Abstract

Pauli spin blockade (PSB) is a spin-dependent charge transport process that typically appears in double quantum dot (QD) devices and is employed in fundamental research on single spins in nanostructures to read out semiconductor qubits. The operating temperature of PSB is limited by that of the QDs and remains below 10 K, limiting wide application development. Herein, we confirm that a single deep dopant in the channel of a silicon field effect transistor functions as a room-temperature QD; consequently, transport through two different deep dopants exhibits PSB up to room temperature. The characteristic magnetoconductance provides a means to identify PSB and enables the PSB device to function as a magnetic sensor with a sensitivity below geomagnetic field. Lifting in PSB caused by magnetic resonance (50 K) and Rabi oscillations (10 K) are also observed. Further development of this unique system may lead to room-temperature quantum technologies based on silicon technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pauli spin blockade (PSB) is a universal phenomenon observed in the charge transport of double quantum dot (QD) devices1. Owing to Pauli’s exclusion principle, charge transport is blocked by the alignment of the spins of each dot. This has been observed in devices with various materials/structures, such as GaAs1,2,3, carbon nanotubes4,5,6, semiconductor nanowires7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, and Si15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24.

The universality of PSB is attributed to the minimum number of components and the physical conditions (mentioned later) they satisfy1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The building blocks comprise two QDs and source/drain electrodes that are weakly tunnel-coupled in series. The conditions that must be satisfied are as follows: the tunneling causes a charge transport cycle 01-11-02-01… (the first and second numbers indicate the number of charges for each dot), and the confinement strength (quantization level spacing and on-site Coulomb energy) of the dots is sufficiently larger than the thermal energy. According to Pauli’s exclusion principle, the 02-state can take only a spin singlet state; however, the 11-state can take either a spin singlet or triplet state. Thus, charge transport is eventually blocked by the spin-triplet 11-state.

If the spin-triplet states are scattered into (or mixed with) the spin-singlet state, the PSB is lifted, resulting in a finite leakage current. This leakage current facilitates investigating the physics of the dot spin via charge transport. The fluctuations/polarizations of the nuclear spins and spin–orbit interaction (SOI) in the dots have been investigated using the PSB leakage current2,5,7,8,9,10,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29. In particular, a characteristic peak and/or dip structure appears near a region wherein the magnetic field is zero when assessing the magnetic field dependence of the leakage current. Because the PSB is lifted by rotating one of the dot spins using magnetic resonance, the PSB leakage current under magnetic resonance conditions is used as a time-ensemble readout for the spin qubit3,6,8,13,18,19,20.

Conversely, in systems wherein the charge and/or spin states cannot be sufficiently evaluated, observing the aforementioned characteristics facilitates the identification of PSB. PSB has been adopted as a model for the room temperature low-field magnetoresistance effect observed in π-conjugated organic materials30.

Owing to the confinement of QDs (≈5 meV in typical cases1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24), their operating temperature, as well as the operation temperature of PSB for double dot, are typically of the order of 1 K (one order of magnitude smaller thermal energy than the confinement energy). PSB research has largely focused on the integration of QDs at low temperatures, and no research has focused on further improving the operating temperature, except a study by Ono et al. 20, which is explained in the following.

Deep dopants in semiconductors create deep dopant levels in the band gap of the semiconductor, with specific depth in the band gap and a small depth distribution, achieving stronger confinement (typically of order of 0.3 eV, as described subsequently) than those in QDs and/or shallow dopants (order of 10 meV, for P, As, and B)20,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Deep dopants have been used instead of QDs20. An Al-N pair in Si (adjacent Al and N form a single dopant level) was used as a deep dopant. A short-channel tunnel field effect transistor (TFET) structure was adopted to realize the tunneling transport through a deep dopant level. A TFET has an N+ source and P+ drain electrodes and thus forms a planar p-type intrinsic n-type (PIN) structure with a gate electrode. In short-channel TFETs, dopant levels deep in the bandgap can be probed by PIN tunneling current (source–drain current). This type of tunneling current is not possible with ordinary FETs. In this TFET, single-charge tunneling (source–deep dopant–drain) at 1 K up to room temperature (300 K) has been observed. At low temperatures, double-quantum-dot tunneling transport occurs because of the combination of the deep dopant and an unintentionally introduced shallow dopant. PSB was observed up to 10 K, limited by the thermal excitation of the shallow dopant that allows occupation of the 02-state with a spin triplet20. Thus, by replacing the shallow dopant with a deep one, it is expected that PSB will operate at even higher temperatures.

