Abstract

While resilience assessments have begun considering equity, many fail to account for the nuanced impacts of infrastructure disruptions on sub-populations. This study hypothesizes the necessity of considering equity factors and empowering policymakers in tailoring plans for sub-populations during ‘black swan’ events. Departing from the ‘one-size-fits-all’ risk analysis, it promotes a more inclusive resilience perspective. Using the Travel Characteristic Survey dataset, the study examines socio-demographic, temporal, and spatial factors affecting the Hong Kong metro system’s resilience. Younger and older cohorts showed higher preparedness and robustness against both disruptions and attacks, but lower recovery capabilities. By mitigating disparities in resilience impacts, this framework shifts from utilitarian principles to integrating deontological theory in resilience analysis, recognizing citizens’ intrinsic value, advocating for social justice, and promoting sustainability. It also guides stakeholders in identifying stations needing improvements to address diverse social needs more efficiently. Moreover, it integrates resilience-by-design and resilience-by-intervention approaches, enhancing individual systems and external emergency measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

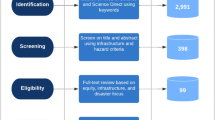

Rapid urbanization, with over half of the global population in cities and projected to reach two-thirds by 20501, heightens our dependence on urban infrastructure. The expected rise in global disasters from 400 in 2015 to 560 by 2030, a projected 40% increase2, further underscores the urgent need to address vulnerabilities in interconnected urban infrastructure systems. Moreover, disruptions in infrastructure services disproportionately affect certain subpopulations due to varying usage patterns, access levels, and response capabilities3. Therefore, understanding the differential impacts of infrastructure disruptions on subgroups is crucial for designing equitable and effective resilience strategies, essential for sustainable urban development. This study integrates the equity perspective into urban public transportation network infrastructure resilience (UPTNIR) to optimize design and management strategies. By considering diverse socio-demographic, temporal, and spatial travel demands, it incorporates equity into the multi-stage resilience analysis cycle. This approach provides a more nuanced framework for understanding how different social groups are impacted by infrastructure disruptions.

Resilience is defined differently across disciplines. According to the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS), it is ‘the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events’4, differing from traditional risk analysis in two key ways: 1) it enhances risk analysis by encompassing recovery and adaptation phases5, ensuring the swift return to the pre-crisis state and better anticipation of future crises6. 2) Risk analysis, focusing on specific event probability and consequences, often leads to rigid protection frameworks5. Resilience analysis, however, targets “black swan” events—rare but impactful occurrences—emphasizing flexibility, swift recovery, and countermeasures against cascading systemic threats5.

Previous resilience assessment methods can be categorized into Resilience-by-Design (RbD) and Resilience-by-Intervention (RbI). Introduced by Linkov and Trump5,7, RbD prioritizes system autonomy in maintaining critical functions and aligns with approaches like complex network-based modeling. It focuses on internal system features, making it suitable for urban network infrastructure, like transportation systems. Conversely, RbI emphasizes external resources for continuity and recovery. For instance, Wood’s concept evaluates resilience by deploying, mobilizing, and generating resources like pre-disruption stockpiles or emergency-use facilities8. While studies historically focused on individual aspects, as noted by Linkov et al.9, neither approach alone suffices for current challenges. While RbD analyses the system’s inner features affecting disruption extent, RbI serves as a crucial emergency measure for maintaining critical functions and aiding recovery when independence falters7. Therefore, adopting an integrated RbD and RbI approach is imperative to enhance urban infrastructure network resilience.

Several frameworks have emerged to evaluate resilience facets and phases, integrating RbD and RbI. Among these, Bruneau et al.10 present a well-recognized ‘4-Rs’ framework, which identifies four key properties of resilience: robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity. Ouyang et al.11 propose another influential framework that emphasizes a system’s ability to resist, absorb, and recover from disruptions. Complementing these approaches, Xu and Chopra12 introduce a framework that analyzes a system’s vulnerabilities in terms of pre-disruption preparedness and assesses its ability to learn and reorganize for long-term adaptation post-disruption.

To apply these conceptual frameworks in practice, researchers have developed a range of modeling and simulation techniques. Among these, network-based approaches are particularly well-suited for their feature in capturing critical topological features, providing high spatial resolution, and allowing for flexible granularity12,13. Foundational studies, such as those by Barabási and Albert14 on scale-free networks and by Watts and Strogatz15 on small-world networks, underscore the role of network structure in determining system performance. Expanding on these concepts, Ash and Newth16 explored the resilience of homogeneous networks, emphasizing the importance of modularity, high clustering, long path lengths, and interconnected hubs in mitigating cascading failures. Similarly, Derrible and Kennedy17 observed that many networks often exhibit both scale-free and small-world properties, highlighting the importance of localized redundancy and robust hubs to sustain functionality during disruptions. Haritha and Anjaneyulu18 introduced topological metrics, such as global efficiency, the number of independent paths, and the size of the giant component, to further quantify resilience and assess system performance under stress. Moving beyond topology, researchers have incorporated flow-based metrics to capture dynamic behavior. Li et al.19 introduced traffic percolation analysis to distinguish between static and dynamic bottlenecks, enabling a deeper understanding of congestion patterns during disruptions. Chopra et al.20 analyzed passenger flows to uncover additional vulnerabilities that static topological metrics might overlook.

Transportation infrastructure is a cornerstone of urban resilience, ensuring mobility, accessibility, and the restoration of critical services during disruptions21. As cities grow and urbanization intensifies, these networks become indispensable for sustaining economic growth and addressing environmental challenges, aligning with sustainable development goals (SDGs)22,23. Beyond disaster scenarios, resilient transportation systems safeguard city functionality, enhance community well-being, and bolster investor confidence24,25.

To address the multifaceted challenges of transportation resilience, researchers have developed a range of analytical methods. Big data applications utilize sources such as GPS tracking, social media, and service records to monitor transportation networks and assess disaster impacts in real-time21. For instance, Donovan and Work26 leveraged GPS data to detect disaster events, while Diab and Shalaby27 examined “Lost Days of Service” using metro records. Although these approaches excel in real-time monitoring and efficient data processing, they often struggle to filter noisy data and account for physical network damage or demand fluctuations21. Simulation-based methods complement these efforts by modeling hypothetical or unprecedented scenarios, enabling vulnerability analysis and interdependency assessments. Studies like Ganin et al.28 and Yang et al.29 demonstrated the value of simulations in addressing cyberattacks and flooding, respectively. However, these methods are computationally intensive and require precise calibration, limiting their scalability for city-wide assessments. Similarly, model optimization techniques offer practical solutions for designing resilient networks or optimizing post-disaster recovery strategies, as exemplified by Ye and Ukkusuri’s30 work on recovery sequence prioritization. While effective in constrained planning, these techniques depend heavily on accurate mathematical formulations and policy alignment, which can hinder real-world applicability.

