Abstract

Hexokinase (HK) catalyses the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate, marking the first step of glucose metabolism. Most cancer cells co-express two homologous HK isoforms, HK1 and HK2, which can each bind the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). CRISPR screens performed across hundreds of cancer cell lines indicate that both isoforms are dispensable for growth in conventional culture media. By contrast, HK2 deletion impaired cell growth in human plasma-like medium. Here we show that this conditional HK2 dependence can be traced to the subcellular distribution of HK1. Notably, OMM-detached (cytosolic) rather than OMM-docked HK supports cell growth and aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), an enigmatic phenotype of most proliferating cells. We show that under conditions promoting increased translocation of HK1 to the OMM, HK2 is required for cytosolic HK activity to sustain this phenotype, thereby driving sufficient glycolytic ATP production. Our results reveal a basis for conditional HK2 essentiality and suggest that demand for compartmentalized ATP synthesis explains why cells engage in aerobic glycolysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the findings of this study can be found within the Article, Extended Data or Supplementary Information. The individual plasmids generated in this study have been deposited in Addgene (identifiers found in Supplementary Table 5). Unique reagents generated in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Identifiers for deposited datasets accessed in this study are found in Supplementary Table 5. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

This paper does not report original code.

References

Rancati, G., Moffat, J., Typas, A. & Pavelka, N. Emerging and evolving concepts in gene essentiality. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 34–49 (2017).

Tsherniak, A. et al. Defining a cancer dependency map. Cell 170, 564–576.e16 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Gene essentiality profiling reveals gene networks and synthetic lethal interactions with oncogenic Ras. Cell 168, 890–903.e15 (2017).

Wainberg, M. et al. A genome-wide atlas of co-essential modules assigns function to uncharacterized genes. Nat. Genet. 53, 638–649 (2021).

Shi, H., Doench, J. G. & Chi, H. CRISPR screens for functional interrogation of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 363–380 (2023).

Hart, T. et al. High-resolution CRISPR screens reveal fitness genes and genotype-specific cancer liabilities. Cell 163, 1515–1526 (2015).

Meyers, R. M. et al. Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR–Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat. Genet. 49, 1779–1784 (2017).

Behan, F. M. et al. Prioritization of cancer therapeutic targets using CRISPR–Cas9 screens. Nature 568, 511–516 (2019).

Han, K. et al. CRISPR screens in cancer spheroids identify 3D growth-specific vulnerabilities. Nature 580, 136–141 (2020).

Jain, I. H. et al. Genetic screen for cell fitness in high or low oxygen highlights mitochondrial and lipid metabolism. Cell 181, 716–727.e11 (2020).

Michl, J. et al. CRISPR–Cas9 screen identifies oxidative phosphorylation as essential for cancer cell survival at low extracellular pH. Cell Rep. 38, 110493 (2022).

Rossiter, N. J. et al. CRISPR screens in physiologic medium reveal conditionally essential genes in human cells. Cell Metab. 33, 1248–1263.e9 (2021).

Cantor, J. R. The rise of physiologic media. Trends Cell Biol. 29, 854–861 (2019).

Cantor, J. R. et al. Physiologic medium rewires cellular metabolism and reveals uric acid as an endogenous inhibitor of UMP synthase. Cell 169, 258–272.e17 (2017).

Vander Heiden, M. G., Cantley, L. C. & Thompson, C. B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033 (2009).

Liberti, M. V. & Locasale, J. W. The Warburg effect: How does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 211–218 (2016).

DeBerardinis, R. J. & Chandel, N. S. We need to talk about the Warburg effect. Nat. Metab. 2, 127–129 (2020).

Li, Z., Munim, M. B., Sharygin, D. A., Bevis, B. J. & Vander Heiden, M. G. Understanding the Warburg effect in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041532 (2024).

Wilson, J. E. Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: structure, subcellular localization and metabolic function. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 2049–2057 (2003).

Zapater, J. L., Lednovich, K. R., Khan, Md W., Pusec, C. M. & Layden, B. T. Hexokinase domain-containing protein-1 in metabolic diseases and beyond. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 72–84 (2022).

Ghandi, M. et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569, 503–508 (2019).

Ardehali, H. et al. Functional organization of mammalian hexokinase II. Retention of catalytic and regulatory functions in both the NH2- and COOH-terminal halves. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1849–1852 (1996).

