Abstract

Understanding the performance of perovskite solar cells is critical for advancing sustainable energy solutions. Hot-drop casted quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites (RPPs) exhibit remarkable efficiency and stability, making them promising for commercial applications. However, the ultrafast energy transfer and exciton-phonon interactions in these materials remain unclear. Here, we show that using advanced techniques like two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy (2DES) and transient grating (TG), we can unravel energy dynamics in hot-drop casted RPP films. Our study reveals rapid energy transfer between perovskite layers occurring within 100–220 femtoseconds and highlights how exciton-phonon coupling drives structural changes in the material. Coherent vibrational signals identify key lattice and organic cation modes, providing insights into their role in energy dissipation. These findings deepen our understanding of how 2D perovskites work and pave the way for improving the efficiency and stability of next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rise of perovskite-based solar cells in the photovoltaic sector is driven by their exceptional energy efficiency and reduced manufacturing costs relative to standard solar cell technologies1,2. Among the wide variety of perovskite materials available, quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites (RPPs) have gathered considerable interest for their unique structural and functional properties3,4,5,6,7,8. These quasi-2D RPPs are characterized by a distinctive layered structure, where multiple layers of perovskite are alternated with organic spacer cations. Structurally, these materials can be described using the formula R2An−1PbnX3n+1, where R represents long-chain ammonium ligands (e.g., n-butylammonium, BA+, or phenethylammonium, PEA+), A is a short-chain ammonium cation (e.g., methylammonium, MA+), and X is a halide anion (Cl−, Br−, I−)9. The RPP structure consists of ‘n’ layers of 2D [PbX6]4− octahedral sheets, which are separated by monolayers of organic cations denoted by R+. This arrangement forms a unique quantum-well structure that arises from both quantum and dielectric confinement effects. These quantum-well structures in RPPs are responsible for their enhanced stability and the ability to fine-tune their optical properties, such as band gap and emission characteristics10. Additionally, the layered architecture of quasi-2D RPPs inherently reduces ion migration, a common issue in perovskite materials that can lead to degradation over time. These features collectively make quasi-2D RRPs highly attractive for developing stable and efficient perovskite solar cells, presenting a significant advancement in the pursuit of reliable and high-performing photovoltaic technologies.

The methods used to prepare perovskite films significantly influence film morphology and device performance11,12,13,14,15. Traditional room-temperature spin-coating for 2D-perovskite films often results in randomly oriented crystals, hindering efficient charge transport and leading to poor device performance. To address this, Tsai et al. introduced a hot-casting spin-coating technique, where the substrate is preheated before spin-coating, producing highly oriented films, and achieving a PCE of ~12%5. However, this method’s sensitivity to human error makes precise temperature control challenging, affecting reproducibility. Alternatively, Zuo et al. developed a scalable, spin-coating-free hot drop-cast method that self-assembles into uniform, highly oriented films, yielding devices with up to 16% PCE16. Zheng et al. discovered that in these hot drop-casted films, small-n RPPs are sandwiched between large-n RPP layers, enhancing exciton funneling toward film surfaces for efficient charge collection12. This structure, along with energy funneling dynamics studied via transient luminescence and absorption, offers valuable insights for optimizing quasi-2D RPP-based optoelectronic devices. Although these studies reveal a general shift in signal amplitude toward higher-n RPPs, they do not offer a detailed, spectrally resolved view of the ultrafast transitions occurring between individual RPPs. This limitation highlights the need for more in-depth investigations into the energy transfer processes within quasi-2D RRP films. Understanding these mechanisms, particularly how energy is transferred within different layers, is crucial for further enhancing the efficiency of 2D layered RRP-based solar cells.

Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy (2DES) is a prominent nonlinear optical technique that correlates excitation and probing frequencies to uncover the connectivity between different electronic transitions, thereby revealing excitonic coupling17,18,19,20. The 2DES technique is especially powerful in mitigating inhomogeneous broadening effects, which allows for a more precise examination of dynamic processes in light-harvesting systems as well as advanced materials21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. This technique has been employed in the study of perovskite materials to explore ultrafast phenomena, including the dissociation of excitons into free charge carriers and the subsequent thermal distribution of these carriers30,31,32,33,34,35. Proppe et al. utilized 2DES to reveal exciton energy transfer between strongly and weakly confined perovskite quantum wells within 150 fs in spin-casted RPP films, offering valuable insights into perovskite material behavior36. Additionally, this work also reported that charge transfer happens on the timescale of 1–100 ps. On the other hand, Shang et al. reported a timescale of <500 fs in (PEA)2(MA)n+1Pbnl3n+1 films (n = 3 and 5) via TA spectroscopy, which they assigned to efficient electron transfer between the small n (n ≤ 3) perovskite phases37. There have been many recent reports suggesting that energy transfer in quasi-2D perovskite materials occurs on a timescale of 2–300 ps from small-n to large-n RPP phases38,39.

