Abstract

Iron-based superconductors exhibit various magnetic and electronic phases that are highly sensitive to structural and chemical modifications. Elucidating the origins of these phases remains a central challenge. Here, using neutron and x-ray diffraction, we uncover a universal phase diagram that identifies disorder as a hidden tuning parameter governing these phase transitions. By analyzing nine hole-doped phase diagrams, we observe the emergence of a double-Q tetragonal magnetic phase in proximity to ideal FeAs4 tetrahedral configurations, thereby demonstrating a strong link between bond-angle stabilization and magnetic transitions. Beyond stabilizing the double-Q phase, atomic disorder also influences charge doping and magnetic anisotropy. We further observe similar scaling behavior of the transition temperatures of the double-Q and the more prevalent orthorhombic single-Q magnetic phases, evidencing a unified origin of structural and magnetic properties linked to itinerant nesting instability. Our findings establish a comprehensive basis for understanding how chemical disorder, charge doping, and structural features collectively shape the magnetic and superconducting properties of iron-based superconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following the 2006 discovery of superconductivity in iron-based pnictides1, these materials garnered considerable attention due to their rich array of physical phenomena2,3,4,5,6,7,8, including the realization of unconventional superconductivity9,10, spin-density waves (SDW or \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) where the subscript and superscript denote the two-fold symmetry of the magnetic phase and the direction of the magnetic moments, respectively)2,11,12,13, charge-spin density waves (CSDW or \({C}_{4M}^{c}\))14,15, spin vortex crystal (SVC or \({C}_{4M}^{{ab}}\))15,16,17 and quantum criticality (QC)18,19,20,21. The discovery of a structurally re-entrant tetragonal magnetic phase, \({C}_{4M}^{c}\)5,22, and the determination of its double-Q magnetic structure23, have driven extensive theoretical24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 and experimental investigations. This breakthrough resolved a long-standing debate over whether magnetic fluctuations, rather than orbital or nematic fluctuations, are responsible for simultaneous first-order structural and magnetic transitions, highlighting the universal significance of these tetragonal states.

The \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase has been observed in several hole-doped AFe2As2 systems (“122” where A = Ba1−xNax, Ba1−xKx, Sr1−xNax, or Ca1−xNax), where it arises from a first-order in-plane to out-of-plane spin reorientation22,34, occurring within a narrow range of Na substitution. This phase resides within a limited dome in the orthorhombic \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) regime35, where magnetic and superconducting states coexist microscopically6,36,37. Prior studies on the isovalently-substituted LaFeAs1−xPxO (“1111” system)38 revealed the sequential occurrence of \({C}_{4M}^{{ab}}\) and \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phases outside the \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) magnetic phase space, underscoring the potential shared mechanisms between these tetragonal states across different pnictide systems.

Further studies have demonstrated5,35,39 that in the “122” systems, the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase occurs over a range of Na content (equivalent to hole doping), with the re-entrant maximal transition temperature, Tr max, rising from ≈48 K to 68 K before declining back to ≈52 K for the Ba1−xNaxFe2As2 (BNFA), Sr1−xNaxFe2As2 (SNFA), and Ca1−xNaxFe2As2 (CNFA) solid solution systems, respectively. This trend mirrors the antiferromagnetic transition temperature, TN, of the primary \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) phase, illustrating how A-site ionic size variance influence the electronic properties of the materials. The flexible extent of the \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) phase space and the concurrent shifts of \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) and superconducting domes reinforce the idea of a shared underlying mechanism between these phases. However, key structural factors governing magnetic anisotropy and long-range magnetic order remain unresolved, despite theoretical studies40 linking doping and TN to changes in magnetic order parameters.

The stability of the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase has been tied to optimal nesting conditions driven by spin-orbit coupling and quantum fluctuations near magnetic quantum criticality41,42. The experimentally confirmed presence of a quantum critical point (QCP) in several “122” systems, where SDW \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) magnetic order is suppressed and superconductivity emerges [see references16,18,19,20,21,43,44,45, for example], suggests a strong coupling between the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase, superconductivity, and quantum criticality within the magnetic-superconducting coexistence region. These findings deepen our understanding of precursor states leading to superconductivity, but important questions remain about the universality, stability, and competitive nature of the \({C}_{2M}^{a}\), \({C}_{4M}^{{ab}}\) and \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phases.

In this study, we address these unresolved questions by exploiting the structural flexibility of the pnictides and investigating the behavior of the \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) and \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) magnetic states in engineered hole-doped “122” compounds through Na-substituted solid solutions. These materials introduce controlled structural disorder, charge doping, and chemical pressure. A scaling relationship between magnetic and nuclear structures was established in samples with optimal conditions for maximum \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) transition temperatures, leading to the derivation of an empirical equation that describe the experimental behavior of TN and Tr. Our findings highlight structural disorder as a hidden scaling parameter, culminating in a universal phase diagram that captures the intricate details of “122”-hole-doped materials.

Results

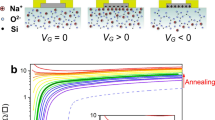

In addition to the previously studied Ba1−xNaxFe2As2 (BNFA), Sr1−xNaxFe2As2 (SNFA) and Ca1−xNaxFe2As2 (CNFA) series5,35,36,39, six previously-unreported partial phase diagrams with the general formula [(Ba1−ySry)1−xNax]Fe2As2 (BSNFA) and [(Sr1−yCay)1−xNax]Fe2As2 (SCNFA) were synthesized. Numerous samples, covering a relatively broad range of Na substitution levels (x = 0.25–0.45), were prepared to explore the potential occurrence of the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase, as previously observed in the parent systems. The ratios of isovalent Ba1−ySry and Sr1−yCay mixtures were fixed at 3:1, 1:1 and 1:3 in BSNFA and SCNFA to manipulate the A-site ionic radius and introduce disorder without altering the charge doping, which was solely controlled by sodium substitution. These constraints are reflected in the ternary phase diagram in Fig. 1, where the term ternary refers to the triply occupied A-site. The synthesis procedures followed the methods described in earlier studies5,35,36,39.

