Abstract

It is generally believed that the non-Hermitian effect (NHSE), due to its non-reciprocal nature, creates barriers for the appearance of impurity bound states. In this paper, we find that in two and higher dimensions, the presence of geometry-dependent skin effect eliminates this barrier such that even an infinitesimal impurity potential can confine bound states in this type of non-Hermitian systems. By examining bound states around Bloch saddle points, we find that non-Hermiticity can disrupt the isotropy of bound states, resulting in concave dumbbell-shaped bound states. Our work reveals a geometry transition of bound state between concavity and convexity in high-dimensional non-Hermitian systems, offering theoretical insights for the experimental manipulation of bound states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The non-Hermitian Hamiltonian serves as an effective tool for describing systems that interact with environments1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Recently, non-Hermitian band systems have drawn much attention due to their intriguing phenomena that surpass the Bloch band framework16,17. A representative phenomenon is the non-Hermitian skin effect (NHSE)18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. In one dimension, the NHSE is characterized by a large number of eigenstates localized at the ends of an open chain, well understood in the generalized Bloch band framework18,21,25,28,34. In higher dimensions, the NHSE exhibits more complexity due to the interplay between mode localization and boundary geometries. Particularly, the NHSE may disappear under certain geometry but reappear under others. This dimensionality-enriched phenomenon is referred to as the geometry-dependent skin effect (GDSE)38,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49.

Impurities are fundamental in Hermitian systems and have been extensively studied for their broad applications. For example, magnetic impurities in metals induce phenomena such as the Kondo effect50, while in s-wave superconductors, they manifest as Yu-Shiba-Rusinov bound states51,52,53. Recently, the investigation of impurity states in non-Hermitian settings, especially their interplay with NHSE, has revealed various physical phenomena54,55. A key aspect is that, NHSE creates barriers for the formation of impurity bound states due to its non-reciprocal nature56,57. Consequently, a finite impurity potential is necessary to induce a bound state when NHSE is present58. However, these phenomena have primarily been studied in 1D non-Hermitian systems, it is still unclear whether impurity states can exhibit different properties in higher dimensions. Additionally, NHSE presents unusual characteristics in higher dimensions38,59,60, such as GDSE. The potential for impurity states to exhibit different behaviors in interaction with these emerging forms of NHSE in higher dimensions remains a significant and largely unexplored research gap.

In this paper, we find that in the presence of GDSE, the impurity potential exhibits a zero threshold for the emergence of bound states. We establish an exact mapping between the bound state energy and the required impurity potential, demonstrating that even an infinitesimal impurity potential can confine bound states in a non-Hermitian system exhibiting GDSE. A key reason is that the GDSE ensures the presence of Bloch saddle points, which eliminate barriers to impurity-bound state formation.

In two and higher dimensions, the geometry of equal amplitude contours of wavefunction introduces a unique characteristic for non-Hermitian impurity-bound states. We determine the geometry of bound states using the mathematical concept of amoeba. In two dimensions, impurities can host anisotropic, concave bound states, in sharp contrast to the isotropic, convex bound states in Hermitian systems. Furthermore, we reveal a geometric transition from convexity to concavity in bound states by manipulating the impurity potential. This transition, characterized using our method, is observable in experimental setups, such as through local density of states patterns (See details in Supplementary Note. III).

Result

A general theory of bound states in non-Hermitian systems

We start from a general tight-binding Hamiltonian with finite range couplings in two dimensions,

where \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})={\sum }_{l = -m,s = -n}^{l = M,s = N}{t}_{s,l}{({e}^{i{k}_{x}})}^{s}{({e}^{i{k}_{y}})}^{l}\), (x, y) represents the position of lattice site, and ts,l indicates the hopping strength. The Bloch spectrum is formed by the eigenvalues of \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\) as kx and ky scan over the entire Brillouin zone (BZ), which we denote by σPBC [red dots in Fig. 1a]. Note that though we focus on two-dimensional case here, the theory can be easily generalized to higher dimensions(see more detail in the Supplementary Note. I).