The PSB for the 11-02 charge states is essentially the same as the spin-dependent tunneling of charge from the spin 1/2 donor to the spin 1/2 acceptor. This is because their spin states can accept a singlet or triplet before recombination and only accept a singlet after recombination. Thus, double-quantum-dot tunneling transport through a deep donor and a deep acceptor in series can facilitate the realization of a room-temperature PSB if both the deep donor and deep acceptor have confinement strengths that are sufficiently larger than the room-temperature thermal energy (26 meV).

Group III and V shallow dopants are often referred to as antihydrogen/hydrogen atoms in silicon, whereas Group II and VI dopants can be considered antihelium/helium in silicon. Each of these strongly binds to (up to two) carriers (electrons or holes) even at room temperature. Among these deep dopants, we focused on S and Zn, which have been studied for a long time and are well understood31,32,33,34,35,36,37. S and Zn in Si are known to be thermodynamically stable substitutional dopants. Both of their on-site Coulomb energies are ~0.3 eV31,32,33,34. Both of them also exhibit quantization level spacing of ~0.3 eV for the ground and first excited levels35,36,37. The spin states of their charged states (S+ and Zn−, where the superscript represents the charge state) have been investigated. S+ has spin 1/2 ground states, and Zn− has a nearly degenerate ground state manifold comprising spin 1/2 and spin–orbit 3/2 states38,39. Supplementary Note 1 presents details on the ground and excited states of the S and Zn dopants.

Here, we demonstrated room-temperature PSB in a three-step tunneling process through deep levels of S and Zn dopants in Si. This unique system provides probes for a single deep dopant, particularly its spin and nearby nuclear spins, as well as a technological basis for room-temperature silicon quantum technologies such as magnetic sensors.

Results

PSB in S/Zn-codoped TFET

Figure 1 illustrates the strategy for room-temperature PSB. By using a short-channel TFET (Fig. 1a), we doped S and Zn around the TFET channel. Although the density profiles of these deep dopants were controlled by ion-implantation and post-annealing conditions, the locations of the individual dopants were random, and a TFET device with appropriate dopant locations should be post-selected from many TFET devices fabricated with the same doping conditions. Room-temperature PSB can occur for a three-step percolation-like tunneling through a single S and a single Zn dopant, as depicted in Fig. 1b. As shown in the schematic energy diagram, along with the N+ source electrode, channel, and P+ drain electrode (Fig. 1c), the deep dopant levels for S+ and Zn− are nearly aligned within the transport window of the source/drain electrodes. At the S+ (Zn−) level, a charge transition of the electron (hole) number between zero and one occurs, thus satisfying the aforementioned PSB condition. Because all energy-level spacings (~0.3 eV) are more than 10 times larger than the room-temperature thermal energy (26 meV), the PSB can be observed up to room temperature.

a Schematic of the device based on a cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy image. The gate overlaps the N+/P+ electrodes and defines the effective channel length Leff. BOX: buried oxide. VSD, VG, and ISD contacts for transport characterization and the direction of B are drawn. b S and Zn dopants in the channel and three-step tunneling of electrons from the N+ to the P+ electrode through S and Zn dopants in series. c The same three-step tunneling as that in the p-type intrinsic n-type (PIN) energy band diagram. It shows an S0 level at 0.25 eV below the bottom of the conduction band (CB), an S+ level at 0.5 eV below CB, and Zn dopants levels (Zn0 level of 0.27 eV above the top of the valence band (VB) and Zn− level of 0.62 eV above the VB). These values are obtained using deep-level transient spectroscopy measurements of the S and Zn dopants introduced under the same conditions as that of the device fabrication40. In single charge transport, these are the levels with electron (hole) numbers of 1 and 2, respectively. Tunneling from the S+ level to the Zn− level (or donor–acceptor recombination) is affected by the Pauli spin blockade (PSB). VSD source–drain voltage, VG gate voltage, ISD source–drain current, B magnetic field.