Compared to resource-intensive methods, network-based approaches offer simplicity, flexibility, and accessibility, enabling them to effectively capture the structural essence of transportation systems21. By representing these systems as networks of nodes and links, graph theory provides a clear framework for analyzing connectivity, identifying critical nodes, and developing resilience strategies. For example, Zhang et al.31 modeled metro resilience using network-based methods, while Li et al.32 employed traffic percolation analysis to identify bottlenecks. Unlike big data or simulation-based methods, network-based approaches rely on readily available topological data, making them accessible for both theoretical research and practical applications21. Additionally, by modeling the dynamic patterns of passenger flow, these approaches provide valuable insights into traffic behaviors over time12,33. This combination of features allows network-based methods to offer insights into structural vulnerabilities and resilience planning in transportation.

Despite their value and the growing attention to the flow-weighted models, these studies often regard the flow as monolithic entities12,20,33 and overlook equity considerations among subpopulations, neglecting disparate disruption impacts. However, prior literature has noted that certain socio-demographic factors exacerbate disruptions impacts3,34, leading to vulnerability inequalities in natural disasters35. Recent reports also highlight gaps in understanding the diverse societal impacts of infrastructure disruptions4. For instance, persons with disabilities and chronic illnesses are more vulnerable to earthquake and tsunami-induced, alongside hourly workers facing income loss4. These examples illustrate the unequal disruption impacts, emphasizing the need for equity considerations in developing comprehensive approaches to resilient infrastructure.

In previous work, equity in resilience is defined through two main approaches. The first categorizes equity into procedural, systemic, distributive, and recognitional categories36. Conversely, the second approach divides equity into four dimensions37: distributional-demographic (D), distributional-spatial (S), procedural (P), and capacity (C) equity. Adopting this practical second approach aligns closely with our goal of actionable solutions for infrastructure resilience, emphasizing actionable outcomes over abstract concepts. Distributional-demographic equity ensures infrastructure meets vulnerable groups’ needs37, like wheelchair-accessible buses for disabilities. Distributional-spatial equity promotes service equity across regions37, like promoting equitable access for urban and suburban populations. Procedural equity ensures fair participation in decision-making37, like equal opportunities for marginalized groups to influence outcomes. Capacity equity assesses individuals’ ability to cope with infrastructure loss37, such as helping low-income households acquire bicycles as an alternative during disruptions. As this emerging concept gains traction, previous literature may have employed various terms to express similar principles or goals (Table 1). However, these concepts align with specific equity sub-dimensions and underscore the significance of these concepts within the broader discourse on equitable resilience.

Among the limited work on transportation resilience analyses, subjective experiences are often considered through qualitative approaches such as surveys3 and interviews38. However, an objective comparison of the impacts on physical functionality is also essential. This broader perspective enables a more comprehensive evaluation of the adverse effects of service disruptions, particularly on vulnerable groups during outages. While quantitative studies have predominantly focused on equity at a single stage, such as the preparedness39 or robustness40 stages, it is equally important to examine how physical functionality varies across the entire resilience cycle. Such an understanding is crucial for developing strategies that address the diverse needs of subpopulations during infrastructure planning and prioritization. Moreover, although previous studies acknowledge the importance of equity, few provide practical, equity-focused decision-making tools, highlighting the need for such tools to guide policy effectively41.

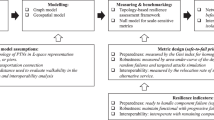

Expanding on the existing literature, this study applies an equity lens to UPTNIR to enhance both design and management strategies. By incorporating diverse socio-demographic, temporal, and spatial travel demands, it integrates equity into the four-stage resilience analysis cycle12: preparedness, robustness, recovery, and adaptation (Fig. 1). Using advanced complex network theory and incorporating usage demand, it assesses resilience performance and specific requirements for various intersecting social groups, offering actionable insights pre- and post-disruption. Integrating RbD with RbI, this framework addresses the internal system features and external support needs, enhancing resilience and emphasizing equitable treatment. Generally, this research aims to answer: 1) How do resilience stages vary across different social groups at the intersection of age, income level, and gender? 2) What strategies can be derived from the equitable resilience analysis?

Hong Kong, one of the world’s most densely populated areas, relies heavily on its advanced metro system, with the mass transit railway (MTR) accounting for 43.4% of daily public transport journeys on average42. However, as a coastal city with a subtropical climate, Hong Kong faces diverse disruptions that can severely affect the rail network functionality. For example, Typhoon Koinu in October 2023 halted MTR services, stranding thousands of passengers43. This highlights the Hong Kong MTR’s critical role in research on infrastructure resilience.

Results

Pre-disruption preparedness differs by demographics and time dynamics

By calculating (1-Gini) indices \({G}_{{WB}}\) for the Flow-weighted Betweenness Centrality (FBC)12 of the 84 stations of the MTR network, we assess the system preparedness for intersections of different socio-demographic groups based on gender, age, and income attributes. A high Gini coefficient indicates uneven station importance, highlighting critical nodes such as central hubs or interchanges with high passenger volumes. These nodes, connecting multiple lines and accommodating more passengers, could increase system vulnerabilities and reduce preparedness performance due to their centrality if they fail12,44.

Age-related factors significantly impact preparedness performance (In Fig. 2, where we plot the 1-Gini, higher values indicate better preparedness). Notably, youth (aged 3–14) exhibit higher preparedness during the daytime, likely due to dispersed school locations across Hong Kong, resulting in varied usage locations. In contrast, working-age groups, particularly those aged 24–44, exhibit lower preparedness performance during commuting peak hours, possibly reflecting the importance of stations near employment hubs influenced by Hong Kong’s concentrated employment centers. Older adults (aged 64 and above) demonstrate a higher preparedness performance compared to young working-aged adults during this period, consistent with previous research indicating a more even trip distribution among those aged 64–6945.

The preparedness measures the equality of station importance for 7 age groups at four timeframes: morning peak (7–9 am), afternoon off-peak (10 am–4 pm), evening peak (5–7 pm), and evening off-peak (8 pm–12 am). A higher value indicates the system’s better preparedness level for this age group at a specific time period).

