to ensure graph connectivity and identification of relevant relationships. We also explored lower thresholds, but found that they were often prohibitive if an excellent match was not present in the dataset. We also required that, in order to re-rank a query, the query must have a minimum of two edges in the network. In the top-100 rankings (truncated again for human and computational feasibility), we calculate network-informed scores to provide the basis for reranking. The assumption underlying this procedure is ‘if a network reflects coherent structural/spectral similarity, compounds with many shared neighbors (or a shared neighborhood) to my query are more likely to be structurally similar to that query’. We tested several graph indices (e.g., Jaccard) calculated using pairwise sets of one-neighbors described in more detail in Supplementary: Algorithmic Molecular Networking.

Ultimately, we found that the product-weighted resource allocation (PWRA) achieved the best performance in identifying structural candidates when weighted by hybrid structural similarity. Product-Weighted Resource Allocation (PWRA) is a graph-based similarity metric that extends the classic Resource Allocation (RA) index40. In RA, two nodes are considered similar if they share neighbors, with each neighbor contributing inversely to its degree. PWRA modifies this by weighting each neighbor’s contribution by the product of the edge weights to that neighbor. We use the hybrid similarity score (for known neighbors) to PWRA edge weights. For edges connected to the query (an unknown), product weights are set to 1. While PWRA was successful in improving inefficient rankings, we found that it had the adverse effect of displacing compounds ranked well by Modified Hungarian Distance. To mitigate this effect, the final score for each candidate is calculated using an 80:20 weighted average of the original Hungarian distance score and the PWRA score:

In doing so, rankings with a clear ‘best’ Hungarian score and likely to preserve coherence between structural/spectral similarity will be unaffected, and the network topology will refine those inefficient rankings with many highly similar candidates. Another way to think about this metric is as a ‘correction factor’ for Modified Hungarian Distance, accounting for the inefficient or false positive cases that can be corrected by the higher-order structural relationships found in the network.

Implementation

All scripts used in this work were written in Python version 3.10 and managed using the Poetry environment. For data manipulation, we employed widely used libraries such as Pandas41, NumPy42, and SciPy43. Visualizations were generated using seaborn44 and Matplotlib45). Chemical structures were described as SMILES extracted from InChIKeys and subsequently processed using RDKit46.

Data availability

All simulated HSQC spectra and HSQC networks used in this study data are available at https://zenodo.org/records/17081209. Experimental HSQC used for benchmarking can be downloaded freely from the HMDB.

Code availability

All scripts and notebooks needed to reproduce this work are available at https://github.com/enveda/NMR-Networking/.

References

Jonas, E. & Kuhn, S. Rapid prediction of NMR spectral properties with quantified uncertainty. J. Cheminform. 11, 50 (2019).

Kuhn, S., Tumer, E., Colreavy-Donnelly, S. & Moreira Borges, R. A pilot study for fragment identification using 2D NMR and deep learning. Magn. Reson. Chem. 60, 1052–1060 (2022).

Öman, T. et al. Identification of metabolites from 2D 1H-13C HSQC NMR using peak correlation plots. BMC Bioinforma. 15, 413 (2014).

Markley, J. L. et al. The future of NMR-based metabolomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 43, 34–40 (2017).

Priessner, M. et al. HSQC spectra simulation and matching for molecular identification. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 3180–3191 (2024).

Reynolds, W. F. & Enríquez, R. G. Choosing the best pulse sequences, acquisition parameters, postacquisition processing strategies, and probes for natural product structure elucidation by NMR spectroscopy. J. Nat. Products 65, 221–244 (2002).

Kuhn, S., Kolshorn, H., Steinbeck, C. & Schlörer, N. Twenty years of nmrshiftdb2: a case study of an open database for analytical chemistry. Magn. Reson. Chem. 62, 74–83 (2024).

Aron, A. T. et al. Reproducible molecular networking of untargeted mass spectrometry data using GNPS. Nat. Protoc. 15, 1954–1991 (2020).

Krettler, C. A., & Thallinger, G. G. A map of mass spectrometry-based in silico fragmentation prediction and compound identification in metabolomics. Brief. Bioinform. 22. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab073 (2021)

Bushuiev, R. et al. MassSpecGym: a benchmark for the discovery and identification of molecules. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 110010–110027 (2024).

Elyashberg, M. Identification and structure elucidation by NMR spectroscopy. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 69, 88–97 (2015).

Elyashberg, M. & Argyropoulos, D. Computer assisted structure elucidation (CASE): current and future perspectives. Magn. Reson. Chem. 59, 669–690 (2021).

Hoffmann, F., Li, D. W., Sebastiani, D. & Brüschweiler, R. Improved quantum chemical NMR chemical shift prediction of metabolites in aqueous solution toward the validation of unknowns. J. Phys. Chem. A 121, 3071–3078 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. TransPeakNet for solvent-aware 2D NMR prediction via multi-task pre-training and unsupervised learning. Commun. Chem. 8, 51 (2025a).

Pierens, G. K., Mobli, M. & Vegh, V. Effective protocol for database similarity searching of heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra. Anal. Chem. 81, 9329–9335 (2009).

