Abstract

Urban resilience and vulnerability are often paired conceptually, but the dynamics of their relationships are rarely tested with space-time-based data. We tracked the 2019 European heatwave across Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague, combining hour-by-hour ambulance calls with district profiles identified from demographic, socioeconomic, health, and built environment attributes. We find significant differences in the factors driving vulnerability. The familiar rule of ‘more vulnerable, less resilient’ only partially holds: some vulnerable districts showed high resilience at particular times of the day, while seemingly less vulnerable districts showed low resilience. These swings point to the importance of local adaptive behaviours and urban social fabric in shaping dynamic vulnerability-resilience relationships. Our findings call for dynamic, district-specific planning: vulnerability assessments must look beyond averages, and resilience measures should flex with daily rhythms. Effective heatwave policy demands context-aware tools that treat resilience and vulnerability as intertwined, shifting properties of the urban social fabric.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2023, the world experienced its hottest summer, with July being the hottest month ever documented1. A year prior, Europe faced several heatwaves, resulting in 61,762 heat-related deaths2. The Netherlands, a country not traditionally used to extreme temperatures, has experienced six heatwaves since 2018. The 2019 European heatwave alone led to over 400 deaths3. Such extreme heat events exacerbate existing societal vulnerabilities and significantly challenge the adaptive capacities of both citizens and the urban systems designed to support them4,5. Research consistently links heatwaves to increased health emergencies, effects often amplified in cities by the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect6 and compounded by underlying structural inequalities7.

Two central concepts underpin our study: urban vulnerability and resilience. Urban vulnerability is the degree to which an urban system is susceptible to and unable to cope with the adverse effects of stressors such as heatwaves8. Vulnerability typically encompasses three components: sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity9. In contrast, urban resilience refers to the ability of the urban system to recover, adapt, or transform in response to shocks, thus maintaining functionality under stress and disruptions10.

Current approaches for assessing heat vulnerability often emphasise spatial analysis, mapping areas based on static characteristics11,12,13. However, these approaches face criticism for potentially neglecting the dynamic aspects of vulnerability, particularly how people’s exposure and their ability to cope (adaptive capacity) change over time during an event14. Furthermore, existing theoretical frameworks on urban vulnerability and resilience15,16,17 often lack corresponding empirical, data-driven validation that captures the complexities of urban life across both space and time18,19. The frequent lack of high-resolution spatio-temporal data also tends to limit assessments to broader geographical scales, potentially obscuring critical variations in heatwave impacts within cities, which arise from the diverse social, economic, and physical characteristics of different districts and populations20,21.

This study addresses these gaps by introducing an analytical framework to investigate the spatio-temporal dynamics of urban vulnerability and resilience, specifically during heatwave events. While recognising the importance of long-term heat adaptation, our focus here is on the critical response phase, examining urban systems’ short-term adaptivity and responsiveness to the immediate impacts of heat stress22. We operationalise resilience dynamically by analysing patterns of ambulance calls made during a heatwave. As demonstrated in previous studies, such data serve as a useful proxy for the acute health impacts and the citizens’ immediate response capacity under heat stress6,23,24. This dynamic resilience proxy is examined alongside spatial patterns of vulnerability identified through Non-Negative Matrix Factorisation (NMF), applied to citizens’ characteristics and the urban environment in which they live at the district level. NMF identifies dominant combinations of features and their relative contribution, which form a ‘profile’ (e.g. a profile high in ‘elderly and low-income’ or one high in ‘single-parent living in an urban heat island’). We then classify these profiles in line with the literature on heat vulnerability. In this framework, adaptive capacity acts as a bridge: it is implicitly assessed as a component of vulnerability through socio-economic and health factors indicating coping potential, and its real-time manifestation is reflected in the resilience measure via fluctuations in ambulance calls25.

We use the 2019 European heatwave as a case study—a significant event that profoundly tested urban infrastructure and health systems across the continent26. Our analysis focuses on the three largest cities in the Netherlands: The Hague, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam. By analysing open data on excess ambulance calls (resilience proxy) and employing NMF to identify patterns of heat vulnerability across city districts, we seek to answer two key research questions: (1) How do temporal patterns of resilience, measured with ambulance calls, vary across different urban social fabric under the heatwave? (2) What spatial patterns of vulnerability emerge within these cities, and how do these patterns appear to influence the observed resilience dynamics during the heatwave? By empirically linking conventional metrics for vulnerability (district vulnerability profiles) and the proposed resilience proxy (spatio-temporal ambulance calls), this research aims to contribute valuable insights into the complex interplay between these concepts, ultimately informing more effective urban sustainability and climate adaptation strategies.

Results

Here, we present the key findings emerging from our comparative studies on urban vulnerability and resilience during heatwaves. Our analysis examines these phenomena at the district level, although we acknowledge that the fundamental mechanisms shaping vulnerability and resilience ultimately operate through individuals. Consequently, while the indicators used to measure vulnerability (age, income or pre-existing health conditions) and resilience (change in ambulance call patterns) are defined for individuals, our analysis aggregates this information to the district scale. This approach allows us to construct district vulnerability profiles based on the concentration of heat-susceptible socio-demographic groups, while acknowledging that individual adaptive behaviours are key to understanding vulnerability within these profiles and are the primary drivers of resilience patterns. From these observations, we distil our key findings into a set of concise, testable propositions. These are deliberately framed for transferability, serving as an invitation for refinement, adaptation, and wider discussion across diverse contexts regarding the relationship between urban vulnerability and resilience in the face of heatwaves. We will revisit each proposition in the Discussion Section to position it within the broader academic literature.

Temporal patterns of heat resilience

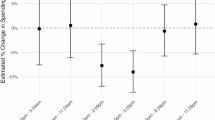

We start by analysing the temporal variability of health impact at the city scale (Fig. 1). During the heatwave week (22–28 July 2019), the number of ambulance calls across all three cities: The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam- experienced a significant increase, rising by 20% above the 2019 summer weekly average over the heatwave period. The hottest day on record was particularly striking. On July 25, 2019, temperatures spiked beyond 40 °C. The temperature rise correlated with a significant increase in ambulance calls: 41% in The Hague, 31% in Rotterdam, and 27% in Amsterdam, compared to an average summer day of 2019.

The three panels represent data for different cities: a The Hague, b Rotterdam, and c Amsterdam. Each graph shows the percentage difference in the number of calls (black line) compared to the average number of calls over a typical week. The graphs contain real data points as well as a cubic spline fit. The background gradient indicates the median temperature in Celsius, transitioning from cooler temperatures (blue) to warmer temperatures (red). The period of the day is segmented into 4-h intervals.

Even though the increase in ambulance calls confirms the important health impacts of heatwaves, there is a significant variation in the underlying temporal patterns across cities. Across all cities, the highest average increase observed was 24% in The Hague during the noon interval (12:00–16:00), closely followed by increases during the night (00:00–04:00), and evening periods, with percentages ranging from 21 to 23%. Rotterdam mirrored this pattern, with its peak average increases at noon and evening times (20:00–00:00). Amsterdam differed, showing its highest average increase of 30% in the early evening, with relatively consistent increases throughout the day and a notable absence of an increase at night.

These distinct hourly patterns across cities during the same heatwave event underscore a critical point: urban environments are inherently dynamic systems22. Although vulnerability to heatwaves is often mapped and understood as a static, spatial phenomenon, identifying fixed ’hotspots’ based on location27, our findings demonstrate that resilience fluctuates significantly over time. This temporal dimension is crucial because exposure to heat is not constant; it changes based on where people are and what they are doing throughout the day and night28.

