Abstract

Recently, China has undergone rapid urbanization in terms of population and urban land growth. However, there are notable lags in the people-oriented dimensions of urbanization, including urban social services, environmental services, and socioeconomic equity, which are crucial for achieving SDG11 (sustainable cities and communities). Here, considering the complex dimensions of urbanization, we examined 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators across four dimensions, namely, economic, social, environmental, and equity dimensions, from 2005 to 2020, and their relationships with population/land urbanization at multiple scales (national, regional, and urban agglomeration scales), and among different city sizes, via the paired t test and the evenness index. Notably, between 2005 and 2020, these urbanization indicators of China showed an overall upward trend, with changes ranging from 1.09 to 53.95 times. Among the 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators, the economic and social indicators lagged behind the land and population urbanization, whereas the environmental indicators caught up. The evenness index among these indicators showed a U-shaped change pattern, which indicated that people-oriented urbanization was coming up with population/land urbanization since the implementation of China new-type urbanization plan in 2014 until 2020. In the future, increasing investment in social service systems and implementing place-based coordination strategies are necessary to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s urbanization trajectory since the 1978 Reform and Opening-up policy illustrates both the opportunities and challenges in rapid urban development. The urban population ratio in China has increased from 17.9% in 1978 to 65.2% in 2020, and the urban built-up area has increased from 7438 km² in 1978 to 60,721 km2 in 2020, with an annual growth of 1268 km2 1. The rapid urban population and land area expansion have promoted increasingly active socio-economic activities. However, providing people-oriented urbanization involving social security, education, healthcare, and environmental services for citizens entering cities has become a bottleneck in development, leading to economic, social, and ecological issues2,3,4. For example, challenges include providing basic public services to new urban residents5,6,7, increased urban‒rural disparities8,9, unplanned urban land expansion causing environmental pollution and ecological destruction10, and issues such as traffic congestion and housing shortages due to insufficient urban governance capacity levels11. These issues are not limited in China but also found in other countries (such as India and Brazil) from Global South. Therefore, empirical research is urgently needed to examine the dynamic interactions among the three dimensions of urbanization to provide theoretical insights and data support for advancing more equitable and sustainable urbanization pathways in China and other developing countries.

In March 2014, the Chinese government issued the National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020) to transform traditional extensive urbanization into high-quality urbanization in China12,13. Under this development strategy, people-oriented urbanization is the core of the New-Type Urbanization Plan2,11,14,15. People-oriented urbanization represents a development paradigm that places human needs and well-being at the core of urban planning and growth. This urban development concept prioritizes equitable access to public services, sustainable economic opportunities, and inclusive governance, ensuring that urban development benefits all residents16,17,18,19. Such people-oriented urbanization process can fundamentally reshape social structures and lifestyles, promote the refinement of the social division of labor, enhance the quality of public services, and foster innovative cultural integration, thereby providing endogenous momentum for sustainable urban development20,21. This Plan is also aligned with SDG 11, which is to improve the quality of life, promote the equitable allocation of social resources, and ensure that urbanization encompasses not only the expansion of land and population but also the comprehensive enhancement of social welfare22,23.

Research on urbanization has focused primarily on quantifying urban land and population dynamics. Urban land urbanization (land urbanization hereafter) studies have extensively involved using remote sensing data and analyzing indicators such as the total area, growth rate, and per capita urban land usage to examine urbanization patterns from 1990 to 2020. These analyses have revealed that land urbanization progresses through distinct phases: initial slow growth, acceleration, and deceleration24,25,26. In population urbanization research, census data have been mainly employed to analyze spatiotemporal patterns and heterogeneity in urbanization rates, thereby examining the influences of economic development, household registration policies, and urban‒rural income disparities5,27. Researchers have employed various analytical methods, including the coefficient of variation, spatial autocorrelation, and degree of coupling coordination, to evaluate the relationships between population and land urbanization across regions28,29,30. Comparative analyses of land and population urbanization have demonstrated that land urbanization consistently exceeds population growth, resulting in inefficient urban sprawl, environmental deterioration, and uninhabited development. Recent studies of Chinese prefecture-level cities based on census data have revealed urban sprawl patterns from 1990 to 2020, noting a transition from rapid expansion to gradual deceleration, although small- and medium-sized cities in western China continue to experience significant sprawl31,32. Yang et al.33 examined the coordinated development of population and land urbanization across 284 prefecture-level Chinese towns. They identified a decreasing spatial gradient of coordination from eastern coastal areas to inland regions, although regional differences decreased over the study period33. While the evolution and spatial heterogeneity of land and population urbanization have been extensively studied, there is still a lack of research incorporating people-oriented urbanization into an integrated, multidimensional analytical framework.

Another line of research focused scaling relation between various urban indicators and population or urban land area34,35 to understand urban evolution mechanism and formulate development strategies36. For example, Bettencourt et al.37 identified consistent power-law relationships between city population size and various social, economic, and environmental indicators37. Elliott et al.38 revealed that in the expansion of U.S. cities, innovation and wealth creation exhibit superliner growth, while infrastructure shows sublinear growth. Zhou et al.39 also confirmed that as the size of Chinese cities increases, the growth of infrastructure tends to slow down39. Yang et al.40 found a linear relationship between CO2 emissions and population size and built-up area40. Xu et al.41 observed that during the evolution of the African urban system from 1950 to 2020, larger cities tend to have lower land-use efficiency41. The results indicate that while urban expansion enhances efficiency, it also exacerbates resource strain, environmental pressure, and governance challenges. Within this scaling context, the scaling relation between indicators of people-oriented indicators and city size can be used to guide policy making on urban expansion and socio-ecological sustainability38,42,43,44.

Scholars of people-oriented urbanization have focused on several interlocking challenges: absorbing the agricultural population into cities, reforming the household registration (hukou) system, equalizing access to public services, and fostering coordinated urban‒rural development. Kassiola45 exposed the social-equity dilemmas that rapid urban expansion poses for rural migrants entering metropolitan labor markets45. Building on this work, Sun et al.46 demonstrated how hukou reforms in China still leave migrant families at a disadvantage when seeking schooling and healthcare of comparable quality46. Yang et al.27 then showed that urban‒rural integration stalls and regional disparities widen without deliberate mechanisms for sharing resources across jurisdictions27. Most recently, Bai and Shi15 contended that China has reached a demographic and economic crossroads: to meet Sustainable Development Goal 11, the country must pivot from land-driven growth to a quality-led, people-oriented renewal that weaves equity into every stage of urban and rural planning15. Despite significant progress in promoting people-oriented urbanization, a critical yet under-explored issue remains in understanding the nuanced, multidimensional relationships between people-oriented urbanization and its population- and land-related dynamics. This knowledge deficit potentially compromises the achievement of SDG11 and urban sustainability.

Against this research gap, this study aimed to systematically evaluate the relationships between people-oriented urbanization and population and land urbanization in China. The research question is whether people-oriented urbanization was catching up with rapid population/land urbanization in China between 2005 and 2020. By constructing a comprehensive evaluation system for people-oriented urbanization comprising 16 indicators across four critical dimensions—economic, social, environmental, and equity—descriptive statistical analysis was employed to elucidate the comprehensive characteristics of urbanization across different categories. Multiple analytical methods, including paired t tests, 45° linear analysis, and multiple fitting analysis, were applied to assess the complex associations between urbanization dimensions, thereby investigating the lagging or leading relationship. An enhanced radar chart method was utilized to calculate the evenness index, thereby quantifying the degree of coordinated development in urbanization (see “Methods” for details). This approach revealed regional and city-size variations in the relationship between people-oriented urbanization and population/land urbanization. At last, targeted policy recommendations were generated to optimize public services, enhance social inclusiveness, promote regional coordinated development, and improve residents’ quality of life, thereby aiming to achieve the SDG11 targets. The findings provide robust scientific evidence and data support for achieving urban sustainability in China and developing countries in the global South.