Ferreira, J. C. et al. Linker residues regulate the activity and stability of hexokinase 2, a promising anticancer target. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100071 (2021).

Sui, D. & Wilson, J. E. Structural determinants for the intracellular localization of the isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: intracellular localization of fusion constructs incorporating structural elements from the hexokinase isozymes and the green fluorescent protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 345, 111–125 (1997).

Sun, L., Shukair, S., Naik, T. J., Moazed, F. & Ardehali, H. Glucose phosphorylation and mitochondrial binding are required for the protective effects of hexokinases I and II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 1007–1017 (2008).

Pastorino, J. G. & Hoek, J. B. Regulation of hexokinase binding to VDAC. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 171–182 (2008).

Arora, K. K. & Pedersen, P. L. Functional significance of mitochondrial bound hexokinase in tumor cell metabolism. Evidence for preferential phosphorylation of glucose by intramitochondrially generated ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17422–17428 (1988).

John, S., Weiss, J. N. & Ribalet, B. Subcellular localization of hexokinases I and II directs the metabolic fate of glucose. PLoS ONE 6, e17674 (2011).

De Jesus, A. et al. Hexokinase 1 cellular localization regulates the metabolic fate of glucose. Mol. Cell 82, 1261–1277.e9 (2022).

Pastorino, J. G., Shulga, N. & Hoek, J. B. Mitochondrial binding of hexokinase II inhibits Bax-induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7610–7618 (2002).

Majewski, N. et al. Hexokinase–mitochondria interaction mediated by Akt is required to inhibit apoptosis in the presence or absence of Bax and Bak. Mol. Cell 16, 819–830 (2004).

Abu-Hamad, S., Zaid, H., Israelson, A., Nahon, E. & Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Hexokinase-I protection against apoptotic cell death is mediated via interaction with the voltage-dependent anion channel-1: mapping the site of binding. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13482–13490 (2008).

Blaha, C. S. et al. A non-catalytic scaffolding activity of hexokinase 2 contributes to EMT and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 13, 899 (2022).

Pilic, J. et al. Hexokinase 1 forms rings that regulate mitochondrial fission during energy stress. Mol. Cell 84, 2732–2746.e5 (2024).

Palma, F., Longhi, S., Agostini, D. & Stocchi, V. One-step purification of a fully active hexahistidine-tagged human hexokinase type I overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 22, 38–44 (2001).

DeWaal, D. et al. Hexokinase-2 depletion inhibits glycolysis and induces oxidative phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma and sensitizes to metformin. Nat. Commun. 9, 446 (2018).

Pastorino, J. G., Hoek, J. B. & Shulga, N. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β disrupts the binding of hexokinase II to mitochondria by phosphorylating voltage-dependent anion channel and potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 65, 10545–10554 (2005).

Wang, H. et al. Organization of a functional glycolytic metabolon on mitochondria for metabolic efficiency. Nat. Metab. 6, 1712–1735 (2024).

Roberts, D. J., Tan-Sah, V. P., Smith, J. M. & Miyamoto, S. Akt Phosphorylates HK-II at Thr-473 and increases mitochondrial HK-II association to protect cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 23798–23806 (2013).

Quach, C. H. T. et al. Mild alkalization acutely triggers the Warburg effect by enhancing hexokinase activity via voltage-dependent anion channel binding. PLoS ONE 11, e0159529 (2016).

Chen, W. W., Freinkman, E., Wang, T., Birsoy, K. & Sabatini, D. M. Absolute quantification of matrix metabolites reveals the dynamics of mitochondrial metabolism. Cell 166, 1324–1337.e11 (2016).

Kanaji, S., Iwahashi, J., Kida, Y., Sakaguchi, M. & Mihara, K. Characterization of the signal that directs Tom20 to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Cell Biol. 151, 277–288 (2000).

Finley, L. W. S. What is cancer metabolism? Cell 186, 1670–1688 (2023).

Koppenol, W. H., Bounds, P. L. & Dang, C. V. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 325–337 (2011).

Bustamante, E., Morris, H. P. & Pedersen, P. L. Energy metabolism of tumor cells. Requirement for a form of hexokinase with a propensity for mitochondrial binding. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 8699–8704 (1981).

Mathupala, S. P., Ko, Y. H. & Pedersen, P. L. Hexokinase-2 bound to mitochondria: cancer’s stygian link to the “Warburg effect” and a pivotal target for effective therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 19, 17–24 (2009).