Elderly passengers show lower indices in the evening compared to the daytime, indicating a focused travel pattern. This aligns with literature suggesting a preference for shorter trips within residential areas during this time45. The lower indices likely result from their avoiding nighttime travel, concentrating activities near home or familiar locations, influenced by Hong Kong’s urban living patterns, particularly in Kwun Tong and Eastern zones45. To ensure equal preparedness, infrastructure enhancements at stations frequented by seniors (aged 64+) during evening hours are crucial for their needs. This includes installing additional lifts or ramps to minimize platform-train gaps. Enhancing safety measures by increasing the availability of first aid kits and automated external defibrillators is essential. Improving accessibility with well-lit and adjustable ticket vending machines for wheelchair users would also benefit elderly passengers. Designating priority boarding areas and improving lighting and font size further support elderly passengers. Targeted personnel training could provide specialized assistance, addressing mobility challenges effectively. Without such enhancements, elderly accessibility could suffer disproportionately during incidents like the 2023 incident at Wong Tai Sin Station, where the escalator malfunctioned during an amber, which poses greater challenges for elderly passengers.

Data limitations exist for children under 3 who travel free on the MTR, not captured in card data, creating a gap in understanding their resilience. Often considered “travel companions”, their needs may be overshadowed by those of accompanying adults46. This “invisible” population, similar to travelers with disabilities47, may have unique needs that remain largely unexplored. Future studies could explore resilience considerations for this demographic.

Distinct disparities in preparedness emerge across the intersection of age and gender over different timeframes (Fig. 3a). Male youth show lower performance during the evening off-peak time, likely due to their involvement in expansive activities48 concentrated in specific areas, such as the northern shore of Hong Kong Island. Malfunctions at these stations during the evening could disproportionately affect this group’s destination reachability, underscoring the importance of targeted station management. For instance, implementing queue management systems with clear wait time displays, brightly colored queue lines, and enhancing real-time information dissemination through interactive signage, mobile apps, or gamified elements can target crowd control challenges faced by young passengers.

a Gender-based preparedness among age groups across four timeframes (Morning peak (7 am–9 am), afternoon off-peak (10 am–4 pm), evening peak (5–7 pm), and evening off-peak (8 pm–12 am). The bar represents the (1-GINI) index of each group, measuring the system’s preparedness for each at different times during the day). b Hourly Preparedness(1 -GINI) Trends and the Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test by Income (We calculate the (1- GINI) index per hour for the three income groups. The boxplot in the lower right corner illustrates the statistical distribution of the hourly preparedness level for each group, with the results of the KW test indicating a statistically significant difference.)

Statistically significant variations in preparedness levels among income groups are evident (Fig. 3b, p value < 0.05). High-income individuals consistently exhibit lower preparedness indices throughout most of the day, indicating a more imbalanced distribution of station importance. Stations like Quarry Bay, located in economically developed districts and serving as interchanges, are disproportionately critical. Disruptions at these key stations can significantly impact network functionality for high-income commuters due to their fixed work locations and travel times in areas like the financial district. Conversely, low-income jobs may be more dispersed, allowing for greater travel pattern flexibility among low-income individuals, resulting in more varied use of the MTR system.

Diverse during-disruption robustness based on demographics and temporal factors

Evaluating robustness involves calculating the indicator \({r}_{b}\) by integrating degradation curves from simulations of three scenarios: Random disruption, FBC, and ND attack.

Gender and temporal factors influence the robustness performance of the MTR system against three disruption scenarios. Intriguingly, women consistently exhibit higher robustness across all three scenarios (Fig. 4a), indicating potentially greater remained system functionality for women during consecutive disruptions. Unsurprisingly, both men and women show better robustness during random disruptions, compared to human-induced continuous attacks, such as the MTR disruptions during the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in October 2019.

a Degradation Curve for gender groups(The curve illustrates the network’s ability to maintain functionality given sequential disruptions. A shallower gradient on the degradation curve and a larger area under the curve indicate better robustness performance for this group. The curve was generated by progressively removing nodes from the network based on three predetermined lists, while functionality was continuously computed after each step by examining paths for OD flows of each social group. The integral method is then applied to calculate the area under the curve, indicating the system’s robustness for each social group. The simulation for random disruption is repeated five hundred times to generate an averaged degradation curve, ensuring the reproducibility of results. As a result, the degradation curve for this scenario displays a smoother trend compared to the other scenarios.) b Degradation Curve for age groups (In the lower right corner, we demonstrate the significant negative correlation between the ATD and robustness in both the Random disruption and ND attack scenarios). c Degradation Curve for income groups.

Regarding temporal aspects (Fig. 5a, b), a statistically significant distinction emerges during early afternoon off-peak intervals (from 10 am to 4 pm) in both FBC and ND attacks across gender demographics (p value < 0.05). This distinction may stem from gender-based divisions of family roles, particularly during off-peak trips. Previous studies49 indicate that women, often managing caregiving and household responsibilities, engage in ‘trip-chaining’, consolidating multiple trips into one outing. This leads to visiting a wider range of stations, possibly reducing reliance on specific destinations and vulnerability to targeted attacks. Considering that research suggests men may favor technological solutions for enhancing safety50, the MTR could explore, in specific scenarios, implementing technological security measures for real-time information and incident reporting to improve crowd management during disruptions and potentially enhance security perceptions among male passengers.

(The two figures illustrate the system’s hourly robustness performance to a FBC, and b ND attacks for the two gender groups, as well as for the overall population. We conducted the Mann–Whitney U test for the two groups at four different time periods throughout the day. The results indicate significant differences in performance between the two groups during the afternoon off-peak hour (p value < 0.05).

Notably, different age groups exhibit distinct patterns of robustness across scenarios and temporal factors (Supplementary Fig. 3). Surprisingly, youth and elderly cohorts consistently exhibit higher robustness, while individuals aged 24–34 consistently show the lowest robustness across all scenarios. Our study also analyzes how average travel distance (ATD), indicating station coverage during trips, influences age groups’ robustness (Fig. 4b). The ATD is calculated as the total distance traveled by an age group divided by the total number of passengers in that group, reflecting station utilization patterns. Consistent with prior research12, a significant negative correlation \({(R}^{2}=0.99,\,{p}_{\mathrm{value}} < 0.01)\) between ATD and \({r}_{b}\)(Random) is observed, confirming previous findings. Similar trends are evident in \({r}_{b}\)(ND), revealing a negative correlation \({(R}^{2}=0.96,\,{p}_{\mathrm{value}} < 0.01)\). These results indicate that age groups traveling longer distances on the MTR may be more vulnerable to both random failures and human-induced attacks based on ND importance.