Results

Overall characteristics of multidimensional urbanization

From 2005–2020, the urbanization level in China increased substantially, with all indicators demonstrating an increasing trend. Population urbanization across prefecture-level cities increased from 40.2 to 62.2%, representing a base-period growth rate of 154.6% between 2005 and 2020. Land urbanization increased from 167.7 km2 to 312.8 km2, achieving a base-period growth rate of 186.5%, exceeding population urbanization.

The four categories of people-oriented urbanization demonstrated an overall upward trend, with base-period growth rates ranging from 109.0% to 5394.6% (Fig. 1). The social and economic indicators exhibited the greatest growth, with mean base-period growth rates of 1341.0% and 446.4%, respectively, surpassing both the population and land urbanization growth rates. The social investment indicators, including research and development expenditure per capita (R&DEP), education expenditure per capita (EEP), and fixed asset investment per capita (FAI), achieved base-period growth rates exceeding 500%. In contrast, the environmental and equity-related indicators showed relatively modest growth, with mean base-period growth rates of 133.3% and 113.5%, respectively, falling below the population and land urbanization growth rates. Notable examples of slow growth include the urban‒rural income ratio (URIR, 109.0%), the housing price-to-income ratio (HPIR, 109.0%), the unemployment rate (UPR, 115.0%), and the Gini coefficient (Gini, 117.9%).

a Spatial map depicting the change in each indicator from 2005 to 2020, with x-axis and y-axis representing the values in 2020 and 2005, respectively. b Annual trends of each indicator from 2005 to 2020. The indicators are organized into five categories: land and population urbanization indicators (PU population urbanization, LU land urbanization), economic indicators (AD average deposit, AW average wage, CEP consumption expenditure per capita, FAI fixed asset investment per capita, GDPP - Gross Domestic Product per capita, HPIR house price-to-income ratio), social infrastructure indicators (EEP—education expenditure per capita, GSP—green space per capita, PP - physicians per 1000 people, R&DEP—research and development expenditure per capita, UPR - unemployment rate), environmental and management indicators (NHTR - nonhazardous treatment rate of domestic waste, PM2.5- PM2.5 concentration, SDE sulfur dioxide emissions from industry), and social equity indicators (Gini coefficient, URIR urban-rural income ratio).

Differences in urbanization indicators across the different regions

The regional analysis revealed that most indicators exhibit an east-west gradient, characterized by higher values and high growth rates in the east (Fig. 2). Of the 18 urbanization indicators examined, 12 followed this pattern. The eastern region yielded the highest values of the average deposit (AD), average wage of employees (AW), consumption expenditure per capita (CEP), education expenditure per capita (EEP), fixed asset investment per capita (FAI), gross domestic product per capita (GDPP), green space per capita (GSP), household price‒income ratio (HPIR), land urbanization, nonhazardous treatment rate of domestic waste (NHTR), physicians per 1000 people (PP), research and development expenditures per capita (R&DEP), and sulfur dioxide emissions from industry (SDE). Notably, the R&DEP in the eastern region significantly exceeded that in the other regions, surpassing that in the northeastern, central, and western regions by 444.1%, 181.8%, and 383.7%, respectively. Similar patterns emerged for land urbanization (134.6%, 180.0%, 294.2%) and AD (113.5%, 168.4%, 124.5%). The NHTR exhibited minimal regional variation, with the values in the eastern region exceeding those in the northeastern, central, and western regions by only 12.6%, 10.2%, and 10.9%, respectively. The PM2.5 concentration (PM2.5) peaked in the central region, exceeding those in the northeastern, western, and eastern regions by 38.3%, 35.1%, and 33.5%, respectively. Regarding social equity indicators, the UPR peaked in the northeastern region, surpassing those in the eastern, central, and western regions by 38.9%, 12.0%, and 7.1%, respectively. The western region presented the highest Gini and URIR, which exceeded the values in the eastern region by 49.6% and 28.6%, respectively. Specific indicators demonstrated distinct patterns, such as the increase in PM2.5 in the northern and western regions but a decrease in the eastern coastal provinces, and the value of the Gini increased in Heilongjiang Province but decreased in the central region of small cities.

For each box plot, the dash line indicates the median value; the box depicts the interquartile range, and the whiskers extending to 1.5 times the interquartile range. The outliers are represented by dots. The y-axis scales are adjusted for each indicator to accommodate different measurement units and value ranges. The abbreviation for each indicator is shown in Fig. 1.

At the city scale, large cities exhibited advantages across most indicators during the study period. Most people-oriented urbanization indicators, except property price and environmental indicators (HPIR, PM2.5, and SDE), peaked in the eastern region. Land urbanization demonstrated the highest spatial variation, with the values in large cities exceeding those in small- and medium-sized cities by 532.9% and 213.9%, respectively. The R&DEP and AD exhibited the largest spatial differences, ranging from 178.3% to 391.9%. The NHTR demonstrated minimal spatial variation, with the values in large cities surpassing those in small- and medium-sized cities by only 13.4% and 8.0%, respectively. The values of the social and equity-related indicators, including the Gini, UPR, and URIR, were highest in small cities. Specifically, the Gini (23.6%, 10.6%), UPR (10.4%, 5.8%), and URIR (10.0%, 1.4%) values in small cities exceeded those in large and medium-sized cities.

Urban agglomerations exhibited higher mean values across most indicators than non-urban agglomerations. Except for the housing price and environmental indicators (HPIR, PM2.5, and SDE), all indicators peaked in urban agglomeration areas. The R&DEP exhibited the most significant difference, with the values of urban agglomerations exceeding those of non-urban agglomerations by 200.6%. The HPIR and AD also showed substantial differences, with those of urban agglomerations surpassing those in non-urban agglomerations by 181.9% and 144.2%, respectively. Conversely, the values of the social equity indicators (Gini, URIR, and UPR) were higher in non-urban agglomerations, exceeding those in urban agglomerations by 17.5%, 9.4%, and 6.9%, respectively.

Differences between people-oriented urbanization and population urbanization

Most people-oriented urbanization indicators demonstrated significant nonlinear relationships with population urbanization. The paired t test analysis revealed significant differences between the progress value and base-period growth rate of the 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators and population urbanization (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Most people-oriented urbanization indicators lagged behind population urbanization. The economic and social indicators of AD, AW, CEP, FAI, GDPP, EEP, GSP, PP, R&DEP, and Gini mainly indicated data points below the 45° line. Conversely, the other environmental (NHTR, PM2.5, and SDE), economic (HPIR), and social and equity (UPR and URIR) indicators demonstrated data points above the 45° line.

PU - population urbanization is represented on the x-axis, and the 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators are represented on the y-axis. The red fitted regression line is based on the best R² value obtained from linear, quadratic, cubic, logarithmic, and exponential fitting methods. The abbreviation for each indicator is shown in Fig. 1.

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed monotonic positive relationships between most people-oriented urbanization indicators and population urbanization. Economic indicators (AD, AW, CEP, FAI, and GDPP) and social indicators (EEP and PP) demonstrated significant positive correlations with population urbanization. Other indicators, however, exhibited nonmonotonic relationships. In the environmental dimension, the relationship between population urbanization and the NHTR displayed an inverted U-shaped pattern, characterized by significant initial increases in the NHTR during early urbanization, followed by deceleration or decline at higher population urbanization levels. The social dimension indicators GSP and R&DEP showed exponential relationships, with high-population-urbanization cities demonstrating decisive advantages. The relationships between population urbanization and PM2.5, SDE, HPIR, and UPR remained relatively stable.

