Abstract

This review highlights a clear change in focus in the study of coacervate droplets as protocell models, moving from their role as passive microreactors that concentrate reactants to their function as chemically programmable matter capable of information processing and lifelike behaviors. We use “Input → Written State → Output” as a guiding workflow, and discuss recent advances through three operational pillars. The first is local reactivity control, where the droplet microenvironment directs reaction pathways and spatial enzyme organization, including feedback loops where reactions regulate the physical state. The second pillar is the writing of internal states, which treats droplets as stimuli-addressable chemical memory with targets of selectivity, latency, and erasability. The third pillar involves external readouts, which transduce internal states into programmed cargo release and chemical signaling within environments and across protocell communities. Finally, we outline future perspectives, discussing the transition from programming deterministic functions to directing the evolution of protocell populations that exhibit collective behaviors. By offering a cohesive conceptual toolkit, this review provides new insights beyond the simple notion of “faster reactions in droplets” and toward the engineering of higher-order, cooperative architectures with lifelike functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coacervates are water-rich liquid droplets formed by the associative liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) of multivalent components such as polyelectrolytes, nucleic acids, peptides, or dynamically bonding small molecules1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Their potential as models for membraneless organelles in bottom-up synthetic biology is rooted in their hallmark liquid traits, including fusion, wetting, and rapid molecular exchange with their surroundings10,11,12,13. This has made them broadly useful across nanobiotechnology in applications ranging from drug delivery and biosensing to tissue engineering and adhesives14,15,16,17. A small set of practical control parameters, such as charge density, ionic strength, pH, and light-addressable chemistries, allows for the tuning of key physical properties like partitioning, viscosity, and interfacial tension18. Such control enables the design of specific microenvironments and, when in-droplet chemistry rewires the molecular interaction network, can even drive organelle-like structural evolution.

At its core, the utility of coacervates has long been attributed to selective partitioning, which enriches reactants and turns the droplets into effective microreactors19,20. The condensed phase imposes transport biases and interfacial resistances that concentrate substrates, modulate effective rate constants, and can shift reaction mechanisms relative to bulk solutions. Recent theoretical work frames these effects conceptually, with condensate volume and client partitioning emerging as explicit design variables that shape trade-offs across different reaction classes21. Building on this microenvironmental leverage, a significant conceptual evolution is underway. The field is shifting its focus from viewing coacervates as static microreactors to understanding them as active, chemically programmable matter. In this new paradigm, reaction networks are designed to write and erase a droplet’s physicochemical state. Fuel-driven or reaction-coupled LLPS affords temporal control over assembly, opening windows for transient compartments, size regulation, and programmed growth or division22,23. Together, these capabilities position coacervates as modules for chemical information processing.

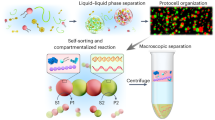

While most recent reviews have focused on droplet materials18, patterning24, drug-delivery platforms25, biomimetic behaviors26,27, or their use as single-purpose microreactors19,20,21,28,29, this review synthesizes these developments through a new, functional lens. We use “Input → Written State → Output” as a guiding workflow rather than a strict checklist, and structure the Review around three operational pillars. We first survey local reactivity control, then detail how chemical networks can write persistent or transient states inside droplets, and finally examine how these internal states are transduced into external readouts like programmed cargo release and chemical signaling. In this framing, state writing functions as a form of stimuli-addressable chemical memory with practical targets of selectivity, latency, and erasability (Fig. 1). Table 1 condenses the representative examples across the three pillars (local reactivity control/state writing/external readouts) and provides a compact cross-reference linking each pillar to the corresponding sections and examples. Early demonstrations of logic-like behavior in protocell consortia hint at the potential for emergent collective responses30,31,32. By reframing coacervates as composable units for chemical logic, we guide the transition from a focus on “faster reactions in droplets” to the design of programmable, lifelike architectures.

Chemical and physical inputs (e.g., composition, stimuli, fuels) tune local reactivity control to concentrate and steer small-molecule and enzymatic reactions and gene expression. Such chemistry can also write material, spatial, and temporal states (shells/scaffolds, nucleus-like domains/vacuoles, fuel-pulse–set lifetimes) and can yield external readouts that enable communication with protocells, living systems, and the environment.

Local reactivity control

Coacervates can regulate reaction networks by providing a microenvironment with features that bulk water typically lacks, such as selective partitioning, tunable acidity, hydrophobic pockets, and gentle crowding. The outcomes of reactions within these environments can be sorted into three encounter modes. When reaction partners are colocalized in the condensed phase, rates are typically accelerated. If only one reactant is enriched, the benefit is diluted. Encounters at the droplet interface can impose delays or slowdowns. The following synthesis examines small-molecule reactions, nucleic-acid catalysis, and enzymatic or expression modules through this lens, where scaffold chemistry ultimately determines which mode dominates.

Small-molecule reactions in coacervates

This section explores the tangible contributions of the coacervate phase to small-molecule chemistry, under the premise that reactants occupy the same phase with active exchange. Two key capabilities transfer across contexts. First, formulation can reweight the medium, allowing the same reaction pathway to explore different operating windows. Second, recognition elements or photophysical components placed in-phase can convert encounter frequency into directional control.

A clear example of medium reweighting is provided by interpolyelectrolyte complex droplets hosting the Knoevenagel condensation (Fig. 2a). By tuning pH, salt, and crowding, the reaction can be guided into a reproducible high-efficiency window where it runs noticeably faster, slowing sharply outside this window. The response curves can be monotonic or show an inverted-U shape, demonstrating that formulation alone shifts reaction feasibility and apparent pace33. The same microenvironmental logic applies when coacervates concentrate gatekeepers for prebiotic or redox transformations. The enrichment of peroxides, metal ions, or anions can turn a negligible reaction in bulk into an appreciable one in droplets, while diluting or sequestering these species returns the system to a slow regime34,35.

a Formulation reweights the medium. Interpolyelectrolyte complexes (PDADMAC/PAA) provide a productive window for the Knoevenagel condensation: (I) reaction and coacervate droplets schematic; (II) time-resolved UV–vis shows faster product build-up with coacervate droplets than in buffer (inset, absorbance–time trace). Reproduced with permission33. Copyright 2025, Royal Society of Chemistry. b Coacervate droplets engulf hydrophobic reactants as embedded organic microdroplets. At the coacervate/organic interface, a PAA-rich layer interacts with the thiazolium precatalyst to generate the NHC in situ, enabling base-free Stetter C-C coupling and yielding higher conversion/selectivity than in water or THF—an interface-driven effect beyond simple concentration. Reproduced with permission36. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society. c In-phase photophysics as an antenna. TPPS/DEAE–dextran coacervates assemble TPPS into porphyrin J-aggregates and enrich iodide (I⁻) in the dense phase. Upon visible irradiation (hν), excited TPPS transfers energy to ³O₂ to generate ¹O₂, which oxidizes I⁻ to I₃⁻, resulting in enhanced photocatalytic iodide oxidation (stepwise scheme). Reproduced with permission37. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. d Hydrophobic subcompartments act as microreactors. DNA protocells doped with a PEG-based amphiphilic block copolymer (forming hydrophobic subcompartments) localize and accelerate a self-reporting retro-Diels–Alder reaction: a protected dansylfuran pro-fluorophore undergoes retro-DA cleavage in the presence of a nucleophilic catalyst (e.g., DMAP: 4-dimethylaminopyridine) to release fluorescent dansylfuran. (I) design schematic; (II) fluorescence at 570 nm vs time inside the polymer-doped protocells versus plain protocells (inset, initial-slope comparison), showing faster, compartment-localized product build-up in the hydrophobic domains. Reproduced with permission39. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e Definition of the “red-line” boundary (loss of acceleration). Bright-field images (scale bar, 10 μm): (1) no LLPS (homogeneous), (2) stable coacervate droplets, (3) incipient aggregation, (4) solid-like aggregates. Crossing this boundary corresponds to stronger interactions and increased microviscosity/immobilization, which reduces molecular exchange and diminishes catalytic gains. Reproduced with permission41. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature.