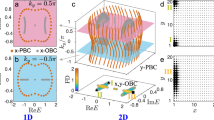

a shows the PBC spectrum of the Hamiltonian \({e}^{i\pi /6}\cos ({k}_{x}+{k}_{y})+{e}^{i\pi /3}\cos {k}_{x}\), with four black points denoting the energies at its BSPs. The black cross represents the bound state energy induced by the impurity. b illustrates the 1D Bloch saddle lines (BSLs) in the BZ, with brown lines representing \({\partial }_{{k}_{y}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})=0\) and gray lines for \({\partial }_{{k}_{x}+{k}_{y}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})=0\). The corresponding spectral lines \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\) are shown in the same color in (a). The four intersection points, i.e., high-symmetry k points in the BZ, are the BSPs and correspond to the four vertices in the spectrum shown in (a). Show the function ∣λ(δE)∣, corresponding to the blue and orange trajectories in (a), respectively. Here, δE is defined as \(E-{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(0,0)\) in (c) and \(E-{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(\pi /3,0)\) in (d). The insets in (c, d) show zoomed-in results as ∣λ∣ → 0.

To generate an impurity bound state, we place a single impurity potential of strength λ at the origin of the lattice, where the coordinate is set to (x0, y0) = (0, 0). The impurity potential takes the form

One can tune the impurity strength λ such that the excited bound state has an energy EBS appearing beyond the region of σPBC [the black cross in Fig. 1a]. Utilizing Green’s function method, the wavefunction of this bound state can be analytically obtained as61

where G0(E; x, y) = 〈x, y∣1/(E − H0)∣0, 0〉 is the Green’s function, H0 is given by Eq. (1), and ψE(0, 0) is determined by the wavefunction’s normalization condition. Setting x and y to zero in Eq. (3), the relationship between the bound state energy EBS and the required impurity strength λ is established as

Under PBC, the Green’s function on the right-hand side of Eq. (4) can be expanded under Bloch basis as an integral form, and thus the relationship becomes

Typically, a state with energy within a continuum spectrum is expressed as a scattering state. Correspondingly, the energy of a bound state should lie outside the region of σPBC. The critical point, where the bound state energy merges with the PBC continuous spectrum, signifies a phase transition. This phase transition determines the minimum impurity strength required to create bound states. Consequently, we can define the set of minimum impurity strengths as

where ∂σPBC represents the boundary of PBC continuum spectrum, and Eb denotes a spectral boundary point. We define the impurity strength threshold λ0 as the minimum absolute value ∣λ∣ in the set Λ. The Bloch saddle points (BSPs), denoted as \(({k}_{x}^{s},{k}_{y}^{s})\), refer to the saddle points in the BZ where the relation holds: \({\partial }_{{k}_{i}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x}^{s},{k}_{y}^{s})=0\) for i = x, y. In the following, we demonstrate that zero threshold of impurity strength is ensured by the presence of BSPs in the Bloch spectrum σPBC.

The critical response to impurity potential near BSPs

Here, we examine excitations around the BSP energy, assumed to be at the spectrum boundary Eb. The lattice Bloch Hamiltonian can be expanded at the BSP as \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({q}_{x},{q}_{y})={E}_{b}+t({q}_{x}^{2}+a\,{q}_{y}^{2}+b\,{q}_{x}{q}_{y})\), where qx and qy are deviations from the BSP momentum, and Eb, t, a, b are expansion coefficients. The linear qx and qy terms are omitted since Eb is a BSP. The qxqy cross term can be eliminated through proper momentum basis rotation, when \(\frac{| b{| }^{2}}{| a{| }^{2}}\le \frac{{(\sin (\arg a))}^{2}}{\sin (\arg a-\arg b)\sin (\arg b)}\). Therefore, the expanded Hamiltonian around a BSP can be classified by the coefficients a, b. For demonstration, we utilize the following concrete lattice Hamiltonian:

With a weak impurity potential, the excited bound state energy shifts slightly from the BSP energy \({E}_{b}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(0,0)\), i.e., ∣δE∣ = ∣EBS − Eb∣ ≪ 1. Substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (5), when ∣b∣, ∣δE∣ ≪ 1, the relationship between the impurity strength λ and the bound state energy EBS becomes (see details in Supplementary Note. II): \({\lambda }^{-1}(\delta E)=A\left(5\ln 2-\ln B-\ln \delta E\right)/2\pi\), where the parameters \(A=\sqrt{(a-2{b}^{2})/({a}^{2}-a{b}^{2})}\) and \(B=\sqrt{a(a+1)/{(a-{b}^{2})}^{2}}\). Here, λ−1(δE) diverges asymptotically as \(\ln \delta E\) when δE → 0, which is expressed as:

We emphasize that, as shown by Eq. (8), the bound state energy near the BSP is highly sensitive to the impurity potential, verified in Fig. 1c. This contrasts sharply with the linear response observed near the regular spectrum boundary energy, depicted in Fig. 1d. This sensitivity can be utilized to detect BSPs in higher-dimensional non-Hermitian systems45,46,47. As δE approaches zero, the required impurity potential λ also tends to zero, indicating a zero threshold at the BSPs, leading to the conclusion that BSPs ensure a zero threshold for impurity potential.