In this study, we explored the ultrafast energy transfer dynamics in hot drop-casted RRP films with a sandwich-like phase distribution using 2DES and transient-grating (TG) spectroscopy. The 2DES technique revealed energy transfer pathways by analyzing the dynamics of cross-peaks in 2D maps, while TG spectroscopy provided detailed insights into coherent vibrations accompanying the population dynamics. We have also compared the energy transfer dynamics observed in these hot drop-casted films with those previously reported in spin-coated films. These combined methods allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of the fundamental operating mechanisms in 2D RRP-based solar cells using hot drop-casted films.

Results and discussion

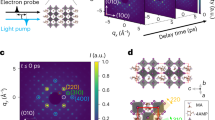

This study examines hot-drop casted films of (BA)2(MA)n−1Pbnl3n+1, with sample preparation procedures provided in the “Methods” section. The XRD and SEM characterization data of the films are provided in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. The films possess a layered structure, with small-n RPPs positioned between large-n RPP layers, creating a sandwich-like phase distribution12. A microscopic view of the 2D perovskite film on a quartz substrate is depicted in Fig. 1a. Scanning transmission electron microscopy data to support this architecture is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. The high-angle annular dark-field, HAADF-STEM image provides Z-contrast imaging scaling with the atomic number, Z40. As the average Z value of the RPP increases with the slab thickness (n), the dark region in the middle of the 2D perovskite film can be assigned to the small-n RPP and the bright region with higher Z value located on the top and bottom parts of the film are large-n RPP phase12,41. Thus, a sandwich-like phase distribution of large-n/small-n/large-n RPPs along the vertical direction for 2D perovskite film can be identified through STEM phase imaging.

a The schematic depicts the 2DES (Two-Dimensional Electronic Spectroscopy) experiment aimed at studying ultrafast photoinduced dynamics in hot drop-cast quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite films, which exhibit a sandwich-like phase distribution. A microscopic representation of the 2D perovskite film on a quartz substrate is also shown. b The laser spectrum (shaded in green) utilized in the 2DES experiment is overlaid with the experimental linear absorption spectrum (depicted by the red line). The excitonic transitions within the 2D perovskites of varying layers are indicated by dashed lines, referencing values from previous literature reports36,42.

The reverse-layered architectures, where n = 2 RPP layers are positioned in the outer regions and larger-n RPP layers are located internally could also be valuable for studying excitonic interactions, but our design prioritizes photovoltaic applications. Placing large-nn RPP layers on the outer surface enables efficient excitonic energy funneling to electrodes, unlike reverse architectures where energy predominantly will decay internally. While laser pulses with sufficient bandwidth could excite all layers for interlayer energy transfer studies in our sample of interest, our current setup is bandwidth-limited. Therefore, the laser spectrum has been carefully tailored to overlap with these excitonic transitions, maximizing the excitation of different 2D layers during the experiment. In Fig. 1b, the laser spectrum employed in the 2DES experiment (shaded in green) is compared to the experimentally measured absorption spectrum of the perovskite film (illustrated by the red line). Dashed lines indicate the excitonic transition energies within 2D perovskite layers of varying thicknesses. Excitonic peaks are identified based on literature references36,42.

Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy

To examine ultrafast dynamics in these hot-drop casted films of (BA)2(MA)n−1Pbnl3n+1 with layered structure, we perform 2DES experiments with excitation pulses that are 12 fs in duration. All experiments in this work were carried out at room temperature. A detailed description of this technique and our experimental setup can be found in the “Methods” section. Figure 2 shows the 2D electronic spectra measured for different waiting times, T. The ground-state bleach (GSB) and stimulated emission (SE) are shown in red, while excited-state absorption (ESA) is represented in blue.

The spectra are plotted with the x-axis(ωt) representing the probe frequency and the y-axis(ωτ) corresponding to the excitation frequency, providing a detailed depiction of the spectral features as a function of temporal evolution, which τ and t represent the first and third period of time. Ground-state bleach and stimulated emission are shown in red, while excited-state absorption is represented in blue. The experiment utilized a 12-fs laser pulse. Dashed lines in the 2D spectrum at T = 30 fs highlight the excitonic transition energies for various 2D perovskite layers. Diagonal excitonic bleach peaks, labeled A, B, C, and D, correspond to 2D layers with n = 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Excitonic coupling peaks, labeled AB, BC, and CD, represent the interactions between these transitions.

In the 2DES spectra at T = 30 fs, prominent diagonal peaks are clearly visible. The dashed lines in this spectrum mark the excitonic transition energies corresponding to various 2D perovskite layers. The deviation of the maximum bleach intensities from the diagonal in a 2DES map is evident, and this phenomenon can be attributed to the influence of reorganization energy43. Reorganization energy (λ) refers to the energy required to rearrange the surrounding environment (e.g., solvent or lattice) upon electronic excitation. This energy can contribute to a deviation in peak positions due to the altered environment affecting the electronic energy levels. In other words, the reorganization energy influences the system Hamiltonian and, consequently, the 2DES response. Thus, the observed deviation reflects the interaction between the electronic system and its environment, with shifts being indicative of the degree of energy redistribution upon excitation.