Beyond medium reweighting, interfacial activation can turn encounter frequency into chemical work. In a coacervate/oil multiphase setting, hydrophobic Stetter partners phase-separate into organic droplets that are spontaneously sequestered by coacervates; a poly(sodium acrylate) (PAA)-rich shell forms at the droplet interface. Under these conditions, the Stetter reaction proceeds with higher conversion and enhanced 1,4-diketone selectivity compared with water or THF (tetrahydrofuran) and, critically, runs without added base. This behavior is consistent with PAA–thiazolium interactions enabling in situ carbene generation at the interface (Fig. 2b)36. Thus, coacervates act not only as passive concentrators but as active, sacrificial microreactors whose interfaces gate activation and selectivity.

In photochemical systems, complex coacervate droplets formed by tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl) porphine (TPPS) and diethylaminoethyl-dextran (DEAE-dextran) host TPPS J-aggregates that act as light-harvesting antennas. Upon visible irradiation, excited TPPS sensitizes triplet oxygen (³O₂) to singlet oxygen (¹O₂), which then oxidizes iodide (I⁻) to triiodide (I₃⁻); the droplet-driven enrichment of I⁻ and organization of TPPS into J-aggregates together promote this sequence, resulting in faster onset and improved photochemical efficiency under identical illumination conditions. In contrast, homogeneous media disperse energy and favor quenching (Fig. 2c)37. While LLPS-enabled chloroplast architectures also place energy and substrates in-phase, they tend to yield only modest, geometry-limited improvements, indicating that device constraints can cap the benefit even when the phase is favorable38.

When the goal is not just to shift the operating window but to impose directionality, pockets and energy channels placed in-phase become decisive. In DNA-templated protocells presenting switchable hydrophobic pockets, a retro-Diels–Alder reaction shows a clear bias toward the retro trajectory because pre-organization and local hydrophobicity stabilize the productive geometry. Here, proximity becomes directional, not merely frequent (Fig. 2d)39. A parallel approach involves keeping the energy channel in-phase. The J-aggregates mentioned above localize light-driven chemistry37, while photoswitchable ssDNA–peptide assemblies use light to flip a conformation from a misaligned to an aligned state, where the ON state reacts substantially faster than the OFF state40. As a baseline for co-localization with mobility, short-peptide condensates that co-partition reactants and catalysts have been shown to deliver higher product formation or faster initial rates than matched bulk solution. However, once viscosity rises or electrostatic binding becomes too tight, rates drop, cleanly exposing the limits imposed by overbinding or high viscosity (Fig. 2e)41,42,43. This behavior aligns with the compositional control of binary peptide coacervates and the utility of short-peptide synthons for creating environments where reaction outcomes can be cleanly assessed44,45.

Projecting these local advantages into higher throughput and reaction cascades requires architectural control. Metal-free hybrid coacervate nanodroplets retain coacervate-style exchange while adding a controllable shell, allowing “window shifts” or “directional bias” to manifest as higher flow or longer sequences under redox or photochemical operation46. Taken together, these examples show that coacervates, without changing molecular identity, can accelerate reactions when formulation places the system inside a productive window and retard them outside it. Pockets and in-phase photonics can then convert encounter bias into selectivity and programmable control.

Enzymatic reactions in coacervates

Relative to small-molecule systems, enzymatic catalysis in coacervates has become a major focus due to its high biomimetic relevance. The central principle is straightforward: catalytic gains are typically observed only in an intermediate regime, where enrichment increases without severely reducing mobility. When an enzyme and its substrate are co-localized in the same condensed phase and remain mobile, encounter frequencies rise and productive conformations are stabilized. However, if interactions become too strong or the phase too viscous, the benefit is lost and turnover drops. This can be observed by tuning the condensate’s composition while keeping the enzyme-substrate pair constant. For example, with β-galactosidase and its substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-galactopyranoside (4-MUG), increasing the positive charge in peptide-peptide condensates drives the system outside this intermediate regime, and the initial rate falls by approximately 40%47, consistent with overbinding or reduced mobility. In contrast, peptide-RNA condensates tend to outperform bulk solution at the same loading because both partners are included yet remain mobile48. An enzyme-built system makes this point concrete: lipase BTL2 fused to disordered scaffolds forms enzymatic condensates that run about twice as fast. This gain vanishes when phase separation is removed, because the droplets provide a slightly more basic local pH (a nano-buffering effect) that keeps the lipase in its open, active conformation (Fig. 3a)49.

a (I) Schematic comparing a homogeneous solution with a phase-separated system: co-localizing enzyme and substrate in the dense phase increases local and overall rates. (II) A representative kinetic trace shows faster product accumulation with coacervates than in bulk. Reproduced with permission49. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature. b Cascade in a coacervate-in-proteinosome hybrid (uricase → H₂O₂ → HRP (horseradish peroxidase) /Amplex Red → resorufin). The coacervate interface and the proteinosome membrane form two transport barriers in series; product must exit the droplet and cross the membrane, so overall flux is capped even if the first step is faster. Reproduced with permission50. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. c (I) Schematic of pH-triggered in situ coacervation inside a GUV (giant unilamellar vesicle) that co-localizes enzyme (E) and substrate (S) to switch a dormant reaction ON. (II) Corresponding confocal images of the same system (scale bar: 5 μm): pH 11 (OFF, no coacervates) and pH 9 (ON, coacervates); returning to high pH turns the reaction OFF again. Reproduced with permission53. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Whether these local gains translate to the system level depends on architecture, because transport across interfaces can become rate-limiting and cap the overall flux. This principle is powerfully illustrated in hybrid microcompartments where coacervate subcompartments are formed inside a semi-permeable proteinosome. In a cascade reaction, the first enzyme and its substrate are located inside the coacervate droplets, producing a diffusible intermediate that must exit the droplet and cross the proteinosome membrane to reach the second enzyme. Although the first step is approximately six times faster inside the droplet, the overall cascade is slower than in bulk. This is because the two interfaces cap the flux, making transport, not intrinsic catalysis, the rate-limiting step (Fig. 3b)50. The existence of such bottlenecks reveals a critical design principle: the performance of multicompartment systems is often not limited by the intrinsic reaction rate but by the transport resistance at the coacervate interface. Interfacial engineering is therefore as important as optimizing the in-droplet chemistry.