Ternary phase diagrams illustrating the doubly-substituted (Ba1−ySry)1−xNax and (Sr1−yCay)1−xNax samples selected for this study (indicated by crosses). Blue and red symbols represent the \({C}_{2M}^{{a}}\) and \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phases, respectively. \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) samples are depicted by the white-highlighted dark-red spheres. Partially filled red and blue symbols denote samples that exhibit partial \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase characteristics. The color map highlights the approximate regions of the \({C}_{2M}^{{a}}\) (dark yellow), \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) (green), and superconducting (pink) phases. The narrow, dark pink bands flanking the green region indicate overlapping \({C}_{2M}^{{a}}\) and superconducting phases. The sodium content of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) samples ranges from 0.27 for the Ba1−xNax series to 0.44 in the Ca1−xNax series. Error bars are smaller than the symbol size.

Compositions exhibiting the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase were identified within the \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) region of each of the nine investigated series, with transition temperatures (Tr) ranging from 38 K to 68 K, below the Néel temperature (TN). These compositions are situated near the onset of superconductivity and optimal nesting conditions41,42, suggesting that samples with the highest Tr values, \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\), exhibit similar free energies regardless of their Na content. This observation led to the formation of a subset of 13 compositions, referred to as the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) series, with comparable electronic properties, which follows Vegard’s law, as shown in the insets of Fig. 2 (data shown at 10 K).

Lattice parameters (a, b) and unit cell volume (c), at 10 K, of all samples as a function of average A-site ionic radius \({r}_{ < A > }\). Inset: Lattice parameters, unit cell volume, and select bond lengths for samples exhibiting maximum transition temperatures to the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) magnetic state. Orthorhombic a and b lattice parameters were transformed to tetragonal-equivalent lattice parameter atet using the relationship: \({a}_{{tet}}=\scriptstyle\sqrt{\left({a}^{2}+{b}^{2}\right)}/2\). Error bars are smaller than the symbol size.

Despite the occurrence of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) at different Na values, this subset of samples exhibits a linear dependence of key structural variables, including unit cell volume, lattice parameters, As-As and A-As bond-lengths, on the average ionic radius \({r}_{ < A > }\) as displayed in Figs. 2 and 3. However, the Fe-As bond-length, dFe−As, remains initially unchanged for \({r}_{ < A > }\) > 1.22 Å, consistent with the stiff structural properties reported for similar Fe-based pnictides36,46,47,48,49. For compositions with \({r}_{ < A > }\) values below 1.22 Å (Fig. 3a), this bond length decreases by ≈0.8%, signaling a transition in structural rigidity at this threshold.

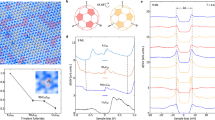

Bond-length (a), bond-angles (b), and refined magnetic moment (d) for all the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) samples at 10 K. Linear scaling between \(\frac{{T}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}}{\sqrt{M}}\) and \(\frac{{T}_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}}{\sqrt{M}}\) and \({r}_{ < A > }\) (c) and between the bond-angles and bond-length and \({r}_{ < A > }\) (f). e Magnetic and superconducting transition temperatures. Observed (closed symbols) values of TN and Tr are compared with those calculated by the scaling function (Eq. 1) (open symbols). Error bars are smaller than the symbol size, if not clearly visible.

This change in the Fe-As bond length is further reflected in the behavior of other structural parameters. The linear contraction of the out-of-plane As-As bond length with decreasing \({r}_{ < A > }\) results in a much larger compression of the c-axis (|Δc|≈ 1.15 Ǻ or ≈8.9%), compared to a smaller contraction of the a-axis (|Δa| ≈ 0.05 Ǻ or ≈1.3%), as shown in the inset of Fig. 2a, b. The tetrahedral As-Fe-As bond angles (α and β in Fig. 3b) are also significantly affected by these structural changes, particularly the displacement of As ions and the shortening of the As-As bond length by up to 0.6 Å. Initially, α and β vary in opposite directions with decreasing \({r}_{ < A > }\), achieving a perfect tetrahedral angle of 109.47° at \({r}_{ < A > }\) ≈ 1.32 Å. However, below \({r}_{ < A > }\,\)≈ 1.22 Å, the two angles diverge again and stabilize, remaining statistically unchanged down to the lowest \({r}_{ < A > }\) value.

An analysis of the As-Fe-As bond angles at 10 K across all samples reveals a universal trend with the samples that exhibit the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) phase clustering within a confined region, marked by a tetrahedral angular separation of less than one degree (see the shaded rectangular box in Fig. 4a). This finding suggests a strong correlation between nearly perfect tetrahedral angles and the occurrence of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) state, particularly in regions of optimal nesting. This correlation may explain the absence of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) magnetic phase in the electron-doped “122” analogs, where the angles deviate significantly from the ideal tetrahedral value.

a As-Fe-As bond angles (α and β) highlighting the region where samples exhibiting the \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phase cluster (shaded rectangular box), with angles approaching those of a perfect tetrahedron. Symbols without edges represent α angles, while β angles are shown with thick, black-edged symbols of the same color. Upward triangles (magenta, green and olive green) denote the BNFA, SNFA and CNFA series, respectively. Rightward triangles (light green, dark yellow, dark cyan) represent the BNSFA 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 series, and leftward triangles (blue, cyan, and orange) represent the SCNFA 3:1, 1:1 and 1:3 series. Bold red and blue spheres correspond to the α and β angles of samples exhibiting \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) properties. b A universal phase diagram with normalized x and y axes (see text and methods for details), combining data from all nine BNFA, SNFA, CNFA, BSNFA, and SCNFA series. Dark blue, olive green (and white with olive green edges), and red symbols represent normalized TN, Tr and TC values, respectively. The yellow, pink, dark yellow and green regions correspond to the non-magnetic tetragonal I4/mmm (C4), superconducting tetragonal I4/mmm (S-C4), magnetic orthorhombic Fmmm \({C}_{2M}^{a}\), and magnetic tetragonal I4/mmm \({C}_{4M}^{c}\) phases, respectively. Unscaled phase diagram shown in the inset of (b). Error bars are smaller than the symbol size.