The diagonal peaks are labeled A, B, C, and D, corresponding to 2D layers with n = 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. The excitonic GSB peak for the 2D layer with n = 2 is not sufficiently excited within the bandwidth of the laser used in the 2DES experiments. Off-diagonal peaks are observed even in the early time spectrum at T = 30 fs. These excitonic coupling peaks, labeled AB, BC, and CD, represent the interactions between n2→n3, n3→n4, and n4→ n5, respectively. The presence of the cross-peak AB alongside the absence of the corresponding excitonic bleach peak A is intriguing but can be rationalized by considering the underlying factors that determine peak intensities. The laser spectrum used for the experiments has tailing-edge photon frequencies that overlap with the absorption band of the n = 2 layers. While the intensity of these photons is low, their spectral presence is sufficient to generate a detectable signal at the cross-peak AB. Mathematically, the intensity of a diagonal or cross-peak in a 2DES map is proportional to the overlap of the laser spectrum (E(ω)2), with the relevant transition frequency and the strength of coupling or population transfer. For the diagonal peak of the n = 2 layer, the limited overlap of the laser spectrum leads to a weak bleach signal due to insufficient excitation photons. However, cross-peaks such as AB arise from energy transfer between n2 and n3 layers, which depend on the coupling strength (μ12) and the population transfer dynamics. The tailing-edge photons in the laser spectrum effectively enable the excitation of the n2 layers, resulting in the observed signal at the cross-peak AB.

At very short delay times, cross-peaks between all excitonic resonances within the laser bandwidth indicate that excitons across all 2D layers are electronically coupled. As the delay time increases, the diagonal peak B, associated with the 2D layer with n = 3, shows a decay in intensity, while the off-diagonal features increase in intensity. By T = 48,632 fs, the 2D spectrum shows the complete decay of peak B, and peak C also exhibits a significant reduction in amplitude. In contrast, peak D, corresponding to the 2D layer with n = 5, increases in intensity. These variations indicate the directional flow of excitation energy between the layers. After photoexcitation, energy transfers from small-n RPPs to larger-n RPPs, with all excitation energy eventually localized in the outer n = 5 RPP layers at longer timescales.

To investigate the dynamics of the energy funneling process, kinetic traces for both on- and off-diagonal peaks were extracted and fitted to multi-exponential functions, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The resulting time constants are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. For Peak B (n = 3), the initial rise occurs over ~220 fs, followed by a decay time of 1.5 ps. If excitonic energy transfer or relaxation within the material takes place on an ultrafast timescale, this rapid rise in the GSB band suggests that excitons are quickly populating lower-energy states along the diagonal, within the inhomogeneously broadened ensemble. Therefore, the rapid rise of Peak B is likely a reflection of the ultrafast energy transfer from the n = 2 to n = 3 layers. Similarly, Peak C (n = 4) shows a rise time of approximately 1 ps. It is important to note that SE may also contribute to the signal in the 2D electronic spectrum. Since both GSB and SE have a negative contribution to the signal (i.e., both bleach absorption), disentangling these contributions can be challenging. If SE arises from the same excitonic states as the GSB band, it may enhance the observed rise of the GSB, leading to an even faster apparent rise in the total signal.

Peaks B, C, and D represent on-diagonal peaks, while peaks AB, BC, and CD correspond to off-diagonal peaks. τ data represents the population time of each exponential function. The experimental data are depicted by red circles, with the blue line representing the multi-exponential fits. The red trace in each graph shows the residuals of the fitting curves.

Peak D (n = 5) displays an initial ultrafast decay component of ~340 fs, followed by a slower rise of 23 ps. Fits to the longer delay times are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6. The ~340 fs decay component might be indicative of slow spectral diffusion. Previous reports by Proppe et al. have shown fast spectral diffusion ~30 fs) in layered RPPs, attributed to electronic dephasing36. In contrast to these findings, our data do not exhibit fast decay components in Peaks B and C, while Peak D shows a slower decay with a small amplitude in its kinetic trace. To estimate the electronic dephasing timescales, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the prominent on-diagonal features was analyzed, yielding an electronic dephasing timescale of ~18 fs and ~8.5 (details provided in Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, the ~340 fs decay observed for Peak D may have a different origin. This slow spectral diffusion could be associated with long-lived coherence or slower dephasing processes. Coherent interactions between excitons and the lattice may contribute to this gradual spectral shift.

The dynamics of the off-diagonal peaks provide insights into excitonic energy transfer between different perovskite layers. The AB peak (n2→ n3) exhibits a rise time of approximately 1 ps, indicative of the energy transfer dynamics from n2 to n3. In contrast, the dynamics of Peak B (n = 3) demonstrate a much faster rise time of around 220 fs, significantly faster than the rise observed in Peak AB. As previously noted, this rapid rise of Peak B may be attributed to overlapping SE signals. It is important to note that the fitting to 1 ps time component has a significant margin of error, and it is possible that a small amplitude ultrafast rise component, similar to that observed in the dynamics of diagonal peak B, is also present. This ~1 ps time constant has a relatively large error margin of ±0.8 ps, making a direct comparison challenging. The observed discrepancy can also arise from the overlapping dynamics of different signals. The BC peak (n3 → n4) exhibits an initial rise of about 100 fs, followed by slower decay components, consistent with previously reported ultrafast energy transfer from n3 to n4. Similarly, the CD peak (n4→ n5) shows a rapid rise of ~165 fs, followed by a slower decay. This rise time in Peak CD corresponds to the energy transfer timescale from n4 to n5. Thus, the observed dynamics of the off-diagonal peaks provide valuable insights into the excitonic energy transfer processes within the different layers of the 2D perovskite structure.