To better grasp this dynamic, we consider the interplay between the ‘urban fabric’, the physical city composed of buildings, streets, infrastructure, and green/blue spaces29, and the ‘social fabric’. While the social fabric is sometimes defined purely as social interactions, we emphasise that these interactions are fundamentally embedded within physical space. Therefore, we adopt the concept of the ’urban social fabric’: the social elements and activities that both shape and are shaped by the physical urban environment30,31.

For our analysis, we operationalise this concept as the interplay of citizens’ demographic (e.g. age), socioeconomic (e.g. income), and health (e.g. illness) characteristics. These characteristics, interacting with the physical urban environment (including exposure to factors like the Urban Heat Island effect), collectively shape daily activity rhythms (such as work and leisure) and contribute to social inequalities. This entire fabric, which establishes a district’s baseline vulnerability, in turn determines the adaptive behaviours citizens exhibit during heatwaves.

Critically, many studies aiming to measure the vulnerability of urban populations focus primarily on static social factors like income level or education32. Such approaches often overlook the dynamic changes in how people occupy and interact with different parts of the city at different times, precisely the kind of temporal variations our data reveals. Given the divergent patterns observed, we therefore posit the following:

Proposition 1

Temporal dynamics of city-specific urban social fabric—and corresponding vulnerabilities—lead to different temporal patterns of heatwave resilience.

As expected, there is a positive correlation between higher temperature and an increased number of ambulance calls with ρ = 0.3 for The Hague and ρ = 0.25 for Amsterdam. The relationship in Rotterdam with ρ = 0.06 appears more complex, indicating a delay in response between temperature increase and the rise in calls. During the hottest day, Thursday, 25 July, both The Hague and Rotterdam experienced a significant spike in calls, up to 100% more than on a regular non-heatwave summer day, during the 12:00–16:00 and 16:00–20:00 intervals. In contrast, Amsterdam saw a smaller increase of 58% during the same time frame. Yet, Amsterdam’s call volume peaked at 106% more than usual two days later, on Saturday, 27 July, between 08:00 and 12:00.

Previous research already pointed to potential delays in the response to heatwaves24,33. Yet, the heat resilience literature often assumes that the impact of a heat shock is instantaneous, leading to an immediate impact or loss of performance34. The literature also stresses the importance of coping capacity, or the ability of communities and individuals to manage adversity35,36. Often, coping capacity for heatwaves includes factors such as ventilation protocols, awareness campaigns, or advice to drink sufficiently, which are also essential elements of the Dutch National Heat Plan37. What is often overlooked, however, is how coping capacity may deplete over time. Our findings suggest that even as exposure decreases (e.g. temperatures drop at night), the accumulated strain on physiological and social coping mechanisms can lead to delayed decline of resilience, with health impacts manifesting hours or even days after peak heat exposure. This temporal dimension of coping capacity challenges static vulnerability assessments that assume constant relationships between exposure and health impacts. This leads us to the following proposition:

Proposition 2

Coping capacity temporarily plays a role as a ‘buffer’ against heat exposure, but its erosion over time leads to declining resilience even when temperatures decrease.

Spatial patterns of heat vulnerability

To understand the spatial patterns of heat vulnerability, we apply NMF to the district features of each city separately. Figure 2 visualises the resulting component matrices. Panelss (a–c) represent The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. The case cities can be viewed as a combination of at least four vulnerability profiles, each with a unique share of features that define their ’levels’ of vulnerability. For all three cities, profile 0 has the highest contribution of features that could potentially increase heatwave vulnerability. Yet, what drives vulnerability is different across the three cities.

(a–c) correspond to each city, respectively. The heatmaps visualise the contribution of various vulnerability indicators to four distinct vulnerability profiles identified by NMF. The colour gradient transitions from blue to yellow to signify the increasing magnitude of contribution, thereby illustrating the differential impact of each feature on the vulnerability profiles within the urban districts. The abbreviation ‘HH’ stands for the household, ‘sv. lim.’ for severely limited and ‘srs.’ for seriously.

The districts of profile 0 in The Hague show the highest contribution of children 0–14 years old, single-person households and households with children (including single parents) and people with lower education and income. Demographic, socio-economic, as well as health-related features indicate lower adaptive capacity of families with young children in the city. From the exposure side, profile 0 districts have a significantly higher presence of the UHI effect. Remarkably, people 65+ years old, commonly referred to as vulnerable to heatwaves, do not prominently feature here. Rotterdam’s districts of profile 0 have a similar structure despite a higher share of 65+ people, while low and medium education features have a similar presence in the profile. Health-related features are becoming less pronounced in Rotterdam’s profile 0. In contrast, Amsterdam’s profile 0 contains mostly people in the 45–64 and 65+ age groups, without children, predominantly of low education and income. We also see high values for severely limited due to health and mobility issues. In addition, we see the highest contribution of exposure (UHI) across all profiles.

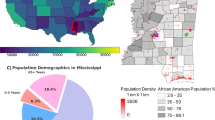

Geographically (Fig. 3, in The Hague, we observe the highest concentration of the most vulnerable districts (Profile 0) in the southeast and the city centre, leading to high segregation and clear-cut differences in this vulnerability profile. For Rotterdam, profile 0 dominates in the south and also several districts in the city centre, indicating that vulnerability is more dispersed through most of the city, besides the outskirts in the west and north. Amsterdam is characterised by a few pockets of vulnerability scattered across the city.

Choropleth maps show the spatial distribution of Vulnerability Profile 0 (derived from the NMF basis matrix W) across districts in (a) The Hague, (b) Rotterdam, and (c) Amsterdam. Districts are grouped into three ordered classes (low, medium, high) based on the relative intensity of Profile 0 within each city; class break ranges are reported in the inset legend of each panel. Colours indicate increasing Profile 0 intensity from dark purple (low) to teal (medium) to yellow (high).

A recent review on the heatwave vulnerability in the Netherlands has found mixed evidence, stating that elderly, socially deprived or poor households may be the most vulnerable to heatwaves38. Similarly, high population density has been associated with higher heat exposure9. Our findings draw a more nuanced picture, highlighting the interplay between various features of the urban social fabric and what makes a city and its districts vulnerable. This is true even though our three case cities may seem very similar at first glance, as they are all located in the same social-political-environmental context. While in the literature, contextualisation has been discussed in the context of global vulnerability and resilience assessment39, which is typically based on a single indicator, our findings show that urban vulnerability to heat is localised and dependent on the complex urban social fabric. This leads us to:

Proposition 3

Vulnerability metrics must be contextualised to the local urban social fabric, even if the cities are located in the same country and region.

This finding stresses the importance of location and implies that vulnerability and resilience metrics need to be contextualised locally. No single factor or variable, nor a standard set of variables, can adequately measure urban heat vulnerability40.

On the interplay of vulnerability and resilience

Overall, we found a strong correlation between the number of ambulance calls and the identified vulnerability profiles, indicating a strong relationship between resilience and vulnerability features. Following the literature, vulnerability of districts is conceptualised in this study as a spatial attribute9,38. District vulnerability does not change during the timeframe of a heatwave, i.e. the number and location of the most vulnerable districts remain constant. Resilience, in contrast, is a dynamic concept.

Table 1 presents the Spearman’s rank correlation between the identified vulnerability profiles and three key indicators: the total number of calls made during an average summer week, the total number of calls made during a heatwave week, and the difference in the number of ambulance calls during a heatwave compared to the average weekly calls in summer (referred to as resilience). Across all three cities and the indicators of interest, the Spearman’s rank correlations range from −0.28 to 0.5. This range suggests that certain attributes can significantly influence the number of ambulance calls.