Building on these structural correlations, a general phase diagram was constructed by normalizing the sodium content of each sample to that of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) sample of the corresponding series (more details in Methods). This normalization allowed the magnetic and superconducting properties of all samples to collapse into a universal phase diagram, shown in Fig. 4b. The transition temperatures (TN, Tr and TC) are scaled relative to TN of the x(Na) = 0 sample in each series. Here, TN (x(Na) = 0), extracted from ref. 50, represents the antiferromagnetic transition temperature of the undoped parent material.

Additionally, the refined magnetic moments of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) samples, along with their magnetic and superconducting transition temperatures, are illustrated in Fig. 3d, e, respectively. Both TN and Tr peak around \({r}_{ < A > }\) ≈ 1.19-1.20 Å, demonstrating a remarkable tracking behavior between the two. The absence of a \({T}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}^{\max }\) plateau, as seen in Kirshenbaum’s50 isovalently-substituted Ba1−xSrxFe2As2 and Sr1−xCaxFe2As2 systems, together with the significant suppression of TN for \({r}_{ < A > }\) > 1.20 Å, can be attributed to modifications in the Fermi surface due to charge doping and disorder51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 induced by the widely contrasting ionic radii in our triply substituted A-site samples.

Exploring further the key parameters controlling magnetic properties, we found a linear relationship between \({T}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}/\sqrt{M}\) (where M is the magnitude of the magnetic moment) and \({r}_{ < A > }\), as shown in Fig. 3c, underscoring the substantial influence of the average A-site ionic radius in tuning magnetic interactions. Moreover, we discovered a correlation between \({r}_{ < A > }\), As-Fe-As bond-angle, and Fe-As bond-length, namely \({r}_{ < A > }\) ~ \(\left(\frac{\sin (\alpha )\sin (\beta )}{{({{{\rm{d}}}}_{{{{\rm{Fe}}}}-{{{\rm{As}}}}})}^{1/2}}\right)\) (see Fig. 3f), which resembles the well-known electronic bandwidth equation60,61,62 \(W\propto \frac{\cos \left(\omega \right)}{{({\rm{d}}_{{{TM}}-O})}^{3.5}}\), where TM represents common transition metal elements (e.g., Mn or Ni), and \(\omega =\frac{1}{2}\left(\pi -\left\langle \beta \right\rangle \right)\), with \(\left\langle \beta \right\rangle\) and dTM−O incorporating the average TM-O bond-angle and bond-length, respectively. This equation successfully describes the effects of chemical substitution and pressure on the electronic and magnetic properties of distorted rare-earth perovskite nickelates63 and manganites64,65,66.

Finally, by combining these independent scaling relations, an empirical equation was derived to describe the magnetic transition temperature in terms of the magnetic moment, As-Fe-As bond angle, and bond length:

where a and b are constants. For TN, a = −5611(47) K μB-0.5 and b = 9966(80) K Å0.5 μB-0.5, while for Tr, a = −950(54) K μB−0.5 and b = 1784(94) K Å0.5 μB-0.5. This equation agrees remarkably well with the observed TN and Tr values, as shown in Fig. 3e.

It is worth emphasizing that the functional form of Eq. (1) was determined empirically by fitting experimental results and examining their structural dependencies, as demonstrated in Fig. 3c, f. This formulation captures well-established correlations between transition temperatures and Fe-As bond lengths and angles, as supported by both experimental and theoretical studies67,68,69,70,71,72,73. Although a full theoretical derivation remains an open question, multiple first-principles calculations and experimental findings demonstrate that Fe-As bond lengths, bond angles, and magnetic ordering temperatures are strongly correlated in the hole-doped iron pnictides.

The trigonometric terms sin(\(\alpha\)) and sin(\(\beta\)) in Eq. (1) arise from the geometric dependence of exchange interactions on bond angles, reflecting how deviations from the ideal tetrahedral angle influence magnetic interactions. Such angular distortions modulate Fe 3d-As 4p orbital hybridization and exchange pathways, an effect noted in both experimental and theoretical studies. Yin et al.67, for example, showed that structural distortions affect orbital differentiation, with the Fe dxy orbital being particularly sensitive to bond-angle changes, supporting the use of trigonometric functions to model these effects. Similarly, tight-binding and hybridization-based descriptions suggest that orbital overlaps have a trigonometric dependence, justifying the use of sin(α) and sin(β) rather than simple linear terms such as α and \(\beta\). Alternative functional forms were tested, but the demonstrated success of this formulation to fit the TN and Tr experimental values, as shown in Fig. 3e, supports its validity.

The As-Fe-As bond angle is a key structural parameter in iron pnictide superconductors and has been shown to influence the strength of orbital fluctuations68. These fluctuations are strongest when the FeAs4 tetrahedron approaches a regular configuration, corresponding to an optimal As-Fe-As bond angle. This result explains the experimentally observed correlation between the optimal bond angle and the superconducting transition temperature (TC) (Lee et al.74). Since maximum superconductivity is associated with the suppression of magnetic order, the As-Fe-As bond angle plays a significant role in tuning the strength of magnetic correlations, as also noted in studies on spin fluctuations70.

The influence of Fe-As bond lengths on magnetic ordering stems from their direct role in exchange interactions. Shorter Fe-As bonds enhance covalent bonding between Fe 3 d and As 4p orbitals, increasing bonding-antibonding splitting and reducing local magnetic moments, which promotes greater itinerancy of the electrons71. This behavior drives long-range super-exchange interactions that contribute dominantly to antiferromagnetic interactions between nearest neighbors. Using DFT + DMFT calculations, Yin et al.67 demonstrated that Fe-As bond lengths and angles are critical in controlling electronic correlations and ordered magnetic moments in iron pnictides and chalcogenides, providing theoretical justification for the structural dependencies incorporated in Eq. (1).