Transient-grating spectroscopy

After obtaining an understanding of energy flow timescales within the hot-drop casted films of (BA)2(MA)n−1Pbnl3n+1, we measure the transient-grating response of these films to capture the wave-packet dynamics associated with the population dynamics. TG spectroscopy is phase-sensitive, as it involves creating an interference pattern between two pump pulses and detecting the resulting diffraction signal from the sample. This phase sensitivity facilitates the isolation of coherent oscillations, such as those caused by vibrational or electronic coherence, by enhancing their separation from incoherent background signals.

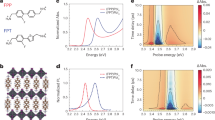

The TG spectrum, illustrated in Fig. 4a, reveals distinct regions of positive and negative magnitudes corresponding to different spectroscopic signals. The red regions, indicating positive magnitudes, are associated with GSB and SE signals, while the blue regions, representing negative magnitudes, provide spectroscopic evidence of ESA. GSB and SE signals are predominantly located within the detection wavelength range of 600 nm to 650 nm, whereas ESA is observed between 550 nm and 580 nm, with a weaker ESA band detected around 680 nm. To investigate coherent dynamics, specific spectral bands, marked by dashed lines in Fig. 4a, were selected for analysis. The corresponding kinetic traces are plotted as blue solid lines in Fig. 4b, c, with multi-exponential fits superimposed as black dashed lines. The residuals from the fitting procedures are displayed as red solid lines in the same panels. Fourier transforms were performed on the kinetic traces to resolve vibrational frequencies, with the results presented as red solid lines in Fig. 4d, e. The most prominent vibrational frequencies are indicated by dashed lines in these figures. In the frequency range below 100 cm−1, two distinct frequencies, 40 cm−1 and 74 cm−1, are observed in the GSB band, as depicted in Fig. 4e. In contrast, the ESA band shows only the 40 cm−1 frequency, with the 74 cm−1 component significantly diminished, as shown in Fig. 4d. These vibrational peaks, found below 100 cm−1, are attributed to in-phase and out-of-phase Pb-I stretching vibrations and octahedral rotations44,45,46. In the 100–200 cm−1 range, vibrational modes of the methylammonium moieties, coupled with the inorganic sublattice, are assigned. Specifically, the signal around 125 cm−1 corresponds to libration modes, while the band near 180 cm−1 is associated with torsional modes. The frequency region from 300 to 500 cm−1 contains bands attributed to the vibrational modes of the organic component (n-butylammonium), with this region exhibiting substantial frequency changes47.

The kinetics of the ESA [586 nm, marked by yellow dashed lines in (a)] and GSB [606 nm, marked by blue dashed lines in (a)] are shown as blue lines in (b) and (c), respectively. The associated exponential fitting curves are presented as black dashed lines. The obtained residuals of the ESA and the GSB bands are magnified and shown as red solid lines. A Fourier transform has been performed to examine the vibrational dynamics, the obtained power spectra of ESA and GSB are shown red lines in (d) and (e), respectively. The marked green dashed lines indicate the vibrational frequencies at 40, 74, 125 and 180 cm−1, respectively. The corresponding wavelet analysis is presented in (f) and (g).

Further investigation into the time-resolved behavior of these vibrational modes was conducted through wavelet analysis, which reveals the coherent dynamics in both ESA and GSB. The details of the wavelet analysis have been provided in Supplementary Fig. 7. The time-resolved vibrational coherence in the ESA and GSB bands is shown in Fig. 4f and g, respectively. The results indicate that in the GSB and SE bands, the 40 cm−1 vibrational mode persists beyond the 2 ps detection window, exhibiting long-lasting vibrational coherence throughout the process. A notable change in the lattice phonon frequency is observed around 1 ps, as seen in Fig. 4g. In contrast, the ESA map in Fig. 4f shows that while the vibrational coherence at 40 cm−1 is long-lived, the coherence corresponding to the 74 cm−1 mode decays within 1 ps. Additionally, vibrational coherences involving the interaction between the inorganic sublattice and organic cations, occurring in the 100–200 cm−1 range, dephase within 1 ps. In the high-frequency region, a strong oscillatory signal, lasting ~250 fs, is clearly observed in the ESA map provided in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Theoretical calculations

To simulate the population dynamics observed in hot drop-cast RRP films, we developed a theoretical model based on a simplified Hamiltonian framework. The time-nonlocal approach was employed to compute the dynamics. Detailed descriptions of the Hamiltonian, including the energy and coupling parameters utilized, are outlined in the “Methods” section of the manuscript. To replicate the experimental conditions, we initialized the population distribution across different 2D-layer energy states, (n = 2, 3, 4, 5), with respective distributions of 5%, 40%, 40%, and 15%, closely aligning with the pulse profile used in our 2DES experiments. Using this configuration, we calculated the population dynamics. The resulting time constants for energy and charge transfer between the layers are summarized in Table 1. Our simplified theoretical model successfully reproduces the experimentally observed fast energy transfer timescales between layers and captures the slower charge transfer processes occurring over timescales >10 ps.