The Hague presents a distinct picture, with profile 0 districts showing a strong positive correlation for all three indicators, underscoring the high vulnerability of the profile. Profiles 1 and 2 reveal negative or no correlations, although to varying degrees, indicating a potential for resilience or lower vulnerability. Remarkably, profile 3 districts have strong negative correlations across all three indicators. The last suggests a significant decrease in ambulance calls during heatwaves. This implies that the heatwaves in The Hague further amplify existing vulnerability profiles, shifting calls even more to the most vulnerable (and away from the least vulnerable) districts.

In Rotterdam, profile 0 again shows a strong positive correlation, but only for the average and heatwave week calls. Correlation coefficients for the difference are slightly lower. Profile 1 areas display a unique pattern, with a slight positive correlation during the heatwave, suggesting varying impacts or responses compared to other profiles. This indicates that in Rotterdam, profile 1 (characterised by households with children) is vulnerable and that heat vulnerability in Rotterdam is a broader phenomenon than in the other cities. Profile 3 in Rotterdam shows negative correlations, indicating potentially effective responses to heatwaves, confirming the findings for The Hague.

Amsterdam’s analysis also confirms that profile 0 areas show a strong positive correlation across the board, highlighting a lack of resilience. Interestingly, profile 1 (high-income, highly educated households) demonstrates a shift towards negative correlations, suggesting that areas under this profile might exhibit resilience that allows them to flip their profile during heatwaves. Profile 2 areas, conversely, show a mixed response with a slight increase in call frequencies during heatwaves, whereas profile 3 maintains a neutral stance with minimal fluctuations in call volumes.

Previous research on heatwaves already indicated that the exposure to heat globally exacerbates inequality4,41. These studies, as well as national heat plans42, often focus especially on elderly populations. Our findings reveal a broader and more nuanced picture of vulnerability, especially profiles of districts with highly educated and high-income residents showing high levels of resilience, reversing the expected vulnerability pattern, and shifting ambulance calls disproportionately to the most vulnerable districts. This effectively leads to a spatial redistribution of health burdens towards the most vulnerable districts. This demonstrates how the heatwave acts upon the pre-existing urban social fabric, amplifying the socio-spatial inequalities43 embedded within it. This leads us to:

Proposition 4

Heatwaves amplify existing vulnerabilities and social inequalities between different urban districts.

This finding is consistent with the disaster vulnerability literature, demonstrating that crises exacerbate existing inequalities. Similar patterns have been observed in other contexts, such as the COVID-19 pandemic44 and floods45,46, where socially disadvantaged groups experienced disproportionately larger outcomes.

Temporal patterns in the resilience-vulnerability interaction

Temperature, as well as citizen behaviour, changes over time. Therefore, we investigate the temporal patterns in the interaction of urban vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves.

Figure 4 visualises the relationships between vulnerability and resilience by time of day. The x-axis represents vulnerability, the y-axis represents resilience, and every point is a district (see Analytical framework for a complete description). The box text reports Spearman’s correlation coefficient for each period. The bivariate colour scheme navigates the relations, with red in the bottom right corner for the most vulnerable and blue in the upper left corner for the most resilient. Thus, if a district (point) is in the upper part of the scatterplot, this district is resilient. Conversely, if a district is in the far right part of the plot, it is vulnerable. Note that while resilience varies across times of the day, vulnerability is static. Thus, every point (district) will always have the same position on the x-axis; only its position on the y-axis will change.

Each column represents a city, while each row corresponds to a specific time period. Spearman’s correlation coefficients indicate the strength and direction of the relationships, revealing temporal variations in vulnerability and resilience. The bivariate colour scheme in the background highlights the type of relationship between vulnerability and resilience, with a gradient ranging from blue (low vulnerability and high resilience) to red (high vulnerability and low resilience), visually emphasising areas with different combinations of vulnerability and resilience.

Conventional wisdom suggests that higher vulnerability is associated with lower resilience. Therefore, we expect to see a negative correlation between these two. Positive correlations suggest the opposite: higher vulnerability is associated with higher resilience. Interestingly, correlations ‘flip’ across all cities, suggesting that the relationship between heatwave vulnerability and resilience changes over time.

Our analysis shows that - despite lower temperatures with respect to the daily maximum - the most difficult periods are night and early morning for all cities, with the highest number of districts demonstrating low resilience. As indicated by Proposition 2, this can be explained by an erosion of coping capacity over time, where behavioural adaptations such as visiting green spaces, going to a mall or a cinema may not be available or accessible at night, or for a sequence of days. In addition, even though temperatures generally drop, the heat accumulated during the day may persist at night in certain districts or buildings, meaning that residents and infrastructure do not have enough time to cool down and recover47.

When comparing cities, The Hague had the highest number of districts demonstrating low resilience (27) during the 2019 European heatwave. Rotterdam and Amsterdam share the same number of 13.

The Hague’s correlations range from −0.37 to +0.25 across different times of the day. Notably, the strongest negative correlation of −0.37 occurs in the 20:00–00:00 time frame, suggesting that in The Hague, districts with higher vulnerability see relatively few ambulance calls during heatwaves at night and in the early morning (until 8:00). Surprisingly, during the day, the correlation is positive with the highest values in the late afternoon, suggesting that during the hottest hours, higher vulnerability is associated with higher resilience and fewer calls. This finding suggests high coping capacity during the day despite a significant urban heat island effect for the 0 profile.

The correlations for Rotterdam show a similar pattern, yet with less pronounced values (between −0.12 and + 0.13). We find the strongest negative correlation of −0.12 during the night hours (00:00–04:00). This finding suggests that Rotterdam districts, while having ‘more’ vulnerability attributes, experienced smaller differences in ambulance calls than The Hague’s districts.

Amsterdam also demonstrates significant variations in correlations throughout the day, from −0.16 to 0.19. The temporal pattern, however, is different from the patterns in the other two cities. Importantly, we find negative correlations during the hottest periods of the day (12:00–20:00). In other words, in Amsterdam, hotter temperatures lead to a loss of resilience in highly vulnerable districts. The correlation turns positive in the evening (20:00–0:00) when the city starts cooling again.

This shift of the temporal pattern points us to the hidden dynamics driving vulnerability. While in Amsterdam, profile 0 is characterised by people with limited mobility in the 65+ age group, in Rotterdam and The Hague, relatively young people and families with children form the most vulnerable profile. Our temporal analysis shows that these groups may be able to adapt during the hottest hours, possibly by moving to cooler parts of the city. Yet at night, when they might return to their homes and districts, high vulnerability leads to more ambulance calls, even though the temperatures go down. These findings show a clear and distinct change in vulnerability-resilience relationships, leading us to:

Proposition 5

Adaptive behaviour transforms urban dynamics and leads to changes in vulnerability and resilience relationships in urban districts over time.

While much work on heat vulnerability focuses on exposure41 or emphasises long-term social vulnerability factors48, our findings suggest that short-term adaptive behaviour—the actual actions people take during a heatwave—plays a crucial role in transforming vulnerability-resilience relationships in urban districts over time. This finding is in line with an emerging body of literature that highlights how extreme heat impacts daily urban living49. To effectively assess resilience and vulnerability, it is therefore essential to use dynamic measurements and analysis tools that recognise adaptive behaviour and coping capacity (Proposition 2) rather than relying on static spatial metrics based on geographical boundaries. Additionally, understanding the fundamental factors of urban social fabric, contributing to people’s ability to adapt in different cities, is crucial for explaining the arising dissimilarities.

Spatial-temporal patterns in the resilience-vulnerability interaction

To better understand the relationship between vulnerability and resilience in space and over time, we examine the individual grid cells (nine in total) and the districts that belong to them (Fig. 5). Specifically, we are interested in understanding the emergence of the following phenomena: High vulnerability (>0.66), high resilience (>0.66) (high-high grid cell 3C in Fig. 5); High vulnerability (>0.66), low resilience (<0.33) (high-low grid cell 3A in Fig. 5); Low vulnerability (<0.33), low resilience (<0.33) (low-low grid cell 1A in Fig. 5).