Differences between people-oriented urbanization and land urbanization

Similar significant differences and nonlinear relationships occurred between the people-oriented and land urbanization indicators (Fig. 4), with the people-oriented indicators mainly lagging behind the land urbanization indicators. Economic indicators (AD, AM, CEP, FAI, and GDPP) and social indicators (EEP, GSP, PP, and R&DEP) demonstrated data points below the 45° line. Conversely, other environmental indicators (UPR, NHTR, PM2.5, and SDE) and equity indicators (Gini and URIR) demonstrated data points above the 45° line.

LU land urbanization is represented on the x-axis, and the 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators are represented on the y-axis. The red fitted regression line is based on the best R² value obtained from linear, quadratic, cubic, logarithmic, and exponential fitting methods. The abbreviation for each indicator is shown in Fig. 1.

Nonlinear fitting analysis revealed diverse relationships between these indicators and land urbanization. Some economic indicators (AD, AW, CEP, and GDPP) demonstrated mainly linear positive correlations with land urbanization, although the growth rate slightly fluctuated with increasing urbanization levels. Similarly, the social indicators (EEP, PP, and R&DEP) were positively correlated with land urbanization. PM2.5 and SDE displayed relatively stable relationships with land urbanization in the environmental dimension. Notably, equity indicators (Gini and URIR) and select economic and social indicators (FAI, GSP, and NHTR) exhibited pronounced inverted U-shaped relationships, peaking during the intermediate phase of land urbanization before declining.

Evenness of multidimensional urbanization indicators

We applied an evenness index to measure the coordinated development of urbanization. The analysis of urbanization indicators in China (Fig. 5a) revealed a U-shaped trend in development evenness, which declined from 55.01 in 2005 to its nadir of 53.24 in 2011 before increasing to 55.53 in 2020, representing a 4.30% increase over the decade. The development evenness peaked in 2020 (55.53) and its minimum in 2011 (53.24). This metric exhibited a declining trend between 2005 and 2011, followed by a gradual recovery from 2012, with accelerated growth after 2014.

a The evenness index of the progress value of urbanization indicators from 2005 to 2020, with error bars representing the standard deviations. b The evenness index of the base-period growth rate of urbanization indicators from 2006 to 2020. c The progress values of 18 urbanization indicators across four years. The shaded area highlights the overall pattern of urbanization development across different dimensions.

The interannual analysis of the base-period growth rate evenness revealed a distinct sharp decline–trough–slow recovery pattern from 2006 to 2020 (Fig. 5b). The evenness measure reached 66.61 in 2006 before plummeting to 36.76 in 2007, representing a 29.8% decline. A gradual downward trend followed this until it reached its minimum value of 34.98 in 2011. This metric exhibited modest recovery after 2011, with pronounced growth acceleration after 2014, increasing from 35.43 to 37.39 in 2020—a 6.91% increase. This trajectory indicates China’s transition from rapid but unbalanced urbanization toward a more coordinated development model, although substantial room for improvement remains (Fig. 5c).

Regional analysis revealed similar U-shaped development trends across the eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions (Fig. 6). Northeast China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning) maintained superior development evenness, consistently exceeding 55 from 2005 to 2020. The western region followed, with values ranging from 53 to 56, although notable fluctuations were observed, particularly in southwestern provinces (Yunnan, Sichuan, and Chongqing) from 2010 to 2012. While the eastern and central regions initially demonstrated lower performance, they have exhibited steady improvement since 2013, notably in southeastern coastal provinces such as Guangdong and Guangxi, suggesting the successful implementation of coordinated urban development strategies.

Analysis at the city scale also exhibited U-shaped patterns in development evenness across the different urban categories. Small cities demonstrated the highest overall evenness, maintaining values between 53 and 57 and showing consistent growth after 2013. Medium-sized cities ranked second, recovering after a temporary decline from 2010–2012. Despite lower evenness values, large cities displayed temporal patterns similar to those of their smaller counterparts. From the perspective of urban agglomerations, the results showed greater development evenness in non-agglomeration regions than in urban agglomerations. Both regional categories experienced an inflection point from 2012–2013, followed by sustained growth, coinciding with implementing the New-Type urbanization policy.

Evenness analysis of the base-period growth rates of the urbanization indicators (Fig. 7) revealed a pattern of a sharp initial decline followed by a gradual recovery, exhibiting distinct spatial heterogeneity. In 2006, China demonstrated highly coordinated development across all regions, with the eastern region leading (70.43), followed by the central (67.25), western (63.87), and northeastern areas (62.14). City-scale analysis indicated the highest degree of coordination in large cities (70.99), followed by medium-sized cities (66.36), with small towns showing the lowest values (61.27).

a The spatial distribution of the evenness index of the base-period growth rate in 2007, 2013, and 2020. b The evenness index of the base-period growth rate trends among regions, city sizes, and urban agglomeration division. Each center point represents the mean value, and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

After 2007, the various regions exhibited different patterns in their declines in evenness measures. Small cities maintained relatively high stability (36–39), whereas large cities stabilized at relatively low levels (34–36). Regional analysis revealed that the northeastern region achieved greater evenness despite significant volatility, whereas the eastern region demonstrated consistent values (34–36). Compared with urban agglomerations (36.77 in 2020), non-agglomeration areas maintained greater evenness (38.89 in 2020), with an increasing difference between these zones.

After 2013, most regions demonstrated modest increases in evenness measures. The northeastern region exhibited the greatest improvement, increasing from 35.91 in 2014 to 41.55 in 2020. Small cities showed similar progress, rising from 36.07 to 39.23, whereas the value in non-agglomeration areas increased from 35.46 to 38.89 during the same period. However, the eastern region, large cities, and urban agglomerations displayed marginal improvements (2.22%, 3.76%, and 3.81%, respectively), maintaining relatively low evenness values.

Robustness test

To ensure the robustness of the land urbanization indicator we selected, we performed a comparative analysis using other indicators: urban built-up area as a proportion of city area, urban built-up area, and per capita urban built-up area. Correlation analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between these indicators, suggesting they are generally consistent (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also re-estimated the concentration index using these alternative indicators, and the conclusions remained consistent with those based on the total urban built-up area (Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings support our use of the total urban built-up area as the measure of land urbanization, as it comparably and accurately reflects land urbanization process across cities with varying sizes.

To assess the robustness of our evenness index findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using eight different weighting methods: equal weights (baseline), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), entropy, CRITIC, Coefficient of Variation (CV), TOPSIS, Standard Deviation (SD), and mean weights (Supplementary Fig. 4). The results demonstrate remarkable robustness. The U-shaped temporal pattern persisted across all eight methods, with minimum points occurring between 2006–2011, depending on the weighting approach. Crucially, the post-2013 recovery trend remained consistent across all methods, confirming that the improvement following the 2014 New-Type Urbanization Plan is not an artifact of our weighting assumptions. City-size disparities also proved highly robust regardless of the weighting method. Specifically, small cities generally exhibited higher evenness than large cities.

Discussion

Some people-oriented urbanization indicators performed well. The analysis revealed an upward trend across all urbanization indicators (people-oriented, land urbanization, and population urbanization), indicating consistent advancement across economic development, population mobility, and people-oriented elements, thus reflecting comprehensive progress in the urbanization process. This study revealed significant positive correlations between people-oriented urbanization and land and population urbanization indicators, suggesting that higher degrees of land and population urbanization correlate with enhanced people-oriented characteristics, particularly in terms of human well-being, quality of life, and social services. This correlation stems from the increased efficiency in resource allocation, enhanced infrastructure development, and expanded social welfare coverage facilitated by land and population centralization, ultimately advancing people-oriented urbanization objectives47.

