Abstract

Previous studies in quantum information have recognized that specific types of noise can encode information in certain applications. However, the role of noise in quantum hypothesis testing, traditionally assumed to undermine performance, has not been thoroughly explored. Our study provides sufficient conditions for general noisy dynamics to surpass noiseless (unitary) dynamics within certain time interval. We then design and experimentally implement a noise-assisted quantum hypothesis testing protocol on ultralow-field nuclear magnetic resonance systems, which demonstrates that the success probability under certain noisy dynamics can indeed surpass the ceiling set by unitary evolution. Moreover, we show that in cases where noise initially hampers performance, strategic application of coherent controls on the system can transform those previously detrimental noises into advantageous ones. Our results, both theoretical and experimental, demonstrates the potential to leveraging noise in quantum hypothesis testing, which pushes the boundaries of quantum hypothesis testing and general quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypothesis testing is an essential statistical technology in scientific research, enabling one to distinguish various models based on observed data1. In quantum science, quantum hypothesis testing (QHT) is a commonly employed tool to ascertain the model of a given quantum system, which has profound connections with topics ranging from quantum state and dynamics discrimination2,3,4,5,6,7, parameter estimation8,9, quantum communication10,11, the detection of weak forces and magnetic fields12,13,14, quantum machine learning15, to quantum illumination16.

In noiseless scenarios, it is possible to achieve perfect hypothesis testing within a sufficient amount of time using optimal strategies17,18. However, the presence of inherent quantum noise significantly hampers this capability. To mitigate the impact of noise, various strategies, such as quantum error correction19,20,21 and optimal control22, have been proposed. Although recent studies show that some specific types of noise can be harnessed in certain quantum information applications23, it is widely accepted that the performance of noisy hypothesis testing is fundamentally limited by its noiseless limit. The potential to leverage noise in QHT is still unexplored, particularly beyond specific scenarios.

In this article, we demonstrate that the interaction between coherent evolution and noise can push the boundaries of QHT beyond unitary dynamics. We explore the full potential of noise in QHT by establishing sufficient conditions for characterizing whether noisy dynamics can surpass the success probabilities achievable under noiseless dynamics. Moreover, even when noise is initially independent and detrimental, we show that combining coherent controls with such noise can convert it into a beneficial factor, thus elevating the overall success rate in hypothesis testing. We apply our theory to discriminate quantum dynamics in spin systems under two prevalent noise models: dephasing and amplitude-damping. Our results uncover that, within specific evolution times, noisy dynamics can surpass unitary dynamics in success probability. Our findings signify a substantial advancement in the field of QHT and its related applications, including quantum dynamics discrimination and quantum metrology5,8.

Results

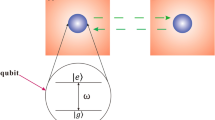

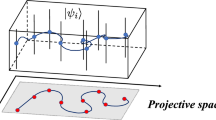

We investigate the scenario of QHT, where our objective is to distinguish between two hypotheses (h0 and h1) governed by Hamiltonians H0 and H1, respectively. These hypotheses are associated with prior probabilities q0 and q1. In a fixed initial state and evolution time, the process simplifies to the discrimination of final quantum states, as depicted in Fig 1a. Subsequently, a quantum measurement is performed on the final state, and based on the measurement result, a hypothesis is selected. The success probability of this process can be expressed as q0p(h0∣ρ0) + q1p(h1∣ρ1), where p(hj∣ρj) represents the success probability of correctly selecting the hypothesis hj given the state ρj. According to Holevo-Helstrom theorem3, the success probability, given ρ0 and ρ1, is upper-bounded by

where \({D}_{{\mathrm{tr}}\,}({\rho }_{0},{\rho }_{1})=\parallel {q}_{0}{\rho }_{0}-{q}_{1}{\rho }_{1}{\parallel }_{{\mathrm{tr}}\,}\in [0,1]\). Here \(\parallel \!\! \cdot {\parallel }_{{\mathrm{tr}}\,}\) is the trace norm that equals the sum of singular values. Without loss of generality, we will assume \({q}_{0}={q}_{1}=\frac{1}{2}\). To effectively discriminate dynamics, one can optimize the initial state, control strategies, and measurements to increase \({D}_{{\mathrm{tr}}\,}({\rho }_{0},{\rho }_{1})\), thereby improving QHT performance.