Numerical verification for the zero threshold at BSPs is illustrated in Fig. 1. As EBS approaches EBSP along the blue line in Fig. 1a, the required impurity potential decreases to zero (Fig. 1c). Conversely, when EBS approaches a regular spectral boundary energy along the orange trajectory in Fig. 1a, the impurity potential reaches a finite value (Fig. 1d). Dashed lines in Fig. 1c, d indicate the asymptotic behavior near the boundary.

A natural question arises: which systems ensure the existence of BSPs in higher dimensions? The answer lies in systems exhibiting GDSE. In GDSE, there are two special directions, k1 and k2. When boundary cuts are made along these directions, the open boundary eigenstates manifest as Bloch waves. By imposing open boundary conditions along k1 and periodic boundary conditions along k2, the k2 momentum is conserved, treating the Hamiltonian as a 1D k1-subsystem for a fixed k2. With no skin effect in the k1 direction, the energy spectrum forms an arc whose endpoints satisfy \({\partial }_{{k}_{1}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})=0\). As k2 varies from − π to π, these endpoints form two lines (brown lines in Fig. 1b). Similarly, two lines can be obtained for k2 (gray lines in Fig. 1b). At their intersections, the BSP conditions \({\partial }_{{k}_{i}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x}^{s},{k}_{y}^{s})=0\) for i = 1, 2 are satisfied, corresponding to four BSPs within the BZ. An example with {k1, k2} = {kx, kx + ky} is shown in Fig. 1b, where the intersections are marked by black dots.

Tailoring the geometry of bound states

According to Eq. (3), the bound state wave function is determined by Green’s function. The Green’s function can be expressed in an integral form with the Hamiltonian H0 given by Eq. (1):

Here, we extend the real momentum k to the complex value \({\tilde{k}}_{j}={k}_{j}+i{\mu }_{j}\) and define \({z}_{j}={e}^{i{k}_{j}}\) for j = x, y. Under PBC, the integration contour is the BZ (∣zx∣ = ∣zy∣ = 1), a torus in \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{2}\) space, denoted as \({{\mathbb{T}}}^{2}\). To compute this double integral, we adopt a step-by-step integration strategy. Firstly, we evaluate the first integral using the residue theorem. Noteondly, for the second integral, as we are primarily concerned with the asymptotic behavior of the wave function far from the impurity (∣x∣, ∣y∣ ≫ 1), we can use the saddle-point approximation to handle the second integral, resulting in:

Here, r = (x, y) and the complex momentum vector \({\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}_{s}(\theta )=({\tilde{k}}_{s,x}(\theta ),{\tilde{k}}_{s,y}(\theta ))\) is a saddle point of the exponent \(x\ln {z}_{x}+y\ln {z}_{y}=x{\tilde{k}}_{x}+y{\tilde{k}}_{y}\) in Eq. (9), depending on the spatial direction \(\theta =\arg ({{{\bf{r}}}})\). Eq. (10) demonstrates that the bound state wave function exhibits exponential behavior characterized by the complex momentum \(\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\) along a fixed direction θ, resulting in anisotropy in space. Therefore, we define the characteristic localization l that satisfies the relation: \(| {\psi }_{{E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}}({l}_{x},{l}_{y})| /| {\psi }_{{E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}}(0,0)| ={e}^{-1}\), which is further expressed as:

Here, \(({l}_{x},{l}_{y})=l\,(\cos \theta ,\sin \theta )\) forms a closed loop as θ changes, which characterizes the localization behavior and describes the geometric shape of impurity bound states.