Analyzing robustness variations by gender and age groups across different scenarios reveals intriguing insights. In the Random scenario (Fig. 6a), boys aged 3 to 14 exhibit the highest robustness, while working-age men show lower robustness during peak hours. Enhancing infrastructure is crucial to mitigate disruptions from random events, which paralyzed several stations during morning peak hours. This is especially critical for working-age commuters, who may face heightened vulnerability during these periods, leading to economic losses from missed work opportunities due to disrupted trips

a Random disruption scenarios(The bar represents the random robustness of each group, reflecting the system’s ability to maintain functionality during continuous random disruptions for each group across the four timeframes. A higher value signifies better robustness performance for a specific group). b FBC attack (The bar represents the robustness of each group under the FBC scenario, reflecting the system’s ability to maintain functionality during continuous attacks based on FBC order for each group across the four timeframes). c ND attack (The bar represents the robustness of each group under the ND scenario).

In both the FBC and ND scenarios (Fig. 6b, c), men aged 24–34 exhibit the lowest robustness among all age and gender groups during morning and evening rush hours. Interestingly, women generally outperform men within the working-age category. Targeted reinforcement measures are crucial to maintain consistent system functionality, especially during FBC order attacks.

Notably, higher-income individuals consistently exhibit lower robustness, while lower-income groups demonstrate higher robustness. This observation suggests that higher-income commuters, possibly benefiting from greater access to resources and well-connected locations, might, in certain contexts, travel across larger spatial areas and cover greater distances in their daily activity spaces50. This broader spatial activity could potentially increase their vulnerabilities to disruptions.

Age and temporal factors influence MTR after-disruption recovery capability

To evaluate equality in the recovery stage, we quantified the passenger relocation rate at each station by considering spatial distances from neighboring nodes and connectivity between neighboring nodes and the destination.

Age significantly influences recovery rates, with only 7% of stations retaining over 30% of passengers below 14 and over 65, compared to nearly double for working-age groups (Table 2 and Fig. 7). In other words, different age groups exhibit varying relocation rates at the same station. This disparity may be due to age-related differences in acceptable walking distances51 (Supplementary Table 2) and greater engagement in income-generating activities among working-age groups. For example, stations like Prince Edward and Mong Kok, serving over 200,000 daily passengers in densely populated areas, exhibit relocation rates above 30% exclusively among working-age commuters. This suggests that during station closure, due to disruptions, younger and elderly demographics may be less inclined to continue their metro journeys, highlighting the need for targeted consideration. To enhance short-term recovery following events like the December 2019 closure of Mong Kok station, stakeholders could implement temporary shuttle services tailored for youth and elderly commuters. Ignoring equity in planning could disadvantage these groups, potentially leading to longer wait times if shuttle services were universally available across age groups, reducing youth and elderly commuters’ willingness to continue their MTR journeys.

Surprisingly, the metro system showed higher recovery capabilities for most age groups during peak periods compared to overall daily performance (Supplementary Table 3, 4). This suggests greater potential for passenger relocation during peak hours due to specific OD flow dynamics and increased connectivity between neighboring origin and destination stations, highlighting the unique dynamics of peak-hour travel.

We calculate the accessibility of each station’s walking-accessible neighbor stations for each OD flow to evaluate the system’s short-term recovery capability for each age group. The red circle marks stations with a relocation rate exceeding 30% for individuals between 24 and 64, the blue for youth (3–14 years old), and the yellow for the elderly (over 64). As depicted in the figure, the same station exhibits varying relocation rates for different age groups, suggesting varying recovery capabilities within the system for these groups.

Discussion

This study systematically evaluates social inequities in infrastructure resilience through quantitative analysis and offers actionable suggestions for their improvement. Applied to the Hong Kong metro system, it demonstrates unequal resilience levels at the intersections of different age, gender, and income social groups, underscoring the need to integrate equity into the conventional understanding of UPTNIR.

The observed disparities in resilience highlight the importance of incorporating resilience ethics into urban infrastructure planning. Developing equitable resilience strategies is imperative, especially given the disproportionate impact of climate change on marginalized and vulnerable groups, such as persons with disabilities in Hong Kong52. The key question for policymakers is what criteria to prioritize when planning the city’s transportation network infrastructure. Should they focus on maximizing overall functionality during disruptions by allocating more resources to high FBC stations like Admiralty, or should they give more emphasis to destination reachability for all citizens, like those stations frequented by the elderly?

This fundamental question highlights the tension between individual intrinsic value and public interests, similar to the conflict between the deontological basis of bioethics and the utilitarian ethos of triage in public health emergencies53. Utilitarianism favors actions that maximize overall interest satisfaction, focusing on outcomes and benefits54, and emphasizing the “public good”. For example, planners might prioritize restoring functionality to the busiest stations and lines after a shock, potentially reducing accessibility for passengers in less-frequented suburban or lower-income areas—a practice that perpetuates historical or ecological inequities. This perspective parallels the ethos of triage in disaster medicine. In contrast, deontological ethics prioritize moral rules or duties over consequences54, emphasizing the respect for the intrinsic value of individuals and their moral rights, akin to the principles of clinical bioethics rooted in a deontological heritage53.

Utilitarian principles commonly guide urban infrastructure design, aiming for efficiency and overall benefit34. For example, expanding subway lines to connect major urban centers might not fully address the interests of individuals in suburban areas53. However, as Rawls55 criticizes, utilitarianism overlooks individual distinctions, highlighting a key limitation: it cannot function as a system without acknowledging individual differences56. Like disaster triage, where healthcare providers must balance the utilitarian objective of saving the most lives against the deontological mandate to uphold individual intrinsic worth, infrastructure system planning also requires consideration of all individuals’ intrinsic value and moral dignity. This ethical consideration is crucial to ensure inclusive and equitable urban infrastructure, respecting citizens’ autonomy and avoiding their treatment as mere means56. Therefore, urban planning needs to shift beyond prioritizing overall benefits for cities as entities and instead strive for the well-being and resilience of every individual citizen.