The inclusion of the magnetic moment term \(\sqrt{M}\) accounts for its influence on exchange interactions and transition temperatures. First-principles calculations72 have shown that the Fe-spin state is strongly coupled to the Fe-As bonding environment, where a reduction in the Fe magnetic moment weakens Fe-As bonding and enhances As-As hybridization. This structural modification directly impacts the stability of magnetic ordering. Furthermore, studies on Stoner factors in doped “122” iron pnictides73 have shown a direct correlation between Fe-As bond length and magnetic instability, providing additional theoretical justification for incorporating this dependence into Eq. (1). Further, Yin et al.67 presented strong evidence that the magnetic moment of Fe is closely linked to the Fe-As bonding environment and electronic correlations, rather than being a mere consequence of itinerancy or localization. Similarly, theoretical studies by Usui and Kuroki70 highlight how changes in Fe-As bond length modulate the density of states at the Fermi level, affecting both magnetic interactions and superconductivity.

Discussion

To better understand the scaling behavior and universality of our phase diagram, we first examined the structural impact of substitution, particularly focusing on the average A-site ionic radius, \({r}_{ < A > }\). Initially, the dominant influence arises from changes in the inversely evolving tetrahedral bond angles, which drive modifications in the conduction band at the Fermi surface. These changes lead to an increase in the Néel temperature (TN), in agreement with theoretical studies that highlight the sensitivity of the Fermi surface and the material’s resistive and magnetic properties to small topological variations in the electron and hole pockets75, as exemplified in BaFe2(As1−xPx)24,76,77,78,79.

However, as \({r}_{ < A > }\) decreases to approach 1.22 Å, the bond angles stabilize and remain largely unchanged. This stabilization presents a challenge in explaining the observed downturns of TN and Tr. Upon further analysis (Fig. 3a), we found that in this region, the Fe-As bond length contracts continuously by ≈0.8% as the lattice compresses further, despite the stabilization of the bond angles. This contraction emerges as the principal structural parameter influencing the material’s magnetic properties. Simultaneously, the refined Fe magnetic moment decreases by ~0.4μB, as shown in Fig. 3d, consistent with earlier studies and full potential DFT calculations39,70,76 that report similar behavior for the magnetic moment in response to compression of the Fe-As bond length.

Disorder induced by the difference in the ionic radii of the A-site cations plays a critical role in shaping the magnetic properties of hole-doped pnictides. This disorder suppresses the spin density wave (SDW) \({C}_{2M}^{a}\) ordering, favoring the formation of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) phase, and emerges as a key scaling parameter when normalizing the nine phase diagrams investigated in this study, Fig. 4b. Supporting this idea, experiments on isovalently-substituted LaFeAs1−xPxO38 have demonstrated that disorder induced by differences in As/P ionic sizes stabilizes the double-Q magnetic phases. However, it remains unclear whether perfectly random local disorder or some form of local ordering produces distinct effects on electronic properties. For example, in the 1111-LaFeAs1−xPxO system, variations in synthesis methods result in vastly different electronic phase diagrams, where the suppression or preservation of superconducting and magnetic orders can be controlled despite identical long-range structures80. Similarly, disorder has been shown to have contrasting effects on the superconducting and magnetic properties of pnictide superconductors81 depending on whether the material is underdoped or overdoped.

The impact of disorder is further highlighted by studies on Na-substituted compounds such as Sr1−xNaxFe2As282,83 and Ba1−xNaxFe2As284, for example. In these systems, dopant-induced disorder increases with increasing Na concentrations, with local compositional fluctuations generating random fields85 that act on the orthorhombic structural order parameter and influence phase transitions. Pair distribution function analyses82,83 of Sr1−xNaxFe2As2 reveal that orthorhombic distortions persist locally even at high doping levels and in regions of the phase diagram where long-range orthorhombicity is absent. Similarly, single-crystal x-ray diffuse scattering studies84 on Ba1−xNaxFe2As2 have revealed strong local distortions induced by the large ionic size difference between Ba and Na, which lead to disorder of the electronic properties on the Fe sites.

The presence of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) magnetic phase in samples near optimal nesting conditions supports existing literature, which suggests that the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) samples, despite their varying Na content, maintain similar electronic structures across different phase diagrams. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) measurements86,87, for instance, have shown that electron or hole doping affects the chemical potential, shifting it continuously in agreement with a rigid band shift model predicted by renormalized first-principle band calculations88. This shift results in an electron-hole asymmetry in the Fermi surface nesting conditions, with the Lindhard spin susceptibility function peaking on the hole-doped side of the phase diagram near optimal doping for superconductivity. Assuming a rigid chemical potential shift, simulations by Scherer and Anderson42 suggest that hole doping enhances c-axis polarized low-energy magnetic fluctuations in BaFe2As2 and LaFeAsO and modifies the magnetic anisotropy hierarchy. This enhancement is consistent with increased magnetic susceptibility along the c-axis, in agreement with the observed out-of-plane magnetic moment of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) phase and ARPES measurements86.

The presence of the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}}\) phase in electron-doped BaFe2−xMxAs2 (where M is a transition metal) remains uncertain. As mentioned earlier, experimental studies, including our own, have confirmed the presence of this phase in several hole-doped “122” families and in LaFeAs1−xPxO38, where strong competition between superconductivity and magnetism is observed. Similarly, this phase has been observed in FeSe when subjected to ~6.8 GPa pressure89, resembling the behavior seen in hole-doped “122” compounds.