a Binary hypothesis testing process for dynamics discrimination. The binary hypotheses are H0 and H1 with respective prior probabilities q0 and q1. A known initial state evolves under hypothesis Hamiltonian H0 (or H1) to the final state ρ0 (or ρ1). Quantum measurement M is performed to decide one of the hypotheses. The coherent control strategy and noise engineering technology are considered as resources to enhance the effectiveness of decision-making. b, c Depict scenarios in which the two to-be-distinguished dynamics are influenced by Hamiltonian-independent noise and Hamiltonian-dependent noise, respectively. While Hamiltonian-independent noise can decrease the trace distance of the final states, i.e., \({D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{\,{\mbox{noise}}\,} < {D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{\,{\mbox{uni}}\,}\), thereby reducing the success probability, Hamiltonian-dependent noise has the inherent potential of increasing the trace distance, such that \({D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{\,{\mbox{noise}}\,} > {D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{\,{\mbox{uni}}\,}\), and thus enhancing the success probability.

In the absence of noise, the evolution is given by \(\dot{\rho }=-i[{H}_{j},\rho ]\). In this case the optimal initial state for discrimination is \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle +\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\), a superposition of the eigenstates of H1 − H0 corresponding to the largest and smallest eigenvalues17,18. With this optimal strategy, the success probability increases at a rate of \(\frac{{\lambda }_{\max }-{\lambda }_{\min }}{4}\), and perfect discrimination can be achieved over sufficient time17,18. However, when the noises are taken into consideration, the problem becomes much more complicated and the optimal strategies are generally unknown. For Markovian noises, the dynamics can be described by24

where Lk are the Lindblad operators that describe the noisy effects and {x, y} = xy + yx denotes an anticommutator. In the standard framework, it is generally assumed that the Lindblad operators, {Lk}, are independent of the Hamiltonian Hj19,20,25,26. Under these assumptions, common wisdom holds that noise always hampers the discrimination as it homogeneously affects both hypotheses, reducing the success rate without aiding differentiation27.

The assumption that noises are independent of the system’s Hamiltonian does not always hold true in quantum systems. For instance, consider the decay process from a higher energy state \(\vert e\rangle \) to a lower one \(\vert g\rangle \). In this case, the corresponding Lindblad operator is proportional to \(\vert g\rangle \langle e\vert \), reflecting an inherent dependence on the energy levels governed by the Hamiltonian. Therefore, the decay process is intrinsically correlated with the Hamiltonian. Similarly, dephasing noise, another common type of noise, often relies on the energy eigenstates because it generally affects the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix in the energy eigenstate basis. Thus when H0 and H1 do not commute, [H0, H1] ≠ 0, the noise operators can differ due to their reliance on distinct eigenstates. Even if H0 and H1 initially commute and share the same eigenstates, introducing a control Hamiltonian, Hc, can alter this situation. By ensuring that [H0 + Hc, H1 + Hc] ≠ 0, the eigenstates of the combined Hamiltonians will become different. It’s important to note that this control mechanism is applied solely to the system, without affecting the environmental conditions, thereby illustrating how the interplay between the system’s Hamiltonian and noise processes can be manipulated and potentially break the independence assumption.

In general, the noisy dynamics can be described as

where {Ljk} are the Lindblad operators under the Hamiltonian Hj, which can be correlated with Hj and different for j = 0, 1. In such a scenario, the noise may increase the success probability of QHT as illustrated in Fig. 1. The success probabilities for discrimination under unitary and noisy dynamics are given by \({p}_{\,{\mbox{succ}}}^{unitary}=\frac{1+{D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{{\mbox{uni}}\,}}{2}\) and \({p}_{\,{\mbox{succ}}}^{noise}=\frac{1+{D}_{{{\rm{tr}}}}^{{\mbox{noise}}\,}}{2}\), respectively. To theoretically demonstrate the specific conditions under which noise can positively influence QHT, we introduce a general criterion based on comparing the increasing rates of success probability. In particular, we show that with the same probe state, \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle +\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\), the increasing rate of the success probability under the noisy dynamics, \({\dot{p}}_{\,{\mbox{succ}}\,}^{noise}\), can be higher than that of the unitary dynamics, \({\dot{p}}_{\,{\mbox{succ}}\,}^{unitary}\), for a period of time when either of the conditions holds (see Supplementary Note 1 for derivation),

