Abstract

Nickel (Ni) is a magnetic transition metal with two allotropic phases, stable face-centered cubic (FCC) and metastable hexagonal close-packed (HCP), widely used in structural applications. Magnetism affects many mechanical and defect properties, but spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations are computationally inefficient for studying material behavior requiring large system sizes and/or long simulation times. Here we develop a “magnetism-hidden” machine-learning Deep Potential (DP) model for Ni without a descriptor for magnetic moments, using training datasets derived from spin-polarized DFT calculations. The DP-Ni model exhibits excellent transferability and representability for a wide-range of FCC and HCP properties, including (finite-temperature) lattice parameters, elastic constants, phonon spectra, and many defects. As an example of its applicability, we investigate the Ni FCC-HCP allotropic phase transition under (high-stress) uniaxial tensile loading. The high accurate DP model for magnetic Ni facilitates accurate large-scale atomistic simulations for complex phase transformation behavior and may serve as a foundation for developing interatomic potentials for Ni-based superalloys and other multi-principal component alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deformation mechanisms and mechanical properties are fundamental topics in the study of metallic materials. For most coarse-grained metals and alloys, their strength and hardness increase with decreasing grain size, following the Hall-Petch relationship. Plastic deformation is primarily accommodated through dislocation motion and grain boundary processes. However, when the grain size is reduced to the nanometer scale, the material’s strength and hardness are mainly governed by stacking faults or twins, exhibiting an inverse Hall–Petch behavior. Phase transformations can also influence the mechanical response of metals and alloys; e.g., transformation-induced plasticity is particularly significant in nanostructured metallic systems at high stress1,2,3,4. Ni is a typically high stacking fault energy face-centered cubic (FCC) metal which primarily deforms through partial dislocation motions and/or twinning5,6,7. At high-rate shear rates, the FCC lattice becomes unstable, leading to an FCC-to-hexagonal close-packed (HCP) transformation2,3 in nickel with grain size smaller than ~17 nm. Such a microstructure of HCP grains surrounded by FCC grains exhibits high hardness and yield strength compared to a fully FCC microstructure2. HCP nickel is also widely observed in thin hetero-epitaxial films8,9. The thermodynamics for this FCC → HCP in nickel remains unclear2,3,4,8. To elucidate such phenomena, atomistic simulations must accurately reproduce both the stable and metastable thermodynamics of this material as well as its mechanical response. Such robustness in the description of bonding in metals is necessary in many applications of nanostructured metallic systems.

Density-functional theory (DFT) can provide a highly accurate, quantum mechanics-based approach to understanding the structure and properties of metals, but its applicability to the properties of defects and finite temperature behavior is limited by the large computational demands required for reasonable system size and time scales. Although most structural applications of nickel (a soft ferromagnet below 627 K) do not depend on its magnetic response, many non-magnetic properties depend sensitively on its electronic spin degrees of freedom. Inclusion of magnetic degrees of freedom impacts phase stability10,11, vacancy and self-interstitial formation energies12,13,14,15, elastic moduli10,16, stacking fault energies17,18,19,20, and mechanical properties, as seen in DFT calculations. For example, the elastic constants of Ni determined in non-spin polarized DFT are in error by as much as ~23%16 compared with experiments, while spin-polarized DFT results are in much better agreement with experiment21. Stacking fault energies in Ni, determined from DFT with and without spin degrees of freedom differ by 24–50%17,18. Hence, magnetism is important for the prediction of a wide range of non-magnetic (structural) properties. DFT calculations of a reasonable number of spin-polarized (say 103–5 atoms) and long time scales (> 1 ns) are heroic.

Empirical or semi-empirical interatomic potentials are routinely employed to enable the simulation of the properties of metals and their defects on these scales. Over the past fifty years, dozens of Ni potentials have been developed (e.g., see refs. 22,23) and achieved some successes in explaining experimental observations and predicting material behavior. However, the transferability and accuracy of these potentials are limited by their fixed functional form; this concern is particularly acute in determining the properties of non-equilibrium structures, such as, HCP Ni. We benchmarked the basic properties of FCC and HCP Ni using various interatomic potentials, including eight embedded-atom method (EAM) and ten modified embedded-atom method (MEAM) potentials (see Supplementary Table 1). All potentials display significant discrepancies in simple properties, such as the elastic constants (Cij) of metastable HCP Ni (possibly due to the limited availability of fitting data); these deviations can be as high as 41% (see C13, C33, C44 in Supplementary Table 1). This makes accurate prediction of the mechanical (elastic and plastic) deformation of HCP Ni (as well as other non-FCC phases) and phase transitions in Ni using these potentials unreliable.

One approach to achieving accurate and efficient atomistic simulations of, e.g., allotropic phase transformations, is through transferable machine-learning (ML) based interatomic potentials (see ref. 24 for a recent example for titanium). Developing accurate ML potentials relies on accurately fitting the potential energy surface (PES). The PES may be strongly influenced by magnetic moments (in magnetic systems). Accurately capturing these magnetic effects is essential for constructing a reliable PES, yet it remains a formidable task for ML potentials. ML approaches that simply ignore magnetism25,26 lead to unreliable potentials for predicting several fundamental properties (see “Results and discussion”).

Incorporating spin-polarized DFT training datasets into the training process is a straightforward strategy for developing ML potentials for magnetic systems. This approach has been explored in the Gaussian approximation potential27,28,29,30 and neural network potentials (NNPs)31. However, these potentials often lack sufficient transferability and representational capabilities across diverse properties27,28,29,30,31. The deep potential (DP) method, a successful and widely adopted form of NNP32,33, rarely employs spin-polarized training sets33,34. Here, we account for magnetic effects on (non-magnetic) properties by training the DP model on spin-polarized DFT calculation results (without explicitly including magnetic moment degrees of freedom). We demonstrate, such “magnetism-hidden” potentials are applicable to the robust prediction of non-magnetic properties for both FCC and HCP phases, specifically, for accurate description of finite temperature and defect (point defect, surface energies, stacking fault, dislocation core, grain boundary) properties and allotropic phase transformations. The resultant interatomic potential for nickel is unusually, extremely accurate, robust, and transferrable; capable of describing metastable phases, phase transformations and defects. Our approach serves as a model for developing, relatively simple ML NNPs for structural (magnetic) materials.

Results and discussion

The DP model for Ni (DP-Ni) is trained via a supervised ML technique. The training labels include atom coordinates, total energy, atomic forces, and virial tensors, obtained from spin-polarized DFT calculations. We employ the DP-GEN framework32 along with the DeepPot-SE35 to conduct the training. A “specialization” strategy24 is adopted to further improve the accuracy. Initially, distorted 2 × 2 × 2 body-centered cubic (BCC), FCC, and HCP structures are input into finite-temperature ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to generate a starting training dataset (108 entries). During the DP-GEN loop, exploration involves DP-based MD (DPMD) simulations on bulk and surface structures for several temperatures and pressures, followed by DFT calculations on selected configurations. The resultant DFT data is then incorporated into the training dataset to refine the DP models. Convergence of the DP-GEN loop is achieved when the agreement between DP and DFT calculations for atomic forces reaches a predetermined threshold.