For a fixed direction θ, the complex momentum \(\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\) is determined by solving specific constraints (see details in the Supplementary Note. I). The first constraint is the bulk characteristic equation,

The set of imaginary parts (μx, μy) of the complex momentum \(\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\) that satisfy the characteristic equation in Eq. (12) is termed amoeba, as represented by the gray regions in Fig. 2b1, b2. Since EBS ∉ σOBC, the corresponding amoeba always features a central hole62, as shown by the blank region in Fig. 2b1, b2. Moreover, by solving Eq. (12), \({\tilde{k}}_{x}\) or \({\tilde{k}}_{y}\) can be expressed as a function of the other. By applying the saddle point approximation \({\partial }_{{\tilde{k}}_{y}}(x{\tilde{k}}_{x}+y{\tilde{k}}_{y})=0\) to the exponential factor in Eq. (10) and utilizing the implicit function theorem \({\nabla }_{\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\cdot d\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}=0\), the second constraint can be derived as

For the impurity bound state, the first constraint in Eq. (12) links the solution domain of (μx, μy) to the mathematical term amoeba; the second constraint in Eq. (13), combined with Eq. (12), identifies several isolated points μs(θ) on the amoeba. By varying the spatial direction \(\theta =\arg {{{\bf{r}}}}\), μs(θ) forms a closed loop, corresponding to the amoeba’s contour63,64,65. In Fig. 2b1, b2, the amoeba’s contours are depicted by the black curves. The constraint in Eq. (13) is a homogeneous function of x and y, depending solely on the spatial direction \(\theta =\arctan (y/x)\). Consequently, the bound state wavefunction exhibits exponential localization away from the impurity site but is anisotropic in real space. Furthermore, by applying implicit function theorem \({\nabla }_{\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\cdot d\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}=0\) to Eq. (13), it can be transformed into the form \({{{\bf{r}}}}\cdot d\tilde{{{{\bf{k}}}}}=0\). Notably, this is a complex equation, and by taking its imaginary part, we obtain

This formula indicates that the inverse localization length μ(θ) of bound states along each spatial direction r is determined by the value μ(θ) = (μx, μy) on the amoeba’s contour, where the tangent direction is perpendicular to r.

Parameters {t1,1, t−1,−1, t1,0, t−1,0, t0,0} for Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) are set to be {2, 2, i, i, − 2i}. a The red points represent the Bloch spectrum near the Bloch saddle point \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(0,0)\). The two gray regions indicate the range for energy whose amoeba has two nodes (nnode = 2), which results in a concave wavefunction. And the white region is the range where the amoeba has no node (nnode = 0). The impurity strength is λ = 2.66 + 0.96i for bound state with energy \({E}_{{{{\rm{BS1}}}}}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(0,0)+0.2\exp (i\frac{\pi }{4})\) and λ = 2.27 + 2.23i for \({E}_{{{{\rm{BS2}}}}}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}(0,0)+0.2\exp (-i\frac{19}{40}\pi )\)). b1, b2 show the corresponding amoeba’s contours for EBS1 and EBS2 respectively outlined by the black curves. The red (blue) dot denotes the point of tangency between the red (blue) dashed line and the amoeba’s contour. The red (blue) dashed line is perpendicular to the red (blue) arrow. c1, c2 depict the amplitude ∣ψ∣of the bound states for EBS1 and EBS2 respectively. The gray dashed line is the equal amplitude curve of ∣ψ(x, y)∣. d1, d2 show a comparison of bound states between the simulated data (colored dots) and the theoretical predictions (colored line). The red (blue) dots and line correspond to the x(y)-axis. The slope of red (blue) line is given by the red(blue) point in (b1, b2). The results are obtained from simulations performed on a 30 × 30 lattice.

As a result, for a fixed direction r, we can determine the inverse localization length μ(θ) using Eq. (12) and Eq. (13). By varying the spatial direction \(\theta =\arg {{{\bf{r}}}}\), we find that the set of μ(θ) forms a closed loop on the amoeba, corresponding to the amoeba’s contour. Additionally, Eq. (14) indicates that the tangent direction of μ(θ) is perpendicular to r.

By substituting the values of (μx, μy) into Eq. (11), we can determine the geometric shape of the bound state. As shown in Fig. 2a, the bound states with energies EBS1 and EBS2 are depicted in Fig. 2c1, c2, respectively, with their corresponding amoebas in Fig. 2b1, b2. To further investigate localization behaviors, we plot \(\ln | {\psi }_{{E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}}(x,0)|\) and \(\ln | {\psi }_{{E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}}(0,y)|\) for these bound states in Fig. 2d1, d2. Our findings indicate that the decay rates along the x and y directions are determined by points on the amoeba’s contours, marked by red and blue dots in Fig. 2b1, b2. Numerical verifications in Fig. 2d1, d2 show that the slopes at these contour points, represented by red and blue lines, match the numerical bound state wavefunctions, as indicated by the red and blue dots.