Generally, there were significant differences between people-oriented urbanization and population and land urbanization, with most indicators of people-oriented urbanization lagging. This reflects the asynchrony of development in various dimensions in the urbanization process, revealing structural challenges, especially the disconnect between the supply of economic and social services and the population demand for land. People-oriented urbanization’s financial and social indicators lagged behind land and population urbanization. In contrast, the environmental indicators took the lead, and equity indicators conformed with land and population urbanization indicators. Local governments’ preference for land transfer as a revenue source accelerates land urbanization beyond economic and social development48. This approach potentially undermines concurrent industrial and social service development, delaying social indicator progression49. Conversely, the growing emphasis on sustainable development has elevated the importance of environmental protection as an urbanization priority, even making it a key performance indicator for government officials3,24,50. Environmental governance measures often precede land and population urbanization, thus enabling ecological indicators to maintain leadership positions. Additionally, China’s promotion of urban‒rural integration and reduction in urban‒rural differences have facilitated the alignment of equity indicators with land and population urbanization levels.

Coordinated development of multidimensional urbanization indicators requires further efforts. The analysis of China’s urbanization indicators revealed a temporal U-shaped trajectory in the evenness index, characterized by an initial decline followed by recovery, with an inflection point around 2012–2013. This trajectory can be attributed to concurrent policy and economic drivers. National policy initiatives, particularly the New-Type Urbanization Policy 2014, enhanced regional coordination by promoting interconnectivity among urbanization indicators. This policy framework departed from purely economically driven urbanization, emphasizing people-oriented development while balancing economic, social, environmental, and equity indicators14. Policy implementation yielded progressive benefits while manifesting improved indicator synchronization and mitigating previous challenges of resource inefficiency, ecological degradation, and social inequity during rapid urbanization2,51. Simultaneously, sustained economic growth facilitated increased investment in infrastructure, social services, and environmental preservation, strengthening the foundation for coordinated development among indicators52.

To assess the transformative impact of the 2014 National New-type Urbanization Plan on China’s urbanization model, we performed an interrupted time-series (ITS) analysis for 283 cities from 2005 to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The results indicated a statistically significant annual increase in the evenness index post policy implementation (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting accelerated improvement in urbanization quality after 2014. This finding is prominent when comparing pre-policy and post-policy growth rates of the evenness index, with the average growth rate shifting from −0.283 before 2014 to 0.553 after, indicating a fundamental reversal in urbanization trends (Supplementary Table 2). The robustness of these findings was confirmed through multiple tests, including the Chow (F = 16.69, p < 0.001) and CUSUM tests (p < 0.001), both of which supported a significant structural break in 2014 (Supplementary Table 3). These quasi-experimental tests suggest that the 2014 policy intervention effectively redirected China’s urbanization trajectory from a declining evenness to a steadily improving one.

Regional variations in coordinated development demonstrate strong correlations with resource endowments, development strategies, and geographical conditions. Small cities, non-urban agglomeration areas, and northeastern China exhibit enhanced coordination potential due to their lower population density and reduced land pressure53. Recent national policies supporting northeastern China and small-to-medium cities have further catalyzed their coordinated development54. Conversely, despite robust economic growth, urban agglomeration areas and large cities face developmental constraints, including population concentration, land resource scarcity, and environmental pressures, resulting in indicator imbalances and reduced coordination levels53. Intraurban variations persist, with South China demonstrating superior evenness attributed to its abundant natural resources and established industrial infrastructure, thus facilitating balanced progression across land, population, and people-oriented urbanization dimensions. The regional open policy framework has also provided favorable conditions for coordinated development.

Several suggestions emerge from our analysis. First, implementing differentiated regional coordination strategies is essential to address asynchronous development among urbanization indicators. Economic and social service systems currently lag behind land and population urbanization. For example, under SDG 11.1—universal access to adequate, safe, and affordable housing—land urbanization in China outpaces population growth, while social-service expansion remains insufficient. Although China’s urban home-ownership rate is about 87% (well above the global mean of ~65%), housing costs consume 30–40% of household income on average, exceeding the recommended ceiling of 30% and signaling persistent affordability challenges55. In regions with stronger coordination, targeted policies have mitigated these imbalances. Shenzhen’s multi-tiered affordable housing model aims for 26% coverage by 2035—surpassing the global average (~20%) but still below the Nordic benchmark (30–35%)56. By serving low- and middle-income households, the “sandwich class,” and skilled professionals, this framework provides a replicable approach aligned with SDG 11.1. Beyond housing, Shenzhen’s universal kindergarten program increased subsidies from CNY 40,000 per class per year to CNY 6,000 per child annually, boosting affordable kindergarten coverage to nearly 85% and demonstrating how cities can simultaneously address multiple dimensions of people-oriented urbanization57. Similarly, Liaoning Province’s 2019–2022 plan to integrate urban and rural compulsory education introduced a teacher-rotation system and expanded digital infrastructure, improving rural school quality and narrowing the urban‒rural education gap—another replicable model for balanced resource allocation in the context of new-type urbanization58. Accordingly, within the National Main Functional Area Planning framework, policy emphasis should shift toward strengthening economic development and social service infrastructure, prioritizing affordable housing provision as mandated by SDG 11.1. Research shows that local government’s reliance on land transfer revenues often results in delayed economic and social service development relative to land urbanization35,59,60. Therefore, reforming land revenue allocation mechanisms is necessary to secure adequate funding for affordable housing and other social infrastructure. Moreover, strategic macro-level planning must foster a more potent policy between industrial development and population agglomeration, moving beyond sole reliance on land expansion to achieve inclusive and sustainable urbanization outcomes that guarantee adequate housing and basic services for all residents.

Second, policy optimization requires regional differentiation to address structural imbalances in urbanization development. Concerning SDG 11.7—“providing safe, inclusive and accessible green public spaces”—our coordination analysis reveals a systematic lag of social service indicators behind population urbanization. While average per-capita urban park green space in China stands at 14.8 m2 (2021), with some provinces already surpassing 16–17 m², well above the UN-Habitat benchmark of 9 m², significant regional variations persist61. Regional variations in resource endowments, geographical conditions, and development strategies necessitate targeted policy frameworks. Low-population-density regions, particularly in Central, Western, and Northeastern China, require enhanced policy support to leverage their advantageous land availability and resource endowments for achieving balanced indicator development, including expanding green public spaces and community facilities. High-density metropolitan areas demand focused strategies for industrial restructuring, population distribution optimization, and environmental preservation to address resource constraints and ecological pressures. These areas are pioneering innovative approaches, such as the 15-min community-life circle concept, which has become a national urban development priority62,63. Major cities are pressing ahead: Shanghai has established more than 1600 such circles, while Beijing, Shenzhen, and others now treat the indicator as a key element of their urban-planning evaluation systems64. Furthermore, enhancing urban agglomeration and non-agglomeration area interconnections remains crucial. The South China model demonstrates the effectiveness of strategic resource utilization and industrial foundation optimization in promoting interregional coordinated development65. However, challenges remain in ensuring universal accessibility. While implementing the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Construction of Barrier-Free Environments has pushed coverage steadily upward, studies suggest that overall penetration across sectors still lags behind that of developed nations66. These examples underscore the need for differentiated regional strategies that address the quantitative expansion of public spaces and their qualitative improvement in accessibility and inclusivity.

Moreover, environmental governance should be maintained as the prioritization of urbanization strategy. Regarding SDG 11.6—reducing the negative environmental impact of cities—our data show that policies prioritizing environmental indicators have yielded notable results. The analysis demonstrated that environmental indicator prioritization substantially enhances urban sustainability. By 2023, all 297 prefecture-level and above cities in China had fully rolled out municipal solid-waste sorting, with an average residential-community coverage of 82.5%, while the 46 pilot key cities reached 86.6%, comparable to that of advanced European regions67. Urban PM2.5 annual mean concentrations have continued to improve; in flagship cities such as Beijing, they have fallen to about 30 μg m⁻³, still above the WHO’s latest guideline (5 μg m⁻³) but close to meeting the Chinese national standard (35 μg m⁻³)68. The urban wastewater treatment rate now is roughly 95%, near developed-country levels, though an urban‒rural gap remains69. These environmental-priority policies warrant continuation and intensification within the carbon-peaking and carbon-neutrality framework, encompassing the rigorous implementation of ecological protection measures, including strengthened carbon emission controls, land use regulations, and enhanced environmental compensation mechanisms70,71,72. Our proposed strategy of “environmental governance first” directly supports SDG 11.6. Environmental governance initiatives should precede land and population urbanization processes, utilizing environmental indicator advantages to catalyze coordinated development across other domains. Resource-intensive regions and metropolitan areas require policy frameworks that emphasize green industry development and the ecological transformation of existing industrial sectors, with particular emphasis on integrated urban‒rural environmental infrastructure to narrow the governance gap between cities and the countryside.