Following the DP-GEN loop, the resulting DP model can accurately represent the general properties of FCC and HCP Ni albeit with some discrepancies in the cohesive energy curve compared to DFT results. To address this, specialized training datasets are generated from selected configurations along the cohesive energy line. These specialized training datasets are then merged with those generated from the DP-GEN loop. The combined training dataset used for potential development consists of 2020 entries, all derived from spin-polarized DFT calculations. For a comprehensive discussion on the training process and training data generation, please refer to “Training Strategy of Deep Potential for Ni”.

We systematically benchmark a wide range of crystal and defect properties of DP-Ni; in particular, we examine equations of states, elastic constants, finite temperature properties, phonon spectra, point defect energies, surface properties, stacking fault energies, plastic deformation, dislocation dissociation, and grain boundary energies. We compare the DP-Ni model performance against several of the most widely-used and best-performed empirical/semi-empirical interatomic potentials, including the EAM potential of Mishin et al.36, the MEAM_2021 potential of Vita et al.37, the MEAM_2015 potential of Ko et al.38, and the ML qSNAP potential by Zuo et al.25. These benchmarks provide a comprehensive assessment of the performance of our new DP-Ni model with other widely-used interatomic potentials for Ni. (Note that since these benchmark potentials all involve some DFT data in their fitting procedure, we provide some details for the DFT calculations they employed in the Supplementary Note 4).

Basic crystal properties

Table 1 compares a wide range of crystalline Ni properties with DFT calculations, experiment, DP-Ni, and other interatomic potentials. The DP-Ni shows excellent agreement with both DFT and experimental values for the stable FCC and metastable HCP crystals. The energy difference between DP-Ni and DFT is within 3 meV/atom for both FCC and HCP Ni, while the lattice parameter difference between DP and DFT/experiment is within 0.004 Å. The EAM, MEAM and qSNAP potentials also exhibit accurate lattice parameters for both phases, with discrepancies less than 2% when compared to DFT and experimental results. The DP-Ni model shows a slight deviation of the cohesive energy from the experimental data but accurately reproduces the DFT value for FCC Ni (this is likely associated with issues related to the DFT data to which DP-Ni is trained). EAM and MEAM_2015 potentials perfectly match the experimental cohesive energy of 4.450 eV/atom as required in their fitting procedure, while MEAM_2021 underestimates it by ~11%. In contrast, qSNAP potential exhibits a large deviation ~30% from the experimental data. DP-Ni yields cohesive energy that is almost identical to the DFT prediction for HCP Ni. Similarly, EAM and MEAM_2015 yield results close to the experimental measurements, while the other interatomic potentials exhibit significant deviations from both DFT and experimental results.

Elastic constants are fundamental and essential material properties reflecting mechanical stability and stiffness. The largest discrepancy between DP and DFT/experiment for DP FCC Ni is for C44 (2.3%)/C11 (6.8%); all other interatomic potentials also accurately reproduce the elastic constants of FCC Ni (except for a slight underestimation of C44 for the MEAM potentials). For HCP Ni, the predicted Cijs from DFT and DP yield mechanical stability according to the Born criteria39; i.e., C11 − ∣C12∣ > 0, \(({C}_{11}+{C}_{12}){C}_{33}-2{C}_{13}^{2} \, > \, 0\) and C44 > 0. DP-Ni accurately reproduces the DFT elastic constants of HCP Ni, with a maximum deviation at C12 (9.6%). On the other hand, all other potentials show large deviations in the elastic constants of HCP Ni as compared with DFT results; particularly for EAM at C13 (37.4%), C33 (35.5%), and C44 (15.9%), and the other three potentials at C44 31.5%, 39.1%, 39.1% for MEAM_2021, MEAM_2015, and qSNAP, respectively. (Note that deviations between the DFT data and this widely-used EAM potential may arise, in part, from the fact that this EAM potential was fitted to a different form of DFT calculation—specifically a first-principles linearized augmented plane-wave (LAPW) method with a Perdew-Wang parametrized local-spin-density (LSD) approximation). The elastic constants measure the (stress) response of the crystal to small strains and are indicative of sensitivity to lattice distortions. The training data for the DP-Ni includes many such locally distorted structures (see “Training Strategy of Deep Potential for Ni”). No HCP crystal distortions are included in the fitting data of the classical and ML qSNAP potentials.

Phonon spectra

In addition to the Born mechanical stability criteria and cohesive energies, phonon spectra40 also characterize crystal stability. Figure 1 shows the phonon spectra of both FCC and HCP Ni obtained from experiment41, DFT, DP-Ni, and other interatomic potentials. Both FCC and HCP Ni are inherently stable (no imaginary frequencies). However, notable variations in accuracy are observed amongst the different potentials. DP-Ni demonstrates outstanding performance in both FCC and HCP crystal structures, reproducing all frequencies across the phonon spectra with high accuracy. Minor deviations are observed for qSNAP potential (particularly the HCP). Other classical potentials exhibit evident deviations from the DFT and/or experimental data at symmetry points.

a FCC and (b) HCP. The experimental values are from FCC Ni neutron diffraction data at 298 K41, and the HCP DFT data is from this work.

FCC surface energies and point defects

In Table 2, the unrelaxed energies of low Miller index surfaces calculated by DP-Ni are compared to values obtained from DFT, experiment, and other potentials. Our DFT results are consistent with both the values and ordering of previous DFT calculations42. DFT predicts that the {111} close-packed plane has the lowest surface energy, whilst the {210} surface is the highest. All interatomic potentials successfully reproduce the lowest and highest energy planes. DP-Ni results show excellent agreement with DFT, exhibiting a maximum error of 2.2% for the {221} surface. MEAM_2021 and qSNAP potentials also provide accurate predictions (errors within 6%). However, EAM and MEAM_2015 potentials slightly underestimate surface energies by 11.4%–15.9% and 5.8%–15.1%, respectively. The quoted experimental surface 2.240 J/m2 is a polycrystalline average43. The vacancy formation energy (\({E}_{{{\rm{v}}}}^{{{\rm{f}}}}\)) from DP-Ni is ~0.124 eV which is 13.2% lower than the DFT value. All other potentials yield higher values than the DFT \({E}_{{{\rm{v}}}}^{{{\rm{f}}}}\) result but in the experimental range.