By investigating the 3C high-high grid cell using Fig. 6, we can understand how many highly vulnerable districts are also highly resilient, indicating cases of effective adaptation. On average, across all time periods, the high-high grid cell contains 5 out of 40 (12.5%) of The Hague’s districts, 18 out of 76 (23.5%) of Rotterdam’s and 7 out of 97 (7.6%) of Amsterdam’s districts. Note that not all of these districts are highly vulnerable. If we calculate the fraction of the number of districts in the 3C grid cell to the number of vulnerable districts, we obtain the following results: 71.4% for The Hague, 89.7% for Rotterdam, and 91.7% for Amsterdam. Thus, the number of highly vulnerable districts that are also resilient is the highest for Amsterdam and the lowest for The Hague.

Bivariate choropleth maps showing the spatial relationships between urban vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves over different periods in the districts of The Hague (a), Rotterdam (b), and Amsterdam (c). Each map highlights how varying levels of vulnerability and resilience intersect, providing insights into how different districts cope with heat shock across time, with colour gradients representing the intensity of these interactions.

Thus, while a district has a constant high vulnerability, it may lose its resilience, which was in place during the day and become fragile at night. That is, for The Hague, the number of vulnerable districts that are also resilient becomes the lowest during the late evening (20:00– 0:00) with 28.6% and early morning (04:00–08:00) with 57.5%. A similar pattern applies to Rotterdam; the number drops to 80% and 75% at night (0:00–04:00) and in the early morning. Amsterdam demonstrates more complex behaviour, with the highest number of vulnerable districts being resilient at night and late evening, which decreases to 87.5% during the rest of the day.

The 3A high-low grid cell captures a more conventional idea that being highly vulnerable could imply being less resilient. The high-low districts are the most critical, as these areas demonstrate a lack of adaptation and coping, while being highly vulnerable. As we previously have seen, the majority of highly vulnerable districts demonstrate high resilience; however, some of them lose their resilience at specific times during the day. On average, across all time periods, The Hague has five unique districts with high vulnerability and low resilience, Rotterdam has two, and Amsterdam has one. Importantly, Rotterdam has more districts (a total of 9) that demonstrate medium resilience (grid cell 3B). Overall, The Hague has the highest number of highly vulnerable districts with low resilience.

Remarkably, districts with high vulnerability show low resilience only during specific periods of the day: at night when the accumulated heat strikes particularly vulnerable populations or areas with a lot of human activity and traffic. For The Hague at 04:00–08:00, these are the Schildersbuurt and Leyenburg residential districts with high concentrations of vulnerable individuals. Or, again, in The Hague, from 12:00 - to 16:00, it is the Groente- en Fruitmarkt district, which has vulnerable individuals and is neighbouring the largest market of the city.

The 1A low-low grid cell contradicts conventional wisdom - why would districts with low vulnerability demonstrate low resilience? Districts of this category are of particular interest since they have a higher chance of being overlooked: they lack the conventional vulnerability features but also demonstrated low resilience via an increase in the number of ambulance calls during the heatwave. Looking at the bigger picture, all three cities have many districts in this category across all periods: 9 for The Hague, 6 for Rotterdam and 4 for Amsterdam. While the urban social fabric of these districts is quite diverse, they form at least three categories: beaches, coastal areas and parks, proximity to highways, and industrial areas.

Beaches and coastal areas are popular during hot summer, especially in The Hague (Scheveningen, Kijkduin en Ockenburgh). Similar considerations apply to the ‘green and blue districts’ (Zorgvliet in The Hague, Blijdorpsepolder in Rotterdam, and Houthavens, Willemshaven in Amsterdam). What makes these districts less resilient may, therefore, be their attractiveness to people from more vulnerable districts, especially during the hottest hours of the day. While green and blue spaces have been widely advocated to combat the urban heat island effect46, they paradoxically become ’hotspots’ in our study. The lack of resilience in these districts compensates for the relatively high resilience of highly vulnerable districts during the day. This leads to:

Proposition 6

Driven by citizen adaptive behaviour, districts with green and blue areas become the hotspots of low resilience during a heatwave.

This finding also corroborates our hypothesis on the crucial role of adaptive behaviour, whereby people move to cooler areas during the day. Thus, having blue and green infrastructure ‘somewhere’ in the city might not benefit vulnerable individuals living in a UHI. It provides them with benefits by reducing their exposure, but only during a chunk of the day. There is a need to ’spread out’ and extend these infrastructures to the areas that need them the most.

Other districts that show low resilience are those near highways (e.g., Hoornwijk in The Hague). Increased traffic of people entering or leaving the city, especially on busy beach days, increases the risk. In addition, industrial districts show low resilience (Nieuw Mathenesse in Rotterdam). Here, the presence of industrial sites and the lack of established community services and social networks may lead to lower resilience during the day, particularly since workers may not be restricted in their adaptive behaviour and cannot move to cool areas during working hours.

Discussion

Our exploration of the spatial-temporal dynamics of vulnerability and resilience extends existing frameworks in urban climate adaptation and resilience in several ways: Previous studies have often treated vulnerability to heat as a static, spatial phenomenon11,12,13, or vulnerability and resilience have been understood as disconnected attributes19,50. Our empirical findings demonstrate their dynamic interrelationship at the district level through six propositions. Three propositions listed in Table 2 (P2, P4, P6) highlight how heatwaves interact with urban systems, challenging the conventional understanding of the relationship between exposure to heat and resilience impact. The other three propositions from Table 3 (P1, P3, P5) seek to contribute to methodologically advancing our understanding of vulnerability and resilience by emphasising the role of spatio-temporal dynamics. We also stress that short-term citizen adaptive behaviour is crucial in connecting vulnerability and resilience concepts at the urban district level, requiring a bridge between micro-macro urban scales. Together, these propositions are intended to offer starting points for further empirical investigation and the discussion on the relationship between urban vulnerability and resilience.

Our findings indicate that resilience and vulnerability to heatwaves are phenomena that are deeply embedded in time and space and shaped by the underlying urban social fabric.

For the temporal dimension (P2), we observe that the number of calls can be somewhat decoupled from the greatest exposure to heat. The Hague experienced the highest increases in ambulance calls during peak temperature periods, suggesting that its urban social fabric is more vulnerable to immediate heat shock. In contrast, Rotterdam’s delayed response indicates a more complex interplay between temperature and health impacts, possibly due to better initial coping mechanisms or delayed recognition of heat-related issues33. Amsterdam’s unique pattern of delayed peak ambulance calls further underscores the importance of considering local behaviours and urban characteristics in resilience planning. In part, this may be related to people’s capacity to handle the heat, which depletes over time or is caused by the gradual heating up of the built environment. Additionally, mobility could play a significant role. While avoiding unfavourable conditions during the day may be possible, vulnerable populations, such as low-income individuals, must return home at night51. Picking up kids for lunch and when the school is out might put a strain on single-parent households, providing fewer opportunities to leave districts of residence in a UHI. This suggests that adaptive capacity for heatwaves includes a temporal dimension, challenging the conventional view of addressing it as a static component related to, e.g., abilities like ventilating buildings or using shades35.