here \({x}_{1}=\left\langle {\lambda }_{\max }\right\vert {N}_{1}-{N}_{0}\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle \), \({y}_{1}=Re\left\langle {\lambda }_{\max }\right\vert {N}_{1}-{N}_{0}\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle \), \({z}_{1}=Im\left\langle {\lambda }_{\max }\right\vert {N}_{1}-{N}_{0}\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle \) and \({w}_{1}=\left\langle {\lambda }_{\min }\right\vert {N}_{1}-{N}_{0}\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle \), \({N}_{j}={\sum }_{k}[{L}_{jk}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {L}_{jk}^{{\dagger} }-\frac{1}{2}\{{L}_{jk}^{{\dagger} }{L}_{jk},\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert \}]\) for j = 0, 1. These conditions are determined by the Lindblad operators and the maximal and minimal eigenvectors of H1 − H0, which can be directly verified. Specifically, Hamiltonian-independent noises, where the noisy part (the summation terms involving Ljk in Eq. (3) is the same for j = 0, 1, indicate that the noises affect each Hamiltonian identically). This encompasses scenarios where Lindblad operators are independent of the Hamiltonian. In these cases, none of the conditions specified in Eq. (4) are satisfied, demonstrating that such types of noises hamper the discrimination. Since \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle +\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\) is optimal under the unitary dynamics, the noisy dynamics that satisfy either of the conditions can thus achieve a higher success probability than the maximal success probability of the unitary dynamics within certain time period. We note that for noisy dynamics, \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle +\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\) might not be optimal, further optimization of the initial probe state for the noisy dynamics might yield even better results.

In our experiment, we examine a spin interacting with magnetic fields in different directions, subject to dephasing and amplitude damping noises. The dephasing noise, which can arise from the fluctuation of the magnetic field, is described by the Lindblad operator \({L}_{j1}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{1}}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}\), where κ1 is the dephasing rate, \({\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}={\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\) with \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}\) represents the direction of the magnetic fields. The amplitude damping noise can be described by the Lindblad operator \({L}_{j2}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}p}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}^{-}\) and \({L}_{j3}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}\left(1-p\right)}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}^{+}\), where \({\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}^{-}=\vert {g}_{j}\rangle \langle {e}_{j}\vert \) is the lowering operator, \({\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}^{+}=\vert {e}_{j}\rangle \langle {g}_{j}\vert \) is the raising operator, \(\vert {g}_{j}\rangle \) and \(\vert {e}_{j}\rangle \) are the ground and the excited state of \({H}_{j}={\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\). The dynamics can thus be written as

p ∈ [0, 1] represents the ground state population of the steady state, and in our experiment, p ≈ 0.5. Here, the noises are correlated with the Hamiltonian. For example, when the magnetic field is in the xz-plane with \(\overrightarrow{{n}_{j}}=(\cos {\theta }_{j},0,\sin {\theta }_{j})\) and θj ∈ [0, π), the ground and excited state of Hj are \(\vert {g}_{j}\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2-2\sin {\theta }_{j}}}\left(\begin{array}{c}\cos {\theta }_{j}\\ 1-\sin {\theta }_{j}\end{array}\right)\), \(\vert {e}_{j}\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2+2\sin {\theta }_{j}}}\left(\begin{array}{c}\cos {\theta }_{j}\\ -(1+\sin {\theta }_{j})\end{array}\right)\), the Lindblad operators, \(\sqrt{{\kappa }_{1}}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}\), \(\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}p}\vert {g}_{j}\rangle \langle {e}_{j}\vert \) and \(\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}(1-p)}\vert {e}_{j}\rangle \langle {g}_{j}\vert \), also depend on \(\overrightarrow{{n}_{j}}\), which makes them correlated with the Hamiltonian. Consequently, when θ0 ≠ θ1, the Lindblad operators differ for j = 0, 1. In nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), these noisy effects are typically characterized by the longitudinal (transverse) relaxation time, T1(T2), here \({T}_{1}=\frac{1}{{\kappa }_{2}}\) and \({T}_{2}=\frac{2}{4{\kappa }_{1}+{\kappa }_{2}}\). We emphasize that when θ0 = θ1 or T1 = T2, the noisy part of the master equation, encompassing all terms with κ1 and κ2 coefficients in Eq. (5) that influence the state ρ through dephasing and amplitude damping processes, is identical for j = 0, 1. Consequently, the noises become identical under these conditions. In Supplementary Note 3, we show that for the discrimination of two misaligned magnetic fields (θ0 ≠ θ1), as long as T1 ≠ T2, the second condition in Eq. (4) is satisfied, and the success probability under noisy dynamics can exceed the limit of the unitary dynamics. We also consider a general initial probe state, \(a\left\vert {\lambda }_{\max }\right\rangle +b\left\vert {\lambda }_{\min }\right\rangle \), providing sufficient conditions for surpassing the unitary limit. Of practical interest, we also specify the condition for an experimentally convenient initial state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \).