The FCC structure exhibits six types of self-interstitial structures, namely the 〈100〉 dumbbell, 〈111〉 dumbbell, 〈110〉 dumbbell, crowdion, octahedral, and tetrahedral (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The DFT calculations show that 〈100〉 dumbbell has the lowest formation energy in FCC, followed by octahedral, 〈111〉 dumbbell, tetrahedral, crowdion and 〈110〉 dumbbell. Note that the crowdion and 〈110〉 dumbbell energies are nearly equivalent, and relaxed configurations exhibit a slight difference. This energy ordering is consistent with other results44,45,46. DP-Ni captures all of the metastable configurations with a maximum energy discrepancy of < 6.8% (tetrahedral) compared to DFT results. However, a small inconsistency with DFT is the altered energy ordering sequence for DP, which is (from low to high): 〈100〉 dumbbell, octahedral, crowdion, 〈110〉 dumbbell, 〈111〉 dumbbell and tetrahedral. Almost all EAM potential self-interstitial energies are much higher than the DFT values, the octahedral interstitial is unstable, and the EAM 〈100〉 dumbbell is short. The MEAM_2021 captures all six self-interstitial configurations with small energy deviation compared to DFT, but the energy ordering is quite different. The 〈111〉 dumbbell and tetrahedral energies from MEAM_2015 are nearly the same after relaxation; the octahedral structure transforms into a 〈100〉 dumbbell. The qSNAP potential accurately reproduces all self-interstitial formation energies; however, the tetrahedral interstitial transforms to a 〈100〉 dumbbell.

Note that the training datasets for the DP-Ni potential do not include vacancy or self-interstitial configurations. This implies that DP-Ni accurately captures the essential characteristics of many defects in Ni even though such configurations are not included in the training data. This underscores the versatility and reliability of the DP-Ni model in predicting defect properties.

Cohesive and decohesive energy

The relationship between the cohesive energy and atomic spacing (cohesion curves) is critical for a wide range of properties. Figure 2 shows the cohesive curves for FCC Ni at 0 K, determined from DFT and interatomic potentials. The DFT, DP-Ni, MEAM_2021, and MEAM_2015 curves are smooth across the entire range. The DP-Ni and DFT curves nearly overlap, while the MEAM_2015 deviates from the DFT value near the equilibrium lattice parameter. In contrast, the MEAM_2021 results show large deviations from the DFT data in the crucial 0.5a0–2a0 range. The EAM curve remains continuous at large atom separations but exhibits discontinuities under large compression, with deviations from the DFT curve in the 1.25–2.0a0 range (recall the issue raised above regarding comparing our DFT and the EAM results). The qSNAP potential yields a discontinuous and inaccurate cohesive energy curve and its equilibrium FCC Ni cohesive energy is substantially different from the DFT results (see Table 1). This indicates that the qSNAP potential may introduce unexpected and significant errors in mechanical properties.

Examining the (uniaxial) surface decohesion energy and its gradient (stress) provides a deeper understanding of the energy landscape and forces involved in atomic plane separation; this is important for predicting and simulating fracture. Figure 3 displays the surface decohesion energy and its gradient for four crystallographic planes using DFT and interatomic potentials. No plane separation data is explicitly included in the DFT training datasets of DP-Ni. The DP-Ni model demonstrates excellent predictability compared with DFT for all planes. The MEAM_2021 and qSNAP potentials also show relatively good agreement with DFT data. However, significant deviations in energy and stress are observed for separation distance ranging from 0.5 < d < 3 Å for the {100}, {110}, {112} planes and 0.5 < d < 2.5 Å for the {111} plane. Additionally, the peak stress position for qSNAP is shifted to larger d (~1 Å). The EAM potential exhibits discontinuities for {100}, {110}, {111} planes for 1.5 < d < 3.5 Å, leading to unphysical fluctuating decohesion stresses. The EAM decohesion energies are much smaller than DFT for d > 1.5 Å. Peak stress values for the EAM potential are shifted to smaller d. The MEAM_2015 potential yields decohesion results largely in agreement with DFT results except for abrupt jumps at d ~ 2.5 Å.

Ideal strength

Smooth cohesive and decohesive energies are important for predicting (ideal) strength. Ideal strength is the maximum stress that a perfect material can withstand before undergoing plastic deformation or fracture47. This property can be identified through the stress–strain curve (a valuable tool for material application and design). We initially assess the ideal strength of FCC Ni under tensile and shear loading using DFT calculations; see Fig. 4 for the computed stress as a function of applied strain in various directions. At low strains, the curves are linear (linear elastic), while at higher strains the deviation from the linear elastic response is evident; the ideal strength (σideal) corresponds to the maximum stress or the stress at the peak strain (ϵideal). The stress–strain response is strongly anisotropic. For example, the σideal and ϵideal differ considerably between the [001] and [011] directions under uniaxial tension. Additionally, the (111)〈112〉 directions under shear stress show obvious “stiff” and “soft” tendencies. Overall, Ni shows σideal = 29.0 GPa and ϵideal = 0.52 under hydrostatic tension while σideal = 35.3 GPa and ϵideal = 0.41 in [001] uniaxial tension and σideal = 15.9 GPa and ϵideal = 0.28 in \((111)[\bar{1}\bar{1}2]\) shear.

Unlike elastic constants, ideal strength calculations involve significant (rather than infinitesimal) deformation and therefore represent considerable demands on the ability of a potential to accurately describe deformation. We conduct a comparative analysis of stress-strain relationships among various interatomic potentials using static calculations. The DP-Ni is in excellent agreement with the DFT results, especially for hydrostatic and [111] uniaxial tension, as well as \((111)[1\bar{1}0]\), \((111)[\bar{1}10]\) and \((111)[11\bar{2}]\) shear. The largest deviations observed are 10.4% and 9.3% in the non-linear region for [011] tension and \((111)[\bar{1}\bar{1}2]\) shear, respectively. The DP-Ni also reproduces the ϵideal in all cases. MEAM_2021 performs well in shear but overestimates the ideal strength and strain in hydrostatic and uniaxial tension. Similarly, qSNAP shows good performance in shear but overestimates σideal and underestimates ϵideal under hydrostatic and most uniaxial tension cases. The EAM model shows large deviations compared to DFT results, with a discrepancy of 58.7% under [011] tension (again, recall that the deviation of the EAM and DFT results may be associated with differences between the DFT method employed here and that used to fit the EAM potential). In comparison with DFT, MEAM_2015 exhibits minor discrepancies in hydrostatic but overestimates the ideal strength in most uniaxial tension and shear cases.