The solution is to engineer the boundaries. Hybrid microreactors that embed coacervate domains around the enzyme CALB keep exchange high while adding a controllable shell and surface area. Under comparable loading, they deliver two to nine times higher throughput and remain robust under harsher conditions, showing that a device-level shell can project step-level control into sustained flow51. The same design logic enables on-demand control. Light-responsive droplets can flip activity on and off within seconds52, while pH-triggered coacervation inside vesicles can activate a dormant enzyme by creating its preferred phase in situ (Fig. 3c)53. Multiphase droplets can place modules at different distances from interfaces to bias flux in reproducible ways54,55. With placement under control, regulation becomes readable in spatial patterns. In programmable multiphase coacervates, interfacial tensions are tuned so that droplets self-organize into core–shell or Janus architectures. Placing an enzyme or substrate-rich domain near an interface shortens the path to adjacent phases and speeds up the step, whereas burying it deep in the core increases retention and slows the handoff. This allows for predictable shifts in timing and flux set by spatial organization alone56. Networks of alternating binary droplets and hierarchical protocells can then wire multiple compartments so that delays and amplifications are set by interface density and path length, not just enzyme identity57,58.

Nucleic-acid catalysis in coacervates

The study of nucleic-acid catalysis inside coacervates is less about a generic, concentration-driven rate increase and more about tuning the local conditions that control whether a ribozyme/DNAzyme is active or inhibited. In practice, three factors can be tuned together: (i) the local availability of Mg²⁺ and polyamines, which support folding and catalysis; (ii) the folding and association equilibria of the nucleic acid; and (iii) hydration and crowding (water activity), which reshape both structure and kinetics. Coacervates are well suited to this task because they enrich nucleic acids while still allowing exchange with the surrounding solution, so changes in activity inside droplets can translate into measurable outcomes beyond the droplets (e.g., overall yield, product distributions, or coupled downstream reactions)59. The practical design objective is to find formulations that produce net enhancement without trapping—that is, enrichment is retained, but binding and microviscosity do not become so strong that diffusion-limited transport wipes out the benefit.

Mg²⁺ is pivotal for nucleic-acid catalysis, as it screens electrostatics to enable productive folding, coordinates in active sites to stabilize transition states, and lowers barriers in template-directed reactions. Condensates modulate these effects through local charge compensation, Donnan-driven Mg²⁺ partitioning, and solvation-biased conformational equilibria. In poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDAC)/RNA complex coacervates, template-directed RNA polymerization becomes notably less dependent on bulk free Mg²⁺, with partial rescue even under low-Mg or chelating conditions. In the same environment, multiple ribozymes and a deoxyribozyme shift from inhibited to restored or enhanced activity. This contrasts sharply with the strong-binding poly(L-lysine)/carboxymethyl dextran case, where hammerhead ribozyme rates can be approximately 60 times slower than in buffer. Switching to the looser PDAC scaffold increases the product of enrichment and mobility, flipping the sign from suppression to facilitation60. The practical message is clear: condensate composition is the primary control parameter, because it jointly sets partitioning and mobility/exchange. In practice, one must optimize partitioning together with mobility (enrichment and exchange) rather than enrichment alone.

To connect individual reactions, peptide–RNA condensates tuned to an “enriched yet mobile” window can drive ribozyme-catalyzed fragment recombination and oligonucleotide assembly toward ligation, yielding a typical 10-fold acceleration and up to 65-fold under optimized designs61. Thus, charge-mediated LLPS does more than concentrate molecules; it rebalances the thermodynamics and kinetics of reversible cleavage and ligation by shifting folding midpoints, reducing misfolding, and biasing equilibria toward products. To export these local gains to system readouts, two complementary routes have emerged. Polyanion-assisted catalysis uses polycarboxylates or polysulfates to compete away unproductive RNA-polycation contacts, delivering up to 12-fold improvements for hammerhead and hairpin ribozymes (Fig. 4a)62. Charge-density reduction broadens the active window via RNA fluidization and Mg²⁺ repartitioning, yielding several-fold to order-of-magnitude kinetic gains while avoiding the viscosity trap63. As a spatial circuit, multiphase coacervates can exploit phase-specific differences in RNA duplex stability to place folding-biased versus reaction-biased subpopulations, allowing interfaces to act as adjustable transport barriers that suppress unwanted channels64.

a Polyanion-assisted catalysis: polyanions compete off non-productive RNA-polycation contacts, restoring proper folding and enhancing ribozyme reactions in coacervates. Reproduced with permission62. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. b Transcription kinetics in lysate coacervates. (I) Kinetic scheme used for model fits; (II) time traces with fits show faster and higher mRNA accumulation in coacervates versus single-phase controls; the model indicates increased DNA-T7 RNAP association and transcription rate. Reproduced with permission65. Copyright 2013, National Academy of Sciences. c Phase-addressable localized transcription in DNA-nanostar droplets. (I) Two droplet types (D1/D2) anchor distinct templates (Temp-A/B) and reporters (Rep-A/B). (II) After a single global addition of T7 RNAP, only droplets carrying the matching template turn on in the corresponding channel (yellow=Rep-A; magenta=Rep-B), evidencing low-crosstalk, addressable activation (scale bar: 50 μm). Reproduced with permission67. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society.

Transcription and translation in coacervates

Moving up the biomimicry ladder, we now consider how encoded transcription can be programmed to occur only where it should. Membraneless coacervates offer a way to convert local kinetic gains into programmable gene expression without a membrane. In picoliter water-in-oil droplets where E. coli lysate is osmotically condensed into coacervates, crowding shifts kinetics beyond mere enrichment. The binding constant between the DNA template and T7 RNA polymerase increases by nearly two orders of magnitude, and the apparent transcription rate constant increases by about five to six-fold, turning “faster chemistry” into faster gene expression (Fig. 4b)65.

A complementary polysaccharide/polypeptide formulation sets the boundary conditions. Inside carboxymethyl dextran/poly(L-lysine) coacervates, cell-free expression of mCherry begins faster yet ends with low yield due to aggregation and adverse cationic interactions. Controls show that carboxymethyl dextran alone supports expression, whereas poly(L-lysine) specifically depresses it. This provides evidence that formulation and crowding can cap total output even as the early phase accelerates66.

From speed to placement, DNA-nanostar droplets demonstrate spatial control. Here, the DNA template is colocalized while the T7 RNA polymerase remains exchange-competent (Fig. 4c). Adding RNases to the surrounding phase converts localized transcription into sustained RNA gradients, so a downstream toehold-mediated strand-displacement reaction proceeds preferentially in and near the producing droplets. The product field mirrors where transcription actually occurs67. This sequence offers a clear design lesson: co-localize partners while keeping mobility high, tune the formulation to avoid overbinding and viscosity, and program leakage and degradation to preserve gradients, so that local gains propagate through the transcription/translation cascade into measurable system-level outputs.

State writing inside coacervate droplets

Having considered local reactivity control without persistent state changes, we now turn to cases where chemistry confined inside a coacervate does not merely modulate rates but rewrites the droplet itself. This process leaves durable, or deliberately transient, records in its material, internal layout, and timeline. “State writing” refers to reaction-driven changes that persist after inputs are removed, such as turning a liquid into a gel network, engraving long-lived internal architectures like shells or vacuoles, or programming time courses that leave a recognizable trajectory. These reaction-structure couplings provide practical design handles for coacervate-based protocell behavior.