Procedural equity is a cornerstone of equitable resilience planning, particularly during the resilience adaptation stage, as it determines who has a voice in decision-making and how those voices influence policies37 and, thus, infrastructure priorities. Historically, inequities in reconstruction have often stemmed from procedural vulnerabilities, deeply rooted in systemic power imbalances57. These imbalances have led to the exclusion of marginalized groups from risk planning and mitigation processes58, which in turn results in decisions that fail to address their needs. While tools such as media campaigns, opinion polls, and surveys, as discussed by Fitzgibbons and Mitchell59, are used to gather public input, they often fail to provide meaningful opportunities for ‘deep engagement,’ such as collaboration or co-creation. These tools typically offer limited engagement, reducing residents to passive informants rather than active decision-makers.

This limited engagement aligns with the lower rungs of Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation60, where planning practices remain at tokenism or, worse, nonparticipation. To move beyond these pitfalls, cities must adopt mechanisms that elevate participation to higher levels. For instance, structures such as joint planning committees or community boards can empower residents by granting them the authority to influence decisions directly60. In the context of infrastructure construction, community advisory boards with the ability to review plans and negotiate solutions play a critical role in ensuring that citizen voices are genuinely integrated into pivotal decisions. However, for these mechanisms to be more effective, they also need to be adequately supported. Having essential resources, such as funding to compensate leaders for their time-intensive efforts or to hire independent experts, is crucial60. Such support ensures that participation evolves beyond an ‘empty ritual’ and allows citizens to have genuine bargaining power over the final outcomes60. By embracing these strategies, resilience planning can achieve more equitable and inclusive results, particularly during the adaptation phase.

Building equitable and inclusive resilience requires not only fostering meaningful citizen participation but also integrating strategic frameworks that strengthen infrastructure systems. Our resilience assessment highlights varying performance among socio-demographic groups. For example, working-age men exhibit heightened vulnerability during peak hours across both random crises and human-induced disruptions, such as FBC and ND scenarios. Meanwhile, elderly commuters show limited recovery capacity. These findings highlight the necessity for targeted strategies to ensure consistent system functionality and minimize disruptions.

The proposed RbD strategies focus on structural improvements to enhance redundancy, directly addressing the vulnerabilities identified in the assessment. For example, constructing redundant links, such as bypass routes through interconnecting tunnels or elevated tracts, can provide alternative paths during disruptions In business districts, such as Quarry Bay, where working-age commuters rely on uninterrupted transit, these routes can be critical. Expanding platform capacities and extending station infrastructure in those areas alleviate congestion and enhance operational efficiency, particularly during peak hours, which reduces the impact of disruptions. Additionally, future metro network designs should adopt grid-like topologies with interconnected routes and transfer stations to maximize flexibility. In districts near Admiralty, where the network’s remaining functionality directly affects working-age commuters, such designs could play a pivotal role. Additionally, integrating critical infrastructure components—such as backup power generators, modular fare gates, and emergency ventilation systems—ensures operational continuity and adaptability to evolving demands.

Complementing these structural strategies, RbI measures emphasize operational responding during disruptions, implemented through three phases: deploy, mobilize, and generate8. In the deploy phase, immediate actions include dispatching emergency bus fleets to high-demand routes, such as those linking to Kowloon Tong, to provide critical alternatives for working-age commuters during peak hours. The mobilization phase focuses on mobilizing available resources dynamically in response to real-time conditions. Leveraging reinforcement learning algorithms, transit agencies can prioritize support for routes serving vulnerable groups, such as working-age men in CBDs or elderly passengers in residential areas, like those close to Kwun Tong. In the generate phase, partnerships with ride-sharing companies and micromobility providers can create integrated multimodal solutions, addressing first- and last-mile connectivity needs. These measures not only enhance the system’s adaptability for working-age men but also increase recovery capacity for elderly commuters and others with limited mobility. By integrating RbD and RbI strategies, this framework directly addresses the vulnerabilities identified in the resilience assessment. These strategies ensure a resilient metro system that can withstand diverse challenges while providing equitable transportation for all user groups.

Integrating human diversity factors into infrastructure planning, this framework guides urban public transportation agencies, policymakers, civil engineers, and stakeholders in designing, constructing, and adapting infrastructure to promote inclusivity, equity, and community-specific needs, fostering sustainable and resilient urban development. Moreover, by highlighting unique travel patterns of intersections and identifying temporal-specific needs, this framework enhances the practicality of resilience analysis. It offers tailored guidance to stakeholders and lays the groundwork for integrating RbD and RbI strategies. These strategies strengthen internal systems topologically and rely on external resources during emergencies. The limitations in available data resources constrain the inclusion of more comprehensive features in the analysis. In future analyses, augmenting the dataset with additional reliable information while ensuring user privacy protection—such as occupation, disability status, and education levels—would enable policymakers to strategically prioritize infrastructure design and resource allocation. Moreover, to promote the widespread adoption of an equitable and inclusive approach in evaluating UPTNIR worldwide, future work must introduce a universally accepted standardization framework (Table 3). This ensures consistency and efficiency in the assessment, enabling global cities to effectively measure and enhance the equitable resilience of their urban public transportation networks.

Methods

This section outlines an innovative people-centered resilience framework along with its simulation and analysis methodologies. We assess the system’s performance across four key stages: pre-disruption preparation, during-disruption absorption, post-disruption recovery, and further adaptation, in line with Linkov et al.‘s description5 and echoing the resilience cycle delineated by the NAS Councils4. With each cycle completed, the system evolves, enhancing its resilience to future disruptions. Unlike previous studies10,12, our approach advances the existing cycle by employing indicators that encompass a broad spectrum of socio-demographic factors, rather than relying solely on concepts from graph theory and complex networks.

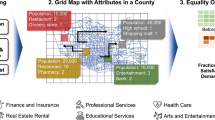

We illustrate the framework using the MTR system in Hong Kong, leveraging Origin-Destination (O-D) flow data sourced from the 2011 Travel Characteristics Survey (TCS 2011) database61 provided by the local government. The TCS dataset, although based on self-reported travel behaviors, allows for capturing the temporal aspect of trips through the recorded mid-time of each journey. By organizing trips according to their mid-time, the dataset facilitates the analysis of dynamic variations in OD flows throughout the day. This approach offers valuable insights into the temporal dynamics of the transport network.

Due to data limitations, our analysis focuses exclusively on weekday travel data. This study does not explore the adaptation process as it’s viewed as a long-term modification rather than a short-term, quantifiable assessment.