Enhanced QHT via noise

We perform the experimental demonstration on nuclear spins using ultralow-field NMR, focusing on a two-level system represented by an uncoupled proton in 13C-formic acid (H13COOH, where the hydroxyl proton undergoes fast chemical exchange decoupling it effectively from other spin in the molecule). Proton spins were polarized by a 1.3-T Halbach magnet and then transferred to a shielded zone where they experienced magnetic fields H0 or H1, as depicted in Fig. 2a. A guiding field was used during shuttling and discontinued upon arrival at the target region. The proton’s NMR signal under H0/H1 and noise was detected with high sensitivity (~13 fT Hz−1/2 along z in Fig. 2b) by a 87Rb magnetometer, optically pumped and probed by laser beams. Experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Notes 6 and 7.

a The proton spins in formic acid are contained in a 5 mm NMR tube and pneumatically shuttled between a 1.3-T prepolarizing magnet and a rubidium vapor cell. A magnetic shield isolates the hypothesis testing zone from the external Earth’s magnetic field. A guiding field is applied in the z direction. The proton NMR signal is measured with 87Rb magnetometer. b Magnetic noise of 87Rb magnetometer. The noise floor is about 13 fT Hz−1/2. c Time sequence of quantum hypothesis testing.

The experimental hypothesis testing process consists of three main stages (Fig. 2c): preparing the probe state, evolving it under the magnetic fields to be distinguished, and measuring the trace distance. The proton spins begin in a high-temperature approximated initial state, \({\rho }_{{{\rm{ini}}}}=\frac{{\mathbb{1}}}{2}+\epsilon \frac{{\sigma }_{z}}{2}\), where \({\mathbb{1}}\) is the identity matrix and ϵ ≈ 10−6 represents polarization. For simplicity, we set ϵ=1 as it only scales the signal amplitude. Subsequently, the initial state evolves under either \({B}_{0}{\overrightarrow{n}}_{0}\) or \({B}_{1}{\overrightarrow{n}}_{1}\), with field directions given by \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}=(\cos {\theta }_{j},0,\sin {\theta }_{j})\). The evolved density matrix, ρj(t), can be written as \(\frac{{\mathbb{1}}+{\overrightarrow{M}}_{j}(t)\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }}{2}\), where \({\overrightarrow{M}}_{j}(t)\) denotes the time-dependent proton-spin magnetization vector. The evolved proton spins’ NMR signal is detected using a 87Rb atomic magnetometer. Quantum state tomography28 is employed to measure the three components of \(\overrightarrow{M}\), thus obtaining full information about final states ρ0(t) and ρ1(t). The success probability for discriminating these states is calculated using Eq. (1).