Excitons or charge carriers generated upon photoexcitation can interact with the lattice through exciton-phonon coupling, leading to lattice relaxation or deformation. The strong exciton-phonon coupling in these materials is primarily due to their reduced dimensionality and soft lattice structure. Upon resonant photoexcitation in 2D RRP layered perovskites, we observe ultrafast excitonic energy funneling between different layers, evidenced by off-diagonal peaks coupling excitonic features from distinct layers, consistent with previous reports. Additionally, slower picosecond-scale time components are detected, which have been previously attributed to charge transfer processes36. Specifically, our TG and 2DES experiments resolved timescales for exciton and charge transfer show no distinct spectral signatures of anionic or cationic species. This absence could be attributed to the low oscillator strengths of the charged species in the experimental range explored. Our findings align with prior report and simulations by Proppe et al. that distinguish between the dynamics of exciton and charge transfer in perovskite quantum wells. Charge transfer was found to occur over 10s to 100s of picoseconds, far slower than exciton transfer, which occurs in 100s of femtoseconds.

The exciton energy funneling timescales align with the characteristics of energy transfer processes described by Förster theory in the weak coupling regime, where energy transfer depends on spectral overlap and electronic coupling between donor and acceptor states. Förster theory predicts that the energy transfer rate k\({}_{FRET}\propto {{{\rm{J.V}}}}_{DA}^{2}\), where J is the spectral overlap integral between the donor’s emission and acceptor’s absorption, and VDA represents the electronic coupling element. In the RPP films studied, the small-n layers (higher-energy states) act as donors, while the large-n layers (lower-energy states) serve as acceptors, supported by the observed exciton funneling dynamics. Additionally, the layered architecture of RPP films, with strong orientational alignment, enhances the transition dipole interactions VDA. Our observations of faster energy transfer times in films with smaller-n RPP layers further corroborate this mechanism, as FRET theory predicts an increase in transfer rates with stronger spectral overlap. In hot-drop casted films with sandwich architecture with a higher proportion of small-n layers, the distribution of donor-acceptor pairs optimizes this spectral overlap. This sandwich configuration will enhance the transfer rate, as evidenced by the faster observed energy transfer times, compared to systems with linear gradation of the quasi-2D layers.

As the system relaxes after photoexcitation, the exciton-phonon coupling induces a red shift in the vibrational frequencies of the lattice phonons, particularly those associated with the ground state. This red shift is reflected in the GSB signal, as the altered lattice exhibits a different vibrational environment compared to the unexcited state. Therefore, the observed change in lattice phonon frequencies in the GSB wavelet map in Fig. 4g can be attributed to this lattice relaxation and exciton-phonon interaction. In contrast, in the excited state, excitons or carriers may exhibit reduced coupling to the lattice due to screening effects, which can suppress lattice distortions and limit the formation of polarons. The excited state often involves a reconfigured or relaxed lattice structure, making the phonon red shift due to lattice distortions less pronounced in the ESA signal compared to the GSB. If the lattice relaxes quickly in the excited state, the corresponding vibrational modes may not be as prominently observed in the ESA. This aligns with the experimental observation of fast decay of the ~74 cm−1 lattice vibrations, along with the organic cation vibrations coupled to the inorganic lattice modes, leading to a diminished intensity in the FT map.

Photoexcitation-induced distortions of the inorganic sublattice have been previously reported in both 2D and 3D perovskites48,49. Prior studies have demonstrated that photoexcitation initiates dynamic lattice distortions, including angular deformations in the inorganic octahedral framework. Building on these insights, Zhang et al. employed ultrafast electron diffraction to directly probe the structural dynamics of 2D perovskites50. Their results revealed an ultrafast reduction in antiferro-distortion angles (Δθ ~ 0.25°) occurring within 1 ps, driven by strong carrier-lattice interactions triggered by high-density electron-hole plasma. This work provided key evidence for light-induced reconfiguration of the lattice symmetry, highlighting the coupling between electronic excitation and lattice reorganization at ultrafast timescales. In our study, we similarly observed a rapid reduction in the vibrational intensity associated with Pb-I bond dynamics on the ~1 ps timescale. This behavior is tentatively attributed to angular distortions along I-Pb-I bonds, as supported by earlier reports on photoexcitation-induced deformations in perovskite lattices. These angular distortions are consistent with the mechanisms described in prior studies, where photoinduced carrier-lattice interactions result in transient changes to bond angles and vibrational modes. This vibrational intensity decay aligns with the timescale of excitonic energy transfer observed in 2DES, suggesting that exciton-phonon coupling may play a significant role in mediating these ultrafast processes.