Finite temperature properties

Nickel and Nickel-based alloys are widely used at elevated temperatures, such as in superalloy turbine blades, hence we also focus on the finite temperature properties using DP-Ni in MD simulations. Figure 5 shows the variation of the FCC Ni lattice parameter and elastic constants as compared with experimental measurements48 and simulations with other interatomic potentials from 0 to 1728 K. The DP-Ni lattice parameter is in good agreement with experimental results at high temperatures (above 600 K)48 and the thermal expansion coefficient (slope) is similar to the experimental value. The DP-Ni melting point for Ni is 1635 ± 5 K (Table 1), obtained using the two-phase method49, is ~5.4% lower than the experimental value (1728 K). The discrepancy may be attributed to either the inaccuracy of the DFT in reproducing some experimental measurements or the lack of potential training data for configurations including solid-liquid interfaces. We note that in the training procedure, we terminated training where the errors were in what we considered acceptable bounds (this deviation from the experimental melting point was deemed acceptable). The MEAM_2015 melting point is 164 K (~9.5%) higher than the experiment measurement. Figure 5b–d shows the temperature dependence of the elastic constants Cij from DFT within the quasi-harmonic approximation50 and various potentials. Like the DFT and experimental results50,51, the DP-Ni elastic constants decrease continuously with temperature. Other potentials reveal different trends or profiles as compared with DFT/experiment. The EAM data shows an increase of Cij with temperature below 400 K, followed by a continuous decrease at higher temperatures. This abnormal elastic constant behavior is also observed for MEAM_2021 and qSNAP for C12. On the other hand, the MEAM_2015 elastic constants results show a similar (decreasing) trend as the DFT/experiment results, although the discrepancies in the magnitude can be significant, e.g., the discrepancy is > 15% for C12 for T > 700 K. The present results demonstrate that most potentials are unreliable for predicting finite temperature behavior. This is likely because they were fitted to low temperature (and/or limited finite temperature) data, while the DP method incorporates finite-temperature-like perturbations in the training set. The discrepancies between the finite-temperature DFT and experimental results may be attributed to several factors. These include issues related to the exchange-correlation function50 and approximations employed in extracting finite temperature results from DFT calculations (e.g., the quasi-harmonic approximation).

a lattice parameters and elastic constants (b) C11, (c) C12 and (d) C44. The experimental lattice parameters (T > 200 K) are from ref. 48, while the DFT and experimental data of elastic constants are from refs. 50 and 51, respectively. The DP melting point \({T}_{m}^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\) is indicated by vertical dotted lines (~90 K lower than the experiment - termination of the temperature axis on the plots).

Stacking fault and dislocation core

The generalized stacking fault energy (GSFE) is a useful, surrogate property for predicting the plastic response of the material, i.e., dislocation and twinning properties52. The GSFE represents the variation in the system energy required for the slip of a part of the crystal over the other along particular crystal lattice planes under shear, leading to the formation of stacking faults. The variation of the system energy accompanying the translation/slip along particular directions on a slip plane is referred to as the γ-line53. The maximum energy along the γ-line corresponds to the unstable stacking fault energy (γusf), which represents the barrier for dislocation nucleation at stress concentrations such as crack tips. A metastable point on the γ-line, referred to as γsf, represents a dislocation dissociation energy. The complete two-dimensional plane characterizing all possible slip directions, γ-lines, is the γ-plane or γ-surface53.

Figure 6a, b show the γ-lines along the 〈110〉/2 and 〈112〉/2 directions on the {111} plane (most dense plane in FCC) determined from DFT and several interatomic potentials. The only unstable stacking fault is along the 〈110〉/2-direction with a γusf of 766.6 mJ/m2 at half of the Burger vector b, 〈110〉/2, consistent with previous DFT calculations54. In the 〈112〉/2 slip direction, a stable stacking fault occurs at b/3 (b = 〈112〉/2) while an unstable stacking fault is present at b/6. Although a peak appears at 2b/3 in the γ-line, it is irrelevant because this barrier, 1168.4 mJ/m2, is too high to allow slip. The DFT calculations yield γusf = 280.4 mJ/m2 and γsf = 135.9 mJ/m2. The γsf is in good agreement with experimental results (125 mJ/m2 55,56) and previous DFT values ranging from 110 to 145 mJ/m2 54,57. Figure 6a, b also show the γ-line results from DP-Ni and other interatomic potentials. All potentials reproduce the general shape of the γ-lines from DFT except for MEAM_2015, which shows a minimum value at b/2 along 〈110〉/2 direction. Table 2 lists the calculated γusf and γsf values. DP-Ni reproduces the different stacking fault energies well compared with DFT results, with deviations of only 4.6% for γusf in the 〈110〉/2 slip, 7.6% for γusf and 6.7% for γsf along the 〈112〉/2 slip. (Notably, there is no stacking fault data in the DP-Ni training datasets). In contrast, the MEAM_2021 and qSNAP potentials capture the γusf well in both 〈110〉/2 and 〈112〉/2 directions, but significantly underestimate the γsf, particularly for MEAM_2021 which yields an unphysical negative γsf. While the EAM potential accurately describes the γsf, it overestimates both γusf in 〈110〉/2 and 〈112〉/2 directions. The MEAM_2015 potential fails to accurately describe γusf and γsf. The unrealistic empirical and ML qSNAP potential GSFE results suggest that these potentials will struggle to correctly simulate dislocation nucleation and dislocation dissociation behavior. The minimum energy path is indicated on the DP-Ni {111} γ-surface (Fig. 6c), which exhibits the expected symmetry from geometry. The minimum energy path for dislocation dissociation is expected to follow the green or red dashed arrows (Fig. 6c), indicating that a full dislocation 〈110〉/2 or 〈112〉/2 will dissociate into Schockley partials on the {111} plane — as expected.

γ-lines along the (a) 〈110〉/2 and (b) 〈112〉/2 directions. c γ-surface on the loosest packing {111} planes predicted by DP-Ni. The solid red and green arrows represent the slip path along 〈112〉/2 and 〈110〉/2 directions respectively, and dashed arrows show the corresponding dissociated slip paths. The symbols of + and × represent the positions of stable and unstable stacking faults.

The Shockley partial dislocations are separated by a stable stacking fault58. Accurate modeling of dislocation dissociation and partial dislocation separation is essential for precise modeling of plastic behavior. We simulate this dissociation by inserting a perfect 〈110〉/2 edge and screw dislocation at the center of a 301 × 17 × 85 Å3 (the dislocation line is along the y-direction, while the Burgers vector is in the x-direction) and 15 × 302 × 85 Å3 (dislocation line and Burgers vector parallel the x direction) supercells with periodic boundary conditions in the x- and y-directions, respectively. We then minimize the energy (molecular statics simulation at 0 K) with DP-Ni; the relaxed configurations are shown in Fig. 7. The edge and screw configurations decompose into a pair of Shockley partial dislocations with different separation distances. Differential displacement (DD)59 plots reveal the strain fields around a dislocation by measuring the relative displacement of a pair of nearest neighbor atoms. A partial dislocation consists of three atoms with clockwise or counterclockwise net chirality. In this case, the DD plots in Fig. 7c, d identify the positions of the partial dislocations. The DP-Ni partial dislocation separation distances are dedge = 19.25 Å and dscrew = 11.83 Å. Our result for the edge dislocation separation distance aligns with weak-beam transmission electron microscopy observations, i.e., 26 ± 8 Å55. While dscrew is not easily measured experimentally, our result of 11.83 Å is consistent with the 12.0 Å obtained from the previous DFT calculation60.

a, b Show the atomic configurations of edge and screw dislocations visualized by OVITO96. The common neighbor analysis (CNA) method97 is utilized to distinguish the FCC (blue), HCP (yellow), and other (white) local atom stacking. The dislocation extraction algorithm (DXA)98 is employed to identify dislocations precisely. c, d Show the corresponding differential displacement plots for (a) and (b). The partial core separations are shown to be dedge and dscrew of 19.25 Å and 11.83 Å.