Finally, institutional innovation and policy coordination require further advancement. Concerning SDG 11.3—“enhancing inclusive and sustainable urbanization”—our study shows that, since 2013, the overall coordination of China’s urbanization has improved markedly, a trend closely tied to policy interventions. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Tan et al., Shen et al., and Siciliano (2012)73,74,75. According to the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the urbanization rate has reached 67.00%, up 0.84 percentage points from 2023, edging toward the State Council’s goal of “approaching 70% within five years” and placing China in the upper-middle tier globally. However, the urban‒rural income ratio still stands at 2.34:1 in 2024—a figure narrowing slowly but remains higher than in many developed economies, highlighting the need for more inclusive development approaches76. In recent years, public participation mechanisms in urban planning have steadily matured: most localities have introduced channels such as plan disclosure, public hearings, and stakeholder consultations, yet regional disparities in coverage persist, and no unified national statistical standard has been established77. This necessitates enhanced interagency collaboration and the establishment of systematic urbanization indicator evaluation mechanisms for continuous development evenness monitoring. Building upon the New-Type urbanization policy outcomes, refinement of cross-regional cooperation frameworks is essential for optimizing resource and production factor allocation. Developing multilevel governance platforms is crucial for increasing policy implementation oversight and evaluation, ensuring practical contributions to coordinated urbanization advancement. This strategy directly advances SDG 11.3 and resonates with successful models such as Liaoning Province’s integrated urban‒rural education system, which has built a multilayer collaborative governance framework spanning provincial to county levels and has facilitated a more balanced allocation of educational resources. Such platforms enable better coordination between different administrative levels and sectors, promoting more inclusive decision-making processes and ensuring that urbanization benefits are more equitably distributed across different population groups and regions.

The study revealed upward trajectories in people-oriented urbanization in China, with large cities, eastern regions, and urban agglomerations demonstrating comparative advantages. However, significant differences exist between people-oriented urbanization and population/land urbanization indicators. Throughout the study period, people-oriented urbanization—particularly economic and social indicators—lagged substantially behind the population and land urbanization parameters, whereas the environmental indicators maintained advanced positions. The evenness index among urbanization indicators displayed a U-shaped trend, pivoting in 2013. Small cities, northeastern China, and non-agglomeration zones exhibited superior coordination levels compared to large cities, eastern regions, and urban agglomerations. Advancing people-oriented urbanization necessitates implementing differentiated regional coordination strategies, structural policy optimization, environmental governance prioritization, and integrated policy coordination to promote multidimensional urbanization development.

Methods

Research area

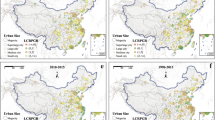

Our research area encompasses the entire mainland of China (Taiwan Province, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and the Macao Special Administrative Region are excluded due to data limitations), with prefecture-level cities serving as the basic research units (Fig. 8). In the research, cities with incomplete data were eliminated, resulting in a final sample of 283 prefecture-level cities nationwide. We classified the cities across multiple dimensions to comprehensively explore regional development plan variations. First, following the national plan (CPC Central Committee’s development proposals set long-range goals through 2035), the cities were categorized into four geographical regions: eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions. Based on the National New-Type Urbanization Plan, the cities were subdivided by population size: large cities (a population above 5 million people), medium cities (a population between 1 and 5 million people), and small cities (a population below 1 million people). Additionally, concerning Fang (2015) and the national-level urban agglomerations defined in the Report on Urban Development of China, the cities were further classified into urban agglomeration cities and non-urban agglomeration cities78.

a The distribution of major urban agglomerations across China. b The regional division used in this study: Eastern China, Central China, Western China, and Northeast China, along with city size categories (small, medium-sized, and large cities). Provincial boundaries, national borders, and major rivers provide geographic context.

Research framework

A systematic analytical framework was developed to evaluate multidimensional development characteristics and coordination of urbanization in China (Fig. 9). This framework consists of three main components: a quantitative indicator system, statistical methods, and coordinated development assessment. For the indicator system, the evaluation focuses on population urbanization, land urbanization, and people-oriented urbanization. The people-oriented urbanization dimension is divided into four aspects—economy, society, environment, and social equity—for 16 indicators. Statistical analysis encompasses three methodological approaches: paired t tests, 45° linear analysis, and multivariate fitting analysis, which are designed to assess dimensional differences, identify lagging or leading characteristics, and examine relational patterns, respectively. Moreover, an evenness index is used to evaluate quantitatively the coordinated development of urbanization via a modified radar chart method.

Three main components: indicators for measuring various dimensions of urbanization; the methods employed; and the conceptual framework for evenness measurement developed in this research (detailed descriptions are available in the “Methods” section). The abbreviation for each indicator is shown in Fig. 1.

Data preprocessing

To ensure the accuracy and consistency of the data analysis results, rigorous preprocessing, and quality control protocols were implemented. All spatial data were meticulously matched with prefecture-level city statistical data and analyzed at the prefecture-level city scale to guarantee spatial consistency. As an illustrative example, spatial overlay analysis of the PM2.5 concentration raster data and urban statistical data was conducted to verify the consistency and reliability of these datasets, thereby ensuring the validity and precision of the research outcomes.

Quantify the multiple dimensions of urbanization

In this study, the urbanization level in China and its dynamics across three primary dimensions were quantified (Table 1): population urbanization, land urbanization, and people-oriented urbanization. Drawing on Chen et al. and He et al.79,80, population urbanization is quantified via the proportion of permanent urban residents—an indicator capturing the rural-to-urban migration trajectory of the population79,80. The indicator value ranges from 0 to 100%, with higher percentages indicating more advanced urban population transformation. The definition of permanent urban residents follows the official criteria established by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, as outlined in the “Classification and Definition of Urban and Rural Population Statistics (2014).” This includes two criteria. First, an individual is considered part of the urban population if their usual place of residence on November 1 of the statistical year is located in urban areas of administrative divisions, such as municipal districts, county-level city government seats, or township-level street office areas, and they have resided there for at least 6 months in the past 12 months, irrespective of their household registration type. Second, administrative villages and township seats not meeting the urban construction land density threshold set by the Ministry of Housing and Urban‒rural Development are excluded from urban areas.

Drawing on Liu et al. and Zhang81,82, we measured land urbanization with the total urban built-up area. According to the Ministry of Housing and Urban‒rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, this area comprises all land designated for urban construction—residential neighborhoods, public facilities, industrial and logistics zones, transport infrastructure, green spaces, and water bodies—within the existing built-up zone and its planned expansion corridors. For two reasons, we intentionally avoided using ratio-based indicators, such as the urban built-up area as a proportion of city area or per capita built-up area. First, prefecture-level cities in China vary greatly in overall size, and the share of intrinsically undevelopable land (e.g., mountainous, desert), so land-area ratios may distort cross-city comparisons83. Second, indicators with a common denominator (e.g., urban land per capita and the proportion of permanent urban residents with a common denominator of total population) may create a mechanical correlation between indicators, masking the independent influence of land expansion on urbanization84. Therefore, this study used the total urban built-up area as the measure for land urbanization.