Wolf, A. et al. Hexokinase 2 is a key mediator of aerobic glycolysis and promotes tumor growth in human glioblastoma multiforme. J. Exp. Med. 208, 313–326 (2011).

Intlekofer, A. M. & Finley, L. W. S. Metabolic signatures of cancer cells and stem cells. Nat. Metab. 1, 177–188 (2019).

Cantor, J. R. & Sabatini, D. M. Cancer cell metabolism: one hallmark, many faces. Cancer Discov. 2, 881–898 (2012).

Halestrap, A. P. & Wilson, M. C. The monocarboxylate transporter family—role and regulation. IUBMB Life 64, 109–119 (2012).

Rabinowitz, J. D. & Enerbäck, S. Lactate: the ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2, 566–571 (2020).

Hong, C. S. et al. MCT1 modulates cancer cell pyruvate export and growth of tumors that co-express MCT1 and MCT4. Cell Rep. 14, 1590–1601 (2016).

Jain, M. et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science 336, 1040–1044 (2012).

Luengo, A. et al. Increased demand for NAD+ relative to ATP drives aerobic glycolysis. Mol. Cell 81, 691–707.e6 (2021).

Brand, K. A. & Hermfisse, U. Aerobic glycolysis by proliferating cells: a protective strategy against reactive oxygen species. FASEB J. 11, 388–395 (1997).

Movahed, Z. G., Rastegari-Pouyani, M., Mohammadi, M. H. & Mansouri, K. Cancer cells change their glucose metabolism to overcome increased ROS: One step from cancer cell to cancer stem cell? Biomed. Pharmacother. 112, 108690 (2019).

Schell, J. C. et al. A role for the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier as a repressor of the Warburg effect and colon cancer cell growth. Mol. Cell 56, 400–413 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier function is negatively linked to Warburg phenotype in vitro and malignant features in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Oncotarget 8, 1058–1073 (2016).

Yang, C. et al. Glutamine oxidation maintains the TCA cycle and cell survival during impaired mitochondrial pyruvate transport. Mol. Cell 56, 414–424 (2014).

Vacanti, N. M. et al. Regulation of substrate utilization by the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Mol. Cell 56, 425–435 (2014).

Molenaar, D., van Berlo, R., de Ridder, D. & Teusink, B. Shifts in growth strategies reflect tradeoffs in cellular economics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, MSB200982 (2009).

Basan, M. et al. Overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli results from efficient proteome allocation. Nature 528, 99–104 (2015).

Kukurugya, M. A., Rosset, S. & Titov, D. V. The Warburg effect is the result of faster ATP production by glycolysis than respiration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2409509121 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Mitochondrial ATP generation is more proteome efficient than glycolysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1123–1132 (2024).

Marroquin, L. D., Hynes, J., Dykens, J. A., Jamieson, J. D. & Will, Y. Circumventing the Crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol. Sci. 97, 539–547 (2007).

Reddan, B. & Cummins, E. P. The regulation of cell metabolism by hypoxia and hypercapnia. J. Biol. Chem. 301, 108252 (2025).

Jin, H. et al. Systematic transcriptional analysis of human cell lines for gene expression landscape and tumor representation. Nat. Commun. 14, 5417 (2023).

Bosshart, P. D., Charles, R.-P., Garibsingh, R.-A. A., Schlessinger, A. & Fotiadis, D. SLC16 family: from atomic structure to human disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 46, 28–40 (2021).

Doherty, J. R. et al. Blocking lactate export by inhibiting the Myc target MCT1 disables glycolysis and glutathione synthesis. Cancer Res. 74, 908–920 (2014).

Faubert, B. et al. Lactate metabolism in human lung tumors. Cell 171, 358–371.e9 (2017).

Contreras-Baeza, Y. et al. Monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4) is a high affinity transporter capable of exporting lactate in high-lactate microenvironments. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 20135–20147 (2019).

Lonsdale, J. et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 45, 580–585 (2013).

Patra, K. C. et al. Hexokinase 2 is required for tumor initiation and maintenance and its systemic deletion is therapeutic in mouse models of cancer. Cancer Cell 24, 213–228 (2013).

Shan, W., Zhou, Y. & Tam, K. Y. The development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting hexokinase 2. Drug Discov. Today 27, 2574–2585 (2022).