Our findings on the impact of heatwaves on urban social fabric (P4) support the broader disaster literature, demonstrating that crises disproportionately impact the most socially disadvantaged groups. This trend is evident in the context of this study on heatwaves, where districts with lower income, lower education, and health issues experienced the most significant increases in ambulance calls52. Comparably, our findings on the unequal spatial impact directly align with core concerns within critical heat studies and the broader environmental justice literature53,54. This emerging body of scholarship emphasises that the experience of heat and the ability to cope with it are not uniform but are deeply embedded in the underlying social, political, and historical contexts. Our observation of significant differences in the underlying factors determining vulnerability, even between seemingly similar cities, underscores the need for a more contextualised understanding of heat vulnerability. Similar patterns have been observed in other crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic44 or natural disasters such as floods45,46. Consequently, we reaffirm the need to address the distributional and equity impacts of heatwaves and other disasters, drawing on findings from previous research. This highlights the importance of enhancing resilience and preparedness55.

In terms of space (P6), we found that green and blue areas, typically considered as mitigators of urban heat5,46, can become hotspots of low resilience during heatwaves (Fig. 7). Districts with beaches, parks, and other recreational areas showed increased ambulance calls, likely due to the influx of people seeking relief from the heat, including tourists, who might be less aware or lack the capacity to tackle a week-long heatwave. This pattern was especially prominent in The Hague’s coastal districts and Amsterdam’s green spaces. This implies that the response to heatwaves must also consider that places less exposed to heat will become attractors for vulnerable populations and temporarily have to handle an increase in demand. This movement is a direct manifestation of adaptive behaviour modifying ’baseline’ daily rhythms14. Individuals, not constrained by day care or work schedules, flock to these public spaces during their leisure hours. This temporal and spatial concentration of people—driven by the adjusted daily rhythms of the city—is what shifts the health impacts, turning these ‘cool’ areas into new hotspots of low resilience. Thus, while the vulnerability of a park or beach as a place is low, its dynamic resilience (measured as health impact) also becomes low. This occurs because vulnerability is not fixed; it is mobile and is effectively ‘imported’ to these districts by the very individuals performing the adaptive behaviour.

Diagrams illustrating three hypothesised associations between vulnerability (horizontal axis) and resilience (vertical axis): (a) positive association, where higher vulnerability co-occurs with higher resilience; (b) negative association, where higher vulnerability co-occurs with lower resilience; and (c) no association, where resilience remains approximately constant across levels of vulnerability. Arrows indicate the direction of the relationship; shaded 3×3 grids provide a qualitative reference for joint low–medium–high combinations.

Furthermore, propositions P2 and P6 combined (time and space) help in understanding the inconsistencies and intricate relationships underlying heat vulnerability indicators, as identified12,35. The observation that green and blue areas can become hotspots also has implications highlighted by critical heat studies. This phenomenon hints at the complex interplay of urban design, access to resources, and population movement during heatwaves, which can have equity dimensions54. argues that historical and ongoing processes of social and environmental injustice, including exclusionary urban planning and potentially ‘heat gentrification’, contribute significantly to inequalities in vulnerability and resilience. The increased demand in these ‘cooler’ spaces might disproportionately affect more vulnerable populations who rely on them, further emphasising the need to consider the social and spatial justice implications of heatwave responses.

In conclusion, we have shown that non-linear relations between vulnerability and resilience for heatwaves go in both directions: the more vulnerable, the less resilient (negative), as well as the more vulnerable, the more resilient (positive) (Fig. 7). These relations, however, depend on two factors: the time of the day and the underlying urban social fabric that forms adaptive capacity. Given the limited resources of healthcare providers, it is critical to understand how resilience and, potentially, vulnerability fluctuate over the day.

The second set of propositions highlights the implications for urban vulnerability and resilience metrics (P1, P3, P6) (see Table 3). Our findings highlight the need to design localised strategies for specific spatial, temporal, urban and social contexts. Therefore, there is a need for metrics that are tailored to the unique vulnerability, resilience and their shared attribute—-adaptive capacity, of each city’s dynamic profile and context.

The most vulnerable districts in each study city are characterised by different demographic, socioeconomic and health attributes. Therefore, proposition P1 emphasises the importance of contextualising vulnerability assessments to account for each city’s specific urban social fabric. While it has been argued that there is a need for contextualised and multi-scalar approaches56,57, there is still a widespread push for unified ‘global’ vulnerability metrics to compare different regions, countries or cities58. Our results show that these standardised vulnerability metrics may fail to capture local nuances, leading to ineffective or misdirected interventions, even if the context seems very similar. This aligns with the call by critical heat studies to move beyond a purely meteorological understanding of heat and to consider the lived experiences and power relations that structure heat vulnerability53. Therefore, we argue that there is a need for hyper-localised vulnerability and resilience assessments that identify the unique characteristics of each urban area. Critically, if hyper-local heat-risk studies are conducted only where rich data exist, this very inequity will be reproduced in policy-making. Our open-source workflow and the data-substitution options outlined in Methods are a small attempt to lower the barrier to include all areas in a city.

The temporal analysis of resilience patterns revealed that citizen adaptive behaviour significantly influences the relationship between vulnerability and resilience (see Fig. 8). For instance, in The Hague, the highest ambulance call volumes were observed in the evening, suggesting that citizens might adapt during the hottest parts of the day but suffer from heat stress later. These observations highlight the dynamic nature of vulnerability and resilience (P3), driven by behavioural adaptations (P6). Some of these considerations were previously theoretically discussed, e.g. by59,60, yet here we provide empirical evidence and formulate propositions that can be tested in other contexts.

The figure highlights how adaptive behaviours during heatwaves can alter vulnerability and resilience landscapes within urban settings over relatively short periods of time. Grid cell colour labels, along with classifications such as ‘high-high’, ‘high-low’, and ‘low-high’, represent the relationship between vulnerability and resilience.

Even though the need to include temporal aspects in both vulnerability and resilience aspects is increasingly recognised (see, e.g. ref. 56), highly dynamic vulnerability assessments are currently primarily conducted for fast-moving systems such as transport61. In urban systems, there is often the underlying assumption that change is slow, and therefore, also resilience and vulnerability metrics follow a similar pace of annual updates22. Yet, here, we show drastic changes in vulnerability and resilience landscapes in the course of a single day, driven by citizens’ adaptive behaviour under variations in exposure. Therefore, urban resilience assessments should aim for metrics that capture changes in highly dynamic environments attuned to behavioural shifts, especially in fast-paced crisis responses under resource constraints.

The core of our conceptual framework is illustrated in Fig. 8, which depicts how individual adaptive behaviours, unfolding in time and space, drive dynamic shifts in district-level vulnerability-resilience relationships. The figure suggests that resilience and vulnerability are properties that arise from the interaction of exposure and sensitivity (moderated via the built environment and social characteristics) and emergent behavioural patterns. These findings also have implications for the ongoing debate between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ approaches for resilience and vulnerability assessments62. We argue that because resilience emerges from an interaction of ‘objective’ factors like spatial attributes (see, e.g. ref. 63 for a review) and ‘subjective’ actions and interactions (as, e.g. in ref. 64), there is a need for more integrative metrics that consolidate objective and subjective elements.

Figure 9 illustrates the spatio-temporal data model that enables our conceptual framework. Here, resilience and vulnerability can be measured hyper-locally in space, and the different layers of the cube represent the changes of both aspects over time, driven by citizens’ adaptive behaviour and exposure changes. Such a data model allows us to discern the ‘objective’, static and generic aspects of urban vulnerability that do not change over time (e.g. UHI) from the ‘subjective’ aspects that change depending on the emergent system properties (e.g. citizen adaptive behaviour).

Each grid cell depicts a specific area in a city with a unique urban and social fabric, while the stacked surfaces correspond to different time intervals. Colours indicate the bi-variate relationships between resilience and vulnerability, capturing both static and dynamic aspects influenced by adaptive behaviours and environmental change.