People-oriented urbanization was defined by four dimensions—economic, social, environmental, and equity—and was represented by 16 indicators that portray urbanization as a multidimensional socio-ecological process38. The method of indicator selection rigorously follows policy and authoritative documents, including the People-Oriented New-Type Urbanization Strategy, the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development, and National New-Type Urbanization Planning (2021–2035) (Supplementary Table 4). The economic indicators include the average deposit (AD), average wage of employees (AW), consumption expenditure per capita (CEP), fixed asset investment per capita (FAI), GDP per capita (GDPP), and house price-to-income ratio (HPIR). The first five are positive indicators representing wealth accumulation, economic security, consumption level, infrastructure investment capacity, and economic development. The HPIR serves as a negative indicator for assessing housing affordability. The social indicators include the education expenditure per capita (EEP), green space per capita (GSP), number of physicians per 1000 people (PP), R&D expenditure per capita (R&DEP), and unemployment rate (UPR). The initial four indicators are positive indicators reflecting educational service provision, leisure resource allocation, medical standards, and innovation capabilities, respectively. In contrast, the UPR functions as a negative indicator of economic resilience. The environmental indicators include the nonhazardous treatment rate of domestic waste (NHTR), PM2.5 concentration (PM2.5), and sulfur dioxide emissions from industry (SDE). The NHTR is a positive indicator of environmental management capabilities, whereas the PM2.5 concentration and sulfur dioxide emissions are negative indicators for evaluating air quality and pollution control levels, respectively. The social equity indicators include the Gini coefficient (Gini) and the urban‒rural income ratio (URIR). Both are negative indicators, with the Gini reflecting income distribution fairness and the URIR reflecting the degree of coordinated development between urban and rural areas.

Importantly, we did not aggregate the 16 people-oriented urbanization indicators into a single comprehensive indicator. This methodological decision stems from two primary considerations. First, the construction of comprehensive indicators typically involves a weighted summation of individual indicators, and the method of weight determination can significantly impact result reliability, potentially compromising the robustness of the research conclusions. Second, comprehensive indicators inherently possess black-box characteristics that mask the nuanced performance of specific dimensions, thereby limiting the ability to transparently examine and compare the relationships between urbanization development and population and land urbanization across different dimensions.

We employ the progress value and the base-period growth rate of a given indicator as analytical metrics to quantify and compare people-oriented urbanization levels across the different regions. Specifically, the progress value captures the distance between the actual regional urbanization level and the current optimal state, whereas the base-period growth rate reflects the urbanization change trend in each region in a dynamic time series relative to that in 2005. By applying these indicators, we can more comprehensively characterize the development level and evolutionary trajectory of each indicator within a given region.

Descriptive statistical analysis provides a fundamental approach for studying people-oriented urbanization. By calculating and comparing statistical measures such as the mean, median, and standard deviation among the different regions, the overall characteristics of various urbanization levels and their internal differences can be revealed. For example, the mean can reveal the overall level of urbanization in a specific region (China; eastern, central, and western regions; cities of different sizes; urban agglomerations and non-urban agglomerations). The median reflects the intermediate state of most urbanization levels in the region, whereas the standard deviation can be used to assess the degree of variations in urbanization levels in the region.

Analyze the differences between people-oriented and land–population urbanization

To quantify the differences among people-oriented, population urbanization, and land urbanization, paired ttests were employed. This statistical method aims to compare the mean differences between related sample groups and is particularly suitable for analyzing measurement outcomes for the same research subject under varying conditions85. The null hypothesis (H₀) posits that the difference between the means of the two measurement groups equals zero. The significance of the differences between indicators and urbanization types was determined by calculating the test statistic t-value and the corresponding p-value. A p-value below the significance level (α = 0.05) leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis, indicating a statistically significant difference between urbanization dimensions.

The second approach is the 45° linear analysis method, which is used to evaluate the lagging or leading status of different dimensions of people-oriented urbanization relative to population and land urbanization. Specifically, the progress value of population or land urbanization is set as the abscissa, the progress value of a certain indicator of people-oriented urbanization is set as the ordinate, a scatter plot is created, and a 45° reference line is added to the scatter plot. A point located on the 45° line indicates that the indicator is in sync with the development of population or land urbanization. Meanwhile, a point below the 45° line indicates that the development of this dimension is lagging behind, whereas a point above the 45° line indicates that its development is ahead of the curve. By observing the position of the data point distribution relative to the 45° line, the lagging or leading status of each region or dimension can be intuitively identified.

Multivariate fitting analysis was employed to examine the relationships between land urbanization, population urbanization, and various people-oriented urbanization indicators86. Given the complexity of socioeconomic phenomena, multiple fitting methods were implemented. Linear fitting aims to assess the correlation and significance level between variables, whereas quadratic and cubic term fitting can capture nonlinear characteristics. Additionally, logarithmic fitting and power function fitting can be used to analyze the asymmetric characteristics and proportional growth rate relationships, respectively. To validate the model fitting performance, we calculated the coefficient of determination (R2), adjusted coefficient of determination (adjusted R2), and mean square error (MSE), finally selecting the model that best explained the relationships between the variables. Furthermore, residual analysis was conducted to ensure the robustness and reliability of the results.

Quantify the evenness among people-oriented, land, and population urbanization

We applied an evenness index to measure the coordinated development of urbanization. The evenness index only targets progress values, and the change in the evenness of the progress values suggests a change in the evenness of the change rate. The evenness index is quantified using a modified radar chart method that provides a comparison of progress values across dimensions87.

The theoretical foundation of this approach rests on the isoperimetric principle, comparing the actual polygon area to the area of a circle with the same perimeter. When all radii of the polygon are equal, the polygon achieves maximum area efficiency for its given perimeter, indicating perfect balance across all dimensions. Conversely, divergence in radii reduces area efficiency, signaling an increasing imbalance among dimensions. The evenness index captures this balance by comparing the actual polygon area to the theoretical maximum area achievable by a circle with the same perimeter constraint. The method constructs an 18-sector radar chart (n = 18), where the radius of each sector represents the urbanization dimension value of a prefecture-level city. This evenness index aims to assess the coordinated development among urbanization indicators, with higher values indicating greater coordinated development. The evenness can be calculated as follows:

where Sj and Lj denote the sector area and perimeter, respectively, corresponding to a single urbanization dimension (such as indicators of people-oriented urbanization, land urbanization, and population urbanization), and Si and Li are the total area and total perimeter, respectively, of the radar chart formed by all urbanization dimensions. rj is the score of the jth urbanization dimension, rmax and rmin are the maximum and minimum scores of rj, respectively, in each dimension, and fj is the weight of the jth dimension. It is assumed that the weights of the various dimensions are equal, namely, fj = 1/n (where n = 18 dimensions). To assess the robustness of our evenness index, we conducted a comprehensive sensitivity analysis using eight different weighting methods. Beyond our baseline equal weights approach, we implemented seven alternative methods: PCA weights based on statistical variance contribution, entropy weights derived from information entropy theory, CRITIC weights incorporating correlation and standard deviation, CV weights, TOPSIS weights based on distance to ideal solutions, SD weights, and mean-based weights88. For each method, we calculated evenness indices across all cities and years, then evaluated the consistency of temporal patterns, regional disparities, and city-size hierarchies to determine which findings are robust across different weighting assumptions.

To ensure methodological consistency, we applied specific normalization rules for indicator directionality. For positive indicators, we applied standard min-max normalization. For negative indicators, we first performed a direction transformation by taking the opposite value or reciprocal, then standardized them to ensure that all rj∈[0,1] satisfy the consistency principle that “the higher the value, the higher the development level.” Supplementary Fig. 6 provides a complete workflow demonstration, tracing a representative prefecture-level city in 2015 through data normalization, sector area and perimeter calculation, aggregation, and final computation of the evenness index, thereby providing a transparent, reproducible template for implementation.