Zhang, C. et al. Small molecule accurate recognition technology (SMART) to enhance natural products research. Sci. Rep. 7, 14243 (2017).

Reher, R. et al. A convolutional neural network-based approach for the rapid annotation of molecularly diverse natural products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4114–4120 (2020).

Kim, H. W. et al. DeepSAT: learning molecular structures from nuclear magnetic resonance data. J. Cheminform. 15, 71 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 828–837 (2016).

Watrous, J. et al. Mass spectral molecular networking of living microbial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1743–E1752 (2012).

Lee, S. R. et al. Molecular networking and computational NMR analyses uncover six polyketide-terpene hybrids from termite-associated Xylaria isolates. Commun. Chem. 7, 129 (2024).

Schmid, R. et al. Ion identity molecular networking for mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in the GNPS environment. Nat. Commun. 12, 3832 (2021).

Hou, X. M. et al. Integrating molecular networking and 1H NMR to target the isolation of chrysogeamides from a library of marine-derived Penicillium fungi. J. Org. Chem. 84, 1228–1237 (2019).

Li, Y., Xu, H., Hong, A. B. D. P. 2DNMRGym: an annotated experimental dataset for atom-level molecular representation learning in 2D NMR via surrogate supervision. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.18181 (2025).

Toma, A. C., Stegmüller, S. & Richling, E. Coumarin contents of tonka (Dipteryx odorata) products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 251, 513–517 (2025).

Johnson, I. S., Armstrong, J. G., Gorman, M. & Burnett, J. P. Jr The vinca alkaloids: a new class of oncolytic agents. Cancer Res. 23, 1390–1427 (1963).

Goad, L. J., & Akihisa, T. One-dimensional and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of sterols. In Analysis of Sterols Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1447-6_10 (1997).

Chandrasekhar, V. et al. COCONUT 2.0: a comprehensive overhaul and curation of the collection of open natural products database. Nucleic Acids Res. gkae1063. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1063 (2024).

Rutz, A. et al. The LOTUS initiative for open knowledge management in natural products research. Elife 11, e70780 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1373–D1380 (2023).

Kuhn, H. W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 2, 83–97 (1955).

Fligner, M. A., Verducci, J. S. & Blower, P. E. A modification of the Jaccard–Tanimoto similarity index for diverse selection of chemical compounds using binary strings. Technometrics 44, 110–119 (2002).

Mellor, C. L. et al. Molecular fingerprint-derived similarity measures for toxicological read-across: Recommendations for optimal use. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 101, 121–134 (2019).

Bajusz, D., Rácz, A. & Héberger, K. Why is Tanimoto index an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations. J. Cheminform. 7, 20 (2015).

Houbraken, M. et al. The index-based subgraph matching algorithm with general symmetries (ISMAGS): exploiting symmetry for faster subgraph enumeration. PloS One 9, e97896 (2014).

Cao, Y., Jiang, T. & Girke, T. A maximum common substructure-based algorithm for searching and predicting drug-like compounds. Bioinformatics 24, i366–i374 (2008).

Wang, Y., Backman, T. W., Horan, K. & Girke, T. fmcsR: mismatch tolerant maximum common substructure searching in R. Bioinformatics 29, 2792–2794 (2013).

Hart, C. E. et al. Defining the limits of plant chemical space: challenges and estimations. GigaScience 14, giaf033 (2025).

Chontzopoulou, E., Tzani, A., Paschalidou, K., Zoupanou, N., & Mavromoustakos, T. Development of a teaching approach for structure elucidation using 1D and 2D homonuclear and heteronuclear NMR spectra. J. Chem. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00402 (2025).

Lü, L. & Zhou, T. Link prediction in weighted networks: the role of weak ties. Europhys. Lett. 89, 18001 (2010).

McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In SciPy (Vol. 445, No. 1, pp. 51–56). https://pandas.pydata.org/ (2010).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Waskom, M. L. Seaborn: statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3021 (2021).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Landrum, G. RDKit: open-source cheminformatics, http://www.rdkit.org/. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7415128 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank MestreLab Research for granting permission to release simulated HSQC spectra alongside this work. We would also like to thank Prof. Connor W. Coley for his feedback. C.M.K.S. acknowledges financial support from NSERC in the form of a Canadian Graduate Scholarship (Doctoral).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M.K.S. conceived the project, conducted the experiments and analysed the data. T.K. prepared the datasets. D.H., G.V., and D.D.-F. helped designed the experiments. J.S. supported running the experiments. E.G., A.P., V.M., C.A.K. and P.C.D. provided feedback during the project. D.D.-F. supervised the project. The manuscript was initially drafted by C.M.K.S. and D.D.-F. and edited through contributions of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.C.D. is an advisor and holds equity in Cybele, BileOmix, Sirenas, and a scientific co-founder, advisor, holds equity and/or received income from Ometa, Enveda, and Arome with prior approval by UC San Diego. P.C.D. also consulted for DSM animal health in 2023. All other authors were employees of Enveda Therapeutics Inc. during the course of this work and have a real or potential ownership interest in the company.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks David A. Snyder and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stienstra, C.M.K., Song, J., Healey, D. et al. Structure characterization with NMR molecular networking. Commun Chem 9, 28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01839-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01839-x