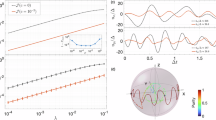

To investigate the impact of noises on the success probability, we conducted experiments with varying relaxation times that are simulated through the gradient field. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 3, where the red diamond, blue square, and green triangle represent T2 values of 5.4 s, 1.0 s, and 0.6 s, respectively, while T1 remains constant at 5.5 s. When T2 = 5.4 s ≈ T1, the success probability of discriminating between the two magnetic fields falls below the limit of unitary dynamics (as described in the Supplementary Note 3). This occurs because the decay rates of the nuclear-spin magnetization vectors in all directions become equal when T1 is approximately equal to T2. In this case, the noises become independent of the magnetic fields. On the other hand, when T1 is not close to T2, indicating that the noises are dependent on the direction of the magnetic fields, the success probability exceeds the limit of unitary dynamics. This is shown as the green and blue regimes in Fig. 3. As the encoding time increases, the improvement in the success probability initially rises, reaches a maximum, and then decreases. Note that excessively prolonged encoding times are not beneficial as the spin-decoherence effect starts to destroy the quantum states. Therefore, selecting an appropriate encoding time based on the noise environment is crucial to improving the accuracy of discriminating between the two Hamiltonians.

The success probability for discriminating two magnetic fields with different directions versus the encoding time t. The magnetic field strength are B0 = B1 = 1.86 nT, with θ0 = 75∘ and θ1 = 30∘. The black dashed line denotes the maximum success probability that can be achieved under the unitary dynamics. The brown dashed line represents T2 = 2T1. The solid lines are theoretical simulations, while triangles, squares, and diamonds are experimental data under different noisy strengths. The error bars are obtained from eight repeated experiments. In the subfigure, the maximal enhancement η is plotted as a function of \({\log }_{10}({T}_{1}/{T}_{2})\).

To quantify the enhancement effect, we define \(\eta =\max \{{p}_{{{\rm{succ1}}}}-{p}_{{{\rm{succ2}}}}\}\), where psucc1 and psucc2 are the success probabilities with and without noise. The inset in Fig. 3 plots theoretical η against T1/T2. As T1/T2 increases, η grows, indicating a higher improvement in success probability due to noise. At the extreme limit of T1/T2 → ∞, strong dephasing causes convergence to steady states defined by the dephasing dynamics. In the strong dephasing limit, the discrimination success probability is \({p}_{{{\rm{succ}}}}=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}| \sin ({\theta }_{0}-{\theta }_{1})| \), with a theoretical η of up to ≈17.7%, solely determined by the magnetic field angle difference. It is noteworthy that the inset in Fig. 3 illustrates, for finite values of T1/T2, maximum enhancement η increases as T1 decreases.

Control-assisted QHT

In scenarios where noises are initially independent of the Hamiltonian thus detrimental, it is still possible to achieve a higher success probability by leveraging the cooperation between proper coherent controls and noises. Consider a scenario where two magnetic fields are aligned along the same direction (the z-axis) but with different magnitudes. Without coherent controls, the Lindblad operators of the dephasing and amplitude damping noises are given by \({L}_{1}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{1}}{\sigma }_{z},\,{L}_{2}={L}_{3}^{{\dagger} }=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}}{\sigma }^{-}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}}\left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 1\right\vert \), which are independent of the Hamiltonian. Consequently, noises can only adversely affect the success probability. However, by introducing a well-designed coherent control, we can transform the noisy operators making them correlated with the Hamiltonian. To illustrate this, we incorporate a control field, Bc, along the x-direction. The total Hamiltonian then becomes

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio of the proton. Note that without the control field, the ground and excited states of Hj are \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \) and \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle \), which are independent of Bj, while with the control field, the ground and excited states of Hj change to \(\vert {g}_{j}\rangle =-\sin \frac{{\theta }_{j}}{2}\vert 1\rangle +\cos \frac{{\theta }_{j}}{2}\vert 0\rangle \) and \(\vert {e}_{j}\rangle =\cos \frac{{\theta }_{j}}{2}\vert 1\rangle +\sin \frac{{\theta }_{j}}{2}\vert 0\rangle \), here \({\theta }_{j}=\arctan \frac{{B}_{c}}{{B}_{j}}\). In this case the amplitude damping noise, \({L}_{j2}={L}_{j3}^{{\dagger} }=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{2}}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}^{-}\), and the dephasing noise, \({L}_{j1}=\sqrt{{\kappa }_{1}}{\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}\) with \({\sigma }_{{\overrightarrow{n}}_{j}}=\frac{{B}_{j}{\sigma }_{z}+{B}_{c}{\sigma }_{x}}{\sqrt{{B}_{j}^{2}+{B}_{c}^{2}}}\), are now correlated with Hj.