Additionally, changes in the vibrational frequencies of the bridging n-butylammonium cation between GSB and ESA highlight the changes in the interaction of these organic cations with the inorganic lattice. In summary, photoexcitation in these materials triggers strong exciton-phonon interactions, significant lattice relaxation, and angular distortions, which, in turn, alter the interactions with both methylammonium and n-butylammonium cations encapsulated within and bridging the layers, respectively. To gain atomistic insights into these observations, future plans include utilizing time-resolved electron diffraction to probe the system. This technique offers atomic-scale resolution, enabling the capture of structural dynamics in real time. It will reveal crucial details such as lattice distortions, exciton-phonon interactions, and angular distortions within 2D perovskites.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides detailed insights into the ultrafast dynamics and exciton-phonon interactions within 2D layered perovskites using a combination of 2DES and TG measurements. The results demonstrate that upon resonant photoexcitation, excitonic energy funneling occurs between different perovskite layers on ultrafast timescales, as evidenced by the appearance of off-diagonal peaks coupling excitonic transitions from distinct layers. The observed exciton transfer from smaller-n to larger-n RPP layers suggests directional energy flow within the material. This energy transfer is complemented by slower picosecond-scale components, which are attributed to charge transfer processes. Additionally, TG spectroscopy revealed the dynamics of coherent lattice distortion modes, offering critical insights into exciton-phonon interactions. These dynamics suggest that lattice deformation plays a significant role in photoexcitation, contributing to energy dissipation through non-radiative pathways. The rapid decay of the 74 cm−1 mode indicates fast lattice relaxation in the excited state, which could limit charge carrier mobility. This observation corroborates our findings that the excited state exhibits reduced lattice coupling due to screening effects, leading to faster decay of certain vibrational modes. Furthermore, the gradual decay of specific vibrational modes involving organic cations, such as n-butylammonium, highlights the dynamic interactions between organic and inorganic layers. These interactions are sensitive to lattice distortions and angular changes induced by photoexcitation, reflecting the intricate coupling between the structural and electronic properties of the material. These findings suggest actionable strategies for improving optoelectronic efficiency. Engineering the lattice to minimize exciton-phonon coupling, for instance, could reduce non-radiative losses and enhance charge transport. Additionally, altering the film’s structural composition and morphology to optimize these vibrational dynamics may further improve device performance. By gaining a deeper understanding of these processes, our study underscores the importance of controlling lattice dynamics and morphology to tailor quasi-2D RPP materials for superior optoelectronic device applications.

Methods

Sample preparation

Lead iodide (PbI2), methylammonium iodide (MAI), methylammonium chloride (MACl), and n-butylammonium iodide (BAI) were purchased from Polymer Light Technology Corp and used without further purification. A 0.8 M BA2MAn−1PbnI3n+1 (n = 5) precursor solution was prepared by dissolving 738.1 mg PbI2, 203.5 mg MAI, 128.6 mg BAI dissolved in 2 ml N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%) followed by magnetic stirring on a 70 °C hot plate for 3 h. After cooling down to room temperature, 6.5 mg (6 mol%) MACl was added into the precursor solution as additive and stirred for another 1 h. Then, 50 μL of 6 mol% MACl doped BA2MAn−1PbnI3n+1 (n = 5) (0.8 M) was dropped onto a clear glass substrate (1 × 1 cm), which was preheated to 100 °C on a hot plate and immediately transferred to a vacuum chuck of a spin-coater, and spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 35 s. After the subsequential annealing at 100 °C for 2 min, hot-spin-cast 2D BA2MAn−1PbnI3n+1 (n = 5) films were prepared.

TG and 2D electronic spectroscopy

Details of the experimental setup have been described in earlier reports from our group24. Briefly, the measurements have been performed on diffractive optics based on an all-reflective 2D spectrometer with a phase stability of λ/160. The laser beam from a home-built nonlinear optical parametric amplifier (NOPA, pumped by a commercial spectral physics laser from Newport) is compressed to ~12 fs using the combination of a deformable mirror (OKO Technologies, 19 channels) and a prism pair (Fused silica). Frequency-resolved optical grating (FROG) measurement is used to characterize the temporal profile of the compressed beam and the obtained FROG traces are evaluated using a commercial program FROG3 (Femtosecond Technologies). An obtained broadband spectrum carried a line width of ~100 nm (FWHM) cantered at 620 nm, which covered the excitonic transitions corresponding to different layers in the 2D RRP films. Three pulses are focused on the sample with spot size of ~130 μm and the photon-echo signal is generated at the phase-matching direction. The photon-echo signals are collected using Sciencetech spectrometer model 9055F, which is coupled to a CCD linear array camera (Entwicklungsbüro Stresing). The TG spectra for each waiting time T were collected by scanning the delay time in the range of [−200 fs, 3 ps] with a delay step of 3 fs. At each delay step, 300 spectra were averaged to reduce the noise ratio. For 2D measurements, the spectra are collected with coherent time [−64, 64] fs and delay time from 0 fs to 500 ps. The time step is generated with an exponential scale. 100 spectra are employed to obtain the averaged signals in each 2DES. For all measurements, the energy of the excitation pulse is attenuated to 20 nJ with 1 kHz repetition rates. Phasing of the obtained 2D spectra was performed using an “invariant theorem,” which has been described in ref. 51.

To mitigate the effects of sample degradation during the experiments, we employed very low excitation energy for photoexcitation (20 nJ with a focal spot size of 130 μm). Furthermore, the perovskite film was sandwiched between two substrates and sealed to prevent any humidity-induced degradation. To ensure sample stability during measurements, we conducted transient absorption (TA) experiments on the sample position both before and after our measurements. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, no significant changes were observed in the TA data, confirming the stability of our samples throughout the experiments.