We conclude that the amoeba’s contour encodes the localization lengths of the bound state along each spatial direction. Therefore, the amoeba’s contour’s geometric properties inevitably affect the shape of the wave function. Furthermore, since the amoeba’s contour is uniquely determined by the bulk Hamiltonian of the system, it establishes a connection between non-Hermiticity and bound state geometric features.

Geometry transition of bound state under weak impurity analysis

Using perturbation analysis with a weak impurity potential, we demonstrate a unique geometry transition in higher-dimensional non-Hermitian systems (see Supplementary Note. IV for strong impurity case). As mentioned, non-Hermitian systems with GDSE ensure the existence of BSPs, allowing bound state excitation by an infinitesimal impurity potential. Thus, GDSE systems provide a platform to examine bound state geometry with weak impurity excitation. The bound state geometry can be tailored by the amoeba’s contour, determined by the characterization equation \(f({E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}},{k}_{x},{k}_{y})={E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}-{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\). We focus on its expansion near the BSP energy EBSP, generally expressed as:

Here, the linear term of kx and ky vanishes due to the BSP condition, and cross term kxky is omitted for simplicity. By applying the constraints in Eq. (12) and Eq. (13), we can derive an algebraic curve of order 8 that describes the amoeba’s contour (see details in Supplementary Note. II). Based on Eq. (11), we ultimately obtain an algebraic curve that features the bound state geometry shape:

where \(\alpha =\arg ({E}_{{{{\rm{BS}}}}}-{E}_{{{{\rm{BSP}}}}})\). This curve describes the localization length of the wave function along different directions and determines the shape of the bound states.

When θ = 0, the Hamiltonian reduces to Hermitian, and the geometry curve collapses into a circle, given by

In the Hermitian limit, the shape of the bound state is always circular or elliptical due to scaling factors on kx or ky. However, when θ ≠ 0, varying α causes a transition in the bound state shape from a regular convex curve (Fig. 2b1) to a concave, dumbbell-like curve (Fig. 2b2), a feature unique to higher-dimensional non-Hermitian systems. This corresponds to the amoeba’s contour transition from a regular curve (Fig. 2b1) to an irregular curve with multiple singular nodes (Fig. 2b2). A curve is convex if it has positive or negative curvature throughout its path, while singular nodes, which always appear in pairs due to reciprocity symmetry in GDSE systems, occur where the curve intersects itself. Concave geometry of bound states occurs if and only if the phase (α − θ) or (θ − α) falls within (0, θ), as detailed in the Supplementary Note. II. For weak impurity excitation near BSPs, when θ < α < 2θ or −θ < α < 0 (gray region in Fig. 2a), the amoeba contour shows two nodes, resulting in a concave bound state wave function geometry.

Conclusion

In summary, we investigate impurity-induced bound states in 2D non-Hermitian lattice systems. The geometry of bound states is precisely determined by the corresponding amoeba. The presence of BSPs eliminates the threshold for the formation of impurity-bound states. The resulting bound state wavefunctions around BSPs can exhibit concave and anisotropic shapes, in stark contrast to the convex and isotropic configurations typically observed in Hermitian systems. Furthermore, we unveil a geometric transition from convexity to concavity in bound states by manipulating the impurity potential. Since GDSE ensures the existence of BSPs, even an infinitesimal impurity potential in such systems can generate bound states near the BSP energy, making them ideal platforms for studying weak excitations. These findings demonstrate how non-Hermitian properties significantly enrich the geometric configurations of bound states.

Code availability

All the computational codes that were used to generate the figures presented in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Rotter, I. A non-hermitian hamilton operator and the physics of open quantum systems. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 42, 153001 (2009).

Diehl, S., Rico, E., Baranov, M. A. & Zoller, P. Topology by dissipation in atomic quantum wires. Nat. Phys. 7, 971–977 (2011).

Malzard, S., Poli, C. & Schomerus, H. Topologically protected defect states in open photonic systems with non-hermitian charge-conjugation and parity-time symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 200402 (2015).

Dalibard, J., Castin, Y. & Mølmer, K. Wave-function approach to dissipative processes in quantum optics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 580–583 (1992).

Regensburger, A. et al. Parity–time synthetic photonic lattices. Nature 488, 167–171 (2012).