The success probabilities with the interplay between coherent control and noise are plotted in Fig. 4, where the two magnetic fields along the z-direction are taken as B0 = 0.20 nT, B1 = 2.79 nT, and the control field is taken as Bc = 0.75 nT. The initial state is along x-axis. Without Bc, both amplitude damping and dephasing noises degrade the success probability (gray dashed line). However, when applying the control field Bc, the success rate can notably improve (blue and green lines), surpassing the unitary dynamics’ maximum value within specific time intervals. It is important to note that the control field does not universally convert noise into a beneficial resource. For example, when T1 ≈ T2 (as indicated by the red line), the unitary limit cannot be exceeded even with a control field. The inset of Fig. 4 presents the maximal enhancement η achieved with varying control fields. As the magnitude of the control field increases, the enhancement initially improves but eventually starts to decline. This suggests the existence of an optimal control field that yields the highest possible enhancement. This exemplary case of QHT demonstrates that synergy of the control field and noise can lead to a boost in success probability. In the supplementary Note 5, we further demonstrate that the interaction between coherent evolution and noise can positively impact the quantum Chernoff bound, which serves as a measure of the asymptotic minimum error probability in distinguishing between two hypotheses, H0 and H1, when an ensemble of state copies, ρ0(t)⊗n, and ρ1(t)⊗n, is at the disposal.

The experiment for the discrimination of two magnetic fields along z-direction with B0 = 0.2 nT, B1 = 2.79 nT, a coherent control along x-direction with Bc = 0.75 nT is added. The black dashed line represents the simulated result under the unitary dynamics. The brown dashed line denotes T2 = 2T1. The gray dashed line represents the simulated result without Bc under the noisy dynamics with T2 = 1.0 s. The solid line is the theoretical simulation with Bc under the noisy dynamics, and the experimental data are represented with triangles, squares and diamonds for different noisy strengths. The error bars are obtained from eight repeated experiments. The longitudinal relaxation time T1 = 7.4 s. The inset displays the dependence of the maximum enhancement on the control field Bc.

Discussion

The enhanced QHT scheme could be used in the field of fundamental physics research, particularly for hypothesis testing tasks that require completion within a short time frame, owing to short-lived interactions. One specific area where this approach is valuable is in the detection of hypothetical particles beyond the Standard Model29, such as topological defect dark matter30 and bursts of exotic low-mass fields generated by cataclysmic astrophysical events31. These exotic particle-crossing events are predicted to be transient, with durations notably shorter than the T2 of the spin. Moreover, the enhanced scheme can be effectively employed in other quantum systems including NV-center32 and superconducting systems33.

In conclusion, our study pioneers the use of noise to enhance QHT in spin systems. We show that exploiting the dependence of noise on the Hamiltonian can boost success probability. When noise is detrimental, we demonstrate that cooperation with coherent controls can turn it into a beneficial resource. Further enhancements may be unlocked by exploring advanced strategies such as optimal quantum control34 and quantum error correction21. Optimal control algorithms can optimize pulse designs for improved discrimination, while error correction can selectively suppress independent noises to increase T1/T2 ratios. Our work deepens understanding of noise’s role in quantum systems and its potential to improve performance in quantum information processing tasks.

Methods

Sample preparation

We select an uncoupled proton of liquid formic acid as the two-level system. Approximately 200 μL of formic acid sample undergoes five freeze-pump-thaw cycles to eliminate any dissolved oxygen. Subsequently, the sample is vacuum-sealed in a standard 5-mm NMR tube using flame-sealing.