Lin, H. et al. Discovery of a novel 2,6-disubstituted glucosamine series of potent and selective hexokinase 2 inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7, 217–222 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Benserazide, a dopadecarboxylase inhibitor, suppresses tumor growth by targeting hexokinase 2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 36, 58 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Structure based discovery of novel hexokinase 2 inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 96, 103609 (2020).

Zheng, M. et al. Novel selective hexokinase 2 inhibitor benitrobenrazide blocks cancer cells growth by targeting glycolysis. Pharmacol. Res. 164, 105367 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Hexokinase 2-mediated Warburg effect is required for PTEN- and p53-deficiency-driven prostate cancer growth. Cell Rep. 8, 1461–1474 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. Hexokinase 2 (HK2), the tumor promoter in glioma, is downregulated by miR-218/Bmi1 pathway. PLoS ONE 12, e0189353 (2017).

Anderson, M., Marayati, R., Moffitt, R. & Yeh, J. J. Hexokinase 2 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by regulating lactate production in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 8, 56081–56094 (2016).

Liu, W., Li, W., Liu, H. & Yu, X. Xanthohumol inhibits colorectal cancer cells via downregulation of Hexokinases II-mediated glycolysis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 15, 2497–2508 (2019).

Galluzzi, L., Kepp, O., Tajeddine, N. & Kroemer, G. Disruption of the hexokinase–VDAC complex for tumor therapy. Oncogene 27, 4633–4635 (2008).

Gaetani, M. et al. Proteome integral solubility alteration: a high-throughput proteomics assay for target deconvolution. J. Proteome Res. 18, 4027–4037 (2019).

Campos, M. & Albrecht, L. V. Hitting the sweet spot: how glucose metabolism is orchestrated in space and time by phosphofructokinase-1. Cancers (Basel) 16, 16 (2023).

Lee, J.-H. et al. Stabilization of phosphofructokinase 1 platelet isoform by AKT promotes tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 8, 949 (2017).

Huang, Y. et al. p53-Responsive CMBL reprograms glucose metabolism and suppresses cancer development by destabilizing phosphofructokinase PFKP. Cell Rep. 42, 113426 (2023).

Tanner, L. B. et al. Four key steps control glycolytic flux in mammalian cells. Cell Syst. 7, 49–62.e8 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Saturation of the mitochondrial NADH shuttles drives aerobic glycolysis in proliferating cells. Mol. Cell 82, 3270–3283.e9 (2022).

Chen, P.-H. et al. Metabolic diversity in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell 76, 838–851.e5 (2019).

Hardie, D. G. 100 years of the Warburg effect: a historical perspective. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 29, T1–T13 (2022).

Fuller, G. G. & Kim, J. K. Compartmentalization and metabolic regulation of glycolysis. J. Cell Sci. 134, jcs258469 (2021).

Zhan, H. et al. Self-organizing glycolytic waves tune cellular metabolic states and fuel cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 16, 5563 (2025).

Han, J. W., Thieleczek, R., Varsanyi, M. & Heilmeyer, L. M. G. Compartmentalized ATP synthesis in skeletal muscle triads. Biochemistry 31, 377–384 (1992).

Zala, D. et al. Vesicular glycolysis provides on-board energy for fast axonal transport. Cell 152, 479–491 (2013).

De Bock, K. et al. Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 154, 651–663 (2013).

Kelley, L. C. et al. Adaptive F-actin polymerization and localized ATP production drive basement membrane invasion in the absence of MMPs. Dev. Cell 48, 313–328.e8 (2019).

Ho, T., Potapenko, E., Davis, D. B. & Merrins, M. J. A plasma membrane-associated glycolytic metabolon is functionally coupled to KATP channels in pancreatic α and β cells from humans and mice. Cell Rep. 42, 112394 (2023).

Shuler, M. L., Mufti, N., Donaldson, M. & Tatick, R. A bioreactor experiment for the senior laboratory. Chem. Eng. Educ. 28, 24–28 (1994).