Structures and energies of tilt grain boundaries

Grain boundaries (GB) in polycrystalline materials limit dislocation slip and, hence, play an important role in determining strength and ductility. In this study, we investigate several high angle symmetric tilt GBs, constructed based upon geometry. We then identify the lowest energy GB structure by sliding one grain relative to the other and minimizing the energy. The lowest-energy GB configurations (after relaxation using DP-Ni) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The relaxed \(\Sigma 3\,[1\bar{1}0](111)\), \(\Sigma 5\,[100](0\bar{2}1)\) and \(\Sigma 11\,[1\bar{1}0](113)\) remain symmetric, while \(\Sigma 3\,[1\bar{1}0](112)\), \(\Sigma 7\,[\bar{1}\bar{1}\bar{1}](3\bar{2}\bar{1})\) and \(\Sigma 9\,[\bar{1}10](22\bar{1})\) relax to an asymmetric boundary structure. Table 2 shows the GB energies from both DFT calculations and with several interatomic potentials. DP-Ni accurately reproduces all GB energies with only minor discrepancies (< 6.7%) compared to the respective DFT values. Both DP-Ni and DFT identify \(\Sigma 3\,[1\bar{1}0](111)\) as the lowest GB energy, as reported in most experimental observations61. The energy ordering follows the pattern: Σ3 (111) < Σ11 < Σ3 (112) < Σ9 < Σ7 < Σ5. Other potentials capture the energy ordering of these GBs but are less quantitative relative to the DFT results. EAM accurately predicts the energy of \(\Sigma 3\,[1\bar{1}0](111)\), but overestimates other GB energies by 16.9–22.1%. MEAM_2021, MEAM_2015 and qSNAP roughly reproduce the energy of low Σ GBs but drastically underestimate the energy of the important \(\Sigma 3\,[1\bar{1}0](111)\) (by > 50%)—in fact the MEAM_2021 gives an unphysical negative value for this GB energy. Overall, DP-Ni reproduces all GB structures and corresponding energies, demonstrating its potential for simulation of GB behavior (e.g., GB migration, deformation twinning, and disconnection behavior62,63,64).

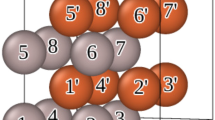

Allotropic transformation of nickel under uniaxial tension

As a further, stringent test, on the performance of DP-Ni, we examine the allotropic phase transformation of nickel under uniaxial loading. Figure 8 shows the stress-strain relationship for Ni under uniaxial tension along the [001] crystallographic direction; calculations are conducted at 0 K. The results show a monotonic increase in stress as a function of strain, followed by a sudden drop at a strain of ~0.226. The inset atomic configuration depicts the observed atomic structure at different strains, showing the strained FCC and HCP structures. These insets indicate that the abrupt drop in the stress corresponds to an FCC → HCP transformation. Subsequently, the HCP phase remains stable for an additional strain of at least 15% (from point B). The transformation strain is quite large compared with other strain-induced transformations65,66,67,68,69. However, such large transformation strains are not unusual for FCC metals; e.g., see the experimental observations and theoretical calculations70,71,72,73,74,75,76.

The red square points are the stress calculated by DFT under the corresponding strain. Allotropic phase transformation is induced upon a precipitous decrease in stress. The energy difference values represent the cumulative energy discrepancy of structures at points A and B as computed by the DP-Ni and DFT, respectively. The insert atomic configurations are labeled using CNA97 for FCC (blue) and HCP (yellow) local packing by OVITO96. The crystallographic orientation relationship for FCC-HCP is {100}FCC∥{0001}HCP and \(\left\langle 010\right\rangle\)FCC\(\parallel \left\langle 11\bar{2}0\right\rangle\)HCP.

Specifically, in the case of nickel, an FCC → HCP transformation was observed experimentally in nanocrystalline (nanoscale grained) Ni subjected to large plastic strains2,3. To confirm this transformation, the energy differences (ΔE) between structures at points A and B are measured, as shown in Fig. 8. The positive ΔE obtained from both the DP-Ni and DFT calculations suggest that the HCP structure at point B is more stable compared to the strained FCC structures at point A. We apply DFT to calculate the stress of the structures in the strain–stress curve from DP-Ni. As indicated by the red squares in Fig. 8, the results from DP-Ni are very close to those from DFT. At the allotropic transformation strain, the energy difference between ΔEDP and ΔEDFT, is very small (~10 meV/atom), corroborating the fidelity of the DP-Ni model. The observed crystallographic orientation relationship between FCC and HCP structures in our study presents an atypical case, namely, {100}FCC∥{0001}HCP and \(\left\langle 010\right\rangle\)FCC\(\parallel \left\langle 11\bar{2}0\right\rangle\)HCP. This orientation deviates from the commonly documented strain-induced FCC → HCP transformation, which is typified by the orientation relation {111}FCC∥{0001}HCP and \(\left\langle 1\bar{1}0\right\rangle\)FCC\(\parallel \left\langle 11\bar{2}0\right\rangle\)HCP4,70,77,78. The present orientation relationship is associated with the very large mechanical strains here. This orientation relationship was previously reported based upon theoretical71,79 and experimental investigations80 in other FCC metals. Interestingly, another unconventional orientation relation was observed in nanocrystalline nickel \(\left\langle 110\right\rangle\)FCC\(\parallel \left\langle 1\bar{2}1\bar{3}\right\rangle\)HCP2.

Conclusions

We developed a “magnetism-hidden” machine learning Deep Potential (DP) model for both FCC and HCP nickel, based upon DFT calculations. The nickel DP (DP-Ni) was trained using spin-polarized DFT calculations employing a relatively small training dataset (see Supplementary Table 2). Inclusion of spin polarization was found to be essential. DP-Ni achieves DFT-level accuracy in predicting a wide range of properties for both FCC and HCP Ni, such as (finite-temperature) lattice parameters and elastic constants, phonon spectra, cohesive and decohesion energies/stresses, point defect formation energies, stacking fault energies, and dislocation and grain boundary properties. The DP-Ni results are, overall, more reliable than predictions based upon other potentials (including semi-empirical and other machine learning potentials). DP-Ni thus serves as a promising tool for large-scale atomistic simulations of Ni, especially for mechanical properties. Our DP-Ni model facilitated the examination of the allotropic FCC → HCP phase transition, wherein we identified a high critical strain and an atypical orientation relationship under uniaxial tensile loading. The new DP-Ni potential and the associated training datasets can be utilized as a foundation for developing ML potential for Ni-based superalloys, medium-entropy (FeCoNi) and high-entropy (FeCoNi-based) alloys through methods such as the DP attention pre-training model81.