Network modeling

The infrastructure network, denoted as \(G\), encompasses \(V\) and \(E\), conforming to the L-representation62 :

where \(V\) denotes a set of nodes corresponding to metro stations and \(E\) denotes edge sets signifying the presence of at least one metro line between node pairs. The network model illustrates the topological aspects of the infrastructure network. We then integrated diverse social groups’ usage patterns into this network by dividing and employing each group’s OD flow matrix, which signifies their travel demand and, consequently, their distinct usage patterns. Employing the OD matrix eliminates the necessity for all-pair-shortest-path analysis on an unweighted network33 and allows for a comprehensive understanding of the specific requirements of diverse social groups.

Network preparedness

In evaluating preparedness, we assess the systematic heterogeneity of nodes’ importance distribution—an essential metric derived from integrating travel demand and infrastructure network topology. A higher degree of heterogeneity within a system may imply an increased vulnerability to an abrupt collapse in functionality. This stems from certain nodes potentially holding significant importance within the network, and their failure may result in system disintegration12. For instance, in a hub-and-spoke distribution, the collapse of its central hub node might isolate most of the spokes, compromising the overall structure’s integrity. In contrast, within a lattice structure characterized by evenly distributed node importance, the failure of specific nodes would only lead to localized impacts, preserving the system’s overall functionality.

In graph theory, the significance of a node can be quantified using betweenness centrality (BC), computed by the Brandes algorithm63. A node with high BC is a crucial link, forming an important portion of the shortest paths between other nodes. Its failure significantly impacts the connectivity of the entire system. The measurement of node significance concerning transport functionality is better achieved using the FBC12. Unlike previous metrics focusing solely on infrastructure topology, FBC incorporates specific passenger flow demand information, enriching the original BC measurement. This study utilizes FBC to measure station importance for different social groups,

where \({FBC}(v)\) represents the FBC of node \(v\), \({\sigma }_{s,t}\) is the number of shortest paths between node \(s\) and node \(t\) and \({\sigma }_{s,{t|v}}\) is the number of shortest paths that pass node \(v\); \({A}_{{total}}\) and \({A}_{s,t}\) denote each social group’s total O-D flow in the network for and flow from node \(s\) and node \(t\) respectively. To quantify the heterogeneity of the system’s FBC distribution for each group, we use the Gini coefficient (Gini)64, denoted as \({G}_{{WB}}\), whose equation is shown as follows,

Where \({FBC}\) denotes the set of network index values of nodes, with \({{FBC}}_{i}\) representing the ith smallest centrality value. \(V\) refers to the set of nodes, with \({|V|}\) represents the total number of nodes in the network.

For instance, in a centralized star network, the Gini index of BC (\({G}_{B})\) would reach its maximum value of 1, reflecting a high level of inequality in node importance from a topological standpoint. Conversely, in an egalitarian lattice network where nodes share equal importance, \({G}_{B}\) would approach its minimum value of 0. This signifies a homogeneous distribution and suggests enhanced preparedness when solely considering the topology. To enhance clarity, this work introduces a transformed index, 1-GINI, to directly represent preparedness, as higher \({G}_{B}\) values indicate lower levels of preparedness. In this transformed index, higher 1-GINI values correspond to better preparedness performance.

Network robustness

We assess the system’s robustness by examining its ability to sustain functionality for each group amidst successive node failures. Implementing node percolation, involving the sequential removal of nodes, facilitates the ongoing monitoring of functional changes and the observation of the system’s robustness to continuous disruptions as nodes are progressively eliminated from the network12,65. The functionality is continuously assessed using a degradation curve to track the system’s residual functionality following each node removal. The predefined order is determined by either Random choice or by descending order of metrics, specifically the FBC and the ND. The area under this curve, \({r}_{b}\), calculated using integral methods after the removal of all nodes, serves as a quantified indicator of robustness. A slower degradation rate from the figure and a larger area indicate a better robustness performance, which signifies the system’s ability to sustain higher functionality despite continuous disruptions. Therefore, network robustness is quantified as:

where the functionality (\({F}_{0}\)) accounts for the travel demand of social groups, representing the aggregate passenger flow that can be accommodated within the impaired system topology. During disruption simulations, functionality \(F\left(c\right)\) is assessed based on the fraction of nodes removed \(c\), reflecting the impaired system’s capacity. \(F\left(c\right)\) is normalized by \({F}_{0}\), and robustness \({r}_{b}\), ranging from 0 to 1, is used to quantify system performance, with higher values denoting better system robustness.

Network recovery

To evaluate the system’s recovery potential for each social group, we priorities the capacity to aid passenger relocation in response to disruptions. Stations demonstrate better short-term recovery capabilities by enabling convenient passenger relocation to nearby stations to continue their journey20. The relocation process involves several factors influencing individuals’ choices, yet we emphasize two primary determinants: the walking distance to alternative neighboring stations and the connectivity with the trip destination. With the ‘distance-decay effect’ illustrated by previous research66, we employ a negative linear distance-decay curve to estimate passengers’ willingness to walk to neighboring stations following a station disruption20,66:

where \({{DF}}_{i,n}\) refers to the distance factor, reflecting passengers’ willingness to walk to a neighboring station situated at a distance of \({l}_{i,n}\). The parameter \({d}_{{Max}}\) signifies a given social group’s maximum acceptable walking distance. Research findings indicate that most passengers are reluctant to walk distances exceeding 1.6 km to access metro systems66, whereas He et al.51 discovered a U-shaped correlation between age groups and their walking distances to metro stations. Thus, we employ this age-dependent distance ratio to define customized maximum walking distances for different age groups.

To assess trip destination accessibility, we analyze the system’s topological connectivity during station disruptions. Specifically, we scrutinize the connectivity between the neighboring stations of departure node \(i\) and the destination node \(j\) for the O-D flow between these two nodes. We prioritize relocating the flow to the neighboring station that demonstrates the highest \({{DF}}_{i,n}\) among the destination connected stations. We therefore assess the proportion of passengers capable of remaining within the metro system following the relocation necessitated by a single station disruption. This metric serves as an indicator of the system’s recovery capability. For the O-D flow from the departure node \(i\) to destination node \(j\), an equation of relocation flow is given considering the walking willingness \({{DF}}_{i,n}\) and the accessible neighbor station.

where \({{Rl}}_{i,{|ij}}\) stands for the portion of flow \({F}_{i,j}\) that can be redirected to neighboring stations, \({F}_{i,n}\) signifies the flow that could potentially be directed to a valid neighboring station \(n\), while the \({{DF}}_{i,n}\) represents the walking willingness corresponding to that specific neighboring station \(n\).