Gao, T. et al. Observation of non-Hermitian degeneracies in a chaotic exciton-polariton billiard. Nature 526, 554–558 (2015).

Feng, L., El-Ganainy, R. & Ge, L. Non-Hermitian photonics based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Photonics 11, 752–762 (2017).

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 14, 11–19 (2018).

Miri, M.-A. & Alù, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 363, eaar7709 (2019).

Özdemir, Ş. K., Rotter, S., Nori, F. & Yang, L. Parity–time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 18, 783–798 (2019).

Kozii, V. & Fu, L. Non-hermitian topological theory of finite-lifetime quasiparticles: Prediction of bulk fermi arc due to exceptional point. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235139 (2024).

Shen, H. & Fu, L. Quantum oscillation from in-gap states and a non-hermitian landau level problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026403 (2018).

Nagai, Y., Qi, Y., Isobe, H., Kozii, V. & Fu, L. DMFT reveals the non-hermitian topology and fermi arcs in heavy-fermion systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 227204 (2020).

Song, F., Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Non-hermitian skin effect and chiral damping in open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 170401 (2019).

Ashida, Y., Gong, Z. & Ueda, M. Non-hermitian physics. Adv. Phys. 69, 249–435 (2020).

Shen, H., Zhen, B. & Fu, L. Topological band theory for non-hermitian hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 146402 (2018).

Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K., Ueda, M. & Sato, M. Symmetry and topology in non-hermitian physics. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041015 (2019).

Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Edge states and topological invariants of non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086803 (2018).

Kunst, F. K., Edvardsson, E., Budich, J. C. & Bergholtz, E. J. Biorthogonal bulk-boundary correspondence in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026808 (2018).

Yao, S., Song, F. & Wang, Z. Non-hermitian chern bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 136802 (2018).

Yokomizo, K. & Murakami, S. Non-bloch band theory of non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 066404 (2019).

Lee, C. H. & Thomale, R. Anatomy of skin modes and topology in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 99, 201103(R) (2019).

Lee, C. H., Li, L. & Gong, J. Hybrid higher-order skin-topological modes in nonreciprocal systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 016805 (2019).

Longhi, S. Probing non-hermitian skin effect and non-bloch phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 023013 (2019).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Fang, C. Correspondence between winding numbers and skin modes in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 126402 (2020).

Okuma, N., Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K. & Sato, M. Topological origin of non-hermitian skin effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 086801 (2020).

Borgnia, D. S., Kruchkov, A. J. & Slager, R.-J. Non-hermitian boundary modes and topology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 056802 (2020).

Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Fang, C. & Hu, J. Non-hermitian bulk-boundary correspondence and auxiliary generalized brillouin zone theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 226402 (2020).

Yi, Y. & Yang, Z. Non-hermitian skin modes induced by on-site dissipations and chiral tunneling effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 186802 (2020).

Xiao, L. et al. Non-Hermitian bulk–boundary correspondence in quantum dynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 761–766 (2020).

Ghatak, A., Brandenbourger, M., van Wezel, J. & Coulais, C. Observation of non-Hermitian topology and its bulk–edge correspondence in an active mechanical metamaterial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29561–29568 (2020).

Helbig, T. et al. Generalized bulk–boundary correspondence in non-Hermitian topolectrical circuits. Nat. Phys. 16, 747–750 (2020).

Li, L., Lee, C. H., Mu, S. & Gong, J. Critical non-hermitian skin effect. Nat. Commun. 11, 5491 (2020).

Kawabata, K., Okuma, N. & Sato, M. Non-bloch band theory of non-hermitian hamiltonians in the symplectic class. Phys. Rev. B 101, 195147 (2020).

Wanjura, C. C., Brunelli, M. & Nunnenkamp, A. Topological framework for directional amplification in driven-dissipative cavity arrays. Nat. Commun. 11, 3149 (2020).

Xue, W.-T., Li, M.-R., Hu, Y.-M., Song, F. & Wang, Z. Simple formulas of directional amplification from non-bloch band theory. Phys. Rev. B 103, L241408 (2021).

Li, L., Mu, S., Lee, C. H. & Gong, J. Quantized classical response from spectral winding topology. Nat. Commun. 12, 5294 (2021).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Fang, C. Universal non-hermitian skin effect in two and higher dimensions. Nat. Commun. 13, 2496 (2022).