Methods

DFT calculations

The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)82,83 is used to perform the density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method84 for generation of the training set and determining property benchmarks. The exchange-correlation function is treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), as formulated by Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)85. The basis set includes Ni 3d84s2 electron levels. We employ a plane wave cutoff energy of 600 eV and the Methfessel-Paxton method86 to determine partial wave function occupations with a 0.12 eV smearing width. Monkhorst-Pack k-point grids87 are optimized to sample the Brillouin zone with a 0.1 Å−1 k-points grid. A 10−6 eV/atom total energy and a 10−3 eV/Å ionic force convergence criteria is employed. Both the ground state calculations and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations account for spin-polarization (magnetic moment). More details may be found in Supplementary Note 1.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) and static calculations are conducted using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)88. Atomic structure optimization is performed using the conjugate gradient method; convergence criteria for force is 10−10 eV/Å (self-interstitial configurations are converged to energy 10−13). The same simulation cell size/configurations are employed in both DFT and MD calculations of the elastic constants, surface energy, point-defect formation energy, grain boundary, stacking fault energy, cohesive and decohesive energies, phonon spectra, and ideal strength. See the Supplementary Note 2 for more details.

Training strategy of deep potential for Ni

We utilize the general Deep Potential Generator (DP-GEN) scheme32, the DeepPot-SE35, along with the “specialization” strategy24 to generate the training datasets (a 6 Å cutoff radius is used throughout). We employ a neural network of 240 × 240 × 240.

Initially, supercells with three perfect 2 × 2 × 2 cell BCC, FCC, and HCP (2, 4, and 2 atoms per cell) are constructed. Supercell volumes are rescaled by a scaling factor (0.96–1.06 in steps of 0.02), resulting in six configurations for each phase. These scaled supercells are then randomly perturbed (3X) by scaling the supercell translation vectors and adding relative atomic translation in the range of −3 to 3% and −0.01 to 0.01 Å, respectively. Next, two steps of AIMD are conducted for each distorted structure (at 100 K) in the NVT ensemble (Nosé-Hoover thermostat). A total of 108 ionic configurations are obtained from the AIMD calculations (converged electronic degrees of freedom), providing atom coordinates, total energy, atomic forces, and virial tensors. This data serves as the initial training dataset for the DP-GEN loop.

In each DP-GEN training step, four DP models are initiated using four random initial neural net parameter sets. The training step consists of 400,000 epochs. The learning rate starts at 10−3 and exponentially decays to 5 × 10−8 during the training. The loss function prefactors for the energy, atomic force, and virial tensor \({p}_{{{\rm{e}}}}^{{{\rm{start}}}}\) = 0.02, \({p}_{{{\rm{e}}}}^{{{\rm{limit}}}}\) = 2, \({p}_{{{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{start}}}}\) = 1000, \({p}_{{{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{limit}}}}\) = 1, \({p}_{{{\rm{v}}}}^{{{\rm{start}}}}\) = 0, and \({p}_{{{\rm{v}}}}^{{{\rm{limit}}}}\) = 0, respectively, vary during training.

During the DP-GEN loop exploration step, a single DP model is selected to explore various bulk and surface structures for each of the distorted BCC, FCC, and HCP supercells using DPMD with the LAMMPS package. The bulk structure is explored via MD in the temperature range of 50–3283.2 K (1.9 times the Ni melting point Tmelt) under isothermal-isobaric (NPT) conditions, with pressures varying between 0.001 and 50 kBar. Surface structures are constructed from all crystal supercells by introducing {100}, {110}, and {111} (BCC and FCC) and {0001} and \(\{10\bar{1}0\}\) (HCP) surfaces. Surface supercells are scaled and perturbed similarly to the bulk structures and simulated via DPMD in a canonical (NVT) ensemble over the same temperature range. A criterion is set for choosing amongst the four models at each DPMD step to perform spin-polarized DFT calculations (energy, force, virial) to add to the training datasets for subsequent DP-GEN loop iterations. See Supplementary Note 3 for more details.

While the final four DP models reproduce many properties of FCC and HCP Ni, they do not accurately reproduce cohesive properties (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3b). We address this by generating a specialized training dataset consisting of 170 configurations specifically selected from the cohesive energy line. These configurations include 17 distinct structures; each assigned a weight of 10 in the final training set (i.e., 10X the other structures). The final training is performed on both the training datasets from DP-GEN and the “specialization” (DFT calculations are all spin-polarized). More details are provided in Supplementary Note 3 (see Supplementary Table 2 for a summary of training datasets employed). We emphasize that while our training set is large, it is considerably smaller than those employed in other ML potentials24,89,90.

Data availability

The DP-Ni model and training datasets have been uploaded to the online open data repository https://www.aissquare.com/datasets.

Code availability

The DP-Ni model was generated by the DP-GEN scheme32. The codes supporting the properties calculations and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ovid’ko, I., Valiev, R. & Zhu, Y. Review on superior strength and enhanced ductility of metallic nanomaterials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 94, 462–540 (2018).

Luo, Z. et al. Plastic deformation induced hexagonal-close-packed nickel nano-grains. Scr. Mater. 168, 67–70 (2019).

Guo, X., Luo, Z., Li, X. & Lu, K. Plastic deformation induced extremely fine nano-grains in nickel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 802, 140664 (2021).

Pattamatta, A. S. & Srolovitz, D. J. Allotropy in ultra high strength materials. Nat. Commun. 13, 3326 (2022).

Dimiduk, D., Uchic, M. & Parthasarathy, T. Size-affected single-slip behavior of pure nickel microcrystals. Acta Mater. 53, 4065–4077 (2005).

Haasen, P. Plastic deformation of nickel single crystals at low temperatures. Philos. Mag. J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 3, 384–418 (1958).

Wu, X. L. & Zhu, Y. T. Partial-dislocation-mediated processes in nanocrystalline Ni with nonequilibrium grain boundaries. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 031922 (2006).

Tian, W. et al. Hexagonal close-packed Ni nanostructures grown on the (001) surface of MgO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 131915 (2005).

Higuchi, J., Ohtake, M., Sato, Y., Nishiyama, T. & Futamoto, M. Preparation and structural characterization of hcp and fcc Ni epitaxial thin films on Ru underlayers with different orientations. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 063001 (2011).