The devices were fabricated within the framework of standard silicon technology, including S and/or Zn (co-)doping. Preliminary research has been conducted for (co-)doping S/Zn into TFETs40, and the same (co-)doping conditions were employed (See Supplementary Note 2). We adopted a structure wherein part of the source/drain electrode overlapped with the gate electrode, thus defining a short effective channel length, Leff (designed to range from 14 to 24 nm). The measurement setup (source–drain voltage VSD, gate voltage VG, source–drain current ISD, and magnetic field B) is shown in Fig. 1a (See “Method” and Supplementary Note 3).

Single-charge tunneling

Figure 2 displays the results of single-charge tunneling. These results were obtained by using devices in which a two-step tunneling (source–deep dopant–drain) dominated the transport. Figure 2a shows the VSD and VG dependence of the differential conductance dISD/dVSD measured at a temperature T of 10 K in a device with only S doped. Coulomb diamonds, characteristic structures for single-charge tunneling, were observed. The width of the diamonds, as observed by VSD, was ~0.25 and 0.5 V. Thus, the charging energy was sufficiently larger than the thermal energy at room temperature. Figure 2b shows a similar plot at room temperature, where Coulomb diamonds were still visible. Figure 2d,e depicts similar measurements performed on devices doped only with Zn. Clear Coulomb diamonds of similar sizes at 10 K and room temperature were observed. The transport models are schematically depicted in Fig. 2c, f.

a Intensity plot of dISD/dVSD versus (VSD, VG) for a TFET with only S doped at T = 10 K. b Similar plot at 300 K. c Energy band diagram showing the two-step tunneling transport through a single S dopant (two levels) existing in the I part (channel) of the p-type intrinsic n-type PIN structure. d, e Similar plots for a TFET with only Zn doped at temperatures of 10 and 300 K. f Schematic of single-charge transport through a single Zn dopant (two levels). The ranges of color intensity scale G (pS) for plots (a, b, d, e) are 50, 50, 500, and 500, respectively. VSD source–drain voltage, VG gate voltage, ISD source–drain current, T temperature.

As shown in Fig. 2c (2f), each S (Zn) dopant had two levels corresponding to electron (hole) numbers 1 and 2, respectively. Single-charge tunneling through these electron (hole) = 2 levels was observed as a second neighboring Coulomb diamond, the size of which reflected the energy difference between the dopant levels for different charge states. In Fig. 2a, the width of the Coulomb diamond observed at VG = 0.5 – 1 V is 0.25 V; this can be interpreted as electron number = 2 diamond. Although the clarity is lower in Fig. 2d than in Fig. 2a, we can interpret hole number = 2 diamond with a width of ~0.3 V at VG = −0.5 – 0 V (further details in Supplementary Note 4). We evaluated several devices with similar Leff values, but without deep dopants. However, Coulomb diamonds (similar to those shown in Fig. 2) have never been observed. These facts indicate that the observed single-charge tunneling in Fig. 2a, d is owing to the single dopants S and Zn, respectively. These facts also form the basis for room-temperature PSB, which we will discuss subsequently.

Single-charge tunneling at room temperature is achieved by various nanostructures41,42. However, because these nanostructures are defined by their surfaces/interface, the smaller the QD, the closer its surfaces/interface. Single-charge tunneling often becomes unstable owing to the influence of trap sites at the surface/interface. Therefore, even if clean single-dot-like behavior is observed at room temperature, these traps behave as unintended QDs at low temperatures, resulting in multiple-quantum-dot characteristics. Conversely, our method shows clean single-dot characteristics at room and low temperatures. This is because the nanostructures are provided by deep dopants in Si and there are no surface/interfaces in their vicinity. This advantage is also utilized in the formation of double QDs, which will be described next.