Su, X., Lu, W. & Rabinowitz, J. D. Metabolite spectral accuracy on Orbitraps. Anal. Chem. 89, 5940–5948 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Cantor Lab for upkeep of both the LC–MS system and cell sorter and for helpful discussions, and members of the J. Fan Lab for training and helpful tips on using the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer. We also thank M. Stefely for organelle figure assets, K. Tharp and D. M. Sabatini for helpful comments on the manuscript and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Small Animal Imaging and Radiotherapy Facility (supported in part through NCI/NIH P30CA014520) for use of its facilities and services. This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society (RSG-21-170-01-TBE to J.R.C.), the St. Baldrick’s Foundation Empowering Pediatric Immunotherapy for Childhood Cancers Team Grant (to C.M.C.) and the Midwest Athletes Against Childhood Cancer (MACC) Fund (to M.H.F. and C.M.C.). Fellowship support was provided by the NIH (T32HG002760 to K.S.H.) and the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Biochemistry to K.S.H., K.M.F. and G.R.C. J.R.C. is a Hartwell Foundation Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.H. and J.R.C. initiated the project and designed the research plan. K.S.H. performed most of the experiments, with assistance from C.A.M.F., G.R.C. and M.F.M. K.M.F. performed coupled HK-G6PD activity and differential centrifugation experiments. J.R.C. performed a subset of the growth assay, growth curve and metabolomics experiments. M.H.F. performed the xenograft and bioluminescence imaging experiments with supervision from C.M.C. K.S.H. and J.R.C. analysed and interpreted the experimental data, with assistance from K.M.F. J.R.C. wrote the manuscript with assistance from K.S.H. All authors discussed the manuscript. J.R.C. supervised the studies.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.R.C. is an inventor on an issued patent for HPLM assigned to the Whitehead Institute (Patent number US11453858). C.M.C. reports honorarium from Bayer and Novartis, and equity interest from Elephas, for advisory board memberships. These entities had no input in the study design, analysis, manuscript preparation or decision to submit for publication. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Metabolism thanks Marteinn Snaebjornsson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Yanina-Yasmin Pesch and Alfredo Gimenez-Cassina, in collaboration with the Nature Metabolism team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Related to HK2 deletion impairs cell growth in HPLM and reduces in vivo tumor burden.

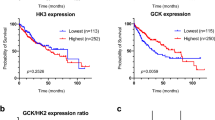

(a) Human cell lines ranked by probability of dependency values for HK2 across CRISPR screen data cataloged in the DepMap9. Probability > 0.5 is the reference threshold for essentiality. (b) Dependency phenotypes for HK3, GCK, and HKDC1 from conditional essentiality profiling in K562 cells14 (top) and the DepMap project (bottom)9. c) Immunoblots for expression of HK1 and HK2 in K562 cells. GAPDH served as the loading control in both cases. (d) Images depicting leukemia tumor burden based on Akaluciferase flux in mice engrafted with HK2-knockout K562 cells that either harbored empty vector (EV) (left) or expressed an HK2 cDNA (right). Data are represented colorimetrically with the scale bars depicted.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Related to HK2-mediated catalytic activity is necessary to support cell growth in HPLM.

(a) Pseudocolor Coomassie-stained gel imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey FC. 1: M.W. standards; 2: wild-type HK2-3xFLAG; 3: HK2 (D209A, D657A)-3xFLAG. (b) Schematic for a method to evaluate HK activity based on glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) production from reactions containing recombinant HK2.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Related to relative HK1-OMM binding varies with nutrient conditions and HK detachment from the OMM promotes cell growth.