Experimental apparatus

We perform the noise-enhanced scheme with an ultralow-field NMR setup incorporating an Rb-atomic magnetometer, as shown in Fig. 2. The sample undergoes initial polarization within the permanent Halbach magnet, which generates a magnetic field of ~1.3 T. Subsequently, the NMR tube is pneumatically shuttled to a location just above the Rb vapor cell. During the shuttling process, the solenoid wrapped around the shutting tube creates a guiding field (≈10−4 T) aligned with the transfer direction and is abruptly switched off once the sample reaches the target position. A set of field coils is utilized to provide a to-be-discriminated magnetic field (B0 or B1). The gradient coils, a set of anti-Helmholtz coils, are employed to apply additional dephasing noise. The oscillating NMR signal is detected using an atomic magnetometer, which consists of a rubidium-87 (87Rb) vapor cell with 700 torr of N2 buffer gas14. Rb atoms are optically pumped using a circularly polarized laser in the x direction, tuned to the center of the D1 line. The NMR signal is measured via optical Faraday rotation of a linearly polarized probe laser propagating along the y direction, detuned from the D2 transition by 100 GHz. The vapor cell is housed in a five-layer mu-metal magnetic shield. The magnetometer is primarily sensitive to z-direction fields with a noise floor of 13 fT Hz−1/2. For quantum state tomography, three-orthogonal, low-inductance Helmholtz coils apply DC magnetic pulses, converting the undetectable magnetization into the observable z direction.

Noisy dynamics

The dynamics of a two-level system subjected to an external magnetic field B in the XZ-plane, in the presence of dephasing and amplitude damping, can be described by the master equation24:

Here \({\sigma }_{\overrightarrow{n}}=\overrightarrow{n}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\), where \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }=\left({\sigma }_{x},{\sigma }_{y},{\sigma }_{z}\right)\) are the Pauli matrices, and magnetic fields are along the directions \(\overrightarrow{n}=\left(\cos \theta ,0,\sin \theta \right)\). \({\sigma }_{\overrightarrow{n}}^{+}=\vert e\rangle \langle g\vert \) is the raising operator and \({\sigma }_{\overrightarrow{n}}^{-}=\vert g\rangle \langle e\vert \) is the lowering operator where \(\vert g\rangle \) and \(\vert e\rangle \) are the ground and the excited state of the Hamiltonian respectively, p ∈ [0, 1] represents the ground state population rate of the steady state. If the magnetic field is along the z-axis, \(\left\vert g\right\rangle =\left\vert 0\right\rangle \) and \(\left\vert e\right\rangle =\left\vert 1\right\rangle \). When the magnetic field is along a general direction where \(\sin \theta \ne 1\), the ground and excited state are given by \(\vert {g}_{j}\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2-2\sin {\theta }_{j}}}\left(\begin{array}{c}\cos {\theta }_{j}\\ 1-\sin {\theta }_{j}\end{array}\right)\), \(\vert {e}_{j}\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2+2\sin {\theta }_{j}}}\left(\begin{array}{c}\cos {\theta }_{j}\\ -(1+\sin {\theta }_{j})\end{array}\right)\). The raising and lowering operators are then given by

For two-level systems, it is common to describe the dynamics using the Bloch equations, which can be obtained by writing ρ(t) with the Bloch vector \(\overrightarrow{M}(t)\) as

here Mx, My, Mz are the x, y, z components of \(\overrightarrow{M}(t)\) respectively. By substituting Eqs. (8) and (9) into Eq. (7), we then obtain the Bloch equation as

If the magnetic field is along the x-axis, i.e., \({\sigma }_{\overrightarrow{n}}={\sigma }_{x}\), then

in this case the Bloch equation becomes

Thus we have

This provides the correspondence between the relaxation parameters T1,2 in the Bloch equation and the dissipation rate κ1,2 in the Lindblad equation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes for numerical simulation and data processing are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Gaillard, M. K., Grannis, P. D. & Sciulli, F. J. The standard model of particle physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S96–S111 (1999).

Holevo, A. S. Statistical decision theory for quantum systems. J. Multivar. Anal. 3, 337–394 (1973).

Helstrom, C. W. & Helstrom, C. W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory vol. 84 (Academic Press New York, 1976).

Yuen, H., Kennedy, R. & Lax, M. Optimum testing of multiple hypotheses in quantum detection theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 21, 125–134 (1975).

Chiribella, G., D’Ariano, G. M. & Perinotti, P. Memory effects in quantum channel discrimination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 180501 (2008).

Tsang, M. Continuous quantum hypothesis testing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 170502 (2012).