Scaffold writing: in-droplet gelation and network formation

Polymer and crosslink networks written inside coacervates can convert freely flowing droplets into bodies with a persistent scaffold. Photochemical routes make this tangible. When polymerizable species and initiators are pre-enriched, brief irradiation stitches a network in situ. Even after illumination ceases, the interior remains semi-solid. A programmed cleavage step can later restore fluidity, confirming that the lock is chemical and reversible. Under controlled exposure, the material evolves through a readable sequence, from local stiffening to the emergence of an elastic rim and progression toward a gel-like microbody, so that the final cross-section carries a spatial imprint of where the conversion occurred (Fig. 5a)68.

a Photopolymerization-based scaffold writing. In HA/PDDA/BSA coacervates preloaded with DMAEMA and photoinitiator, local irradiation (405 nm) triggers BSA-mediated polymerization to PDMAEMA. The reaction proceeds preferentially near the interface, producing an elastic rim and ultimately a multicompartment coacervate with a persistent cross-linked shell. Reproduced with permission68. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature. b Enzyme-catalyzed crosslinking as a chemical lock. HRP and H₂O₂ couple phenolic/tyrosyl residues on polypeptides within the dense phase, converting the coacervate from a flowing liquid to a gel-like solid. Reproduced with permission70. Copyright 2025, Elsevier Inc. c Peripheral layout writing in membrane-wrapped protocells. BSA-loaded polysaccharide vesicles (P-somes) admit DEAE-dextran through the semipermeable shell. Coacervation occurs inside the lumen, nucleating multiple sub-droplets that coalesce along the inner envelope to form a persistent cortical pool. After washing away free material, the droplet-in-vesicle system retains a distinct peripheral coacervate domain whose position and morphology remain stable, illustrating boundary-directed writing. Reproduced with permission72. Copyright 2025, National Academy of Sciences. d Chemical writing of vacuolated layouts by amino acids. (I) Exogenous charged amino acids are selectively taken up; ion/acid–base pairing with protein side chains elevates local osmolyte levels and drives water influx, writing static, non-membranous vacuoles tunable by amino-acid identity and concentration. (II) In-droplet enzymatic conversion of L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid (asparaginase) produces transient vacuoles that appear and vanish with substrate, enabling erasable or cyclic layout writing. Reproduced with permission74. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature. e Ligation-written nucleus-like subdomain. (I) Schematic: in-droplet non-enzymatic ligation elongates DNA and condenses a liquid-crystalline subdomain (LC-in-ISO) as a persistent layout. (II) Confocal evidence: SYBR Gold images at t = 0 and 24 h show a brighter internal subdomain (ISO → LC-in-ISO) (scale bar: 10 μm). Reproduced with permission75. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

Cytomimetic scaffolding written by in-droplet filament assembly provides a complementary, biocompatible path to locking the internal state. In bacterially derived living-synthetic hybrids, the uptake of G-actin and ATP (adenosine triphosphate) provisioning from within drive F-actin assembly specifically in the coacervate matrix. The resulting filament mesh damps internal flows, holds the overall shape, and buttresses subcompartments such as a DNA-histone nucleus-like body and membrane-coated vacuoles. Depolymerization inputs can erase the lock and return the interior to a mobile state69. The scaffolded interiors maintain these substructures across ionic and osmotic challenges, so the material change functions as an internal means to stabilize downstream layout writing.

A third, population-level route to scaffold writing is the in-droplet gelation of classical polyion coacervates70. When linking reactions originate throughout the dense phase, the nascent networks freeze the dispersion’s material identity. Coalescence is suppressed, ripening is arrested, and the size spectrum becomes a stable, readable record of the write (Fig. 5b). Because the linking chemistry is reversible, relaxing it restores mobility and returns the droplets to a liquid baseline, providing evidence that the gel is a stored choice rather than an irreversible drift71.

Writing the layout: shells, vacuoles, and nucleus-like bodies

Beyond scaffold writing, reactions inside coacervates can also write boundary-directed features like elastic shells and membranes. In a membrane-wrapped protocell, semipermeable polysaccharide microcapsules preloaded with BSA can admit DEAE-dextran, which coacervates with the intravesicular protein. The nascent droplets merge into a cortex-like pool pinned to the inner envelope. A subsequent ATP uptake step strengthens multivalent BSA interactions, allowing the same peripheral domain to toggle between liquid and gel-like material while its membrane-affixed layout persists (Fig. 5c)72. The periphery can also be inscribed without a membrane. When coacervates are doped with photopolymerizable species, monomer and initiator enriched at the interface undergo in-droplet photopolymerization, first stitching an elastic rim and then thickening it into layered shells whose cross-sections retain the light dose and pattern68. Light-fueled protocells extend this logic by using partitioned light-responsive precursors to couple growth and boundary editing. Illumination generates coacervate-forming species to expand the droplet and then biases an interfacial conversion, yielding banded or shell-like skins whose spatial ordering maps the illumination schedule73.

Within the cavity tier of layout writing, a clear example is the vacuolation of protein-rich coacervates by charged amino acids (Fig. 5d). In this model, cationic or anionic amino acids are selectively taken up into the dense phase, where they engage in acid-base pairing and ion-pair formation with protein side chains. This leads to a local rise in small-solute osmolytes and a softening of protein-protein attractions. Water then invades these zones to create non-membranous, water-filled vacuoles that reorganize the interior. Depending on the amino acid identity and dosing, the write can resolve as static vacuoles that persist or transient ones that fade, leaving a readable cavity map tied to the recent in-droplet chemistry74.

At the level of an interior organizing center, a direct route is to grow the nucleic-acid cargo in situ. In nucleic-acid-bearing coacervate protocells, short oligonucleotides partition into the dense phase where a non-enzymatic ligation chemistry proceeds. As strands elongate, their partitioning shifts further toward the matrix and their interactions with the scaffold strengthen. The nucleic-acid pool then condenses into a stable, compositionally enriched domain that functions as a nucleus-like body. The written state is a long-lived internal subdomain that persists after the ligation window closes (Fig. 5e)75.

Writing the timeline: lifetimes, on/off switches, and cycles

Beyond material and layout changes, in-droplet chemistry can also write temporal information, turning existence, lifetime, thresholds, and periodicity into programmable variables. A natural starting point is fuel-powered autonomy. In ATP-producing active coacervates, enzymes, precursors, and product partition into the dense phase so that a single fuel pulse writes a threshold-dwell-return trajectory. Droplets grow under self-supplied ATP and then relax as the internal stock is spent. A second pulse can replay this programmed trajectory (time course), making lifetime a stored quantity rather than a continuously titrated one. Under closely related conditions, the same network can write a different trajectory where growth gives way to nucleation, causing the droplet number to rise at a comparable mean size (Fig. 6a)22. Other fuel chemistries demonstrate related replayable assembly–disassembly cycles under pulsed feeding, with catalytic RNAs remaining functional inside droplets76.

a ATP-producing active droplets. (I) Schematic: pyruvate kinase (PyK) uses phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to convert adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into adenosine triphosphate (ATP); ATP coacervates with the cationic protein K72, so a single fuel pulse writes a growth–dwell–return trajectory. (II) Data: droplet radius vs time under three stepwise PEP pulses shows replayable/rewritable growth plateaus (lifetime stored between pulses). Reproduced with permission22. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. b Dynamic covalent ON/OFF (schematic). Imine formation writes ON; a parallel aldol reaction that consumes the aldehyde writes OFF; batch/continuous/pulsed feeding tunes lifetime and enables replay. Reproduced with permission77. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Building on this notion of a stored lifetime, existence itself can be toggled with built-in erasers. In peptide-aldehyde-ketone platforms, imine formation inside coacervates switches the state on, while a colocalized aldol reaction consumes the aldehyde and turns it off. A batch feed writes a finite on-time, whereas continuous or pulsed feed can sustain or rewrite it on demand (Fig. 6b)77. Alternatively, polymerization-induced transient coacervation implements the same logic via macromolecular growth. Reactions first generate coacervate-competent chains to write the state, and continued growth or targeted consumption removes the maintaining condition, cleanly returning the system to a fluid baseline78.