Evaluating the impact of the 2014 National New-type Urbanization Plan through interrupted time-series analysis

We conducted an ITS analysis to evaluate the impact of the 2014 National New-type Urbanization Plan on China’s urbanization evenness index89. We employed a quasi-experimental design using longitudinal data from 283 prefecture-level cities spanning 2005–2020, with the policy implementation in 2014 serving as the intervention point. The primary outcome variable was the urbanization evenness index, calculated annually for each city. Time was coded as a continuous variable, and a binary indicator (Post2014) denoted pre-intervention (2005–2013) and post-intervention (2014–2020) periods. We specified a segmented linear regression model to capture both immediate level changes and trend changes following the policy implementation:

where Yit represents the urbanization evenness index for city i in year t; the interaction term captures trend changes after 2014; ui is a city-level random intercept; and εit is the error term. The coefficient β2 estimates immediate level shifts, while β3 quantifies trend changes post-2014.

To validate our findings, we conducted multiple robustness checks. A Chow test assessed structural breaks at the end of 2013, while a CUSUM-of-squares test verified parameter stability90,91. Sensitivity analyses examined model robustness by varying control variables and comparing city-random effects with provincial fixed effects specifications. All analyses were implemented in R version 4.5 or higher using specialized econometric packages.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly accessible and categorized into four types: statistical yearbooks and official bulletins, remote sensing and spatial datasets, academic and open-access databases, and policy documents (Supplementary Table 5). Statistical data, including socioeconomic indicators at the prefecture-level city scale, were sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook, China City Statistical Yearbook, and prefecture-level city statistical bulletins available on official websites. Remote sensing and spatial datasets utilized include NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) dataset (https://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/srtm/), urban built-up area proportion data by He et al. (2016) (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/3100de5c-ac8d-4091-9bbf-6a02de100c88/), and China's high-resolution air pollution dataset (CHAP) for PM2.5 concentrations (https://zenodo.org/records/10800980). Macro-economic and social equity indicators were obtained from academic and open-access databases. Policy documents, including the National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), are publicly available through official government portals. The code generated and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

China Urban Statistical Yearbook 2024. China Statistics Press, Beijing (2024).

Chen, M., Liu, W., Lu, D., Chen, H. & Ye, C. Progress of China’s new-type urbanization construction since 2014: A preliminary assessment. Cities 78, 180–193 (2018).

Huang, Q. et al. Patterns and distributions of urban expansion in global watersheds. Earth’s. Fut. 9, e2021EF002062 (2021).

Luo, J. et al. Urban land expansion and the floating population in China: For production or for living?. Cities 74, 219–228 (2018).

Cattaneo, A. et al. Economic and social development along the urban–rural continuum: new opportunities to inform policy. World Dev. 157, 105941 (2022).

Qian, L., Lu, H., Gao, Q. & Lu, H. Household-owned farm machinery vs. outsourced machinery services: the impact of agricultural mechanization on the land leasing behavior of relatively large-scale farmers in China. Land Use Policy 115, 106008 (2022).

Yu, B. et al. Poverty evaluation using NPP-VIIRS nighttime light composite data at the county level in China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 8, 1217–1229 (2015).

Chen, M., Zhou, Y., Huang, X. & Ye, C. The integration of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization strategies in China: origin, reality and future trends. Land 10, 207 (2021).

Long, H. et al. Rural vitalization in China: a perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 29, 517–530 (2019).

Evans, P. (ed.) Livable Cities? Urban Struggles for Livelihood and Sustainability. University of California Press, Berkeley (2002).

Watson, V. The planned city sweeps the poor away’: urban planning and 21st-century urbanisation. Prog. Plann. 72, 151–193 (2009).

Chen, M., Ye, C., Lu, D., Sui, Y. & Guo, S. Cognition and construction of the theoretical connotations of new urbanization with Chinese characteristics. J. Geogr. Sci. 29, 1681–1698 (2019).

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. National New Urbanisation Plan (2014–2020). People’s Publishing House, Beijing (2014).

Chen, M., Gong, Y., Lu, D. & Ye, C. Build a people-oriented urbanization: China’s new-type urbanization dream and Anhui model. Land Use Policy 80, 1–9 (2019).

Bai, X. & Shi, P. China’s urbanization at a turning point—challenges and opportunities. Science 388, eadw3443 (2025).

Alberti, A. & Senese, M. Developing capacities for inclusive and innovative urban governance. In Governance for Urban Services: Access, Participation, Accountability, and Transparency (ed. Cheema, S.) 127–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2973-3_6 (Springer, Singapore, 2020).

Greed, C. Religion and sustainable urban planning: ‘if you can’t count it, or won’t count it, it doesn’t count. Sustain. Dev. 24, 154–162 (2016).

McGranahan, G., Schensul, D. & Singh, G. Inclusive urbanization: can the 2030 Agenda be delivered without it?. Environ. Urban. 28, 13–34 (2016).

Zhao, Z., Pan, Y., Zhu, J., Wu, J. & Zhu, R. The impact of urbanization on the delivery of public service–related SDGs in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 80, 103776 (2022).

Bosworth, G. et al. Identifying social innovations in European local rural development initiatives. Innovation 29, 442–461 (2016).

Scott, A. J. Beyond the creative city: cognitive–cultural capitalism and the new urbanism. Reg. Stud. 48, 565–578 (2014).

Clark, W. A. V., Yi, D. & Huang, Y. Subjective well-being in China’s changing society. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 16799–16804 (2019).

Long, H., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Woods, M. & Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 29, 11–22 (2012).

Wu, X. et al. Cropland non-agriculturalization caused by the expansion of built-up areas in China during 1990–2020. Land Use Policy 146, 107312 (2024).

Liu, T. China’s urban construction land development (Springer, Singapore, 2020).

Elmqvist, T. et al. Urbanization in and for the Anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain. 1, 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00018-w (2021).

Yang, Y., Bao, W., Wang, Y. & Liu, Y. Measurement of urban–rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 117, 102420 (2021).

Li, L., Fan, Z., Feng, W., Chen, Y. & Qin, K. Coupling coordination degree spatial analysis and driving factor between socio-economic and eco-environment in northern China. Ecol. Indic. 135, 108555 (2022).

Liu, N., Liu, C., Xia, Y. & Da, B. Examining the coordination between urbanization and eco-environment using coupling and spatial analyses: a case study in China. Ecol. Indic. 93, 1163–1175 (2018).

Xiao, Y., Zhong, J., Zhang, Q., Xiang, X. & Huang, H. Exploring the coupling coordination and key factors between urbanization and land-use efficiency in ecologically sensitive areas: a case study of the Loess Plateau, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 86, 104148 (2022).

Gao, B., Huang, Q., He, C., Sun, Z. & Zhang, D. How does sprawl differ across cities in China? A multi-scale investigation using nighttime light and census data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 148, 89–98 (2016).

Hou, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of urban sprawl in China from 2000 to 2020. GISci. Remote Sens. 61, 2351262 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. How does the coordinated development of population urbanization and land urbanization affect residents’ living standards? Empirical evidence from China. Cities 149, 104922 (2024).

Nederhand, J. et al. Reclaiming the city from an urban vitalism perspective: critically reflecting smart, inclusive, resilient and sustainable just city labels. Cities 137, 104257 (2023).

Krueger, E. H. et al. Governing sustainable transformations of urban social-ecological-technological systems. npj Urban Sustain. 2, 10 (2022).

Arvidsson, M., Lovsjö, N. & Keuschnigg, M. Urban scaling laws arise from within-city inequalities. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 365–374 (2023).

Bettencourt, L. M. A., Lobo, J., Helbing, D., Kühnert, C. & West, G. B. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7301–7306 (2007).

Elliott, J. R. & Clement, M. T. Urbanization and carbon emissions: a nationwide study of local countervailing effects in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 95, 795–816 (2014).