A broader perspective on the impact of substitution strategies was provided by Dai90, who reviewed the effects of both A-site and B-site substitutions on spin excitations and magnetic order, offering important perspectives into the role of substitution in magnetic phase transitions. Consistent with our observations, theoretical studies91,92,93 suggest that disorder induced by A-site hole substitution favors the double-Q magnetic state over the single-Q SDW state, highlighting the role of substitution-induced disorder in stabilizing distinct magnetic phases. Models proposed by Vavilov and Chubukov94 identify disorder as a primary scaling parameter in generic phase diagrams. Disorder affects the Fe 3 d bands through different mechanisms, directly via Fe-site substitutions or indirectly through local distortions induced by A-site and As-site substitutions. Fe-site substitutions (e.g., Co or Ni replacing Fe) increase intraband scattering in the electron bands due to additional electrons, which disrupts the electronic structure of the Fe 3 d orbitals, weakens magnetic exchange interactions, and causes fluctuations in the As-Fe-As bond angle. These effects result in a rapid suppression of the magnetic order. In contrast, A-site substitutions (e.g., K or Na replacing Ba) induce structural distortions that alter the interlayer spacing and modify the Fe-As bond lengths and bond angles without directly affecting the Fe plane. This leads to a more gradual suppression of the single-Q SDW state and the observed emergence of competing magnetic phases, reinforcing the importance of differentiating between structural and electronic disorder when analyzing phase stability. The suppression of the single-Q SDW state by A-site substitution, in favor of a double-Q magnetic state involving two itinerant Fe electronic sublattices, clearly demonstrates the significant impact of A-site substitution on the Fe 3 d bands.

Further theoretical studies suggest that variations in the As-Fe-As bond angle influence orbital-dependent electronic structure, particularly affecting the yz/xz versus xy energy splitting28,67,95,96, which governs magnetic interactions. Deviations from the ideal tetrahedral geometry suppress the nesting conditions required for spin-density wave formation and alter the stability of competing magnetic and superconducting phases. Thus, while both Fe-site and A-site substitutions introduce disorder, their effects on magnetism and superconductivity remain distinct, requiring careful consideration of their structural and orbital consequences.

The competing single-Q and double-Q magnetic phases underline the intimate relationship between magnetic state degeneracy and itinerant electron properties. The tetragonal collinear double-Q magnetic state emerges from the superposition of two orthogonal spin-density waves that restore the four-fold symmetry of the crystal structure23. This wave interference redistributes the spin density such that half of the iron sites are non-magnetic, whereas the magnetic moments of the remaining sites are doubled. The itinerant character of the magnetic excitations, demonstrated experimentally8,23,34,40,93,97,98,99 and theoretically91,92,100,101,102,103, is incompatible with localized spin models and provides clear evidence for itinerant magnetism.

Finally, the observed scaling relationship, captured by Eq. (1), between the magnetic transition temperatures of both the orthorhombic and tetragonal phases and key internal structural parameters provides strong evidence for the existence of a unified origin rooted in the nesting instabilities of the itinerant electrons. Nesting conditions, influenced by Fermi surface topology7,51,59,70,104,105,106 and electron-hole pocket interactions, influence the stability of the competing magnetic phases.

In conclusion, the pronounced suppression of TN upon doping, especially near the \({C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }\) phases where optimal charge doping and nesting conditions converge, reveals a delicate balance between superconductivity and magnetism. While charge doping tunes the nesting conditions, disorder induced by contrasting A-site ionic radii emerges as a hidden but critical tuning parameter. This scaling parameter produces a universal phase diagram that explains the properties of hole-doped “122” material systems and offers a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between structural, electronic, and magnetic characteristics.

Methods

The nuclear and magnetic structures of our samples were determined as a function of temperature using high-quality neutron powder diffraction data collected at POWGEN107, HB-2A108, and WISH109 at the Spallation Neutron Source and High Flux Isotope Reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, respectively. High-resolution x-ray powder diffraction was conducted using beamline 11-BM-B110,111 at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Consistent Rietveld refinement results were obtained from multiple samples measured on all four instruments, enabling the combination of refined structural parameters without corrections. The absence of impurity phases together with the linear evolution of the refined lattice parameters and unit cell volume within each of the nine investigated series, as a function of the average ionic radius of the A-site mixed ions, \({r}_{ < A > }\), demonstrate the high quality of our stoichiometric samples, as shown in Fig. 2.

Measurements of superconductivity, displayed in Fig. 3, were performed using a Quantum Design Magnetic Property Measurement System with zero field cooling and a measuring field of 200 Oe on warming. Tabulated values112 of the ionic radii of eight-coordinated Ba (1.42 Å), Sr (1.26 Å), Ca (1.12 Å) and Na (1.18 Å) were used to calculate the average ionic radius of the A-site mixed ions, \({r}_{ < A > }\).

Figure 4b was constructed by normalizing the sodium content (\(x\)) of each sample to that of the sample displaying maximum transition temperature (Tr) denoted as \({x}_{{C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }}\). These normalized values (\(x\)/\({x}_{{C}_{4M}^{{c}\max }}\)) were used as a common x-axis for all the phase diagrams. Similarly, the transition temperatures (TN, Tr, and TC) were scaled to the maximum transition temperature, TN, of the sodium-free sample (x(Na) = 0) within each Ba1−xSrx and Sr1−xCax series, with the Ba/Sr or Sr/Ca ratios constrained as described earlier. The TN values for sodium-free samples were taken from Kirshenbaum et al.50.

Data availability

Data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data collected at ISIS may be accessible at https://doi.org/10.5286/ISIS.E.67768465.

References

Kamihara, Y. et al. Iron-based layered superconductor: LaOFeP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 10012–10013 (2006).

Kamihara, Y., Watanabe, T., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05 − 0.12) with Tc = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296–3297 (2008).

Johrendt, D. & Pöttgen, R. Pnictide oxides: a new class of high-TC superconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4782–4784 (2008).

Jiang, S. et al. Superconductivity up to 30 K in the vicinity of the quantum critical point in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 382203 (2009).

Avci, S. et al. Magnetically driven suppression of nematic order in an iron-based superconductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3845 (2014).