To go beyond one-shot lifetimes, control parameters can extend the write to thresholds and cycles. Negative-feedback loops can place a self-limiting dissolution threshold in the internal network, so the gate level and lifetime become properties of the chemistry itself79. When the control action is periodic, redox-switchable metallosurfactant coacervates can oscillate between states under programmed redox schedules, inscribing a period that appears in size, appearance, or interfacial texture80. Temporal information can also be encoded in the stimulus pattern. Dipeptide coacervates can map the order, spacing, or frequency of inputs onto distinct outcomes like stabilization, differentiation, or dissolution, so the timing code is stored in the final phenotype81.

External readouts: from inside chemistry to outside signals

External readouts can be productively viewed as chemical signals. Reactions inside coacervates encode a signal, interfaces and media transmit it, and a receiving module decodes it as a change of state. Within this framing, membranes and shells operate as adjustable transport barriers that define channel selectivity and throughput; geometry sets the gain and delay of propagation; and the choice of carrier, such as NO (nitric oxide), ROS (reactive oxygen species), protons, or DNA fragments, determines range and specificity. The examples in this section demonstrate that the coacervate boundary is not a passive container. It is an active, designable component that transduces an internal chemical state into a specific external signal. The choice of boundary, for instance a porous MOF shell versus an erythrocyte membrane, determines not just if a signal is released, but what the signal is and who can receive it.

Readouts to synthetic cells

A chemical “readout” in a synthetic protocell consortium is only meaningful if an internal reaction changes something that a neighboring compartment can sense. In practice, this usually means altering what crosses an interface, how fast it crosses, or how long it is retained. Two designs show up repeatedly: (i) tuning interfacial permeability/selectivity and (ii) arranging compartments in space to define contact and diffusion paths. Protein-based shells can stabilize coacervates and reduce nonspecific leakage while still permitting exchange of selected species, turning otherwise “open” droplets into compartments with controlled transport behavior82. More recently, MOF nanoparticle shells assembled at the coacervate interface provide an additional handle: the intrinsically porous membrane and its surface chemistry can be used to regulate semipermeability and to localize biomolecules at the boundary, enabling protocell–protocell communication and signal processing83.

Interfacial control becomes especially clear in pairwise interactions where contact and transport determine the outcome. In a prototypical “predatory” community, coacervate droplets adhere to enzyme-loaded proteinosomes; membrane disruption at the contact region enables transfer of encapsulated macromolecular cargo into the coacervate phase, after which the cargo-loaded droplets can detach and interact with new partners84. In a related “tit-for-tat” design, a first population triggers a local pH change that dissolves a second (pH-sensitive) coacervate population that had been storing a protease. The released protease is then taken up by a third, pH-stable coacervate population associated with the initiating partner, leading to delayed membrane degradation and a clear state change in the initiator (Fig. 7a) 85. In both cases, the observable output is produced by a sequence of physical steps—adhesion, selective release/uptake, and contact-mediated chemistry—rather than by a single “signal molecule” in bulk solution.

a Synthetic-to-synthetic readout. GOx (glucose oxidase) inside a proteinosome (P) converts glucose to a diffusible intermediate (H₂O₂); the signal reaches the green trigger droplet CT and activates/releases a protease; the protease acts on the red killer droplet CK to yield the active state CK*. Reproduced with permission85. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH GmbH. b Cell-level, light-gated ROS readout. Phase-separated spiropyran droplets are taken up by cells and are OFF (gray). Visible light switches them ON (red), causing ROS generation inside cells; the ROS turn a common non-fluorescent probe (DCFH-DA) into green fluorescence and damage/kill the cancer cells. UV light resets the droplets OFF, halting ROS so cells survive. Thus, light gates the ON/OFF states, with readouts in fluorescence and cell viability. Reproduced with permission89. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH. c Bacterial interface readout. A structured polysaccharide wall excludes bacteria at baseline; dextranase degrades/reconfigures the wall, allowing selective sequestration and sterilization of E. coli. Reproduced with permission91. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. d Tissue-level readout. A concentric, three-layer “prototissue” immobilizes GOx-CVs (outer), HRP-CVs (middle), and CAT-CVs (inner) (GOx glucose oxidase, HRP horseradish peroxidase, CAT catalase, CVs coacervate vesicles). With glucose and hydroxyurea, diffusive coupling across layers produces nitric NO near the lumen; downstream, platelet activation decreases and clotting slows. Reproduced with permission93. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature.

Moving beyond pairwise contacts, spatial organization becomes a practical bottleneck because droplets in suspension drift and neighbor relationships are not stable. Several groups address this by immobilizing large numbers of functionalised droplets in hydrogels or patterned matrices, which preserves distances and defines diffusion pathways. In these formats, a readout can take the form of a spatial fluorescence pattern that reports both the local reaction chemistry and the efficiency of inter-droplet transport through the matrix86. More generally, connectivity matters: series layouts naturally introduce delays (signals must traverse successive interfaces), whereas parallel layouts increase throughput and broaden the dynamic range; layered or branched arrangements can relay species over longer distances while limiting back-action on upstream modules82,87. Interfaces can also be tuned in time—for example, transient osmotic treatments have been used to temporarily increase permeability so that a chemical pulse can pass, followed by a return to a lower-leakage, more protected state88.

Readouts to living systems

The design of living-system readouts carries particular significance for bioengineering when a pre-concentrated reaction inside the coacervate serves as the bridge, and the emitted message is one that native pathways already interpret. This bridge typically relies on small-molecule effectors like NO or ROS, or enzyme-gated payloads, with intermediates retained until release.

At the cellular scale, a representative implementation uses spiropyran-based coacervates that enrich a photo-switchable chromophore. After uptake by mammalian cells, one wavelength writes a fluorescent state for localization, while a second wavelength drives intracellular ROS generation and resets the chromophore. This yields on-demand, reversible cytotoxicity without continuous dosing. Here, the droplet concentrates the switch; ROS acts as the effector signal; and the host cell provides the receiving response through its redox-sensitive pathways (Fig. 7b)89. Beyond optical control, disease-associated endogenous cues can trigger ROS: in diabetic wounds, glucose-responsive coacervates generate ROS in situ and promote healing90. Two microbial-interface variants follow the same bridge logic with different gates. A plant-cell-inspired polysaccharide wall retains antibacterial payloads at baseline. Enzymatic incision by polysaccharide-degrading activities in the milieu releases these payloads and produces on-cue killing of E. coli (Fig. 7c)91. In bacteriogenic protocells, the coacervate concentrates nutrients and cofactors to sustain embedded bacteria while confining their secretions, jointly remodeling the droplet interior as a morphological and chemical readout of two-way exchange69.