Zero-B dip structure at 10–300 K

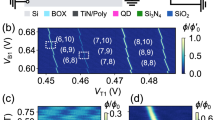

Figure 3a shows the dISD/dVSD intensity plot at 10 K for an S/Zn-codoped TFET, where (as discussed later), three-step tunneling (source–deep dopant 1–deep dopant 2–drain) instead of two-step tunneling dominated the transport. Clear Coulomb diamonds similar to those observed in Fig. 2 were not observed. Instead, the current threshold at 0.2 < VSD < 0.8 V exhibited a zigzag structure with respect to VG. Negative dISD/dVSD values were occasionally observed. These characteristics indicate single-charge tunneling through two (or more) QDs in series. Based on these characteristics, it is difficult to identify the charge/spin states of the dopants involved in the tunneling path. However, if the tunneling path exhibits a PSB, we can expect a characteristic B dependence of the PSB leakage current, ISD peak, and/or dip structure near zero B2,5,7,9,10,11,13,14,15,17,21,22,27,28,29.

a Intensity plot of dISD/dVSD versus (VSD, VG) at T = 10 K. b–e B dependence of ISD observed for a specific (VSD, VG) (see Supplementary Note 5). T = 10, 100, 200, and 300 K for (b–e), respectively. The solid lines represent Lorentzian fits. f Temperature dependence of the dip width (circles, left axis) and signal ratio (normalized change in ISD within the applied range of B, square, and right axis). VSD source–drain voltage, VG gate voltage, ISD source–drain current, T temperature, B magnetic field.

We measured the B dependence of ISD for various sets of (VSD, VG) and observed a zero-B dip structure, as shown in Fig. 3b. This dip structure was maintained up to room temperature under certain (VSD, VG) conditions that kept the transport conditions the same (Fig. 3c–f; further details in Supplementary Note 5). Because of the small signal ratio and large noise at room temperature, the B dependence of ISD was measured repeatedly for 1000 times, and the average was considered. These zero-B dip structures can be fitted with Lorentzian curves predicted by PSB theory under strong SOI conditions28, suggesting a PSB from low temperatures up to room temperature. The room-temperature PSB in this device can be understood using the scheme shown in Fig. 1b, c.

For S/Zn-codoped TFETs with longer Leff, the zigzag structure of the current threshold became modest, and the characteristics approached those of ordinary long-channel TFETs. In these long-channel devices, a zero-B dip structure at room temperature has never been observed. This result supports PSB in the three-step percolation-like tunneling model.

Supplementary Note 6 also presents an S/Zn-codoped TFET in which two-step tunneling dominates.

Zero-B dip and/or peak structures at 300 K

A characteristic zero-B dip (and peak) structure at room temperature was also observed in several other S/Zn-codoped TFETs. Figure 4a shows the zero-B dip structure observed for one of the S/Zn-codoped TFETs with a small ISD of ~10 pA. In addition to the zero-B dip at |B| < 2 mT, a peak envelope with a width of 22 mT was observed. Detailed measurements at ~0.6 mT, at which a steep change of current was observed, are shown in the inset. A magnetic field sensitivity of 20 µT was obtained, which was limited by a current noise of 1 fA. Figure 4b presents the results for another S/Zn-codoped TFET, which also exhibited dip and peak envelopes. The inset shows the detailed measurement near zero B and reveals the smallest dip width (0.26 mT). The results for five other S/Zn-codoped TFETs are shown in Supplementary Note 7).

a B dependence of ISD for another S/Zn TFET. The inset presents the details at ~0.6 mT. b B dependence of ISD for another S/Zn TFET. The inset shows the details of a zero-B structure. The average results of 1000 repeated measurements are shown in (a, b). c Summary of room-temperature zero-B structures. The dip widths obtained for the eight S/Zn-codoped TFETs (circles) and peak envelope widths obtained for the five S/Zn-codoped TFETs (squares) are plotted against their zero-B ISD values. The solid line represents the reference for linear correlation. The dashed line indicates the peak envelope width for the estimated nuclear fluctuation of 26 mT. ISD source–drain current, T temperature, B magnetic field.

We evaluated several dozen S/Zn-codoped TFETs with a similar range of Leff and found that eight devices exhibited room-temperature zero-B structures. Therefore, the device yield for observing zero-B structures was ~10%, which is reasonable considering the random nature of the deep-dopant locations.