Theoretical calculations

In order to compare with the experimental results, we established a simple Hamiltonian model and use the time-nonlocal method to calculate the dynamics. The Hamiltonian model is written as

where \(\left\vert g\right\rangle\) is the ground state, \(\left\vert C{T}_{i}\right\rangle\) (i = 3, 4) are the charge transfer state and \(\left\vert {n}_{i}\right\rangle\) (i = 2, 3, 4, 5) are the different excitons of layers. ϵi represent the energy gaps between the corresponding excited states and the ground state. The value V indicates the correlation strength between two states. The value of each parameter is shown in Table 1. In this table, ϵi (i = 2, 3, 4, 5) comes from the exciton energy gap, which can be obtained from Fig. 1 and \({\epsilon }_{C{T}_{i}}\) (i = 3, 4) represents the gap between the ground state and the charge transfer state. The value of parameters Vij (i = j±1) are set to 100 cm−1, bigger than Vij (i = j±2) equals 20 cm−1 because the distance between neighboring layers is closer than non-adjacent layers. We set V25 = V52 as 0 cm−1 since the distance between the layers with two layers in between is so large that the correlation is negligible. \({V}_{C{T}_{i},i}\)=\({V}_{C{T}_{i},i+1}\) represents the coupling strength between the CT state and the exciton state.

In addition, to include the dissipation, we assume that every layer is coupled to the displacements of harmonic bath oscillators, thus, we have

Here, α is the index of the bath modes. pα, mα and ωα are the momenta, mass and frequency of the α-th mode coupled to q, and the cα is the coupling coefficient. The frequency distribution of the bath modes has the form

where γ0 is the coupling strength and ωc is the cutoff frequency. The population result is in Fig. 5 and the total fit result compared with the experimental result is displayed in Table 2. Comparing these results, we can find that the order of magnitude is consistent.

a Population dynamics of the perovskite model presented over a duration of 250 ps with a time resolution of 1 fs. The hollow blue, red, and yellow circles correspond to the population data of the 5-layer, 4-layer, and 3-layer systems, respectively. The solid blue, red, and yellow lines represent the respective fitted population data for each layer, demonstrating the correlation between observed and modeled dynamics. b A schematic representation of energy funneling mechanisms within the hot drop-cast 2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites (RPP) films. The diagram highlights the pathways of energy transfer alongside the corresponding time constants for energy and charge transfer processes across the layered system.

Data availability

Numerical data from figures are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Computer codes for numerical calculation are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kim, J. Y. et al. High-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Chem. Rev. 120, 7867–7918 (2020).

Hu, S. et al. Narrow bandgap metal halide perovskites for all-perovskite tandem photovoltaics. Chem. Rev. 124, 4079–4123 (2024).

Quan, L. N. et al. Ligand-stabilized reduced-dimensionality perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2649–2655 (2016).

Yuan, M. et al. Perovskite energy funnels for efficient light-emitting diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 872–877 (2016).

Tsai, H. et al. High-efficiency two-dimensional Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite solar cells. Nature 536, 312–316 (2016).

Yu, W. et al. Breaking the bottleneck of lead-free perovskite solar cells through dimensionality modulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 1769–1788 (2024).

Gu, H. et al. Phase-pure two-dimensional layered perovskite thin films. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 533–551 (2023).

Metcalf, I. et al. Synergy of 3D and 2D perovskites for durable, efficient solar cells and beyond. Chem. Rev. 123, 9565–9652 (2023).

Smith, I. C. et al. A layered hybrid perovskite solar-cell absorber with enhanced moisture stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 11232–11235 (2014).

Ricciardulli, A. G. et al. Emerging perovskite monolayers. Nat. Mater. 20, 1325–1336 (2021).

Liu, P. et al. High-quality Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite film formation for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 33, 2002582 (2021).

Zheng, F. et al. A sandwich-like structural model revealed for quasi-2D perovskite films. J. Mater. Chem. C 9, 5362–5372 (2021).

Quintero-Bermudez, R. et al. Compositional and orientational control in metal halide perovskites of reduced dimensionality. Nat. Mater. 17, 900–907 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Spacer cation tuning enables vertically oriented and graded quasi-2D perovskites for efficient solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008404 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. Synthetic control over orientational degeneracy of spacer cations enhances solar cell efficiency in two-dimensional perovskites. Nat. Commun. 10, 1276 (2019).

Zuo, C. et al. Crystallisation control of drop-cast quasi-2D/3D perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Comm. Mater. 1, 33 (2020).

Biswas, S. et al. Coherent two-dimensional and broadband electronic spectroscopies. Chem. Rev. 122, 4257–4321 (2022).

Fuller, F. D. & Ogilvie, J. P. Experimental implementations of two-dimensional Fourier transform electronic spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 66, 667–690 (2015).

Jonas, D. M. Two-dimensional femtosecond spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 54, 425–463 (2003).

Prokhorenko, V. I., Halpin, A. & Miller, R. J. D. Coherently-controlled two-dimensional photon echo electronic spectroscopy. Opt. Express 17, 9764–9779 (2009).