At the tissue scale, nitric oxide offers a clear bridge from coacervate chemistry to vascular function. One design encloses glucose oxidase inside a coacervate and positions hemoglobin on an erythrocyte-membrane shell. With glucose and hydroxyurea, this spatially coupled cascade generates NO. Confocal readouts show H₂O₂ in the interior and NO-derived fluorescence at or near the shell and into the surrounding phase, indicating that the coacervate pre-concentrates intermediates while the shell acts as a catalytic and compatible interface. The receiver is the vascular system: pre-contracted aortic rings relax as NO rises, and in vivo delivery increases vascular NO. The erythrocyte shell also improves hemocompatibility and circulation relative to uncoated droplets92. A conceptually related arrangement in a tubular prototissue releases NO into a flowing lumen, where platelets decode the signals as reduced activation and diminished clot formation (Fig. 7d)93. Across these NO cases, the shared bridge is a pre-concentrated enzyme cascade, and they differ mainly in how the boundary is engineered and who decodes the signal.

Readouts to the surrounding medium

When no synthetic or living cell is the receiver, several studies point to macroscopic changes in the medium, such as phase transitions that can be felt and optical or acid-base signatures that can be seen, as accessible environmental readouts. The cleanest expression of this idea is phase-change inscription. For example, in self-immobilizing systems, internal catalysis releases cross-linkers that gel the surrounding solution in situ, pinning the droplets while recording their prior activity as a mechanical and chemical state (Fig. 8a)94. The point is not synthetic yield but legibility and persistence: transient chemistry leaves a durable material record. Recent work with polyphenol-based coacervates extends this idea to prototissue-scale assemblies, where hydrogen-bonded and coordination networks organize droplets into cohesive bodies that present macroscopically readable states, such as gel-like constructs with substrate adhesion and shape retention (Fig. 8b)16.

a Reaction-driven in situ gelation (self-immobilization): glucose oxidase inside droplets converts glucose to gluconic acid, dissolving CaCO₃ to release Ca²⁺ that crosslinks alginate; the surrounding phase gels and multiple droplets become pinned in a new network. Reproduced with permission94. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. b Materials-level readable output: coacervate prototissues are injectable and cohesive (I), can be written into stable shapes (II) and multi-component patterns (III). Reproduced with permission16. Copyright 2025, Elsevier Inc. c Field-level optical readout: an upstream input module generates a diffusible chemical signal that is transported through a paper channel to a downstream output module (I); the resulting migrating fluorescence band over distance and time (II) reports the range and longevity of the signal. Reproduced with permission86. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Beyond phase transitions, a second mode is to materialize readouts optically or as acid–base fronts. As an example of an optical field readout, modular assemblies of droplet populations can convert in-droplet chemistry into a macroscopic fluorescence pattern that evolves over distance and time (Fig. 8c) 86. In this format, an upstream “input” module generates a diffusible chemical flux that propagates to a downstream “output” module, producing a migrating fluorescence band whose position and persistence report signal range and lifetime. As an example of an acid-base front, pH changes themselves can function as the signal: in a protocell community, an initiating compartment can shift pH to dissolve a fragile partner, and the released enzyme subsequently triggers a delayed counter-action85.

Outlook

Research on in-droplet chemistry is advancing rapidly. While rate enhancement remains a useful lever, the next step is to make droplet functions designable, comparable, and usable at interfaces with biology and devices. In this review, we advance the view of coacervate droplets from passive microreactors to chemically programmable matter by mapping Input → Written State → Output across three pillars: local reactivity control, state writing, and external readouts. The operational takeaway is compact. First, co-locate reaction partners in the same phase while keeping them mobile. Second, treat interfacial transport as an explicit design variable, because mass transfer across the boundary can cap flux even when enrichment is strong. Third, use composition to tune partitioning, mobility, and interfacial tension in a controlled way. Together, these principles provide a practical route from local chemistry to internal memory and then to usable signals.

Several challenges still limit progress. When reactions speed up or slow down in droplets, it is often hard to tell why—whether the effect comes mainly from enrichment, from transport limitations, or from genuine changes in the local chemical environment. Many “written states” are also hard to keep separate: writing one feature (for example, forming a network) can unintentionally change others (such as permeability or internal organization), which complicates multi-step programs. Outputs face physical constraints as well: signals may not travel far, may not last long, and can drift as droplets age. Finally, moving beyond clean buffers to real media remains difficult, because salts, proteins, and fouling can destabilize droplets or block interfaces.

To address these issues, state writing should become multi-channel and independent. Practically, this means encoding different states onto separate, controllable properties—such as interaction strength, local solvation, or location inside the droplet—with dedicated “write” and “read” handles for each. This will reduce crosstalk and enable composing, erasing, and re-using states on demand, turning one-off demonstrations into predictable multi-step control. A shared baseline is equally important. By running the same reaction under identical conditions in three defined encounter modes (same-droplet, one-sided enrichment, and boundary contact) and scoring outcomes simply as faster/slower, immediate/delayed, or dominant/competing pathways, the field can turn scattered results into portable design rules. In addition, future studies would benefit from reporting simple, comparable metrics—for example, how strongly each reactant enriches in the droplet (partition coefficient) and reaction rates normalized by droplet volume—so that different coacervate systems can be compared more directly.

In parallel, outputs must be made device-readable. Adding a thin porous shell that converts internal changes into pH or color fronts, visible turbidity bands, or small electrical signals detectable by simple readers will move readouts beyond the microscope. This will enable automation, higher-throughput screening, and operation in real media. Finally, interfacial electric fields should be treated as a conditional input parameter. Ion partitioning at the coacervate–dilute interface can establish an electric double layer that localizes and energizes redox chemistry at the boundary, providing spatial selectivity and rapid, reagent-agnostic control without altering the bulk composition95. Operationally, this could allow spatial and temporal steering of in-droplet reactions—triggering desired steps at the boundary while suppressing side reactions.

The longer-term goal is to move beyond programming deterministic functions in single protocells and begin directing the evolution of protocell populations that exhibit emergent, collective behaviors. The tools of state writing and signaling discussed in this review are prerequisites for systems in which protocells can compete, cooperate, and adapt. Recent fuel-driven and stimulus-gated designs are beginning to provide concrete, selectable “phenotypes” for such population-level experiments—for example, dissipative regulation, stabilized multiphase architectures, programmable boundary remodeling, and quantified aging-dependent catalytic drift96,97,98,99. By providing a framework for designing protocells with programmable memory and communication, we lay the groundwork for experiments in which selection can act on protocell variants that encode distinct written states and signaling strategies. Such experiments may reveal novel collective functions, and represent an important challenge as the field transitions from engineering individual lifelike objects to cultivating evolving, lifelike systems.