We compared the widths of the zero-B dips and peak envelopes observed at room temperature with PSB theory under SOI and nuclear spin fluctuation conditions. The zero-B dip can be explained by coherent spin-flip tunneling induced by SOI28. Furthermore, the zero-B peak of PSB leakage current can be explained by random fluctuations of effective nuclear magnetic fields27. In addition, the coexistence of both was also discussed29. A dip/peak structure without nuclear spin fluctuations has also been discussed10, where a relaxation to the lowest spin triplet state is the origin of the peak envelope. This spin relaxation can be dominant at milli-Kelvin and Tesla regions. However, this condition does not apply in our case (300 K and mT).

As shown in Fig. 4c, an approximately linear correlation is observed over a broad range between the dip widths observed for eight S/Zn-codoped TFETs and their ISD values. This tendency was consistent with the theory28,29 that the dip width is proportional to the tunneling rate between the two QDs (dopants) and ISD. The deviation in the plot for the smallest width toward the high ISD side can be attributed to a small (pA-level) gate leakage current and/or a weak source–drain shunt current superposed onto the ISD.

We estimated the nuclear fluctuations in the S dopant based on a study of nuclear fluctuations in a typical Si QD43. Considering the difference in the confinement strength for a QD (5 meV for in-plane directions and 100 meV in the case of a perpendicular direction to the plane) and the S dopant (300 meV for all directions), we estimated the ratio of their effective volumes to be ~100. This ratio resulted in a nuclear fluctuation of ~26 mT for the S dopant, which agrees with the observed peak envelope widths of 15–30 mT in Fig. 4c (further details in Supplementary Note 8). Nuclear fluctuations for Zn are expected to be similar to, or smaller than, those for S, reflecting the p-orbital nature of the valence band.

Magnetic resonance and Rabi oscillations

Magnetic resonance responses and Rabi oscillations were observed at lower temperatures. The results are summarized in Fig. 5.

a–c Subject to the settings of VSD and VG at which a zero-B dip-peak structure is observed, ISD is measured against B and the frequency (Freq.) of the alternating current magnetic field, and dISD/dB is the plotted intensity. T values for (a–c) are 30, 40, and 50 K, respectively. d Intensity plot of dISD/dl when applying pulse-modulated microwaves (power 10 dBm, pulse period 500 ns, pulse length l = 0–100 ns) at a frequency of 18.65 GHz, T = 10 K. e Pulse-length dependence of the change of ISD (ΔISD) at a resonant magnetic field 547.6 mT, measured at three microwave powers (10, 5, 0 dBm, respectively, offset by 0.1 pA), T = 10 K. VSD source–drain voltage, VG gate voltage, ISD source–drain current, T temperature, B magnetic field, MW microwave.

Figure 5a shows the magnetic resonance characteristics of a S/Zn-codoped TFET observed at 30 K. The VSD and VG were set to the conditions where the zero-B structure was observed (details can be found in Supplementary Note 9), B and the frequency of the alternating current magnetic field were swept, and the change in ISD was intensity plotted. Current peaks due to magnetic resonance were visible at frequencies proportional to B and temperatures up to 50 K (Fig. 5b,c). To the best of our knowledge, this is five times the highest temperature ever reported for a magnetic resonance response detected by PSB20. The obtained g-factor was ~2.0, which is consistent with the magnetic resonance experiment performed on the S+ ensemble in Si38.

Figure 5d shows the pulsed magnetic resonance observed with another S/Zn device wherein microwaves were pulse-modulated, and the change in ISD is plotted against the pulse length (l) and B. Rabi oscillations were visible at a temperature of 10 K. To the best of our knowledge, this temperature of 10 K is the same as the highest temperature reported so far for Rabi oscillations detected by PSB, but the oscillations appear more clearly20. Figure 5e shows the Rabi oscillations under a resonant magnetic field at three different microwave powers. Further details can be found in Supplementary Note 9.

These results provide clear evidence for PSB. However, these PSBs, observed only at low temperatures, are thought to be caused not by the combination of deep dopants alone, but by a combination of deep and shallow dopants20. At higher temperatures (>50 K), the occupation of the 02-state with a spin triplet is allowed for shallow dopants, and the low-temperature PSB is lifted. We emphasize that the above room temperature PSB is due to the combination of deep dopants, S and Zn, and not due to shallow dopants.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, PSB is the only mechanism that can explain the room temperature zero-B structures. Although the weak localization effect is known to show zero-B dip (or peak) for metallic semiconductors at low temperature, it cannot explain our observations. Weak localization is a quantum interference effect from electron (or hole) orbits in “localization loops” formed by multiple scattering by impurities. If the zero-B dip with a width of 1.5 mT (observed at room temperature) is due to weak localization, the diameter of the localized loop would be as large as 3 µm. It is inconceivable that a loop of this size would exhibit quantum interference effects at room temperature, and there is no room in the device channel to accommodate such a loop.