Böhmer, A. E. et al. Superconductivity-induced re-entrance of the orthorhombic distortion in Ba1-xKxFe2As2. Nat. Commun. 6, 7911 (2015).

Hassinger, E. et al. Pressure-induced Fermi-surface reconstruction in the iron-arsenide superconductor Ba1-xKxFe2As2: Evidence of a phase transition inside the antiferromagnetic phase. Phys. Rev. B. 86, 140502 (2012).

Hassinger, E. et al. Expansion of the tetragonal magnetic phase with pressure in the iron arsenide superconductor Ba1-xKxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B. 93, 144401 (2016).

Christianson, A. D. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 from inelastic neutron scattering. Nature 456, 930–932 (2008).

Stewart, G. R. Unconventional superconductivity. Adv. Phys. 66, 75–196 (2017).

de La Cruz, C. et al. Magnetic order close to superconductivity in the iron-based layered LaO1-xFxFeAs systems. Nature 453, 899–902 (2008).

Ma, F. & Lu, Z. Y. Iron-based layered compound LaFeAsO is an antiferromagnetic semimetal. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 033111 (2008).

Wang, X. F. et al. Anisotropy in the electrical resistivity and susceptibility of superconducting BaFe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 117005 (2009).

Fernandes, R. M. & Chubukov, A. V. Low-energy microscopic models for iron-based superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 014503 (2017).

Lorenzana, J., Seibold, G., Ortix, C. & Grilli, M. Competing orders in FeAs layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 186402 (2008).

Ding, Q. P. et al. Hedgehog spin-vortex crystal antiferromagnetic quantum criticality in CaK(Fe1-xNix)4As4 revealed by NMR. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 137204 (2018).

Meier, W. R. et al. Hedgehog spin-vortex crystal stabilized in a hole-doped iron-based superconductor. NPJ Quantum Mater. 3, 5 (2018).

Dai, J., Si, Q., Zhu, J. X. & Abrahams, E. Iron pnictides as a new setting for quantum criticality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4118–4121 (2009).

Nakai, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity and antiferromagnetic quantum critical behavior in the isovalent-doped BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 107003 (2010).

Analytis, J. G. et al. Transport near a quantum critical point in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. Nat. Phys. 10, 194–197 (2014).

Shibauchi, T., Carrington, A. & Matsuda, Y. A quantum critical point lying beneath the superconducting dome in iron pnictides. Annu Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 113–135 (2014).

Waßer, F. et al. Spin reorientation in Ba0.65Na0.35Fe2As2 studied by single-crystal neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 91, 060505 (2015).

Allred, J. M. et al. Double-Q spin-density wave in iron arsenide superconductors. Nat. Phys. 12, 493–498 (2016).

Chubukov, A. Pairing mechanism in Fe-based superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 3, 57–92 (2012).

Hirschfeld, P. J., Korshunov, M. M. & Mazin, I. I. Gap symmetry and structure of Fe-based superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124508 (2011).

Si, Q. & Abrahams, E. Strong correlations and magnetic frustration in the high TC iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 076401 (2008).

Seo, K., Bernevig, B. A. & Hu, J. Pairing symmetry in a two-orbital exchange coupling model of oxypnictides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 206404 (2008).

de’ Medici, L., Giovannetti, G. & Capone, M. Selective Mott physics as a key to iron superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 177001 (2014).

Krüger, F., Kumar, S., Zaanen, J. & Van Den Brink, J. Spin-orbital frustrations and anomalous metallic state in iron-pnictide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 79, 054504 (2009).

Kontani, H., Inoue, Y., Saito, T., Yamakawa, Y. & Onari, S. Orbital fluctuation theory in iron-based superconductors: s++-wave superconductivity, structure transition, and impurity-induced nematic order. Solid State Commun. 152, 718–727 (2012).

Chubukov, A. V., Efremov, D. V. & Eremin, I. Magnetism, superconductivity, and pairing symmetry in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 134512 (2008).

Cvetkovic, V. & Tesanovic, Z. Multiband magnetism and superconductivity in Fe-based compounds. Europhys. Lett. 85, 37002 (2009).

Fernandes, R. M. et al. Unconventional pairing in the iron arsenide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 140501 (2010).

Allred, J. M. et al. Tetragonal magnetic phase in Ba1-xKxFe2As2 from x-ray and neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B. 92, 094515 (2015).

Taddei, K. M. et al. Observation of the magnetic C4 phase in Ca1-xNaxFe2As2 and its universality in the hole-doped 122 superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 95, 064508 (2017).

Avci, S. et al. Structural, magnetic, and superconducting properties of Ba1-xNaxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 094510 (2013).

Wiesenmayer, E. et al. Microscopic coexistence of superconductivity and magnetism in Ba1-xKxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 237001 (2011).

Stadel, R. et al. Multiple magnetic orders in LaFeAs1-xPxO uncover universality of iron-pnictide superconductors. Commun. Phys. 5, 146 (2022).

Taddei, K. M. et al. Detailed magnetic and structural analysis mapping a robust magnetic C4 dome in Sr1-xNaxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 134510 (2016).

Kang, J., Wang, X., Chubukov, A. V. & Fernandes, R. M. Interplay between tetragonal magnetic order, stripe magnetism, and superconductivity in iron-based materials. Phys. Rev. B 91, 121104 (2015).

Christensen, M. H., Kang, J., Andersen, B. M., Eremin, I. & Fernandes, R. M. Spin reorientation driven by the interplay between spin-orbit coupling and Hund’s rule coupling in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 92, 214509 (2015).

Scherer, D. D. & Andersen, B. M. Spin-orbit coupling and magnetic anisotropy in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 037205 (2018).

Zhou, R. et al. Quantum criticality in electron-doped BaFe2-xNixAs2. Nat. Commun. 4, 2265 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Local orthorhombic lattice distortions in the paramagnetic tetragonal phase of superconducting NaFe1-xNixAs. Nat. Commun. 9, 3128 (2018).