Zhou, C., Gong, M., Xu, Z. & Qu, S. Urban scaling patterns for sustainable development goals related to water, energy, infrastructure, and society in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 185, 106443 (2022).

Yang, C. & Zhao, S. Scaling of Chinese urban CO₂ emissions and multiple dimensions of city size. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159502 (2023).

Xu, G. et al. Underlying rules of evolutionary urban systems in Africa. Nat. Cities 2, 327–335 (2025).

Andersson, E. et al. What are the traits of a social-ecological system: towards a framework in support of urban sustainability. npj Urban Sustain. 1, 14 (2021).

Chen, B. et al. The evolution of social-ecological system interactions and their impact on the urban thermal environment. npj Urban Sustain. 4, 3 (2024).

Alberti, M. et al. The complexity of urban eco-evolutionary dynamics. BioScience 70, 772–793 (2020).

Kassiola, J. J. Coordinated rural-urban development in China: a new social spatial reorganization plan for urbanization, migration, and rural development. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 22, 77–95 (2017).

Sun, J. & Lyu, S. Does health insurance lead to improvement of health status among Chinese rural adults? Evidence from the China Family Panel Studies. Int. J. Health Serv. 50, 350–359 (2020).

Liu, Y., Lu, F., Xian, C. & Ouyang, Z. Urban development and resource endowments shape natural resource utilization efficiency in Chinese cities. J. Environ. Sci. 126, 806–816 (2023).

Lin, G. C. S. & Yi, F. Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geogr. 32, 50–79 (2011).

Rosenberg, M. & Everitt, J. Planning for aging populations: inside or outside the walls. Prog. Plan. 56, 119–168 (2001).

Lin, J., Long, C. & Yi, C. Has central environmental protection inspection improved air quality? Evidence from 291 Chinese cities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 90, 106621 (2021).

Egerer, M. et al. Urban change as an untapped opportunity for climate adaptation. npj Urban Sustainability 1, 22 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. The economic and environmental dividends of the digital development strategy: evidence from Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 440, 140398 (2023).

Fan, X. Research on the coupling of ecological environment and socio-economic development in resource-based cities: based on scenario simulation method. Sust. Cities Soc. 114, 105810 (2024).

Zhang, W., Zhang, Y. & Li, W. Impact of Northeast Revitalization policy on the industrial economy: empirical evidence from Central and Southern Liaoning urban agglomeration. Appl. Econ. 56, 6648–6666 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Housing prices and household consumption: a threshold effect model analysis in Central and Western China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 764 (2023).

Rui, J., Xu, Y. & Li, X. Destigmatising urban villages by examining their attractiveness: quantification evidence from Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 150, 103120 (2024).

Xie, S. & Li, H. Accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability and social justice of early childhood education in China: a case study of Shenzhen. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105359 (2020).

Zhao, N. Mechanism and empirical evidence on new-type urbanization to narrow the urban–rural income gap: Evidence from China’s provincial data. PLoS ONE 19, e0270964 (2024).

Kresse, K. & van der Krabben, E. Rapid urbanization, land pooling policies & the concentration of wealth. Land Use Policy 116, 106050 (2022).

Yu, H., Zhu, S., Li, J. V. & Wang, L. Dynamics of urban sprawl: deciphering the role of land prices and transportation costs in government-led urbanization. J. Urban Manag. 13, 736–754 (2024).

Pang, B., Zhao, J., Zhang, J. & Yang, L. Calculating optimal scale of urban green space in Xi’an, China. Ecol. Indic. 147, 110003 (2023).

Wu, H., Wang, L., Zhang, Z. & Gao, J. Analysis and optimization of 15-min community life circle based on supply and demand matching: a case study of Shanghai. PLoS ONE 16, e0256904 (2021).

Ma, W., Wang, N., Li, Y. & Sun, D. J. 15-min pedestrian distance life circle and sustainable community governance in Chinese metropolitan cities: a diagnosis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 112 (2023).

Han, J., Liang, H., Hara, K., Uwasu, M. & Dong, L. Quality of life in China’s largest city, Shanghai: a 20-year subjective and objective composite assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 173, 135–142 (2018).

Liu, J., Hou, X., Wang, Z. & Shen, Y. Study the effect of industrial structure optimization on urban land-use efficiency in China. Land Use Policy 105, 105390 (2021).

Brandt, L. & Thun, E. The fight for the middle: upgrading, competition, and industrial development in China. World Dev. 38, 1555–1574 (2010).

Lin, Y., Zhao, L., Yang, W., Hao, X. & Li, C. A review on research and development of passive building in China. J. Build. Eng. 42, 102509 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Hourly variation characteristics of PM2.5 and main components in Beijing based on wind direction. Atmos. Environ. 327, 120493 (2024).

Cen, X., Hu, Z., Huang, X., Yuan, Z. & Zheng, M. Integrated urban wastewater management through on-site generation and application of ferrous carbonate. Water Res. 268, 122732 (2025).

Jia, S., Weng, Q., Yoo, C., Xiao, H. & Zhong, Q. Building energy savings by green roofs and cool roofs in current and future climates. npj Urban Sustain. 4, 23 (2024).

Jiang, H. et al. An assessment of urbanization sustainability in China between 1990 and 2015 using land-use efficiency indicators. npj Urban Sustain. 1, 34 (2021).

Zhen, H. et al. Developing a conceptual model to quantify eco-compensation based on environmental and economic cost–benefit analysis for promoting ecologically intensified agriculture. Ecosyst. Serv. 56, 101442 (2022).

Tan, Y., Xu, H. & Zhang, X. Sustainable urbanization in China: a comprehensive literature review. Cities 55, 82–93 (2016).

Shen, L., Peng, Y., Zhang, X. & Wu, Y. An alternative model for evaluating sustainable urbanization. Cities 29, 32–39 (2012).

Siciliano, G. & Zhou, Z. Urbanization strategies, rural development and land-use changes in China: a multiple-level integrated assessment. Land Use Policy 29, 165–178 (2012).

Su, C., Liu, T., Chang, H. & Jiang, X. Is urbanization narrowing the urban–rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Habitat Int. 48, 79–86 (2015).

Cao, H. & Kang, C. I. A citizen participation model for co-creation of public value in a smart city. J. Urban Aff. 46, 905–924 (2024).

Fang, C. Important progress and future direction of studies on China’s urban agglomerations. J. Geogr. Sci. 25, 1003–1024 (2015).

He, C., Han, L. & Zhang, R. Q. More than 500 million Chinese urban residents (14% of the global urban population) are imperiled by fine particulate hazard. Environ. Pollut. 218, 558–562 (2016).

Chen, J., Davis, D. S., Wu, K. & Dai, H. Life satisfaction in urbanizing China: the effect of city size and pathways to urban residency. Cities 49, 88–97 (2015).

Liu, T., Liu, H. & Qi, Y. Construction land expansion and cultivated land protection in urbanizing China: insights from national land surveys, 1996–2006. Habitat Int. 46, 13–22 (2015).

Zhang, X. Q. The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat Int. 54, 241–252 (2016).

Chen, Z. & Yeh, A. G. Is prefecture-level city a ‘city’ in China: a critical review. Eurasia. Geogr. Econ. 66, 384–409 (2025).

Yang, S., Zha, Y. & Gao, J. Applications of remote sensing and GIS to monitoring of urban sprawl: a case study in Wuxi City, China. Ann. GIS 7, 137–141 (2001).

Hsu, H. & Lachenbruch, P. A. Paired t test. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online (ed. N. Balakrishnan) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat05929 (2014).

McArdle, B. H. & Anderson, M. J. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82, 290–297 (2001).

Du, J. et al. Global effects of progress towards sustainable development goals on subjective well-being. Nat. Sustain. 7, 360–367 (2024).

Mukherjee, S. P., Sinha, B. K. & Chattopadhyay, A. K. Statistical Methods in Social Science Research. Springer, Singapore, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2146-7 (2018).