Zhang, K., Fang, C. & Yang, Z. Dynamical degeneracy splitting and directional invisibility in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 036402 (2023).

Longhi, S. Self-healing of non-hermitian topological skin modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 157601 (2022).

Hu, Y.-M., Wang, H.-Y., Wang, Z. & Song, F. Geometric origin of non-bloch pt symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 050402 (2024).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Sun, K. Edge theory of non-hermitian skin modes in higher dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 165127 (2024).

Xu, Z., Pang, B., Zhang, K. & Yang, Z. Two-dimensional asymptotic generalized brillouin zone theory. (2024). 2311.16868.

Wang, Y.-C., You, J.-S. & Jen, H. H. A non-hermitian optical atomic mirror. Nat. Commun. 13, 4598 (2022).

Zhou, Q. et al. Observation of geometry-dependent skin effect in non-hermitian phononic crystals with exceptional points. Nat. Commun. 14, 4569 (2023).

Wang, W., Hu, M., Wang, X., Ma, G. & Ding, K. Experimental realization of geometry-dependent skin effect in a reciprocal two-dimensional lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 207201 (2023).

Wan, T., Zhang, K., Li, J., Yang, Z. & Yang, Z. Observation of the geometry-dependent skin effect and dynamical degeneracy splitting. Sci. Bull. 68, 2330–2335 (2023).

Qin, Y., Zhang, K. & Li, L. Geometry-dependent skin effect and anisotropic bloch oscillations in a non-hermitian optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 109, 023317 (2024).

Zhao, E. et al. Two-dimensional non-Hermitian skin effect in an ultracold Fermi gas. Nature 637, 565–573 (2025).

Kondo, J. Resistance Minimum in Dilute Magnetic Alloys. Prog. Theor. Phys. 32, 37–49 (1964).

YU, L. Bound state in superconductors with paramagnetic impurities. Acta. Phys. Sin., 21, 75–91 (1965).

Shiba, H. Classical spins in superconductors. Prog. Theor. Phys. 40, 435–451 (1968).

Rusinov, A. I. Superconcductivity near a paramagnetic impurity 9, 146 http://jetpletters.ru/ps/0/article_25295.shtml (1969).

Li, L., Lee, C. H. & Gong, J. Impurity induced scale-free localization. Commun. Phys. 4, 42 (2021).

Guo, C.-X., Wang, X., Hu, H. & Chen, S. Accumulation of scale-free localized states induced by local non-hermiticity. Phys. Rev. B 107, 134121 (2023).

Hatano, N. & Nelson, D. R. Localization transitions in non-hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 570–573 (1996).

Hatano, N. & Nelson, D. R. Vortex pinning and non-hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. B 56, 8651–8673 (1997).

Fang, Z., Fang, C. & Zhang, K. Point-gap bound states in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 108, 165132 (2023).

Kawabata, K., Sato, M. & Shiozaki, K. Higher-order non-Hermitian skin effect. Phys. Rev. B 102, 205118 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Continuum of bound states in a non-hermitian model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 103602 (2023).

Wen, X.-G. Quantum field theory of many-body systems: from the origin of sound to an origin of light and electrons (OUP Oxford, 2004).

Wang, H.-Y., Song, F. & Wang, Z. Amoeba formulation of non-bloch band theory in arbitrary dimensions. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021011 (2024).

Passare, M. & Tsikh, A. Amoebas: their spines and their contours. Contemp. Math. 377, 275–288 (2005).

Gelfand, I., Kapranov, M. & Zelevinsky, A.Discriminants, Resultants, and Multidimensional Determinants https://books.google.nl/books?id=PC4AswEACAAJ (Birkhäuser Boston, 2013).

Krasikov, V. A. A survey on computational aspects of polynomial amoebas. Math. Comput. Sci. 17, 16 (2023).

Acknowledgements

C.F. acknowledges funding support by the Chinese Academy of Sciences under grant number XDB33020000, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant number 12325404, 12188101, and National Key R&D Program of China under grant number 2022YFA1403800, 2023YFA1406704.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F. conceived the work; A.Y. did the major part of the theoretical derivation and numerical calculation; Z.F. wrote and analyzed the curve equation of weak impurity; K. Z. proposed and analyzed the critical response; All authors discussed the results and participated in the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, A., Fang, Z., Zhang, K. et al. Tailoring bound state geometry in high-dimensional non-hermitian systems. Commun Phys 8, 124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02037-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02037-w