Although the zero-B structures were observed up to room temperature, the magnetic resonance response was not. Magnetic resonance response was not observed in the device shown in Fig. 3 at 10–300 K, or in the devices shown in Fig. 4 at 300 K. The reasons for the missing magnetic resonance response, strong SOI-induced spin-flip tunnels from the triplet 11-state to the 02 state, and/or PSB including spin–orbit 3/2 states of Zn− are discussed in Supplementary Note 10. Magnetic resonance at room temperature is expected to pave the way for room-temperature qubits, such as those used in sensors with diamond nitrogen-vacancy centers.

The magnetic field sensitivity of 20 µT (inset of Fig. 4a) indicates that this device can be potentially used as a sensor capable of detecting geomagnetism (~50 μT). As it is a sensor based on strongly localized spins, it has a potential for high-spatial resolution limited by the size of the deep dopant. Because the device yield is limited, as mentioned above, this device is more suitable for individual applications, such as sensors, rather than for integrated systems. Moreover, as it can be fabricated using existing silicon technology, it holds potential for industrial applications. We reserve the analysis of the noise spectral-density (in units of μT/√Hz) based on time-series data for the future (see Supplementary Note 11).

Organic semiconductors can be viewed as random networks consisting of a macroscopic number of QDs, and the PSBs in the tunneling between various QD pairs are assumed to be the origin of the room temperature magnetoresistance effect30. By contrast, it is to be noted that our room-temperature PSB devices exhibit percolation conduction based on the use of only two QDs (dopants). The former deals with the statistical average of PSBs in a collective system, whereas the latter deals with PSBs in a single dopant pair. This was achieved by the established manufacturing process for silicon at the nanometer scale, established physics of single-charge tunneling, and evaluation methods based on it. The non-ensemble nature of our system is manifested in the ISD dependence of the zero-B dip width, as discussed in Fig. 4c. The ISD corresponds to the tunneling rate, i.e., the distance between dopant pairs, and changes in zero-B structure depending on this distance are illustrated. These non-ensemble results enable discussion of the effects of SOI and nuclear spin fluctuations separately. These results cannot be observed in an ensemble system with various QD-pair distances. Furthermore, theory28,29 predicts a “magic direction” for the magnetic field at which the zero-B dip structure disappears. This direction is related to an effective SOI magnetic field for a particular dopant pair. It would be difficult to observe this magic direction in the ensemble system where the effective SOI magnetic field is randomly distributed for various QD pairs. To the best of our knowledge, no magnetic field direction has been reported in which the zero-B structure disappears in the magnetoresistance effect of organic semiconductors. Observing the magic direction in our system would be interesting future work.

An obvious limitation of this system is that the location of the deep dopant cannot be individually controlled. Atomic-level positional control of these deep dopants would remove the aforementioned limitations in applications of this system. Because the origin of the zero-B dip is a coherent superposition of the spin states (further details can be found in Supplementary Note 12)28,29 S/Zn-codoped TFETs can be considered quantum functional devices.

Methods

The device manufacturing process involved the formation of N+ and P+ electrodes, followed by the introduction of S and/or Zn dopants over the entire surface of the wafer, including the part that would later become the TFET channel. The gate stack was formed after this. Electron beam lithography was used to pattern the source, drain, and gate electrodes (Supplementary Note 3 presents further details). Four different (co-) doping conditions for deep dopants were adopted (only S, only Zn, S and Zn, and no deep dopant). The first two conditions were used for single-charge tunneling through a single species of deep dopant, the third condition was used for PSB for temperatures up to room temperature, and the fourth condition was used to confirm that the phenomenon described above does not occur in the absence of the deep dopants. The TFET channel must be sufficiently short to observe tunneling through deep dopant levels44. To realize a short channel within the scope of our process technology, we adopted a structure wherein part of the source/drain electrode overlapped the gate electrode, as shown in Fig. 1a, defining an effective channel length, Leff. For the 13 devices introduced in this study, Leff was designed to range from 14 to 24 nm (Supplementary Table 1).