This exploratory study represents an initial empirical exploration into the complex spatio-temporal interplay between urban vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves. Our findings and the resulting propositions aim to stimulate further academic discussion and research, particularly on heatwave-specific metrics and the broader challenge of measuring urban vulnerability and resilience effectively. We encourage the testing and refinement of our propositions across diverse geographical locations and contexts.

Recognising the evolving landscape of urban vulnerability and resilience assessment methodologies, we acknowledge several limitations inherent in our chosen scope and approach.

Consistent with principles of responsible data use in smart city contexts65, our analysis relies exclusively on openly available socio-demographic, health, and built environment data (detailed in Data sources and substitutes for data-scarce environments). While these datasets represent a standard set in heat vulnerability research9, they may not capture the full spectrum of vulnerability factors66. For instance, incorporating occupational data could illuminate the specific risks faced by outdoor workers (e.g. construction workers) during heatwaves. Furthermore, integrating behavioural data, perhaps gathered through map-based surveys64 or anonymised mobility tracking67, has significant potential for enriching the spatio-temporal understanding of vulnerability as people move through the city during extreme heat events.

Our chosen method for operationalising vulnerability, NMF, while generally less sensitive to hyperparameters than alternatives like Principal Component Analysis (PCA)68,69, still involves analytical choices that influence the resulting vulnerability profiles. Future work could systematically explore different hyperparameter settings to assess the robustness of our findings. Additionally, while traditional vulnerability assessments often prioritise identifying the ’most vulnerable’ districts, our primary goal was to uncover relationships between vulnerability and resilience. This focus means that areas experiencing fewer or less intense vulnerability factors might be less prominent in our analysis, even if they still face heat-related challenges70.

We utilise the percentage difference in ambulance calls during the heatwave as a proxy for resilience. The high accessibility of ambulance services in the Netherlands strongly supports this approach within our study context. However, applying this proxy directly to other countries or regions would require careful consideration and potential adjustments to account for significant variations in healthcare system accessibility and health-seeking behaviour (see National and city-scale initiatives against heatwaves in the Netherlands for a more elaborate discussion).

We recognise the limitations of using static indices to capture vulnerability to a dynamic hazard like a heatwave71. While vulnerability is often measured as a spatial attribute, our findings highlight that it is profoundly dynamic. To truly understand heatwave impacts, future research must aim to integrate temporally explicit data, such as hourly temperature variations and dynamic population movements derived from open mobility data67. Getting such high-resolution temporal data remains challenging, yet it is crucial for advancing our models of both vulnerability and resilience dynamics19.

Finally, our analysis focused on a single, significant heatwave event in July. Investigating heatwaves occurring in different months could reveal important variations in vulnerability and resilience dynamics influenced by seasonal context.

Overall, our findings make three significant theoretical contributions to urban resilience and vulnerability literature. First, our temporal propositions (P1, P2) challenge the conventional conceptualisation of vulnerability as a static spatial attribute by demonstrating how resilience dynamically fluctuates in response to changing exposure and eroding coping capacity. This advances theoretical frameworks that have traditionally treated vulnerability as temporally stable constructs16,17. Second, our propositions on urban social fabric (P3, P4) extend existing theory and the widely-used indicator frameworks by empirically demonstrating that vulnerability profiles are not transferable between contexts, even within seemingly similar cities, requiring theoretical models that accommodate this local differentiation18,19. Third, our spatial propositions (P5, P6) offer theoretical insights into how adaptive behaviour at the individual level transforms the vulnerability-resilience relationships at the district level, revealing counterintuitive patterns that existing theories on adaptive capacity25,59 and green infrastructure benefits5,46 have not adequately captured.

Collectively, these contributions advance the theoretical understanding of urban vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves as dynamically interlinked through adaptive capacity, evolving across both space and time rather than existing as separate constructs. Future research should continue to explore these theoretical dimensions, developing more sophisticated conceptual models that capture the complex interplay between vulnerability and resilience in urban settings. This includes investment in open environmental and health data infrastructures for underrepresented cities, so that hyper-local, dynamic mapping does not remain a privilege of the Global North.

Methods

The three largest Dutch cities under the 2019 European heatwave

We study the three largest Dutch cities delineated by the official municipal boundaries: The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam, with a total population of 537,833, 644,618 and 862,965 and an area of 98,12, 132,08 and 219,3 km2 on January 1 2019. All three cities can be characterised as extremely urbanised, meaning that they have an average density of 2500 or more addresses per km2 and have a strong Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect72,73,74. The cities are also known for being segregated, leading to rising urban inequalities75. A high population density, UHI, and a diverse urban social fabric make these cities useful exemplars for studying the relations between vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves.

The Dutch population does not have a long-lasting history of dealing with extreme heat and heatwaves. Since 2000, the Netherlands has had five exceptional cases: the heatwaves of 2006, 2010, and 2018, the July 2019 European heatwave and August 2020. The most devastating one is the 2006 heatwave. An increase in 6. 6°C from the average of 28 °C resulted in a significant rise in mortality: 1000 extra deaths compared to the average3. The next heatwave in 2010 had a similar rise in temperature and took 500 extra lives. The 2018 heatwave did not result in such a major increase in mortality, but remarkably, it was preceded by a major flu, which caused a significant rise in deaths in February 201876. The effect of the most recent heatwave in 2020 lasted from 10 to 16 August and was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The population group that was hit the hardest, with an increase of 37% from the average, was the ones living in long-term care facilities77. Remarkably, the mortality rate was still rising a week after the heatwave.

The heatwave of this study, the July 2019 European heatwave, lasted only 6 days, from July 22 to July 28, but the temperature in many parts of the country renewed historical maximums. For instance, a new record in 39. 2°C was recorded at the Gilze-Rijen weather station near Breda. This heatwave claimed at least 400 extra deaths3. Official statistics point out that the rise in mortality was unequal among different age groups. According to the data for the 2006, 2018 and 2019 heatwaves, increases in mortality were the highest among people of two age groups: 65–79 and over 80 years old. CBS also reported that the impact of at least two heatwaves was unequal geographically. In 2006, the south of the country (North Brabant, Limburg) was affected the most, whereas in 2019, it was the east (Overijssel, Gelderland, Flevoland). It is important to note that mortality is not the only way to measure the damage caused by heatwaves. Besides the fatal outcomes, extreme heat may significantly worsen a person’s health, but keep him or her alive. Mortality numbers indicate the importance of the problem, but do not cover the broad range of health consequences that could be captured with the use of ambulance call data.

National and city-scale initiatives against heatwaves in the Netherlands

The Netherlands recognises the importance of the extreme heat threat. In 2007, the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) created the first version of a National Heat Plan37. The National Heat Plan defines the conditions under which there is a threat, the responsible actors to whom the threat should be communicated, and actions that should be taken by the citizens to minimise the consequences. The current version of the plan has a 25 °C daily temperature for five consecutive days as a threshold. If the forecast of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) indicates so, the plan must be activated, and all key actors must be informed. The RIVM defined a series of straightforward recommendations for the citizens: drink more water, be in the shade, and ventilate living places. Besides that, the RIVM also recognises the importance of caring for each other’s neighbours as an essential action. The last action in the recommendation list emphasises it with a statement to pay extra attention to people in need.

The municipality of The Hague developed a draft local heat plan in the summer of 2021, which was published in February 202278. This plan aimed to address the effects of heatwaves on vulnerable population groups in The Hague and suggest ways the municipality could help them cope. The research that informed this plan, conducted in 2021, focused on independently living senior citizens and aimed to understand their characteristics, needs, and existing solutions, as well as how the municipality could improve communication and urban resilience regarding heat. The Rotterdam Weatherwise 2030 programme framework79, with a 2019 Urgency Document highlighting climate challenges80, including heat, outlines the city’s approach to climate adaptation. This framework includes a ‘heat plan during heat waves’ as one of its impact investments, with the municipal health services (GGD Rotterdam-Rijnmond) tasked with creating a Rotterdam heat plan using the RIVM’s National Heat Plan as a guideline. The first version of the local Amsterdam heat plan was created in the autumn of 2022 by the Municipality of Amsterdam and the GGD Amsterdam, collaborating with various care and social organisations81. This plan describes different action phases during heat events, including preparation, pre-warning, warning, and evaluation, with prevention efforts occurring year-round. The development of this plan involved evaluating the summer of 2022, which experienced two heat periods, to identify actions taken and those still needed.