(a) Immunoblots for expression of HK2 in whole-cell lysates (WC) and mitochondria isolated (IP:HA) from K562 cells that expressed 3xMyc-eGFP-OMP25 (Control-MITO) or 3xHA-eGFP-OMP25 (HA-MITO). COXIV served as a mitochondrial loading control for HK1 (immunoblot displayed in Fig. 3a) and HK2 (immunoblot displayed in this panel) from the same samples. Immunoblot for expression of HK2 is identical to that displayed in Fig. 3a. (b) HK signal normalized by COXIV signal in IP:HA versus WC from the same respective cells. nd, not detected. Comparison of normalized signals between HK1 and HK2 is derived by using the same experimental samples run across different blots and processed in parallel. (c, i, m) Immunoblots for expression of HK1 and HK2 (c) or Flag (i, m) in dounce homogenates (DH) and corresponding cytosolic (Cyt) and organellar (Org) fractions isolated from HK2-knockout cells. GAPDH served as cytosolic control marker. COXIV served as a mitochondrial control marker. (d, j) HK (d) or Flag (j) signal normalized by COXIV signal in Org versus DH from the same respective cells. Comparisons of normalized signal between HK1 and HK2 are derived using the same experimental samples run across different blots and processed in parallel (d). Comparisons of normalized signal are derived from samples run on the same blot (j). (e, f, k, l) Immunoblots for expression of Flag (e, g), HK1 (e), or HK2 (f, k, l) in HK2-knockout and control cells. GAPDH served as the loading control in each case. (g) Immunoblot for expression of Flag in WC and IP:HA from HK2-knockout cells that expressed HA-MITO. COXIV served as a mitochondrial control marker. S6K served as a non-mitochondrial control marker. (h) HK1 (mean ± s.d., n = 3) or Flag signal normalized by COXIV signal in IP:HA versus WC from the same respective cells. P value, Two-tailed Welch’s t-test between the indicated bars identical to that displayed in Fig. 3c. For comparisons involving normalized Flag signal, MBD-deficient HK1 and MBD-deficient HK2 samples were run on the same blot. Wild-type HK1 samples were run on a different blot and were processed on a separate day. (n) Pseudocolor Coomassie-stained gel imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey FC. 1: TOM20-HK2-3xFLAG; 2: M.W. standards. HK1 signal normalized by COXIV signal in IP:HA versus WC from the same respective cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent samples). (o) G6P levels measured from reactions of recombinant TOM20-HK2 with glucose and ATP (mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent reactions). (p) Immunoblots for expression of HK1 and HK2 from HK2-knockout and control cells used for lysate-based HK activity assays. GAPDH served as the loading control in both cases. (q) Relative growth of HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. In a and c, L.B., low brightness; H.B., high brightness.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Related to HK detachment from the OMM promotes aerobic glycolysis.

(a) Specific growth rates for control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of HK2-knockout and control cells stained with 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), which is excluded from live cells. (c) Relative growth rates for HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. (d) Net rates of lactate secretion versus glucose uptake in HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test. (e, f, g, h, j) Fractional labeling of pyruvate (e, f), serine (g), citrate (h), and malate (j) in HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples) grown in conditions with [U-13C-glucose]. Defined lactate levels in HPLM and RPMI (f, bottom right). (i, k) Total 13C labeling of citrate (i) and malate (k) in HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples) grown in conditions with [U-13C-glucose]. (l) Schematic depicting the incorporation of 13C from [1,2-13C] glucose into 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) and lactate. Orange-outlined box, labeling generated when [1,2-13C] glucose is metabolized via the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (ox-PPP). Green-outlined box, labeling generated when [1,2-13C] glucose is metabolized via glycolysis. (m, n) Fractional labeling of 3PG (m) and lactate (n) in HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples) grown in conditions with [1,2-13C-glucose]. In e, f, g, h, i, j, k, m, and n, Values above brackets indicate differences in fractional labeling between bars. Two-tailed Welch’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Related to HK2 dependence is not linked to a direct gene-nutrient interaction.

(a, c, e, g, j, k) Rates of net exchange for glucose (a), glutamine (c), lactate (e), pyruvate (g), and alanine (j, k) for HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test between bars. Blue box (k, bottom right), exogenous alanine levels at 72 h vs 24 h (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). No exchange (ne) was defined as a change in exogenous levels less than 5%. (b, d, f, h, i) Exogenous levels of glucose (b), glutamine (d), lactate (f), pyruvate (h), and alanine (i) during log growth of HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Blue box (i, right), exogenous alanine levels at 72 h vs 24 h (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). (l) Immunoblot for expression of HK1 in WC and IP:HA from HK2-knockout cells that expressed HA-MITO. COXIV served as a mitochondrial control marker. S6K served as a non-mitochondrial control marker. (m) HK1 signal normalized by COXIV signal in IP:HA versus WC from the same respective cells. (n) Fractional labeling of lactate in HK2-knockout cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Values above brackets indicate differences in fractional labeling between bars. Two-tailed Welch’s t-test. (o, p, q, r) Relative growth of HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. For o, p, and q, metabolites that comprised each respective pool of HPLM-specific metabolites can be found in Fig. 5i.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Related to HK detachment from the OMM drives glycolytic ATP production.