The transport characteristics of the device were evaluated following the standard three-terminal transistor evaluation procedure. A source–drain voltage VSD was applied to the P+ electrode of the device, a gate voltage VG was applied to the gate electrode, and the source–drain current ISD at the N+ electrode was measured. For magnetic field B, a superconducting magnet was used for measurements at temperatures below 250 K, and a solenoid or split electromagnet was used at room temperature (300 K). Furthermore, B was applied along the in-plane source–drain direction (crystal orientation <110>). For the alternating magnetic field at low-B resonance, an alternating current was applied to a coil (five turns of diameter 1 mm) installed 1 mm above the device substrate. To realize a high-B, microwaves were used to apply an alternating current to the backplate of the device substrate20.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Ono, K., Austing, D. G., Tokura, Y. & Tarucha, S. Current rectification by Pauli exclusion in a weakly coupled double quantum dot system. Science 297, 1313–1317 (2002).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Control and detection of singlet-triplet mixing in a random nuclear field. Science 309, 1346–1350 (2005).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Driven coherent oscillations of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 442, 766–771 (2006).

Buitelaar, M. R. et al. Pauli spin blockade in carbon nanotube double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 77, 245439 (2008).

Churchill, H. O. H. et al. Electron–nuclear interaction in 13C nanotube double quantum dots. Nat. Phys. 5, 321–326 (2009).

Pei, F., Laird, E. A., Steele, G. A. & Kouwenhoven, L. P. Valley–spin blockade and spin resonance in carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 630–634 (2012).

Pfund, A., Shorubalko, I., Ensslin, K. & Leturcq, R. Suppression of spin relaxation in an InAs nanowire double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 036801 (2007).

Nadj-Perge, S., Frolov, S. M., Bakkers, E. P. A. M. & Kouwenhoven, L. P. Spin-orbit qubit in a semiconductor nanowire. Nature 468, 1084–1087 (2010).

Brauns, M. et al. Anisotropic Pauli spin blockade in hole quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 94, 041411 (2016).

Zarassi, A. et al. Magnetic field evolution of spin blockade in Ge/Si nanowire double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 95, 155416 (2017).

Wang, J.-Y. et al. Anisotropic Pauli spin-blockade effect and spin-orbit interaction field in an InAs nanowire double quantum dot. Nano Lett. 18, 4741–4747 (2018).

Froning, F. N. M. et al. Strong spin-orbit interaction and g-factor renormalization of hole spins in Ge/Si nanowire quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013081 (2021).

Xu, G. et al. Hole spin in tunable Ge hut wire double quantum dot. Appl. Phys. Express 13, 065002 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Gate-tunable spin-orbit coupling in a germanium hole double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 044052 (2022).

Lai, N. S. et al. Pauli spin blockade in a highly tunable silicon double quantum dot. Sci. Rep. 1, 110 (2011).

Weber, B. et al. Spin blockade and exchange in Coulomb-confined silicon double quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 430–435 (2014).

Li, R., Hudson, F. E., Dzurak, A. S. & Hamilton, A. R. Pauli spin blockade of heavy holes in a silicon double quantum dot. Nano Lett. 15, 7314–7318 (2015).

Maurand, R. et al. A CMOS silicon spin qubit. Nat. Commun. 7, 13575 (2016).

Ono, K. et al. Hole spin resonance and spin-orbit coupling in a silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 156802 (2017).

Ono, K., Mori, T. & Moriyama, S. High-temperature operation of a silicon qubit. Sci. Rep. 9, 469 (2019).

Wei, H., Mizoguchi, S., Mizokuchi, R. & Kodera, T. Estimation of hole spin g-factors in p-channel silicon single and double quantum dots towards spin manipulation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SGGI10 (2020).

Geyer, S. et al. Self-aligned gates for scalable silicon quantum computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 104004 (2021).

Seedhouse, A. E. et al. Pauli blockade in silicon quantum dots with spin-orbit control. PRX Quantum 2, 010303 (2021).