Černý, M., Pokluda, J., Šob, M., Friák, M. & Šandera, P. Ab initio calculations of elastic and magnetic properties of Fe, Co, Ni, and Cr crystals under isotropic deformation. Phys. Rev. B 67, 035116 (2003).

Zelený, M., Legut, D. & Šob, M. Ab initio study of Co and Ni under uniaxial and biaxial loading and in epitaxial overlayers. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224105 (2008).

Hargather, C. Z., Shang, S.-L., Liu, Z.-K. & Du, Y. A first-principles study of self-diffusion coefficients of fcc Ni. Comput. Mater. Sci. 86, 17–23 (2014).

Megchiche, E. H., Pérusin, S., Barthelat, J.-C. & Mijoule, C. Density functional calculations of the formation and migration enthalpies of monovacancies in Ni: comparison of local and nonlocal approaches. Phys. Rev. B 74, 064111 (2006).

Mizuno, T., Asato, M., Hoshino, T. & Kawakami, K. First-principles calculations for vacancy formation energies in Ni and Fe: non-local effect beyond the LSDA and magnetism. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 226-230, 386–387 (2001).

Gong, Y. et al. Temperature dependence of the Gibbs energy of vacancy formation of fcc Ni. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214106 (2018).

Guo, G. & Wang, H. Gradient-corrected density functional calculation of elastic constants of Fe, Co and Ni in bcc, fcc and hcp structures. Chin. J. Phys. 38, 949–961 (2000).

Chandran, M. & Sondhi, S. K. First-principle calculation of stacking fault energies in Ni and Ni-Co alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 103525 (2011).

Kumar, K., Sankarasubramanian, R. & Waghmare, U. V. Influence of dilute solute substitutions in Ni on its generalized stacking fault energies and ductility. Comput. Mater. Sci. 150, 424–431 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Temperature dependence of the stacking-fault Gibbs energy for Al, Cu, and Ni. Phys. Rev. B 98, 224106 (2018).

Brandl, C., Derlet, P. M. & Van Swygenhoven, H. General-stacking-fault energies in highly strained metallic environments: ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 76, 054124 (2007).

Kim, D., Shang, S.-L. & Liu, Z.-K. Effects of alloying elements on elastic properties of Ni by first-principles calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 47, 254–260 (2009).

Interatomic potentials repository: https://www.ctcms.nist.gov/potentials/system/Ni/.

Open knowledgebase of interatomic models: https://openkim.org/browse/models/by-species?species-search=Ni.

Wen, T. et al. Specialising neural network potentials for accurate properties and application to the mechanical response of titanium. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 206 (2021).

Zuo, Y. et al. Performance and cost assessment of machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 731–745 (2020).

Li, X.-G. et al. Quantum-accurate spectral neighbor analysis potential models for Ni-Mo binary alloys and fcc metals. Phys. Rev. B 98, 094104 (2018).

Dragoni, D., Daff, T. D., Csányi, G. & Marzari, N. Achieving DFT accuracy with a machine-learning interatomic potential: thermomechanics and defects in bcc ferromagnetic iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013808 (2018).

Jana, R. & Caro, M. A. Searching for iron nanoparticles with a general-purpose Gaussian approximation potential. Phys. Rev. B 107, 245421 (2023).

Byggmästar, J. et al. Multiscale machine-learning interatomic potentials for ferromagnetic and liquid iron. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 305402 (2022).

Zhang, L., Csányi, G., Van Der Giessen, E. & Maresca, F. Atomistic fracture in bcc iron revealed by active learning of Gaussian approximation potential. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 217 (2023).

Mori, H. & Ozaki, T. Neural network atomic potential to investigate the dislocation dynamics in bcc iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 040601 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. DP-GEN: a concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Wen, T., Zhang, L., Wang, H., E, W. & Srolovitz, D. J. Deep potentials for materials science. Mater. Futures 1, 022601 (2022).

Pitike, K. C. & Setyawan, W. Accurate Fe-He machine learning potential for studying He effects in BCC-Fe. J. Nucl. Mater. 574, 154183 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. End-to-end symmetry preserving inter-atomic potential energy model for finite and extended systems. In Bengio, S.et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Mishin, Y., Farkas, D., Mehl, M. J. & Papaconstantopoulos, D. A. Interatomic potentials for monoatomic metals from experimental data and ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 59, 3393–3407 (1999).

Vita, J. A. & Trinkle, D. R. Exploring the necessary complexity of interatomic potentials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 200, 110752 (2021).

Ko, W.-S., Grabowski, B. & Neugebauer, J. Development and application of a Ni-Ti interatomic potential with high predictive accuracy of the martensitic phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134107 (2015).

Mouhat, F. & Coudert, F.-X. Necessary and sufficient elastic stability conditions in various crystal systems. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224104 (2014).

Grimvall, G., Magyari-Köpe, B., Ozoliņš, V. & Persson, K. A. Lattice instabilities in metallic elements. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 945 (2012).

Birgeneau, R., Cordes, J., Dolling, G. & Woods, A. D. B. Normal modes of vibration in nickel. Phys. Rev. 136, A1359 (1964).

Tran, R. et al. Surface energies of elemental crystals. Sci. Data 3, 1–13 (2016).

Tyson, W. & Miller, W. Surface free energies of solid metals: Estimation from liquid surface tension measurements. Surf. Sci. 62, 267–276 (1977).

Toijer, E. et al. Solute-point defect interactions, coupled diffusion, and radiation-induced segregation in fcc nickel. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 013602 (2021).

Tucker, J., Allen, T., Najafabadi, R., Allen, T. & Morgan, D. Determination of solute-interstitial interactions in Ni-Cr by first principle. In Proc. International Conference on Mathematics, Computational Methods & Reactor Physics (M & C), 2, 891 (American Nuclear Society, 2009).

Ma, P.-W. & Dudarev, S. Nonuniversal structure of point defects in face-centered cubic metals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 013601 (2021).

Jhi, S.-H., Louie, S. G., Cohen, M. L. & Morris Jr, J. Mechanical instability and ideal shear strength of transition metal carbides and nitrides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 075503 (2001).

Suh, I.-K., Ohta, H. & Waseda, Y. High-temperature thermal expansion of six metallic elements measured by dilatation method and X-ray diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 23, 757–760 (1988).

Morris, J. R., Wang, C. Z., Ho, K. M. & Chan, C. T. Melting line of aluminum from simulations of coexisting phases. Phys. Rev. B 49, 3109–3115 (1994).

Hachet, G., Metsue, A., Oudriss, A. & Feaugas, X. Influence of hydrogen on the elastic properties of nickel single crystal: a numerical and experimental investigation. Acta Mater. 148, 280–288 (2018).

Alers, G., Neighbours, J. & Sato, H. Temperature dependent magnetic contributions to the high field elastic constants of nickel and an Fe-Ni alloy. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 13, 40–55 (1960).