References

Yin, C. et al. Engineering the spatial distribution of amphiphilic molecule within complex coacervate microdroplet via modulating charge strength of polyelectrolytes. Small Methods 8, 2301760 (2024).

Gao, N. et al. Triggerable protocell capture in nanoparticle-caged coacervate microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3855–3862 (2022).

Cook, A. B., Gonzalez, B. D. & van Hest, J. C. M. Tuning of cationic polymer functionality in complex coacervate artificial cells for optimized enzyme activity. Biomacromolecules 25, 425–435 (2023).

Le Vay, K. et al. Ribozyme activity modulates the physical properties of RNA-peptide coacervates. eLife. 12, e83543 (2023).

Majumder, S. et al. Sequence-encoded intermolecular base pairing modulates fluidity in DNA and RNA condensates. Nat. Commun. 16, 4258 (2025).

Yin, C. et al. Spontaneous emergence of lipid vesicles in a coacervate-based compartmentalized system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414372 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Phase-separating peptide coacervates with programmable material properties for universal intracellular delivery of macromolecules. Nat. Commun. 15, 10094 (2024).

Patra, S., Sharma, B. & George, S. J. Programmable coacervate droplets via reaction-coupled liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) and competitive inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 16027–16037 (2025).

Yu, J. et al. Small-molecule-based supramolecular plastics mediated by liquid-liquid phase separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204611 (2022).

Ianeselli, A. et al. Non-equilibrium conditions inside rock pores drive fission, maintenance and selection of coacervate protocells. Nat. Chem. 14, 32–39 (2022).

Slootbeek, A. D. et al. Growth, replication and division enable evolution of coacervate protocells. Chem. Commun. 58, 11183–11200 (2022).

Lu, T. et al. Endocytosis of coacervates into liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13451–13455 (2022).

Drobot, B. et al. Compartmentalised RNA catalysis in membrane-free coacervate protocells. Nat. Commun. 9, 3643 (2018).

Yim, W. et al. Polyphenol-stabilized coacervates for enzyme-triggered drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 15, 7295 (2024).

Ngocho, K. et al. Synthetic Cells from Droplet-Based Microfluidics for Biosensing and Biomedical Applications. Small 20, 2400086 (2024).

Xie, Q. et al. Polyphenol-based coacervate droplets as building blocks for protocells and prototissues. Chem. Eng. J. 520, 165905 (2025).

Kwant, A. N. et al. Sticky science: Using complex coacervate adhesives for biomedical applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 14, 2402340 (2025).

Wang, C. & Shang, L. Coacervate-based materials: fabrication, structure, and applications. Chem. Mater. 37, 4944–4962 (2025).

Harris, R., Berman, N. & Lampel, A. Coacervates as enzymatic microreactors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 54, 4183–4199 (2025).

Jacobs, M. I., Jira, E. R. & Schroeder, C. M. Understanding how coacervates drive reversible small molecule reactions to promote molecular complexity. Langmuir. 37, 14323–14335 (2021).

Smokers, I. B. A. et al. How droplets can accelerate reactions-coacervate protocells as catalytic microcompartments. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 1885–1895 (2024).

Nakashima, K. K. et al. Active coacervate droplets are protocells that grow and resist Ostwald ripening. Nat. Commun. 12, 3819 (2021).

Deng, J. & Walther, A. Programmable ATP-fueled DNA coacervates by transient liquid-liquid phase separation. Chem. 6, 3329–3343 (2020).

Wei, M., Wang, X. & Qiao, Y. Multiphase coacervates: mimicking complex cellular structures through liquid–liquid phase separation. Chem. Commun. 60, 13169–13178 (2024).

Souri, M. et al. Coacervate-based delivery systems: bridging fundamentals and applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 41513–41553 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Coacervate microdroplets as synthetic protocells for cell mimicking and signaling communications. Small Methods 7, 2300042 (2023).

Meng, H., Ji, Y. & Qiao, Y. Interfacing complex coacervates with natural cells. ChemSystemsChem. 7, e202400071 (2025).

Du, F. et al. Aqueous liquid-liquid phase separation (AqLLPS) droplet microreactors for biocatalysis. Green. Chem. 27, 8448–8466 (2025).

Lim, S. & Clark, D. S. Phase-separated biomolecular condensates for biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 42, 496–509 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Artificial receptor-mediated phototransduction toward protocellular subcompartmentalization and signaling-encoded logic gates. Sci. Adv. 9, eade5853 (2023).

Mishra, A., Patil, A. J. & Mann, S. Biocatalytic programming of protocell-embodied logic gates and circuits. Chem. 11, 102379 (2025).

Mu, W. et al. Membrane-confined liquid-liquid phase separation toward artificial organelles. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf9000 (2021).

Nebalueva, A. S. et al. Smart coacervate catalysis: robotic optimization of Knoevenagel reaction networks. Mater. Horiz. 12, 10839–10848 (2025).

Smokers, I. B. A. et al. Complex coacervation and compartmentalized conversion of prebiotically relevant metabolites. ChemSystemsChem 4, e202200004 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Selective amide bond formation in redox-active coacervate protocells. Nat. Commun. 14, 8492 (2023).

Peyraud-Vicré, K. et al. Coacervate droplets drive organocatalyzed aqueous C-C bond formation via interfacial activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 37337–37346 (2025).

Liu, Z. et al. Coacervate microdroplets incorporating J-aggregates toward photoactive membraneless protocells. Chem. Commun. 58, 2536–2539 (2022).

Shu, R. et al. Artificial chloroplast nanoarchitectonics through liquid–liquid phase separation enables recycled and enhanced photosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 27011–27019 (2025).

Liu, W. et al. Switchable hydrophobic pockets in DNA protocells enhance chemical conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7090–7094 (2023).

Wee, W. A., Sugiyama, H. & Park, S. Photoswitchable single-stranded DNA-peptide coacervate formation as a dynamic system for reaction control. iScience 24, 103455 (2021).

Reis, D. Q. et al. Catalytic peptide-based coacervates for enhanced function through structural organization and substrate specificity. Nat. Commun. 15, 9368 (2024).

Jawla, S., Samanta, M. & Haridas, V. Development of dipeptide-based liquid droplets and fibrils as enzyme-mimics. Small 21, 2503916 (2025).

Cao, S. et al. Dipeptide coacervates as artificial membraneless organelles for bioorthogonal catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 39 (2024).

Cao, S. et al. Binary peptide coacervates as an active model for biomolecular condensates. Nat. Commun. 16, 2407 (2025).

Abbas, M. et al. A short peptide synthon for liquid–liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 13, 1046–1054 (2021).

Saini, B., Singh, S. & Mukherjee, T. K. Nanocatalysis under nanoconfinement: a metal-free hybrid coacervate nanodroplet as a catalytic nanoreactor for efficient redox and photocatalytic reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 51117–51131 (2021).

Harris, R. et al. Regulation of enzymatic reactions by chemical composition of peptide biomolecular condensates. Commun. Chem. 7, 90 (2024).

Harris, R., Berman, N. & Lampel, A. Charge-mediated interactions affect enzymatic reactions in peptide condensates. ChemSystemsChem 7, e202400055 (2025).