Brey, D. et al. Signatures of coherent vibronic exciton dynamics and conformational control in the two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy of conjugated polymers. Faraday Discuss. 237, 148–167 (2022).

Cao, J. et al. Quantum biology revisited. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4888 (2020).

Collini, E. 2D electronic spectroscopic techniques for quantum technology applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 13096–13108 (2021).

Duan, H.-G. et al. Quantum coherent energy transport in the Fenna-Matthews-Olson complex at low temperature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2212630119 (2022).

Duan, H.-G. et al. Intermolecular vibrations mediate ultrafast singlet fission. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0052 (2020).

Duan, H.-G. et al. Nature does not rely on long-lived electronic quantum coherence for photosynthetic energy transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8493–8498 (2017).

Jha, A. et al. Origin of poor doping efficiency in solution processed organic semiconductors. Chem. Sci. 9, 4468–4476 (2018).

Jha, A. et al. Unraveling quantum coherences mediating primary charge transfer processes in photosystem II reaction center. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk1312 (2024).

Tiwari, V. et al. Multitype electronic interactions in precursor solutions of molecular doped P3HT polymer. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 3249–3257 (2024).

Duan, H.-G. et al. Photoinduced vibrations drive ultrafast structural distortion in lead halide perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16569–16578 (2020).

Jha, A. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast exciton dissociation in lead iodide perovskite by 2D electronic spectroscopy. ACS Photonics 5, 852–860 (2018).

Monahan, D. M. et al. Room-temperature coherent optical phonon in 2D electronic spectra of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite as a possible cooling bottleneck. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 3211–3215 (2017).

Richter, J. M. et al. Ultrafast carrier thermalization in lead iodide perovskite probed with two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 376 (2017).

Seiler, H. et al. Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy reveals liquid-like lineshape dynamics in CsPbI3 perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 10, 4962 (2019).

Tiwari, V. et al. Evidence and implications for exciton dissociation in lead halide perovskites. EPJ Web Conf. 205, 06018 (2019).

Proppe, A. H. et al. Spectrally resolved ultrafast exciton transfer in mixed perovskite quantum wells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 419–426 (2019).

Shang, Q. et al. Unveiling structurally engineered carrier dynamics in hybrid quasi-two-dimensional perovskite thin films toward controllable emission. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4431–4438 (2017).

Lin, D. et al. Unveiling hot carrier relaxation and carrier transport mechanisms in quasi-two-dimensional layered perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 25402–25410 (2020).

Williams, O. F. et al. Energy transfer mechanisms in layered 2D perovskites. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 134706 (2018).

Gonzalez, J. C. et al. 3D characterization of gold nanoparticles supported on heavy metal oxide catalysts by HAADF-STEM electron tomography. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 5313–5315 (2009).

Zheng, F. et al. Brownian tree-shaped dendrites in quasi-2D perovskite films and their impact on photovoltaic performance. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2102231 (2022).

Cao, D. H. et al. 2D homologous perovskites as light-absorbing materials for solar cell applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7843–7850 (2015).

Johnson, P. J. M. et al. The primary photochemistry of vision occurs at the molecular speed limit. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 4040–4047 (2017).

Dahod, N. S., France-Lanord, A., Paritmongkol, W. & Grossman, J. C. Low-frequency Raman spectrum of 2D layered perovskites: local atomistic motion or superlattice modes? J. Chem. Phys. 153, 044710 (2020).

Spirito, D., Asensio, Y., Hueso, L. E. & Martín-García, B. Raman spectroscopy in layered hybrid organic inorganic metal halide perovskites. J. Phys. Mater. 5, 034004 (2022).

Biega, R.-I. et al. Dynamic distortions of quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites at elevated temperatures: influence on thermal and electronic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 9183–9195 (2023).

Cortecchia, D. et al. Broadband emission in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites: the role of structural deformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 39–42 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Light-induced picosecond rotational disordering of the inorganic sublattice in hybrid perovskites. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602388 (2017).

Cuthriell, S. A. et al. Nonequilibrium lattice dynamics in photoexcited 2D perovskites. Adv. Sci. 34, 2202709 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Ultrafast relaxation of lattice distortion in two-dimensional perovskites. Nat. Phys. 19, 545–550 (2023).

Hybl, J. D., Ferro, A. A. & Jonas, D. M. Two-dimensional Fourier transform electronic spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 115, 6606 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1409800), NSFC Grant with No. 12274247 and No. 62304116, Yongjiang talents program with No. 2022A-094-G, Ningbo International Science and Technology Cooperation with No. 2023H009, ‘Lixue+’ Innovation Leading Project and the foundation of national excellent young scientist. The Next Generation Chemistry theme at the Rosalind Franklin Institute is supported by the EPSRC (V011359/1 (P)) (A.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G.D., F.Z. and A.J. conceived this research project and designed the optical measurement. X.Z. and J.Z. performed the ultrafast spectroscopic measurements and analyzed data. F.Z. and B.Y. prepared the sample and characterized it. H.G.D. and A.J. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors read and refined the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Zhou, J., Zheng, F. et al. Ultrafast exciton-phonon coupling and energy transfer dynamics in quasi-2D layered Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites. Commun Phys 8, 71 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01995-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01995-5