Xiao, J. et al. Unveiling deformation twin nucleation and growth mechanisms in BCC transition metals and alloys. Mater. Today 65, 90–99 (2023).

Christian, J. W. & Vítek, V. Dislocations and stacking faults. Rep. Prog. Phys. 33, 307 (1970).

Su, Y., Xu, S. & Beyerlein, I. J. Density functional theory calculations of generalized stacking fault energy surfaces for eight face-centered cubic transition metals. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 105112 (2019).

Carter, C. B. & Holmes, S. M. The stacking-fault energy of nickel. Philos. Mag. J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 35, 1161–1172 (1977).

Murr, L. E. Interfacial Phenomena in Metals and Alloys (Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1975).

Rodney, D., Ventelon, L., Clouet, E., Pizzagalli, L. & Willaime, F. Ab initio modeling of dislocation core properties in metals and semiconductors. Acta. Mater. 124, 633–659 (2017).

Anderson, P. M., Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J. Theory of Dislocations (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Vítek, V., Perrin, R. C. & Bowen, D. K. The core structure of 1/2(111) screw dislocations in b.c.c. crystals. Philos. Mag. J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 21, 1049–1073 (1970).

Tan, A. M. Z., Woodward, C. & Trinkle, D. R. Dislocation core structures in Ni-based superalloys computed using a density functional theory based flexible boundary condition approach. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 033609 (2019).

Randle, V. & Owen, G. Mechanisms of grain boundary engineering. Acta. Mater. 54, 1777–1783 (2006).

Zhu, Q. et al. In situ atomistic observation of disconnection-mediated grain boundary migration. Nat. Commun. 10, 156 (2019).

Khater, H., Serra, A., Pond, R. & Hirth, J. The disconnection mechanism of coupled migration and shear at grain boundaries. Acta Mater. 60, 2007–2020 (2012).

Lu, N., Du, K., Lu, L. & Ye, H. Transition of dislocation nucleation induced by local stress concentration in nanotwinned copper. Nat. Commun. 6, 7648 (2015).

Chen, P., Wang, F. & Li, B. Transitory phase transformations during \(\{10\bar{1}2\}\) twinning in titanium. Acta. Mater. 171, 65–78 (2019).

Guan, X. et al. High-strain-rate deformation: stress-induced phase transformation and nanostructures in a titanium alloy. Int. J. Plast. 169, 103707 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Chemical ordering effects on martensitic transformations in Mg-Sc alloys. Acta. Mater. 249, 118854 (2023).

Yang, X.-S., Sun, S., Ruan, H.-H., Shi, S.-Q. & Zhang, T.-Y. Shear and shuffling accomplishing polymorphic fcc γ → hcp ε → bct α martensitic phase transformation. Acta. Mater. 136, 347–354 (2017).

Hirth, J., Hoagland, R., Holian, B. & Germann, T. Shock relaxation by a strain induced martensitic phase transformation. Acta. Mater. 47, 2409–2415 (1999).

Sun, S. et al. Direct atomic-scale observation of ultrasmall Ag nanowires that exhibit fcc, bcc, and hcp structures under bending. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 015701 (2022).

Xie, H., Yin, F., Yu, T., Lu, G. & Zhang, Y. A new strain-rate-induced deformation mechanism of Cu nanowire: transition from dislocation nucleation to phase transformation. Acta. Mater. 85, 191–198 (2015).

Wei, S. et al. Plastic strain-induced sequential martensitic transformation. Scr. Mater. 185, 36–41 (2020).

Zhang, H., Huang, X. & Hansen, N. Evolution of microstructural parameters and flow stresses toward limits in nickel deformed to ultra-high strains. Acta. Mater. 56, 5451–5465 (2008).

Krygier, A. et al. Extreme hardening of Pb at high pressure and strain rate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 205701 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Nanotwin assisted reversible formation of low angle grain boundary upon reciprocating shear load. Acta. Mater. 230, 117850 (2022).

Diao, J., Gall, K. & Dunn, M. L. Surface-stress-induced phase transformation in metal nanowires. Nat. Mater. 2, 656–660 (2003).

Wu, T., Sun, M., Wong, H. H. & Huang, B. Decoding of crystal synthesis of fcc-hcp reversible transition for metals: theoretical mechanistic study from facet control to phase transition engineering. Nano Energy 85, 106026 (2021).

Yu, Q. et al. In situ TEM observation of FCC Ti formation at elevated temperatures. Scr. Mater. 140, 9–12 (2017).

Wentzcovitch, R. M. & Lam, P. K. fcc-to-hcp transformation: a first-principles investigation. Phys. Rev. B 44, 9155–9158 (1991).

Bai, F. et al. Study on phase transformation orientation relationship of hcp-fcc during rolling of high purity titanium. Crystals 11, 1164 (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. Pretraining of attention-based deep learning potential model for molecular simulation. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 94 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616 (1989).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Byggmästar, J., Nordlund, K. & Djurabekova, F. Gaussian approximation potentials for body-centered-cubic transition metals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 093802 (2020).

Smith, J. S. et al. Automated discovery of a robust interatomic potential for aluminum. Nat. Commun. 12, 1257 (2021).

Kanhe, N. S. et al. Investigation of structural and magnetic properties of thermal plasma-synthesized Fe1−xNix alloy nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd. 663, 30–40 (2016).

Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2005).

Simmons, G. & Wang, H. Single Crystal Elastic Constants and Calculated Aggregate Properties: a Handbook. (The MIT Press, 1971).

Dinsdale, A. SGTE data for pure elements. Calphad 15, 317–425 (1991).

LaGrow, A. P. et al. Can polymorphism be used to form branched metal nanostructures? Adv. Mater. 25, 1552–1556 (2013).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Honeycutt, J. D. & Andersen, H. C. Molecular dynamics study of melting and freezing of small Lennard-Jones clusters. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 4950–4963 (1987).

Stukowski, A. & Albe, K. Extracting dislocations and non-dislocation crystal defects from atomistic simulation data. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 085001 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR through the General Research Fund (17210723). T.W. acknowledges additional support by The University of Hong Kong (HKU) via seed funds (2201100392, 2309100163). A.S.L.S.P. acknowledges additional support by HKU via seed fund (2201101034). Part of the computational resources are provided by HKU research computing facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G., Z.L., A.S.L.S.P., T.W. performed the research and analyzed the data. T.W. and D.J.S. conceived and directed the project. X.G., Z.L., A.S.L.S.P., T.W., and D.J.S. wrote, discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, X., Li, Z., Pattamatta, A.S.L.S. et al. An accurate and transferable machine learning interatomic potential for nickel. Commun Mater 5, 157 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00603-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00603-3

This article is cited by

-

Early stages of self-healing at tungsten grain boundaries from ab initio machine learning simulations

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Predicting hydrogen diffusion in nickel–manganese random alloys using machine learning interatomic potentials

Communications Materials (2025)