Lundberg, T. et al. Non-symmetric Pauli spin blockade in a silicon double quantum dot. NPJ Quantum Inf. 10, 28 (2024).

Ono, K. & Tarucha, S. Nuclear-spin-induced oscillatory current in spin-blockaded quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 256803 (2004).

Baugh, J., Kitamura, Y., Ono, K. & Tarucha, S. Large nuclear Overhauser fields detected in vertically-coupled double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 096804 (2007).

Jouravlev, O. N. & Nazarov, Y. V. Electron transport in a double quantum dot governed by a nuclear magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 176804 (2006).

Danon, J. & Nazarov, Y. V. Pauli spin blockade in the presence of strong spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 80, 041301 (2009).

Qvist, J. H. & Danon, J. Probing details of spin-orbit coupling through Pauli spin blockade. Phys. Rev. B 106, 235312 (2022).

Danon, J., Wang, X. & Manchon, A. Pauli spin blockade and the ultrasmall magnetic field effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 066802 (2013).

Kleverman, M., Grimmeiss, H. G., Litwin, A. & Janzén, E. Capture processes at double donors in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 31, 3659–3666 (1985).

Gwozdz, K., Kolkovsky, V., Weber, J., Yakovleva, A. A. & Astrov, Y. A. Detection of sulfur-related defects in sulfur diffused n- and p-type Si by DLTS.Phys. Status Solidi (A) 216, 1900303 (2019).

Wang, A. C., Lu, L. S. & Sah, C. T. Electron capture at the two acceptor levels of a zinc center in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 30, 5896–5903 (1984).

Weiss, S., Beckmann, R. & Kassing, R. The electrical properties of zinc in silicon. Appl. Phys. A 50, 151–156 (1990).

Steger, M. et al. J. W. High-resolution absorption spectroscopy of the deep impurities S and Se in 28Si revealing the 77Se hyperfine splitting. Phys. Rev. B 80, 115204 (2009).

Merk, E., Heyman, J. & Haller, E. E. Infrared absorption study of zinc-doped silicon. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 163, 15 (1989).

Suezawa, M. & Mori, R. Optical absorption study of the interaction between group II acceptors and hydrogen in Si. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 210, 507–511 (1998).

Ludwig, G. W. Paramagnetic resonance study of a deep donor in silicon. Phys. Rev. 137, A1520–A1530 (1965).

Schroth, H., Laßmann, K., Voß, S. & Bracht, H. Extreme reduction of the spin-orbit splitting of the deep acceptor ground state of ZnS− in Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 417–420 (2000).

Ban, Y. et al. Introduction of deep level impurities, S, Se, and Zn, into Si wafers for high-temperature operation of a Si qubit. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 62, SC1054 (2023).

Takahashi, Y. et al. Fabrication technique for Si single-electron transistor operating at room temperature. Electron. Lett. 31, 136–137 (1995).

Postma, H. W. C., Teepen, T., Yao, Z., Grifoni, M. & Dekker, C. Carbon nanotube single-electron transistors at room temperature. Science 293, 76–79 (2001).

Assali, L. V. C. et al. Hyperfine interactions in silicon quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 83, 165301 (2011).

Iizuka, S. et al. Mechanism of extraordinary gate-length dependence of quantum dot operation in isoelectronic-trap-assisted tunnel FETs. Appl. Phys. Express 13, 114001 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Abe, M. Kawamura, J. Yoneda, and T. Tanamoto for their discussions. This work was partly supported by JST CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR1871), MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (Q-LEAP) (Grant No. JPMXS0118069228), and by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 15H05867).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: K.O.; Methodology: Y.B., K.K., S.I., H.K., S.Mu., T.M.; Investigation: Y.B., S.Mo., K.I., K.O.; Visualization: Y.B., K.O.; Funding acquisition: K.I., T.M., K.O.; Project administration: K.O.; Supervision: T.M., K.O.; Writing—original draft: K.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ban, Y., Kato, K., Iizuka, S. et al. Pauli spin blockade at room temperature in double-quantum-dot tunneling through individual deep dopants in silicon. Commun Phys 8, 293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02177-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02177-z