Stoffel, F. et al. Enhancement of enzymatic activity by biomolecular condensates through pH buffering. Nat. Commun. 16, 6368 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Construction of coacervates in proteinosome hybrid microcompartments with enhanced cascade enzymatic reactions. Chem. Commun. 57, 11713–11716 (2021).

Hao, X. et al. Transforming crowded coacervates into multi-compartmental hybrid microreactors for practical enzymatic catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202502479 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. Reversible light-responsive coacervate microdroplets with rapid regulation of enzymatic reaction rate. ChemSystemsChem 3, e2100006 (2021).

Love, C. et al. Reversible pH-responsive coacervate formation in lipid vesicles activates dormant enzymatic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5950–5957 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Voit, B. & Appelhans, D. Dual-stimulus programmed multiphase separation and organization in coacervate droplets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202512266 (2025).

Wang, D. et al. Supramolecular switching of liquid-liquid phase separation for orchestrating enzyme kinetics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202422601 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Programmable spatial organization of liquid-phase condensations. Chem. 8, 784–800 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Alternating binary droplets-based protocell networks driven by heterogeneous liquid–liquid phase separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202422175 (2025).

Mason, A. F. et al. Mimicking cellular compartmentalization in a hierarchical protocell through spontaneous spatial organization. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1360–1365 (2019).

Strulson, C. A. et al. RNA catalysis through compartmentalization. Nat. Chem. 4, 941–946 (2012).

Poudyal, R. R. et al. Template-directed RNA polymerization and enhanced ribozyme catalysis inside membraneless compartments formed by coacervates. Nat. Commun. 10, 490 (2019).

Le Vay, K. et al. Enhanced ribozyme-catalyzed recombination and oligonucleotide assembly in peptide-RNA condensates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26096–26104 (2021).

Poudyal, R. R., Keating, C. D. & Bevilacqua, P. C. Polyanion-assisted ribozyme catalysis inside complex coacervates. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1243–1248 (2019).

Iglesias-Artola, J. M. et al. Charge-density reduction promotes ribozyme activity in RNA–peptide coacervates via RNA fluidization and magnesium partitioning. Nat. Chem. 14, 407–416 (2022).

Choi, S. et al. Phase-specific RNA accumulation and duplex thermodynamics in multiphase coacervate models for membraneless organelles. Nat. Chem. 14, 1110–1117 (2022).

Sokolova, E. et al. Enhanced transcription rates in membrane-free protocells formed by coacervation of cell lysate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11692–11697 (2013).

Tang, T.-Y. D. et al. In vitro gene expression within membrane-free coacervate protocells. Chem. Commun. 51, 11429–11432 (2015).

Kengmana, E. et al. Spatial control over reactions via localized transcription within membraneless DNA nanostar droplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 32942–32952 (2024).

Zhu, M. et al. Organelle-like structural evolution of coacervate droplets induced by photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 16, 1783 (2025).

Xu, C. et al. Living material assembly of bacteriogenic protocells. Nature 609, 1029–1037 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Liquid-to-gel transitions of phase-separated coacervate microdroplets enabled by endogenous enzymatic catalysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 692, 137486 (2025).

Mahendran, T. S. et al. Homotypic RNA clustering accompanies a liquid-to-solid transition inside the core of multi-component biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. 17, 1236–1246 (2025).

Mukwaya, V. et al. Adaptive ATP-induced molecular condensation in membranized protocells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2419507122 (2025).

Shi, K. et al. Light-fuelled growth dynamics and structural transition of synthetic protocells. Nat. Synth. 4, 1359–1368 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Static and transient vacuolation in protein-based coacervates induced by charged amino acids. Nat. Commun. 16, 5837 (2025).

Fraccia, T. P. & Martin, N. Non-enzymatic oligonucleotide ligation in coacervate protocells sustains compartment-content coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 2606 (2023).

Donau, C. et al. Active coacervate droplets as a model for membraneless organelles and protocells. Nat. Commun. 11, 5167 (2020).

Bal, S. et al. Catalytically active coacervates sustained out-of-equilibrium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202505296 (2025).

Sharma, S. et al. Enzymatic reaction network-driven polymerization-induced transient coacervation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202421620 (2025).

Modi, N. et al. Designing negative feedback loops in enzymatic coacervate droplets. Chem. Sci. 14, 4735–4744 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Dynamical behaviors of oscillating metallosurfactant coacervate microdroplets under redox stress. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210700 (2023).

Kubota, R., Torigoe, S. & Hamachi, I. Temporal stimulus patterns drive differentiation of a synthetic dipeptide-based coacervate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15155–15164 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Spatial organization in proteinaceous membrane-stabilized coacervate protocells. Small 15, 1902893 (2019).

Ji, Y., Lin, Y. & Qiao, Y. Interfacial assembly of biomimetic MOF-based porous membranes on coacervates to build complex protocells and prototissues. Nat. Chem. 17, 986–996 (2025).

Qiao, Y. et al. Predatory behaviour in synthetic protocell communities. Nat. Chem. 9, 110–119 (2017).

Qiao, Y. et al. Response-retaliation behavior in synthetic protocell communities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17758–17763 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Hydrogel-immobilized coacervate droplets as modular microreactor assemblies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6853–6859 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Hierarchical assembly of proteinosomes and coacervates communities into 3D protocellular networks. Small 21, e07338 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Osmotic-induced reconfiguration and activation in membranized coacervate-based protocells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10396–10403 (2023).

Kong, H. et al. Phase-separated spiropyran coacervates as dual-wavelength-switchable reactive oxygen generators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202419538 (2025).

Wang, C. et al. Glucose responsive coacervate protocells from microfluidics for diabetic wound healing. Adv. Sci. 11, 2400712 (2024).

Ji, Y., Lin, Y. & Qiao, Y. Plant cell-inspired membranization of coacervate protocells with a structured polysaccharide layer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12576–12585 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Enzyme-mediated nitric oxide production in vasoactive erythrocyte membrane-enclosed coacervate protocells. Nat. Chem. 12, 1165–1173 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Signal processing and generation of bioactive nitric oxide in a model prototissue. Nat. Commun. 13, 5254 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Self-immobilization of coacervate droplets by enzyme-mediated hydrogelation. Chem. Commun. 57, 5438–5441 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Interfacial electric fields modulate redox reactions in abiological coacervates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 27213–27218 (2025).

Jia, L. & Qiao, Y. Protocells with ATP-Fueled Dissipative Behaviors as Functional Regulators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 45004–45014 (2025).

Liu, L. et al. Radiation-responsive coacervates through controlled self-immolative demembranization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 65, e19473 (2026).

Kang, W. et al. Time-dependent catalytic activity in aging condensates. Nat. Commun. 16, 6959 (2025).

Wenisch, M. et al. Toward synthetic life—Emergence, growth, creation of offspring, decay, and rescue of fuel-dependent synthetic cells. Chem 11, 102578 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22161016), the Macau University of Science and Technology and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (Senior Researcher Fellowship). C. C. acknowledges the support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. conceived and structured the review, performed the literature survey, and wrote the manuscript. J.L. supervised the work and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Liangfei Tian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Li, J. Recent advances in coacervate protocells from passive catalysts to chemically programmable systems. Commun Chem 9, 76 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-026-01937-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-026-01937-4