Hayes, I. M. et al. Scaling between magnetic field and temperature in the high-temperature superconductor BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. Nat. Phys. 12, 916–919 (2016).

Kimber, S. A. J. et al. Similarities between structural distortions under pressure and chemical doping in superconducting BaFe2As2. Nat. Mater. 8, 471–475 (2009).

Johannes, M. D., Mazin, I. I. & Parker, D. S. Effect of doping and pressure on magnetism and lattice structure of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 024527 (2010).

Kim, J. S. et al. Electron-hole asymmetry in Co- and Mn-doped SrFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 82, 024510 (2010).

Avci, S. et al. Phase diagram of Ba1-xKxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 85, 184507 (2012).

Kirshenbaum, K. et al. Tuning magnetism in FeAs-based materials via a tetrahedral structure. Phys. Rev. B 86, 060504 (2012).

Liu, C. et al. Importance of the Fermi-surface topology to the superconducting state of the electron-doped pnictide Ba(Fe1-xCox)2As2. Phys. Rev. B 84, 020509 (2011).

Xu, N. et al. Possible nodal superconducting gap and Lifshitz transition in heavily hole-doped Ba0.1K0.9Fe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 220508 (2013).

Yamashita, H. et al. Origin of T c enhancement induced by doping yttrium and hydrogen into LaFeAsO-based superconductors: 57Fe-, 75As-, 139La-, and 1H-NMR studies. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 103703 (2010).

Surmach, M. A. et al. Impurity effects on spin dynamics in magnetic and superconducting iron pnictides and chalcogenides. Physica Status Solidi (b) 254, 1600162 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Evidence for a Lifshitz transition in electron-doped iron arsenic superconductors at the onset of superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 6, 419–423 (2010).

Hirschfeld, P. J. Using gap symmetry and structure to reveal the pairing mechanism in Fe-based superconductors. C. R. Phys. 17, 197–231 (2015).

Ishida, S. et al. Effect of doping on the magnetostructural ordered phase of iron arsenides: a comparative study of the resistivity anisotropy in doped BaFe2As2 with doping into three different sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 3158–3163 (2013).

Malaeb, W. et al. Abrupt change in the energy gap of superconducting Ba1-xKxFe2As2 single crystals with hole doping. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165117 (2012).

Yaresko, A. N., Liu, G.-Q., Antonov, V. N. & Andersen, O. K. Interplay between magnetic properties and Fermi surface nesting in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 79, 144421 (2009).

Harrison, W. A. Elementary Electronic Structure https://doi.org/10.1142/5432 (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2004).

Dearnaley, G. Electronic structure and properties of solids: the physics of the chemical bond. Phys. Bull. 31, 359–359 (1980).

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039–1263 (1998).

Medarde, M. et al. High-pressure neutron-diffraction study of the metallization process in PrNiO3. Phys. Rev. B 52, 9248–9258 (1995).

Fontcuberta, J. et al. Colossal magnetoresistance of ferromagnetic manganites: Structural tuning and mechanisms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1122–1125 (1996).

Goodenough, J. B. Electronic structure of CMR manganites (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 81, 5330–5335 (1997).

Uehara, M., Mori, S., Chen, C. H. & Cheong, S. W. Percolative phase separation underlies colossal magnetoresistance in mixed-valent manganites. Nature 399, 560–563 (1999).

Yin, Z. P., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Kinetic frustration and the nature of the magnetic and paramagnetic states in iron pnictides and iron chalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 10, 932–935 (2011).

Saito, T., Onari, S. & Kontani, H. Orbital fluctuation theory in iron pnictides: effects of As-Fe-As bond angle, isotope substitution, and Z2 orbital pocket on superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144510 (2010).

Lee, C. H. et al. Relationship between crystal structure and superconductivity in iron-based superconductors. Solid State Commun. 152, 644–648 (2012).

Usui, H. & Kuroki, K. Maximizing the Fermi-surface multiplicity optimizes the superconducting state of iron pnictide compounds. Phys. Rev. B 84, 024505 (2011).

Belashchenko, K. D. & Antropov, V. P. Role of covalent Fe-As bonding in the magnetic moment formation and exchange mechanisms in iron-pnictide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 78, 212505 (2008).

Yildirim, T. Strong coupling of the Fe-spin state and the As-As hybridization in iron-pnictide superconductors from first-principle calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 037003 (2009).

Sen, S. & Ghosh, H. Stoner factors of doped 122 Fe-based superconductors: first principles results. Comput. Mater. Sci. 132, 46–54 (2017).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Effect of structural parameters on superconductivity in fluorine-free LnFeAsO1-y (Ln = La, Nd). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 083704 (2008).

Fanfarillo, L., Cortijo, A. & Valenzuela, B. Spin-orbital interplay and topology in the nematic phase of iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 91, 214515 (2015).

Rotter, M., Hieke, C. & Johrendt, D. Different response of the crystal structure to isoelectronic doping in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2 and (Ba1-xSrx)Fe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014513 (2010).

Ren, Z. et al. Superconductivity induced by phosphorus doping and its coexistence with ferromagnetism in EuFe2(As0.7P0.3)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 137002 (2009).

Taddei, K. M. Magnetism in the iron-based superconductors: the determination of spin-nematic fluctuations as the primary order parameter and its implications for unconventional superconductivity. (Northern Illinois University, 2016).

Allred, J. M. et al. Coincident structural and magnetic order in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2 revealed by high-resolution neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 90, 104513 (2014).

Shiroka, T. et al. Nodal-To-nodeless superconducting order parameter in LaFeAs1-xPxO synthesized under high pressure. NPJ Quantum Mater. 3, 25 (2018).

Fernandes, R. M., Vavilov, M. G. & Chubukov, A. V. Enhancement of TC by disorder in underdoped iron pnictide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 85, 140512 (2012).