During the 2019 European heatwave, the Dutch response relied on the National Heat Plan; today, that national framework is reinforced by city-level heat plans that turn its guidance into concrete local action.

Data sources and substitutes for data-scarce environments

Our study utilises five open data sets to study the impact of the 2019 European heatwave on the population of the three biggest Dutch cities: The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam, namely socio-demographic and economic, health, UHI effect, temperature and ambulance calls. Note that we focus on the corresponding municipalities, not the larger metropolitan areas, as the ones with a higher population and built environment density, footfall, and traffic. We recognise that such granular data is often unavailable in data-scarce environments (for example, many cities in the Global South), and we also compile a set of low-cost or global substitutes that could potentially replace the ones used (Table 4).

To analyse citizens’ socio-demographic and economic characteristics, we use an open dataset ‘Key figures for districts and neighbourhoods 2019’ (Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2019 in Dutch) provided by Statistics Netherlands and available to download at https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2019/31/kerncijfers-wijken-en-buurten-2019. This dataset reports yearly changes across various socio-demographic and socio-economic attributes critical for heatwave vulnerability assessment, such as age group, ethnicity, family composition, income, etc. The data is provided at district and neighbourhood scales for each Dutch city.

‘Health and lifestyle per neighbourhood, district and municipality’ (Gezondheid en leefstijl per buurt, wijk en gemeente in Dutch) provides us information about residents’ health. This dataset results from a national survey conducted in 2016 jointly by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and Statistics Netherlands. It is available for download at https://buurtatlas.vzinfo.nl/#home. The dataset contains information about the fraction of residents experiencing certain health problems: mobility issues, prolonged sickness, etc., which, taken together with socio-demographic and economic attributes, can help to conduct heatwave vulnerability assessment.

The Urban Heat Island (UHI) data is available at the Climate Impact Atlas https://www.klimaateffectatlas.nl/en/and provided by Atlas Natural Capital https://www.atlasnatuurlijkkapitaal.nl/. The data set reports the UHI effect in degree celsius as an average air temperature difference between the urban and surrounding rural areas. The UHI is calculated based on population density, wind speed, and the amount of green, blue and pavement (read more about the methodology at https://www.atlasnatuurlijkkapitaal.nl/stedelijk-hitte-eiland-effect-uhi-in-nederland). The dataset is a raster file of 10 m resolution, and to align it with our analysis, we aggregate it over the districts and take the median of the resulting values.

P2000 is part of the Dutch C2000 alarm network maintained by the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. The network uses the FLEX protocol developed by Motorola and uses emergency pagers as information receivers. P2000 is an open network with information publicly available via multiple websites, which enthusiasts run, e.g. https://www.p2000-online.netand https://alarmeringen.nl. For this study, we contacted the owners of https://112-nederland.nland requested a data dump from 2019. One specific type of message that this network registers is for ambulances. The calls are anonymous and do not have information about who called or the reason for the call. It has, however, a timestamp and a 4 or 6-digit postcode, which we convert into a pair of coordinates by taking the middle point of the postcode where it was made.

To collect hourly temperature measurements of The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam for the heatwave period (July 22–27, 2019), we use an API from Dark Sky, a multi-platform app and service providing accurate and up-to-date weather information. Note that as of 2023, the Dark Sky API is no longer accessible since Apple acquired it in early 2020. While there are many other ways to get temperature data, Dark Sky API provides more conventional access to its data. It also operates with the aggregated measurements of many weather data sources, e.g., the German Meteorological Office, EUMETNET, etc.

Analytical framework

This study uses open data to explore the spatio-temporal link between citizens’ vulnerability and resilience to heatwaves in The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. While our indicators of vulnerability (e.g. age, income) and resilience (person’s ambulance call) are defined at the individual level, we analyse them at the district level due to the granularity of the data available.

Following9, we treat heat vulnerability as a meta-attribute of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Each is linked to measurable attributes drawn from prior work82: for instance, the share of residents with serious health conditions captures sensitivity83. A district’s vulnerability profile combines these variables extracted with NMF.

Resilience, likewise a meta-attribute, combines recovery, adaptation, and transformation84. Each sub-component corresponds to temporal scales of the system’s response to a heatwave: short-term (recovery and adaptation): behaviours like seeking parks; mid-term (adaptation and transformation): community training programmes; long-term (transformation): changes to the built environment10. In this study, we focus exclusively on short-term adaptive capacity. We capture it by measuring excess ambulance calls during heatwave days, relative to the baseline across each city’s districts.

Building on ref. 25, we hypothesise that adaptive capacity sits at the intersection of vulnerability and resilience. While many scholars treat these concepts as opposites or loosely related17,19,50, we explicitly examine how the most vulnerable districts (as identified by their NMF profiles) respond to the heatwave. We do this by comparing each district’s vulnerability profile to the change in ambulance calls during heatwave periods, thereby revealing how underlying vulnerability is linked to observed resilience and changes in adaptive behaviour.

Vulnerability generally refers to the susceptibility of a system to experience damage or adverse effects when exposed to shocks or stressors. Operationalisation of vulnerability depends on the type of stress or shock and the system of interest. In climate change research, vulnerability is often deconstructed into exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity8. In the case of extreme heat, these three sub-attributes dominate the discussion, highlighting how they interact to affect populations differently85. When the focus shifts to urban areas, the ’system’ becomes the city itself, encompassing the interplay between the citizens and their interactions with the urban social fabric under heat stress38.

Conceptually, urban vulnerability to heatwaves is dynamic and changes over time. Temperatures and thus exposure change hour by hour. People’s behaviours and movement patterns evolve over the day, and so does their adaptive capacity. Most urban heat vulnerability studies simplify this into a purely spatial analysis9. In this study, we adopt this common approach to test its limits and reflect on the implications Table 4.

We compile district-level data on socio-demographic (e.g. age, household composition), economic (e.g. income), health (e.g. prevalence of chronic illness), behavioural, and built-environment (e.g. UHI effect) variables (Table 5). This follows the methodology and key categories identified in recent reviews9,86 and highlights districts with high concentrations of elderly residents or low-income households that are more vulnerable to heat83.

Some variables ‘sit’ on multiple dimensions. For example, age usually indicates sensitivity, but when combined with single-parent status, it also limits adaptive capacity; single parents may be unable to leave home during extreme heat to care for dependents. This overlap explains why we focus on overall vulnerability rather than adaptive capacity alone. We also want to acknowledge that no index is perfect40 and our goal is not to conduct a flawless assessment, but rather minimise the bias by applying a common set of variables and pinpoint where a purely spatial approach may misrepresent ‘true’ vulnerability.

Despite recent research highlighting its limitations69,87, PCA remains the most common tool for operationalising heat vulnerability. According to a recent review, about 35% of studies employ it to reduce complexity and combine variables into principal components9. However, PCA’s orthogonal components can also be abstract and include negative loadings that lack real-world meaning. To produce more interpretable and robust results, we instead use Non-negative Matrix Factorisation (NMF) and its implementation in scikit-learn88, which decomposes our vulnerability data into two non-negative matrices89.