Demographical factor

Due to the limited data on socio-demographic features from the Travel Characteristics Survey 201161, our analysis focuses solely on gender, age, and income attributes to demonstrate the framework’s applicability. The demand flow is delineated across seven age groups: individuals aged 3–14, those aged 14–24, 24–34, 34–44, 44–54, 54–64, and individuals over 64. Moreover, the flow is categorized into three income groups: individuals from households earning below HK$15,000 monthly, those earning between HK$15,001 and HK$30,000, and households earning above HK$30,000 monthly. Furthermore, to precisely identify vulnerable groups, we conduct a demographic analysis by categorizing individuals according to age and gender. Income is not included in the grouping criteria due to the exclusion of certain individuals from the investigation.

Data availability

The relevant datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. D. (https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/urbanization-0#:~:text=The%20world%20is%20becoming%20increasingly,around%20two%2Dthirds%20in%202050.).

Reduction, U. N. O. f. D. R. (Geneva, 2022).

Coleman, N., Esmalian, A. & Mostafavi, A. Equitable resilience in infrastructure systems: empirical assessment of disparities in hardship experiences of vulnerable populations during service disruptions. Nat. Hazards Rev. 21, 04020034 (2020).

Council, A. T. & Council, A. T. Critical assessment of lifeline system performance: understanding societal needs in disaster recovery. (US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2016).

Linkov, I. & Trump, B. D. The science and practice of resilience. (Springer, 2019).

Soufi, H. R., Esfahanipour, A. & Shirazi, M. A. Risk reduction through enhancing risk management by resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 64, 102497 (2021).

Mahoney, E., Golan, M., Kurth, M., Trump, B. D. & Linkov, I. Resilience-by-design and resilience-by-intervention in supply chains for remote and indigenous communities. Nat. Commun. 13, 1124 (2022).

Woods, D. D., Chan, Y. J. & Wreathall, J. In: 5th Resilience Engineering Symposium. 17–22 (2014).

Linkov, I., Trump, B. D., Golan, M. & Keisler, J. M. Enhancing resilience in post-COVID societies: by design or by intervention?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 4202–4204 (2021).

Bruneau, M. et al. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra 19, 733–752 (2003).

Ouyang, M., Dueñas-Osorio, L. & Min, X. A three-stage resilience analysis framework for urban infrastructure systems. Struct. Saf. 36, 23–31 (2012).

Xu, Z. & Chopra, S. S. Network-based assessment of metro infrastructure with a spatial–temporal resilience cycle framework. Reliab Eng. Syst. Safe 223, 108434 (2022).

Wang, Y., Zhao, O. & Zhang, L. Multiplex networks in resilience modeling of critical infrastructure systems: a systematic review. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe, 110300 (2024).

Barabási, A.-L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1999).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Ash, J. & Newth, D. Optimizing complex networks for resilience against cascading failure. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 380, 673–683 (2007).

Derrible, S. & Kennedy, C. The complexity and robustness of metro networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 389, 3678–3691 (2010).

Haritha, P. & Anjaneyulu, M. Comparison of topological functionality-based resilience metrics using link criticality. Reliab Eng. Syst. Safe 243, 109881 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Percolation transition in dynamical traffic network with evolving critical bottlenecks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 669–672 (2015).

Chopra, S. S., Dillon, T., Bilec, M. M. & Khanna, V. A network-based framework for assessing infrastructure resilience: a case study of the London metro system. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160113 (2016).

Serdar, M. Z., Koç, M. & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Urban transportation networks resilience: indicators, disturbances, and assessment methods. Sustain Cities Soc. 76, 103452 (2022).

Global mobility report 2017 : tracking sector performance (English). Global mobility report series Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/920101508269072500 (2017).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable transport. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Retrieved Jan, 2025, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabletransport (2021).

Didier, M., Broccardo, M., Esposito, S. & Stojadinovic, B. A compositional demand/supply framework to quantify the resilience of civil infrastructure systems (Re-CoDeS). Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 3, 86–102 (2018).

Almoghathawi, Y., Barker, K. & Albert, L. A. Resilience-driven restoration model for interdependent infrastructure networks. Reliab Eng. Syst. Safe 185, 12–23 (2019).

Donovan, B. & Work, D. B. Empirically quantifying city-scale transportation system resilience to extreme events. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 79, 333–346 (2017).

Diab, E. & Shalaby, A. Metro transit system resilience: understanding the impacts of outdoor tracks and weather conditions on metro system interruptions. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 14, 657–670 (2020).

Ganin, A. A. et al. Resilience in intelligent transportation systems (ITS). Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 100, 318–329 (2019).

Yang, Y., Ng, S. T., Zhou, S., Xu, F. J. & Li, H. In: ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering. 563–569 (American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA, 2019).

Ye, Q. & Ukkusuri, S. V. Resilience as an objective in the optimal reconstruction sequence for transportation networks. J. Transp. Saf. Secur.7, 91–105 (2015).

Zhang, D. -m et al. Resiliency assessment of urban rail transit networks: Shanghai metro as an example. Saf. Sci. 106, 230–243 (2018).

Li, Z., Jin, C., Hu, P. & Wang, C. Resilience-based transportation network recovery strategy during emergency recovery phase under uncertainty. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe 188, 503–514 (2019).

Xu, Z., Chopra, S. S. & Lee, H. Resilient urban public transportation infrastructure: a comparison of five flow-weighted metro networks in terms of the resilience cycle framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 12688–12699 (2021).

Rufat, S., Tate, E., Burton, C. G. & Maroof, A. S. Social vulnerability to floods: Review of case studies and implications for measurement. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 14, 470–486 (2015).

Salvati, P. et al. Gender, age and circumstances analysis of flood and landslide fatalities in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 610, 867–879 (2018).

Fox, N., Tilt, J. H., Ruggiero, P., Stanton, K. & Bolte, J. Toward equitable coastal community resilience: Incorporating principles of equity and justice in coastal hazard adaptation. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 1, e36 (2023).

Coleman, N., Li, X., Comes, T. & Mostafavi, A. Weaving equity into infrastructure resilience research: a decadal review and future directions. npj Nat. Hazards 1, 25 (2024).

Forsyth, T., McDermott, C. L. & Dhakal, R. What is equitable about equitable resilience? Dynamic risks and subjectivities in Nepal. World Dev. 159, 106020 (2022).