(a) Relative growth of HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. (b, c, d, e, f) Relative levels of the indicated metabolites in HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. Hypoxanthine (Hx), adenosine (Ado), and guanosine (Guo) can serve as salvage substrates for purine synthesis. Cytidine (Cyt) and uridine (Urd) can serve as salvage substrates for pyrimidine synthesis. Thymidine (Thy) is a salvage substrate for thymidylate (b, right). N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) can act as a salvage substrate for UDP-GlcNAc (c, right). Glycerol-3-phosphate (Glycerol-3P) and acetyl-CoA are key intermediates involved in palmitate synthesis (d, right). Dimethyl α-KG (DM-α-KG) may deliver an additional carbon source to the TCA cycle (e, right). NADPH is a key product of the oxidative pentose phosphate (ox-PPP) pathway (f, right). (g) Pyruvate-to-lactate ratios in HK2-knockout and control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test. (h, i) Relative growth of HK2-knockout and control cells treated with duroquinone (DQ) (h) or UK5099 (i) versus vehicle-treated control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. DQ can serve as an electron acceptor for the NAD+-generating reaction catalyzed by NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1 (NQO). DHQ, durohydroquinone. (h, right). UK5099 is a small molecule inhibitor of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) (i, right). (j) Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and proton efflux rates (PER) for HK2-knockout and control cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 6 biologically independent replicates). OA, oligomycin A; Rot, rotenone; AA, antimycin A. (k) Basal OCR (left) and OCR coupled to ATP production (right) for HK2-knockout versus control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 6 biologically independent replicates). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells). (l) Total population doublings for control cells (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Value above bracket indicates difference in total doublings.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Related to conditional HK2 dependence varies with cell-intrinsic factors.

(a) HK signal normalized by COXIV signal in IP:HA versus WC from the same respective cells. nd, not detected. (b) Immunoblots for expression of HK1 and HK2 (c) in dounce homogenates (DH) and corresponding cytosolic (Cyt) and organellar (Org) fractions isolated from NOMO1 cells. S6K served as cytosolic control marker. COXIV served as a mitochondrial control marker. L.B., low brightness; H.B., high brightness. (c) HK signal normalized by COXIV signal in Org versus DH from the same respective cells. Comparisons of normalized signal between HK1 and HK2 are derived using the same experimental samples run across different blots and processed in parallel. (d) Relative growth of indicated cell lines transduced with sgHK2 versus sgAAVS1 (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. (e) Relative growth rates of indicated cell lines transduced with sgHK2 versus sgAAVS1 (mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples). Two-tailed Welch’s t-test comparing the respective mean ± s.d. (bar) versus mean ± s.d. (control cells) between bars. (f) Distribution of mRNA transcript levels for indicated monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)-encoding SLC16 isoforms across human cancer lines from cataloged RNA-Seq data23. Displayed percentage, cell lines with log2(TPM + 1) greater than 1. Bolded line, median. TPM, transcripts per million. (g) mRNA transcript levels for SLC16A7 (top) and SLC16A8 (bottom) across the indicated cell lines from analyzed RNA-seq data80. SLC16A7 encodes MCT2. SLC16A8 encodes MCT3. nTPM, normalized TPM. (h) Human cancer lines ranked by SLC16A3 mRNA transcript levels from cataloged RNA-Seq data23. Labeled points indicate cell lines that exhibited conditional HK2 dependence in this study.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Expression of HK1 and HK2 in non-diseased tissue sites.

(a) Comparison between HK1 and HK2 mRNA transcript levels from the GTEx85. Dotted lines are at transcripts per million (TPM) = 20. (b) Annotated sites for which the TPM value for HK2 is greater than 20.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Conditional gene essentiality identifies regulatory nodes of the Warburg effect.

(a) Schematic depicting all steps of aerobic glycolysis from glucose uptake to lactate secretion and others involved in mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism (left). Dependency phenotypes for genes expressed in K562 cells according to cataloged RNA-seq data23. Essentiality is defined as a probability of dependency > 0.5. See Supplementary Table 4 (right). TIGAR is not expressed in K562 cells23. (b) Dependency phenotypes for PFKP and SLC16A3 from the DepMap9.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Synthetic media construction.

Supplementary Table 2

Datasets related to cellular metabolomics.

Supplementary Table 3

Datasets related to Seahorse assays.

Supplementary Table 4

Fermentation-related gene panel.

Supplementary Table 5

Reagents and resources.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Figs. 1–3 and 7

Uncropped immunoblots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Figs. 1–3, 5 and 7

Uncropped immunoblots and Coomassie-stained gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Gating strategy for cell death analysis.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huggler, K.S., Flickinger, K.M., Forsberg, M.H. et al. Hexokinase detachment from mitochondria drives the Warburg effect to support compartmentalized ATP production. Nat Metab 8, 215–236 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01428-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01428-1