Algorithmically, NMF seeks two matrices, W and H, whose product approximates the original data matrix V (size n × m). By constraining both of them to be non-negative, NMF inherently produces additive, ‘building-block’ components: each column of W represents a distinct ‘vulnerability profile’ (for example, a mix of high elderly share and UHI effect), and each column of H shows how strongly each district exhibits those patterns. NMF not only helps to identify patterns with factorisation of the input matrix V, but thanks to its inherent clustering property, it also helps to reveal clusters in the data corresponding to specific socio-demographic or built environment factors contributing to vulnerability.

Our vulnerability input matrix V (size n × m, where n is the number of districts and m the number of socio-demographic, economic, health, behavioural, and built-environment features listed in Table 5) is first scaled to the [0, 1]. We then fit NMF to each city’s data individually with component numbers ranging from two to ten, evaluating each on reconstruction error and most importantly, whether the resulting W and H matrices result in clear, interpretable ‘vulnerability profiles’. For our three case cities, a four-component solution offers the optimal balance of low error and meaningful pattern separation. Although the choice of component number remains inherently subjective and may vary across cities, the pronounced segregation and inequalities in our case cities tend to produce stable, easily distinguishable clusters.

For example, after running NMF, Profile 0 in Amsterdam (see Fig. 2c) emerged as a distinct vulnerability profile. This profile is defined by a high contribution of residents aged 65+, individuals with mobility limitations, and high UHI exposure. A district in Amsterdam would then have a high score for this profile if it has a large concentration of these specific features, allowing us to identify it as ‘highly vulnerable’ based on this specific pattern.

Generally speaking, resilience is the ability to recover from a shock. Urban resilience describes a city’s capacity not only to recover from shocks but also to adapt and ultimately transform10. Like vulnerability, defining resilience requires answering two questions: what is the shock (resilience to what), and what is it to be resilient (resilient of what)? However, defining and measuring urban resilience is challenging due to the intricate and interconnected nature of city systems90. A heatwave’s impact not only affects residents’ health but goes well beyond: increasing temperatures put pressure on energy grids, degrade transportation systems, and can trigger cascading failures across sectors91.

Resilience unfolds across multiple time frames. In the short term, individuals alter behaviour, seeking shade in parks or adjusting daily routines, to relieve immediate heat stress. Over weeks to months, community institutions may roll out targeted cooling centres, conduct public training on heat safety, or tweak building operations. In the long run, urban form itself can be reimagined through expanded green and blue spaces, retrofitting buildings, to transform the city’s capacity to withstand future heat stress10,92.

Research into urban resilience heat often focuses on the role of green and blue infrastructure in mitigating the effects of heat92,93. However, there is a notable gap in understanding the immediate behavioural responses of affected individuals94 or short-term resilience. For example, during a heatwave, residents living in a UHI might seek relief by visiting parks, thus exhibiting adaptive behaviours that alleviate the heat’s immediate pressures18. Low-income, single-parent households often cannot seek relief elsewhere, since caregiving responsibilities keep them at home51. Such individual decisions highlight the system’s adaptive capacity, a key component of resilience.

Resilience can be assessed using various methodologies: a single proxy, a set of indicators, or a composite index63,86. Each approach has limitations and, much like vulnerability assessments, captures only a fraction of the ’true’ resilience of a system95. This echoes the broader challenge in resilience studies: balancing the utility of these assessments with their inherent incompleteness, aiming to provide actionable insights rather than definitive answers19. Embracing the diversity of viewpoints on resilience may enrich our understanding, though it also poses challenges in harmonising these perspectives into actions25.

We propose to measure resilience as spatio-temporal excess in ambulance calls during a heatwave, providing a concrete proxy of how citizens respond to extreme temperatures. Specifically, we compare calls made between 22 and 28 July (the ‘heatwave week’) against the hourly averages of all other summer weeks in 2019 measured at the district scale. Recent studies have demonstrated a strong link between heatwaves and increased emergency call rates in cities6,52,70,71. Moreover, because ambulance calls capture real-time morbidity rather than just mortality, they provide richer insights into population health during extreme events23. However, what is missing is how citizens’ adaptive behaviours modify these call patterns. To interpret such behavioural impacts accurately, we must rely on high-resolution spatio-temporal data.

Table 6 presents a snapshot of what the ambulance call data looks like. Our hypothesis is as follows. In a country like the Netherlands, where healthcare, including emergency services, is accessible to most of the population, the fewer the calls, the better. If, during the heatwave, a certain district shows more ambulance calls than the average, it has low resilience. While no ambulance calls are perhaps impossible, overall, the city might want to minimise this number.

More specifically, we aim to compare the total number of ambulance calls made during the heatwave from the 22nd to the 28th of July—a full week from Monday until Sunday, with the ‘average week’. The average week here is an average of all summer weeks of 2019, excluding the heatwave week. Note that the averaging is happening by hour. Thus, we add the number of calls made during 00:00 on Monday, for example, 3 June, to those made during 00:00 on Monday, 10 June and so on. Next, the averaging is happening by the district.

Let Cd,h,w represent the number of ambulance calls in district d, at hour h, during week w. Then, the heatwave week calls are:

This represents the number of calls during the heatwave at hour h in district d. Next, for non-heatwave summer weeks, let us denote this set of weeks as W), the average number of calls at hour h in district d is calculated as:

where ∣W∣ is the total number of weeks in the set W.

To compare the ambulance call rates during the heatwave to a typical summer week, calculate the percentage difference for each district d and hour h, using the following formula:

This formula calculates the percentage by which calls during the heatwave exceed or fall below the average calls for the same hour in the same district.

To illustrate, consider a district that typically averages 2 ambulance calls on a summer Monday between 16:00 and 20:00. If, during the heatwave Monday, it registered 4 calls in that same period, its resilience proxy would be %Δ = ((4 − 2)/2) × 100% = +100%, indicating a loss of resilience (an increase in acute health impacts). Conversely, a district that averaged 2 calls and registered 2 calls again would have a %Δ of 0, indicating it coped without an increase in emergencies.

Several pros and cons emerge when evaluating the efficacy of using ambulance call data as a proxy for measuring urban resilience. Ambulance data offer very high spatial and temporal resolution, giving a near-real-time view of how populations respond under the acute stress of a heatwave. This level of detail makes it possible to track the timing, location and intensity of health-related impacts, and thus to infer the city’s immediate adaptive capacity.

Yet this proxy also has clear limitations. Changes in call volumes may understate or overstate ‘true’ resilience if taken in isolation, since they assume that all residents have equal ability and willingness to access emergency care. In the Dutch context, this assumption is relatively safe. The Dutch healthcare system provides universal medical care coverage through a compulsory social health insurance. Everyone registers with a general practitioner (GP) who acts as a ‘gatekeeper’ for medical care and may call the national emergency number for life-threatening situations. Although self-referral to emergency departments is possible, the system is structured in such a way that individuals often first need to consult their GP, and GP cooperatives provide out-of-hours care, aiming to manage urgent but non-life-threatening situations96.

Transferring this approach to cities with different healthcare requires extra attention. In systems where insurance coverage is uneven, facilities are distant, this proxy alone could provide misleading results. To adapt effectively, ambulance data should be combined with other context-specific indicators of access, health-seeking behaviour and social vulnerability.

Additionally, the complexity of urban systems makes relying on a single proxy problematic. Cities are dynamic entities with multiple interacting components, and resilience cannot be fully captured through one-dimensional metrics. Therefore, while ambulance call data can be a useful component of a broader set of indicators, it should be integrated with other proxies that illuminate different aspects of the urban resilience landscape, e.g. citizen-level mobility data97 or general-practitioner consultation records98. Such integration can provide a more robust and nuanced understanding of how cities cope with and adapt to various shocks.