Arabi, M., Gerasimidis, S., Barchers, C. & Oke, J. Resilience in multilayer transportation infrastructure networks: a review and conceptual framework for equity-based assessment. Sustain. Resil. Infras. 1–24 (2024).

Dong, S., Esmalian, A., Farahmand, H. & Mostafavi, A. An integrated physical-social analysis of disrupted access to critical facilities and community service-loss tolerance in urban flooding. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 80, 101443 (2020).

Coleman, N., Li, X., Comes, T. & Mostafavi, A. Weaving equity into infrastructure resilience research and practice: a decadal review and future directions. npj Nat. Hazards 1, 25 (2023).

Transport Department of the Government of Hong Kong. Annual Transport Digest (2019).

Edith Lin, J. L. a. O. L. Typhoon Koinu airport chaos: Hong Kong authorities pledge to improve transport arrangements in extreme weather after train service halt leaves thousands stranded, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/transport/article/3237254/typhoon-koinu-airport-chaos-hong-kong-system-be-reviewed-after-thousands-left-stranded-shutdown (2023).

Jacob, R., Harikrishnan, K., Misra, R. & Ambika, G. Measure for degree heterogeneity in complex networks and its application to recurrence network analysis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160757 (2017).

Szeto, W., Yang, L., Wong, R., Li, Y. & Wong, S. Spatio-temporal travel characteristics of the elderly in an ageing society. Travel Behav. Soc. 9, 10–20 (2017).

Currie, G. & Stanley, J. No way to go: transport and social disadvantage in Australian communities. Monash University Press (2007).

Grant-Smith, D., Edwards, P. & Johnson, L. In: Association of European Schools of Planning (AESOP) 26th Annual Congress (2012).

Leung, K. Y. & Loo, B. P. Association of children’s mobility and wellbeing: a case study in Hong Kong. Travel Behav. Soc. 9, 95–104 (2017).

Karácsonyi, D., Taylor, A. & Bird, D. The demography of disasters: impacts for population and place. (Springer Nature, 2021).

Tao, S., He, S. Y., Kwan, M.-P. & Luo, S. Does low income translate into lower mobility? An investigation of activity space in Hong Kong between 2002 and 2011. J. Transp. Geogr. 82, 102583 (2020).

He, J., Zhang, R., Huang, X. & Xi, G. Walking access distance of metro passengers and relationship with demographic characteristics: a case study of Nanjing metro. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 28, 612–623 (2018).

Poverty, C. o. Report on the commission on poverty: Chapter 8. (2017).

Petrini, C. Triage in public health emergencies: ethical issues. Intern. Emerg. Med. 5, 137–144 (2010).

Brennan, A. & Lo, Y-S. Environmental ethics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (ed.Zalta, E. N.). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-environmental/ (2002).

Mandle, J. Rawls’s’ A theory of justice’: an introduction. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Epting, S. The moral dimensions of infrastructure. Sci. Eng. Ethics 22, 435–449 (2016).

Rivera, D. Z. Unincorporated and underserved: critical stormwater infrastructure challenges in South Texas Colonias. Environ. Justice 16, 203–209 (2023).

Eghdami, S., Scheld, A. M. & Louis, G. Socioeconomic vulnerability and climate risk in coastal Virginia. Clim. Risk Manag. 39, 100475 (2023).

Fitzgibbons, J. & Mitchell, C. L. Just urban futures? Exploring equity in “100 Resilient Cities”. World Dev. 122, 648–659 (2019).

Arnstein, S. R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 35, 216–224 (1969).

Department, T. Travel Characteristics Survey 2011 - Final Report (2014).

Von Ferber, C., Holovatch, T., Holovatch, Y. & Palchykov, V. Public transport networks: empirical analysis and modeling. Eur. Phys. J. B 68, 261–275 (2009).

Brandes, U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J. Math. Sociol. 25, 163–177 (2001).

Hu, H.-B. & Wang, X.-F. Unified index to quantifying heterogeneity of complex networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 387, 3769–3780 (2008).

Berche, B., Von Ferber, C., Holovatch, T. & Holovatch, Y. Resilience of public transport networks against attacks. Eur. Phys. J. B 71, 125–137 (2009).

O’Sullivan, S. & Morrall, J. Walking distances to and from light-rail transit stations. Transp. Res. Rec. 1538, 19–26 (1996).

Liévanos, R. S. & Horne, C. Unequal resilience: the duration of electricity outages. Energy Policy 108, 201–211 (2017).

Logan, T. M. & Guikema, S. D. Reframing resilience: equitable access to essential services. Risk Anal. 40, 1538–1553 (2020).

Hewawasam, V. & Matsui, K. Equitable resilience in flood prone urban areas in Sri Lanka: a case study in colombo divisional secretariat division. Glob. Environ. Change 62, 102091 (2020).

Esmalian, A., Wang, W. & Mostafavi, A. Multi-agent modeling of hazard–household–infrastructure nexus for equitable resilience assessment. Comput.-Aided Civ. Inf. Eng. 37, 1491–1520 (2022).

Fan, C., Jiang, X., Lee, R. & Mostafavi, A. Equality of access and resilience in urban population-facility networks. npj Urban Sustain. 2, 9 (2022).

Karakoc, D. B., Barker, K., Zobel, C. W. & Almoghathawi, Y. Social vulnerability and equity perspectives on interdependent infrastructure network component importance. Sustain. Cities Soc. 57, 102072 (2020).

Zhang, T., Niu, C., Nair, D. J., Dixit, V. & Waller, S. T. Equity analysis and improvement in transportation resilience optimisation at the pre-event stage. Transp. Res. D: Trans. Environ. 122, 103892 (2023).

Dargin, J. S. & Mostafavi, A. Human-centric infrastructure resilience: Uncovering well-being risk disparity due to infrastructure disruptions in disasters. PloS One 15, e0234381 (2020).

Ulak, M. B., Yazici, A. & Ozguven, E. E. A prescriptive model to assess the socio-demographics impacts of resilience improvements on power networks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 51, 101777 (2020).

Contributors, O. OpenStreetMap, https://www.openstreetmap.org/.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the detailed and insightful comments of Assistant Professor Venera R. Khalikova from the Department of Anthropology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, which have greatly improved our work by enhancing its social science perspective.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: F.Y.C. and S.S.C.; writing original and visualization: F.Y.C.; writing–review & editing, funding acquisition, and supervision: S.S.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Chopra, S.S. Integrating socio-demographic factors for equitable resilience in networked-urban infrastructure systems. npj Urban Sustain 5, 23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00195-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00195-y