Frandsen, B. A. et al. Widespread orthorhombic fluctuations in the (Sr,Na)Fe2As2 family of superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 98, 180505(R) (2018).

Frandsen, B. A. et al. Local orthorhombicity in the magnetic C4 phase of the hole-doped iron-arsenide superconductor Sr1-xNaxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 187001 (2017).

Stadel, R. et al. Magnetic anisotropy and two-dimensional short-range chemical ordering in Ba1-xNaxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 124802 (2023).

Fisher, D. S. Scaling and critical slowing down in random-field Ising systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 416–419 (1986).

Neupane, M. et al. Electron-hole asymmetry in the superconductivity of doped BaFe2As2 seen via the rigid chemical-potential shift in photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 83, 094522 (2011).

Sato, T. et al. Band structure and Fermi surface of an extremely overdoped iron-based superconductor KFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 047002 (2009).

Xu, G., Zhang, H., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Electron-hole asymmetry and quantum critical point in hole-doped BaFe2As2. Europhys. Lett. 84, 67015 (2008).

Böhmer, A. E. et al. Distinct pressure evolution of coupled nematic and magnetic orders in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 100, 064515 (2019).

Dai, P. Antiferromagnetic order and spin dynamics in iron-based superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 855–896 (2015).

Hoyer, M., Fernandes, R. M., Levchenko, A. & Schmalian, J. Disorder-promoted C4 -symmetric magnetic order in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 93, 144414 (2016).

Dzero, M. & Khodas, M. Quasiclassical theory of C4-symmetric magnetic order in disordered multiband metals. Front. Phys. 8, 356 (2020).

Gastiasoro, M. N. & Andersen, B. M. Competing magnetic double-Q phases and superconductivity-induced reentrance of C2 magnetic stripe order in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 92, 140506 (2015).

Vavilov, M. G. & Chubukov, A. V. Phase diagram of iron pnictides if doping acts as a source of disorder. Phys. Rev. B 84, 214521 (2011).

Miyake, T., Nakamura, K., Arita, R. & Imada, M. Comparison of ab initio low-energy models for LaFePO, LaFeAsO, BaFe2As2, LiFeAs, FeSe, and FeTe: electron correlation and covalency. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 044705 (2010).

Bascones, E., Valenzuela, B. & Calderón, M. J. Magnetic interactions in iron superconductors: a review. C. R. Phys. 17, 36–59 (2015).

Yue, L. et al. Raman scattering study of the tetragonal magnetic phase in Sr1-xNaxFe2As2 structural symmetry and electronic gap. Phys. Rev. B 96, 180505(R) (2017).

Mallett, B. P. P., Pashkevich, Y. G., Gusev, A., Wolf, T. & Bernhard, C. Muon spin rotation study of the magnetic structure in the tetragonal antiferromagnetic state of weakly underdoped Ba1-xKxFe2As2. Epl 111, 57001 (2015).

Timmons, E. I. et al. Competition between orthorhombic and re-entrant tetragonal phases in underdoped Ba1-xKxFe2As2 probed by the response to controlled disorder. Phys. Rev. B 99, 054518 (2019).

Christensen, M. H., Orth, P. P., Andersen, B. M. & Fernandes, R. M. Magnetic phase diagram of the iron pnictides in the presence of spin-orbit coupling: frustration between C2 and C4 magnetic phases. Phys. Rev. B 98, 014523 (2018).

Knolle, J., Eremin, I., Chubukov, A. V. & Moessner, R. Theory of itinerant magnetic excitations in the spin-density-wave phase of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 81, 140506 (2010).

Zhang, Y.-Z., Opahle, I., Jeschke, H. O. & Valentí, R. Itinerant nature of magnetism in iron pnictides: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 81, 094505 (2010).

Tam, Y.-T., Yao, D.-X. & Ku, W. Itinerancy-enhanced quantum fluctuation of magnetic moments in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 117001 (2015).

Xu, N. et al. Effects of Ru substitution on electron correlations and Fermi-surface dimensionality in Ba(Fe1-xRux)2As2. Phys. Rev. B 86, 064505 (2012).

Pan, L. et al. Evolution of the Fermi surface topology in doped 122 iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214510 (2013).

Kuroki, K. et al. Unconventional pairing originating from the disconnected fermi surfaces of superconducting LaFeAsO1-xFx. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 087004 (2008).

Huq, A. et al. POWGEN: Rebuild of a third-generation powder diffractometer at the spallation neutron source. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 52, 1189–1201 (2019).

Calder, S. et al. A suite-level review of the neutron powder diffraction instruments at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89, 092701 (2018).

Chapon, L. C. et al. Wish: the new powder and single crystal magnetic diffractometer on the second target station. Neutron N. 22, 22–25 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. A dedicated powder diffraction beamline at the advanced photon source: commissioning and early operational results. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 085105 (2008).

Lee, P. L. et al. A twelve-analyzer detector system for high-resolution powder diffraction. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 15, 427–432 (2008).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Acknowledgements

Work at Argonne National Laboratory was funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division. Synchrotron X-ray experiments were performed at the Advanced Photon Source [11-BM-B under GUP-43680], a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. A portion of this research used resources at the High Flux Isotope Reactor and Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Beamtime was allocated at BL-11A (POWGEN) and HB-2A (POWDER) under proposal numbers IPTS-14499.1 and 14499.2. Experiments at the ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source were supported by beamtime allocation from the Science and Technology Facilities Council under proposal RB1520340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.C., M.K., R.O. and S.R. jointly planned and supervised this work. D.B., D.Y.C., and R.S. synthesized the materials. O.C., S.R., R.S., K.M.T., D.K. and P.M. performed the x-ray and neutron diffraction experiments and analysis of the data. All authors contributed to the writing and proofing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Takashi Mizokawa and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Nicola Poccia and Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chmaissem, O., Stadel, R., Taddei, K.M. et al. Disorder-induced universality and scaling in hole-doped iron-based superconductors. Commun Mater 6, 146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00843-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00843-x