Hayashi, M. Error exponent in asymmetric quantum hypothesis testing and its application to classical-quantum channel coding. Phys. Rev. A 76, 062301 (2007).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Escher, B. M., de Matos Filho, R. L. & Davidovich, L. General framework for estimating the ultimate precision limit in noisy quantum-enhanced metrology. Nat. Phys. 7, 406–411 (2011).

Tsang, M., Nair, R. & Lu, X.-M. Quantum theory of superresolution for two incoherent optical point sources. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031033 (2016).

Wang, L. & Renner, R. One-shot classical-quantum capacity and hypothesis testing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 200501 (2012).

Caves, C. M., Thorne, K. S., Drever, R. W. P., Sandberg, V. D. & Zimmermann, M. On the measurement of a weak classical force coupled to a quantum-mechanical oscillator. I. Issues of principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 341–392 (1980).

Schnabel, R., Mavalvala, N., McClelland, D. E. & Lam, P. K. Quantum metrology for gravitational wave astronomy. Nat. Commun. 1, 121 (2010).

Budker, D. & Romalis, M. Optical magnetometry. Nat. Phys. 3, 227–234 (2007).

Weber, M., Liu, N., Li, B., Zhang, C. & Zhao, Z. Optimal provable robustness of quantum classification via quantum hypothesis testing. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 76 (2021).

Wilde, M. M., Tomamichel, M., Lloyd, S. & Berta, M. Gaussian hypothesis testing and quantum illumination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 120501 (2017).

Childs, A. M., Preskill, J. & Renes, J. Quantum information and precision measurement. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 155–176 (2000).

Aharonov, Y., Massar, S. & Popescu, S. Measuring energy, estimating Hamiltonians, and the time-energy uncertainty relation. Phys. Rev. A 66, 052107 (2002).

Zhou, S., Zhang, M., Preskill, J. & Jiang, L. Achieving the Heisenberg limit in quantum metrology using quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 9, 78 (2018).

Dür, W., Skotiniotis, M., Fröwis, F. & Kraus, B. Improved quantum metrology using quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 080801 (2014).

Chen, Y. & Yuan, H. Zero-error quantum hypothesis testing in finite time with quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A 100, 022336 (2019).

Basilewitsch, D., Yuan, H. & Koch, C. P. Optimally controlled quantum discrimination and estimation. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033396 (2020).

Kukita, S., Matsuzaki, Y. & Kondo, Y. Heisenberg-limited quantum metrology using collective dephasing. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 064026 (2021).

Breuer, H.-P. & Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems (Oxford University Press on Demand, 2002).

Bharti, K. et al. Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 015004 (2022).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Chen, Y., Miao, Z. & Yuan, H. Cooperation between coherent control and noises in quantum metrology. Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2200165 (2023).

Jiang, M. et al. Experimental benchmarking of quantum control in zero-field nuclear magnetic resonance. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar6327 (2018).

Jiang, M., Su, H., Garcon, A., Peng, X. & Budker, D. Search for axion-like dark matter with spin-based amplifiers. Nat. Phys. 17, 1402–1407 (2021).

Afach, S. et al. Search for topological defect dark matter with a global network of optical magnetometers. Nat. Phys. 17, 1396–1401 (2021).

Dailey, C. et al. Quantum sensor networks as exotic field telescopes for multi-messenger astronomy. Nat. Astron. 5, 150–158 (2021).

Chen, M. et al. Quantum metrology with single spins in diamond under ambient conditions. Natl Sci. Rev. 5, 346–355 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Quantum-enhanced radiometry via approximate quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3214 (2022).

Werschnik, J. & Gross, E. Quantum optimal control theory. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 40, R175 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. T2388102, 11927811, 12150014, 12274395, 12261160569, 92476204), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0303205), Youth Innovation Promotion Association (Grant No. 2023474), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (Grants No. 14307420, 14308019, 14309022), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2023ZD0300600), and the Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (Grant No. GDZX2303007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J., H.Y., and X.P. conceived the project. H.Y. and L.W. conceived the relevant theoretical constructs. Q.L. performed the measurements and analyzed the data. Z.W. assisted with the experiment and analysis. All authors contributed to analyzing the data, discussing the results, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Wang, L., Jiang, M. et al. Enhanced quantum hypothesis testing via the interplay between coherent evolution and noises. Commun Phys 8, 19 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01923-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01923-z